Netflix Case Study: Analyzing Customer Behavior and Market Trends

VerifiedAdded on 2019/09/26

|6

|2466

|338

Case Study

AI Summary

This case study examines Netflix's evolution in the video rental industry, starting with its DVD-by-mail service and its transition to video streaming. It explores the impact of technological advancements on the industry, including the rise of kiosks and video-on-demand services. The case analyzes Netflix's customer-centric strategies, such as eliminating late fees and implementing a movie recommendation system to enhance customer retention. It discusses the importance of customer lifetime value (CLV) and how Netflix leveraged data mining technology to understand customer preferences and expand its customer base. The case also highlights the challenges Netflix faced, including the split of its services and subsequent loss of subscribers, and the importance of adapting to market changes to maintain its competitive edge.

1 Netflix: The Customer Strikes Back

Introduction

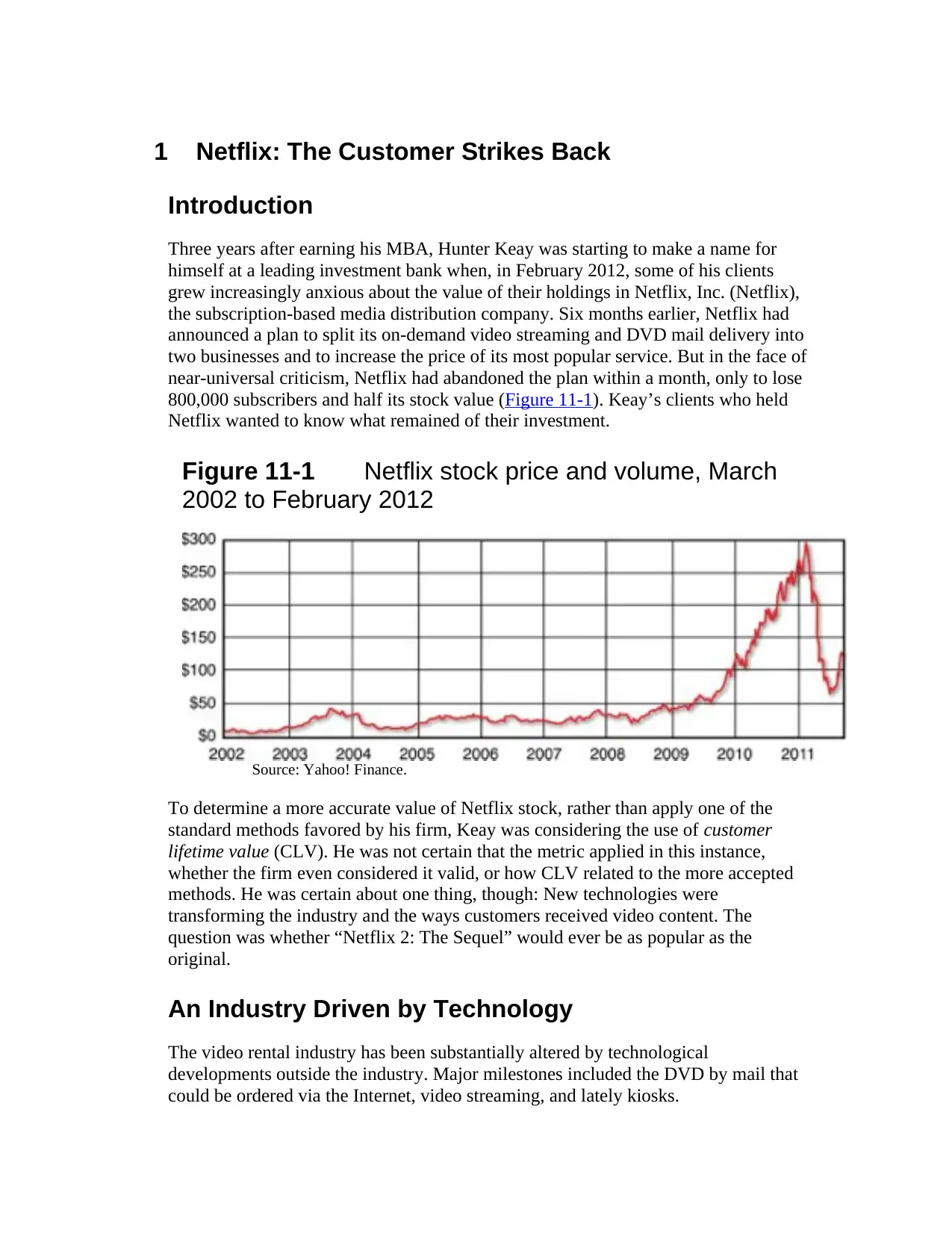

Three years after earning his MBA, Hunter Keay was starting to make a name for

himself at a leading investment bank when, in February 2012, some of his clients

grew increasingly anxious about the value of their holdings in Netflix, Inc. (Netflix),

the subscription-based media distribution company. Six months earlier, Netflix had

announced a plan to split its on-demand video streaming and DVD mail delivery into

two businesses and to increase the price of its most popular service. But in the face of

near-universal criticism, Netflix had abandoned the plan within a month, only to lose

800,000 subscribers and half its stock value (Figure 11-1). Keay’s clients who held

Netflix wanted to know what remained of their investment.

