Understanding New York City's Electricity: A Comprehensive Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2021/11/16

|6

|2993

|89

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive overview of how New York City's electricity is generated, transmitted, and distributed. It begins by tracing the historical evolution of power generation in the city, from coal-fired plants to the current mix of natural gas, nuclear, hydroelectric, and renewable sources. The report details the challenges of balancing supply and demand, managing the power grid, and the role of the New York Independent System Operator (NYISO). It also examines the transmission infrastructure, including high-voltage lines and bottlenecks, and the efforts to upgrade and expand the grid. The report highlights the role of Con Edison in delivering power to homes and businesses, including the use of smart meters and the integration of renewable energy sources like solar and wind. Finally, the report addresses the challenges of meeting clean energy goals, the impact of weather and climate change, and the future of the city's power grid, including the integration of renewable energy sources and smart technologies.

How New York City Gets Its Electricity

By EMILY S. RUEB: Adapted from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/02/10/nyregion/how-new-york-city-gets-its-electricity-power-grid.html

When you turn on a light or charge your phone, the electricity coming from the outlet may well have traveled

hundreds of miles across the power grid that blankets most of North America — the world’s largest machine,

and one of its most eccentric. Your household power may have been generated by Niagara Falls, or by a

natural-gas-fired plant on a barge floating off the Brooklyn shore. But the kilowatt-hour produced down the

block probably costs more than the one produced at the Canadian border.

Moreover, a surprising portion of the system is idle except for the hottest days of the year, when already

bottlenecked transmission lines into the New York City area reach their physical limit. “We have a system

which is energy-inefficient because it was never designed to be efficient,” said Richard L. Kauffman, the state’s

so-called energy czar, who is leading its plans to reimagine the power grid.

It’s like a mainframe computer in the age of cloud computing, Mr. Kauffman added, and with climate change,

the state has to “rethink that basic architecture.” But how does it work now?

