Patient-Specific Surgical Guides: A Literature Review Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/12

|21

|14384

|170

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a systematic literature review on the application of rapid prototyping (RP) in the creation of patient-specific surgical guides (PSGs) for various orthopaedic procedures. The review analyzes clinical and experimental studies, focusing on quantifiable outcomes, design details, and manufacturing processes of RP-PSGs. The research addresses key questions regarding the increasing use of RP-PSGs, their efficiency in terms of accuracy, time-saving, and cost-effectiveness, the preferred RP processes, and the critical design aspects. The findings highlight the advantages of RP-PSGs, such as reduced operating times and improved surgical accuracy, while also discussing potential disadvantages and sources of error. Stereolithography is identified as the primary RP process, with emerging applications in complex extremity surgeries, including spinal surgery and procedures on the forearm and foot. The review underscores the importance of cooperation between engineers and medical specialists in the development and use of RP-PSGs and aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of their use, design, manufacturing process, and potential for future enhancements in surgical applications. The review excluded studies on TKA and cranio-maxillofacial applications due to the availability of comprehensive surveys.

Review Article

Proc IMechE Part H:

J Engineering in Medicine

2016, Vol. 230(6) 495–515

Ó IMechE 2016

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0954411916636919

pih.sagepub.com

Rapid prototyping for patient-specific

surgical orthopaedics guides: A

systematic literature review

Diana Popescu and Dan Laptoiu

Abstract

There has been a lot of hype surrounding the advantages to be gained from rapid prototyping processes in

fields,including medicine.Our literature review aims objectively to assess how effective patient-specific surgicalguides

manufactured using rapid prototyping are in a number of orthopaedic surgical applications. To this end, we

systematic review to identify and analyse clinicaland experimentalliterature studies in which rapid prototyping patient-

specific surgical guides are used, focusing especially on those that entail quantifiable outcomes and, at the

viding details on the guides’design and type ofmanufacturing process.Here,it should be mentioned that in this field

there are not yet medium- or long-term data,and no information on revisions.In the reviewed studies,the reported

positive opinions on the use of rapid prototyping patient-specific surgicalguides relate to the following main advantages:

reduction in operating times, low costs and improvements in the accuracy of surgical interventions thanks

sonalisation.However,disadvantages and sources of errors which can cause patient-specific surgicalguide failures are as

well discussed by authors.Stereolithography is the main rapid prototyping process employed in these applicat

although fused deposition modelling or selective laser sintering processes can also satisfy the requirementthese

applications in terms of materialproperties,manufacturing accuracy and construction time.Another of our findings was

that individualised drill guides for spinal surgery are currently the favourite candidates for manufacture us

typing.Other emerging applications relate to complex orthopaedic surgery ofthe extremities:the forearm and foot.

Severalprocedures such as osteotomies for radius malunions or tarsalcoalition could become standard,thanks to the

significantassistance provided by rapid prototyping patient-specific surgicalguides in planning and performing such

operations.

Keywords

Patient-specific guide, rapid prototyping, orthopaedic instrumentation, computer-aided surgery

Date received: 1 October 2015; accepted: 3 February 2016

Introduction

Rapid prototyping (RP)is a group of manufacturing

processes that can build physicalobjects directly from

three-dimensional(3D) virtualmodeldata in an addi-

tive way,which is to say,by superimposing layers of

material one on top of the other. Other terms used for

this kind of processes are layer manufacturing,layer

fabrication,solid freeform fabrication and layer-by-

layer fabrication. Since 2013, the standard name, addi-

tive manufacturing (AM) has been defined as ‘the pro-

cessof joining materialsto make objectsfrom 3D

modeldata,usually layer upon layer,as opposed to

subtractive manufacturing technologies’.1 However, the

analysiscarried outfor this article showed thatthe

term RP is used more often in the medical literature, as

the advantages offered by such processes are in direct

correlation to surgical guides’ individualisation, that is,

the concept of a prototype.

Personalised healthcare is becoming an increasingly

salientapproach to medicine,2 and advances in both

medicaland technicalfields are being focused on pro-

viding solutions for medicalinterventions and devices

Politehnica University of Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania

Orthopaedics, Clinical Hospital Colentina, Bucharest, Romania

Chelariu Clinic, Bacau, Romania

Corresponding author:

Dan Laptoiu, Orthopaedics, Clinical Hospital Colentina, Sos. Stefan cel

Mare, 19-21, code 020125 Sector 2, Bucharest, Romania.

Email: danlaptoiu@yahoo.com

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Proc IMechE Part H:

J Engineering in Medicine

2016, Vol. 230(6) 495–515

Ó IMechE 2016

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0954411916636919

pih.sagepub.com

Rapid prototyping for patient-specific

surgical orthopaedics guides: A

systematic literature review

Diana Popescu and Dan Laptoiu

Abstract

There has been a lot of hype surrounding the advantages to be gained from rapid prototyping processes in

fields,including medicine.Our literature review aims objectively to assess how effective patient-specific surgicalguides

manufactured using rapid prototyping are in a number of orthopaedic surgical applications. To this end, we

systematic review to identify and analyse clinicaland experimentalliterature studies in which rapid prototyping patient-

specific surgical guides are used, focusing especially on those that entail quantifiable outcomes and, at the

viding details on the guides’design and type ofmanufacturing process.Here,it should be mentioned that in this field

there are not yet medium- or long-term data,and no information on revisions.In the reviewed studies,the reported

positive opinions on the use of rapid prototyping patient-specific surgicalguides relate to the following main advantages:

reduction in operating times, low costs and improvements in the accuracy of surgical interventions thanks

sonalisation.However,disadvantages and sources of errors which can cause patient-specific surgicalguide failures are as

well discussed by authors.Stereolithography is the main rapid prototyping process employed in these applicat

although fused deposition modelling or selective laser sintering processes can also satisfy the requirementthese

applications in terms of materialproperties,manufacturing accuracy and construction time.Another of our findings was

that individualised drill guides for spinal surgery are currently the favourite candidates for manufacture us

typing.Other emerging applications relate to complex orthopaedic surgery ofthe extremities:the forearm and foot.

Severalprocedures such as osteotomies for radius malunions or tarsalcoalition could become standard,thanks to the

significantassistance provided by rapid prototyping patient-specific surgicalguides in planning and performing such

operations.

Keywords

Patient-specific guide, rapid prototyping, orthopaedic instrumentation, computer-aided surgery

Date received: 1 October 2015; accepted: 3 February 2016

Introduction

Rapid prototyping (RP)is a group of manufacturing

processes that can build physicalobjects directly from

three-dimensional(3D) virtualmodeldata in an addi-

tive way,which is to say,by superimposing layers of

material one on top of the other. Other terms used for

this kind of processes are layer manufacturing,layer

fabrication,solid freeform fabrication and layer-by-

layer fabrication. Since 2013, the standard name, addi-

tive manufacturing (AM) has been defined as ‘the pro-

cessof joining materialsto make objectsfrom 3D

modeldata,usually layer upon layer,as opposed to

subtractive manufacturing technologies’.1 However, the

analysiscarried outfor this article showed thatthe

term RP is used more often in the medical literature, as

the advantages offered by such processes are in direct

correlation to surgical guides’ individualisation, that is,

the concept of a prototype.

Personalised healthcare is becoming an increasingly

salientapproach to medicine,2 and advances in both

medicaland technicalfields are being focused on pro-

viding solutions for medicalinterventions and devices

Politehnica University of Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania

Orthopaedics, Clinical Hospital Colentina, Bucharest, Romania

Chelariu Clinic, Bacau, Romania

Corresponding author:

Dan Laptoiu, Orthopaedics, Clinical Hospital Colentina, Sos. Stefan cel

Mare, 19-21, code 020125 Sector 2, Bucharest, Romania.

Email: danlaptoiu@yahoo.com

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

tailored to the patient’s bone morphology and individ-

ual needs.Patient-specific surgicalguides (PSGs)are

part of this approach,thus representing a subjectof

interest for both surgeons and engineers.

The use of RP processesto manufacture patient-

specific surgicalguides(RP-PSGs) specially designed

for a specific patient can be traced back in 1997, when

Van Brusselet al.3 reported the design,manufacture

and use of the first individualised template for drilling

trajectories when inserting pedicle screws into the verte-

bra of a human spine.In 1998,Radermacher etal.4

employed the stereolithography (SL) process to obtain

the physical prototype of a PSG for pelvic osteotomies.

Berry et al.5 also engaged in studies of image processing

methods, data conversion and manufacturing using the

selective laser sintering (SLS) process.Ever since then,

the number ofsuch applications has been increasing

thanks to a greater awareness of the advantages offered

by RP processes in manufacturing objects with compli-

cated geometricalfeatures (freeform features).This is

the case of PSGs designed to exactly fit the patient’s

anatomical structures, thus supporting increased preci-

sion in a number of surgical procedures.

The improvement in the accuracy of screw implanta-

tion techniques and other orthopaedic surgicalproce-

dures has been possible through the use of radiological

examination during surgery.The irradiation during

such proceduresis higher in percutaneoussurgery,

where,in order to make as small as possible incisions,

the use of interventionalradiology isrequired when

identifying anatomicallandmarks.Therefore, in recent

years,intra-operativenavigation systemshave been

developed and implemented in operating theatresin

order to visualisethe patient’sanatomicalstructure

without resortingto interventionalradiology.This

approach is based on pre-operative image acquisition

and on the use of an anatomical landmarks system cali-

brated atthe beginning ofthe surgicalintervention.

However, performing this calibration process is a com-

plicated task.Moreover,the static landmarksestab-

lished at the beginningof surgerydo not always

maintain thesameposition throughoutthe surgical

procedure,which obviously leadsto imprecision.In

this context,PSGs can representan alternative when

used for guiding surgicalactions such as drilling,tap-

ping, cutting or axis alignment, since they transfer to a

physicalobject (called guide,jig or template)the

planned trajectories required in order to prepare the

bones for the implantation and fixation of screws, rods

and plates.6 These guides can also help to identify the

correctposition/orientation ofinstrumentsor substi-

tute for an instrument,as is the case in totalknee

arthroplasty (TKA) applications,7 for instance.

The personalisation of surgical guides implies coop-

eration between engineers and medical specialists8 when

obtaining patient’s scan data, modelling the anatomical

areas of interest, planning the surgery/tool trajectories,

designing the guide,choosing the materialand manu-

facturing process,building the guide,and sterilising

and utilising it.The flow is similar for allPSGs, but

what differs is the design of the guides,which is dic-

tated by the patient’s anatomy, the type of intervention

and surgicalapproach,as well as by the anatomical

landmarks selected by the surgeon in the pre-operative

stage.Other requirements,such as transparency9 or

multi-level guides10,11for spinal applications, may also

be considered convenientsolutionsin some medical

cases.

However, despite reported cases of orthopaedic sur-

gicaloperations in which PSGs manufactured via RP

processes have been used, to the best of our knowledge

literaturereviews have been conductedonly for

TKA 7,12,13

and cranio-maxillofacialapplications.14 No

systematic information is yet available for other ortho-

paedic applications such as spinalsurgery or correc-

tions of malunions or deformitiespresentedin

literature.

In this context,this review addresses these applica-

tions, the information in the article being organised so

that to answer four questions. This approach represents

a modality to organise the information found when

querying the literature databases, the questions provid-

ing a structured and systematic manner to analyse the

data presented in RP-PSGsliterature studies.Thus,

these questions can be considered as filters applied for

screening the literature in the field. Moreover, these are

the questions that engineers and surgeons are first ask-

ing themselves when decide to start build and use such

devices.

These questions are as follows:

Q1. Has there been a significantconstantincrease in

the use of RP-PSGs in the last couple of years?

Q2. What is the reported efficiency (in terms of accu-

racy, operation time saving and costs) of RP-PSGs use

in orthopaedic surgery?

Q3. Is there a preferred RP process for manufacturing

such guides and, if so, why?

Q4. What are the main aspects taken into account dur-

ing the RP-PSGs design process?

The answers offered by our article aim to provide the

basisfor a more accurate understanding ofthe use,

design and manufacturing process, on one hand, and of

the advantages and pitfalls of RP-PSGs in several ortho-

paedicsurgeryinterventions,on other hand. Thus,

knowledge can be gathered and hopefully used for fur-

ther studies and enhancements in the field by providing

possible suggestions for improvements in PSGs and for

their use in other types of surgical applications.

