Pediatric Nurses' Perceptions of EOL Care Barriers in Southeast Iran

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/09

|9

|8403

|433

Report

AI Summary

This research paper, published in the American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine, investigates pediatric nurses' perceptions of barriers encountered when providing end-of-life (EOL) care to terminally ill children in Southeast Iran. The study utilized a modified version of the National Survey of Critical Care Nurses’ Regarding End-of-Life Care questionnaire to assess nurses' views on the intensity and frequency of various barriers. The findings revealed that family-related issues were among the most significant barriers perceived by nurses. The study highlights the absence of palliative care (PC) education and dedicated PC units in Iran as a contributing factor to these challenges. The authors suggest that developing EOL/PC education could improve nurses' knowledge and skills in managing the complexities of EOL care. The context of Iran, its healthcare system, and cultural perspectives on death are also discussed, providing a comprehensive understanding of the challenges faced by healthcare professionals in this setting.

Nursing Manuscript

Nursing Staff’s Perception of Barriers in

Providing End-of-Life Care to Terminally Ill

Pediatric Patients in Southeast Iran

Sedigheh Iranmanesh, PhD, MSc1, Marjan Banazadeh, MSc1,

and Mansoure Azizzadeh Forozy, MSc2

Abstract

Objective:To determine pediatric nurses’perceptions ofintensity,frequency occurrence,and magnitude score ofselected

barriers in providing pediatric end-of-life (EOL) care. Method: A translated modified version of National Survey o

Nurses’ s Regarding End-of-Life Care questionnaire was used to assess 151 nurses’ perceptions of intensity and

rence of barriers in caring for dying children. Results: The highest/lowest perceived barriers magnitude scores w

accepting poor child prognosis’’ (5.04) and ‘‘continuing to provide advanced treatment to dying child because o

to the hospital’’ (2.19). conclusion: More high perceived barriers by nurses were family-related issues. One of th

of such deficiencies was lack of palliative care (PC) education/PC units in Iran. Thus, developing EOL/PC educati

nurses’knowledge/skillto face EOL care challenges.

Keywords

nurses’perception,barriers,end-of-life care,terminally illchildren,Southeast Iran

Introduction

The idea that a child may die is simply unimaginable to most

people,yet children die daily.1 According to Morgan,2 when

a child dies, this cycle seems unnatural, causing loss of human

potential,and dreamsquickly shatter.2 Children represent

health and hope, and their death calls into question the under-

standing of life.3 Unfortunately, annually about 50 000 children

die in the United States.4 Of these, over half die during the first

year of life.5 A child’s chronic illness may progress to the point

of becoming a terminal illness that deemed to be incurable, ulti-

mately leading to death.1 Unlike adult populations, who more

frequently die at home or in hospice-type settings,more than

half of the children with acute and chronic illnesses die in inpa-

tient hospital settings.6 So providing comprehensive and com-

passionate end-of-life (EOL) care for these children within a

family-centered and developmentally appropriate contextis

necessary.7 End-of-life care is an important method of care for

infants and children with terminal illness through the preven-

tion or alleviation of physical, emotional, social, and spiritual

suffering.8 Unfortunately,the transition to EOL care is often

late and abrupt in pediatrics9 and seems inherently unnatural

in the mind of many parents and doctors,who often struggle

to accept that nothing more can be done for a child.10Pediatric

palliative care (PPC) is a relatively new and developing speci-

alty,11which begins when an illness is diagnosed and continues

regardless of whether or not a child receives treatment directed

at the disease.12Health care professionals face numerous obst

cles and challenges while providing care to this unique pop

tion of clients and their families,2 which differ from those cited

for adults.13 Although interdisciplinary care is essentialfor

EOL care quality,nurses play the key role ofchild-family

advocate.1

Reviewing literature indicated a few studies13-15

that exam-

ined the views of pediatric nurses on providing pediatric EO

care.14 In Western countries including United States,Beck-

strand etal14 using modified version of NationalSurvey of

critical Nurses’ Perceptions Regarding End-of-Life Care que

tionnaire asked 474 pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) nu

to rate size and frequency of listed obstacles and supportiv

behaviors in providing pediatric EOL care. They found that

item ‘‘language barriers’’ was the highestperceived obstacle

with both the highestmean intensity and frequency scores.14

In Spain,Iglesias et al16 used the samequestionnaire to deter-

mine the relative importance of helpful behaviors and obst

1Razifaculty of Nursing and Midwifery,Kerman,Iran

2Neuroscience Research Center,Institute ofNeuropharmacology,Kerman

University of MedicalSciences,Kerman,Iran

Corresponding Author:

Marjan Banazadeh,MSc,Razi faculty ofNursingand Midwifery,Kerman,

86618 Iran.

Email:banazadeh54@yahoo.com

American Journalof Hospice

& Palliative Medicine®

1-9

ª The Author(s) 2014

Reprints and permission:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1049909114556878

ajhpm.sagepub.com

at UNIV OF FLORIDA on November 14, 2015ajh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Nursing Staff’s Perception of Barriers in

Providing End-of-Life Care to Terminally Ill

Pediatric Patients in Southeast Iran

Sedigheh Iranmanesh, PhD, MSc1, Marjan Banazadeh, MSc1,

and Mansoure Azizzadeh Forozy, MSc2

Abstract

Objective:To determine pediatric nurses’perceptions ofintensity,frequency occurrence,and magnitude score ofselected

barriers in providing pediatric end-of-life (EOL) care. Method: A translated modified version of National Survey o

Nurses’ s Regarding End-of-Life Care questionnaire was used to assess 151 nurses’ perceptions of intensity and

rence of barriers in caring for dying children. Results: The highest/lowest perceived barriers magnitude scores w

accepting poor child prognosis’’ (5.04) and ‘‘continuing to provide advanced treatment to dying child because o

to the hospital’’ (2.19). conclusion: More high perceived barriers by nurses were family-related issues. One of th

of such deficiencies was lack of palliative care (PC) education/PC units in Iran. Thus, developing EOL/PC educati

nurses’knowledge/skillto face EOL care challenges.

Keywords

nurses’perception,barriers,end-of-life care,terminally illchildren,Southeast Iran

Introduction

The idea that a child may die is simply unimaginable to most

people,yet children die daily.1 According to Morgan,2 when

a child dies, this cycle seems unnatural, causing loss of human

potential,and dreamsquickly shatter.2 Children represent

health and hope, and their death calls into question the under-

standing of life.3 Unfortunately, annually about 50 000 children

die in the United States.4 Of these, over half die during the first

year of life.5 A child’s chronic illness may progress to the point

of becoming a terminal illness that deemed to be incurable, ulti-

mately leading to death.1 Unlike adult populations, who more

frequently die at home or in hospice-type settings,more than

half of the children with acute and chronic illnesses die in inpa-

tient hospital settings.6 So providing comprehensive and com-

passionate end-of-life (EOL) care for these children within a

family-centered and developmentally appropriate contextis

necessary.7 End-of-life care is an important method of care for

infants and children with terminal illness through the preven-

tion or alleviation of physical, emotional, social, and spiritual

suffering.8 Unfortunately,the transition to EOL care is often

late and abrupt in pediatrics9 and seems inherently unnatural

in the mind of many parents and doctors,who often struggle

to accept that nothing more can be done for a child.10Pediatric

palliative care (PPC) is a relatively new and developing speci-

alty,11which begins when an illness is diagnosed and continues

regardless of whether or not a child receives treatment directed

at the disease.12Health care professionals face numerous obst

cles and challenges while providing care to this unique pop

tion of clients and their families,2 which differ from those cited

for adults.13 Although interdisciplinary care is essentialfor

EOL care quality,nurses play the key role ofchild-family

advocate.1

Reviewing literature indicated a few studies13-15

that exam-

ined the views of pediatric nurses on providing pediatric EO

care.14 In Western countries including United States,Beck-

strand etal14 using modified version of NationalSurvey of

critical Nurses’ Perceptions Regarding End-of-Life Care que

tionnaire asked 474 pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) nu

to rate size and frequency of listed obstacles and supportiv

behaviors in providing pediatric EOL care. They found that

item ‘‘language barriers’’ was the highestperceived obstacle

with both the highestmean intensity and frequency scores.14

In Spain,Iglesias et al16 used the samequestionnaire to deter-

mine the relative importance of helpful behaviors and obst

1Razifaculty of Nursing and Midwifery,Kerman,Iran

2Neuroscience Research Center,Institute ofNeuropharmacology,Kerman

University of MedicalSciences,Kerman,Iran

Corresponding Author:

Marjan Banazadeh,MSc,Razi faculty ofNursingand Midwifery,Kerman,

86618 Iran.

Email:banazadeh54@yahoo.com

American Journalof Hospice

& Palliative Medicine®

1-9

ª The Author(s) 2014

Reprints and permission:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1049909114556878

ajhpm.sagepub.com

at UNIV OF FLORIDA on November 14, 2015ajh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

that affect EOL care for pediatric patients and their families in

PICUs as perceived by nurses. Nurses viewed ‘‘evasive physi-

cians’’ and ‘‘families are not accepting of a poor prognosis’’ as

obstacles.16In California, Davies et al13also conducted a study

using a self-report questionnaire to explore the barriers to pal-

liative care (PC) experienced by pediatric health professionals

(117 nurses and 81 doctors).Approximately one half of the

respondents reported ‘‘uncertain prognosis,’’ ‘‘family not ready

to acknowledge incurable condition,’’ and ‘‘language barriers’’

as frequently or almost always occurring barriers.13 In Egypt,

Moawad15 using the NSCCNR-EOLC questionnaire assessed

94 PICU and NICU nurses’ perceptions of obstacles and sup-

portive behaviors in providing EOL care. He revealed that the

most perceived obstacle by nurses was ‘‘child having pain that

is difficult to control or alleviate.’’15

To our knowledge, in the context of Iran, no study has been

conducted to assess barriers in providing pediatric EOL care.

This study,thus,conducted to assess nurses’ perceptions of

intensity,frequency,and magnitude score of selected barriers

in providing pediatric EOL care in pediatric units in Kerman

hospitals.

