Comprehensive Report on Negligence: Duty, Breach, and Law

VerifiedAdded on 2021/10/13

|19

|7201

|75

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive overview of the tort of negligence, starting with an introduction to tort law and its various interests, including protection of body, reputation, freedom, and property. It delves into the elements of negligence, which include establishing a duty of care owed by the defendant to the plaintiff, demonstrating a breach of that duty, and proving that the plaintiff suffered damage as a result of the defendant's actions. The report discusses the historical context of duty of care, referencing the landmark case of Donoghue v Stevenson and its impact on modern tort law. It further examines the concept of 'proximity' and the 'reasonable foreseeability of injury' test in determining duty of care. The document also addresses the breach of duty of care, emphasizing the standard of the 'reasonable person' and the considerations for engineers and other professionals. It touches upon the importance of insurance in spreading the burden of tortious liability and concludes by highlighting the inter-relationship between tort and contract, and tort and criminal law.

TOPIC 6

INTRODUCTION TO

NEGLIGENCE

INTRODUCTION TO

NEGLIGENCE

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Topic 6 Introduction to Negligence

TOPIC OUTCOMES

At the end of this topic you will be able to:

explain the meaning of ‘tort’;

explain the elements of negligence;

apply the elements of negligence to a practical problem;

explain the meaning of causation;

discuss possible defences to negligence;

explain vicarious liability;

explain the purpose of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (WA);

locate legal material; and

analyse and interpret legal information.

1. INTRODUCTION

Consider the following cases:

One day a factory was flooded after a heavy thunderstorm. Oil, which

normally ran in covered channels in the floor of the building, flowed over the

floor because of the storm. The day and afternoon shift workers spread 20

tons of sawdust over the floor to clean away the oil. One worker, who came on

duty with the nightshift, was unaware of the conditions and, while moving a

heavy barrel he slipped and crushed his ankle. Was the employer liable for the

employee’s injury? Had the employer done all that was reasonable to prevent

1 | P a g e

TOPIC OUTCOMES

At the end of this topic you will be able to:

explain the meaning of ‘tort’;

explain the elements of negligence;

apply the elements of negligence to a practical problem;

explain the meaning of causation;

discuss possible defences to negligence;

explain vicarious liability;

explain the purpose of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (WA);

locate legal material; and

analyse and interpret legal information.

1. INTRODUCTION

Consider the following cases:

One day a factory was flooded after a heavy thunderstorm. Oil, which

normally ran in covered channels in the floor of the building, flowed over the

floor because of the storm. The day and afternoon shift workers spread 20

tons of sawdust over the floor to clean away the oil. One worker, who came on

duty with the nightshift, was unaware of the conditions and, while moving a

heavy barrel he slipped and crushed his ankle. Was the employer liable for the

employee’s injury? Had the employer done all that was reasonable to prevent

1 | P a g e

Topic 6 Introduction to Negligence

an accident? What could the employer have done? Was the employer

negligent?

Contractors working on a building site blocked the usual approach to the

building on which they were working. People were advised to enter the

building through the adjoining property. One person fell through a hole on the

adjoining property while using the right of way at night. Was the contractor

liable for the person’s injury? Who should be liable? What would you have

done if you were the contractor?

The world in which we live and work is full of hazards and unexpected and

potential dangers. Workplaces of all kinds and descriptions are also potentially

hazardous places, and the possibility of accidents and injuries occurring are

not unexpected. However, if a person is injured or causes an injury or some

harm to another person, it does not mean to say that the person causing the

injury or harm should be held legally responsible for the harm caused, or that

the injured person will always succeeded in a claim.

In this topic we will consider the meaning and scope of the tort of negligence.

We will discuss the elements of negligence and possible defences. In the next

topic we will examine particular areas of duty, in particular professional

negligence and economic loss, in more detail.

2. TORT LAW

The word "tort" means "wrong". The word comes into English from the ancient

French word “tortus” which means “twisted, crooked or damaged”. A tort is a

wrongful act or omission which gives rise to a civil action against the

wrongdoer or tortfeasor. Excluded from this definition is any action for a

breach of contract. Essentially, tort law seeks to protect the rights. The law of

tort comprises many different torts which protect a variety of interests. These

interests include a person's:

(a) body ( the torts of negligence, assault and battery);

(b) reputation (the tort of defamation);

(c) freedom (the tort of false imprisonment);

(d) title to property (the torts of trespass to land and conversion);

(e) enjoyment of property (the tort of nuisance); and

(f) commercial interests (the torts of negligent misstatement and passing

off).

2 | P a g e

an accident? What could the employer have done? Was the employer

negligent?

Contractors working on a building site blocked the usual approach to the

building on which they were working. People were advised to enter the

building through the adjoining property. One person fell through a hole on the

adjoining property while using the right of way at night. Was the contractor

liable for the person’s injury? Who should be liable? What would you have

done if you were the contractor?

The world in which we live and work is full of hazards and unexpected and

potential dangers. Workplaces of all kinds and descriptions are also potentially

hazardous places, and the possibility of accidents and injuries occurring are

not unexpected. However, if a person is injured or causes an injury or some

harm to another person, it does not mean to say that the person causing the

injury or harm should be held legally responsible for the harm caused, or that

the injured person will always succeeded in a claim.

In this topic we will consider the meaning and scope of the tort of negligence.

