MKTG2010: NBN Corp - Reality TV Show Impact & Attitude Report

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/09

|24

|4181

|184

Report

AI Summary

This report investigates the impact of real-life television shows on viewers, prepared for NBN Corporation's potential launch of a new reality TV series. It includes both qualitative and quantitative explorations, examining the genuineness of reality TV programs and their societal consequences. The qualitative analysis, based on a focus group transcript, reveals concerns about the authenticity and potential negative effects of reality TV. The quantitative analysis, using data from 300 respondents, tests several hypotheses related to viewer attitudes, gender differences in enjoyment, the relationship between age and show preference, and the importance of attractive participants. Statistical tests such as Mann-Whitney U, Chi-Square, and Kruskal-Wallis are employed to analyze the data. The report concludes with a discussion of the findings and recommendations for NBN Corporation.

[1]

Impact of Real-Life Television Shows on Viewers:

An Investigation for Launch of a New Real-Life TV Series

Impact of Real-Life Television Shows on Viewers:

An Investigation for Launch of a New Real-Life TV Series

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

[2]

Table of Contents

1.0 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................3

2.0 Qualitative Exploration..........................................................................................................................3

2.1 Genuineness of the television live programs.....................................................................................3

2.2 Consequences of the live programs on the society...........................................................................4

2.3 Conceptual Model.............................................................................................................................5

3.0 Quantitative Exploration........................................................................................................................6

3.1 Sample Analysis.................................................................................................................................6

3.2 Hypotheses Testing............................................................................................................................8

A. First Hypothesis...........................................................................................................................8

B. Second Hypothesis.......................................................................................................................9

C. Third Hypothesis..........................................................................................................................9

D. Fourth Hypothesis......................................................................................................................10

E. Fifth Hypothesis.........................................................................................................................10

F. Sixth Hypothesis........................................................................................................................11

4.0 Discussion............................................................................................................................................12

5.0 Conclusion and Recommendation.......................................................................................................13

6.0 References...........................................................................................................................................14

7.0 Appendices..........................................................................................................................................15

7.1 Appendix: H1...................................................................................................................................15

7.2 Appendix: H2...................................................................................................................................17

7.3 Appendix: H3...................................................................................................................................19

7.4 Appendix: H4...................................................................................................................................20

7.5 Appendix: H5...................................................................................................................................21

7.6 Appendix: H6...................................................................................................................................23

Table of Contents

1.0 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................3

2.0 Qualitative Exploration..........................................................................................................................3

2.1 Genuineness of the television live programs.....................................................................................3

2.2 Consequences of the live programs on the society...........................................................................4

2.3 Conceptual Model.............................................................................................................................5

3.0 Quantitative Exploration........................................................................................................................6

3.1 Sample Analysis.................................................................................................................................6

3.2 Hypotheses Testing............................................................................................................................8

A. First Hypothesis...........................................................................................................................8

B. Second Hypothesis.......................................................................................................................9

C. Third Hypothesis..........................................................................................................................9

D. Fourth Hypothesis......................................................................................................................10

E. Fifth Hypothesis.........................................................................................................................10

F. Sixth Hypothesis........................................................................................................................11

4.0 Discussion............................................................................................................................................12

5.0 Conclusion and Recommendation.......................................................................................................13

6.0 References...........................................................................................................................................14

7.0 Appendices..........................................................................................................................................15

7.1 Appendix: H1...................................................................................................................................15

7.2 Appendix: H2...................................................................................................................................17

7.3 Appendix: H3...................................................................................................................................19

7.4 Appendix: H4...................................................................................................................................20

7.5 Appendix: H5...................................................................................................................................21

7.6 Appendix: H6...................................................................................................................................23

[3]

1.0 Introduction

Effect of excessive and tortuous television viewing has always been associated with

adverse impact on behavior and health of the viewer. Negative impact on education and

psychological attributes amplifies the need of parental guidance based program viewing for the

teenagers. Long lasting adverse effect of continuous television viewing has long been discussed

by many researchers. The current study was to facilitate the NBN Corporation with the research

on the necessity of introduction of their real-life TV show.

2.0 Qualitative Exploration

2.1 Genuineness of the television live programs

Real-life TV programs have manifested its’ advantages of providing information

attainment for viewers but parallel controversies have also been created as well. The profile of

the participants includes good looking human beings who can entertain the audiences. Hence,

specific brand of acting performance becomes inevitable for these wisely selected candidates.

