Enhancing Crown Revenue: A Strategic Review of New Zealand Taxation

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/04

|6

|2192

|500

Report

AI Summary

This report analyzes strategies for enhancing revenue collection in New Zealand's taxation system. It proposes six key measures: raising tax rates for high-end taxpayers, taxing all types of income equally, raising estate tax, ending the step-up basis, implementing a financial transaction tax (FTT), and introducing a carbon tax. The report discusses the potential economic and social impacts of each measure, referencing various sources and comparing New Zealand's tax policies with those of other developed countries. It emphasizes the importance of sustainable, productive, and inclusive growth, and suggests that these measures can contribute to long-term fiscal sustainability by increasing Crown revenue and reducing net debt.

Page1

NEW ZEALAND TAXATION

Introduction

Apart from the most commonly used sources of revenue such as excise duty, estate tax,

several other taxes and fees, governments, especially in the developed world, use three

main sources of tax revenue, and these are Individual Income Taxes, Payroll Taxes and

Corporate Income Taxes. Every government prefers to change these Direct Taxes as

compared to the Indirect Taxes. In New Zealand, the total Crown revenue during the

concluded financial year was $76.1 billion. Tax revenue, which is one of the major

source of the Crown revenue totalled $70.4 billion during this period (CCH New

Zealand (ed), 2013).

Economic Strategy

The New Zealand government understands that for improving the living standards and

to maintain the well-bring of its citizens, it has to maintain sustainable, productive and

inclusive growth. This is possible through better productivity and wages.

Fiscal Strategy

Long-term sustainability of the economy can be ensured if revenue collection is raised

sufficiently to achieve the fiscal objectives. This should also ensure that net debt comes

down to below the current level of 20% of GDP within next five fiscal years (CCH New

Zealand (ed), 2013).

In this context, this paper proposes the following six measures for increasing the

revenue collection of the Crown.

