Bridging Learning Investments and Service Performance in Public Sector

VerifiedAdded on 2022/12/28

|13

|7024

|20

Report

AI Summary

This report presents an in-depth analysis of the Organisational Learning Capability (OLC) model within the context of public sector organizations. The study explores how to bridge the gap between investments in learning initiatives and improvements in service provision by examining the role of digital technologies in enhancing learning programs. The research employs a mixed-methods approach, including a literature review and semi-structured interviews with experienced participants across various sectors. The findings are synthesized to propose an OLC model comprising key elements such as learning processes, enablers, and influential factors. The report highlights the importance of OLC in facilitating learning, addressing challenges in digital technology adoption, and ultimately improving service performance within public sector organizations. The study also discusses the role of coaching learning programs within the broader OLC framework and provides insights into the facilitating factors for the implementation of OLC.

Title of the Paper (16pt Times New Roman, Bold, Centered)

AUTHORS' NAMES ()

Department ()

University ()

Address ()

COUNTRY ()

Abstract: - Public organizations provide training to enhance their employee’s capabilities to provide better

services. Public organizations use different learning methods to enhance their employee’s skills and service

offering. Therefore, public organizations are considering different learning programs such as classroom

training, coaching, mentoring etc. For the organizations to be effective in providing the learning programs to

their employees, there is a need to have an approach to support these efforts. This study suggests that

Organizational Learning Capability (OLC) is the right approach to do that. This is because OLC facilitates the

learning process. The study proposes an OLC model consists of the key elements that represent the definition of

OLC; these are the learning processes, enablers, influential factors. This paper explores how organizations can

bridge the gap between investments in learning initiatives and improvement in service provision in public

organizations. The context of this study is the creation of a set of learning and development programs in the

public services organizations. The top OLC model helps to define all other learning programs where the

coaching learning program is presented in this paper.

Key-Words: - Organisational Learning capability, Learning programmes, Public services

organisations, Coaching learning programme, Learning process in organisations

Received:

1 Introduction

The advent of new digital technologies and

the gig economy present an opportunity for

revisiting the way learning programmes are

conducted. Organisations invest massively in

learning programmes to upskill human talent and

improve service offering. In 2016, $359 billion was

spent globally (Borzykowski, 2017). However, these

investments usually lack the expected impact on

service performance: three quarters of managers and

employees are dissatisfied and lack the required

skill to do their jobs (Glaveski 2019). Organisations

are considering digital technologies to address these

challenges, but, without the right deployment

strategy, they risk committing the same mistakes

and using technology for waste automation (Holweg

et al. 2018). Thus, adopting digital technologies to

deliver impactful and cost-effective learning

programmes requires an aligned deployment

framework that account for the challenges digital

technologies pose to learning, including employees’

difficulty to undertake and complete training

(Edmondson 2012).

The context of this study is the creation of a

set of learning programmes in public sector

organisations. The authors built a mixed-methods

field study focusing on coaching learning programs.

Data were collected and analysed during three

phases. First, the theoretical foundations of OLC

were reviewed, recording different key factors.

Second, semi-structured interviews were conducted

with multiple experienced participants across

industrial sectors in Europe and UAE to capture

their perspectives of the organisational learning

programs enablers and challenges. Third, findings

from the previous two phases were reconciled to

produce a model for OLC which includes a detailed

analysis of the role that digital technologies play in

enabling the organisational learning.

2 Problem Formulation

This paper explores how organisations can

bridge the gap between investments in learning

programmes and service performance in public

sector organisations. The author adopts an

organisational learning capability (OLC) perspective

to study what strategic enablers and influential

factors affecting the link between digital

technologies and organisational learning. OLC

emphasises on the ability of organisations to acquire

AUTHORS' NAMES ()

Department ()

University ()

Address ()

COUNTRY ()

Abstract: - Public organizations provide training to enhance their employee’s capabilities to provide better

services. Public organizations use different learning methods to enhance their employee’s skills and service

offering. Therefore, public organizations are considering different learning programs such as classroom

training, coaching, mentoring etc. For the organizations to be effective in providing the learning programs to

their employees, there is a need to have an approach to support these efforts. This study suggests that

Organizational Learning Capability (OLC) is the right approach to do that. This is because OLC facilitates the

learning process. The study proposes an OLC model consists of the key elements that represent the definition of

OLC; these are the learning processes, enablers, influential factors. This paper explores how organizations can

bridge the gap between investments in learning initiatives and improvement in service provision in public

organizations. The context of this study is the creation of a set of learning and development programs in the

public services organizations. The top OLC model helps to define all other learning programs where the

coaching learning program is presented in this paper.

Key-Words: - Organisational Learning capability, Learning programmes, Public services

organisations, Coaching learning programme, Learning process in organisations

Received:

1 Introduction

The advent of new digital technologies and

the gig economy present an opportunity for

revisiting the way learning programmes are

conducted. Organisations invest massively in

learning programmes to upskill human talent and

improve service offering. In 2016, $359 billion was

spent globally (Borzykowski, 2017). However, these

investments usually lack the expected impact on

service performance: three quarters of managers and

employees are dissatisfied and lack the required

skill to do their jobs (Glaveski 2019). Organisations

are considering digital technologies to address these

challenges, but, without the right deployment

strategy, they risk committing the same mistakes

and using technology for waste automation (Holweg

et al. 2018). Thus, adopting digital technologies to

deliver impactful and cost-effective learning

programmes requires an aligned deployment

framework that account for the challenges digital

technologies pose to learning, including employees’

difficulty to undertake and complete training

(Edmondson 2012).

The context of this study is the creation of a

set of learning programmes in public sector

organisations. The authors built a mixed-methods

field study focusing on coaching learning programs.

Data were collected and analysed during three

phases. First, the theoretical foundations of OLC

were reviewed, recording different key factors.

Second, semi-structured interviews were conducted

with multiple experienced participants across

industrial sectors in Europe and UAE to capture

their perspectives of the organisational learning

programs enablers and challenges. Third, findings

from the previous two phases were reconciled to

produce a model for OLC which includes a detailed

analysis of the role that digital technologies play in

enabling the organisational learning.

2 Problem Formulation

This paper explores how organisations can

bridge the gap between investments in learning

programmes and service performance in public

sector organisations. The author adopts an

organisational learning capability (OLC) perspective

to study what strategic enablers and influential

factors affecting the link between digital

technologies and organisational learning. OLC

emphasises on the ability of organisations to acquire

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

and translate knowledge from external sources,

operations, experiences and initiatives into

improvement changes (Leonard Barton 1992,

Popper and Lipshitz 1998).

2.1

Exploring OLC has the potential to highlight a

distinctive framework that advantage technological

investments in learning.

2.1.1

OLC addresses the individual, group and

organizational levels to realize the management

goals (Crossan, Lane, and White 1999, Goh 2003,

Lawrence et al. 2005).

3 Problem Solution

The Organizational Learning Capabilities

Research on organizational learning has focused

on the “change in the organization that occurs

as the organization acquires experience”

(Argote and Miron-Spektor 2011: 1124), from

at least three perspectives: behavioral,

knowledge and systems. Behavioral researchers

have compared concepts from individual

learning to organizational learning, highlighting

the role of bounded rationality and the

challenges of learning under uncertainty (March

and Olsen 1975, Levinthal and March 1993,

Simon 1991). Organizational learning

researchers focused on understanding the role

of knowledge in learning Finally, researchers

took a learning systems angle, finding

management practices that foster organizational

learning (Senge 2006, Örtenblad 2007, Back

2012, Caldwell 2012a, 2012b, Shrivastava

1983).

Barton (1992) operationalizes OLC as an

organization’s ability to acquire and translate

knowledge from external sources, operations,

experiences and initiatives into improvement

changes at the individual, group and

organizational level to realize the management

goals. While research on organizational

learning argues that learning causes myopia,

prevents innovation and causes structural

rigidity (Levinthal and March 1993, March and

Olsen 1975, Simon 1991), OLC provides an

alternative vantage point to analyses those

challenges. It argues that some organizational

structures, processes and values can become

enablers and influential factors for innovation

and adaptation and improvements. (Jiménez-

Jiménez and Sans-Valle 2011, Alegre and

Chiva 2008).

Enablers of the Organizational Learning

Capability

Different opinions about organizational learning

enablers can be broadly classified in acquire

and capture knowledge enablers, which allow

the organization to grab learning experiences

from its employees, associates, competitors and

the environment and establish a mode of

documentation (DiBella, Nevis, and Gould

1996); translate knowledge enablers, which

transform knowledge sources into learning and

integrate it across the organization, including

dissemination mode, and skill development

(DiBella, Nevis, and Gould 1996, Jerez-Gómez,

Céspedes-Lorente, and Valle-Cabrera 2005,

Goh 2003); realize management goals enablers,

which promote common mental models (e.g.