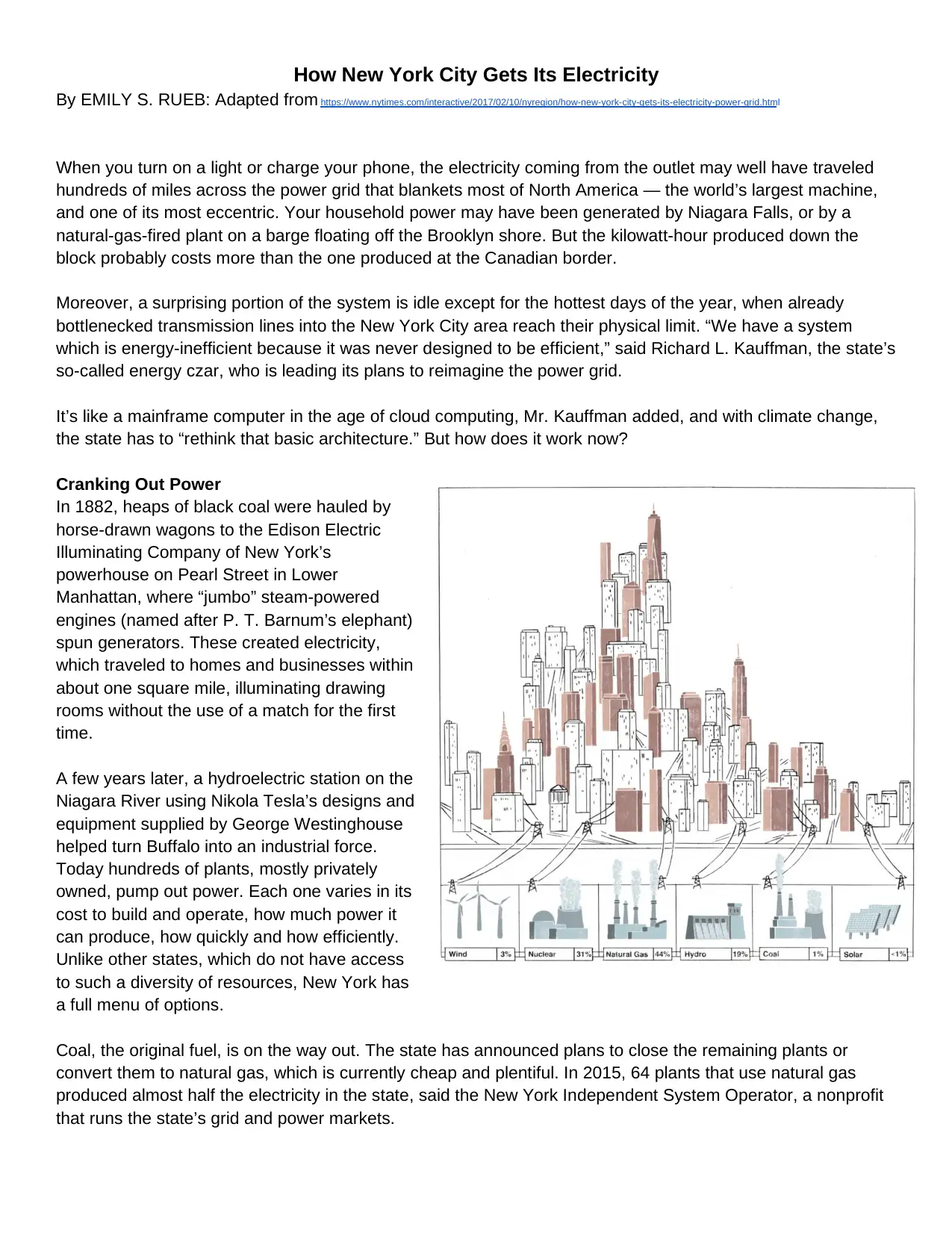

Cranking Out Power

In 1882, heaps of black coal were hauled by

horse-drawn wagons to the Edison Electric

Illuminating Company of New York’s

powerhouse on Pearl Street in Lower

Manhattan, where “jumbo” steam-powered

engines (named after P. T. Barnum’s elephant)

spun generators. These created electricity,

which traveled to homes and businesses within

about one square mile, illuminating drawing

rooms without the use of a match for the first

time.

A few years later, a hydroelectric station on the

Niagara River using Nikola Tesla’s designs and

equipment supplied by George Westinghouse

helped turn Buffalo into an industrial force.

Today hundreds of plants, mostly privately

owned, pump out power. Each one varies in its

cost to build and operate, how much power it

can produce, how quickly and how efficiently.

Unlike other states, which do not have access

to such a diversity of resources, New York has

a full menu of options.

Coal, the original fuel, is on the way out. The state has announced plans to close the remaining plants or

convert them to natural gas, which is currently cheap and plentiful. In 2015, 64 plants that use natural gas

produced almost half the electricity in the state, said the New York Independent System Operator, a nonprofit

that runs the state’s grid and power markets.

By EMILY S. RUEB: Adapted from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/02/10/nyregion/how-new-york-city-gets-its-electricity-power-grid.html

When you turn on a light or charge your phone, the electricity coming from the outlet may well have traveled

hundreds of miles across the power grid that blankets most of North America — the world’s largest machine,

and one of its most eccentric. Your household power may have been generated by Niagara Falls, or by a

natural-gas-fired plant on a barge floating off the Brooklyn shore. But the kilowatt-hour produced down the

block probably costs more than the one produced at the Canadian border.

Moreover, a surprising portion of the system is idle except for the hottest days of the year, when already

bottlenecked transmission lines into the New York City area reach their physical limit. “We have a system

which is energy-inefficient because it was never designed to be efficient,” said Richard L. Kauffman, the state’s

so-called energy czar, who is leading its plans to reimagine the power grid.

It’s like a mainframe computer in the age of cloud computing, Mr. Kauffman added, and with climate change,

the state has to “rethink that basic architecture.” But how does it work now?

Cranking Out Power

In 1882, heaps of black coal were hauled by

horse-drawn wagons to the Edison Electric

Illuminating Company of New York’s

powerhouse on Pearl Street in Lower

Manhattan, where “jumbo” steam-powered

engines (named after P. T. Barnum’s elephant)

spun generators. These created electricity,

which traveled to homes and businesses within

about one square mile, illuminating drawing

rooms without the use of a match for the first

time.

A few years later, a hydroelectric station on the

Niagara River using Nikola Tesla’s designs and

equipment supplied by George Westinghouse

helped turn Buffalo into an industrial force.

Today hundreds of plants, mostly privately

owned, pump out power. Each one varies in its

cost to build and operate, how much power it

can produce, how quickly and how efficiently.