We will discuss the elements of negligence and possible defences. In the next

topic we will examine particular areas of duty, in particular professional

negligence and economic loss, in more detail.

2. TORT LAW

The word "tort" means "wrong". The word comes into English from the ancient

French word “tortus” which means “twisted, crooked or damaged”. A tort is a

wrongful act or omission which gives rise to a civil action against the

wrongdoer or tortfeasor. Excluded from this definition is any action for a

breach of contract. Essentially, tort law seeks to protect the rights. The law of

tort comprises many different torts which protect a variety of interests. These

interests include a person's:

(a) body ( the torts of negligence, assault and battery);

(b) reputation (the tort of defamation);

(c) freedom (the tort of false imprisonment);

(d) title to property (the torts of trespass to land and conversion);

(e) enjoyment of property (the tort of nuisance); and

(f) commercial interests (the torts of negligent misstatement and passing

off).

2 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Topic 6 Introduction to Negligence

Despite their very different nature, most torts share common features, such

as:

Usually an element of fault is required, i.e. proof that the defendant acted

intentionally or negligently. (Exceptions are certain torts of strict liability

where a defendant is liable regardless of any personal fault.)

Most torts require that actual damage or injury be suffered by the

plaintiff. Exceptions to this are the torts of defamation (libel), trespass to

land and nuisance.

In most actions in tort, the remedy sought is damages i.e. monetary

compensation. Since the law of torts is concerned with compensating the

victim rather than with punishing the wrongdoer, the general rule is that

the plaintiff should be put in the position which he enjoyed before the

commission of the tort. Other remedies available for some specific torts

are injunction, abatement (or self-help), and restitution of property.

The defendant may raise specific defences in tortious actions. For

example, in negligence actions the recognized defences are contributory

negligence and voluntary assumption of risk.

A person may be held liable for the tort of another in certain

circumstances. This is known as vicarious (or indirect) liability.

Today, insurance spreads the burden of tortious liability. For example, there is

an insurance component in motor vehicle registration fees. Consequently it is

an insurance company, rather than a defendant driver, which will pay

damages to a plaintiff injured in a motor vehicle accident.

There is significant inter-relationship between tort and contract, and tort and

criminal law. All are distinct areas of the law, however on occasion a plaintiff

can pursue more than one form of action.

3. THE TORT OF NEGLIGENCE

Negligence is a tort that determines legal liability for careless actions or

inactions which cause injury or damage. Negligence may be defined as the

failure to do something that a reasonable person would do, or doing

something that a reasonable person would not do, as a result of which another

person suffers damage. The damage may be personal injury (for example, a

broken leg) or damage to property (for example, a damaged car) or monetary

loss (for example, the plaintiff has lost money which was invested).

In order to establish the liability of the defendant in negligence, the plaintiff

must prove each of the following (Gibson & Fraser, 2007):

3 | P a g e

Despite their very different nature, most torts share common features, such

as:

Usually an element of fault is required, i.e. proof that the defendant acted

intentionally or negligently. (Exceptions are certain torts of strict liability

where a defendant is liable regardless of any personal fault.)

Most torts require that actual damage or injury be suffered by the

plaintiff. Exceptions to this are the torts of defamation (libel), trespass to

land and nuisance.

In most actions in tort, the remedy sought is damages i.e. monetary

compensation. Since the law of torts is concerned with compensating the

victim rather than with punishing the wrongdoer, the general rule is that

the plaintiff should be put in the position which he enjoyed before the

commission of the tort. Other remedies available for some specific torts

are injunction, abatement (or self-help), and restitution of property.

The defendant may raise specific defences in tortious actions. For

example, in negligence actions the recognized defences are contributory

negligence and voluntary assumption of risk.

A person may be held liable for the tort of another in certain

circumstances. This is known as vicarious (or indirect) liability.

Today, insurance spreads the burden of tortious liability. For example, there is

an insurance component in motor vehicle registration fees. Consequently it is

an insurance company, rather than a defendant driver, which will pay

damages to a plaintiff injured in a motor vehicle accident.

There is significant inter-relationship between tort and contract, and tort and

criminal law. All are distinct areas of the law, however on occasion a plaintiff

can pursue more than one form of action.

3. THE TORT OF NEGLIGENCE

Negligence is a tort that determines legal liability for careless actions or

inactions which cause injury or damage. Negligence may be defined as the

failure to do something that a reasonable person would do, or doing

something that a reasonable person would not do, as a result of which another

person suffers damage. The damage may be personal injury (for example, a

broken leg) or damage to property (for example, a damaged car) or monetary

loss (for example, the plaintiff has lost money which was invested).

In order to establish the liability of the defendant in negligence, the plaintiff

must prove each of the following (Gibson & Fraser, 2007):

3 | P a g e

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Topic 6 Introduction to Negligence

that a duty of care was owed by the defendant to the plaintiff;

that the defendant breached the duty of care by failing to conform to the

required standard of care; and

that there has been damage to the plaintiff caused by the defendant

which was a reasonably foreseeable consequence of the defendant's

conduct.

A. DUTY OF CARE

The plaintiff must prove the existence of circumstances which establish a duty

of care (a duty to be careful) (Gibson & Fraser, 2007). This is a question of law

and must be determined by a judge.

