Overview of Notifiable Infectious Diseases in Australia, 1991-2011

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/14

|15

|9110

|411

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive overview of the epidemiology of notifiable infectious diseases in Australia from 1991 to 2011, based on the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS). The study analyzed 2,421,134 cases across various disease groups, jurisdictions, Indigenous status, age groups, and notification years. Key findings reveal that chlamydial infection, campylobacteriosis, varicella zoster, hepatitis C, influenza, pertussis, salmonellosis, hepatitis B, gonococcal infection, and Ross River virus infection comprised 88% of all notifications. The analysis highlights increasing notification incidence, particularly for sexually transmissible infections and vaccine-preventable diseases, and identifies populations with higher incidence requiring targeted public health interventions. The report emphasizes the importance of surveillance in public health efforts, discusses the limitations of the data, and provides valuable insights for future public health strategies in Australia, including the need for tailored interventions based on high-risk behaviors, food safety, and immunization programs.

An overview of the epidemiology of notifiable infectious diseases

in Australia, 1991–2011

K. B. GIBNEY*, A. C. CHENG, R. HALL AND K. LEDER

Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, The Alfred Centre, Melbourne,

Victoria, Australia

Received 24 February 2016; Final revision 28 April 2016; Accepted 5 May 2016;

first published online 22 June 2016

SUMMARY

We reviewed the first 21 years (1991–2011) of Australia’s National Notifiable Diseases

Surveillance System (NNDSS). All nationally notified diseases (except HIV/AIDS and

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease) were analysed by disease group (n = 8), jurisdiction (six states

and two territories), Indigenous status, age group and notification year. In total, 2 421 134

cases were analysed. The 10 diseases with highest notification incidence (chlamydial infection,

campylobacteriosis, varicella zoster, hepatitis C, influenza, pertussis, salmonellosis, hepatitis B,

gonococcal infection, and Ross River virus infection) comprised 88% of all notifications. Annual

notification incidence was 591 cases/100 000, highest in the Northern Territory (2598/100 000) and

in children aged <5 years (698/100 000). A total of 8·4% of cases were Indigenous Australians.

Notification incidence increased by 6·4% per year (12% for sexually transmissible infections and

15% for vaccine-preventable diseases). The number of notifiable diseases also increased from 37

to 65. The number and incidence of notifications increased throughout the study period, partly

due to addition of diseases to the NNDSS and increasing availability of sensitive diagnostic tests.

The most commonly notified diseases require a range of public health responses addressing high-

risk sexual and drug-use behaviours, food safety and immunization. Our results highlight

populations with higher notification incidence that might require tailored public health

interventions.

Key words: Analysis of data, Australia, epidemiology, public health, surveillance system.

INTRODUCTION

Surveillance is the cornerstone of public health efforts

to minimize morbidity and mortality resulting from

preventable infectious diseases. Infectious disease sur-

veillance wasinstrumentalin smallpox eradication

and in current efforts towards global polio eradication

and measleselimination.National surveillance sys-

tems allow examination of the epidemiological

profile of important infections at a country leveland

provide oversight to ensure consistent reporting across

jurisdictions [1].

In Australia,notification of selected infectious dis-

eases is required by public health legislation in the

six statesand two territories.Each jurisdiction

definesits own notification listand receivesdata

from doctors and/or laboratories. Primary responsibil-

ity for public health action lies with the state/territory

health departments. Jurisdictions forward de-identified

* Author for correspondence: Dr K. B. Gibney, The Peter Doherty

Institute for Infection and Immunity, 792 Elizabeth Street,

Melbourne 3000 Victoria, Australia.

(Email: Katherine.Gibney@unimelb.edu.au)

Epidemiol. Infect. (2016), 144, 3263–3277.© Cambridge University Press 2016

doi:10.1017/S0950268816001072

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

in Australia, 1991–2011

K. B. GIBNEY*, A. C. CHENG, R. HALL AND K. LEDER

Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, The Alfred Centre, Melbourne,

Victoria, Australia

Received 24 February 2016; Final revision 28 April 2016; Accepted 5 May 2016;

first published online 22 June 2016

SUMMARY

We reviewed the first 21 years (1991–2011) of Australia’s National Notifiable Diseases

Surveillance System (NNDSS). All nationally notified diseases (except HIV/AIDS and

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease) were analysed by disease group (n = 8), jurisdiction (six states

and two territories), Indigenous status, age group and notification year. In total, 2 421 134

cases were analysed. The 10 diseases with highest notification incidence (chlamydial infection,

campylobacteriosis, varicella zoster, hepatitis C, influenza, pertussis, salmonellosis, hepatitis B,

gonococcal infection, and Ross River virus infection) comprised 88% of all notifications. Annual

notification incidence was 591 cases/100 000, highest in the Northern Territory (2598/100 000) and

in children aged <5 years (698/100 000). A total of 8·4% of cases were Indigenous Australians.

Notification incidence increased by 6·4% per year (12% for sexually transmissible infections and

15% for vaccine-preventable diseases). The number of notifiable diseases also increased from 37

to 65. The number and incidence of notifications increased throughout the study period, partly

due to addition of diseases to the NNDSS and increasing availability of sensitive diagnostic tests.

The most commonly notified diseases require a range of public health responses addressing high-

risk sexual and drug-use behaviours, food safety and immunization. Our results highlight

populations with higher notification incidence that might require tailored public health

interventions.

Key words: Analysis of data, Australia, epidemiology, public health, surveillance system.

INTRODUCTION

Surveillance is the cornerstone of public health efforts

to minimize morbidity and mortality resulting from

preventable infectious diseases. Infectious disease sur-

veillance wasinstrumentalin smallpox eradication

and in current efforts towards global polio eradication

and measleselimination.National surveillance sys-

tems allow examination of the epidemiological

profile of important infections at a country leveland

provide oversight to ensure consistent reporting across

jurisdictions [1].

In Australia,notification of selected infectious dis-

eases is required by public health legislation in the

six statesand two territories.Each jurisdiction

definesits own notification listand receivesdata

from doctors and/or laboratories. Primary responsibil-

ity for public health action lies with the state/territory

health departments. Jurisdictions forward de-identified

* Author for correspondence: Dr K. B. Gibney, The Peter Doherty

Institute for Infection and Immunity, 792 Elizabeth Street,

Melbourne 3000 Victoria, Australia.

(Email: Katherine.Gibney@unimelb.edu.au)

Epidemiol. Infect. (2016), 144, 3263–3277.© Cambridge University Press 2016

doi:10.1017/S0950268816001072

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

notificationdata for casesmeetingnational case

definitionsfor diseaseson the National Notifiable

DiseasesList (NNDL) to the National Notifiable

Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS), a passive sur-

veillance system operational since 1991.

A summary ofnationalnotifiable disease surveil-

lance data from 1917 to 1991 highlighted the lack of

consistency,detail,and methodicalreporting ofna-

tionally notifiable diseases before the introduction of

the NNDSS [2]. Annual reportsof NNDSS data

have been produced since 1991;however,trend ana-

lysis of all nationally notifiable diseases has not previ-

ously been performed. We present an overview of the

epidemiology ofall notifiable infectiousdiseasesin

Australia [excludingHIV/AIDS and Creutzfeldt–

Jakob disease (CJD)]during the first 21 years of the

NNDSS, with a view to highlighting diseasesand

population groups with greatest need of public health

intervention to reduce disease incidence.

METHODS

All case notifications of nationally notifiable diseases

to the NNDSS from 1 January 1991 to 31 December

2011 were analysed according to their diagnosis date

[3]. HIV/AIDS and CJD are under different national

surveillancesystemsand were excluded from this

analysis[4]. Notificationswere reported by disease

and categorized into eight disease groups (as per the

NNDL) based on mode of acquisitionand/or

public health strategiesfor controland prevention:

bloodborne viralhepatitis (BBVH),gastrointestinal,

other bacterial,quarantinable,sexually transmissible

infections (STIs), vector-bornediseases(VBDs),

vaccine-preventablediseases(VPDs), and zoonotic

diseases.Diseasesincluded in each group and the

year they becamenotifiableare summarizedin

Table 1. NNDSS diseases were analysed by pathogen

for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, rubella, syphilis, and vari-

cella zoster.

We report the numberand annualincidence of

notified cases nationally and by jurisdiction.For all-

causeand disease-group incidencecalculations,all

notified cases were included and Australian Bureau

of Statistics (ABS)population estimates at30 June

for each study yearwere used [5].Data from the

Northern Territory (NT)were excluded from both

the numerator (number of cases notified) and denom-

inator (population) of incidence calculations for 1994

due to large discrepancies between the study dataset

(extracted in 2012)and online (live)NNDSS data

that has undergone subsequent data cleaning [6]. For

disease-specific incidence calculations,diseases notifi-

able both nationally and in thatjurisdiction were

included (Table 1) with the exceptions of hepatitis B

and C (Victoria 1991–1997),hepatitisB [South

Australian (SA) 1991–1995],tuberculosis(Victoria

1991),and varicella zoster (Victoria 2006–2007) due

to discrepancies with online NNDSS data; the denom-

inator comprisedthe combinedpopulationsfor

included years and jurisdictions.Relative risks (RRs)

were calculated for univariate comparison of notifica-

tion incidence between study sub-periods (1991–1997,

1998–2004, 2005–2011), age groups (<5, 5–19, 20–64,

65–98 years) and jurisdictions for diseases with >400

notifications during the 21-year study period.Three

sub-periods were selected to allow more meaningful

comparison between disease groups/diseases within a

sub-period as well as analysis of change in notification

incidence across these sub-periods for a single disease

or disease group.

Average changesin annualnotification incidence

over the study period were investigated by Poisson re-

gression forall diseasescombined and by disease

group from 1991 to 2011;for individual diseases this

calculation was confined to years the disease was na-

tionally notifiable.Tests for statisticalsignificance

were notperformed aspopulation-based data were

used. To allow international comparison, age-standar-

dized incidence rates were calculated using the WHO

world standard population distribution [7].

Incidence ratesfor Aboriginaland TorresStrait

Islander(‘Indigenous’)Australianswere calculated

for the three jurisdictions reporting Indigenous status

for >75% ofnotified cases[NT, SA, and Western

Australia (WA)] using ABS populationestimates

[8, 9]; cases with unknown Indigenous status were pre-

sumed non-Indigenous.

NNDSS data were provided by the Australian

Government’s Office of Health Protection on behalf

of CommunicableDiseases Network Australia

(CDNA) jurisdictionalmembersin March 2012 as

an extract from the national data file.

Ethical considerations

The projectwas approved by the Monash Human

ResearchEthics Committee(project no. CF11/

2357–201) and CDNA jurisdictionalmembers.Data

were analysed using Stata v.12 (StataCorp.,USA).

This work did not involve human or animal

experimentation.

3264 K. B. Gibney and others

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

definitionsfor diseaseson the National Notifiable

DiseasesList (NNDL) to the National Notifiable

Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS), a passive sur-

veillance system operational since 1991.

A summary ofnationalnotifiable disease surveil-

lance data from 1917 to 1991 highlighted the lack of

consistency,detail,and methodicalreporting ofna-

tionally notifiable diseases before the introduction of

the NNDSS [2]. Annual reportsof NNDSS data

have been produced since 1991;however,trend ana-

lysis of all nationally notifiable diseases has not previ-

ously been performed. We present an overview of the

epidemiology ofall notifiable infectiousdiseasesin

Australia [excludingHIV/AIDS and Creutzfeldt–

Jakob disease (CJD)]during the first 21 years of the

NNDSS, with a view to highlighting diseasesand

population groups with greatest need of public health

intervention to reduce disease incidence.

METHODS

All case notifications of nationally notifiable diseases

to the NNDSS from 1 January 1991 to 31 December

2011 were analysed according to their diagnosis date

[3]. HIV/AIDS and CJD are under different national

surveillancesystemsand were excluded from this

analysis[4]. Notificationswere reported by disease

and categorized into eight disease groups (as per the

NNDL) based on mode of acquisitionand/or

public health strategiesfor controland prevention:

bloodborne viralhepatitis (BBVH),gastrointestinal,

other bacterial,quarantinable,sexually transmissible

infections (STIs), vector-bornediseases(VBDs),

vaccine-preventablediseases(VPDs), and zoonotic

diseases.Diseasesincluded in each group and the

year they becamenotifiableare summarizedin

Table 1. NNDSS diseases were analysed by pathogen

for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, rubella, syphilis, and vari-

cella zoster.

We report the numberand annualincidence of

notified cases nationally and by jurisdiction.For all-

causeand disease-group incidencecalculations,all

notified cases were included and Australian Bureau

of Statistics (ABS)population estimates at30 June

for each study yearwere used [5].Data from the

Northern Territory (NT)were excluded from both

the numerator (number of cases notified) and denom-

inator (population) of incidence calculations for 1994

due to large discrepancies between the study dataset

(extracted in 2012)and online (live)NNDSS data

that has undergone subsequent data cleaning [6]. For

disease-specific incidence calculations,diseases notifi-

able both nationally and in thatjurisdiction were

included (Table 1) with the exceptions of hepatitis B

and C (Victoria 1991–1997),hepatitisB [South

Australian (SA) 1991–1995],tuberculosis(Victoria

1991),and varicella zoster (Victoria 2006–2007) due

to discrepancies with online NNDSS data; the denom-

inator comprisedthe combinedpopulationsfor

included years and jurisdictions.Relative risks (RRs)

were calculated for univariate comparison of notifica-

tion incidence between study sub-periods (1991–1997,

1998–2004, 2005–2011), age groups (<5, 5–19, 20–64,

65–98 years) and jurisdictions for diseases with >400

notifications during the 21-year study period.Three

sub-periods were selected to allow more meaningful

comparison between disease groups/diseases within a

sub-period as well as analysis of change in notification

incidence across these sub-periods for a single disease

or disease group.

