Comparing National Health Workforce Plans: Australia and Japan

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/10

|17

|3917

|312

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comparative analysis of the health workforce plans of Australia and Japan, examining their approaches to meet current and future healthcare needs. The report begins with an executive summary and table of contents, followed by an introduction highlighting the importance of health workforce planning. It then presents environmental scans of both Australia and Japan, detailing their healthcare systems, populations, and economic contexts. Data profiles are compared, including workforce statistics on doctors, nurses, and other medical practitioners, and critical issues such as aging workforce, gender imbalances and inadequate domestic practitioners are discussed. The report evaluates each country's plans in relation to WHO health workforce priorities, concluding that Japan's plan is effective due to its ability to produce skilled practitioners. The report suggests that Australia needs to implement WHO recommendations to ensure an accessible and skilled workforce. The report uses WHO reports, government websites and scholarly literature. The report concludes that the Japanese health workforce plan effective because of its ability to produce adequate skilled practitioners that meet the country demand for health care services. Australia will require implementing all WHO recommendations on health workforce to foster adequate, accessible, and highly skilled health workforce that is responsive to meet expected health needs of Australians.

UNIT:

NAME:

DATE:

NAME:

DATE:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Executive Summary

Lack of an appropriate health workforce plan can threaten a health system ability to deliver

health care to it population. Health human resource plan provide strategic framework for the

future by ensuring a health system prepares medical practitioners to meet expected population

health demands (Rees, Crampton, Gauld, & MacDonell, 2018). The following report analyses

Australian and Japanese health workforce plans to find out if they have prioritized WHO health

workforce priorities. The report uses WHO reports, available information from government

websites and scholarly literature. The report found out that the countries haven’t fully

implemented WHO health workforce priorities. The report also found that the Japanese health

workforce is well organized and delivers quality, accessible and affordable health care even

without the need of implementing the WHO health workforce recommendations. The reports

therefore concludes that the Japanese health workforce plan effective because of its ability to

produce adequate skilled practitioners that meet the country demand for health care services.

Australia will require implementing all WHO recommendations on health workforce to foster

adequate, accessible, and highly skilled health workforce that is responsive to meet expected

health needs of Australians.

Lack of an appropriate health workforce plan can threaten a health system ability to deliver

health care to it population. Health human resource plan provide strategic framework for the

future by ensuring a health system prepares medical practitioners to meet expected population

health demands (Rees, Crampton, Gauld, & MacDonell, 2018). The following report analyses

Australian and Japanese health workforce plans to find out if they have prioritized WHO health

workforce priorities. The report uses WHO reports, available information from government

websites and scholarly literature. The report found out that the countries haven’t fully

implemented WHO health workforce priorities. The report also found that the Japanese health

workforce is well organized and delivers quality, accessible and affordable health care even

without the need of implementing the WHO health workforce recommendations. The reports

therefore concludes that the Japanese health workforce plan effective because of its ability to

produce adequate skilled practitioners that meet the country demand for health care services.

Australia will require implementing all WHO recommendations on health workforce to foster

adequate, accessible, and highly skilled health workforce that is responsive to meet expected

health needs of Australians.

Table of Contents

Introduction.................................................................................................................................................4

Environmental Scan.....................................................................................................................................5

Australia..................................................................................................................................................5

Japan.......................................................................................................................................................6

Data Profile..................................................................................................................................................7

Summary Data Profile Table 2015...........................................................................................................7

Current Supply.........................................................................................................................................8

Age and Gender.....................................................................................................................................10

Critical Issues.............................................................................................................................................11

Australia................................................................................................................................................11

Japan.....................................................................................................................................................12

Evaluation of Australia and Japan..............................................................................................................13

Conclusion.................................................................................................................................................15

References.................................................................................................................................................16

Introduction.................................................................................................................................................4

Environmental Scan.....................................................................................................................................5

Australia..................................................................................................................................................5

Japan.......................................................................................................................................................6

Data Profile..................................................................................................................................................7

Summary Data Profile Table 2015...........................................................................................................7

Current Supply.........................................................................................................................................8

Age and Gender.....................................................................................................................................10

Critical Issues.............................................................................................................................................11

Australia................................................................................................................................................11

Japan.....................................................................................................................................................12

Evaluation of Australia and Japan..............................................................................................................13

Conclusion.................................................................................................................................................15

References.................................................................................................................................................16

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

National Health Workforce Plan

Comparison Australia Vs Japan

Introduction

A health workforce plan is an important aspect to meeting a country’s current and future health

care needs. Human resource is an integral part of any health system and requires appropriate

planning from several stakeholders to optimally deliver quality and accessible health care

(Crettenden et al., 2014). World Health Organization (WHO) defines health workforce as all

individual whose work is for protecting and improving health of the communities. They include

practitioners in clinical and non clinical field who administer public and individual health

interventions. An effective national health workforce plan aim to ensuring all citizens in all

locations have access of skilled health practitioner, who is well equipped, supported and

motivated (Craveiro et al., 2018). A national health plan targets to achieve national health goals,

obligations, and commitment of its citizens. According to WHO, a health workforce plan has to

be comprehensive and address health workforce finances, policies of practice, partnership for

optimal health care, leadership in health sector, and health resource management systems. Lack

of an explicit health human resource planning threatens a country’s healthcare systems capacity

to attain its objectives. A national health workforce plan should therefore focus on developing a

healthcare system that is responsive to a population needs and expectations. The following report

compares Australian and Japan national health workforce plan. Japan healthcare is good a

comparison to Australian healthcare because of a developed country similar to Australia and has

the highest outcome in terms of life expectancy in the whole world. This will show the difference

in health workforce planning or planning process that causes the difference. This will involve

environmental scanning, preparation of workforce profiles and discussion of critical issues to

addressed in the countries health workforce plan. The report will also evaluate each country’s

national workforce plans to find out if they are addressing WHO priorities in health workforce.

