Prevalence of PIU and Associated Factors in Malaysian Universities

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/09

|21

|14314

|14

Report

AI Summary

This report, based on a 2015 cross-sectional study of 1023 undergraduate students at a Malaysian public university, investigates the prevalence and determinants of Pathological Internet Use (PIU). The study, utilizing the Young’s Diagnostic Questionnaire, found a PIU prevalence of 28.9%. Significant factors associated with PIU included recreational internet use of three or more hours, pornography use, gambling problems, drug use in the past year, and moderate/severe depression. The report highlights the need for university authorities to develop interventions, such as screening, awareness campaigns, and promoting healthy lifestyles, to address the adverse outcomes of PIU. The study emphasizes the importance of understanding the impact of internet usage patterns and psychosocial factors on student well-being. The research also provides a literature review covering existing research on PIU and its associated factors, including socio-demographic variables, internet use patterns, psychosocial factors, and comorbid symptoms.

Wen Ting Tong, Md. Ashraful Islam, Wah Yun Low, Wan Yuen Choo, and Adina Abdullah

63

Prevalence and Determinants of Pathological Internet Use among

Undergraduate Students in a Public University in Malaysia

Wen Ting Tong1, Md. Ashraful Islam2, Wah Yun Low3, Wan Yuen Choo4,

and Adina Abdullah5

Pathological Internet Use (PIU) affects one’s physical and mental health, and university

students are at risk as they are more likely to develop PIU. This study determines the

prevalence of PIU and its associated factors among students in a public university in

Malaysia. This cross-sectional study was conducted among 1023 undergraduate students in

2015. The questionnaire comprised of items from the Young’s Diagnostic Questionnaire to

assess PIU and items related to socio-demography, psychosocial, lifestyle and co-morbidities.

Anonymous paper-based data collection method was adopted. Mean age of the respondents

was 20.73 ± 1.49 years old. The prevalence of pathological Internet user was 28.9% mostly

Chinese (31%), 22 years old and above (31.0%), in Year 1 (31.5%), and those who perceived

themselves to be from family from higher socio-economic status (32.5%). The factors found

statistically significant (p<0.05) with PIU were Internet use for three or more hours for

recreational purpose (OR: 3.89; 95% CI:1.33 – 11.36), past week of Internet use for

pornography purpose (OR: 2.52; 95% CI:1.07 – 5.93), having gambling problem (OR: 3.65;

95% CI:1.64 – 8.12), involvement in drug use in the past 12 months (OR: 6.81; 95% CI:1.42

– 32.77) and having moderate/severe depression (OR: 4.32; 95% CI:1.83 – 10.22). University

authorities need to be aware of the prevalence so that interventions can be developed to

prevent adverse outcomes. Interventions should focus on screening students for PIU, creating

awareness on the negative effects of PIU and promoting healthy and active lifestyle and

restricting students’ access to harmful websites.

Keywords: internet addiction, prevalence, risk factors, tertiary students, Malaysia

In this digital world, the growing Internet use has led to problematic behavior such as

excessive use and several terms have been coined to describe such behavior such as Internet

addiction (IA), Internet dependence, problematic Internet use, compulsive Internet use,

pathological Internet use (PIU), excessive Internet use (Rial Boubeta et al. 2015). PIU is when

a person has excessive or poorly-controlled preoccupations, urges or behaviors related to

Internet use resulting in impairment and distress to their life (Shaw & Black, 2008).

In the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-

5), the American Psychiatric Association (APA, 2012) has included Internet Use Disorder as

their clinical diagnosis. In this paper, PIU is used to define someone with Internet problem

with a potentially pathological behavioral problem and does not refer to a clinical diagnosis,

since the instrument used in this study to assess Internet problem is based on a screening tool.

Also PIU is a preferred term as compared to IA where the latter refers to dependency on

psychoactive substances (Davis, 2001).

1 Research Assistant, Department of Primary Care Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Kuala

Lumpur, Malaysia

2 Research Fellow, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

3 Professor, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Email: lowwy@um.edu.my

4 Associate Professor, Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya,

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

5 Lecturer, Department of Primary Care Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur,

Malaysia

The Journal of Behavioral Science Copyright © Behavioral Science Research Institute

2019, Vol. 14, Issue 1, 63-83 ISSN: 1906-4675 (Print), 2651-2246 (Online)

63

Prevalence and Determinants of Pathological Internet Use among

Undergraduate Students in a Public University in Malaysia

Wen Ting Tong1, Md. Ashraful Islam2, Wah Yun Low3, Wan Yuen Choo4,

and Adina Abdullah5

Pathological Internet Use (PIU) affects one’s physical and mental health, and university

students are at risk as they are more likely to develop PIU. This study determines the

prevalence of PIU and its associated factors among students in a public university in

Malaysia. This cross-sectional study was conducted among 1023 undergraduate students in

2015. The questionnaire comprised of items from the Young’s Diagnostic Questionnaire to

assess PIU and items related to socio-demography, psychosocial, lifestyle and co-morbidities.

Anonymous paper-based data collection method was adopted. Mean age of the respondents

was 20.73 ± 1.49 years old. The prevalence of pathological Internet user was 28.9% mostly

Chinese (31%), 22 years old and above (31.0%), in Year 1 (31.5%), and those who perceived

themselves to be from family from higher socio-economic status (32.5%). The factors found

statistically significant (p<0.05) with PIU were Internet use for three or more hours for

recreational purpose (OR: 3.89; 95% CI:1.33 – 11.36), past week of Internet use for

pornography purpose (OR: 2.52; 95% CI:1.07 – 5.93), having gambling problem (OR: 3.65;

95% CI:1.64 – 8.12), involvement in drug use in the past 12 months (OR: 6.81; 95% CI:1.42

– 32.77) and having moderate/severe depression (OR: 4.32; 95% CI:1.83 – 10.22). University

authorities need to be aware of the prevalence so that interventions can be developed to

prevent adverse outcomes. Interventions should focus on screening students for PIU, creating

awareness on the negative effects of PIU and promoting healthy and active lifestyle and

restricting students’ access to harmful websites.

