Systematic Review: Nursing Resources and Patient Outcomes in ICUs

VerifiedAdded on 2023/03/20

|19

|13553

|52

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a systematic review of the literature on the impact of nursing resources on patient outcomes in intensive care units (ICUs). The review, published in the International Journal of Nursing Studies, examines 15 studies to evaluate the relationship between nursing resources (nurse-patient ratios, nurses' education, training, and experience) and patient outcomes, including mortality and adverse events. The findings reveal that some studies found a statistical relationship between nursing resources and both mortality and adverse events, while others reported associations with mortality only or found no significant relationship. The review highlights the methodological challenges in this area, including the observational and retrospective nature of many studies, and suggests the need for future research, including multi-center prospective studies. The main explanatory mechanisms were the lack of time for nurses to perform preventative measures, or for patient surveillance.

Review

Nursing resources and patient outcomes in intensive car

A systematic review of the literature

Elizabeth Westa,*, Nicholas Maysb, Anne Marie Raffertyc,

Kathy Rowand, Colin Sandersonb

aSchool of Health and Social Care,University of Greenwich,Southwood Site,Avery Hill Road,Eltham, London SE9 2UG,UK

bLondon School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street,London WC1E 7HT,UK

c Florence Nightingale School of Nursing and Midwifery,King’s College London,James Clerk Maxwell Building,

57 Waterloo Road, London SE1 8WA,UK

dIntensive Care National Audit and Research Centre,Tavistock House,Tavistock Square,London WC1H 9HR,USA

Received 7 November 2006; received in revised form 25 May 2007; accepted 3 July 2007

Abstract

Objectives:To evaluate the empirical evidence linking nursing resources to patient outcomes in intensive care se

framework for future research in this area.

Background:Concerns about patient safety and the quality of care are driving research on the clinical and cost-e

health care interventions, including the deployment of human resources. This is particularly important in intens

large proportion of the health care budget is consumed and where nursing staff is the main item of expenditure

tions about staffing levels have been made but may not be evidence based and may not always be achieved in

Methods:We searched systematically for studies of the impact of nursing resources (e.g. nurse–patient ratios, n

education,training and experience) on patientoutcomes,including mortality and adverse events,in adultintensive care.

Abstracts of articles were reviewed and retrieved if they investigated the relationship between nursing resourc

outcomes.Characteristics of the studies were tabulated and the quality of the studies assessed.

Results:Of the 15 studies included in this review, two reported a statistical relationship between nursing resourc

mortality and adverse events, one reported an association to mortality only, seven studies reported that they c

null hypothesis of no relationship to mortality and 10 studies (out of 10 that tested the hypothesis) reported a r

adverse events. The main explanatory mechanisms were the lack of time for nurses to perform preventative m

patientsurveillance.The nurses’ role in pain controlwas noted by one author.Studies were mainly observationaland

retrospective and varied in scope from 1 to 52 units. Recommendations for future research include developing

linking nursing resources to patient outcomes, and designing large multi-centre prospective studies that link pa

nursing care on a shift-by-shift basis over time.

# 2007 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

Keywords:Nursing; Outcomes assessment; Hospital mortality; Complications; Intensive care; Health services research

What is already known about the topic?

A previous systematic review concluded thatthere is

currently insufficientevidence to rejectthe hypothesis

www.elsevier.com/ijns

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

International Journal of Nursing Studies 46 (2009) 993–1011

* Corresponding author.Tel.: +44 1865 512 938.

E-mail address: Lizwestbarron@googlemail.com (E.West).

0020-7489/$ – see front matter # 2007 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.07.011

Nursing resources and patient outcomes in intensive car

A systematic review of the literature

Elizabeth Westa,*, Nicholas Maysb, Anne Marie Raffertyc,

Kathy Rowand, Colin Sandersonb

aSchool of Health and Social Care,University of Greenwich,Southwood Site,Avery Hill Road,Eltham, London SE9 2UG,UK

bLondon School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street,London WC1E 7HT,UK

c Florence Nightingale School of Nursing and Midwifery,King’s College London,James Clerk Maxwell Building,

57 Waterloo Road, London SE1 8WA,UK

dIntensive Care National Audit and Research Centre,Tavistock House,Tavistock Square,London WC1H 9HR,USA

Received 7 November 2006; received in revised form 25 May 2007; accepted 3 July 2007

Abstract

Objectives:To evaluate the empirical evidence linking nursing resources to patient outcomes in intensive care se

framework for future research in this area.

Background:Concerns about patient safety and the quality of care are driving research on the clinical and cost-e

health care interventions, including the deployment of human resources. This is particularly important in intens

large proportion of the health care budget is consumed and where nursing staff is the main item of expenditure

tions about staffing levels have been made but may not be evidence based and may not always be achieved in

Methods:We searched systematically for studies of the impact of nursing resources (e.g. nurse–patient ratios, n

education,training and experience) on patientoutcomes,including mortality and adverse events,in adultintensive care.

Abstracts of articles were reviewed and retrieved if they investigated the relationship between nursing resourc

outcomes.Characteristics of the studies were tabulated and the quality of the studies assessed.

Results:Of the 15 studies included in this review, two reported a statistical relationship between nursing resourc

mortality and adverse events, one reported an association to mortality only, seven studies reported that they c

null hypothesis of no relationship to mortality and 10 studies (out of 10 that tested the hypothesis) reported a r

adverse events. The main explanatory mechanisms were the lack of time for nurses to perform preventative m

patientsurveillance.The nurses’ role in pain controlwas noted by one author.Studies were mainly observationaland

retrospective and varied in scope from 1 to 52 units. Recommendations for future research include developing

linking nursing resources to patient outcomes, and designing large multi-centre prospective studies that link pa

nursing care on a shift-by-shift basis over time.

# 2007 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

Keywords:Nursing; Outcomes assessment; Hospital mortality; Complications; Intensive care; Health services research

What is already known about the topic?

A previous systematic review concluded thatthere is

currently insufficientevidence to rejectthe hypothesis

www.elsevier.com/ijns

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

International Journal of Nursing Studies 46 (2009) 993–1011

* Corresponding author.Tel.: +44 1865 512 938.

E-mail address: Lizwestbarron@googlemail.com (E.West).

0020-7489/$ – see front matter # 2007 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.07.011

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

of no association between nursing resources and mortality

in intensive care.

Several non-systematic reviews suggest that there may be

a link between nurse staffing and the developmentof

adverse events among patients in intensive care.

There are many methodologicaldifficulties to be over-

come in conducting research in this area.

What this paper adds?

This paper describes and critiques studies of the impact of

nursing resources on mortality and adverse events in one

systematic review.

Focuses attention on the methods used and devises a way

of assessing the scientific rigour of observational studies

which are notoriously difficult to evaluate.

Finds that studies of adverse events in ICU were likely to

report significant relationships between staffing and out-

comes butthatthe number of positive associations was

small relative to the number of hypothesised relationships

tested.

Links study findings to features of research design.The

three studies thatfound a relationship between nursing

and mortality were small prospective studies whereas the

seven studies that found no association were large multi-

unit studies based on administrative data.

Shows that several studies that failed to reject the hypoth-

esis ofno association between staffing levels and out-

comes had little variation in staffing levels.

1. Introduction

Historians of criticalcare nursing trace its origins to

the increasing demand for health care in the 1950s and to

the invention of the ‘iron lung,’ a precursor of the modern

ventilator (Reis Miranda etal., 1998;Bennettand Bion,

1999;Fairman and Lynaugh,1998).Intensive care units

(ICUs) were notdesigned simply to care forthe most

seriously ill, but for those for whom survival was possible,

but not certain. Patients admitted to intensive care were to

be closely observed by skilled nurses capable ofinter-

vening clinically and of mobilising the resources of the

hospitalon their behalf.Although intensive care is often

associated with high technology,this can obscurethe

importance ofthe two cardinalorganisationalfeatures

of intensive care:triage and surveillance (Fairman and

Lynaugh,1998;Sandelowski,2000).Advances in tech-

nology are tools to support staff in monitoring and treating

patients who are critically ill,rather than a substitute for

skilled health care staff (Sandelowski,2000;Westet al.,

2004).

For many, intensive care is central to the activities of the

hospital because its function is so clearly aligned with the

main goalof saving lives.Clinicians and managers have

often maintained staffing levels in ICU by,for example,

closing beds in other parts of the hospital, transferring staff

from other parts of the hospital or employing agency nur

(DoH, 2000a).Recommendations aboutstaffing in ICUs

have been in place since the late 1960s in the UK and the

‘gold standard’ of one nurse to each ICU patient is widely

accepted (British Medical Association, 1967; Royal Colleg

of Nursing, 2000, 2003). However, there is now a great d

of uncertainty and debate aboutthe levels of staffing and

skill mix that are required for patient safety.

Criticalto Success,a reportby the AuditCommission

(1999), found wide variations in the numbers and grades

staff employed in ICUs in the UK and in the number of

nurses who were supernumerary (i.e. not engaged in dire

patient care). They also found that mortality was unexpec

edly high in some UK ICUs,but they were unable to

establish whether or not this was linked to different staffi

levels. The report recommended a more flexible approach

nurse staffing but this is difficult to implement in the abse

of good measuresof staffresources,patientneedsand

outcomes.There isclearly a need forsound empirical

evidence to guide decisions about the deploymentof staff

to ensure patientsafety and improve both the quality and

cost-effectiveness of care.

2. Purpose of the study

This paper reviews empiricalevidence aboutthe link

between nursing resources and patient outcomes in inten

sive care,assessesits strengthsand weaknesses,and

identifies where furtherresearch is required.The focus

is on whetherand to whatextentcharacteristics ofthe

nursing workforce,such asthe numberof nursesper

patient and the skill mix of the nursing staff,affect rates

of mortality and adverse events,such as post-operative

complications and hospital-acquired infections.Although

there is a burgeoning literature on organisational behavio

in intensive care, including topics such as, communicatio

and collaboration within teams,we focuson variables

associated with the conceptof human capital(Becker,

1964),in this case,the number of nurses and their levels

of education,training and experience.Limiting the scope

of the review in this way allows closerscrutiny ofthe

quality of papers included. This is important because man

of the studies in this area are observationalratherthan

experimental,and as such arenotoriously difficultto

evaluate (Downs and Black,1998).

Much is already known about the importance of medic

staff in intensive care.Pronovost et al. (2002) reviewed 26

observational studies of the impact of ICU physician staffi

patterns on patient outcomes and concluded that high in

sity physician staffing (a closed ICU or one where consult

tion with an intensivist is mandatory) was associated with

reduced hospital and ICU mortality and length of stay. Th

research question addressed here is whetherthere is any

evidence that patterns of nurse staffing are similarly imp

cated in patient outcomes.

E. West et al. / International Journal of Nursing Studies 46 (2009) 993–1011994

in intensive care.

Several non-systematic reviews suggest that there may be

a link between nurse staffing and the developmentof

adverse events among patients in intensive care.

There are many methodologicaldifficulties to be over-

come in conducting research in this area.

What this paper adds?

This paper describes and critiques studies of the impact of

nursing resources on mortality and adverse events in one

systematic review.

Focuses attention on the methods used and devises a way

of assessing the scientific rigour of observational studies

which are notoriously difficult to evaluate.

Finds that studies of adverse events in ICU were likely to

report significant relationships between staffing and out-

comes butthatthe number of positive associations was

small relative to the number of hypothesised relationships

tested.

Links study findings to features of research design.The

three studies thatfound a relationship between nursing

and mortality were small prospective studies whereas the

seven studies that found no association were large multi-

unit studies based on administrative data.

