NOVA: The Pluto Files Report

VerifiedAdded on 2019/09/30

|19

|9934

|890

Report

AI Summary

This report details the content of NOVA's documentary, "The Pluto Files." The documentary follows Neil deGrasse Tyson's investigation into the public and scientific reaction to Pluto's reclassification as a dwarf planet. It explores the history of Pluto's discovery by Clyde Tombaugh, the role of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in defining planets, and the scientific arguments for and against Pluto's planetary status. The film features interviews with scientists, historians, and members of the Tombaugh family, showcasing diverse perspectives on the issue. The debate highlights the complexities of scientific classification and the emotional attachment people have to celestial objects. The documentary also touches upon the discovery of the Kuiper Belt and other trans-Neptunian objects, which further complicated the definition of a planet. The report concludes with the ongoing discussion and lack of complete consensus regarding Pluto's classification.

The Pluto Files

PBS Airdate: March 2, 2010

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON (American Museum of Natural History, Hayden Planetarium): In 1930, a farm

boy, with a passion for the universe, notices a tiny dot moving across the night sky. He discovers Pluto,

four billion miles from the Sun and cloaked in darkness.

Pluto is a mystery. Our best images are nothing more than a blur, and many scientists are arguing over

whether it's even a planet.

MARK SYKES (Planetary Science Institute): When we fly our spaceship to Pluto, we'll arrive at a round

world.

BRIAN G. MARSDEN (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics):I'm able to use the word "world," if

you like, but "planet?"

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: The scientific debate over Pluto has even caused a media frenzy.

STEPHEN COLBERT (The Colbert Report/Film Clip from August 17, 2006): I'm sorry, I thought planets

might be one of the constants in life.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Pluto-lovers of America have taken to the streets.

PROTESTORS (News Clip): Pluto forever!

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: What is Pluto? A new mission to the far reaches of the solar system promises to

answer this question and more.

ALAN STERN (Southwest Research Institute): It's true first-time exploration. Pluto is going to be revealed

in all of its glory.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Join me, Neil deGrasse Tyson, on a journey to explore America's favorite

planet...

TOMBAUGH FAMILY MEMBERS (A small group speaking simultaneously): Hi.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: ...and find out why some people are blaming Pluto's problems on me.

SODY (Streator, Illinois Barber): So how do you feel about Pluto, Dr. Tyson?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: These are The Pluto Files, next on NOVA.

For more than 75 years, the great stage of our solar system had a familiar cast of characters, nine

players in all. We even memorized their names: Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars (the rocky planets),

Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, (those gas giants), and all the way out at the very edge of the solar

system, perhaps the most popular player of all, a lonely little misfit planet: Pluto.

But recently, Pluto lost its starring role, and some folks are blaming that on me. I, Neil deGrasse Tyson,

director of the Hayden Planetarium, in New York City, have been accused of being a Pluto-hater. Back in

2000, when my colleagues and I were designing this place, instead of exhibiting Pluto here, with planets

like Earth and Mars, or up there, with giants like Jupiter and Saturn, we decided to boldly go where no

PBS Airdate: March 2, 2010

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON (American Museum of Natural History, Hayden Planetarium): In 1930, a farm

boy, with a passion for the universe, notices a tiny dot moving across the night sky. He discovers Pluto,

four billion miles from the Sun and cloaked in darkness.

Pluto is a mystery. Our best images are nothing more than a blur, and many scientists are arguing over

whether it's even a planet.

MARK SYKES (Planetary Science Institute): When we fly our spaceship to Pluto, we'll arrive at a round

world.

BRIAN G. MARSDEN (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics):I'm able to use the word "world," if

you like, but "planet?"

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: The scientific debate over Pluto has even caused a media frenzy.

STEPHEN COLBERT (The Colbert Report/Film Clip from August 17, 2006): I'm sorry, I thought planets

might be one of the constants in life.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Pluto-lovers of America have taken to the streets.

PROTESTORS (News Clip): Pluto forever!

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: What is Pluto? A new mission to the far reaches of the solar system promises to

answer this question and more.

ALAN STERN (Southwest Research Institute): It's true first-time exploration. Pluto is going to be revealed

in all of its glory.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Join me, Neil deGrasse Tyson, on a journey to explore America's favorite

planet...

TOMBAUGH FAMILY MEMBERS (A small group speaking simultaneously): Hi.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: ...and find out why some people are blaming Pluto's problems on me.

SODY (Streator, Illinois Barber): So how do you feel about Pluto, Dr. Tyson?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: These are The Pluto Files, next on NOVA.

For more than 75 years, the great stage of our solar system had a familiar cast of characters, nine

players in all. We even memorized their names: Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars (the rocky planets),

Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, (those gas giants), and all the way out at the very edge of the solar

system, perhaps the most popular player of all, a lonely little misfit planet: Pluto.

But recently, Pluto lost its starring role, and some folks are blaming that on me. I, Neil deGrasse Tyson,

director of the Hayden Planetarium, in New York City, have been accused of being a Pluto-hater. Back in

2000, when my colleagues and I were designing this place, instead of exhibiting Pluto here, with planets

like Earth and Mars, or up there, with giants like Jupiter and Saturn, we decided to boldly go where no

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

planetarium had gone before and put Pluto far, far away, all the way downstairs, with a group of newly

discovered icy objects in the outer solar system.

If you look hard enough you can find it, right here.

Little did I know how much this decision would change my life. My troubles began with the astute

observations of one young visitor...

BOY (Visitor to Hayden Planetarium): I can't find Pluto!

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: ...who, just my luck, was overheard by an off-duty journalist from the New York

Times. He decides this is a great story, so he calls his Times colleague, science writer Kenneth Chang, and

he's shocked.

KENNETH CHANG (The New York Times): Well, I was looking for Pluto, and I couldn't find it. You look

everywhere, and you see eight planets, not nine.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: A few days later Chang's story hits the front page, right beneath George W.'s

inauguration. The headline reads, "Pluto's Not a Planet? Only in New York."

I received angry emails and a ton of letters, especially from pissed off third-graders.

EMERSON YORK (Dramatized reading of letter from a third grader):Dear Natural History Museum, Pluto

is my favorite planet!!!

MADELINE TROST (Dramatized reading): Why can't Pluto be a planet? Please write back, but not in

cursive, because I can't read in cursive.

MICHAEL NOVACEK (American Museum of Natural History): I thought, "Oh, my gosh. Kids will probably

go to this exhibit and cry because Pluto's no longer a planet."