mission and vision) (Senge 1990, Goh 2003),

and reward systems (Goh 2003). Finally,

systemic change enablers such as those that

focus on leadership commitment, empowerment

and experimentation (Goh 2003, Jerez-Gómez,

Céspedes-Lorente, and Valle-Cabrera 2005,

Jerez Gómez, Céspedes Lorente, and Valle

Cabrera 2004, García-Morales, Jiménez-

Barrionuevo, and Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez 2012,

Moghadam et al. 2013). Table 1 present an

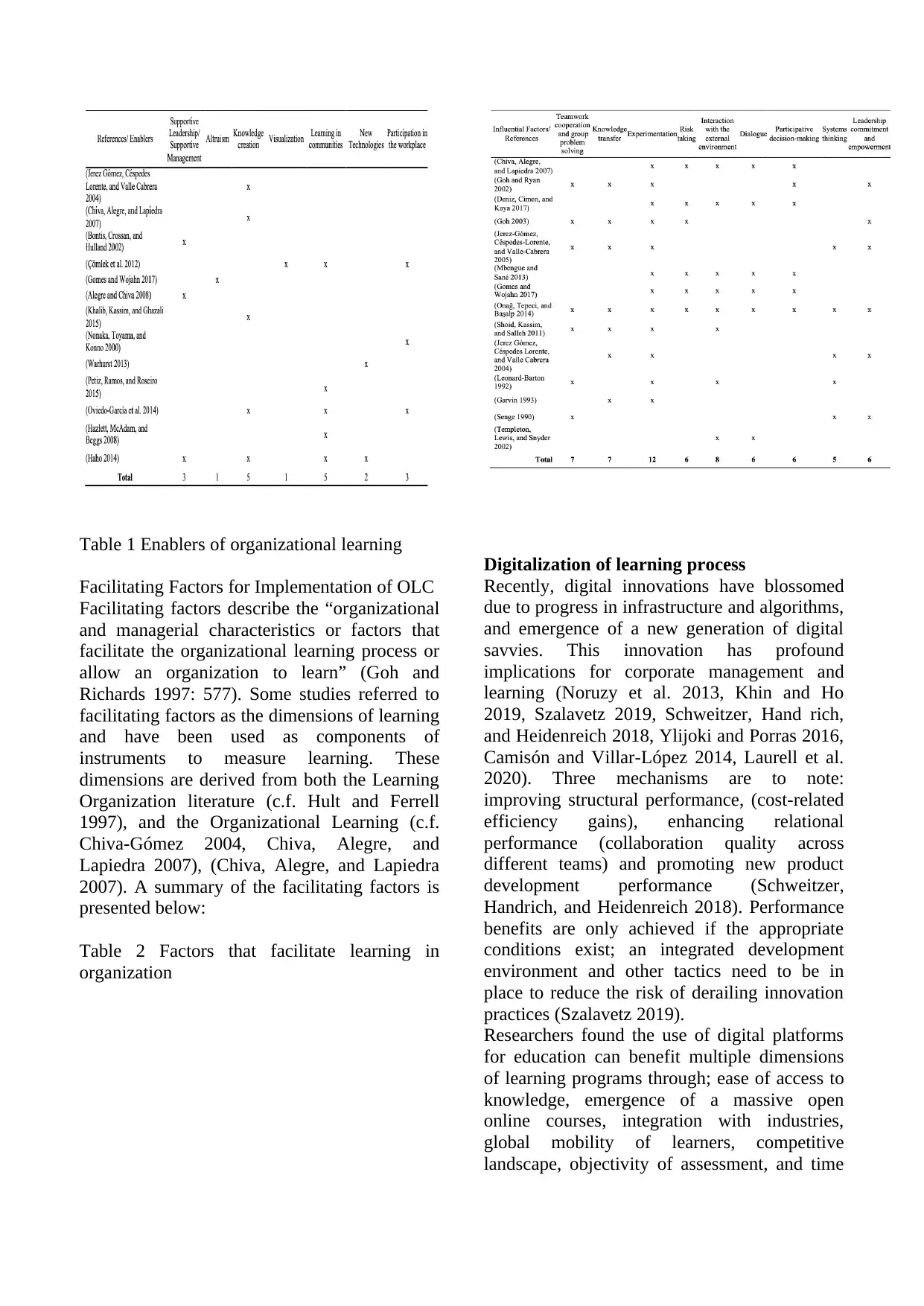

example of enablers considered in this study.

Table 1 present OLC enablers that are identified

from the reviewed literature.

operations, experiences and initiatives into

improvement changes (Leonard Barton 1992,

Popper and Lipshitz 1998).

2.1

Exploring OLC has the potential to highlight a

distinctive framework that advantage technological

investments in learning.

2.1.1

OLC addresses the individual, group and

organizational levels to realize the management

goals (Crossan, Lane, and White 1999, Goh 2003,

Lawrence et al. 2005).

3 Problem Solution

The Organizational Learning Capabilities

Research on organizational learning has focused

on the “change in the organization that occurs

as the organization acquires experience”

(Argote and Miron-Spektor 2011: 1124), from

at least three perspectives: behavioral,

knowledge and systems. Behavioral researchers

have compared concepts from individual

learning to organizational learning, highlighting

the role of bounded rationality and the

challenges of learning under uncertainty (March

and Olsen 1975, Levinthal and March 1993,

Simon 1991). Organizational learning

researchers focused on understanding the role

of knowledge in learning Finally, researchers

took a learning systems angle, finding

management practices that foster organizational

learning (Senge 2006, Örtenblad 2007, Back

2012, Caldwell 2012a, 2012b, Shrivastava

1983).

Barton (1992) operationalizes OLC as an

organization’s ability to acquire and translate

knowledge from external sources, operations,

experiences and initiatives into improvement

changes at the individual, group and

organizational level to realize the management

goals. While research on organizational

learning argues that learning causes myopia,

prevents innovation and causes structural

rigidity (Levinthal and March 1993, March and

Olsen 1975, Simon 1991), OLC provides an

alternative vantage point to analyses those

challenges. It argues that some organizational

structures, processes and values can become

enablers and influential factors for innovation

and adaptation and improvements. (Jiménez-

Jiménez and Sans-Valle 2011, Alegre and

Chiva 2008).

Enablers of the Organizational Learning

Capability

Different opinions about organizational learning

enablers can be broadly classified in acquire

and capture knowledge enablers, which allow

the organization to grab learning experiences

from its employees, associates, competitors and

the environment and establish a mode of

documentation (DiBella, Nevis, and Gould

1996); translate knowledge enablers, which

transform knowledge sources into learning and

integrate it across the organization, including

dissemination mode, and skill development

(DiBella, Nevis, and Gould 1996, Jerez-Gómez,

Céspedes-Lorente, and Valle-Cabrera 2005,

Goh 2003); realize management goals enablers,

which promote common mental models (e.g.

mission and vision) (Senge 1990, Goh 2003),

and reward systems (Goh 2003). Finally,

systemic change enablers such as those that

focus on leadership commitment, empowerment

and experimentation (Goh 2003, Jerez-Gómez,

Céspedes-Lorente, and Valle-Cabrera 2005,

Jerez Gómez, Céspedes Lorente, and Valle

Cabrera 2004, García-Morales, Jiménez-

Barrionuevo, and Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez 2012,

Moghadam et al. 2013). Table 1 present an

example of enablers considered in this study.

Table 1 present OLC enablers that are identified

from the reviewed literature.

Table 1 Enablers of organizational learning

Facilitating Factors for Implementation of OLC

Facilitating factors describe the “organizational

and managerial characteristics or factors that

facilitate the organizational learning process or

allow an organization to learn” (Goh and

Richards 1997: 577). Some studies referred to

facilitating factors as the dimensions of learning

and have been used as components of

instruments to measure learning. These

dimensions are derived from both the Learning

Organization literature (c.f. Hult and Ferrell

1997), and the Organizational Learning (c.f.

Chiva-Gómez 2004, Chiva, Alegre, and

Lapiedra 2007), (Chiva, Alegre, and Lapiedra

2007). A summary of the facilitating factors is

presented below:

Table 2 Factors that facilitate learning in

organization

Digitalization of learning process

Recently, digital innovations have blossomed

due to progress in infrastructure and algorithms,

and emergence of a new generation of digital

savvies. This innovation has profound

implications for corporate management and

learning (Noruzy et al. 2013, Khin and Ho

2019, Szalavetz 2019, Schweitzer, Hand rich,

and Heidenreich 2018, Ylijoki and Porras 2016,

Camisón and Villar-López 2014, Laurell et al.

2020). Three mechanisms are to note:

improving structural performance, (cost-related

efficiency gains), enhancing relational

performance (collaboration quality across

different teams) and promoting new product

development performance (Schweitzer,

Handrich, and Heidenreich 2018). Performance

benefits are only achieved if the appropriate

conditions exist; an integrated development

environment and other tactics need to be in

place to reduce the risk of derailing innovation

practices (Szalavetz 2019).

Researchers found the use of digital platforms

for education can benefit multiple dimensions

of learning programs through; ease of access to

knowledge, emergence of a massive open

online courses, integration with industries,

global mobility of learners, competitive

landscape, objectivity of assessment, and time

Facilitating Factors for Implementation of OLC

Facilitating factors describe the “organizational

and managerial characteristics or factors that

facilitate the organizational learning process or

allow an organization to learn” (Goh and

Richards 1997: 577). Some studies referred to

facilitating factors as the dimensions of learning

and have been used as components of

instruments to measure learning. These

dimensions are derived from both the Learning

Organization literature (c.f. Hult and Ferrell

1997), and the Organizational Learning (c.f.

Chiva-Gómez 2004, Chiva, Alegre, and

Lapiedra 2007), (Chiva, Alegre, and Lapiedra

2007). A summary of the facilitating factors is

presented below:

Table 2 Factors that facilitate learning in

organization

Digitalization of learning process

Recently, digital innovations have blossomed

due to progress in infrastructure and algorithms,

and emergence of a new generation of digital

savvies. This innovation has profound

implications for corporate management and

learning (Noruzy et al. 2013, Khin and Ho

2019, Szalavetz 2019, Schweitzer, Hand rich,

and Heidenreich 2018, Ylijoki and Porras 2016,

Camisón and Villar-López 2014, Laurell et al.

2020). Three mechanisms are to note:

improving structural performance, (cost-related

efficiency gains), enhancing relational

performance (collaboration quality across

different teams) and promoting new product

development performance (Schweitzer,

Handrich, and Heidenreich 2018). Performance

benefits are only achieved if the appropriate

conditions exist; an integrated development

environment and other tactics need to be in

place to reduce the risk of derailing innovation

practices (Szalavetz 2019).

Researchers found the use of digital platforms

for education can benefit multiple dimensions

of learning programs through; ease of access to

knowledge, emergence of a massive open

online courses, integration with industries,

global mobility of learners, competitive

landscape, objectivity of assessment, and time

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

dedicated per instructor. (Wildan Zulfikar et al.

2018, Sánchez et al. 2019).

For digital technologies to deliver,

organizations need to align digital innovation

with corporate goals, foster the right

organizational culture, build talent/roles with

the right skills on the effective appropriation of

digital instruments (Caputo et al. 2019, Vial

2019), and get leadership buy-in (Muninger,

Hammedi, and Mahr 2019, Vial 2019).

However, these digitalisation enablers have not

been integrated with the application of learning

programs. Two gaps are addressed; 1) a need

for a well-defined OLC model to help

organizations introduce and implement learning

programs cost-effectively. 2) Most of the papers

have not addressed comprehensively compiling

the facilitating factors of learning process in

organizations.

