PBH91001 - Critical Appraisal of Music Therapy for Sleep Quality

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/03

|8

|6795

|254

Report

AI Summary

This report critically appraises the effectiveness of music therapy in improving sleep quality among older adults. It examines a randomized controlled study investigating the effects of sedative music on sleep quality in a cohort of older community-dwelling adults in Singapore, measuring sleep quality using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). The intervention involved participants listening to soft, instrumental music for 6 weeks, with results showing significant improvements in sleep quality compared to a control group. The appraisal considers the study's methodology, findings, and implications for healthcare, emphasizing the potential of music listening as a non-pharmacological intervention to enhance sleep quality and promote healthy aging. This assignment also includes the critical appraisal of a systematic review (secondary evidence) related to this topic. Desklib provides access to a wealth of similar assignments and past papers for students seeking to deepen their understanding of healthcare research and evidence-based practice.

ComplementaryTherapiesin Medicine(2014)22, 49—56

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

j ou rn a l home p a ge : w w w . e l s e v i e r h e a l t h . c o m / j o u r n a l s / c t i m

Theeffectsof sedativemusicon sleep

qualityof oldercommunity-dwellingadults

in Singapore

AngelaShuma, BeverleyJoan Taylorb, Jeff Thayalac,

MoonFaiChana,∗

a Alice Lee Centre for NursingStudies,YongLoo Lin Schoolof Medicine,NationalUniversityof Singapore,

Singapore

b Faculty of Medicine,Nursingand Health Sciences,Schoolof Nursingand Midwifery,MonashUniversity,

GippslandCampus,Churchill, Victoria, Australia

c Departmentof NursingAdministrations,Institute of Mental Health, Singapore

Availableonline 14 November2013

KEYWORDS

Musiclistening;

Olderadults;

Sleepquality

Summary

Objectives:Toexaminethe effectsof musiclisteningon sleepqualityamongstoldercommunity-

dwellingadultsin Singapore.

Methods:In a randomizedcontrolledstudy,a cohortof olderadults(N =60)age55yearsor above

were recruited in one communitycentre. Sleep quality, as measuredby the PittsburghSleep

QualityIndex(PSQI), was the primaryoutcome.Participants’demographicvariablesincluding

age,gender,religion,educationlevel, maritalandfinancialstatus,anychronicillness,previous

experiencesof musicinterventionas well asdepressionlevelswerecollected.Participantswere

askedto listen to soft, instrumentalslowsedativemusicwithoutlyrics, of approximately60—80

beatsper minute, and 40min in duration,for 6 weeks.Generalizedestimatingequationswere

usedto examinethe effects of the interventionon the elders’ sleepquality.

Results:Significantreductionsin PSQIscoreswere foundin the interventiongroup(n =28)from

baseline(mean± SD, 10.2± 2.5) to week 6 (5.9± 2.4, p <0.001),while there were no changes

in the control group (n =32) from baseline(9.0± 2.4) to week 6 (9.5± 2.6). At week 6, the

interventiongroupshoweda better sleepquality than the control ( 2 =61.84,p <0.001).

Conclusions:Notwithstandingthe placeboeffect, this studysupportsmusiclisteningasan effec-

tive interventionfor older adultsto improvesleep quality.Not only doesthis processimprove

their sleepingquality at old age, it also individualizesand enhancesthe quality of care pro-

vided by the healthcareprovideras the therapeuticrelationshipbetweenproviderand client

is beingestablished.Contemporarygerontologyis progressivelycharacterizedby collaboration

betweenseveralapproacheswith the intent to comprehendthe mentalaspectsof the multi-

fariousprocessof ageing.Musiclisteningis one suchavenueto enhancesleepquality amongst

older adultsand makean essentialcontributionto healthyageing.

©2013ElsevierLtd. All rightsreserved.

∗ Correspondingauthor.Tel.: +6565168684.

E-mail address:nurcmf@nus.edu.sg(M.F.Chan).

0965-2299/$— see front matter©2013ElsevierLtd. All rightsreserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2013.11.003

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

j ou rn a l home p a ge : w w w . e l s e v i e r h e a l t h . c o m / j o u r n a l s / c t i m

Theeffectsof sedativemusicon sleep

qualityof oldercommunity-dwellingadults

in Singapore

AngelaShuma, BeverleyJoan Taylorb, Jeff Thayalac,

MoonFaiChana,∗

a Alice Lee Centre for NursingStudies,YongLoo Lin Schoolof Medicine,NationalUniversityof Singapore,

Singapore

b Faculty of Medicine,Nursingand Health Sciences,Schoolof Nursingand Midwifery,MonashUniversity,

GippslandCampus,Churchill, Victoria, Australia

c Departmentof NursingAdministrations,Institute of Mental Health, Singapore

Availableonline 14 November2013

KEYWORDS

Musiclistening;

Olderadults;

Sleepquality

Summary

Objectives:Toexaminethe effectsof musiclisteningon sleepqualityamongstoldercommunity-

dwellingadultsin Singapore.

Methods:In a randomizedcontrolledstudy,a cohortof olderadults(N =60)age55yearsor above

were recruited in one communitycentre. Sleep quality, as measuredby the PittsburghSleep

QualityIndex(PSQI), was the primaryoutcome.Participants’demographicvariablesincluding

age,gender,religion,educationlevel, maritalandfinancialstatus,anychronicillness,previous

experiencesof musicinterventionas well asdepressionlevelswerecollected.Participantswere

askedto listen to soft, instrumentalslowsedativemusicwithoutlyrics, of approximately60—80

beatsper minute, and 40min in duration,for 6 weeks.Generalizedestimatingequationswere

usedto examinethe effects of the interventionon the elders’ sleepquality.

Results:Significantreductionsin PSQIscoreswere foundin the interventiongroup(n =28)from

baseline(mean± SD, 10.2± 2.5) to week 6 (5.9± 2.4, p <0.001),while there were no changes

in the control group (n =32) from baseline(9.0± 2.4) to week 6 (9.5± 2.6). At week 6, the

interventiongroupshoweda better sleepquality than the control ( 2 =61.84,p <0.001).

Conclusions:Notwithstandingthe placeboeffect, this studysupportsmusiclisteningasan effec-

tive interventionfor older adultsto improvesleep quality.Not only doesthis processimprove

their sleepingquality at old age, it also individualizesand enhancesthe quality of care pro-

vided by the healthcareprovideras the therapeuticrelationshipbetweenproviderand client

is beingestablished.Contemporarygerontologyis progressivelycharacterizedby collaboration

betweenseveralapproacheswith the intent to comprehendthe mentalaspectsof the multi-

fariousprocessof ageing.Musiclisteningis one suchavenueto enhancesleepquality amongst

older adultsand makean essentialcontributionto healthyageing.

©2013ElsevierLtd. All rightsreserved.

∗ Correspondingauthor.Tel.: +6565168684.

E-mail address:nurcmf@nus.edu.sg(M.F.Chan).

0965-2299/$— see front matter©2013ElsevierLtd. All rightsreserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2013.11.003

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

50 A. Shumet al.

Introduction

Sleep disturbanceshave been recognizedas a significant

and growingcausefor public healthconcern.1 Eventhough

it is known to affect all age groups, prior researchhas

suggestedthat older adults are of greater vulnerability

to sleep problems.2 Previousepidemiologicalstudieshave

indicated that sleep complaintslike sleep fragmentation

and daytimesleepinessaffected approximately35%of the

generalpopulation,3 and up to 50%of the older adults.4

Sleepdisturbancescontributeto insufficientor ineffective

sleep patterns, which are known to heightenthe risk for

adverseconsequenceslike cognitiveimpairment,falls, and

deteriorationin physicalfunctioning.1,5,6 Currently,pharma-

cotherapyis the main form of remedyto alleviate sleep

disturbancesand improvesleep quality.8 However,these

medicationsare associatedwith psychologicaland physi-

ological side effects that can affect daily activities and

functioningof individuals.The use of thesedrugscan also

leadto toleranceanddependence.9 Aspriorresearchhasyet

to establishthe safetyandefficacyof thesepharmacological

measures,10 sleep scientistshave recommendedexploring

non-pharmacologicaltechniqueswith a mind-bodyinterac-

tion to promotesleep.11 A range of non-pharmacological

interventionsare availableas alternativetreatmentsfor

sleep disturbances.They include cognitive behavioural

treatments,12 bright light therapy,13 and neurofeedback.7

However,the feasibilityof theseinterventionsis question-

able, as they often require large investmentsof time for

training purposes.14 As such, music interventionis iden-

tified by the researchersas an area of interest as it is

relativelyinexpensive,readily availableand can be easily

self-administered.15

A meta-analysisof fiverandomizedcontrolledtrials(RCT)

conductedwith relevanceto thistopicreporteda significant

effect of musiclisteningon sleepqualityfor all agegroupsin

general.14 Generalizedfindingson the effectivenessof music

listeningon sleepqualityare shownto be optimistic.How-

ever,thesefindingsmustbe interpretedwith caution,as all

of thesestudieswereconductedin differentpopulationsand

settings.14 In referenceto the elderlypopulation,the effects

of musicon their sleepqualityremainsuncertaindueto the

limitedstudiesconducted.Despiteits potentialbenefits,no

systematicreviewhasbeenconductedto evaluatethe effec-

tivenessof musicon sleepqualityfor older populations.To

date, only five related studies,16—20were found, of which

only one was a RCT studywith a sole focuson musiclisten-

ingfor olderadults.16 Otherstudiesconductedto investigate

the effectivenessof musiclisteningon sleep quality were

focuson older females,17 femalestudents,19,21andpatients

with insomnia,22 but all studiesclearlyindicatedcontinuous

improvementin sleep acrossthe time spanof the applied

intervention.16—18,20,21,23—25

The interventionperiodof these

studiesrangedfrom 10 days17 up to 45 days.23

Aim

The aimof this studywasto investigatethe effectsof music

listeningonsleepqualityamongstoldercommunity-dwelling

adultsin Singapore.The hypothesisfor this studywas that

older adultswho participatein a musicinterventiongroup

will report better sleepqualityscores,as measuredby the

PittsburghSleep Quality Index (PSQI), 6 weeks after the

intervention,comparedwith non-music(control)group.

Methods

Designandparticipants

This researchwas a RCT conductedat the participants’

homes from January 2012 to January 2013. A cohort of

community-dwellingolder adultswasrecruitedin one com-

munitycentrein Singapore.Inclusioncriteria were (1) aged

55 years or older,30 (2) living within the selectedarea of

northernpart of Singapore,(3) non-institutionalizeddur-

ing the studyperiod, (4) physicallycapableof completing

psychologicalassessment,(5) able to understandand com-

municatein either Englishor Mandarinand give written

consent,and(6) havea poorsleepquality,measuredby the

PSQI, with a scoreof 6 or above.26 Exclusioncriteria were

(1) a medicaldiagnosisof anyabnormalcognitivefunction,

such as Parkinson’sdiseaseor dementia,and (2) hearing

difficulties.

The required sample size was based on an expected

effect size of sleepqualitylevelspost-intervention.de Niet

et al.14 conducteda meta-analysisand results suggested

that music interventionhas a moderateeffect on sleep

quality in five RCT studies.In relation to effect size, the

nQueryAdvisorsoftware27 showsthatat least30participants

with completedata per groupwould be neededto detect

an effect with 80%powerand 5%significance.Approvalto

conductthe current study was soughtand obtainedfrom

the InstitutionalReviewBoard ethics committee.Written

informedconsentwasobtainedfromeachparticipantbefore

obtainingtheir baselinePQSIscores.