Figure 11-1 Netflix stock price and volume, March

2002 to February 2012

Source: Yahoo! Finance.

To determine a more accurate value of Netflix stock, rather than apply one of the

standard methods favored by his firm, Keay was considering the use of customer

lifetime value (CLV). He was not certain that the metric applied in this instance,

whether the firm even considered it valid, or how CLV related to the more accepted

methods. He was certain about one thing, though: New technologies were

transforming the industry and the ways customers received video content. The

question was whether “Netflix 2: The Sequel” would ever be as popular as the

original.

An Industry Driven by Technology

The video rental industry has been substantially altered by technological

developments outside the industry. Major milestones included the DVD by mail that

could be ordered via the Internet, video streaming, and lately kiosks.

Introduction

Three years after earning his MBA, Hunter Keay was starting to make a name for

himself at a leading investment bank when, in February 2012, some of his clients

grew increasingly anxious about the value of their holdings in Netflix, Inc. (Netflix),

the subscription-based media distribution company. Six months earlier, Netflix had

announced a plan to split its on-demand video streaming and DVD mail delivery into

two businesses and to increase the price of its most popular service. But in the face of

near-universal criticism, Netflix had abandoned the plan within a month, only to lose

800,000 subscribers and half its stock value (Figure 11-1). Keay’s clients who held

Netflix wanted to know what remained of their investment.

Figure 11-1 Netflix stock price and volume, March

2002 to February 2012

Source: Yahoo! Finance.

To determine a more accurate value of Netflix stock, rather than apply one of the

standard methods favored by his firm, Keay was considering the use of customer

lifetime value (CLV). He was not certain that the metric applied in this instance,

whether the firm even considered it valid, or how CLV related to the more accepted

methods. He was certain about one thing, though: New technologies were

transforming the industry and the ways customers received video content. The

question was whether “Netflix 2: The Sequel” would ever be as popular as the

original.

An Industry Driven by Technology

The video rental industry has been substantially altered by technological

developments outside the industry. Major milestones included the DVD by mail that

could be ordered via the Internet, video streaming, and lately kiosks.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The Traditional Retail Rental Store

The advent of videotape, acceptance of the VHS cassette standard, and subsequent

affordability of home videocassette players in the 1980s brought with them the

proliferation of the movie rental business. By the 1990s, the majority of market

share had consolidated to a few participants with similar business models

competing on selection, price, and especially location. National chains, such as

Blockbuster and Hollywood Video, grew by staking claims at strategic locations

with adequate population density. By 1990, Blockbuster professed to have a store

within a ten-minute drive of 70% of the U.S. population. Mom-and-pop video stores

survived by finding locations the chains did not seek.

Movie rental required that a customer leave his or her home with the intention of

renting, then make a spontaneous decision based on what was available. The cost of

a video rental ranged from $3.00 per week for older movies to $6.00 per three days

for new releases (allowing for weekend viewing when rented on Friday, the most

popular day). Small mom-and-pop stores typically had a collection of a few

hundred videos for rental; a Blockbuster store had about 2,500 titles. A store’s

video paid for itself after 13 rentals, so films with mass appeal were the norm;

nearly 70% of all films rented at Blockbuster were new releases. Limited selection

and stock-outs were a common concern, as was the relative convenience of store

hours.

Late returns were a thorny problem: A movie could not be rented until it was back

on the shelf, and a scarcity of titles might deter a customer from returning. So video

stores charged late fees, which monetized the delay and encouraged the customer to

return movies promptly. In reality, as one commentator noted, late fees called

attention to customer failure, in the manner of “a disapproving librarian tallying up

35 cents in overdue fines while floating the unspoken accusation you were

irresponsible on top of everything else.”1 When Blockbuster eventually dropped

many forms of late fees, the move resulted in a charge to revenue of $400 million.

The bricks-and-mortar value proposition was eroding.