Impulsive decision making, impossible looking ventures, and enthusiasm are the elements of a

fascinating real life TV program. These physiognomies keep the viewers glued to the programs,

trying to predict the sequence of the show. These real life shows entirely follow the course of

set-up activities from the commencement day. Unfortunately, the focus of the programs slowly

shifts away from the real-life and the participants concentrate on the publicity from the show

markedly for a negative reason. The entertaining significance gets replaced by filthy

psychological hindrance, and the audience sometimes gets petrified due to their involvement

with the actions in the show. This particular strategy articulates to retain the viewers of the

program and influences to stay tuned to the shows. Alacritous participation reveals unpleasant

part of the participants, where they were familiar with the dreadful reality of the programs. The

characters of these shows possibly enter in some kind of monetary agreement with the producers,

and the influence of the characters of the shows captivates the viewer’s imagination. Invade into

their private life that way, unless they are moved with some lucrative rewards. Audiences gets

affected and confused by the ugly sides of television instead of watching real life experiences,

1.0 Introduction

Effect of excessive and tortuous television viewing has always been associated with

adverse impact on behavior and health of the viewer. Negative impact on education and

psychological attributes amplifies the need of parental guidance based program viewing for the

teenagers. Long lasting adverse effect of continuous television viewing has long been discussed

by many researchers. The current study was to facilitate the NBN Corporation with the research

on the necessity of introduction of their real-life TV show.

2.0 Qualitative Exploration

2.1 Genuineness of the television live programs

Real-life TV programs have manifested its’ advantages of providing information

attainment for viewers but parallel controversies have also been created as well. The profile of

the participants includes good looking human beings who can entertain the audiences. Hence,

specific brand of acting performance becomes inevitable for these wisely selected candidates.

Impulsive decision making, impossible looking ventures, and enthusiasm are the elements of a

fascinating real life TV program. These physiognomies keep the viewers glued to the programs,

trying to predict the sequence of the show. These real life shows entirely follow the course of

set-up activities from the commencement day. Unfortunately, the focus of the programs slowly

shifts away from the real-life and the participants concentrate on the publicity from the show

markedly for a negative reason. The entertaining significance gets replaced by filthy

psychological hindrance, and the audience sometimes gets petrified due to their involvement

with the actions in the show. This particular strategy articulates to retain the viewers of the

program and influences to stay tuned to the shows. Alacritous participation reveals unpleasant

part of the participants, where they were familiar with the dreadful reality of the programs. The

characters of these shows possibly enter in some kind of monetary agreement with the producers,

and the influence of the characters of the shows captivates the viewer’s imagination. Invade into

their private life that way, unless they are moved with some lucrative rewards. Audiences gets

affected and confused by the ugly sides of television instead of watching real life experiences,

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

[4]

which in turn affects the overall perspective of life. But, if the outcome does have any

implication on an individual and only the entertainment value is appreciated, then the affect

fizzes out. Viewers want TV shows drafted with skills & techniques, where the idea is to make it

interesting and close to the real life (Allen & Mendick, 2013).

2.2 Consequences of the live programs on the society

The authenticity of the shows does not matter too much if only the entertainment value is

apprehended. The negative impact of the shows becomes the primary objective instead of

focusing on the meaningful real-life constituent. The participants reveal impression about their

acknowledgement of the negative influence factors of the real-life TV shows. The confusion

between the reality and so-called realities should not be utilized by the TV stations. The

producers should bear in mind about the social responsibility issue and should not make the

power of mass media as a cliché. Every so often the audience gets involved with the episodes of

the shows which go far beyond the entertaining value. The emotions go with the development of

the reality show and the probability of staying till the end becomes very high. It is even very

hazardous for kids who can’t differentiate between fiction and reality (An & Lee, 2010).

Eventually they get too engaged in these shows and take them seriously. Guidance and control

over the demographics of the viewers, turns out to be difficult (Swinburn & Shelly, 2009).

Therefore, mentally immature people take the shows seriously and at some point of time in life,

they experience trouble differentiating fiction from reality. These viewers get emotionally

affected at the end of the show as they probably dedicate their time completely in the programs.

Sometimes, people try to make contacts with the real life show participants, causing gross

violation against privacy of the actors. Few real-life programs such as game shows or

educational talk provide entertainment and leisure to viewers. These programs should be

encouraged instead of the usual theatrical serials, which will promote moral ideologies for the

pleasure of entertainment. The controversial shows should be treated indifferently despite their

filthiness and should not take them too seriously.

which in turn affects the overall perspective of life. But, if the outcome does have any

implication on an individual and only the entertainment value is appreciated, then the affect

fizzes out. Viewers want TV shows drafted with skills & techniques, where the idea is to make it

interesting and close to the real life (Allen & Mendick, 2013).