Average changesin annualnotification incidence

over the study period were investigated by Poisson re-

gression forall diseasescombined and by disease

group from 1991 to 2011;for individual diseases this

calculation was confined to years the disease was na-

tionally notifiable.Tests for statisticalsignificance

were notperformed aspopulation-based data were

used. To allow international comparison, age-standar-

dized incidence rates were calculated using the WHO

world standard population distribution [7].

Incidence ratesfor Aboriginaland TorresStrait

Islander(‘Indigenous’)Australianswere calculated

for the three jurisdictions reporting Indigenous status

for >75% ofnotified cases[NT, SA, and Western

Australia (WA)] using ABS populationestimates

[8, 9]; cases with unknown Indigenous status were pre-

sumed non-Indigenous.

NNDSS data were provided by the Australian

Government’s Office of Health Protection on behalf

of CommunicableDiseases Network Australia

(CDNA) jurisdictionalmembersin March 2012 as

an extract from the national data file.

Ethical considerations

The projectwas approved by the Monash Human

ResearchEthics Committee(project no. CF11/

2357–201) and CDNA jurisdictionalmembers.Data

were analysed using Stata v.12 (StataCorp.,USA).

This work did not involve human or animal

experimentation.

3264 K. B. Gibney and others

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

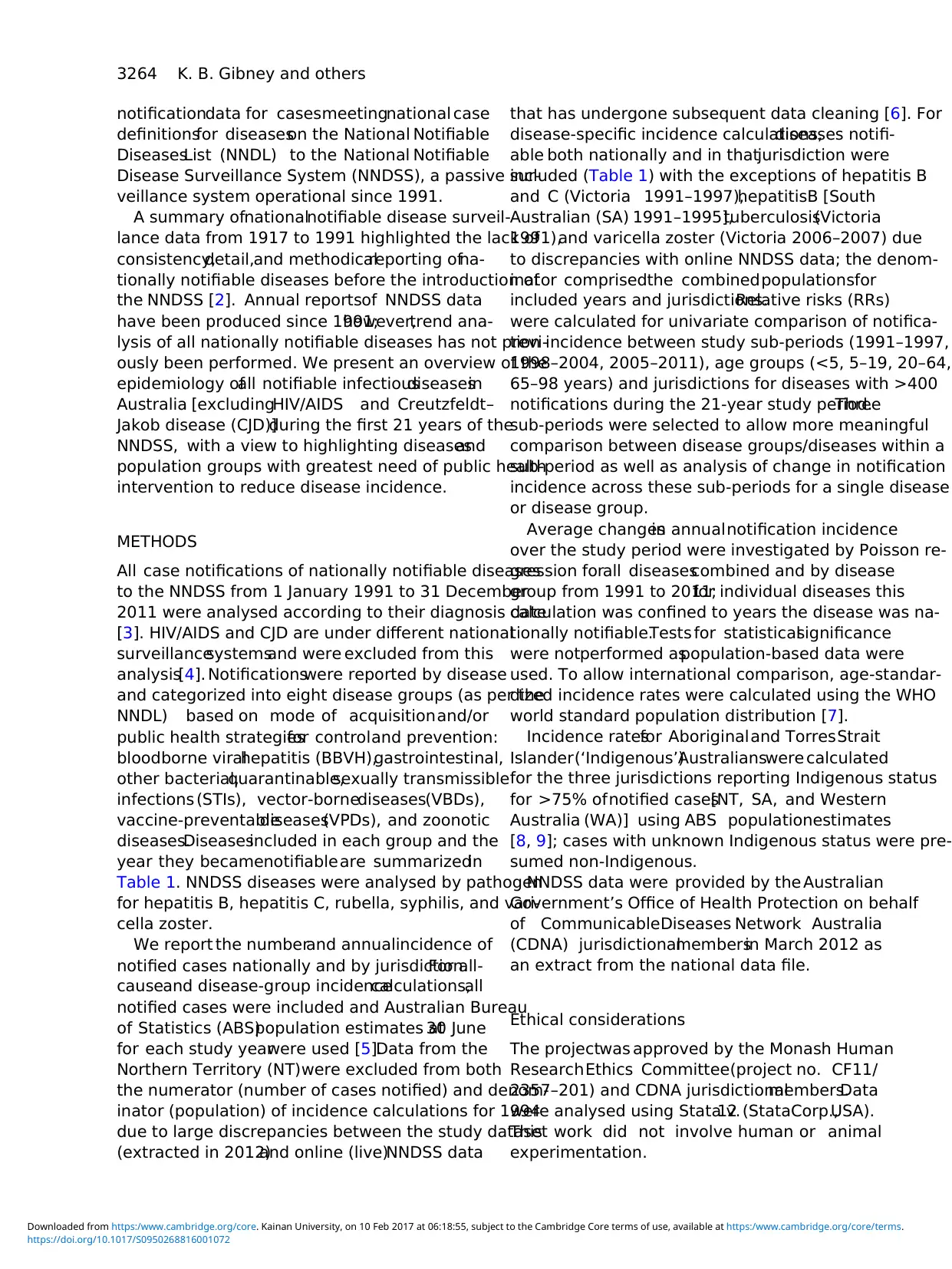

Table 1.Diseases included in the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) by disease group a

year introduced, Australia 1991–2011

Year* Variation by jurisdiction

Bloodborne viral hepatitis

Hepatitis B (newly acquired) 1993 1994 in Qld and WA, 1995 in ACT

Hepatitis B (unspecified) 1991 2005 in NT

Hepatitis C (newly acquired) 1993 1995 in ACT, Tas and WA, 2005 in NT, not notifiable in Qld

Hepatitis C (unspecified) 1995 Included incident cases until hepatitis C newly acquired introduced

Hepatitis D 1999 2002 in WA

Hepatitis (NEC) 1991 2001 in WA. Included reports of hepatitis D and E 1991–1998

Gastrointestinal diseases

Botulism 1992 1993 in SA, 1998 in NT and NSW, 2001 in WA

Campylobacteriosis 1991† Not notifiable in NSW

Cryptosporidiosis 2001

Haemolytic uraemic syndrome 1999

Hepatitis A 1991†

Hepatitis E 1999 2001 in WA

Listeriosis 1991 1992 in SA, 1994 in NT

Salmonellosis (non typhoidal) 1991†

Shiga-/Vero-toxin-producing E. coli 1999 2001 in Qld and WA

Shigellosis 1991 2001 in NSW

Typhoid fever 1991† Includes paratyphoid in NSW, Qld and Vic

Quarantinable diseases

Cholera 1991†

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (human)2004 Reported under influenza in WA

Plague 1991†

Rabies 1991 1993 in ACT, 1997 in NSW

Severe acute respiratory syndrome 2003

Smallpox 2004

Viral haemorrhagic fever 1991 1993 in ACT

Yellow fever 1991†

Sexually transmissible infections

Chancroid 1991 No longer nationally notifiable from 2000

Chlamydial infection 1994 1999 in NSW

Donovanosis 1991 1993 in Tas, 2002 in NSW and SA

Gonococcal infection 1991†

Syphilis 1991 Includes syphilis <2 and >2 years/unknown duration to 2004

Syphilis (<2 years duration) 2004

Syphilis (>2 years or unknown duration)2004 Not reported in SA

Syphilis (congenital) 1991†

Vaccine-preventable diseases

Diphtheria 1991†

Haemophilus influenzae type b 1991 1994 in WA

Influenza (laboratory confirmed) 2001 2008 in SA

Measles 1991†

Mumps 1995 Not reported by Qld in 1995–96, 1999–2000

Pertussis 1991†

Pneumococcal disease (invasive) 2001

Poliomyelitis 1991†

Rubella 1993 1995 in Tas

Rubella (congenital) 1991†

Tetanus 1991 1994 in Qld

Varicella zoster (chickenpox) 2006 Not notifiable in NSW

Varicella zoster (shingles) 2006 Not notifiable in NSW

Varicella zoster (unspecified) 2006 Not notifiable in NSW

Notifiable diseases, Australia 1991–20113265

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

year introduced, Australia 1991–2011

Year* Variation by jurisdiction

Bloodborne viral hepatitis

Hepatitis B (newly acquired) 1993 1994 in Qld and WA, 1995 in ACT

Hepatitis B (unspecified) 1991 2005 in NT

Hepatitis C (newly acquired) 1993 1995 in ACT, Tas and WA, 2005 in NT, not notifiable in Qld

Hepatitis C (unspecified) 1995 Included incident cases until hepatitis C newly acquired introduced

Hepatitis D 1999 2002 in WA

Hepatitis (NEC) 1991 2001 in WA. Included reports of hepatitis D and E 1991–1998

Gastrointestinal diseases

Botulism 1992 1993 in SA, 1998 in NT and NSW, 2001 in WA

Campylobacteriosis 1991† Not notifiable in NSW

Cryptosporidiosis 2001

Haemolytic uraemic syndrome 1999

Hepatitis A 1991†

Hepatitis E 1999 2001 in WA

Listeriosis 1991 1992 in SA, 1994 in NT

Salmonellosis (non typhoidal) 1991†

Shiga-/Vero-toxin-producing E. coli 1999 2001 in Qld and WA

Shigellosis 1991 2001 in NSW

Typhoid fever 1991† Includes paratyphoid in NSW, Qld and Vic

Quarantinable diseases

Cholera 1991†

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (human)2004 Reported under influenza in WA

Plague 1991†

Rabies 1991 1993 in ACT, 1997 in NSW

Severe acute respiratory syndrome 2003

Smallpox 2004

Viral haemorrhagic fever 1991 1993 in ACT

Yellow fever 1991†

Sexually transmissible infections

Chancroid 1991 No longer nationally notifiable from 2000

Chlamydial infection 1994 1999 in NSW

Donovanosis 1991 1993 in Tas, 2002 in NSW and SA

Gonococcal infection 1991†

Syphilis 1991 Includes syphilis <2 and >2 years/unknown duration to 2004

Syphilis (<2 years duration) 2004

Syphilis (>2 years or unknown duration)2004 Not reported in SA

Syphilis (congenital) 1991†

Vaccine-preventable diseases

Diphtheria 1991†

Haemophilus influenzae type b 1991 1994 in WA

Influenza (laboratory confirmed) 2001 2008 in SA

Measles 1991†

Mumps 1995 Not reported by Qld in 1995–96, 1999–2000

Pertussis 1991†

Pneumococcal disease (invasive) 2001

Poliomyelitis 1991†

Rubella 1993 1995 in Tas

Rubella (congenital) 1991†

Tetanus 1991 1994 in Qld

Varicella zoster (chickenpox) 2006 Not notifiable in NSW

Varicella zoster (shingles) 2006 Not notifiable in NSW

Varicella zoster (unspecified) 2006 Not notifiable in NSW

Notifiable diseases, Australia 1991–20113265

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

RESULTS

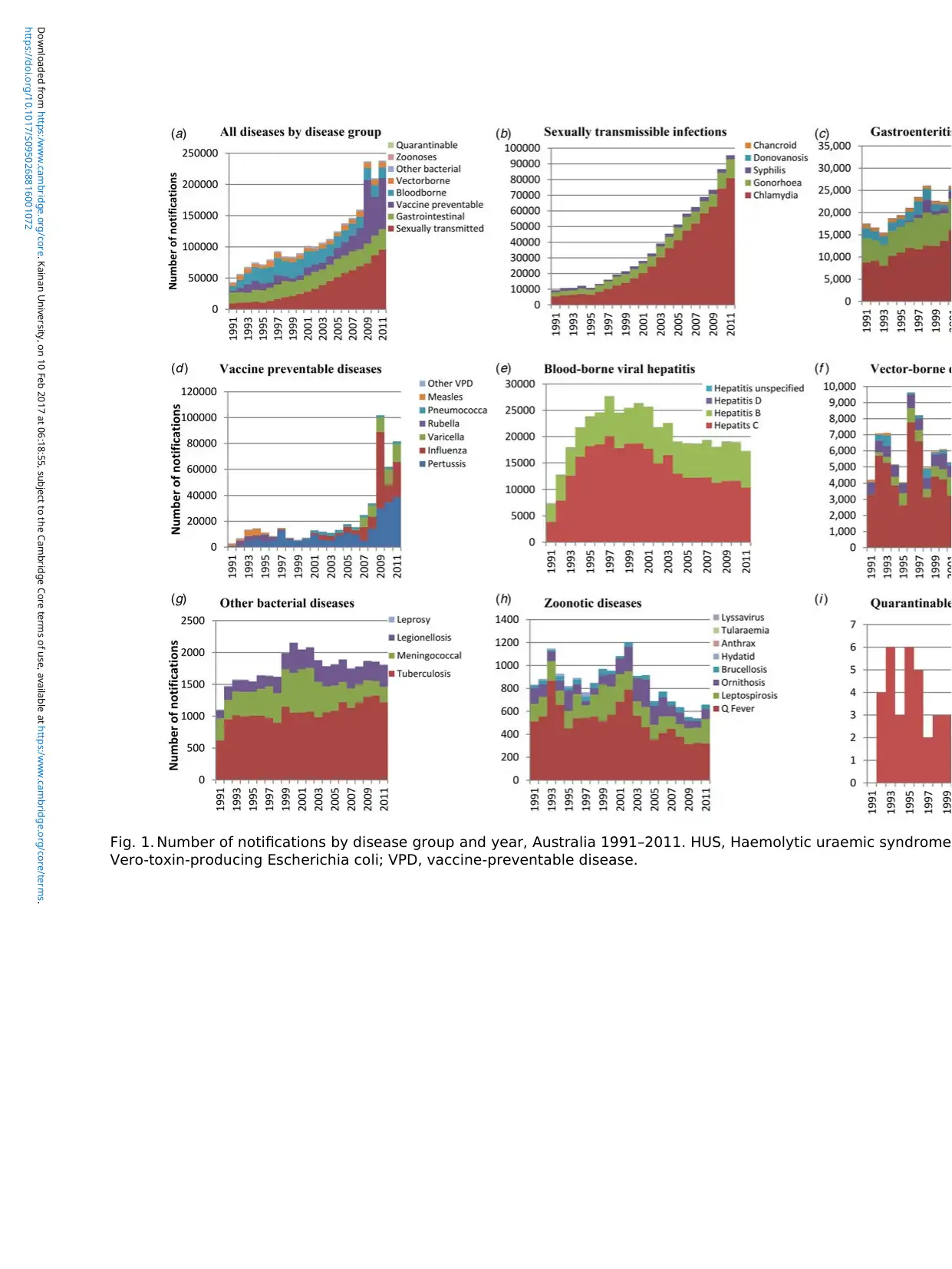

The NNDSS contains 2 421 134 notified cases of60

diseases from 1991 to 2011. STIs were most common

[790 990 (32·7%) notifications] and quarantinable dis-

easesleast common (79 notifications,all cholera)

(Table 2, Fig. 1). Chlamydialinfection,notifiable

from 1994,was the most commonly notified disease

[621 431(26%) notifications].The 10 pathogens

with highestnotification incidence were Chlamydia

trachomatis,Campylobacter,varicellazostervirus,

hepatitis C virus, influenza virus, Bordetella pertussis,

Salmonella,hepatitis B virus,Neisseria gonorrhoeae,

and Ross River virus (RRV) (Tables 3 and 4);these

comprised 88% ofall notifications despite campylo-

bacteriosisand varicella zosterinfection notbeing

notifiablein New South Wales (NSW), the most

populousstate.Fewer than 20 notificationswere

received for eightdiseases and no notifications were

received for seven diseases (Table 3).