Context

Death in different cultures has become inextricably linked in

the particularceremonies and customs,which originated in

inconsolable affections and feelings that has been painful expe-

rience.17 Therefore, it seems necessary to mention the context

in this study. Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, is a

diverse country consisting of people with many ethnic back-

grounds cemented by the Persian culture.The main language

spoken is Farsi or Persian.18Persian literature, which is heavily

informed and influenced by Islamic and mysticalspiritual

beliefs,is fraughtwith poems and stories thatportray death

as a glorious incident that takes people from one stage of their

material/mortalexistencethrough to therealm of divine

immortality.19,20

In the most celebrated and the great mystical

Persian poems, Masnavi, Rumi narrates that death is the time of

release from this cage of the body; the time when the bird of the

soul flies free.The body,like a mother,is pregnant with the

spirit-child: death is the labor of birth. All the spirits who have

passed over are waiting to see how that proud spirit shall be

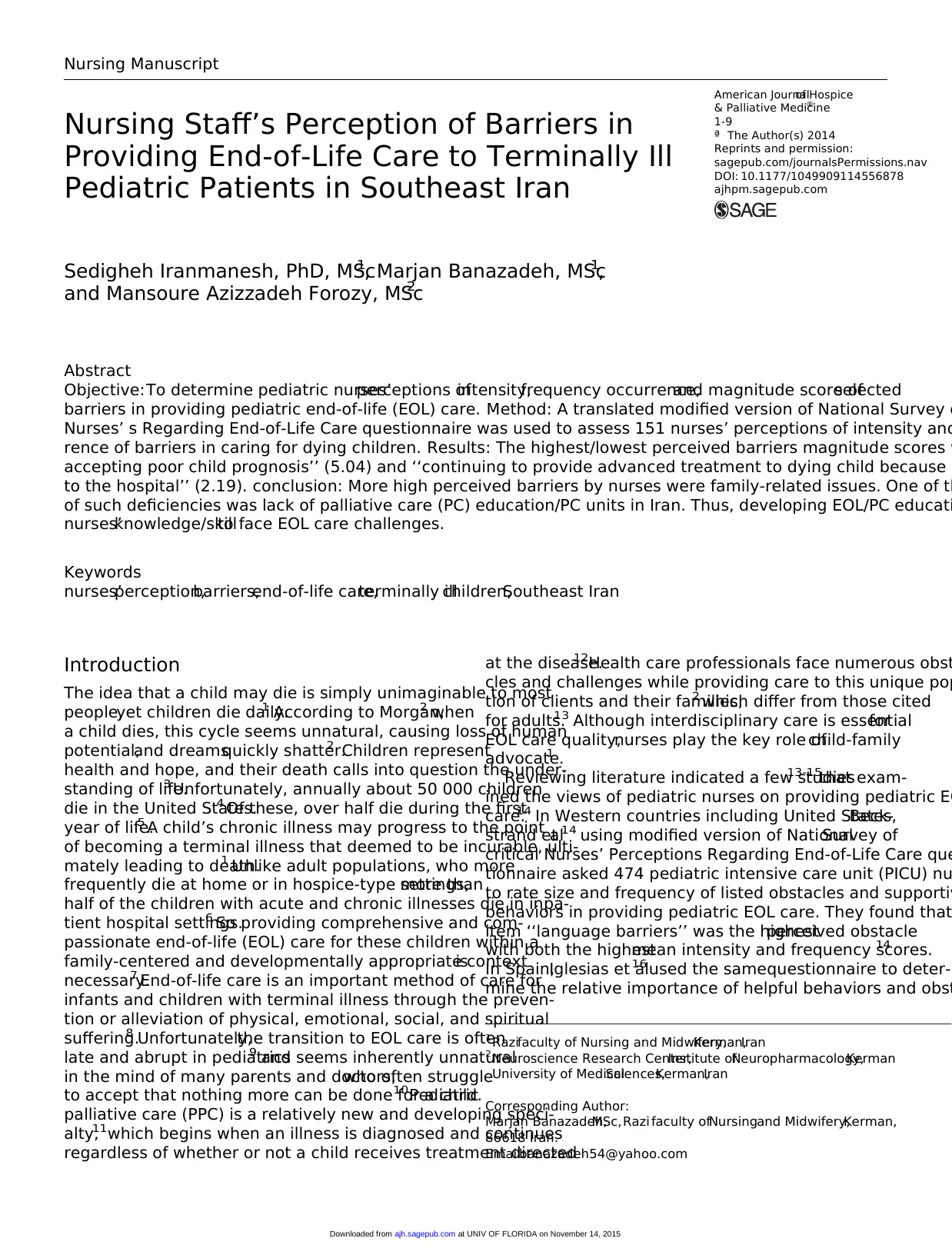

born.21 Health care in Iran is based on the following 3 pillars:

the public-governmentalsystem,the private sector,and non-

governmentalorganizations22 (NGOs).According to Mehr-

dad,23 health care and public health servicesare provided

through a nation-wide network consisting of a referral system,

starting at primary care centers in the periphery going through

secondary-level hospitals in the provincial capital and tertiary

hospitals in majorcities,which is.managed by Ministry of

Health and Medical Education (Figure 1). He goes on that there

are many NGOs activein healthissuesin Iran. Non-

governmental organizations are mainly active in special fields

like breast cancer, diabetes, thalassemia, and children with can-

cer (MAHAK), which are run by charitable foundations. This

organization was founded in 1991.It is funded entirely by

donations and has supported 11 505 children over the pas

years.23Iranian children are cared for within the primary hea

care (PHC) system up to the age of 6 years.24

According to Lankarani,25the expansion of medical educa-

tion despite suffering from an 8-year imposed war, as well

facing a 29-year lasting sanction has fulfilled all the health

medical sciences needs in higher education (as it is indicat

Table 1). In line with many developing countries,33 PHC ser-

vices in Iran do not offer any kind of palliative and EOL car

to patients and their families. Although providing specific c

services is highly recommended within the second and thir

levels of the PHC system in the country,34 PC has notbeen

accepted by the Ministry of Health and MedicalEducation,

as well as by the administrative and political health author

However,outpatientpalliative department(OPD) hasbeen

newly established (since 3 years) in 2 large cities (Tehran a

Isfahan),and one of the cities (Isfahan) also has a PC unit.35

Palliative care and PPC education is neither included as spe

cific clinical education nor as a specific academic course in

Iranian nursing educational curriculum. The BSc nurses’ cu

culum contains only 2 to 4 hours of theoretical education a

death and caring for a dead body.Recently,just 1 credit unit

about PC was added to MSc of critical care nursing curricul

Method

Design

This is a cross-sectional, descriptive study that examined p

tric nurses’ perceptions of intensity and frequency occurre

of selected barriers in caring for dying children. Approval o

the study was received by Kerman Medical University (KMU

There was also an approval from the heads of 2 hospitals s

vised by KMU, prior to the collection of data.

Sample

The sample consists of staff nurses working in pediatric un

including pediatric general units, pediatric oncology units,

and pediatric emergency units in 2 hospitals (Shahidbahon

University of

Province

SchoolsTeaching hospitals

District general

hospital

District’s health

network

District health

center

Urban health center

Health post

Rural health center

Health house

Ministry of Health and

Medical Education

Figure 1. Health system network in Iran.23

2 American Journalof Hospice & Palliative Medicine®

at UNIV OF FLORIDA on November 14, 2015ajh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

PICUs as perceived by nurses. Nurses viewed ‘‘evasive physi-

cians’’ and ‘‘families are not accepting of a poor prognosis’’ as

obstacles.16In California, Davies et al13also conducted a study

using a self-report questionnaire to explore the barriers to pal-

liative care (PC) experienced by pediatric health professionals

(117 nurses and 81 doctors).Approximately one half of the

respondents reported ‘‘uncertain prognosis,’’ ‘‘family not ready

to acknowledge incurable condition,’’ and ‘‘language barriers’’

as frequently or almost always occurring barriers.13 In Egypt,

Moawad15 using the NSCCNR-EOLC questionnaire assessed

94 PICU and NICU nurses’ perceptions of obstacles and sup-

portive behaviors in providing EOL care. He revealed that the

most perceived obstacle by nurses was ‘‘child having pain that

is difficult to control or alleviate.’’15

To our knowledge, in the context of Iran, no study has been

conducted to assess barriers in providing pediatric EOL care.

This study,thus,conducted to assess nurses’ perceptions of

intensity,frequency,and magnitude score of selected barriers

in providing pediatric EOL care in pediatric units in Kerman

hospitals.

Context

Death in different cultures has become inextricably linked in

the particularceremonies and customs,which originated in

inconsolable affections and feelings that has been painful expe-

rience.17 Therefore, it seems necessary to mention the context

in this study. Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, is a

diverse country consisting of people with many ethnic back-

grounds cemented by the Persian culture.The main language

spoken is Farsi or Persian.18Persian literature, which is heavily

informed and influenced by Islamic and mysticalspiritual

beliefs,is fraughtwith poems and stories thatportray death

as a glorious incident that takes people from one stage of their

material/mortalexistencethrough to therealm of divine

immortality.19,20

In the most celebrated and the great mystical

Persian poems, Masnavi, Rumi narrates that death is the time of

release from this cage of the body; the time when the bird of the

soul flies free.The body,like a mother,is pregnant with the

spirit-child: death is the labor of birth. All the spirits who have

passed over are waiting to see how that proud spirit shall be

born.21 Health care in Iran is based on the following 3 pillars:

the public-governmentalsystem,the private sector,and non-

governmentalorganizations22 (NGOs).According to Mehr-

dad,23 health care and public health servicesare provided

through a nation-wide network consisting of a referral system,

starting at primary care centers in the periphery going through

secondary-level hospitals in the provincial capital and tertiary

hospitals in majorcities,which is.managed by Ministry of

Health and Medical Education (Figure 1). He goes on that there

are many NGOs activein healthissuesin Iran. Non-

governmental organizations are mainly active in special fields

like breast cancer, diabetes, thalassemia, and children with can-

cer (MAHAK), which are run by charitable foundations. This

organization was founded in 1991.It is funded entirely by

donations and has supported 11 505 children over the pas

years.23Iranian children are cared for within the primary hea

care (PHC) system up to the age of 6 years.24

According to Lankarani,25the expansion of medical educa-

tion despite suffering from an 8-year imposed war, as well

facing a 29-year lasting sanction has fulfilled all the health

medical sciences needs in higher education (as it is indicat

Table 1). In line with many developing countries,33 PHC ser-

vices in Iran do not offer any kind of palliative and EOL car

to patients and their families. Although providing specific c

services is highly recommended within the second and thir

levels of the PHC system in the country,34 PC has notbeen

accepted by the Ministry of Health and MedicalEducation,

as well as by the administrative and political health author

However,outpatientpalliative department(OPD) hasbeen

newly established (since 3 years) in 2 large cities (Tehran a

Isfahan),and one of the cities (Isfahan) also has a PC unit.35

Palliative care and PPC education is neither included as spe

cific clinical education nor as a specific academic course in

Iranian nursing educational curriculum. The BSc nurses’ cu

culum contains only 2 to 4 hours of theoretical education a

death and caring for a dead body.Recently,just 1 credit unit

about PC was added to MSc of critical care nursing curricul

Method

Design

This is a cross-sectional, descriptive study that examined p

tric nurses’ perceptions of intensity and frequency occurre

of selected barriers in caring for dying children. Approval o

the study was received by Kerman Medical University (KMU

There was also an approval from the heads of 2 hospitals s

vised by KMU, prior to the collection of data.

Sample

The sample consists of staff nurses working in pediatric un

including pediatric general units, pediatric oncology units,

and pediatric emergency units in 2 hospitals (Shahidbahon

University of

Province

SchoolsTeaching hospitals

District general

hospital

District’s health

network

District health

center

Urban health center

Health post

Rural health center

Health house

Ministry of Health and

Medical Education

Figure 1. Health system network in Iran.23

2 American Journalof Hospice & Palliative Medicine®

at UNIV OF FLORIDA on November 14, 2015ajh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Afzalipour) supervised by KMU. Afzalipour is a general hos-

pital with 462 active beds and Shahidbahonar is a trauma hos-

pital with 367 active beds. These hospitals located in an area

called Kerman in the center of Kerman Province in Southeast

Iran, which provides medical services for the whole province.

All nurses working in the aforementioned units were surveyed.

Staff nurses who were considered eligible for the study had at

least six-months working experience in these units and pro

vided care to dying children.