2.2 Consequences of the live programs on the society

The authenticity of the shows does not matter too much if only the entertainment value is

apprehended. The negative impact of the shows becomes the primary objective instead of

focusing on the meaningful real-life constituent. The participants reveal impression about their

acknowledgement of the negative influence factors of the real-life TV shows. The confusion

between the reality and so-called realities should not be utilized by the TV stations. The

producers should bear in mind about the social responsibility issue and should not make the

power of mass media as a cliché. Every so often the audience gets involved with the episodes of

the shows which go far beyond the entertaining value. The emotions go with the development of

the reality show and the probability of staying till the end becomes very high. It is even very

hazardous for kids who can’t differentiate between fiction and reality (An & Lee, 2010).

Eventually they get too engaged in these shows and take them seriously. Guidance and control

over the demographics of the viewers, turns out to be difficult (Swinburn & Shelly, 2009).

Therefore, mentally immature people take the shows seriously and at some point of time in life,

they experience trouble differentiating fiction from reality. These viewers get emotionally

affected at the end of the show as they probably dedicate their time completely in the programs.

Sometimes, people try to make contacts with the real life show participants, causing gross

violation against privacy of the actors. Few real-life programs such as game shows or

educational talk provide entertainment and leisure to viewers. These programs should be

encouraged instead of the usual theatrical serials, which will promote moral ideologies for the

pleasure of entertainment. The controversial shows should be treated indifferently despite their

filthiness and should not take them too seriously.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

[5]

2.3 Conceptual Model

Figure 1: Impact of Real life TV shows from multiple viewpoints

TVShowsImpactViewersPersonalityPessimisticvaluesAttitudeSensitivityTrustIssusesPerceptionArtificialParticipantsLossofprivacyPublicity

2.3 Conceptual Model

Figure 1: Impact of Real life TV shows from multiple viewpoints

TVShowsImpactViewersPersonalityPessimisticvaluesAttitudeSensitivityTrustIssusesPerceptionArtificialParticipantsLossofprivacyPublicity

[6]