Shows that several studies that failed to reject the hypoth-

esis ofno association between staffing levels and out-

comes had little variation in staffing levels.

1. Introduction

Historians of criticalcare nursing trace its origins to

the increasing demand for health care in the 1950s and to

the invention of the ‘iron lung,’ a precursor of the modern

ventilator (Reis Miranda etal., 1998;Bennettand Bion,

1999;Fairman and Lynaugh,1998).Intensive care units

(ICUs) were notdesigned simply to care forthe most

seriously ill, but for those for whom survival was possible,

but not certain. Patients admitted to intensive care were to

be closely observed by skilled nurses capable ofinter-

vening clinically and of mobilising the resources of the

hospitalon their behalf.Although intensive care is often

associated with high technology,this can obscurethe

importance ofthe two cardinalorganisationalfeatures

of intensive care:triage and surveillance (Fairman and

Lynaugh,1998;Sandelowski,2000).Advances in tech-

nology are tools to support staff in monitoring and treating

patients who are critically ill,rather than a substitute for

skilled health care staff (Sandelowski,2000;Westet al.,

2004).

For many, intensive care is central to the activities of the

hospital because its function is so clearly aligned with the

main goalof saving lives.Clinicians and managers have

often maintained staffing levels in ICU by,for example,

closing beds in other parts of the hospital, transferring staff

from other parts of the hospital or employing agency nur

(DoH, 2000a).Recommendations aboutstaffing in ICUs

have been in place since the late 1960s in the UK and the

‘gold standard’ of one nurse to each ICU patient is widely

accepted (British Medical Association, 1967; Royal Colleg

of Nursing, 2000, 2003). However, there is now a great d

of uncertainty and debate aboutthe levels of staffing and

skill mix that are required for patient safety.

Criticalto Success,a reportby the AuditCommission

(1999), found wide variations in the numbers and grades

staff employed in ICUs in the UK and in the number of

nurses who were supernumerary (i.e. not engaged in dire

patient care). They also found that mortality was unexpec

edly high in some UK ICUs,but they were unable to

establish whether or not this was linked to different staffi

levels. The report recommended a more flexible approach

nurse staffing but this is difficult to implement in the abse

of good measuresof staffresources,patientneedsand

outcomes.There isclearly a need forsound empirical

evidence to guide decisions about the deploymentof staff

to ensure patientsafety and improve both the quality and

cost-effectiveness of care.

2. Purpose of the study

This paper reviews empiricalevidence aboutthe link

between nursing resources and patient outcomes in inten

sive care,assessesits strengthsand weaknesses,and

identifies where furtherresearch is required.The focus

is on whetherand to whatextentcharacteristics ofthe

nursing workforce,such asthe numberof nursesper

patient and the skill mix of the nursing staff,affect rates

of mortality and adverse events,such as post-operative

complications and hospital-acquired infections.Although

there is a burgeoning literature on organisational behavio

in intensive care, including topics such as, communicatio

and collaboration within teams,we focuson variables

associated with the conceptof human capital(Becker,

1964),in this case,the number of nurses and their levels

of education,training and experience.Limiting the scope

of the review in this way allows closerscrutiny ofthe

quality of papers included. This is important because man

of the studies in this area are observationalratherthan

experimental,and as such arenotoriously difficultto

evaluate (Downs and Black,1998).

Much is already known about the importance of medic

staff in intensive care.Pronovost et al. (2002) reviewed 26

observational studies of the impact of ICU physician staffi

patterns on patient outcomes and concluded that high in

sity physician staffing (a closed ICU or one where consult

tion with an intensivist is mandatory) was associated with

reduced hospital and ICU mortality and length of stay. Th

research question addressed here is whetherthere is any

evidence that patterns of nurse staffing are similarly imp

cated in patient outcomes.

E. West et al. / International Journal of Nursing Studies 46 (2009) 993–1011994

3. Methods

3.1.Search strategy

Previous authors have drawn attention to the difficulties

of defining standard search terms in this area.Pronovost

et al. (2002), for example, reported that their comprehensive

search for empirical evidence on physician staffing patterns

did not uncover some of their own work. Carmel and Rowan

(2001) note that their review of the literature on organisa-

tional factors related to patient mortality was hampered by

the fact that electronic databases tend to adopt a biomedical-

intervention perspective. We therefore used many different

terms and strategies to try to ensure thatthe search for

relevant articles was as complete as possible:

Unit labels intensive care units; intensive care; surgical

intensive care; critical care; high dependency;

open,closed,critically ill

Outcomes outcome assessment, treatment outcomes,

mortality,morbidity,adverse events,infections,

length of stay,complications,error/s,

readmission/s,admission/s

Nursing nursing staff,hospital staffing

Workforce labour force,health care workforce,manpower,

workforce policy,training,education,nurse/s,

number,size,staffing levels,ratio/s, skill mix,

substitution, specialisation,training,education,

grade/s, staff development, human resources, HR

management, personnel staffing and scheduling

Workload volume of activity,workload

Methods multi-level modelling, case mix adjustment, risk

adjustment, APACHE, SAPS, case-control study,

retrospective study

The ‘related articles’feature in Pubmed was used in

locating studies, as was Google Scholar. The bibliographies

of articles retrieved atthe beginning ofthe search were

scanned for new references.

3.2.Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they were conducted exclusively

in intensive or critical care settings and allowed data on one or

more of the nursing workforce variables to be related to data

on mortality or adverse events.Studies conducted in acute

medical and surgical units or in neonatal or paediatric inten-

sive care were excluded because these settings are so different

that they warrant separate reviews. Single-unit studies were

included. Only studies published in English in refereed jour-

nals between 1990 and 2006 were included. The only quality

criterion that was used to selected studies was that they had to

have employed some method of risk adjustment. In summary,

studies were included if they met the following criteria:

Conducted exclusively in one or more adult ICUs

Dependent variable was mortality or adverse events

Human capitalcharacteristics of the nursing workforce

formed at least one of the independent variables

Published in English between 1990 and 2006

Used some form of risk adjustment

The first author read all the abstracts and retrieved all t

articles that in her judgement met these criteria.

3.3.Previous reviews

Several reviews have already been conducted in this ar

Carmel and Rowan (2001) found in 63 publications about 5

different studies of the organisation of intensive care, whic

they grouped into eightcategories:staffing,teamwork,

volume and pressure of work, protocols, admission to inte

sive care, technology, structure and error. Articles on staffi

were the most common and fell into a number of different

strands of research on management and personnel, intens

vist-led units,medicaland nursing intensity and nursing

autonomy.Five studies focussed on the impactof nursing

intensity (mainly nurse–patientratios,butone study also

examined levelof nurse qualifications)on mortality,but

none were able to rejectthe hypothesis of no association.

This was a usefulsource ofinformation aboutstudies

published prior to 2000.

Numata etal. (2006) reviewed the literature on nurse–

patientratiosand mortality in ICUsand identified nine

observationalstudies,five of which were included in a

meta-analysis.The unadjusted risk ratios of nurse staffing

(high versus low) on hospitalmortality were combined to

give a pooled estimate of 0.65 (95% CI 0.47–0.91).How-

ever,after adjusting for covariates the association between

staffing and mortality became non-significant in all but on

study (Tarnow-Mordiet al., 2000).Numata etal. (2006)

acknowledged that their meta-analysis was based on a sm

number of studies, four of which were conducted in the sa

region of the United States. They concluded that there wa

insufficient evidence to support an independent associatio

between nurses staffing levels and the mortality of critical

ill patients.They identified arangeof methodological

challenges: lack of an agreed operational definition of nurs

staffing, lack of variation in staffing levels in some studies

staffing levels which varied from shift-to-shift measured at

one pointin time,confounding factorsnot included or

controlled in any way,failure to use statisticalmethods

appropriate for the research design,crude methods of risk

adjustment due to the use of administrative databases and

tendency to analyse hospital mortality without considering

the care that the patient received outside the unit.

Both of the above reviews focussed on mortality as the

key variable to be explained, but there is a growing literat

on the impact of nursing on a much broader range of patie

outcomes,including safety,adverse events and complica-

tions, as well as patients’ and relatives’ satisfaction with c

and their subjective experiences of it. Williams et al. (2003

conducted a rapid review of different aspects of workload

E. West et al. / International Journal of Nursing Studies 46 (2009) 993–1011 995

3.1.Search strategy

Previous authors have drawn attention to the difficulties

of defining standard search terms in this area.Pronovost

et al. (2002), for example, reported that their comprehensive

search for empirical evidence on physician staffing patterns

did not uncover some of their own work. Carmel and Rowan

(2001) note that their review of the literature on organisa-

tional factors related to patient mortality was hampered by

the fact that electronic databases tend to adopt a biomedical-

intervention perspective. We therefore used many different

terms and strategies to try to ensure thatthe search for

relevant articles was as complete as possible:

Unit labels intensive care units; intensive care; surgical

intensive care; critical care; high dependency;

open,closed,critically ill

Outcomes outcome assessment, treatment outcomes,

mortality,morbidity,adverse events,infections,

length of stay,complications,error/s,

readmission/s,admission/s

Nursing nursing staff,hospital staffing

Workforce labour force,health care workforce,manpower,

workforce policy,training,education,nurse/s,

number,size,staffing levels,ratio/s, skill mix,

substitution, specialisation,training,education,

grade/s, staff development, human resources, HR

management, personnel staffing and scheduling

Workload volume of activity,workload

Methods multi-level modelling, case mix adjustment, risk

adjustment, APACHE, SAPS, case-control study,

retrospective study

The ‘related articles’feature in Pubmed was used in

locating studies, as was Google Scholar. The bibliographies

of articles retrieved atthe beginning ofthe search were

scanned for new references.

3.2.Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they were conducted exclusively

in intensive or critical care settings and allowed data on one or

more of the nursing workforce variables to be related to data

on mortality or adverse events.Studies conducted in acute

medical and surgical units or in neonatal or paediatric inten-

sive care were excluded because these settings are so different

that they warrant separate reviews. Single-unit studies were

included. Only studies published in English in refereed jour-

nals between 1990 and 2006 were included. The only quality

criterion that was used to selected studies was that they had to

have employed some method of risk adjustment. In summary,

studies were included if they met the following criteria:

Conducted exclusively in one or more adult ICUs

Dependent variable was mortality or adverse events

Human capitalcharacteristics of the nursing workforce

formed at least one of the independent variables

Published in English between 1990 and 2006

Used some form of risk adjustment

The first author read all the abstracts and retrieved all t

articles that in her judgement met these criteria.

3.3.Previous reviews

Several reviews have already been conducted in this ar

Carmel and Rowan (2001) found in 63 publications about 5

different studies of the organisation of intensive care, whic

they grouped into eightcategories:staffing,teamwork,

volume and pressure of work, protocols, admission to inte

sive care, technology, structure and error. Articles on staffi

were the most common and fell into a number of different

strands of research on management and personnel, intens

vist-led units,medicaland nursing intensity and nursing

autonomy.Five studies focussed on the impactof nursing

intensity (mainly nurse–patientratios,butone study also

examined levelof nurse qualifications)on mortality,but

none were able to rejectthe hypothesis of no association.

This was a usefulsource ofinformation aboutstudies

published prior to 2000.