Background Information

First,a demographic questionnaire consisting of 17 questio

thatwas assumed to influence pediatric nurses’perceptions

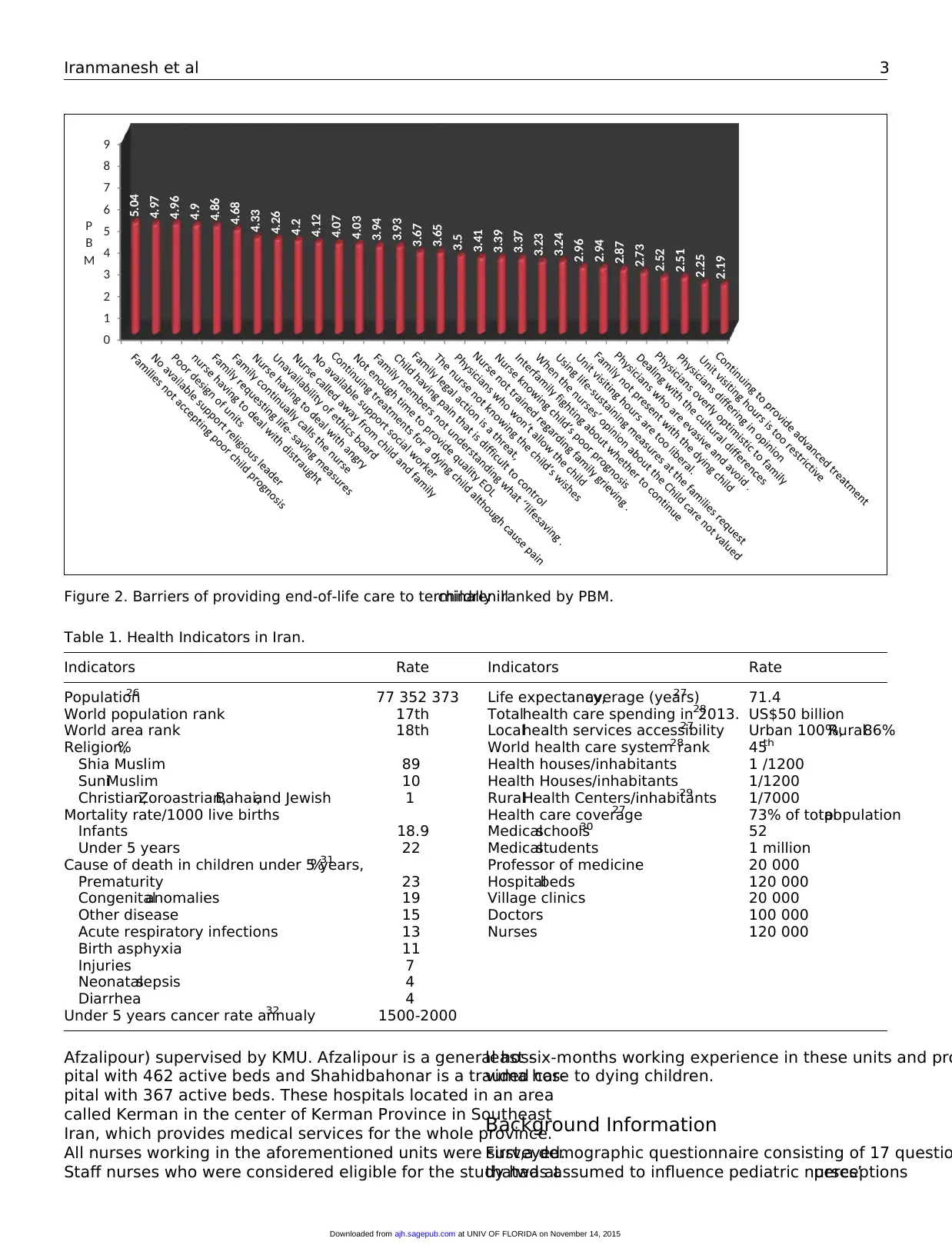

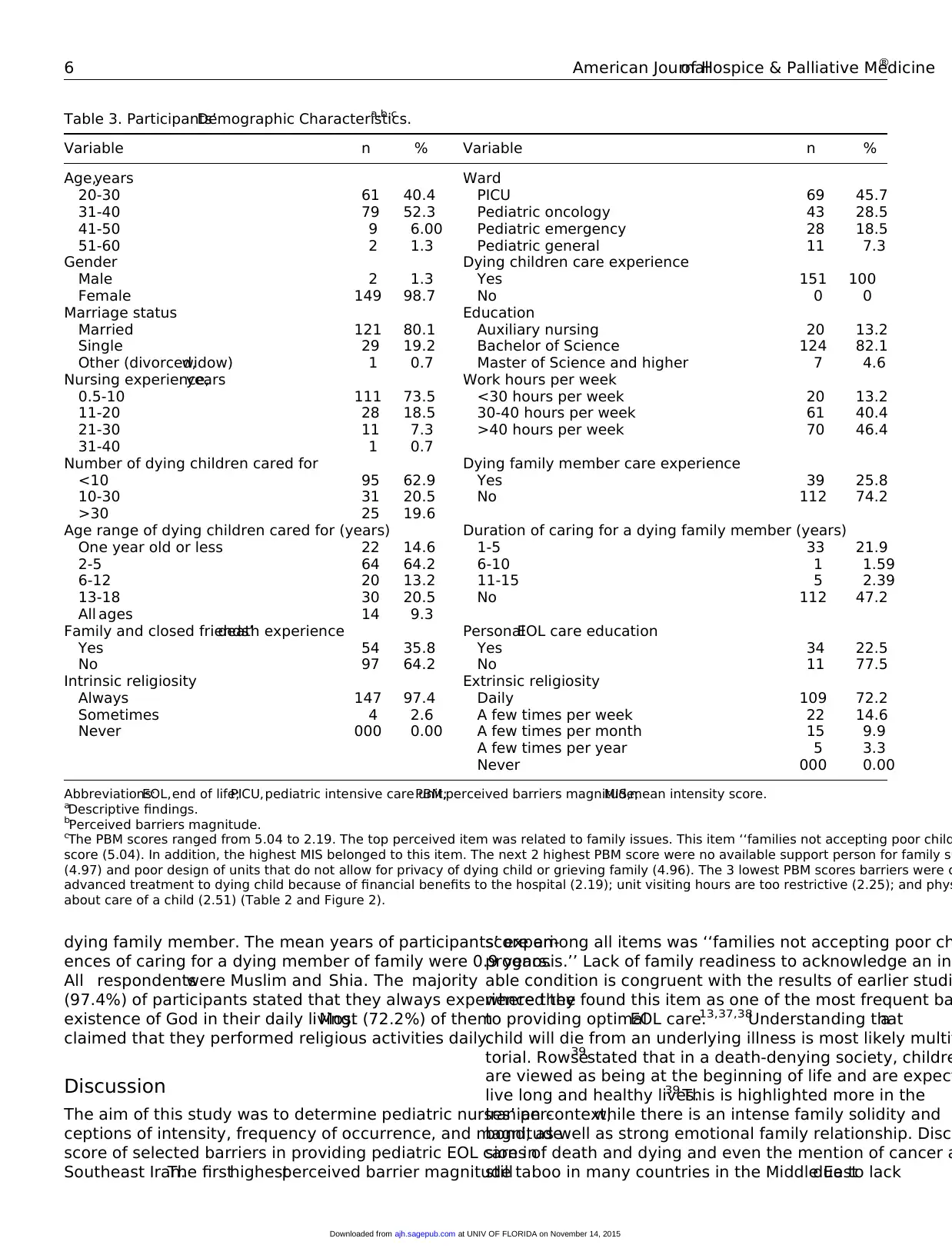

Table 1. Health Indicators in Iran.

Indicators Rate Indicators Rate

Population26 77 352 373 Life expectancy,average (years)27 71.4

World population rank 17th Totalhealth care spending in 2013.28 US$50 billion

World area rank 18th Localhealth services accessibility27 Urban 100%,Rural86%

Religion,% World health care system rank28 45th

Shia Muslim 89 Health houses/inhabitants 1 /1200

SuniMuslim 10 Health Houses/inhabitants 1/1200

Christian,Zoroastrian,Bahai,and Jewish 1 RuralHealth Centers/inhabitants29 1/7000