3.0 Quantitative Exploration

3.1 Sample Analysis

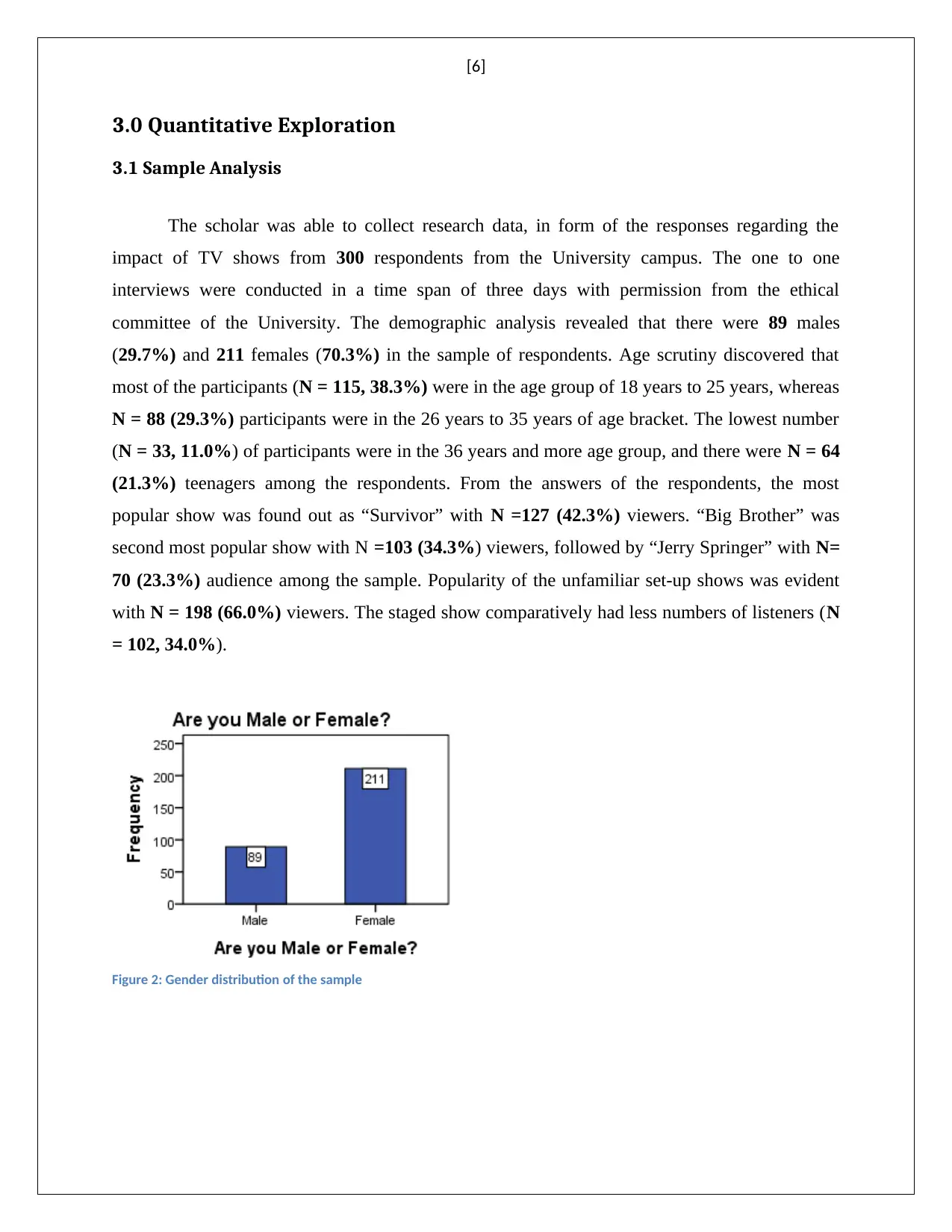

The scholar was able to collect research data, in form of the responses regarding the

impact of TV shows from 300 respondents from the University campus. The one to one

interviews were conducted in a time span of three days with permission from the ethical

committee of the University. The demographic analysis revealed that there were 89 males

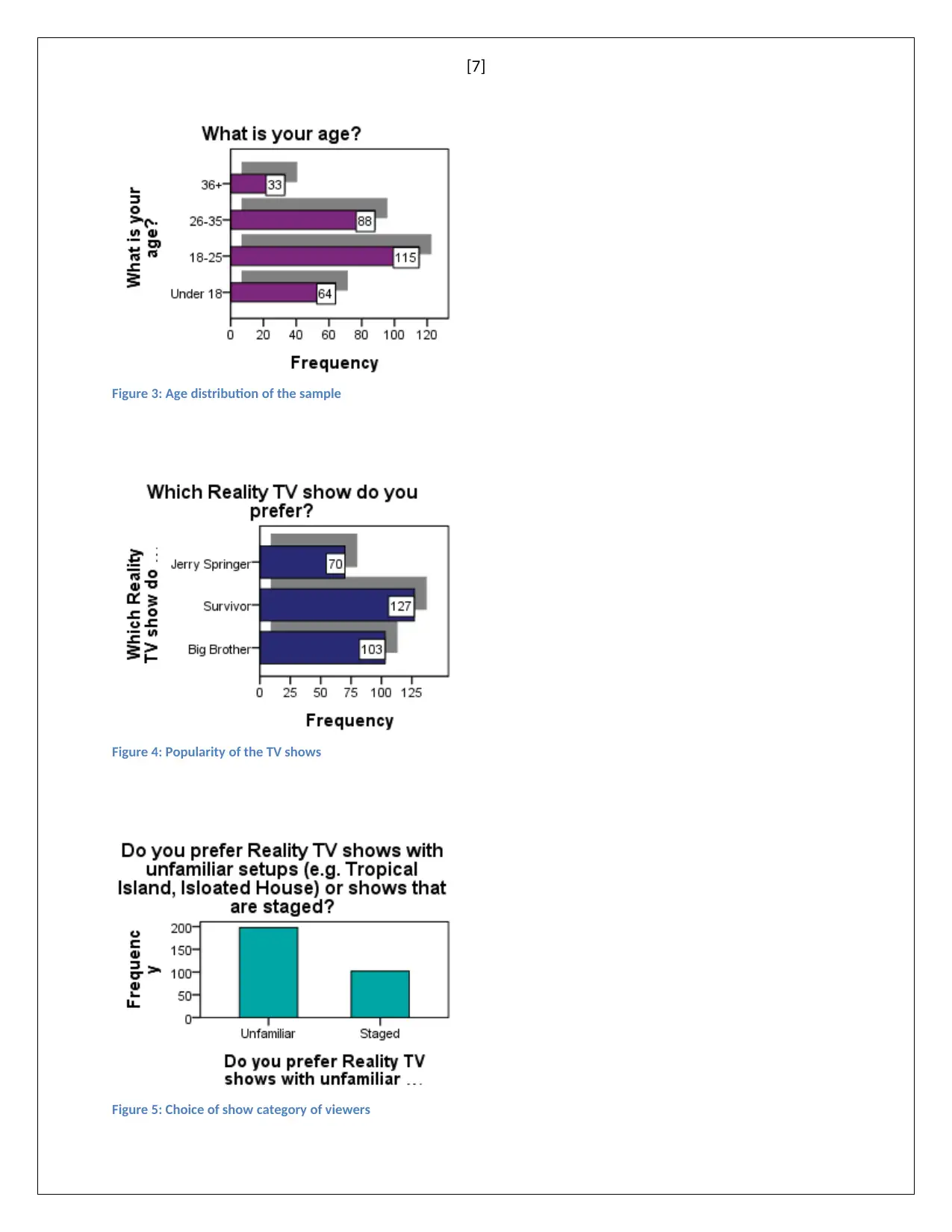

(29.7%) and 211 females (70.3%) in the sample of respondents. Age scrutiny discovered that

most of the participants (N = 115, 38.3%) were in the age group of 18 years to 25 years, whereas

