Patient Falls, Pressure Ulcers, and Nurse Staffing Study

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/16

|24

|11914

|298

Report

AI Summary

This report, "Are Patient Falls and Pressure Ulcers Sensitive to Nurse Staffing?" published in the Western Journal of Nursing Research, evaluates the existing research linking nurse staffing levels to patient outcomes, specifically focusing on patient falls and pressure ulcers. The study examines eleven studies that employed multivariate analysis to discern the effect of nurse staffing on patient falls and pressure ulcers in hospitals. The article contrasts these studies based on their data sources, measures, data analysis techniques, risk adjustment methods, and reported results. The findings indicate that the evidence of an effect of nursing hours or skill mix on patient falls and pressure ulcers is equivocal due to differences in research methods. The report identifies two study types based on staffing measurement levels and suggests improvements in measurement and methods. The study also provides background on theoretical frameworks, adverse events, and risk adjustment in nursing outcomes research, offering a comprehensive overview of the complexities and challenges within this field. The research aims to guide practice and further scientific investigation into the relationship between nursing resources and patient safety.

654

Are Patient Falls and

Pressure Ulcers Sensitive

to Nurse Staffing?

Eileen T. Lake

Robyn B. Cheung

University of Pennsylvania

Research has demonstrated an association between more nurses and more

qualified nursing staff in hospitals and better patient outcomes. Patient falls

and pressure ulcers have been advanced as nursing-sensitive outcomes. This

article evaluates the state of the science linking nurse staffing to falls and

pressure ulcers. Studies that employed multivariate analysis to discern the

effect of nurse staffing on patient falls and pressure ulcers in hospitals were

evaluated. Eleven studies that met inclusion criteria were contrasted on their

data sources and measures, data analysis, risk adjustment, and results. The

evidence of an effect of nursing hours or skill mix on patient falls and pres-

sure ulcers is equivocal. Substantial differences in research methods across

studies may account for the mixed findings. Two study types were identified

based on the level at which nurse staffing was measured, hospital or nurs-

ing unit, which exhibited systematic differences in measures and methods.

Improvements in measurement and methods are suggested.

Keywords: nurse staffing; pressure ulcers; patient falls; multilevel research

methods

The quantity and quality of nursing care are expected to influence the

occurrence of patient falls and pressure ulcers. Some of these events are

preventable given sufficient nursing resources to assess risk and implement

Western Journal of

Nursing Research

Volume 28 Number 6

October 2006 654-677

© 2006 Sage Publications

10.1177/0193945906290323

http://wjn.sagepub.com

hosted at

http://online.sagepub.com

Authors’ Note: This article was funded in part by grants from the University of Pennsylvania

Research Foundation, the Xi Chapter, Sigma Theta Tau International, and the National Institute

of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health (Grant NR009068) to Dr. Lake and by an

institutional postdoctoral fellowship (National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes

of Health, Grant T32-NR07104) to Dr. Cheung. Dr. Cheung compiled and summarized the

empirical literature. Dr. Lake prepared the critical review of the empirical literature, developed

the tables, and developed the contributions to the science on staffing, falls, and pressure ulcers.

We appreciate the thoughtful review and helpful comments of the anonymous reviewers.

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Are Patient Falls and

Pressure Ulcers Sensitive

to Nurse Staffing?

Eileen T. Lake

Robyn B. Cheung

University of Pennsylvania

Research has demonstrated an association between more nurses and more

qualified nursing staff in hospitals and better patient outcomes. Patient falls

and pressure ulcers have been advanced as nursing-sensitive outcomes. This

article evaluates the state of the science linking nurse staffing to falls and

pressure ulcers. Studies that employed multivariate analysis to discern the

effect of nurse staffing on patient falls and pressure ulcers in hospitals were

evaluated. Eleven studies that met inclusion criteria were contrasted on their

data sources and measures, data analysis, risk adjustment, and results. The

evidence of an effect of nursing hours or skill mix on patient falls and pres-

sure ulcers is equivocal. Substantial differences in research methods across

studies may account for the mixed findings. Two study types were identified

based on the level at which nurse staffing was measured, hospital or nurs-

ing unit, which exhibited systematic differences in measures and methods.

Improvements in measurement and methods are suggested.

Keywords: nurse staffing; pressure ulcers; patient falls; multilevel research

methods

The quantity and quality of nursing care are expected to influence the

occurrence of patient falls and pressure ulcers. Some of these events are

preventable given sufficient nursing resources to assess risk and implement

Western Journal of

Nursing Research

Volume 28 Number 6

October 2006 654-677

© 2006 Sage Publications

10.1177/0193945906290323

http://wjn.sagepub.com

hosted at

http://online.sagepub.com

Authors’ Note: This article was funded in part by grants from the University of Pennsylvania

Research Foundation, the Xi Chapter, Sigma Theta Tau International, and the National Institute

of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health (Grant NR009068) to Dr. Lake and by an

institutional postdoctoral fellowship (National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes

of Health, Grant T32-NR07104) to Dr. Cheung. Dr. Cheung compiled and summarized the

empirical literature. Dr. Lake prepared the critical review of the empirical literature, developed

the tables, and developed the contributions to the science on staffing, falls, and pressure ulcers.

We appreciate the thoughtful review and helpful comments of the anonymous reviewers.

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Lake, Cheung / Nurse Staffing and Adverse Events 655

prevention strategies. Since 1996, the American Nurses Association (1999)

has considered falls and pressure ulcers to be “nursing-sensitive quality indi-

cators.” The National Quality Forum (2004) recently endorsed both falls and

pressure ulcers as core measures of nursing care performance in hospitals.

The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) landmark volume (Wunderlich, Sloan, &

Davis, 1996) revealed the dearth of empirical evidence on the relationships

between nurse staffing and quality of care. The theoretical basis for a link

among staffing, falls, and pressure ulcers, coupled with the IOM’s research

recommendations prompted scientific investigation of this link. A decade of

research can now be assessed to determine whether there is clear evidence

to guide practice and research. More broadly, the state of the science on this

question can be considered an exemplar of theoretical issues and method-

ological challenges in the field of nursing outcomes research.

The purposes of this article are to present and evaluate the state of the

science linking nurse staffing to patient falls and pressure ulcers and to

identify research methods to advance the science. To prepare the reader for

an evaluation of this science, the Background section provides an overview

of theoretical frameworks in nursing outcomes research, an initial descrip-

tion of the adverse events and measurement issues, and an overview of risk

adjustment in outcomes research.

Background

The Theoretical Link

Several theoretical or conceptual frameworks for the relationships

between nursing organizational factors and outcomes have been proposed

(Aiken, Sochalski, & Lake, 1997; Irvine, Sidani, & Hall, 1998; Mark,

Sayler, & Smith, 1996; Mitchell, Ferketich, Jennings, & American Academy

of Nursing Expert Panel on Quality Health Care, 1998). Mark et al. (1996)

theorized that both the hospital organizational context (i.e., environment and

technology) and the nursing unit structure (e.g., nurse–physician collabora-

tion) influence outcomes. They considered nursing skill mix and education

mix as context variables but did not mention staffing ratios. Aiken etal.

(1997) proposed that organizational models,such as magnet hospitals or

dedicated AIDS units, achieve better patient and nurse outcomes via

enhanced nurse autonomy, nurses’ control over the work environment, and

nurses’ relations with physicians. A subsequent framework incorporated

nurse staffing ratios and skill mix as hospital organizational features that

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

prevention strategies. Since 1996, the American Nurses Association (1999)

has considered falls and pressure ulcers to be “nursing-sensitive quality indi-

cators.” The National Quality Forum (2004) recently endorsed both falls and

pressure ulcers as core measures of nursing care performance in hospitals.

The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) landmark volume (Wunderlich, Sloan, &

Davis, 1996) revealed the dearth of empirical evidence on the relationships

between nurse staffing and quality of care. The theoretical basis for a link

among staffing, falls, and pressure ulcers, coupled with the IOM’s research

recommendations prompted scientific investigation of this link. A decade of

research can now be assessed to determine whether there is clear evidence

to guide practice and research. More broadly, the state of the science on this

question can be considered an exemplar of theoretical issues and method-

ological challenges in the field of nursing outcomes research.

The purposes of this article are to present and evaluate the state of the

science linking nurse staffing to patient falls and pressure ulcers and to

identify research methods to advance the science. To prepare the reader for

an evaluation of this science, the Background section provides an overview

of theoretical frameworks in nursing outcomes research, an initial descrip-

tion of the adverse events and measurement issues, and an overview of risk

adjustment in outcomes research.

Background

The Theoretical Link

Several theoretical or conceptual frameworks for the relationships

between nursing organizational factors and outcomes have been proposed

(Aiken, Sochalski, & Lake, 1997; Irvine, Sidani, & Hall, 1998; Mark,

Sayler, & Smith, 1996; Mitchell, Ferketich, Jennings, & American Academy

of Nursing Expert Panel on Quality Health Care, 1998). Mark et al. (1996)

theorized that both the hospital organizational context (i.e., environment and

technology) and the nursing unit structure (e.g., nurse–physician collabora-

tion) influence outcomes. They considered nursing skill mix and education

mix as context variables but did not mention staffing ratios. Aiken etal.