Mortality rate/1000 live births Health care coverage27 73% of totalpopulation

Infants 18.9 Medicalschools30 52

Under 5 years 22 Medicalstudents 1 million

Cause of death in children under 5 years,%31 Professor of medicine 20 000

Prematurity 23 Hospitalbeds 120 000

Congenitalanomalies 19 Village clinics 20 000

Other disease 15 Doctors 100 000

Acute respiratory infections 13 Nurses 120 000

Birth asphyxia 11

Injuries 7

Neonatalsepsis 4

Diarrhea 4

Under 5 years cancer rate annualy32 1500-2000

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

5.04

4.97

4.96

4.9

4.86

4.68

4.33

4.26

4.2

4.12

4.07

4.03

3.94

3.93

3.67

3.65

3.5

3.41

3.39

3.37

3.23

3.24

2.96

2.94

2.87

2.73

2.52

2.51

2.25

2.19

P

B

M

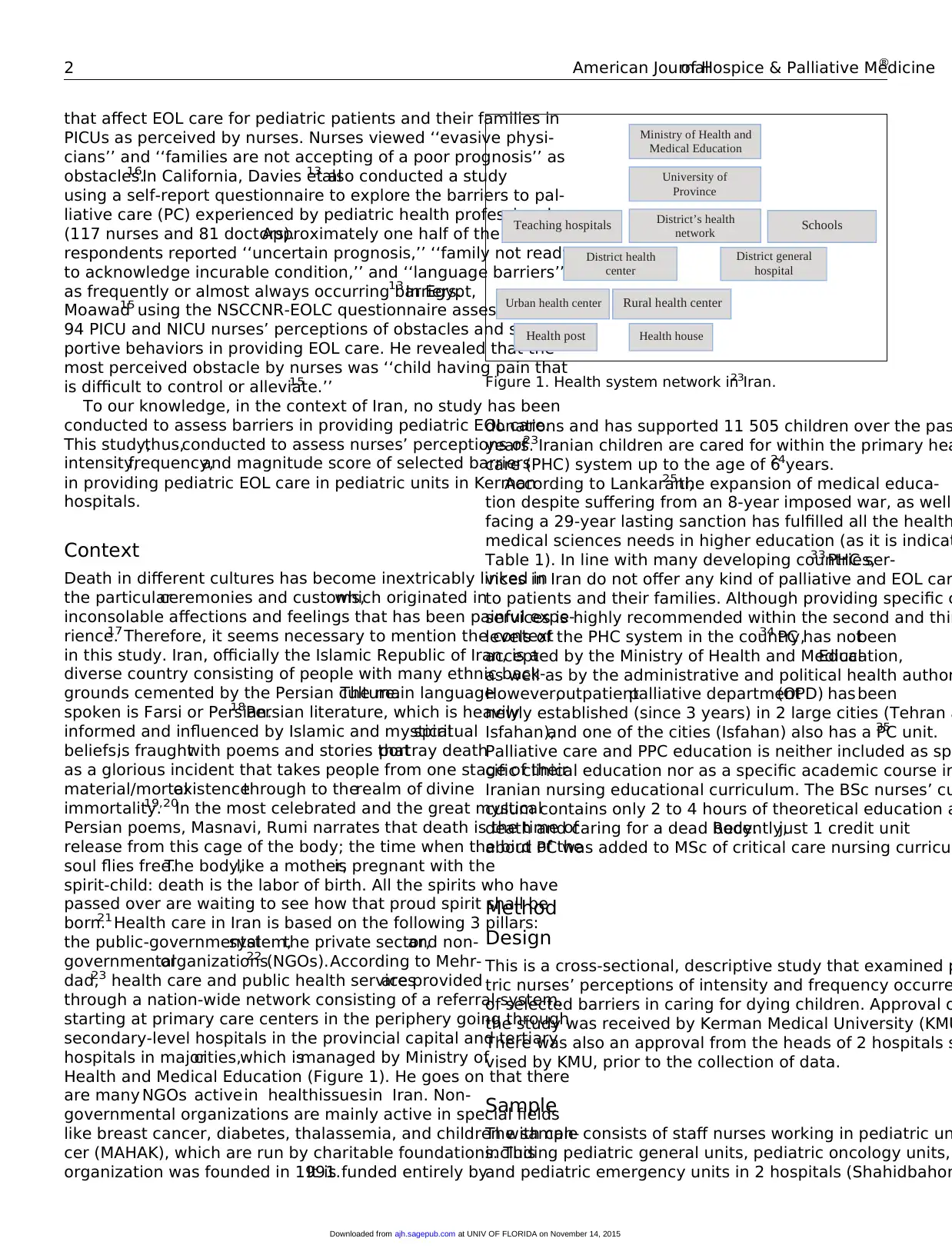

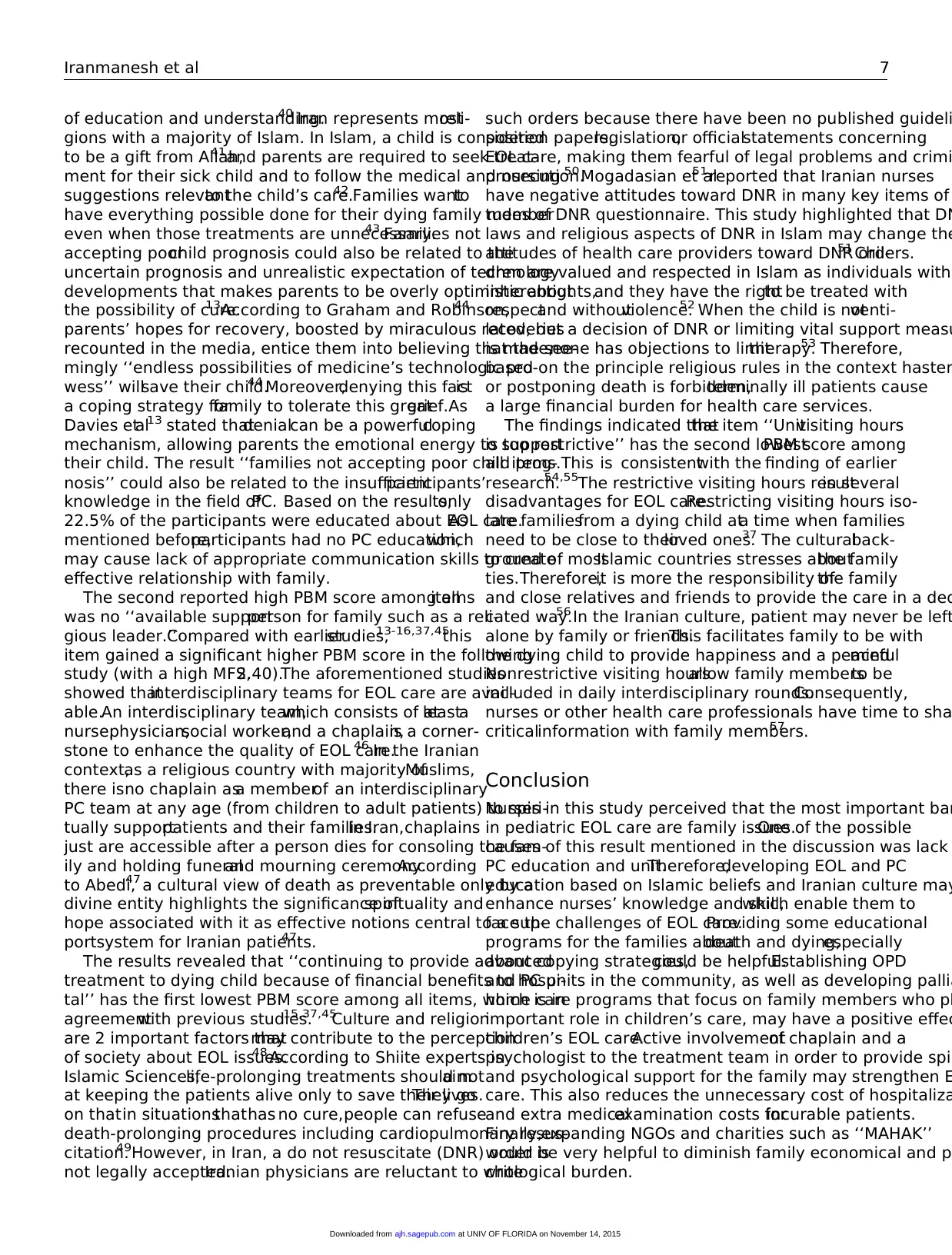

Figure 2. Barriers of providing end-of-life care to terminally illchildren ranked by PBM.

Iranmanesh et al 3

at UNIV OF FLORIDA on November 14, 2015ajh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

pital with 462 active beds and Shahidbahonar is a trauma hos-

pital with 367 active beds. These hospitals located in an area

called Kerman in the center of Kerman Province in Southeast

Iran, which provides medical services for the whole province.

All nurses working in the aforementioned units were surveyed.

Staff nurses who were considered eligible for the study had at

least six-months working experience in these units and pro

vided care to dying children.

Background Information

First,a demographic questionnaire consisting of 17 questio

thatwas assumed to influence pediatric nurses’perceptions

Table 1. Health Indicators in Iran.

Indicators Rate Indicators Rate

Population26 77 352 373 Life expectancy,average (years)27 71.4

World population rank 17th Totalhealth care spending in 2013.28 US$50 billion

World area rank 18th Localhealth services accessibility27 Urban 100%,Rural86%

Religion,% World health care system rank28 45th

Shia Muslim 89 Health houses/inhabitants 1 /1200

SuniMuslim 10 Health Houses/inhabitants 1/1200

Christian,Zoroastrian,Bahai,and Jewish 1 RuralHealth Centers/inhabitants29 1/7000

Mortality rate/1000 live births Health care coverage27 73% of totalpopulation

Infants 18.9 Medicalschools30 52

Under 5 years 22 Medicalstudents 1 million

Cause of death in children under 5 years,%31 Professor of medicine 20 000

Prematurity 23 Hospitalbeds 120 000

Congenitalanomalies 19 Village clinics 20 000

Other disease 15 Doctors 100 000

Acute respiratory infections 13 Nurses 120 000

Birth asphyxia 11

Injuries 7

Neonatalsepsis 4

Diarrhea 4

Under 5 years cancer rate annualy32 1500-2000

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

5.04

4.97

4.96

4.9

4.86

4.68

4.33

4.26

4.2

4.12

4.07

4.03

3.94

3.93

3.67

3.65

3.5

3.41

3.39

3.37

3.23

3.24

2.96

2.94

2.87

2.73

2.52

2.51

2.25

2.19

P

B

M

Figure 2. Barriers of providing end-of-life care to terminally illchildren ranked by PBM.

Iranmanesh et al 3

at UNIV OF FLORIDA on November 14, 2015ajh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

of barriers in providing pediatric EOL care was designed. The

questions developed were based on previous literature review

and authors’ experiences.The items included the following 4

categories: (1) personal characteristics like gender,age,mar-

riage status, and level of education; (2) professional character-

istics like ward, work hours per week, number, and age range of

dying children who were cared for;(3) previouspersonal

experiences related to death and dying,such as family and

closed friends’ death experience,dying family member care

experience, duration of caring for a dying family member, and

personal EOL care education; and (4) religiosity index consist-

ing of intrinsic (belief in God) and extrinsic (attendance at reli-

gious services and activities) religiosity.

Instrument

To determine pediatric nurses’perceptions ofintensity,fre-

quency occurrence,and magnitude score of selected barriers

in providing pediatric EOL care, a translated modified version

of the NSCCNR-EOLC questionnaire was used. This question-

naire was developed, pretested, and administered in 1998 and

revised in 2005.36 The final version of questionnaire consists

of 56 items including 29 obstacle items,24 supportive beha-

viors,and 3 open-ended questions.37 Separate responses are

required for intensity and frequency. Barriers intensity and fre-

quency were rated on a 6-pointLikert-type scale.For this

study, the 6 intensity and frequency alternatives in the original

article were grouped together in a single category, and 6 levels

were reduced to 4 levels including 0 ¼ not a barrier, 1 ¼ little

barrier,2 ¼ moderate barrier,and 3 ¼ large barrier and 0 ¼

never happens,1 ¼ rarely happens,2 ¼ sometimes happens,

and 3 ¼ always happens.The items are ranked from highest

to lowest based on their mean scores to determine which items

are perceived to be the mostintense obstacles or supportive

behaviors and which items are perceived to occur mostfre-

quent. To determine which barrier items were perceived as the

most intense and the most frequently occurring, the mean inten-

sity score (MIS) of each item was multiplied by the item’s

mean frequency score (MFS) to achieve an overall perceived

barriers magnitude (PBM) score. The possible perceived mag-

nitude score for each item ranged from 0 to 25 and for the fol-

lowing study 0 to 9. For the current study, facilitator items and

3 open-ended questions were omitted and just barriers subscale

was used. For translation of the questionnaire from English into

Farsi,the standard forward-backward procedure was applied.

Translation of the items was performed by 2 professional trans-

lators (SI and MAF) who are nurse educators. Their native lan-

guage is Farsi,and their second language is English.Both of

them have had experience of living abroad,and SI was edu-

cated about PC in a Western country for 5 years. Therefore, she

has knowledge about EOL and PC in both Eastern and Western

cultures.A helpful reference atthis stage wasthe Haiiem

English-Farsi dictionary. Based on their religious beliefs, they

suggested that it is better to divide the item ‘‘Family not having

a support person, for example, social worker or religious leader’’

to 2 items including family not having a support person,for

example, social worker and family not having a support pe

for example,religious leader.They believed thateach item

should not be devoted to more than one concept.Therefore,

the totalbarriers were 30 items.Afterward they were back-

translated into English, and after a careful cultural adaptat

the final versions were provided. The translated questionn

wentthrough pilottesting.Suggestions by nurses (n ¼ 20)

were combined into the final questionnaire versions.

Reliability and Validity

Reliability and content validity for NSCCNR-EOLC has been

checked in previous research.27The authors found an accepta-

ble validity and reliability for the instrument. In Iran, no stu

was found that assessed the reliability and validity of this s

therefore,the validity and reliabilityof the scale was

rechecked. The validity of scale was assessed through a co

validity.Ten faculty members at the Nursing and Midwifery

School reviewed the contents of the scales from cultural an

religious perspectives.They leftthe same suggestions as the

translators. They agreed that the translated scale has an a

table validity. These experts were also asked to independe

rate each item in terms of its relevance, clarity, and simpli

on a 4-point scale. According to their comments, to reasse

reliability of translated scale, an a coefficient of internal co

sistency (n ¼ 20) was computed. The a coefficient for the

was 0.91. Therefore, the translated scale presented accep

reliability.The questionnaire obtained an acceptable validity

(content validity index [CVI] ¼ 0.92) for barriers section an

for facilitators section (CVI ¼ 0.89).