Environmental Scan

This section analyses the Australian and Singaporean health workforce using national and

international health workforce plans and included polices and plans for health workforce. This

Comparison Australia Vs Japan

Introduction

A health workforce plan is an important aspect to meeting a country’s current and future health

care needs. Human resource is an integral part of any health system and requires appropriate

planning from several stakeholders to optimally deliver quality and accessible health care

(Crettenden et al., 2014). World Health Organization (WHO) defines health workforce as all

individual whose work is for protecting and improving health of the communities. They include

practitioners in clinical and non clinical field who administer public and individual health

interventions. An effective national health workforce plan aim to ensuring all citizens in all

locations have access of skilled health practitioner, who is well equipped, supported and

motivated (Craveiro et al., 2018). A national health plan targets to achieve national health goals,

obligations, and commitment of its citizens. According to WHO, a health workforce plan has to

be comprehensive and address health workforce finances, policies of practice, partnership for

optimal health care, leadership in health sector, and health resource management systems. Lack

of an explicit health human resource planning threatens a country’s healthcare systems capacity

to attain its objectives. A national health workforce plan should therefore focus on developing a

healthcare system that is responsive to a population needs and expectations. The following report

compares Australian and Japan national health workforce plan. Japan healthcare is good a

comparison to Australian healthcare because of a developed country similar to Australia and has

the highest outcome in terms of life expectancy in the whole world. This will show the difference

in health workforce planning or planning process that causes the difference. This will involve

environmental scanning, preparation of workforce profiles and discussion of critical issues to

addressed in the countries health workforce plan. The report will also evaluate each country’s

national workforce plans to find out if they are addressing WHO priorities in health workforce.

Environmental Scan

This section analyses the Australian and Singaporean health workforce using national and

international health workforce plans and included polices and plans for health workforce. This

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

will enable understanding of the factors shaping each country’s health workforce plan and

planning processes.

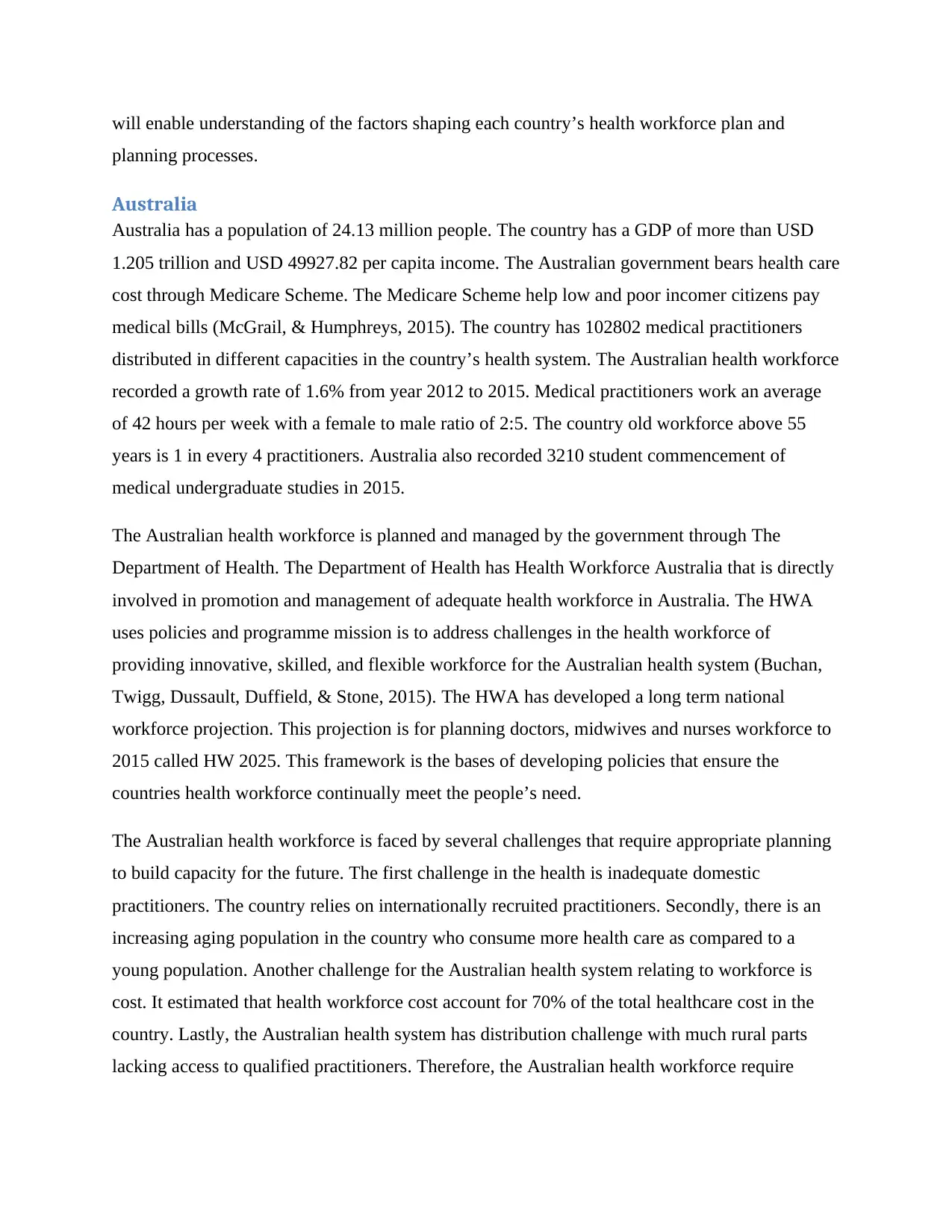

Australia

Australia has a population of 24.13 million people. The country has a GDP of more than USD

1.205 trillion and USD 49927.82 per capita income. The Australian government bears health care

cost through Medicare Scheme. The Medicare Scheme help low and poor incomer citizens pay

medical bills (McGrail, & Humphreys, 2015). The country has 102802 medical practitioners

distributed in different capacities in the country’s health system. The Australian health workforce

recorded a growth rate of 1.6% from year 2012 to 2015. Medical practitioners work an average

of 42 hours per week with a female to male ratio of 2:5. The country old workforce above 55

years is 1 in every 4 practitioners. Australia also recorded 3210 student commencement of

medical undergraduate studies in 2015.