Materials and methods

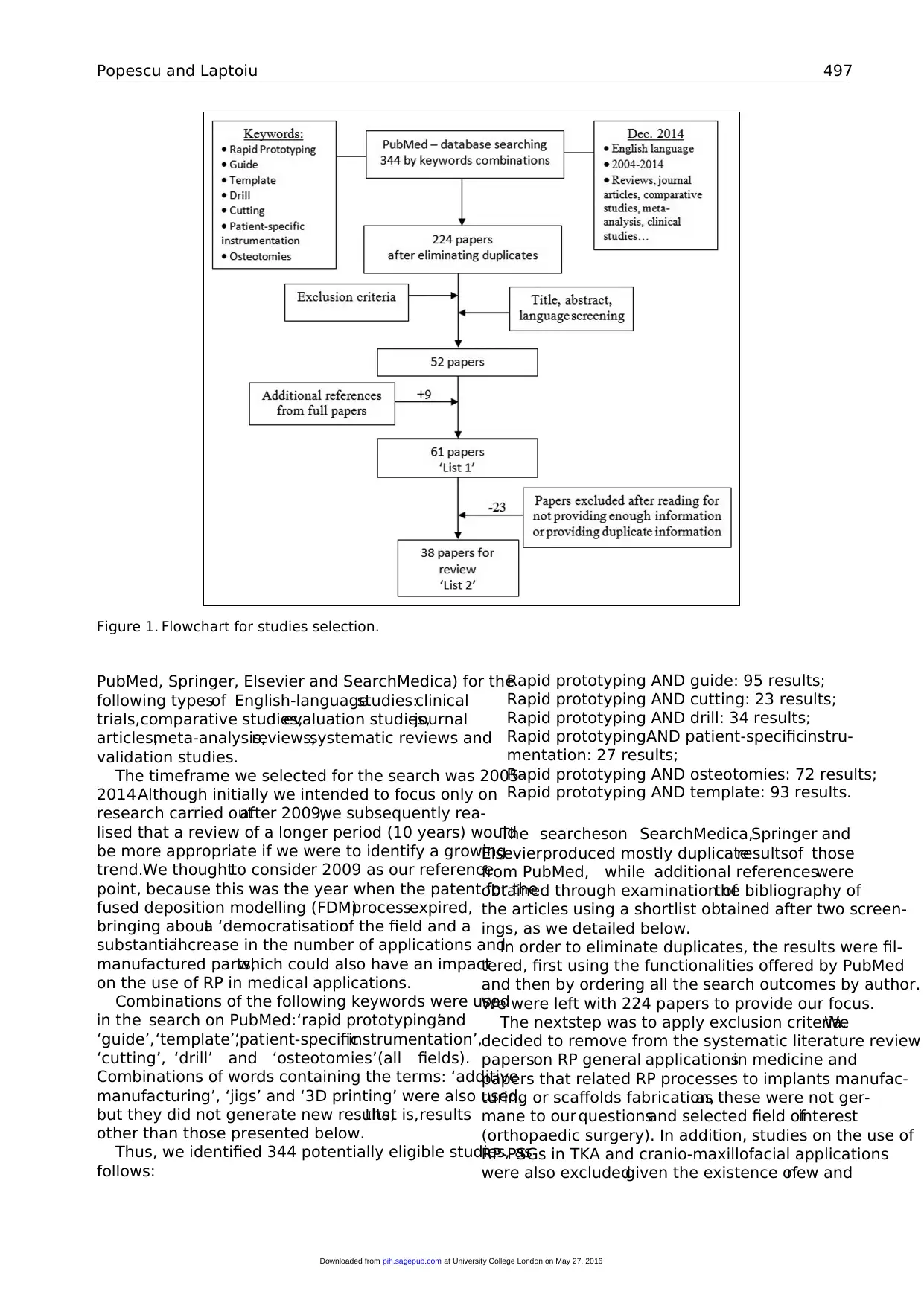

The systematic literature review was conducted based

on the flow presented in Figure 1.

In December2014,we searched the computerised

databases of medicaljournals (in the following order:

496 Proc IMechE Part H:J Engineering in Medicine 230(6)

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

ual needs.Patient-specific surgicalguides (PSGs)are

part of this approach,thus representing a subjectof

interest for both surgeons and engineers.

The use of RP processesto manufacture patient-

specific surgicalguides(RP-PSGs) specially designed

for a specific patient can be traced back in 1997, when

Van Brusselet al.3 reported the design,manufacture

and use of the first individualised template for drilling

trajectories when inserting pedicle screws into the verte-

bra of a human spine.In 1998,Radermacher etal.4

employed the stereolithography (SL) process to obtain

the physical prototype of a PSG for pelvic osteotomies.

Berry et al.5 also engaged in studies of image processing

methods, data conversion and manufacturing using the

selective laser sintering (SLS) process.Ever since then,

the number ofsuch applications has been increasing

thanks to a greater awareness of the advantages offered

by RP processes in manufacturing objects with compli-

cated geometricalfeatures (freeform features).This is

the case of PSGs designed to exactly fit the patient’s

anatomical structures, thus supporting increased preci-

sion in a number of surgical procedures.

The improvement in the accuracy of screw implanta-

tion techniques and other orthopaedic surgicalproce-

dures has been possible through the use of radiological

examination during surgery.The irradiation during

such proceduresis higher in percutaneoussurgery,

where,in order to make as small as possible incisions,

the use of interventionalradiology isrequired when

identifying anatomicallandmarks.Therefore, in recent

years,intra-operativenavigation systemshave been

developed and implemented in operating theatresin

order to visualisethe patient’sanatomicalstructure

without resortingto interventionalradiology.This

approach is based on pre-operative image acquisition

and on the use of an anatomical landmarks system cali-

brated atthe beginning ofthe surgicalintervention.

However, performing this calibration process is a com-

plicated task.Moreover,the static landmarksestab-

lished at the beginningof surgerydo not always

maintain thesameposition throughoutthe surgical

procedure,which obviously leadsto imprecision.In

this context,PSGs can representan alternative when

used for guiding surgicalactions such as drilling,tap-

ping, cutting or axis alignment, since they transfer to a

physicalobject (called guide,jig or template)the

planned trajectories required in order to prepare the

bones for the implantation and fixation of screws, rods

and plates.6 These guides can also help to identify the

correctposition/orientation ofinstrumentsor substi-

tute for an instrument,as is the case in totalknee

arthroplasty (TKA) applications,7 for instance.

The personalisation of surgical guides implies coop-

eration between engineers and medical specialists8 when

obtaining patient’s scan data, modelling the anatomical

areas of interest, planning the surgery/tool trajectories,

designing the guide,choosing the materialand manu-

facturing process,building the guide,and sterilising

and utilising it.The flow is similar for allPSGs, but

what differs is the design of the guides,which is dic-

tated by the patient’s anatomy, the type of intervention

and surgicalapproach,as well as by the anatomical

landmarks selected by the surgeon in the pre-operative

stage.Other requirements,such as transparency9 or

multi-level guides10,11for spinal applications, may also

be considered convenientsolutionsin some medical

cases.

However, despite reported cases of orthopaedic sur-

gicaloperations in which PSGs manufactured via RP

processes have been used, to the best of our knowledge

literaturereviews have been conductedonly for

TKA 7,12,13

and cranio-maxillofacialapplications.14 No

systematic information is yet available for other ortho-

paedic applications such as spinalsurgery or correc-

tions of malunions or deformitiespresentedin

literature.

In this context,this review addresses these applica-

tions, the information in the article being organised so

that to answer four questions. This approach represents

a modality to organise the information found when

querying the literature databases, the questions provid-

ing a structured and systematic manner to analyse the

data presented in RP-PSGsliterature studies.Thus,

these questions can be considered as filters applied for

screening the literature in the field. Moreover, these are

the questions that engineers and surgeons are first ask-

ing themselves when decide to start build and use such

devices.

These questions are as follows:

Q1. Has there been a significantconstantincrease in

the use of RP-PSGs in the last couple of years?

Q2. What is the reported efficiency (in terms of accu-

racy, operation time saving and costs) of RP-PSGs use

in orthopaedic surgery?

Q3. Is there a preferred RP process for manufacturing

such guides and, if so, why?

Q4. What are the main aspects taken into account dur-

ing the RP-PSGs design process?

The answers offered by our article aim to provide the

basisfor a more accurate understanding ofthe use,

design and manufacturing process, on one hand, and of

the advantages and pitfalls of RP-PSGs in several ortho-

paedicsurgeryinterventions,on other hand. Thus,

knowledge can be gathered and hopefully used for fur-

ther studies and enhancements in the field by providing

possible suggestions for improvements in PSGs and for

their use in other types of surgical applications.

Materials and methods

The systematic literature review was conducted based

on the flow presented in Figure 1.

In December2014,we searched the computerised

databases of medicaljournals (in the following order:

496 Proc IMechE Part H:J Engineering in Medicine 230(6)

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

PubMed, Springer, Elsevier and SearchMedica) for the

following typesof English-languagestudies:clinical

trials,comparative studies,evaluation studies,journal

articles,meta-analysis,reviews,systematic reviews and

validation studies.

The timeframe we selected for the search was 2005–

2014.Although initially we intended to focus only on

research carried outafter 2009,we subsequently rea-

lised that a review of a longer period (10 years) would

be more appropriate if we were to identify a growing

trend.We thoughtto consider 2009 as our reference

point, because this was the year when the patent for the

fused deposition modelling (FDM)processexpired,

bringing abouta ‘democratisation’of the field and a

substantialincrease in the number of applications and

manufactured parts,which could also have an impact

on the use of RP in medical applications.

Combinations of the following keywords were used

in the search on PubMed:‘rapid prototyping’and

‘guide’,‘template’,‘patient-specificinstrumentation’,

‘cutting’, ‘drill’ and ‘osteotomies’(all fields).

Combinations of words containing the terms: ‘additive

manufacturing’, ‘jigs’ and ‘3D printing’ were also used,

but they did not generate new results,that is,results

other than those presented below.

Thus, we identified 344 potentially eligible studies, as

follows:

Rapid prototyping AND guide: 95 results;

Rapid prototyping AND cutting: 23 results;

Rapid prototyping AND drill: 34 results;

Rapid prototypingAND patient-specificinstru-

mentation: 27 results;

Rapid prototyping AND osteotomies: 72 results;

Rapid prototyping AND template: 93 results.

The searcheson SearchMedica,Springer and

Elsevierproduced mostly duplicateresultsof those

from PubMed, while additional referenceswere

obtained through examination ofthe bibliography of

the articles using a shortlist obtained after two screen-

ings, as we detailed below.

In order to eliminate duplicates, the results were fil-

tered, first using the functionalities offered by PubMed

and then by ordering all the search outcomes by author.

We were left with 224 papers to provide our focus.

The nextstep was to apply exclusion criteria.We

decided to remove from the systematic literature review

paperson RP general applicationsin medicine and

papers that related RP processes to implants manufac-

turing or scaffolds fabrication,as these were not ger-

mane to our questionsand selected field ofinterest

(orthopaedic surgery). In addition, studies on the use of

RP-PSGs in TKA and cranio-maxillofacial applications

were also excluded,given the existence ofnew and

Figure 1. Flowchart for studies selection.

Popescu and Laptoiu 497

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

following typesof English-languagestudies:clinical

trials,comparative studies,evaluation studies,journal

articles,meta-analysis,reviews,systematic reviews and

validation studies.

The timeframe we selected for the search was 2005–

2014.Although initially we intended to focus only on

research carried outafter 2009,we subsequently rea-

lised that a review of a longer period (10 years) would

be more appropriate if we were to identify a growing

trend.We thoughtto consider 2009 as our reference

point, because this was the year when the patent for the

fused deposition modelling (FDM)processexpired,

bringing abouta ‘democratisation’of the field and a

substantialincrease in the number of applications and

manufactured parts,which could also have an impact

on the use of RP in medical applications.

Combinations of the following keywords were used

in the search on PubMed:‘rapid prototyping’and

‘guide’,‘template’,‘patient-specificinstrumentation’,

‘cutting’, ‘drill’ and ‘osteotomies’(all fields).

Combinations of words containing the terms: ‘additive

manufacturing’, ‘jigs’ and ‘3D printing’ were also used,

but they did not generate new results,that is,results

other than those presented below.

Thus, we identified 344 potentially eligible studies, as

follows:

Rapid prototyping AND guide: 95 results;

Rapid prototyping AND cutting: 23 results;

Rapid prototyping AND drill: 34 results;

Rapid prototypingAND patient-specificinstru-

mentation: 27 results;

Rapid prototyping AND osteotomies: 72 results;

Rapid prototyping AND template: 93 results.

The searcheson SearchMedica,Springer and

Elsevierproduced mostly duplicateresultsof those

from PubMed, while additional referenceswere

obtained through examination ofthe bibliography of

the articles using a shortlist obtained after two screen-

ings, as we detailed below.

In order to eliminate duplicates, the results were fil-

tered, first using the functionalities offered by PubMed

and then by ordering all the search outcomes by author.

We were left with 224 papers to provide our focus.