N = 88 (29.3%) participants were in the 26 years to 35 years of age bracket. The lowest number

(N = 33, 11.0%) of participants were in the 36 years and more age group, and there were N = 64

(21.3%) teenagers among the respondents. From the answers of the respondents, the most

popular show was found out as “Survivor” with N =127 (42.3%) viewers. “Big Brother” was

second most popular show with N =103 (34.3%) viewers, followed by “Jerry Springer” with N=

70 (23.3%) audience among the sample. Popularity of the unfamiliar set-up shows was evident

with N = 198 (66.0%) viewers. The staged show comparatively had less numbers of listeners (N

= 102, 34.0%).

Figure 2: Gender distribution of the sample

3.0 Quantitative Exploration

3.1 Sample Analysis

The scholar was able to collect research data, in form of the responses regarding the

impact of TV shows from 300 respondents from the University campus. The one to one

interviews were conducted in a time span of three days with permission from the ethical

committee of the University. The demographic analysis revealed that there were 89 males

(29.7%) and 211 females (70.3%) in the sample of respondents. Age scrutiny discovered that

most of the participants (N = 115, 38.3%) were in the age group of 18 years to 25 years, whereas

N = 88 (29.3%) participants were in the 26 years to 35 years of age bracket. The lowest number

(N = 33, 11.0%) of participants were in the 36 years and more age group, and there were N = 64

(21.3%) teenagers among the respondents. From the answers of the respondents, the most

popular show was found out as “Survivor” with N =127 (42.3%) viewers. “Big Brother” was

second most popular show with N =103 (34.3%) viewers, followed by “Jerry Springer” with N=

70 (23.3%) audience among the sample. Popularity of the unfamiliar set-up shows was evident

with N = 198 (66.0%) viewers. The staged show comparatively had less numbers of listeners (N

= 102, 34.0%).

Figure 2: Gender distribution of the sample

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

[7]

Figure 3: Age distribution of the sample

Figure 4: Popularity of the TV shows

Figure 5: Choice of show category of viewers

Figure 3: Age distribution of the sample

Figure 4: Popularity of the TV shows

Figure 5: Choice of show category of viewers

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

[8]

3.2 Hypotheses Testing

In the current analysis six hypotheses were tested using appropriate statistical measures

and statistics. The SPSS software environment was used for the statistical evaluation and the

calculated raw data has been provided in the appendices section of the present work.

A. First Hypothesis

The nature of the data of the responses of the participants was ordinal in nature, as the

responses were collected trough a likert scale format. The two fields respectively “relate to

participants on reality TV” (SW = 0.9, P < 0.05) and “enjoy watching reality TV shows” (SW =

0.91, p < 0.05) were not normal according to Shapiro-Wilk test. However, normality check of

ordinal data was considered of no use, and hence Kruskal’s Gamma was used for inspecting the

correlation between the two variables (Döring et al., 2017). The value of the correlation

(Gamma = 0.028, p = 0.671) signified statistically insignificant correlation between the two

factors. Confirmatory test was done using Spearman’s correlation (R = 0.025, p = 0.663) and the

result was equally insignificant. From the evidences the null hypothesis failed to get rejected, and

no correlation was found between “relate to participants on reality TV” and “enjoy watching

reality TV shows”.

3.2 Hypotheses Testing

In the current analysis six hypotheses were tested using appropriate statistical measures

and statistics. The SPSS software environment was used for the statistical evaluation and the

calculated raw data has been provided in the appendices section of the present work.

A. First Hypothesis

The nature of the data of the responses of the participants was ordinal in nature, as the

responses were collected trough a likert scale format. The two fields respectively “relate to

participants on reality TV” (SW = 0.9, P < 0.05) and “enjoy watching reality TV shows” (SW =

0.91, p < 0.05) were not normal according to Shapiro-Wilk test. However, normality check of

ordinal data was considered of no use, and hence Kruskal’s Gamma was used for inspecting the

correlation between the two variables (Döring et al., 2017). The value of the correlation

(Gamma = 0.028, p = 0.671) signified statistically insignificant correlation between the two

factors. Confirmatory test was done using Spearman’s correlation (R = 0.025, p = 0.663) and the

result was equally insignificant. From the evidences the null hypothesis failed to get rejected, and

no correlation was found between “relate to participants on reality TV” and “enjoy watching

reality TV shows”.