The Australian health workforce is planned and managed by the government through The

Department of Health. The Department of Health has Health Workforce Australia that is directly

involved in promotion and management of adequate health workforce in Australia. The HWA

uses policies and programme mission is to address challenges in the health workforce of

providing innovative, skilled, and flexible workforce for the Australian health system (Buchan,

Twigg, Dussault, Duffield, & Stone, 2015). The HWA has developed a long term national

workforce projection. This projection is for planning doctors, midwives and nurses workforce to

2015 called HW 2025. This framework is the bases of developing policies that ensure the

countries health workforce continually meet the people’s need.

The Australian health workforce is faced by several challenges that require appropriate planning

to build capacity for the future. The first challenge in the health is inadequate domestic

practitioners. The country relies on internationally recruited practitioners. Secondly, there is an

increasing aging population in the country who consume more health care as compared to a

young population. Another challenge for the Australian health system relating to workforce is

cost. It estimated that health workforce cost account for 70% of the total healthcare cost in the

country. Lastly, the Australian health system has distribution challenge with much rural parts

lacking access to qualified practitioners. Therefore, the Australian health workforce require

planning processes.

Australia

Australia has a population of 24.13 million people. The country has a GDP of more than USD

1.205 trillion and USD 49927.82 per capita income. The Australian government bears health care

cost through Medicare Scheme. The Medicare Scheme help low and poor incomer citizens pay

medical bills (McGrail, & Humphreys, 2015). The country has 102802 medical practitioners

distributed in different capacities in the country’s health system. The Australian health workforce

recorded a growth rate of 1.6% from year 2012 to 2015. Medical practitioners work an average

of 42 hours per week with a female to male ratio of 2:5. The country old workforce above 55

years is 1 in every 4 practitioners. Australia also recorded 3210 student commencement of

medical undergraduate studies in 2015.

The Australian health workforce is planned and managed by the government through The

Department of Health. The Department of Health has Health Workforce Australia that is directly

involved in promotion and management of adequate health workforce in Australia. The HWA

uses policies and programme mission is to address challenges in the health workforce of

providing innovative, skilled, and flexible workforce for the Australian health system (Buchan,

Twigg, Dussault, Duffield, & Stone, 2015). The HWA has developed a long term national

workforce projection. This projection is for planning doctors, midwives and nurses workforce to

2015 called HW 2025. This framework is the bases of developing policies that ensure the

countries health workforce continually meet the people’s need.

The Australian health workforce is faced by several challenges that require appropriate planning

to build capacity for the future. The first challenge in the health is inadequate domestic

practitioners. The country relies on internationally recruited practitioners. Secondly, there is an

increasing aging population in the country who consume more health care as compared to a

young population. Another challenge for the Australian health system relating to workforce is

cost. It estimated that health workforce cost account for 70% of the total healthcare cost in the

country. Lastly, the Australian health system has distribution challenge with much rural parts

lacking access to qualified practitioners. Therefore, the Australian health workforce require

appropriate planning to meet it people’s health care need by addressing the current issues and

preparing for the future challenges.