Notification numbers increased over the study per-

iod, from 43 443 in 1991 (37 notifiable diseases)to

238 164 in 2011 (65 notifiable diseases) (Fig.1). The

nationalannualnotification incidence increased by

an average of6·4% peryear (Fig. 2), rising from

386/100 000 in the earliest sub-period (1991–1997) to

853/100 000in the latest sub-period(2005–2011)

(Table 3). Annual notification incidencefell most

markedly for rubella (average 30% decrease/year), fol-

lowed by Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib,25%),

measles(23%),and donovanosis(17%)(Table 3).

Rubella and hepatitis A were among the 10 highest in-

cidencediseasesin the earlieststudy sub-period

(Table 4). Conversely,influenza (average33%

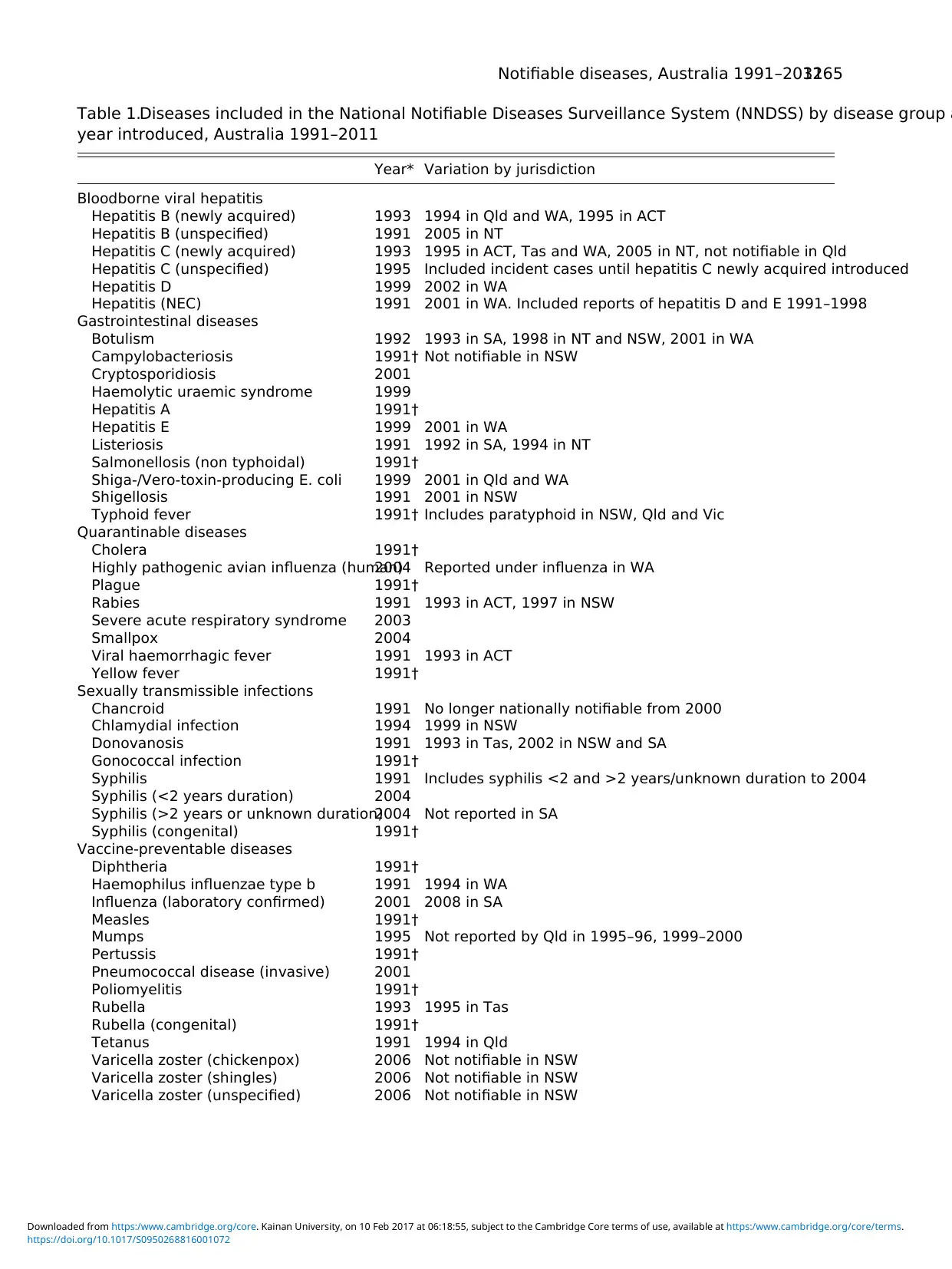

Table 1 (cont.)

Year* Variation by jurisdiction

Vector-borne diseases

Arbovirus infection (Not elsewhere

classified)

1991 1991–2000 included Japanese encephalitis, Kunjin, and Murray

Valley encephalitis (MVE) notifications

Barmah Forest virus infection 1995

Dengue virus infection 1991 1993 in ACT, 1995 in WA

Japanese encephalitis virus infection 2001

Kunjn virus infection 2001 Reported as MVE in ACT

Malaria 1991†

Murray Valley encephalitis virus infection2001

Ross River virus infection 1993

Zoonoses

Anthrax 2001 2002 in SA

Australian bat lyssavirus infection 2001

Brucellosis 1991†

Hydatid infection 1991 No longer nationally notifiable from 2001

Leptospirosis 1991†

Lyssavirus (not elsewhere classified) 2001

Ornithosis 1991 2001 in NSW, Qld did not report 1991, 1997–2001

Q fever 1991†

Tularaemia 2003

Other bacterial diseases

Legionellosis 1991†

Leprosy 1991†

Meningococcal disease (invasive) 1991† Includes conjunctival cases from ACT and NSW

Tuberculosis 1991

Source: NNDSS online (live) data and 2012 NNDSS annual report [3, 6].

Excludes HIV/AIDS and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease which are notified to other surveillance systems.

ACT, Australian Capital Territory; NSW, New South Wales; NT, Northern Territory; Qld, Queensland; SA, South Austra

Tas, Tasmania; Vic, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

* Year became nationally notifiable – listed as 1991 for diseases that were nationally notifiable when NNDSS began

diseases introduced after 1991 might have cases notified to NNDSS prior to becoming nationally notifiable.

† Diseases which were consistently notifiable across states for the entire study period.

3266 K. B. Gibney and others

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

The NNDSS contains 2 421 134 notified cases of60

diseases from 1991 to 2011. STIs were most common

[790 990 (32·7%) notifications] and quarantinable dis-

easesleast common (79 notifications,all cholera)

(Table 2, Fig. 1). Chlamydialinfection,notifiable

from 1994,was the most commonly notified disease

[621 431(26%) notifications].The 10 pathogens

with highestnotification incidence were Chlamydia

trachomatis,Campylobacter,varicellazostervirus,

hepatitis C virus, influenza virus, Bordetella pertussis,

Salmonella,hepatitis B virus,Neisseria gonorrhoeae,

and Ross River virus (RRV) (Tables 3 and 4);these

comprised 88% ofall notifications despite campylo-

bacteriosisand varicella zosterinfection notbeing

notifiablein New South Wales (NSW), the most

populousstate.Fewer than 20 notificationswere

received for eightdiseases and no notifications were

received for seven diseases (Table 3).

Notification numbers increased over the study per-

iod, from 43 443 in 1991 (37 notifiable diseases)to

238 164 in 2011 (65 notifiable diseases) (Fig.1). The

nationalannualnotification incidence increased by

an average of6·4% peryear (Fig. 2), rising from

386/100 000 in the earliest sub-period (1991–1997) to

853/100 000in the latest sub-period(2005–2011)

(Table 3). Annual notification incidencefell most

markedly for rubella (average 30% decrease/year), fol-

lowed by Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib,25%),

measles(23%),and donovanosis(17%)(Table 3).

Rubella and hepatitis A were among the 10 highest in-

cidencediseasesin the earlieststudy sub-period

(Table 4). Conversely,influenza (average33%

Table 1 (cont.)

Year* Variation by jurisdiction

Vector-borne diseases

Arbovirus infection (Not elsewhere

classified)

1991 1991–2000 included Japanese encephalitis, Kunjin, and Murray

Valley encephalitis (MVE) notifications

Barmah Forest virus infection 1995

Dengue virus infection 1991 1993 in ACT, 1995 in WA

Japanese encephalitis virus infection 2001

Kunjn virus infection 2001 Reported as MVE in ACT

Malaria 1991†

Murray Valley encephalitis virus infection2001

Ross River virus infection 1993

Zoonoses

Anthrax 2001 2002 in SA

Australian bat lyssavirus infection 2001

Brucellosis 1991†

Hydatid infection 1991 No longer nationally notifiable from 2001

Leptospirosis 1991†

Lyssavirus (not elsewhere classified) 2001

Ornithosis 1991 2001 in NSW, Qld did not report 1991, 1997–2001

Q fever 1991†

Tularaemia 2003

Other bacterial diseases

Legionellosis 1991†

Leprosy 1991†

Meningococcal disease (invasive) 1991† Includes conjunctival cases from ACT and NSW

Tuberculosis 1991

Source: NNDSS online (live) data and 2012 NNDSS annual report [3, 6].

Excludes HIV/AIDS and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease which are notified to other surveillance systems.

ACT, Australian Capital Territory; NSW, New South Wales; NT, Northern Territory; Qld, Queensland; SA, South Austra

Tas, Tasmania; Vic, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

* Year became nationally notifiable – listed as 1991 for diseases that were nationally notifiable when NNDSS began

diseases introduced after 1991 might have cases notified to NNDSS prior to becoming nationally notifiable.

† Diseases which were consistently notifiable across states for the entire study period.

3266 K. B. Gibney and others

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

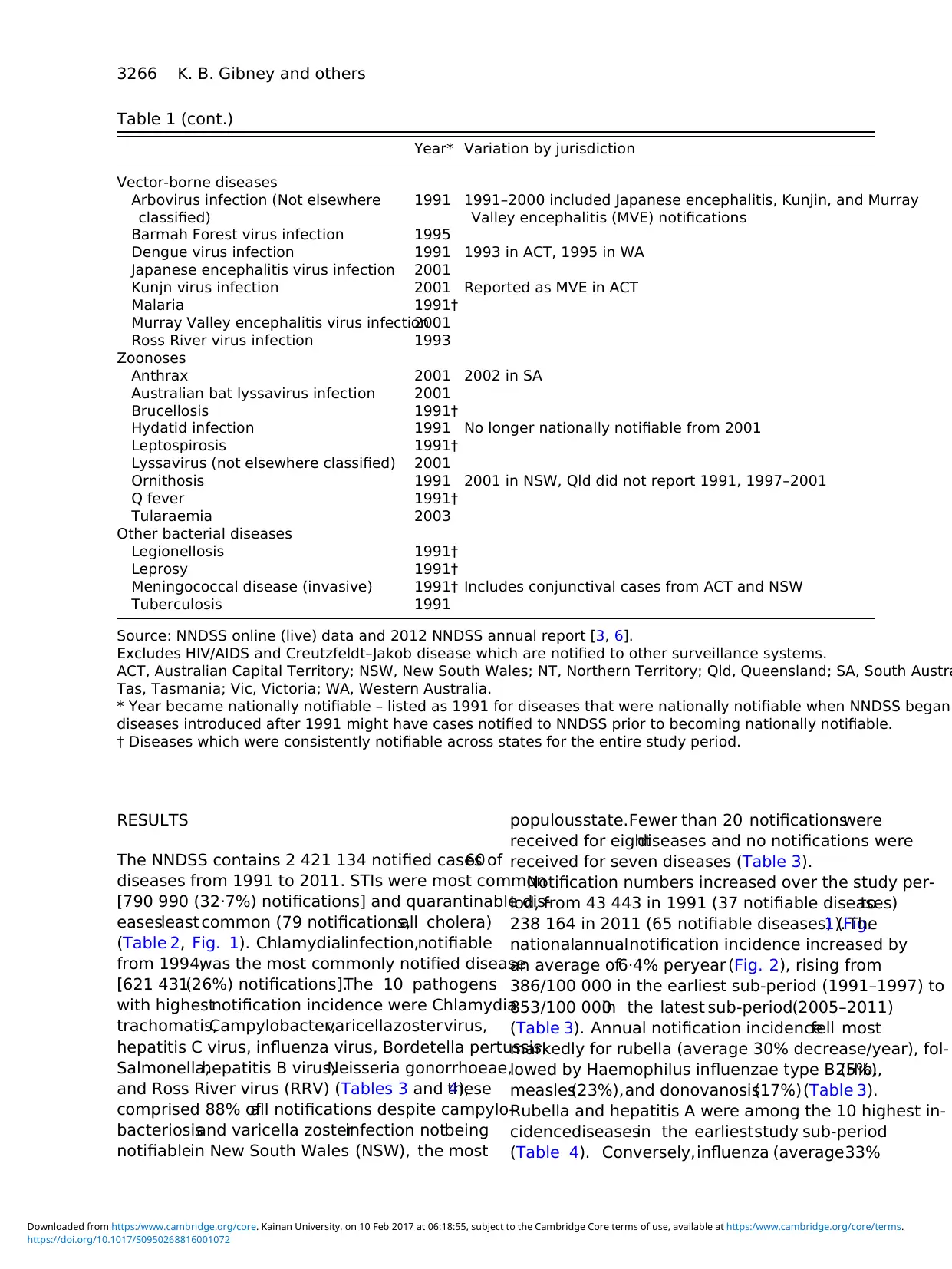

Table 2.Number, incidence, and demographics of notified cases by disease group and jurisdiction, Austral