DVD by Mail

DVD mail service started to gain popularity in the early 2000s. The subscribing

customer selected a movie on a website, and a DVD would arrive at his or her home

in about one business day. The customer could keep the DVD as long as he or she

liked, then mail it back to the provider in the envelope provided. By selecting

multiple movies and arranging them in order of priority in an online queue, the

customer could ensure prompt delivery of subsequent selections and always have

something on hand to watch as opportunities arose. Subscription tiers were based on

how many movies a customer could receive simultaneously and priced accordingly,

starting at $7.99 per month for one movie at a time. (See Exhibit 11-1 for a co

(Venkatesan 144-146)

The advent of videotape, acceptance of the VHS cassette standard, and subsequent

affordability of home videocassette players in the 1980s brought with them the

proliferation of the movie rental business. By the 1990s, the majority of market

share had consolidated to a few participants with similar business models

competing on selection, price, and especially location. National chains, such as

Blockbuster and Hollywood Video, grew by staking claims at strategic locations

with adequate population density. By 1990, Blockbuster professed to have a store

within a ten-minute drive of 70% of the U.S. population. Mom-and-pop video stores

survived by finding locations the chains did not seek.

Movie rental required that a customer leave his or her home with the intention of

renting, then make a spontaneous decision based on what was available. The cost of

a video rental ranged from $3.00 per week for older movies to $6.00 per three days

for new releases (allowing for weekend viewing when rented on Friday, the most

popular day). Small mom-and-pop stores typically had a collection of a few

hundred videos for rental; a Blockbuster store had about 2,500 titles. A store’s

video paid for itself after 13 rentals, so films with mass appeal were the norm;

nearly 70% of all films rented at Blockbuster were new releases. Limited selection

and stock-outs were a common concern, as was the relative convenience of store

hours.

Late returns were a thorny problem: A movie could not be rented until it was back

on the shelf, and a scarcity of titles might deter a customer from returning. So video

stores charged late fees, which monetized the delay and encouraged the customer to

return movies promptly. In reality, as one commentator noted, late fees called

attention to customer failure, in the manner of “a disapproving librarian tallying up

35 cents in overdue fines while floating the unspoken accusation you were

irresponsible on top of everything else.”1 When Blockbuster eventually dropped

many forms of late fees, the move resulted in a charge to revenue of $400 million.

The bricks-and-mortar value proposition was eroding.

DVD by Mail

DVD mail service started to gain popularity in the early 2000s. The subscribing

customer selected a movie on a website, and a DVD would arrive at his or her home

in about one business day. The customer could keep the DVD as long as he or she

liked, then mail it back to the provider in the envelope provided. By selecting

multiple movies and arranging them in order of priority in an online queue, the

customer could ensure prompt delivery of subsequent selections and always have

something on hand to watch as opportunities arose. Subscription tiers were based on

how many movies a customer could receive simultaneously and priced accordingly,

starting at $7.99 per month for one movie at a time. (See Exhibit 11-1 for a co

(Venkatesan 144-146)

Venkatesan, Rajkumar, Paul Farris, Ronald Wilcox. Cutting Edge Marketing Analysis:

Real World Cases and Data Sets for Hands on Learning. Pearson Learning

Solutions, 06/2014. VitalBook file.

DVD by Mail

DVD mail service started to gain popularity in the early 2000s. The subscribing

customer selected a movie on a website, and a DVD would arrive at his or her home

in about one business day. The customer could keep the DVD as long as he or she

liked, then mail it back to the provider in the envelope provided. By selecting

multiple movies and arranging them in order of priority in an online queue, the

customer could ensure prompt delivery of subsequent selections and always have

something on hand to watch as opportunities arose. Subscription tiers were based on

how many movies a customer could receive simultaneously and priced accordingly,

starting at $7.99 per month for one movie at a time. (See Exhibit 11-1 for a

complete pricing comparison.)

Video on Demand

Video on demand (VOD) was content distribution via an Internet-connected

television, computer, or mobile device. The customer selected a movie from an

online menu and, within seconds, the movie began streaming to his or her device.

The customer could view the content as it was downloaded, rather than waiting for

the complete file, which otherwise could take almost as long as the running time of

the film. No exchange of a data-storage medium was required, so stock-outs and

late fees were avoided, and a significantly larger and more eclectic catalog could be

offered.

Kiosk Rentals

Movie rental kiosks were freestanding dispensers of DVDs located in high-traffic

areas with extended—sometimes 24-hour—access, such as convenience stores,

grocery stores, and fast-food restaurants. Redbox, the dominant player, founded in

2003, was originally funded by McDonald’s. As of 2012, Redbox claimed to have

rented 1.5 billion movies from 30,000 kiosks nationwide and to operate a kiosk

within a five-minute drive of two thirds of the U.S. population. Its only significant

competitor, albeit a much smaller player, was Blockbuster’s “Blockbuster Express”

kiosks.

Kiosks revolutionized the rental price point (about $1.00 per night per movie) and

changed consumer renting behavior by eliminating the planning ahead required by

DVD-by-mail services and the need to go to another location required by rental

stores. Plus, 24-hour access freed customers from time constraints. Selection,

however, was limited by two major shortfalls: the physical space inside the kiosk

Real World Cases and Data Sets for Hands on Learning. Pearson Learning

Solutions, 06/2014. VitalBook file.