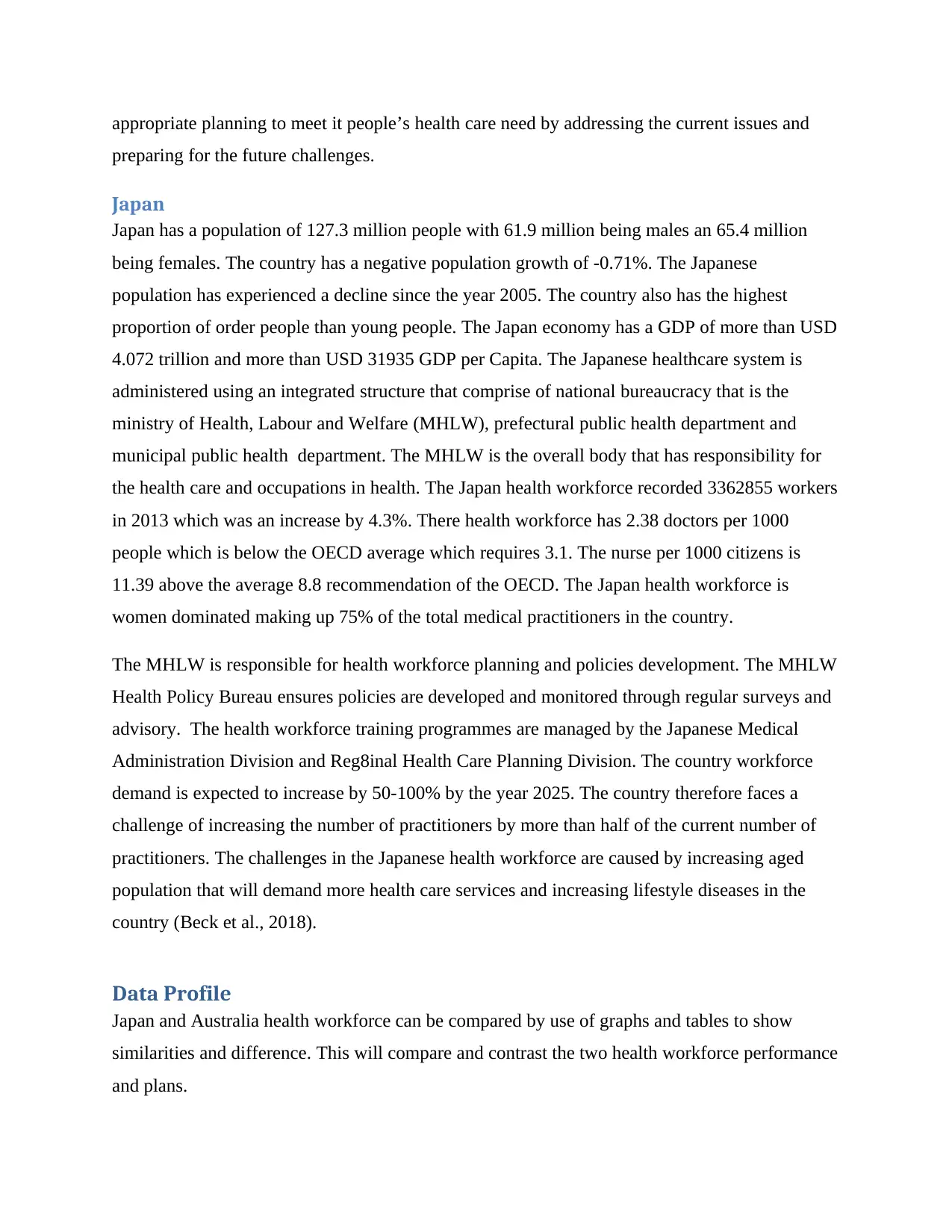

Japan

Japan has a population of 127.3 million people with 61.9 million being males an 65.4 million

being females. The country has a negative population growth of -0.71%. The Japanese

population has experienced a decline since the year 2005. The country also has the highest

proportion of order people than young people. The Japan economy has a GDP of more than USD

4.072 trillion and more than USD 31935 GDP per Capita. The Japanese healthcare system is

administered using an integrated structure that comprise of national bureaucracy that is the

ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), prefectural public health department and

municipal public health department. The MHLW is the overall body that has responsibility for

the health care and occupations in health. The Japan health workforce recorded 3362855 workers

in 2013 which was an increase by 4.3%. There health workforce has 2.38 doctors per 1000

people which is below the OECD average which requires 3.1. The nurse per 1000 citizens is

11.39 above the average 8.8 recommendation of the OECD. The Japan health workforce is

women dominated making up 75% of the total medical practitioners in the country.

The MHLW is responsible for health workforce planning and policies development. The MHLW

Health Policy Bureau ensures policies are developed and monitored through regular surveys and

advisory. The health workforce training programmes are managed by the Japanese Medical

Administration Division and Reg8inal Health Care Planning Division. The country workforce

demand is expected to increase by 50-100% by the year 2025. The country therefore faces a

challenge of increasing the number of practitioners by more than half of the current number of

practitioners. The challenges in the Japanese health workforce are caused by increasing aged

population that will demand more health care services and increasing lifestyle diseases in the

country (Beck et al., 2018).

Data Profile

Japan and Australia health workforce can be compared by use of graphs and tables to show

similarities and difference. This will compare and contrast the two health workforce performance

and plans.

preparing for the future challenges.

Japan

Japan has a population of 127.3 million people with 61.9 million being males an 65.4 million

being females. The country has a negative population growth of -0.71%. The Japanese

population has experienced a decline since the year 2005. The country also has the highest

proportion of order people than young people. The Japan economy has a GDP of more than USD

4.072 trillion and more than USD 31935 GDP per Capita. The Japanese healthcare system is

administered using an integrated structure that comprise of national bureaucracy that is the

ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), prefectural public health department and

municipal public health department. The MHLW is the overall body that has responsibility for

the health care and occupations in health. The Japan health workforce recorded 3362855 workers

in 2013 which was an increase by 4.3%. There health workforce has 2.38 doctors per 1000

people which is below the OECD average which requires 3.1. The nurse per 1000 citizens is

11.39 above the average 8.8 recommendation of the OECD. The Japan health workforce is

women dominated making up 75% of the total medical practitioners in the country.

The MHLW is responsible for health workforce planning and policies development. The MHLW

Health Policy Bureau ensures policies are developed and monitored through regular surveys and

advisory. The health workforce training programmes are managed by the Japanese Medical

Administration Division and Reg8inal Health Care Planning Division. The country workforce

demand is expected to increase by 50-100% by the year 2025. The country therefore faces a

challenge of increasing the number of practitioners by more than half of the current number of

practitioners. The challenges in the Japanese health workforce are caused by increasing aged

population that will demand more health care services and increasing lifestyle diseases in the

country (Beck et al., 2018).