SOLEDAD O'BRIEN (NBC News Anchor): Could it be the final indignity for the farthest and smallest

planet in our solar system?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Our exhibit had stirred up a media frenzy.

JON STEWART (The Daily Show/Film Clip from January 8, 2009): Pluto was, since 1930, was a planet. He

had stature; he had friends. You come along and say "Da, da, da, da, da."

DIANE SAWYER (ABC News Anchor): Neil deGrasse Tyson, you have left a void in the universe, as big as

Pluto.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON (The Colbert Report/Film Clip from August 17, 2006): I never wanted to kick

Pluto out of the solar system. I just wanted to group it with its icy brethren.

STEPHEN COLBERT (The Colbert Report/Film Clip from August 17, 2006): You're saying Pluto should be

with its own kind, separate but equal?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON (The Colbert Report/Film Clip from August 17, 2006): Yeah, I guess it comes out

that way, doesn't it?

discovered icy objects in the outer solar system.

If you look hard enough you can find it, right here.

Little did I know how much this decision would change my life. My troubles began with the astute

observations of one young visitor...

BOY (Visitor to Hayden Planetarium): I can't find Pluto!

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: ...who, just my luck, was overheard by an off-duty journalist from the New York

Times. He decides this is a great story, so he calls his Times colleague, science writer Kenneth Chang, and

he's shocked.

KENNETH CHANG (The New York Times): Well, I was looking for Pluto, and I couldn't find it. You look

everywhere, and you see eight planets, not nine.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: A few days later Chang's story hits the front page, right beneath George W.'s

inauguration. The headline reads, "Pluto's Not a Planet? Only in New York."

I received angry emails and a ton of letters, especially from pissed off third-graders.

EMERSON YORK (Dramatized reading of letter from a third grader):Dear Natural History Museum, Pluto

is my favorite planet!!!

MADELINE TROST (Dramatized reading): Why can't Pluto be a planet? Please write back, but not in

cursive, because I can't read in cursive.

MICHAEL NOVACEK (American Museum of Natural History): I thought, "Oh, my gosh. Kids will probably

go to this exhibit and cry because Pluto's no longer a planet."

SOLEDAD O'BRIEN (NBC News Anchor): Could it be the final indignity for the farthest and smallest

planet in our solar system?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Our exhibit had stirred up a media frenzy.

JON STEWART (The Daily Show/Film Clip from January 8, 2009): Pluto was, since 1930, was a planet. He

had stature; he had friends. You come along and say "Da, da, da, da, da."

DIANE SAWYER (ABC News Anchor): Neil deGrasse Tyson, you have left a void in the universe, as big as

Pluto.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON (The Colbert Report/Film Clip from August 17, 2006): I never wanted to kick

Pluto out of the solar system. I just wanted to group it with its icy brethren.

STEPHEN COLBERT (The Colbert Report/Film Clip from August 17, 2006): You're saying Pluto should be

with its own kind, separate but equal?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON (The Colbert Report/Film Clip from August 17, 2006): Yeah, I guess it comes out

that way, doesn't it?

STEPHEN COLBERT (The Colbert Report/Film Clip from August 17, 2006): Neil deGrasse Tyson has

betrayed us.

BRIAN WILLIAMS(NBC News Anchor): He has thrown his weight around a little too much. He's not the

boss of the solar system; he's not the boss of me.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: If Neptune or Mercury had been reclassified, I don't think anyone would cared,

but the fact that it happened to Pluto seems to make all the difference.

Pluto has a remarkable grip on the hearts and minds of the American public and the press. Even my

colleagues in astrophysics are still arguing over what to do with Pluto, and I don't really know why. But

I'm determined to find out.

This is the story of my journey. These are The Pluto Files.

My first stop took me to Cambridge, Massachusetts. A visit to the hallowed halls of Harvard just might

help me make sense of this Pluto problem.

Welcome to the Harvard University football field. I brought a few props along with me, much to the

surprise of my colleagues.

Astrophysicist, Brian Marsden, doesn't think Pluto is a planet, while planetary scientist Mark Sykes thinks

it definitely is. And the esteemed historian of science, Owen Gingerich, is looking for the middle ground.

MARK SYKES: Okay, Neil. What are we doing here?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: We're making a scale model of the solar system, right here on this playing field.

So grab one of these. Let's do it.

To evaluate Pluto's planetary status we need to take a closer look at how it compares with the heavy

hitters on the solar system team. The planets are millions, even billions of miles apart, so this scale

model can't accurately depict their distance from one another, but it can show their relative size.

If this eight-foot balloon represents our Sun, how does Pluto size up against the rest of the team? Let's

find out.

Mark, first up, Mercury.

MARK SYKES: Mercury.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Represented by a bead—in correct size, relative to the Sun—miniscule Mercury

may be small, but its diameter is still twice as big as puny Pluto's.

Next up, Venus. Will you have the honor?

Venus, represented by this tiny rubber ball, has a diameter five times as big as Pluto.

MARK SYKES: Earth.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Earth.

Earth, the big blue marble, is six times as wide as Pluto.

betrayed us.

BRIAN WILLIAMS(NBC News Anchor): He has thrown his weight around a little too much. He's not the

boss of the solar system; he's not the boss of me.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: If Neptune or Mercury had been reclassified, I don't think anyone would cared,

but the fact that it happened to Pluto seems to make all the difference.

Pluto has a remarkable grip on the hearts and minds of the American public and the press. Even my

colleagues in astrophysics are still arguing over what to do with Pluto, and I don't really know why. But

I'm determined to find out.

This is the story of my journey. These are The Pluto Files.

My first stop took me to Cambridge, Massachusetts. A visit to the hallowed halls of Harvard just might

help me make sense of this Pluto problem.

Welcome to the Harvard University football field. I brought a few props along with me, much to the

surprise of my colleagues.

Astrophysicist, Brian Marsden, doesn't think Pluto is a planet, while planetary scientist Mark Sykes thinks

it definitely is. And the esteemed historian of science, Owen Gingerich, is looking for the middle ground.

MARK SYKES: Okay, Neil. What are we doing here?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: We're making a scale model of the solar system, right here on this playing field.

So grab one of these. Let's do it.

To evaluate Pluto's planetary status we need to take a closer look at how it compares with the heavy

hitters on the solar system team. The planets are millions, even billions of miles apart, so this scale

model can't accurately depict their distance from one another, but it can show their relative size.

If this eight-foot balloon represents our Sun, how does Pluto size up against the rest of the team? Let's

find out.

Mark, first up, Mercury.

MARK SYKES: Mercury.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Represented by a bead—in correct size, relative to the Sun—miniscule Mercury

may be small, but its diameter is still twice as big as puny Pluto's.