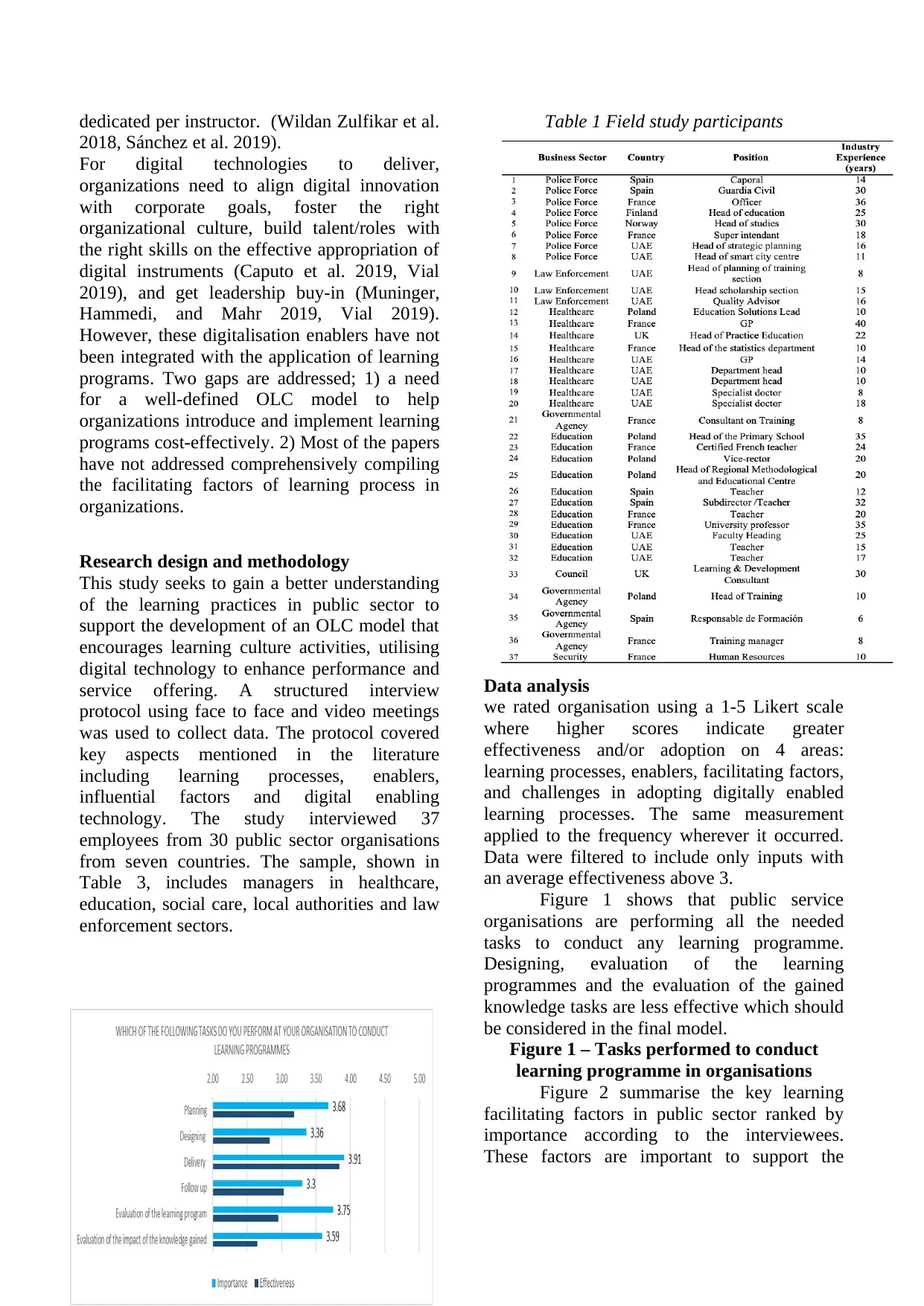

Research design and methodology

This study seeks to gain a better understanding

of the learning practices in public sector to

support the development of an OLC model that

encourages learning culture activities, utilising

digital technology to enhance performance and

service offering. A structured interview

protocol using face to face and video meetings

was used to collect data. The protocol covered

key aspects mentioned in the literature

including learning processes, enablers,

influential factors and digital enabling

technology. The study interviewed 37

employees from 30 public sector organisations

from seven countries. The sample, shown in

Table 3, includes managers in healthcare,

education, social care, local authorities and law

enforcement sectors.

Table 1 Field study participants

Data analysis

we rated organisation using a 1-5 Likert scale

where higher scores indicate greater

effectiveness and/or adoption on 4 areas:

learning processes, enablers, facilitating factors,

and challenges in adopting digitally enabled

learning processes. The same measurement

applied to the frequency wherever it occurred.

Data were filtered to include only inputs with

an average effectiveness above 3.

Figure 1 shows that public service

organisations are performing all the needed

tasks to conduct any learning programme.

Designing, evaluation of the learning

programmes and the evaluation of the gained

knowledge tasks are less effective which should

be considered in the final model.

Figure 1 – Tasks performed to conduct

learning programme in organisations

Figure 2 summarise the key learning

facilitating factors in public sector ranked by

importance according to the interviewees.

These factors are important to support the

2018, Sánchez et al. 2019).

For digital technologies to deliver,

organizations need to align digital innovation

with corporate goals, foster the right

organizational culture, build talent/roles with

the right skills on the effective appropriation of

digital instruments (Caputo et al. 2019, Vial

2019), and get leadership buy-in (Muninger,

Hammedi, and Mahr 2019, Vial 2019).

However, these digitalisation enablers have not

been integrated with the application of learning

programs. Two gaps are addressed; 1) a need

for a well-defined OLC model to help

organizations introduce and implement learning

programs cost-effectively. 2) Most of the papers

have not addressed comprehensively compiling

the facilitating factors of learning process in

organizations.

Research design and methodology

This study seeks to gain a better understanding

of the learning practices in public sector to

support the development of an OLC model that

encourages learning culture activities, utilising

digital technology to enhance performance and

service offering. A structured interview

protocol using face to face and video meetings

was used to collect data. The protocol covered

key aspects mentioned in the literature

including learning processes, enablers,

influential factors and digital enabling

technology. The study interviewed 37

employees from 30 public sector organisations

from seven countries. The sample, shown in

Table 3, includes managers in healthcare,

education, social care, local authorities and law

enforcement sectors.

Table 1 Field study participants

Data analysis

we rated organisation using a 1-5 Likert scale

where higher scores indicate greater

effectiveness and/or adoption on 4 areas:

learning processes, enablers, facilitating factors,

and challenges in adopting digitally enabled

learning processes. The same measurement

applied to the frequency wherever it occurred.

Data were filtered to include only inputs with

an average effectiveness above 3.

Figure 1 shows that public service

organisations are performing all the needed

tasks to conduct any learning programme.

Designing, evaluation of the learning

programmes and the evaluation of the gained

knowledge tasks are less effective which should

be considered in the final model.

Figure 1 – Tasks performed to conduct

learning programme in organisations

Figure 2 summarise the key learning

facilitating factors in public sector ranked by

importance according to the interviewees.

These factors are important to support the

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

execution of the different activities of the

defined learning process.

Figure 2 - Learning Processes Facilitating

Factors

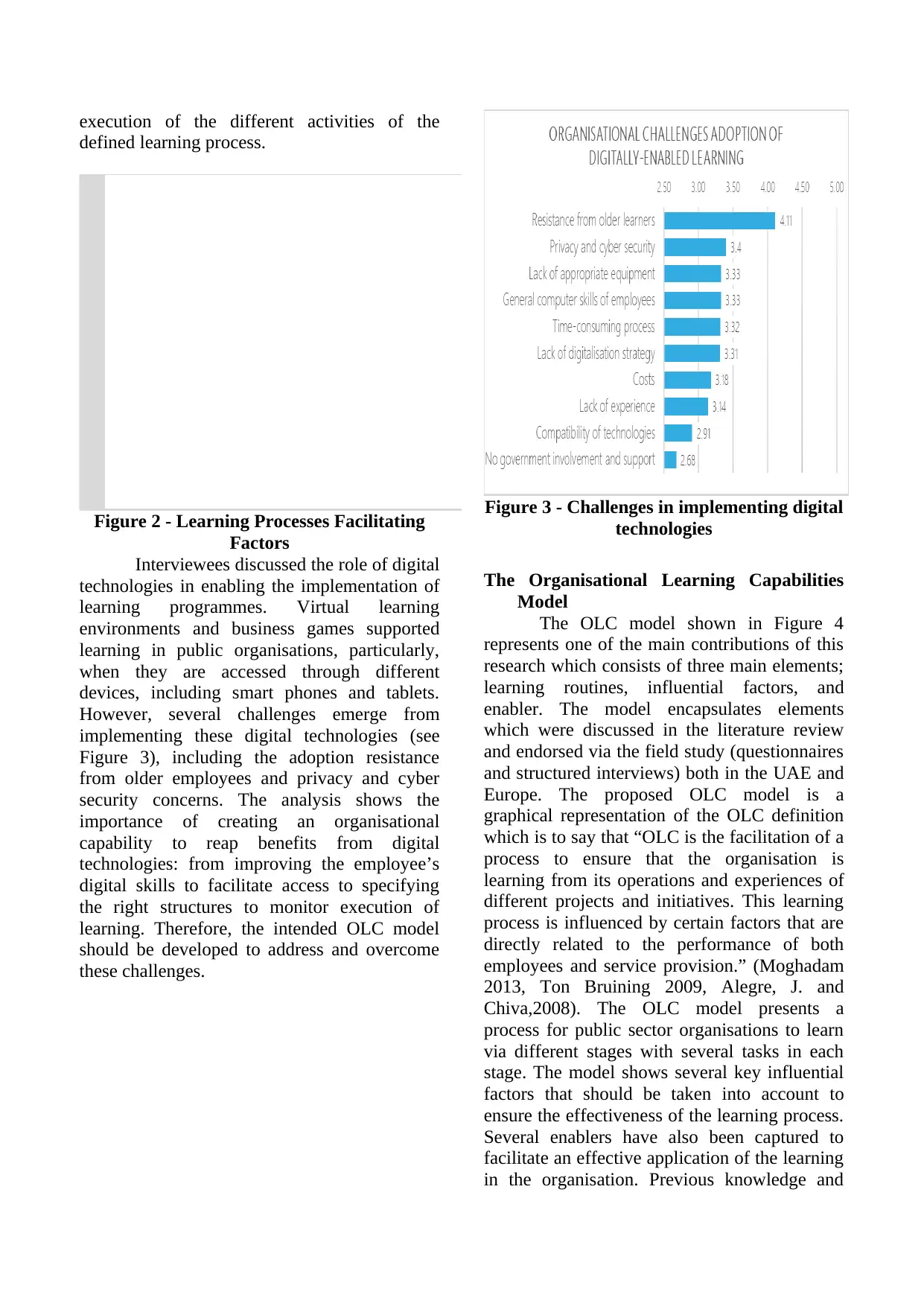

Interviewees discussed the role of digital

technologies in enabling the implementation of

learning programmes. Virtual learning

environments and business games supported

learning in public organisations, particularly,

when they are accessed through different

devices, including smart phones and tablets.