Themeasurements

The instrumentwas presentedin both Englishand Chinese

and consistedof two parts.Part one collectedparticipants’

demographicvariablesincludingage, gender,religion,edu-

cation level, maritaland financialstatus,and any previous

experienceof music interventions,any chronic illness as

well as depressivesymptoms,as measuredby the Geriatric

DepressionScale(GDS-15).28 Parttwo collecteddataon par-

ticipants’sleepquality,asmeasuredby the PQSI.ThePQSIis

a self-ratedquestionnairewhichassessessleepqualityand

disturbancesovera periodof time. The PSQIwaschosento

measurethe qualityof sleepin older adultsbecauseit has

a goodoverallreliabilitycoefficient(˛ =0.83).35 It hasbeen

usedin previousstudiesinvestigatingthe effects of music

on the quality of sleep.36,37 It is dividedinto severalcom-

ponentsthat assesssubjectivesleepquality,sleeplatency,

sleepduration,sleepefficiency,sleepdisturbances,use of

sleepingmedication,and daytimedysfunction.The sumof

scoresrangesfrom 0 to 21, and a scoreof 6 or aboveindi-

catesa poorsleepquality.26 All participantshadthe options

to chooseeither Englishor Chineseinstruments.For par-

ticipantsin the interventiongroup,data were collectedat

baselinebeforethe musicinterventionat week1, andafter

the musicinterventionin weeks2—6,oncea weekfor a total

of six times, includingthe baseline.For participantsin the

Introduction

Sleep disturbanceshave been recognizedas a significant

and growingcausefor public healthconcern.1 Eventhough

it is known to affect all age groups, prior researchhas

suggestedthat older adults are of greater vulnerability

to sleep problems.2 Previousepidemiologicalstudieshave

indicated that sleep complaintslike sleep fragmentation

and daytimesleepinessaffected approximately35%of the

generalpopulation,3 and up to 50%of the older adults.4

Sleepdisturbancescontributeto insufficientor ineffective

sleep patterns, which are known to heightenthe risk for

adverseconsequenceslike cognitiveimpairment,falls, and

deteriorationin physicalfunctioning.1,5,6 Currently,pharma-

cotherapyis the main form of remedyto alleviate sleep

disturbancesand improvesleep quality.8 However,these

medicationsare associatedwith psychologicaland physi-

ological side effects that can affect daily activities and

functioningof individuals.The use of thesedrugscan also

leadto toleranceanddependence.9 Aspriorresearchhasyet

to establishthe safetyandefficacyof thesepharmacological

measures,10 sleep scientistshave recommendedexploring

non-pharmacologicaltechniqueswith a mind-bodyinterac-

tion to promotesleep.11 A range of non-pharmacological

interventionsare availableas alternativetreatmentsfor

sleep disturbances.They include cognitive behavioural

treatments,12 bright light therapy,13 and neurofeedback.7

However,the feasibilityof theseinterventionsis question-

able, as they often require large investmentsof time for

training purposes.14 As such, music interventionis iden-

tified by the researchersas an area of interest as it is

relativelyinexpensive,readily availableand can be easily

self-administered.15

A meta-analysisof fiverandomizedcontrolledtrials(RCT)

conductedwith relevanceto thistopicreporteda significant

effect of musiclisteningon sleepqualityfor all agegroupsin

general.14 Generalizedfindingson the effectivenessof music

listeningon sleepqualityare shownto be optimistic.How-

ever,thesefindingsmustbe interpretedwith caution,as all

of thesestudieswereconductedin differentpopulationsand

settings.14 In referenceto the elderlypopulation,the effects

of musicon their sleepqualityremainsuncertaindueto the

limitedstudiesconducted.Despiteits potentialbenefits,no

systematicreviewhasbeenconductedto evaluatethe effec-

tivenessof musicon sleepqualityfor older populations.To

date, only five related studies,16—20were found, of which

only one was a RCT studywith a sole focuson musiclisten-

ingfor olderadults.16 Otherstudiesconductedto investigate

the effectivenessof musiclisteningon sleep quality were

focuson older females,17 femalestudents,19,21andpatients

with insomnia,22 but all studiesclearlyindicatedcontinuous

improvementin sleep acrossthe time spanof the applied

intervention.16—18,20,21,23—25

The interventionperiodof these

studiesrangedfrom 10 days17 up to 45 days.23

Aim

The aimof this studywasto investigatethe effectsof music

listeningonsleepqualityamongstoldercommunity-dwelling

adultsin Singapore.The hypothesisfor this studywas that

older adultswho participatein a musicinterventiongroup

will report better sleepqualityscores,as measuredby the

PittsburghSleep Quality Index (PSQI), 6 weeks after the

intervention,comparedwith non-music(control)group.

Methods

Designandparticipants

This researchwas a RCT conductedat the participants’

homes from January 2012 to January 2013. A cohort of

community-dwellingolder adultswasrecruitedin one com-

munitycentrein Singapore.Inclusioncriteria were (1) aged

55 years or older,30 (2) living within the selectedarea of

northernpart of Singapore,(3) non-institutionalizeddur-

ing the studyperiod, (4) physicallycapableof completing

psychologicalassessment,(5) able to understandand com-

municatein either Englishor Mandarinand give written

consent,and(6) havea poorsleepquality,measuredby the

PSQI, with a scoreof 6 or above.26 Exclusioncriteria were

(1) a medicaldiagnosisof anyabnormalcognitivefunction,

such as Parkinson’sdiseaseor dementia,and (2) hearing

difficulties.

The required sample size was based on an expected

effect size of sleepqualitylevelspost-intervention.de Niet

et al.14 conducteda meta-analysisand results suggested

that music interventionhas a moderateeffect on sleep

quality in five RCT studies.In relation to effect size, the

nQueryAdvisorsoftware27 showsthatat least30participants

with completedata per groupwould be neededto detect

an effect with 80%powerand 5%significance.Approvalto

conductthe current study was soughtand obtainedfrom

the InstitutionalReviewBoard ethics committee.Written

informedconsentwasobtainedfromeachparticipantbefore

obtainingtheir baselinePQSIscores.

Themeasurements

The instrumentwas presentedin both Englishand Chinese

and consistedof two parts.Part one collectedparticipants’

demographicvariablesincludingage, gender,religion,edu-

cation level, maritaland financialstatus,and any previous

experienceof music interventions,any chronic illness as

well as depressivesymptoms,as measuredby the Geriatric

DepressionScale(GDS-15).28 Parttwo collecteddataon par-

ticipants’sleepquality,asmeasuredby the PQSI.ThePQSIis

a self-ratedquestionnairewhichassessessleepqualityand

disturbancesovera periodof time. The PSQIwaschosento

measurethe qualityof sleepin older adultsbecauseit has

a goodoverallreliabilitycoefficient(˛ =0.83).35 It hasbeen

usedin previousstudiesinvestigatingthe effects of music

on the quality of sleep.36,37 It is dividedinto severalcom-

ponentsthat assesssubjectivesleepquality,sleeplatency,

sleepduration,sleepefficiency,sleepdisturbances,use of

sleepingmedication,and daytimedysfunction.The sumof

scoresrangesfrom 0 to 21, and a scoreof 6 or aboveindi-

catesa poorsleepquality.26 All participantshadthe options

to chooseeither Englishor Chineseinstruments.For par-

ticipantsin the interventiongroup,data were collectedat

baselinebeforethe musicinterventionat week1, andafter

the musicinterventionin weeks2—6,oncea weekfor a total

of six times, includingthe baseline.For participantsin the

The effect of sedativemusicon sleepquality 51

controlgroup,datawerecollectedoncea weekfor the same

6 weeks as the interventiongroup, when the researcher

visitedthemat home.

Themusicintervention

The processof musicinterventiontook place in each par-

ticipant’shome.After the randomallocationof participants

to groups,weeklyvisitswere madefor 6 weeksto measure

the sameoutcomes.Six weeksis a recommendedperiodof

time for observingsleep patterns,16,23 and the effects of

a new interventionon sleep quality.14 Participantsin the

experimentalgroupwere providedwith an MP4playerwith

earphonesin order to listen to the music of their choice

from a selection of soft, slow music without lyrics (for

details,pleaseseethe sectionon Selectionof music).Previ-

ous literaturehas shownsubjectiveand scientificevidence

in demonstratingthat music preferenceis a key element

in derivingbeneficialbenefitsfrom music.16,18,36Therefore,

participantswere allowedto choosetheir preferredmusic

and they were requiredto adhereto the use of a single

genreof musicwithin the sameweek, to minimizepossi-

ble variancesin the effect on sleep quality. Participants

were also told to choosethe most comfortableplace to

listen to the music, for examplein their bedroom.Stan-

dardizedinstructionswere givento the participantsas per

a protocol proposedby Chan et al.16 The researcherleft

the participantsalone and stayed a short distanceaway

unobtrusively,so that she or he could be availablefor any

unexpectedresponse.After 40min, the researcherstopped

the music and then collected all outcomesfor each par-

ticipant within a 10—15min conversation.Previousstudies

havesuggestedthat listeningto musiceverydaycontributes

to a better sleep at night, even if it is not consistently

heardat bedtime.16,18,24,36,39

However,to ensureconsistency

in the times for listeningto music, the researchermade

one follow-up phonecall per week after the interviewto

remindparticipantsto listen to the musiconce a day. All

the data collection, includingadministeringthe interven-

tion and collectingthe data, was carried out by the same

researcher.

Thecontrolgroup

Participantsin the controlgroupmet the researcherfor the

samenumberof times as those in the interventiongroup.

Participantsin the control group were given an uninter-

ruptedrest period, but the samedata were collectedonce

a week for 6 weeks.The researchermet them only to col-

lect their sleep quality scores. The researcherrequested

participants,duringthe studyperiod,to not listen to seda-

tive music, but we could not restrict them from listening

to radio or TV. Duringdata collection,the researchermin-

imizedinteractionwith this groupof participants,so as to

reduceresultcontaminationandhenceincreasethe reliabil-

ity of the results.All the data collectionwascarriedout by

the sameresearcher.Everyweek,the researchervisitedthe

participantsandaskedthemwhethertheytookanymedica-

tions to changetheir sleeppatternsand noneof them had

takenanymedications.

Randomization

Two cards were put inside a bag in each draw, with one

labelled as ‘‘intervention’’ and the other as ‘‘control’’.

Each participantwas askedto draw one card from the bag

to allocatehim or her into either the interventionor con-

trol group. There was no blindingas the participantsand

interviewerknewthe allocationgroupsafter randomization.

Selectionof music

Recentstudieshaveshownthat givingparticipantsa choice

of musiclowersanxiety,promotesrelaxation,and leadsto

effective treatment.14,16,21,22Therefore,a varietyof relax-

ation music was provided by the research team based

on previousstudies. A diverse range of music has been

utilized in researchstudiesto investigateits therapeutic

effectiveness.SomegenresincludeWesternclassic(Bach:

Allemande,Sarabande;Mozart:Romancefrom Eine Kleine

Nachtmusik1; Chopin:Nocturne2), Chineseclassic(Spring

Riverin the Moonlight,Variationon YangPass),andNewAge

(Shizuku,Lordof Wind),andJazz (Everlasting,WinterWon-

derland,In Lovein Vain).All musiccompositionswere soft,

instrumental,slow musicwithout lyrics, of approximately

60—80beats per minute, for 40min duration.16,18 These

characteristicswere in accordancewith the Gaston’sdef-

inition of sedativemusicthat is expectedto evokerelaxing

effectsin the listener.41 Theywereall musiccompositionsof

variousgenreswith relaxationpotential.Participantswere

allowedto select the type of musicto listen to duringthe

studyperiods,from a list of musicprovidedby the research

team, basedon their personalpreferences.Sixparticipants

choseWesternclassic,15 participantschoseChineseclas-

sic, four participantschoseNewAge,andthreeparticipants

choseJazz music.