1. Raising Tax Rates for High-end Taxpayer

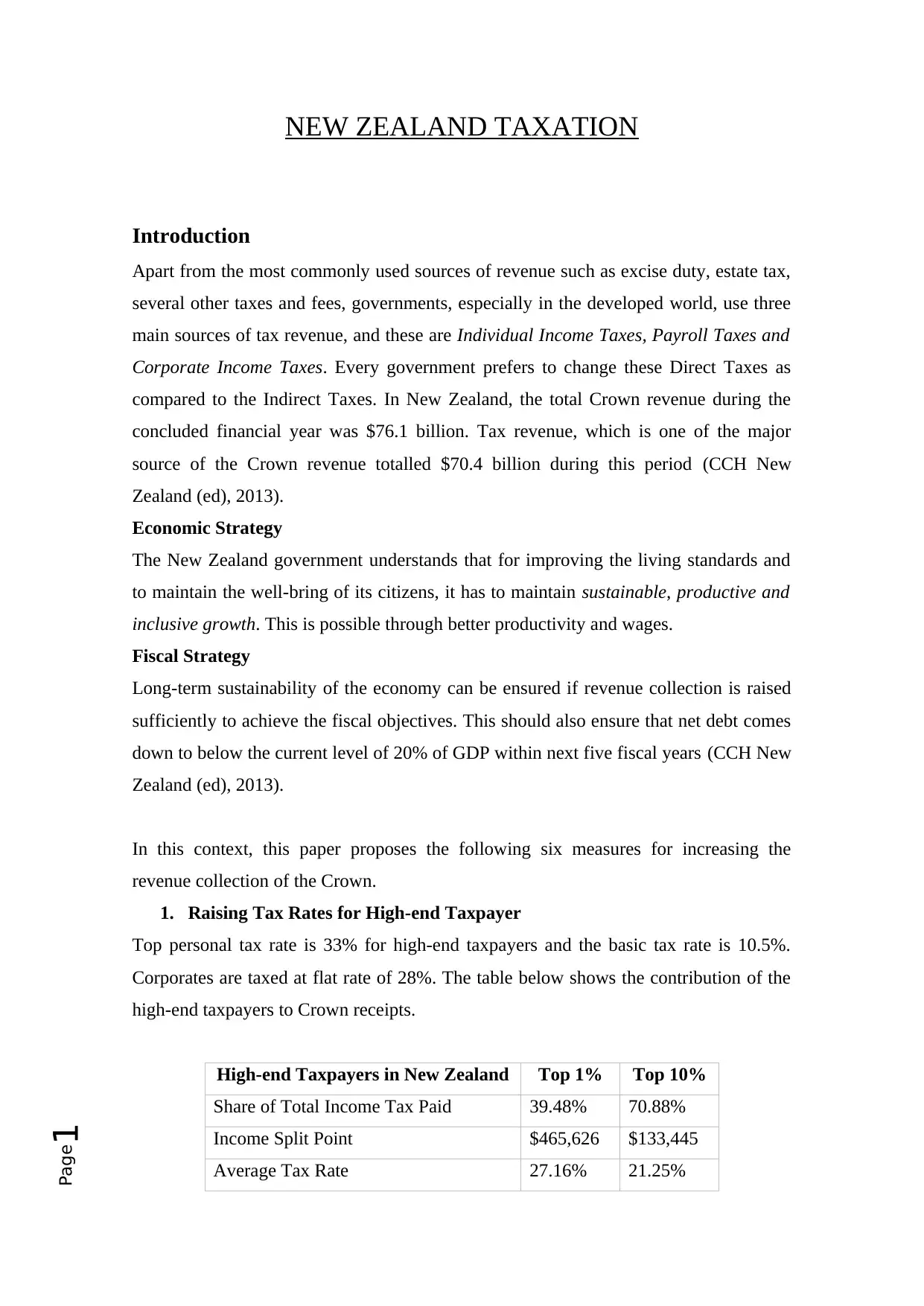

Top personal tax rate is 33% for high-end taxpayers and the basic tax rate is 10.5%.

Corporates are taxed at flat rate of 28%. The table below shows the contribution of the

high-end taxpayers to Crown receipts.

High-end Taxpayers in New Zealand Top 1% Top 10%

Share of Total Income Tax Paid 39.48% 70.88%

Income Split Point $465,626 $133,445

Average Tax Rate 27.16% 21.25%

NEW ZEALAND TAXATION

Introduction

Apart from the most commonly used sources of revenue such as excise duty, estate tax,

several other taxes and fees, governments, especially in the developed world, use three

main sources of tax revenue, and these are Individual Income Taxes, Payroll Taxes and

Corporate Income Taxes. Every government prefers to change these Direct Taxes as

compared to the Indirect Taxes. In New Zealand, the total Crown revenue during the

concluded financial year was $76.1 billion. Tax revenue, which is one of the major

source of the Crown revenue totalled $70.4 billion during this period (CCH New

Zealand (ed), 2013).

Economic Strategy

The New Zealand government understands that for improving the living standards and

to maintain the well-bring of its citizens, it has to maintain sustainable, productive and

inclusive growth. This is possible through better productivity and wages.

Fiscal Strategy

Long-term sustainability of the economy can be ensured if revenue collection is raised

sufficiently to achieve the fiscal objectives. This should also ensure that net debt comes

down to below the current level of 20% of GDP within next five fiscal years (CCH New

Zealand (ed), 2013).

In this context, this paper proposes the following six measures for increasing the

revenue collection of the Crown.

1. Raising Tax Rates for High-end Taxpayer

Top personal tax rate is 33% for high-end taxpayers and the basic tax rate is 10.5%.

Corporates are taxed at flat rate of 28%. The table below shows the contribution of the

high-end taxpayers to Crown receipts.