However, several challenges emerge from

implementing these digital technologies (see

Figure 3), including the adoption resistance

from older employees and privacy and cyber

security concerns. The analysis shows the

importance of creating an organisational

capability to reap benefits from digital

technologies: from improving the employee’s

digital skills to facilitate access to specifying

the right structures to monitor execution of

learning. Therefore, the intended OLC model

should be developed to address and overcome

these challenges.

Figure 3 - Challenges in implementing digital

technologies

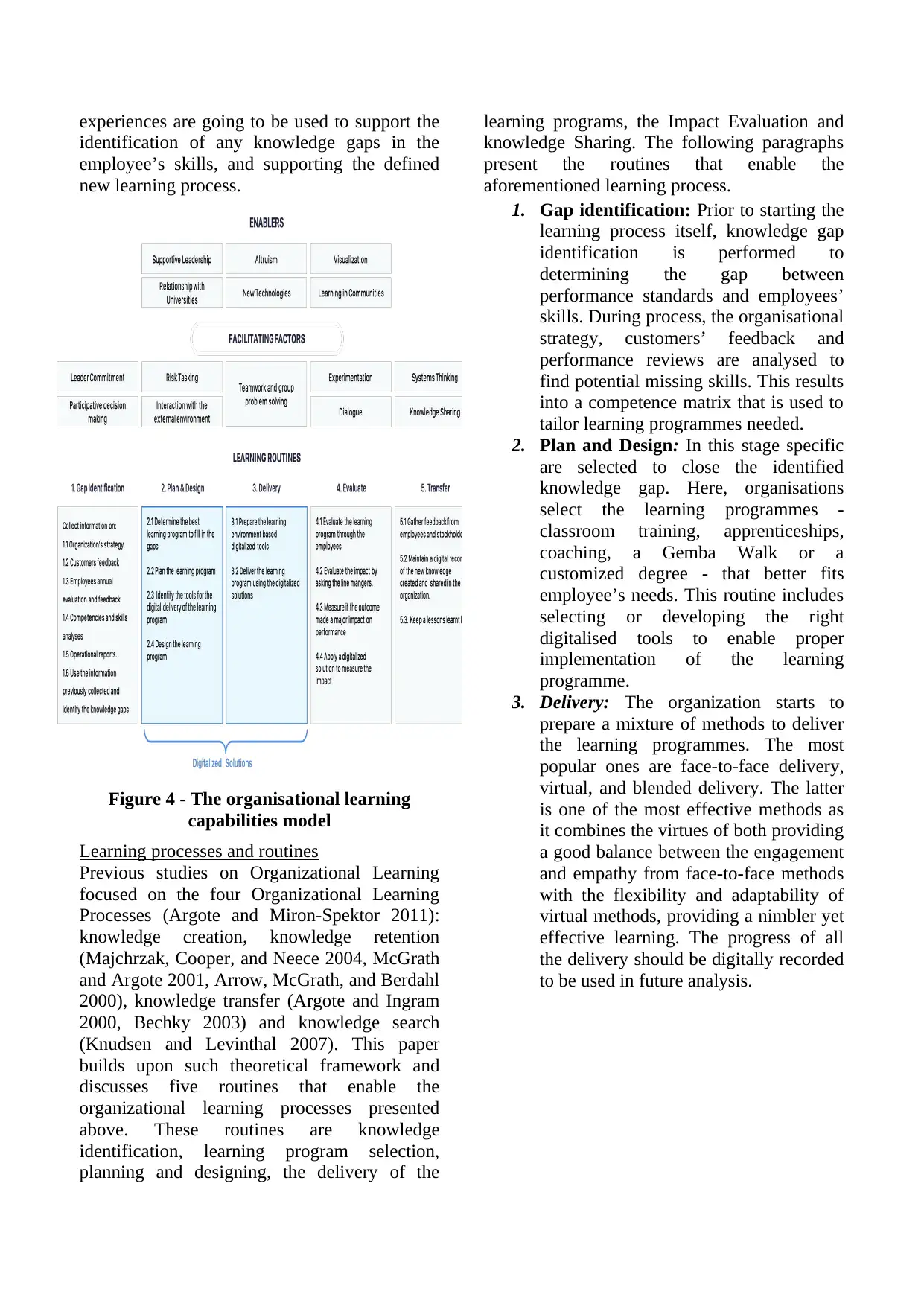

The Organisational Learning Capabilities

Model

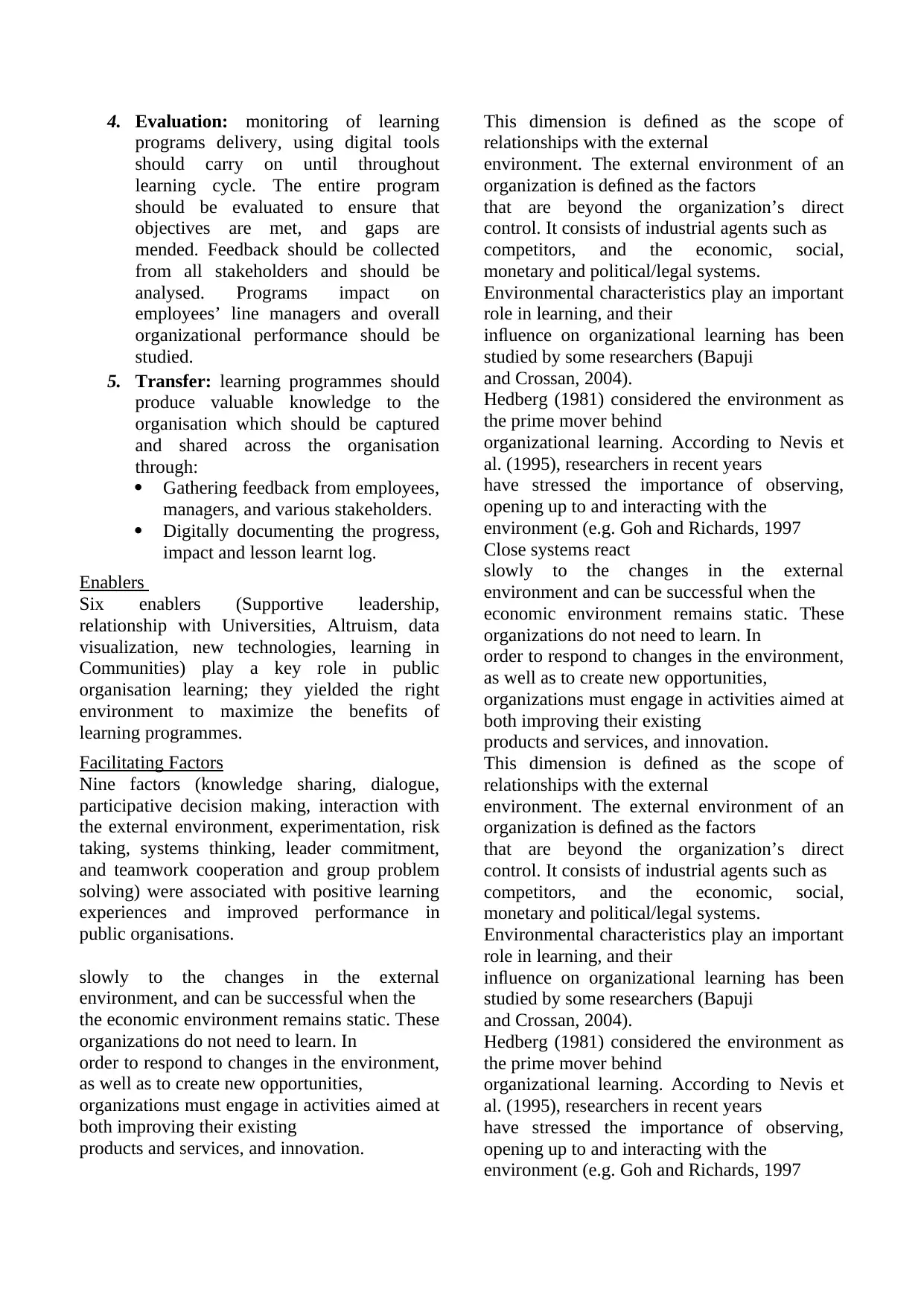

The OLC model shown in Figure 4

represents one of the main contributions of this

research which consists of three main elements;

learning routines, influential factors, and

enabler. The model encapsulates elements

which were discussed in the literature review

and endorsed via the field study (questionnaires

and structured interviews) both in the UAE and

Europe. The proposed OLC model is a

graphical representation of the OLC definition

which is to say that “OLC is the facilitation of a

process to ensure that the organisation is

learning from its operations and experiences of

different projects and initiatives. This learning

process is influenced by certain factors that are

directly related to the performance of both

employees and service provision.” (Moghadam

2013, Ton Bruining 2009, Alegre, J. and

Chiva,2008). The OLC model presents a

process for public sector organisations to learn

via different stages with several tasks in each

stage. The model shows several key influential

factors that should be taken into account to

ensure the effectiveness of the learning process.

Several enablers have also been captured to

facilitate an effective application of the learning

in the organisation. Previous knowledge and

defined learning process.

Figure 2 - Learning Processes Facilitating

Factors

Interviewees discussed the role of digital

technologies in enabling the implementation of

learning programmes. Virtual learning

environments and business games supported

learning in public organisations, particularly,

when they are accessed through different

devices, including smart phones and tablets.