Next up, Venus. Will you have the honor?

Venus, represented by this tiny rubber ball, has a diameter five times as big as Pluto.

MARK SYKES: Earth.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Earth.

Earth, the big blue marble, is six times as wide as Pluto.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

If Earth and Venus were about an inch, Mars would be about a half inch—the sizes of these gumdrops,

relative to the Sun. But it still trounces Pluto, three to one.

MARK SYKES: Jupiter, king of the planets.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: King of the planets. You have the honor.

MARK SYKES: There you go.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: The largest planet, King Jupiter, represented by a schoolyard kickball, is a

whopping 62 times as wide as pipsqueak Pluto.

Saturn...

MARK SYKES: Saturn.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: ...the size of a bowling ball, relative to the Sun.

Pluto doesn't fare much better against my favorite planet, Saturn, or its next-door neighbor.

MARK SYKES: Uranus.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Uranus, represented by a bocce ball.

Have you ever played bocce?

MARK SYKES: No, I never played bocce.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Neither have I.

It would take 22 Plutos in a chain to equal the diameter of one Uranus.

Croquet anyone?

What do you have now?

MARK SYKES: Neptune. Why don't you have the honor?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Big blue Neptune is 21 times as wide as Pluto.

Last and least...

MARK SYKES: And not least.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: ...we have Pluto, represented by a ball bearing, removed from a roller skate.

MARK SYKES: Sometimes the most valuable things are in the smallest packages.

Excellent.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Pluto.

Pluto's diameter is just under 1,500 miles. In fact, if it ever decided to visit America, it would stretch only

from California to Kansas. No matter how you look at it, Pluto makes a scrawny little planet.

Pluto's really puny, but so is Mercury.

relative to the Sun. But it still trounces Pluto, three to one.

MARK SYKES: Jupiter, king of the planets.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: King of the planets. You have the honor.

MARK SYKES: There you go.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: The largest planet, King Jupiter, represented by a schoolyard kickball, is a

whopping 62 times as wide as pipsqueak Pluto.

Saturn...

MARK SYKES: Saturn.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: ...the size of a bowling ball, relative to the Sun.

Pluto doesn't fare much better against my favorite planet, Saturn, or its next-door neighbor.

MARK SYKES: Uranus.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Uranus, represented by a bocce ball.

Have you ever played bocce?

MARK SYKES: No, I never played bocce.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Neither have I.

It would take 22 Plutos in a chain to equal the diameter of one Uranus.

Croquet anyone?

What do you have now?

MARK SYKES: Neptune. Why don't you have the honor?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Big blue Neptune is 21 times as wide as Pluto.

Last and least...

MARK SYKES: And not least.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: ...we have Pluto, represented by a ball bearing, removed from a roller skate.

MARK SYKES: Sometimes the most valuable things are in the smallest packages.

Excellent.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Pluto.

Pluto's diameter is just under 1,500 miles. In fact, if it ever decided to visit America, it would stretch only

from California to Kansas. No matter how you look at it, Pluto makes a scrawny little planet.

Pluto's really puny, but so is Mercury.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

BRIAN MARSDEN: Pluto's a lot punier: one-twentieth the mass of Mercury.

OWEN GINGERICH (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics):That's less than the mass of the

moon.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Touchdown right there.

If we were to keep score of Pluto's oddball traits versus its planet-like characteristics, how would it add

up?

Brian thinks Pluto's puny size disqualifies it from the planet team, so he gives one touchdown, and of

course the extra point, to Pluto, the oddball.

MARK SYKES: This is ridiculous.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Mark disagrees. For him, size is less important than shape.

Pluto, like every player on the planet team, is round, and not potato shaped, like nearly all asteroids.

This sequence of images, taken by the Hubble space telescope, shows Pluto as a sphere with a textured

surface.

MARK SYKES: When we fly our spaceship to Pluto, we will arrive at a round world that has atmospheres,

that has bright and dark areas on the surface. It will look much more like objects we call planets than

these little, irregular, inert objects we call asteroids.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So roundness, you give a full touchdown?

MARK SYKES: Yeah.

OWEN GINGERICH: Two touchdowns.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: But, then again, we all know that Pluto's got this really weird orbit. First of all,

it's tipped, the most tipped orbit. What's that worth to you?

BRIAN MARSDEN: Not too much.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: A field goal, not quite a touchdown.

BRIAN MARSDEN: That isn't really the problem. I think the problem was crossing the orbit of Neptune.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Pluto's orbit isn't just tipped; it's highly elliptical, not nearly circular like other

planets', which actually forces Pluto to cross the orbit of another planet. That's bad?

BRIAN MARSDEN: That's really bad.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Nobody else does that. There you go, touchdown right there, another seven

points for the oddball team.

One way you might define a planet is that it ought to have a moon. But, of course, Mercury and Venus

don't have moons, and guess what? Tiny little Pluto does. In fact, it has three.

One of those moons, Charon, is so large compared with Pluto that they both orbit a point in space in

between them, which might make you wonder which one is the planet.

OWEN GINGERICH (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics):That's less than the mass of the

moon.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Touchdown right there.

If we were to keep score of Pluto's oddball traits versus its planet-like characteristics, how would it add

up?

Brian thinks Pluto's puny size disqualifies it from the planet team, so he gives one touchdown, and of

course the extra point, to Pluto, the oddball.

MARK SYKES: This is ridiculous.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Mark disagrees. For him, size is less important than shape.

Pluto, like every player on the planet team, is round, and not potato shaped, like nearly all asteroids.

This sequence of images, taken by the Hubble space telescope, shows Pluto as a sphere with a textured

surface.

MARK SYKES: When we fly our spaceship to Pluto, we will arrive at a round world that has atmospheres,

that has bright and dark areas on the surface. It will look much more like objects we call planets than

these little, irregular, inert objects we call asteroids.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So roundness, you give a full touchdown?

MARK SYKES: Yeah.

OWEN GINGERICH: Two touchdowns.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: But, then again, we all know that Pluto's got this really weird orbit. First of all,

it's tipped, the most tipped orbit. What's that worth to you?

BRIAN MARSDEN: Not too much.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: A field goal, not quite a touchdown.

BRIAN MARSDEN: That isn't really the problem. I think the problem was crossing the orbit of Neptune.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Pluto's orbit isn't just tipped; it's highly elliptical, not nearly circular like other

planets', which actually forces Pluto to cross the orbit of another planet. That's bad?

BRIAN MARSDEN: That's really bad.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Nobody else does that. There you go, touchdown right there, another seven

points for the oddball team.