The nextstep was to apply exclusion criteria.We

decided to remove from the systematic literature review

paperson RP general applicationsin medicine and

papers that related RP processes to implants manufac-

turing or scaffolds fabrication,as these were not ger-

mane to our questionsand selected field ofinterest

(orthopaedic surgery). In addition, studies on the use of

RP-PSGs in TKA and cranio-maxillofacial applications

were also excluded,given the existence ofnew and

Figure 1. Flowchart for studies selection.

Popescu and Laptoiu 497

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

comprehensivesurveys.Nor werestudiespresenting

TKA surgical guide applications from companies such

as Smith and Nephew, Biomet and Zimmer included in

the survey in order to avoid presentation of potentially

biased information, and also because they are not offer-

ing too many technical details on the design aspects and

manufacturing process.Moreover,Thienpontet al.15

already presented a comprehensive survey (Europe and

worldwide)on patient-specificinstrumentationfor

TKA (including RP guides), based on information from

orthopaedic companies (2011–2012 volumes ofsales).

Therefore, we focused our review only on the cases pre-

sented in the literature as we consider that they can pro-

vide documented technicalinformation on different

aspects ofthe development,use and evaluation pro-

cesses of this type of surgical guides.

Papers with English titles that came up in the search

results,but which werewritten in other languages

(German,Chinese and Japanese) were also eliminated

from our list. We assumed that it was more than likely

that the results laid out in these papers had also been

published in English in various journals.

In the end, 52 studies were retained for further anal-

ysis. When filtering titles and abstracts, we noticed the

very large number of RP applications in manufacturing

PSGs for dental applications, an area better developed

than that of orthopaedic surgery.

In the next stageof filtering,the articleswere

reviewed in full by both authors independently,in

order to establish mutualagreement,especially given

that their separate fields of specialisation (engineering

and medicine)mightdetermine differentperspectives

on and understandings of the same subject. In addition,

a supplementary search was carried out using the refer-

ences found in the 52 articles,thereby generating nine

further papers relating to the subject.

Thus, a total of 61 studies presenting applications of

RP processes in the manufacturing of PSGs for ortho-

paedic surgery,in both clinicalcases and experiments

on cadavers, were selected for ‘List 1’. However, not all

of thesearticlescontained sufficientinformation or

outcomes(i.e. radiologicaldata for PSG usefulness

assessment,information on guide design,information

on computed tomography (CT)scanning protocols,

typesof RP process and materials)to answer our

questions.Furthermore,some of the articles presented

information or preliminary information that was later

repeated, in a more detailed manner, in other papers or

book chapters. For these reasons, 23 papers were elimi-

nated from ‘List 1’, and the remaining 38 articles

(named as ‘List 2’) are discussed separately in section

‘Discussion’.The articles in ‘List 2’were divided into

two broad categories:RP-PSGs for spinal surgery

applications (discussed in section ‘RP-PSGs for spinal

surgery applications’) and RP-PSGs for other general

orthopaedic surgery applications (osteotomies,tumour

resections, etc., discussed in section ‘RP-PSGs for gen-

eral orthopaedic surgery applications’).

In conclusion,the articles in ‘List1’ were used to

answer Q1 and Q2,and,in part,the other questions,

while the articles in ‘List 2’ provided a detailed exami-

nation of specific RP-PSGs design and manufacturing

criteria, diverse methods and approaches, reported effi-

ciency, thereby providing answers to Q3 and Q4.

Results

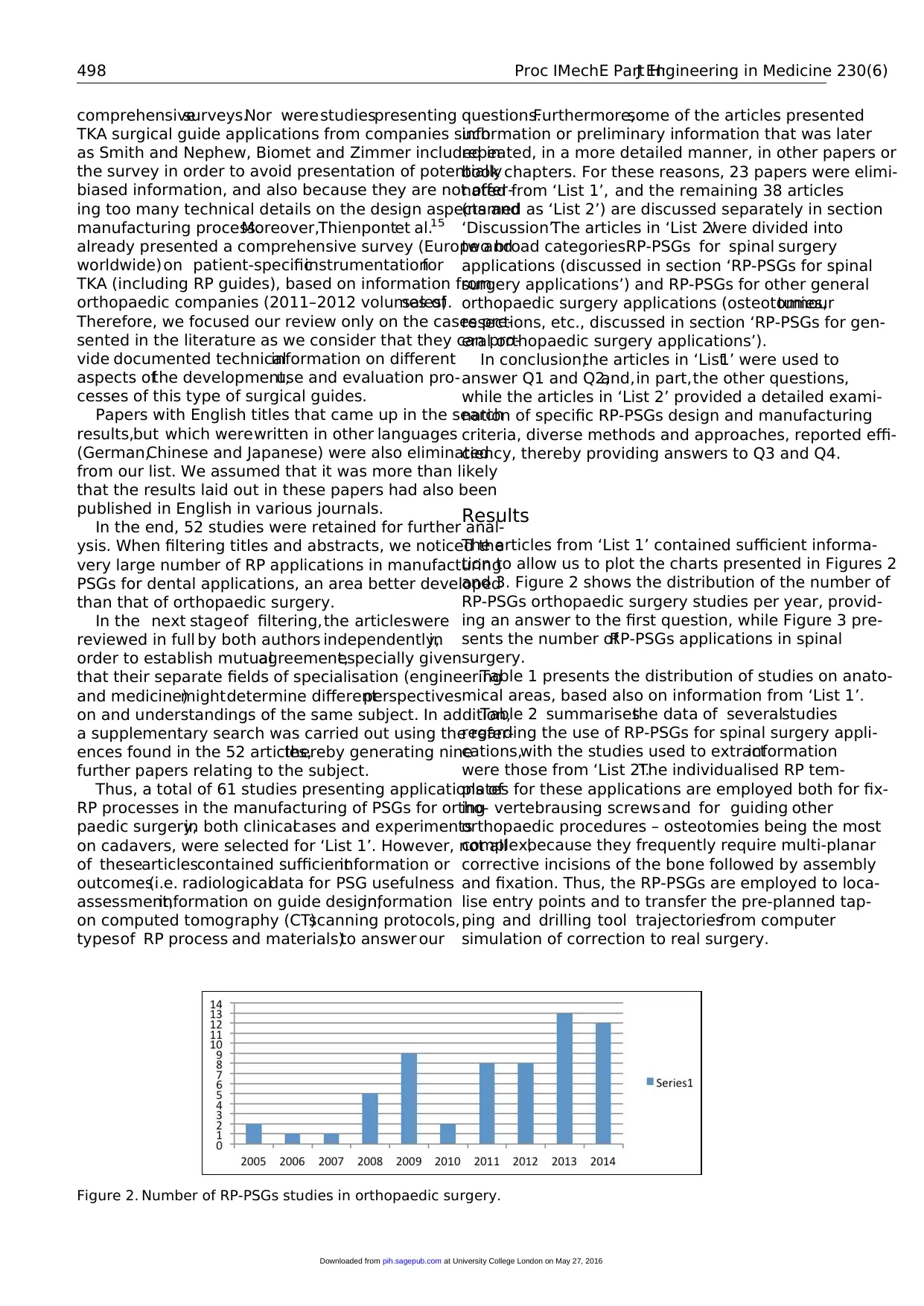

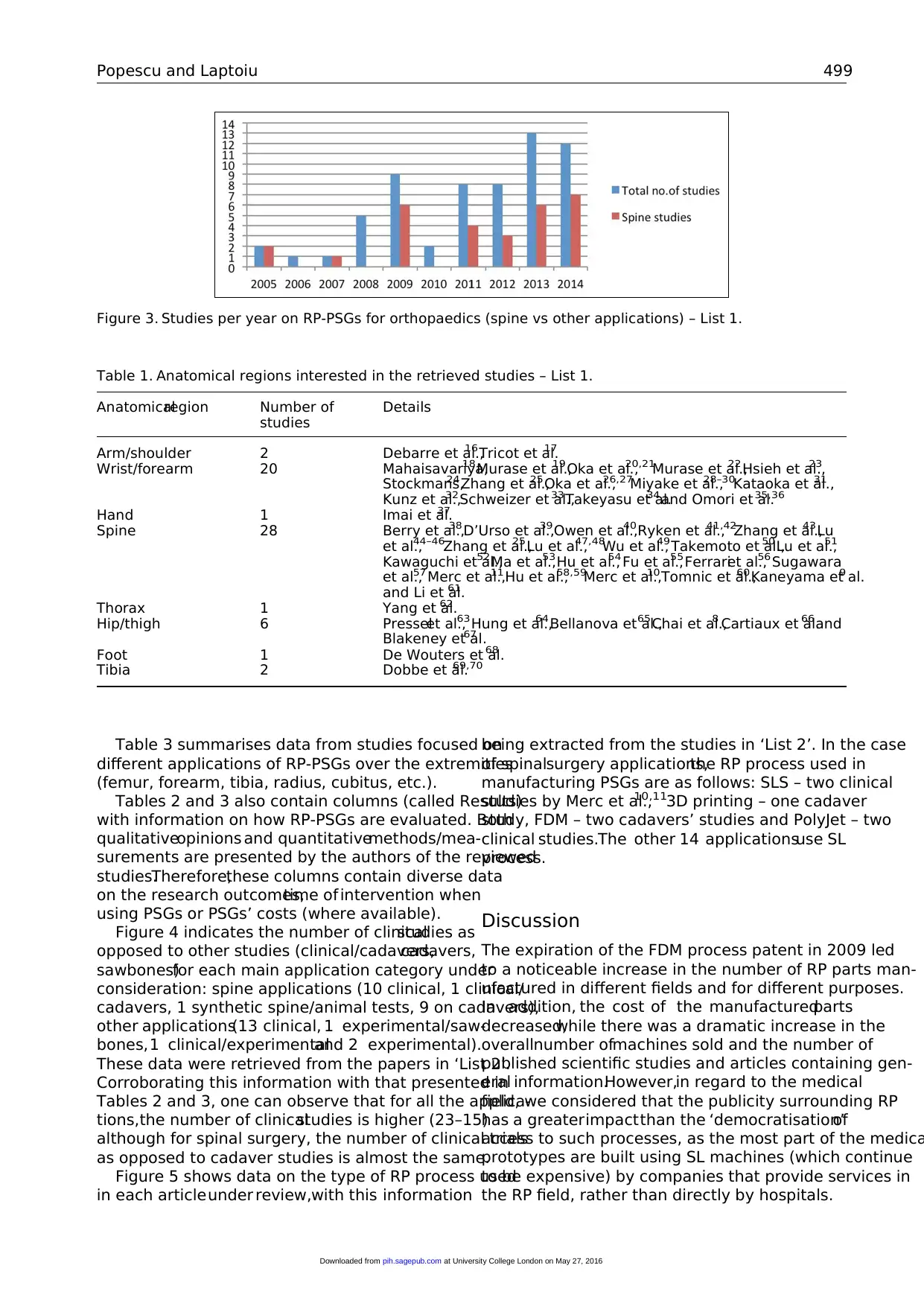

The articles from ‘List 1’ contained sufficient informa-

tion to allow us to plot the charts presented in Figures 2

and 3. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the number of

RP-PSGs orthopaedic surgery studies per year, provid-

ing an answer to the first question, while Figure 3 pre-

sents the number ofRP-PSGs applications in spinal

surgery.