DVD by Mail

DVD mail service started to gain popularity in the early 2000s. The subscribing

customer selected a movie on a website, and a DVD would arrive at his or her home

in about one business day. The customer could keep the DVD as long as he or she

liked, then mail it back to the provider in the envelope provided. By selecting

multiple movies and arranging them in order of priority in an online queue, the

customer could ensure prompt delivery of subsequent selections and always have

something on hand to watch as opportunities arose. Subscription tiers were based on

how many movies a customer could receive simultaneously and priced accordingly,

starting at $7.99 per month for one movie at a time. (See Exhibit 11-1 for a

complete pricing comparison.)

Video on Demand

Video on demand (VOD) was content distribution via an Internet-connected

television, computer, or mobile device. The customer selected a movie from an

online menu and, within seconds, the movie began streaming to his or her device.

The customer could view the content as it was downloaded, rather than waiting for

the complete file, which otherwise could take almost as long as the running time of

the film. No exchange of a data-storage medium was required, so stock-outs and

late fees were avoided, and a significantly larger and more eclectic catalog could be

offered.

Kiosk Rentals

Movie rental kiosks were freestanding dispensers of DVDs located in high-traffic

areas with extended—sometimes 24-hour—access, such as convenience stores,

grocery stores, and fast-food restaurants. Redbox, the dominant player, founded in

2003, was originally funded by McDonald’s. As of 2012, Redbox claimed to have

rented 1.5 billion movies from 30,000 kiosks nationwide and to operate a kiosk

within a five-minute drive of two thirds of the U.S. population. Its only significant

competitor, albeit a much smaller player, was Blockbuster’s “Blockbuster Express”

kiosks.

Kiosks revolutionized the rental price point (about $1.00 per night per movie) and

changed consumer renting behavior by eliminating the planning ahead required by

DVD-by-mail services and the need to go to another location required by rental

stores. Plus, 24-hour access freed customers from time constraints. Selection,

however, was limited by two major shortfalls: the physical space inside the kiosk

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

and delayed releases to kiosks by movie studios wary of cannibalizing DVD sales.

A New Range of Business Models

As content delivery methods increased, an industry participant could employ different

pricing heuristics across different channels and different end-user content licenses. As

such, revenue model, delivery method, and content licensing were dimensions by

which each participant might be assessed (see Table 11-1).

In terms of revenue, a business was either pay-per-view or monthly subscription.

Depending on the delivery method, the one-time fee of the pay-per-view model

would entitle the customer to rent one DVD by mail or online streaming access for a

finite time period. In the case of purchase, a one-time fee entitled the buyer to

indefinite ownership of streaming content or of an actual DVD.

Table 11-1 Perceptual Market Map for the VHS and

Digital Eras

(Venkatesan 146-147)

Venkatesan, Rajkumar, Paul Farris, Ronald Wilcox. Cutting Edge Marketing Analysis:

Real World Cases and Data Sets for Hands on Learning. Pearson Learning

Solutions, 06/2014. VitalBook file.