[9]

B. Second Hypothesis

The gender disparity in enjoyment while watching TV shows was compared using non

parametric test (Corder & Foreman, 2014). The data for enjoyment of TV shows was ordinal in

nature, and the difference for two levels of the nominal variable, gender was evaluated using

Mann-Whitney U test. Mann- Whitney U test (Stat = 3420.00, p < 0.05) and a parallel Wilcoxon

W test (Stat = 7425.00, p < 0.05) confirmed statistically significant difference in enjoyment of

watching TV shows for the two genders. The results were confirmed using two sample

Kolmogorov- Smirnov Z test (Stat = 4.14, p < 0.05) (Drezner & Turel, 2011). Based on the test

results, it was evident that females with mean ranks (MR) of 178.79 were enjoying the TV shows

more than the men (MR = 83.43). Hence, the null hypothesis was rejected against the alternate

hypothesis at 5% level of significance.

C. Third Hypothesis

The reality show preference of respondents was a nominal variable in nature and age was

a continuous variable. Hence, to test the association, non parametric Chi-Square test was used

along with cross tabulation. The Pearson Chi-Square ( χ2=219 .57 , p<0 . 05 ) and the likelihood

ratio test (LR = 236.52, p < 0.05) confirmed statistically significant relation of age with choice

of TV shows. It was also noticed that age of 59.67% (N = 179) of the respondents were below

25 years. Therefore, based on the support results the null hypothesis was rejected at 5%

significance level. There was a statistically significant relation between age and selection of the

TV show among the respondents.

B. Second Hypothesis

The gender disparity in enjoyment while watching TV shows was compared using non

parametric test (Corder & Foreman, 2014). The data for enjoyment of TV shows was ordinal in

nature, and the difference for two levels of the nominal variable, gender was evaluated using

Mann-Whitney U test. Mann- Whitney U test (Stat = 3420.00, p < 0.05) and a parallel Wilcoxon

W test (Stat = 7425.00, p < 0.05) confirmed statistically significant difference in enjoyment of

watching TV shows for the two genders. The results were confirmed using two sample

Kolmogorov- Smirnov Z test (Stat = 4.14, p < 0.05) (Drezner & Turel, 2011). Based on the test

results, it was evident that females with mean ranks (MR) of 178.79 were enjoying the TV shows

more than the men (MR = 83.43). Hence, the null hypothesis was rejected against the alternate

hypothesis at 5% level of significance.

C. Third Hypothesis

The reality show preference of respondents was a nominal variable in nature and age was

a continuous variable. Hence, to test the association, non parametric Chi-Square test was used

along with cross tabulation. The Pearson Chi-Square ( χ2=219 .57 , p<0 . 05 ) and the likelihood

ratio test (LR = 236.52, p < 0.05) confirmed statistically significant relation of age with choice

of TV shows. It was also noticed that age of 59.67% (N = 179) of the respondents were below

25 years. Therefore, based on the support results the null hypothesis was rejected at 5%

significance level. There was a statistically significant relation between age and selection of the

TV show among the respondents.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

[10]

D. Fourth Hypothesis

Both the factors of the testing were ordinal in nature; hence, non-parametric test was

opted for establishing correlation between the variables (Mayers, 2013). The correlation was

measured by Kendall’s tau-b (Value = 0.016, p = 0.744), and Kruskal’s Gamma (Value = 0.022,

p = 0.744). Spearman correlation (R = 0.019, p = 0.912) also confirmed the results of the above

correlations. A very weak positive correlation was observed between the two ordinal factors, and

statistically the correlation was not significant at 5% level of significance. Hence, based on the

results, null hypothesis failed to get rejected. There was no significant correlation between

enjoyment of the TV shows and delineation of real life in a reality TV show.

E. Fifth Hypothesis

Testing of the above hypothesis at 5% level of significance was done using non-

parametric Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test for the two ordinal factors. Three test conditions were

evaluated for average ranks. The mean negative ranks between “Depicting real life behaviors on

reality TV” and “Having attractive participants on reality TV is important” was 89.45 (N = 92),

whereas the mean for positive ranks was 132.87 (N = 138). The Wilcox Signed Rank test

statistics (Z = -5.106, p < 0.05) established the alternate hypothesis. The null hypothesis was

rejected at 5% level of significance, and a statistically significant difference was observed

between the variables.

