Knowledge Identification Regarding Organ Donation Barriers

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/10

|10

|9886

|426

Report

AI Summary

This report examines the public's knowledge of organ donation, identifying key misconceptions and barriers that hinder donation rates. The study, involving undergraduate students, MBA students, and community members, assessed factual knowledge through a true/false questionnaire. Results revealed significant gaps in understanding, particularly regarding religious support, brain death, separation of physician teams, and the validity of donor cards. The report highlights the relationship between knowledge and attitudes towards organ donation, willingness to donate, and the likelihood of carrying a donor card. The findings suggest that improving public knowledge can positively influence attitudes and behaviors related to organ donation. Desklib provides access to similar solved assignments and resources for students.

Sot.Sci.Med. Vol.31,No.7.pp.791-800.1990 0277-953690 S3.00+0.00

Printed in Great Britain. All rights reserved Copyright S 1990 Pergamon Press plc

KNOWLEDGE REGARDING ORGAN DONATION:

IDENTIFYING AND OVERCOMING BARRIERS TO

ORGAN DONATION

RAYMOND L. HORTON and PATRICIAJ.HORTON

College of Business & Economics, Lehigh University, Drown Hall 35, Bethlehem, PA 18015, U.S.A.

Abstract-Four-hundred and fifty-five undergraduate students, 26 MBA students, and 465 people from

the surrounding community responded to 21 true/false questions regarding factual knowledge about organ

donation. The mean number of correct answers was 74.6%. The correct response rate, however, varied

widely over questions. Four questions with very large error rates suggest possible ‘barriers to donation’.

Specifically, these questions concerned religious support for organ donation, the concept of brain death.

the normally rigid separation of physician teams who are primarily responsible for the welfare of the donor

and donee, and a mistaken belief that to be valid an organ donor card must be filed with the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. Knowledge of organ donation facts was found to be related

to whether subjects carried or requested an organ donor card, their attitude towards organ donation and

their willingness to donate their own organs or the organs of a deceased loved one. These findings suggest

strategies for raising public support for organ donation.

Key words-organ donation, knowledge, education

INTRODUCI-ION

“Despite major advances in organ transplantation

technology, approximately one third of patients

accepted for transplantation die while awaiting a

matched donor” [I, p. 547, emphasis added]. These

deaths occur despite estimates that the pool of

potential donors is more than adequate to meet the

current demand for transplantable organs [2]. Unfor-

tunately, only a small fraction, perhaps as low as

15%, of these organs actually become available [l].

Understanding and overcoming the potential

‘barriers to donation’ that are so clearly apparent in

the discrepancy between demand and supply for

organs for transplantation is now recognized as a top

priority for organ donation research [3].

The focus of our research is on the decision to sign

and carry an organ donor card. A major assumption

underlying this research is that the decision process

involved in such decisions is constructed upon a

strong cognitive base. This assumption has a long and

productive history in psychology [cf. 41. While atti-

tudes, emotions, and behaviors that do not rest upon

a strong cognitive base are now generally acknowl-

edged to exist [e.g. $61, decisions that are important

to the person and that are made without great time

and external pressures are generally believed to fol-

low a model that proceeds from cognition to affect to

behavior and is generally referred to as a learning

hierarchy model of decision making [e.g. 5, 71. Atti-

tudes and decisions involving donor cards, as

opposed to actual donation decisions, are believed to

follow such a learning hierarchy model of decision

making.

The actual donation decision will be made by

family members under extremely difficult circum-

stances. This raises the question of the relationship

between signing a donor card and the family’s

decision to donate. Formal studies and impression-

istic evidence suggest important links between these

two very different types of decisions. Prottas [8] and

Manninen and Evans [9] show that knowledge that

the deceased carried a donor card is an important

factor in families’ decisions to donate. Recently,

Prottas and Batten [lo] reported in a large scale

survey “that medical/health professionals often hesi-

tate to cooperate because they fear contacting

families of donors” (p. 643). Callender [I I], a trans-

plant surgeon, reports that such requests are often

met with negative emotions of hostility, frustration,

anger, and despair. Callender also states that the

most important role for organ donor cards is in

stimulating family discussion. We believe that to

the extent physicians and other medical personnel

encounter positive reactions to requests for donation

they will be more willing to make such requests in the

future. We also believe that the likelihood of such

positive encounters will increase as more people sign

and carry donor cards.

Although many studies have shown high levels

of public awareness of organ donation [e.g. 91, there

has been little investigation of public knowledge of

specific facts regarding organ donation and what

effect such knowledge may have on the decision to

sign and carry an organ donor card. These same

studies indicate that only 14-19% of people polled

have actually signed donor cards. Clearly, awareness

alone has not been sufficient to turn general support

for the concept of organ transplantation into per-

sonal commitment to donate by signing donor cards.

The data reported here come from (1) a pilot for

a larger study of the relationships among knowledge,

values, attitudes, and behavior regarding organ

donation and the act of becoming a potential organ

donor, (2) a subsequent experiment which included

additional explanatory variables and an opportunity

Printed in Great Britain. All rights reserved Copyright S 1990 Pergamon Press plc

KNOWLEDGE REGARDING ORGAN DONATION:

IDENTIFYING AND OVERCOMING BARRIERS TO

ORGAN DONATION

RAYMOND L. HORTON and PATRICIAJ.HORTON

College of Business & Economics, Lehigh University, Drown Hall 35, Bethlehem, PA 18015, U.S.A.

Abstract-Four-hundred and fifty-five undergraduate students, 26 MBA students, and 465 people from

the surrounding community responded to 21 true/false questions regarding factual knowledge about organ

donation. The mean number of correct answers was 74.6%. The correct response rate, however, varied

widely over questions. Four questions with very large error rates suggest possible ‘barriers to donation’.

Specifically, these questions concerned religious support for organ donation, the concept of brain death.

the normally rigid separation of physician teams who are primarily responsible for the welfare of the donor

and donee, and a mistaken belief that to be valid an organ donor card must be filed with the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. Knowledge of organ donation facts was found to be related

to whether subjects carried or requested an organ donor card, their attitude towards organ donation and

their willingness to donate their own organs or the organs of a deceased loved one. These findings suggest

strategies for raising public support for organ donation.

Key words-organ donation, knowledge, education

INTRODUCI-ION

“Despite major advances in organ transplantation

technology, approximately one third of patients

accepted for transplantation die while awaiting a

matched donor” [I, p. 547, emphasis added]. These

deaths occur despite estimates that the pool of

potential donors is more than adequate to meet the

current demand for transplantable organs [2]. Unfor-

tunately, only a small fraction, perhaps as low as

15%, of these organs actually become available [l].

Understanding and overcoming the potential

‘barriers to donation’ that are so clearly apparent in

the discrepancy between demand and supply for

organs for transplantation is now recognized as a top

priority for organ donation research [3].

The focus of our research is on the decision to sign

and carry an organ donor card. A major assumption

underlying this research is that the decision process

involved in such decisions is constructed upon a

strong cognitive base. This assumption has a long and

productive history in psychology [cf. 41. While atti-

tudes, emotions, and behaviors that do not rest upon

a strong cognitive base are now generally acknowl-

edged to exist [e.g. $61, decisions that are important

to the person and that are made without great time

and external pressures are generally believed to fol-

low a model that proceeds from cognition to affect to

behavior and is generally referred to as a learning

hierarchy model of decision making [e.g. 5, 71. Atti-

tudes and decisions involving donor cards, as

opposed to actual donation decisions, are believed to

follow such a learning hierarchy model of decision

making.

The actual donation decision will be made by

family members under extremely difficult circum-

stances. This raises the question of the relationship

between signing a donor card and the family’s

decision to donate. Formal studies and impression-

istic evidence suggest important links between these

two very different types of decisions. Prottas [8] and

Manninen and Evans [9] show that knowledge that

the deceased carried a donor card is an important

factor in families’ decisions to donate. Recently,

Prottas and Batten [lo] reported in a large scale

survey “that medical/health professionals often hesi-

tate to cooperate because they fear contacting

families of donors” (p. 643). Callender [I I], a trans-

plant surgeon, reports that such requests are often

met with negative emotions of hostility, frustration,

anger, and despair. Callender also states that the

most important role for organ donor cards is in

stimulating family discussion. We believe that to

the extent physicians and other medical personnel

encounter positive reactions to requests for donation

they will be more willing to make such requests in the

future. We also believe that the likelihood of such

positive encounters will increase as more people sign

and carry donor cards.

Although many studies have shown high levels

of public awareness of organ donation [e.g. 91, there

has been little investigation of public knowledge of

specific facts regarding organ donation and what

effect such knowledge may have on the decision to

sign and carry an organ donor card. These same

studies indicate that only 14-19% of people polled

have actually signed donor cards. Clearly, awareness

alone has not been sufficient to turn general support

for the concept of organ transplantation into per-

sonal commitment to donate by signing donor cards.

The data reported here come from (1) a pilot for

a larger study of the relationships among knowledge,

values, attitudes, and behavior regarding organ

donation and the act of becoming a potential organ

donor, (2) a subsequent experiment which included

additional explanatory variables and an opportunity

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

792 RAYMOND L. HORTONand PATRICIAJ. HORTON

for subjects to request an organ donor card, and (3) a

followup study of the community surrounding the

university. The focus of the present report is on the

knowledge portion of the study.

The results of the survey reveal some major gaps

and errors in knowledge about organ donation. Posi-

tive relationships between knowledge and various

attitudinal and behavioral measures suggest that in-

creasing knowledge regarding organ donation may

improve attitudes towards organ donation, increase

expressed willingness to become a potential organ

donor or to donate the organs of a deceased loved

one, and increase the likelihood of requesting an

organ donor card when given the chance to do so.

METHODOLOGY

Subjects in the first study were 26 MBA students

and 455 undergraduates at an eastern private univer-

sity. These subjects were drawn from the subject pool

maintained by the psychology department and sev-

eral courses in the colleges of arts and sciences and

business and all subjects were participating as a

course requirement. While subjects represented a

cross section of the university, the student sample

must be regarded as a convenience sample. Subjects

in the second study were 465 adults drawn from the

local community. The subjects were recruited as a

Kth sample from the local telephone directory. There

were three phases to the data collection process and

five distinct subject groups:

A preexperimental group of (1) 115 undergraduates and (2)

26 MBA students who completed four questionnaires in the

following sequence: (a) Rokeach’s[ 121Terminal and Instru-

mental value scales, (b) Goodmonson and Glaudin’s 113)

Attitude Toward Organ Donation scale, (c) the organ

donation knowledge instrument developed and reported

here, and (d) an instrument that collected data on subjects’

age, sex, previous experience with organ donation, whether

subjects carried a donor card, and willingness to donate the

organs of a loved one and willingness to donate theirown

organs.

(3) A true experimental group of 185 undergraduates who

answered the above questionnaires plus a Belief in a Just

World Scale ll41 and an Attitude Towards Death Scale I151

which were piaced immediately following the Rokeach v&.rd

scales. These subjects were not asked questions about their

experiences with organ donation or their willingness to

donate. They were asked their class standing and college

affiliation. Approximately one month after completing these

questionnaires, subjects received a letter from Mr Howard

Nathan, Executive Director of the Delaware Valley Trans-

plant Program, explaining the need for donated- organs.