Data Collection and Analysis

Accompanied by a letter, including some information abou

aim of the study, the questionnaires were handed out by th

ond author to all the convenient staff nurses (registered nu

and auxiliary nurses) working in the mentioned pediatric u

during the 2 months (November/December 2013).Some oral

information aboutthe study was also given by the second

author to all participants in a seminar. Informed consent fo

was obtained from allthe participants.Participation in the

study was voluntary and anonymous. In total, 173 sets of q

tionnaires were distributed with a dropout of 22.Finally,151

nurses (response rate, 87.2%) were included in the study.

from the questionnaires were analyzed using Statistical Pa

age for SocialScientists (SPSS version 21).A Kolmogorov-

Smirnov test indicated that the data were extracted from a

ulation with a normaldistribution descriptive statistics was

computed for the study variables. Mean scores were indivi

ally computed for the intensity and frequency for each item

Items were ranked according to their mean scores to deter

which ones were perceived as the most intense barriers, a

as the most frequent barriers. In addition, the PBM scores

ranked from highest to lowest.Based on the purposes of this

study,emphasis was placed on the overallmagnitude scores

to answer the research questions (Table 2).

4 American Journalof Hospice & Palliative Medicine®

at UNIV OF FLORIDA on November 14, 2015ajh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

questions developed were based on previous literature review

and authors’ experiences.The items included the following 4

categories: (1) personal characteristics like gender,age,mar-

riage status, and level of education; (2) professional character-

istics like ward, work hours per week, number, and age range of

dying children who were cared for;(3) previouspersonal

experiences related to death and dying,such as family and

closed friends’ death experience,dying family member care

experience, duration of caring for a dying family member, and

personal EOL care education; and (4) religiosity index consist-

ing of intrinsic (belief in God) and extrinsic (attendance at reli-

gious services and activities) religiosity.

Instrument

To determine pediatric nurses’perceptions ofintensity,fre-

quency occurrence,and magnitude score of selected barriers

in providing pediatric EOL care, a translated modified version

of the NSCCNR-EOLC questionnaire was used. This question-

naire was developed, pretested, and administered in 1998 and

revised in 2005.36 The final version of questionnaire consists

of 56 items including 29 obstacle items,24 supportive beha-

viors,and 3 open-ended questions.37 Separate responses are

required for intensity and frequency. Barriers intensity and fre-

quency were rated on a 6-pointLikert-type scale.For this

study, the 6 intensity and frequency alternatives in the original

article were grouped together in a single category, and 6 levels

were reduced to 4 levels including 0 ¼ not a barrier, 1 ¼ little

barrier,2 ¼ moderate barrier,and 3 ¼ large barrier and 0 ¼

never happens,1 ¼ rarely happens,2 ¼ sometimes happens,

and 3 ¼ always happens.The items are ranked from highest

to lowest based on their mean scores to determine which items

are perceived to be the mostintense obstacles or supportive

behaviors and which items are perceived to occur mostfre-

quent. To determine which barrier items were perceived as the

most intense and the most frequently occurring, the mean inten-

sity score (MIS) of each item was multiplied by the item’s

mean frequency score (MFS) to achieve an overall perceived

barriers magnitude (PBM) score. The possible perceived mag-

nitude score for each item ranged from 0 to 25 and for the fol-

lowing study 0 to 9. For the current study, facilitator items and

3 open-ended questions were omitted and just barriers subscale

was used. For translation of the questionnaire from English into

Farsi,the standard forward-backward procedure was applied.

Translation of the items was performed by 2 professional trans-

lators (SI and MAF) who are nurse educators. Their native lan-

guage is Farsi,and their second language is English.Both of

them have had experience of living abroad,and SI was edu-

cated about PC in a Western country for 5 years. Therefore, she

has knowledge about EOL and PC in both Eastern and Western

cultures.A helpful reference atthis stage wasthe Haiiem

English-Farsi dictionary. Based on their religious beliefs, they

suggested that it is better to divide the item ‘‘Family not having

a support person, for example, social worker or religious leader’’

to 2 items including family not having a support person,for

example, social worker and family not having a support pe

for example,religious leader.They believed thateach item

should not be devoted to more than one concept.Therefore,

the totalbarriers were 30 items.Afterward they were back-

translated into English, and after a careful cultural adaptat

the final versions were provided. The translated questionn

wentthrough pilottesting.Suggestions by nurses (n ¼ 20)

were combined into the final questionnaire versions.

Reliability and Validity

Reliability and content validity for NSCCNR-EOLC has been

checked in previous research.27The authors found an accepta-

ble validity and reliability for the instrument. In Iran, no stu

was found that assessed the reliability and validity of this s

therefore,the validity and reliabilityof the scale was

rechecked. The validity of scale was assessed through a co

validity.Ten faculty members at the Nursing and Midwifery

School reviewed the contents of the scales from cultural an

religious perspectives.They leftthe same suggestions as the

translators. They agreed that the translated scale has an a

table validity. These experts were also asked to independe

rate each item in terms of its relevance, clarity, and simpli

on a 4-point scale. According to their comments, to reasse

reliability of translated scale, an a coefficient of internal co

sistency (n ¼ 20) was computed. The a coefficient for the

was 0.91. Therefore, the translated scale presented accep

reliability.The questionnaire obtained an acceptable validity

(content validity index [CVI] ¼ 0.92) for barriers section an

for facilitators section (CVI ¼ 0.89).

Data Collection and Analysis

Accompanied by a letter, including some information abou

aim of the study, the questionnaires were handed out by th

ond author to all the convenient staff nurses (registered nu

and auxiliary nurses) working in the mentioned pediatric u

during the 2 months (November/December 2013).Some oral

information aboutthe study was also given by the second

author to all participants in a seminar. Informed consent fo

was obtained from allthe participants.Participation in the

study was voluntary and anonymous. In total, 173 sets of q

tionnaires were distributed with a dropout of 22.Finally,151

nurses (response rate, 87.2%) were included in the study.

from the questionnaires were analyzed using Statistical Pa

age for SocialScientists (SPSS version 21).A Kolmogorov-

Smirnov test indicated that the data were extracted from a

ulation with a normaldistribution descriptive statistics was

computed for the study variables. Mean scores were indivi

ally computed for the intensity and frequency for each item

Items were ranked according to their mean scores to deter

which ones were perceived as the most intense barriers, a

as the most frequent barriers. In addition, the PBM scores

ranked from highest to lowest.Based on the purposes of this

study,emphasis was placed on the overallmagnitude scores

to answer the research questions (Table 2).

4 American Journalof Hospice & Palliative Medicine®

at UNIV OF FLORIDA on November 14, 2015ajh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Results

Participants

The sample consisted of 151 participants. A descriptive analy-

sis of background information (Table 3) revealed that the par-

ticipants’ age ranged from 20 to 65 years with a mean age of

32.7 years (standard deviation [SD] ¼ 6.12). They were mainly

female (98.7%) and married (80.1). Most of them had a B Sc in

nursing (82.1) and stated that they receive no education about

EOL care (77.5%).Approximately half (54.3) of participants

were working in non-ICUs including pediatric generalunits,

pediatric oncology units,and pediatric emergency unit.Rest

(45.7)of them wasworking in PICUs. The participants

reported that they had experience of 0.5 to 31 years in nu

with a mean of 8.7 years (SD ¼ 6.63). All the participants e

rienced caring for dying children. More than half (62.9) of t

cared for less than 10 dying children during their professio

career. The age of less than half of the dying pediatric pati

(42.4) ranged between 2 and 5 years. Reported weekly em

menthours ranged from less than 30 hours to more than 40

hours;46% ofthe participants worked more than 40 hours

weekly;25.8% ofthe participants experienced caring fora

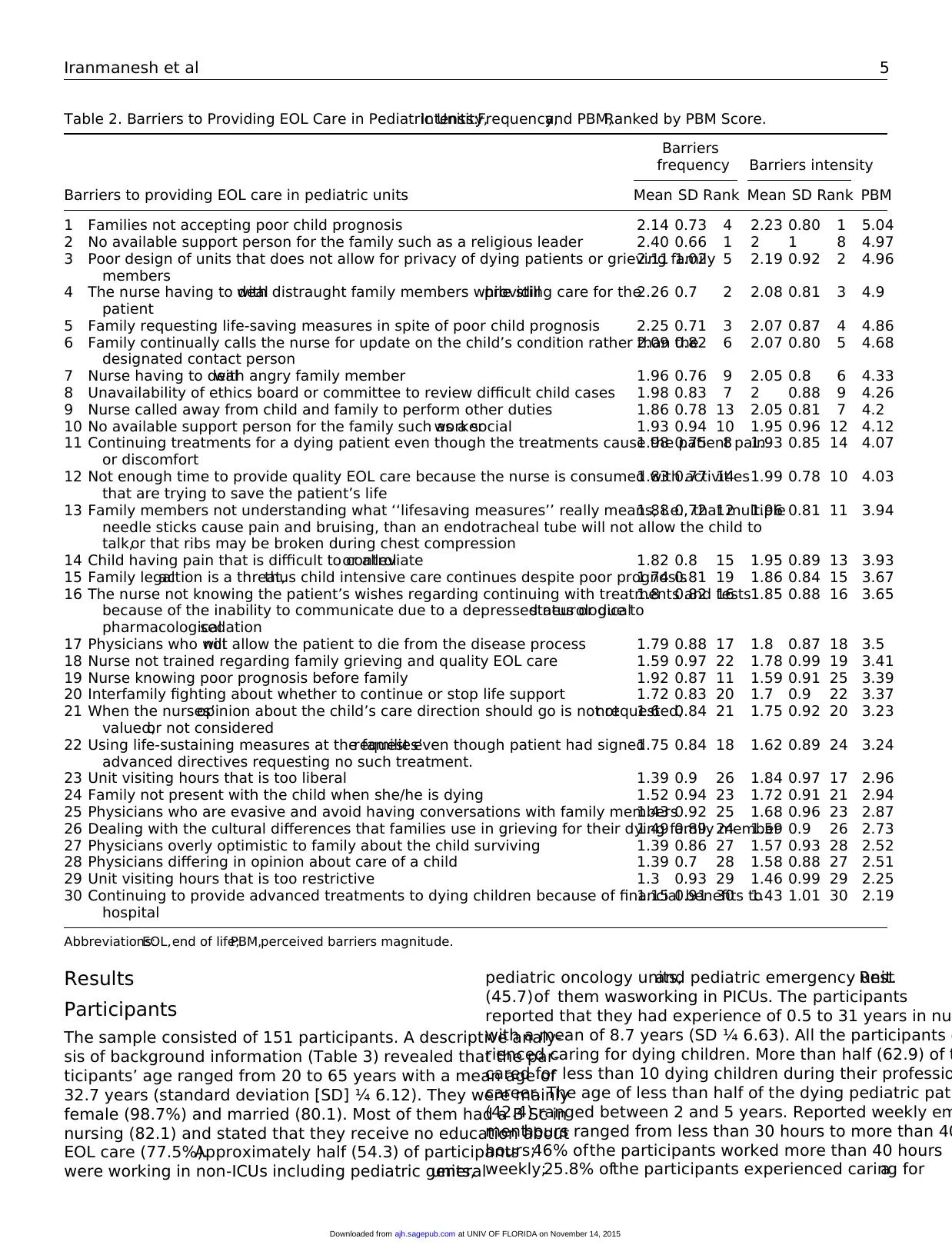

Table 2. Barriers to Providing EOL Care in Pediatric Units:Intensity,Frequency,and PBM,Ranked by PBM Score.