One way you might define a planet is that it ought to have a moon. But, of course, Mercury and Venus

don't have moons, and guess what? Tiny little Pluto does. In fact, it has three.

One of those moons, Charon, is so large compared with Pluto that they both orbit a point in space in

between them, which might make you wonder which one is the planet.

MARK SYKES: The idea of planets orbiting planets isn't really so foreign. We see many double stars out

there, and we see galaxies orbiting galaxies.

OWEN GINGERICH: The solar system is such a complicated place, it's very important to understand that

there is this richness out there.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So, Brian, if we go there and find Pluto has mountains or craters or an

atmosphere, it's got world properties that match other objects we're happy to call planets.

BRIAN MARSDEN: I'm able to use the word "world," if you like, but "planet?"

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So then, what is Pluto?

Four billion miles from the Sun, our best images of Pluto and its moons are nothing more than a blur. By

analyzing the light reflected from Pluto's surface, planetary scientists think that a day on Pluto might

look like this: an icy, frosty, winter's night in the Arctic; the Sun, a tiny pinpoint in a pitch black sky; wispy

clouds and fog visible on the horizon; the temperature about 300 degrees below zero.

No spacecraft has yet visited Pluto. Until one does it will remain a mystery.

Both of you are wrong, and no scoreboard today is going to change that.

It was time for me to take a closer look at why an oddball like Pluto was considered a planet in the first

place. It's a tale that begins back in 1894, when a New England aristocrat by the name of Percival Lowell

built a private observatory, near Flagstaff, Arizona, with one goal in mind: to find life on Mars.

After years of searching in vein, Lowell turned his attention to an unsolved mystery, the hunt for a

distant planet whose gravity seemed to be causing disturbances in Neptune's orbit. He called this

hypothetical object "Planet X." Lowell spent the rest of his life trying to find it but never did.

After his death, the task was given to the unlikeliest of planet-hunters, a self-educated farm boy who

attended a one-room schoolhouse. Clyde Tombaugh's first job in astronomy included cleaning

telescopes and sweeping up at the Lowell Observatory. He spent the rest of his time searching for the

mysterious Planet X.

Every few nights, he placed a photosensitive glass plate on the telescope, securing it so it would not

shift. Then he exposed the plate for two hours to the universe. During that time, the motorized

telescope slowly moved to compensate for Earth's rotation.

Several days later, he'd retrace his steps, taking pictures of the same section of the sky he had

photographed earlier. Then, using an ingenious device called a "blink comparator," Clyde Tombaugh

aligned the two images to carefully examine their differences. The blink comparator enabled him to shift

back and forth, searching for the subtlest of changes. Although the human eye is good at spotting

differences, finding a dim celestial object, billions of miles away was a daunting task.

After searching for almost a year, a determined Clyde finally found a tiny dot slowly moving across the

night's sky.

Can you see it? Here it is.

there, and we see galaxies orbiting galaxies.

OWEN GINGERICH: The solar system is such a complicated place, it's very important to understand that

there is this richness out there.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So, Brian, if we go there and find Pluto has mountains or craters or an

atmosphere, it's got world properties that match other objects we're happy to call planets.

BRIAN MARSDEN: I'm able to use the word "world," if you like, but "planet?"

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So then, what is Pluto?

Four billion miles from the Sun, our best images of Pluto and its moons are nothing more than a blur. By

analyzing the light reflected from Pluto's surface, planetary scientists think that a day on Pluto might

look like this: an icy, frosty, winter's night in the Arctic; the Sun, a tiny pinpoint in a pitch black sky; wispy

clouds and fog visible on the horizon; the temperature about 300 degrees below zero.

No spacecraft has yet visited Pluto. Until one does it will remain a mystery.

Both of you are wrong, and no scoreboard today is going to change that.

It was time for me to take a closer look at why an oddball like Pluto was considered a planet in the first

place. It's a tale that begins back in 1894, when a New England aristocrat by the name of Percival Lowell

built a private observatory, near Flagstaff, Arizona, with one goal in mind: to find life on Mars.

After years of searching in vein, Lowell turned his attention to an unsolved mystery, the hunt for a

distant planet whose gravity seemed to be causing disturbances in Neptune's orbit. He called this

hypothetical object "Planet X." Lowell spent the rest of his life trying to find it but never did.

After his death, the task was given to the unlikeliest of planet-hunters, a self-educated farm boy who

attended a one-room schoolhouse. Clyde Tombaugh's first job in astronomy included cleaning

telescopes and sweeping up at the Lowell Observatory. He spent the rest of his time searching for the

mysterious Planet X.

Every few nights, he placed a photosensitive glass plate on the telescope, securing it so it would not

shift. Then he exposed the plate for two hours to the universe. During that time, the motorized

telescope slowly moved to compensate for Earth's rotation.

Several days later, he'd retrace his steps, taking pictures of the same section of the sky he had

photographed earlier. Then, using an ingenious device called a "blink comparator," Clyde Tombaugh

aligned the two images to carefully examine their differences. The blink comparator enabled him to shift

back and forth, searching for the subtlest of changes. Although the human eye is good at spotting

differences, finding a dim celestial object, billions of miles away was a daunting task.

After searching for almost a year, a determined Clyde finally found a tiny dot slowly moving across the

night's sky.

Can you see it? Here it is.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

A month later, the Lowell Observatory proudly announced that a young assistant had fulfilled Percival

Lowell's dream. Clyde Tombaugh had finally found Planet X.

The day after the announcement, the news hit the front page of the New York Times. Soon the discovery

was heralded worldwide, but the new planet needed a name.

Across the Atlantic, an 11-year-old English schoolgirl would come up with one. On March 14, 1930,

Venetia Burney's grandfather, a librarian at Oxford, was reading the morning newspaper and came

across the story.

VENETIA BURNEY'S GRANDFATHER (Dramatization): An American has just discovered a new planet. I

wonder what they'll call it?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Venetia had just finished studying the Roman gods and jumped at the

opportunity to name it after the god of the underworld.

VENETIA BURNEY (Schoolgirl, Dramatization): They could call it Pluto.

VENETIA BURNEY'S GRANDFATHER: Pluto, perhaps. Yes.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Her grandfather thought that was a splendid idea. So he wrote a note to the

Lowell Observatory.

The director at Lowell liked it, especially because Pluto's official symbol would be the overlapping letters

P and L, the initials of the observatory's long-gone founder, the man who started the search for Planet X,

Percival Lowell.