Numata etal. (2006) reviewed the literature on nurse–

patientratiosand mortality in ICUsand identified nine

observationalstudies,five of which were included in a

meta-analysis.The unadjusted risk ratios of nurse staffing

(high versus low) on hospitalmortality were combined to

give a pooled estimate of 0.65 (95% CI 0.47–0.91).How-

ever,after adjusting for covariates the association between

staffing and mortality became non-significant in all but on

study (Tarnow-Mordiet al., 2000).Numata etal. (2006)

acknowledged that their meta-analysis was based on a sm

number of studies, four of which were conducted in the sa

region of the United States. They concluded that there wa

insufficient evidence to support an independent associatio

between nurses staffing levels and the mortality of critical

ill patients.They identified arangeof methodological

challenges: lack of an agreed operational definition of nurs

staffing, lack of variation in staffing levels in some studies

staffing levels which varied from shift-to-shift measured at

one pointin time,confounding factorsnot included or

controlled in any way,failure to use statisticalmethods

appropriate for the research design,crude methods of risk

adjustment due to the use of administrative databases and

tendency to analyse hospital mortality without considering

the care that the patient received outside the unit.

Both of the above reviews focussed on mortality as the

key variable to be explained, but there is a growing literat

on the impact of nursing on a much broader range of patie

outcomes,including safety,adverse events and complica-

tions, as well as patients’ and relatives’ satisfaction with c

and their subjective experiences of it. Williams et al. (2003

conducted a rapid review of different aspects of workload

E. West et al. / International Journal of Nursing Studies 46 (2009) 993–1011 995

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ICUs, including the policy context and secular trends. They

identified 12 studies of nurse staffing,and presented evi-

dence for a positive effectof increased nurse staffing on

patient outcomes. More recently, Carayon and Gurses (2005)

conducted a wide ranging review ofthe literature.Their

main goalwas to devise a ‘human factorsengineering’

framework to guide modification ofthe work setting to

improve patient safety and to improve the quality of nurses’

work lives in ICUs. They cite several studies that have shown

thatmedicalerrorsare common in ICUsand may be

attributable to problems in communication between nurses

and physicians,to impaired access to information,and to

high intensity nursing workloads. They identified 22 studies

in all,but made no attempt to evaluate them or aggregate

their findings. They concluded that there were at least four

differentkinds of workload associated with the unit,job,

patient and situation. Most studies to date have focussed on

workload associated with the first two: the unit or the patient.

Each of the above reviewsmakesa contribution to

knowledge aboutworkforce,workload and outcomesin

intensive care.The emerging consensus seems to be that

while there is some evidence that the nursing workforce has

an impacton patients’risksof adverse events,there is

insufficient evidence of a link with mortality. This presents

a puzzle because some of the adverse events studied have

known links to mortality.Why would nursing workforce

characteristics affect the more proximate events but not the

final outcome? The process of dying is likely to be one of an

accumulation of adverse events as the patientdeteriorates

and clinicians take increasing risks in an attempt to save their

life. It seems important then to begin to integrate these two

separate strands of work into one coherent analysis.

This study uses systematic review methods to identify

and appraise empiricalevidence aboutthe impactof any

human capital characteristic of the nursing workforce (such

as skill mix, education or employments status, in addition to

nurse–patient ratios) on any patient outcomes,particularly

adverse events such as post-operative infections and mor-

tality.It adds to the literature a deeper description of the

methodsused and attemptsto evaluate the quality and

scientific rigour of the studies reviewed.

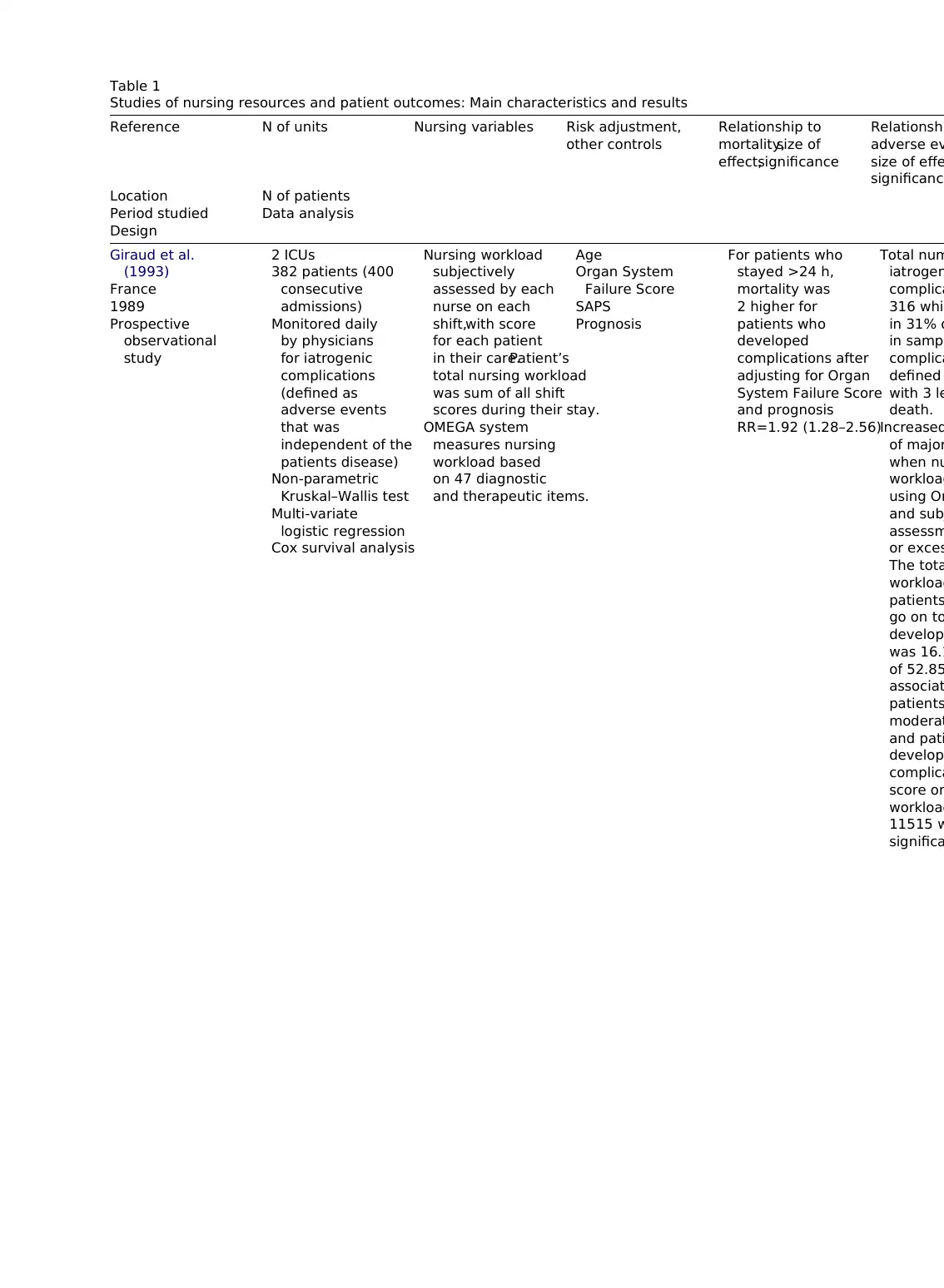

4. Results of the literature search

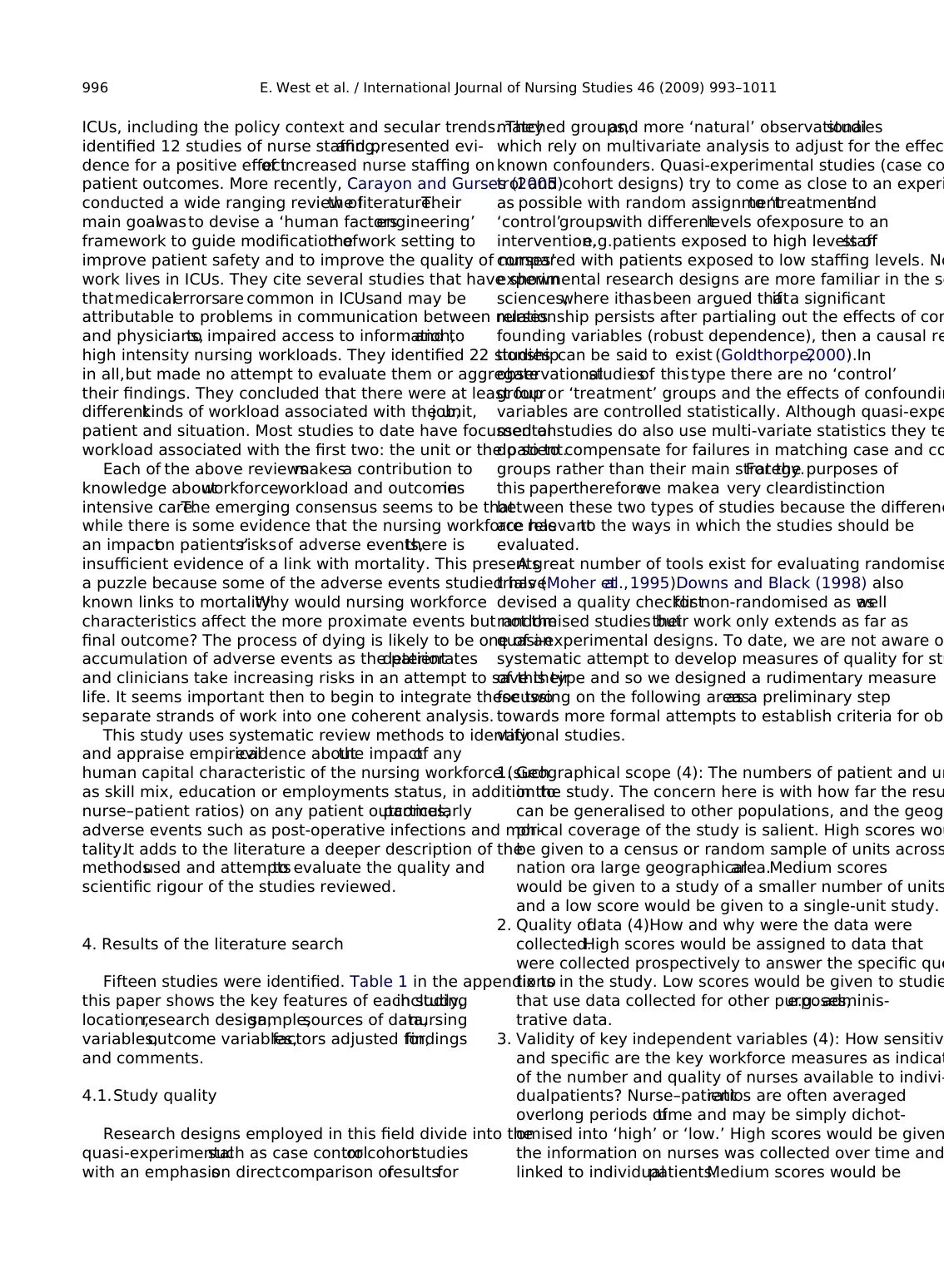

Fifteen studies were identified. Table 1 in the appendix to

this paper shows the key features of each study,including

location,research design,sample,sources of data,nursing

variables,outcome variables,factors adjusted for,findings

and comments.