Keywords: internet addiction, prevalence, risk factors, tertiary students, Malaysia

In this digital world, the growing Internet use has led to problematic behavior such as

excessive use and several terms have been coined to describe such behavior such as Internet

addiction (IA), Internet dependence, problematic Internet use, compulsive Internet use,

pathological Internet use (PIU), excessive Internet use (Rial Boubeta et al. 2015). PIU is when

a person has excessive or poorly-controlled preoccupations, urges or behaviors related to

Internet use resulting in impairment and distress to their life (Shaw & Black, 2008).

In the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-

5), the American Psychiatric Association (APA, 2012) has included Internet Use Disorder as

their clinical diagnosis. In this paper, PIU is used to define someone with Internet problem

with a potentially pathological behavioral problem and does not refer to a clinical diagnosis,

since the instrument used in this study to assess Internet problem is based on a screening tool.

Also PIU is a preferred term as compared to IA where the latter refers to dependency on

psychoactive substances (Davis, 2001).

1 Research Assistant, Department of Primary Care Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Kuala

Lumpur, Malaysia

2 Research Fellow, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

3 Professor, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Email: lowwy@um.edu.my

4 Associate Professor, Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya,

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

5 Lecturer, Department of Primary Care Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur,

Malaysia

The Journal of Behavioral Science Copyright © Behavioral Science Research Institute

2019, Vol. 14, Issue 1, 63-83 ISSN: 1906-4675 (Print), 2651-2246 (Online)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Pathological Internet Use among Undergraduate Students

64

Currently, most studies on PIU have been focused largely in Europe and US where

PIU has been a prominent issue in the adolescent health literature. Internet addiction has

become more prevalent in Asia than in other parts of the world (Yen, Yen, & Ko, 2010). In a

meta-analysis of 31 nations across seven world regions, the global prevalence of Internet

addiction was 6.0% (Cheng & Li, 2014). In East Asian countries, most studies were from

Taiwan, China, Korea and Singapore, however, literature are scarce in other Asian

counterparts (Kuss, Griffiths, & Binder, 2013; Lam, 2014). In Asia, there is higher variation

in prevalence among young people and adolescents, ranging from 8% to 50.9% (Kim et al.,

2006; Mak et al., 2014). In China, the rates ranged from 6% to 26.5% (Cao et al., 2011, Lai et

al., 2013, Wu et al., 2013, Chi, Lin & Zhang, 2016; Xin et al., 2018). In one study among

adolescents in six Asian countries, namely China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia

and the Philippines, there were variations in internet behaviors and addiction across these

countries (Mak et al., 2014). Further, the study found that the prevalence of addictive Internet

use ranges from 1% in South Korea to 5% in the Philippines, and the prevalence of

problematic Internet use ranges from 13% in South Korea to 46% in the Philippines, as

measured by the Internet Addiction Test (IAT). Further, based on the Revised Chen Internet

Addiction Scale (CTAS-R), the prevalence of addictive Internet use in the six countries are as

follows: Philippines (21%), Hong Kong (16%), Malaysia (14%), South Korea (10%), China

(10%) and Japan (6%) (Mak et al., 2014). Elsewhere, a cross-sectional study in five ASEAN

countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam), the overall prevalence of

pathological Internet use was 35.9% (ranging from 16.1% in Myanmar to 52.4% in Thailand),

maladaptive use 34.8% and adjusted Internet users 29.9% (Turnbull et al., 2018). Among

these five ASEAN countries, the highest prevalence of pathological Internet use is Thailand

(52.4%) followed by Indonesia (38.5%), Vietnam (37.5%), Malaysia (28.9%), and Myanmar

(16.1%) (Turnbull et al., 2018). Other parts of Asia, in Nepal among undergraduate students,

the prevalence rate of Internet addiction was 35.4% (Bhandari et al., 2017). In Japan, among

junior and high school students, the prevalence of Internet addiction was 8.1% (Marioka et al.,

2017), in South India, among 2776 University students, the prevalence was 29.9% for mild

Internet addiction, 16.4% for moderate addictive use and 0.5% for severe Internet addiction

(Anand et al., 2018). In Asia, Internet use is indeed a problematic issue, and a public health

concern.

Malaysia, a multiethnic country located in Southeast Asia, is not without its negative

consequences of technological advancement. As the country becomes more advanced,

developed, and technologically savvy, this comes with a price. Based on the Malaysian

Communication and Multimedia Commission (MCMC), Internet addiction among Malaysians

has reached an alarming rate. According to the MCMC (2017), smartphones are the most

common device to access the Internet (89.4%), with 57.4% of users being male, and 67.2%

being from urban areas. Additionally, 83.2% of children aged 5 – 17 use the internet. In the

Malaysian Internet User survey (MCMC, 2015), university/college students comprised of

62.5% of internet users who were schooling. 80% accessed the web for social media usage

with the average usage period being over four hours a day, and 89% were found to be

addicted to the Internet. Further, 60% of the respondents showed elevated levels of anxiety

and 32% suffered from major depression. These findings are a cause for concern with

negative implications for the individual, family and the community.