High-end Taxpayers in New Zealand Top 1% Top 10%

Share of Total Income Tax Paid 39.48% 70.88%

Income Split Point $465,626 $133,445

Average Tax Rate 27.16% 21.25%

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Page2

This paper is of the opinion that raising rates by 12 percentage point for the top 1%

taxpayers in the tax bracket will give, on a conservative estimate, an additional revenue

per year of $50 million. Tax Revenue in 2016 from Individuals was 3 billion per year,

of which 40% share of the top 1% was 1.2 billion. 12% increase in tax rate, from 27%

to 39%, will bring additional $50 million per year. Although wealthy taxpayers find

ways of reducing their liabilities to avoid higher rates, in my opinion, an increase of 12

percentage points can be a feasible increase which will not be circumvented by the high-

end taxpayers (CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed), 2013).

2. Do not Favour any one Type of Income

This paper believes the next recommendation for raising more revenue, in a transparent

and progressive way is to tax both, the individual and the corporate. Having already

touched individual taxpayers in step-1, this paper now discusses corporates. In this

segment, the most secretive and elusive segment is ‘Investment Income’, often referred

to as Capital Income (Scully & CAragata (ed), 2012). Highest tax bracket for Capital

Income is 20% (lowest being 0%) which is nearly half of the highest individual tax

bracket of 33%. Hence, it is not uncommon to expect the wealthy people adopting all

possible ways to define majority of what they earn as being earned from investments

and not as ordinary earnings (Littlewood & Elliffe (ed), 2017).

This is what Warren Buffett, world’s richest investor, has to say in support of this

measure: “I have worked with investors for 60 years and I have yet to see anyone—not

even when capital gains rates were 39.9 percent in 1976-77—shy away from a sensible

investment because of the tax rate on the potential gain. People invest to make money,

and potential taxes have never scared them off.”

Since the investment segment is concentrated largely among the wealthy, this measure

cannot propagate inequality among various segments of taxpayers. The most plausible

justification for this is that although investments are highly responsive to tax changes,

experts have not been able to provide evidence in support of their claim, as also has

been expressed by Mr. Buffett. Hence, it can be safely recommended that a small

change of a few percentage points would not make a noticeable effect on the investors

investing pattern (CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed), 2013).

This paper is of the opinion that raising rates by 12 percentage point for the top 1%

taxpayers in the tax bracket will give, on a conservative estimate, an additional revenue

per year of $50 million. Tax Revenue in 2016 from Individuals was 3 billion per year,

of which 40% share of the top 1% was 1.2 billion. 12% increase in tax rate, from 27%

to 39%, will bring additional $50 million per year. Although wealthy taxpayers find

ways of reducing their liabilities to avoid higher rates, in my opinion, an increase of 12

percentage points can be a feasible increase which will not be circumvented by the high-

end taxpayers (CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed), 2013).

2. Do not Favour any one Type of Income

This paper believes the next recommendation for raising more revenue, in a transparent

and progressive way is to tax both, the individual and the corporate. Having already

touched individual taxpayers in step-1, this paper now discusses corporates. In this

segment, the most secretive and elusive segment is ‘Investment Income’, often referred

to as Capital Income (Scully & CAragata (ed), 2012). Highest tax bracket for Capital

Income is 20% (lowest being 0%) which is nearly half of the highest individual tax

bracket of 33%. Hence, it is not uncommon to expect the wealthy people adopting all

possible ways to define majority of what they earn as being earned from investments

and not as ordinary earnings (Littlewood & Elliffe (ed), 2017).

This is what Warren Buffett, world’s richest investor, has to say in support of this

measure: “I have worked with investors for 60 years and I have yet to see anyone—not

even when capital gains rates were 39.9 percent in 1976-77—shy away from a sensible

investment because of the tax rate on the potential gain. People invest to make money,

and potential taxes have never scared them off.”

Since the investment segment is concentrated largely among the wealthy, this measure

cannot propagate inequality among various segments of taxpayers. The most plausible

justification for this is that although investments are highly responsive to tax changes,

experts have not been able to provide evidence in support of their claim, as also has

been expressed by Mr. Buffett. Hence, it can be safely recommended that a small

change of a few percentage points would not make a noticeable effect on the investors

investing pattern (CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed), 2013).