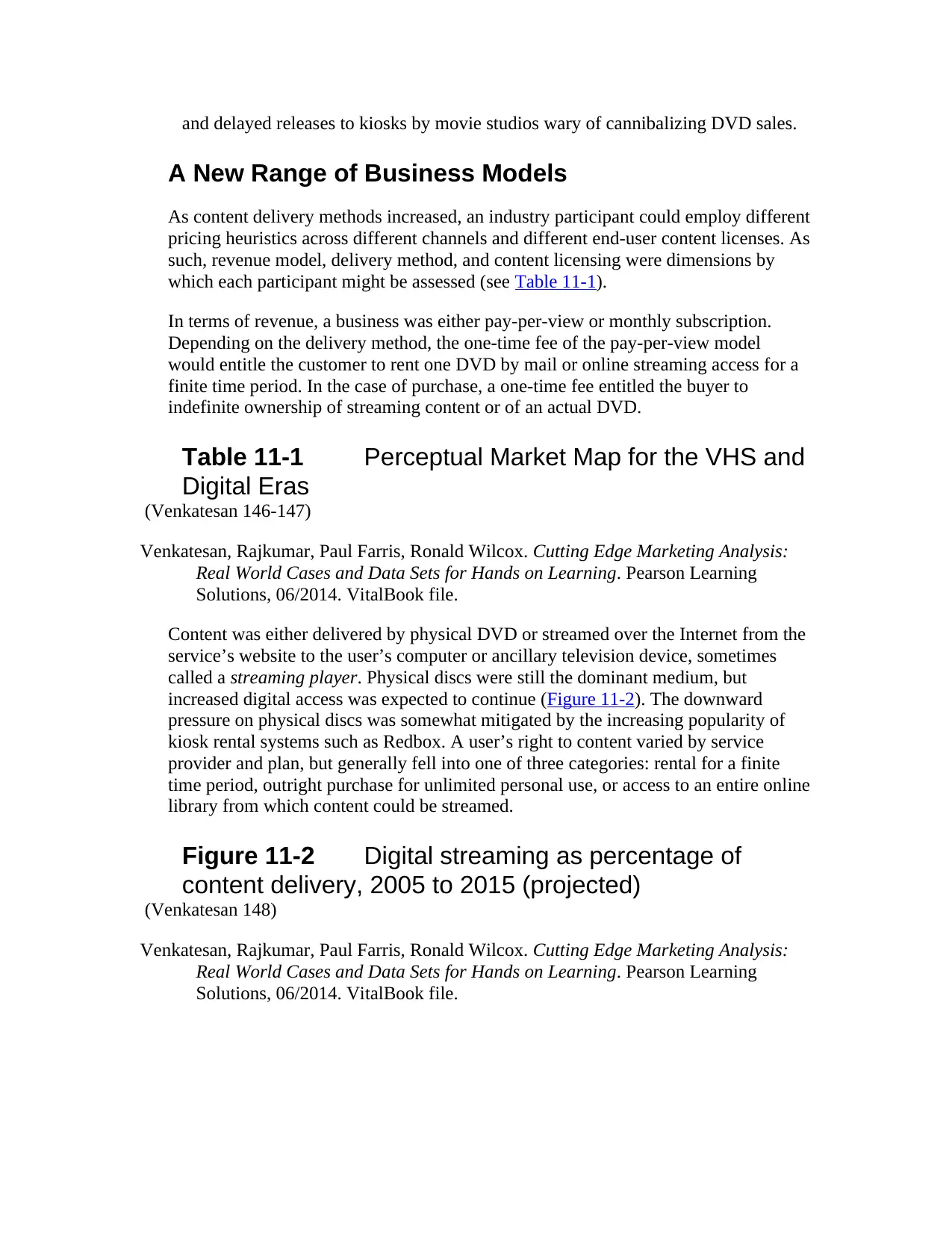

Content was either delivered by physical DVD or streamed over the Internet from the

service’s website to the user’s computer or ancillary television device, sometimes

called a streaming player. Physical discs were still the dominant medium, but

increased digital access was expected to continue (Figure 11-2). The downward

pressure on physical discs was somewhat mitigated by the increasing popularity of

kiosk rental systems such as Redbox. A user’s right to content varied by service

provider and plan, but generally fell into one of three categories: rental for a finite

time period, outright purchase for unlimited personal use, or access to an entire online

library from which content could be streamed.

Figure 11-2 Digital streaming as percentage of

content delivery, 2005 to 2015 (projected)

(Venkatesan 148)

Venkatesan, Rajkumar, Paul Farris, Ronald Wilcox. Cutting Edge Marketing Analysis:

Real World Cases and Data Sets for Hands on Learning. Pearson Learning

Solutions, 06/2014. VitalBook file.

A New Range of Business Models

As content delivery methods increased, an industry participant could employ different

pricing heuristics across different channels and different end-user content licenses. As

such, revenue model, delivery method, and content licensing were dimensions by

which each participant might be assessed (see Table 11-1).

In terms of revenue, a business was either pay-per-view or monthly subscription.

Depending on the delivery method, the one-time fee of the pay-per-view model

would entitle the customer to rent one DVD by mail or online streaming access for a

finite time period. In the case of purchase, a one-time fee entitled the buyer to

indefinite ownership of streaming content or of an actual DVD.

Table 11-1 Perceptual Market Map for the VHS and

Digital Eras

(Venkatesan 146-147)

Venkatesan, Rajkumar, Paul Farris, Ronald Wilcox. Cutting Edge Marketing Analysis:

Real World Cases and Data Sets for Hands on Learning. Pearson Learning

Solutions, 06/2014. VitalBook file.

Content was either delivered by physical DVD or streamed over the Internet from the

service’s website to the user’s computer or ancillary television device, sometimes

called a streaming player. Physical discs were still the dominant medium, but

increased digital access was expected to continue (Figure 11-2). The downward

pressure on physical discs was somewhat mitigated by the increasing popularity of

kiosk rental systems such as Redbox. A user’s right to content varied by service

provider and plan, but generally fell into one of three categories: rental for a finite

time period, outright purchase for unlimited personal use, or access to an entire online

library from which content could be streamed.

Figure 11-2 Digital streaming as percentage of

content delivery, 2005 to 2015 (projected)

(Venkatesan 148)

Venkatesan, Rajkumar, Paul Farris, Ronald Wilcox. Cutting Edge Marketing Analysis:

Real World Cases and Data Sets for Hands on Learning. Pearson Learning

Solutions, 06/2014. VitalBook file.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Source: Mintel/Digital Entertainment Group, May 2011.