4.1.Study quality

Research designs employed in this field divide into the

quasi-experimentalsuch as case controlor cohortstudies

with an emphasison directcomparison ofresultsfor

matched groups,and more ‘natural’ observationalstudies

which rely on multivariate analysis to adjust for the effect

known confounders. Quasi-experimental studies (case co

trol and cohort designs) try to come as close to an experi

as possible with random assignmentto ‘treatment’and

‘control’groupswith differentlevels ofexposure to an

intervention,e.g.patients exposed to high levels ofstaff

compared with patients exposed to low staffing levels. No

experimental research designs are more familiar in the so

sciences,where ithasbeen argued thatif a significant

relationship persists after partialing out the effects of con

founding variables (robust dependence), then a causal re

tionshipcan be said to exist (Goldthorpe,2000).In

observationalstudiesof this type there are no ‘control’

group or ‘treatment’ groups and the effects of confoundin

variables are controlled statistically. Although quasi-expe

mental studies do also use multi-variate statistics they te

do so to compensate for failures in matching case and co

groups rather than their main strategy.For the purposes of

this paperthereforewe makea very cleardistinction

between these two types of studies because the differenc

are relevantto the ways in which the studies should be

evaluated.

A great number of tools exist for evaluating randomise

trials (Moher etal.,1995).Downs and Black (1998) also

devised a quality checklistfor non-randomised as wellas

randomised studies buttheir work only extends as far as

quasi-experimental designs. To date, we are not aware of

systematic attempt to develop measures of quality for stu

of this type and so we designed a rudimentary measure

focussing on the following areasas a preliminary step

towards more formal attempts to establish criteria for obs

vational studies.

1. Geographical scope (4): The numbers of patient and un

in the study. The concern here is with how far the resu

can be generalised to other populations, and the geogr

phical coverage of the study is salient. High scores wou

be given to a census or random sample of units across

nation ora large geographicalarea.Medium scores

would be given to a study of a smaller number of units

and a low score would be given to a single-unit study.

2. Quality ofdata (4):How and why were the data were

collected.High scores would be assigned to data that

were collected prospectively to answer the specific que

tions in the study. Low scores would be given to studie

that use data collected for other purposes,e.g. adminis-

trative data.

3. Validity of key independent variables (4): How sensitive

and specific are the key workforce measures as indicat

of the number and quality of nurses available to indivi-

dualpatients? Nurse–patientratios are often averaged

overlong periods oftime and may be simply dichot-

omised into ‘high’ or ‘low.’ High scores would be given

the information on nurses was collected over time and

linked to individualpatients.Medium scores would be

E. West et al. / International Journal of Nursing Studies 46 (2009) 993–1011996

identified 12 studies of nurse staffing,and presented evi-

dence for a positive effectof increased nurse staffing on

patient outcomes. More recently, Carayon and Gurses (2005)

conducted a wide ranging review ofthe literature.Their

main goalwas to devise a ‘human factorsengineering’

framework to guide modification ofthe work setting to

improve patient safety and to improve the quality of nurses’

work lives in ICUs. They cite several studies that have shown

thatmedicalerrorsare common in ICUsand may be

attributable to problems in communication between nurses

and physicians,to impaired access to information,and to

high intensity nursing workloads. They identified 22 studies

in all,but made no attempt to evaluate them or aggregate

their findings. They concluded that there were at least four

differentkinds of workload associated with the unit,job,

patient and situation. Most studies to date have focussed on

workload associated with the first two: the unit or the patient.

Each of the above reviewsmakesa contribution to

knowledge aboutworkforce,workload and outcomesin

intensive care.The emerging consensus seems to be that

while there is some evidence that the nursing workforce has

an impacton patients’risksof adverse events,there is

insufficient evidence of a link with mortality. This presents

a puzzle because some of the adverse events studied have

known links to mortality.Why would nursing workforce

characteristics affect the more proximate events but not the

final outcome? The process of dying is likely to be one of an

accumulation of adverse events as the patientdeteriorates

and clinicians take increasing risks in an attempt to save their

life. It seems important then to begin to integrate these two

separate strands of work into one coherent analysis.

This study uses systematic review methods to identify

and appraise empiricalevidence aboutthe impactof any

human capital characteristic of the nursing workforce (such

as skill mix, education or employments status, in addition to

nurse–patient ratios) on any patient outcomes,particularly

adverse events such as post-operative infections and mor-

tality.It adds to the literature a deeper description of the

methodsused and attemptsto evaluate the quality and

scientific rigour of the studies reviewed.

4. Results of the literature search

Fifteen studies were identified. Table 1 in the appendix to

this paper shows the key features of each study,including

location,research design,sample,sources of data,nursing

variables,outcome variables,factors adjusted for,findings

and comments.

4.1.Study quality

Research designs employed in this field divide into the

quasi-experimentalsuch as case controlor cohortstudies

with an emphasison directcomparison ofresultsfor

matched groups,and more ‘natural’ observationalstudies

which rely on multivariate analysis to adjust for the effect

known confounders. Quasi-experimental studies (case co

trol and cohort designs) try to come as close to an experi

as possible with random assignmentto ‘treatment’and

‘control’groupswith differentlevels ofexposure to an

intervention,e.g.patients exposed to high levels ofstaff

compared with patients exposed to low staffing levels. No

experimental research designs are more familiar in the so

sciences,where ithasbeen argued thatif a significant

relationship persists after partialing out the effects of con

founding variables (robust dependence), then a causal re

tionshipcan be said to exist (Goldthorpe,2000).In

observationalstudiesof this type there are no ‘control’

group or ‘treatment’ groups and the effects of confoundin

variables are controlled statistically. Although quasi-expe

mental studies do also use multi-variate statistics they te

do so to compensate for failures in matching case and co

groups rather than their main strategy.For the purposes of

this paperthereforewe makea very cleardistinction

between these two types of studies because the differenc

are relevantto the ways in which the studies should be

evaluated.

A great number of tools exist for evaluating randomise

trials (Moher etal.,1995).Downs and Black (1998) also

devised a quality checklistfor non-randomised as wellas

randomised studies buttheir work only extends as far as

quasi-experimental designs. To date, we are not aware of

systematic attempt to develop measures of quality for stu

of this type and so we designed a rudimentary measure

focussing on the following areasas a preliminary step

towards more formal attempts to establish criteria for obs

vational studies.

1. Geographical scope (4): The numbers of patient and un

in the study. The concern here is with how far the resu

can be generalised to other populations, and the geogr

phical coverage of the study is salient. High scores wou

be given to a census or random sample of units across

nation ora large geographicalarea.Medium scores

would be given to a study of a smaller number of units

and a low score would be given to a single-unit study.

2. Quality ofdata (4):How and why were the data were

collected.High scores would be assigned to data that

were collected prospectively to answer the specific que

tions in the study. Low scores would be given to studie

that use data collected for other purposes,e.g. adminis-

trative data.

3. Validity of key independent variables (4): How sensitive

and specific are the key workforce measures as indicat

of the number and quality of nurses available to indivi-

dualpatients? Nurse–patientratios are often averaged

overlong periods oftime and may be simply dichot-

omised into ‘high’ or ‘low.’ High scores would be given

the information on nurses was collected over time and

linked to individualpatients.Medium scores would be

E. West et al. / International Journal of Nursing Studies 46 (2009) 993–1011996

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

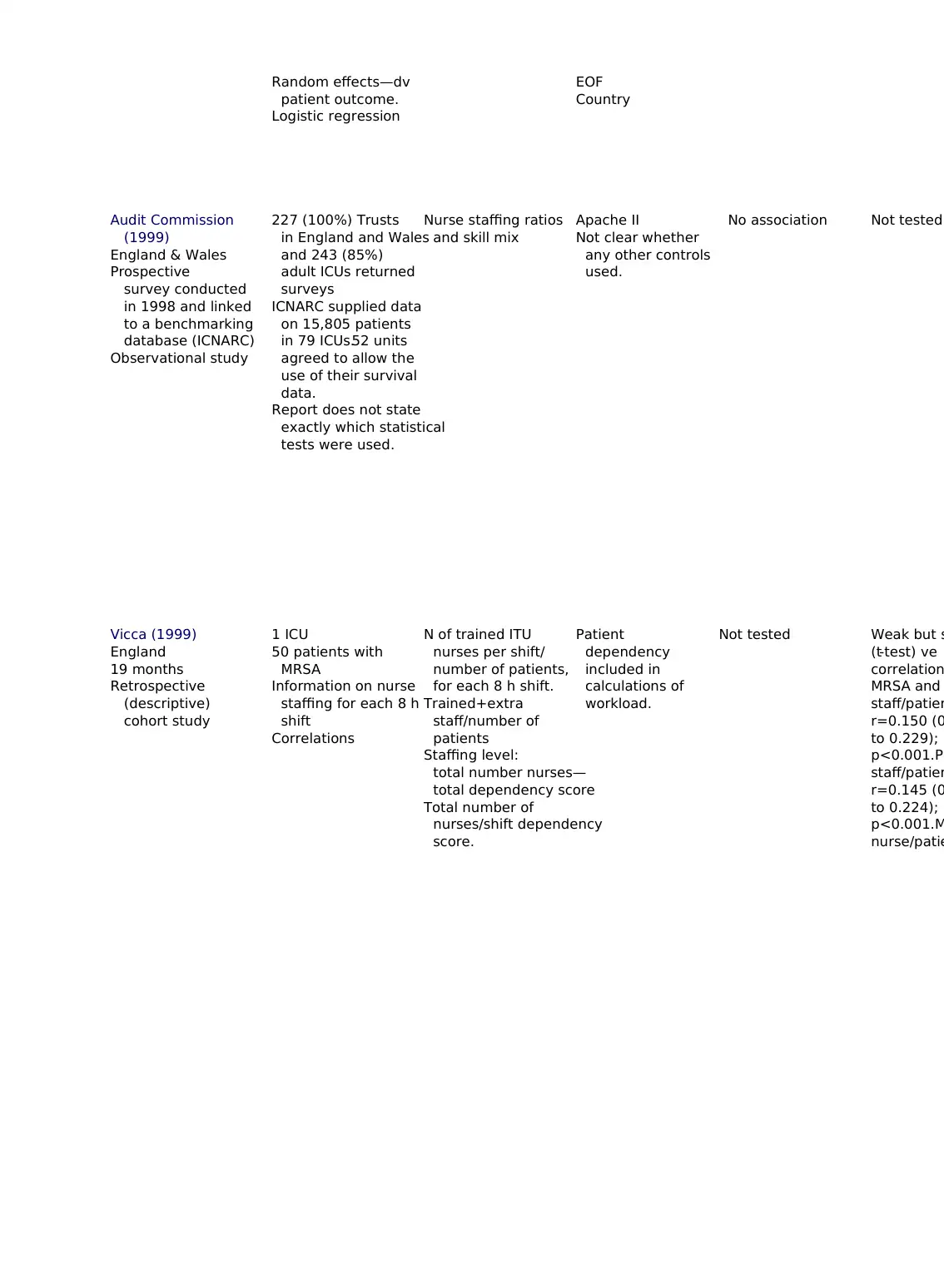

Table 1

Studies of nursing resources and patient outcomes: Main characteristics and results

Reference N of units Nursing variables Risk adjustment,

other controls

Relationship to

mortality,size of

effect,significance

Relationshi

adverse ev

size of effe

significance

Location N of patients

Period studied Data analysis

Design

Giraud et al.

(1993)

France

1989

Prospective

observational

study

2 ICUs

382 patients (400

consecutive

admissions)

Monitored daily

by physicians

for iatrogenic

complications

(defined as

adverse events

that was

independent of the

patients disease)

Non-parametric

Kruskal–Wallis test

Multi-variate

logistic regression

Cox survival analysis

Nursing workload

subjectively

assessed by each

nurse on each

shift,with score

for each patient

in their care.Patient’s

total nursing workload

was sum of all shift

scores during their stay.