D. Fourth Hypothesis

Both the factors of the testing were ordinal in nature; hence, non-parametric test was

opted for establishing correlation between the variables (Mayers, 2013). The correlation was

measured by Kendall’s tau-b (Value = 0.016, p = 0.744), and Kruskal’s Gamma (Value = 0.022,

p = 0.744). Spearman correlation (R = 0.019, p = 0.912) also confirmed the results of the above

correlations. A very weak positive correlation was observed between the two ordinal factors, and

statistically the correlation was not significant at 5% level of significance. Hence, based on the

results, null hypothesis failed to get rejected. There was no significant correlation between

enjoyment of the TV shows and delineation of real life in a reality TV show.

E. Fifth Hypothesis

Testing of the above hypothesis at 5% level of significance was done using non-

parametric Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test for the two ordinal factors. Three test conditions were

evaluated for average ranks. The mean negative ranks between “Depicting real life behaviors on

reality TV” and “Having attractive participants on reality TV is important” was 89.45 (N = 92),

whereas the mean for positive ranks was 132.87 (N = 138). The Wilcox Signed Rank test

statistics (Z = -5.106, p < 0.05) established the alternate hypothesis. The null hypothesis was

rejected at 5% level of significance, and a statistically significant difference was observed

between the variables.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

[11]

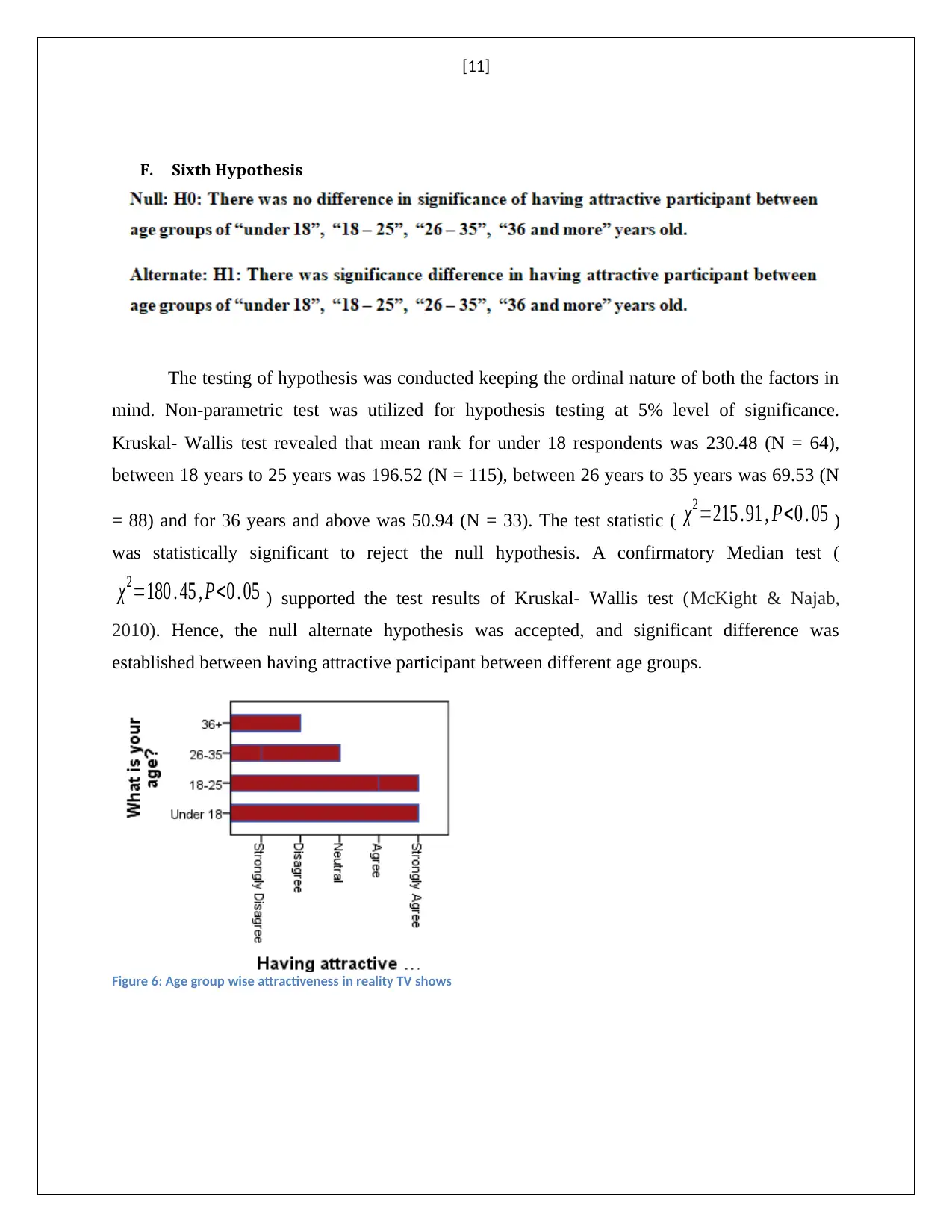

F. Sixth Hypothesis

The testing of hypothesis was conducted keeping the ordinal nature of both the factors in

mind. Non-parametric test was utilized for hypothesis testing at 5% level of significance.