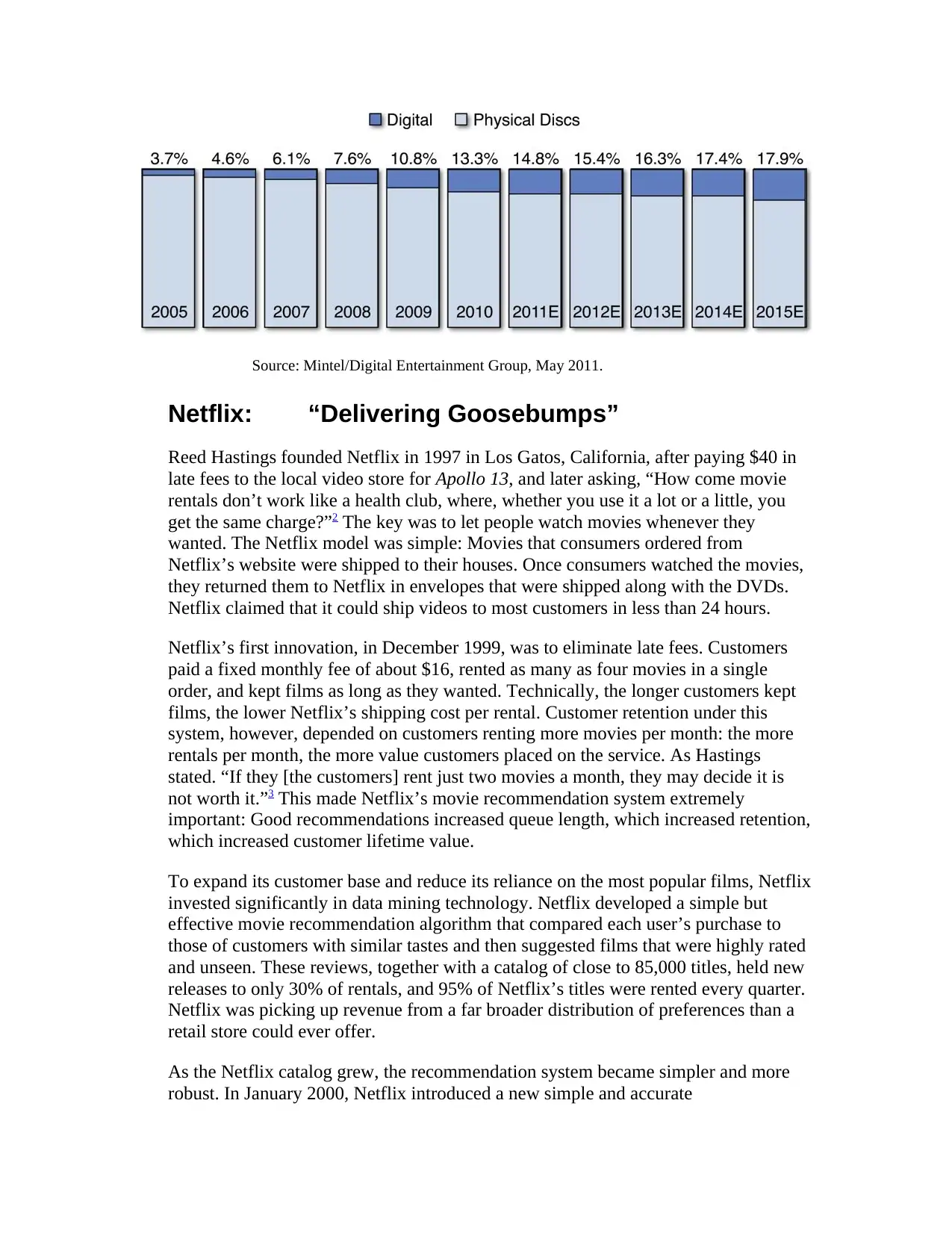

Netflix: “Delivering Goosebumps”

Reed Hastings founded Netflix in 1997 in Los Gatos, California, after paying $40 in

late fees to the local video store for Apollo 13, and later asking, “How come movie

rentals don’t work like a health club, where, whether you use it a lot or a little, you

get the same charge?”2 The key was to let people watch movies whenever they

wanted. The Netflix model was simple: Movies that consumers ordered from

Netflix’s website were shipped to their houses. Once consumers watched the movies,

they returned them to Netflix in envelopes that were shipped along with the DVDs.

Netflix claimed that it could ship videos to most customers in less than 24 hours.

Netflix’s first innovation, in December 1999, was to eliminate late fees. Customers

paid a fixed monthly fee of about $16, rented as many as four movies in a single

order, and kept films as long as they wanted. Technically, the longer customers kept

films, the lower Netflix’s shipping cost per rental. Customer retention under this

system, however, depended on customers renting more movies per month: the more

rentals per month, the more value customers placed on the service. As Hastings

stated. “If they [the customers] rent just two movies a month, they may decide it is

not worth it.”3 This made Netflix’s movie recommendation system extremely

important: Good recommendations increased queue length, which increased retention,

which increased customer lifetime value.