Notifications Age,

median

years

Male,

%

Indigenous*,

%

Crude incidence

(/100 000 per year)

Age-standar

incidence

N (%) Mean (range) Mean (95%

All notifications 2 421 134 (100) 27 51·0 8·4 591 (251–1092) 621 (620

Disease group

Bloodborne viral hepatitis 431 608 (17·8) 34 61·1 3·4 106 (43–150) 104 (103

Gastrointestinal diseases 518 808 (21·4) 24 52·8 4·5 127 (88–147) 136 (135

Other bacterial diseases 36 960 (1·5) 37 55·5 5·1 9·0 (6·4–11·3) 8·7 (8·6

Quarantinable diseases 79 (0·0) 42 50·7 2·5 0·02 (0–0·03) 0·0 (0·0

Sexually transmissible

infections

790 990 (32·7) 23 45·7 17·8 193 (50–428) 210 (210

Vaccine-preventable diseases487 176 (20·1) 25 47·5 3·8 119 (17–470) 126 (126

Vector-borne diseases 137 817 (5·7) 40 51·3 2·0 34 (16–53) 31·9 (31·

Zoonoses 17 696 (0·7) 40 79·3 2·4 4·4 (2·4–6·6) 4·1 (4·1

Jurisdiction

Australian Capital Territory 38 083 (1·6) 26 51·5 0·5 560 (129–1098) 555 (549

New South Wales 584 382 (24·1) 29 53·7 1·8 430 (114–812) 449 (448

Northern Territory 110 930 (4·6) 23 47·9 58·1 2598 (1824–3653) 2512 (249

Queensland 644 556 (26·6) 26 49·1 9·7 850 (491–1504) 880 (877

South Australia 218 624 (9·0) 27 49·3 5·7 694 (291–1653) 740 (736

Tasmania 48 633 (2·0) 24 47·6 1·1 483 (245–991) 526 (523

Victoria 501 335 (20·7) 28 52·3 0·5 494 (184–995) 507 (506

Western Australia 274 591 (11·3) 25 50·6 18·1 684 (251–1262) 713 (711

CI, Confidence interval.

* Assumes all cases without Indigenous status reported were non-Indigenous.

† Only calculated for jurisdictions with Indigenous status reported for >75% of notified cases (Northern Territory, Sou

cases notified.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

Notifications Age,

median

years

Male,

%

Indigenous*,

%

Crude incidence

(/100 000 per year)

Age-standar

incidence

N (%) Mean (range) Mean (95%

All notifications 2 421 134 (100) 27 51·0 8·4 591 (251–1092) 621 (620

Disease group

Bloodborne viral hepatitis 431 608 (17·8) 34 61·1 3·4 106 (43–150) 104 (103

Gastrointestinal diseases 518 808 (21·4) 24 52·8 4·5 127 (88–147) 136 (135

Other bacterial diseases 36 960 (1·5) 37 55·5 5·1 9·0 (6·4–11·3) 8·7 (8·6

Quarantinable diseases 79 (0·0) 42 50·7 2·5 0·02 (0–0·03) 0·0 (0·0

Sexually transmissible

infections

790 990 (32·7) 23 45·7 17·8 193 (50–428) 210 (210

Vaccine-preventable diseases487 176 (20·1) 25 47·5 3·8 119 (17–470) 126 (126

Vector-borne diseases 137 817 (5·7) 40 51·3 2·0 34 (16–53) 31·9 (31·

Zoonoses 17 696 (0·7) 40 79·3 2·4 4·4 (2·4–6·6) 4·1 (4·1

Jurisdiction

Australian Capital Territory 38 083 (1·6) 26 51·5 0·5 560 (129–1098) 555 (549

New South Wales 584 382 (24·1) 29 53·7 1·8 430 (114–812) 449 (448

Northern Territory 110 930 (4·6) 23 47·9 58·1 2598 (1824–3653) 2512 (249

Queensland 644 556 (26·6) 26 49·1 9·7 850 (491–1504) 880 (877

South Australia 218 624 (9·0) 27 49·3 5·7 694 (291–1653) 740 (736

Tasmania 48 633 (2·0) 24 47·6 1·1 483 (245–991) 526 (523

Victoria 501 335 (20·7) 28 52·3 0·5 494 (184–995) 507 (506

Western Australia 274 591 (11·3) 25 50·6 18·1 684 (251–1262) 713 (711

CI, Confidence interval.

* Assumes all cases without Indigenous status reported were non-Indigenous.

† Only calculated for jurisdictions with Indigenous status reported for >75% of notified cases (Northern Territory, Sou

cases notified.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

Fig. 1. Number of notifications by disease group and year, Australia 1991–2011. HUS, Haemolytic uraemic syndrome

Vero-toxin-producing Escherichia coli; VPD, vaccine-preventable disease.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

Vero-toxin-producing Escherichia coli; VPD, vaccine-preventable disease.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

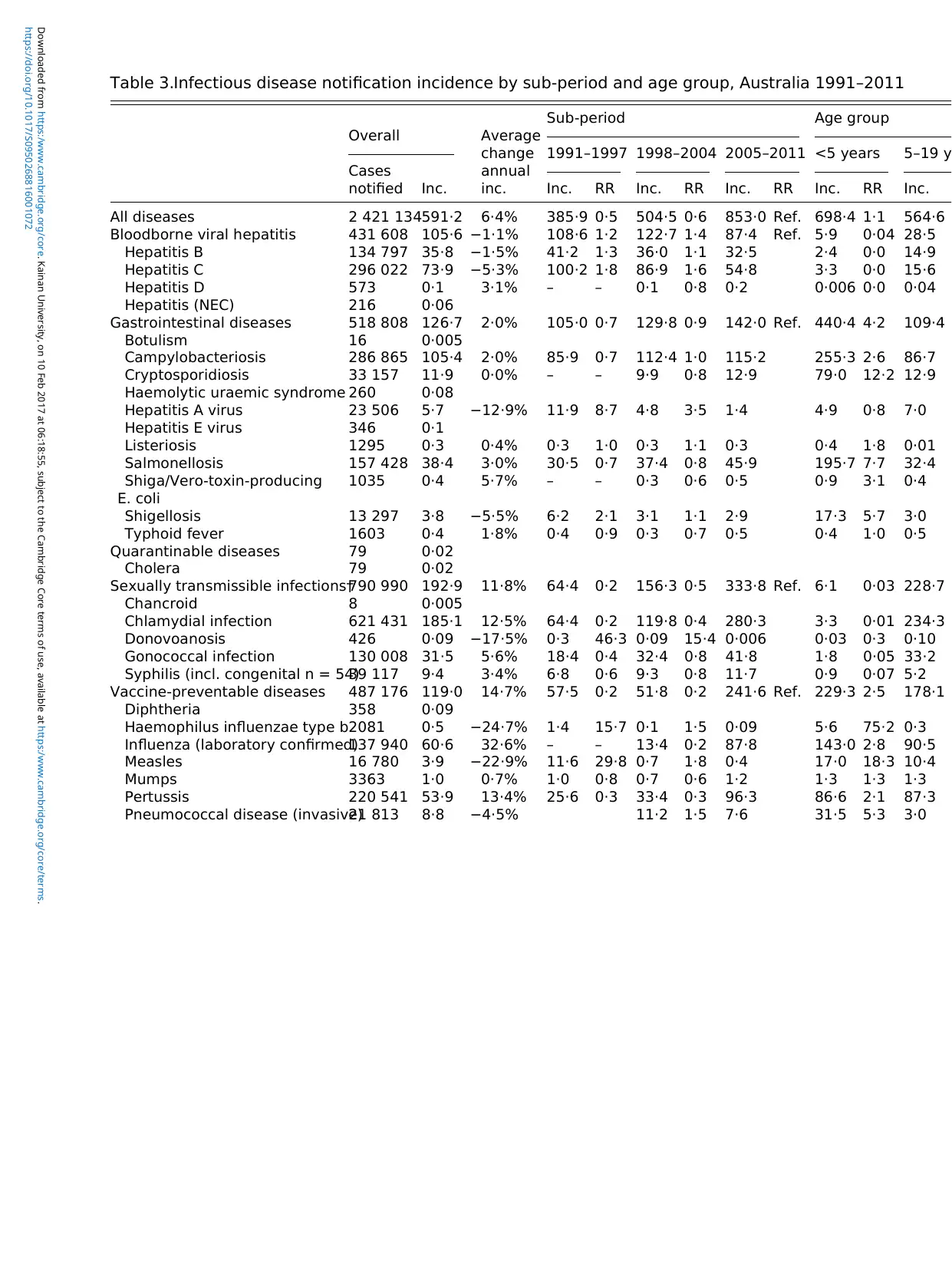

Table 3.Infectious disease notification incidence by sub-period and age group, Australia 1991–2011

Overall Average

change

annual

inc.

Sub-period Age group

Cases

notified Inc.

1991–1997 1998–2004 2005–2011 <5 years 5–19 y

Inc. RR Inc. RR Inc. RR Inc. RR Inc.

All diseases 2 421 134591·2 6·4% 385·9 0·5 504·5 0·6 853·0 Ref. 698·4 1·1 564·6

Bloodborne viral hepatitis 431 608 105·6 −1·1% 108·6 1·2 122·7 1·4 87·4 Ref. 5·9 0·04 28·5

Hepatitis B 134 797 35·8 −1·5% 41·2 1·3 36·0 1·1 32·5 2·4 0·0 14·9

Hepatitis C 296 022 73·9 −5·3% 100·2 1·8 86·9 1·6 54·8 3·3 0·0 15·6

Hepatitis D 573 0·1 3·1% – – 0·1 0·8 0·2 0·006 0·0 0·04

Hepatitis (NEC) 216 0·06

Gastrointestinal diseases 518 808 126·7 2·0% 105·0 0·7 129·8 0·9 142·0 Ref. 440·4 4·2 109·4

Botulism 16 0·005

Campylobacteriosis 286 865 105·4 2·0% 85·9 0·7 112·4 1·0 115·2 255·3 2·6 86·7

Cryptosporidiosis 33 157 11·9 0·0% – – 9·9 0·8 12·9 79·0 12·2 12·9

Haemolytic uraemic syndrome 260 0·08

Hepatitis A virus 23 506 5·7 −12·9% 11·9 8·7 4·8 3·5 1·4 4·9 0·8 7·0

Hepatitis E virus 346 0·1

Listeriosis 1295 0·3 0·4% 0·3 1·0 0·3 1·1 0·3 0·4 1·8 0·01

Salmonellosis 157 428 38·4 3·0% 30·5 0·7 37·4 0·8 45·9 195·7 7·7 32·4

Shiga/Vero-toxin-producing

E. coli

1035 0·4 5·7% – – 0·3 0·6 0·5 0·9 3·1 0·4

Shigellosis 13 297 3·8 −5·5% 6·2 2·1 3·1 1·1 2·9 17·3 5·7 3·0

Typhoid fever 1603 0·4 1·8% 0·4 0·9 0·3 0·7 0·5 0·4 1·0 0·5

Quarantinable diseases 79 0·02

Cholera 79 0·02

Sexually transmissible infections†790 990 192·9 11·8% 64·4 0·2 156·3 0·5 333·8 Ref. 6·1 0·03 228·7

Chancroid 8 0·005

Chlamydial infection 621 431 185·1 12·5% 64·4 0·2 119·8 0·4 280·3 3·3 0·01 234·3

Donovoanosis 426 0·09 −17·5% 0·3 46·3 0·09 15·4 0·006 0·03 0·3 0·10

Gonococcal infection 130 008 31·5 5·6% 18·4 0·4 32·4 0·8 41·8 1·8 0·05 33·2

Syphilis (incl. congenital n = 54)39 117 9·4 3·4% 6·8 0·6 9·3 0·8 11·7 0·9 0·07 5·2

Vaccine-preventable diseases 487 176 119·0 14·7% 57·5 0·2 51·8 0·2 241·6 Ref. 229·3 2·5 178·1

Diphtheria 358 0·09

Haemophilus influenzae type b2081 0·5 −24·7% 1·4 15·7 0·1 1·5 0·09 5·6 75·2 0·3

Influenza (laboratory confirmed)137 940 60·6 32·6% – – 13·4 0·2 87·8 143·0 2·8 90·5

Measles 16 780 3·9 −22·9% 11·6 29·8 0·7 1·8 0·4 17·0 18·3 10·4

Mumps 3363 1·0 0·7% 1·0 0·8 0·7 0·6 1·2 1·3 1·3 1·3

Pertussis 220 541 53·9 13·4% 25·6 0·3 33·4 0·3 96·3 86·6 2·1 87·3

Pneumococcal disease (invasive)21 813 8·8 −4·5% 11·2 1·5 7·6 31·5 5·3 3·0

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

Overall Average

change

annual

inc.