Unlike other states, which do not have access

to such a diversity of resources, New York has

a full menu of options.

Coal, the original fuel, is on the way out. The state has announced plans to close the remaining plants or

convert them to natural gas, which is currently cheap and plentiful. In 2015, 64 plants that use natural gas

produced almost half the electricity in the state, said the New York Independent System Operator, a nonprofit

that runs the state’s grid and power markets.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Four nuclear plants accounted for about a third of it. Though disposing of nuclear waste remains a concern, the

state wants to subsidize nuclear plants upstate because of the steady, carbon-free power they provide. But

Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo’s recent decision to force the closing of the Indian Point power plant in suburban

Westchester County has raised questions about the state’s ability to meet its clean energy goals and how it will

make up for the energy the plant provides.

In New York there are 180 hydroelectric facilities, which produced 19 percent of the state’s electricity, and

which remain crucial to clean power production. By 2030, Mr. Cuomo wants half of the electricity consumed in

the state to come from renewable sources produced here or imported from places like Canada and New

England. According to the latest figures, less than a quarter of the electric energy produced in New York came

from renewables.

While there are tens of thousands of residential and commercial solar energy systems, only one utility-scale

solar photovoltaic power plant is included in the Nyiso’s estimates of solar production.

Large-scale wind has had more success, and the state is pushing for more; about 30 wind farms are planned

upstate. And the state recently approved the nation’s largest offshore wind farm, which could power 50,000

homes on Long Island by the end of 2022. A second site near the Rockaway Peninsula in Queens is in the

works but is years away. Fddxa q`````````

The cost of building wind and solar plants has fallen, but these power sources are intermittent. Until more

storage is plugged into the grid, like batteries or pumped hydro plants, which pump water into reservoirs to

store power for later use, other generators must be available to supplement solar and wind power.

A standard part of the electric arsenal are generators called “peakers,” which are needed to keep the grid

reliable but might run only a few days a year. New York City has about 16 such plants, mostly around the

waterfront, which spring into action on the hottest days of the year or if transmission lines or power plants

upstate malfunction. Some sit on barges, and all are designed to switch on quickly. The trade-off for the rapid

response is usually higher costs and carbon emissions.

As a result, customers pay for plants and wires that “a lot of the time are hardly used,” said Mr. Kauffman, the

energy czar.

The entire system was designed to meet demand extremes and handle the worst-case situation.

\

\\\\\\\\\\The Delicate Art of Balancing the Grid

Inside a $38 million control room near Albany, a team of seven employees of the New York Independent

System Operator is always on duty, monitoring electricity zooming through the state’s grid and coming in from

and out to neighboring grids.

Nyiso (pronounced NIGH-so) is one of 36 entities responsible for the Eastern Interconnection, one of the

country’s three main grids extending from the Rockies to the East Coast in the United States and

Saskatchewan to Nova Scotia in Canada.

state wants to subsidize nuclear plants upstate because of the steady, carbon-free power they provide. But

Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo’s recent decision to force the closing of the Indian Point power plant in suburban

Westchester County has raised questions about the state’s ability to meet its clean energy goals and how it will

make up for the energy the plant provides.

In New York there are 180 hydroelectric facilities, which produced 19 percent of the state’s electricity, and

which remain crucial to clean power production. By 2030, Mr. Cuomo wants half of the electricity consumed in

the state to come from renewable sources produced here or imported from places like Canada and New

England. According to the latest figures, less than a quarter of the electric energy produced in New York came

from renewables.

While there are tens of thousands of residential and commercial solar energy systems, only one utility-scale

solar photovoltaic power plant is included in the Nyiso’s estimates of solar production.

Large-scale wind has had more success, and the state is pushing for more; about 30 wind farms are planned

upstate. And the state recently approved the nation’s largest offshore wind farm, which could power 50,000

homes on Long Island by the end of 2022. A second site near the Rockaway Peninsula in Queens is in the

works but is years away. Fddxa q`````````

The cost of building wind and solar plants has fallen, but these power sources are intermittent. Until more

storage is plugged into the grid, like batteries or pumped hydro plants, which pump water into reservoirs to

store power for later use, other generators must be available to supplement solar and wind power.

A standard part of the electric arsenal are generators called “peakers,” which are needed to keep the grid

reliable but might run only a few days a year. New York City has about 16 such plants, mostly around the

waterfront, which spring into action on the hottest days of the year or if transmission lines or power plants

upstate malfunction. Some sit on barges, and all are designed to switch on quickly. The trade-off for the rapid

response is usually higher costs and carbon emissions.