OMEGA system

measures nursing

workload based

on 47 diagnostic

and therapeutic items.

Age

Organ System

Failure Score

SAPS

Prognosis

For patients who

stayed >24 h,

mortality was

2 higher for

patients who

developed

complications after

adjusting for Organ

System Failure Score

and prognosis

RR=1.92 (1.28–2.56)

Total num

iatrogen

complica

316 whic

in 31% o

in sampl

complica

defined

with 3 le

death.

Increased

of major

when nu

workload

using Om

and sub

assessm

or exces

The tota

workload

patients

go on to

develop

was 16.1

of 52.85

associat

patients

moderat

and pati

develop

complica

score on

workload

11515 w

significa

Studies of nursing resources and patient outcomes: Main characteristics and results

Reference N of units Nursing variables Risk adjustment,

other controls

Relationship to

mortality,size of

effect,significance

Relationshi

adverse ev

size of effe

significance

Location N of patients

Period studied Data analysis

Design

Giraud et al.

(1993)

France

1989

Prospective

observational

study

2 ICUs

382 patients (400

consecutive

admissions)

Monitored daily

by physicians

for iatrogenic

complications

(defined as

adverse events

that was

independent of the

patients disease)

Non-parametric

Kruskal–Wallis test

Multi-variate

logistic regression

Cox survival analysis

Nursing workload

subjectively

assessed by each

nurse on each

shift,with score

for each patient

in their care.Patient’s

total nursing workload

was sum of all shift

scores during their stay.

OMEGA system

measures nursing

workload based

on 47 diagnostic

and therapeutic items.

Age

Organ System

Failure Score

SAPS

Prognosis

For patients who

stayed >24 h,

mortality was

2 higher for

patients who

developed

complications after

adjusting for Organ

System Failure Score

and prognosis

RR=1.92 (1.28–2.56)

Total num

iatrogen

complica

316 whic

in 31% o

in sampl

complica

defined

with 3 le

death.

Increased

of major

when nu

workload

using Om

and sub

assessm

or exces

The tota

workload

patients

go on to

develop

was 16.1

of 52.85

associat

patients

moderat

and pati

develop

complica

score on

workload

11515 w

significa

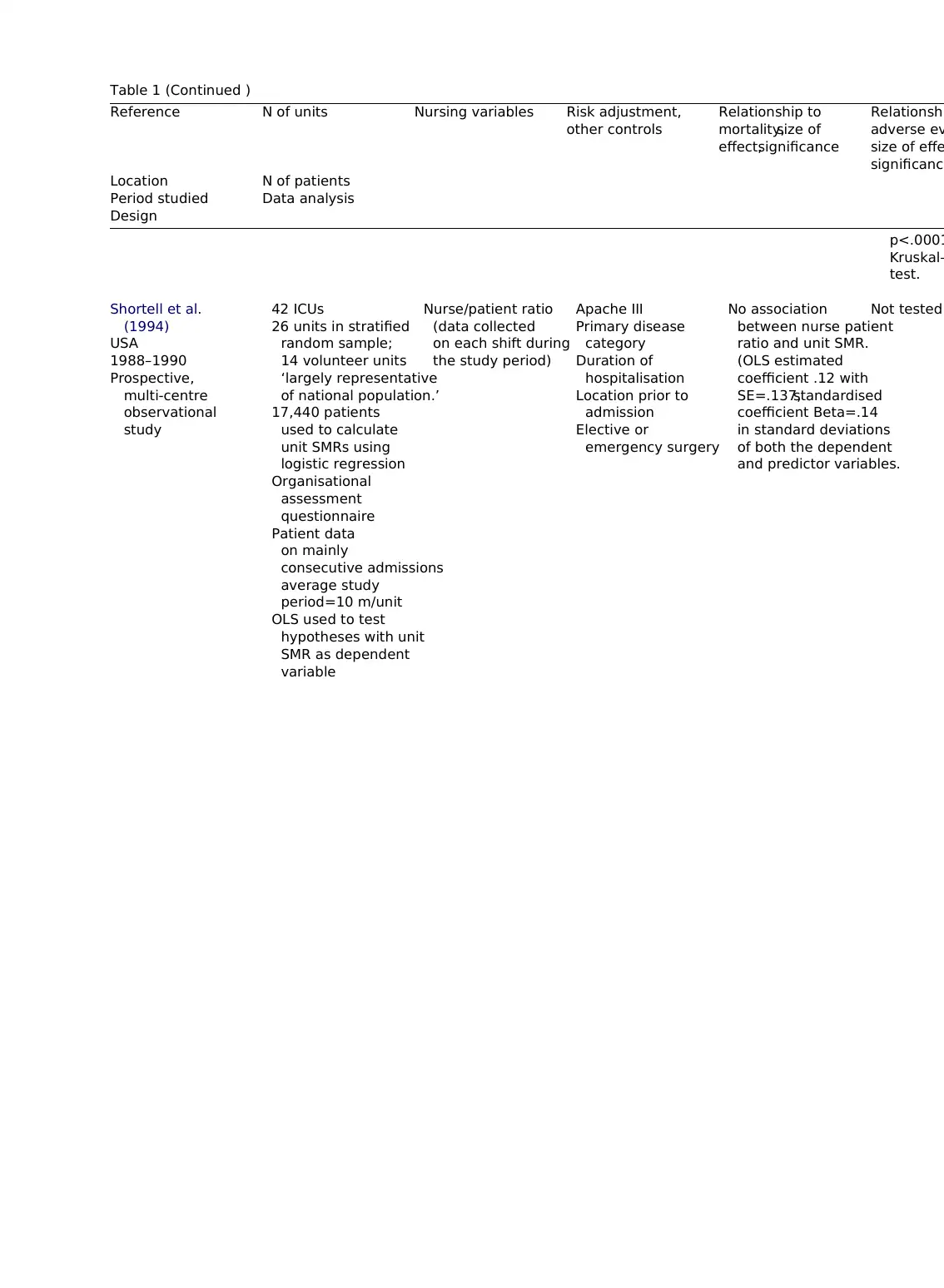

Table 1 (Continued )

Reference N of units Nursing variables Risk adjustment,

other controls

Relationship to

mortality,size of

effect,significance

Relationshi

adverse ev

size of effe

significance

Location N of patients

Period studied Data analysis

Design

p<.0001

Kruskal–

test.

Shortell et al.

(1994)

USA

1988–1990

Prospective,

multi-centre

observational

study

42 ICUs

26 units in stratified

random sample;

14 volunteer units

‘largely representative

of national population.’

17,440 patients

used to calculate

unit SMRs using

logistic regression

Organisational

assessment

questionnaire

Patient data

on mainly

consecutive admissions

average study

period=10 m/unit

OLS used to test

hypotheses with unit

SMR as dependent

variable

Nurse/patient ratio

(data collected

on each shift during

the study period)

Apache III

Primary disease

category

Duration of

hospitalisation

Location prior to

admission

Elective or

emergency surgery

No association

between nurse patient

ratio and unit SMR.

(OLS estimated

coefficient .12 with

SE=.137,standardised

coefficient Beta=.14

in standard deviations

of both the dependent

and predictor variables.

Not tested

Reference N of units Nursing variables Risk adjustment,

other controls

Relationship to

mortality,size of

effect,significance

Relationshi

adverse ev

size of effe

significance

Location N of patients

Period studied Data analysis

Design

p<.0001

Kruskal–

test.

Shortell et al.

(1994)

USA

1988–1990

Prospective,

multi-centre

observational

study

42 ICUs

26 units in stratified

random sample;

14 volunteer units

‘largely representative

of national population.’

17,440 patients

used to calculate

unit SMRs using

logistic regression

Organisational

assessment

questionnaire

Patient data

on mainly

consecutive admissions

average study

period=10 m/unit

OLS used to test

hypotheses with unit

SMR as dependent

variable

Nurse/patient ratio

(data collected

on each shift during

the study period)

Apache III

Primary disease

category

Duration of

hospitalisation

Location prior to

admission

Elective or

emergency surgery

No association

between nurse patient

ratio and unit SMR.

(OLS estimated

coefficient .12 with

SE=.137,standardised

coefficient Beta=.14

in standard deviations

of both the dependent

and predictor variables.

Not tested

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

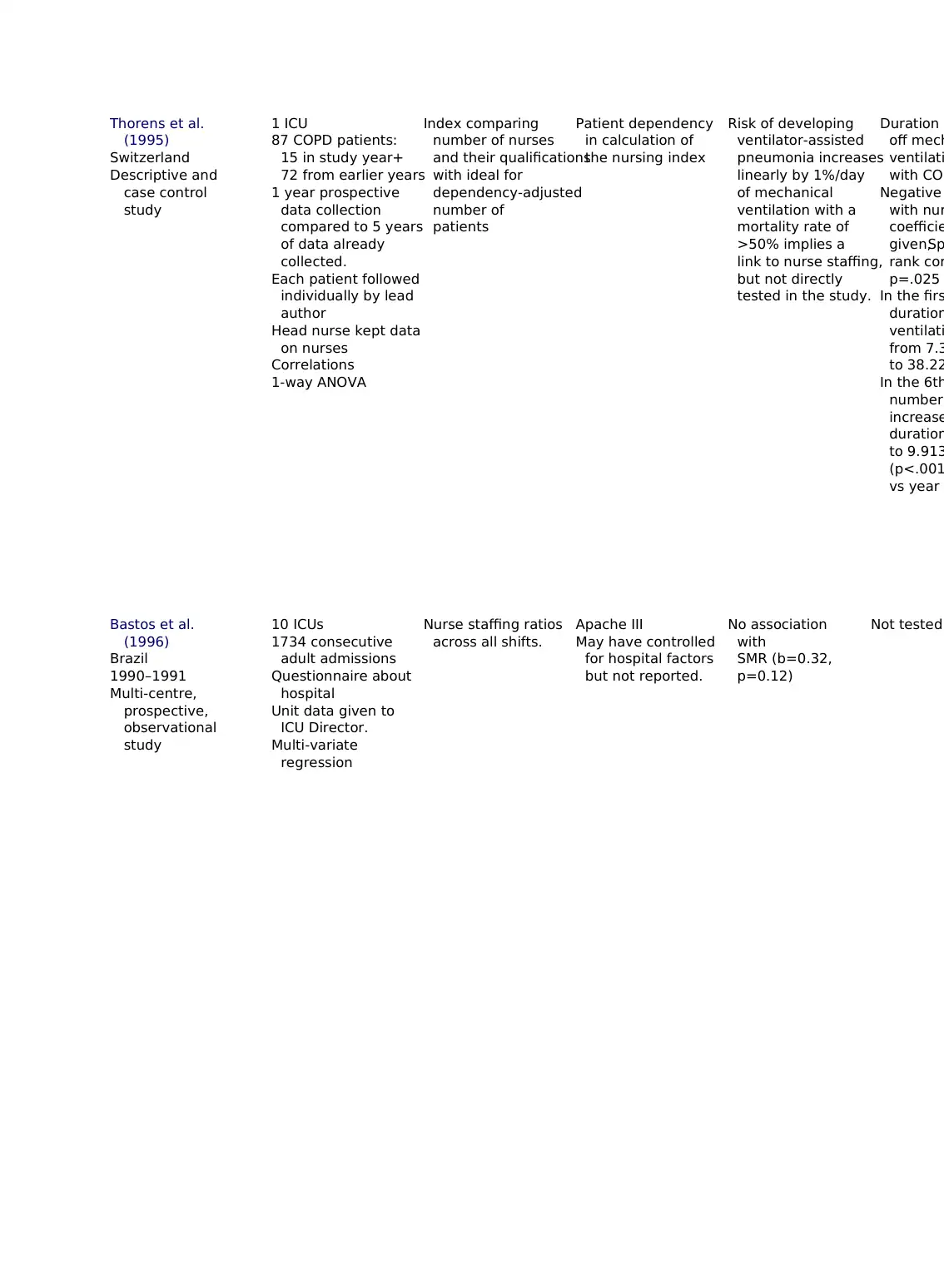

Thorens et al.