Enclosed with Mr Nathan’s letter was a Dow nublication

called ‘Make a Miracle’ that explains organ donation in a

simple question and answer format and an addressed,

stamped postcard the subject could use to request an organ

donor card. The Delaware Valley Transplant Program

prepared a coded list of subjects who requested a donor

card.

As part of the experiment there was also (4) a control

group of 155 undergraduates. The control group completed

the questionnaires approximately one month a/rer receiving

*The authors greatly appreciate the assistance of Howard

Nathan, Executive Director of the Delaware Valley

Transplant Program, in reviewing the knowledge ques-

tionnaire.

the letter and accompanying material from Mr Nathan

described above and ufier the cutoff date for recording

requested organ donor cards. These subjects also completed

all demographic and donor questions described for groups

one and two.

The second study used telephone contacts, which were

made by 78 undergraduate students in the first author’s

marketing research class, to request adult members of the

local community to complete a mail survey on organ

donation. Of 968 who agreed to participate, useable re-

sponses were received from 465 persons. Five questionnaires

were returned uncompleted; two with notes explaining that

after seeing the questionnaire they had decided not to

participate. Although the overall content of the question-

naires was similar, a number of changes were made to make

the questionnaire more appropriate for a mail survey. The

knowledge questions, however, were unchanged. The last

question on the survey was whether the respondent would

like to be sent an organ donor card.

Data for the student sample was collected in

groups of approx. IO-20 persons. In a brief intro-

duction student subjects were told only that the study

concerned the relationships among knowledge,

values, attitudes, and behavior. The format of the

questionnaires to be answered was explained and

subjects were asked if they had any questions, few

did, and then told to begin. The entire process took

approx. 20-25 min. While the Organ Donation Atti-

tude questionnaire alerted most subjects to the object

of study, it provided subjects with no factual infor-

mation. Subjects in the second study were told in the

initial telephone request that the survey concerned

organ donation. Approximately half of the persons

contacted by telephone agreed to participate. These

persons were mailed the self-administered question-

naire along with a postage paid business reply

envelop. Subjects were invited to telephone the first

author if they had any questions or concerns about

the survey. None did.

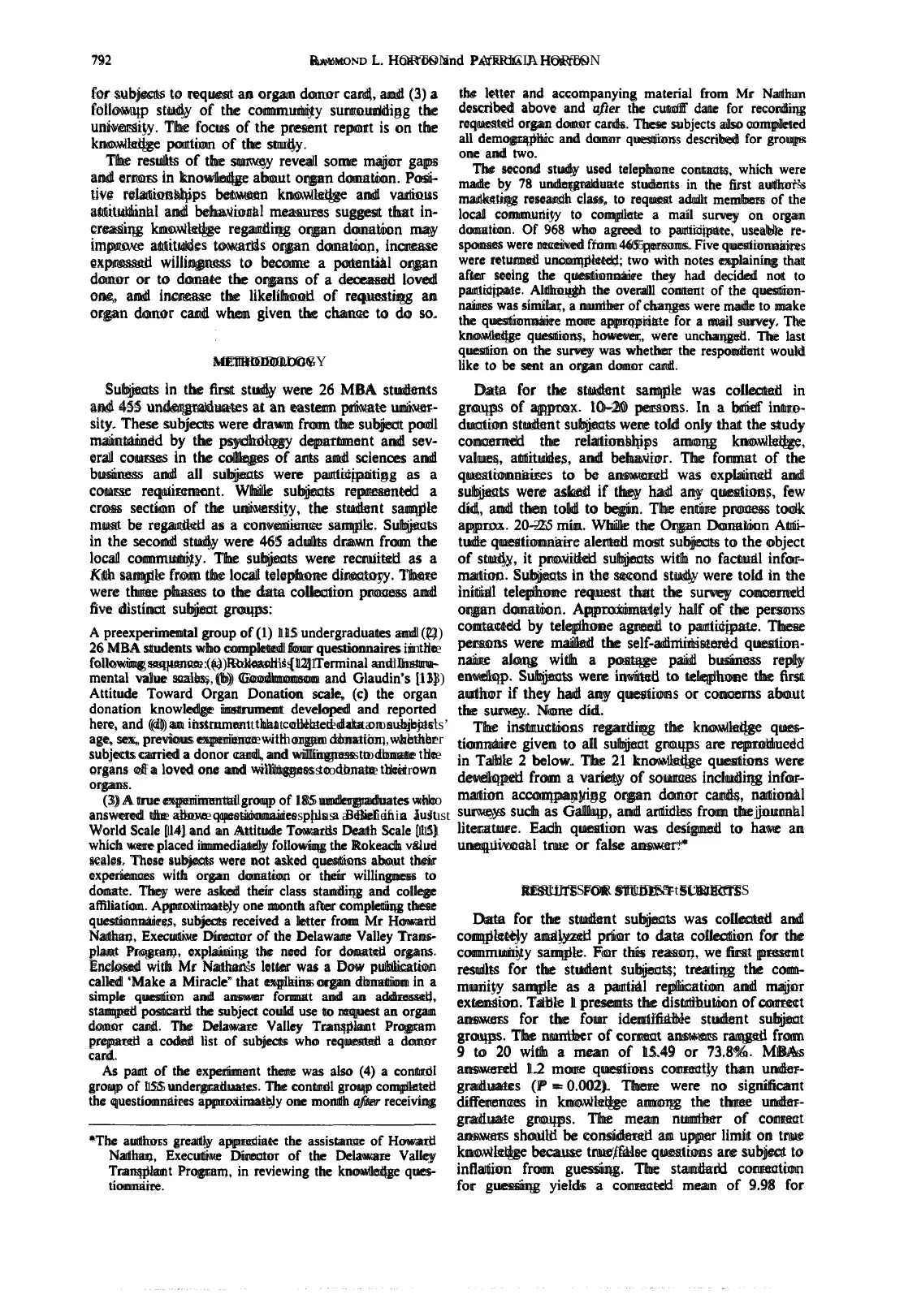

The instructions regarding the knowledge ques-

tionnaire given to all subject groups are reproduced

in Table 2 below. The 21 knowledge questions were

developed from a variety of sources including infor-

mation accompanying organ donor cards, national

surveys such as Gallup, and articles from the journal

literature. Each question was designed to have an

unequivocal true or false answer.*

RESULTSFOR STUDE5-t’SURJECTS

Data for the student subjects was collected and

completely analyzed prior to data collection for the

community sample. For this reason, we first present

results for the student subjects; treating the com-

munity sample as a partial replication and major

extension. Table 1 presents the distribution of correct

answers for the four identifiable student subject

groups. The number of correct answers ranged from

9 to 20 with a mean of 15.49 or 73.8%. MBAs

answered 1.2 more questions correctly than under-

graduates (P = 0.002). There were no significant

differences in knowledge among the three under-

graduate groups. The mean number of correct

answers should be considered an upper limit on true

knowledge because true/false questions are subject to

inflation from guessing. The standard correction

for guessing yields a corrected mean of 9.98 for

for subjects to request an organ donor card, and (3) a

followup study of the community surrounding the

university. The focus of the present report is on the

knowledge portion of the study.

The results of the survey reveal some major gaps

and errors in knowledge about organ donation. Posi-

tive relationships between knowledge and various

attitudinal and behavioral measures suggest that in-

creasing knowledge regarding organ donation may

improve attitudes towards organ donation, increase

expressed willingness to become a potential organ

donor or to donate the organs of a deceased loved

one, and increase the likelihood of requesting an

organ donor card when given the chance to do so.

METHODOLOGY

Subjects in the first study were 26 MBA students

and 455 undergraduates at an eastern private univer-

sity. These subjects were drawn from the subject pool

maintained by the psychology department and sev-

eral courses in the colleges of arts and sciences and

business and all subjects were participating as a

course requirement. While subjects represented a

cross section of the university, the student sample

must be regarded as a convenience sample. Subjects

in the second study were 465 adults drawn from the

local community. The subjects were recruited as a

Kth sample from the local telephone directory. There

were three phases to the data collection process and

five distinct subject groups:

A preexperimental group of (1) 115 undergraduates and (2)

26 MBA students who completed four questionnaires in the

following sequence: (a) Rokeach’s[ 121Terminal and Instru-

mental value scales, (b) Goodmonson and Glaudin’s 113)

Attitude Toward Organ Donation scale, (c) the organ

donation knowledge instrument developed and reported

here, and (d) an instrument that collected data on subjects’

age, sex, previous experience with organ donation, whether

subjects carried a donor card, and willingness to donate the

organs of a loved one and willingness to donate theirown

organs.

(3) A true experimental group of 185 undergraduates who

answered the above questionnaires plus a Belief in a Just

World Scale ll41 and an Attitude Towards Death Scale I151

which were piaced immediately following the Rokeach v&.rd

scales. These subjects were not asked questions about their

experiences with organ donation or their willingness to

donate. They were asked their class standing and college

affiliation. Approximately one month after completing these

questionnaires, subjects received a letter from Mr Howard

Nathan, Executive Director of the Delaware Valley Trans-

plant Program, explaining the need for donated- organs.

Enclosed with Mr Nathan’s letter was a Dow nublication

called ‘Make a Miracle’ that explains organ donation in a

simple question and answer format and an addressed,

stamped postcard the subject could use to request an organ

donor card. The Delaware Valley Transplant Program

prepared a coded list of subjects who requested a donor

card.

As part of the experiment there was also (4) a control

group of 155 undergraduates. The control group completed

the questionnaires approximately one month a/rer receiving

*The authors greatly appreciate the assistance of Howard

Nathan, Executive Director of the Delaware Valley

Transplant Program, in reviewing the knowledge ques-

tionnaire.

the letter and accompanying material from Mr Nathan

described above and ufier the cutoff date for recording

requested organ donor cards. These subjects also completed

all demographic and donor questions described for groups

one and two.

The second study used telephone contacts, which were

made by 78 undergraduate students in the first author’s

marketing research class, to request adult members of the

local community to complete a mail survey on organ

donation. Of 968 who agreed to participate, useable re-

sponses were received from 465 persons. Five questionnaires

were returned uncompleted; two with notes explaining that

after seeing the questionnaire they had decided not to

participate. Although the overall content of the question-

naires was similar, a number of changes were made to make

the questionnaire more appropriate for a mail survey. The

knowledge questions, however, were unchanged. The last

question on the survey was whether the respondent would

like to be sent an organ donor card.

Data for the student sample was collected in

groups of approx. IO-20 persons. In a brief intro-

duction student subjects were told only that the study

concerned the relationships among knowledge,

values, attitudes, and behavior. The format of the

questionnaires to be answered was explained and

subjects were asked if they had any questions, few

did, and then told to begin. The entire process took

approx. 20-25 min. While the Organ Donation Atti-

tude questionnaire alerted most subjects to the object

of study, it provided subjects with no factual infor-

mation. Subjects in the second study were told in the

initial telephone request that the survey concerned

organ donation. Approximately half of the persons

contacted by telephone agreed to participate. These

persons were mailed the self-administered question-

naire along with a postage paid business reply

envelop. Subjects were invited to telephone the first

author if they had any questions or concerns about

the survey. None did.