As a result, customers pay for plants and wires that “a lot of the time are hardly used,” said Mr. Kauffman, the

energy czar.

The entire system was designed to meet demand extremes and handle the worst-case situation.

\

\\\\\\\\\\The Delicate Art of Balancing the Grid

Inside a $38 million control room near Albany, a team of seven employees of the New York Independent

System Operator is always on duty, monitoring electricity zooming through the state’s grid and coming in from

and out to neighboring grids.

Nyiso (pronounced NIGH-so) is one of 36 entities responsible for the Eastern Interconnection, one of the

country’s three main grids extending from the Rockies to the East Coast in the United States and

Saskatchewan to Nova Scotia in Canada.

Unlike water, electricity can’t be stored in a bucket. While batteries are improving, most electricity is used the

instant it is created.

The team constantly calculates how much power is needed and which plants can produce it at the lowest cost.

Every five minutes, a computer system directs plants to dial up or scale down production to ensure enough

electricity is available to keep the lights on without overloading transmission wires. If the system is out of

balance or the flow of electricity is destabilized, it can damage equipment or cause power failures.

Operators undergo psychological evaluations to ensure they can handle stress, and they spend weeks every

year inside simulation labs preparing for a hurricane or cyberattack. Still, the No. 1 enemy is tree branches, as

Gretchen Bakke pointed out in her book, “The Grid: The Fraying Wires Between Americans and Our Energy

Future.”

In 2003, the country’s worst blackout started with a sagging power line in Ohio that shorted out after touching a

tree branch. A series of human errors and a computer problem plunged about 50 million people into darkness

from New York City to Toronto and cost the United States economy about $6 billion.

Jon Sawyer, the chief system operator for Nyiso, said that today, computer systems receive 50,000 data points

about every six seconds, and operators monitor regional activity on a 2,300-square-foot video wall. Mandatory

reliability standards have been put in place for the thousands of entities involved in the operation of the

country’s electric systems.

The biggest daily variable is weather. Storms can flood equipment, and bright, hot days can cause

transformers to overheat and customers to crank up air-conditioners.

Leaning on solar and wind means a greater dependence on weather, just as weather patterns have become

less predictable. Nyiso has developed sophisticated tools using climate data to predict how much power each

wind farm will generate and to find ways to balance the system if the wind suddenly dies down, Mr. Sawyer

said. It is working on methods to track cloud cover and other conditions that affect the output of solar panels.

Transmitting Power Efficiently

The system’s backbone is the 11,124 miles of high-voltage lines running overhead and underground that carry

electricity to local utilities. Unlike water pipes, transmission lines are not hollow, and they can overheat or shut

down if too much power flows through them.

Since most power is generated in less populated areas, certain lines that carry it downstate during times of

peak demand can become gridlocked. Nearly 60 percent of the state’s electricity is consumed in the New York

City area, where only 40 percent of it is made. “New York is the poster child for congestion,” said Bill Booth, a

senior adviser to the United States Energy Information Administration.

To get around bottlenecks, grid operators may turn on more expensive or less efficient generators closer to

where the demand is. Think of it as paying more for a carton of milk at the bodega next door than at the

supermarket 12 blocks away.

The state is prioritizing projects to bring more power downstate from wind farms and hydro plants. The need is

even more urgent with plans to close Indian Point as soon as 2021, as it supplies about one-fourth of the

power consumed in New York City and Westchester County.

instant it is created.

The team constantly calculates how much power is needed and which plants can produce it at the lowest cost.

Every five minutes, a computer system directs plants to dial up or scale down production to ensure enough

electricity is available to keep the lights on without overloading transmission wires. If the system is out of

balance or the flow of electricity is destabilized, it can damage equipment or cause power failures.

Operators undergo psychological evaluations to ensure they can handle stress, and they spend weeks every

year inside simulation labs preparing for a hurricane or cyberattack. Still, the No. 1 enemy is tree branches, as

Gretchen Bakke pointed out in her book, “The Grid: The Fraying Wires Between Americans and Our Energy

Future.”

In 2003, the country’s worst blackout started with a sagging power line in Ohio that shorted out after touching a

tree branch. A series of human errors and a computer problem plunged about 50 million people into darkness

from New York City to Toronto and cost the United States economy about $6 billion.