Statisticalanalysis

Descriptivestatisticswereusedto describethe characteris-

tics of all participantswhosuccessfullycompletedthe study.

Generalizedestimatingequations(GEE)wereusedto exam-

ine the effectsof the interventionon the elders’sleeplevel.

GEEshave becomean importantanalysismethodand are

robustin the analysisof longitudinaldata, in whichpartici-

pantsaremeasuredat differentpointsin time.29 All analyses

were undertakenusingIBMSPSSv20andall statisticaltests

were set at a significancelevel of p <0.05.

Results

Participantcharacteristics

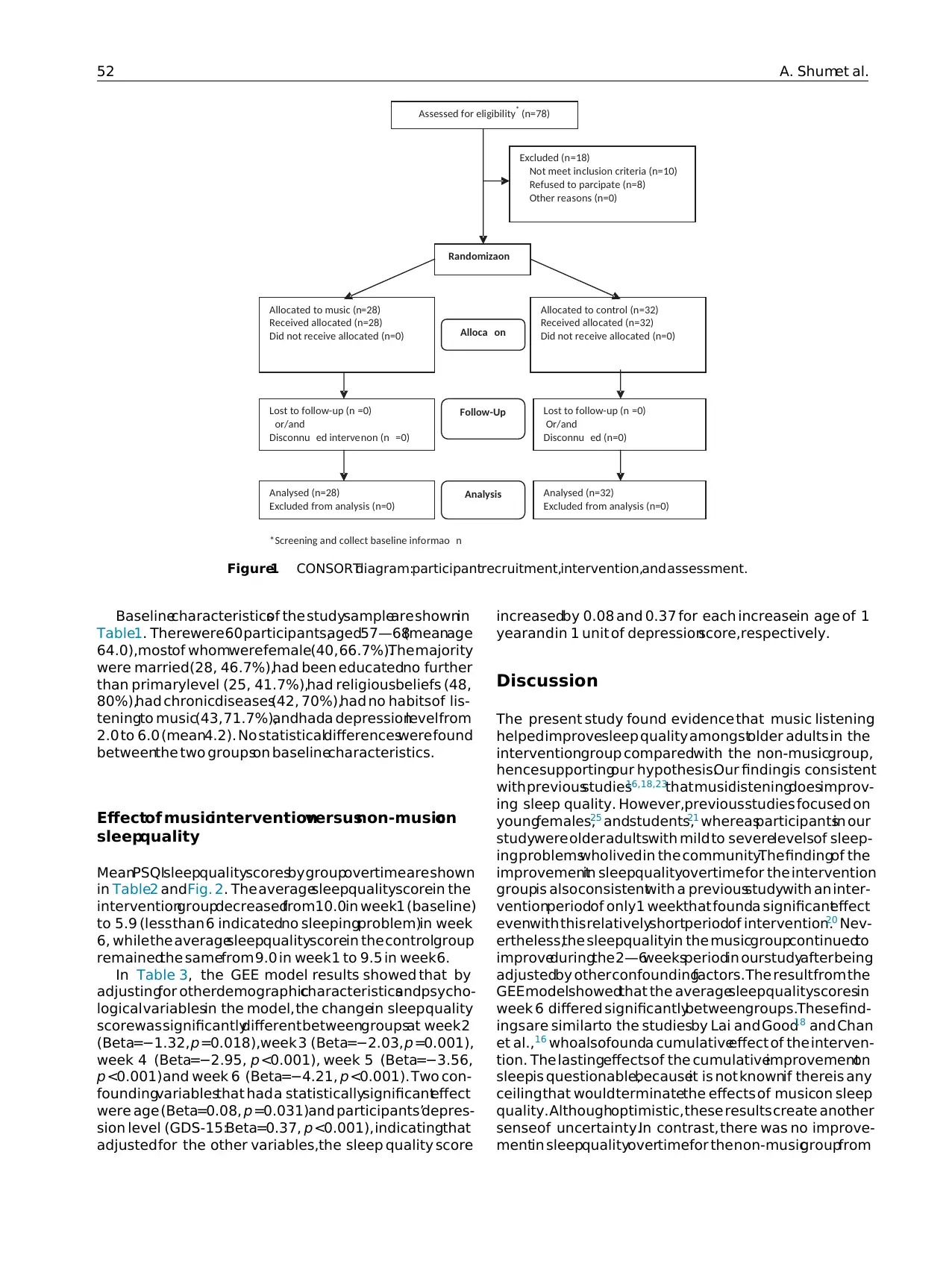

Over the study period, 78 potential participants were

contacted,eight participantsrefusedto participateafter

receivingmoreinformationaboutthe study.Tenparticipants

were disqualifiedbecausenine had baselinePSQI scores

that were below six and one had hearingdifficulties. The

remaining60 participantswere randomlyallocatedinto the

intervention(n =28)andcontrolgroups(n =32)andall com-

pletedthe study(Fig. 1).

controlgroup,datawerecollectedoncea weekfor the same

6 weeks as the interventiongroup, when the researcher

visitedthemat home.

Themusicintervention

The processof musicinterventiontook place in each par-

ticipant’shome.After the randomallocationof participants

to groups,weeklyvisitswere madefor 6 weeksto measure

the sameoutcomes.Six weeksis a recommendedperiodof

time for observingsleep patterns,16,23 and the effects of

a new interventionon sleep quality.14 Participantsin the

experimentalgroupwere providedwith an MP4playerwith

earphonesin order to listen to the music of their choice

from a selection of soft, slow music without lyrics (for

details,pleaseseethe sectionon Selectionof music).Previ-

ous literaturehas shownsubjectiveand scientificevidence

in demonstratingthat music preferenceis a key element

in derivingbeneficialbenefitsfrom music.16,18,36Therefore,

participantswere allowedto choosetheir preferredmusic

and they were requiredto adhereto the use of a single

genreof musicwithin the sameweek, to minimizepossi-

ble variancesin the effect on sleep quality. Participants

were also told to choosethe most comfortableplace to

listen to the music, for examplein their bedroom.Stan-

dardizedinstructionswere givento the participantsas per

a protocol proposedby Chan et al.16 The researcherleft

the participantsalone and stayed a short distanceaway

unobtrusively,so that she or he could be availablefor any

unexpectedresponse.After 40min, the researcherstopped

the music and then collected all outcomesfor each par-

ticipant within a 10—15min conversation.Previousstudies

havesuggestedthat listeningto musiceverydaycontributes

to a better sleep at night, even if it is not consistently

heardat bedtime.16,18,24,36,39

However,to ensureconsistency

in the times for listeningto music, the researchermade

one follow-up phonecall per week after the interviewto

remindparticipantsto listen to the musiconce a day. All

the data collection, includingadministeringthe interven-

tion and collectingthe data, was carried out by the same

researcher.

Thecontrolgroup

Participantsin the controlgroupmet the researcherfor the

samenumberof times as those in the interventiongroup.

Participantsin the control group were given an uninter-

ruptedrest period, but the samedata were collectedonce

a week for 6 weeks.The researchermet them only to col-

lect their sleep quality scores. The researcherrequested

participants,duringthe studyperiod,to not listen to seda-

tive music, but we could not restrict them from listening

to radio or TV. Duringdata collection,the researchermin-

imizedinteractionwith this groupof participants,so as to

reduceresultcontaminationandhenceincreasethe reliabil-

ity of the results.All the data collectionwascarriedout by

the sameresearcher.Everyweek,the researchervisitedthe

participantsandaskedthemwhethertheytookanymedica-

tions to changetheir sleeppatternsand noneof them had

takenanymedications.

Randomization

Two cards were put inside a bag in each draw, with one

labelled as ‘‘intervention’’ and the other as ‘‘control’’.

Each participantwas askedto draw one card from the bag

to allocatehim or her into either the interventionor con-

trol group. There was no blindingas the participantsand

interviewerknewthe allocationgroupsafter randomization.

Selectionof music

Recentstudieshaveshownthat givingparticipantsa choice

of musiclowersanxiety,promotesrelaxation,and leadsto

effective treatment.14,16,21,22Therefore,a varietyof relax-

ation music was provided by the research team based

on previousstudies. A diverse range of music has been

utilized in researchstudiesto investigateits therapeutic

effectiveness.SomegenresincludeWesternclassic(Bach:

Allemande,Sarabande;Mozart:Romancefrom Eine Kleine

Nachtmusik1; Chopin:Nocturne2), Chineseclassic(Spring

Riverin the Moonlight,Variationon YangPass),andNewAge

(Shizuku,Lordof Wind),andJazz (Everlasting,WinterWon-

derland,In Lovein Vain).All musiccompositionswere soft,

instrumental,slow musicwithout lyrics, of approximately

60—80beats per minute, for 40min duration.16,18 These

characteristicswere in accordancewith the Gaston’sdef-

inition of sedativemusicthat is expectedto evokerelaxing

effectsin the listener.41 Theywereall musiccompositionsof

variousgenreswith relaxationpotential.Participantswere

allowedto select the type of musicto listen to duringthe

studyperiods,from a list of musicprovidedby the research

team, basedon their personalpreferences.Sixparticipants

choseWesternclassic,15 participantschoseChineseclas-

sic, four participantschoseNewAge,andthreeparticipants

choseJazz music.

Statisticalanalysis

Descriptivestatisticswereusedto describethe characteris-

tics of all participantswhosuccessfullycompletedthe study.

Generalizedestimatingequations(GEE)wereusedto exam-

ine the effectsof the interventionon the elders’sleeplevel.

GEEshave becomean importantanalysismethodand are

robustin the analysisof longitudinaldata, in whichpartici-

pantsaremeasuredat differentpointsin time.29 All analyses

were undertakenusingIBMSPSSv20andall statisticaltests

were set at a significancelevel of p <0.05.

Results

Participantcharacteristics

Over the study period, 78 potential participants were

contacted,eight participantsrefusedto participateafter

receivingmoreinformationaboutthe study.Tenparticipants

were disqualifiedbecausenine had baselinePSQI scores

that were below six and one had hearingdifficulties. The

remaining60 participantswere randomlyallocatedinto the

intervention(n =28)andcontrolgroups(n =32)andall com-

pletedthe study(Fig. 1).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

52 A. Shumet al.

Assessed for eligibil ity* (n=78)

Excluded (n =18)

Not meet in clusion criteria (n= 10)

Refused to parcipate (n=8)

Other rea sons (n=0)

Analysed (n=28)

Excluded from analysis (n=0)

Lost to follow-up (n =0)

or/and

Disconnu ed interve non (n =0)

Allocated to music (n=28)

Received allocated (n=28)

Did not re ceive allocated (n=0)

Lost to follow-up (n =0)

Or/and

Disconnu ed (n=0)

Allocated to control (n =32)

Received allo cated (n=32)

Did not re ceive allocated (n=0)

Analysed (n=32)

Excluded from analysis (n=0)

Alloca on

Analysis

Follow-Up

Randomizaon

*Screening an d collect baseline info rmao n

Figure1 CONSORTdiagram:participantrecruitment,intervention,and assessment.