Sub-period Age group

Cases

notified Inc.

1991–1997 1998–2004 2005–2011 <5 years 5–19 y

Inc. RR Inc. RR Inc. RR Inc. RR Inc.

All diseases 2 421 134591·2 6·4% 385·9 0·5 504·5 0·6 853·0 Ref. 698·4 1·1 564·6

Bloodborne viral hepatitis 431 608 105·6 −1·1% 108·6 1·2 122·7 1·4 87·4 Ref. 5·9 0·04 28·5

Hepatitis B 134 797 35·8 −1·5% 41·2 1·3 36·0 1·1 32·5 2·4 0·0 14·9

Hepatitis C 296 022 73·9 −5·3% 100·2 1·8 86·9 1·6 54·8 3·3 0·0 15·6

Hepatitis D 573 0·1 3·1% – – 0·1 0·8 0·2 0·006 0·0 0·04

Hepatitis (NEC) 216 0·06

Gastrointestinal diseases 518 808 126·7 2·0% 105·0 0·7 129·8 0·9 142·0 Ref. 440·4 4·2 109·4

Botulism 16 0·005

Campylobacteriosis 286 865 105·4 2·0% 85·9 0·7 112·4 1·0 115·2 255·3 2·6 86·7

Cryptosporidiosis 33 157 11·9 0·0% – – 9·9 0·8 12·9 79·0 12·2 12·9

Haemolytic uraemic syndrome 260 0·08

Hepatitis A virus 23 506 5·7 −12·9% 11·9 8·7 4·8 3·5 1·4 4·9 0·8 7·0

Hepatitis E virus 346 0·1

Listeriosis 1295 0·3 0·4% 0·3 1·0 0·3 1·1 0·3 0·4 1·8 0·01

Salmonellosis 157 428 38·4 3·0% 30·5 0·7 37·4 0·8 45·9 195·7 7·7 32·4

Shiga/Vero-toxin-producing

E. coli

1035 0·4 5·7% – – 0·3 0·6 0·5 0·9 3·1 0·4

Shigellosis 13 297 3·8 −5·5% 6·2 2·1 3·1 1·1 2·9 17·3 5·7 3·0

Typhoid fever 1603 0·4 1·8% 0·4 0·9 0·3 0·7 0·5 0·4 1·0 0·5

Quarantinable diseases 79 0·02

Cholera 79 0·02

Sexually transmissible infections†790 990 192·9 11·8% 64·4 0·2 156·3 0·5 333·8 Ref. 6·1 0·03 228·7

Chancroid 8 0·005

Chlamydial infection 621 431 185·1 12·5% 64·4 0·2 119·8 0·4 280·3 3·3 0·01 234·3

Donovoanosis 426 0·09 −17·5% 0·3 46·3 0·09 15·4 0·006 0·03 0·3 0·10

Gonococcal infection 130 008 31·5 5·6% 18·4 0·4 32·4 0·8 41·8 1·8 0·05 33·2

Syphilis (incl. congenital n = 54)39 117 9·4 3·4% 6·8 0·6 9·3 0·8 11·7 0·9 0·07 5·2

Vaccine-preventable diseases 487 176 119·0 14·7% 57·5 0·2 51·8 0·2 241·6 Ref. 229·3 2·5 178·1

Diphtheria 358 0·09

Haemophilus influenzae type b2081 0·5 −24·7% 1·4 15·7 0·1 1·5 0·09 5·6 75·2 0·3

Influenza (laboratory confirmed)137 940 60·6 32·6% – – 13·4 0·2 87·8 143·0 2·8 90·5

Measles 16 780 3·9 −22·9% 11·6 29·8 0·7 1·8 0·4 17·0 18·3 10·4

Mumps 3363 1·0 0·7% 1·0 0·8 0·7 0·6 1·2 1·3 1·3 1·3

Pertussis 220 541 53·9 13·4% 25·6 0·3 33·4 0·3 96·3 86·6 2·1 87·3

Pneumococcal disease (invasive)21 813 8·8 −4·5% 11·2 1·5 7·6 31·5 5·3 3·0

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

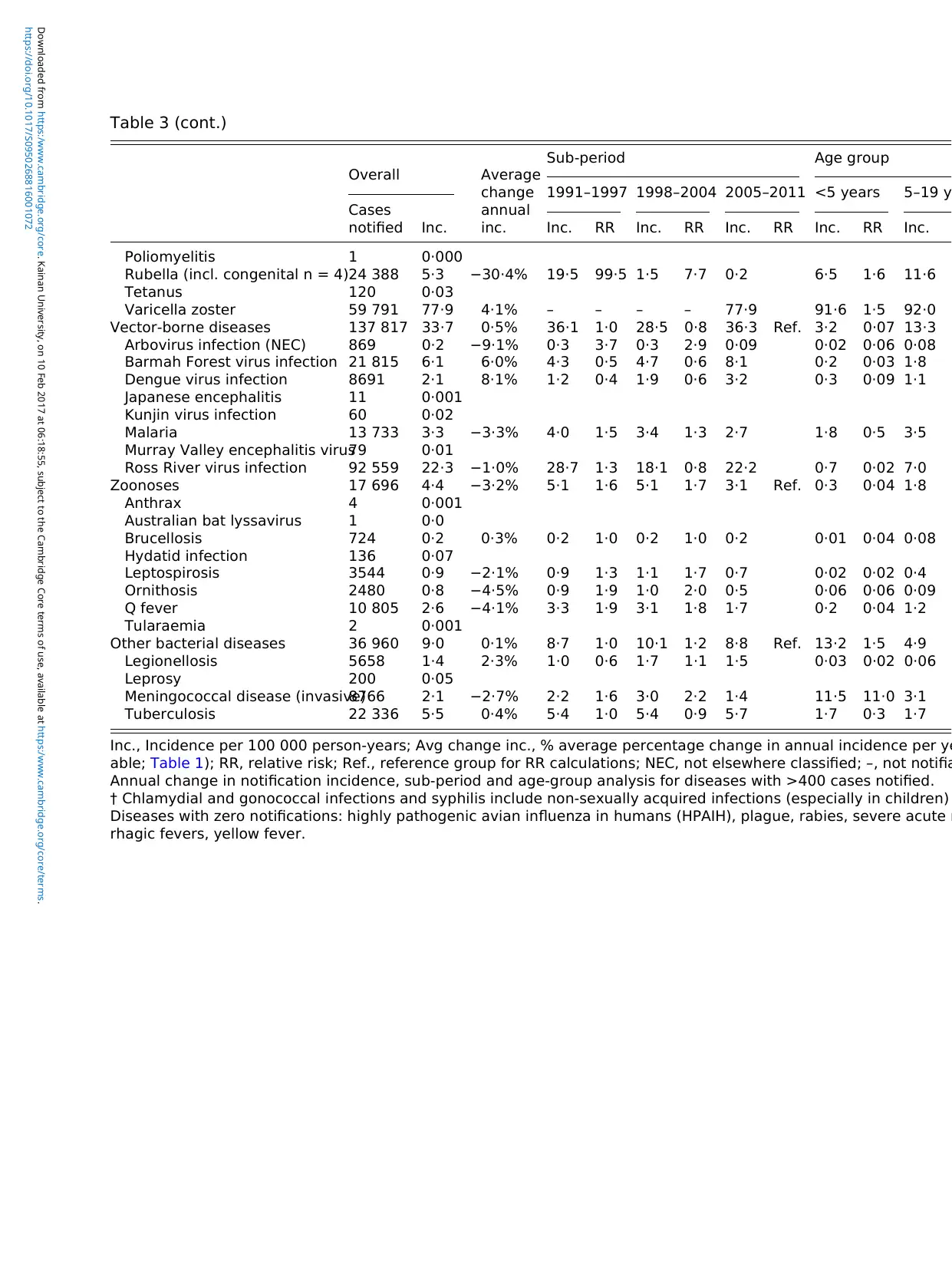

Table 3 (cont.)

Overall Average

change

annual

inc.

Sub-period Age group

Cases

notified Inc.

1991–1997 1998–2004 2005–2011 <5 years 5–19 y

Inc. RR Inc. RR Inc. RR Inc. RR Inc.

Poliomyelitis 1 0·000

Rubella (incl. congenital n = 4)24 388 5·3 −30·4% 19·5 99·5 1·5 7·7 0·2 6·5 1·6 11·6

Tetanus 120 0·03

Varicella zoster 59 791 77·9 4·1% – – – – 77·9 91·6 1·5 92·0

Vector-borne diseases 137 817 33·7 0·5% 36·1 1·0 28·5 0·8 36·3 Ref. 3·2 0·07 13·3

Arbovirus infection (NEC) 869 0·2 −9·1% 0·3 3·7 0·3 2·9 0·09 0·02 0·06 0·08

Barmah Forest virus infection 21 815 6·1 6·0% 4·3 0·5 4·7 0·6 8·1 0·2 0·03 1·8

Dengue virus infection 8691 2·1 8·1% 1·2 0·4 1·9 0·6 3·2 0·3 0·09 1·1

Japanese encephalitis 11 0·001

Kunjin virus infection 60 0·02

Malaria 13 733 3·3 −3·3% 4·0 1·5 3·4 1·3 2·7 1·8 0·5 3·5

Murray Valley encephalitis virus79 0·01

Ross River virus infection 92 559 22·3 −1·0% 28·7 1·3 18·1 0·8 22·2 0·7 0·02 7·0

Zoonoses 17 696 4·4 −3·2% 5·1 1·6 5·1 1·7 3·1 Ref. 0·3 0·04 1·8

Anthrax 4 0·001

Australian bat lyssavirus 1 0·0

Brucellosis 724 0·2 0·3% 0·2 1·0 0·2 1·0 0·2 0·01 0·04 0·08

Hydatid infection 136 0·07

Leptospirosis 3544 0·9 −2·1% 0·9 1·3 1·1 1·7 0·7 0·02 0·02 0·4

Ornithosis 2480 0·8 −4·5% 0·9 1·9 1·0 2·0 0·5 0·06 0·06 0·09

Q fever 10 805 2·6 −4·1% 3·3 1·9 3·1 1·8 1·7 0·2 0·04 1·2

Tularaemia 2 0·001

Other bacterial diseases 36 960 9·0 0·1% 8·7 1·0 10·1 1·2 8·8 Ref. 13·2 1·5 4·9

Legionellosis 5658 1·4 2·3% 1·0 0·6 1·7 1·1 1·5 0·03 0·02 0·06

Leprosy 200 0·05

Meningococcal disease (invasive)8766 2·1 −2·7% 2·2 1·6 3·0 2·2 1·4 11·5 11·0 3·1

Tuberculosis 22 336 5·5 0·4% 5·4 1·0 5·4 0·9 5·7 1·7 0·3 1·7

Inc., Incidence per 100 000 person-years; Avg change inc., % average percentage change in annual incidence per ye

able; Table 1); RR, relative risk; Ref., reference group for RR calculations; NEC, not elsewhere classified; –, not notifia

Annual change in notification incidence, sub-period and age-group analysis for diseases with >400 cases notified.

† Chlamydial and gonococcal infections and syphilis include non-sexually acquired infections (especially in children)

Diseases with zero notifications: highly pathogenic avian influenza in humans (HPAIH), plague, rabies, severe acute r

rhagic fevers, yellow fever.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

Overall Average

change

annual

inc.

Sub-period Age group

Cases

notified Inc.

1991–1997 1998–2004 2005–2011 <5 years 5–19 y

Inc. RR Inc. RR Inc. RR Inc. RR Inc.

Poliomyelitis 1 0·000

Rubella (incl. congenital n = 4)24 388 5·3 −30·4% 19·5 99·5 1·5 7·7 0·2 6·5 1·6 11·6

Tetanus 120 0·03

Varicella zoster 59 791 77·9 4·1% – – – – 77·9 91·6 1·5 92·0

Vector-borne diseases 137 817 33·7 0·5% 36·1 1·0 28·5 0·8 36·3 Ref. 3·2 0·07 13·3

Arbovirus infection (NEC) 869 0·2 −9·1% 0·3 3·7 0·3 2·9 0·09 0·02 0·06 0·08

Barmah Forest virus infection 21 815 6·1 6·0% 4·3 0·5 4·7 0·6 8·1 0·2 0·03 1·8

Dengue virus infection 8691 2·1 8·1% 1·2 0·4 1·9 0·6 3·2 0·3 0·09 1·1

Japanese encephalitis 11 0·001

Kunjin virus infection 60 0·02

Malaria 13 733 3·3 −3·3% 4·0 1·5 3·4 1·3 2·7 1·8 0·5 3·5

Murray Valley encephalitis virus79 0·01

Ross River virus infection 92 559 22·3 −1·0% 28·7 1·3 18·1 0·8 22·2 0·7 0·02 7·0

Zoonoses 17 696 4·4 −3·2% 5·1 1·6 5·1 1·7 3·1 Ref. 0·3 0·04 1·8

Anthrax 4 0·001

Australian bat lyssavirus 1 0·0

Brucellosis 724 0·2 0·3% 0·2 1·0 0·2 1·0 0·2 0·01 0·04 0·08

Hydatid infection 136 0·07

Leptospirosis 3544 0·9 −2·1% 0·9 1·3 1·1 1·7 0·7 0·02 0·02 0·4

Ornithosis 2480 0·8 −4·5% 0·9 1·9 1·0 2·0 0·5 0·06 0·06 0·09

Q fever 10 805 2·6 −4·1% 3·3 1·9 3·1 1·8 1·7 0·2 0·04 1·2

Tularaemia 2 0·001

Other bacterial diseases 36 960 9·0 0·1% 8·7 1·0 10·1 1·2 8·8 Ref. 13·2 1·5 4·9

Legionellosis 5658 1·4 2·3% 1·0 0·6 1·7 1·1 1·5 0·03 0·02 0·06

Leprosy 200 0·05

Meningococcal disease (invasive)8766 2·1 −2·7% 2·2 1·6 3·0 2·2 1·4 11·5 11·0 3·1

Tuberculosis 22 336 5·5 0·4% 5·4 1·0 5·4 0·9 5·7 1·7 0·3 1·7

Inc., Incidence per 100 000 person-years; Avg change inc., % average percentage change in annual incidence per ye

able; Table 1); RR, relative risk; Ref., reference group for RR calculations; NEC, not elsewhere classified; –, not notifia

Annual change in notification incidence, sub-period and age-group analysis for diseases with >400 cases notified.