Historically a duty of care would arise only in certain limited categories of

recognised relationships, such as common innkeepers, common carriers,

blacksmiths, and surgeons. In other words a surgeon (the defendant) would

owe a duty of care to the patient (the plaintiff). Later, during the eighteenth

and nineteenth centuries, there was recognition by the courts that a duty of

care could also arise in situations where there was no pre-existing relationship

between the parties. These new situations included collision cases (where a

road user was injured by the negligence of another road user).

Even so, until the case of Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 those duty of

care situations remained limited to specific circumstances. In that case the

House of Lords formulated the duty of care in terms of a general principle,

rather than the restrictive “categories” approach that had previously existed.

In Donoghue v Stevenson Lord Atkin spoke of the duty of care being owed to

one’s “neighbour”.

Two elements are contained in Lord Atkin's formulation of when a duty of care

is owed:

(a) the duty is owed to a person who is likely to be “closely and directly

affected” by one's actions: this is the concept of “proximity”; and

(b) the nature of the duty is to avoid acts or omissions which one can

“reasonably foresee” are likely to cause injury to another: this is known

as the “reasonable foreseeability of injury” test.

The decision in Donoghue v Stevenson, and in particular the judgment of Lord

Atkin, is perhaps the single most important decision in the history of the

modern tort of negligence. It has been widely accepted and applied in every

common law country, including in Australian courts all the way up to and

4 | P a g e

that a duty of care was owed by the defendant to the plaintiff;

that the defendant breached the duty of care by failing to conform to the

required standard of care; and

that there has been damage to the plaintiff caused by the defendant

which was a reasonably foreseeable consequence of the defendant's

conduct.

A. DUTY OF CARE

The plaintiff must prove the existence of circumstances which establish a duty

of care (a duty to be careful) (Gibson & Fraser, 2007). This is a question of law

and must be determined by a judge.

Historically a duty of care would arise only in certain limited categories of

recognised relationships, such as common innkeepers, common carriers,

blacksmiths, and surgeons. In other words a surgeon (the defendant) would

owe a duty of care to the patient (the plaintiff). Later, during the eighteenth

and nineteenth centuries, there was recognition by the courts that a duty of

care could also arise in situations where there was no pre-existing relationship

between the parties. These new situations included collision cases (where a

road user was injured by the negligence of another road user).

Even so, until the case of Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 those duty of

care situations remained limited to specific circumstances. In that case the

House of Lords formulated the duty of care in terms of a general principle,

rather than the restrictive “categories” approach that had previously existed.

In Donoghue v Stevenson Lord Atkin spoke of the duty of care being owed to

one’s “neighbour”.

Two elements are contained in Lord Atkin's formulation of when a duty of care

is owed:

(a) the duty is owed to a person who is likely to be “closely and directly

affected” by one's actions: this is the concept of “proximity”; and

(b) the nature of the duty is to avoid acts or omissions which one can

“reasonably foresee” are likely to cause injury to another: this is known

as the “reasonable foreseeability of injury” test.

The decision in Donoghue v Stevenson, and in particular the judgment of Lord

Atkin, is perhaps the single most important decision in the history of the

modern tort of negligence. It has been widely accepted and applied in every

common law country, including in Australian courts all the way up to and

4 | P a g e

Topic 6 Introduction to Negligence

including the High Court although in modern times modification to the

principle has occurred.

To summarise: in order to establish the existence of a duty of care, the

plaintiff must establish either that:

1. the plaintiff and defendant belong to one of the recognised categories of

relationship such as manufacturers, authorities, builders and occupiers of

premises ; or,

2. In circumstances that are ‘novel’ the following factors are taken into

consideration;

Consideration of risk of injury to the plaintiff that was a “reasonably

foreseeable” consequence of the defendant's conduct, the defendant’s

relationship to such a risk, the nature of damage suffered by the plaintiff

and their vulnerability among other ‘salient’ features.’

3. The absence of public policy or rules that would prevent a duty being

imposed.

Historically, a requirement for a sufficient relationship of “proximity” or

closeness between the plaintiff and the defendant was required. Often there is

an existing relationship between defendant and plaintiff category. Note also

that Gleeson CJ remarked in Modbury Triangle Shopping Centre Pty Ltd v Anzil

(2000) 205 CLR 254 that most actions in tort arise out of relationships in which

the existence of a duty of care is well established and the nature of the duty is

well understood’. This case concerned a claim against an occupier that had

turned off lights in a carpark. The plaintiff had been assaulted by three men

and claimed the occupier was negligent. The High Court disagreed and found

that the occupier not responsible due to a lack of control over the assailants’

actions.

It should be noted that in recent years, however, the High Court of Australia

has diluted the absolute need for proximity or closeness in establishing a duty

of care although it may still be considered a salient feature. See for example

Jones v Bartlett (2000) 205 CLR 166 in which architectural glass failed at a

home (it had been found safe at the time of construction) and caused injury to

a tenant’s relative. This was determined by the court not to be negligence to

take reasonable care on the part of a landlord. Salient features were outlined

by the court in Caltex Refineries (Qld) Pty Ltd v Stavar [2009] NSWCA 258

which concerned the negligence claim by the wife of a former refinery worker

who contracted asbestos related disease following exposure to her husband’s

work clothing.

5 | P a g e

including the High Court although in modern times modification to the

principle has occurred.