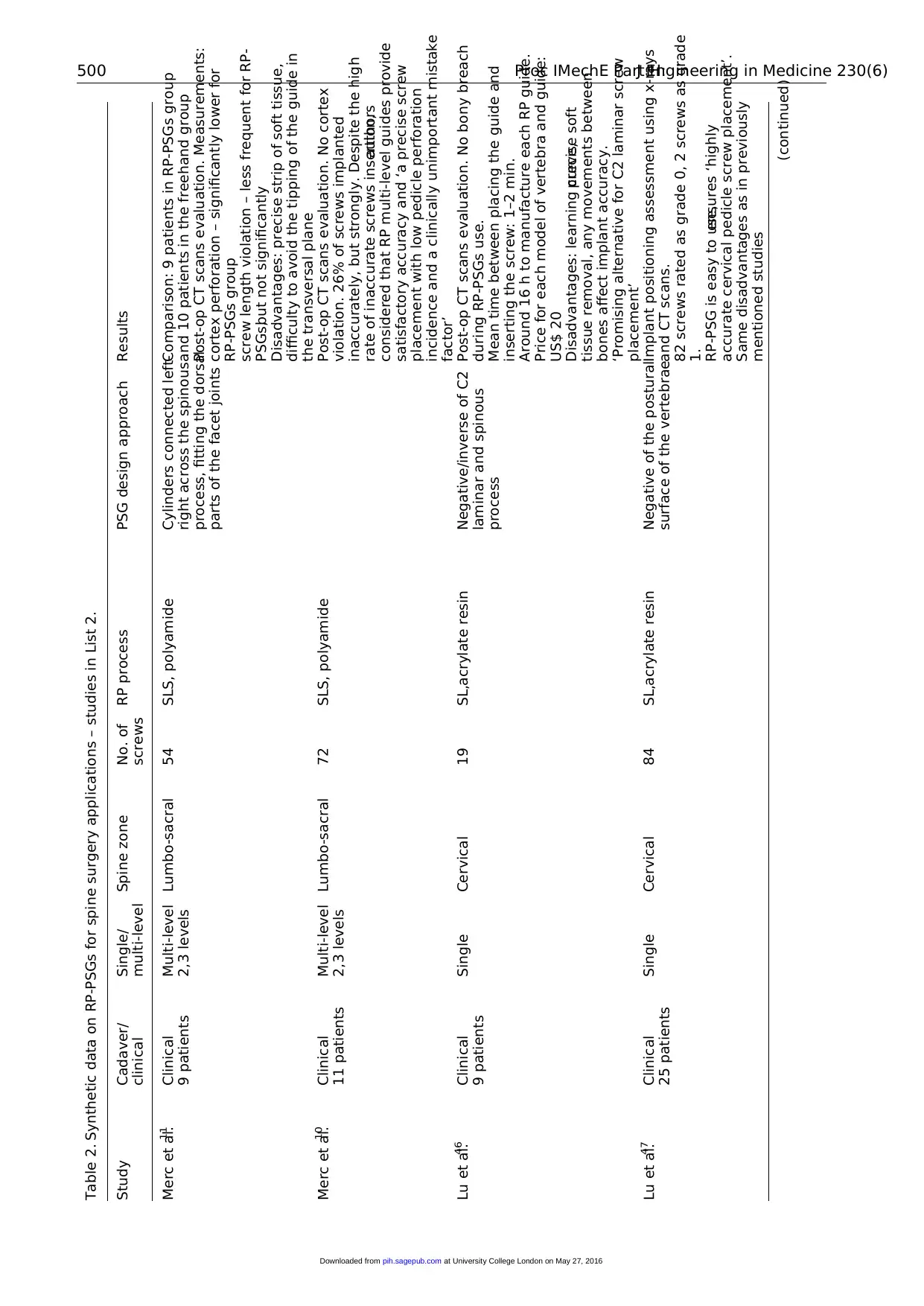

Table 1 presents the distribution of studies on anato-

mical areas, based also on information from ‘List 1’.