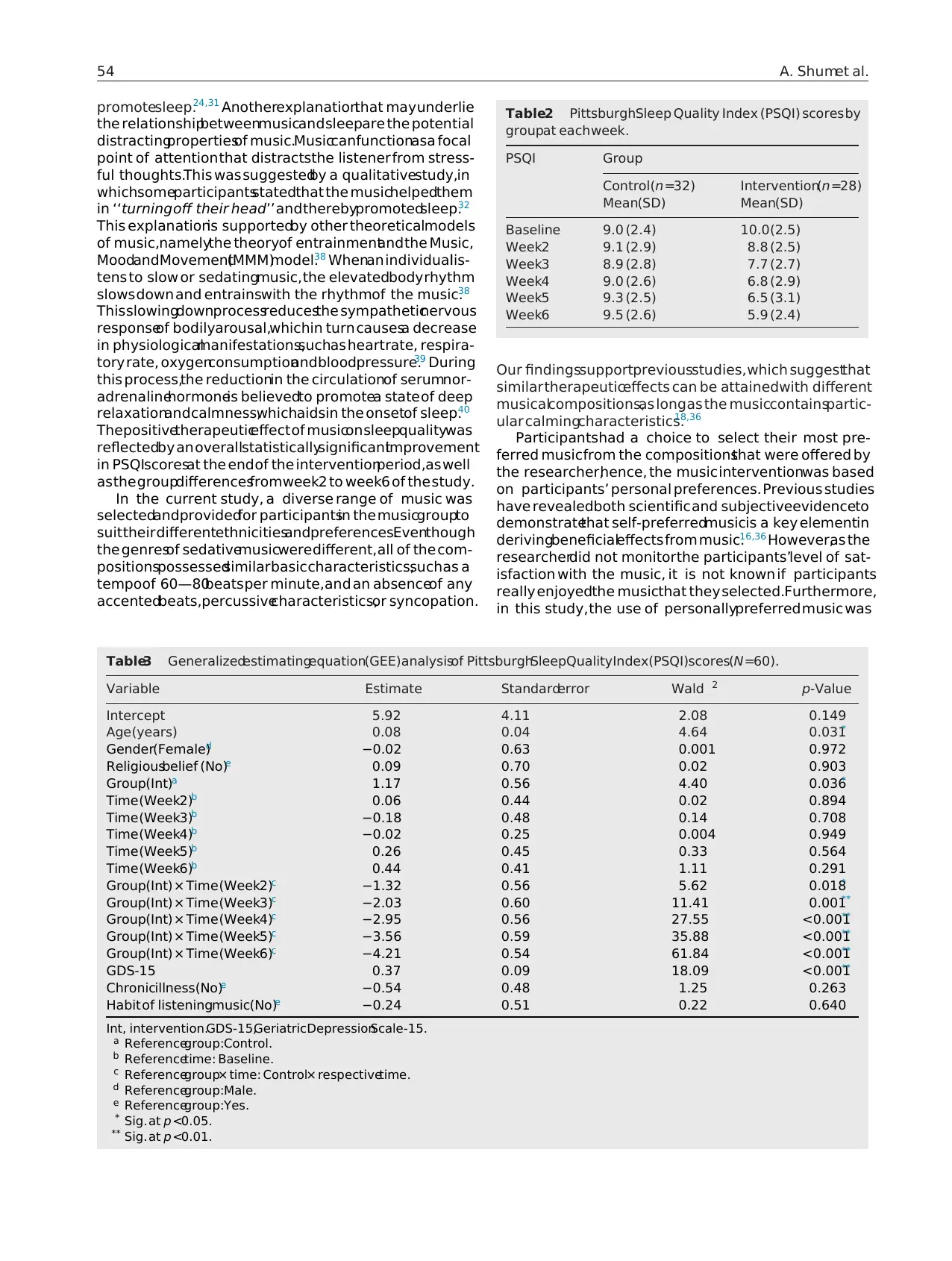

Baselinecharacteristicsof the studysampleare shownin

Table1. Therewere 60 participants,aged57—68(meanage

64.0),mostof whomwerefemale(40, 66.7%).The majority

were married(28, 46.7%),had been educatedno further

than primarylevel (25, 41.7%),had religiousbeliefs (48,

80%),had chronicdiseases(42, 70%),had no habitsof lis-

teningto music(43, 71.7%),andhada depressionlevel from

2.0 to 6.0 (mean4.2). No statisticaldifferenceswere found

betweenthe two groupson baselinecharacteristics.

Effectof musicinterventionversusnon-musicon

sleepquality

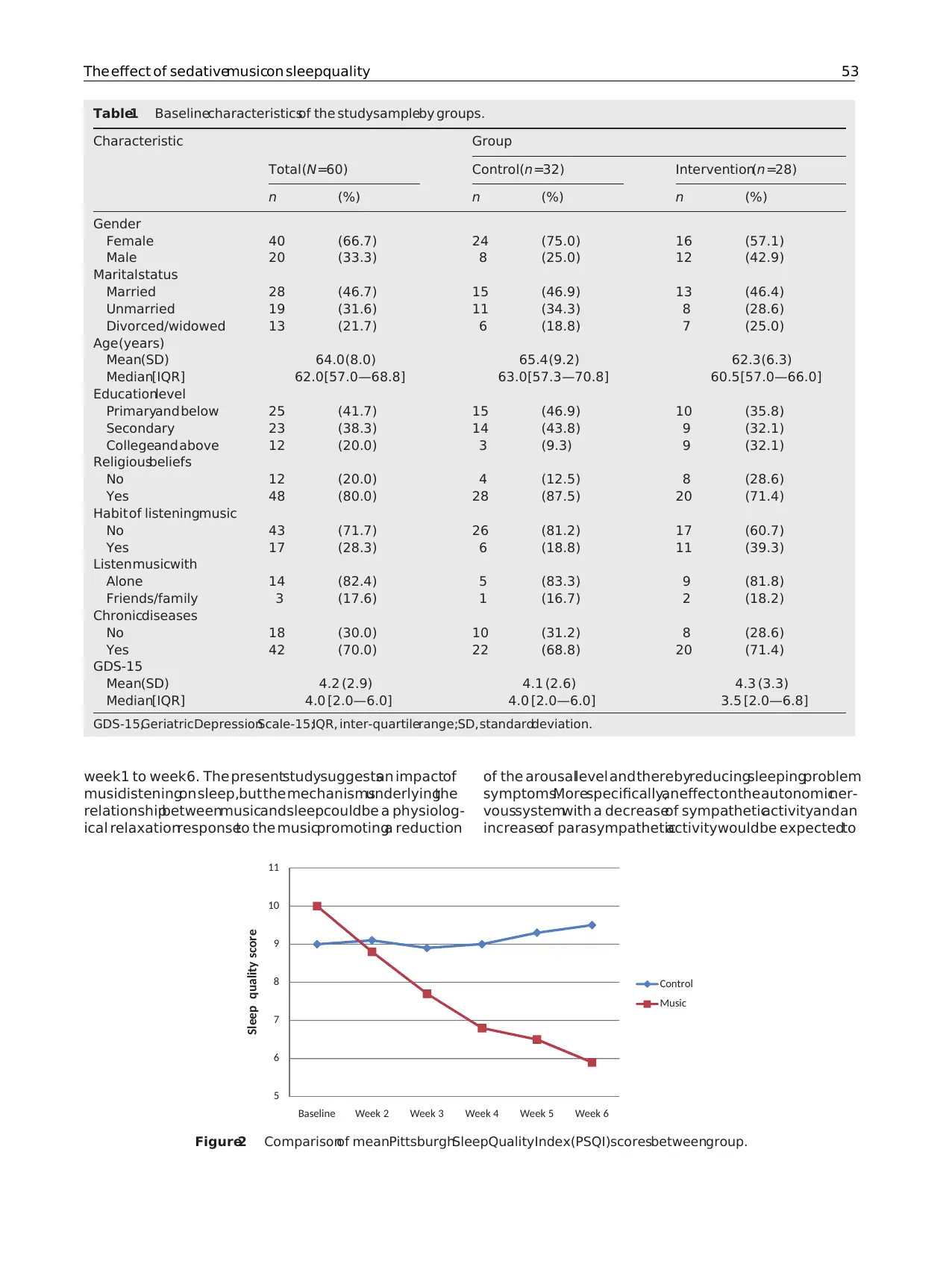

MeanPSQIsleepqualityscoresby groupovertimeare shown

in Table2 andFig. 2. The averagesleepqualityscorein the

interventiongroupdecreasedfrom10.0in week1 (baseline)

to 5.9 (less than 6 indicatedno sleepingproblem)in week

6, whilethe averagesleepqualityscorein the controlgroup

remainedthe samefrom 9.0 in week1 to 9.5 in week6.