To summarise: in order to establish the existence of a duty of care, the

plaintiff must establish either that:

1. the plaintiff and defendant belong to one of the recognised categories of

relationship such as manufacturers, authorities, builders and occupiers of

premises ; or,

2. In circumstances that are ‘novel’ the following factors are taken into

consideration;

Consideration of risk of injury to the plaintiff that was a “reasonably

foreseeable” consequence of the defendant's conduct, the defendant’s

relationship to such a risk, the nature of damage suffered by the plaintiff

and their vulnerability among other ‘salient’ features.’

3. The absence of public policy or rules that would prevent a duty being

imposed.

Historically, a requirement for a sufficient relationship of “proximity” or

closeness between the plaintiff and the defendant was required. Often there is

an existing relationship between defendant and plaintiff category. Note also

that Gleeson CJ remarked in Modbury Triangle Shopping Centre Pty Ltd v Anzil

(2000) 205 CLR 254 that most actions in tort arise out of relationships in which

the existence of a duty of care is well established and the nature of the duty is

well understood’. This case concerned a claim against an occupier that had

turned off lights in a carpark. The plaintiff had been assaulted by three men

and claimed the occupier was negligent. The High Court disagreed and found

that the occupier not responsible due to a lack of control over the assailants’

actions.

It should be noted that in recent years, however, the High Court of Australia

has diluted the absolute need for proximity or closeness in establishing a duty

of care although it may still be considered a salient feature. See for example

Jones v Bartlett (2000) 205 CLR 166 in which architectural glass failed at a

home (it had been found safe at the time of construction) and caused injury to

a tenant’s relative. This was determined by the court not to be negligence to

take reasonable care on the part of a landlord. Salient features were outlined

by the court in Caltex Refineries (Qld) Pty Ltd v Stavar [2009] NSWCA 258

which concerned the negligence claim by the wife of a former refinery worker

who contracted asbestos related disease following exposure to her husband’s

work clothing.

5 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Topic 6 Introduction to Negligence

B. BREACH OF DUTY OF CARE

Once the existence of a duty of care is established, the court will ascertain

whether the defendant breached that duty by falling below the required

standard of care (Gibson & Fraser, 2007). This necessitates an examination of

the defendant's conduct and a finding of whether or not they observed an

appropriate standard of care in the circumstances. In other words, was the

defendant careful enough? The standard of care is objective and the standard

required is that of the “reasonable person”. The reasonable person is

someone of normal intelligence. In determining whether a person breached

the standard of care, the court considers whether the risk or injury to the

plaintiff was reasonably foreseeable, and the reasonableness of the

defendant’s response to the risk. In so far as engineers are concerned, like

other professionals the standard measured against in a negligence dispute is

the ‘standard of the competent practitioner’ and on occasion will require the

engineer to review and revise previous decisions in light of developments

during a project. These would include circumstances such as where

information was unavailable or overlooked initially and continues at least until

practical completion (Cooke 2010:68-69). An example of the professional

standard applied to engineers can be found in Eckersley v Binnie & Partners

(1988) 18 Con LR 1 where the Court of Appeal suggested that the appropriate

standard to be applied to the defendant engineers was analogous to

competent engineers that specialise in water transfer systems.

Also, an engineer or architect for example may be liable in negligence for a

design that does not achieve desired results such as was the case in

Consultants Group International v John Worman Ltd (1987) 9 Con LR 46 where

plaintiff architects were found liable for a faulty design of an abattoir which

was considered to be unfit for purpose.

The amount and kind of care required varies from case to case. All the facts

that would influence the conduct of a “reasonable person” in those particular

circumstances will be taken into account. One of the issues that a reasonable

person would take into account is the seriousness of the consequences should

any of the risks inherent in the conduct eventuate. In Paris v Stepney Borough

Council [1951] AC 367 the plaintiff, Paris, had only one eye. The defendant

Council employed him as a motor mechanic. The Council was aware of his

disability but did not provide protective goggles when the plaintiff was using a

steel hammer to loosen a rusty bolt. A metal chip flew into his good eye

resulting in him becoming blind. The court held that the Council was negligent

in not providing goggles and, in doing so, said that although the risk of injury

to Paris was no greater than to any other person employed as a mechanic, the

seriousness of the consequences of that injury to Paris was much greater than

to a person who had sight in both eyes, therefore the standard of care owed to

Paris was greater.

6 | P a g e

B. BREACH OF DUTY OF CARE

Once the existence of a duty of care is established, the court will ascertain

whether the defendant breached that duty by falling below the required

standard of care (Gibson & Fraser, 2007). This necessitates an examination of

the defendant's conduct and a finding of whether or not they observed an

appropriate standard of care in the circumstances. In other words, was the

defendant careful enough? The standard of care is objective and the standard

required is that of the “reasonable person”. The reasonable person is

someone of normal intelligence. In determining whether a person breached

the standard of care, the court considers whether the risk or injury to the

plaintiff was reasonably foreseeable, and the reasonableness of the

defendant’s response to the risk. In so far as engineers are concerned, like

other professionals the standard measured against in a negligence dispute is

the ‘standard of the competent practitioner’ and on occasion will require the

engineer to review and revise previous decisions in light of developments

during a project. These would include circumstances such as where

information was unavailable or overlooked initially and continues at least until

practical completion (Cooke 2010:68-69). An example of the professional

standard applied to engineers can be found in Eckersley v Binnie & Partners

(1988) 18 Con LR 1 where the Court of Appeal suggested that the appropriate

standard to be applied to the defendant engineers was analogous to

competent engineers that specialise in water transfer systems.

