Analysis of National Safety and Quality Health Service Standard 3

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/10

|11

|2484

|481

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a critical review of the National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS) Standard 3, which focuses on preventing and controlling healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). The report examines the importance of evidence-based practices, such as hand hygiene and infection control systems, in healthcare settings to improve patient safety and quality of life. It discusses the role of the Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infections in Healthcare, the Australian Capital Territory Government, and the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (ACHS) in ensuring compliance with the standard. The report also highlights the challenges in HAI surveillance, the need for improved data collection, and the importance of accountability in healthcare environments. The report concludes by emphasizing the significance of HAI surveillance programs and the need for national initiatives to improve data reliability and the validation of infection prevention methods. The report also references the accreditation process and the challenges faced by Canberra Hospital in meeting the standards.

Running head: NATIONAL SAFETY AND QUALITY HEALTH SERVICE STANDARD 3 1

A Critical Review of National Safety and Quality Health Service Standard 3

Student’s Name

University

A Critical Review of National Safety and Quality Health Service Standard 3

Student’s Name

University

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

NATIONAL SAFETY AND QUALITY HEALTH SERVICE STANDARD 3 2

A Critical Review of National Safety and Quality Health Service Standard 3

The rise of evidence-based approaches has changed the clinical environment requiring

professionals to follow a certain set of standards in dealing with clinical issues. When standards

are set within a certain industry, then it means that related organizations have to observe

uniformity by all means. In scientific approaches and use of standards, it is important to have a

clear guideline that defines the level of engagement that organizations follow when handling

patient-related issues. Uniformity of care in healthcare institutions can only be achieved if there

is a set of standards that are set to control and manage the healthcare environment by setting a

benchmark that can be used to assess and measure the performance standards of the institution

(Black, Balneaves, Garossino, Puyat, & Qian, 2015). Standards provide levels that customers

expect from healthcare organizations. The outcome of the standards is to provide patient safety

and improve the quality of life in different areas. Healthcare organizations have to be assessed to

determine if they meet the criteria set out as a way of protecting the public from harm. This

means that standards exist to set consistent levels that organizations work along to ensure

consistency and uniformity in healthcare. The National Safety and Quality Health Service

(NSQHS) Standards are used by healthcare organizations to assess their performance by

benchmarking themselves against the standards (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality

in Health Care, 2017). This means that the criteria set are the minimum standard that needs to be

followed by healthcare institutions. This will be reflected in the consistency that will be achieved

when healthcare institutions work with a standard framework that sets a benchmark on what

needs to be done and how it can be achieved. The outcome is public protection from harm and

improved quality of health services.

Standard 3: preventing and controlling healthcare-associated infection

A Critical Review of National Safety and Quality Health Service Standard 3

The rise of evidence-based approaches has changed the clinical environment requiring

professionals to follow a certain set of standards in dealing with clinical issues. When standards

are set within a certain industry, then it means that related organizations have to observe

uniformity by all means. In scientific approaches and use of standards, it is important to have a

clear guideline that defines the level of engagement that organizations follow when handling

patient-related issues. Uniformity of care in healthcare institutions can only be achieved if there

is a set of standards that are set to control and manage the healthcare environment by setting a

benchmark that can be used to assess and measure the performance standards of the institution

(Black, Balneaves, Garossino, Puyat, & Qian, 2015). Standards provide levels that customers

expect from healthcare organizations. The outcome of the standards is to provide patient safety

and improve the quality of life in different areas. Healthcare organizations have to be assessed to

determine if they meet the criteria set out as a way of protecting the public from harm. This

means that standards exist to set consistent levels that organizations work along to ensure

consistency and uniformity in healthcare. The National Safety and Quality Health Service

(NSQHS) Standards are used by healthcare organizations to assess their performance by

benchmarking themselves against the standards (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality

in Health Care, 2017). This means that the criteria set are the minimum standard that needs to be

followed by healthcare institutions. This will be reflected in the consistency that will be achieved

when healthcare institutions work with a standard framework that sets a benchmark on what

needs to be done and how it can be achieved. The outcome is public protection from harm and

improved quality of health services.