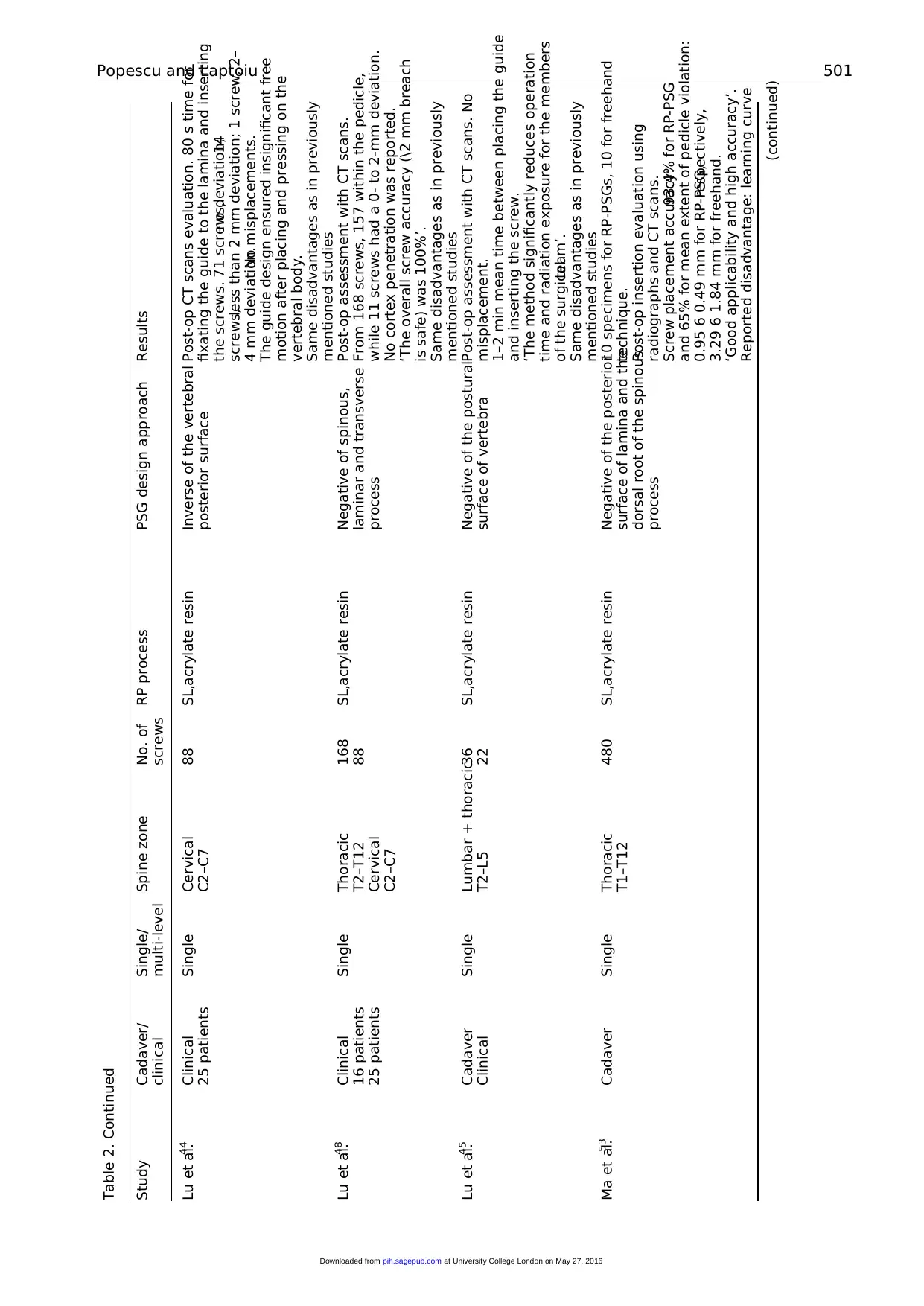

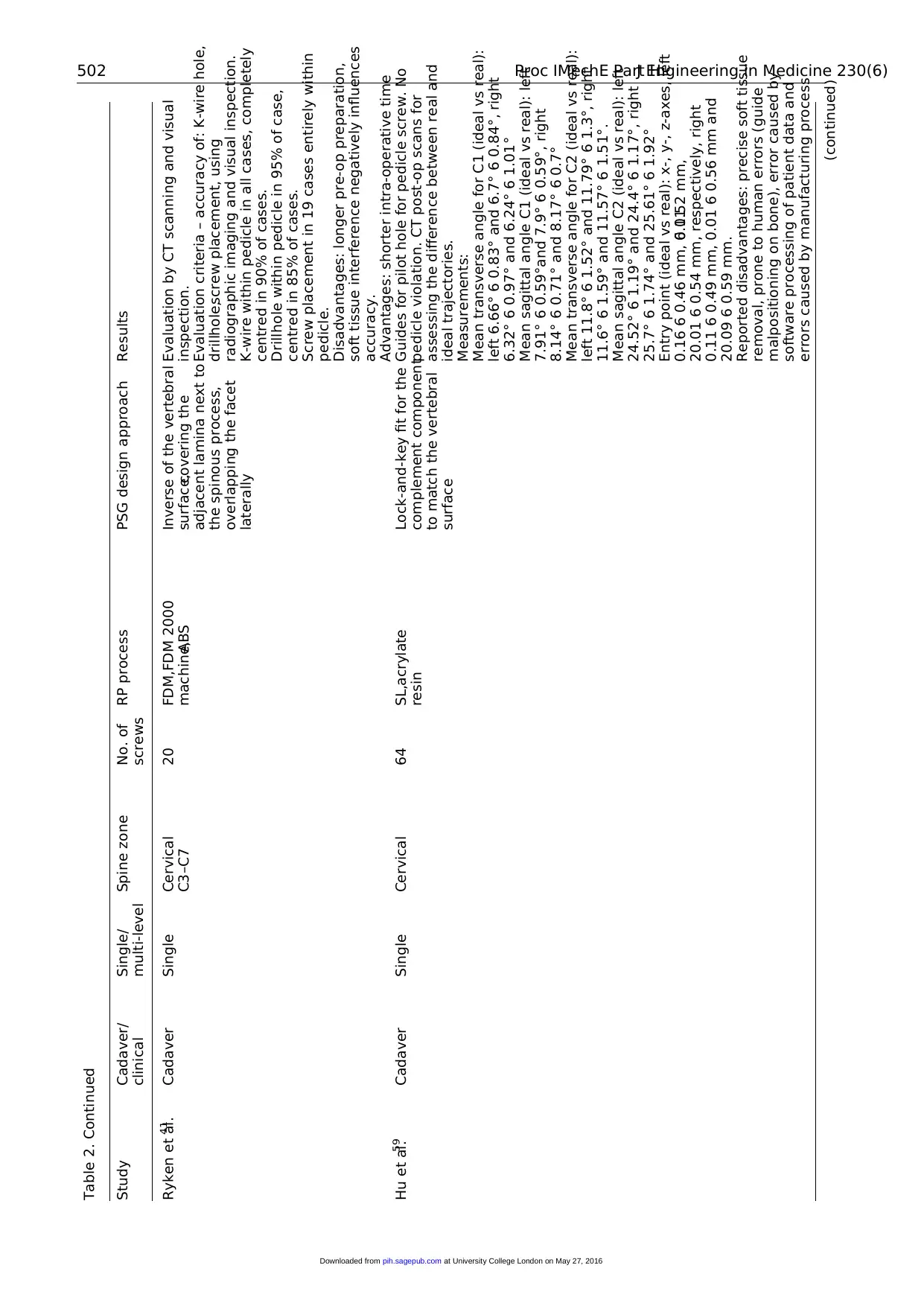

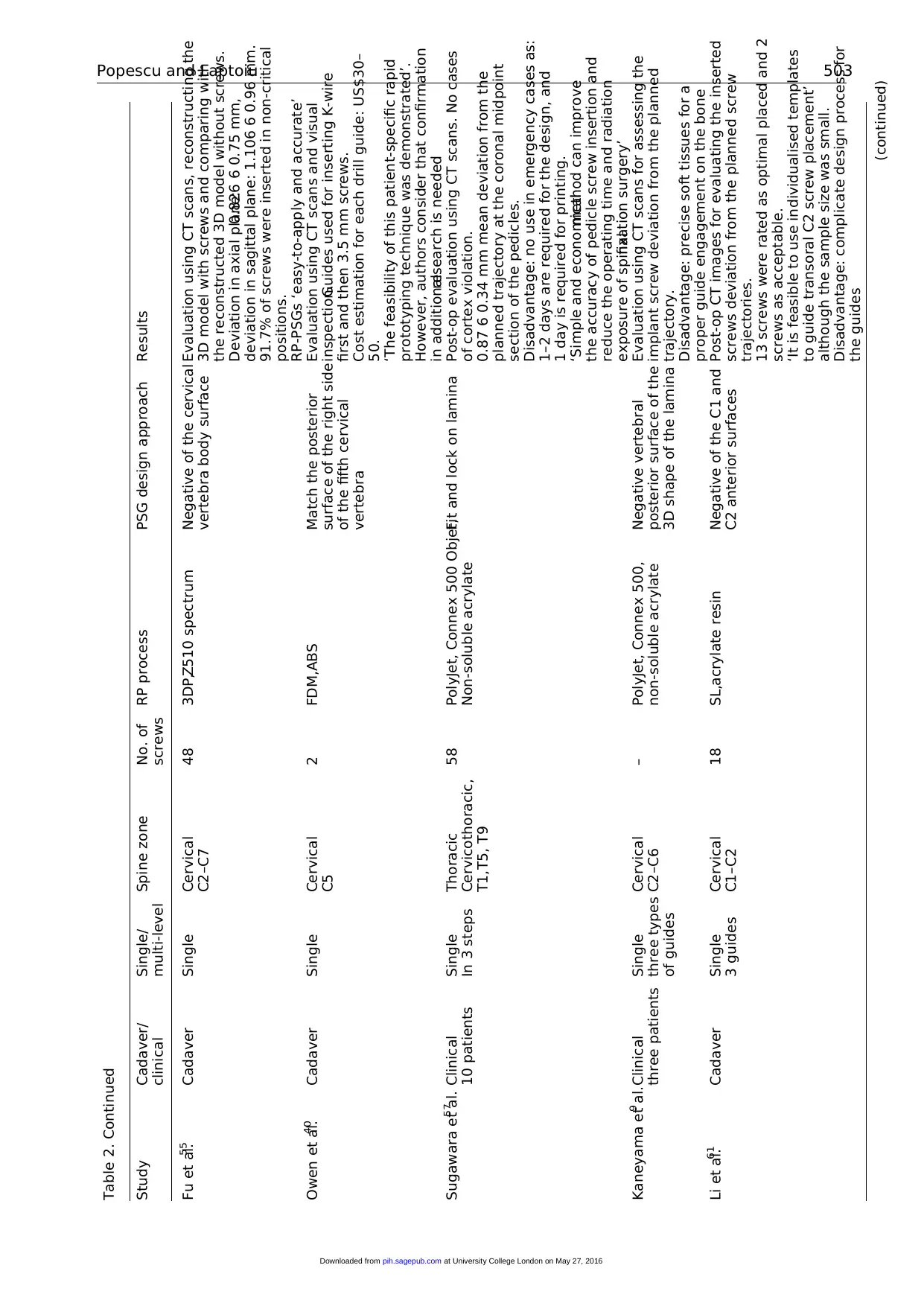

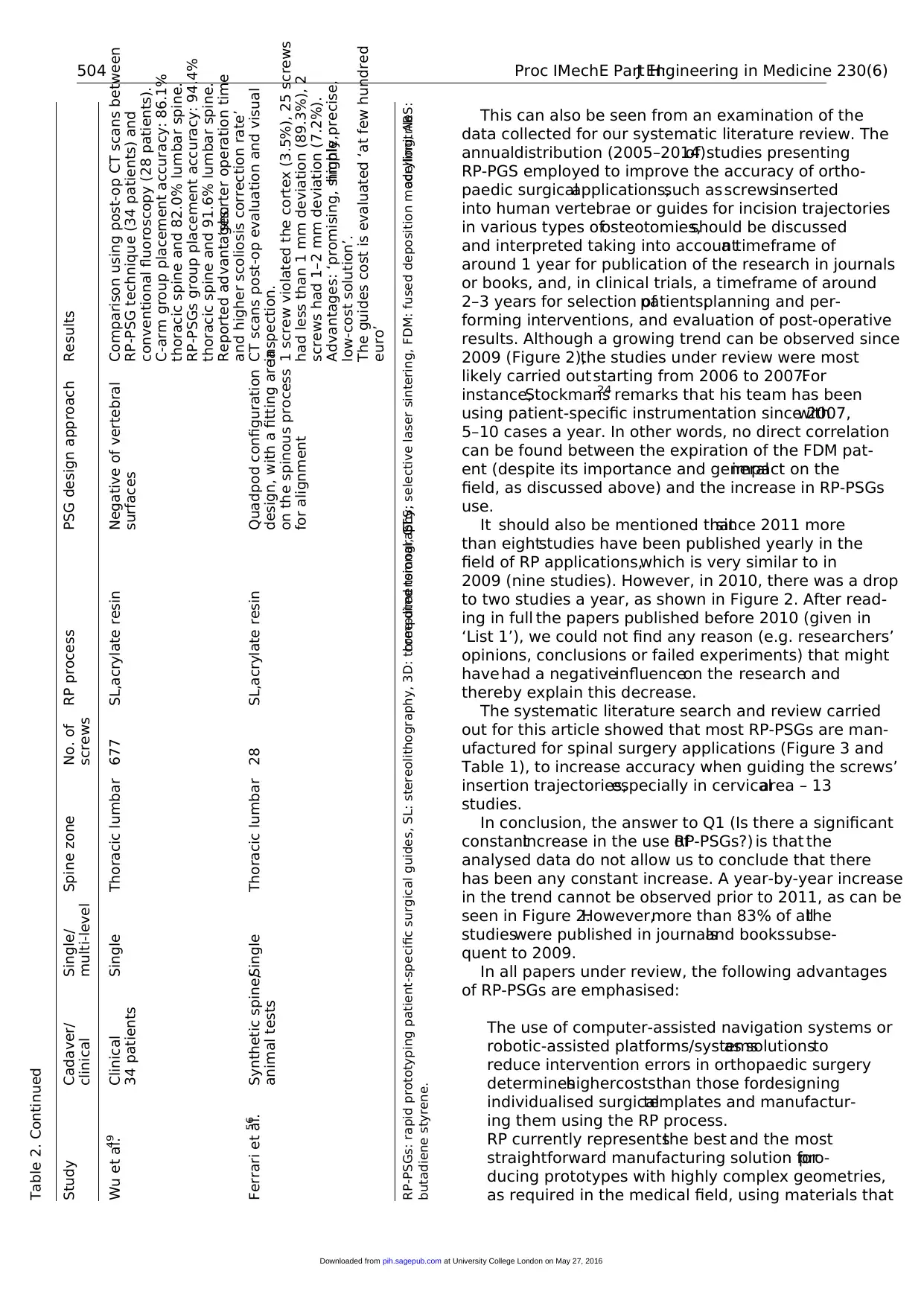

Table 2 summarisesthe data of severalstudies

regarding the use of RP-PSGs for spinal surgery appli-

cations,with the studies used to extractinformation

were those from ‘List 2’.The individualised RP tem-

plates for these applications are employed both for fix-

ing vertebrausing screwsand for guiding other

orthopaedic procedures – osteotomies being the most

complex,because they frequently require multi-planar

corrective incisions of the bone followed by assembly

and fixation. Thus, the RP-PSGs are employed to loca-

lise entry points and to transfer the pre-planned tap-

ping and drilling tool trajectoriesfrom computer

simulation of correction to real surgery.

Figure 2. Number of RP-PSGs studies in orthopaedic surgery.

498 Proc IMechE Part H:J Engineering in Medicine 230(6)

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

TKA surgical guide applications from companies such

as Smith and Nephew, Biomet and Zimmer included in

the survey in order to avoid presentation of potentially

biased information, and also because they are not offer-

ing too many technical details on the design aspects and

manufacturing process.Moreover,Thienpontet al.15

already presented a comprehensive survey (Europe and

worldwide)on patient-specificinstrumentationfor

TKA (including RP guides), based on information from

orthopaedic companies (2011–2012 volumes ofsales).

Therefore, we focused our review only on the cases pre-

sented in the literature as we consider that they can pro-

vide documented technicalinformation on different

aspects ofthe development,use and evaluation pro-

cesses of this type of surgical guides.

Papers with English titles that came up in the search

results,but which werewritten in other languages

(German,Chinese and Japanese) were also eliminated

from our list. We assumed that it was more than likely

that the results laid out in these papers had also been

published in English in various journals.

In the end, 52 studies were retained for further anal-

ysis. When filtering titles and abstracts, we noticed the

very large number of RP applications in manufacturing

PSGs for dental applications, an area better developed

than that of orthopaedic surgery.

In the next stageof filtering,the articleswere

reviewed in full by both authors independently,in

order to establish mutualagreement,especially given

that their separate fields of specialisation (engineering

and medicine)mightdetermine differentperspectives

on and understandings of the same subject. In addition,

a supplementary search was carried out using the refer-

ences found in the 52 articles,thereby generating nine

further papers relating to the subject.

Thus, a total of 61 studies presenting applications of

RP processes in the manufacturing of PSGs for ortho-

paedic surgery,in both clinicalcases and experiments

on cadavers, were selected for ‘List 1’. However, not all

of thesearticlescontained sufficientinformation or

outcomes(i.e. radiologicaldata for PSG usefulness

assessment,information on guide design,information

on computed tomography (CT)scanning protocols,

typesof RP process and materials)to answer our

questions.Furthermore,some of the articles presented

information or preliminary information that was later

repeated, in a more detailed manner, in other papers or

book chapters. For these reasons, 23 papers were elimi-

nated from ‘List 1’, and the remaining 38 articles

(named as ‘List 2’) are discussed separately in section

‘Discussion’.The articles in ‘List 2’were divided into

two broad categories:RP-PSGs for spinal surgery

applications (discussed in section ‘RP-PSGs for spinal

surgery applications’) and RP-PSGs for other general

orthopaedic surgery applications (osteotomies,tumour

resections, etc., discussed in section ‘RP-PSGs for gen-

eral orthopaedic surgery applications’).

In conclusion,the articles in ‘List1’ were used to

answer Q1 and Q2,and,in part,the other questions,

while the articles in ‘List 2’ provided a detailed exami-

nation of specific RP-PSGs design and manufacturing

criteria, diverse methods and approaches, reported effi-

ciency, thereby providing answers to Q3 and Q4.

Results

The articles from ‘List 1’ contained sufficient informa-

tion to allow us to plot the charts presented in Figures 2

and 3. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the number of

RP-PSGs orthopaedic surgery studies per year, provid-

ing an answer to the first question, while Figure 3 pre-

sents the number ofRP-PSGs applications in spinal

surgery.

Table 1 presents the distribution of studies on anato-

mical areas, based also on information from ‘List 1’.

Table 2 summarisesthe data of severalstudies

regarding the use of RP-PSGs for spinal surgery appli-

cations,with the studies used to extractinformation

were those from ‘List 2’.The individualised RP tem-

plates for these applications are employed both for fix-

ing vertebrausing screwsand for guiding other

orthopaedic procedures – osteotomies being the most

complex,because they frequently require multi-planar

corrective incisions of the bone followed by assembly

and fixation. Thus, the RP-PSGs are employed to loca-

lise entry points and to transfer the pre-planned tap-

ping and drilling tool trajectoriesfrom computer

simulation of correction to real surgery.

Figure 2. Number of RP-PSGs studies in orthopaedic surgery.