Data Profile

Japan and Australia health workforce can be compared by use of graphs and tables to show

similarities and difference. This will compare and contrast the two health workforce performance

and plans.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

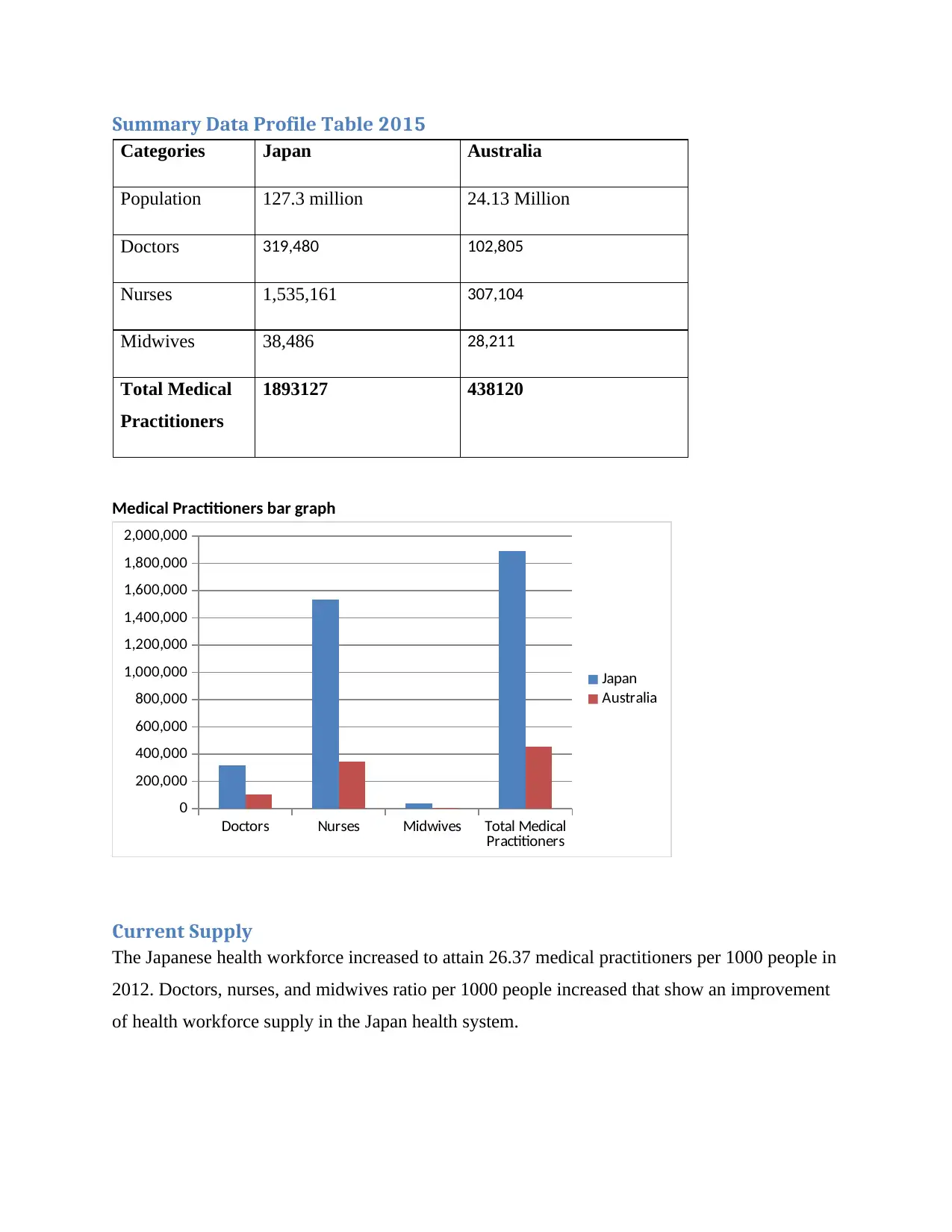

Summary Data Profile Table 2015

Categories Japan Australia

Population 127.3 million 24.13 Million

Doctors 319,480 102,805

Nurses 1,535,161 307,104

Midwives 38,486 28,211

Total Medical

Practitioners

1893127 438120

Medical Practitioners bar graph

Doctors Nurses Midwives Total Medical

Practitioners

0

200,000

400,000

600,000

800,000

1,000,000

1,200,000

1,400,000

1,600,000

1,800,000

2,000,000

Japan

Australia

Current Supply

The Japanese health workforce increased to attain 26.37 medical practitioners per 1000 people in

2012. Doctors, nurses, and midwives ratio per 1000 people increased that show an improvement

of health workforce supply in the Japan health system.

Categories Japan Australia

Population 127.3 million 24.13 Million

Doctors 319,480 102,805

Nurses 1,535,161 307,104

Midwives 38,486 28,211

Total Medical

Practitioners

1893127 438120

Medical Practitioners bar graph

Doctors Nurses Midwives Total Medical

Practitioners

0

200,000

400,000

600,000

800,000

1,000,000

1,200,000

1,400,000

1,600,000

1,800,000

2,000,000

Japan

Australia

Current Supply

The Japanese health workforce increased to attain 26.37 medical practitioners per 1000 people in

2012. Doctors, nurses, and midwives ratio per 1000 people increased that show an improvement

of health workforce supply in the Japan health system.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Australia health workforce improved from 2012 to attain 375 medical practitioners per 1000

people in 2015. This represented a 1.8% annual growth of health workforce.

people in 2015. This represented a 1.8% annual growth of health workforce.