Standard 3: preventing and controlling healthcare-associated infection

NATIONAL SAFETY AND QUALITY HEALTH SERVICE STANDARD 3 3

The NSQHS third standard of preventing and controlling healthcare-associated infection

applies to the management and control of healthcare-associated infections to increase patient

quality of life and prevent harm. Through infection prevention and control systems, healthcare

organizations are supposed to use evidence-based systems to prevent and control health-related

associations. To achieve this standard, hospital settings must have measures in place for

identifying patients presented to the facility with risk factors for infection of different diseases or

organisms to be identified immediately so that they can receive management and treatment of the

conditions that they have. The Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infections

in Healthcare has set guidelines that define evidence-based systems that hospitals are supposed

to comply with. These are hand hygiene, standard and transmission-based precautions, invasive

medical devices, workforce immunization and clean environment, aseptic technique, and

invasive services. This is because different initiatives are used to define how health initiatives

need to be done. For example, hand hygiene needs to be consistent with the National Hand

Hygiene Initiative that is based on the WHO patient safety campaigns that define the way hand

hygiene needs to be carried out.

In the Australian Capital Territory Government, infection and prevention control units

are established in hospitals to minimize the risk of infection for patients, health care providers,

and medical students. This infection control program has several strategies that are used to

ensure that there is compliance with different requirements for hospitals (ACT Government,

2019). This is seen in Canberra Hospital which has established the unit as per the ACT

government requirements. In Infection prevention and control systems, the hospital applies

several strategies to achieve its objective. The first infection prevention strategy is to ensure

compliance with sterilization standards and guidelines like the AS4187 and GENCA which are

The NSQHS third standard of preventing and controlling healthcare-associated infection

applies to the management and control of healthcare-associated infections to increase patient

quality of life and prevent harm. Through infection prevention and control systems, healthcare

organizations are supposed to use evidence-based systems to prevent and control health-related

associations. To achieve this standard, hospital settings must have measures in place for

identifying patients presented to the facility with risk factors for infection of different diseases or

organisms to be identified immediately so that they can receive management and treatment of the

conditions that they have. The Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infections

in Healthcare has set guidelines that define evidence-based systems that hospitals are supposed

to comply with. These are hand hygiene, standard and transmission-based precautions, invasive

medical devices, workforce immunization and clean environment, aseptic technique, and

invasive services. This is because different initiatives are used to define how health initiatives

need to be done. For example, hand hygiene needs to be consistent with the National Hand

Hygiene Initiative that is based on the WHO patient safety campaigns that define the way hand

hygiene needs to be carried out.

In the Australian Capital Territory Government, infection and prevention control units

are established in hospitals to minimize the risk of infection for patients, health care providers,

and medical students. This infection control program has several strategies that are used to

ensure that there is compliance with different requirements for hospitals (ACT Government,

2019). This is seen in Canberra Hospital which has established the unit as per the ACT

government requirements. In Infection prevention and control systems, the hospital applies

several strategies to achieve its objective. The first infection prevention strategy is to ensure

compliance with sterilization standards and guidelines like the AS4187 and GENCA which are

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

NATIONAL SAFETY AND QUALITY HEALTH SERVICE STANDARD 3 4

used to prevent clinical infections and at the same time monitoring bloodstream and surgical site

infections (Russo, et al., 2018). Apart from that, the unit is in charge of implementation and

monitoring of hygiene, reducing the emergence of antibiotic-resistant organisms and at the same

time ensuring that infection control guidelines are adhered to within clinical settings. Further, the

unit is supposed to ensure that buildings are renovated and projects designed according to the

required clinical standards like managing the supply of medical equipment to ensure that they

meet the standards established under different medical and clinical standards.