498 Proc IMechE Part H:J Engineering in Medicine 230(6)

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

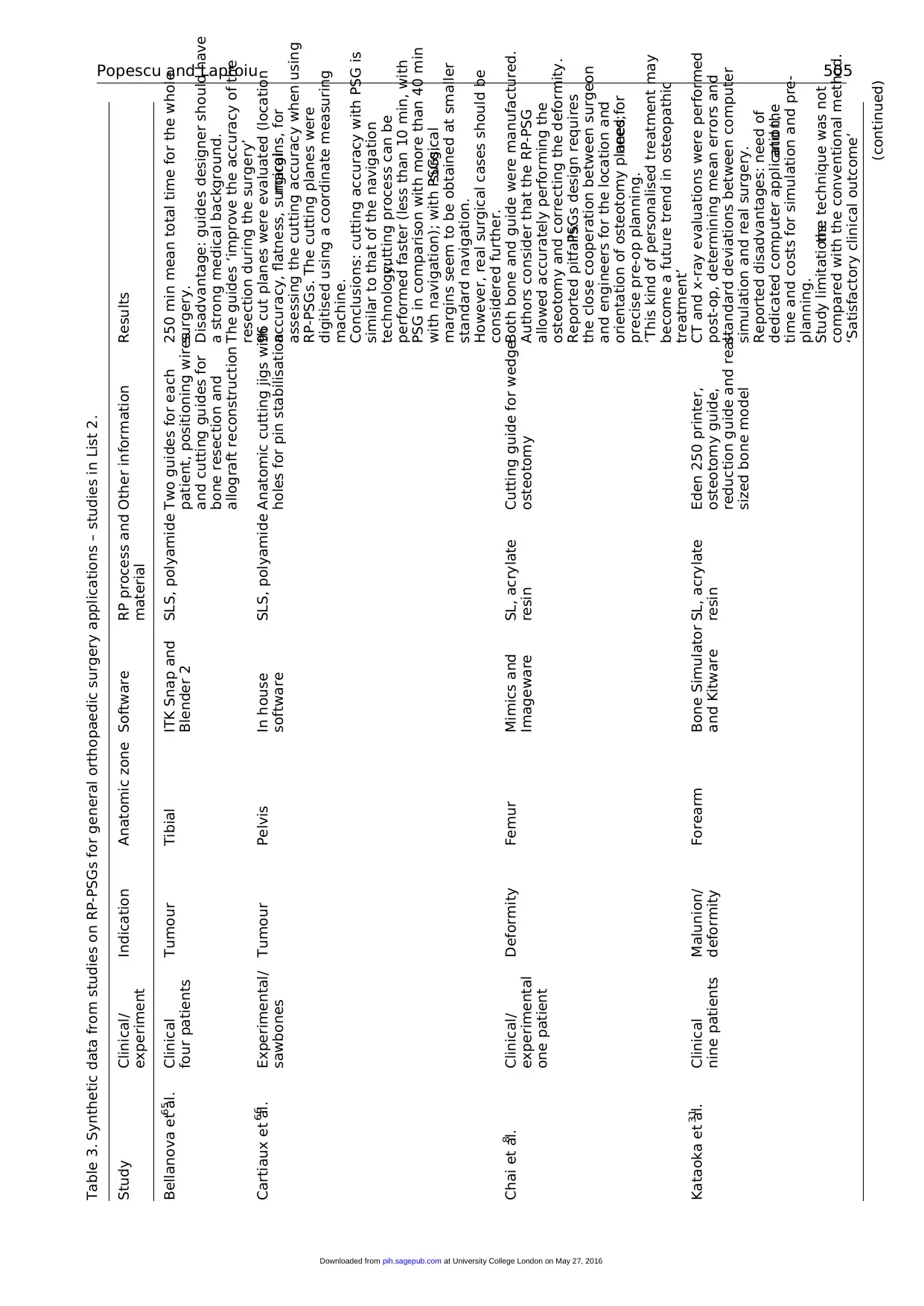

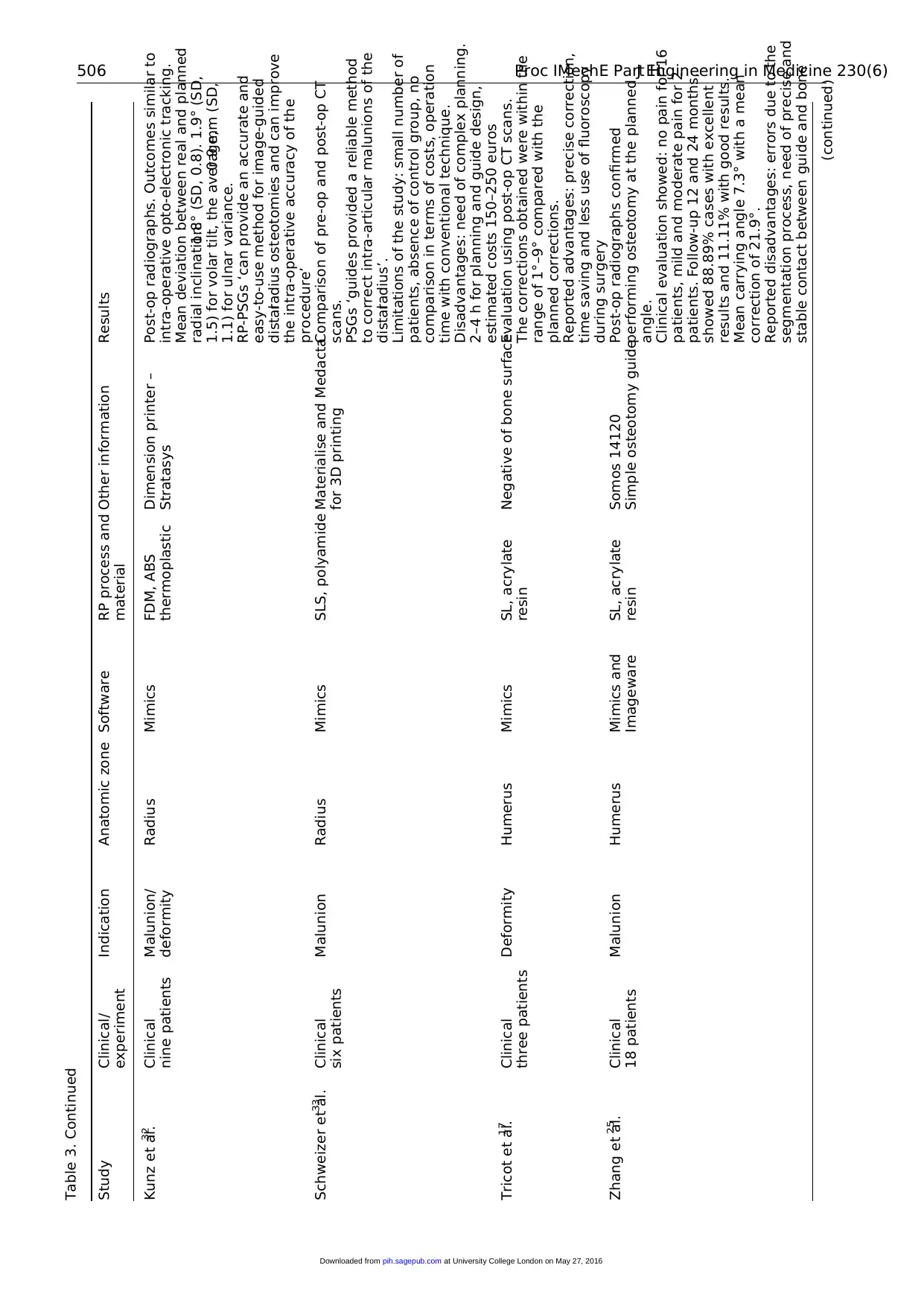

Table 3 summarises data from studies focused on

different applications of RP-PSGs over the extremities

(femur, forearm, tibia, radius, cubitus, etc.).

Tables 2 and 3 also contain columns (called Results)

with information on how RP-PSGs are evaluated. Both

qualitativeopinions and quantitativemethods/mea-

surements are presented by the authors of the reviewed

studies.Therefore,these columns contain diverse data

on the research outcomes,time of intervention when

using PSGs or PSGs’ costs (where available).

Figure 4 indicates the number of clinicalstudies as

opposed to other studies (clinical/cadavers,cadavers,

sawbones)for each main application category under

consideration: spine applications (10 clinical, 1 clinical/

cadavers, 1 synthetic spine/animal tests, 9 on cadavers),

other applications(13 clinical, 1 experimental/saw-

bones,1 clinical/experimentaland 2 experimental).

These data were retrieved from the papers in ‘List 2’.

Corroborating this information with that presented in

Tables 2 and 3, one can observe that for all the applica-

tions,the number of clinicalstudies is higher (23–15)

although for spinal surgery, the number of clinical trials

as opposed to cadaver studies is almost the same.

Figure 5 shows data on the type of RP process used

in each articleunder review,with this information

being extracted from the studies in ‘List 2’. In the case

of spinalsurgery applications,the RP process used in

manufacturing PSGs are as follows: SLS – two clinical

studies by Merc et al.,10,113D printing – one cadaver

study, FDM – two cadavers’ studies and PolyJet – two

clinical studies.The other 14 applicationsuse SL

process.

Discussion

The expiration of the FDM process patent in 2009 led

to a noticeable increase in the number of RP parts man-

ufactured in different fields and for different purposes.

In addition, the cost of the manufacturedparts

decreased,while there was a dramatic increase in the

overallnumber ofmachines sold and the number of

published scientific studies and articles containing gen-

eral information.However,in regard to the medical

field, we considered that the publicity surrounding RP

has a greaterimpactthan the ‘democratisation’of

access to such processes, as the most part of the medica

prototypes are built using SL machines (which continue

to be expensive) by companies that provide services in

the RP field, rather than directly by hospitals.

Table 1. Anatomical regions interested in the retrieved studies – List 1.

Anatomicalregion Number of

studies

Details

Arm/shoulder 2 Debarre et al.,16 Tricot et al.17

Wrist/forearm 20 Mahaisavariya,18 Murase et al.,19 Oka et al.,20,21

Murase et al.,22 Hsieh et al.,23

Stockmans,24Zhang et al.,25Oka et al.,26,27

Miyake et al.,28–30Kataoka et al.,31

Kunz et al.,32 Schweizer et al.,33 Takeyasu et al.34 and Omori et al.35,36

Hand 1 Imai et al.37

Spine 28 Berry et al.,38 D’Urso et al.,39 Owen et al.,40 Ryken et al.,41,42

Zhang et al.,43 Lu

et al.,44–46Zhang et al.,25 Lu et al.,47,48

Wu et al.,49 Takemoto et al.,50 Lu et al.,51

Kawaguchi et al.,52 Ma et al.,53 Hu et al.,54 Fu et al.,55Ferrariet al.,56 Sugawara

et al.,57 Merc et al.,11 Hu et al.,58,59

Merc et al.,10 Tomnic et al.,60Kaneyama et al.9

and Li et al.61

Thorax 1 Yang et al.62

Hip/thigh 6 Presselet al.,63Hung et al.,64 Bellanova et al.,65 Chai et al.,8 Cartiaux et al.66and

Blakeney et al.67

Foot 1 De Wouters et al.68

Tibia 2 Dobbe et al.69,70

Figure 3. Studies per year on RP-PSGs for orthopaedics (spine vs other applications) – List 1.

Popescu and Laptoiu 499

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

different applications of RP-PSGs over the extremities

(femur, forearm, tibia, radius, cubitus, etc.).

Tables 2 and 3 also contain columns (called Results)

with information on how RP-PSGs are evaluated. Both

qualitativeopinions and quantitativemethods/mea-

surements are presented by the authors of the reviewed

studies.Therefore,these columns contain diverse data

on the research outcomes,time of intervention when

using PSGs or PSGs’ costs (where available).

Figure 4 indicates the number of clinicalstudies as

opposed to other studies (clinical/cadavers,cadavers,

sawbones)for each main application category under

consideration: spine applications (10 clinical, 1 clinical/

cadavers, 1 synthetic spine/animal tests, 9 on cadavers),

other applications(13 clinical, 1 experimental/saw-

bones,1 clinical/experimentaland 2 experimental).

These data were retrieved from the papers in ‘List 2’.

Corroborating this information with that presented in

Tables 2 and 3, one can observe that for all the applica-

tions,the number of clinicalstudies is higher (23–15)

although for spinal surgery, the number of clinical trials

as opposed to cadaver studies is almost the same.

Figure 5 shows data on the type of RP process used

in each articleunder review,with this information

being extracted from the studies in ‘List 2’. In the case

of spinalsurgery applications,the RP process used in

manufacturing PSGs are as follows: SLS – two clinical

studies by Merc et al.,10,113D printing – one cadaver

study, FDM – two cadavers’ studies and PolyJet – two

clinical studies.The other 14 applicationsuse SL

process.

Discussion

The expiration of the FDM process patent in 2009 led

to a noticeable increase in the number of RP parts man-

ufactured in different fields and for different purposes.

In addition, the cost of the manufacturedparts

decreased,while there was a dramatic increase in the

overallnumber ofmachines sold and the number of

published scientific studies and articles containing gen-

eral information.However,in regard to the medical

field, we considered that the publicity surrounding RP

has a greaterimpactthan the ‘democratisation’of

access to such processes, as the most part of the medica

prototypes are built using SL machines (which continue

to be expensive) by companies that provide services in

the RP field, rather than directly by hospitals.

Table 1. Anatomical regions interested in the retrieved studies – List 1.

Anatomicalregion Number of

studies

Details

Arm/shoulder 2 Debarre et al.,16 Tricot et al.17

Wrist/forearm 20 Mahaisavariya,18 Murase et al.,19 Oka et al.,20,21

Murase et al.,22 Hsieh et al.,23

Stockmans,24Zhang et al.,25Oka et al.,26,27

Miyake et al.,28–30Kataoka et al.,31

Kunz et al.,32 Schweizer et al.,33 Takeyasu et al.34 and Omori et al.35,36

Hand 1 Imai et al.37

Spine 28 Berry et al.,38 D’Urso et al.,39 Owen et al.,40 Ryken et al.,41,42

Zhang et al.,43 Lu

et al.,44–46Zhang et al.,25 Lu et al.,47,48

Wu et al.,49 Takemoto et al.,50 Lu et al.,51

Kawaguchi et al.,52 Ma et al.,53 Hu et al.,54 Fu et al.,55Ferrariet al.,56 Sugawara

et al.,57 Merc et al.,11 Hu et al.,58,59

Merc et al.,10 Tomnic et al.,60Kaneyama et al.9

and Li et al.61

Thorax 1 Yang et al.62

Hip/thigh 6 Presselet al.,63Hung et al.,64 Bellanova et al.,65 Chai et al.,8 Cartiaux et al.66and

Blakeney et al.67

Foot 1 De Wouters et al.68

Tibia 2 Dobbe et al.69,70

Figure 3. Studies per year on RP-PSGs for orthopaedics (spine vs other applications) – List 1.

Popescu and Laptoiu 499

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Table 2. Synthetic data on RP-PSGs for spine surgery applications – studies in List 2.

Study Cadaver/

clinical

Single/

multi-level

Spine zone No. of

screws

RP process PSG design approach Results

Merc et al.11 Clinical

9 patients

Multi-level

2,3 levels

Lumbo-sacral 54 SLS, polyamide Cylinders connected left-

right across the spinous

process, fitting the dorsal

parts of the facet joints

Comparison: 9 patients in RP-PSGs group

and 10 patients in the freehand group

Post-op CT scans evaluation. Measurements:

cortex perforation – significantly lower for

RP-PSGs group

screw length violation – less frequent for RP-

PSGs,but not significantly

Disadvantages: precise strip of soft tissue,

difficulty to avoid the tipping of the guide in

the transversal plane

Merc et al.10 Clinical

11 patients

Multi-level

2,3 levels

Lumbo-sacral 72 SLS, polyamide Post-op CT scans evaluation. No cortex

violation. 26% of screws implanted

inaccurately, but strongly. Despite the high

rate of inaccurate screws insertion,authors

considered that RP multi-level guides provide

satisfactory accuracy and ‘a precise screw

placement with low pedicle perforation

incidence and a clinically unimportant mistake

factor’

Lu et al.46 Clinical

9 patients

Single Cervical 19 SL,acrylate resin Negative/inverse of C2

laminar and spinous

process

Post-op CT scans evaluation. No bony breach

during RP-PSGs use.