However, several challenges emerge from

implementing these digital technologies (see

Figure 3), including the adoption resistance

from older employees and privacy and cyber

security concerns. The analysis shows the

importance of creating an organisational

capability to reap benefits from digital

technologies: from improving the employee’s

digital skills to facilitate access to specifying

the right structures to monitor execution of

learning. Therefore, the intended OLC model

should be developed to address and overcome

these challenges.

Figure 3 - Challenges in implementing digital

technologies

The Organisational Learning Capabilities

Model

The OLC model shown in Figure 4

represents one of the main contributions of this

research which consists of three main elements;

learning routines, influential factors, and

enabler. The model encapsulates elements

which were discussed in the literature review

and endorsed via the field study (questionnaires

and structured interviews) both in the UAE and

Europe. The proposed OLC model is a

graphical representation of the OLC definition

which is to say that “OLC is the facilitation of a

process to ensure that the organisation is

learning from its operations and experiences of

different projects and initiatives. This learning

process is influenced by certain factors that are

directly related to the performance of both

employees and service provision.” (Moghadam

2013, Ton Bruining 2009, Alegre, J. and

Chiva,2008). The OLC model presents a

process for public sector organisations to learn

via different stages with several tasks in each

stage. The model shows several key influential

factors that should be taken into account to

ensure the effectiveness of the learning process.

Several enablers have also been captured to

facilitate an effective application of the learning

in the organisation. Previous knowledge and

experiences are going to be used to support the

identification of any knowledge gaps in the

employee’s skills, and supporting the defined

new learning process.

Figure 4 - The organisational learning

capabilities model

Learning processes and routines

Previous studies on Organizational Learning

focused on the four Organizational Learning

Processes (Argote and Miron-Spektor 2011):

knowledge creation, knowledge retention

(Majchrzak, Cooper, and Neece 2004, McGrath

and Argote 2001, Arrow, McGrath, and Berdahl

2000), knowledge transfer (Argote and Ingram

2000, Bechky 2003) and knowledge search

(Knudsen and Levinthal 2007). This paper

builds upon such theoretical framework and

discusses five routines that enable the

organizational learning processes presented

above. These routines are knowledge

identification, learning program selection,

planning and designing, the delivery of the

learning programs, the Impact Evaluation and

knowledge Sharing. The following paragraphs

present the routines that enable the

aforementioned learning process.

1. Gap identification: Prior to starting the

learning process itself, knowledge gap

identification is performed to

determining the gap between

performance standards and employees’

skills. During process, the organisational

strategy, customers’ feedback and

performance reviews are analysed to

find potential missing skills. This results

into a competence matrix that is used to

tailor learning programmes needed.

2. Plan and Design: In this stage specific

are selected to close the identified

knowledge gap. Here, organisations

select the learning programmes -

classroom training, apprenticeships,

coaching, a Gemba Walk or a

customized degree - that better fits

employee’s needs. This routine includes

selecting or developing the right

digitalised tools to enable proper

implementation of the learning

programme.

3. Delivery: The organization starts to

prepare a mixture of methods to deliver

the learning programmes. The most

popular ones are face-to-face delivery,

virtual, and blended delivery. The latter

is one of the most effective methods as

it combines the virtues of both providing

a good balance between the engagement

and empathy from face-to-face methods

with the flexibility and adaptability of

virtual methods, providing a nimbler yet

effective learning. The progress of all

the delivery should be digitally recorded

to be used in future analysis.

identification of any knowledge gaps in the

employee’s skills, and supporting the defined

new learning process.

Figure 4 - The organisational learning

capabilities model

Learning processes and routines

Previous studies on Organizational Learning

focused on the four Organizational Learning

Processes (Argote and Miron-Spektor 2011):

knowledge creation, knowledge retention

(Majchrzak, Cooper, and Neece 2004, McGrath

and Argote 2001, Arrow, McGrath, and Berdahl

2000), knowledge transfer (Argote and Ingram

2000, Bechky 2003) and knowledge search

(Knudsen and Levinthal 2007). This paper

builds upon such theoretical framework and

discusses five routines that enable the

organizational learning processes presented

above. These routines are knowledge

identification, learning program selection,

planning and designing, the delivery of the

learning programs, the Impact Evaluation and

knowledge Sharing. The following paragraphs

present the routines that enable the

aforementioned learning process.

1. Gap identification: Prior to starting the

learning process itself, knowledge gap

identification is performed to

determining the gap between

performance standards and employees’

skills. During process, the organisational

strategy, customers’ feedback and

performance reviews are analysed to

find potential missing skills. This results

into a competence matrix that is used to

tailor learning programmes needed.

2. Plan and Design: In this stage specific

are selected to close the identified

knowledge gap. Here, organisations

select the learning programmes -

classroom training, apprenticeships,

coaching, a Gemba Walk or a

customized degree - that better fits

employee’s needs. This routine includes

selecting or developing the right

digitalised tools to enable proper

implementation of the learning

programme.

3. Delivery: The organization starts to

prepare a mixture of methods to deliver

the learning programmes. The most

popular ones are face-to-face delivery,

virtual, and blended delivery. The latter

is one of the most effective methods as

it combines the virtues of both providing

a good balance between the engagement

and empathy from face-to-face methods

with the flexibility and adaptability of

virtual methods, providing a nimbler yet

effective learning. The progress of all

the delivery should be digitally recorded

to be used in future analysis.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4. Evaluation: monitoring of learning

programs delivery, using digital tools

should carry on until throughout

learning cycle. The entire program

should be evaluated to ensure that

objectives are met, and gaps are

mended. Feedback should be collected

from all stakeholders and should be

analysed. Programs impact on

employees’ line managers and overall

organizational performance should be

studied.

5. Transfer: learning programmes should

produce valuable knowledge to the

organisation which should be captured

and shared across the organisation

through:

Gathering feedback from employees,

managers, and various stakeholders.

Digitally documenting the progress,

impact and lesson learnt log.

Enablers

Six enablers (Supportive leadership,

relationship with Universities, Altruism, data

visualization, new technologies, learning in

Communities) play a key role in public

organisation learning; they yielded the right

environment to maximize the benefits of

learning programmes.

Facilitating Factors

Nine factors (knowledge sharing, dialogue,

participative decision making, interaction with

the external environment, experimentation, risk

taking, systems thinking, leader commitment,

and teamwork cooperation and group problem

solving) were associated with positive learning

experiences and improved performance in

public organisations.

slowly to the changes in the external

environment, and can be successful when the

the economic environment remains static. These

organizations do not need to learn. In

order to respond to changes in the environment,

as well as to create new opportunities,

organizations must engage in activities aimed at

both improving their existing

products and services, and innovation.

This dimension is defined as the scope of

relationships with the external

environment. The external environment of an

organization is defined as the factors

that are beyond the organization’s direct

control. It consists of industrial agents such as

competitors, and the economic, social,

monetary and political/legal systems.

Environmental characteristics play an important

role in learning, and their

influence on organizational learning has been

studied by some researchers (Bapuji

and Crossan, 2004).

Hedberg (1981) considered the environment as

the prime mover behind

organizational learning. According to Nevis et

al. (1995), researchers in recent years

have stressed the importance of observing,

opening up to and interacting with the

environment (e.g. Goh and Richards, 1997

Close systems react

slowly to the changes in the external

environment and can be successful when the

economic environment remains static. These

organizations do not need to learn. In

order to respond to changes in the environment,

as well as to create new opportunities,

organizations must engage in activities aimed at

both improving their existing

products and services, and innovation.

This dimension is defined as the scope of

relationships with the external

environment. The external environment of an

organization is defined as the factors

that are beyond the organization’s direct

control. It consists of industrial agents such as

competitors, and the economic, social,

monetary and political/legal systems.

Environmental characteristics play an important

role in learning, and their

influence on organizational learning has been

studied by some researchers (Bapuji

and Crossan, 2004).

Hedberg (1981) considered the environment as

the prime mover behind

organizational learning. According to Nevis et

al. (1995), researchers in recent years

have stressed the importance of observing,

opening up to and interacting with the

environment (e.g. Goh and Richards, 1997

programs delivery, using digital tools

should carry on until throughout

learning cycle. The entire program

should be evaluated to ensure that

objectives are met, and gaps are

mended. Feedback should be collected

from all stakeholders and should be

analysed. Programs impact on

employees’ line managers and overall

organizational performance should be

studied.

5. Transfer: learning programmes should

produce valuable knowledge to the

organisation which should be captured

and shared across the organisation

through:

Gathering feedback from employees,

managers, and various stakeholders.

Digitally documenting the progress,

impact and lesson learnt log.

Enablers

Six enablers (Supportive leadership,

relationship with Universities, Altruism, data

visualization, new technologies, learning in

Communities) play a key role in public

organisation learning; they yielded the right

environment to maximize the benefits of

learning programmes.

Facilitating Factors

Nine factors (knowledge sharing, dialogue,

participative decision making, interaction with

the external environment, experimentation, risk

taking, systems thinking, leader commitment,

and teamwork cooperation and group problem

solving) were associated with positive learning

experiences and improved performance in

public organisations.

slowly to the changes in the external

environment, and can be successful when the

the economic environment remains static. These

organizations do not need to learn. In

order to respond to changes in the environment,

as well as to create new opportunities,

organizations must engage in activities aimed at

both improving their existing

products and services, and innovation.

This dimension is defined as the scope of

relationships with the external

environment. The external environment of an

organization is defined as the factors

that are beyond the organization’s direct

control. It consists of industrial agents such as

competitors, and the economic, social,

monetary and political/legal systems.

Environmental characteristics play an important

role in learning, and their

influence on organizational learning has been

studied by some researchers (Bapuji

and Crossan, 2004).

Hedberg (1981) considered the environment as

the prime mover behind

organizational learning. According to Nevis et

al. (1995), researchers in recent years

have stressed the importance of observing,

opening up to and interacting with the

environment (e.g. Goh and Richards, 1997

Close systems react

slowly to the changes in the external

environment and can be successful when the

economic environment remains static. These

organizations do not need to learn. In

order to respond to changes in the environment,

as well as to create new opportunities,

organizations must engage in activities aimed at

both improving their existing

products and services, and innovation.

This dimension is defined as the scope of

relationships with the external

environment. The external environment of an

organization is defined as the factors

that are beyond the organization’s direct

control. It consists of industrial agents such as

competitors, and the economic, social,

monetary and political/legal systems.