For most Americans, the name Pluto didn't exactly conjure up affection. It was associated with a well-

known laxative called "Pluto Wate," a popular product that promised "relief from constipation in 30

minutes to two hours." Its slogan: "When Nature won't, Pluto will."

But the name would soon get a makeover, and it would come from a young animator by the name of

Walt Disney. Shortly after planet Pluto was discovered, the fledgling Disney Brothers Studio came up

with a new character, a playful bloodhound named Pluto the Pup. Walt probably wasn't thinking about

constipation when he named Mickey Mouse's new pal, back in 1931.

My journey would lead me south, to a magical place, to meet with a celebrity on a tight schedule.

Pluto, hey, great to see you. Thanks for making time for this. Can we pose for a picture?

Was Walt thinking "planet" when he gave his pup a name?

Maybe Roy Patrick Disney, Walt's great nephew, can help answer this question.

I wonder whether Walt jumped on the opportunity to name this new character after this new cosmic

object. Is there any evidence for that in the archives?

ROY P. DISNEY (Walt Disney's Great Nephew): There's no direct evidence. There's a lot of anecdotal

evidence. I think its fate; I don't think it's an accident.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: You feel, deep inside, that Walt was thinking planet?

Lowell's dream. Clyde Tombaugh had finally found Planet X.

The day after the announcement, the news hit the front page of the New York Times. Soon the discovery

was heralded worldwide, but the new planet needed a name.

Across the Atlantic, an 11-year-old English schoolgirl would come up with one. On March 14, 1930,

Venetia Burney's grandfather, a librarian at Oxford, was reading the morning newspaper and came

across the story.

VENETIA BURNEY'S GRANDFATHER (Dramatization): An American has just discovered a new planet. I

wonder what they'll call it?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Venetia had just finished studying the Roman gods and jumped at the

opportunity to name it after the god of the underworld.

VENETIA BURNEY (Schoolgirl, Dramatization): They could call it Pluto.

VENETIA BURNEY'S GRANDFATHER: Pluto, perhaps. Yes.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Her grandfather thought that was a splendid idea. So he wrote a note to the

Lowell Observatory.

The director at Lowell liked it, especially because Pluto's official symbol would be the overlapping letters

P and L, the initials of the observatory's long-gone founder, the man who started the search for Planet X,

Percival Lowell.

For most Americans, the name Pluto didn't exactly conjure up affection. It was associated with a well-

known laxative called "Pluto Wate," a popular product that promised "relief from constipation in 30

minutes to two hours." Its slogan: "When Nature won't, Pluto will."

But the name would soon get a makeover, and it would come from a young animator by the name of

Walt Disney. Shortly after planet Pluto was discovered, the fledgling Disney Brothers Studio came up

with a new character, a playful bloodhound named Pluto the Pup. Walt probably wasn't thinking about

constipation when he named Mickey Mouse's new pal, back in 1931.

My journey would lead me south, to a magical place, to meet with a celebrity on a tight schedule.

Pluto, hey, great to see you. Thanks for making time for this. Can we pose for a picture?

Was Walt thinking "planet" when he gave his pup a name?

Maybe Roy Patrick Disney, Walt's great nephew, can help answer this question.

I wonder whether Walt jumped on the opportunity to name this new character after this new cosmic

object. Is there any evidence for that in the archives?

ROY P. DISNEY (Walt Disney's Great Nephew): There's no direct evidence. There's a lot of anecdotal

evidence. I think its fate; I don't think it's an accident.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: You feel, deep inside, that Walt was thinking planet?

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ROY DISNEY: Yes. He was fascinated with space and space exploration. And Walt did four TV shows

about space. And all of them made space exploration and science accessible to kids, including myself.

LEONARD MALTIN (Film Critic and Historian): When he did his Man in Space series in 1956 to '57,

America wasn't committed to a space program. I know, for a fact, that many people who wound up

working at NASA were inspired to do so by watching those television shows. He made learning fun.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: I am certain Pluto, the dog, added some kind of warm and fuzzy feeling for this

cosmic object. Cosmic objects don't normally trigger warm and fuzzy feelings.

Pluto, have you ever looked through a telescope before? No? I brought one. Isn't it cool? Now it's

daytime, so you can't see much. But let me show you how it works.

What do you think of that? You see something?

You did? Try again.

Whether or not Walt was thinking about the cosmos when he named his dog, doesn't really matter.

Good boy! Good dog!

The seeds were sown for the tiniest of planets to get the kind of attention no other planet had, all

because of this loveable pup.

But I shouldn't give credit to the dog alone. Next stop on my journey: Streator Illinois, the hometown of

Clyde Tombaugh.

They love him so much, main street is named after him. There's a mural in the center of town that

compares his discovery of Pluto with the accomplishments of Copernicus and Galileo. His life is

chronicled at the local historical society, where one of his homemade telescopes is on display. There's

even a plaque dedicated to him in front of City Hall. Clyde is a local hero. Just about everyone around

here can tell you his life story.

SODY (Streator, Illinois Barber): Next victim, I mean, customer, please.

How you doing?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Doing well. Right now, I'm on a pilgrimage, actually, to try and understand Clyde

Tombaugh.

SODY: Clyde Tombaugh; he's from Streator, and he discovered Pluto.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: That's what I heard.

SODY: We're very proud of him, very proud of him, what he did.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: And you learned about him in high school?

TERRI (Streator, Illinois Resident): Elementary school...third grade maybe.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So that's when most people first learn about the planets. So his name comes

up, and you learn he's a local guy.

about space. And all of them made space exploration and science accessible to kids, including myself.

LEONARD MALTIN (Film Critic and Historian): When he did his Man in Space series in 1956 to '57,

America wasn't committed to a space program. I know, for a fact, that many people who wound up

working at NASA were inspired to do so by watching those television shows. He made learning fun.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: I am certain Pluto, the dog, added some kind of warm and fuzzy feeling for this

cosmic object. Cosmic objects don't normally trigger warm and fuzzy feelings.

Pluto, have you ever looked through a telescope before? No? I brought one. Isn't it cool? Now it's

daytime, so you can't see much. But let me show you how it works.

What do you think of that? You see something?

You did? Try again.

Whether or not Walt was thinking about the cosmos when he named his dog, doesn't really matter.

Good boy! Good dog!

The seeds were sown for the tiniest of planets to get the kind of attention no other planet had, all

because of this loveable pup.

But I shouldn't give credit to the dog alone. Next stop on my journey: Streator Illinois, the hometown of

Clyde Tombaugh.