Mean time between placing the guide and

inserting the screw: 1–2 min.

Around 16 h to manufacture each RP guide.

Price for each model of vertebra and guide:

US$ 20

Disadvantages: learning curve,precise soft

tissue removal, any movements between

bones affect implant accuracy.

‘Promising alternative for C2 laminar screw

placement’

Lu et al.47 Clinical

25 patients

Single Cervical 84 SL,acrylate resin Negative of the postural

surface of the vertebrae

Implant positioning assessment using x-rays

and CT scans.

82 screws rated as grade 0, 2 screws as grade

1.

RP-PSG is easy to use,ensures ‘highly

accurate cervical pedicle screw placement’.

Same disadvantages as in previously

mentioned studies

(continued)500 Proc IMechE Part H:J Engineering in Medicine 230(6)

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Study Cadaver/

clinical

Single/

multi-level

Spine zone No. of

screws

RP process PSG design approach Results

Merc et al.11 Clinical

9 patients

Multi-level

2,3 levels

Lumbo-sacral 54 SLS, polyamide Cylinders connected left-

right across the spinous

process, fitting the dorsal

parts of the facet joints

Comparison: 9 patients in RP-PSGs group

and 10 patients in the freehand group

Post-op CT scans evaluation. Measurements:

cortex perforation – significantly lower for

RP-PSGs group

screw length violation – less frequent for RP-

PSGs,but not significantly

Disadvantages: precise strip of soft tissue,

difficulty to avoid the tipping of the guide in

the transversal plane

Merc et al.10 Clinical

11 patients

Multi-level

2,3 levels

Lumbo-sacral 72 SLS, polyamide Post-op CT scans evaluation. No cortex

violation. 26% of screws implanted

inaccurately, but strongly. Despite the high

rate of inaccurate screws insertion,authors

considered that RP multi-level guides provide

satisfactory accuracy and ‘a precise screw

placement with low pedicle perforation

incidence and a clinically unimportant mistake

factor’

Lu et al.46 Clinical

9 patients

Single Cervical 19 SL,acrylate resin Negative/inverse of C2

laminar and spinous

process

Post-op CT scans evaluation. No bony breach

during RP-PSGs use.

Mean time between placing the guide and

inserting the screw: 1–2 min.

Around 16 h to manufacture each RP guide.

Price for each model of vertebra and guide:

US$ 20

Disadvantages: learning curve,precise soft

tissue removal, any movements between

bones affect implant accuracy.

‘Promising alternative for C2 laminar screw

placement’

Lu et al.47 Clinical

25 patients

Single Cervical 84 SL,acrylate resin Negative of the postural

surface of the vertebrae

Implant positioning assessment using x-rays

and CT scans.

82 screws rated as grade 0, 2 screws as grade

1.

RP-PSG is easy to use,ensures ‘highly

accurate cervical pedicle screw placement’.

Same disadvantages as in previously

mentioned studies

(continued)500 Proc IMechE Part H:J Engineering in Medicine 230(6)

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Table 2. Continued

Study Cadaver/

clinical

Single/

multi-level

Spine zone No. of

screws

RP process PSG design approach Results

Lu et al.44 Clinical

25 patients

Single Cervical

C2–C7

88 SL,acrylate resin Inverse of the vertebral

posterior surface

Post-op CT scans evaluation. 80 s time for

fixating the guide to the lamina and inserting

the screws. 71 screws,no deviation;14

screws,less than 2 mm deviation; 1 screw, 2–

4 mm deviation.No misplacements.

The guide design ensured insignificant free

motion after placing and pressing on the

vertebral body.

Same disadvantages as in previously

mentioned studies

Lu et al.48 Clinical

16 patients

25 patients

Single Thoracic

T2–T12

Cervical

C2–C7

168

88

SL,acrylate resin Negative of spinous,

laminar and transverse

process

Post-op assessment with CT scans.

From 168 screws, 157 within the pedicle,

while 11 screws had a 0- to 2-mm deviation.

No cortex penetration was reported.

‘The overall screw accuracy (\2 mm breach

is safe) was 100%’.

Same disadvantages as in previously

mentioned studies

Lu et al.45 Cadaver

Clinical

Single Lumbar + thoracic

T2–L5

36

22

SL,acrylate resin Negative of the postural

surface of vertebra

Post-op assessment with CT scans. No

misplacement.

1–2 min mean time between placing the guide

and inserting the screw.

‘The method significantly reduces operation

time and radiation exposure for the members

of the surgicalteam’.

Same disadvantages as in previously

mentioned studies

Ma et al.53 Cadaver Single Thoracic

T1–T12

480 SL,acrylate resin Negative of the posterior

surface of lamina and the

dorsal root of the spinous

process

10 specimens for RP-PSGs, 10 for freehand

technique.

Post-op insertion evaluation using

radiographs and CT scans.

Screw placement accuracy:93.4% for RP-PSG

and 65% for mean extent of pedicle violation:

0.95 6 0.49 mm for RP-PSG,respectively,

3.29 6 1.84 mm for freehand.

‘Good applicability and high accuracy’.

Reported disadvantage: learning curve

(continued)Popescu and Laptoiu 501

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Study Cadaver/

clinical

Single/

multi-level

Spine zone No. of

screws

RP process PSG design approach Results

Lu et al.44 Clinical

25 patients

Single Cervical

C2–C7

88 SL,acrylate resin Inverse of the vertebral

posterior surface

Post-op CT scans evaluation. 80 s time for

fixating the guide to the lamina and inserting

the screws. 71 screws,no deviation;14

screws,less than 2 mm deviation; 1 screw, 2–

4 mm deviation.No misplacements.

The guide design ensured insignificant free

motion after placing and pressing on the

vertebral body.

Same disadvantages as in previously

mentioned studies

Lu et al.48 Clinical

16 patients

25 patients

Single Thoracic

T2–T12

Cervical

C2–C7

168

88

SL,acrylate resin Negative of spinous,

laminar and transverse

process

Post-op assessment with CT scans.

From 168 screws, 157 within the pedicle,

while 11 screws had a 0- to 2-mm deviation.

No cortex penetration was reported.

‘The overall screw accuracy (\2 mm breach

is safe) was 100%’.

Same disadvantages as in previously

mentioned studies

Lu et al.45 Cadaver

Clinical

Single Lumbar + thoracic

T2–L5

36

22

SL,acrylate resin Negative of the postural

surface of vertebra

Post-op assessment with CT scans. No

misplacement.

1–2 min mean time between placing the guide

and inserting the screw.

‘The method significantly reduces operation

time and radiation exposure for the members

of the surgicalteam’.

Same disadvantages as in previously

mentioned studies

Ma et al.53 Cadaver Single Thoracic

T1–T12

480 SL,acrylate resin Negative of the posterior

surface of lamina and the

dorsal root of the spinous

process

10 specimens for RP-PSGs, 10 for freehand

technique.

Post-op insertion evaluation using

radiographs and CT scans.

Screw placement accuracy:93.4% for RP-PSG

and 65% for mean extent of pedicle violation:

0.95 6 0.49 mm for RP-PSG,respectively,

3.29 6 1.84 mm for freehand.

‘Good applicability and high accuracy’.

Reported disadvantage: learning curve

(continued)Popescu and Laptoiu 501

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Table 2. Continued

Study Cadaver/

clinical

Single/

multi-level

Spine zone No. of

screws

RP process PSG design approach Results

Ryken et al.41 Cadaver Single Cervical

C3–C7

20 FDM,FDM 2000

machine,ABS

Inverse of the vertebral

surface,covering the

adjacent lamina next to

the spinous process,

overlapping the facet

laterally

Evaluation by CT scanning and visual

inspection.

Evaluation criteria – accuracy of: K-wire hole,

drillhole,screw placement, using

radiographic imaging and visual inspection.

K-wire within pedicle in all cases, completely

centred in 90% of cases.

Drillhole within pedicle in 95% of case,

centred in 85% of cases.

Screw placement in 19 cases entirely within

pedicle.

Disadvantages: longer pre-op preparation,

soft tissue interference negatively influences

accuracy.

Advantages: shorter intra-operative time

Hu et al.59 Cadaver Single Cervical 64 SL,acrylate

resin

Lock-and-key fit for the

complement component

to match the vertebral

surface

Guides for pilot hole for pedicle screw. No

pedicle violation. CT post-op scans for

assessing the difference between real and

ideal trajectories.

Measurements:

Mean transverse angle for C1 (ideal vs real):

left 6.66° 6 0.83° and 6.7° 6 0.84°, right

6.32° 6 0.97° and 6.24° 6 1.01°

Mean sagittal angle C1 (ideal vs real): left

7.91° 6 0.59°and 7.9° 6 0.59°, right

8.14° 6 0.71° and 8.17° 6 0.7°

Mean transverse angle for C2 (ideal vs real):

left 11.8° 6 1.52° and 11.79° 6 1.3°, right

11.6° 6 1.59° and 11.57° 6 1.51°.

Mean sagittal angle C2 (ideal vs real): left

24.52° 6 1.19° and 24.4° 6 1.17°, right

25.7° 6 1.74° and 25.61° 6 1.92°

Entry point (ideal vs real): x-, y-, z-axes, left

0.16 6 0.46 mm, 0.116 0.52 mm,

20.01 6 0.54 mm, respectively, right

0.11 6 0.49 mm, 0.01 6 0.56 mm and

20.09 6 0.59 mm.

Reported disadvantages: precise soft tissue

removal, prone to human errors (guide

malpositioning on bone), error caused by

software processing of patient data and

errors caused by manufacturing process

(continued)502 Proc IMechE Part H:J Engineering in Medicine 230(6)

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Study Cadaver/

clinical

Single/

multi-level

Spine zone No. of

screws

RP process PSG design approach Results

Ryken et al.41 Cadaver Single Cervical

C3–C7

20 FDM,FDM 2000

machine,ABS

Inverse of the vertebral

surface,covering the

adjacent lamina next to

the spinous process,

overlapping the facet

laterally

Evaluation by CT scanning and visual

inspection.

Evaluation criteria – accuracy of: K-wire hole,

drillhole,screw placement, using

radiographic imaging and visual inspection.

K-wire within pedicle in all cases, completely

centred in 90% of cases.

Drillhole within pedicle in 95% of case,

centred in 85% of cases.

Screw placement in 19 cases entirely within

pedicle.

Disadvantages: longer pre-op preparation,

soft tissue interference negatively influences

accuracy.

Advantages: shorter intra-operative time

Hu et al.59 Cadaver Single Cervical 64 SL,acrylate

resin

Lock-and-key fit for the

complement component

to match the vertebral

surface

Guides for pilot hole for pedicle screw. No

pedicle violation. CT post-op scans for

assessing the difference between real and

ideal trajectories.

Measurements:

Mean transverse angle for C1 (ideal vs real):

left 6.66° 6 0.83° and 6.7° 6 0.84°, right

6.32° 6 0.97° and 6.24° 6 1.01°

Mean sagittal angle C1 (ideal vs real): left

7.91° 6 0.59°and 7.9° 6 0.59°, right

8.14° 6 0.71° and 8.17° 6 0.7°

Mean transverse angle for C2 (ideal vs real):

left 11.8° 6 1.52° and 11.79° 6 1.3°, right

11.6° 6 1.59° and 11.57° 6 1.51°.

Mean sagittal angle C2 (ideal vs real): left

24.52° 6 1.19° and 24.4° 6 1.17°, right

25.7° 6 1.74° and 25.61° 6 1.92°

Entry point (ideal vs real): x-, y-, z-axes, left

0.16 6 0.46 mm, 0.116 0.52 mm,

20.01 6 0.54 mm, respectively, right

0.11 6 0.49 mm, 0.01 6 0.56 mm and

20.09 6 0.59 mm.

Reported disadvantages: precise soft tissue

removal, prone to human errors (guide

malpositioning on bone), error caused by

software processing of patient data and

errors caused by manufacturing process

(continued)502 Proc IMechE Part H:J Engineering in Medicine 230(6)

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Table 2. Continued

Study Cadaver/

clinical

Single/

multi-level

Spine zone No. of

screws

RP process PSG design approach Results

Fu et al.55 Cadaver Single Cervical

C2–C7

48 3DP,Z510 spectrum Negative of the cervical

vertebra body surface

Evaluation using CT scans, reconstructing the

3D model with screws and comparing with

the reconstructed 3D model without screws.