(1995)

Switzerland

Descriptive and

case control

study

1 ICU

87 COPD patients:

15 in study year+

72 from earlier years

1 year prospective

data collection

compared to 5 years

of data already

collected.

Each patient followed

individually by lead

author

Head nurse kept data

on nurses

Correlations

1-way ANOVA

Index comparing

number of nurses

and their qualifications

with ideal for

dependency-adjusted

number of

patients

Patient dependency

in calculation of

the nursing index

Risk of developing

ventilator-assisted

pneumonia increases

linearly by 1%/day

of mechanical

ventilation with a

mortality rate of

>50% implies a

link to nurse staffing,

but not directly

tested in the study.

Duration o

off mech

ventilati

with COP

Negative

with nur

coefficie

given,Sp

rank cor

p=.025

In the firs

duration

ventilati

from 7.3

to 38.22

In the 6th

number

increase

duration

to 9.913

(p<.001y

vs year 6

Bastos et al.

(1996)

Brazil

1990–1991

Multi-centre,

prospective,

observational

study

10 ICUs

1734 consecutive

adult admissions

Questionnaire about

hospital

Unit data given to

ICU Director.

Multi-variate

regression

Nurse staffing ratios

across all shifts.

Apache III

May have controlled

for hospital factors

but not reported.

No association

with

SMR (b=0.32,

p=0.12)

Not tested

(1995)

Switzerland

Descriptive and

case control

study

1 ICU

87 COPD patients:

15 in study year+

72 from earlier years

1 year prospective

data collection

compared to 5 years

of data already

collected.

Each patient followed

individually by lead

author

Head nurse kept data

on nurses

Correlations

1-way ANOVA

Index comparing

number of nurses

and their qualifications

with ideal for

dependency-adjusted

number of

patients

Patient dependency

in calculation of

the nursing index

Risk of developing

ventilator-assisted

pneumonia increases

linearly by 1%/day

of mechanical

ventilation with a

mortality rate of

>50% implies a

link to nurse staffing,

but not directly

tested in the study.

Duration o

off mech

ventilati

with COP

Negative

with nur

coefficie

given,Sp

rank cor

p=.025

In the firs

duration

ventilati

from 7.3

to 38.22

In the 6th

number

increase

duration

to 9.913

(p<.001y

vs year 6

Bastos et al.

(1996)

Brazil

1990–1991

Multi-centre,

prospective,

observational

study

10 ICUs

1734 consecutive

adult admissions

Questionnaire about

hospital

Unit data given to

ICU Director.

Multi-variate

regression

Nurse staffing ratios

across all shifts.

Apache III

May have controlled

for hospital factors

but not reported.

No association

with

SMR (b=0.32,

p=0.12)

Not tested

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

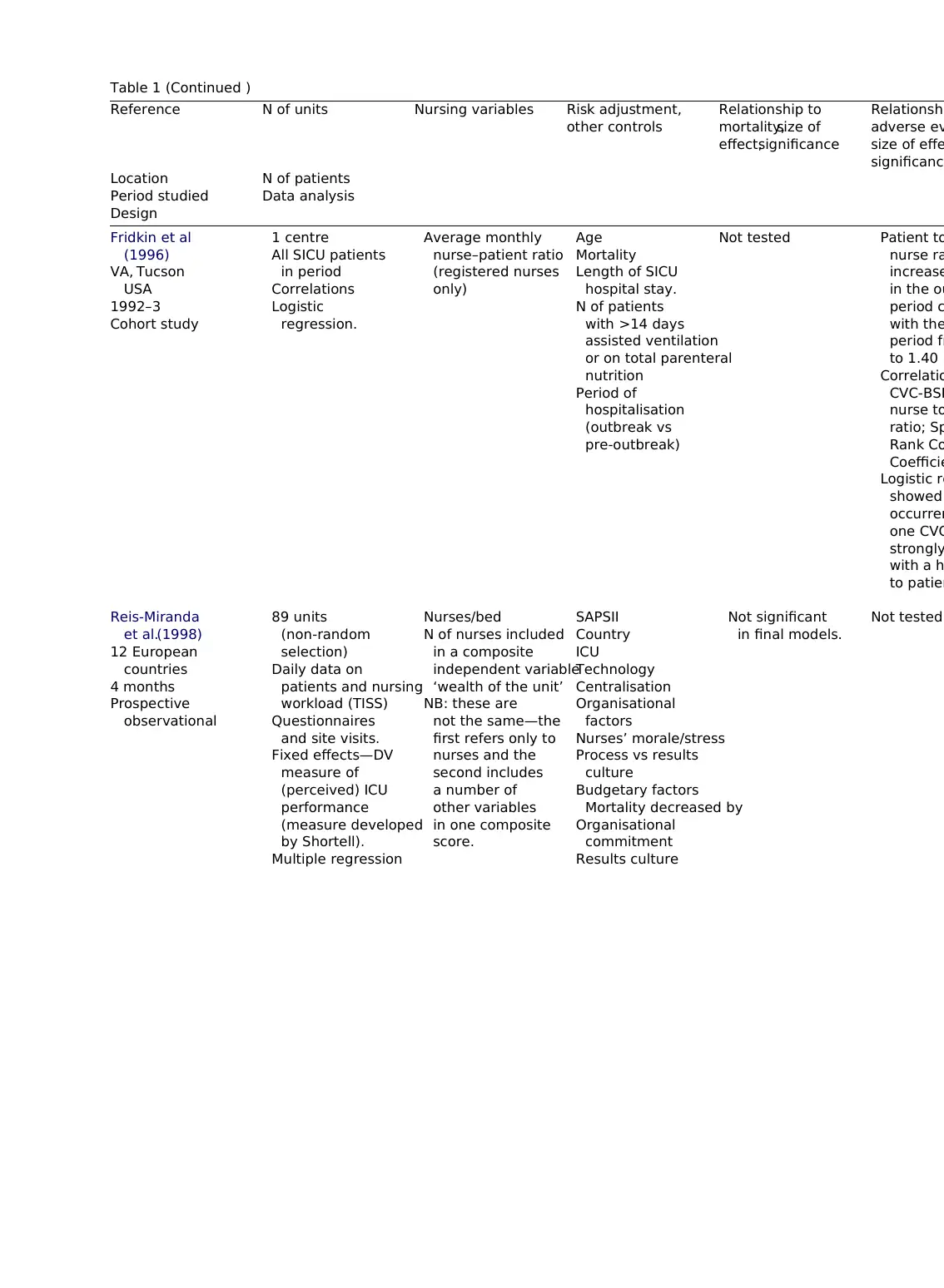

Table 1 (Continued )

Reference N of units Nursing variables Risk adjustment,

other controls

Relationship to

mortality,size of

effect,significance

Relationshi

adverse ev

size of effe

significance

Location N of patients

Period studied Data analysis

Design

Fridkin et al

(1996)

VA, Tucson

USA

1992–3

Cohort study

1 centre

All SICU patients

in period

Correlations

Logistic

regression.

Average monthly

nurse–patient ratio

(registered nurses

only)

Age

Mortality

Length of SICU

hospital stay.

N of patients

with >14 days

assisted ventilation

or on total parenteral

nutrition

Period of

hospitalisation

(outbreak vs

pre-outbreak)

Not tested Patient to

nurse ra

increase

in the ou

period c

with the

period fr

to 1.40 (

Correlatio

CVC-BSI

nurse to

ratio; Sp

Rank Co

Coefficie

Logistic re

showed

occurren

one CVC

strongly

with a h

to patien

Reis-Miranda

et al.(1998)

12 European

countries

4 months

Prospective

observational

89 units

(non-random

selection)

Daily data on

patients and nursing

workload (TISS)

Questionnaires

and site visits.

Fixed effects—DV

measure of

(perceived) ICU

performance

(measure developed

by Shortell).

Multiple regression

Nurses/bed

N of nurses included

in a composite

independent variable

‘wealth of the unit’

NB: these are

not the same—the

first refers only to

nurses and the

second includes

a number of

other variables

in one composite

score.

SAPSII

Country

ICU

Technology

Centralisation

Organisational

factors

Nurses’ morale/stress

Process vs results

culture

Budgetary factors

Mortality decreased by

Organisational

commitment

Results culture

Not significant

in final models.

Not tested

Reference N of units Nursing variables Risk adjustment,

other controls

Relationship to

mortality,size of

effect,significance

Relationshi

adverse ev

size of effe

significance

Location N of patients

Period studied Data analysis

Design

Fridkin et al

(1996)

VA, Tucson

USA

1992–3

Cohort study

1 centre

All SICU patients

in period

Correlations

Logistic

regression.

Average monthly

nurse–patient ratio

(registered nurses

only)

Age

Mortality

Length of SICU

hospital stay.

N of patients

with >14 days

assisted ventilation

or on total parenteral

nutrition

Period of

hospitalisation

(outbreak vs

pre-outbreak)

Not tested Patient to

nurse ra

increase

in the ou

period c

with the

period fr

to 1.40 (

Correlatio

CVC-BSI

nurse to

ratio; Sp

Rank Co

Coefficie

Logistic re

showed

occurren

one CVC

strongly

with a h

to patien

Reis-Miranda

et al.(1998)

12 European

countries

4 months

Prospective

observational

89 units

(non-random

selection)

Daily data on

patients and nursing

workload (TISS)

Questionnaires

and site visits.

Fixed effects—DV

measure of

(perceived) ICU

performance

(measure developed

by Shortell).

Multiple regression

Nurses/bed

N of nurses included

in a composite

independent variable

‘wealth of the unit’

NB: these are

not the same—the

first refers only to

nurses and the

second includes

a number of

other variables

in one composite

score.

SAPSII

Country

ICU

Technology

Centralisation

Organisational

factors

Nurses’ morale/stress

Process vs results

culture

Budgetary factors

Mortality decreased by

Organisational

commitment

Results culture

Not significant

in final models.

Not tested

Random effects—dv

patient outcome.

Logistic regression

EOF

Country

Audit Commission

(1999)

England & Wales

Prospective

survey conducted

in 1998 and linked

to a benchmarking

database (ICNARC)

Observational study

227 (100%) Trusts

in England and Wales

and 243 (85%)

adult ICUs returned

surveys

ICNARC supplied data

on 15,805 patients

in 79 ICUs.52 units

agreed to allow the

use of their survival

data.

Report does not state

exactly which statistical

tests were used.

Nurse staffing ratios

and skill mix

Apache II

Not clear whether

any other controls

used.

No association Not tested

Vicca (1999)

England

19 months

Retrospective

(descriptive)

cohort study

1 ICU

50 patients with

MRSA

Information on nurse

staffing for each 8 h

shift

Correlations

N of trained ITU

nurses per shift/

number of patients,

for each 8 h shift.

Trained+extra

staff/number of

patients

Staffing level:

total number nurses—

total dependency score

Total number of

nurses/shift dependency

score.

Patient

dependency

included in

calculations of

workload.