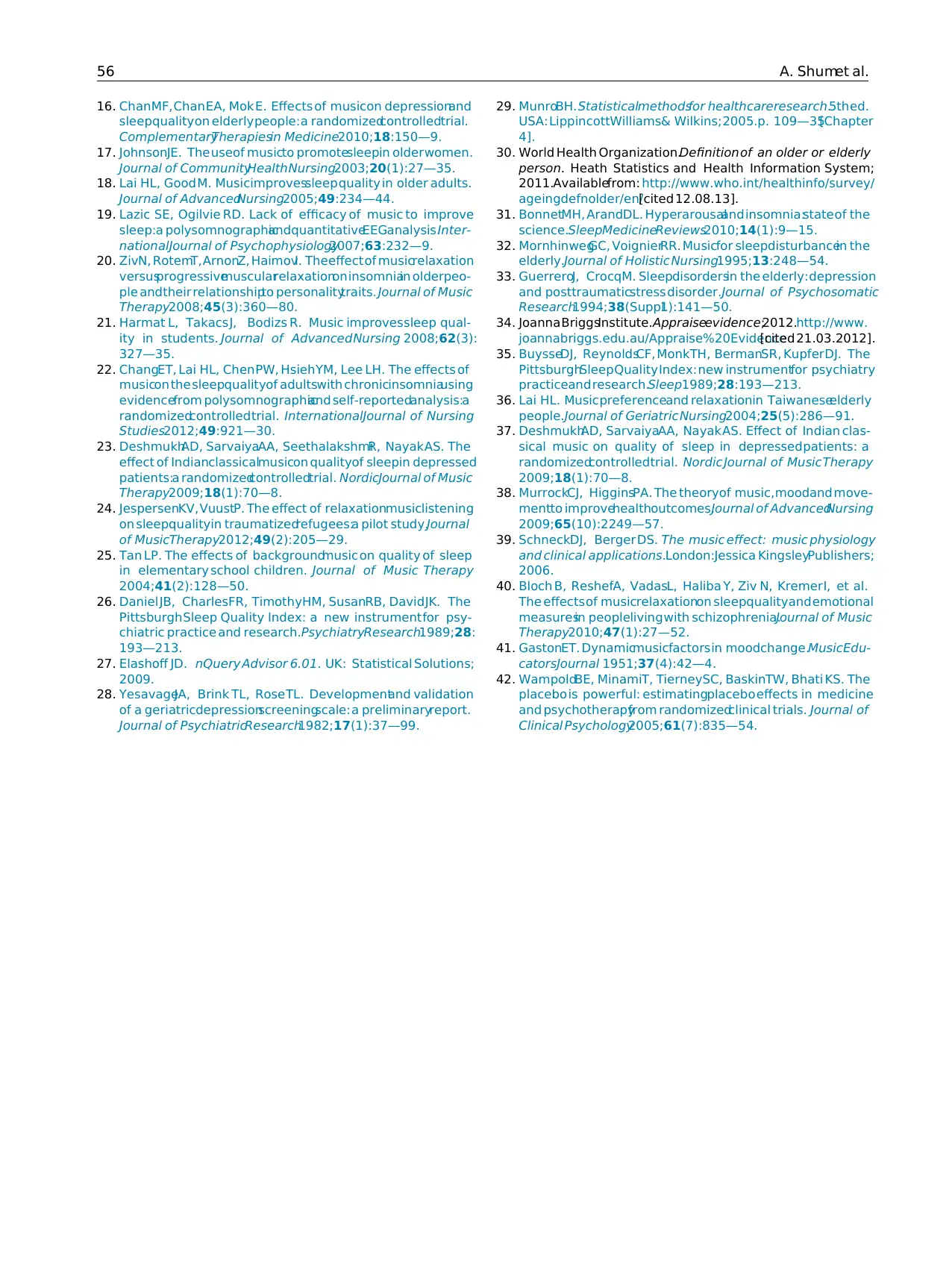

In Table 3, the GEE model results showed that by

adjustingfor otherdemographiccharacteristicsandpsycho-

logical variablesin the model, the changein sleep quality

scorewas significantlydifferent betweengroupsat week2

(Beta=−1.32, p =0.018),week 3 (Beta=−2.03, p =0.001),

week 4 (Beta=−2.95, p <0.001), week 5 (Beta=−3.56,

p <0.001)and week 6 (Beta=−4.21, p <0.001). Two con-

foundingvariablesthat had a statisticallysignificanteffect

were age (Beta=0.08, p =0.031)and participants’depres-

sion level (GDS-15:Beta=0.37, p <0.001), indicatingthat

adjusted for the other variables,the sleep quality score

increasedby 0.08 and 0.37 for each increasein age of 1

yearand in 1 unit of depressionscore,respectively.

Discussion

The present study found evidence that music listening

helped improvesleep quality amongstolder adults in the

interventiongroup comparedwith the non-musicgroup,

hencesupportingour hypothesis.Our findingis consistent

with previousstudies16,18,23

that musiclisteningdoesimprov-

ing sleep quality. However,previousstudies focused on

youngfemales,25 andstudents,21 whereasparticipantsin our

studywere older adultswith mild to severelevelsof sleep-

ing problemswholived in the community.The findingof the

improvementin sleepqualityovertime for the intervention

groupis alsoconsistentwith a previousstudywith an inter-

ventionperiodof only1 weekthat founda significanteffect

evenwith this relativelyshortperiodof intervention.20 Nev-

ertheless,the sleepqualityin the musicgroupcontinuedto

improveduringthe 2—6weeksperiodin ourstudyafter being

adjustedby other confoundingfactors. The resultfrom the

GEE modelshowedthat the averagesleepqualityscoresin

week 6 differed significantlybetweengroups.These find-

ingsare similarto the studiesby Lai and Good18 and Chan

et al.,16 whoalsofounda cumulativeeffect of the interven-

tion. The lastingeffects of the cumulativeimprovementon

sleepis questionable,becauseit is not knownif thereis any

ceilingthat would terminatethe effects of musicon sleep

quality. Althoughoptimistic, these results create another

senseof uncertainty.In contrast, there was no improve-

mentin sleepqualityovertimefor the non-musicgroupfrom

Assessed for eligibil ity* (n=78)

Excluded (n =18)

Not meet in clusion criteria (n= 10)

Refused to parcipate (n=8)

Other rea sons (n=0)

Analysed (n=28)

Excluded from analysis (n=0)

Lost to follow-up (n =0)

or/and

Disconnu ed interve non (n =0)

Allocated to music (n=28)

Received allocated (n=28)

Did not re ceive allocated (n=0)

Lost to follow-up (n =0)

Or/and

Disconnu ed (n=0)

Allocated to control (n =32)

Received allo cated (n=32)

Did not re ceive allocated (n=0)

Analysed (n=32)

Excluded from analysis (n=0)

Alloca on

Analysis

Follow-Up

Randomizaon

*Screening an d collect baseline info rmao n

Figure1 CONSORTdiagram:participantrecruitment,intervention,and assessment.

Baselinecharacteristicsof the studysampleare shownin

Table1. Therewere 60 participants,aged57—68(meanage

64.0),mostof whomwerefemale(40, 66.7%).The majority

were married(28, 46.7%),had been educatedno further

than primarylevel (25, 41.7%),had religiousbeliefs (48,

80%),had chronicdiseases(42, 70%),had no habitsof lis-

teningto music(43, 71.7%),andhada depressionlevel from

2.0 to 6.0 (mean4.2). No statisticaldifferenceswere found

betweenthe two groupson baselinecharacteristics.

Effectof musicinterventionversusnon-musicon

sleepquality

MeanPSQIsleepqualityscoresby groupovertimeare shown

in Table2 andFig. 2. The averagesleepqualityscorein the

interventiongroupdecreasedfrom10.0in week1 (baseline)

to 5.9 (less than 6 indicatedno sleepingproblem)in week

6, whilethe averagesleepqualityscorein the controlgroup

remainedthe samefrom 9.0 in week1 to 9.5 in week6.

In Table 3, the GEE model results showed that by

adjustingfor otherdemographiccharacteristicsandpsycho-

logical variablesin the model, the changein sleep quality

scorewas significantlydifferent betweengroupsat week2

(Beta=−1.32, p =0.018),week 3 (Beta=−2.03, p =0.001),

week 4 (Beta=−2.95, p <0.001), week 5 (Beta=−3.56,

p <0.001)and week 6 (Beta=−4.21, p <0.001). Two con-

foundingvariablesthat had a statisticallysignificanteffect

were age (Beta=0.08, p =0.031)and participants’depres-

sion level (GDS-15:Beta=0.37, p <0.001), indicatingthat

adjusted for the other variables,the sleep quality score

increasedby 0.08 and 0.37 for each increasein age of 1

yearand in 1 unit of depressionscore,respectively.

Discussion

The present study found evidence that music listening

helped improvesleep quality amongstolder adults in the

interventiongroup comparedwith the non-musicgroup,

hencesupportingour hypothesis.Our findingis consistent

with previousstudies16,18,23

that musiclisteningdoesimprov-

ing sleep quality. However,previousstudies focused on

youngfemales,25 andstudents,21 whereasparticipantsin our

studywere older adultswith mild to severelevelsof sleep-

ing problemswholived in the community.The findingof the

improvementin sleepqualityovertime for the intervention

groupis alsoconsistentwith a previousstudywith an inter-

ventionperiodof only1 weekthat founda significanteffect

evenwith this relativelyshortperiodof intervention.20 Nev-

ertheless,the sleepqualityin the musicgroupcontinuedto

improveduringthe 2—6weeksperiodin ourstudyafter being

adjustedby other confoundingfactors. The resultfrom the

GEE modelshowedthat the averagesleepqualityscoresin

week 6 differed significantlybetweengroups.These find-

ingsare similarto the studiesby Lai and Good18 and Chan

et al.,16 whoalsofounda cumulativeeffect of the interven-

tion. The lastingeffects of the cumulativeimprovementon

sleepis questionable,becauseit is not knownif thereis any

ceilingthat would terminatethe effects of musicon sleep

quality. Althoughoptimistic, these results create another

senseof uncertainty.In contrast, there was no improve-

mentin sleepqualityovertimefor the non-musicgroupfrom

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The effect of sedativemusicon sleepquality 53

Table1 Baselinecharacteristicsof the studysampleby groups.

Characteristic Group

Total (N =60) Control(n =32) Intervention(n =28)

n (%) n (%) n (%)

Gender

Female 40 (66.7) 24 (75.0) 16 (57.1)

Male 20 (33.3) 8 (25.0) 12 (42.9)

Maritalstatus

Married 28 (46.7) 15 (46.9) 13 (46.4)

Unmarried 19 (31.6) 11 (34.3) 8 (28.6)

Divorced/widowed 13 (21.7) 6 (18.8) 7 (25.0)

Age(years)

Mean(SD) 64.0 (8.0) 65.4 (9.2) 62.3 (6.3)

Median[IQR] 62.0[57.0—68.8] 63.0[57.3—70.8] 60.5 [57.0—66.0]

Educationlevel

Primaryand below 25 (41.7) 15 (46.9) 10 (35.8)

Secondary 23 (38.3) 14 (43.8) 9 (32.1)

Collegeand above 12 (20.0) 3 (9.3) 9 (32.1)

Religiousbeliefs

No 12 (20.0) 4 (12.5) 8 (28.6)

Yes 48 (80.0) 28 (87.5) 20 (71.4)

Habit of listeningmusic

No 43 (71.7) 26 (81.2) 17 (60.7)

Yes 17 (28.3) 6 (18.8) 11 (39.3)

Listenmusicwith

Alone 14 (82.4) 5 (83.3) 9 (81.8)

Friends/family 3 (17.6) 1 (16.7) 2 (18.2)

Chronicdiseases

No 18 (30.0) 10 (31.2) 8 (28.6)

Yes 42 (70.0) 22 (68.8) 20 (71.4)

GDS-15

Mean(SD) 4.2 (2.9) 4.1 (2.6) 4.3 (3.3)

Median[IQR] 4.0 [2.0—6.0] 4.0 [2.0—6.0] 3.5 [2.0—6.8]

GDS-15,GeriatricDepressionScale-15;IQR, inter-quartilerange;SD, standarddeviation.

week1 to week6. The presentstudysuggestsan impactof

musiclisteningon sleep,but the mechanismsunderlyingthe

relationshipbetweenmusicandsleepcouldbe a physiolog-

ical relaxationresponseto the musicpromotinga reduction

of the arousallevel and therebyreducingsleepingproblem

symptoms.Morespecifically,aneffect onthe autonomicner-

voussystemwith a decreaseof sympatheticactivityand an

increaseof parasympatheticactivitywouldbe expectedto

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

WeekBaseline Week2 Week3 Week4 Week5 6

Sleep quality score

Control

Music

Figure2 Comparisonof meanPittsburghSleepQualityIndex(PSQI)scoresbetweengroup.

Table1 Baselinecharacteristicsof the studysampleby groups.