To expand its customer base and reduce its reliance on the most popular films, Netflix

invested significantly in data mining technology. Netflix developed a simple but

effective movie recommendation algorithm that compared each user’s purchase to

those of customers with similar tastes and then suggested films that were highly rated

and unseen. These reviews, together with a catalog of close to 85,000 titles, held new

releases to only 30% of rentals, and 95% of Netflix’s titles were rented every quarter.

Netflix was picking up revenue from a far broader distribution of preferences than a

retail store could ever offer.

As the Netflix catalog grew, the recommendation system became simpler and more

robust. In January 2000, Netflix introduced a new simple and accurate

Netflix: “Delivering Goosebumps”

Reed Hastings founded Netflix in 1997 in Los Gatos, California, after paying $40 in

late fees to the local video store for Apollo 13, and later asking, “How come movie

rentals don’t work like a health club, where, whether you use it a lot or a little, you

get the same charge?”2 The key was to let people watch movies whenever they

wanted. The Netflix model was simple: Movies that consumers ordered from

Netflix’s website were shipped to their houses. Once consumers watched the movies,

they returned them to Netflix in envelopes that were shipped along with the DVDs.

Netflix claimed that it could ship videos to most customers in less than 24 hours.

Netflix’s first innovation, in December 1999, was to eliminate late fees. Customers

paid a fixed monthly fee of about $16, rented as many as four movies in a single

order, and kept films as long as they wanted. Technically, the longer customers kept

films, the lower Netflix’s shipping cost per rental. Customer retention under this

system, however, depended on customers renting more movies per month: the more

rentals per month, the more value customers placed on the service. As Hastings

stated. “If they [the customers] rent just two movies a month, they may decide it is

not worth it.”3 This made Netflix’s movie recommendation system extremely

important: Good recommendations increased queue length, which increased retention,

which increased customer lifetime value.

To expand its customer base and reduce its reliance on the most popular films, Netflix

invested significantly in data mining technology. Netflix developed a simple but

effective movie recommendation algorithm that compared each user’s purchase to

those of customers with similar tastes and then suggested films that were highly rated

and unseen. These reviews, together with a catalog of close to 85,000 titles, held new

releases to only 30% of rentals, and 95% of Netflix’s titles were rented every quarter.

Netflix was picking up revenue from a far broader distribution of preferences than a

retail store could ever offer.

As the Netflix catalog grew, the recommendation system became simpler and more

robust. In January 2000, Netflix introduced a new simple and accurate

recommendation system called CineMatch. Each customer was prompted to rate

certain movie genres and specific movies on a one- to five-star scale. The program

found others in its database with similar preferences and then offered a predicted star

value for each movie. As the customer rated more films, the accuracy of the data

improved substantially. As Hastings stated, “Over 50% of our traffic comes via the

recommendation system. It requires a lot of database work done in real time.”4 By

2007, Netflix had close to one billion movie reviews, with customers reviewing an

average of 200 movies each.