According to the Bedoya, et al. (2017), infection prevention and control practices are a

characteristic of the whole healthcare system and not just an individual healthcare provider. This

implies that the prevention and control of infections are critical in the well-functioning of a

healthcare system. The WHO estimates that around 165,000 Australians contract hospital-related

infections every year which can be prevented (Mitchell, 2017). This challenge has been

attributed to the lack of health-associated infection surveillance which can capture the changes in

the country. This burden is not all about infection but rather some patients die due to these

infections while others are forced to stay longer in hospitals for treatment. In a review

by Mitchell, Shaban, MacBeth, Wood, & Russo (2017) reported that there is limited data on

common infection in Australia due to lack of health surveillance system that can capture and

report.

Stone (2019) adds that having reliable estimate data on health associated infections forms

the basis of prioritization of the prevention and control strategies while at the same time

providing a benchmark for the future. This shows that the existing strategies are limited in the

prevention of infections which call for the need to address the gaps by bringing together different

government bodies which can be important in achieving consensus on prevention approaches and

used to prevent clinical infections and at the same time monitoring bloodstream and surgical site

infections (Russo, et al., 2018). Apart from that, the unit is in charge of implementation and

monitoring of hygiene, reducing the emergence of antibiotic-resistant organisms and at the same

time ensuring that infection control guidelines are adhered to within clinical settings. Further, the

unit is supposed to ensure that buildings are renovated and projects designed according to the

required clinical standards like managing the supply of medical equipment to ensure that they

meet the standards established under different medical and clinical standards.

According to the Bedoya, et al. (2017), infection prevention and control practices are a

characteristic of the whole healthcare system and not just an individual healthcare provider. This

implies that the prevention and control of infections are critical in the well-functioning of a

healthcare system. The WHO estimates that around 165,000 Australians contract hospital-related

infections every year which can be prevented (Mitchell, 2017). This challenge has been

attributed to the lack of health-associated infection surveillance which can capture the changes in

the country. This burden is not all about infection but rather some patients die due to these

infections while others are forced to stay longer in hospitals for treatment. In a review

by Mitchell, Shaban, MacBeth, Wood, & Russo (2017) reported that there is limited data on

common infection in Australia due to lack of health surveillance system that can capture and

report.

Stone (2019) adds that having reliable estimate data on health associated infections forms

the basis of prioritization of the prevention and control strategies while at the same time

providing a benchmark for the future. This shows that the existing strategies are limited in the

prevention of infections which call for the need to address the gaps by bringing together different

government bodies which can be important in achieving consensus on prevention approaches and

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

NATIONAL SAFETY AND QUALITY HEALTH SERVICE STANDARD 3 5

surveillance for regular reporting. In addition to the health associated infection programs also

need to be established to capture and report relevant data that can inform recommendations for

research and development. In most cases, the biggest challenge that has been faced is the failure

to enforce accountability within clinical environments as a way of ensuring professional

compliance. This is because low compliance rates in most healthcare situations are regarded as

system or problem failures.

Accreditation plan

The Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (ACHS) is charged with the evaluation,

assessment, and improvement of efficiency, effectiveness, and quality within Australian

hospitals. Each hospital is required to undergo accreditation tests to assess whether it meets the

requirements as set out by the law or not. According to Scott (2018), the March 2018 ACHS

assessment of Canberra hospital revealed that it failed to meet 33 core criteria out of 209, where

two were ranked as extreme risk and six ranked as high. This means that patients attending this

hospital were at the extreme and high risk of health-related challenges. The challenges were

related to fragmentation, lack of cohesion and the failure for the organization to focus on what

was good for the patient and the larger Canberra (White, 2018). The hospital was thus given a

second chance to turn around the 33 core criteria that it failed to meet in March. This means that

the hospital was awarded the accreditation certificate for three years after a second review.

For standard three, the hospital was reported to be compliant with most of the

requirements based on the assessment that was done by ACHS. Since the hospital was accredited

in 2018, it means that it is free to operate for the next two years as they wait for another

accreditation in 2022. This is because the hospital passed all the 42 requirements of standard

three and all the 209 requirement standards after a second review (ACT Health, 2018). The

surveillance for regular reporting. In addition to the health associated infection programs also

need to be established to capture and report relevant data that can inform recommendations for

research and development. In most cases, the biggest challenge that has been faced is the failure

to enforce accountability within clinical environments as a way of ensuring professional

compliance. This is because low compliance rates in most healthcare situations are regarded as

system or problem failures.