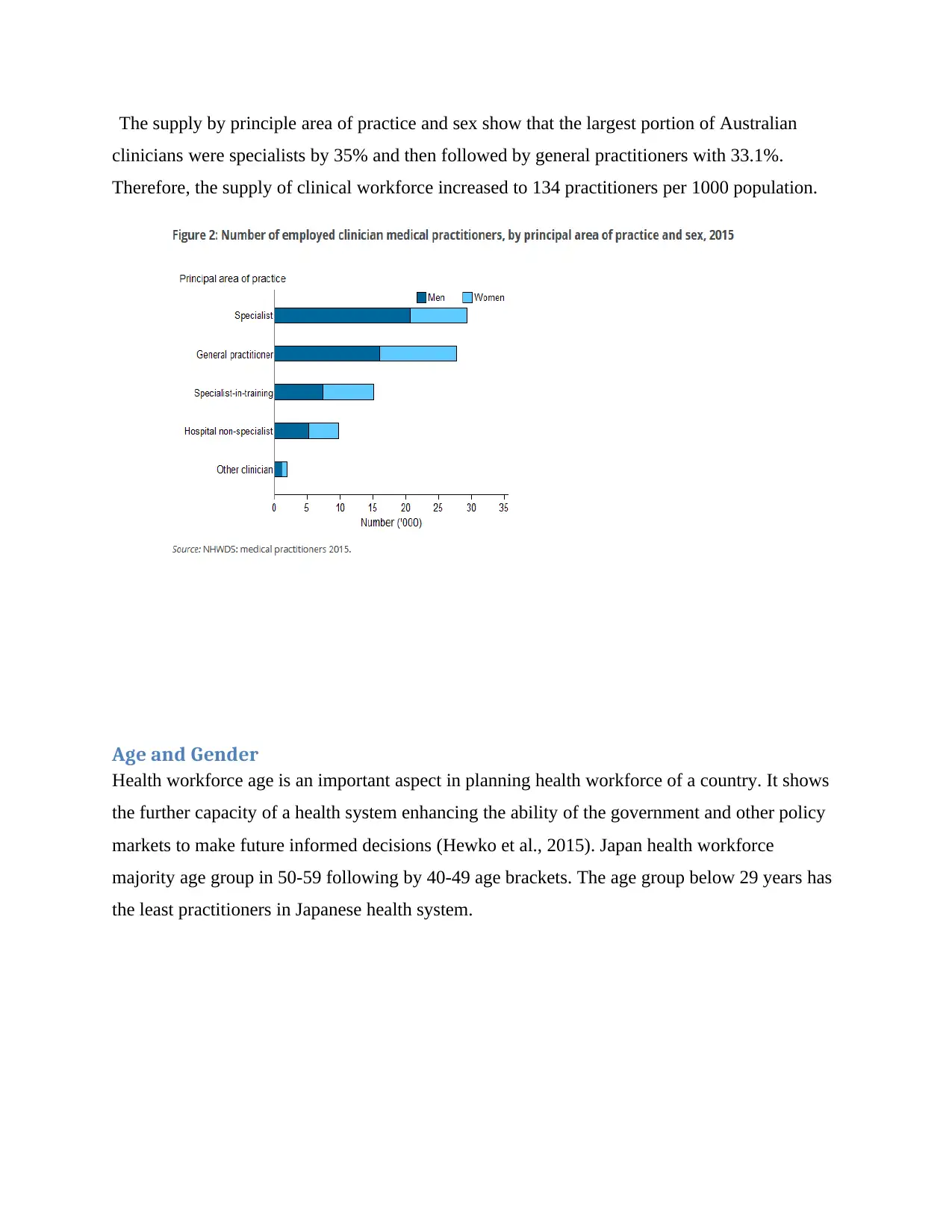

The supply by principle area of practice and sex show that the largest portion of Australian

clinicians were specialists by 35% and then followed by general practitioners with 33.1%.

Therefore, the supply of clinical workforce increased to 134 practitioners per 1000 population.