(1997) proposed that organizational models,such as magnet hospitals or

dedicated AIDS units, achieve better patient and nurse outcomes via

enhanced nurse autonomy, nurses’ control over the work environment, and

nurses’ relations with physicians. A subsequent framework incorporated

nurse staffing ratios and skill mix as hospital organizational features that

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

affect outcomes (Aiken,Clarke, & Sloane, 2002). Mitchell et al. (1998)

developed the quality health outcomes model, positing reciprocal relations

among system characteristics, interventions, client characteristics, and out-

comes; they identified nursing skill mix as a system characteristic. Irvine

et al. (1998) developed a nursing role effectiveness model that specified

nursing staff mix and workload as structural variables in a causal chain influ-

encing outcomes. Collectively, these models describe a theoretical link

between nurse staffing and patient outcomes and provide the basis for empir-

ical investigations of nurse staffing, patient falls, and pressure ulcers.

The nursing role, encompassing both surveillance and care, makes nurses

uniquely suited to prevent falls and pressure ulcers. The patients at greatest

risk of these events and the best prevention protocols have been well docu-

mented (Ayello & Braden, 2001; Olson et al., 1996; Rutledge, Donaldson,

& Pravikoff, 2003). Several basic elements of prevention, such as systematic

falls risk assessment once a shift or more and repositioning every 2 hours

for pressure ulcer prevention,depend directly on staff availability. Thus,

patients in better staffed hospitals may be expected to experience fewer falls

or pressure ulcers. Some preventive efforts may be provided by staff that are

not registered nurses (RNs). The key staffing component may be hours of

nursing care by all licensed staff (i.e., RNs and licensed practical nurses,

LPNs) or by total nursing staff rather than RN hours.

Occurrence of Falls and Pressure Ulcers

Falls and pressure ulcers occur rarely. Their frequency can be calculated

as rates of incidence (number of new cases occurring over a given period;

e.g., per 1,000 patient days) or rates of prevalence (a count or proportion of

a population observed at one time point that has the condition of interest;

Frantz, 1997). Falls incidence among hospital inpatients has been reported

as ranging from 2.3 to 7.0 falls per 1,000 patient days (Hitcho et al., 2004).

A large observational study revealed that 7% of medical–surgical and inten-

sive care patients developed pressure ulcers (Stages I through necrotic)

after hospital admission (Whittington, Patrick, & Roberts, 2000).

Risk Adjustment in Outcomes Research

Differences across patients influence the likelihood of an adverse event

(Iezzoni, 2003). In outcomes research, if differences in patients across orga-

nizational settings (hospitals or nursing units) are not controlled for, spuri-

ous relationships might be identified. Better staffed units may appear to

656 Western Journal of Nursing Research

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

developed the quality health outcomes model, positing reciprocal relations

among system characteristics, interventions, client characteristics, and out-

comes; they identified nursing skill mix as a system characteristic. Irvine

et al. (1998) developed a nursing role effectiveness model that specified

nursing staff mix and workload as structural variables in a causal chain influ-

encing outcomes. Collectively, these models describe a theoretical link

between nurse staffing and patient outcomes and provide the basis for empir-

ical investigations of nurse staffing, patient falls, and pressure ulcers.

The nursing role, encompassing both surveillance and care, makes nurses

uniquely suited to prevent falls and pressure ulcers. The patients at greatest

risk of these events and the best prevention protocols have been well docu-

mented (Ayello & Braden, 2001; Olson et al., 1996; Rutledge, Donaldson,

& Pravikoff, 2003). Several basic elements of prevention, such as systematic

falls risk assessment once a shift or more and repositioning every 2 hours

for pressure ulcer prevention,depend directly on staff availability. Thus,

patients in better staffed hospitals may be expected to experience fewer falls

or pressure ulcers. Some preventive efforts may be provided by staff that are

not registered nurses (RNs). The key staffing component may be hours of

nursing care by all licensed staff (i.e., RNs and licensed practical nurses,

LPNs) or by total nursing staff rather than RN hours.

Occurrence of Falls and Pressure Ulcers

Falls and pressure ulcers occur rarely. Their frequency can be calculated

as rates of incidence (number of new cases occurring over a given period;

e.g., per 1,000 patient days) or rates of prevalence (a count or proportion of

a population observed at one time point that has the condition of interest;

Frantz, 1997). Falls incidence among hospital inpatients has been reported

as ranging from 2.3 to 7.0 falls per 1,000 patient days (Hitcho et al., 2004).

A large observational study revealed that 7% of medical–surgical and inten-

sive care patients developed pressure ulcers (Stages I through necrotic)

after hospital admission (Whittington, Patrick, & Roberts, 2000).

Risk Adjustment in Outcomes Research

Differences across patients influence the likelihood of an adverse event

(Iezzoni, 2003). In outcomes research, if differences in patients across orga-

nizational settings (hospitals or nursing units) are not controlled for, spuri-

ous relationships might be identified. Better staffed units may appear to

656 Western Journal of Nursing Research

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

have poorer outcomes, when, in fact, the better staffing is because of a

sicker, higher risk patient group. The matter of differential risk is important

because most of the variation in adverse outcomes derives from patient

characteristics not hospital characteristics such as resources available for

treatment (Silber, Rosenbaum, & Ross, 1995). “It is vastly better to be a

little healthier than to go to a well-equipped hospital with a superior staff”

(Silber et al., 1995, p. 11).

In a multivariate model, there are several ways to account for the

patient’s contribution to the likelihood of the adverse event. The best way

is to include a measure of the patient’s risk for the specific outcome. Several

risk assessment scales for these adverse events are commonly used in acute

care: Morse (1996) and Schmid (1990) for falls risk and Braden (Braden &

Maklebust, 2005) and Norton (1996) for pressure ulcers. The patient’s risk

status (at risk or not) and risk score would be included in a patient-level

model predicting whether the patient did or did not have the adverse event.

Unfortunately, such risk data are not often available.

The second best way to account for differences across patients is to

include a measure of the patient’s severity of illness. A variety of severity

of illness measures have been developed based on medical record review or

discharge abstracts (Kane, 2006). These measures may focus on the physi-

ological severity of the principal diagnosis (the principal basis for the hos-

pital stay) and/or the number and severity of comorbid conditions.

A third way to measure differences across patients is by their differential

nursing care needs, or nursing acuity. The expectation is that patients with

greater nursing care needs are more likely to be at risk for adverse events.

Patients are classified daily according to a variety of factors that may include

physical activity, hygiene, feeding, medications, vital signs, and treatment.

Researchers may use aggregate measures to adjust for patient mix. An

example is the Medicare case mix index (CMI), which reflects the average

resources needed to care for the diagnostic mix of elderly patients in a hos-

pital or nursing unit. Although the CMI may be a proxy for patient mix in

an institution, it may not be suitable or sufficient for case mix adjustment

of younger adults or children. Sometimes researchers account for case mix

differences across institutions by conducting separate analyses for different

clinical subgroups of patients identified by nursing unit types or diagnoses.

This method does not account for severity of illness differences within clin-

ical subgroups.

In summary, risk adjustment approaches cover a range from the most

preferable but least available data (patient-specific risk data) to the least

preferable but most available (aggregated case mix or clinical data). The

Lake, Cheung / Nurse Staffing and Adverse Events 657

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

sicker, higher risk patient group. The matter of differential risk is important

because most of the variation in adverse outcomes derives from patient

characteristics not hospital characteristics such as resources available for

treatment (Silber, Rosenbaum, & Ross, 1995). “It is vastly better to be a

little healthier than to go to a well-equipped hospital with a superior staff”

(Silber et al., 1995, p. 11).

In a multivariate model, there are several ways to account for the

patient’s contribution to the likelihood of the adverse event. The best way

is to include a measure of the patient’s risk for the specific outcome. Several

risk assessment scales for these adverse events are commonly used in acute

care: Morse (1996) and Schmid (1990) for falls risk and Braden (Braden &

Maklebust, 2005) and Norton (1996) for pressure ulcers. The patient’s risk

status (at risk or not) and risk score would be included in a patient-level

model predicting whether the patient did or did not have the adverse event.

Unfortunately, such risk data are not often available.

The second best way to account for differences across patients is to

include a measure of the patient’s severity of illness. A variety of severity

of illness measures have been developed based on medical record review or

discharge abstracts (Kane, 2006). These measures may focus on the physi-

ological severity of the principal diagnosis (the principal basis for the hos-

pital stay) and/or the number and severity of comorbid conditions.

A third way to measure differences across patients is by their differential

nursing care needs, or nursing acuity. The expectation is that patients with

greater nursing care needs are more likely to be at risk for adverse events.

Patients are classified daily according to a variety of factors that may include

physical activity, hygiene, feeding, medications, vital signs, and treatment.

Researchers may use aggregate measures to adjust for patient mix. An

example is the Medicare case mix index (CMI), which reflects the average

resources needed to care for the diagnostic mix of elderly patients in a hos-

pital or nursing unit. Although the CMI may be a proxy for patient mix in

an institution, it may not be suitable or sufficient for case mix adjustment

of younger adults or children. Sometimes researchers account for case mix

differences across institutions by conducting separate analyses for different

clinical subgroups of patients identified by nursing unit types or diagnoses.

This method does not account for severity of illness differences within clin-

ical subgroups.

In summary, risk adjustment approaches cover a range from the most

preferable but least available data (patient-specific risk data) to the least

preferable but most available (aggregated case mix or clinical data). The

Lake, Cheung / Nurse Staffing and Adverse Events 657

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

choice of risk adjustment approach is generally dictated by data availa-

bility. Researchers may use multiple approaches simultaneously to take

advantage of all available data.