The instructions regarding the knowledge ques-

tionnaire given to all subject groups are reproduced

in Table 2 below. The 21 knowledge questions were

developed from a variety of sources including infor-

mation accompanying organ donor cards, national

surveys such as Gallup, and articles from the journal

literature. Each question was designed to have an

unequivocal true or false answer.*

RESULTSFOR STUDE5-t’SURJECTS

Data for the student subjects was collected and

completely analyzed prior to data collection for the

community sample. For this reason, we first present

results for the student subjects; treating the com-

munity sample as a partial replication and major

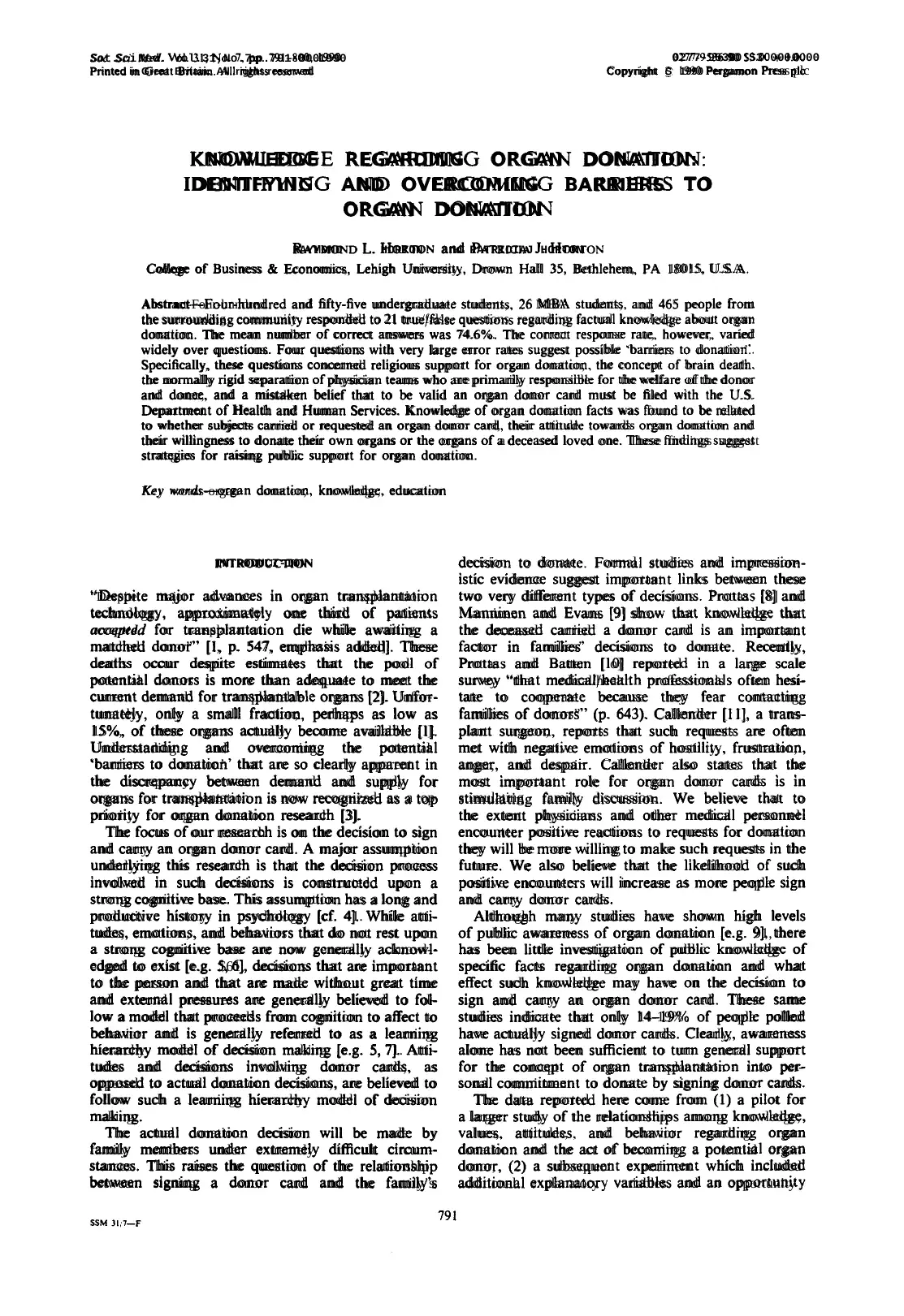

extension. Table 1 presents the distribution of correct

answers for the four identifiable student subject

groups. The number of correct answers ranged from

9 to 20 with a mean of 15.49 or 73.8%. MBAs

answered 1.2 more questions correctly than under-

graduates (P = 0.002). There were no significant

differences in knowledge among the three under-

graduate groups. The mean number of correct

answers should be considered an upper limit on true

knowledge because true/false questions are subject to

inflation from guessing. The standard correction

for guessing yields a corrected mean of 9.98 for

Knowledge regarding organ donation

Table I. Distribution of student subjects by total number of correct responses

Subject group

793

Number of Pmxperiment Experiment Overall

correct responses Undergraduates MBA Experimental Control Percent

9

IO

II

12

13

14

I5

I6

I7

I8

I9

20

Mean number

0

0

3

4

9

f9

::

IO

;

21

32

39

27

14

1

^

4

1

8

I2

I9

24

35

20

20

0.3

0.9

2.3

4.5

8.9

13.2

17.0

21.3

15.7

10.4

4.0

I.1

correct= IS.38 16.62 IS.32 15.56 15.49

N- 112 26 179 I53 470

Eleven subjects were excluded because of missing data on one or more knowledge questions.

undergraduates, 12.24 for MBAs or 47.5 and 58.3%,

respectively.* These corrected means. however, are

ambiguous because subjects’ responses for unknown

answers are undoubtedly influenced by such things as

cultural biases in addition to simple guessing.

The higher level of knowledge of MBAs, who were

all part-time students, is most likely accounted for by

the many normal correlates of age and the greater

exposure of MBAs to the mass media. For all subject

groups, however, there are clearly deficiencies in

overall knowledge regarding organ donation. Far

more interesting, however, is the fact that the level of

correct response varies widely by question.

The 21 knowledge questions, correct answer for

each question, and percent of subjects answering

correctly are displayed in Table 2. The large sample

size means that these sample percentages are rather

close estimates of their corresponding population

values.7 In interpreting the data the normal upward

bias of true/false questions should be kept in mind.

Eight of the 21 questions were answered correctly

by 88% or more of the subjects, with six additional

questions answered correctly by 76% or more of the

subjects. In general these correct responses indicate

that subjects were aware of the inadequate supply of

organs, of the increasing cost effectiveness of certain

transplant operations, and of a number of aspects

of normal organ donation procedures and their

*The standard correction for guessing for true/false ques-

tions assumes that known answers are reported accu-

rately whereas unknown answers are reported correct at

the rate of 50%. This leads to a correction eauation of.

correct minus incorrect or, in the aggregate, percent

correct minus percent incorrrect.

Standard errors of the proportion of answers correct

ranged from 0.0077 to 0.0228 and averaged 0.0169. This

gives an average error of approx. 3.3% and a maximum

error of approx. 4.5% at the 95% level of confidence.

iAlthough racial data was not collected, it should be noted

that there were almost no blacks in the student sample.

This racial imbalance is consistent with the racial com-

position of the student population. For the community

sample racial identification was requested. Approxi-

mately 99% of the respondents identified themselves as

white. The absence of blacks is consistent with the racial

composition of the community.

consequences. Specifically, subjects were generally

correct in answering questions regarding who is

eligible to donate, the necessity of permission from

the donor or next of kin, and the fact that donation

does not normally interfere with funeral arrange-

ments. While it is likely that such factors as random

guessing and answering in accord with generally

accepted values in our society bias the percent correct

(e.g. the right to privacy would appear inconsistent

with ‘presumed consent’ laws), the relatively high

correct response to these questions is consistent

with national surveys such as Gallup [ 161 that find a

high degree of general public awareness of organ

transplantation.

Of the remaining seven questions, three were cor-

rectly answered by 58-69% of the subjects. These

questions concerned the impossibility of guaranteeing

that a donor’s organs will actually be transplanted,

the legal proscription of financial gain of any kind

to the donor’s family, and the fact that different

racial and socioeconomic groups are not equally

represented among donors.$ Assuming some upward

bias, the responses to these questions identify

potential gaps in public knowledge regarding organ

donation.

The most interesting data concerns the four ques-

tions that were answered correctly by fewer than half

of the respondents and potentially constitute serious

barriers to becoming a potential organ donor. Stated

in terms of implied beliefs, 61.5% indicated that at

least some major Western religions do not support

organ donation. 79.3% of the respondents indicated

that the cessation of all pulmonary activity was

necessary before a donor’s organs can be removed.

Although 77.2% of the subjects responded correctly

to the brain death question, one possible implication

is that current perceptions of brain death include

the cessation of all pulmonary activity. 55.8% of the

respondents indicated that they thought it not uneth-

ical for the same physician to have primary responsi-

bility for donor and donee. While the present data

cannot determine what subjects actually believe re-

garding current practices, a lack of awareness of the

efforts made to protect the interests of the donor [ 171

is suggested by the responses to this question. Finally,

73.5% of the respondents indicated that a donor card

Table I. Distribution of student subjects by total number of correct responses

Subject group

793

Number of Pmxperiment Experiment Overall

correct responses Undergraduates MBA Experimental Control Percent

9

IO

II

12

13

14

I5

I6

I7

I8

I9

20

Mean number

0

0

3

4

9

f9

::

IO

;

21

32

39

27

14

1

^

4

1

8

I2

I9

24

35

20

20

0.3

0.9

2.3

4.5

8.9

13.2

17.0

21.3

15.7

10.4

4.0

I.1

correct= IS.38 16.62 IS.32 15.56 15.49

N- 112 26 179 I53 470

Eleven subjects were excluded because of missing data on one or more knowledge questions.

undergraduates, 12.24 for MBAs or 47.5 and 58.3%,

respectively.* These corrected means. however, are

ambiguous because subjects’ responses for unknown

answers are undoubtedly influenced by such things as

cultural biases in addition to simple guessing.

The higher level of knowledge of MBAs, who were

all part-time students, is most likely accounted for by

the many normal correlates of age and the greater

exposure of MBAs to the mass media. For all subject

groups, however, there are clearly deficiencies in

overall knowledge regarding organ donation. Far

more interesting, however, is the fact that the level of

correct response varies widely by question.

The 21 knowledge questions, correct answer for

each question, and percent of subjects answering

correctly are displayed in Table 2. The large sample

size means that these sample percentages are rather

close estimates of their corresponding population

values.7 In interpreting the data the normal upward

bias of true/false questions should be kept in mind.

Eight of the 21 questions were answered correctly

by 88% or more of the subjects, with six additional

questions answered correctly by 76% or more of the

subjects. In general these correct responses indicate

that subjects were aware of the inadequate supply of

organs, of the increasing cost effectiveness of certain

transplant operations, and of a number of aspects

of normal organ donation procedures and their

*The standard correction for guessing for true/false ques-

tions assumes that known answers are reported accu-

rately whereas unknown answers are reported correct at

the rate of 50%. This leads to a correction eauation of.

correct minus incorrect or, in the aggregate, percent

correct minus percent incorrrect.