Barriers to providing EOL care in pediatric units

Barriers

frequency Barriers intensity

PBMMean SD Rank Mean SD Rank

1 Families not accepting poor child prognosis 2.14 0.73 4 2.23 0.80 1 5.04

2 No available support person for the family such as a religious leader 2.40 0.66 1 2 1 8 4.97

3 Poor design of units that does not allow for privacy of dying patients or grieving family

members

2.11 1.02 5 2.19 0.92 2 4.96

4 The nurse having to dealwith distraught family members while stillproviding care for the

patient

2.26 0.7 2 2.08 0.81 3 4.9

5 Family requesting life-saving measures in spite of poor child prognosis 2.25 0.71 3 2.07 0.87 4 4.86

6 Family continually calls the nurse for update on the child’s condition rather than the

designated contact person

2.09 0.82 6 2.07 0.80 5 4.68

7 Nurse having to dealwith angry family member 1.96 0.76 9 2.05 0.8 6 4.33

8 Unavailability of ethics board or committee to review difficult child cases 1.98 0.83 7 2 0.88 9 4.26

9 Nurse called away from child and family to perform other duties 1.86 0.78 13 2.05 0.81 7 4.2

10 No available support person for the family such as a socialworker 1.93 0.94 10 1.95 0.96 12 4.12

11 Continuing treatments for a dying patient even though the treatments cause the patient pain

or discomfort

1.98 0.75 8 1.93 0.85 14 4.07

12 Not enough time to provide quality EOL care because the nurse is consumed with activities

that are trying to save the patient’s life

1.83 0.77 14 1.99 0.78 10 4.03

13 Family members not understanding what ‘‘lifesaving measures’’ really means, i.e., that multiple

needle sticks cause pain and bruising, than an endotracheal tube will not allow the child to

talk,or that ribs may be broken during chest compression

1.88 0.72 12 1.96 0.81 11 3.94

14 Child having pain that is difficult to controlor alleviate 1.82 0.8 15 1.95 0.89 13 3.93

15 Family legalaction is a threat,thus child intensive care continues despite poor prognosis1.74 0.81 19 1.86 0.84 15 3.67

16 The nurse not knowing the patient’s wishes regarding continuing with treatments and tests

because of the inability to communicate due to a depressed neurologicalstatus or due to

pharmacologicalsedation

1.8 0.82 16 1.85 0.88 16 3.65

17 Physicians who willnot allow the patient to die from the disease process 1.79 0.88 17 1.8 0.87 18 3.5

18 Nurse not trained regarding family grieving and quality EOL care 1.59 0.97 22 1.78 0.99 19 3.41

19 Nurse knowing poor prognosis before family 1.92 0.87 11 1.59 0.91 25 3.39

20 Interfamily fighting about whether to continue or stop life support 1.72 0.83 20 1.7 0.9 22 3.37

21 When the nurses’opinion about the child’s care direction should go is not requested,not

valued,or not considered

1.6 0.84 21 1.75 0.92 20 3.23

22 Using life-sustaining measures at the families’request even though patient had signed

advanced directives requesting no such treatment.

1.75 0.84 18 1.62 0.89 24 3.24

23 Unit visiting hours that is too liberal 1.39 0.9 26 1.84 0.97 17 2.96

24 Family not present with the child when she/he is dying 1.52 0.94 23 1.72 0.91 21 2.94

25 Physicians who are evasive and avoid having conversations with family members1.43 0.92 25 1.68 0.96 23 2.87

26 Dealing with the cultural differences that families use in grieving for their dying family member1.49 0.89 24 1.59 0.9 26 2.73

27 Physicians overly optimistic to family about the child surviving 1.39 0.86 27 1.57 0.93 28 2.52

28 Physicians differing in opinion about care of a child 1.39 0.7 28 1.58 0.88 27 2.51

29 Unit visiting hours that is too restrictive 1.3 0.93 29 1.46 0.99 29 2.25

30 Continuing to provide advanced treatments to dying children because of financial benefits to

hospital

1.15 0.91 30 1.43 1.01 30 2.19

Abbreviations:EOL,end of life;PBM,perceived barriers magnitude.

Iranmanesh et al 5

at UNIV OF FLORIDA on November 14, 2015ajh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Participants

The sample consisted of 151 participants. A descriptive analy-

sis of background information (Table 3) revealed that the par-

ticipants’ age ranged from 20 to 65 years with a mean age of

32.7 years (standard deviation [SD] ¼ 6.12). They were mainly

female (98.7%) and married (80.1). Most of them had a B Sc in

nursing (82.1) and stated that they receive no education about

EOL care (77.5%).Approximately half (54.3) of participants

were working in non-ICUs including pediatric generalunits,

pediatric oncology units,and pediatric emergency unit.Rest

(45.7)of them wasworking in PICUs. The participants

reported that they had experience of 0.5 to 31 years in nu

with a mean of 8.7 years (SD ¼ 6.63). All the participants e

rienced caring for dying children. More than half (62.9) of t

cared for less than 10 dying children during their professio

career. The age of less than half of the dying pediatric pati

(42.4) ranged between 2 and 5 years. Reported weekly em

menthours ranged from less than 30 hours to more than 40

hours;46% ofthe participants worked more than 40 hours

weekly;25.8% ofthe participants experienced caring fora

Table 2. Barriers to Providing EOL Care in Pediatric Units:Intensity,Frequency,and PBM,Ranked by PBM Score.

Barriers to providing EOL care in pediatric units

Barriers

frequency Barriers intensity

PBMMean SD Rank Mean SD Rank

1 Families not accepting poor child prognosis 2.14 0.73 4 2.23 0.80 1 5.04

2 No available support person for the family such as a religious leader 2.40 0.66 1 2 1 8 4.97

3 Poor design of units that does not allow for privacy of dying patients or grieving family

members

2.11 1.02 5 2.19 0.92 2 4.96

4 The nurse having to dealwith distraught family members while stillproviding care for the

patient

2.26 0.7 2 2.08 0.81 3 4.9

5 Family requesting life-saving measures in spite of poor child prognosis 2.25 0.71 3 2.07 0.87 4 4.86

6 Family continually calls the nurse for update on the child’s condition rather than the

designated contact person

2.09 0.82 6 2.07 0.80 5 4.68

7 Nurse having to dealwith angry family member 1.96 0.76 9 2.05 0.8 6 4.33

8 Unavailability of ethics board or committee to review difficult child cases 1.98 0.83 7 2 0.88 9 4.26

9 Nurse called away from child and family to perform other duties 1.86 0.78 13 2.05 0.81 7 4.2

10 No available support person for the family such as a socialworker 1.93 0.94 10 1.95 0.96 12 4.12

11 Continuing treatments for a dying patient even though the treatments cause the patient pain

or discomfort

1.98 0.75 8 1.93 0.85 14 4.07

12 Not enough time to provide quality EOL care because the nurse is consumed with activities

that are trying to save the patient’s life

1.83 0.77 14 1.99 0.78 10 4.03

13 Family members not understanding what ‘‘lifesaving measures’’ really means, i.e., that multiple

needle sticks cause pain and bruising, than an endotracheal tube will not allow the child to

talk,or that ribs may be broken during chest compression

1.88 0.72 12 1.96 0.81 11 3.94

14 Child having pain that is difficult to controlor alleviate 1.82 0.8 15 1.95 0.89 13 3.93

15 Family legalaction is a threat,thus child intensive care continues despite poor prognosis1.74 0.81 19 1.86 0.84 15 3.67

16 The nurse not knowing the patient’s wishes regarding continuing with treatments and tests

because of the inability to communicate due to a depressed neurologicalstatus or due to

pharmacologicalsedation

1.8 0.82 16 1.85 0.88 16 3.65

17 Physicians who willnot allow the patient to die from the disease process 1.79 0.88 17 1.8 0.87 18 3.5

18 Nurse not trained regarding family grieving and quality EOL care 1.59 0.97 22 1.78 0.99 19 3.41

19 Nurse knowing poor prognosis before family 1.92 0.87 11 1.59 0.91 25 3.39

20 Interfamily fighting about whether to continue or stop life support 1.72 0.83 20 1.7 0.9 22 3.37

21 When the nurses’opinion about the child’s care direction should go is not requested,not

valued,or not considered

1.6 0.84 21 1.75 0.92 20 3.23

22 Using life-sustaining measures at the families’request even though patient had signed

advanced directives requesting no such treatment.

1.75 0.84 18 1.62 0.89 24 3.24

23 Unit visiting hours that is too liberal 1.39 0.9 26 1.84 0.97 17 2.96

24 Family not present with the child when she/he is dying 1.52 0.94 23 1.72 0.91 21 2.94

25 Physicians who are evasive and avoid having conversations with family members1.43 0.92 25 1.68 0.96 23 2.87

26 Dealing with the cultural differences that families use in grieving for their dying family member1.49 0.89 24 1.59 0.9 26 2.73

27 Physicians overly optimistic to family about the child surviving 1.39 0.86 27 1.57 0.93 28 2.52

28 Physicians differing in opinion about care of a child 1.39 0.7 28 1.58 0.88 27 2.51

29 Unit visiting hours that is too restrictive 1.3 0.93 29 1.46 0.99 29 2.25

30 Continuing to provide advanced treatments to dying children because of financial benefits to

hospital

1.15 0.91 30 1.43 1.01 30 2.19

Abbreviations:EOL,end of life;PBM,perceived barriers magnitude.

Iranmanesh et al 5

at UNIV OF FLORIDA on November 14, 2015ajh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

dying family member. The mean years of participants’ experi-

ences of caring for a dying member of family were 0.9 years.

All respondentswere Muslim and Shia. The majority

(97.4%) of participants stated that they always experienced the

existence of God in their daily living.Most (72.2%) of them

claimed that they performed religious activities daily.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine pediatric nurses’ per-