Method

The study design was critical analysis of empirical studies of the rela-

tionships among nurse staffing, falls, and pressure ulcers in hospitals. To

identify articles, multiple databases (CINAHL, PubMed, OVID) and terms

(nurse staffing, work environment, falls, pressure ulcers, patient outcomes)

were searched from their earliest dates through October 2005. The most

efficient search was obtained via PubMed with the terms nurse staffing and

pressure ulcer, or nurse staffing and falls. This database and strategy

yielded 37 articles. The inclusion criteria were publication in a peer-

reviewed journal, research about an acute care setting,falls or pressure

ulcers as outcomes of interest, and multivariate analysis of staffing and one

or both outcomes. Eleven studies met the criteria.

The analysis began with a description of the research design and findings.

Then, studies were compared on the clinical composition of the patient sam-

ple, the adverse event rates, the data sources and measures of nurse staffing

and adverse events, the data analyses, and the risk adjustment approaches.

These features were assessed to determine if certain samples,measures,

methods, or events consistently yielded significant or null findings.

Findings

In one study, nurse staffing was measured at the nurse level (Krauss etal.,

2005). In this innovative and intensive, prospective, case-control study, 98

patients who fell were matched to 318 controls randomly selected from all

inpatients and matched on length of stay at the point the fall occurred. The

other studies could be differentiated by the organizational level for nurse

staffing: nursing unit or hospital. The organizational level was the key design

feature associated with systematic differences in adverse event measurement

and risk adjustment methods across studies. Studies were classified into two

groups by level (Table 1). In five studies, hospital-level staffing was linked to

hospital- or patient-level adverse events (Table 1, Panel A). These studies had

from 200 to 800 hospitals and from 100,000 to 6 million patients. In five stud-

ies, both staffing and adverse events were measured at the nursing unit level

658 Western Journal of Nursing Research

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

bility. Researchers may use multiple approaches simultaneously to take

advantage of all available data.

Method

The study design was critical analysis of empirical studies of the rela-

tionships among nurse staffing, falls, and pressure ulcers in hospitals. To

identify articles, multiple databases (CINAHL, PubMed, OVID) and terms

(nurse staffing, work environment, falls, pressure ulcers, patient outcomes)

were searched from their earliest dates through October 2005. The most

efficient search was obtained via PubMed with the terms nurse staffing and

pressure ulcer, or nurse staffing and falls. This database and strategy

yielded 37 articles. The inclusion criteria were publication in a peer-

reviewed journal, research about an acute care setting,falls or pressure

ulcers as outcomes of interest, and multivariate analysis of staffing and one

or both outcomes. Eleven studies met the criteria.

The analysis began with a description of the research design and findings.

Then, studies were compared on the clinical composition of the patient sam-

ple, the adverse event rates, the data sources and measures of nurse staffing

and adverse events, the data analyses, and the risk adjustment approaches.

These features were assessed to determine if certain samples,measures,

methods, or events consistently yielded significant or null findings.