Jon Sawyer, the chief system operator for Nyiso, said that today, computer systems receive 50,000 data points

about every six seconds, and operators monitor regional activity on a 2,300-square-foot video wall. Mandatory

reliability standards have been put in place for the thousands of entities involved in the operation of the

country’s electric systems.

The biggest daily variable is weather. Storms can flood equipment, and bright, hot days can cause

transformers to overheat and customers to crank up air-conditioners.

Leaning on solar and wind means a greater dependence on weather, just as weather patterns have become

less predictable. Nyiso has developed sophisticated tools using climate data to predict how much power each

wind farm will generate and to find ways to balance the system if the wind suddenly dies down, Mr. Sawyer

said. It is working on methods to track cloud cover and other conditions that affect the output of solar panels.

Transmitting Power Efficiently

The system’s backbone is the 11,124 miles of high-voltage lines running overhead and underground that carry

electricity to local utilities. Unlike water pipes, transmission lines are not hollow, and they can overheat or shut

down if too much power flows through them.

Since most power is generated in less populated areas, certain lines that carry it downstate during times of

peak demand can become gridlocked. Nearly 60 percent of the state’s electricity is consumed in the New York

City area, where only 40 percent of it is made. “New York is the poster child for congestion,” said Bill Booth, a

senior adviser to the United States Energy Information Administration.

To get around bottlenecks, grid operators may turn on more expensive or less efficient generators closer to

where the demand is. Think of it as paying more for a carton of milk at the bodega next door than at the

supermarket 12 blocks away.

The state is prioritizing projects to bring more power downstate from wind farms and hydro plants. The need is

even more urgent with plans to close Indian Point as soon as 2021, as it supplies about one-fourth of the

power consumed in New York City and Westchester County.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

But building new power lines is fiercely unpopular. Residents don’t want high-voltage lines in their backyards,

and local power generators dislike competition from cheaper power brought in from farther away. Even if the

lines are below ground, like the ones that bring power to Manhattan from New Jersey through the muck of the

Hudson River, securing federal and state permits can take years.

One project to bring hydropower from Quebec to New York City under Lake Champlain and the Hudson has

been in the works since 2008.

Despite enhancements, the transmission grid is aging. More than 80 percent of the lines went active before

1980, and Nyiso estimates that almost 5,000 miles of high-voltage transmission lines will have to be replaced

in the next 30 years at a cost of about $25 billion.

Delivering Power to Your Home

Consolidated Edison’s system, which originally covered about a square mile in Lower Manhattan, now

stretches out over 660 square miles in the city and Westchester.

There are about 200 networks that operate independently to balance and regulate the flow of electricity in

dense areas. Manhattan alone has 39 networks; Rockefeller Center, for example, has its own.

In all, there are 129,935 miles of cables snaking underground and overhead, enough to reach more than

halfway to the moon.

The largest of the state’s six electric utilities, Con Ed spends millions of dollars a year to open utility holes and

dig into streets crowded with gas mains, fiber-optic cables, steam pipes and subway lines to make repairs and

upgrades to its vast underground network. Partly as a result, its customers pay among the highest electricity

rates in the country.

Operators in Con Ed’s energy control center, housed in a location the utility will not disclose, ensure that

enough power flows through its network to serve more than nine million people, even during a heat wave.

Much of the year, peak demand is around 5 p.m., when evening rush subways and elevators take commuters

home, children turn on video games and families open refrigerator doors to start dinner. In summer, it is around

3 p.m., when air-conditioners are blasting.

While Con Ed’s system is among the most reliable in the country, the company cannot prevent squirrels from

chewing wires or transformers. But it is working to prepare for disastrous weather. Since Hurricane Sandy in

2012, the utility has spent about $1 billion to raise, waterproof or build walls around equipment in lower

elevations and to carve up distribution networks so that smaller sections can be shut off remotely when

floodwaters rise.

With the proliferation of residential and commercial solar installations, customers are now feeding power back

to the grid.

Robert Schimmenti, who leads Con Ed’s electric operations, said it was developing systems to integrate the

increasing numbers of devices on the other side of the meter, like fuel cells and batteries, which are sometimes

linked in a microgrid, that the utility does not control.

and local power generators dislike competition from cheaper power brought in from farther away. Even if the

lines are below ground, like the ones that bring power to Manhattan from New Jersey through the muck of the

Hudson River, securing federal and state permits can take years.