Accreditation plan

The Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (ACHS) is charged with the evaluation,

assessment, and improvement of efficiency, effectiveness, and quality within Australian

hospitals. Each hospital is required to undergo accreditation tests to assess whether it meets the

requirements as set out by the law or not. According to Scott (2018), the March 2018 ACHS

assessment of Canberra hospital revealed that it failed to meet 33 core criteria out of 209, where

two were ranked as extreme risk and six ranked as high. This means that patients attending this

hospital were at the extreme and high risk of health-related challenges. The challenges were

related to fragmentation, lack of cohesion and the failure for the organization to focus on what

was good for the patient and the larger Canberra (White, 2018). The hospital was thus given a

second chance to turn around the 33 core criteria that it failed to meet in March. This means that

the hospital was awarded the accreditation certificate for three years after a second review.

For standard three, the hospital was reported to be compliant with most of the

requirements based on the assessment that was done by ACHS. Since the hospital was accredited

in 2018, it means that it is free to operate for the next two years as they wait for another

accreditation in 2022. This is because the hospital passed all the 42 requirements of standard

three and all the 209 requirement standards after a second review (ACT Health, 2018). The

NATIONAL SAFETY AND QUALITY HEALTH SERVICE STANDARD 3 6

management of standard three is driven by a small multidisciplinary team which is fragmented

and reports through three streams: the infection d Prevention Service and Central equipment

service report to Clinical Support Service the domestic and environmental service and lastly the

d building maintenance report through to Health Infrastructure. However, the recommendation

after the accreditation review highlighted the need for the hospital to restructure and review how

the health associated infection committee interacts with the top-level management in the

organization and also the need to review the resource allocation model towards the Infection

Prevention and Surveillance Service (IP&S) to maximize quality improvement (ACT Health,

2018).

The operation of the Infection prevention and control systems as established by standard

three is through infection control where risks are identified early and actions implemented

through careful monitoring to ensure vigilance. Despite the fact the hospital has a risk register

number, the hospital needs to have a Gantt chart for addressing the concerns and the use of

policies for dealing with the risk areas. The fact that the hospital failed to meet 33 out 209

standards during the initial assessment means that there is need to focus on the policy areas and

organization risk assessment standards to create the best outcomes for the organization and

ACHS compliance.

Conclusion

Nunez-Nunez, et al. (2017) states that the WHO views Healthcare-associated infection

(HAI) surveillance programs as critical in the prevention of infections and increasing of health

outcomes. These programs enable easy monitoring of outcomes of current practice and reporting

timely feedback that can be used for clinical practice. As a country, Australia lacks a

comprehensive national HAI surveillance program that can be implemented in different

management of standard three is driven by a small multidisciplinary team which is fragmented

and reports through three streams: the infection d Prevention Service and Central equipment

service report to Clinical Support Service the domestic and environmental service and lastly the

d building maintenance report through to Health Infrastructure. However, the recommendation

after the accreditation review highlighted the need for the hospital to restructure and review how

the health associated infection committee interacts with the top-level management in the

organization and also the need to review the resource allocation model towards the Infection

Prevention and Surveillance Service (IP&S) to maximize quality improvement (ACT Health,

2018).

The operation of the Infection prevention and control systems as established by standard

three is through infection control where risks are identified early and actions implemented

through careful monitoring to ensure vigilance. Despite the fact the hospital has a risk register

number, the hospital needs to have a Gantt chart for addressing the concerns and the use of

policies for dealing with the risk areas. The fact that the hospital failed to meet 33 out 209

standards during the initial assessment means that there is need to focus on the policy areas and

organization risk assessment standards to create the best outcomes for the organization and

ACHS compliance.