Findings

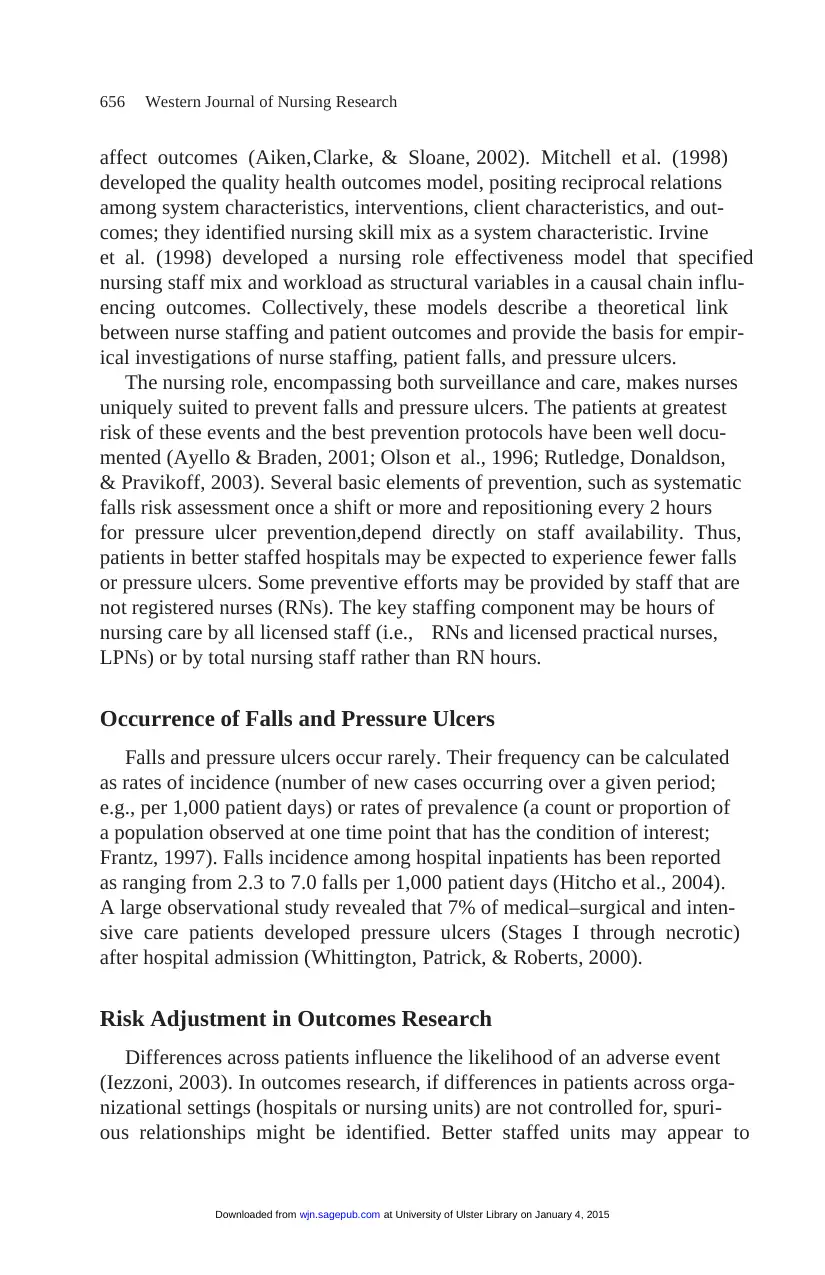

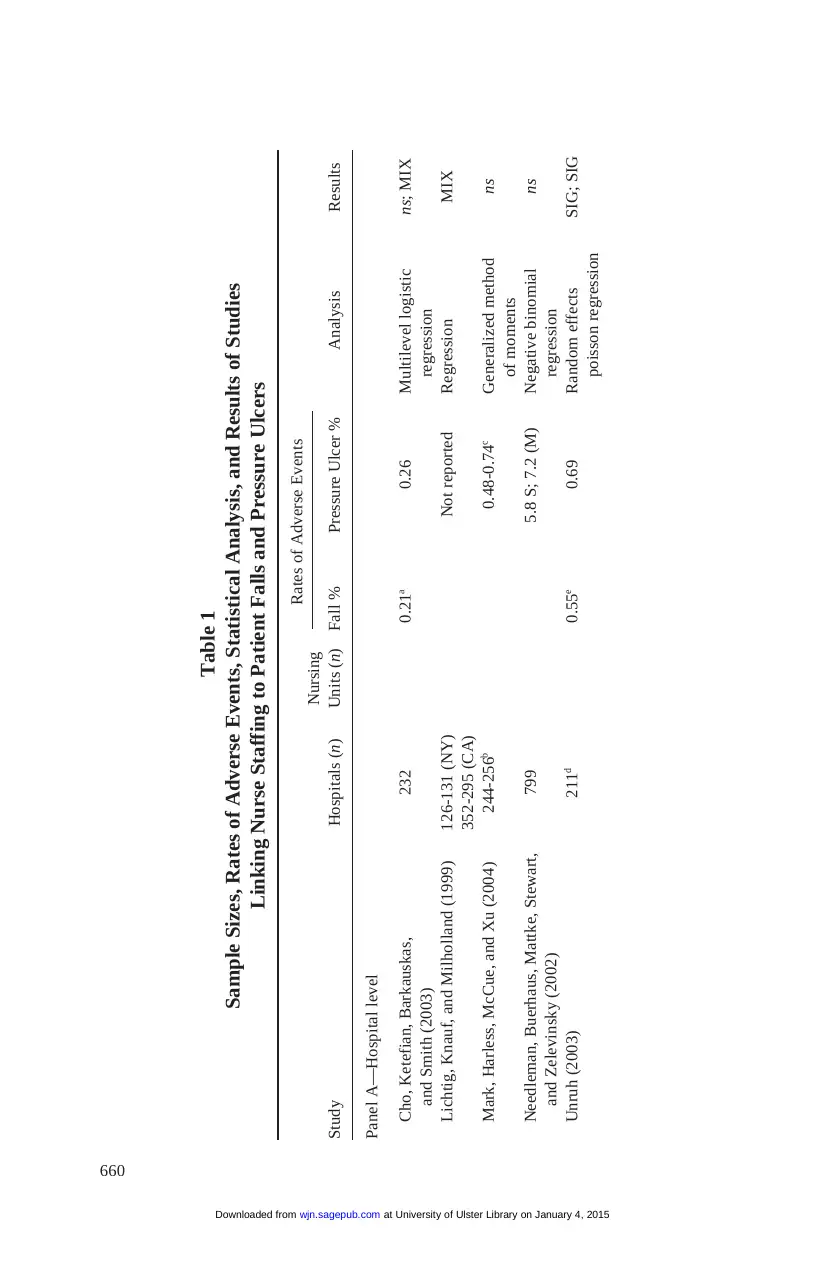

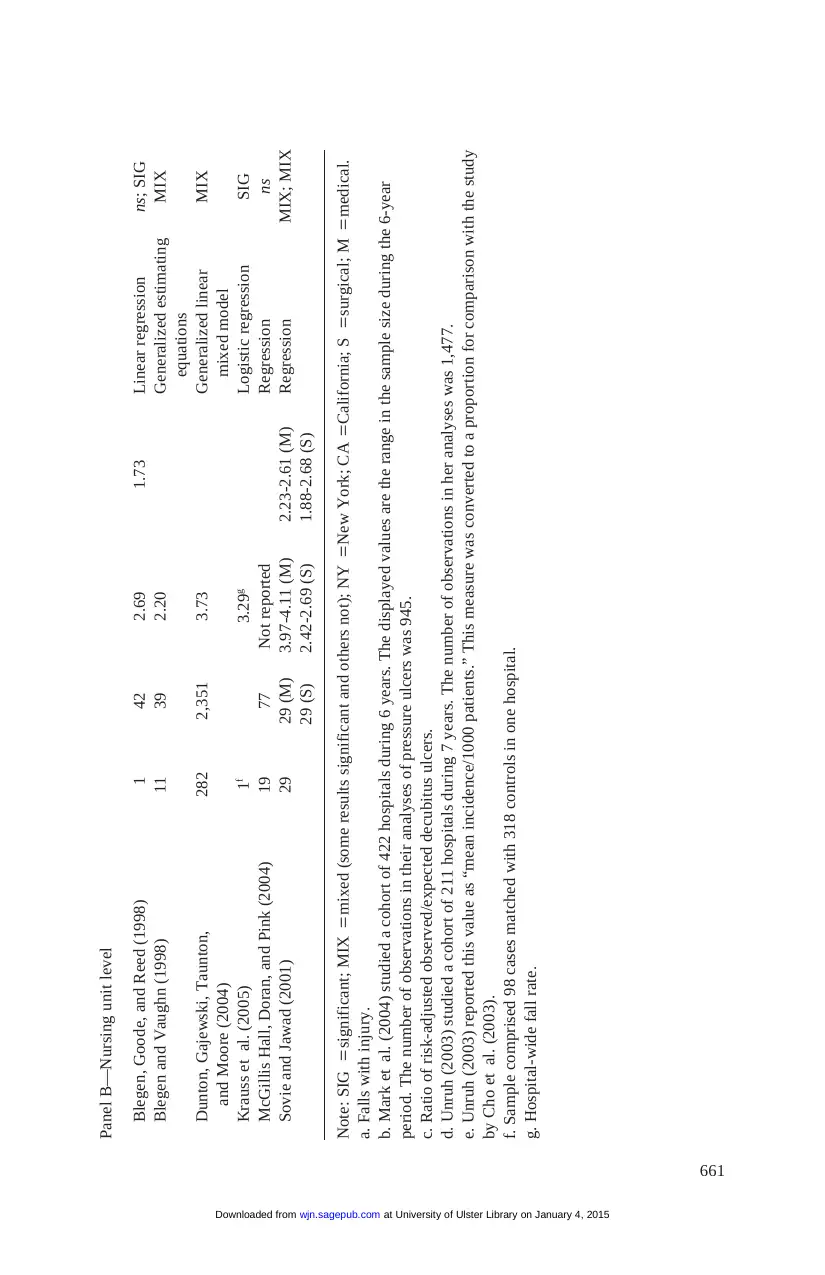

In one study, nurse staffing was measured at the nurse level (Krauss etal.,

2005). In this innovative and intensive, prospective, case-control study, 98

patients who fell were matched to 318 controls randomly selected from all

inpatients and matched on length of stay at the point the fall occurred. The

other studies could be differentiated by the organizational level for nurse

staffing: nursing unit or hospital. The organizational level was the key design

feature associated with systematic differences in adverse event measurement

and risk adjustment methods across studies. Studies were classified into two

groups by level (Table 1). In five studies, hospital-level staffing was linked to

hospital- or patient-level adverse events (Table 1, Panel A). These studies had

from 200 to 800 hospitals and from 100,000 to 6 million patients. In five stud-

ies, both staffing and adverse events were measured at the nursing unit level

658 Western Journal of Nursing Research

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

(Panel B). These studies had from 39 to 1,751 nursing units in 1 to 282 hos-

pitals. The Krauss et al. (2005) study is displayed in Panel B of Table 1.

Effect of Staffing on Falls and Pressure Ulcers

For each study, for the respective adverse events, Table 1 shows whether

the results across one or more analyses linking staffing measures to the

event were all significant, all not significant, or mixed (some significant and

others not). Falls were an outcome in eight studies. The results were sig-

nificant in two, mixed in three, and not significant in three. Pressure ulcers

were analyzed in seven studies. The results were significant in two, mixed

in three, and not significant in two. This initial picture suggests that the

evidence linking nurse staffing to these two events is inconclusive.

The inconclusive results may indicate a weak effect of staffing on these

events. An alternative explanation is that methodological limitations in

the literature prevent significant effects from being detected. An informed

judgment about the evidence requires a careful assessment of the methods.

Adverse Event Measurement and Frequency

Falls. For hospital-level studies, adverse events were identified by diag-

nosis or event codes in patient discharge abstracts in administrative data sets.

Cho, Ketefian, Barkauskas, and Smith (2003) used diagnosis codes indicat-

ing falls “with injury” among patients hospitalized for common surgeries in

California in 1997. Unruh (2003) used event codes indicating a low-level fall

or an accidental fall from a bed or chair for all medical and surgical patients

in Pennsylvania hospitals in 1991 to 1997. The fall rates from these studies

were trivial—less than 1% (Table 1). The rate detected by Unruh was more

than double the rate detected by Cho et al. This difference may reflect the

fact that most falls do not result in injury and that medical patients have

higher fall rates than do surgical patients (Hitcho et al., 2004). Rate com-

parisons across these different data sources may be inappropriate.

For nursing unit studies, falls were identified from incident reports. The

incidence ranged from 2 to 4 falls per 1,000 patient days. Blegen, Goode,

and Reed (1998) studied all 42 acute units in one hospital. Blegen and Vaughn

(1998) studied 39 medical/surgical, intensive care, obstetrics, and skilled

units in 11 hospitals. The fall rate was highest for skilled (4.0) and medical/

surgical units (2.7) and lowest for intensive care (1.4) and obstetrics (0.4).

Dunton, Gajewski, Taunton, and Moore (2004) studied data from 2,351

medical, surgical, step-down, and critical care units in 282 hospitals in

Lake, Cheung / Nurse Staffing and Adverse Events 659

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

pitals. The Krauss et al. (2005) study is displayed in Panel B of Table 1.

Effect of Staffing on Falls and Pressure Ulcers

For each study, for the respective adverse events, Table 1 shows whether

the results across one or more analyses linking staffing measures to the

event were all significant, all not significant, or mixed (some significant and

others not). Falls were an outcome in eight studies. The results were sig-

nificant in two, mixed in three, and not significant in three. Pressure ulcers

were analyzed in seven studies. The results were significant in two, mixed

in three, and not significant in two. This initial picture suggests that the

evidence linking nurse staffing to these two events is inconclusive.

The inconclusive results may indicate a weak effect of staffing on these

events. An alternative explanation is that methodological limitations in

the literature prevent significant effects from being detected. An informed

judgment about the evidence requires a careful assessment of the methods.

Adverse Event Measurement and Frequency

Falls. For hospital-level studies, adverse events were identified by diag-

nosis or event codes in patient discharge abstracts in administrative data sets.

Cho, Ketefian, Barkauskas, and Smith (2003) used diagnosis codes indicat-

ing falls “with injury” among patients hospitalized for common surgeries in

California in 1997. Unruh (2003) used event codes indicating a low-level fall

or an accidental fall from a bed or chair for all medical and surgical patients

in Pennsylvania hospitals in 1991 to 1997. The fall rates from these studies

were trivial—less than 1% (Table 1). The rate detected by Unruh was more

than double the rate detected by Cho et al. This difference may reflect the

fact that most falls do not result in injury and that medical patients have

higher fall rates than do surgical patients (Hitcho et al., 2004). Rate com-

parisons across these different data sources may be inappropriate.

For nursing unit studies, falls were identified from incident reports. The

incidence ranged from 2 to 4 falls per 1,000 patient days. Blegen, Goode,

and Reed (1998) studied all 42 acute units in one hospital. Blegen and Vaughn

(1998) studied 39 medical/surgical, intensive care, obstetrics, and skilled

units in 11 hospitals. The fall rate was highest for skilled (4.0) and medical/

surgical units (2.7) and lowest for intensive care (1.4) and obstetrics (0.4).