Environmental characteristics play an important

role in learning, and their

influence on organizational learning has been

studied by some researchers (Bapuji

and Crossan, 2004).

Hedberg (1981) considered the environment as

the prime mover behind

organizational learning. According to Nevis et

al. (1995), researchers in recent years

have stressed the importance of observing,

opening up to and interacting with the

environment (e.g. Goh and Richards, 1997

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Close systems react

slowly to the changes in the external

environment and can be successful when the

economic environment remains static. These

organizations do not need to learn. In

order to respond to changes in the environment,

as well as to create new opportunities,

organizations must engage in activities aimed at

both improving their existing

products and services, and innovation.

This dimension is defined as the scope of

relationships with the external

environment. The external environment of an

organization is defined as the factors

that are beyond the organization’s direct

control. It consists of industrial agents such as

competitors, and the economic, social,

monetary and political/legal systems.

Environmental characteristics play an important

role in learning, and their

influence on organizational learning has been

studied by some researchers (Bapuji

and Crossan, 2004).

Hedberg (1981) considered the environment as

the prime mover behind

organizational learning. According to Nevis et

al. (1995), researchers in recent years

have stressed on the importance of observing,

opening up to and interacting with the

environment (e.g. Goh and Richards,

1997Teamwork cooperation and group

problem solving: Teams play a crucial role in

organizational learning; they are the focus of

interaction between the individual and the

organisation, and consequently, constitute the

basis of learning and execution. Coherent and

effective teams bring knowledge and experience

together, helping to solve problems effectively

and boost performance.

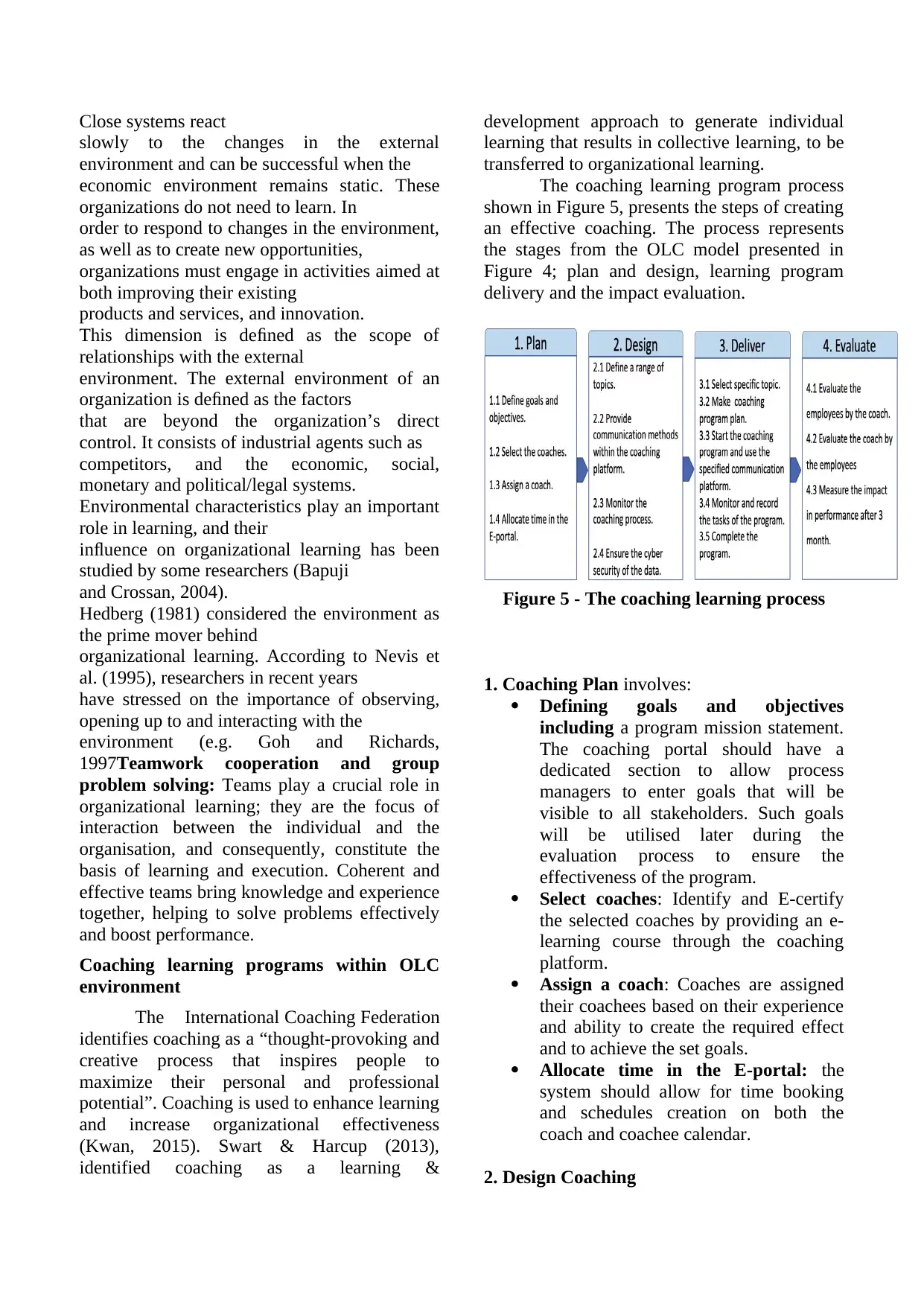

Coaching learning programs within OLC

environment

The International Coaching Federation

identifies coaching as a “thought-provoking and

creative process that inspires people to

maximize their personal and professional

potential”. Coaching is used to enhance learning

and increase organizational effectiveness

(Kwan, 2015). Swart & Harcup (2013),

identified coaching as a learning &

development approach to generate individual

learning that results in collective learning, to be

transferred to organizational learning.

The coaching learning program process

shown in Figure 5, presents the steps of creating

an effective coaching. The process represents

the stages from the OLC model presented in

Figure 4; plan and design, learning program

delivery and the impact evaluation.

Figure 5 - The coaching learning process

1. Coaching Plan involves:

Defining goals and objectives

including a program mission statement.

The coaching portal should have a

dedicated section to allow process

managers to enter goals that will be

visible to all stakeholders. Such goals

will be utilised later during the

evaluation process to ensure the

effectiveness of the program.

Select coaches: Identify and E-certify

the selected coaches by providing an e-

learning course through the coaching

platform.

Assign a coach: Coaches are assigned

their coachees based on their experience

and ability to create the required effect

and to achieve the set goals.

Allocate time in the E-portal: the

system should allow for time booking

and schedules creation on both the

coach and coachee calendar.

2. Design Coaching

slowly to the changes in the external

environment and can be successful when the

economic environment remains static. These

organizations do not need to learn. In

order to respond to changes in the environment,

as well as to create new opportunities,

organizations must engage in activities aimed at

both improving their existing

products and services, and innovation.

This dimension is defined as the scope of

relationships with the external

environment. The external environment of an

organization is defined as the factors

that are beyond the organization’s direct

control. It consists of industrial agents such as

competitors, and the economic, social,

monetary and political/legal systems.

Environmental characteristics play an important

role in learning, and their

influence on organizational learning has been

studied by some researchers (Bapuji

and Crossan, 2004).

Hedberg (1981) considered the environment as

the prime mover behind

organizational learning. According to Nevis et

al. (1995), researchers in recent years

have stressed on the importance of observing,

opening up to and interacting with the

environment (e.g. Goh and Richards,

1997Teamwork cooperation and group

problem solving: Teams play a crucial role in

organizational learning; they are the focus of

interaction between the individual and the

organisation, and consequently, constitute the

basis of learning and execution. Coherent and

effective teams bring knowledge and experience

together, helping to solve problems effectively

and boost performance.

Coaching learning programs within OLC

environment

The International Coaching Federation

identifies coaching as a “thought-provoking and

creative process that inspires people to

maximize their personal and professional

potential”. Coaching is used to enhance learning

and increase organizational effectiveness

(Kwan, 2015). Swart & Harcup (2013),

identified coaching as a learning &

development approach to generate individual

learning that results in collective learning, to be

transferred to organizational learning.

The coaching learning program process

shown in Figure 5, presents the steps of creating

an effective coaching. The process represents

the stages from the OLC model presented in

Figure 4; plan and design, learning program

delivery and the impact evaluation.

Figure 5 - The coaching learning process

1. Coaching Plan involves:

Defining goals and objectives

including a program mission statement.

The coaching portal should have a

dedicated section to allow process

managers to enter goals that will be

visible to all stakeholders. Such goals

will be utilised later during the

evaluation process to ensure the

effectiveness of the program.

Select coaches: Identify and E-certify

the selected coaches by providing an e-

learning course through the coaching

platform.

Assign a coach: Coaches are assigned

their coachees based on their experience

and ability to create the required effect

and to achieve the set goals.

Allocate time in the E-portal: the

system should allow for time booking

and schedules creation on both the

coach and coachee calendar.

2. Design Coaching

Organisations should have an inventory

of coaching topics as a result of the learning

needs analysis. Such topics are organised within

the coaching portal. Once coaching goals are set

for an individual, certain topics get selected to

be the focus of coaching. The digitalised portal

offers various ways of communicating such as

emails, video webinars. This also applies to

“face-to-face coaching” as the platform can be

used to keep schedules and book venues for

meetings. The progress can be monitored

regularly and automatically through the digital

portal.

3. Delivering Coaching

The coach should set the coaching plan and

start the coaching. All steps of delivery should

be documented through the digital portal.

Program managers should continuously ensure

the usage of the coaching portal and ensure that

coaching progress is as desired. When the

programme ends reports could be issued and

preparation for the final evaluation stage should

start.

4. Coaching Evaluation:

The evaluation process involves:

I. Evaluation of the employees by the

coach: The coach evaluates coachees

using the coaching management portal

thought a function normally called

progress tracking. Progress tracking will

allow the coach to review the progress

notes and steps and to fill in the required

data electronically.

II. Evaluation of the coach by the

employees: Evaluators via the

digitalised portal should be able to share

the evaluation forms with the coaches.

This data should be analysed to measure

the effectiveness and the performance of

the coach.