They love him so much, main street is named after him. There's a mural in the center of town that

compares his discovery of Pluto with the accomplishments of Copernicus and Galileo. His life is

chronicled at the local historical society, where one of his homemade telescopes is on display. There's

even a plaque dedicated to him in front of City Hall. Clyde is a local hero. Just about everyone around

here can tell you his life story.

SODY (Streator, Illinois Barber): Next victim, I mean, customer, please.

How you doing?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Doing well. Right now, I'm on a pilgrimage, actually, to try and understand Clyde

Tombaugh.

SODY: Clyde Tombaugh; he's from Streator, and he discovered Pluto.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: That's what I heard.

SODY: We're very proud of him, very proud of him, what he did.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: And you learned about him in high school?

TERRI (Streator, Illinois Resident): Elementary school...third grade maybe.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So that's when most people first learn about the planets. So his name comes

up, and you learn he's a local guy.

TERRI: "Streator boy makes good," so to speak. Back in third grade I went, "Wow, that's astounding:

from Streator, found Pluto."

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: You feel some pride?

TERRI: Oh, you bet. Always had something to point to as far as, "Looka there, that guy discovered Pluto,

and he's from our area."

ANOTHER STREATOR, ILLINOIS RESIDENT: Walt Disney named the dog after him.

SODY: So how do you feel about Pluto, Dr. Tyson?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: In the eyes of the town folk of Streator, Illinois, Tombaugh's discovery is not

only a part of their history, it's a piece of American history, as well as world history.

It was the ancient Greeks who classified what we call the Moon, the Sun, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter

and Saturn as "planetes," which means the "wanderers" in English. They imagined Earth as a hub around

which these planets revolved.

In 1543, the Polish astronomer Nicolas Copernicus published his revolutionary idea that the Sun did not

circle Earth, but, instead, Earth and its lone moon circle the Sun, along with the rest of the planets.

By the 17th century, the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei discovered Jupiter's four largest moons.

Meanwhile, Dutchman Christiaan Huygens identified Saturn's rings and discovered Titan, its largest

moon. Italian astronomer Giovanni Cassini one-upped him, when he discovered four more.

In the 18th century, Englishman William Herschel discovered Uranus, although he originally called it the

Georgian star, after his King, George the III. Can you imagine a planet named George?

The British and French are still fighting over who deserves the credit for predicting the location of

Neptune. Some give the honor to John Couch Adams, while others say Urbain Le Verrier deserves it. But

there's no doubt that German astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle found it.

The discovery of Pluto finally added an American, Clyde Tombaugh, to this short but esteemed list of

planet-hunters.

So the folks in Streator, Illinois, told me that in New Mexico...there are still some Tombaughs there.

That's where Clyde moved after discovering Pluto. Clyde's no longer with us, but his 97-year-old widow

and both his son and daughter still live there. So I decided I had to check it out.

Wow. That's a lot of Tombaughs.

THE TOMBAUGHS (A small group speaking simultaneously): Hi.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: How many of you are there? Hello, everyone.

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH (Clyde Tombaugh's Daughter): Annette Tombaugh. I'm Clyde's daughter.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: What an honor, my gosh.

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH: This is my brother.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH (Clyde Tombaugh's Son): Neil, Al Tombaugh. I'm Clyde's son.

from Streator, found Pluto."

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: You feel some pride?

TERRI: Oh, you bet. Always had something to point to as far as, "Looka there, that guy discovered Pluto,

and he's from our area."

ANOTHER STREATOR, ILLINOIS RESIDENT: Walt Disney named the dog after him.

SODY: So how do you feel about Pluto, Dr. Tyson?

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: In the eyes of the town folk of Streator, Illinois, Tombaugh's discovery is not

only a part of their history, it's a piece of American history, as well as world history.

It was the ancient Greeks who classified what we call the Moon, the Sun, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter

and Saturn as "planetes," which means the "wanderers" in English. They imagined Earth as a hub around

which these planets revolved.

In 1543, the Polish astronomer Nicolas Copernicus published his revolutionary idea that the Sun did not

circle Earth, but, instead, Earth and its lone moon circle the Sun, along with the rest of the planets.

By the 17th century, the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei discovered Jupiter's four largest moons.

Meanwhile, Dutchman Christiaan Huygens identified Saturn's rings and discovered Titan, its largest

moon. Italian astronomer Giovanni Cassini one-upped him, when he discovered four more.

In the 18th century, Englishman William Herschel discovered Uranus, although he originally called it the

Georgian star, after his King, George the III. Can you imagine a planet named George?

The British and French are still fighting over who deserves the credit for predicting the location of

Neptune. Some give the honor to John Couch Adams, while others say Urbain Le Verrier deserves it. But

there's no doubt that German astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle found it.

The discovery of Pluto finally added an American, Clyde Tombaugh, to this short but esteemed list of

planet-hunters.

So the folks in Streator, Illinois, told me that in New Mexico...there are still some Tombaughs there.

That's where Clyde moved after discovering Pluto. Clyde's no longer with us, but his 97-year-old widow

and both his son and daughter still live there. So I decided I had to check it out.

Wow. That's a lot of Tombaughs.

THE TOMBAUGHS (A small group speaking simultaneously): Hi.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: How many of you are there? Hello, everyone.

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH (Clyde Tombaugh's Daughter): Annette Tombaugh. I'm Clyde's daughter.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: What an honor, my gosh.

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH: This is my brother.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH (Clyde Tombaugh's Son): Neil, Al Tombaugh. I'm Clyde's son.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Hello.

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH: And this is my mother, Patsy Tombaugh; this is Clyde's wife.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: It is an honor, hello.

PATSY TOMBAUGH (Clyde Tombaugh's Widow): Yes, I've been looking forward to this.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: That could be...I don't know what that means. So tell me about Clyde, as a

person.

PATSY TOMBAUGH: He was the oldest of six children, so he was born to help on the farm. But he did

not want to be a farmer.

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH: He had not had the opportunity to go to college.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So, what you're saying is that he discovered Pluto without ever having yet gone

to college?

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH: No, he was straight off the farm.

PATSY TOMBAUGH: Lowell Observatory wanted somebody they didn't have to pay very much to do this

job. What do you think they pay you for finding a planet?

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH: After discovering Pluto, he got a college scholarship which he would not have

otherwise had. And, of course, he was supposed to be the big hero, but he didn't feel like the big hero.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Dad was a little embarrassed about the fame; he didn't like the limelight.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: He was humble?

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Absolutely.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So what was he just like as a dad? Was he, like, a weird dad, or did you think all

dads were like that?