Dunton, Gajewski, Taunton, and Moore (2004) studied data from 2,351

medical, surgical, step-down, and critical care units in 282 hospitals in

Lake, Cheung / Nurse Staffing and Adverse Events 659

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

660

Table 1

Sample Sizes, Rates of Adverse Events, Statistical Analysis, and Results of Studies

Linking Nurse Staffing to Patient Falls and Pressure Ulcers

Nursing

Rates of Adverse Events

Study Hospitals (n) Units (n) Fall % Pressure Ulcer % Analysis Results

Panel A—Hospital level

Cho, Ketefian, Barkauskas, 232 0.21a 0.26 Multilevel logistic ns; MIX

and Smith (2003) regression

Lichtig, Knauf, and Milholland (1999) 126-131 (NY) Not reported Regression MIX

352-295 (CA)

Mark, Harless, McCue, and Xu (2004) 244-256b 0.48-0.74c Generalized method ns

of moments

Needleman, Buerhaus, Mattke, Stewart, 799 5.8 S; 7.2 (M) Negative binomial ns

and Zelevinsky (2002) regression

Unruh (2003) 211d 0.55e 0.69 Random effects SIG; SIG

poisson regression

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Table 1

Sample Sizes, Rates of Adverse Events, Statistical Analysis, and Results of Studies

Linking Nurse Staffing to Patient Falls and Pressure Ulcers

Nursing

Rates of Adverse Events

Study Hospitals (n) Units (n) Fall % Pressure Ulcer % Analysis Results

Panel A—Hospital level

Cho, Ketefian, Barkauskas, 232 0.21a 0.26 Multilevel logistic ns; MIX

and Smith (2003) regression

Lichtig, Knauf, and Milholland (1999) 126-131 (NY) Not reported Regression MIX

352-295 (CA)

Mark, Harless, McCue, and Xu (2004) 244-256b 0.48-0.74c Generalized method ns

of moments

Needleman, Buerhaus, Mattke, Stewart, 799 5.8 S; 7.2 (M) Negative binomial ns

and Zelevinsky (2002) regression

Unruh (2003) 211d 0.55e 0.69 Random effects SIG; SIG

poisson regression

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

661

Panel B—Nursing unit level

Blegen, Goode, and Reed (1998) 1 42 2.69 1.73 Linear regression ns; SIG

Blegen and Vaughn (1998) 11 39 2.20 Generalized estimating MIX

equations

Dunton, Gajewski, Taunton, 282 2,351 3.73 Generalized linear MIX

and Moore (2004) mixed model

Krauss et al. (2005) 1f 3.29g Logistic regression SIG

McGillis Hall, Doran, and Pink (2004) 19 77 Not reported Regression ns

Sovie and Jawad (2001) 29 29 (M) 3.97-4.11 (M) 2.23-2.61 (M) Regression MIX; MIX

29 (S) 2.42-2.69 (S) 1.88-2.68 (S)

Note: SIG =significant; MIX =mixed (some results significant and others not); NY =New York; CA =California; S =surgical; M =medical.

a. Falls with injury.

b. Mark et al. (2004) studied a cohort of 422 hospitals during 6 years. The displayed values are the range in the sample size during the 6-year

period. The number of observations in their analyses of pressure ulcers was 945.

c. Ratio of risk-adjusted observed/expected decubitus ulcers.

d. Unruh (2003) studied a cohort of 211 hospitals during 7 years. The number of observations in her analyses was 1,477.

e. Unruh (2003) reported this value as “mean incidence/1000 patients.” This measure was converted to a proportion for comparison with the study

by Cho et al. (2003).

f. Sample comprised 98 cases matched with 318 controls in one hospital.

g. Hospital-wide fall rate.

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Panel B—Nursing unit level

Blegen, Goode, and Reed (1998) 1 42 2.69 1.73 Linear regression ns; SIG

Blegen and Vaughn (1998) 11 39 2.20 Generalized estimating MIX

equations

Dunton, Gajewski, Taunton, 282 2,351 3.73 Generalized linear MIX

and Moore (2004) mixed model

Krauss et al. (2005) 1f 3.29g Logistic regression SIG

McGillis Hall, Doran, and Pink (2004) 19 77 Not reported Regression ns

Sovie and Jawad (2001) 29 29 (M) 3.97-4.11 (M) 2.23-2.61 (M) Regression MIX; MIX

29 (S) 2.42-2.69 (S) 1.88-2.68 (S)

Note: SIG =significant; MIX =mixed (some results significant and others not); NY =New York; CA =California; S =surgical; M =medical.

a. Falls with injury.

b. Mark et al. (2004) studied a cohort of 422 hospitals during 6 years. The displayed values are the range in the sample size during the 6-year

period. The number of observations in their analyses of pressure ulcers was 945.

c. Ratio of risk-adjusted observed/expected decubitus ulcers.

d. Unruh (2003) studied a cohort of 211 hospitals during 7 years. The number of observations in her analyses was 1,477.

e. Unruh (2003) reported this value as “mean incidence/1000 patients.” This measure was converted to a proportion for comparison with the study

by Cho et al. (2003).

f. Sample comprised 98 cases matched with 318 controls in one hospital.

g. Hospital-wide fall rate.

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

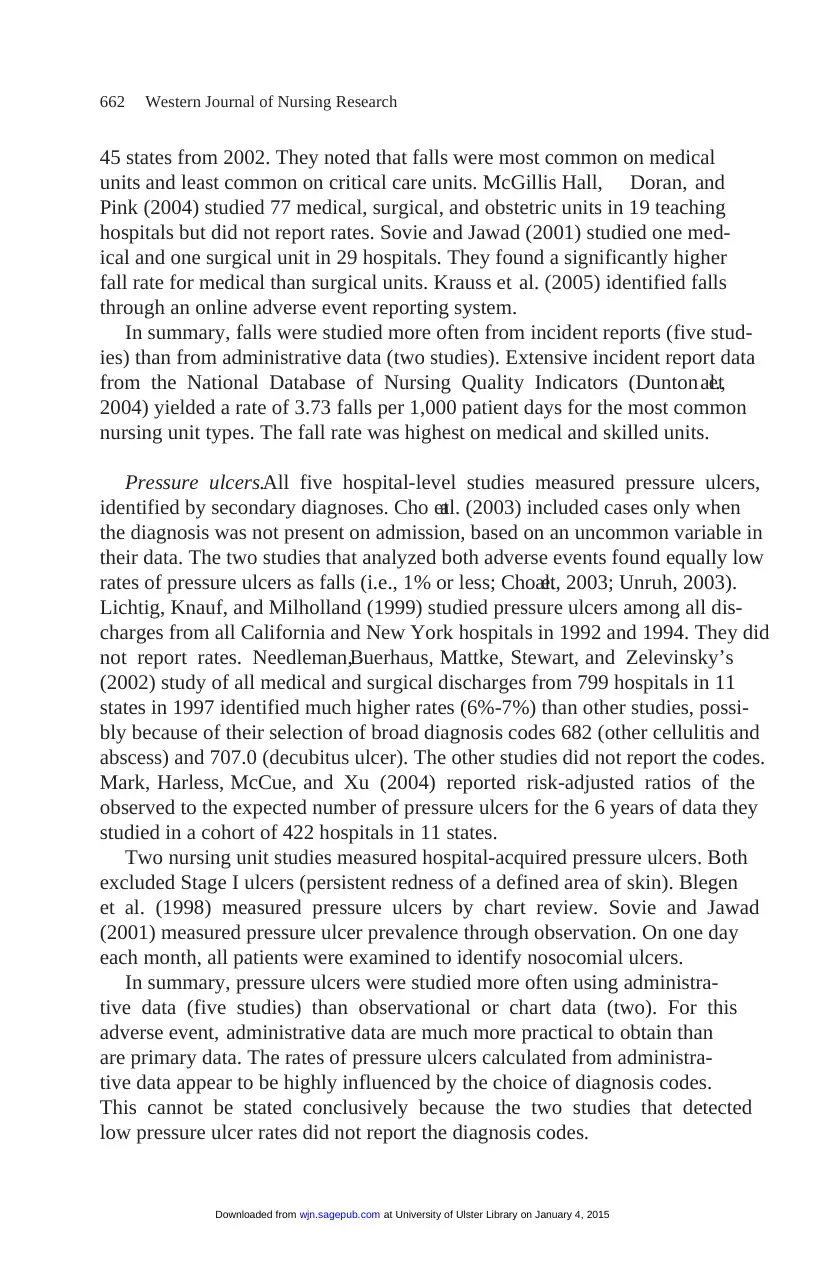

45 states from 2002. They noted that falls were most common on medical

units and least common on critical care units. McGillis Hall, Doran, and

Pink (2004) studied 77 medical, surgical, and obstetric units in 19 teaching

hospitals but did not report rates. Sovie and Jawad (2001) studied one med-

ical and one surgical unit in 29 hospitals. They found a significantly higher

fall rate for medical than surgical units. Krauss et al. (2005) identified falls

through an online adverse event reporting system.

In summary, falls were studied more often from incident reports (five stud-

ies) than from administrative data (two studies). Extensive incident report data

from the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (Dunton etal.,

2004) yielded a rate of 3.73 falls per 1,000 patient days for the most common

nursing unit types. The fall rate was highest on medical and skilled units.

Pressure ulcers.All five hospital-level studies measured pressure ulcers,

identified by secondary diagnoses. Cho etal. (2003) included cases only when

the diagnosis was not present on admission, based on an uncommon variable in

their data. The two studies that analyzed both adverse events found equally low

rates of pressure ulcers as falls (i.e., 1% or less; Cho etal., 2003; Unruh, 2003).