Characteristic Group

Total (N =60) Control(n =32) Intervention(n =28)

n (%) n (%) n (%)

Gender

Female 40 (66.7) 24 (75.0) 16 (57.1)

Male 20 (33.3) 8 (25.0) 12 (42.9)

Maritalstatus

Married 28 (46.7) 15 (46.9) 13 (46.4)

Unmarried 19 (31.6) 11 (34.3) 8 (28.6)

Divorced/widowed 13 (21.7) 6 (18.8) 7 (25.0)

Age(years)

Mean(SD) 64.0 (8.0) 65.4 (9.2) 62.3 (6.3)

Median[IQR] 62.0[57.0—68.8] 63.0[57.3—70.8] 60.5 [57.0—66.0]

Educationlevel

Primaryand below 25 (41.7) 15 (46.9) 10 (35.8)

Secondary 23 (38.3) 14 (43.8) 9 (32.1)

Collegeand above 12 (20.0) 3 (9.3) 9 (32.1)

Religiousbeliefs

No 12 (20.0) 4 (12.5) 8 (28.6)

Yes 48 (80.0) 28 (87.5) 20 (71.4)

Habit of listeningmusic

No 43 (71.7) 26 (81.2) 17 (60.7)

Yes 17 (28.3) 6 (18.8) 11 (39.3)

Listenmusicwith

Alone 14 (82.4) 5 (83.3) 9 (81.8)

Friends/family 3 (17.6) 1 (16.7) 2 (18.2)

Chronicdiseases

No 18 (30.0) 10 (31.2) 8 (28.6)

Yes 42 (70.0) 22 (68.8) 20 (71.4)

GDS-15

Mean(SD) 4.2 (2.9) 4.1 (2.6) 4.3 (3.3)

Median[IQR] 4.0 [2.0—6.0] 4.0 [2.0—6.0] 3.5 [2.0—6.8]

GDS-15,GeriatricDepressionScale-15;IQR, inter-quartilerange;SD, standarddeviation.

week1 to week6. The presentstudysuggestsan impactof

musiclisteningon sleep,but the mechanismsunderlyingthe

relationshipbetweenmusicandsleepcouldbe a physiolog-

ical relaxationresponseto the musicpromotinga reduction

of the arousallevel and therebyreducingsleepingproblem

symptoms.Morespecifically,aneffect onthe autonomicner-

voussystemwith a decreaseof sympatheticactivityand an

increaseof parasympatheticactivitywouldbe expectedto

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

WeekBaseline Week2 Week3 Week4 Week5 6

Sleep quality score

Control

Music

Figure2 Comparisonof meanPittsburghSleepQualityIndex(PSQI)scoresbetweengroup.

54 A. Shumet al.

promotesleep.24,31 Anotherexplanationthat may underlie

the relationshipbetweenmusicand sleepare the potential

distractingpropertiesof music.Musiccanfunctionasa focal

point of attention that distractsthe listener from stress-

ful thoughts.This was suggestedby a qualitativestudy,in

whichsomeparticipantsstatedthat the musichelpedthem

in ‘‘turning off their head’’ and therebypromotedsleep.32

This explanationis supportedby other theoreticalmodels

of music,namelythe theoryof entrainmentand the Music,

MoodandMovement(MMM)model.38 Whenan individuallis-

tens to slow or sedatingmusic, the elevatedbody rhythm

slows down and entrainswith the rhythmof the music.38

This slowingdownprocessreducesthe sympatheticnervous

responseof bodilyarousal,whichin turn causesa decrease

in physiologicalmanifestations,suchas heartrate, respira-

tory rate, oxygenconsumptionandbloodpressure.39 During

this process,the reductionin the circulationof serumnor-

adrenalinehormoneis believedto promotea state of deep

relaxationandcalmness,whichaidsin the onsetof sleep.40

Thepositivetherapeuticeffect of musicon sleepqualitywas

reflectedby an overallstatisticallysignificantimprovement

in PSQIscoresat the end of the interventionperiod,as well

as the groupdifferencesfromweek2 to week6 of the study.

In the current study, a diverse range of music was

selectedandprovidedfor participantsin the musicgroupto

suittheir differentethnicitiesandpreferences.Eventhough

the genresof sedativemusicwere different,all of the com-

positionspossessedsimilar basiccharacteristics,such as a

tempoof 60—80beats per minute,and an absenceof any

accentedbeats,percussivecharacteristics,or syncopation.

Table2 PittsburghSleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores by

groupat each week.

PSQI Group

Control(n =32) Intervention(n =28)

Mean(SD) Mean(SD)

Baseline 9.0 (2.4) 10.0(2.5)

Week2 9.1 (2.9) 8.8 (2.5)

Week3 8.9 (2.8) 7.7 (2.7)

Week4 9.0 (2.6) 6.8 (2.9)

Week5 9.3 (2.5) 6.5 (3.1)

Week6 9.5 (2.6) 5.9 (2.4)

Our findingssupportpreviousstudies, which suggestthat

similar therapeuticeffects can be attainedwith different

musicalcompositions,as long as the musiccontainspartic-

ular calmingcharacteristics.18,36

Participantshad a choice to select their most pre-

ferred musicfrom the compositionsthat were offered by

the researcher,hence, the music interventionwas based

on participants’ personal preferences. Previous studies

have revealedboth scientific and subjectiveevidenceto

demonstratethat self-preferredmusicis a key elementin

derivingbeneficialeffects from music.16,36 However,as the

researcherdid not monitorthe participants’level of sat-

isfaction with the music, it is not known if participants

really enjoyedthe musicthat they selected.Furthermore,

in this study, the use of personallypreferred music was

Table3 Generalizedestimatingequation(GEE)analysisof PittsburghSleepQualityIndex(PSQI)scores(N =60).

Variable Estimate Standarderror Wald 2 p-Value

Intercept 5.92 4.11 2.08 0.149

Age (years) 0.08 0.04 4.64 0.031*

Gender(Female)d −0.02 0.63 0.001 0.972

Religiousbelief (No)e 0.09 0.70 0.02 0.903

Group(Int)a 1.17 0.56 4.40 0.036*

Time (Week2)b 0.06 0.44 0.02 0.894

Time (Week3)b −0.18 0.48 0.14 0.708

Time (Week4)b −0.02 0.25 0.004 0.949

Time (Week5)b 0.26 0.45 0.33 0.564

Time (Week6)b 0.44 0.41 1.11 0.291

Group(Int) × Time (Week2)c −1.32 0.56 5.62 0.018*

Group(Int) × Time (Week3)c −2.03 0.60 11.41 0.001**

Group(Int) × Time (Week4)c −2.95 0.56 27.55 <0.001**

Group(Int) × Time (Week5)c −3.56 0.59 35.88 <0.001**

Group(Int) × Time (Week6)c −4.21 0.54 61.84 <0.001**

GDS-15 0.37 0.09 18.09 <0.001**

Chronicillness(No)e −0.54 0.48 1.25 0.263

Habit of listeningmusic(No)e −0.24 0.51 0.22 0.640

Int, intervention.GDS-15,GeriatricDepressionScale-15.

a Referencegroup:Control.

b Referencetime: Baseline.

c Referencegroup× time: Control× respectivetime.

d Referencegroup:Male.

e Referencegroup:Yes.

* Sig. at p <0.05.

** Sig. at p <0.01.

promotesleep.24,31 Anotherexplanationthat may underlie

the relationshipbetweenmusicand sleepare the potential

distractingpropertiesof music.Musiccanfunctionasa focal

point of attention that distractsthe listener from stress-

ful thoughts.This was suggestedby a qualitativestudy,in

whichsomeparticipantsstatedthat the musichelpedthem

in ‘‘turning off their head’’ and therebypromotedsleep.32

This explanationis supportedby other theoreticalmodels

of music,namelythe theoryof entrainmentand the Music,

MoodandMovement(MMM)model.38 Whenan individuallis-

tens to slow or sedatingmusic, the elevatedbody rhythm

slows down and entrainswith the rhythmof the music.38

This slowingdownprocessreducesthe sympatheticnervous

responseof bodilyarousal,whichin turn causesa decrease

in physiologicalmanifestations,suchas heartrate, respira-

tory rate, oxygenconsumptionandbloodpressure.39 During

this process,the reductionin the circulationof serumnor-

adrenalinehormoneis believedto promotea state of deep

relaxationandcalmness,whichaidsin the onsetof sleep.40

Thepositivetherapeuticeffect of musicon sleepqualitywas

reflectedby an overallstatisticallysignificantimprovement

in PSQIscoresat the end of the interventionperiod,as well

as the groupdifferencesfromweek2 to week6 of the study.

In the current study, a diverse range of music was

selectedandprovidedfor participantsin the musicgroupto

suittheir differentethnicitiesandpreferences.Eventhough

the genresof sedativemusicwere different,all of the com-

positionspossessedsimilar basiccharacteristics,such as a

tempoof 60—80beats per minute,and an absenceof any

accentedbeats,percussivecharacteristics,or syncopation.

Table2 PittsburghSleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores by

groupat each week.

PSQI Group

Control(n =32) Intervention(n =28)

Mean(SD) Mean(SD)

Baseline 9.0 (2.4) 10.0(2.5)

Week2 9.1 (2.9) 8.8 (2.5)

Week3 8.9 (2.8) 7.7 (2.7)

Week4 9.0 (2.6) 6.8 (2.9)

Week5 9.3 (2.5) 6.5 (3.1)

Week6 9.5 (2.6) 5.9 (2.4)

Our findingssupportpreviousstudies, which suggestthat

similar therapeuticeffects can be attainedwith different

musicalcompositions,as long as the musiccontainspartic-

ular calmingcharacteristics.18,36

Participantshad a choice to select their most pre-

ferred musicfrom the compositionsthat were offered by

the researcher,hence, the music interventionwas based

on participants’ personal preferences. Previous studies

have revealedboth scientific and subjectiveevidenceto

demonstratethat self-preferredmusicis a key elementin

derivingbeneficialeffects from music.16,36 However,as the

researcherdid not monitorthe participants’level of sat-

isfaction with the music, it is not known if participants

really enjoyedthe musicthat they selected.Furthermore,

in this study, the use of personallypreferred music was

Table3 Generalizedestimatingequation(GEE)analysisof PittsburghSleepQualityIndex(PSQI)scores(N =60).

Variable Estimate Standarderror Wald 2 p-Value

Intercept 5.92 4.11 2.08 0.149

Age (years) 0.08 0.04 4.64 0.031*

Gender(Female)d −0.02 0.63 0.001 0.972

Religiousbelief (No)e 0.09 0.70 0.02 0.903

Group(Int)a 1.17 0.56 4.40 0.036*

Time (Week2)b 0.06 0.44 0.02 0.894

Time (Week3)b −0.18 0.48 0.14 0.708

Time (Week4)b −0.02 0.25 0.004 0.949

Time (Week5)b 0.26 0.45 0.33 0.564

Time (Week6)b 0.44 0.41 1.11 0.291

Group(Int) × Time (Week2)c −1.32 0.56 5.62 0.018*

Group(Int) × Time (Week3)c −2.03 0.60 11.41 0.001**

Group(Int) × Time (Week4)c −2.95 0.56 27.55 <0.001**

Group(Int) × Time (Week5)c −3.56 0.59 35.88 <0.001**

Group(Int) × Time (Week6)c −4.21 0.54 61.84 <0.001**

GDS-15 0.37 0.09 18.09 <0.001**

Chronicillness(No)e −0.54 0.48 1.25 0.263

Habit of listeningmusic(No)e −0.24 0.51 0.22 0.640

Int, intervention.GDS-15,GeriatricDepressionScale-15.

a Referencegroup:Control.

b Referencetime: Baseline.

c Referencegroup× time: Control× respectivetime.

d Referencegroup:Male.

e Referencegroup:Yes.

* Sig. at p <0.05.

** Sig. at p <0.01.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The effect of sedativemusicon sleepquality 55

not comparedagainst the use of a standardizedset of

researcher-selectedmusic.Therefore,eventhoughpositive

resultswereobtained,theycannotbe usedto concludethat

the use of personallypreferredmusicenhancedthe thera-

peuticeffects on sleepquality.