Also, an engineer or architect for example may be liable in negligence for a

design that does not achieve desired results such as was the case in

Consultants Group International v John Worman Ltd (1987) 9 Con LR 46 where

plaintiff architects were found liable for a faulty design of an abattoir which

was considered to be unfit for purpose.

The amount and kind of care required varies from case to case. All the facts

that would influence the conduct of a “reasonable person” in those particular

circumstances will be taken into account. One of the issues that a reasonable

person would take into account is the seriousness of the consequences should

any of the risks inherent in the conduct eventuate. In Paris v Stepney Borough

Council [1951] AC 367 the plaintiff, Paris, had only one eye. The defendant

Council employed him as a motor mechanic. The Council was aware of his

disability but did not provide protective goggles when the plaintiff was using a

steel hammer to loosen a rusty bolt. A metal chip flew into his good eye

resulting in him becoming blind. The court held that the Council was negligent

in not providing goggles and, in doing so, said that although the risk of injury

to Paris was no greater than to any other person employed as a mechanic, the

seriousness of the consequences of that injury to Paris was much greater than

to a person who had sight in both eyes, therefore the standard of care owed to

Paris was greater.

6 | P a g e

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Topic 6 Introduction to Negligence

Another issue to consider is the degree of risk. In Bolton v Stone [1951] AC

850 a woman was hit by a cricket ball as she stood in front of her house. The

ball came from a cricket ground across the road which was surrounded by a

17 foot high fence. Evidence described how it would take an exceptional hit to

clear the perimeter fence and that over the past 30 years very few balls had

ever been hit that far. The court held that the risk was so small that a

reasonable person would not think of taking any further precautions than

building a high fence.

Reasonableness of precaution against likelihood of injury is also a factor in

assessing the standard of care. In Haley v London Electrical Board [1964] 3 All

ER 185 a blind man fell into a trench. While there was a visual warning sign

the House of Lords held that a barrier should have been erected as it was

foreseeable that a blind person could be walking along the path so the

electrical company should have taken precautions against it.

Dangerous activities are also an issue to be considered by courts in assessing

the appropriate standard of care. For example, in Dominion Natural Gas Co Ltd

v Collins and Perkins [1909] AC 640 Perkins was killed and Collins injured

when a safety valve that discharged gas into the inside of a building instead of

the outside caused an explosion. In determining that the company was liable

in negligence, the court held that a greater standard of care ought to have

been provided due to the inherent danger associated with venting excess gas

inside a building.

Note also that there is now legislation in most states and territories relating to

how the courts must assess standard of care. In Western Australia, for

example, in the Civil Liability Act 2002 (WA) the provision talks of a risk that is

“not insignificant” (see below).

C. DAMAGE

The plaintiff must prove that he has suffered actual damage due to the

defendant's conduct (Gibson & Fraser, 2007). This may be in the form of

personal injury, injury to property or monetary loss. There are two aspects to

the concept of damage: causation of the injury; and a plaintiff may only

recover for damage of a reasonably foreseeable kind.

Causation

There must be a direct connection (or “causal nexus”) between the

defendant's conduct and the damage suffered. In other words, the defendant's

conduct must have caused the damage. Causation is a difficult issue, as

damage may be caused by a number of factors.

7 | P a g e

Another issue to consider is the degree of risk. In Bolton v Stone [1951] AC

850 a woman was hit by a cricket ball as she stood in front of her house. The

ball came from a cricket ground across the road which was surrounded by a

17 foot high fence. Evidence described how it would take an exceptional hit to

clear the perimeter fence and that over the past 30 years very few balls had

ever been hit that far. The court held that the risk was so small that a

reasonable person would not think of taking any further precautions than

building a high fence.

Reasonableness of precaution against likelihood of injury is also a factor in

assessing the standard of care. In Haley v London Electrical Board [1964] 3 All

ER 185 a blind man fell into a trench. While there was a visual warning sign

the House of Lords held that a barrier should have been erected as it was

foreseeable that a blind person could be walking along the path so the

electrical company should have taken precautions against it.

Dangerous activities are also an issue to be considered by courts in assessing

the appropriate standard of care. For example, in Dominion Natural Gas Co Ltd

v Collins and Perkins [1909] AC 640 Perkins was killed and Collins injured

when a safety valve that discharged gas into the inside of a building instead of

the outside caused an explosion. In determining that the company was liable

in negligence, the court held that a greater standard of care ought to have

been provided due to the inherent danger associated with venting excess gas

inside a building.

Note also that there is now legislation in most states and territories relating to

how the courts must assess standard of care. In Western Australia, for

example, in the Civil Liability Act 2002 (WA) the provision talks of a risk that is

“not insignificant” (see below).

C. DAMAGE

The plaintiff must prove that he has suffered actual damage due to the

defendant's conduct (Gibson & Fraser, 2007). This may be in the form of

personal injury, injury to property or monetary loss. There are two aspects to

the concept of damage: causation of the injury; and a plaintiff may only

recover for damage of a reasonably foreseeable kind.

Causation

There must be a direct connection (or “causal nexus”) between the

defendant's conduct and the damage suffered. In other words, the defendant's

conduct must have caused the damage. Causation is a difficult issue, as

damage may be caused by a number of factors.

7 | P a g e

Topic 6 Introduction to Negligence

To assist in determining the cause of the injury the “but for” test may be used.