ceptions of intensity, frequency of occurrence, and magnitude

score of selected barriers in providing pediatric EOL care in

Southeast Iran.The firsthighestperceived barrier magnitude

score among all items was ‘‘families not accepting poor ch

prognosis.’’ Lack of family readiness to acknowledge an in

able condition is congruent with the results of earlier studi

where they found this item as one of the most frequent ba

to providing optimalEOL care.13,37,38

Understanding thata

child will die from an underlying illness is most likely multif

torial. Rowse39stated that in a death-denying society, childre

are viewed as being at the beginning of life and are expect

live long and healthy lives.39 This is highlighted more in the

Iranian context,while there is an intense family solidity and

bond, as well as strong emotional family relationship. Discu

sions of death and dying and even the mention of cancer a

still taboo in many countries in the Middle Eastdue to lack

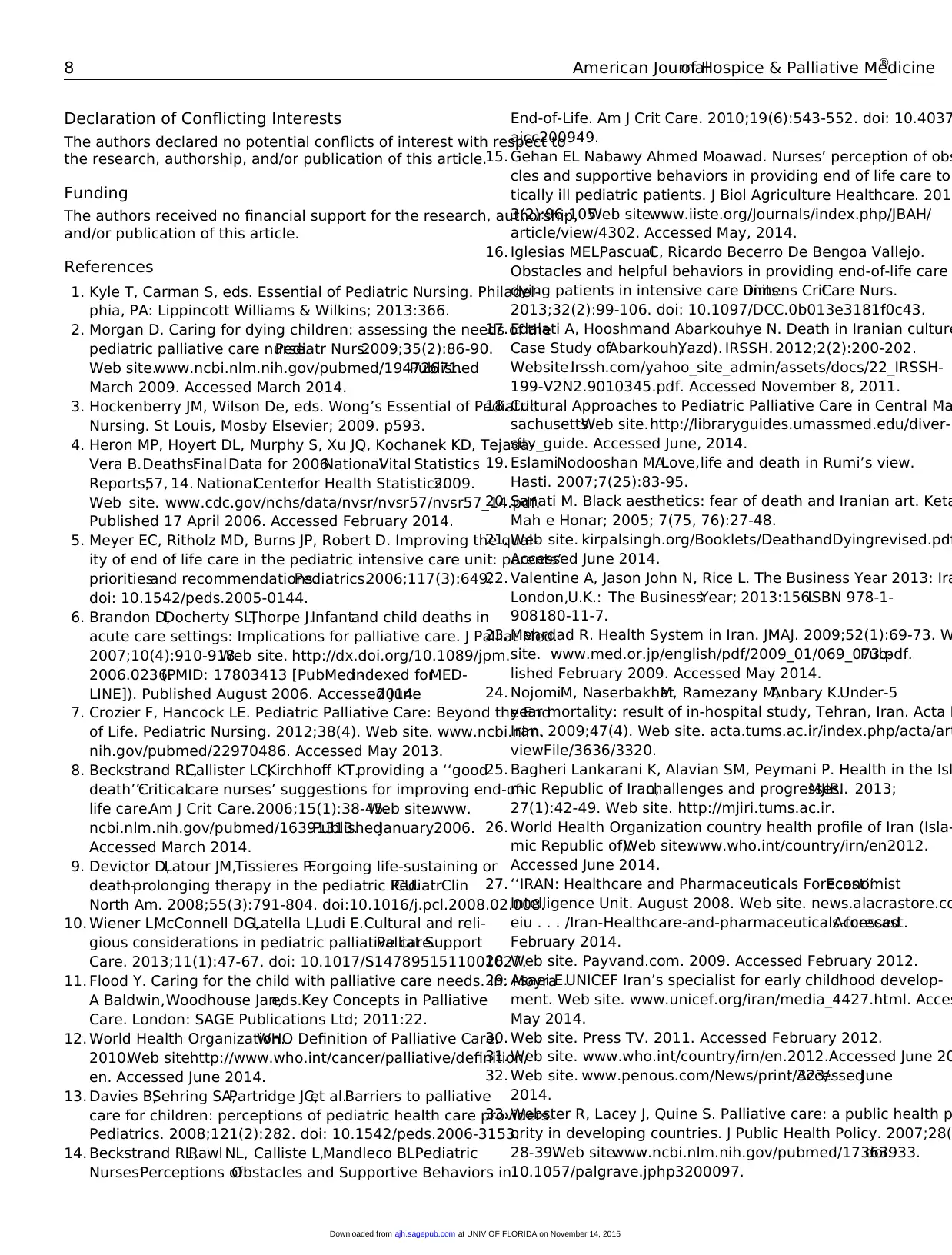

Table 3. Participants’Demographic Characteristics.a,b,c

Variable n % Variable n %

Age,years Ward

20-30 61 40.4 PICU 69 45.7

31-40 79 52.3 Pediatric oncology 43 28.5

41-50 9 6.00 Pediatric emergency 28 18.5

51-60 2 1.3 Pediatric general 11 7.3

Gender Dying children care experience

Male 2 1.3 Yes 151 100

Female 149 98.7 No 0 0

Marriage status Education

Married 121 80.1 Auxiliary nursing 20 13.2

Single 29 19.2 Bachelor of Science 124 82.1

Other (divorced,widow) 1 0.7 Master of Science and higher 7 4.6

Nursing experience,years Work hours per week

0.5-10 111 73.5 <30 hours per week 20 13.2

11-20 28 18.5 30-40 hours per week 61 40.4

21-30 11 7.3 >40 hours per week 70 46.4

31-40 1 0.7

Number of dying children cared for Dying family member care experience

<10 95 62.9 Yes 39 25.8

10-30 31 20.5 No 112 74.2

>30 25 19.6

Age range of dying children cared for (years) Duration of caring for a dying family member (years)

One year old or less 22 14.6 1-5 33 21.9

2-5 64 64.2 6-10 1 1.59

6-12 20 13.2 11-15 5 2.39

13-18 30 20.5 No 112 47.2

All ages 14 9.3

Family and closed friends’death experience PersonalEOL care education

Yes 54 35.8 Yes 34 22.5

No 97 64.2 No 11 77.5

Intrinsic religiosity Extrinsic religiosity

Always 147 97.4 Daily 109 72.2

Sometimes 4 2.6 A few times per week 22 14.6

Never 000 0.00 A few times per month 15 9.9

A few times per year 5 3.3

Never 000 0.00

Abbreviations:EOL,end of life;PICU,pediatric intensive care unit;PBM,perceived barriers magnitude;MIS,mean intensity score.

aDescriptive findings.

bPerceived barriers magnitude.

cThe PBM scores ranged from 5.04 to 2.19. The top perceived item was related to family issues. This item ‘‘families not accepting poor child

score (5.04). In addition, the highest MIS belonged to this item. The next 2 highest PBM score were no available support person for family su

(4.97) and poor design of units that do not allow for privacy of dying child or grieving family (4.96). The 3 lowest PBM scores barriers were c

advanced treatment to dying child because of financial benefits to the hospital (2.19); unit visiting hours are too restrictive (2.25); and phys

about care of a child (2.51) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

6 American Journalof Hospice & Palliative Medicine®

at UNIV OF FLORIDA on November 14, 2015ajh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

ences of caring for a dying member of family were 0.9 years.

All respondentswere Muslim and Shia. The majority

(97.4%) of participants stated that they always experienced the

existence of God in their daily living.Most (72.2%) of them

claimed that they performed religious activities daily.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine pediatric nurses’ per-

ceptions of intensity, frequency of occurrence, and magnitude

score of selected barriers in providing pediatric EOL care in

Southeast Iran.The firsthighestperceived barrier magnitude

score among all items was ‘‘families not accepting poor ch

prognosis.’’ Lack of family readiness to acknowledge an in

able condition is congruent with the results of earlier studi

where they found this item as one of the most frequent ba

to providing optimalEOL care.13,37,38

Understanding thata

child will die from an underlying illness is most likely multif

torial. Rowse39stated that in a death-denying society, childre

are viewed as being at the beginning of life and are expect

live long and healthy lives.39 This is highlighted more in the

Iranian context,while there is an intense family solidity and

bond, as well as strong emotional family relationship. Discu

sions of death and dying and even the mention of cancer a

still taboo in many countries in the Middle Eastdue to lack

Table 3. Participants’Demographic Characteristics.a,b,c

Variable n % Variable n %

Age,years Ward

20-30 61 40.4 PICU 69 45.7

31-40 79 52.3 Pediatric oncology 43 28.5

41-50 9 6.00 Pediatric emergency 28 18.5

51-60 2 1.3 Pediatric general 11 7.3

Gender Dying children care experience

Male 2 1.3 Yes 151 100

Female 149 98.7 No 0 0

Marriage status Education

Married 121 80.1 Auxiliary nursing 20 13.2

Single 29 19.2 Bachelor of Science 124 82.1

Other (divorced,widow) 1 0.7 Master of Science and higher 7 4.6

Nursing experience,years Work hours per week

0.5-10 111 73.5 <30 hours per week 20 13.2

11-20 28 18.5 30-40 hours per week 61 40.4

21-30 11 7.3 >40 hours per week 70 46.4

31-40 1 0.7

Number of dying children cared for Dying family member care experience

<10 95 62.9 Yes 39 25.8

10-30 31 20.5 No 112 74.2

>30 25 19.6

Age range of dying children cared for (years) Duration of caring for a dying family member (years)

One year old or less 22 14.6 1-5 33 21.9

2-5 64 64.2 6-10 1 1.59

6-12 20 13.2 11-15 5 2.39

13-18 30 20.5 No 112 47.2

All ages 14 9.3

Family and closed friends’death experience PersonalEOL care education

Yes 54 35.8 Yes 34 22.5

No 97 64.2 No 11 77.5

Intrinsic religiosity Extrinsic religiosity

Always 147 97.4 Daily 109 72.2

Sometimes 4 2.6 A few times per week 22 14.6

Never 000 0.00 A few times per month 15 9.9

A few times per year 5 3.3

Never 000 0.00

Abbreviations:EOL,end of life;PICU,pediatric intensive care unit;PBM,perceived barriers magnitude;MIS,mean intensity score.

aDescriptive findings.

bPerceived barriers magnitude.

cThe PBM scores ranged from 5.04 to 2.19. The top perceived item was related to family issues. This item ‘‘families not accepting poor child

score (5.04). In addition, the highest MIS belonged to this item. The next 2 highest PBM score were no available support person for family su

(4.97) and poor design of units that do not allow for privacy of dying child or grieving family (4.96). The 3 lowest PBM scores barriers were c

advanced treatment to dying child because of financial benefits to the hospital (2.19); unit visiting hours are too restrictive (2.25); and phys

about care of a child (2.51) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

6 American Journalof Hospice & Palliative Medicine®

at UNIV OF FLORIDA on November 14, 2015ajh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

of education and understanding.40 Iran represents mostreli-

gions with a majority of Islam. In Islam, a child is considered

to be a gift from Allah,41and parents are required to seek treat-

ment for their sick child and to follow the medical and nursing

suggestions relevantto the child’s care.42 Families wantto

have everything possible done for their dying family member

even when those treatments are unnecessary.43 Families not

accepting poorchild prognosis could also be related to the

uncertain prognosis and unrealistic expectation of technology

developments that makes parents to be overly optimistic about

the possibility of cure.13According to Graham and Robinson,44

parents’ hopes for recovery, boosted by miraculous recoveries

recounted in the media, entice them into believing that the see-

mingly ‘‘endless possibilities of medicine’s technologic pro-

wess’’ willsave their child.44 Moreover,denying this factis

a coping strategy forfamily to tolerate this greatgrief.As

Davies etal13 stated thatdenialcan be a powerfulcoping

mechanism, allowing parents the emotional energy to support

their child. The result ‘‘families not accepting poor child prog-

nosis’’ could also be related to the insufficientparticipants’

knowledge in the field ofPC. Based on the results,only

22.5% of the participants were educated about EOL care.As

mentioned before,participants had no PC education,which

may cause lack of appropriate communication skills to create

effective relationship with family.

The second reported high PBM score among allitems

was no ‘‘available supportperson for family such as a reli-

gious leader.’’Compared with earlierstudies,13-16,37,45

this

item gained a significant higher PBM score in the following

study (with a high MFS,2.40).The aforementioned studies

showed thatinterdisciplinary teams for EOL care are avail-

able.An interdisciplinary team,which consists of atleasta

nurse,physician,social worker,and a chaplain,is a corner-

stone to enhance the quality of EOL care.46 In the Iranian

context,as a religious country with majority ofMuslims,

there isno chaplain asa memberof an interdisciplinary

PC team at any age (from children to adult patients) to spiri-

tually supportpatients and their families.In Iran,chaplains

just are accessible after a person dies for consoling the fam-

ily and holding funeraland mourning ceremony.According

to Abedi,47 a cultural view of death as preventable only by a

divine entity highlights the significance ofspirituality and

hope associated with it as effective notions central to a sup-

portsystem for Iranian patients.47

The results revealed that ‘‘continuing to provide advanced

treatment to dying child because of financial benefits to hospi-

tal’’ has the first lowest PBM score among all items, which is in

agreementwith previous studies.15,37,45

Culture and religion

are 2 important factors thatmay contribute to the perception

of society about EOL issues.48 According to Shiite experts in

Islamic Sciences,life-prolonging treatments should notaim

at keeping the patients alive only to save their lives.They go

on thatin situationsthathas no cure,people can refuse

death-prolonging procedures including cardiopulmonary resus-

citation.49However, in Iran, a do not resuscitate (DNR) order is

not legally accepted.Iranian physicians are reluctant to write

such orders because there have been no published guideli

position papers,legislation,or officialstatements concerning

EOL care, making them fearful of legal problems and crimi

prosecution.50 Mogadasian et al51 reported that Iranian nurses

have negative attitudes toward DNR in many key items of

tudes of DNR questionnaire. This study highlighted that DN

laws and religious aspects of DNR in Islam may change the

attitudes of health care providers toward DNR orders.51 Chil-

dren are valued and respected in Islam as individuals with

inherentrights,and they have the rightto be treated with

respectand withoutviolence.52 When the child is notventi-

lated, but a decision of DNR or limiting vital support measu

is made,none has objections to limittherapy.53 Therefore,

based on the principle religious rules in the context hasten

or postponing death is forbidden,terminally ill patients cause

a large financial burden for health care services.