Standard errors of the proportion of answers correct

ranged from 0.0077 to 0.0228 and averaged 0.0169. This

gives an average error of approx. 3.3% and a maximum

error of approx. 4.5% at the 95% level of confidence.

iAlthough racial data was not collected, it should be noted

that there were almost no blacks in the student sample.

This racial imbalance is consistent with the racial com-

position of the student population. For the community

sample racial identification was requested. Approxi-

mately 99% of the respondents identified themselves as

white. The absence of blacks is consistent with the racial

composition of the community.

consequences. Specifically, subjects were generally

correct in answering questions regarding who is

eligible to donate, the necessity of permission from

the donor or next of kin, and the fact that donation

does not normally interfere with funeral arrange-

ments. While it is likely that such factors as random

guessing and answering in accord with generally

accepted values in our society bias the percent correct

(e.g. the right to privacy would appear inconsistent

with ‘presumed consent’ laws), the relatively high

correct response to these questions is consistent

with national surveys such as Gallup [ 161 that find a

high degree of general public awareness of organ

transplantation.

Of the remaining seven questions, three were cor-

rectly answered by 58-69% of the subjects. These

questions concerned the impossibility of guaranteeing

that a donor’s organs will actually be transplanted,

the legal proscription of financial gain of any kind

to the donor’s family, and the fact that different

racial and socioeconomic groups are not equally

represented among donors.$ Assuming some upward

bias, the responses to these questions identify

potential gaps in public knowledge regarding organ

donation.

The most interesting data concerns the four ques-

tions that were answered correctly by fewer than half

of the respondents and potentially constitute serious

barriers to becoming a potential organ donor. Stated

in terms of implied beliefs, 61.5% indicated that at

least some major Western religions do not support

organ donation. 79.3% of the respondents indicated

that the cessation of all pulmonary activity was

necessary before a donor’s organs can be removed.

Although 77.2% of the subjects responded correctly

to the brain death question, one possible implication

is that current perceptions of brain death include

the cessation of all pulmonary activity. 55.8% of the

respondents indicated that they thought it not uneth-

ical for the same physician to have primary responsi-

bility for donor and donee. While the present data

cannot determine what subjects actually believe re-

garding current practices, a lack of awareness of the

efforts made to protect the interests of the donor [ 171

is suggested by the responses to this question. Finally,

73.5% of the respondents indicated that a donor card

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

794 RAYMOND L. HORTON and PAIXICVI J. HORTON

Table 2. Organ donation knowledge survey-percent correct responses for student subjects

Instructions to subjects: Each of the followingtrue/false questions concerns some fact about organ donation or the act of becomingan organ

donor. All questions pertain to the donation of organs after one’s death and specifically exclude blood donation and donation of a single

kidney by a living donor. For each question there is a single correct answer. Please answer all questions by circling either T (for true) or

F (for false)

Percent

correct

correct

answer Ouestion

88.9 T

97. I F

38.5 T

20.7 F

88.5 F

92.3 T

44.2 T

89.5 F

58.7 F

80.7 T

92.0 T

95.8 F

94. I T

79.8 T

63.9 F

84.2 T

77.2 T

83.8 F

26.5 F

76.6 T

68.8 F

I. Under the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act, any mentally competent person, 18 years of age or older. can

become a potential organ donor simply by signing an organ donation card in the presence of two witnesses

who also sign the card.

2. Once signed, an organ donation card is irrevocable.

3. Almost all Western religious groups support the concept of organ donation.

4. Before a donor’s organs can be removed, a physician must certify that the potential donor’s heart has ceased

to function and that all pulmonary activity has ceased.

5. The procedures necessary to remove a donor’s organs often make it impossible to have an open casket funeral.

6. The donor’s family is not responsible for the hospital and surgery costs for removing, preserving, and

transporting the donor’s organs.

7. It is considered unethical for the same physician to have primary responsibility for the care of both the organ

donor and the organ donee.

8. Anyone over the age of 40 is not acceptable as an organ donor.

9. A benefit of donating one’s organs is that, if requested, it is often possible to get sufficient compensation to

offset the cost of burial.

IO. Under the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act, your wish to donate your own organs. properly documented by

an organ donor card, takes legal precedence over the wishes of your next of kin.

Il. For some types of organ transplants it is less expensive to do the transplant operation than to provide terminal

care for the patient.

12. A physician is legally empowered to donate, without permission of the decedent or the next of kin, the organs

of a patient under his or her care who has died.

13. For most organs, demand is significantly greater than supply.

14. Large sample surveys, such as Gallup. show that the majority of Americans in-principle support the concept

of organ transplantation.

IS. If death occurs in a hospital, the potential donor can be virtually certain that his or her organs will be

transplanted.

16. The process of organ donation generally does not result in any significant delay in normal funeral

arrangements.

17. Brain death occurs when there is irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain

stem.

18. A majority of states now have so-called ‘presumed consent’ laws that presume that a deceased person has

given consent to have his or her organsremoved for purposes of transplantation unless a written declaration

to the contrary exists.

19. For an organ donor card to be valid, a copy must be filed with the U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services.

20. The ‘ideal’ donor is a young adult who has died of a head injury.

21. Organ donors tend to come, relative to the size of the population, equally from all racial and socioeconomic

is valid only if it is on file with the U.S. Department

of Health and Human Services.

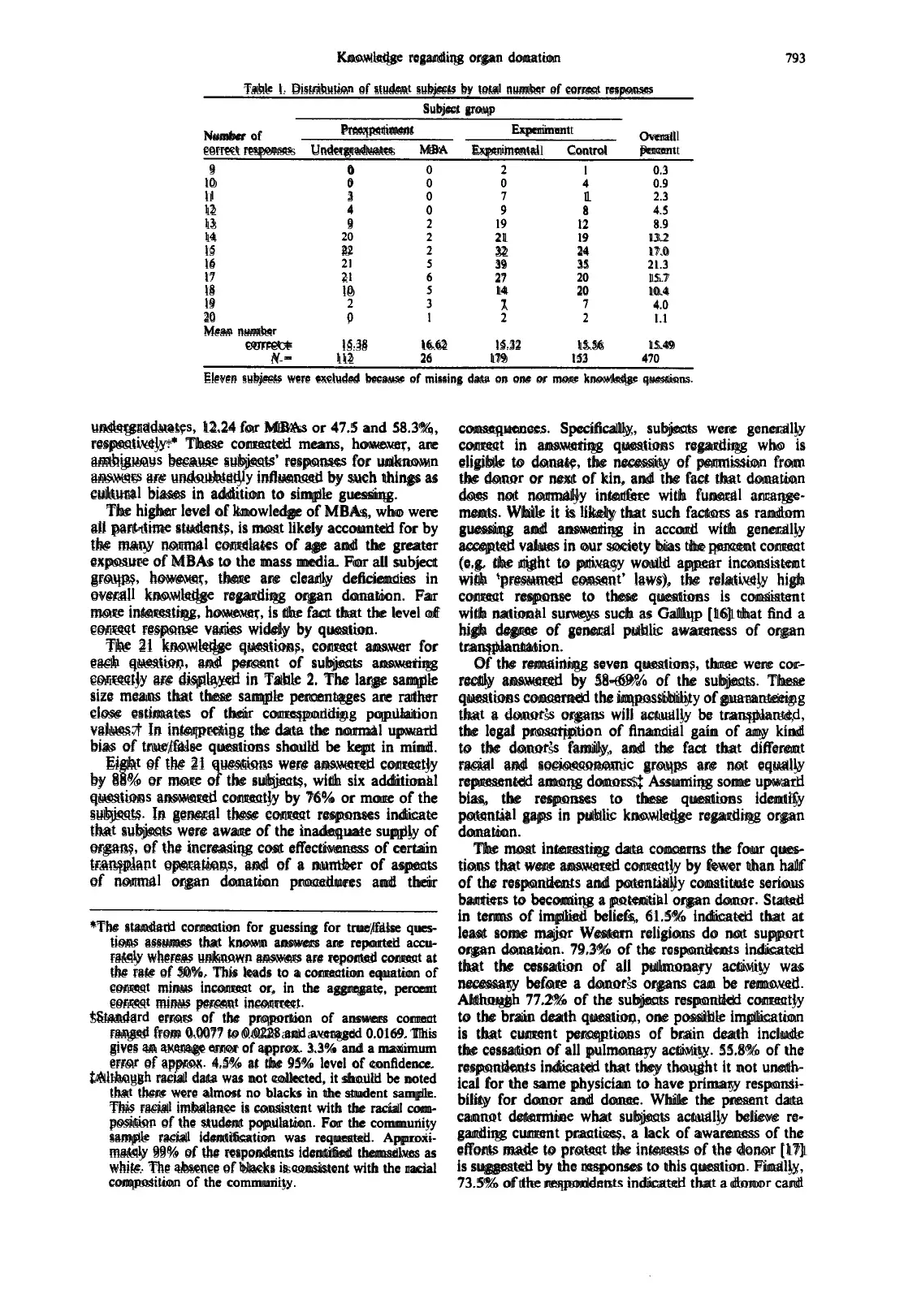

Three additional analyses were conducted to assess

the relationships among the knowledge questions and

the attitudinal, willingness to donate, and behavioral

measures. First, correlations were computed between

total knowledge and attitude towards organ

donation, whether the subject carried or had carried

an organ donor card, whether the subject requested

an organ donor card, and willingness to donate the

organs of a loved one or one’s own organs at the time

of death. Table 3 presents the data.

With one exception, which is nonsignificant, all

of the correlations in Table 3 are, as expected,

positive. All of the significant correlations are also

small. An interesting result is that the undergraduate

Table 3. Correlations between total knowledge and attitude towards organ donation (Attitude), carrying

organ donor card (Card), requesting organ donor card (Request), and willingness to donate the organs

of a loved one (Wol) and oneself (Wxlf) for student subjects

Variable

Subject group Attitude Card Request Wol Wself

Preexperiment

Undergraduates 0.046 0.223. N/A -0.091 O.OJ3

(107) (109) (109) (109)

MBA students 0.257 0.420’ NIA 0.131 0.197

(24) (26) (24) (24)

Experiment

Experimental subjects 0.223*** N/A 0.233. N/A N/A

(178) (129)

Control subjects 0.265”’ 0.314*** 0.315*** 0.161” 0.253..

(148) (152) (153) (153) 053)

All groups 0.193*** 0.294*** 0.259” 0.066 0.175***

(457) (287) (332) (286) (286)

l P -z 0.05, l *P < 0.01, l **P < 0.001. Sample size in parentheses below correlation. The correlations

between all questions and the card and request measures are polyxrial correlations [30]. All other

correlations are Pearson product-moment correlations.