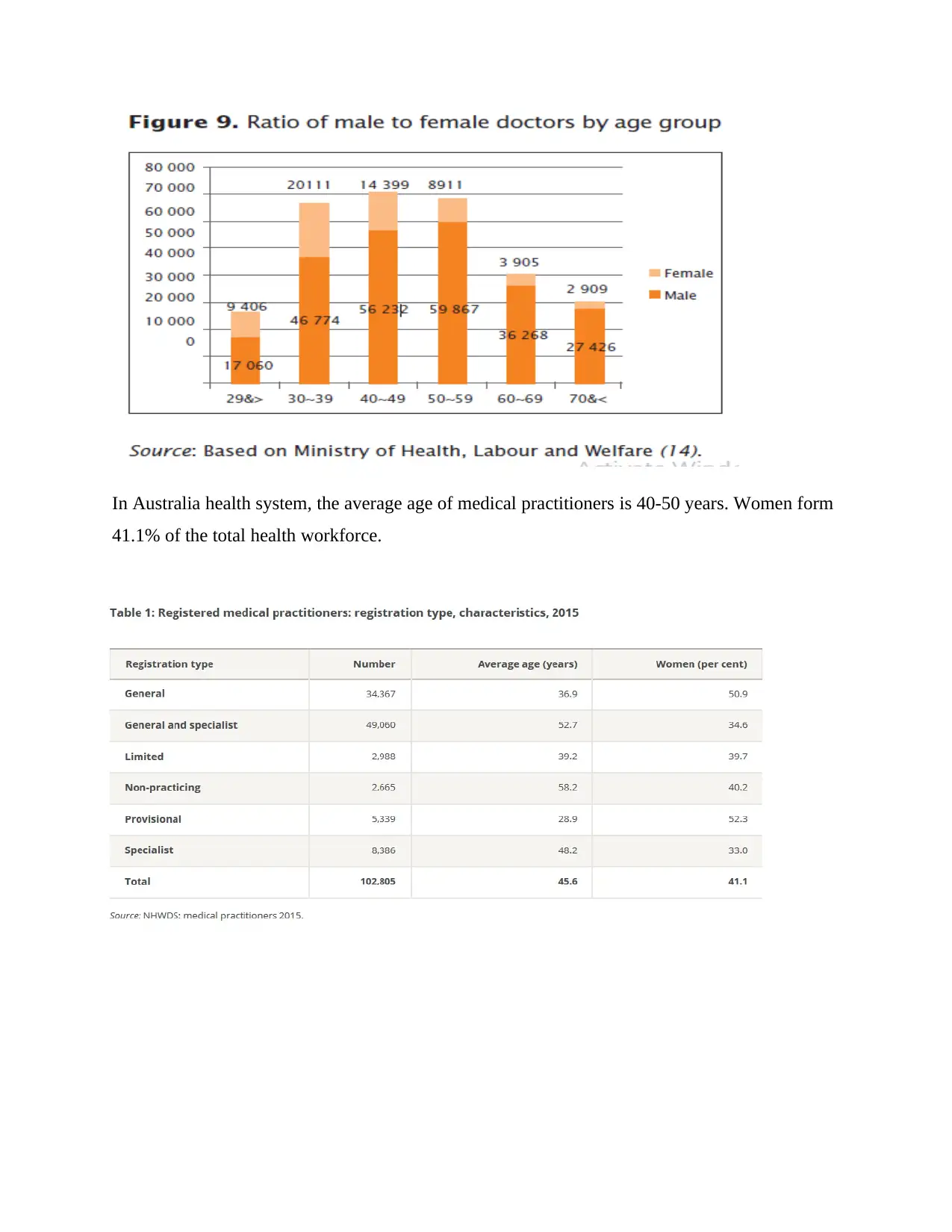

Age and Gender

Health workforce age is an important aspect in planning health workforce of a country. It shows

the further capacity of a health system enhancing the ability of the government and other policy

markets to make future informed decisions (Hewko et al., 2015). Japan health workforce

majority age group in 50-59 following by 40-49 age brackets. The age group below 29 years has

the least practitioners in Japanese health system.

clinicians were specialists by 35% and then followed by general practitioners with 33.1%.

Therefore, the supply of clinical workforce increased to 134 practitioners per 1000 population.

Age and Gender

Health workforce age is an important aspect in planning health workforce of a country. It shows

the further capacity of a health system enhancing the ability of the government and other policy

markets to make future informed decisions (Hewko et al., 2015). Japan health workforce

majority age group in 50-59 following by 40-49 age brackets. The age group below 29 years has

the least practitioners in Japanese health system.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

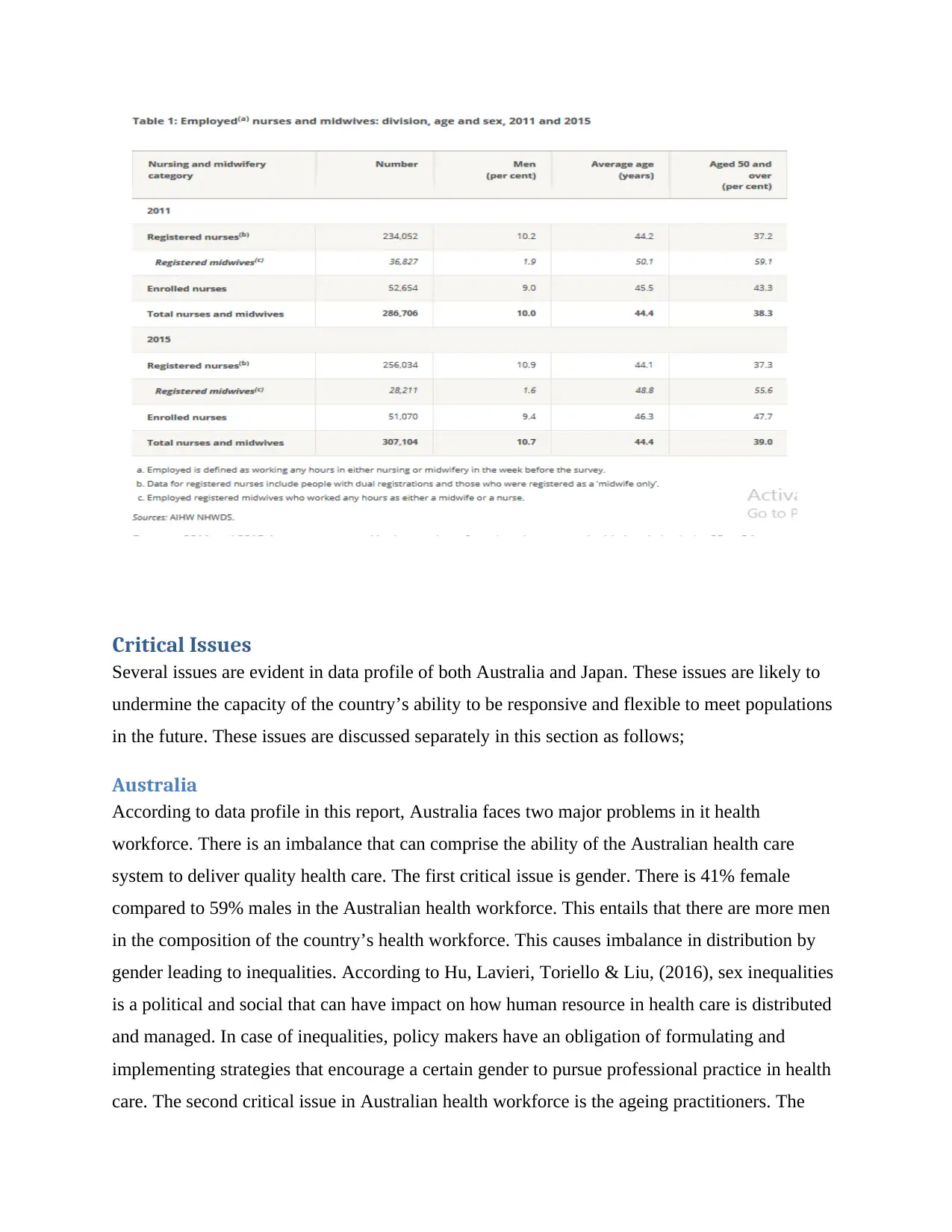

In Australia health system, the average age of medical practitioners is 40-50 years. Women form

41.1% of the total health workforce.