One project to bring hydropower from Quebec to New York City under Lake Champlain and the Hudson has

been in the works since 2008.

Despite enhancements, the transmission grid is aging. More than 80 percent of the lines went active before

1980, and Nyiso estimates that almost 5,000 miles of high-voltage transmission lines will have to be replaced

in the next 30 years at a cost of about $25 billion.

Delivering Power to Your Home

Consolidated Edison’s system, which originally covered about a square mile in Lower Manhattan, now

stretches out over 660 square miles in the city and Westchester.

There are about 200 networks that operate independently to balance and regulate the flow of electricity in

dense areas. Manhattan alone has 39 networks; Rockefeller Center, for example, has its own.

In all, there are 129,935 miles of cables snaking underground and overhead, enough to reach more than

halfway to the moon.

The largest of the state’s six electric utilities, Con Ed spends millions of dollars a year to open utility holes and

dig into streets crowded with gas mains, fiber-optic cables, steam pipes and subway lines to make repairs and

upgrades to its vast underground network. Partly as a result, its customers pay among the highest electricity

rates in the country.

Operators in Con Ed’s energy control center, housed in a location the utility will not disclose, ensure that

enough power flows through its network to serve more than nine million people, even during a heat wave.

Much of the year, peak demand is around 5 p.m., when evening rush subways and elevators take commuters

home, children turn on video games and families open refrigerator doors to start dinner. In summer, it is around

3 p.m., when air-conditioners are blasting.

While Con Ed’s system is among the most reliable in the country, the company cannot prevent squirrels from

chewing wires or transformers. But it is working to prepare for disastrous weather. Since Hurricane Sandy in

2012, the utility has spent about $1 billion to raise, waterproof or build walls around equipment in lower

elevations and to carve up distribution networks so that smaller sections can be shut off remotely when

floodwaters rise.

With the proliferation of residential and commercial solar installations, customers are now feeding power back

to the grid.

Robert Schimmenti, who leads Con Ed’s electric operations, said it was developing systems to integrate the

increasing numbers of devices on the other side of the meter, like fuel cells and batteries, which are sometimes

linked in a microgrid, that the utility does not control.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

In May, Con Ed will begin installing “smart meters” in businesses across the city, and, in July, at homes on

Staten Island, giving customers detailed summaries about consumption and helping operators diagnose

problems without dispatching a truck.

To help finance the $1.3 billion project and to modernize its distribution networks, Con Ed requested a rate

increase, which the state approved in January. After a nearly five-year freeze, customers will see a raise of 2.3

percent to 2.4 percent in the next three years. A typical city resident who uses 300 kilowatt-hours per month

would see an increase from $78.52 to $80.30.

What’s Next?

Instead of moving power from large, central generating stations, where energy flows in only one direction and

about 5 percent vanishes in transit (more during peak times), more power will be generated and distributed

locally.

In the same way that cloud computing and smartphones have revolutionized how consumers get and store

information, smaller-scale generation and storage devices throughout the grid will make the system more

efficient and resilient, Mr. Kauffman said.

Although energy use is projected to flatten or decrease in the next decade, thanks in part to more efficient

appliances and better insulated buildings, peak demand will continue to grow, according to Nyiso.

Mr. Kauffman said focusing on reducing demand on the system, especially at peak times, would be crucial to

meeting New York’s clean energy goals. The state is using financing and competitions as incentives for the

private sector to develop sensors and software to make transmission more efficient, batteries that will make

better use of renewable energy, or “smart appliances,” like washing machines or dishwashers that will delay a

cycle until demand is lower, like the middle of the night.

Central to this transformation is overhauling the rules governing utilities. Mr. Kauffman compared the utilities to

the hotel industry, which has been disrupted by upstarts like Airbnb. Traditionally, utilities have been largely

indifferent to how much power customers consume. They receive a fixed rate of return (9 percent in 2016) on

the infrastructure they build and their cost to upgrade and maintain networks.

But the state is seeking to create ways for utilities to make money by teaming up with companies and

customers to install software solutions to control electricity use or to add solar panels more affordably, instead

of building billion-dollar substations. Ultimately, consumers will have more choices about where and how their

power is made and how it’s consumed.