64

Currently, most studies on PIU have been focused largely in Europe and US where

PIU has been a prominent issue in the adolescent health literature. Internet addiction has

become more prevalent in Asia than in other parts of the world (Yen, Yen, & Ko, 2010). In a

meta-analysis of 31 nations across seven world regions, the global prevalence of Internet

addiction was 6.0% (Cheng & Li, 2014). In East Asian countries, most studies were from

Taiwan, China, Korea and Singapore, however, literature are scarce in other Asian

counterparts (Kuss, Griffiths, & Binder, 2013; Lam, 2014). In Asia, there is higher variation

in prevalence among young people and adolescents, ranging from 8% to 50.9% (Kim et al.,

2006; Mak et al., 2014). In China, the rates ranged from 6% to 26.5% (Cao et al., 2011, Lai et

al., 2013, Wu et al., 2013, Chi, Lin & Zhang, 2016; Xin et al., 2018). In one study among

adolescents in six Asian countries, namely China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia

and the Philippines, there were variations in internet behaviors and addiction across these

countries (Mak et al., 2014). Further, the study found that the prevalence of addictive Internet

use ranges from 1% in South Korea to 5% in the Philippines, and the prevalence of

problematic Internet use ranges from 13% in South Korea to 46% in the Philippines, as

measured by the Internet Addiction Test (IAT). Further, based on the Revised Chen Internet

Addiction Scale (CTAS-R), the prevalence of addictive Internet use in the six countries are as

follows: Philippines (21%), Hong Kong (16%), Malaysia (14%), South Korea (10%), China

(10%) and Japan (6%) (Mak et al., 2014). Elsewhere, a cross-sectional study in five ASEAN

countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam), the overall prevalence of

pathological Internet use was 35.9% (ranging from 16.1% in Myanmar to 52.4% in Thailand),

maladaptive use 34.8% and adjusted Internet users 29.9% (Turnbull et al., 2018). Among

these five ASEAN countries, the highest prevalence of pathological Internet use is Thailand

(52.4%) followed by Indonesia (38.5%), Vietnam (37.5%), Malaysia (28.9%), and Myanmar

(16.1%) (Turnbull et al., 2018). Other parts of Asia, in Nepal among undergraduate students,

the prevalence rate of Internet addiction was 35.4% (Bhandari et al., 2017). In Japan, among

junior and high school students, the prevalence of Internet addiction was 8.1% (Marioka et al.,

2017), in South India, among 2776 University students, the prevalence was 29.9% for mild

Internet addiction, 16.4% for moderate addictive use and 0.5% for severe Internet addiction

(Anand et al., 2018). In Asia, Internet use is indeed a problematic issue, and a public health

concern.

Malaysia, a multiethnic country located in Southeast Asia, is not without its negative

consequences of technological advancement. As the country becomes more advanced,

developed, and technologically savvy, this comes with a price. Based on the Malaysian

Communication and Multimedia Commission (MCMC), Internet addiction among Malaysians

has reached an alarming rate. According to the MCMC (2017), smartphones are the most

common device to access the Internet (89.4%), with 57.4% of users being male, and 67.2%

being from urban areas. Additionally, 83.2% of children aged 5 – 17 use the internet. In the

Malaysian Internet User survey (MCMC, 2015), university/college students comprised of

62.5% of internet users who were schooling. 80% accessed the web for social media usage

with the average usage period being over four hours a day, and 89% were found to be

addicted to the Internet. Further, 60% of the respondents showed elevated levels of anxiety

and 32% suffered from major depression. These findings are a cause for concern with

negative implications for the individual, family and the community.

Wen Ting Tong, Md. Ashraful Islam, Wah Yun Low, Wan Yuen Choo, and Adina Abdullah

65

Other local Malaysian studies also showed a variation in the prevalence rates of

Internet addiction due to the methodology employed. Cheng and Li’s (2014) meta-analysis of

31 nations across seven regions in the world, among 12-18 years old adolescents, 2.4% of

Malaysian adolescents were reported being addicted to Internet, and 35.1% were found

having problematic Internet use. In one study among secondary school students, 28.6% of the

respondents were addicted to the Internet (Mohd Isa, Hashim, Kaur, & Ng, 2016). Yet, in

another study among undergraduate students in a public university, the prevalence of Internet

addiction was 7.8% and 56.5% were problematic Internet users (Rosliza, Ragubathi,

Mohamad Yusoff, & Shaharuddin, 2018). Zainudin, Md Din, & Othman, (2013) also in their

study among undergraduate students, found 30% prevalence of excessive Internet users.

Among local medical students, a study showed a prevalence of 36.9% Internet addiction

(Ching et al., 2017). As to the impact of Internet addiction on young Malaysian adults, (Alam

et al., 2014) showed those adults using Internet excessively were having problems, such as,

interpersonal, behavioral, physical, psychological and work problems in their daily lives.

Internet addiction in adolescents and young adults has become a public health issue

and has an impact on health education and health promotion. Excessive and inappropriate use

of the Internet can pose serious negative consequences on one’s mental health and quality of

life (Kuss & Griffiths, 2012, Alam et al., 2014). Thus, this paper examined the prevalence of

pathological internal use among university students in Kuala Lumpur and its associated

factors. It is hypothesized that pathological Internet use is associated with socio-demographic

factors, gender, age, life satisfaction, time spent on Internet, Internet use patterns, history of

child abuse and other psychosocial factors. The literature reviewed will further illustrate the

relationship between pathological Internet use and its various associated factors.

Literature Review

There are many factors associated with Internet use, such as sociodemographic

variables, such as gender, time spent online, psychosocial factors, life satisfaction, and history

of child abuse and other comorbid symptoms, such as depression, harmful substance abuse

and sleeping disorder. Socio-demographic factors such as gender, family socio-economic

status, types of residence; duration of Internet use for study or recreational purpose;

psychosocial factors such as low academic achievement, low life satisfaction; and comorbid

symptoms such as alcohol and substance use and depression have been associated with PIU in

adolescents and young people (Kuss, Griffiths, Karila, & Billieux, 2014, Turnbull et al.,

2018). Bozogplan, Demirer, & Sahin, (2013) found that loneliness, self-esteem and life

satisfaction explained 38% of the total variance in Internet addiction.