This test was discussed in Cork v Kirby MacLean Ltd [1952] 2 All ER 402 where

the court said that the causal link was established if it was possible to say “but

for” the breach of duty of the defendant, the plaintiff would not have suffered

the injury. In this case a worker who suffered from epileptic fits was forbidden

by his doctor to work at any heights. He did not disclose the information to his

employer as he feared he would not get the job. When working from a

platform some six metres off the ground he fell to his death while

experiencing an epileptic fit. The platform he was working from did not meet

statutory safety regulations and his employer was in breach of statutory

duties. In deciding what was the cause of death the court decided that both

the employer and employee were at fault. Causation therefore is a question of

fact. If you can say that damage would not have happened “but-for” a

particular fault, then that fault is the cause of the damage. But if you can say

that the damage would have occurred anyway then the fault is not a cause of

the damage.

In Yates v Jones (1990) ATR 81, a young woman was injured in a road accident

by a drunk driver. She was offered heroin as a pain killer by a visitor and

subsequently became addicted and spent copious amounts on the drug. At

first she was successful in an action for personal injury against the drunk

driver which included an amount of compensation for the heroin addiction.

The decision to award damages for the heroin addiction was however reversed

on appeal as no causal link could be established between the driver’s

negligence and her heroin addiction. The other general damages award for

personal injury remained.

Increasingly, the High Court has expressed the view that the “but for” test

must be applied and interpreted along with “common sense.” This view was

expressed in March v E & MH Stramare Pty Ltd (1990) 171 CLR 506. In this

case a man parked a large truck in the middle of a six lane road in the early

hours of the morning to unload the goods inside. The road was well lit and the

hazard lights as well as the truck’s regular driving lights were on. The drunken

plaintiff drove out from a pub car park and collided with the truck. The plaintiff

sustained injury and sued the Defendant truck driver. The High court had to

establish who had caused the harm. It was held that both plaintiff and

defendant had caused the damage and it was apportioned 70% plaintiff due to

his drunkenness and 30% to the defendant truck driver.

The recent case Amaca Pty Ltd v Ellis [2010] HCA 5 also illustrates this notion

as the High Court determined that there was a greater likelihood that

cigarette smoking for over 25 years was more than likely the cause of a

workers death rather than exposure to asbestos fibres in the workplace over

the same time.

Only reasonably foreseeable damage is recoverable

8 | P a g e

To assist in determining the cause of the injury the “but for” test may be used.

This test was discussed in Cork v Kirby MacLean Ltd [1952] 2 All ER 402 where

the court said that the causal link was established if it was possible to say “but

for” the breach of duty of the defendant, the plaintiff would not have suffered

the injury. In this case a worker who suffered from epileptic fits was forbidden

by his doctor to work at any heights. He did not disclose the information to his

employer as he feared he would not get the job. When working from a

platform some six metres off the ground he fell to his death while

experiencing an epileptic fit. The platform he was working from did not meet

statutory safety regulations and his employer was in breach of statutory

duties. In deciding what was the cause of death the court decided that both

the employer and employee were at fault. Causation therefore is a question of

fact. If you can say that damage would not have happened “but-for” a

particular fault, then that fault is the cause of the damage. But if you can say

that the damage would have occurred anyway then the fault is not a cause of

the damage.

In Yates v Jones (1990) ATR 81, a young woman was injured in a road accident

by a drunk driver. She was offered heroin as a pain killer by a visitor and

subsequently became addicted and spent copious amounts on the drug. At

first she was successful in an action for personal injury against the drunk

driver which included an amount of compensation for the heroin addiction.

The decision to award damages for the heroin addiction was however reversed

on appeal as no causal link could be established between the driver’s

negligence and her heroin addiction. The other general damages award for

personal injury remained.

Increasingly, the High Court has expressed the view that the “but for” test

must be applied and interpreted along with “common sense.” This view was

expressed in March v E & MH Stramare Pty Ltd (1990) 171 CLR 506. In this

case a man parked a large truck in the middle of a six lane road in the early

hours of the morning to unload the goods inside. The road was well lit and the

hazard lights as well as the truck’s regular driving lights were on. The drunken

plaintiff drove out from a pub car park and collided with the truck. The plaintiff

sustained injury and sued the Defendant truck driver. The High court had to

establish who had caused the harm. It was held that both plaintiff and

defendant had caused the damage and it was apportioned 70% plaintiff due to

his drunkenness and 30% to the defendant truck driver.

The recent case Amaca Pty Ltd v Ellis [2010] HCA 5 also illustrates this notion

as the High Court determined that there was a greater likelihood that

cigarette smoking for over 25 years was more than likely the cause of a

workers death rather than exposure to asbestos fibres in the workplace over

the same time.