† Chlamydial and gonococcal infections and syphilis include non-sexually acquired infections (especially in children)

Diseases with zero notifications: highly pathogenic avian influenza in humans (HPAIH), plague, rabies, severe acute r

rhagic fevers, yellow fever.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

increase/year,notifiable from 2001),pertussis (13%),

and chlamydialinfection (13%,notifiable from 1994)

increased the most across the study period.Twenty-

one diseases were consistently notifiable across juris-

dictions for the entire study period (Table 1);annual

incidence of these increased by 4·1% per year.

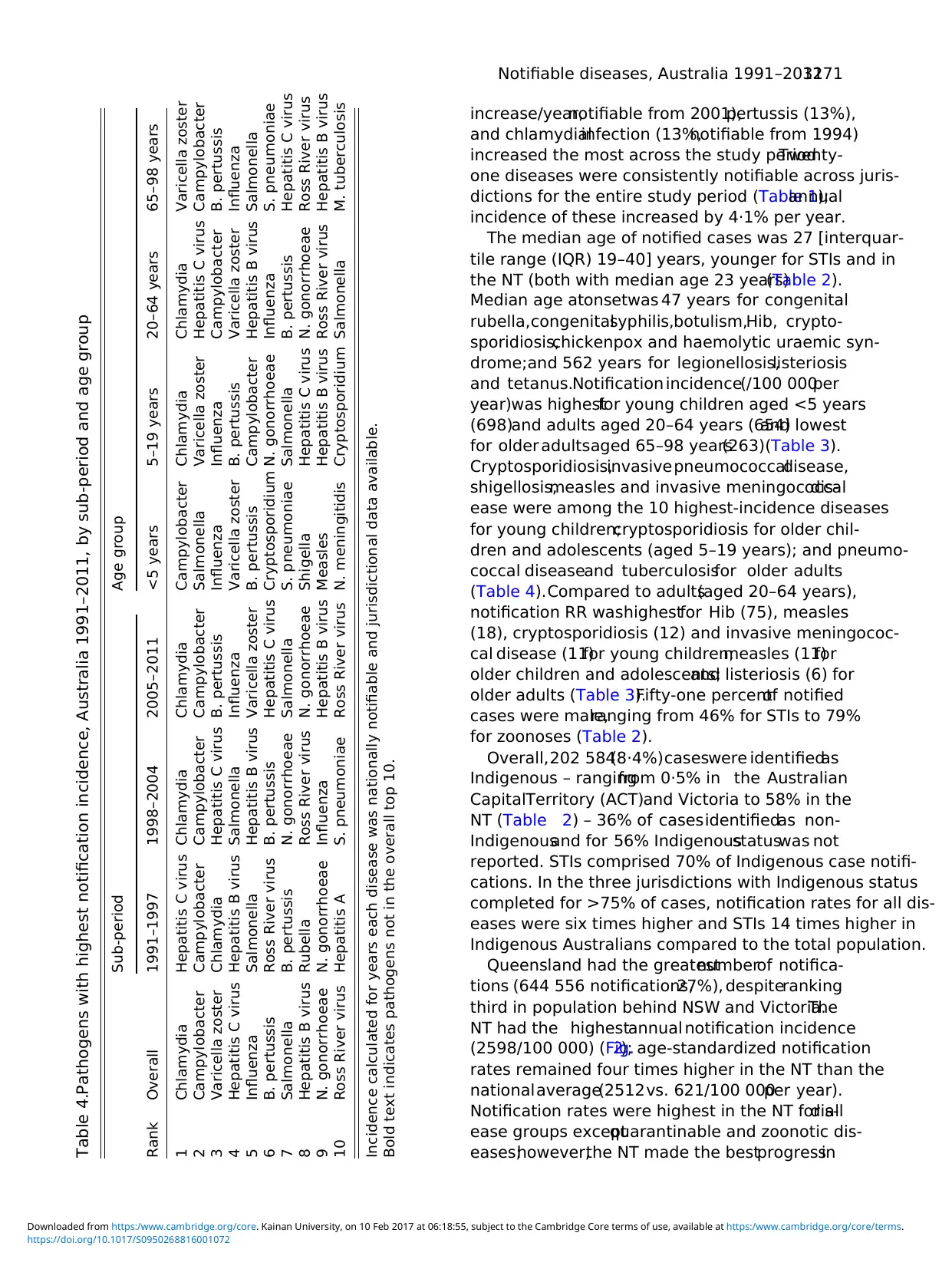

The median age of notified cases was 27 [interquar-

tile range (IQR) 19–40] years, younger for STIs and in

the NT (both with median age 23 years)(Table 2).

Median age atonsetwas 47 years for congenital

rubella,congenitalsyphilis,botulism,Hib, crypto-

sporidiosis,chickenpox and haemolytic uraemic syn-

drome;and 562 years for legionellosis,listeriosis

and tetanus.Notification incidence(/100 000per

year)was highestfor young children aged <5 years

(698)and adults aged 20–64 years (654)and lowest

for older adultsaged 65–98 years(263)(Table 3).

Cryptosporidiosis,invasivepneumococcaldisease,

shigellosis,measles and invasive meningococcaldis-

ease were among the 10 highest-incidence diseases

for young children;cryptosporidiosis for older chil-

dren and adolescents (aged 5–19 years); and pneumo-

coccal diseaseand tuberculosisfor older adults

(Table 4).Compared to adults(aged 20–64 years),

notification RR washighestfor Hib (75), measles

(18), cryptosporidiosis (12) and invasive meningococ-

cal disease (11)for young children;measles (11)for

older children and adolescents;and listeriosis (6) for

older adults (Table 3).Fifty-one percentof notified

cases were male,ranging from 46% for STIs to 79%

for zoonoses (Table 2).

Overall,202 584(8·4%)caseswere identifiedas

Indigenous – rangingfrom 0·5% in the Australian

CapitalTerritory (ACT)and Victoria to 58% in the

NT (Table 2) – 36% of casesidentifiedas non-

Indigenousand for 56% Indigenousstatuswas not

reported. STIs comprised 70% of Indigenous case notifi-

cations. In the three jurisdictions with Indigenous status

completed for >75% of cases, notification rates for all dis-

eases were six times higher and STIs 14 times higher in

Indigenous Australians compared to the total population.

Queensland had the greatestnumberof notifica-

tions (644 556 notifications,27%), despiteranking

third in population behind NSW and Victoria.The

NT had the highestannual notification incidence

(2598/100 000) (Fig.2); age-standardized notification

rates remained four times higher in the NT than the

nationalaverage(2512vs. 621/100 000per year).

Notification rates were highest in the NT for alldis-

ease groups exceptquarantinable and zoonotic dis-

eases;however,the NT made the bestprogressin

Table 4.Pathogens with highest notification incidence, Australia 1991–2011, by sub-period and age group

Rank Overall

Sub-period Age group

1991–1997 1998–2004 2005–2011 <5 years 5–19 years 20–64 years 65–98 years

1 Chlamydia Hepatitis C virus Chlamydia Chlamydia Campylobacter Chlamydia Chlamydia Varicella zoster

2 Campylobacter Campylobacter Campylobacter Campylobacter Salmonella Varicella zoster Hepatitis C virus Campylobacter

3 Varicella zoster Chlamydia Hepatitis C virus B. pertussis Influenza Influenza Campylobacter B. pertussis

4 Hepatitis C virus Hepatitis B virus Salmonella Influenza Varicella zoster B. pertussis Varicella zoster Influenza

5 Influenza Salmonella Hepatitis B virus Varicella zoster B. pertussis Campylobacter Hepatitis B virus Salmonella

6 B. pertussis Ross River virus B. pertussis Hepatitis C virus Cryptosporidium N. gonorrhoeae Influenza S. pneumoniae

7 Salmonella B. pertussis N. gonorrhoeae Salmonella S. pneumoniae Salmonella B. pertussis Hepatitis C virus

8 Hepatitis B virus Rubella Ross River virus N. gonorrhoeae Shigella Hepatitis C virus N. gonorrhoeae Ross River virus

9 N. gonorrhoeae N. gonorrhoeae Influenza Hepatitis B virus Measles Hepatitis B virus Ross River virus Hepatitis B virus

10 Ross River virus Hepatitis A S. pneumoniae Ross River virus N. meningitidis Cryptosporidium Salmonella M. tuberculosis

Incidence calculated for years each disease was nationally notifiable and jurisdictional data available.

Bold text indicates pathogens not in the overall top 10.

Notifiable diseases, Australia 1991–20113271

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

and chlamydialinfection (13%,notifiable from 1994)

increased the most across the study period.Twenty-

one diseases were consistently notifiable across juris-

dictions for the entire study period (Table 1);annual

incidence of these increased by 4·1% per year.

The median age of notified cases was 27 [interquar-

tile range (IQR) 19–40] years, younger for STIs and in

the NT (both with median age 23 years)(Table 2).

Median age atonsetwas 47 years for congenital

rubella,congenitalsyphilis,botulism,Hib, crypto-

sporidiosis,chickenpox and haemolytic uraemic syn-

drome;and 562 years for legionellosis,listeriosis

and tetanus.Notification incidence(/100 000per

year)was highestfor young children aged <5 years

(698)and adults aged 20–64 years (654)and lowest

for older adultsaged 65–98 years(263)(Table 3).

Cryptosporidiosis,invasivepneumococcaldisease,

shigellosis,measles and invasive meningococcaldis-

ease were among the 10 highest-incidence diseases

for young children;cryptosporidiosis for older chil-

dren and adolescents (aged 5–19 years); and pneumo-

coccal diseaseand tuberculosisfor older adults

(Table 4).Compared to adults(aged 20–64 years),

notification RR washighestfor Hib (75), measles

(18), cryptosporidiosis (12) and invasive meningococ-

cal disease (11)for young children;measles (11)for

older children and adolescents;and listeriosis (6) for

older adults (Table 3).Fifty-one percentof notified

cases were male,ranging from 46% for STIs to 79%

for zoonoses (Table 2).

Overall,202 584(8·4%)caseswere identifiedas

Indigenous – rangingfrom 0·5% in the Australian

CapitalTerritory (ACT)and Victoria to 58% in the

NT (Table 2) – 36% of casesidentifiedas non-

Indigenousand for 56% Indigenousstatuswas not

reported. STIs comprised 70% of Indigenous case notifi-

cations. In the three jurisdictions with Indigenous status

completed for >75% of cases, notification rates for all dis-

eases were six times higher and STIs 14 times higher in

Indigenous Australians compared to the total population.

Queensland had the greatestnumberof notifica-

tions (644 556 notifications,27%), despiteranking

third in population behind NSW and Victoria.The

NT had the highestannual notification incidence

(2598/100 000) (Fig.2); age-standardized notification

rates remained four times higher in the NT than the

nationalaverage(2512vs. 621/100 000per year).

Notification rates were highest in the NT for alldis-

ease groups exceptquarantinable and zoonotic dis-

eases;however,the NT made the bestprogressin

Table 4.Pathogens with highest notification incidence, Australia 1991–2011, by sub-period and age group

Rank Overall

Sub-period Age group

1991–1997 1998–2004 2005–2011 <5 years 5–19 years 20–64 years 65–98 years

1 Chlamydia Hepatitis C virus Chlamydia Chlamydia Campylobacter Chlamydia Chlamydia Varicella zoster

2 Campylobacter Campylobacter Campylobacter Campylobacter Salmonella Varicella zoster Hepatitis C virus Campylobacter

3 Varicella zoster Chlamydia Hepatitis C virus B. pertussis Influenza Influenza Campylobacter B. pertussis

4 Hepatitis C virus Hepatitis B virus Salmonella Influenza Varicella zoster B. pertussis Varicella zoster Influenza

5 Influenza Salmonella Hepatitis B virus Varicella zoster B. pertussis Campylobacter Hepatitis B virus Salmonella

6 B. pertussis Ross River virus B. pertussis Hepatitis C virus Cryptosporidium N. gonorrhoeae Influenza S. pneumoniae

7 Salmonella B. pertussis N. gonorrhoeae Salmonella S. pneumoniae Salmonella B. pertussis Hepatitis C virus

8 Hepatitis B virus Rubella Ross River virus N. gonorrhoeae Shigella Hepatitis C virus N. gonorrhoeae Ross River virus

9 N. gonorrhoeae N. gonorrhoeae Influenza Hepatitis B virus Measles Hepatitis B virus Ross River virus Hepatitis B virus

10 Ross River virus Hepatitis A S. pneumoniae Ross River virus N. meningitidis Cryptosporidium Salmonella M. tuberculosis

Incidence calculated for years each disease was nationally notifiable and jurisdictional data available.

Bold text indicates pathogens not in the overall top 10.