A number of studies have shown that the male gender is more susceptible to Internet

addiction (Carli et al., 2013; Anand et al., 2018). Anand et al. (2018) in their study among

undergraduate students, aged 18-21 years old in South India found that IA was higher among

male students, i.e. 2.8 times at a higher risk of engaging IA. One study among school

adolescents in China, showed that mild and severe IA was significantly higher in boys than in

girls (Xin et. al., 2018). Among Malaysian medical students, the male students were 1.8 times

more at risk of Internet addiction (Ching, et al., 2017). College and University students are

more susceptible to PIU (Kim, Griffiths, Lau, Fong, & Lam, 2013; Ozcan, & Buzlu, 2007;

Chi, Lin, & Zhang, 2016) due to reasons such as early exposure to the Internet, lack of

parental supervision, the availability and free access to the Internet at the university campus,

65

Other local Malaysian studies also showed a variation in the prevalence rates of

Internet addiction due to the methodology employed. Cheng and Li’s (2014) meta-analysis of

31 nations across seven regions in the world, among 12-18 years old adolescents, 2.4% of

Malaysian adolescents were reported being addicted to Internet, and 35.1% were found

having problematic Internet use. In one study among secondary school students, 28.6% of the

respondents were addicted to the Internet (Mohd Isa, Hashim, Kaur, & Ng, 2016). Yet, in

another study among undergraduate students in a public university, the prevalence of Internet

addiction was 7.8% and 56.5% were problematic Internet users (Rosliza, Ragubathi,

Mohamad Yusoff, & Shaharuddin, 2018). Zainudin, Md Din, & Othman, (2013) also in their

study among undergraduate students, found 30% prevalence of excessive Internet users.

Among local medical students, a study showed a prevalence of 36.9% Internet addiction

(Ching et al., 2017). As to the impact of Internet addiction on young Malaysian adults, (Alam

et al., 2014) showed those adults using Internet excessively were having problems, such as,

interpersonal, behavioral, physical, psychological and work problems in their daily lives.

Internet addiction in adolescents and young adults has become a public health issue

and has an impact on health education and health promotion. Excessive and inappropriate use

of the Internet can pose serious negative consequences on one’s mental health and quality of

life (Kuss & Griffiths, 2012, Alam et al., 2014). Thus, this paper examined the prevalence of

pathological internal use among university students in Kuala Lumpur and its associated

factors. It is hypothesized that pathological Internet use is associated with socio-demographic

factors, gender, age, life satisfaction, time spent on Internet, Internet use patterns, history of

child abuse and other psychosocial factors. The literature reviewed will further illustrate the

relationship between pathological Internet use and its various associated factors.

Literature Review

There are many factors associated with Internet use, such as sociodemographic

variables, such as gender, time spent online, psychosocial factors, life satisfaction, and history

of child abuse and other comorbid symptoms, such as depression, harmful substance abuse

and sleeping disorder. Socio-demographic factors such as gender, family socio-economic

status, types of residence; duration of Internet use for study or recreational purpose;

psychosocial factors such as low academic achievement, low life satisfaction; and comorbid

symptoms such as alcohol and substance use and depression have been associated with PIU in

adolescents and young people (Kuss, Griffiths, Karila, & Billieux, 2014, Turnbull et al.,

2018). Bozogplan, Demirer, & Sahin, (2013) found that loneliness, self-esteem and life

satisfaction explained 38% of the total variance in Internet addiction.

A number of studies have shown that the male gender is more susceptible to Internet

addiction (Carli et al., 2013; Anand et al., 2018). Anand et al. (2018) in their study among

undergraduate students, aged 18-21 years old in South India found that IA was higher among

male students, i.e. 2.8 times at a higher risk of engaging IA. One study among school

adolescents in China, showed that mild and severe IA was significantly higher in boys than in

girls (Xin et. al., 2018). Among Malaysian medical students, the male students were 1.8 times

more at risk of Internet addiction (Ching, et al., 2017). College and University students are

more susceptible to PIU (Kim, Griffiths, Lau, Fong, & Lam, 2013; Ozcan, & Buzlu, 2007;

Chi, Lin, & Zhang, 2016) due to reasons such as early exposure to the Internet, lack of

parental supervision, the availability and free access to the Internet at the university campus,

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Pathological Internet Use among Undergraduate Students

66

the need to use Internet to perform academic activities (Ko, Yen, Chen, Chen, & Yen, 2008)

to cope with anxiety, depression, and stress of university’s life (Hicks & Heastie, 2008) and,

for social networking (van Rooij, Schoenmakers, van de Eijnden, & van de Mheen, 2010).

The quality of the family environment and parent-child relationships were also shown to be

linked to Internet addiction (Chi, Lin, & Zhang, 2016). The excessive use of the Internet has

also impacted on students’ academic performance and social interaction (Yen, Yen, & Ko,

2010; Durkee et al., 2016; Turnbull et al., 2018).