Kruskal- Wallis test revealed that mean rank for under 18 respondents was 230.48 (N = 64),

between 18 years to 25 years was 196.52 (N = 115), between 26 years to 35 years was 69.53 (N

= 88) and for 36 years and above was 50.94 (N = 33). The test statistic ( χ2=215 .91 , P<0 . 05 )

was statistically significant to reject the null hypothesis. A confirmatory Median test (

χ2=180 . 45 , P<0 . 05 ) supported the test results of Kruskal- Wallis test (McKight & Najab,

2010). Hence, the null alternate hypothesis was accepted, and significant difference was

established between having attractive participant between different age groups.

Figure 6: Age group wise attractiveness in reality TV shows

F. Sixth Hypothesis

The testing of hypothesis was conducted keeping the ordinal nature of both the factors in

mind. Non-parametric test was utilized for hypothesis testing at 5% level of significance.

Kruskal- Wallis test revealed that mean rank for under 18 respondents was 230.48 (N = 64),

between 18 years to 25 years was 196.52 (N = 115), between 26 years to 35 years was 69.53 (N

= 88) and for 36 years and above was 50.94 (N = 33). The test statistic ( χ2=215 .91 , P<0 . 05 )

was statistically significant to reject the null hypothesis. A confirmatory Median test (

χ2=180 . 45 , P<0 . 05 ) supported the test results of Kruskal- Wallis test (McKight & Najab,

2010). Hence, the null alternate hypothesis was accepted, and significant difference was

established between having attractive participant between different age groups.

Figure 6: Age group wise attractiveness in reality TV shows

[12]

4.0 Discussion

The qualitative and quantitative data analysis was in line with each other. The qualitative

analysis revealed that the respondents were disturbed about the genuineness of the content of the

shows. The “attitude” towards the “authenticity” of the reality shows was addressed based on the

transcript description of the respondents. The consequences of the real life TV programs were

addressed in the second half of the qualitative analysis, where the respondents’ views on

negative impact of the shows on the society, especially on the children got reflected. The general

awareness about the ways and programs of entertainment in television was eminent from the

discussion in the transcript.

The quantitative analysis sustained the outcome of the qualitative scrutiny. Hypothesis

wise elaboration revealed that, significant relation was missing between enjoyments of TV

viewing and relating participants of the TV shows (H1). Significant gender difference was

observed in enjoyment from TV programs (H2), whereas, no relation was found between

delineation of real life in a reality show and enjoyment of the TV programs (H4). The

noteworthy relation between age groups and reality TV show preference (H3) critically

acclaimed the transcript discussions of the respondents. Age group was an important factor in

importance of attractive participant (H6), and relation of importance of attractive participant with

enjoyment of reality TV shows (H5) was equally important (Lundy, Ruth & Park, 2008).

4.0 Discussion

The qualitative and quantitative data analysis was in line with each other. The qualitative

analysis revealed that the respondents were disturbed about the genuineness of the content of the

shows. The “attitude” towards the “authenticity” of the reality shows was addressed based on the

transcript description of the respondents. The consequences of the real life TV programs were

addressed in the second half of the qualitative analysis, where the respondents’ views on

negative impact of the shows on the society, especially on the children got reflected. The general

awareness about the ways and programs of entertainment in television was eminent from the

discussion in the transcript.

The quantitative analysis sustained the outcome of the qualitative scrutiny. Hypothesis

wise elaboration revealed that, significant relation was missing between enjoyments of TV

viewing and relating participants of the TV shows (H1). Significant gender difference was

observed in enjoyment from TV programs (H2), whereas, no relation was found between

delineation of real life in a reality show and enjoyment of the TV programs (H4). The

noteworthy relation between age groups and reality TV show preference (H3) critically

acclaimed the transcript discussions of the respondents. Age group was an important factor in

importance of attractive participant (H6), and relation of importance of attractive participant with

enjoyment of reality TV shows (H5) was equally important (Lundy, Ruth & Park, 2008).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 24

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.