Notifiable diseases, Australia 1991–20113271

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

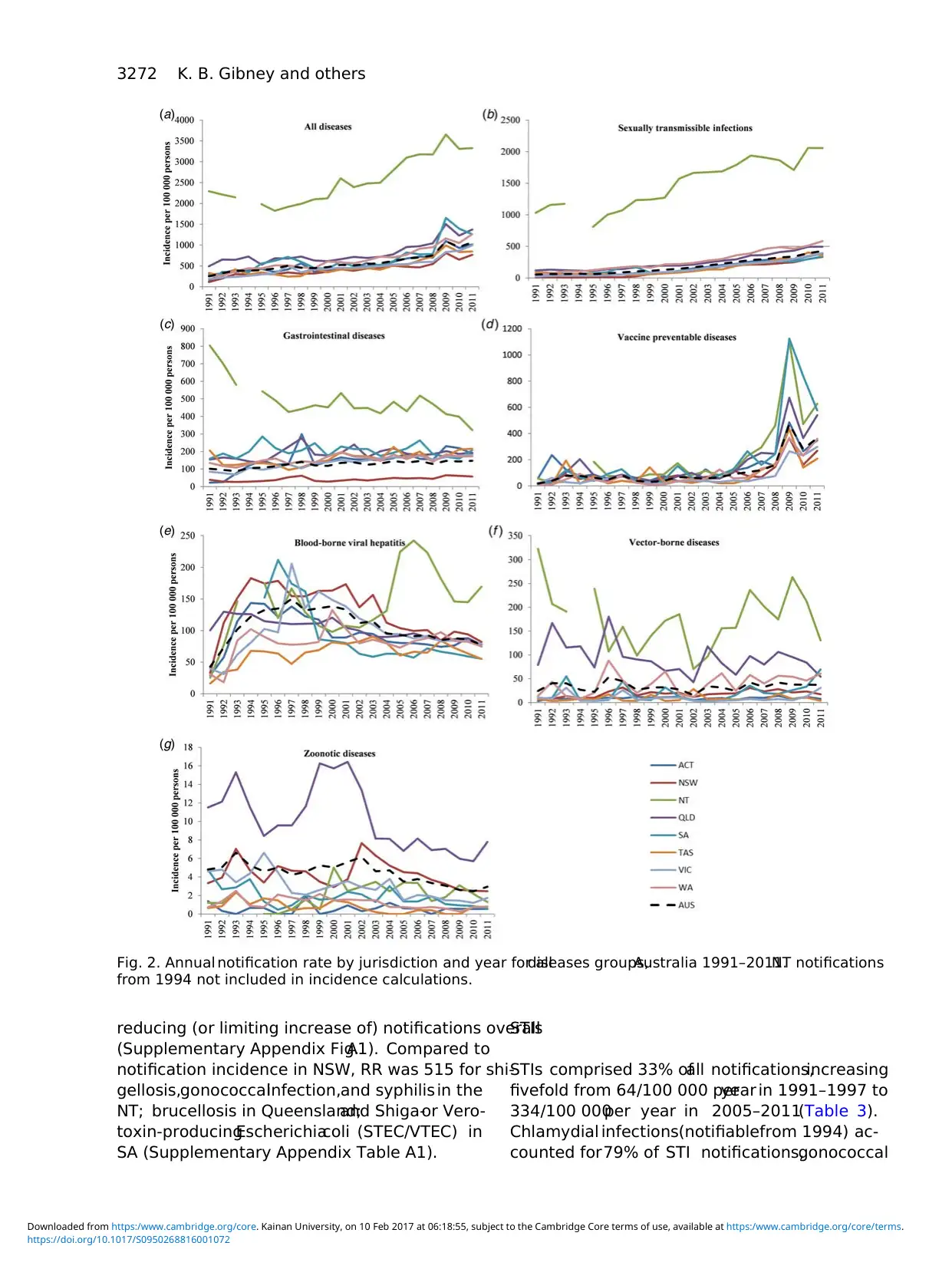

reducing (or limiting increase of) notifications overall

(Supplementary Appendix Fig.A1). Compared to

notification incidence in NSW, RR was 515 for shi-

gellosis,gonococcalinfection,and syphilis in the

NT; brucellosis in Queensland;and Shiga-or Vero-

toxin-producingEscherichiacoli (STEC/VTEC) in

SA (Supplementary Appendix Table A1).

STIs

STIs comprised 33% ofall notifications,increasing

fivefold from 64/100 000 peryear in 1991–1997 to

334/100 000per year in 2005–2011(Table 3).

Chlamydial infections(notifiablefrom 1994) ac-

counted for79% of STI notifications,gonococcal

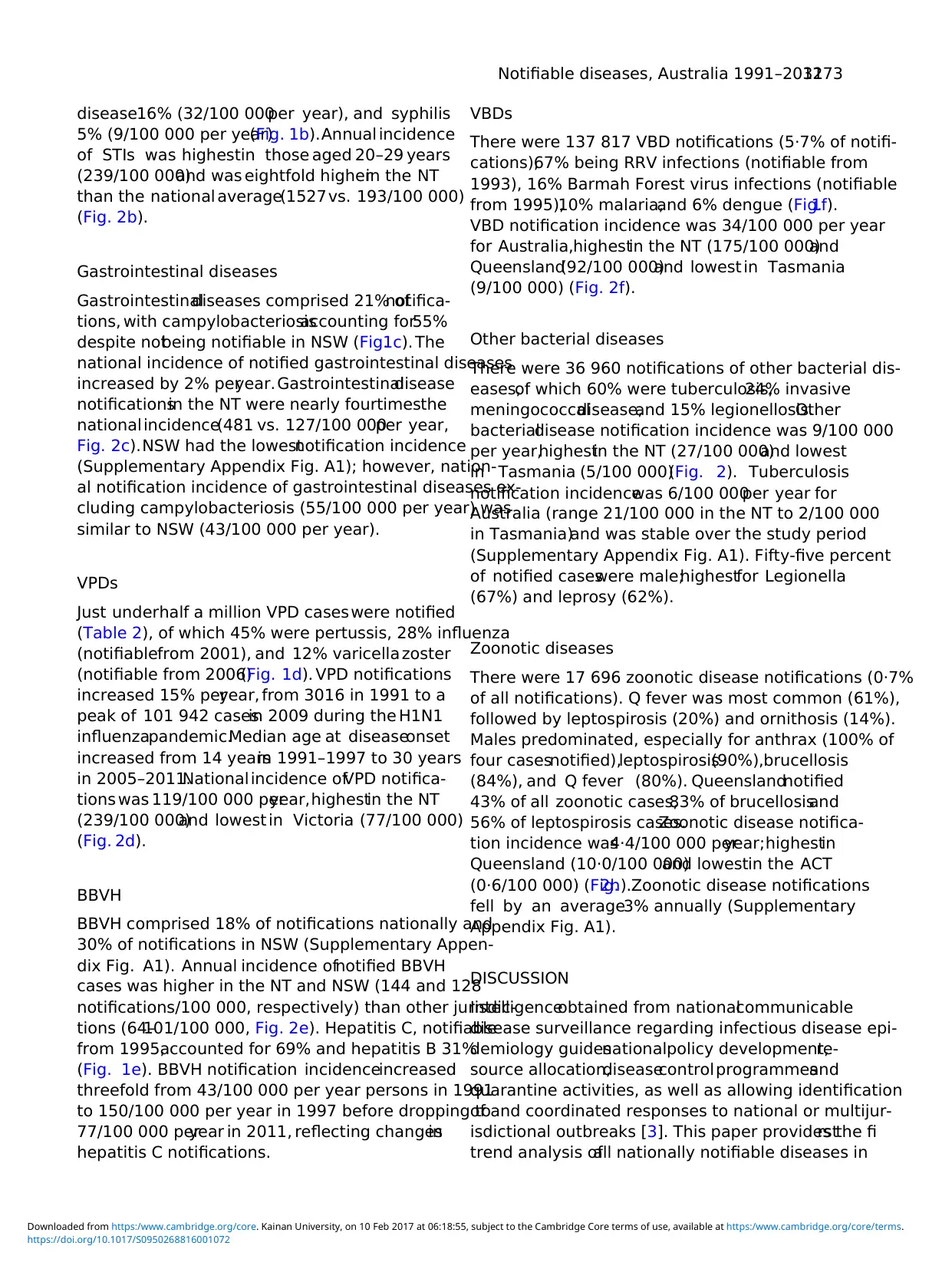

Fig. 2. Annual notification rate by jurisdiction and year for alldiseases groups,Australia 1991–2011.NT notifications

from 1994 not included in incidence calculations.

3272 K. B. Gibney and others

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

(Supplementary Appendix Fig.A1). Compared to

notification incidence in NSW, RR was 515 for shi-

gellosis,gonococcalinfection,and syphilis in the

NT; brucellosis in Queensland;and Shiga-or Vero-

toxin-producingEscherichiacoli (STEC/VTEC) in

SA (Supplementary Appendix Table A1).

STIs

STIs comprised 33% ofall notifications,increasing

fivefold from 64/100 000 peryear in 1991–1997 to

334/100 000per year in 2005–2011(Table 3).

Chlamydial infections(notifiablefrom 1994) ac-

counted for79% of STI notifications,gonococcal

Fig. 2. Annual notification rate by jurisdiction and year for alldiseases groups,Australia 1991–2011.NT notifications

from 1994 not included in incidence calculations.

3272 K. B. Gibney and others

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

disease16% (32/100 000per year), and syphilis

5% (9/100 000 per year)(Fig. 1b).Annual incidence

of STIs was highestin those aged 20–29 years

(239/100 000)and was eightfold higherin the NT

than the national average(1527vs. 193/100 000)

(Fig. 2b).

Gastrointestinal diseases

Gastrointestinaldiseases comprised 21% ofnotifica-

tions, with campylobacteriosisaccounting for55%

despite notbeing notifiable in NSW (Fig.1c). The

national incidence of notified gastrointestinal diseases

increased by 2% peryear. Gastrointestinaldisease

notificationsin the NT were nearly fourtimesthe

national incidence(481 vs. 127/100 000per year,

Fig. 2c).NSW had the lowestnotification incidence

(Supplementary Appendix Fig. A1); however, nation-

al notification incidence of gastrointestinal diseases ex-

cluding campylobacteriosis (55/100 000 per year) was

similar to NSW (43/100 000 per year).

VPDs

Just underhalf a million VPD caseswere notified

(Table 2), of which 45% were pertussis, 28% influenza

(notifiablefrom 2001), and 12% varicella zoster

(notifiable from 2006)(Fig. 1d). VPD notifications

increased 15% peryear, from 3016 in 1991 to a

peak of 101 942 casesin 2009 during the H1N1

influenzapandemic.Median age at diseaseonset

increased from 14 yearsin 1991–1997 to 30 years

in 2005–2011.National incidence ofVPD notifica-

tions was 119/100 000 peryear,highestin the NT

(239/100 000)and lowest in Victoria (77/100 000)

(Fig. 2d).

BBVH

BBVH comprised 18% of notifications nationally and

30% of notifications in NSW (Supplementary Appen-

dix Fig. A1). Annual incidence ofnotified BBVH

cases was higher in the NT and NSW (144 and 128

notifications/100 000, respectively) than other jurisdic-

tions (64–101/100 000, Fig. 2e). Hepatitis C, notifiable

from 1995,accounted for 69% and hepatitis B 31%

(Fig. 1e). BBVH notification incidenceincreased

threefold from 43/100 000 per year persons in 1991

to 150/100 000 per year in 1997 before dropping to

77/100 000 peryear in 2011, reflecting changesin

hepatitis C notifications.

VBDs

There were 137 817 VBD notifications (5·7% of notifi-

cations),67% being RRV infections (notifiable from

1993), 16% Barmah Forest virus infections (notifiable

from 1995),10% malaria,and 6% dengue (Fig.1f).

VBD notification incidence was 34/100 000 per year

for Australia,highestin the NT (175/100 000)and

Queensland(92/100 000)and lowest in Tasmania

(9/100 000) (Fig. 2f).

Other bacterial diseases

There were 36 960 notifications of other bacterial dis-

eases,of which 60% were tuberculosis,24% invasive

meningococcaldisease,and 15% legionellosis.Other

bacterialdisease notification incidence was 9/100 000

per year,highestin the NT (27/100 000)and lowest

in Tasmania (5/100 000)(Fig. 2). Tuberculosis

notification incidencewas 6/100 000per year for

Australia (range 21/100 000 in the NT to 2/100 000

in Tasmania)and was stable over the study period

(Supplementary Appendix Fig. A1). Fifty-five percent

of notified caseswere male;highestfor Legionella

(67%) and leprosy (62%).

Zoonotic diseases

There were 17 696 zoonotic disease notifications (0·7%

of all notifications). Q fever was most common (61%),

followed by leptospirosis (20%) and ornithosis (14%).

Males predominated, especially for anthrax (100% of

four casesnotified),leptospirosis(90%),brucellosis

(84%), and Q fever (80%). Queenslandnotified

43% of all zoonotic cases,83% of brucellosisand

56% of leptospirosis cases.Zoonotic disease notifica-

tion incidence was4·4/100 000 peryear;highestin

Queensland (10·0/100 000)and lowestin the ACT

(0·6/100 000) (Fig.2h).Zoonotic disease notifications

fell by an average3% annually (Supplementary

Appendix Fig. A1).

DISCUSSION

Intelligenceobtained from nationalcommunicable

disease surveillance regarding infectious disease epi-

demiology guidesnationalpolicy development,re-

source allocation,diseasecontrolprogrammesand

quarantine activities, as well as allowing identification

of and coordinated responses to national or multijur-

isdictional outbreaks [3]. This paper provides the first

trend analysis ofall nationally notifiable diseases in

Notifiable diseases, Australia 1991–20113273

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

5% (9/100 000 per year)(Fig. 1b).Annual incidence

of STIs was highestin those aged 20–29 years

(239/100 000)and was eightfold higherin the NT

than the national average(1527vs. 193/100 000)

(Fig. 2b).

Gastrointestinal diseases

Gastrointestinaldiseases comprised 21% ofnotifica-

tions, with campylobacteriosisaccounting for55%

despite notbeing notifiable in NSW (Fig.1c). The

national incidence of notified gastrointestinal diseases

increased by 2% peryear. Gastrointestinaldisease

notificationsin the NT were nearly fourtimesthe

national incidence(481 vs. 127/100 000per year,

Fig. 2c).NSW had the lowestnotification incidence

(Supplementary Appendix Fig. A1); however, nation-

al notification incidence of gastrointestinal diseases ex-

cluding campylobacteriosis (55/100 000 per year) was

similar to NSW (43/100 000 per year).