The findings indicated thatthe item ‘‘Unitvisiting hours

is too restrictive’’ has the second lowestPBM score among

all items.This is consistentwith the finding of earlier

research.54,55The restrictive visiting hours resultin several

disadvantages for EOL care.Restricting visiting hours iso-

late familiesfrom a dying child ata time when families

need to be close to theirloved ones.37 The culturalback-

ground of mostIslamic countries stresses aboutthe family

ties.Therefore,it is more the responsibility ofthe family

and close relatives and friends to provide the care in a ded

cated way.56 In the Iranian culture, patient may never be left

alone by family or friends.This facilitates family to be with

the dying child to provide happiness and a peacefulmind.

Nonrestrictive visiting hoursallow family membersto be

included in daily interdisciplinary rounds.Consequently,

nurses or other health care professionals have time to sha

criticalinformation with family members.57

Conclusion

Nurses in this study perceived that the most important bar

in pediatric EOL care are family issues.One of the possible

causes of this result mentioned in the discussion was lack

PC education and unit.Therefore,developing EOL and PC

education based on Islamic beliefs and Iranian culture may

enhance nurses’ knowledge and skill,which enable them to

face the challenges of EOL care.Providing some educational

programs for the families aboutdeath and dying,especially

about copying strategies,could be helpful.Establishing OPD

and PC units in the community, as well as developing pallia

home care programs that focus on family members who pl

important role in children’s care, may have a positive effec

children’s EOL care.Active involvementof chaplain and a

psychologist to the treatment team in order to provide spir

and psychological support for the family may strengthen E

care. This also reduces the unnecessary cost of hospitaliza

and extra medicalexamination costs forincurable patients.

Finally,expanding NGOs and charities such as ‘‘MAHAK’’

would be very helpful to diminish family economical and p

chological burden.

Iranmanesh et al 7

at UNIV OF FLORIDA on November 14, 2015ajh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

gions with a majority of Islam. In Islam, a child is considered

to be a gift from Allah,41and parents are required to seek treat-

ment for their sick child and to follow the medical and nursing

suggestions relevantto the child’s care.42 Families wantto

have everything possible done for their dying family member

even when those treatments are unnecessary.43 Families not

accepting poorchild prognosis could also be related to the

uncertain prognosis and unrealistic expectation of technology

developments that makes parents to be overly optimistic about

the possibility of cure.13According to Graham and Robinson,44

parents’ hopes for recovery, boosted by miraculous recoveries

recounted in the media, entice them into believing that the see-

mingly ‘‘endless possibilities of medicine’s technologic pro-

wess’’ willsave their child.44 Moreover,denying this factis

a coping strategy forfamily to tolerate this greatgrief.As

Davies etal13 stated thatdenialcan be a powerfulcoping

mechanism, allowing parents the emotional energy to support

their child. The result ‘‘families not accepting poor child prog-

nosis’’ could also be related to the insufficientparticipants’

knowledge in the field ofPC. Based on the results,only

22.5% of the participants were educated about EOL care.As

mentioned before,participants had no PC education,which

may cause lack of appropriate communication skills to create

effective relationship with family.

The second reported high PBM score among allitems

was no ‘‘available supportperson for family such as a reli-

gious leader.’’Compared with earlierstudies,13-16,37,45

this

item gained a significant higher PBM score in the following

study (with a high MFS,2.40).The aforementioned studies

showed thatinterdisciplinary teams for EOL care are avail-

able.An interdisciplinary team,which consists of atleasta

nurse,physician,social worker,and a chaplain,is a corner-

stone to enhance the quality of EOL care.46 In the Iranian

context,as a religious country with majority ofMuslims,

there isno chaplain asa memberof an interdisciplinary

PC team at any age (from children to adult patients) to spiri-

tually supportpatients and their families.In Iran,chaplains

just are accessible after a person dies for consoling the fam-

ily and holding funeraland mourning ceremony.According

to Abedi,47 a cultural view of death as preventable only by a

divine entity highlights the significance ofspirituality and

hope associated with it as effective notions central to a sup-

portsystem for Iranian patients.47

The results revealed that ‘‘continuing to provide advanced

treatment to dying child because of financial benefits to hospi-

tal’’ has the first lowest PBM score among all items, which is in

agreementwith previous studies.15,37,45

Culture and religion

are 2 important factors thatmay contribute to the perception

of society about EOL issues.48 According to Shiite experts in

Islamic Sciences,life-prolonging treatments should notaim

at keeping the patients alive only to save their lives.They go

on thatin situationsthathas no cure,people can refuse

death-prolonging procedures including cardiopulmonary resus-

citation.49However, in Iran, a do not resuscitate (DNR) order is

not legally accepted.Iranian physicians are reluctant to write

such orders because there have been no published guideli

position papers,legislation,or officialstatements concerning

EOL care, making them fearful of legal problems and crimi

prosecution.50 Mogadasian et al51 reported that Iranian nurses

have negative attitudes toward DNR in many key items of

tudes of DNR questionnaire. This study highlighted that DN

laws and religious aspects of DNR in Islam may change the

attitudes of health care providers toward DNR orders.51 Chil-

dren are valued and respected in Islam as individuals with

inherentrights,and they have the rightto be treated with

respectand withoutviolence.52 When the child is notventi-

lated, but a decision of DNR or limiting vital support measu

is made,none has objections to limittherapy.53 Therefore,

based on the principle religious rules in the context hasten

or postponing death is forbidden,terminally ill patients cause

a large financial burden for health care services.

The findings indicated thatthe item ‘‘Unitvisiting hours

is too restrictive’’ has the second lowestPBM score among

all items.This is consistentwith the finding of earlier

research.54,55The restrictive visiting hours resultin several

disadvantages for EOL care.Restricting visiting hours iso-

late familiesfrom a dying child ata time when families

need to be close to theirloved ones.37 The culturalback-

ground of mostIslamic countries stresses aboutthe family

ties.Therefore,it is more the responsibility ofthe family

and close relatives and friends to provide the care in a ded

cated way.56 In the Iranian culture, patient may never be left

alone by family or friends.This facilitates family to be with

the dying child to provide happiness and a peacefulmind.

Nonrestrictive visiting hoursallow family membersto be

included in daily interdisciplinary rounds.Consequently,

nurses or other health care professionals have time to sha

criticalinformation with family members.57

Conclusion

Nurses in this study perceived that the most important bar

in pediatric EOL care are family issues.One of the possible

causes of this result mentioned in the discussion was lack

PC education and unit.Therefore,developing EOL and PC

education based on Islamic beliefs and Iranian culture may

enhance nurses’ knowledge and skill,which enable them to

face the challenges of EOL care.Providing some educational

programs for the families aboutdeath and dying,especially

about copying strategies,could be helpful.Establishing OPD

and PC units in the community, as well as developing pallia

home care programs that focus on family members who pl

important role in children’s care, may have a positive effec

children’s EOL care.Active involvementof chaplain and a

psychologist to the treatment team in order to provide spir

and psychological support for the family may strengthen E

care. This also reduces the unnecessary cost of hospitaliza

and extra medicalexamination costs forincurable patients.

Finally,expanding NGOs and charities such as ‘‘MAHAK’’

would be very helpful to diminish family economical and p

chological burden.

Iranmanesh et al 7

at UNIV OF FLORIDA on November 14, 2015ajh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to

the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship,

and/or publication of this article.

References

1. Kyle T, Carman S, eds. Essential of Pediatric Nursing. Philadel-

phia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013:366.

2. Morgan D. Caring for dying children: assessing the needs of the

pediatric palliative care nurse.Pediatr Nurs.2009;35(2):86-90.

Web site.www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19472671.Published

March 2009. Accessed March 2014.

3. Hockenberry JM, Wilson De, eds. Wong’s Essential of Pediatric

Nursing. St Louis, Mosby Elsevier; 2009. p593.

4. Heron MP, Hoyert DL, Murphy S, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD, Tejada-

Vera B.Deaths:FinalData for 2006.NationalVital Statistics

Reports,57, 14. NationalCenterfor Health Statistics.2009.

Web site. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr57/nvsr57_14.pdf.

Published 17 April 2006. Accessed February 2014.

5. Meyer EC, Ritholz MD, Burns JP, Robert D. Improving the qual-

ity of end of life care in the pediatric intensive care unit: parents’

prioritiesand recommendations.Pediatrics.2006;117(3):649.

doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0144.

6. Brandon D,Docherty SL,Thorpe J.Infantand child deaths in

acute care settings: Implications for palliative care. J Palliat Med.

2007;10(4):910-918.Web site. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/jpm.

2006.0236.(PMID: 17803413 [PubMed -indexed forMED-

LINE]). Published August 2006. Accessed June2014.

7. Crozier F, Hancock LE. Pediatric Palliative Care: Beyond the End

of Life. Pediatric Nursing. 2012;38(4). Web site. www.ncbi.nlm.

nih.gov/pubmed/22970486. Accessed May 2013.

8. Beckstrand RL,Callister LC,Kirchhoff KT.providing a ‘‘good

death’’:Criticalcare nurses’ suggestions for improving end-of-

life care.Am J Crit Care.2006;15(1):38-45.Web site.www.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16391313.PublishedJanuary2006.

Accessed March 2014.

9. Devictor D,Latour JM,Tissieres P.Forgoing life-sustaining or

death-prolonging therapy in the pediatric ICU.PediatrClin

North Am. 2008;55(3):791-804. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2008.02.008.

10. Wiener L,McConnell DG,Latella L,Ludi E.Cultural and reli-

gious considerations in pediatric palliative care.Palliat Support

Care. 2013;11(1):47-67. doi: 10.1017/S1478951511001027.

11. Flood Y. Caring for the child with palliative care needs. In: Moyra

A Baldwin,Woodhouse Jan,eds.Key Concepts in Palliative

Care. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2011:22.

12. World Health Organization.WHO Definition of Palliative Care.

2010.Web site.http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/

en. Accessed June 2014.

13. Davies B,Sehring SA,Partridge JC,et al.Barriers to palliative

care for children: perceptions of pediatric health care providers.

Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):282. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3153.

14. Beckstrand RL,Rawl NL, Calliste L,Mandleco BL.Pediatric

Nurses’Perceptions ofObstacles and Supportive Behaviors in

End-of-Life. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19(6):543-552. doi: 10.4037

ajcc200949.

15. Gehan EL Nabawy Ahmed Moawad. Nurses’ perception of obs

cles and supportive behaviors in providing end of life care to