Anotherinterestingfindingwasthat participants’ageand

depressionscoreswerepositivelycorrelatedwith their sleep

quality. Despitethese two factors being correlated with

sleepquality,theydo not affect the musicintervention.Pre-

viousstudieshavefoundthatin olderpopulationsdepression

maybe relatedto insomnia.31,33Althoughthe musicusedfor

this studywasnot directedspecificallytowardsdepression,

it was able to facilitate stressreductionwhenparticipants

weretryingto sleep.Johnson17 suggestedthat patientswith

insomniamay have multiple causesincludingage, stress,

tension, and anxiety,but the mechanismsunderlyingthe

relationshipbetweenstressand sleepremainunclear.

Strengthensandlimitations

This study has two methodologicalstrengths.Firstly, the

presentstudyhadno attrition.Secondly,the presentstudy’s

researchdesigntakes the form of a RCT that providesa

strongerlevel of evidencethan other researchdesignsas

it helps reduceallocationbias.34 Despitethese strengths,

the study has several limitations. Firstly, the samples

were recruitedin one communitycentre that may induce

selectionbias. Secondly,the samplesizes may affect the

generalizabilityof the findings, althoughthe study was

appropriatelypowered to detect a mediumeffect size.

Thirdly,it wasnot possibleto blindparticipantto the exper-

imentalconditionandthereforeonemusttakeinto account

any Hawthorneeffect, which can influencethe perception

of participantsto rate their sleep quality.To explorethe

possibleplacebo-effectswithin the interventiongroup, a

futurestudycouldbe undertakento includeotherinterven-

tion groups,who listen to the natural environment,or to

other musicthat is pleasantto hear,but doesnot resemble

music with sedativecharacteristics.42 Lastly, becausethe

interventionswere conductedfor 6 weeks,other confound-

ing factors (e.g. whetherall participantsheard the same

amountof music within the intervention),that occurred

duringthe week, mayhaveaffectedparticipants’ratingsof

their sleepquality.Thesevariationsare inevitable,because

any attemptsto controltheseconfoundingvariableswould

havebeenpracticallyimpossibleandunethical.

Conclusions

The present study found evidence that music listening

helped improve sleep quality amongstolder adults. The

findingssuggestthat healthcareprofessionals,with ade-

quatetraining,couldengageelderlyclientsin the processof

musiclisteningtherapy.Not only doesthis processimprove

their sleepingqualityat old age, it also individualizesand

enhancesthe quality of care providedby the healthcare

provideras the therapeuticrelationshipbetweenprovider

andclient is beingestablished.Contemporarygerontologyis

progressivelycharacterizedby collaborationsbetweensev-

eral approacheswith the intent to comprehendboth the

mentaland physicalaspectsof the multifariousprocessof

ageing.Musiclisteningis one suchavenueto alleviatesleep

qualityamongstolder adultsand it makesan essentialcon-

tributionto healthyageing.

Contributors

MFC, AS, and JT designedthe study.AS collectedthe data.

MFCandASanalysedthe data.PreparationwasdonebyMFC,

AS, JT, and BJT.

Conflictof intereststatement

Theauthor(s)declarethat theyhaveno conflictof interests.

References

1. NomuraK, YamaokK, NakaoM, YanoE. Socialdeterminantsof

self-reportedsleepproblemsin SouthKoreaand Taiwan.Jour-

nal of PsychosomaticResearch2010;69(5):435—40.

2. RoepkeSK, Ancol-IsraelS. Sleep disordersin elderly. Indian

Journal of MedicalResearch2010;131:302—10.

3. YeungA, ChangD, GreshamJr R, NierenbergAA, FavaM. Illness

beliefsof depressedChineseAmericanpatientsin primarycare.

Journal of Nervousand Mental Disease2004;192(4):324—7.

4. ZahranHS, KobauR, MoriartyDG, Zack MM, Holt J, Donehoo

R. Health-relatedquality of life surveillance— United States,

1993—2002.Morbidity and Mortality WeeklyReport (MMWR)

SurveillanceSummaries2005;54(4):1—35.

5. BlackwellT, Yaffe K, Ancoli-IsraelS, SchneiderJL, CauleyJA,

Hillier TA, et al. Poorsleepis associatedwith impairedcognitive

function in older women:the studyof osteoporoticfractures.

Journal of Gerontology2006;61:405—10.

6. DamTL, EwingSK, Ancoli-IsraelS, EnsrudK, RedlinesSS,Stone

KL. Associationbetweensleep and physicalfunction in older

men: the osteoporoticfracturesin mansleepstudy.Journal of

AmericanGeriatric Society2008;56:1665—73.

7. Butnik SM. Neurofeedbackin adolescentsand adults with

attentiondeficit hyperactivitydisorder.Journal of Clinical Psy-

chology2005;61(5):621—5.

8. RothT, RoehrsT. Pharamcotherapyfor insomnia.SleepMedicine

Clinics 2010;5(4):529—39.

9. DeMartinisNA, Kamath J, Winokur A. New approachesfor

the treatmentof sleep disorders.Advancesin Pharmacology

2009;57:187—235.

10. BuscemiN, VandermeerB, FriesenC, BialyL, TubmanM, Ospina

M, et al. The efficacyand safetyof drugtreatmentsfor chronic

insomniain adults:a meta-analysisof RCTs.Journal of General

Internal Medicine2007;22(9):1335—50.

11. Kozasa EH, Hachul H, MonsonC, Pinto Jr L, Garcia MC, de

AraujoMoraesMLE,et al. Mind-bodyinterventionsfor the treat-

ment of insomnia:a review. Revista Brasileira de Psquiatria

2010;32(4):437—43.

12. Morin CM, Le Blanc M, Daley M, Gregoire JP, Merette C.

Epidemiologyof insomnia:prevalence,self-help treatments,

consultations, and determinatesof self-seeking behaviors.

SleepMedicine2006;7:123—30.

13. MontgomeryP, DennisJ. Brightlight therapyfor sleepproblems

in adults aged60+.CochraneDatabaseof SystematicReviews

2002;2:145—51.

14. de Niet G, TiemensB, LendemeijerB, HutschemaekersG. Music-

assistedrelaxation to improve sleep quality: meta-analysis.

Journal of AdvancedNursing2009;65(7):1356—64.

15. McCaffrey R. Music listening, its effects in creating a

healing environment. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing

2008;46(10):39—44.

not comparedagainst the use of a standardizedset of

researcher-selectedmusic.Therefore,eventhoughpositive

resultswereobtained,theycannotbe usedto concludethat

the use of personallypreferredmusicenhancedthe thera-

peuticeffects on sleepquality.

Anotherinterestingfindingwasthat participants’ageand

depressionscoreswerepositivelycorrelatedwith their sleep

quality. Despitethese two factors being correlated with

sleepquality,theydo not affect the musicintervention.Pre-

viousstudieshavefoundthatin olderpopulationsdepression

maybe relatedto insomnia.31,33Althoughthe musicusedfor

this studywasnot directedspecificallytowardsdepression,

it was able to facilitate stressreductionwhenparticipants

weretryingto sleep.Johnson17 suggestedthat patientswith

insomniamay have multiple causesincludingage, stress,

tension, and anxiety,but the mechanismsunderlyingthe

relationshipbetweenstressand sleepremainunclear.

Strengthensandlimitations

This study has two methodologicalstrengths.Firstly, the

presentstudyhadno attrition.Secondly,the presentstudy’s

researchdesigntakes the form of a RCT that providesa

strongerlevel of evidencethan other researchdesignsas

it helps reduceallocationbias.34 Despitethese strengths,

the study has several limitations. Firstly, the samples

were recruitedin one communitycentre that may induce

selectionbias. Secondly,the samplesizes may affect the

generalizabilityof the findings, althoughthe study was

appropriatelypowered to detect a mediumeffect size.

Thirdly,it wasnot possibleto blindparticipantto the exper-

imentalconditionandthereforeonemusttakeinto account

any Hawthorneeffect, which can influencethe perception

of participantsto rate their sleep quality.To explorethe

possibleplacebo-effectswithin the interventiongroup, a

futurestudycouldbe undertakento includeotherinterven-

tion groups,who listen to the natural environment,or to

other musicthat is pleasantto hear,but doesnot resemble

music with sedativecharacteristics.42 Lastly, becausethe

interventionswere conductedfor 6 weeks,other confound-

ing factors (e.g. whetherall participantsheard the same

amountof music within the intervention),that occurred

duringthe week, mayhaveaffectedparticipants’ratingsof

their sleepquality.Thesevariationsare inevitable,because

any attemptsto controltheseconfoundingvariableswould

havebeenpracticallyimpossibleandunethical.

Conclusions

The present study found evidence that music listening

helped improve sleep quality amongstolder adults. The

findingssuggestthat healthcareprofessionals,with ade-

quatetraining,couldengageelderlyclientsin the processof

musiclisteningtherapy.Not only doesthis processimprove

their sleepingqualityat old age, it also individualizesand

enhancesthe quality of care providedby the healthcare

provideras the therapeuticrelationshipbetweenprovider

andclient is beingestablished.Contemporarygerontologyis

progressivelycharacterizedby collaborationsbetweensev-

eral approacheswith the intent to comprehendboth the

mentaland physicalaspectsof the multifariousprocessof

ageing.Musiclisteningis one suchavenueto alleviatesleep

qualityamongstolder adultsand it makesan essentialcon-

tributionto healthyageing.

Contributors

MFC, AS, and JT designedthe study.AS collectedthe data.

MFCandASanalysedthe data.PreparationwasdonebyMFC,

AS, JT, and BJT.

Conflictof intereststatement

Theauthor(s)declarethat theyhaveno conflictof interests.

References

1. NomuraK, YamaokK, NakaoM, YanoE. Socialdeterminantsof

self-reportedsleepproblemsin SouthKoreaand Taiwan.Jour-

nal of PsychosomaticResearch2010;69(5):435—40.

2. RoepkeSK, Ancol-IsraelS. Sleep disordersin elderly. Indian

Journal of MedicalResearch2010;131:302—10.

3. YeungA, ChangD, GreshamJr R, NierenbergAA, FavaM. Illness

beliefsof depressedChineseAmericanpatientsin primarycare.

Journal of Nervousand Mental Disease2004;192(4):324—7.

4. ZahranHS, KobauR, MoriartyDG, Zack MM, Holt J, Donehoo

R. Health-relatedquality of life surveillance— United States,

1993—2002.Morbidity and Mortality WeeklyReport (MMWR)

SurveillanceSummaries2005;54(4):1—35.

5. BlackwellT, Yaffe K, Ancoli-IsraelS, SchneiderJL, CauleyJA,

Hillier TA, et al. Poorsleepis associatedwith impairedcognitive

function in older women:the studyof osteoporoticfractures.

Journal of Gerontology2006;61:405—10.

6. DamTL, EwingSK, Ancoli-IsraelS, EnsrudK, RedlinesSS,Stone

KL. Associationbetweensleep and physicalfunction in older

men: the osteoporoticfracturesin mansleepstudy.Journal of

AmericanGeriatric Society2008;56:1665—73.

7. Butnik SM. Neurofeedbackin adolescentsand adults with

attentiondeficit hyperactivitydisorder.Journal of Clinical Psy-

chology2005;61(5):621—5.

8. RothT, RoehrsT. Pharamcotherapyfor insomnia.SleepMedicine

Clinics 2010;5(4):529—39.