VPDs

Just underhalf a million VPD caseswere notified

(Table 2), of which 45% were pertussis, 28% influenza

(notifiablefrom 2001), and 12% varicella zoster

(notifiable from 2006)(Fig. 1d). VPD notifications

increased 15% peryear, from 3016 in 1991 to a

peak of 101 942 casesin 2009 during the H1N1

influenzapandemic.Median age at diseaseonset

increased from 14 yearsin 1991–1997 to 30 years

in 2005–2011.National incidence ofVPD notifica-

tions was 119/100 000 peryear,highestin the NT

(239/100 000)and lowest in Victoria (77/100 000)

(Fig. 2d).

BBVH

BBVH comprised 18% of notifications nationally and

30% of notifications in NSW (Supplementary Appen-

dix Fig. A1). Annual incidence ofnotified BBVH

cases was higher in the NT and NSW (144 and 128

notifications/100 000, respectively) than other jurisdic-

tions (64–101/100 000, Fig. 2e). Hepatitis C, notifiable

from 1995,accounted for 69% and hepatitis B 31%

(Fig. 1e). BBVH notification incidenceincreased

threefold from 43/100 000 per year persons in 1991

to 150/100 000 per year in 1997 before dropping to

77/100 000 peryear in 2011, reflecting changesin

hepatitis C notifications.

VBDs

There were 137 817 VBD notifications (5·7% of notifi-

cations),67% being RRV infections (notifiable from

1993), 16% Barmah Forest virus infections (notifiable

from 1995),10% malaria,and 6% dengue (Fig.1f).

VBD notification incidence was 34/100 000 per year

for Australia,highestin the NT (175/100 000)and

Queensland(92/100 000)and lowest in Tasmania

(9/100 000) (Fig. 2f).

Other bacterial diseases

There were 36 960 notifications of other bacterial dis-

eases,of which 60% were tuberculosis,24% invasive

meningococcaldisease,and 15% legionellosis.Other

bacterialdisease notification incidence was 9/100 000

per year,highestin the NT (27/100 000)and lowest

in Tasmania (5/100 000)(Fig. 2). Tuberculosis

notification incidencewas 6/100 000per year for

Australia (range 21/100 000 in the NT to 2/100 000

in Tasmania)and was stable over the study period

(Supplementary Appendix Fig. A1). Fifty-five percent

of notified caseswere male;highestfor Legionella

(67%) and leprosy (62%).

Zoonotic diseases

There were 17 696 zoonotic disease notifications (0·7%

of all notifications). Q fever was most common (61%),

followed by leptospirosis (20%) and ornithosis (14%).

Males predominated, especially for anthrax (100% of

four casesnotified),leptospirosis(90%),brucellosis

(84%), and Q fever (80%). Queenslandnotified

43% of all zoonotic cases,83% of brucellosisand

56% of leptospirosis cases.Zoonotic disease notifica-

tion incidence was4·4/100 000 peryear;highestin

Queensland (10·0/100 000)and lowestin the ACT

(0·6/100 000) (Fig.2h).Zoonotic disease notifications

fell by an average3% annually (Supplementary

Appendix Fig. A1).

DISCUSSION

Intelligenceobtained from nationalcommunicable

disease surveillance regarding infectious disease epi-

demiology guidesnationalpolicy development,re-

source allocation,diseasecontrolprogrammesand

quarantine activities, as well as allowing identification

of and coordinated responses to national or multijur-

isdictional outbreaks [3]. This paper provides the first

trend analysis ofall nationally notifiable diseases in

Notifiable diseases, Australia 1991–20113273

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

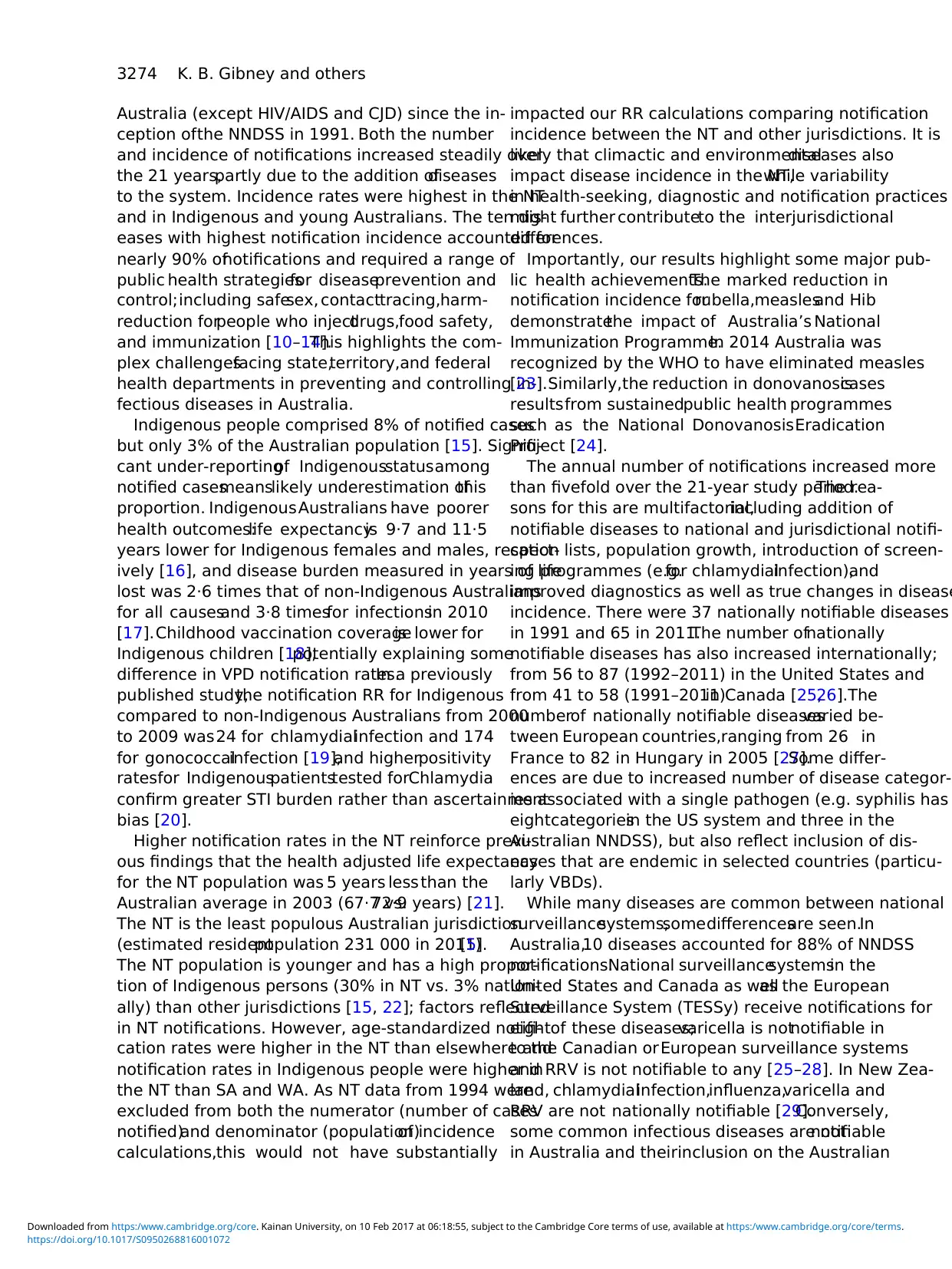

Australia (except HIV/AIDS and CJD) since the in-

ception ofthe NNDSS in 1991. Both the number

and incidence of notifications increased steadily over

the 21 years,partly due to the addition ofdiseases

to the system. Incidence rates were highest in the NT

and in Indigenous and young Australians. The ten dis-

eases with highest notification incidence accounted for

nearly 90% ofnotifications and required a range of

public health strategiesfor diseaseprevention and

control;including safesex, contacttracing,harm-

reduction forpeople who injectdrugs,food safety,

and immunization [10–14].This highlights the com-

plex challengesfacing state,territory,and federal

health departments in preventing and controlling in-

fectious diseases in Australia.

Indigenous people comprised 8% of notified cases

but only 3% of the Australian population [15]. Signifi-

cant under-reportingof Indigenousstatusamong

notified casesmeanslikely underestimation ofthis

proportion. IndigenousAustralians have poorer

health outcomes:life expectancyis 9·7 and 11·5

years lower for Indigenous females and males, respect-

ively [16], and disease burden measured in years of life

lost was 2·6 times that of non-Indigenous Australians

for all causesand 3·8 timesfor infectionsin 2010

[17].Childhood vaccination coverageis lower for

Indigenous children [18],potentially explaining some

difference in VPD notification rates.In a previously

published study,the notification RR for Indigenous

compared to non-Indigenous Australians from 2000

to 2009 was24 for chlamydialinfection and 174

for gonococcalinfection [19],and higherpositivity

ratesfor Indigenouspatientstested forChlamydia

confirm greater STI burden rather than ascertainment

bias [20].

Higher notification rates in the NT reinforce previ-

ous findings that the health adjusted life expectancy

for the NT population was 5 years less than the

Australian average in 2003 (67·7 vs.72·9 years) [21].

The NT is the least populous Australian jurisdiction

(estimated residentpopulation 231 000 in 2011)[5].

The NT population is younger and has a high propor-

tion of Indigenous persons (30% in NT vs. 3% nation-

ally) than other jurisdictions [15, 22]; factors reflected

in NT notifications. However, age-standardized notifi-

cation rates were higher in the NT than elsewhere and

notification rates in Indigenous people were higher in

the NT than SA and WA. As NT data from 1994 were

excluded from both the numerator (number of cases

notified)and denominator (population)of incidence

calculations,this would not have substantially

impacted our RR calculations comparing notification

incidence between the NT and other jurisdictions. It is

likely that climactic and environmentaldiseases also

impact disease incidence in the NT,while variability

in health-seeking, diagnostic and notification practices

might further contributeto the interjurisdictional

differences.

Importantly, our results highlight some major pub-

lic health achievements.The marked reduction in

notification incidence forrubella,measlesand Hib

demonstratethe impact of Australia’s National

Immunization Programme.In 2014 Australia was

recognized by the WHO to have eliminated measles

[23].Similarly,the reduction in donovanosiscases

resultsfrom sustainedpublic health programmes

such as the National DonovanosisEradication

Project [24].

The annual number of notifications increased more

than fivefold over the 21-year study period.The rea-

sons for this are multifactorial,including addition of

notifiable diseases to national and jurisdictional notifi-

cation lists, population growth, introduction of screen-

ing programmes (e.g.for chlamydialinfection),and

improved diagnostics as well as true changes in disease

incidence. There were 37 nationally notifiable diseases

in 1991 and 65 in 2011.The number ofnationally

notifiable diseases has also increased internationally;

from 56 to 87 (1992–2011) in the United States and

from 41 to 58 (1991–2011)in Canada [25,26].The

numberof nationally notifiable diseasesvaried be-

tween European countries,ranging from 26 in

France to 82 in Hungary in 2005 [27].Some differ-

ences are due to increased number of disease categor-

ies associated with a single pathogen (e.g. syphilis has

eightcategoriesin the US system and three in the

Australian NNDSS), but also reflect inclusion of dis-

eases that are endemic in selected countries (particu-

larly VBDs).

While many diseases are common between national

surveillancesystems,somedifferencesare seen.In

Australia,10 diseases accounted for 88% of NNDSS

notifications.National surveillancesystemsin the

United States and Canada as wellas the European

Surveillance System (TESSy) receive notifications for

eightof these diseases;varicella is notnotifiable in

to the Canadian orEuropean surveillance systems

and RRV is not notifiable to any [25–28]. In New Zea-

land, chlamydialinfection,influenza,varicella and

RRV are not nationally notifiable [29].Conversely,

some common infectious diseases are notnotifiable

in Australia and theirinclusion on the Australian

3274 K. B. Gibney and others

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001072

Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Kainan University, on 10 Feb 2017 at 06:18:55, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

ception ofthe NNDSS in 1991. Both the number

and incidence of notifications increased steadily over

the 21 years,partly due to the addition ofdiseases

to the system. Incidence rates were highest in the NT

and in Indigenous and young Australians. The ten dis-

eases with highest notification incidence accounted for

nearly 90% ofnotifications and required a range of

public health strategiesfor diseaseprevention and

control;including safesex, contacttracing,harm-

reduction forpeople who injectdrugs,food safety,

and immunization [10–14].This highlights the com-

plex challengesfacing state,territory,and federal

health departments in preventing and controlling in-

fectious diseases in Australia.

Indigenous people comprised 8% of notified cases

but only 3% of the Australian population [15]. Signifi-

cant under-reportingof Indigenousstatusamong

notified casesmeanslikely underestimation ofthis

proportion. IndigenousAustralians have poorer

health outcomes:life expectancyis 9·7 and 11·5

years lower for Indigenous females and males, respect-

ively [16], and disease burden measured in years of life

lost was 2·6 times that of non-Indigenous Australians

for all causesand 3·8 timesfor infectionsin 2010

[17].Childhood vaccination coverageis lower for

Indigenous children [18],potentially explaining some

difference in VPD notification rates.In a previously

published study,the notification RR for Indigenous

compared to non-Indigenous Australians from 2000

to 2009 was24 for chlamydialinfection and 174

for gonococcalinfection [19],and higherpositivity

ratesfor Indigenouspatientstested forChlamydia

confirm greater STI burden rather than ascertainment

bias [20].

Higher notification rates in the NT reinforce previ-

ous findings that the health adjusted life expectancy

for the NT population was 5 years less than the

Australian average in 2003 (67·7 vs.72·9 years) [21].

The NT is the least populous Australian jurisdiction