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH: No, I knew he was very different. One of the things...we did have his grinding

barrel to make telescopes in the kitchen.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: This is the barrel that grinds glass into the shape of a mirror.

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH: Right; in the kitchen. How mother put up with that I don't know. We had

grinding material in our food, and Mother's trying to cook around this situation. Well, finally she made

Daddy move out of the kitchen, and he got a shop.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: That, that's good.

You mean to tell me you have some of Clyde's original telescopes here?

Wow, these were his original telescopes.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Original telescopes, built by my Dad.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Very handmade.

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH: And this is my mother, Patsy Tombaugh; this is Clyde's wife.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: It is an honor, hello.

PATSY TOMBAUGH (Clyde Tombaugh's Widow): Yes, I've been looking forward to this.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: That could be...I don't know what that means. So tell me about Clyde, as a

person.

PATSY TOMBAUGH: He was the oldest of six children, so he was born to help on the farm. But he did

not want to be a farmer.

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH: He had not had the opportunity to go to college.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So, what you're saying is that he discovered Pluto without ever having yet gone

to college?

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH: No, he was straight off the farm.

PATSY TOMBAUGH: Lowell Observatory wanted somebody they didn't have to pay very much to do this

job. What do you think they pay you for finding a planet?

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH: After discovering Pluto, he got a college scholarship which he would not have

otherwise had. And, of course, he was supposed to be the big hero, but he didn't feel like the big hero.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Dad was a little embarrassed about the fame; he didn't like the limelight.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: He was humble?

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Absolutely.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So what was he just like as a dad? Was he, like, a weird dad, or did you think all

dads were like that?

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH: No, I knew he was very different. One of the things...we did have his grinding

barrel to make telescopes in the kitchen.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: This is the barrel that grinds glass into the shape of a mirror.

ANNETTE TOMBAUGH: Right; in the kitchen. How mother put up with that I don't know. We had

grinding material in our food, and Mother's trying to cook around this situation. Well, finally she made

Daddy move out of the kitchen, and he got a shop.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: That, that's good.

You mean to tell me you have some of Clyde's original telescopes here?

Wow, these were his original telescopes.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Original telescopes, built by my Dad.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Very handmade.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

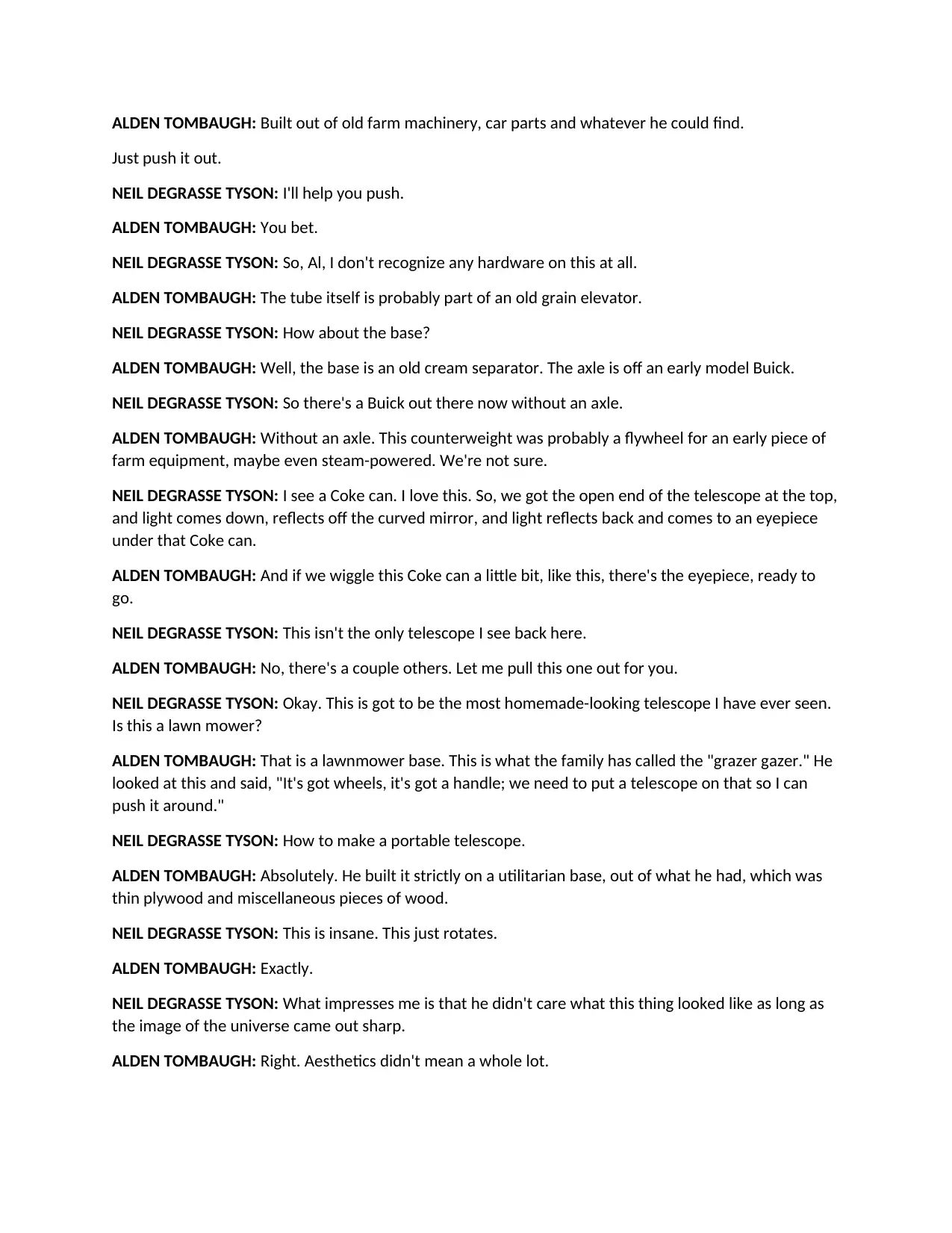

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Built out of old farm machinery, car parts and whatever he could find.

Just push it out.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: I'll help you push.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: You bet.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So, Al, I don't recognize any hardware on this at all.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: The tube itself is probably part of an old grain elevator.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: How about the base?

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Well, the base is an old cream separator. The axle is off an early model Buick.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So there's a Buick out there now without an axle.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Without an axle. This counterweight was probably a flywheel for an early piece of

farm equipment, maybe even steam-powered. We're not sure.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: I see a Coke can. I love this. So, we got the open end of the telescope at the top,

and light comes down, reflects off the curved mirror, and light reflects back and comes to an eyepiece

under that Coke can.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: And if we wiggle this Coke can a little bit, like this, there's the eyepiece, ready to

go.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: This isn't the only telescope I see back here.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: No, there's a couple others. Let me pull this one out for you.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Okay. This is got to be the most homemade-looking telescope I have ever seen.