Lichtig, Knauf, and Milholland (1999) studied pressure ulcers among all dis-

charges from all California and New York hospitals in 1992 and 1994. They did

not report rates. Needleman,Buerhaus, Mattke, Stewart, and Zelevinsky’s

(2002) study of all medical and surgical discharges from 799 hospitals in 11

states in 1997 identified much higher rates (6%-7%) than other studies, possi-

bly because of their selection of broad diagnosis codes 682 (other cellulitis and

abscess) and 707.0 (decubitus ulcer). The other studies did not report the codes.

Mark, Harless, McCue, and Xu (2004) reported risk-adjusted ratios of the

observed to the expected number of pressure ulcers for the 6 years of data they

studied in a cohort of 422 hospitals in 11 states.

Two nursing unit studies measured hospital-acquired pressure ulcers. Both

excluded Stage I ulcers (persistent redness of a defined area of skin). Blegen

et al. (1998) measured pressure ulcers by chart review. Sovie and Jawad

(2001) measured pressure ulcer prevalence through observation. On one day

each month, all patients were examined to identify nosocomial ulcers.

In summary, pressure ulcers were studied more often using administra-

tive data (five studies) than observational or chart data (two). For this

adverse event, administrative data are much more practical to obtain than

are primary data. The rates of pressure ulcers calculated from administra-

tive data appear to be highly influenced by the choice of diagnosis codes.

This cannot be stated conclusively because the two studies that detected

low pressure ulcer rates did not report the diagnosis codes.

662 Western Journal of Nursing Research

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

units and least common on critical care units. McGillis Hall, Doran, and

Pink (2004) studied 77 medical, surgical, and obstetric units in 19 teaching

hospitals but did not report rates. Sovie and Jawad (2001) studied one med-

ical and one surgical unit in 29 hospitals. They found a significantly higher

fall rate for medical than surgical units. Krauss et al. (2005) identified falls

through an online adverse event reporting system.

In summary, falls were studied more often from incident reports (five stud-

ies) than from administrative data (two studies). Extensive incident report data

from the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (Dunton etal.,

2004) yielded a rate of 3.73 falls per 1,000 patient days for the most common

nursing unit types. The fall rate was highest on medical and skilled units.

Pressure ulcers.All five hospital-level studies measured pressure ulcers,

identified by secondary diagnoses. Cho etal. (2003) included cases only when

the diagnosis was not present on admission, based on an uncommon variable in

their data. The two studies that analyzed both adverse events found equally low

rates of pressure ulcers as falls (i.e., 1% or less; Cho etal., 2003; Unruh, 2003).

Lichtig, Knauf, and Milholland (1999) studied pressure ulcers among all dis-

charges from all California and New York hospitals in 1992 and 1994. They did

not report rates. Needleman,Buerhaus, Mattke, Stewart, and Zelevinsky’s

(2002) study of all medical and surgical discharges from 799 hospitals in 11

states in 1997 identified much higher rates (6%-7%) than other studies, possi-

bly because of their selection of broad diagnosis codes 682 (other cellulitis and

abscess) and 707.0 (decubitus ulcer). The other studies did not report the codes.

Mark, Harless, McCue, and Xu (2004) reported risk-adjusted ratios of the

observed to the expected number of pressure ulcers for the 6 years of data they

studied in a cohort of 422 hospitals in 11 states.

Two nursing unit studies measured hospital-acquired pressure ulcers. Both

excluded Stage I ulcers (persistent redness of a defined area of skin). Blegen

et al. (1998) measured pressure ulcers by chart review. Sovie and Jawad

(2001) measured pressure ulcer prevalence through observation. On one day

each month, all patients were examined to identify nosocomial ulcers.

In summary, pressure ulcers were studied more often using administra-

tive data (five studies) than observational or chart data (two). For this

adverse event, administrative data are much more practical to obtain than

are primary data. The rates of pressure ulcers calculated from administra-

tive data appear to be highly influenced by the choice of diagnosis codes.

This cannot be stated conclusively because the two studies that detected

low pressure ulcer rates did not report the diagnosis codes.