Page3

3. Raise Estate Tax

A common phrase with regard to wealth and death is that one cannot take them when

departing from this mortal world. When one considers hard economic facts of a country,

it is not difficult to understand that the current estate-tax base in most of the developed

countries is so narrow that in New Zealand the IRS gets hardly any substantial revenue

from Estate Tax (Lymer & Hasseldine (ed), 2012). Thus, this paper has recommended

that New Zealand’s IRS should start broadening its base of Estate Tax. Currently not

more than 0.2 percent of the estates in New Zealand are covered under the Estate Tax

and that amounts to about 2 out of every 1,000 people who die and become eligible for

Estate Tax. However, say(James, Sawyer & Budak (ed), 2016), it is worth noting that

this tax has not only proven as a progressive revenue-raiser, it can also help in pushing

back immobility in economic matters. There are a large number of New Zealand

resident taxpayers who are born with the advantage doled to them because of laxity of

IRS in broadening the base of Estate Tax (Ganghof, 2006).

4. Ending the Step-up Basis

In line with the recommendation given in Step-3 for enhancing the base of Estate Tax, it

is worth noting that IRS is targeting the heirs very narrowly because of the loopholes in

the Tax Avoidance measures and this allows the wealthy in passing on the taxable

capital gains, without paying any Capital Gains Tax on the Capital Assets, to their heirs.

A simple calculation process can explain this economic anomaly (Ganghof, 2006).

Suppose John, on his death, leaves a property to one of his sons that he had bought a

decade ago for $10,000. The Capital Asset has a worth of $100,000 at the time of John’s

death. If John had sold this capital Asset before his death, he would have paid Capital

Gains Taxes, at the prevailing rates, on the Capital Gain of $90,000 which he would

have made because of the appreciation in the value of the property (Scully & Caragata

(ed), 2012). Since John had passed the Capital Asset on to his son, his heir, the

appreciation of $90,000 is also passed on untaxed. Under the taxation laws, the Capital

Asset shall be treated as if John’s son had bought it for $100,000. This paper is of the

opinion that the transaction does not have an economic rationale to explain this

loophole. Rather, because of this loophole, such Capital Assets enjoy a lock-in effect.

The owner finds an incentive in holding onto the Capital Asset till death, before

bequeathing it to an heir (Ganghof, 2006).

3. Raise Estate Tax

A common phrase with regard to wealth and death is that one cannot take them when

departing from this mortal world. When one considers hard economic facts of a country,

it is not difficult to understand that the current estate-tax base in most of the developed

countries is so narrow that in New Zealand the IRS gets hardly any substantial revenue

from Estate Tax (Lymer & Hasseldine (ed), 2012). Thus, this paper has recommended

that New Zealand’s IRS should start broadening its base of Estate Tax. Currently not

more than 0.2 percent of the estates in New Zealand are covered under the Estate Tax

and that amounts to about 2 out of every 1,000 people who die and become eligible for

Estate Tax. However, say(James, Sawyer & Budak (ed), 2016), it is worth noting that

this tax has not only proven as a progressive revenue-raiser, it can also help in pushing

back immobility in economic matters. There are a large number of New Zealand

resident taxpayers who are born with the advantage doled to them because of laxity of

IRS in broadening the base of Estate Tax (Ganghof, 2006).

4. Ending the Step-up Basis

In line with the recommendation given in Step-3 for enhancing the base of Estate Tax, it

is worth noting that IRS is targeting the heirs very narrowly because of the loopholes in

the Tax Avoidance measures and this allows the wealthy in passing on the taxable

capital gains, without paying any Capital Gains Tax on the Capital Assets, to their heirs.

A simple calculation process can explain this economic anomaly (Ganghof, 2006).