Conclusion

Nunez-Nunez, et al. (2017) states that the WHO views Healthcare-associated infection

(HAI) surveillance programs as critical in the prevention of infections and increasing of health

outcomes. These programs enable easy monitoring of outcomes of current practice and reporting

timely feedback that can be used for clinical practice. As a country, Australia lacks a

comprehensive national HAI surveillance program that can be implemented in different

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

NATIONAL SAFETY AND QUALITY HEALTH SERVICE STANDARD 3 7

healthcare organizations (Russo, et al., 2018). Although the Australian Commission for Safety

and Quality in Health Care has developed HAI national initiatives, there is a risk of misdirecting

them due to the lack of data that informs the interventions since the government lacks reliable

national HAI data. This calls for the need to develop national initiatives that will lead to reliable

data to be used in the validation of the different infection prevention methods that are adopted.

healthcare organizations (Russo, et al., 2018). Although the Australian Commission for Safety

and Quality in Health Care has developed HAI national initiatives, there is a risk of misdirecting

them due to the lack of data that informs the interventions since the government lacks reliable

national HAI data. This calls for the need to develop national initiatives that will lead to reliable

data to be used in the validation of the different infection prevention methods that are adopted.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

NATIONAL SAFETY AND QUALITY HEALTH SERVICE STANDARD 3 8

References

ACT Government. (2019). Infection Prevention and Control. Retrieved from ACT Government:

https://www.health.act.gov.au/about-our-health-system/accreditation/infection-

prevention-and-control

ACT Health. (2018). Report of the ACHS National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS)

Standards Survey Canberra, ACT . The Australian Council on Healthcare Standard.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2017). National Safety and

Quality Health Service Standards (2nd ed.). Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety

and Quality in Health Care.

Bedoya, G., Dolinger, A., Rogo, K., Mwaura, N., Wafula, F., Coarasa, J., . . . Das, J. (2017).

Observations of infection prevention and control practices in primary health care, Kenya.

Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 95, 503-516.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.16.179499

Black, A. T., Balneaves, L. G., Garossino, C., Puyat, J. H., & Qian, H. (2015). Promoting

Evidence-Based Practice Through a Research Training Program for Point-of-Care

Clinicians. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 45(1), 14–20.

Mitchell, B., Shaban, R. Z., MacBeth, D., Wood, C.-J., & L.Russo, P. (2017). The burden of

healthcare-associated infection in Australian hospitals: A systematic review of the

literature. Infection, Disease & Health, 22(3), 117-128.

doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idh.2017.07.001

Mitchell, B. (2017 , August ). Here’s how many people get infections in Australian hospitals

every year. The Conversation.

References

ACT Government. (2019). Infection Prevention and Control. Retrieved from ACT Government:

https://www.health.act.gov.au/about-our-health-system/accreditation/infection-

prevention-and-control

ACT Health. (2018). Report of the ACHS National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS)

Standards Survey Canberra, ACT . The Australian Council on Healthcare Standard.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2017). National Safety and

Quality Health Service Standards (2nd ed.). Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety

and Quality in Health Care.

Bedoya, G., Dolinger, A., Rogo, K., Mwaura, N., Wafula, F., Coarasa, J., . . . Das, J. (2017).

Observations of infection prevention and control practices in primary health care, Kenya.

Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 95, 503-516.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.16.179499

Black, A. T., Balneaves, L. G., Garossino, C., Puyat, J. H., & Qian, H. (2015). Promoting

Evidence-Based Practice Through a Research Training Program for Point-of-Care

Clinicians. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 45(1), 14–20.

Mitchell, B., Shaban, R. Z., MacBeth, D., Wood, C.-J., & L.Russo, P. (2017). The burden of

healthcare-associated infection in Australian hospitals: A systematic review of the

literature. Infection, Disease & Health, 22(3), 117-128.

doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idh.2017.07.001

Mitchell, B. (2017 , August ). Here’s how many people get infections in Australian hospitals

every year. The Conversation.

NATIONAL SAFETY AND QUALITY HEALTH SERVICE STANDARD 3 9

Nunez-Nunez, M., Navarro, M. D., Gkolia, P., Rajendran, N. B., Toro, M. D., Voss, A., . . .