Only reasonably foreseeable damage is recoverable

8 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Topic 6 Introduction to Negligence

The defendant will not be liable for all the damage caused by their breach of

duty. The Privy Council established in Wagon Mound (No.1) [1961] AC 388 that

a defendant will be liable only for that damage which is reasonably

foreseeable as a result of the defendant's conduct. The plaintiff shipbuilders

and engineers owned a wharf in Sydney Harbour. The defendant had

chartered a ship anchored about 200 metres away. Because of the defendants

carelessness oil had spilled onto the surface of the harbour. Sparks from the

plaintiff’s welding ignited the oil and caused a fire on the wharf which spread

to a number of ships anchored at the wharf. The plaintiff was unsuccessful in

proving negligence against the defendant as it was considered that no

reasonable person could have foreseen the type of fire damage that

eventuated. However in the Wagon Mound (No.2) [1967] AC 617 the Privy

Council again examined the concept of "reasonably foreseeable damage", and

held that a particular type of damage will be reasonably foreseeable if the risk

of it is "real", and not "far-fetched". The oil spill had given rise to a second

case with a different plaintiff-the owner of a ship that was moored at the wharf

and was also damaged during the fire. The court this time considered that the

damage was foreseeable and so the plaintiff was successful in the second

case.

9 | P a g e

The defendant will not be liable for all the damage caused by their breach of

duty. The Privy Council established in Wagon Mound (No.1) [1961] AC 388 that

a defendant will be liable only for that damage which is reasonably

foreseeable as a result of the defendant's conduct. The plaintiff shipbuilders

and engineers owned a wharf in Sydney Harbour. The defendant had

chartered a ship anchored about 200 metres away. Because of the defendants

carelessness oil had spilled onto the surface of the harbour. Sparks from the

plaintiff’s welding ignited the oil and caused a fire on the wharf which spread

to a number of ships anchored at the wharf. The plaintiff was unsuccessful in

proving negligence against the defendant as it was considered that no

reasonable person could have foreseen the type of fire damage that

eventuated. However in the Wagon Mound (No.2) [1967] AC 617 the Privy

Council again examined the concept of "reasonably foreseeable damage", and

held that a particular type of damage will be reasonably foreseeable if the risk

of it is "real", and not "far-fetched". The oil spill had given rise to a second

case with a different plaintiff-the owner of a ship that was moored at the wharf

and was also damaged during the fire. The court this time considered that the

damage was foreseeable and so the plaintiff was successful in the second

case.

9 | P a g e

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Topic 6 Introduction to Negligence

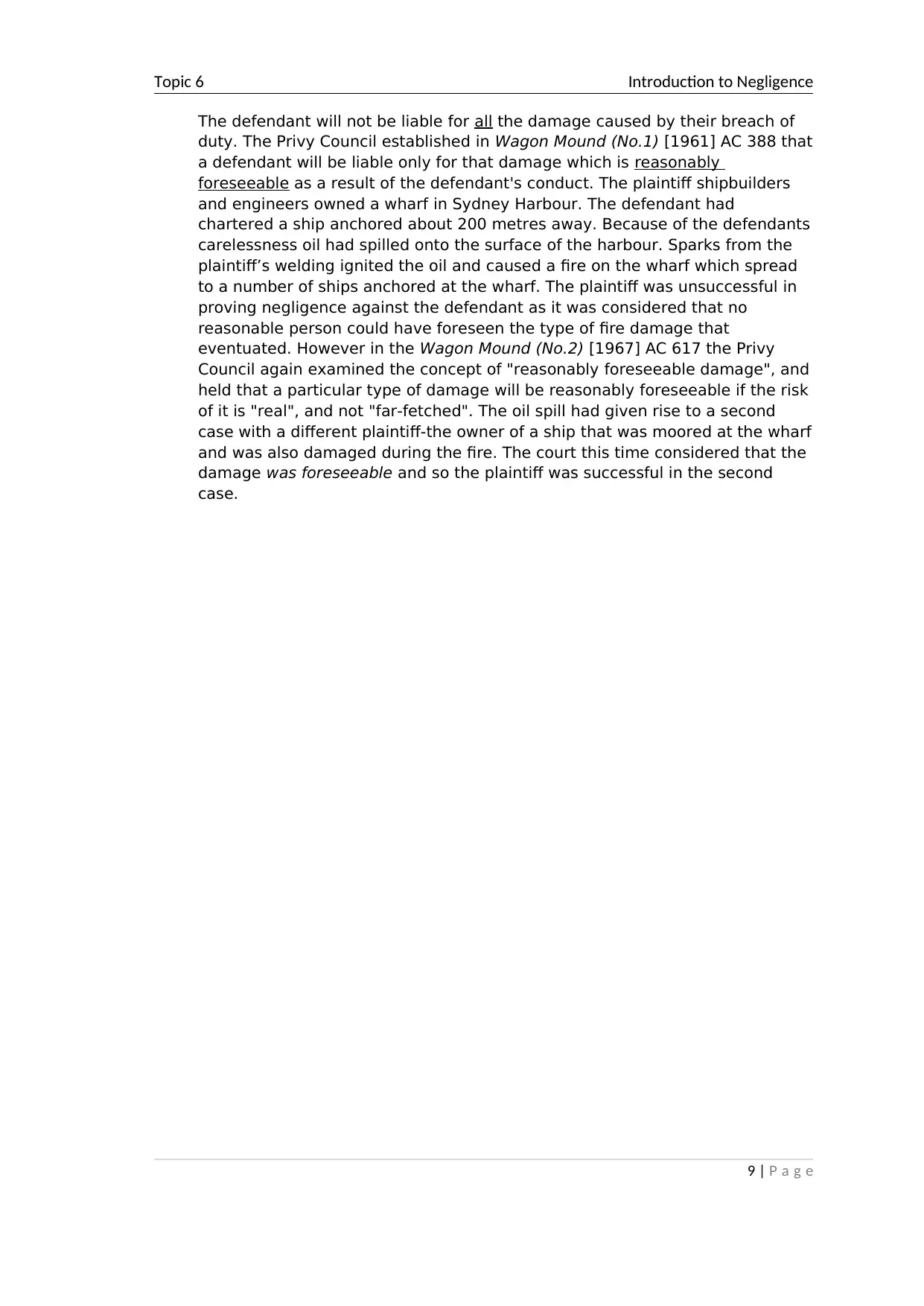

Elements of an action in negligence

Note: each element is a device to limit the liability of the defendant.