Suppose John, on his death, leaves a property to one of his sons that he had bought a

decade ago for $10,000. The Capital Asset has a worth of $100,000 at the time of John’s

death. If John had sold this capital Asset before his death, he would have paid Capital

Gains Taxes, at the prevailing rates, on the Capital Gain of $90,000 which he would

have made because of the appreciation in the value of the property (Scully & Caragata

(ed), 2012). Since John had passed the Capital Asset on to his son, his heir, the

appreciation of $90,000 is also passed on untaxed. Under the taxation laws, the Capital

Asset shall be treated as if John’s son had bought it for $100,000. This paper is of the

opinion that the transaction does not have an economic rationale to explain this

loophole. Rather, because of this loophole, such Capital Assets enjoy a lock-in effect.

The owner finds an incentive in holding onto the Capital Asset till death, before

bequeathing it to an heir (Ganghof, 2006).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Page4

5. Financial Transaction Tax

Closing loopholes to control Tax Avoidance is a tedious task for IRS and the next

recommendation can be cake-walk for the authorities: Imposing a very small tax on all

the securities traded. Already being enforced in many countries, Financial Transaction

Tax (FTT) has a very large base, much bigger than GST but comparatively simpler than

GST (CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed), 2013). Trillions worth of securities are being traded

every year and a small FTT, can raise millions for the Treasury. A one-basis-point of

tax on just $1,000 worth of stock traded will cost the stock trader $1; a $100,000 of

trade will generate a tax of just $10. But the magnitude of transactions being done will

raise $2 billion in a year (CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed), 2013).

GST effects those taxpayers who are in the low and middle income brackets. In

comparison, FTT will impact only those who are currency speculators and other

financial wheeler-dealers who gamble with the wealth created by others. Because of its

broad base, FTT can collect more revenue for the government and will not hurt the low

and middle income earners(CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed), 2013). GST collects 31.4% of

the total tax revenue and has made New Zealand the highest taxed country in OECD if

sales tax revenue is taken as a proportion of the country’s GDP. GST, effective in New

Zealand since 1 October 2010 is levied at the rate of 15%. Compared to this, the

proposed FTT will not be more than 0.01% without altering the final price of the

products or services being traded in the markets (CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed), 2013).

6. Carbon Tax

This recommendation is both essential and obvious. Essential because the planet is

deteriorating day-by-day and obvious because the coming generations will not be able

to survive in this dying planet (Littlewood & Elliffe (ed), 2017). It may raise cost of

living for the non-rich people, but it will make their life more comfortable. Many of

these taxes come with a rebate for the low-income taxpayers who spend major portion

of their income on buying energy. Carbon Tax in fact is a tax on pollution. It is levied

as a fee on the distribution and production, as well as use of fossil fuels and is levied on

the quantum of carbon emitted by their combustion (James, Sawyer & Budak (ed),

2016).

5. Financial Transaction Tax

Closing loopholes to control Tax Avoidance is a tedious task for IRS and the next

recommendation can be cake-walk for the authorities: Imposing a very small tax on all

the securities traded. Already being enforced in many countries, Financial Transaction

Tax (FTT) has a very large base, much bigger than GST but comparatively simpler than

GST (CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed), 2013). Trillions worth of securities are being traded

every year and a small FTT, can raise millions for the Treasury. A one-basis-point of

tax on just $1,000 worth of stock traded will cost the stock trader $1; a $100,000 of

trade will generate a tax of just $10. But the magnitude of transactions being done will

raise $2 billion in a year (CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed), 2013).

GST effects those taxpayers who are in the low and middle income brackets. In

comparison, FTT will impact only those who are currency speculators and other

financial wheeler-dealers who gamble with the wealth created by others. Because of its

broad base, FTT can collect more revenue for the government and will not hurt the low

and middle income earners(CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed), 2013). GST collects 31.4% of

the total tax revenue and has made New Zealand the highest taxed country in OECD if

sales tax revenue is taken as a proportion of the country’s GDP. GST, effective in New

Zealand since 1 October 2010 is levied at the rate of 15%. Compared to this, the

proposed FTT will not be more than 0.01% without altering the final price of the

products or services being traded in the markets (CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed), 2013).