Not tested Weak but s

(t-test) ve

correlation

MRSA and

staff/patien

r=0.150 (0

to 0.229);

p<0.001.Pe

staff/patien

r=0.145 (0

to 0.224);

p<0.001.M

nurse/patie

patient outcome.

Logistic regression

EOF

Country

Audit Commission

(1999)

England & Wales

Prospective

survey conducted

in 1998 and linked

to a benchmarking

database (ICNARC)

Observational study

227 (100%) Trusts

in England and Wales

and 243 (85%)

adult ICUs returned

surveys

ICNARC supplied data

on 15,805 patients

in 79 ICUs.52 units

agreed to allow the

use of their survival

data.

Report does not state

exactly which statistical

tests were used.

Nurse staffing ratios

and skill mix

Apache II

Not clear whether

any other controls

used.

No association Not tested

Vicca (1999)

England

19 months

Retrospective

(descriptive)

cohort study

1 ICU

50 patients with

MRSA

Information on nurse

staffing for each 8 h

shift

Correlations

N of trained ITU

nurses per shift/

number of patients,

for each 8 h shift.

Trained+extra

staff/number of

patients

Staffing level:

total number nurses—

total dependency score

Total number of

nurses/shift dependency

score.

Patient

dependency

included in

calculations of

workload.

Not tested Weak but s

(t-test) ve

correlation

MRSA and

staff/patien

r=0.150 (0

to 0.229);

p<0.001.Pe

staff/patien

r=0.145 (0

to 0.224);

p<0.001.M

nurse/patie

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

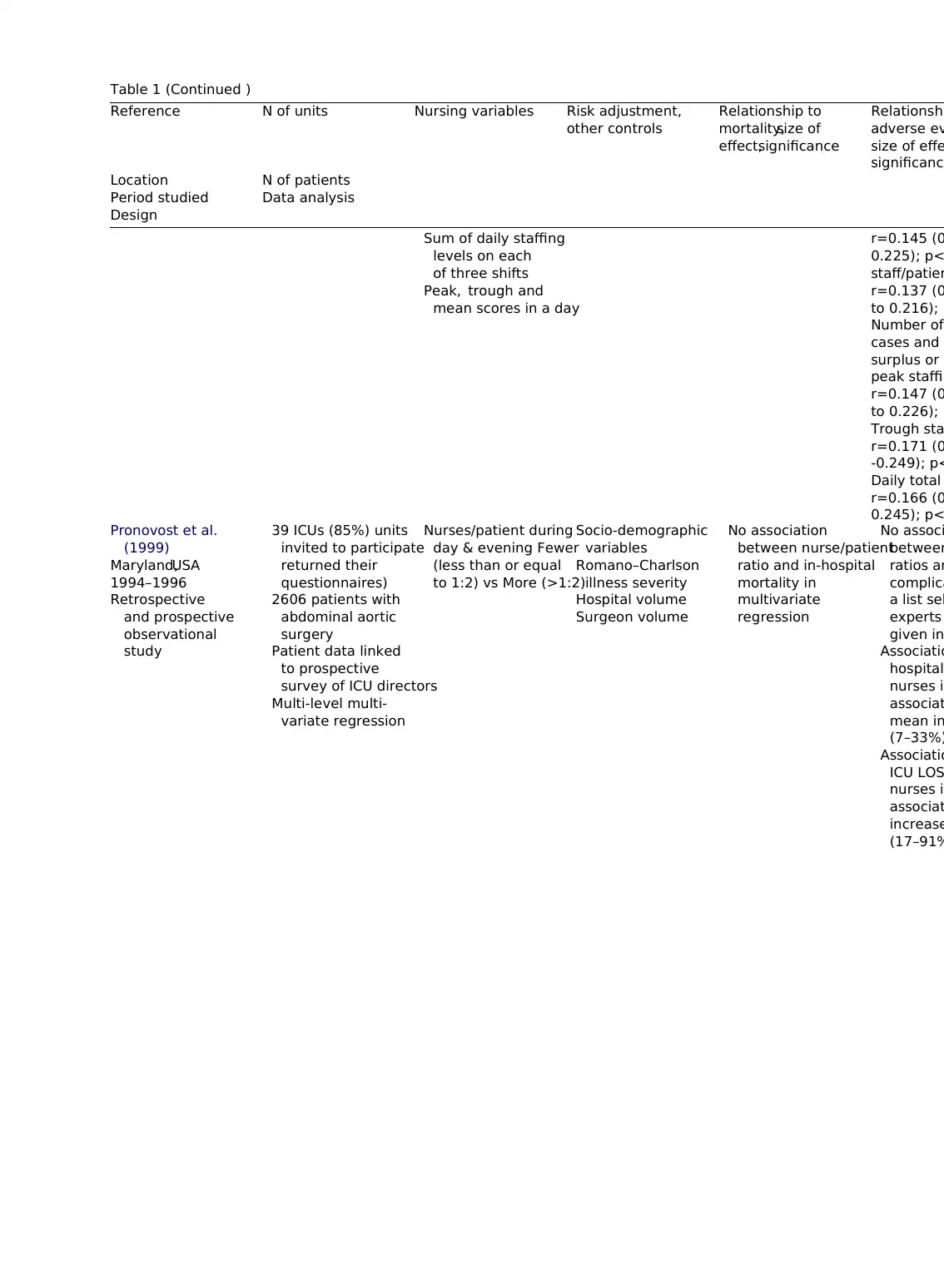

Table 1 (Continued )

Reference N of units Nursing variables Risk adjustment,

other controls

Relationship to

mortality,size of

effect,significance

Relationshi

adverse ev

size of effe

significance

Location N of patients

Period studied Data analysis

Design

Sum of daily staffing

levels on each

of three shifts

Peak, trough and

mean scores in a day

r=0.145 (0

0.225); p<

staff/patien

r=0.137 (0

to 0.216); p

Number of

cases and

surplus or d

peak staffin

r=0.147 (0

to 0.226); p

Trough sta

r=0.171 (0

-0.249); p<

Daily total

r=0.166 (0

0.245); p<

Pronovost et al.

(1999)

Maryland,USA

1994–1996

Retrospective

and prospective

observational

study

39 ICUs (85%) units

invited to participate

returned their

questionnaires)

2606 patients with

abdominal aortic

surgery

Patient data linked

to prospective

survey of ICU directors

Multi-level multi-

variate regression

Nurses/patient during

day & evening Fewer

(less than or equal

to 1:2) vs More (>1:2)

Socio-demographic

variables

Romano–Charlson

illness severity

Hospital volume

Surgeon volume

No association

between nurse/patient

ratio and in-hospital

mortality in

multivariate

regression

No associ

between

ratios an

complica

a list sel

experts

given in

Associatio

hospital

nurses in

associat

mean in

(7–33%)

Associatio

ICU LOS

nurses in

associat

increase

(17–91%

Reference N of units Nursing variables Risk adjustment,

other controls

Relationship to

mortality,size of

effect,significance

Relationshi

adverse ev

size of effe

significance

Location N of patients

Period studied Data analysis

Design

Sum of daily staffing

levels on each

of three shifts

Peak, trough and

mean scores in a day

r=0.145 (0

0.225); p<

staff/patien

r=0.137 (0

to 0.216); p

Number of

cases and

surplus or d

peak staffin

r=0.147 (0

to 0.226); p

Trough sta

r=0.171 (0

-0.249); p<

Daily total

r=0.166 (0

0.245); p<

Pronovost et al.

(1999)

Maryland,USA

1994–1996

Retrospective

and prospective

observational

study

39 ICUs (85%) units

invited to participate

returned their

questionnaires)

2606 patients with

abdominal aortic

surgery

Patient data linked

to prospective

survey of ICU directors

Multi-level multi-

variate regression

Nurses/patient during

day & evening Fewer

(less than or equal

to 1:2) vs More (>1:2)

Socio-demographic

variables

Romano–Charlson

illness severity

Hospital volume

Surgeon volume

No association

between nurse/patient

ratio and in-hospital

mortality in

multivariate

regression

No associ

between

ratios an

complica

a list sel

experts

given in

Associatio

hospital

nurses in

associat

mean in

(7–33%)

Associatio

ICU LOS

nurses in

associat

increase

(17–91%

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

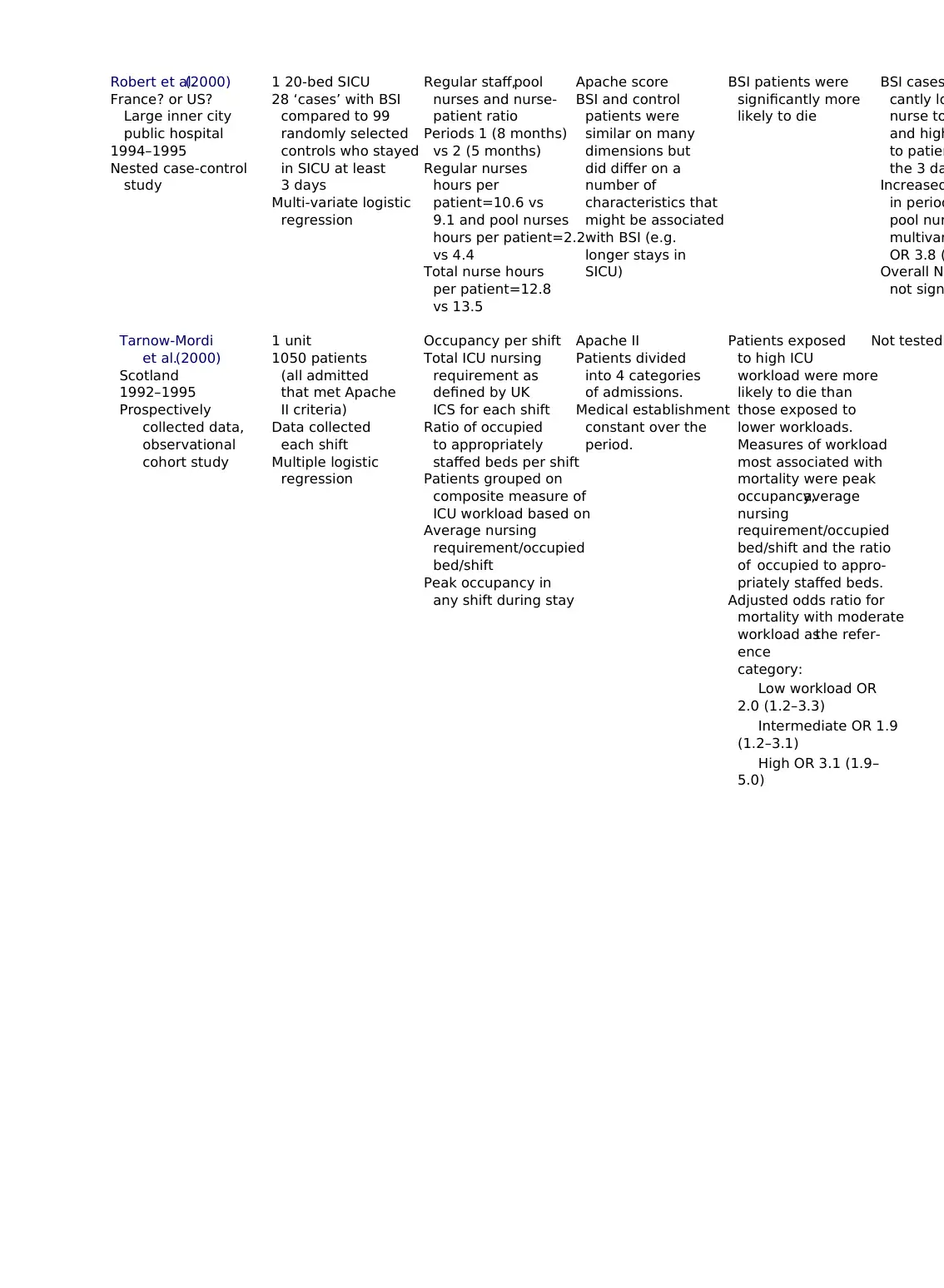

Robert et al.(2000)

France? or US?