4. DEFENCES

There are two defences which a defendant may raise against a claim in

negligence (Gibson & Fraser, 2007):

(a) Voluntary assumption of risk, and

(b) Contributory negligence.

A. VOLUNTARY ASSUMPTION OF RISK (CONSENT)

10 | P a g e

Elements of an action in negligence

Note: each element is a device to limit the liability of the defendant.

4. DEFENCES

There are two defences which a defendant may raise against a claim in

negligence (Gibson & Fraser, 2007):

(a) Voluntary assumption of risk, and

(b) Contributory negligence.

A. VOLUNTARY ASSUMPTION OF RISK (CONSENT)

10 | P a g e

Topic 6 Introduction to Negligence

This defence is VERY rarely successful. There have been no more than a

handful of cases where the defence was raised successfully in the past 15

years in Australia.

Where a plaintiff has fully and freely consented to the risk of harm caused by

the defendant's conduct, the defendant may be relieved of legal liability for

that conduct. Such consent on the part of the plaintiff is termed voluntary

assumption of risk.

Thus, for example, a person who plays a contact sport, such as Australian

Rules football or rugby, may be held to have voluntarily assumed the risk of

accidental physical injury which they sustain in the ordinary course of the

game. (Note that the risks consented to are only those inherent in the game:

the participant does not consent to other negligent conduct on the part of the

other players.)

Case Study: Voluntary assumption of risk

Morris v Murray [1990] 3 All ER 801

The plaintiff had been out on a “pub-crawl”. At his second pub, the plaintiff

joined the defendant, who was the owner of a light aircraft, and others and

continued drinking. The plaintiff took the defendant and another person to the

aerodrome in his car, and all three boarded the aircraft for a “joyride”. Flying

had been suspended due to bad weather, and the defendant pilot, who had

consumed 17 whiskeys, attempted a particularly difficult take-off. Shortly after

take-off the aircraft crashed, killing the defendant pilot.

The court held that the plaintiff, although drunk himself, was aware of the

intoxication of the pilot and understood the risk he was taking in flying with

the deceased in poor weather. As such, the plaintiff was not entitled to any

compensation for his injuries.

In Insurance Commissioner v Joyce (1948) 77 CLR 39, the plaintiff was a

passenger in a car that was involved in an accident and suffered injuries. The

defendant driver was drunk. The court held that the plaintiff was not entitled

to any compensation as they had voluntarily accepted a lift with a drunk

driver and therefore had voluntarily assumed the risk that the driver would

drive negligently. Likewise in Imperial Chemical Industries Ltd v Shatwell

[1965] AC 565 a shotblaster at a quarry was permanently injured when testing

electrical circuitry. New regulations and employer instructions required this to

be done from a shelter but both were ignored. The court held that the plaintiff

11 | P a g e

This defence is VERY rarely successful. There have been no more than a

handful of cases where the defence was raised successfully in the past 15

years in Australia.

Where a plaintiff has fully and freely consented to the risk of harm caused by

the defendant's conduct, the defendant may be relieved of legal liability for

that conduct. Such consent on the part of the plaintiff is termed voluntary

assumption of risk.

Thus, for example, a person who plays a contact sport, such as Australian

Rules football or rugby, may be held to have voluntarily assumed the risk of

accidental physical injury which they sustain in the ordinary course of the

game. (Note that the risks consented to are only those inherent in the game:

the participant does not consent to other negligent conduct on the part of the

other players.)

Case Study: Voluntary assumption of risk

Morris v Murray [1990] 3 All ER 801

The plaintiff had been out on a “pub-crawl”. At his second pub, the plaintiff

joined the defendant, who was the owner of a light aircraft, and others and

continued drinking. The plaintiff took the defendant and another person to the

aerodrome in his car, and all three boarded the aircraft for a “joyride”. Flying

had been suspended due to bad weather, and the defendant pilot, who had

consumed 17 whiskeys, attempted a particularly difficult take-off. Shortly after

take-off the aircraft crashed, killing the defendant pilot.

The court held that the plaintiff, although drunk himself, was aware of the

intoxication of the pilot and understood the risk he was taking in flying with

the deceased in poor weather. As such, the plaintiff was not entitled to any

compensation for his injuries.

In Insurance Commissioner v Joyce (1948) 77 CLR 39, the plaintiff was a

passenger in a car that was involved in an accident and suffered injuries. The

defendant driver was drunk. The court held that the plaintiff was not entitled

to any compensation as they had voluntarily accepted a lift with a drunk

driver and therefore had voluntarily assumed the risk that the driver would

drive negligently. Likewise in Imperial Chemical Industries Ltd v Shatwell

[1965] AC 565 a shotblaster at a quarry was permanently injured when testing

electrical circuitry. New regulations and employer instructions required this to

be done from a shelter but both were ignored. The court held that the plaintiff

11 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 19

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.