Deviation in axial plane:0.826 6 0.75 mm,

deviation in sagittal plane: 1.106 6 0.96 mm.

91.7% of screws were inserted in non-critical

positions.

RP-PSGs ‘easy-to-apply and accurate’

Owen et al.40 Cadaver Single Cervical

C5

2 FDM,ABS Match the posterior

surface of the right side

of the fifth cervical

vertebra

Evaluation using CT scans and visual

inspection.Guides used for inserting K-wire

first and then 3.5 mm screws.

Cost estimation for each drill guide: US$30–

50.

‘The feasibility of this patient-specific rapid

prototyping technique was demonstrated’.

However, authors consider that confirmation

in additionalresearch is needed

Sugawara et al.57 Clinical

10 patients

Single

In 3 steps

Thoracic

Cervicothoracic,

T1,T5, T9

58 PolyJet, Connex 500 Objet,

Non-soluble acrylate

Fit and lock on lamina Post-op evaluation using CT scans. No cases

of cortex violation.

0.87 6 0.34 mm mean deviation from the

planned trajectory at the coronal midpoint

section of the pedicles.

Disadvantage: no use in emergency cases as:

1–2 days are required for the design, and

1 day is required for printing.

‘Simple and economicalmethod can improve

the accuracy of pedicle screw insertion and

reduce the operating time and radiation

exposure of spinalfixation surgery’

Kaneyama et al.9 Clinical

three patients

Single

three types

of guides

Cervical

C2–C6

– PolyJet, Connex 500,

non-soluble acrylate

Negative vertebral

posterior surface of the

3D shape of the lamina

Evaluation using CT scans for assessing the

implant screw deviation from the planned

trajectory.

Disadvantage: precise soft tissues for a

proper guide engagement on the bone

Li et al.61 Cadaver Single

3 guides

Cervical

C1–C2

18 SL,acrylate resin Negative of the C1 and

C2 anterior surfaces

Post-op CT images for evaluating the inserted

screws deviation from the planned screw

trajectories.

13 screws were rated as optimal placed and 2

screws as acceptable.

‘It is feasible to use individualised templates

to guide transoral C2 screw placement’

although the sample size was small.

Disadvantage: complicate design process for

the guides

(continued)Popescu and Laptoiu 503

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Study Cadaver/

clinical

Single/

multi-level

Spine zone No. of

screws

RP process PSG design approach Results

Fu et al.55 Cadaver Single Cervical

C2–C7

48 3DP,Z510 spectrum Negative of the cervical

vertebra body surface

Evaluation using CT scans, reconstructing the

3D model with screws and comparing with

the reconstructed 3D model without screws.

Deviation in axial plane:0.826 6 0.75 mm,

deviation in sagittal plane: 1.106 6 0.96 mm.

91.7% of screws were inserted in non-critical

positions.

RP-PSGs ‘easy-to-apply and accurate’

Owen et al.40 Cadaver Single Cervical

C5

2 FDM,ABS Match the posterior

surface of the right side

of the fifth cervical

vertebra

Evaluation using CT scans and visual

inspection.Guides used for inserting K-wire

first and then 3.5 mm screws.

Cost estimation for each drill guide: US$30–

50.

‘The feasibility of this patient-specific rapid

prototyping technique was demonstrated’.

However, authors consider that confirmation

in additionalresearch is needed

Sugawara et al.57 Clinical

10 patients

Single

In 3 steps

Thoracic

Cervicothoracic,

T1,T5, T9

58 PolyJet, Connex 500 Objet,

Non-soluble acrylate

Fit and lock on lamina Post-op evaluation using CT scans. No cases

of cortex violation.

0.87 6 0.34 mm mean deviation from the

planned trajectory at the coronal midpoint

section of the pedicles.

Disadvantage: no use in emergency cases as:

1–2 days are required for the design, and

1 day is required for printing.

‘Simple and economicalmethod can improve

the accuracy of pedicle screw insertion and

reduce the operating time and radiation

exposure of spinalfixation surgery’

Kaneyama et al.9 Clinical

three patients

Single

three types

of guides

Cervical

C2–C6

– PolyJet, Connex 500,

non-soluble acrylate

Negative vertebral

posterior surface of the

3D shape of the lamina

Evaluation using CT scans for assessing the

implant screw deviation from the planned

trajectory.

Disadvantage: precise soft tissues for a

proper guide engagement on the bone

Li et al.61 Cadaver Single

3 guides

Cervical

C1–C2

18 SL,acrylate resin Negative of the C1 and

C2 anterior surfaces

Post-op CT images for evaluating the inserted

screws deviation from the planned screw

trajectories.

13 screws were rated as optimal placed and 2

screws as acceptable.

‘It is feasible to use individualised templates

to guide transoral C2 screw placement’

although the sample size was small.

Disadvantage: complicate design process for

the guides

(continued)Popescu and Laptoiu 503

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

This can also be seen from an examination of the

data collected for our systematic literature review. The

annualdistribution (2005–2014)of studies presenting

RP-PGS employed to improve the accuracy of ortho-

paedic surgicalapplications,such as screwsinserted

into human vertebrae or guides for incision trajectories

in various types ofosteotomies,should be discussed

and interpreted taking into accounta timeframe of

around 1 year for publication of the research in journals

or books, and, in clinical trials, a timeframe of around

2–3 years for selection ofpatients,planning and per-

forming interventions, and evaluation of post-operative

results. Although a growing trend can be observed since

2009 (Figure 2),the studies under review were most

likely carried outstarting from 2006 to 2007.For

instance,Stockmans24 remarks that his team has been

using patient-specific instrumentation since 2007,with

5–10 cases a year. In other words, no direct correlation

can be found between the expiration of the FDM pat-

ent (despite its importance and generalimpact on the

field, as discussed above) and the increase in RP-PSGs

use.

It should also be mentioned thatsince 2011 more

than eightstudies have been published yearly in the

field of RP applications,which is very similar to in

2009 (nine studies). However, in 2010, there was a drop

to two studies a year, as shown in Figure 2. After read-

ing in full the papers published before 2010 (given in

‘List 1’), we could not find any reason (e.g. researchers’

opinions, conclusions or failed experiments) that might

have had a negativeinfluenceon the research and

thereby explain this decrease.

The systematic literature search and review carried

out for this article showed that most RP-PSGs are man-

ufactured for spinal surgery applications (Figure 3 and

Table 1), to increase accuracy when guiding the screws’

insertion trajectories,especially in cervicalarea – 13

studies.

In conclusion, the answer to Q1 (Is there a significant

constantincrease in the use ofRP-PSGs?) is that the

analysed data do not allow us to conclude that there

has been any constant increase. A year-by-year increase

in the trend cannot be observed prior to 2011, as can be

seen in Figure 2.However,more than 83% of allthe

studieswere published in journalsand bookssubse-

quent to 2009.

In all papers under review, the following advantages

of RP-PSGs are emphasised:

The use of computer-assisted navigation systems or

robotic-assisted platforms/systemsas solutionsto

reduce intervention errors in orthopaedic surgery

determineshighercoststhan those fordesigning

individualised surgicaltemplates and manufactur-

ing them using the RP process.

RP currently representsthe best and the most

straightforward manufacturing solution forpro-

ducing prototypes with highly complex geometries,

as required in the medical field, using materials that

Table 2. Continued

Study Cadaver/

clinical

Single/

multi-level

Spine zone No. of

screws

RP process PSG design approach Results

Wu et al.49 Clinical

34 patients

Single Thoracic lumbar 677 SL,acrylate resin Negative of vertebral

surfaces

Comparison using post-op CT scans between

RP-PSG technique (34 patients) and

conventional fluoroscopy (28 patients).

C-arm group placement accuracy: 86.1%

thoracic spine and 82.0% lumbar spine.

RP-PSGs group placement accuracy: 94.4%

thoracic spine and 91.6% lumbar spine.

Reported advantages:‘shorter operation time

and higher scoliosis correction rate’

Ferrari et al.56 Synthetic spine/

animal tests

Single Thoracic lumbar 28 SL,acrylate resin Quadpod configuration

design, with a fitting area

on the spinous process

for alignment

CT scans post-op evaluation and visual

inspection.

1 screw violated the cortex (3.5%), 25 screws

had less than 1 mm deviation (89.3%), 2

screws had 1–2 mm deviation (7.2%).

Advantages: ‘promising, simple,highly precise,

low-cost solution’.

The guides cost is evaluated ‘at few hundred

euro’

RP-PSGs: rapid prototyping patient-specific surgical guides, SL: stereolithography, 3D: three-dimensional, CT:computed tomography,SLS: selective laser sintering, FDM: fused deposition modelling, ABS:acrylonitrile

butadiene styrene.

504 Proc IMechE Part H:J Engineering in Medicine 230(6)

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from

data collected for our systematic literature review. The

annualdistribution (2005–2014)of studies presenting

RP-PGS employed to improve the accuracy of ortho-

paedic surgicalapplications,such as screwsinserted

into human vertebrae or guides for incision trajectories

in various types ofosteotomies,should be discussed

and interpreted taking into accounta timeframe of

around 1 year for publication of the research in journals

or books, and, in clinical trials, a timeframe of around

2–3 years for selection ofpatients,planning and per-

forming interventions, and evaluation of post-operative

results. Although a growing trend can be observed since

2009 (Figure 2),the studies under review were most

likely carried outstarting from 2006 to 2007.For

instance,Stockmans24 remarks that his team has been

using patient-specific instrumentation since 2007,with

5–10 cases a year. In other words, no direct correlation

can be found between the expiration of the FDM pat-

ent (despite its importance and generalimpact on the

field, as discussed above) and the increase in RP-PSGs

use.

It should also be mentioned thatsince 2011 more

than eightstudies have been published yearly in the

field of RP applications,which is very similar to in

2009 (nine studies). However, in 2010, there was a drop

to two studies a year, as shown in Figure 2. After read-

ing in full the papers published before 2010 (given in

‘List 1’), we could not find any reason (e.g. researchers’

opinions, conclusions or failed experiments) that might

have had a negativeinfluenceon the research and

thereby explain this decrease.

The systematic literature search and review carried

out for this article showed that most RP-PSGs are man-

ufactured for spinal surgery applications (Figure 3 and

Table 1), to increase accuracy when guiding the screws’

insertion trajectories,especially in cervicalarea – 13

studies.

In conclusion, the answer to Q1 (Is there a significant

constantincrease in the use ofRP-PSGs?) is that the

analysed data do not allow us to conclude that there

has been any constant increase. A year-by-year increase

in the trend cannot be observed prior to 2011, as can be

seen in Figure 2.However,more than 83% of allthe

studieswere published in journalsand bookssubse-

quent to 2009.

In all papers under review, the following advantages

of RP-PSGs are emphasised:

The use of computer-assisted navigation systems or

robotic-assisted platforms/systemsas solutionsto

reduce intervention errors in orthopaedic surgery

determineshighercoststhan those fordesigning

individualised surgicaltemplates and manufactur-

ing them using the RP process.

RP currently representsthe best and the most

straightforward manufacturing solution forpro-

ducing prototypes with highly complex geometries,

as required in the medical field, using materials that

Table 2. Continued

Study Cadaver/

clinical

Single/

multi-level

Spine zone No. of

screws

RP process PSG design approach Results

Wu et al.49 Clinical

34 patients

Single Thoracic lumbar 677 SL,acrylate resin Negative of vertebral

surfaces

Comparison using post-op CT scans between

RP-PSG technique (34 patients) and

conventional fluoroscopy (28 patients).

C-arm group placement accuracy: 86.1%

thoracic spine and 82.0% lumbar spine.

RP-PSGs group placement accuracy: 94.4%

thoracic spine and 91.6% lumbar spine.

Reported advantages:‘shorter operation time

and higher scoliosis correction rate’

Ferrari et al.56 Synthetic spine/

animal tests

Single Thoracic lumbar 28 SL,acrylate resin Quadpod configuration

design, with a fitting area

on the spinous process

for alignment

CT scans post-op evaluation and visual

inspection.

1 screw violated the cortex (3.5%), 25 screws

had less than 1 mm deviation (89.3%), 2

screws had 1–2 mm deviation (7.2%).

Advantages: ‘promising, simple,highly precise,

low-cost solution’.

The guides cost is evaluated ‘at few hundred

euro’

RP-PSGs: rapid prototyping patient-specific surgical guides, SL: stereolithography, 3D: three-dimensional, CT:computed tomography,SLS: selective laser sintering, FDM: fused deposition modelling, ABS:acrylonitrile

butadiene styrene.

504 Proc IMechE Part H:J Engineering in Medicine 230(6)

at University College London on May 27, 2016pih.sagepub.comDownloaded from