Is this a lawn mower?

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: That is a lawnmower base. This is what the family has called the "grazer gazer." He

looked at this and said, "It's got wheels, it's got a handle; we need to put a telescope on that so I can

push it around."

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: How to make a portable telescope.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Absolutely. He built it strictly on a utilitarian base, out of what he had, which was

thin plywood and miscellaneous pieces of wood.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: This is insane. This just rotates.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Exactly.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: What impresses me is that he didn't care what this thing looked like as long as

the image of the universe came out sharp.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Right. Aesthetics didn't mean a whole lot.

Just push it out.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: I'll help you push.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: You bet.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So, Al, I don't recognize any hardware on this at all.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: The tube itself is probably part of an old grain elevator.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: How about the base?

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Well, the base is an old cream separator. The axle is off an early model Buick.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: So there's a Buick out there now without an axle.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Without an axle. This counterweight was probably a flywheel for an early piece of

farm equipment, maybe even steam-powered. We're not sure.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: I see a Coke can. I love this. So, we got the open end of the telescope at the top,

and light comes down, reflects off the curved mirror, and light reflects back and comes to an eyepiece

under that Coke can.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: And if we wiggle this Coke can a little bit, like this, there's the eyepiece, ready to

go.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: This isn't the only telescope I see back here.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: No, there's a couple others. Let me pull this one out for you.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Okay. This is got to be the most homemade-looking telescope I have ever seen.

Is this a lawn mower?

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: That is a lawnmower base. This is what the family has called the "grazer gazer." He

looked at this and said, "It's got wheels, it's got a handle; we need to put a telescope on that so I can

push it around."

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: How to make a portable telescope.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Absolutely. He built it strictly on a utilitarian base, out of what he had, which was

thin plywood and miscellaneous pieces of wood.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: This is insane. This just rotates.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Exactly.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: What impresses me is that he didn't care what this thing looked like as long as

the image of the universe came out sharp.

ALDEN TOMBAUGH: Right. Aesthetics didn't mean a whole lot.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: On my way out of town, I stopped at a local church where there's a tribute to

Clyde Tombaugh, a stained glass window that celebrates his life.

How many scientists have stained glass windows of them? It's more than just a celebration of his

discovery, it's a celebration of his life, overcoming obstacles that would keep most people down. To me

that's the message here.

After discovering Pluto, Clyde taught astronomy, and he searched for another planet in the far reaches

of the solar system. But as hard as he and other astronomers looked—and they looked hard—nobody

found anything. Most abandoned the search, assuming there was nothing left to find. But a few simply

couldn't accept the prevailing view that the solar system ended with Pluto.

I headed out to California to share a burger with two colleagues who were convinced there was

something else out there.

MIKE BROWN (California Institute of Technology): Foods a-comin'.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Back in the 1980s, David started a search that would put Pluto in a new

perspective.

So you start looking in the outer solar system? That's kind of crazy, because everyone knew the solar

system ended at Pluto.

DAVID JEWITT (University of California, Los Angeles): Uh, it's a little crazy. But, you know, the flipside is,

it didn't seem reasonable; it seemed peculiar that the outer solar system would be this really, really

empty place, compared to the inner solar system, which we already knew was full of planets and comets

and asteroids and all sorts of stuff.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Well it's got to end somewhere, why not Pluto?

DAVID JEWITT: Yeah. I mean maybe, but maybe not.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Despite what felt like impossible odds, David teamed up with Jane Luu—then a

graduate student—and they started a search that would take a lot longer then either one of them

expected.

JANE LUU (Researcher): Why did it take so long? Um, it was a matter of technology catching up with the

problem.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: While it's easy to see distant stars, because they radiate their own light, other

celestial bodies are much harder to see. That's because light has to travel all the way from our Sun to

the object, reflect off its surface, and then make the long journey back to Earth. By that time it's barely

visible.

David and Jane hoped that advances in digital detectors now standard in today's cameras would help

them see a whole lot more, that is, if there was anything out there to discover.

In 1992, after searching for five years, they finally found something.

DAVID JEWITT: Here is the set of discovery images for the first object. Obviously, it's the thing with the

circle around it. It didn't have a circle around it when we discovered it, but it does now. So you can see

Clyde Tombaugh, a stained glass window that celebrates his life.

How many scientists have stained glass windows of them? It's more than just a celebration of his

discovery, it's a celebration of his life, overcoming obstacles that would keep most people down. To me

that's the message here.

After discovering Pluto, Clyde taught astronomy, and he searched for another planet in the far reaches

of the solar system. But as hard as he and other astronomers looked—and they looked hard—nobody

found anything. Most abandoned the search, assuming there was nothing left to find. But a few simply

couldn't accept the prevailing view that the solar system ended with Pluto.

I headed out to California to share a burger with two colleagues who were convinced there was

something else out there.

MIKE BROWN (California Institute of Technology): Foods a-comin'.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Back in the 1980s, David started a search that would put Pluto in a new

perspective.

So you start looking in the outer solar system? That's kind of crazy, because everyone knew the solar

system ended at Pluto.

DAVID JEWITT (University of California, Los Angeles): Uh, it's a little crazy. But, you know, the flipside is,

it didn't seem reasonable; it seemed peculiar that the outer solar system would be this really, really

empty place, compared to the inner solar system, which we already knew was full of planets and comets

and asteroids and all sorts of stuff.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Well it's got to end somewhere, why not Pluto?

DAVID JEWITT: Yeah. I mean maybe, but maybe not.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: Despite what felt like impossible odds, David teamed up with Jane Luu—then a

graduate student—and they started a search that would take a lot longer then either one of them

expected.

JANE LUU (Researcher): Why did it take so long? Um, it was a matter of technology catching up with the

problem.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON: While it's easy to see distant stars, because they radiate their own light, other

celestial bodies are much harder to see. That's because light has to travel all the way from our Sun to

the object, reflect off its surface, and then make the long journey back to Earth. By that time it's barely

visible.

David and Jane hoped that advances in digital detectors now standard in today's cameras would help

them see a whole lot more, that is, if there was anything out there to discover.

In 1992, after searching for five years, they finally found something.

DAVID JEWITT: Here is the set of discovery images for the first object. Obviously, it's the thing with the

circle around it. It didn't have a circle around it when we discovered it, but it does now. So you can see

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 19

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.