9. DeMartinisNA, Kamath J, Winokur A. New approachesfor

the treatmentof sleep disorders.Advancesin Pharmacology

2009;57:187—235.

10. BuscemiN, VandermeerB, FriesenC, BialyL, TubmanM, Ospina

M, et al. The efficacyand safetyof drugtreatmentsfor chronic

insomniain adults:a meta-analysisof RCTs.Journal of General

Internal Medicine2007;22(9):1335—50.

11. Kozasa EH, Hachul H, MonsonC, Pinto Jr L, Garcia MC, de

AraujoMoraesMLE,et al. Mind-bodyinterventionsfor the treat-

ment of insomnia:a review. Revista Brasileira de Psquiatria

2010;32(4):437—43.

12. Morin CM, Le Blanc M, Daley M, Gregoire JP, Merette C.

Epidemiologyof insomnia:prevalence,self-help treatments,

consultations, and determinatesof self-seeking behaviors.

SleepMedicine2006;7:123—30.

13. MontgomeryP, DennisJ. Brightlight therapyfor sleepproblems

in adults aged60+.CochraneDatabaseof SystematicReviews

2002;2:145—51.

14. de Niet G, TiemensB, LendemeijerB, HutschemaekersG. Music-

assistedrelaxation to improve sleep quality: meta-analysis.

Journal of AdvancedNursing2009;65(7):1356—64.

15. McCaffrey R. Music listening, its effects in creating a

healing environment. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing

2008;46(10):39—44.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

56 A. Shumet al.

16. ChanMF, Chan EA, Mok E. Effects of musicon depressionand

sleepqualityon elderly people: a randomizedcontrolledtrial.

ComplementaryTherapiesin Medicine2010;18:150—9.

17. JohnsonJE. The useof musicto promotesleepin older women.

Journal of CommunityHealth Nursing2003;20(1):27—35.

18. Lai HL, Good M. Musicimprovessleep quality in older adults.

Journal of AdvancedNursing2005;49:234—44.

19. Lazic SE, Ogilvie RD. Lack of efficacy of music to improve

sleep:a polysomnographicandquantitativeEEGanalysis.Inter-

nationalJournal of Psychophysiology2007;63:232—9.

20. ZivN, RotemT, ArnonZ, HaimovI. Theeffect of musicrelaxation

versusprogressivemuscularrelaxationon insomniain olderpeo-

ple andtheir relationshipto personalitytraits. Journal of Music

Therapy2008;45(3):360—80.

21. Harmat L, Takacs J, Bodizs R. Music improves sleep qual-

ity in students. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2008;62(3):

327—35.

22. ChangET, Lai HL, Chen PW, Hsieh YM, Lee LH. The effects of

musicon the sleepqualityof adultswith chronicinsomniausing

evidencefrom polysomnographicand self-reportedanalysis:a

randomizedcontrolled trial. InternationalJournal of Nursing

Studies2012;49:921—30.

23. DeshmukhAD, SarvaiyaAA, SeethalakshmiR, Nayak AS. The

effect of Indianclassicalmusicon qualityof sleepin depressed

patients:a randomizedcontrolledtrial. NordicJournal of Music

Therapy2009;18(1):70—8.

24. JespersenKV, VuustP. The effect of relaxationmusiclistening

on sleepqualityin traumatizedrefugees:a pilot study.Journal

of MusicTherapy2012;49(2):205—29.

25. Tan LP. The effects of backgroundmusic on quality of sleep

in elementary school children. Journal of Music Therapy

2004;41(2):128—50.

26. Daniel JB, CharlesFR, TimothyHM, SusanRB, David JK. The

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psy-

chiatric practice and research.PsychiatryResearch1989;28:

193—213.

27. Elashoff JD. nQuery Advisor 6.01. UK: Statistical Solutions;

2009.

28. YesavageJA, Brink TL, Rose TL. Developmentand validation

of a geriatricdepressionscreeningscale: a preliminaryreport.

Journal of PsychiatricResearch1982;17(1):37—99.

29. MunroBH. Statisticalmethodsfor healthcareresearch.5th ed.

USA: LippincottWilliams& Wilkins; 2005.p. 109—35[Chapter

4].

30. World Health Organization.Definition of an older or elderly

person. Heath Statistics and Health Information System;

2011.Availablefrom: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/

ageingdefnolder/en/[cited 12.08.13].

31. BonnetMH, ArandDL. Hyperarousaland insomnia:state of the

science.SleepMedicineReviews2010;14(1):9—15.

32. MornhinwegGC, VoignierRR. Musicfor sleepdisturbancein the

elderly.Journal of Holistic Nursing1995;13:248—54.

33. GuerreroJ, CrocqM. Sleepdisordersin the elderly: depression

and posttraumaticstress disorder.Journal of Psychosomatic

Research1994;38(Suppl.1):141—50.

34. Joanna BriggsInstitute.Appraiseevidence;2012.http://www.

joannabriggs.edu.au/Appraise%20Evidence[cited 21.03.2012].

35. BuysseDJ, ReynoldsCF, MonkTH, BermanSR, Kupfer DJ. The

PittsburghSleep Quality Index: new instrumentfor psychiatry

practiceand research.Sleep1989;28:193—213.

36. Lai HL. Music preferenceand relaxationin Taiwaneseelderly

people.Journal of Geriatric Nursing2004;25(5):286—91.

37. DeshmukhAD, SarvaiyaAA, Nayak AS. Effect of Indian clas-

sical music on quality of sleep in depressed patients: a

randomizedcontrolledtrial. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy

2009;18(1):70—8.

38. MurrockCJ, HigginsPA. The theoryof music,moodand move-

mentto improvehealthoutcomes.Journal of AdvancedNursing

2009;65(10):2249—57.

39. SchneckDJ, Berger DS. The music effect: music physiology

and clinical applications.London:Jessica KingsleyPublishers;

2006.

40. Bloch B, ReshefA, VadasL, Haliba Y, Ziv N, Kremer I, et al.

The effects of musicrelaxationon sleepqualityand emotional

measuresin peopleliving with schizophrenia.Journal of Music

Therapy2010;47(1):27—52.

41. GastonET. Dynamicmusicfactors in moodchange.MusicEdu-

catorsJournal 1951;37(4):42—4.

42. WampoldBE, MinamiT, TierneySC, BaskinTW, Bhati KS. The

placebo is powerful: estimatingplacebo effects in medicine

and psychotherapyfrom randomizedclinical trials. Journal of

Clinical Psychology2005;61(7):835—54.

16. ChanMF, Chan EA, Mok E. Effects of musicon depressionand

sleepqualityon elderly people: a randomizedcontrolledtrial.

ComplementaryTherapiesin Medicine2010;18:150—9.

17. JohnsonJE. The useof musicto promotesleepin older women.

Journal of CommunityHealth Nursing2003;20(1):27—35.

18. Lai HL, Good M. Musicimprovessleep quality in older adults.

Journal of AdvancedNursing2005;49:234—44.

19. Lazic SE, Ogilvie RD. Lack of efficacy of music to improve

sleep:a polysomnographicandquantitativeEEGanalysis.Inter-

nationalJournal of Psychophysiology2007;63:232—9.

20. ZivN, RotemT, ArnonZ, HaimovI. Theeffect of musicrelaxation

versusprogressivemuscularrelaxationon insomniain olderpeo-

ple andtheir relationshipto personalitytraits. Journal of Music

Therapy2008;45(3):360—80.

21. Harmat L, Takacs J, Bodizs R. Music improves sleep qual-

ity in students. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2008;62(3):

327—35.

22. ChangET, Lai HL, Chen PW, Hsieh YM, Lee LH. The effects of

musicon the sleepqualityof adultswith chronicinsomniausing

evidencefrom polysomnographicand self-reportedanalysis:a

randomizedcontrolled trial. InternationalJournal of Nursing

Studies2012;49:921—30.

23. DeshmukhAD, SarvaiyaAA, SeethalakshmiR, Nayak AS. The

effect of Indianclassicalmusicon qualityof sleepin depressed

patients:a randomizedcontrolledtrial. NordicJournal of Music

Therapy2009;18(1):70—8.

24. JespersenKV, VuustP. The effect of relaxationmusiclistening

on sleepqualityin traumatizedrefugees:a pilot study.Journal

of MusicTherapy2012;49(2):205—29.

25. Tan LP. The effects of backgroundmusic on quality of sleep

in elementary school children. Journal of Music Therapy

2004;41(2):128—50.

26. Daniel JB, CharlesFR, TimothyHM, SusanRB, David JK. The

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psy-

chiatric practice and research.PsychiatryResearch1989;28:

193—213.

27. Elashoff JD. nQuery Advisor 6.01. UK: Statistical Solutions;

2009.

28. YesavageJA, Brink TL, Rose TL. Developmentand validation

of a geriatricdepressionscreeningscale: a preliminaryreport.

Journal of PsychiatricResearch1982;17(1):37—99.

29. MunroBH. Statisticalmethodsfor healthcareresearch.5th ed.

USA: LippincottWilliams& Wilkins; 2005.p. 109—35[Chapter

4].

30. World Health Organization.Definition of an older or elderly

person. Heath Statistics and Health Information System;

2011.Availablefrom: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/

ageingdefnolder/en/[cited 12.08.13].

31. BonnetMH, ArandDL. Hyperarousaland insomnia:state of the

science.SleepMedicineReviews2010;14(1):9—15.

32. MornhinwegGC, VoignierRR. Musicfor sleepdisturbancein the

elderly.Journal of Holistic Nursing1995;13:248—54.

33. GuerreroJ, CrocqM. Sleepdisordersin the elderly: depression

and posttraumaticstress disorder.Journal of Psychosomatic

Research1994;38(Suppl.1):141—50.

34. Joanna BriggsInstitute.Appraiseevidence;2012.http://www.

joannabriggs.edu.au/Appraise%20Evidence[cited 21.03.2012].

35. BuysseDJ, ReynoldsCF, MonkTH, BermanSR, Kupfer DJ. The

PittsburghSleep Quality Index: new instrumentfor psychiatry

practiceand research.Sleep1989;28:193—213.

36. Lai HL. Music preferenceand relaxationin Taiwaneseelderly

people.Journal of Geriatric Nursing2004;25(5):286—91.

37. DeshmukhAD, SarvaiyaAA, Nayak AS. Effect of Indian clas-

sical music on quality of sleep in depressed patients: a

randomizedcontrolledtrial. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy

2009;18(1):70—8.

38. MurrockCJ, HigginsPA. The theoryof music,moodand move-

mentto improvehealthoutcomes.Journal of AdvancedNursing

2009;65(10):2249—57.

39. SchneckDJ, Berger DS. The music effect: music physiology

and clinical applications.London:Jessica KingsleyPublishers;

2006.

40. Bloch B, ReshefA, VadasL, Haliba Y, Ziv N, Kremer I, et al.

The effects of musicrelaxationon sleepqualityand emotional

measuresin peopleliving with schizophrenia.Journal of Music

Therapy2010;47(1):27—52.

41. GastonET. Dynamicmusicfactors in moodchange.MusicEdu-

catorsJournal 1951;37(4):42—4.

42. WampoldBE, MinamiT, TierneySC, BaskinTW, Bhati KS. The

placebo is powerful: estimatingplacebo effects in medicine

and psychotherapyfrom randomizedclinical trials. Journal of

Clinical Psychology2005;61(7):835—54.

1 out of 8

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.