6. Carbon Tax

This recommendation is both essential and obvious. Essential because the planet is

deteriorating day-by-day and obvious because the coming generations will not be able

to survive in this dying planet (Littlewood & Elliffe (ed), 2017). It may raise cost of

living for the non-rich people, but it will make their life more comfortable. Many of

these taxes come with a rebate for the low-income taxpayers who spend major portion

of their income on buying energy. Carbon Tax in fact is a tax on pollution. It is levied

as a fee on the distribution and production, as well as use of fossil fuels and is levied on

the quantum of carbon emitted by their combustion (James, Sawyer & Budak (ed),

2016).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Page5

New Zealand needs a strategy for this tax. 46% of New Zealand’s current population of

4.8 million people is urban. Co2 emissions per capita for New Zealand is 7.14 metric

tons. At $15, Carbon Tax collections can be 50 million per year. New Zealand has two

main options to help both businesses and consumers in reducing the emissions. First

option is an Emissions Trading Scheme and New Zealand is currently promoting this.

The second option is the 'Carbon Tax' which should be promoted by taxing Carbon

Dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions (CCH New Zealand (ed), 2013).

LIST OF REFERENCES

CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed). (2013) New Zealand Goods and Services Tax Legislation

(2013 edition). Auckland: CCH New Zealand Limited.

CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed). (2013) New Zealand Income Tax Act 2007 (2013 edition).

Auckland: CCH New Zealand Limited.

CCH New Zealand (ed). (2013) New Zealand Master Tax Guide (2013 edition).

Auckland: CCH New Zealand Limited.

CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed). (2013) New Zealand Tax Regulations and Determinations

(2013 edition). Auckland: CCH New Zealand Limited.

Ganghof, S. (2006) The Politics of Income Taxation: A Comparative Analysis.

Colchester: ECPR Press.

James, S., Sawyer, A. and Budak, T. (ed). (2016) The Complexity of Tax Simplification:

Experiences From Around the World. Hampshire: Springer.

New Zealand needs a strategy for this tax. 46% of New Zealand’s current population of

4.8 million people is urban. Co2 emissions per capita for New Zealand is 7.14 metric

tons. At $15, Carbon Tax collections can be 50 million per year. New Zealand has two

main options to help both businesses and consumers in reducing the emissions. First

option is an Emissions Trading Scheme and New Zealand is currently promoting this.

The second option is the 'Carbon Tax' which should be promoted by taxing Carbon

Dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions (CCH New Zealand (ed), 2013).

LIST OF REFERENCES

CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed). (2013) New Zealand Goods and Services Tax Legislation

(2013 edition). Auckland: CCH New Zealand Limited.

CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed). (2013) New Zealand Income Tax Act 2007 (2013 edition).

Auckland: CCH New Zealand Limited.

CCH New Zealand (ed). (2013) New Zealand Master Tax Guide (2013 edition).

Auckland: CCH New Zealand Limited.

CCH New Zealand Ltd (ed). (2013) New Zealand Tax Regulations and Determinations

(2013 edition). Auckland: CCH New Zealand Limited.

Ganghof, S. (2006) The Politics of Income Taxation: A Comparative Analysis.

Colchester: ECPR Press.

James, S., Sawyer, A. and Budak, T. (ed). (2016) The Complexity of Tax Simplification:

Experiences From Around the World. Hampshire: Springer.

Page6

Littlewood, M. and Elliffe, C. (ed). (2017) Capital Gains Taxation: A Comparative

Analysis of Key Issues. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Lymer, A. and Hasseldine, J. (ed). (2012) The International Taxation System. New

York: Springer Science & Business Media.

Scully, G.W. and Caragata, P.J. (ed). (2012) Taxation and the Limits of Government.

New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

Littlewood, M. and Elliffe, C. (ed). (2017) Capital Gains Taxation: A Comparative

Analysis of Key Issues. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Lymer, A. and Hasseldine, J. (ed). (2012) The International Taxation System. New

York: Springer Science & Business Media.

Scully, G.W. and Caragata, P.J. (ed). (2012) Taxation and the Limits of Government.

New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 6

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.