III. Measure the impact in performance:

the impact of the programs will be

measured after a set period (for example

3 months) to ensure that the program is

consistent with the set objectives. This

will be done by contacting the coachees’

line mangers and measuring the

improvements in the productivity and

strategic KPIs of their unites.

4 Conclusion

Public sector organisations are keen to improve

the skills of their employees. The traditional

approach of providing mainly training is not

good anymore. Therefore, public sector

organisations are considering different learning

programs such as coaching, mentoring etc. This

study suggests that OLC is the right approach to

boost the learning as OLC facilitates the

learning process. The proposed OLC model

consists of the key elements that represent the

definition of OLC; these are the learning

processes, enablers, influential factors and the

enabling technologies. The OLC model helps to

define all other learning programs where the

coaching learning program is presented in this

paper. A digitised software demonstrator is

being developed based on the tasks of the

coaching learning programme process. The

digitised software demonstrator will be used in

a case study in a public service organisation as a

future work.

References:

[1] Alegre, J. and Chiva, R. (2008) ‘Assessing

the Impact of Organizational Learning

Capability on Product Innovation

Performance: An Empirical Test’.

Technovation 28, 315–326

[2] Argote, L. and Ingram, P. (2000)

‘Knowledge Transfer: A Basis for

Competitive Advantage in Firms’.

Organizational Behavior and Human

Decision Processes 82 (1), 150–169

[3] Argote, L. and Miron-Spektor, E. (2011)

‘Organizational Learning: From Experience

to Knowledge’. Organization Science 22

(5), 1123–1137

[4] Arrow, H., McGrath, J.E., and Berdahl, J.L.

(2000) Small Groups as Complex Systems:

Formation, Coordination, Development, and

Adaptation. Sage Publications

of coaching topics as a result of the learning

needs analysis. Such topics are organised within

the coaching portal. Once coaching goals are set

for an individual, certain topics get selected to

be the focus of coaching. The digitalised portal

offers various ways of communicating such as

emails, video webinars. This also applies to

“face-to-face coaching” as the platform can be

used to keep schedules and book venues for

meetings. The progress can be monitored

regularly and automatically through the digital

portal.

3. Delivering Coaching

The coach should set the coaching plan and

start the coaching. All steps of delivery should

be documented through the digital portal.

Program managers should continuously ensure

the usage of the coaching portal and ensure that

coaching progress is as desired. When the

programme ends reports could be issued and

preparation for the final evaluation stage should

start.

4. Coaching Evaluation:

The evaluation process involves:

I. Evaluation of the employees by the

coach: The coach evaluates coachees

using the coaching management portal

thought a function normally called

progress tracking. Progress tracking will

allow the coach to review the progress

notes and steps and to fill in the required

data electronically.

II. Evaluation of the coach by the

employees: Evaluators via the

digitalised portal should be able to share

the evaluation forms with the coaches.

This data should be analysed to measure

the effectiveness and the performance of

the coach.

III. Measure the impact in performance:

the impact of the programs will be

measured after a set period (for example

3 months) to ensure that the program is

consistent with the set objectives. This

will be done by contacting the coachees’

line mangers and measuring the

improvements in the productivity and

strategic KPIs of their unites.

4 Conclusion

Public sector organisations are keen to improve

the skills of their employees. The traditional

approach of providing mainly training is not

good anymore. Therefore, public sector

organisations are considering different learning

programs such as coaching, mentoring etc. This

study suggests that OLC is the right approach to

boost the learning as OLC facilitates the

learning process. The proposed OLC model

consists of the key elements that represent the

definition of OLC; these are the learning

processes, enablers, influential factors and the

enabling technologies. The OLC model helps to

define all other learning programs where the

coaching learning program is presented in this

paper. A digitised software demonstrator is

being developed based on the tasks of the

coaching learning programme process. The

digitised software demonstrator will be used in

a case study in a public service organisation as a

future work.

References:

[1] Alegre, J. and Chiva, R. (2008) ‘Assessing

the Impact of Organizational Learning

Capability on Product Innovation

Performance: An Empirical Test’.

Technovation 28, 315–326

[2] Argote, L. and Ingram, P. (2000)

‘Knowledge Transfer: A Basis for

Competitive Advantage in Firms’.

Organizational Behavior and Human

Decision Processes 82 (1), 150–169

[3] Argote, L. and Miron-Spektor, E. (2011)

‘Organizational Learning: From Experience

to Knowledge’. Organization Science 22

(5), 1123–1137

[4] Arrow, H., McGrath, J.E., and Berdahl, J.L.

(2000) Small Groups as Complex Systems:

Formation, Coordination, Development, and

Adaptation. Sage Publications

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

[5] Bak, O. (2012) ‘Universities: Can They Be

Considered as Learning Organizations?’

The Learning Organization

[6] Bechky, B.A. (2003) ‘Sharing Meaning

across Occupational Communities: The

Transformation of Understanding on a

Production Floor’. Organization Science 14

(3), 312–330

[7] Bontis, N., Crossan, M.M., and Hulland, J.

(2002) ‘Managing an Organizational

Learning System by Aligning Stocks and

Flows’. Journal of Management Studies 4

[8] Caldwell, R. (2012a) ‘Leadership and

Learning: A Critical Reexamination of

Senge’s Learning Organization’. Systemic

Practice and Action Research 25 (1), 39–55

[9] Caldwell, R. (2012b) ‘Systems Thinking,

Organizational Change and Agency: A

Practice Theory Critique of Senge’s

Learning Organization’. Journal of Change

Management 12 (2), 145–164

[10] Camisón, C. and Villar-López, A.

(2014) ‘Organizational Innovation as an

Enabler of Technological Innovation

Capabilities and Firm Performance’. Journal

of Business Research [online] 67 (1), 2891–

2902. available from

<http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.06

.004>

[11] Caputo, F., Cillo, V., Candelo, E.,

and Liu, Y. (2019) ‘Innovating through

Digital Revolution’. Management Decision

57 (8), 2032–2051

[12] Chiva-Gómez, R. (2004) ‘The

Facilitating Factors for Organizational

Learning in the Ceramic Sector’. Human

Resource Development International 7 (2),

233–249

[13] Chiva, R., Alegre, J., and Lapiedra,

R. (2007) ‘Measuring Organisational

Learning Capability among the Workforce’.

International Journal of Manpower 28, 224–

242

[14] Çömlek, O., Kitapçı, H., Çelik, V.,

and Özşahin, M. (2012) ‘The Effects of

Organizational Learning Capacity on Firm

Innovative Performance’. Procedia - Social

and Behavioral Sciences 41, 367–374

[15] Crossan, M.M., Lane, H.W., and

White, R.E. (1999) ‘An Organizational

Learning Framework: From Intuition to

Institution’. Academy of Management

Review 24 (3), 522–537

[16] Deniz, S., Cimen, M., and Kaya, S.

(2017) ‘Determining Organizational

Learning Capability: A Study in Private

Health Care Organizations’. International

Journal of Research Foundation of Hospital

and Health Care Administration 5, 1–7

[17] Edmondson, A.C. (2012) Teaming:

How Organizations Learn, Innovate, and

Compete in the Knowledge Economy. John

Wiley & Sons

[18] García-Morales, V.J., Jiménez-

Barrionuevo, M.M., and Gutiérrez-

Gutiérrez, L. (2012) ‘Transformational

Leadership Influence on Organizational

Performance through Organizational

Learning and Innovation’. Journal of

Business Research [online] 65 (7), 1040–

1050. available from

<http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.03

.005>

[19] Garvin, D. (1993) ‘A (1993).

Building a Learning Organization’. Harvard

Business Review 78–91

[20] Glaveski, S. (2019) ‘Where

Companies Go Wrong with Learning and

Development’. Harvard Business Review

[online] 1–7. available from

<https://hbr.org/2019/10/where-companies-

go-wrong-with-learning-and-development>

[30 April 2020]

[21] Goh, S. and Richards, G. (1997)

‘Benchmarking the Learning Capability of

Organizations’. European Management

Journal 15 (5), 575–583

[22] Goh, S.C. (2003) ‘Improving

Organizational Learning Capability:

Lessons from Two Case Studies’. The

Learning Organization 10 (4), 216–227

Considered as Learning Organizations?’

The Learning Organization

[6] Bechky, B.A. (2003) ‘Sharing Meaning

across Occupational Communities: The

Transformation of Understanding on a

Production Floor’. Organization Science 14

(3), 312–330

[7] Bontis, N., Crossan, M.M., and Hulland, J.

(2002) ‘Managing an Organizational

Learning System by Aligning Stocks and

Flows’. Journal of Management Studies 4

[8] Caldwell, R. (2012a) ‘Leadership and

Learning: A Critical Reexamination of

Senge’s Learning Organization’. Systemic

Practice and Action Research 25 (1), 39–55

[9] Caldwell, R. (2012b) ‘Systems Thinking,

Organizational Change and Agency: A

Practice Theory Critique of Senge’s

Learning Organization’. Journal of Change

Management 12 (2), 145–164

[10] Camisón, C. and Villar-López, A.

(2014) ‘Organizational Innovation as an

Enabler of Technological Innovation

Capabilities and Firm Performance’. Journal

of Business Research [online] 67 (1), 2891–

2902. available from

<http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.06

.004>

[11] Caputo, F., Cillo, V., Candelo, E.,

and Liu, Y. (2019) ‘Innovating through

Digital Revolution’. Management Decision

57 (8), 2032–2051

[12] Chiva-Gómez, R. (2004) ‘The

Facilitating Factors for Organizational

Learning in the Ceramic Sector’. Human

Resource Development International 7 (2),

233–249

[13] Chiva, R., Alegre, J., and Lapiedra,

R. (2007) ‘Measuring Organisational

Learning Capability among the Workforce’.

International Journal of Manpower 28, 224–

242

[14] Çömlek, O., Kitapçı, H., Çelik, V.,

and Özşahin, M. (2012) ‘The Effects of

Organizational Learning Capacity on Firm

Innovative Performance’. Procedia - Social

and Behavioral Sciences 41, 367–374

[15] Crossan, M.M., Lane, H.W., and

White, R.E. (1999) ‘An Organizational

Learning Framework: From Intuition to

Institution’. Academy of Management

Review 24 (3), 522–537

[16] Deniz, S., Cimen, M., and Kaya, S.