Internet use pattern is also something to reckon with, as the pattern varies from study

to study. Mak et al., (2014) in their six Asian countries epidemiological study of Internet

behaviors among adolescents aged 12-18 years old, found that emails (66%), instant messages

(50%), blogging (25%), and visiting leisure web sites (20%) are relatively more common in

Japan, whereas social networking (65%), newsgroup/discussion groups/forums (19%), non-

purposive web surfing (27%), online shopping (8%), and downloading (28%) are relatively

more common in Hong Kong. In Malaysia, most common are for social networking (38%),

followed by online gaming (19%), downloading (19%), web surfing (14%), visiting leisure

websites (13%), email (12%), listening to online radio (10%), Instant messenger (9%), and

others (Mak et al., 2014). In another ASEAN study of 5 countries among undergraduate

students (Turnbull et al., 2018), it was found that among those with PIU, overall Internet

usage was more than 5 hours/day, followed by Internet use for recreation purposes (more than

3 hours/per), Internet for pornography, Smartphone use, and Internet use for study purposes.

It is obvious that students use the Internet for a variety of purposes. A Malaysian study on

medical students found that the use of Internet was mainly for entertainment purposes,

followed by education and the mixture of both entertainment and education purposes (Ching,

et al., 2017). Based on the recent Internet Users Survey 2017 (MCMC, 2017), text

communication (96.3%) and visiting social network site (89.3%), were the most common

activities for Internet users as well as getting information online (86.9%).

A study among Hong Kong and Macau university students have reported that having

more liberal sexual attitudes, stronger perception that sex is as an instrument for biological

needs, poor attitudes towards contraception and ever had sexual experience were significantly

associated with PIU (Ding et al., 2016). Childhood trauma particularly physical and

emotional abuse significantly increases risks of developing PIU (Zhang et al., 2009;

Dalbudak, Evren, Aldemir, & Evren, 2014; Turnbull et. al., 2018). Furthermore, adolescents

who had experienced sexual abuse showed lower self-esteem, more depressive symptoms, and

greater problematic Internet use compared to adolescents who have not experienced sexual

abuse (Kim, Park, & Park, 2017). Childhood abuse has also been related to post-traumatic

stress disorder (PTSD) (Ginzburg et al., 2009; Hsieh et al., 2016). People who have

experienced traumatic events may use avoidance as a means to cope with their negative

memories and emotions and one way to do that is to use the Internet as distraction and this

may lead to addiction.

PIU has impact on physical and psychological health due to poorer diet, less regular

exercise, sedentary activities, less sleep (Kim & Chun, 2005, Mak et al. 2014) resulting in

obesity (Mak et al., 2014; Tsitsika et al., 2016), lower self-perceived immune function (Reed,

Vile, Osborne, Romano, & Truzoli, 2015) and health status; as well as mental problems such

as depression, social anxiety, attention-deficit hyperactive disorder and psychosocial well-

being (Ko, Yen, Yen, Chen, & Chen, 2012; Lai et al., 2015; Mak et al 2014; Sung, Noh, Park,

& Ahn 2013). Co-morbid symptoms, such as, gambling problem, harmful use of alcohol,

66

the need to use Internet to perform academic activities (Ko, Yen, Chen, Chen, & Yen, 2008)

to cope with anxiety, depression, and stress of university’s life (Hicks & Heastie, 2008) and,

for social networking (van Rooij, Schoenmakers, van de Eijnden, & van de Mheen, 2010).

The quality of the family environment and parent-child relationships were also shown to be

linked to Internet addiction (Chi, Lin, & Zhang, 2016). The excessive use of the Internet has

also impacted on students’ academic performance and social interaction (Yen, Yen, & Ko,

2010; Durkee et al., 2016; Turnbull et al., 2018).

Internet use pattern is also something to reckon with, as the pattern varies from study

to study. Mak et al., (2014) in their six Asian countries epidemiological study of Internet

behaviors among adolescents aged 12-18 years old, found that emails (66%), instant messages

(50%), blogging (25%), and visiting leisure web sites (20%) are relatively more common in

Japan, whereas social networking (65%), newsgroup/discussion groups/forums (19%), non-

purposive web surfing (27%), online shopping (8%), and downloading (28%) are relatively

more common in Hong Kong. In Malaysia, most common are for social networking (38%),

followed by online gaming (19%), downloading (19%), web surfing (14%), visiting leisure

websites (13%), email (12%), listening to online radio (10%), Instant messenger (9%), and

others (Mak et al., 2014). In another ASEAN study of 5 countries among undergraduate

students (Turnbull et al., 2018), it was found that among those with PIU, overall Internet

usage was more than 5 hours/day, followed by Internet use for recreation purposes (more than

3 hours/per), Internet for pornography, Smartphone use, and Internet use for study purposes.

It is obvious that students use the Internet for a variety of purposes. A Malaysian study on

medical students found that the use of Internet was mainly for entertainment purposes,

followed by education and the mixture of both entertainment and education purposes (Ching,

et al., 2017). Based on the recent Internet Users Survey 2017 (MCMC, 2017), text

communication (96.3%) and visiting social network site (89.3%), were the most common

activities for Internet users as well as getting information online (86.9%).

A study among Hong Kong and Macau university students have reported that having

more liberal sexual attitudes, stronger perception that sex is as an instrument for biological

needs, poor attitudes towards contraception and ever had sexual experience were significantly

associated with PIU (Ding et al., 2016). Childhood trauma particularly physical and

emotional abuse significantly increases risks of developing PIU (Zhang et al., 2009;

Dalbudak, Evren, Aldemir, & Evren, 2014; Turnbull et. al., 2018). Furthermore, adolescents

who had experienced sexual abuse showed lower self-esteem, more depressive symptoms, and

greater problematic Internet use compared to adolescents who have not experienced sexual

abuse (Kim, Park, & Park, 2017). Childhood abuse has also been related to post-traumatic

stress disorder (PTSD) (Ginzburg et al., 2009; Hsieh et al., 2016). People who have

experienced traumatic events may use avoidance as a means to cope with their negative

memories and emotions and one way to do that is to use the Internet as distraction and this

may lead to addiction.