41.1% of the total health workforce.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Critical Issues

Several issues are evident in data profile of both Australia and Japan. These issues are likely to

undermine the capacity of the country’s ability to be responsive and flexible to meet populations

in the future. These issues are discussed separately in this section as follows;

Australia

According to data profile in this report, Australia faces two major problems in it health

workforce. There is an imbalance that can comprise the ability of the Australian health care

system to deliver quality health care. The first critical issue is gender. There is 41% female

compared to 59% males in the Australian health workforce. This entails that there are more men

in the composition of the country’s health workforce. This causes imbalance in distribution by

gender leading to inequalities. According to Hu, Lavieri, Toriello & Liu, (2016), sex inequalities

is a political and social that can have impact on how human resource in health care is distributed

and managed. In case of inequalities, policy makers have an obligation of formulating and

implementing strategies that encourage a certain gender to pursue professional practice in health

care. The second critical issue in Australian health workforce is the ageing practitioners. The

Several issues are evident in data profile of both Australia and Japan. These issues are likely to

undermine the capacity of the country’s ability to be responsive and flexible to meet populations

in the future. These issues are discussed separately in this section as follows;

Australia

According to data profile in this report, Australia faces two major problems in it health

workforce. There is an imbalance that can comprise the ability of the Australian health care

system to deliver quality health care. The first critical issue is gender. There is 41% female

compared to 59% males in the Australian health workforce. This entails that there are more men

in the composition of the country’s health workforce. This causes imbalance in distribution by

gender leading to inequalities. According to Hu, Lavieri, Toriello & Liu, (2016), sex inequalities

is a political and social that can have impact on how human resource in health care is distributed

and managed. In case of inequalities, policy makers have an obligation of formulating and

implementing strategies that encourage a certain gender to pursue professional practice in health

care. The second critical issue in Australian health workforce is the ageing practitioners. The

average age of medical practitioners is 45 years old. This entails that by the year 2025 most of

the practitioners in the practice be retiring or preparing to retire from the health system.

Lafortune, (2014) stated that age is an important factor to planning future availability and

capacity of a health system. A young aged health workforce indicate a growing capacity that will

meet the population health care need in the future while an old aged medical practitioners in an

indication of a health system that will not be responsive to future needs of a population.

Therefore, an aging health workforce is threat to a health system ability to deliver accessible

health care to citizens of a country. Australia therefore has to handle aging and gender issues in

the health workforce to avoid the issues undermining the capacity of projected increased demand

for health services in the future.

Japan

The Japanese health workforce is faced with several issues that if not addressed in the health

workforce plan can undermine the ability of the country health system to deliver quality and

accessible health care to its citizens. The first critical issue in the Japan health workforce is the

aging human resource. The majority of medicine practitioners are between 50 to 59 years of age.

This age group of highly qualified workforce will not be available in the future and therefore the

MHLW require appropriate planning to successful develop by training new practitioners. The

Japanese health workforce has a very low health workforce of 29 years and below. This is an

indicator that there are many practitioners who are likely to vacant the health system while at the

same time there is low recruitment level of new practitioners. According to Balasubramanian et

al., (2015) health workforce planners should periodically monitor the age of practitioners to plan

for succession of employees in the health system without leaving a gap at any particular time.

The second critical issue in Japan health workforce is motivation to work in the health care

sector. The Japan has a high level of people who does not contribute to the country’s workforce.

Some practitioners were leaving the health system with an objective to returning in the future.

Lopes, Almeida, & Almada-Lobo, (2015) states that motivation is an important part of a health

workforce plan that enable professional practitioners to have willingness to participate in a health

system. A health workforce plan has to attract, recruit, and retain medical practitioners to

enhance efficiency of human resource performance in the health care (Naccarella, Wraight, &

Gorman, 2016). Therefore, the Japan health workforce plan needs to consider aging practitioners

the practitioners in the practice be retiring or preparing to retire from the health system.

Lafortune, (2014) stated that age is an important factor to planning future availability and

capacity of a health system. A young aged health workforce indicate a growing capacity that will

meet the population health care need in the future while an old aged medical practitioners in an

indication of a health system that will not be responsive to future needs of a population.

Therefore, an aging health workforce is threat to a health system ability to deliver accessible

health care to citizens of a country. Australia therefore has to handle aging and gender issues in

the health workforce to avoid the issues undermining the capacity of projected increased demand

for health services in the future.

Japan

The Japanese health workforce is faced with several issues that if not addressed in the health

workforce plan can undermine the ability of the country health system to deliver quality and

accessible health care to its citizens. The first critical issue in the Japan health workforce is the

aging human resource. The majority of medicine practitioners are between 50 to 59 years of age.

This age group of highly qualified workforce will not be available in the future and therefore the

MHLW require appropriate planning to successful develop by training new practitioners. The

Japanese health workforce has a very low health workforce of 29 years and below. This is an

indicator that there are many practitioners who are likely to vacant the health system while at the

same time there is low recruitment level of new practitioners. According to Balasubramanian et

al., (2015) health workforce planners should periodically monitor the age of practitioners to plan

for succession of employees in the health system without leaving a gap at any particular time.

The second critical issue in Japan health workforce is motivation to work in the health care

sector. The Japan has a high level of people who does not contribute to the country’s workforce.

Some practitioners were leaving the health system with an objective to returning in the future.

Lopes, Almeida, & Almada-Lobo, (2015) states that motivation is an important part of a health

workforce plan that enable professional practitioners to have willingness to participate in a health

system. A health workforce plan has to attract, recruit, and retain medical practitioners to

enhance efficiency of human resource performance in the health care (Naccarella, Wraight, &

Gorman, 2016). Therefore, the Japan health workforce plan needs to consider aging practitioners

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 17

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.