Large inner city

public hospital

1994–1995

Nested case-control

study

1 20-bed SICU

28 ‘cases’ with BSI

compared to 99

randomly selected

controls who stayed

in SICU at least

3 days

Multi-variate logistic

regression

Regular staff,pool

nurses and nurse-

patient ratio

Periods 1 (8 months)

vs 2 (5 months)

Regular nurses

hours per

patient=10.6 vs

9.1 and pool nurses

hours per patient=2.2

vs 4.4

Total nurse hours

per patient=12.8

vs 13.5

Apache score

BSI and control

patients were

similar on many

dimensions but

did differ on a

number of

characteristics that

might be associated

with BSI (e.g.

longer stays in

SICU)

BSI patients were

significantly more

likely to die

BSI cases

cantly lo

nurse to

and high

to patien

the 3 da

Increased

in period

pool nur

multivar

OR 3.8 (

Overall N–

not sign

Tarnow-Mordi

et al.(2000)

Scotland

1992–1995

Prospectively

collected data,

observational

cohort study

1 unit

1050 patients

(all admitted

that met Apache

II criteria)

Data collected

each shift

Multiple logistic

regression

Occupancy per shift

Total ICU nursing

requirement as

defined by UK

ICS for each shift

Ratio of occupied

to appropriately

staffed beds per shift

Patients grouped on

composite measure of

ICU workload based on

Average nursing

requirement/occupied

bed/shift

Peak occupancy in

any shift during stay

Apache II

Patients divided

into 4 categories

of admissions.

Medical establishment

constant over the

period.

Patients exposed

to high ICU

workload were more

likely to die than

those exposed to

lower workloads.

Measures of workload

most associated with

mortality were peak

occupancy,average

nursing

requirement/occupied

bed/shift and the ratio

of occupied to appro-

priately staffed beds.

Adjusted odds ratio for

mortality with moderate

workload asthe refer-

ence

category:

Low workload OR

2.0 (1.2–3.3)

Intermediate OR 1.9

(1.2–3.1)

High OR 3.1 (1.9–

5.0)

Not tested

France? or US?

Large inner city

public hospital

1994–1995

Nested case-control

study

1 20-bed SICU

28 ‘cases’ with BSI

compared to 99

randomly selected

controls who stayed

in SICU at least

3 days

Multi-variate logistic

regression

Regular staff,pool

nurses and nurse-

patient ratio

Periods 1 (8 months)

vs 2 (5 months)

Regular nurses

hours per

patient=10.6 vs

9.1 and pool nurses

hours per patient=2.2

vs 4.4

Total nurse hours

per patient=12.8

vs 13.5

Apache score

BSI and control

patients were

similar on many

dimensions but

did differ on a

number of

characteristics that

might be associated

with BSI (e.g.

longer stays in

SICU)

BSI patients were

significantly more

likely to die

BSI cases

cantly lo

nurse to

and high

to patien

the 3 da

Increased

in period

pool nur

multivar

OR 3.8 (

Overall N–

not sign

Tarnow-Mordi

et al.(2000)

Scotland

1992–1995

Prospectively

collected data,

observational

cohort study

1 unit

1050 patients

(all admitted

that met Apache

II criteria)

Data collected

each shift

Multiple logistic

regression

Occupancy per shift

Total ICU nursing

requirement as

defined by UK

ICS for each shift

Ratio of occupied

to appropriately

staffed beds per shift

Patients grouped on

composite measure of

ICU workload based on

Average nursing

requirement/occupied

bed/shift

Peak occupancy in

any shift during stay

Apache II

Patients divided

into 4 categories

of admissions.

Medical establishment

constant over the

period.

Patients exposed

to high ICU

workload were more

likely to die than

those exposed to

lower workloads.

Measures of workload

most associated with

mortality were peak

occupancy,average

nursing

requirement/occupied

bed/shift and the ratio

of occupied to appro-

priately staffed beds.

Adjusted odds ratio for

mortality with moderate

workload asthe refer-

ence

category:

Low workload OR

2.0 (1.2–3.3)

Intermediate OR 1.9

(1.2–3.1)

High OR 3.1 (1.9–

5.0)

Not tested

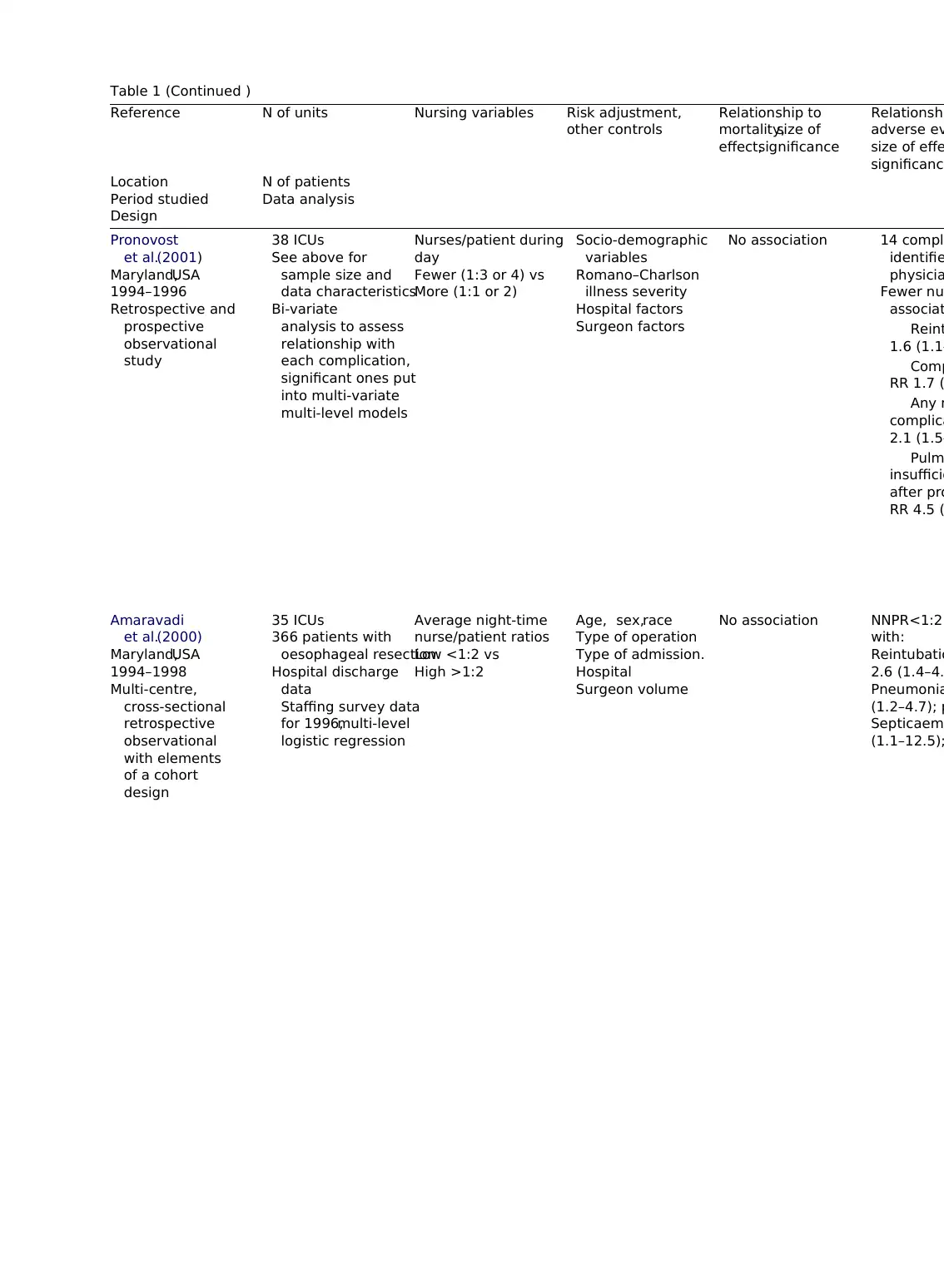

Table 1 (Continued )

Reference N of units Nursing variables Risk adjustment,

other controls

Relationship to

mortality,size of

effect,significance

Relationshi

adverse ev

size of effe

significance

Location N of patients

Period studied Data analysis

Design

Pronovost

et al.(2001)

Maryland,USA

1994–1996

Retrospective and

prospective

observational

study

38 ICUs

See above for

sample size and

data characteristics

Bi-variate

analysis to assess

relationship with

each complication,

significant ones put

into multi-variate

multi-level models

Nurses/patient during

day

Fewer (1:3 or 4) vs

More (1:1 or 2)

Socio-demographic

variables

Romano–Charlson

illness severity

Hospital factors

Surgeon factors

No association 14 compli

identifie

physicia

Fewer nu

associat

Reint

1.6 (1.1–

Comp

RR 1.7 (

Any m

complica

2.1 (1.5–

Pulm

insufficie

after pro

RR 4.5 (

Amaravadi

et al.(2000)

Maryland,USA

1994–1998

Multi-centre,

cross-sectional

retrospective

observational

with elements

of a cohort

design

35 ICUs

366 patients with

oesophageal resection

Hospital discharge

data

Staffing survey data

for 1996,multi-level

logistic regression

Average night-time

nurse/patient ratios

Low <1:2 vs

High >1:2

Age, sex,race

Type of operation

Type of admission.

Hospital

Surgeon volume

No association NNPR<1:2

with:

Reintubatio

2.6 (1.4–4.

Pneumonia

(1.2–4.7); p

Septicaemi

(1.1–12.5);

Reference N of units Nursing variables Risk adjustment,

other controls

Relationship to

mortality,size of

effect,significance

Relationshi

adverse ev

size of effe

significance

Location N of patients

Period studied Data analysis

Design

Pronovost

et al.(2001)

Maryland,USA

1994–1996

Retrospective and

prospective

observational

study

38 ICUs

See above for

sample size and

data characteristics

Bi-variate

analysis to assess

relationship with

each complication,

significant ones put

into multi-variate

multi-level models

Nurses/patient during

day

Fewer (1:3 or 4) vs

More (1:1 or 2)

Socio-demographic

variables

Romano–Charlson

illness severity

Hospital factors

Surgeon factors

No association 14 compli

identifie

physicia

Fewer nu

associat

Reint

1.6 (1.1–

Comp

RR 1.7 (

Any m

complica

2.1 (1.5–

Pulm

insufficie

after pro

RR 4.5 (

Amaravadi

et al.(2000)

Maryland,USA

1994–1998

Multi-centre,

cross-sectional

retrospective

observational

with elements

of a cohort

design

35 ICUs

366 patients with

oesophageal resection

Hospital discharge

data

Staffing survey data

for 1996,multi-level

logistic regression

Average night-time

nurse/patient ratios

Low <1:2 vs

High >1:2

Age, sex,race

Type of operation

Type of admission.

Hospital

Surgeon volume

No association NNPR<1:2

with:

Reintubatio

2.6 (1.4–4.

Pneumonia

(1.2–4.7); p

Septicaemi

(1.1–12.5);

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 19

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.