PIU has impact on physical and psychological health due to poorer diet, less regular

exercise, sedentary activities, less sleep (Kim & Chun, 2005, Mak et al. 2014) resulting in

obesity (Mak et al., 2014; Tsitsika et al., 2016), lower self-perceived immune function (Reed,

Vile, Osborne, Romano, & Truzoli, 2015) and health status; as well as mental problems such

as depression, social anxiety, attention-deficit hyperactive disorder and psychosocial well-

being (Ko, Yen, Yen, Chen, & Chen, 2012; Lai et al., 2015; Mak et al 2014; Sung, Noh, Park,

& Ahn 2013). Co-morbid symptoms, such as, gambling problem, harmful use of alcohol,

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Wen Ting Tong, Md. Ashraful Islam, Wah Yun Low, Wan Yuen Choo, and Adina Abdullah

67

drug use in the past 12 months, mental distress, e.g. severe depression, PTSD symptoms,

sleeping problems and suicidal attempts, are also related to PIU (Turnbull et al. 2018). Carli et

al., (2013) and Yen et al., (2007) suggest that depression is a leading comorbid disorder with

IA. Individuals with negative self-esteem are at risk of engaging in addictive Internet

behaviors which helps to momentarily free themselves of their negative self-esteem, irrational

cognitive assumptions and associated unpleasant emotions (Griffiths, 2000). Thus, one way

of relieving stress among university students is by interacting with their computers, and this

works as a coping mechanisms for them.

PIU is indeed a very complex issue and can manifest itself in a pathological,

behavioral and emotional way and there are also many theories that explain PIU. Among

others, is the cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use proposed by Davis

(2001) to explain the etiology of this phenomenon. This model emphasizes the individual’s

cognitions (or thoughts) as the main source of abnormal behavior, and these cognitive

symptoms (e.g. feeling of self-consciousness, low self-esteem, low self-worth, social anxiety,

etc.) of PIU often precede and cause the affective or behavioral symptoms. Thus, the

etiological factor must be present or must have occurred in order for the symptoms to occur

(in this case, the Internet use). So, the maladaptive cognitions (e.g. distorted thoughts and the

thought processes) are sufficient to cause the symptoms of PIU, such as, the obsessive

thoughts about Internet usage, or having less time to do other things, etc. (Davis, 2001). This

model is important to explain the role of cognitions in PIU.

In view of the literature above, it is thus important to determine the extent of PIU and

its associated factors so that interventions can be developed to prevent the onset of negative

consequences of PIU among university students who are the future policy makers of a nation.

Therefore, this study begs the research questions as to how serious is PIU in Malaysia among

University students, and how the various socio-demographic factors, psychosocial issues,

Internet use patterns, history of child abuse, and co-morbid conditions are affected by PIU. It

is also hypothesized that the socio-demographic variables together with the various psycho-

social variables are related to PIU.

Objectives

This study aimed (1) to determine the prevalence of PIU using the Young’s Diagnostic

Questionnaire (Young, 1998), where the diagnosis of PIU was established when there is a

score of ≥ 5; and (2) to determine the associated factors pertaining to socio-demography (age,

gender, perceived income status, academic performance), post-traumatic stress disorder,

history of child abuse, Internet use patterns and co-morbid symptoms using logistic

regression.

Methods

Study Design and Sampling

This cross-sectional study was conducted between July to September 2015 among

Malaysian undergraduate students in a public university in Kuala Lumpur. The particular

university in this study was purposely selected because it is the premier university in the

country. University students were chosen as the literature review has shown that this is the

age group that are most vulnerable, being Internet savvy and frequently exposed to

67

drug use in the past 12 months, mental distress, e.g. severe depression, PTSD symptoms,

sleeping problems and suicidal attempts, are also related to PIU (Turnbull et al. 2018). Carli et

al., (2013) and Yen et al., (2007) suggest that depression is a leading comorbid disorder with

IA. Individuals with negative self-esteem are at risk of engaging in addictive Internet

behaviors which helps to momentarily free themselves of their negative self-esteem, irrational

cognitive assumptions and associated unpleasant emotions (Griffiths, 2000). Thus, one way

of relieving stress among university students is by interacting with their computers, and this

works as a coping mechanisms for them.

PIU is indeed a very complex issue and can manifest itself in a pathological,

behavioral and emotional way and there are also many theories that explain PIU. Among

others, is the cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use proposed by Davis

(2001) to explain the etiology of this phenomenon. This model emphasizes the individual’s

cognitions (or thoughts) as the main source of abnormal behavior, and these cognitive

symptoms (e.g. feeling of self-consciousness, low self-esteem, low self-worth, social anxiety,

etc.) of PIU often precede and cause the affective or behavioral symptoms. Thus, the

etiological factor must be present or must have occurred in order for the symptoms to occur

(in this case, the Internet use). So, the maladaptive cognitions (e.g. distorted thoughts and the

thought processes) are sufficient to cause the symptoms of PIU, such as, the obsessive

thoughts about Internet usage, or having less time to do other things, etc. (Davis, 2001). This

model is important to explain the role of cognitions in PIU.

In view of the literature above, it is thus important to determine the extent of PIU and

its associated factors so that interventions can be developed to prevent the onset of negative

consequences of PIU among university students who are the future policy makers of a nation.

Therefore, this study begs the research questions as to how serious is PIU in Malaysia among

University students, and how the various socio-demographic factors, psychosocial issues,

Internet use patterns, history of child abuse, and co-morbid conditions are affected by PIU. It

is also hypothesized that the socio-demographic variables together with the various psycho-

social variables are related to PIU.