But as more people create their own power and use less from their utility, because of the way electricity rates

are structured a smaller percentage of consumers could end up paying more to build and maintain

transmission wires and equipment.

Audrey Zibelman, the departing chairwoman of the New York Public Service Commission, which sets

consumer rates, said moving toward a system that reduced carbon emissions did not necessarily mean higher

costs. “It actually means lower prices if we do it right,” Ms. Zibelman said.

The state has promised that the poorest New Yorkers will pay no more than 6 percent of their household

income on energy costs, and it also plans to spend about $1 billion to make rooftop and community solar

installations more accessible and affordable.

Staten Island, giving customers detailed summaries about consumption and helping operators diagnose

problems without dispatching a truck.

To help finance the $1.3 billion project and to modernize its distribution networks, Con Ed requested a rate

increase, which the state approved in January. After a nearly five-year freeze, customers will see a raise of 2.3

percent to 2.4 percent in the next three years. A typical city resident who uses 300 kilowatt-hours per month

would see an increase from $78.52 to $80.30.

What’s Next?

Instead of moving power from large, central generating stations, where energy flows in only one direction and

about 5 percent vanishes in transit (more during peak times), more power will be generated and distributed

locally.

In the same way that cloud computing and smartphones have revolutionized how consumers get and store

information, smaller-scale generation and storage devices throughout the grid will make the system more

efficient and resilient, Mr. Kauffman said.

Although energy use is projected to flatten or decrease in the next decade, thanks in part to more efficient

appliances and better insulated buildings, peak demand will continue to grow, according to Nyiso.

Mr. Kauffman said focusing on reducing demand on the system, especially at peak times, would be crucial to

meeting New York’s clean energy goals. The state is using financing and competitions as incentives for the

private sector to develop sensors and software to make transmission more efficient, batteries that will make

better use of renewable energy, or “smart appliances,” like washing machines or dishwashers that will delay a

cycle until demand is lower, like the middle of the night.

Central to this transformation is overhauling the rules governing utilities. Mr. Kauffman compared the utilities to

the hotel industry, which has been disrupted by upstarts like Airbnb. Traditionally, utilities have been largely

indifferent to how much power customers consume. They receive a fixed rate of return (9 percent in 2016) on

the infrastructure they build and their cost to upgrade and maintain networks.

But the state is seeking to create ways for utilities to make money by teaming up with companies and

customers to install software solutions to control electricity use or to add solar panels more affordably, instead

of building billion-dollar substations. Ultimately, consumers will have more choices about where and how their

power is made and how it’s consumed.

But as more people create their own power and use less from their utility, because of the way electricity rates

are structured a smaller percentage of consumers could end up paying more to build and maintain

transmission wires and equipment.

Audrey Zibelman, the departing chairwoman of the New York Public Service Commission, which sets

consumer rates, said moving toward a system that reduced carbon emissions did not necessarily mean higher

costs. “It actually means lower prices if we do it right,” Ms. Zibelman said.

The state has promised that the poorest New Yorkers will pay no more than 6 percent of their household

income on energy costs, and it also plans to spend about $1 billion to make rooftop and community solar

installations more accessible and affordable.

New York is taking lessons from California, Germany and other clean energy pioneers.

“Building a modern energy infrastructure that’s clean and resilient,” Governor Cuomo said, “is critical to

attracting new investments and growing a green economy across New York, while helping us combat climate

change, maintain our air quality and keep our communities healthy for generations to come.”

Despite President Trump’s skepticism of climate change and support of the coal industry, the state says it will

forge ahead.

Mr. Kauffman said New York was enacting these policies “through its own authorities and is not reliant on the

federal government to advance our clean energy agenda.” Still, he said, reinventing a system that originated

more than a century ago will take time. “It is not flipping a switch,” he said.

“Building a modern energy infrastructure that’s clean and resilient,” Governor Cuomo said, “is critical to

attracting new investments and growing a green economy across New York, while helping us combat climate

change, maintain our air quality and keep our communities healthy for generations to come.”

Despite President Trump’s skepticism of climate change and support of the coal industry, the state says it will

forge ahead.

Mr. Kauffman said New York was enacting these policies “through its own authorities and is not reliant on the

federal government to advance our clean energy agenda.” Still, he said, reinventing a system that originated

more than a century ago will take time. “It is not flipping a switch,” he said.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 6

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.