Table 2. Organ donation knowledge survey-percent correct responses for student subjects

Instructions to subjects: Each of the followingtrue/false questions concerns some fact about organ donation or the act of becomingan organ

donor. All questions pertain to the donation of organs after one’s death and specifically exclude blood donation and donation of a single

kidney by a living donor. For each question there is a single correct answer. Please answer all questions by circling either T (for true) or

F (for false)

Percent

correct

correct

answer Ouestion

88.9 T

97. I F

38.5 T

20.7 F

88.5 F

92.3 T

44.2 T

89.5 F

58.7 F

80.7 T

92.0 T

95.8 F

94. I T

79.8 T

63.9 F

84.2 T

77.2 T

83.8 F

26.5 F

76.6 T

68.8 F

I. Under the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act, any mentally competent person, 18 years of age or older. can

become a potential organ donor simply by signing an organ donation card in the presence of two witnesses

who also sign the card.

2. Once signed, an organ donation card is irrevocable.

3. Almost all Western religious groups support the concept of organ donation.

4. Before a donor’s organs can be removed, a physician must certify that the potential donor’s heart has ceased

to function and that all pulmonary activity has ceased.

5. The procedures necessary to remove a donor’s organs often make it impossible to have an open casket funeral.

6. The donor’s family is not responsible for the hospital and surgery costs for removing, preserving, and

transporting the donor’s organs.

7. It is considered unethical for the same physician to have primary responsibility for the care of both the organ

donor and the organ donee.

8. Anyone over the age of 40 is not acceptable as an organ donor.

9. A benefit of donating one’s organs is that, if requested, it is often possible to get sufficient compensation to

offset the cost of burial.

IO. Under the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act, your wish to donate your own organs. properly documented by

an organ donor card, takes legal precedence over the wishes of your next of kin.

Il. For some types of organ transplants it is less expensive to do the transplant operation than to provide terminal

care for the patient.

12. A physician is legally empowered to donate, without permission of the decedent or the next of kin, the organs

of a patient under his or her care who has died.

13. For most organs, demand is significantly greater than supply.

14. Large sample surveys, such as Gallup. show that the majority of Americans in-principle support the concept

of organ transplantation.

IS. If death occurs in a hospital, the potential donor can be virtually certain that his or her organs will be

transplanted.

16. The process of organ donation generally does not result in any significant delay in normal funeral

arrangements.

17. Brain death occurs when there is irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain

stem.

18. A majority of states now have so-called ‘presumed consent’ laws that presume that a deceased person has

given consent to have his or her organsremoved for purposes of transplantation unless a written declaration

to the contrary exists.

19. For an organ donor card to be valid, a copy must be filed with the U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services.

20. The ‘ideal’ donor is a young adult who has died of a head injury.

21. Organ donors tend to come, relative to the size of the population, equally from all racial and socioeconomic

is valid only if it is on file with the U.S. Department

of Health and Human Services.

Three additional analyses were conducted to assess

the relationships among the knowledge questions and

the attitudinal, willingness to donate, and behavioral

measures. First, correlations were computed between

total knowledge and attitude towards organ

donation, whether the subject carried or had carried

an organ donor card, whether the subject requested

an organ donor card, and willingness to donate the

organs of a loved one or one’s own organs at the time

of death. Table 3 presents the data.

With one exception, which is nonsignificant, all

of the correlations in Table 3 are, as expected,

positive. All of the significant correlations are also

small. An interesting result is that the undergraduate

Table 3. Correlations between total knowledge and attitude towards organ donation (Attitude), carrying

organ donor card (Card), requesting organ donor card (Request), and willingness to donate the organs

of a loved one (Wol) and oneself (Wxlf) for student subjects

Variable

Subject group Attitude Card Request Wol Wself

Preexperiment

Undergraduates 0.046 0.223. N/A -0.091 O.OJ3

(107) (109) (109) (109)

MBA students 0.257 0.420’ NIA 0.131 0.197

(24) (26) (24) (24)

Experiment

Experimental subjects 0.223*** N/A 0.233. N/A N/A

(178) (129)

Control subjects 0.265”’ 0.314*** 0.315*** 0.161” 0.253..

(148) (152) (153) (153) 053)

All groups 0.193*** 0.294*** 0.259” 0.066 0.175***

(457) (287) (332) (286) (286)

l P -z 0.05, l *P < 0.01, l **P < 0.001. Sample size in parentheses below correlation. The correlations

between all questions and the card and request measures are polyxrial correlations [30]. All other

correlations are Pearson product-moment correlations.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Knowledge regarding organ donation

Table 4. Correlations bctwcen individual knowledge questions and attitude towards organ donation

(Attitude). carrying organ donor card (Card), rquesting organ donor card (Request), and willingness

to donate the organs of a loved one (Wol) and oneself (Wself)for student subjects

Variable

Knowledge question Attitude Card Request Wol Wself

No. I-Uniform Gift Act 0.144***

(MO)

No. 3-Religious support 0.159’.

(288)

No. 5-Open casket 0.124.’

(290)

No. g-Age greater than 40 0.106” 0.i29”

(41) (290)

No. 9-Benefit 0.100**

(460)

No. IbFuncral 0.152*** 0.134”

(61) (334)

No. 18-Presumed consent -0.120**

(290)

No. l9-File with HHS 0.202”’ 0.390*** 0.170’** 0.201*** 0.251***

(41) (288) (334) (289) (287)

l P < 0.05, l *P < 0.01, l **P < 0.001. Sample size in parentheses below correlation. Only correlations

significant at the 0.05 level are rcportcd. The correlationsbetween individual questions and card

and rcquat measures arc Kendall’s Tau B. For the prcseot data, these correlations arc identical

to Pearson product-moment correlations. The significance values, however, are slightly different

from the values that would bc calculated under the assumptions of Pearson product-moment

correlations. For details see Conover [29). All other correlations are Pearson product-moment

795

correlations.

preexperimental subjects have uniformly lower corre-

lations than the other three groups. This difference

with the MBA students may reflect the greater ex-

posure of MBAs to the mass media. The difference

with the experimental undergraduate subjects may be

due to the fact that data for the experimental groups

was collected approx. 12-18 months after the data

collection for preexperimental subjects. During this

time period information regarding organ donation

may have diffused more widely. Although only one of

the correlations for the MBA group is significant,

largely because of the very small sample size, the

magnitude of these correlations are generally close to

the correlations for the two experimental groups. All

of the correlations for the two experimental groups

are significant with most being highly significant.