Objectives

This study aimed (1) to determine the prevalence of PIU using the Young’s Diagnostic

Questionnaire (Young, 1998), where the diagnosis of PIU was established when there is a

score of ≥ 5; and (2) to determine the associated factors pertaining to socio-demography (age,

gender, perceived income status, academic performance), post-traumatic stress disorder,

history of child abuse, Internet use patterns and co-morbid symptoms using logistic

regression.

Methods

Study Design and Sampling

This cross-sectional study was conducted between July to September 2015 among

Malaysian undergraduate students in a public university in Kuala Lumpur. The particular

university in this study was purposely selected because it is the premier university in the

country. University students were chosen as the literature review has shown that this is the

age group that are most vulnerable, being Internet savvy and frequently exposed to

Pathological Internet Use among Undergraduate Students

68

communications via social media. The total undergraduate student body at the time of study

was 11,908 from 16 faculties, 2 centers and 2 academies. A stratified cluster sampling was

used to draw the sample. All the faculties, centers and academies formed the clusters and were

included in the sampling frame. Within each cluster, the student populations were stratified by

gender in order to obtain equal representation of both males and females. The number of

students selected from each cluster are proportional to size. Undergraduate students from year

1 to 5 form all the clusters, as those who are currently studying at the university were invited

to participate on a voluntary basis.

Measurements

The questionnaire used for this study was a combination of items from the following:

PIU was assessed using the Young’s Diagnostic Questionnaire (YDQ) (Young, 1998).

The YDQ was developed based on the diagnostic criterion of pathological gambling listed in

the DSM-4 (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The YDQ comprised of 8 “yes” and

“no” items assessing patterns of Internet usage in terms of preoccupation, tolerance, loss of

control, withdrawal, negative consequences, denial, and escapism (scoring 0-8). One point

was given to each “Yes” answer. Diagnosis of PIU was established when there is a score of ≥

5. The Cronbach’s Alpha value was 0.678.

Socio-demographic variables including age, gender, ethnicity, current year of study,

self-perceived economic status and current residence (6 items). The item on self-perceived

economic status had a response options from 1=wealthy (within the highest 25% in your

country in terms of wealth), 2=Quite well-off (within the 50-75% range for your country),

3=Not very well off (within the 25-50% range for your country) and 4=Quite poor (within the

lowest 25% in your country in terms of wealth).

Internet use variables were open ended items on number of hours spent on the Internet

in a day, number of hours spent on the Internet for study purposes and recreational purposes

in a day, number of hours spent on the Internet for pornography in a week and number of

hours using smartphone in a day (5 items).

Psychosocial variables included items from the World Health Organization adverse

childhood experience scale (CDC, 2016; WHO, 2016) to measure child abuse experiences in

terms of emotional (5 items; Cronbach’s Alpha (0.78)), physical (2 items; Cronbach’s Alpha

(0.74)) and sexual abuse (4 items; Cronbach’s Alpha (0.81)).

Self-perceived life satisfaction was measured using one-item: “All things considered,

how satisfied are you with your life as a whole?” adapted from Lucas & Donnellan (2012).

The response options ranged from 1=very satisfied to 5=very dissatisfied.

Self-perceived academic performance was measured using one-item “How would you

rate your academic performance” with response options from 1=excellent to 5=poor.

Co-morbid symptoms measured were: gambling, measured using the item “Have you

felt that you might have a problem with gambling?” with response options from 0=never,

1=sometimes, 2=most of the time, 3=almost always; tobacco use measured using the item

“Do you currently use one or more of the following tobacco products (cigarettes, snuff,

chewing tobacco, cigars, etc.) with response options “yes” and “no” (World Health

Organization, 1998); and drug use measured using the item “How often have you taken drugs

in the past 12 months; other than prescribed by healthcare providers?” with response options

68

communications via social media. The total undergraduate student body at the time of study

was 11,908 from 16 faculties, 2 centers and 2 academies. A stratified cluster sampling was

used to draw the sample. All the faculties, centers and academies formed the clusters and were

included in the sampling frame. Within each cluster, the student populations were stratified by

gender in order to obtain equal representation of both males and females. The number of

students selected from each cluster are proportional to size. Undergraduate students from year

1 to 5 form all the clusters, as those who are currently studying at the university were invited

to participate on a voluntary basis.

Measurements

The questionnaire used for this study was a combination of items from the following:

PIU was assessed using the Young’s Diagnostic Questionnaire (YDQ) (Young, 1998).

The YDQ was developed based on the diagnostic criterion of pathological gambling listed in

the DSM-4 (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The YDQ comprised of 8 “yes” and

“no” items assessing patterns of Internet usage in terms of preoccupation, tolerance, loss of

control, withdrawal, negative consequences, denial, and escapism (scoring 0-8). One point

was given to each “Yes” answer. Diagnosis of PIU was established when there is a score of ≥

5. The Cronbach’s Alpha value was 0.678.

Socio-demographic variables including age, gender, ethnicity, current year of study,

self-perceived economic status and current residence (6 items). The item on self-perceived

economic status had a response options from 1=wealthy (within the highest 25% in your

country in terms of wealth), 2=Quite well-off (within the 50-75% range for your country),

3=Not very well off (within the 25-50% range for your country) and 4=Quite poor (within the

lowest 25% in your country in terms of wealth).

Internet use variables were open ended items on number of hours spent on the Internet

in a day, number of hours spent on the Internet for study purposes and recreational purposes

in a day, number of hours spent on the Internet for pornography in a week and number of

hours using smartphone in a day (5 items).

Psychosocial variables included items from the World Health Organization adverse

childhood experience scale (CDC, 2016; WHO, 2016) to measure child abuse experiences in

terms of emotional (5 items; Cronbach’s Alpha (0.78)), physical (2 items; Cronbach’s Alpha

(0.74)) and sexual abuse (4 items; Cronbach’s Alpha (0.81)).