662 Western Journal of Nursing Research

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

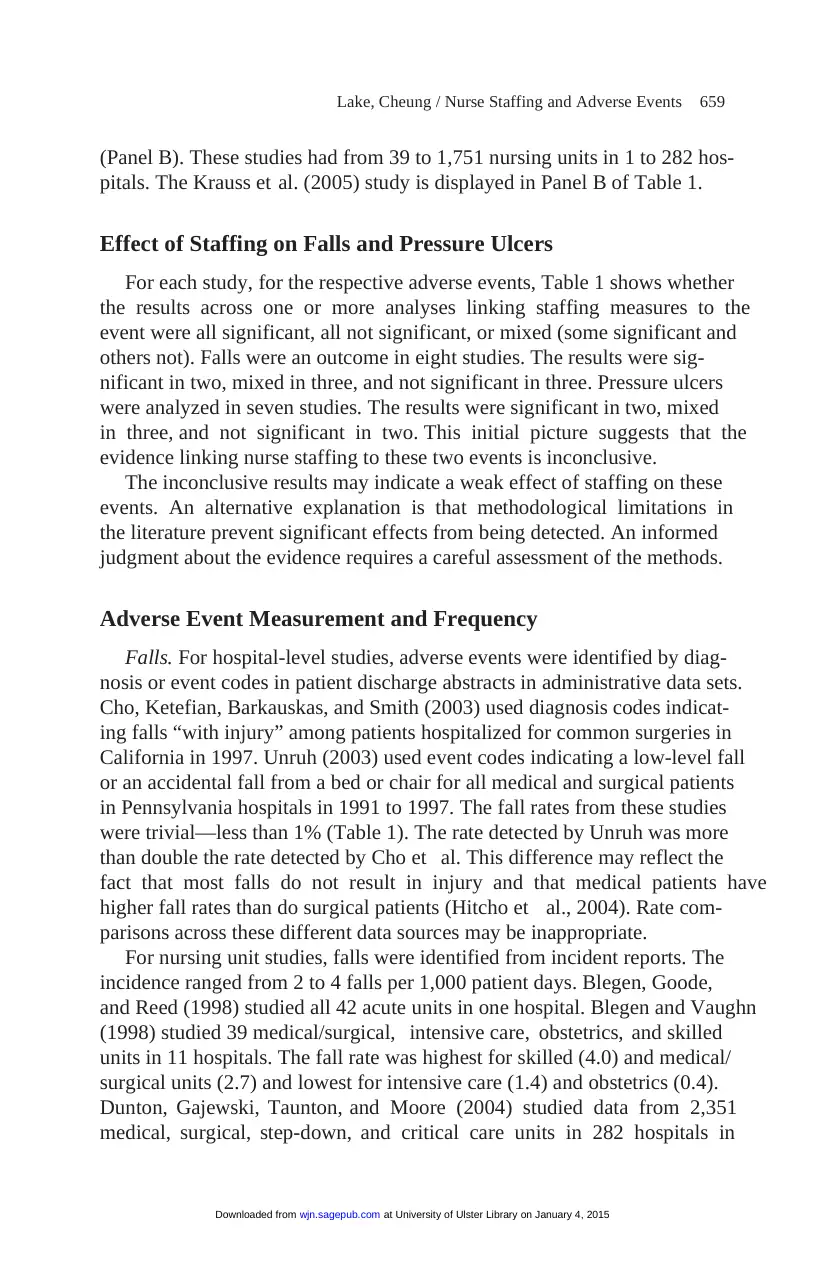

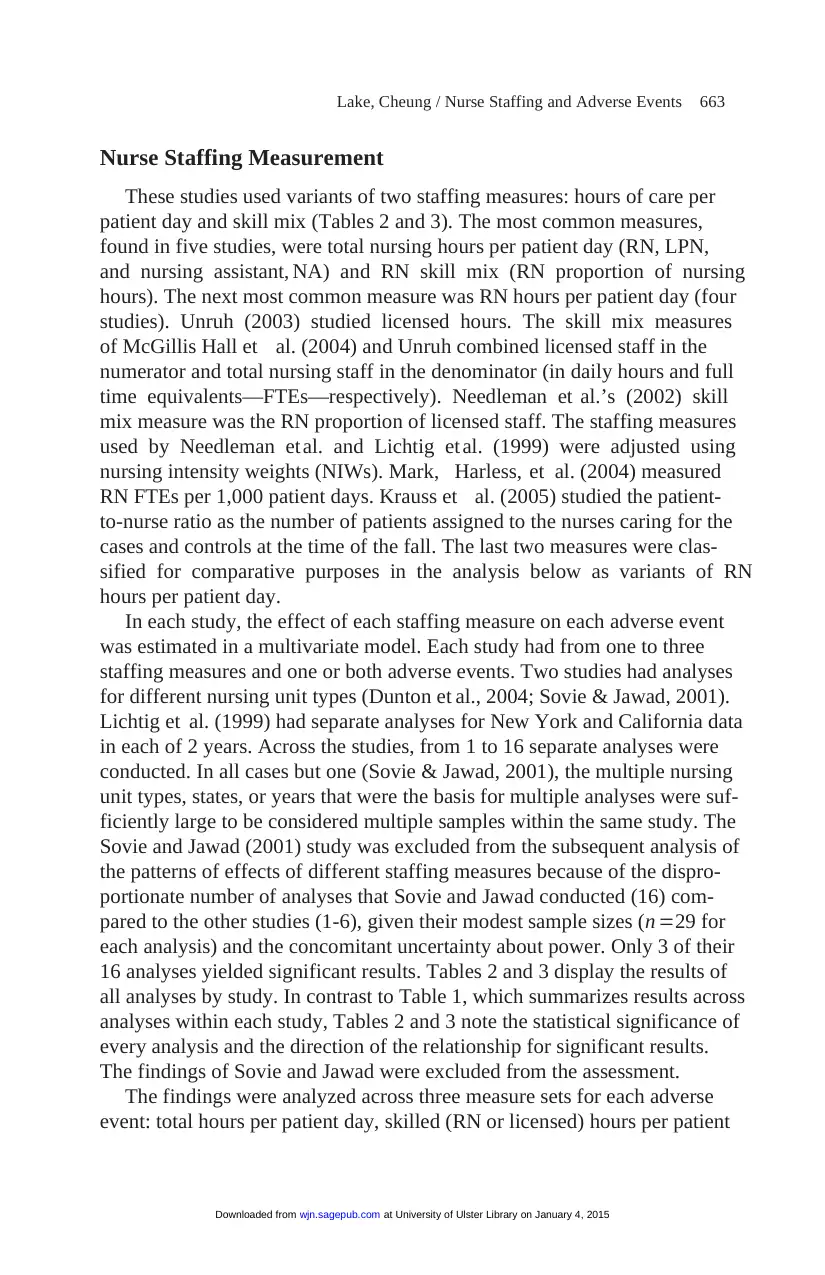

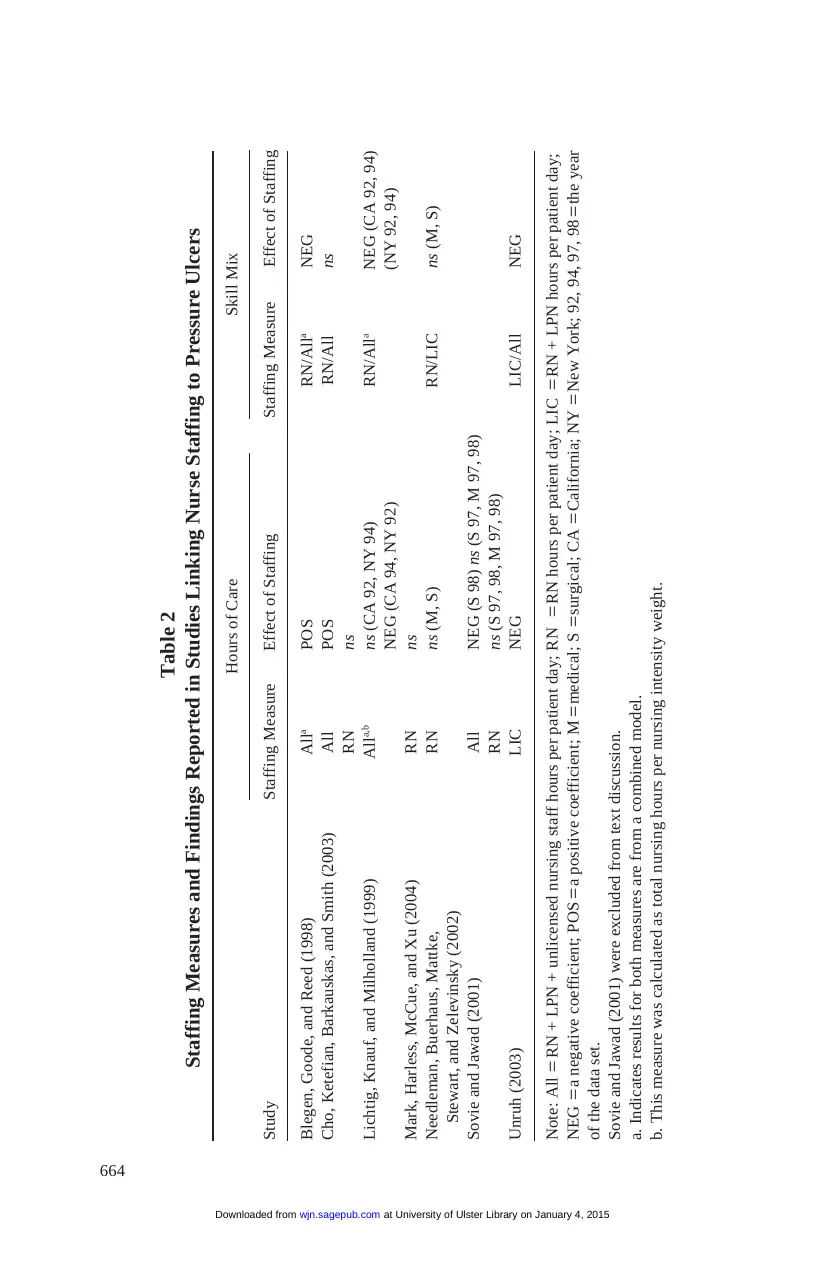

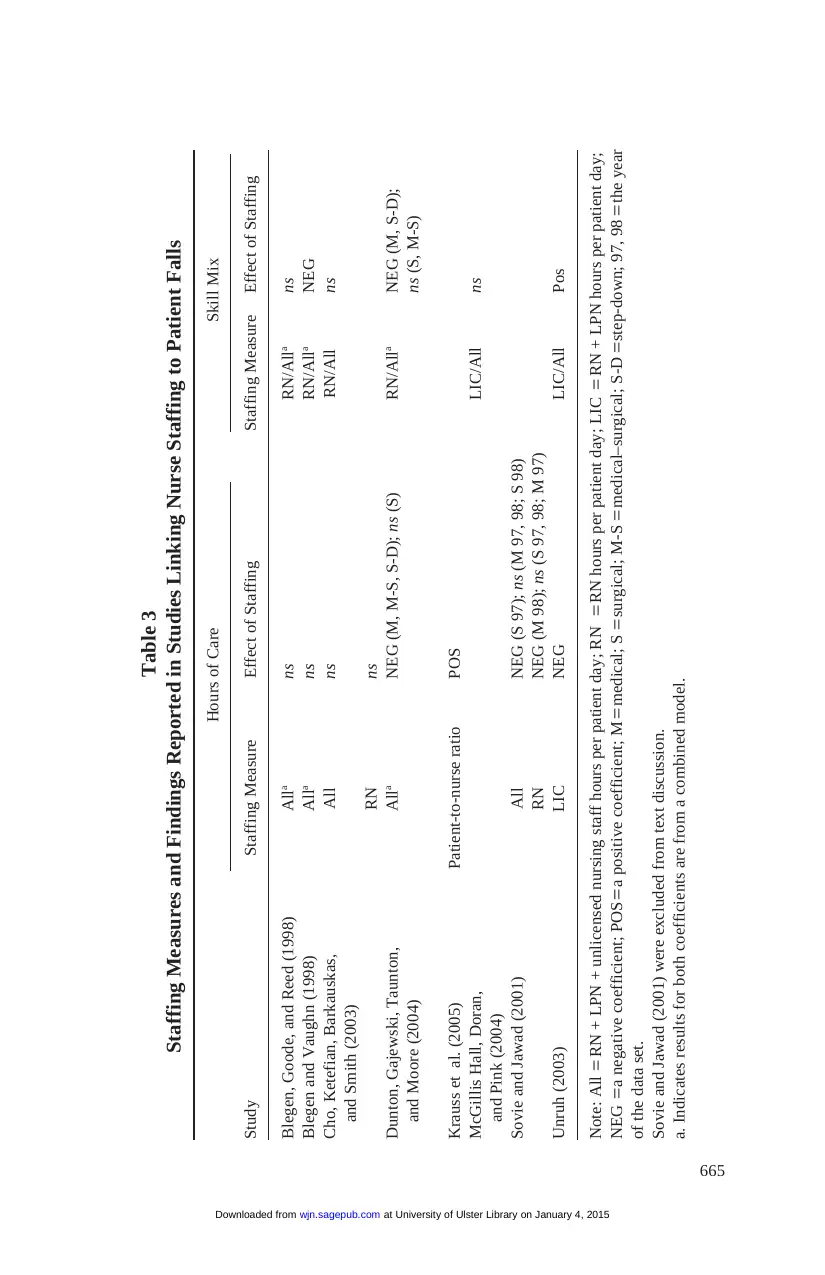

Nurse Staffing Measurement

These studies used variants of two staffing measures: hours of care per

patient day and skill mix (Tables 2 and 3). The most common measures,

found in five studies, were total nursing hours per patient day (RN, LPN,

and nursing assistant, NA) and RN skill mix (RN proportion of nursing

hours). The next most common measure was RN hours per patient day (four

studies). Unruh (2003) studied licensed hours. The skill mix measures

of McGillis Hall et al. (2004) and Unruh combined licensed staff in the

numerator and total nursing staff in the denominator (in daily hours and full

time equivalents—FTEs—respectively). Needleman et al.’s (2002) skill

mix measure was the RN proportion of licensed staff. The staffing measures

used by Needleman et al. and Lichtig et al. (1999) were adjusted using

nursing intensity weights (NIWs). Mark, Harless, et al. (2004) measured

RN FTEs per 1,000 patient days. Krauss et al. (2005) studied the patient-

to-nurse ratio as the number of patients assigned to the nurses caring for the

cases and controls at the time of the fall. The last two measures were clas-

sified for comparative purposes in the analysis below as variants of RN

hours per patient day.

In each study, the effect of each staffing measure on each adverse event

was estimated in a multivariate model. Each study had from one to three

staffing measures and one or both adverse events. Two studies had analyses

for different nursing unit types (Dunton et al., 2004; Sovie & Jawad, 2001).