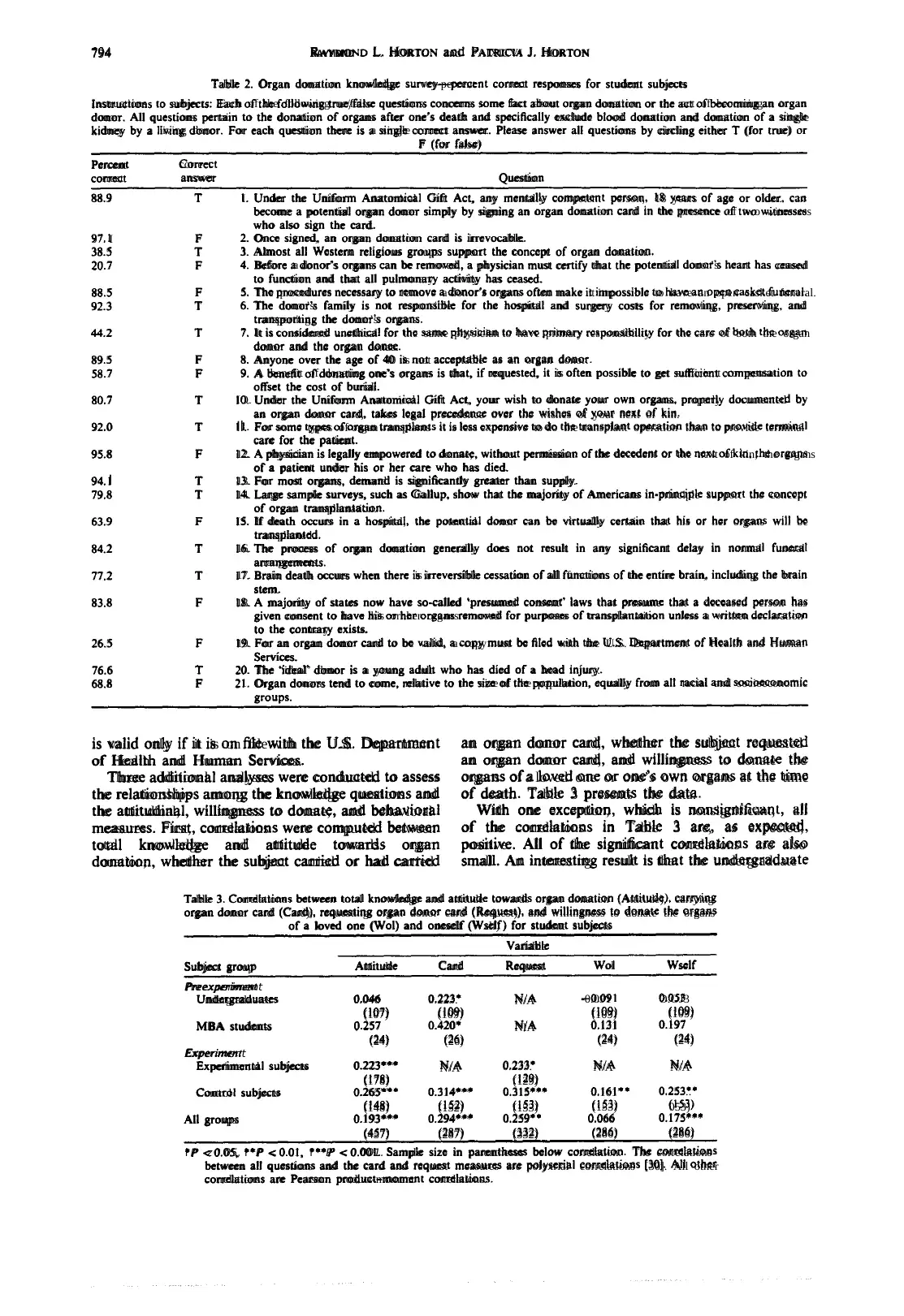

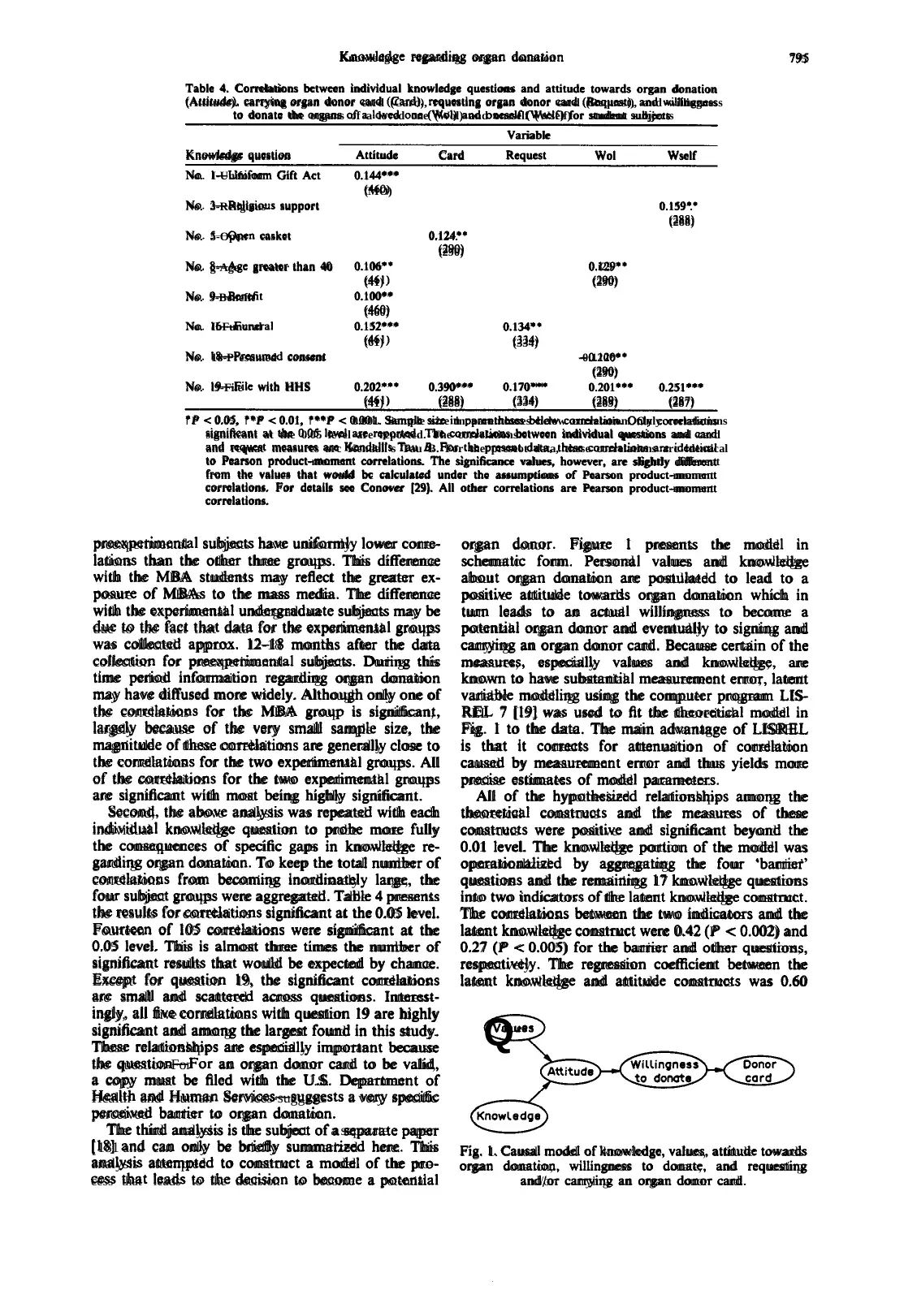

Second, the above analysis was repeated with each

individual knowledge question to probe more fully

the consequences of specific gaps in knowledge re-

garding organ donation. To keep the total number of

correlations from becoming inordinately large, the

four subject groups were aggregated. Table 4 presents

the results for correlations significant at the 0.05 level.

Fourteen of I05 correlations were significant at the

0.05 level. This is almost three times the number of

significant results that would be expected by chance.

Except for question 19, the significant correlations

are small and scattered across questions. Interest-

ingly, all five correlations with question I9 are highly

significant and among the largest found in this study.

These relationships are especially important because

the question-For an organ donor card to be valid,

a copy must be filed with the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services-suggests a very specific

perceived barrier to organ donation.

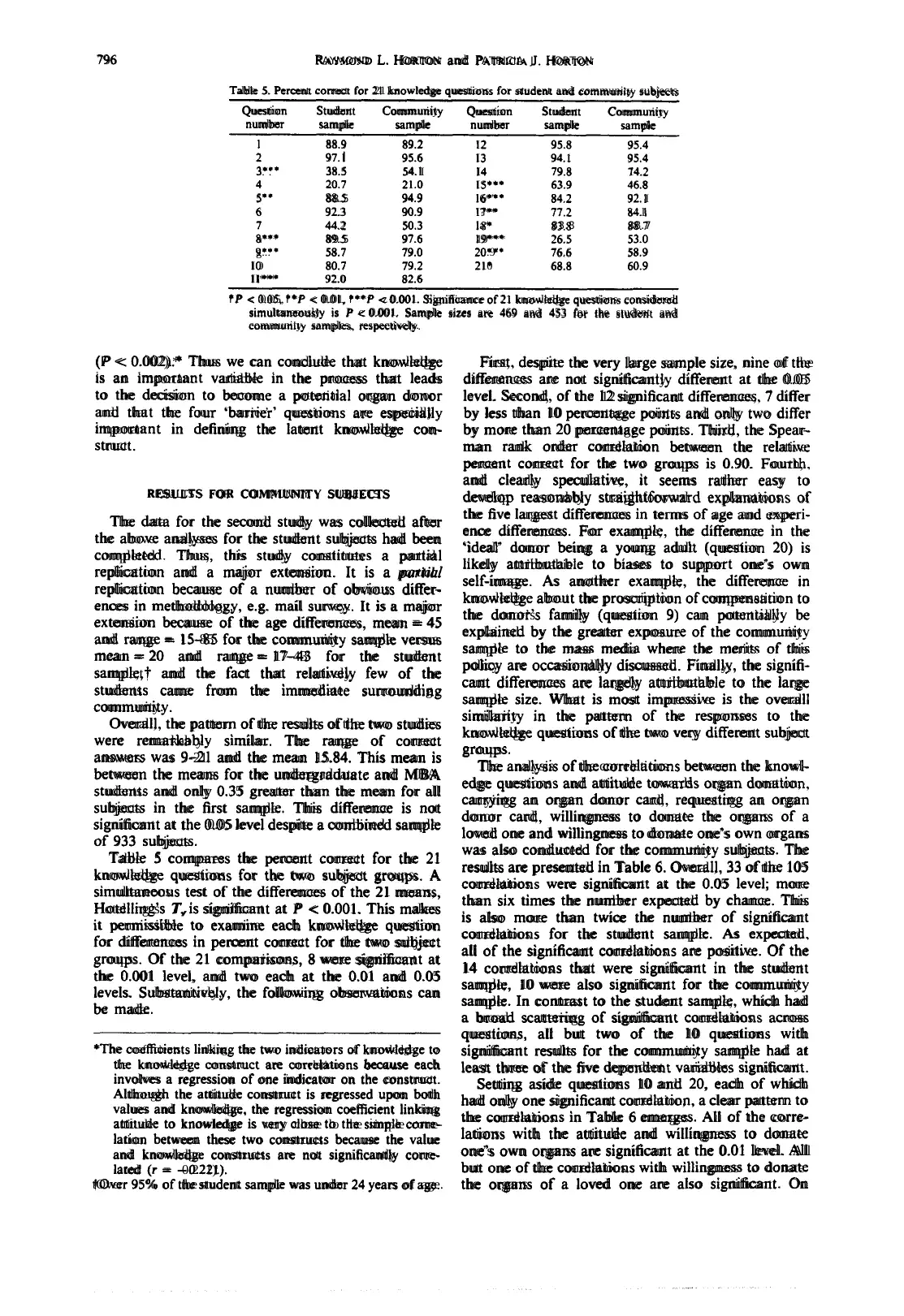

The third analysis is the subject of a separate paper

[ 181 and can only be briefly summarized here. This

analysis attempted to construct a model of the pro-

cess that leads to the decision to become a potential

organ donor. Figure I presents the model in

schematic form. Personal values and knowledge

about organ donation are postulated to lead to a

positive attitude towards organ donation which in

turn leads to an actual willingness to become a

potential organ donor and eventually to signing and

carrying an organ donor card. Because certain of the

measures, especially values and knowledge, are

known to have substantial measurement error, latent

variable modeling using the computer program LIS-

REL 7 [I91 was used to fit the theoretical model in

Fig. I to the data. The main advantage of LISREL

is that it corrects for attenuation of correlation

caused by measurement error and thus yields more

precise estimates of model parameters.

All of the hypothesized relationships among the

theoretical constructs and the measures of these

constructs were positive and significant beyond the

0.01 level. The knowledge portion of the model was

operationalized by aggregating the four ‘barrier’

questions and the remaining 17 knowledge questions

into two indicators of the latent knowledge construct.

The correlations between the two indicators and the

latent knowledge construct were 0.42 (P < 0.002) and

0.27 (P < 0.005) for the barrier and other questions,

respectively. The regression coefficient between the

latent knowledge and attitude constructs was 0.60

QValues

Fig. 1. Causal model of knowledge, values, attitude towards

organ donation, willingness to donate, and requesting

and/or carrying an organ donor card.

Table 4. Correlations bctwcen individual knowledge questions and attitude towards organ donation

(Attitude). carrying organ donor card (Card), rquesting organ donor card (Request), and willingness

to donate the organs of a loved one (Wol) and oneself (Wself)for student subjects

Variable

Knowledge question Attitude Card Request Wol Wself

No. I-Uniform Gift Act 0.144***

(MO)

No. 3-Religious support 0.159’.

(288)

No. 5-Open casket 0.124.’

(290)

No. g-Age greater than 40 0.106” 0.i29”

(41) (290)

No. 9-Benefit 0.100**

(460)

No. IbFuncral 0.152*** 0.134”

(61) (334)

No. 18-Presumed consent -0.120**

(290)

No. l9-File with HHS 0.202”’ 0.390*** 0.170’** 0.201*** 0.251***

(41) (288) (334) (289) (287)

l P < 0.05, l *P < 0.01, l **P < 0.001. Sample size in parentheses below correlation. Only correlations

significant at the 0.05 level are rcportcd. The correlationsbetween individual questions and card

and rcquat measures arc Kendall’s Tau B. For the prcseot data, these correlations arc identical

to Pearson product-moment correlations. The significance values, however, are slightly different

from the values that would bc calculated under the assumptions of Pearson product-moment

correlations. For details see Conover [29). All other correlations are Pearson product-moment

795

correlations.

preexperimental subjects have uniformly lower corre-

lations than the other three groups. This difference

with the MBA students may reflect the greater ex-

posure of MBAs to the mass media. The difference

with the experimental undergraduate subjects may be

due to the fact that data for the experimental groups

was collected approx. 12-18 months after the data

collection for preexperimental subjects. During this

time period information regarding organ donation

may have diffused more widely. Although only one of

the correlations for the MBA group is significant,

largely because of the very small sample size, the

magnitude of these correlations are generally close to

the correlations for the two experimental groups. All

of the correlations for the two experimental groups

are significant with most being highly significant.

Second, the above analysis was repeated with each

individual knowledge question to probe more fully

the consequences of specific gaps in knowledge re-

garding organ donation. To keep the total number of

correlations from becoming inordinately large, the

four subject groups were aggregated. Table 4 presents

the results for correlations significant at the 0.05 level.

Fourteen of I05 correlations were significant at the

0.05 level. This is almost three times the number of

significant results that would be expected by chance.

Except for question 19, the significant correlations

are small and scattered across questions. Interest-

ingly, all five correlations with question I9 are highly

significant and among the largest found in this study.