(2017) ‘Determining Organizational

Learning Capability: A Study in Private

Health Care Organizations’. International

Journal of Research Foundation of Hospital

and Health Care Administration 5, 1–7

[17] Edmondson, A.C. (2012) Teaming:

How Organizations Learn, Innovate, and

Compete in the Knowledge Economy. John

Wiley & Sons

[18] García-Morales, V.J., Jiménez-

Barrionuevo, M.M., and Gutiérrez-

Gutiérrez, L. (2012) ‘Transformational

Leadership Influence on Organizational

Performance through Organizational

Learning and Innovation’. Journal of

Business Research [online] 65 (7), 1040–

1050. available from

<http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.03

.005>

[19] Garvin, D. (1993) ‘A (1993).

Building a Learning Organization’. Harvard

Business Review 78–91

[20] Glaveski, S. (2019) ‘Where

Companies Go Wrong with Learning and

Development’. Harvard Business Review

[online] 1–7. available from

<https://hbr.org/2019/10/where-companies-

go-wrong-with-learning-and-development>

[30 April 2020]

[21] Goh, S. and Richards, G. (1997)

‘Benchmarking the Learning Capability of

Organizations’. European Management

Journal 15 (5), 575–583

[22] Goh, S.C. (2003) ‘Improving

Organizational Learning Capability:

Lessons from Two Case Studies’. The

Learning Organization 10 (4), 216–227

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

[23] Goh, S.C. and Ryan, P.J. (2002)

Learning Capability, Organization Factors

and Firm Performance. 52, 1–5

[24] Gomes, G. and Wojahn, R.M.

(2017) ‘Organizational Learning Capability,

Innovation and Performance: Study in

Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises

(SMES)’. Revista de Administração 52,

163–175

[25] Haho, P. (2014) Learning Enablers,

Learning Outcomes, Learning Paths, and

Their Relationships in Organizational

Learning and Change.

[26] Hazlett, S.A., McAdam, R., and

Beggs, V. (2008) ‘An Exploratory Study of

Knowledge Flows: A Case Study of Public

Sector Procurement’. Total Quality

Management and Business Excellence 19,

57–66

[27] Holweg, M., Davies, J., De Meyer,

A., Lawson, B., and Schmenner, R.W.

(2018) ‘Improving Processes’. in Process

Theory: The Principles of Operations

Management. 167–192

[28] Hult, G.T.M. and Ferrell, O.C.

(1997) ‘Global Organizational Learning

Capacity in Purchasing: Construct and

Measurement’. Journal of Business

Research 40 (2), 97–111

[29] Isaacs, W.N. (1993) ‘Taking Flight:

Dialogue, Collective Thinking, and

Organizational Learning’. Organizational

Dynamics 22 (2), 24–39

[30] Jerez-Gómez, P., Céspedes-Lorente,

J., and Valle-Cabrera, R. (2005)

‘Organizational Learning Capability: A

Proposal of Measurement’. Journal of

Business Research 58 (6), 715–725

[31] Jerez Gómez, P., Céspedes Lorente,

J.J., and Valle Cabrera, R. (2004) ‘Training

Practices and Organisational Learning

Capability’. Journal of European Industrial

Training 28, 234–256

[32] Jiménez-Jiménez, D. and Sanz-

Valle, R. (2011) ‘Innovation, Organizational

Learning, and Performance’. Journal of

Business Research [online] 64 (4), 408–417.

available from

<http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.09

.010>

[33] Khalib, L.H., Kassim, N.A., and

Ghazali, F.I. (2015) ‘Organizational

Learning Capabilities ( OLC ) toward Job

Satisfaction : A Conceptual Framework’.

Academic Research International 6, 169–

180

[34] Khin, S. and Ho, T.C.F. (2019)

‘Digital Technology, Digital Capability and

Organizational Performance: A Mediating

Role of Digital Innovation’. International

Journal of Innovation Science 11 (2), 177–

195

[35] Knudsen, T. and Levinthal, D.A.

(2007) ‘Two Faces of Search: Alternative

Generation and Alternative Evaluation’.

Organization Science [online] 18 (1), 39–

54. available from

<http://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1

287/orsc.1060.0216>

[36] Laurell, C., Sandström, C.,

Eriksson, K., and Nykvist, R. (2020)

‘Digitalization and the Future of

Management Learning: New Technology as

an Enabler of Historical, Practice-Oriented,

and Critical Perspectives in Management

Research and Learning’. Management

Learning 51 (1), 89–108

[37] Lawrence, T.B., Mauws, M.K.,

Dyck, B., and Kleysen, R.F. (2005) ‘The

Politics of Organizational Learning:

Integrating Power into the 4I Framework’.

Academy of Management Review 30 (1),

180–191

[38] Leonard‐Barton, D. (1992) ‘Core

Capabilities and Core Rigidities: A Paradox

in Managing New Product Development’.

Strategic Management Journal 13 (S1),

111–125

[39] Levinthal, D.A. and March, J.G.

(1993) ‘The Myopia of Learning’. Strategic

Management Journal 14 (2 S), 95–112

[40] Majchrzak, A., Cooper, L.P., and

Neece, O.E. (2004) ‘Knowledge Reuse for

Learning Capability, Organization Factors

and Firm Performance. 52, 1–5

[24] Gomes, G. and Wojahn, R.M.

(2017) ‘Organizational Learning Capability,

Innovation and Performance: Study in

Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises

(SMES)’. Revista de Administração 52,

163–175

[25] Haho, P. (2014) Learning Enablers,

Learning Outcomes, Learning Paths, and

Their Relationships in Organizational

Learning and Change.

[26] Hazlett, S.A., McAdam, R., and

Beggs, V. (2008) ‘An Exploratory Study of

Knowledge Flows: A Case Study of Public

Sector Procurement’. Total Quality

Management and Business Excellence 19,

57–66

[27] Holweg, M., Davies, J., De Meyer,

A., Lawson, B., and Schmenner, R.W.

(2018) ‘Improving Processes’. in Process

Theory: The Principles of Operations

Management. 167–192

[28] Hult, G.T.M. and Ferrell, O.C.

(1997) ‘Global Organizational Learning

Capacity in Purchasing: Construct and

Measurement’. Journal of Business

Research 40 (2), 97–111

[29] Isaacs, W.N. (1993) ‘Taking Flight:

Dialogue, Collective Thinking, and

Organizational Learning’. Organizational

Dynamics 22 (2), 24–39

[30] Jerez-Gómez, P., Céspedes-Lorente,

J., and Valle-Cabrera, R. (2005)

‘Organizational Learning Capability: A

Proposal of Measurement’. Journal of

Business Research 58 (6), 715–725

[31] Jerez Gómez, P., Céspedes Lorente,

J.J., and Valle Cabrera, R. (2004) ‘Training

Practices and Organisational Learning

Capability’. Journal of European Industrial

Training 28, 234–256

[32] Jiménez-Jiménez, D. and Sanz-

Valle, R. (2011) ‘Innovation, Organizational

Learning, and Performance’. Journal of

Business Research [online] 64 (4), 408–417.

available from

<http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.09

.010>

[33] Khalib, L.H., Kassim, N.A., and

Ghazali, F.I. (2015) ‘Organizational

Learning Capabilities ( OLC ) toward Job

Satisfaction : A Conceptual Framework’.

Academic Research International 6, 169–

180

[34] Khin, S. and Ho, T.C.F. (2019)

‘Digital Technology, Digital Capability and

Organizational Performance: A Mediating

Role of Digital Innovation’. International

Journal of Innovation Science 11 (2), 177–

195

[35] Knudsen, T. and Levinthal, D.A.

(2007) ‘Two Faces of Search: Alternative

Generation and Alternative Evaluation’.

Organization Science [online] 18 (1), 39–

54. available from

<http://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1

287/orsc.1060.0216>

[36] Laurell, C., Sandström, C.,

Eriksson, K., and Nykvist, R. (2020)

‘Digitalization and the Future of

Management Learning: New Technology as

an Enabler of Historical, Practice-Oriented,

and Critical Perspectives in Management

Research and Learning’. Management

Learning 51 (1), 89–108

[37] Lawrence, T.B., Mauws, M.K.,

Dyck, B., and Kleysen, R.F. (2005) ‘The

Politics of Organizational Learning:

Integrating Power into the 4I Framework’.

Academy of Management Review 30 (1),

180–191

[38] Leonard‐Barton, D. (1992) ‘Core

Capabilities and Core Rigidities: A Paradox

in Managing New Product Development’.

Strategic Management Journal 13 (S1),

111–125

[39] Levinthal, D.A. and March, J.G.

(1993) ‘The Myopia of Learning’. Strategic

Management Journal 14 (2 S), 95–112

[40] Majchrzak, A., Cooper, L.P., and

Neece, O.E. (2004) ‘Knowledge Reuse for

Innovation’. Management Science 50 (2),

174–188

[41] March, J.G. and Olsen, J.P. (1975)

‘The Uncertainty of the Past: Organizational

Learning Under Ambiguity’. European

Journal of Political Research 3 (2), 147–171

[42] Mbengue, A. and Sané, S. (2013)

‘Organizational Learning Capability:

Theoretical Analysis and Empirical Study in

the Context of Official Development Aid

Project Teams’. Canadian Journal of

Administrative Sciences 30, 26–39

[43] McGrath, J.E. and Argote, L.

(2001) ‘Group Processes in Organizational

Contexts’. Blackwell Handbook of Social

Psychology: Group Processes 603–627

[44] Moghadam, A., Bakhtiari, M.,

Raadabadi, M., and Bahadori, M. (2013)

‘Organizational Learning and

Empowerment of Nursing Status Tehran

University of Medical Sciences’. Education

Strategies in Medical Sciences 6 (2), 113–

118

[45] Muninger, M.I., Hammedi, W., and

Mahr, D. (2019) ‘The Value of Social

Media for Innovation: A Capability

Perspective’. Journal of Business Research

[online] 95 (October 2018), 116–127.

available from

<https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.0

12>

[46] Nonaka, I., Toyama, R., and Konno,

N. (2000) ‘SECI, Ba and Leadership: A

Unified Model of Dynamic Knowledge

Creation’. Long Range Planning 33, 5–34

[47] Noruzy, A., Dalfard, V.M.,

Azhdari, B., Nazari-Shirkouhi, S., and