Lichtig et al. (1999) had separate analyses for New York and California data

in each of 2 years. Across the studies, from 1 to 16 separate analyses were

conducted. In all cases but one (Sovie & Jawad, 2001), the multiple nursing

unit types, states, or years that were the basis for multiple analyses were suf-

ficiently large to be considered multiple samples within the same study. The

Sovie and Jawad (2001) study was excluded from the subsequent analysis of

the patterns of effects of different staffing measures because of the dispro-

portionate number of analyses that Sovie and Jawad conducted (16) com-

pared to the other studies (1-6), given their modest sample sizes (n =29 for

each analysis) and the concomitant uncertainty about power. Only 3 of their

16 analyses yielded significant results. Tables 2 and 3 display the results of

all analyses by study. In contrast to Table 1, which summarizes results across

analyses within each study, Tables 2 and 3 note the statistical significance of

every analysis and the direction of the relationship for significant results.

The findings of Sovie and Jawad were excluded from the assessment.

The findings were analyzed across three measure sets for each adverse

event: total hours per patient day, skilled (RN or licensed) hours per patient

Lake, Cheung / Nurse Staffing and Adverse Events 663

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

These studies used variants of two staffing measures: hours of care per

patient day and skill mix (Tables 2 and 3). The most common measures,

found in five studies, were total nursing hours per patient day (RN, LPN,

and nursing assistant, NA) and RN skill mix (RN proportion of nursing

hours). The next most common measure was RN hours per patient day (four

studies). Unruh (2003) studied licensed hours. The skill mix measures

of McGillis Hall et al. (2004) and Unruh combined licensed staff in the

numerator and total nursing staff in the denominator (in daily hours and full

time equivalents—FTEs—respectively). Needleman et al.’s (2002) skill

mix measure was the RN proportion of licensed staff. The staffing measures

used by Needleman et al. and Lichtig et al. (1999) were adjusted using

nursing intensity weights (NIWs). Mark, Harless, et al. (2004) measured

RN FTEs per 1,000 patient days. Krauss et al. (2005) studied the patient-

to-nurse ratio as the number of patients assigned to the nurses caring for the

cases and controls at the time of the fall. The last two measures were clas-

sified for comparative purposes in the analysis below as variants of RN

hours per patient day.

In each study, the effect of each staffing measure on each adverse event

was estimated in a multivariate model. Each study had from one to three

staffing measures and one or both adverse events. Two studies had analyses

for different nursing unit types (Dunton et al., 2004; Sovie & Jawad, 2001).

Lichtig et al. (1999) had separate analyses for New York and California data

in each of 2 years. Across the studies, from 1 to 16 separate analyses were

conducted. In all cases but one (Sovie & Jawad, 2001), the multiple nursing

unit types, states, or years that were the basis for multiple analyses were suf-

ficiently large to be considered multiple samples within the same study. The

Sovie and Jawad (2001) study was excluded from the subsequent analysis of

the patterns of effects of different staffing measures because of the dispro-

portionate number of analyses that Sovie and Jawad conducted (16) com-

pared to the other studies (1-6), given their modest sample sizes (n =29 for

each analysis) and the concomitant uncertainty about power. Only 3 of their

16 analyses yielded significant results. Tables 2 and 3 display the results of

all analyses by study. In contrast to Table 1, which summarizes results across

analyses within each study, Tables 2 and 3 note the statistical significance of

every analysis and the direction of the relationship for significant results.

The findings of Sovie and Jawad were excluded from the assessment.

The findings were analyzed across three measure sets for each adverse

event: total hours per patient day, skilled (RN or licensed) hours per patient

Lake, Cheung / Nurse Staffing and Adverse Events 663

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

664

Table 2

Staffing Measures and Findings Reported in Studies Linking Nurse Staffing to Pressure Ulcers

Hours of Care Skill Mix

Study Staffing Measure Effect of Staffing Staffing Measure Effect of Staffing

Blegen, Goode, and Reed (1998) Alla POS RN/Alla NEG

Cho, Ketefian, Barkauskas, and Smith (2003) All POS RN/All ns

RN ns

Lichtig, Knauf, and Milholland (1999) Alla,b ns (CA 92, NY 94) RN/Alla NEG (CA 92, 94)

NEG (CA 94, NY 92) (NY 92, 94)

Mark, Harless, McCue, and Xu (2004) RN ns

Needleman, Buerhaus, Mattke, RN ns (M, S) RN/LIC ns (M, S)

Stewart, and Zelevinsky (2002)

Sovie and Jawad (2001) All NEG (S 98) ns (S 97, M 97, 98)

RN ns (S 97, 98, M 97, 98)

Unruh (2003) LIC NEG LIC/All NEG

Note: All =RN + LPN + unlicensed nursing staff hours per patient day; RN =RN hours per patient day; LIC =RN + LPN hours per patient day;

NEG =a negative coefficient; POS =a positive coefficient; M =medical; S =surgical; CA =California; NY =New York; 92, 94, 97, 98 =the year

of the data set.

Sovie and Jawad (2001) were excluded from text discussion.

a. Indicates results for both measures are from a combined model.

b. This measure was calculated as total nursing hours per nursing intensity weight.

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Table 2

Staffing Measures and Findings Reported in Studies Linking Nurse Staffing to Pressure Ulcers

Hours of Care Skill Mix

Study Staffing Measure Effect of Staffing Staffing Measure Effect of Staffing

Blegen, Goode, and Reed (1998) Alla POS RN/Alla NEG

Cho, Ketefian, Barkauskas, and Smith (2003) All POS RN/All ns

RN ns

Lichtig, Knauf, and Milholland (1999) Alla,b ns (CA 92, NY 94) RN/Alla NEG (CA 92, 94)

NEG (CA 94, NY 92) (NY 92, 94)

Mark, Harless, McCue, and Xu (2004) RN ns

Needleman, Buerhaus, Mattke, RN ns (M, S) RN/LIC ns (M, S)

Stewart, and Zelevinsky (2002)

Sovie and Jawad (2001) All NEG (S 98) ns (S 97, M 97, 98)

RN ns (S 97, 98, M 97, 98)

Unruh (2003) LIC NEG LIC/All NEG

Note: All =RN + LPN + unlicensed nursing staff hours per patient day; RN =RN hours per patient day; LIC =RN + LPN hours per patient day;

NEG =a negative coefficient; POS =a positive coefficient; M =medical; S =surgical; CA =California; NY =New York; 92, 94, 97, 98 =the year

of the data set.

Sovie and Jawad (2001) were excluded from text discussion.

a. Indicates results for both measures are from a combined model.

b. This measure was calculated as total nursing hours per nursing intensity weight.

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

665

Table 3

Staffing Measures and Findings Reported in Studies Linking Nurse Staffing to Patient Falls

Hours of Care Skill Mix

Study Staffing Measure Effect of Staffing Staffing Measure Effect of Staffing

Blegen, Goode, and Reed (1998) Alla ns RN/Alla ns

Blegen and Vaughn (1998) Alla ns RN/Alla NEG

Cho, Ketefian, Barkauskas, All ns RN/All ns

and Smith (2003)

RN ns

Dunton, Gajewski, Taunton, Alla NEG (M, M-S, S-D); ns (S) RN/Alla NEG (M, S-D);

and Moore (2004) ns (S, M-S)

Krauss et al. (2005) Patient-to-nurse ratio POS

McGillis Hall, Doran, LIC/All ns

and Pink (2004)

Sovie and Jawad (2001) All NEG (S 97); ns (M 97, 98; S 98)

RN NEG (M 98); ns (S 97, 98; M 97)

Unruh (2003) LIC NEG LIC/All Pos

Note: All =RN + LPN + unlicensed nursing staff hours per patient day; RN =RN hours per patient day; LIC =RN + LPN hours per patient day;

NEG =a negative coefficient; POS =a positive coefficient; M =medical; S =surgical; M-S =medical–surgical; S-D =step-down; 97, 98 =the year

of the data set.

Sovie and Jawad (2001) were excluded from text discussion.

a. Indicates results for both coefficients are from a combined model.

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Table 3

Staffing Measures and Findings Reported in Studies Linking Nurse Staffing to Patient Falls

Hours of Care Skill Mix

Study Staffing Measure Effect of Staffing Staffing Measure Effect of Staffing

Blegen, Goode, and Reed (1998) Alla ns RN/Alla ns

Blegen and Vaughn (1998) Alla ns RN/Alla NEG

Cho, Ketefian, Barkauskas, All ns RN/All ns

and Smith (2003)

RN ns

Dunton, Gajewski, Taunton, Alla NEG (M, M-S, S-D); ns (S) RN/Alla NEG (M, S-D);

and Moore (2004) ns (S, M-S)

Krauss et al. (2005) Patient-to-nurse ratio POS

McGillis Hall, Doran, LIC/All ns

and Pink (2004)

Sovie and Jawad (2001) All NEG (S 97); ns (M 97, 98; S 98)

RN NEG (M 98); ns (S 97, 98; M 97)

Unruh (2003) LIC NEG LIC/All Pos

Note: All =RN + LPN + unlicensed nursing staff hours per patient day; RN =RN hours per patient day; LIC =RN + LPN hours per patient day;

NEG =a negative coefficient; POS =a positive coefficient; M =medical; S =surgical; M-S =medical–surgical; S-D =step-down; 97, 98 =the year

of the data set.

Sovie and Jawad (2001) were excluded from text discussion.

a. Indicates results for both coefficients are from a combined model.

at University of Ulster Library on January 4, 2015wjn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 24

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.