These relationships are especially important because

the question-For an organ donor card to be valid,

a copy must be filed with the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services-suggests a very specific

perceived barrier to organ donation.

The third analysis is the subject of a separate paper

[ 181 and can only be briefly summarized here. This

analysis attempted to construct a model of the pro-

cess that leads to the decision to become a potential

organ donor. Figure I presents the model in

schematic form. Personal values and knowledge

about organ donation are postulated to lead to a

positive attitude towards organ donation which in

turn leads to an actual willingness to become a

potential organ donor and eventually to signing and

carrying an organ donor card. Because certain of the

measures, especially values and knowledge, are

known to have substantial measurement error, latent

variable modeling using the computer program LIS-

REL 7 [I91 was used to fit the theoretical model in

Fig. I to the data. The main advantage of LISREL

is that it corrects for attenuation of correlation

caused by measurement error and thus yields more

precise estimates of model parameters.

All of the hypothesized relationships among the

theoretical constructs and the measures of these

constructs were positive and significant beyond the

0.01 level. The knowledge portion of the model was

operationalized by aggregating the four ‘barrier’

questions and the remaining 17 knowledge questions

into two indicators of the latent knowledge construct.

The correlations between the two indicators and the

latent knowledge construct were 0.42 (P < 0.002) and

0.27 (P < 0.005) for the barrier and other questions,

respectively. The regression coefficient between the

latent knowledge and attitude constructs was 0.60

QValues

Fig. 1. Causal model of knowledge, values, attitude towards

organ donation, willingness to donate, and requesting

and/or carrying an organ donor card.

796 RAYMOND L. HORTON and PATRICIA J. HORTON

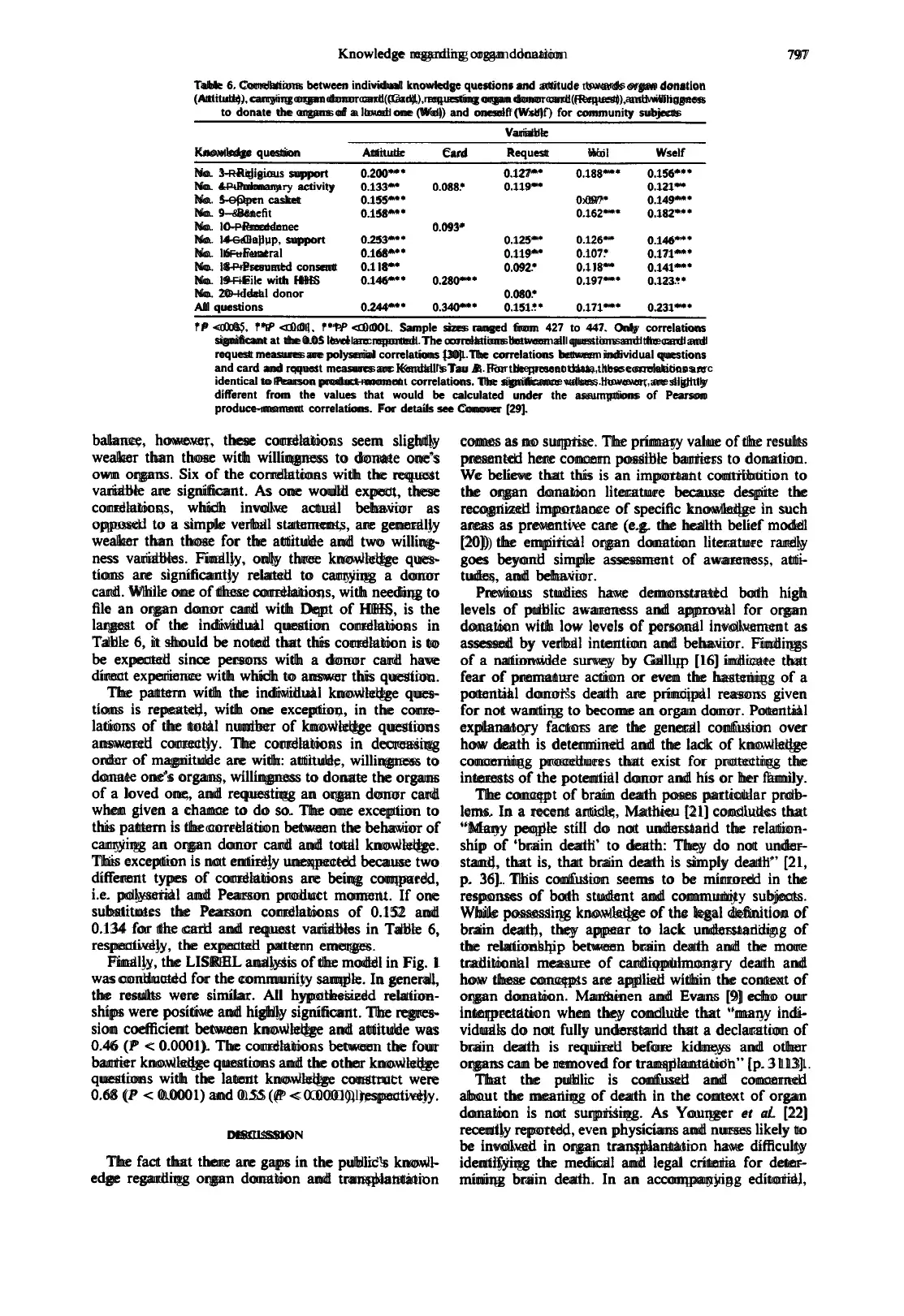

Table 5. Percent correct for 21 knowledge questions for student and community subjects

Question Student Community Question Student Community

number sample sample number sample samulc

I 88.9 89.2 I2 95.8 95.4

2 97. I 95.6 I3 94.1 95.4

3.‘. 38.5 54. I I4 79.8 14.2

4 20.7 21.0 IS*** 63.9 46.8

5” 88.5 94.9 l6*” 84.2 92. I

6 92.3 90.9 I?** 77.2 a4.l

7 44.2 50.3 la* 83.8 88.7

a*** 89.5 97.6 19*** 26.5 53.0

g... 58.7 79.0 20.9’ 76.6 58.9

IO 80.7 79.2 210 68.8 60.9

II*** 92.0 82.6

l P < 0.05, l *f < 0.01, l **f -z 0.001. Significance of 21 knowledge questions considered

simultaneously is P c 0.001. Sample sizes are 469 and 453 for the student and

community samples, respectively.

(P < 0.002).* Thus we can conclude that knowledge

is an important variable in the process that leads

to the decision to become a potential organ donor

and that the four ‘barrier’ questions are especially

important in defining the latent knowledge con-

struct.

RESULTS FOR COIMMUNITY SUBJECTS

The data for the second study was collected after

the above analyses for the student subjects had been

completed. Thus, this study constitutes a partial

replication and a major extension. It is a partial

replication because of a number of obvious differ-

ences in methodology, e.g. mail survey. It is a major

extension because of the age differences, mean = 45

and range = 15-85 for the community sample versus

mean = 20 and range = 17-43 for the student

sample,t and the fact that relatively few of the

students came from the immediate surrounding

community.

Overall, the pattern of the results of the two studies

were remarkably similar. The range of correct

answers was 9-21 and the mean 15.84. This mean is

between the means for the undergraduate and MBA

students and only 0.35 greater than the mean for all

subjects in the first sample. This difference is not

significant at the 0.05 level despite a combined sample

of 933 subjects.

Table 5 compares the percent correct for the 21

knowledge questions for the two subject groups. A

simultaneous test of the differences of the 21 means,

Hotelling’s T,is significant at P < 0.001. This makes

it permissible to examine each knowledge question

for differences in percent correct for the two subject

groups. Of the 21 comparisons, 8 were significant at

the 0.001 level, and two each at the 0.01 and 0.05

levels. Substantively, the following observations can

be made.

*The coefficients linking the two indicators of knowledge to

the knowledge construct are correlations because each

involves a regression of one indicator on the construct.

Although the attitude construct is regressed upon both

values and knowledge, the regression coefficient linking

attitude to knowledge is very close lo the simple cotre-

lation between these two constructs because the value

and knowledge constructs are not significantly corre-

lated (r = -0.221).

tOver 95% of the student sample was under 24 years of age.

First, despite the very large sample size, nine of the

differences are not significantly different at the 0.05

level. Second, of the 12 significant differences, 7 differ

by less than 10 percentage points and only two differ

by more than 20 percentage points. Third, the Spear-

man rank order correlation between the relative

percent correct for the two groups is 0.90. Fourth,

and clearly speculative, it seems rather easy to

develop reasonably straightforward explanations of

the five largest differences in terms of age and experi-

ence differences. For example, the difference in the

‘ideal’ donor being a young adult (question 20) is

likely attributabie to biases to support one’s own

self-image. As another example, the difference in

knowledge about the proscription of compensation to

the donor’s family (question 9) can potentially be

explained by the greater exposure of the community

sample to the mass media where the merits of this

policy are occasionally discussed. Finally, the signifi-

cant differences are largely attributable to the large

sample size. What is most impressive is the overall

similarity in the pattern of the responses to the

knowledge questions of the two very different subject

groups.