Rodríguez-Bano, J. (2017). Surveillance Systems from Public Health Institutions and

Scientific Societies for Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare-Associated Infections in

Europe (SUSPIRE): protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open, 7.

doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014538

Russo, P. L., Stewardson, A., Cheng, A. C., Bucknall, T., Marimuthu, K., & Mitchell, B. G.

(2018). Establishing the prevalence of healthcare-associated infections in Australian

hospitals: protocol for the Comprehensive Healthcare Associated Infection National

Surveillance (CHAINS) study. BMJ Open , 8. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024924

Scott, E. (2018, April). Canberra Hospital faces accreditation issues, commits to more than 30

changes. ABC News, pp. 1-7.

Stone, P. W. (2019). Economic burden of healthcare-associated infections: an American

perspective. Expert Review in Pharmacoeconomic Outcomes Research, 9(5), 417–422.

White, D. (2018 , August ). Canberra Hospital accredited for next three years . The Canberra

Times, pp. 1--18.

Nunez-Nunez, M., Navarro, M. D., Gkolia, P., Rajendran, N. B., Toro, M. D., Voss, A., . . .

Rodríguez-Bano, J. (2017). Surveillance Systems from Public Health Institutions and

Scientific Societies for Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare-Associated Infections in

Europe (SUSPIRE): protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open, 7.

doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014538

Russo, P. L., Stewardson, A., Cheng, A. C., Bucknall, T., Marimuthu, K., & Mitchell, B. G.

(2018). Establishing the prevalence of healthcare-associated infections in Australian

hospitals: protocol for the Comprehensive Healthcare Associated Infection National

Surveillance (CHAINS) study. BMJ Open , 8. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024924

Scott, E. (2018, April). Canberra Hospital faces accreditation issues, commits to more than 30

changes. ABC News, pp. 1-7.

Stone, P. W. (2019). Economic burden of healthcare-associated infections: an American

perspective. Expert Review in Pharmacoeconomic Outcomes Research, 9(5), 417–422.

White, D. (2018 , August ). Canberra Hospital accredited for next three years . The Canberra