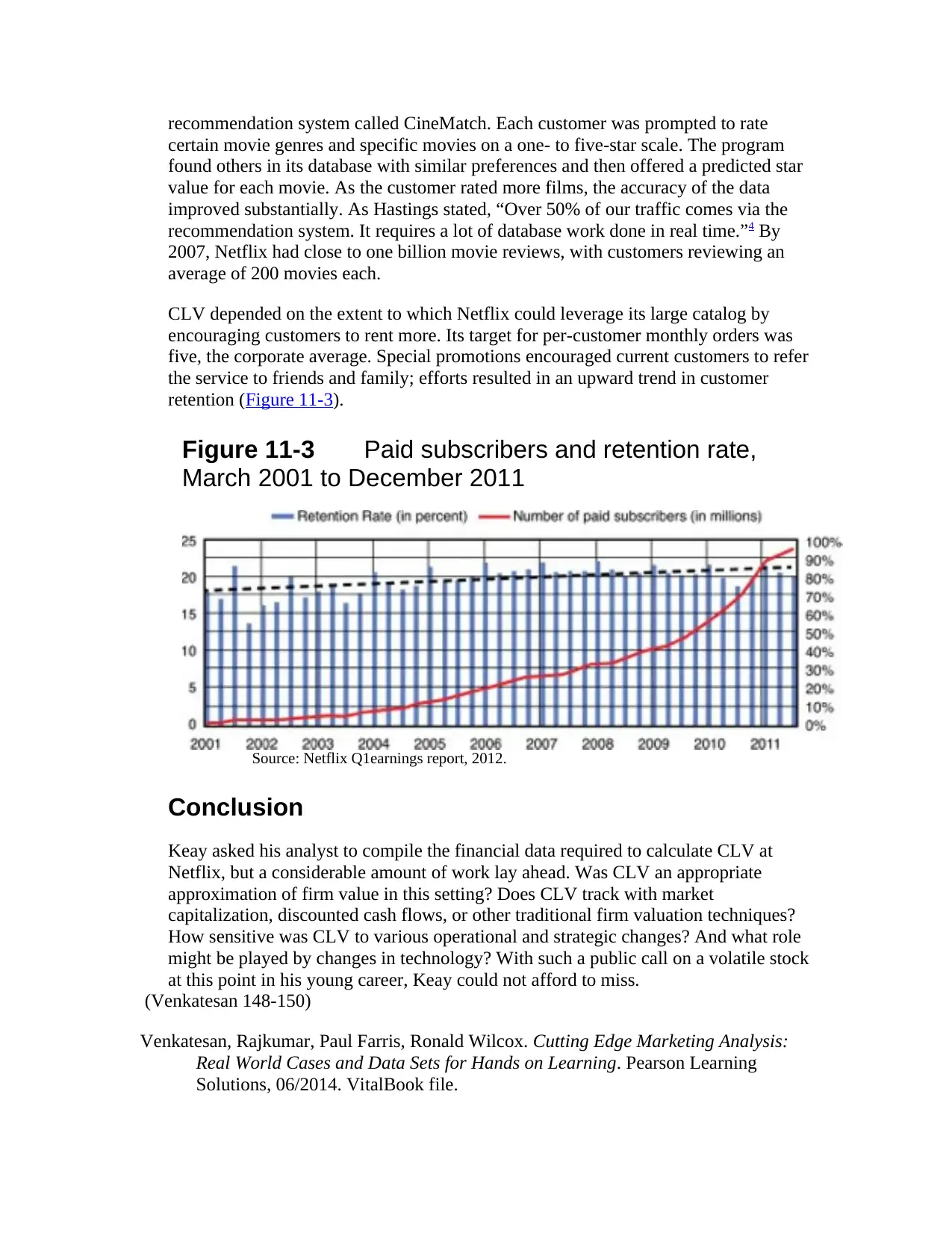

CLV depended on the extent to which Netflix could leverage its large catalog by

encouraging customers to rent more. Its target for per-customer monthly orders was

five, the corporate average. Special promotions encouraged current customers to refer

the service to friends and family; efforts resulted in an upward trend in customer

retention (Figure 11-3).

Figure 11-3 Paid subscribers and retention rate,

March 2001 to December 2011

Source: Netflix Q1earnings report, 2012.

Conclusion

Keay asked his analyst to compile the financial data required to calculate CLV at

Netflix, but a considerable amount of work lay ahead. Was CLV an appropriate

approximation of firm value in this setting? Does CLV track with market

capitalization, discounted cash flows, or other traditional firm valuation techniques?

How sensitive was CLV to various operational and strategic changes? And what role

might be played by changes in technology? With such a public call on a volatile stock

at this point in his young career, Keay could not afford to miss.

(Venkatesan 148-150)

Venkatesan, Rajkumar, Paul Farris, Ronald Wilcox. Cutting Edge Marketing Analysis:

Real World Cases and Data Sets for Hands on Learning. Pearson Learning

Solutions, 06/2014. VitalBook file.

certain movie genres and specific movies on a one- to five-star scale. The program

found others in its database with similar preferences and then offered a predicted star

value for each movie. As the customer rated more films, the accuracy of the data

improved substantially. As Hastings stated, “Over 50% of our traffic comes via the

recommendation system. It requires a lot of database work done in real time.”4 By

2007, Netflix had close to one billion movie reviews, with customers reviewing an

average of 200 movies each.

CLV depended on the extent to which Netflix could leverage its large catalog by

encouraging customers to rent more. Its target for per-customer monthly orders was

five, the corporate average. Special promotions encouraged current customers to refer

the service to friends and family; efforts resulted in an upward trend in customer

retention (Figure 11-3).

Figure 11-3 Paid subscribers and retention rate,

March 2001 to December 2011

Source: Netflix Q1earnings report, 2012.

Conclusion

Keay asked his analyst to compile the financial data required to calculate CLV at

Netflix, but a considerable amount of work lay ahead. Was CLV an appropriate

approximation of firm value in this setting? Does CLV track with market

capitalization, discounted cash flows, or other traditional firm valuation techniques?

How sensitive was CLV to various operational and strategic changes? And what role

might be played by changes in technology? With such a public call on a volatile stock

at this point in his young career, Keay could not afford to miss.

(Venkatesan 148-150)

Venkatesan, Rajkumar, Paul Farris, Ronald Wilcox. Cutting Edge Marketing Analysis:

Real World Cases and Data Sets for Hands on Learning. Pearson Learning

Solutions, 06/2014. VitalBook file.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 6

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.