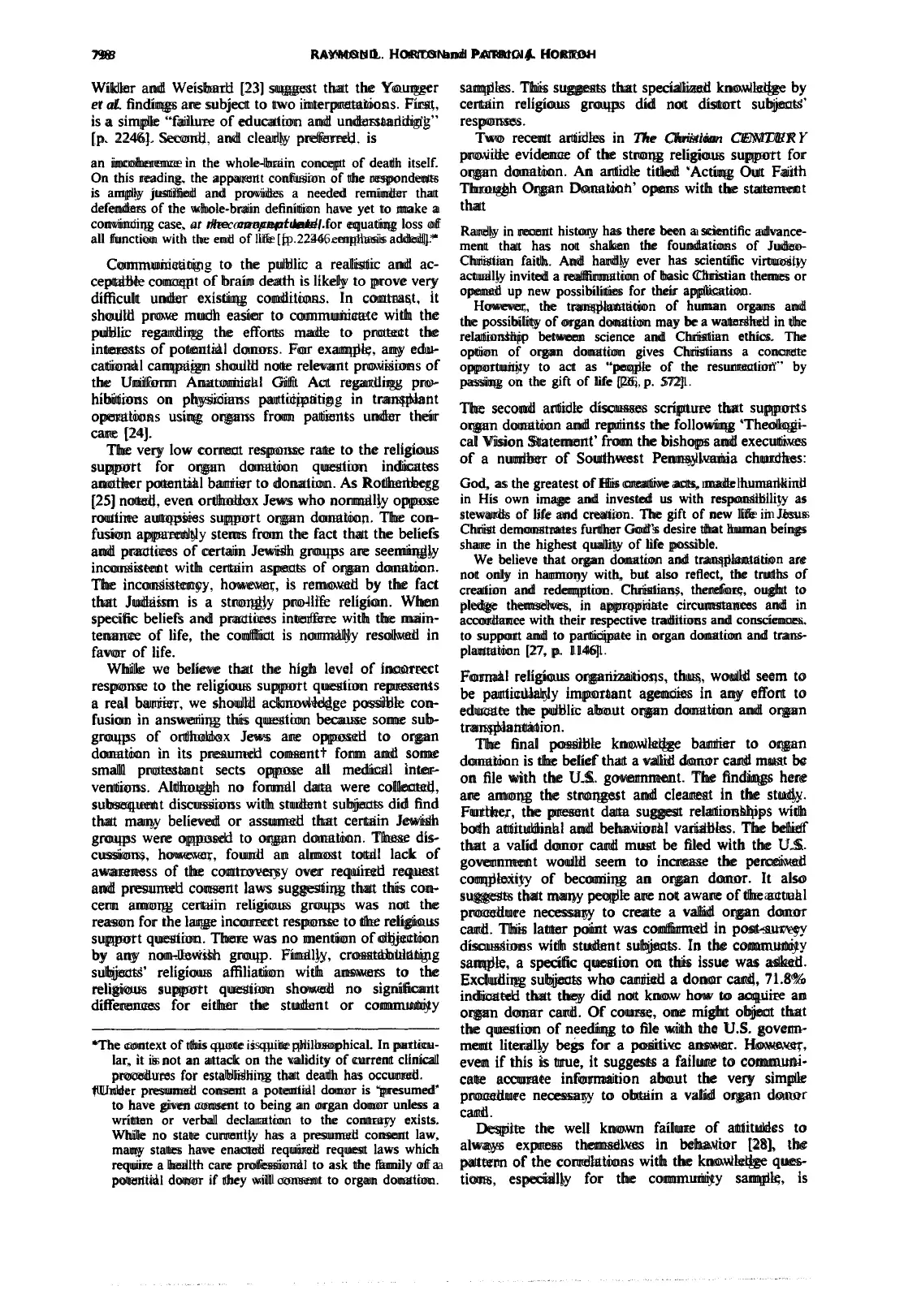

The analysis of the correlations between the knowl-

edge questions and attitude towards organ donation,

carrying an organ donor card, requesting an organ

donor card, willingness to donate the organs of a

loved one and willingness to donate one’s own organs

was also conducted for the community subjects. The

results are presented in Table 6. Overall, 33 of the 105

correlations were significant at the 0.05 level; more

than six times the number expected by chance. This

is also more than twice the number of significant

correlations for the student sample. As expected.

all of the significant correlations are positive. Of the

14 correlations that were significant in the student

sample, 10 were also significant for the community

sample. In contrast to the student sample, which had

a broad scattering of significant correlations across

questions, all but two of the 10 questions with

significant results for the community sample had at

least three of the five dependent variables significant.

Setting aside questions 10 and 20, each of which

had only one significant correlation, a clear pattern to

the correlations in Table 6 emerges. All of the corre-

lations with the attitude and willingness to donate

one’s own organs are significant at the 0.01 level. All

but one of the correlations with willingness to donate

the organs of a loved one are also significant. On

Table 5. Percent correct for 21 knowledge questions for student and community subjects

Question Student Community Question Student Community

number sample sample number sample samulc

I 88.9 89.2 I2 95.8 95.4

2 97. I 95.6 I3 94.1 95.4

3.‘. 38.5 54. I I4 79.8 14.2

4 20.7 21.0 IS*** 63.9 46.8

5” 88.5 94.9 l6*” 84.2 92. I

6 92.3 90.9 I?** 77.2 a4.l

7 44.2 50.3 la* 83.8 88.7

a*** 89.5 97.6 19*** 26.5 53.0

g... 58.7 79.0 20.9’ 76.6 58.9

IO 80.7 79.2 210 68.8 60.9

II*** 92.0 82.6

l P < 0.05, l *f < 0.01, l **f -z 0.001. Significance of 21 knowledge questions considered

simultaneously is P c 0.001. Sample sizes are 469 and 453 for the student and

community samples, respectively.

(P < 0.002).* Thus we can conclude that knowledge

is an important variable in the process that leads

to the decision to become a potential organ donor

and that the four ‘barrier’ questions are especially

important in defining the latent knowledge con-

struct.

RESULTS FOR COIMMUNITY SUBJECTS

The data for the second study was collected after

the above analyses for the student subjects had been

completed. Thus, this study constitutes a partial

replication and a major extension. It is a partial

replication because of a number of obvious differ-

ences in methodology, e.g. mail survey. It is a major

extension because of the age differences, mean = 45

and range = 15-85 for the community sample versus

mean = 20 and range = 17-43 for the student

sample,t and the fact that relatively few of the

students came from the immediate surrounding

community.

Overall, the pattern of the results of the two studies

were remarkably similar. The range of correct

answers was 9-21 and the mean 15.84. This mean is

between the means for the undergraduate and MBA

students and only 0.35 greater than the mean for all

subjects in the first sample. This difference is not

significant at the 0.05 level despite a combined sample

of 933 subjects.

Table 5 compares the percent correct for the 21

knowledge questions for the two subject groups. A

simultaneous test of the differences of the 21 means,

Hotelling’s T,is significant at P < 0.001. This makes

it permissible to examine each knowledge question

for differences in percent correct for the two subject

groups. Of the 21 comparisons, 8 were significant at

the 0.001 level, and two each at the 0.01 and 0.05

levels. Substantively, the following observations can

be made.

*The coefficients linking the two indicators of knowledge to

the knowledge construct are correlations because each

involves a regression of one indicator on the construct.

Although the attitude construct is regressed upon both

values and knowledge, the regression coefficient linking

attitude to knowledge is very close lo the simple cotre-

lation between these two constructs because the value

and knowledge constructs are not significantly corre-

lated (r = -0.221).

tOver 95% of the student sample was under 24 years of age.

First, despite the very large sample size, nine of the

differences are not significantly different at the 0.05

level. Second, of the 12 significant differences, 7 differ

by less than 10 percentage points and only two differ

by more than 20 percentage points. Third, the Spear-

man rank order correlation between the relative

percent correct for the two groups is 0.90. Fourth,

and clearly speculative, it seems rather easy to

develop reasonably straightforward explanations of

the five largest differences in terms of age and experi-

ence differences. For example, the difference in the

‘ideal’ donor being a young adult (question 20) is

likely attributabie to biases to support one’s own

self-image. As another example, the difference in

knowledge about the proscription of compensation to

the donor’s family (question 9) can potentially be

explained by the greater exposure of the community

sample to the mass media where the merits of this

policy are occasionally discussed. Finally, the signifi-

cant differences are largely attributable to the large

sample size. What is most impressive is the overall

similarity in the pattern of the responses to the

knowledge questions of the two very different subject

groups.

The analysis of the correlations between the knowl-

edge questions and attitude towards organ donation,

carrying an organ donor card, requesting an organ

donor card, willingness to donate the organs of a

loved one and willingness to donate one’s own organs

was also conducted for the community subjects. The

results are presented in Table 6. Overall, 33 of the 105

correlations were significant at the 0.05 level; more

than six times the number expected by chance. This

is also more than twice the number of significant

correlations for the student sample. As expected.

all of the significant correlations are positive. Of the

14 correlations that were significant in the student

sample, 10 were also significant for the community

sample. In contrast to the student sample, which had

a broad scattering of significant correlations across

questions, all but two of the 10 questions with

significant results for the community sample had at

least three of the five dependent variables significant.

Setting aside questions 10 and 20, each of which

had only one significant correlation, a clear pattern to

the correlations in Table 6 emerges. All of the corre-

lations with the attitude and willingness to donate

one’s own organs are significant at the 0.01 level. All

but one of the correlations with willingness to donate

the organs of a loved one are also significant. On

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Knowledge regarding organ donation

Table 6. Correlations bctwcen individual knowledge questions and attitude towards organ donation

(Attitude), carrying organ donor card (Card), requesting organ donor card (Request), and willingness

to donate the organs of a loved one (Wol) and oneself (Wxlf) for community subjects

Variable

Knowledge question Attitude Card Request woi Wself

No. 3-Religious support 0.200”* 0.127** 0.188*** 0.156*‘*

No. &Pulmonary activity 0.133** 0.088. 0.119** 0.121**

No. 5-Open casket 0.155*** 0x97* 0.149***

No. 9--&r&t 0.158*** 0.162*** 0.182’**

No. IO-Precedence 0.093*

No. I4-Gallup, support 0.253*** 0.125** 0.126** 0.146’”

No. lbFuneral 0.168**’ 0.119** 0.107. 0.171***

No. l8-Presumed consent 0.1 l8** 0.092. 0.1 l8** 0.141***

No. l9-File with HHS 0.146**’ 0.280*** 0.197*** 0.123..

No. ZO-Ideal donor 0.080.

All questions 0.244*** 0.340*** 0.151.. 0.171*** 0.231***

l P ~0.05, l *P <O.Ol, l *‘P <O.OOl. Sample sizes ranged from 427 to 447. Only correlations

significant at the 0.05 level arc reported. The correlations between all questions and the card and

request measures are polyserial correlations 1301. The correlations between individual questions

and card and rquest mcasurcs arc Kendall’s Tau B. For the present data, these correlations arc

identical to Pearson product-moment correlations. The significance values. however, are slightly

different from the values that would be calculated under the assumptions of Pearson

produce-moment correlations. For details see Conover [29].

797

balance, however, these correlations seem slightly

weaker than those with willingness to donate one’s

own organs. Six of the correlations with the request

variable are significant. As one would expect, these

correlations, which involve actual behavior as

opposed to a simple verbal statements, are generally

weaker than those for the attitude and two willing-

ness variables. Finally, only three knowledge ques-

tions are significantly related to carrying a donor

card. While one of these correlations, with needing to

file an organ donor card with Dept of HHS, is the

largest of the individual question correlations in

Table 6, it should be noted that this correlation is to

be expected since persons with a donor card have

direct experience with which to answer this question.

The pattern with the individual knowledge ques-

tions is repeated, with one exception, in the corre-

lations of the total number of knowledge questions

answered correctly. The correlations in decreasing

order of magnitude are with: attitude, willingness to

donate one’s organs, willingness to donate the organs

of a loved one, and requesting an organ donor card

when given a chance to do so. The one exception to

this pattern is the correlation between the behavior of

carrying an organ donor card and total knowledge.

This exception is not entirely unexpected because two

different types of correlations are being compared,

i.e. polyserial and Pearson product moment. If one

substitutes the Pearson correlations of 0.152 and

0.134 for the card and request variables in Table 6,

respectively, the expected pattern emerges.

Finally, the LISREL analysis of the model in Fig. 1

was conducted for the community sample. In general,

the results were similar. All hypothesized relation-

ships were positive and highly significant. The regres-

sion coefficient between knowledge and attitude was

0.46 (P < 0.0001). The correlations between the four

barrier knowledge questions and the other knowledge

questions with the latent knowledge construct were

0.68 (P < 0.0001) and 0.55 (P < O.OOOl),respectively.

DISCUSSION

The fact that there are gaps in the public’s knowl-

edge regarding organ donation and transplantation

comes as no surprise. The primary value of the results

presented here concern possible barriers to donation.

We believe that this is an important contribution to

the organ donation literature because despite the

recognized importance of specific knowledge in such

areas as preventive care (e.g. the health belief model

(201) the empirical organ donation literature rarely

goes beyond simple assessment of awareness, atti-

tudes, and behavior.