Times, pp. 1--18.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

NATIONAL SAFETY AND QUALITY HEALTH SERVICE STANDARD 3 10

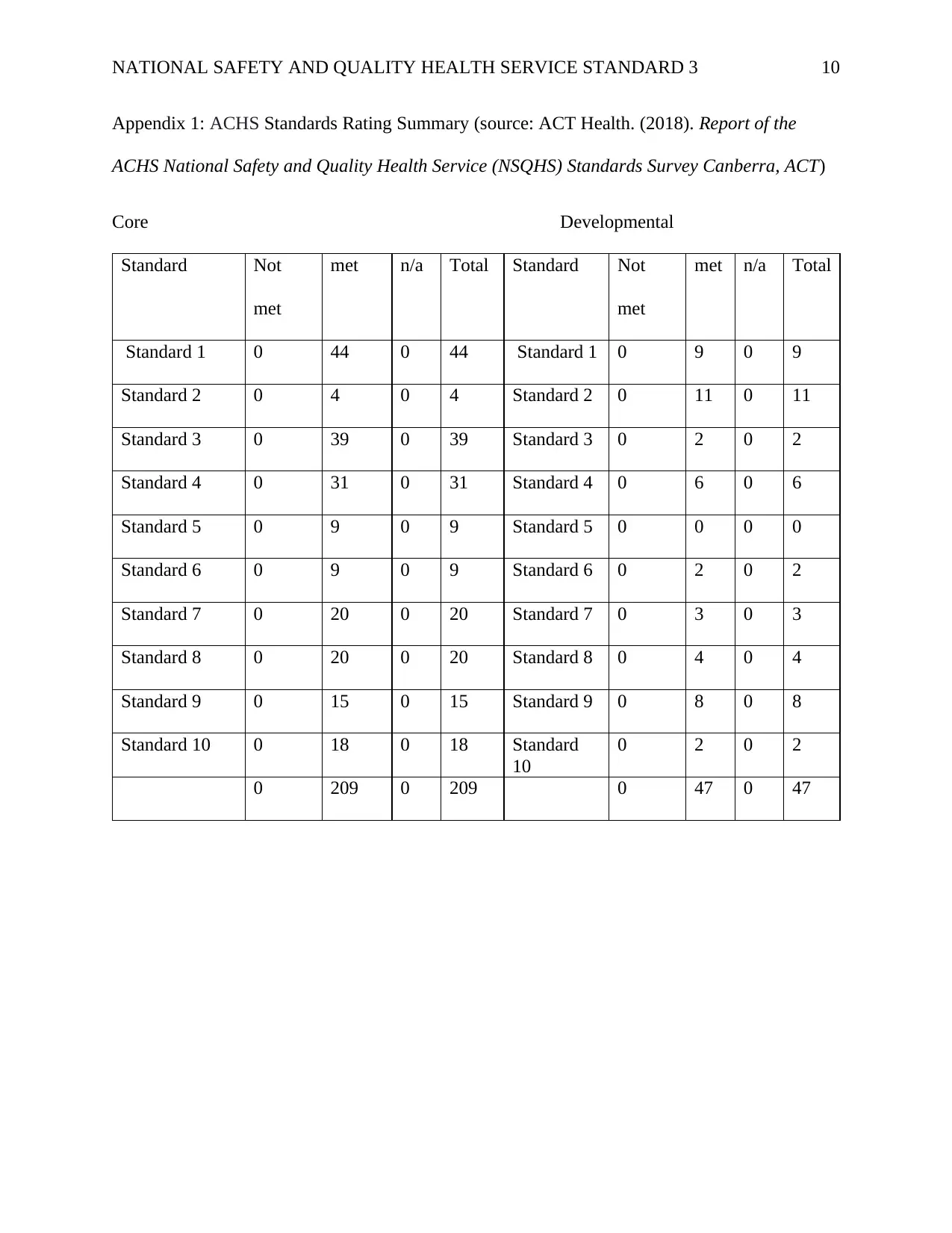

Appendix 1: ACHS Standards Rating Summary (source: ACT Health. (2018). Report of the

ACHS National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS) Standards Survey Canberra, ACT)

Core Developmental

Standard Not

met

met n/a Total Standard Not

met

met n/a Total

Standard 1 0 44 0 44 Standard 1 0 9 0 9

Standard 2 0 4 0 4 Standard 2 0 11 0 11

Standard 3 0 39 0 39 Standard 3 0 2 0 2

Standard 4 0 31 0 31 Standard 4 0 6 0 6

Standard 5 0 9 0 9 Standard 5 0 0 0 0

Standard 6 0 9 0 9 Standard 6 0 2 0 2

Standard 7 0 20 0 20 Standard 7 0 3 0 3

Standard 8 0 20 0 20 Standard 8 0 4 0 4

Standard 9 0 15 0 15 Standard 9 0 8 0 8

Standard 10 0 18 0 18 Standard

10

0 2 0 2

0 209 0 209 0 47 0 47

Appendix 1: ACHS Standards Rating Summary (source: ACT Health. (2018). Report of the

ACHS National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS) Standards Survey Canberra, ACT)

Core Developmental

Standard Not

met

met n/a Total Standard Not

met

met n/a Total

Standard 1 0 44 0 44 Standard 1 0 9 0 9

Standard 2 0 4 0 4 Standard 2 0 11 0 11

Standard 3 0 39 0 39 Standard 3 0 2 0 2

Standard 4 0 31 0 31 Standard 4 0 6 0 6

Standard 5 0 9 0 9 Standard 5 0 0 0 0

Standard 6 0 9 0 9 Standard 6 0 2 0 2

Standard 7 0 20 0 20 Standard 7 0 3 0 3

Standard 8 0 20 0 20 Standard 8 0 4 0 4

Standard 9 0 15 0 15 Standard 9 0 8 0 8

Standard 10 0 18 0 18 Standard

10

0 2 0 2

0 209 0 209 0 47 0 47

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

NATIONAL SAFETY AND QUALITY HEALTH SERVICE STANDARD 3 11

1 out of 11

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.