Self-perceived life satisfaction was measured using one-item: “All things considered,

how satisfied are you with your life as a whole?” adapted from Lucas & Donnellan (2012).

The response options ranged from 1=very satisfied to 5=very dissatisfied.

Self-perceived academic performance was measured using one-item “How would you

rate your academic performance” with response options from 1=excellent to 5=poor.

Co-morbid symptoms measured were: gambling, measured using the item “Have you

felt that you might have a problem with gambling?” with response options from 0=never,

1=sometimes, 2=most of the time, 3=almost always; tobacco use measured using the item

“Do you currently use one or more of the following tobacco products (cigarettes, snuff,

chewing tobacco, cigars, etc.) with response options “yes” and “no” (World Health

Organization, 1998); and drug use measured using the item “How often have you taken drugs

in the past 12 months; other than prescribed by healthcare providers?” with response options

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Wen Ting Tong, Md. Ashraful Islam, Wah Yun Low, Wan Yuen Choo, and Adina Abdullah

69

from 1= 0 times, 2=1-2 times, 3=3-9 times and 4 = ≥ 10 times. The Alcohol Use Disorder

Identification Test (AUDIT-C, 3 items). was used to assess harmful alcohol use, with

response options ranging from 0=never, 1=less than monthly, 2=monthly, 3=weekly and

4=daily or almost daily. A score greater than or equal to three was considered harmful for

women and a score greater than or equal to four for was considered harmful for men (Bush,

Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998).

Depression was screened using the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression

Scale (CES-D, 10 items) with a Likert-scale from 1=Rarely (<1day), 2=Some/little (1-2 days),

3= Much (3-4 days) and 4=Most (5-7 days). A score of more than 10 indicates moderate

depression, ≥ 15 indicates severe depression (Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994).

The Cronbach’s Alpha value was 0.71.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the past month was screened using Breslau’s

7-item screening scale. A score of ≥ four indicates positive for PTSD (Kimerling et al., 2006).

The Cronbach’s Alpha value was 0.81.

Data Collection Process

This study received ethics approval from the University of Malaya Medical Ethics

Committee (ref: MECID.NO: 201412-905).

On data collection days, the enumerators were stationed at common student areas

within the faculties, centers and academies where students were most likely to be found.

Trained enumerators approached students and explained about the study purpose, anonymity,

voluntariness and the consent of participation study. Written informed consent were obtained

from them before paper questionnaire were given for self-administration. Data collection

ceased when the number of samples required for both gender within each cluster were

achieved.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed to provide socio-demographic, psychosocial,

Internet use patterns and co-morbid symptoms information for non-PIU and PIU and,

addiction symptoms that were common among the respondents. Bivariate logistic regression

was performed to determine the associations between the socio-demographic, Internet use,

psychosocial and co-morbid symptoms variables with respondents with PIU. Factors, which

were found to be significant, were then included in the model for multiple binary logistic

regression using the ‘Enter’ method, and the factors associated with PIU were identified. The

crude and adjusted odds ratios with its 95% confidence interval were reported, where

applicable. Data analysis was conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

Version 20 (IBM Corporation, 2015). Significance were determined by using p<0.05.

Results

A total of 1132 students were approached during data collection. However, only 1023

completed the questionnaire were included in the data analysis (response rate: 90.4%). The

mean age of the respondents was 20.73 ± 1.49 years old (ranging from 18 to 28 years old).

There was almost equal proportion of female (50.90%) and male (49.1%) respondents. More

than half of the respondents were Malay (52.3%) followed by Chinese (40.0%), Indian (3.9%)

69

from 1= 0 times, 2=1-2 times, 3=3-9 times and 4 = ≥ 10 times. The Alcohol Use Disorder

Identification Test (AUDIT-C, 3 items). was used to assess harmful alcohol use, with

response options ranging from 0=never, 1=less than monthly, 2=monthly, 3=weekly and

4=daily or almost daily. A score greater than or equal to three was considered harmful for

women and a score greater than or equal to four for was considered harmful for men (Bush,

Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998).

Depression was screened using the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression

Scale (CES-D, 10 items) with a Likert-scale from 1=Rarely (<1day), 2=Some/little (1-2 days),

3= Much (3-4 days) and 4=Most (5-7 days). A score of more than 10 indicates moderate

depression, ≥ 15 indicates severe depression (Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994).

The Cronbach’s Alpha value was 0.71.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the past month was screened using Breslau’s

7-item screening scale. A score of ≥ four indicates positive for PTSD (Kimerling et al., 2006).

The Cronbach’s Alpha value was 0.81.

Data Collection Process

This study received ethics approval from the University of Malaya Medical Ethics

Committee (ref: MECID.NO: 201412-905).

On data collection days, the enumerators were stationed at common student areas

within the faculties, centers and academies where students were most likely to be found.

Trained enumerators approached students and explained about the study purpose, anonymity,

voluntariness and the consent of participation study. Written informed consent were obtained

from them before paper questionnaire were given for self-administration. Data collection

ceased when the number of samples required for both gender within each cluster were

achieved.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed to provide socio-demographic, psychosocial,

Internet use patterns and co-morbid symptoms information for non-PIU and PIU and,

addiction symptoms that were common among the respondents. Bivariate logistic regression

was performed to determine the associations between the socio-demographic, Internet use,

psychosocial and co-morbid symptoms variables with respondents with PIU. Factors, which

were found to be significant, were then included in the model for multiple binary logistic

regression using the ‘Enter’ method, and the factors associated with PIU were identified. The

crude and adjusted odds ratios with its 95% confidence interval were reported, where

applicable. Data analysis was conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

Version 20 (IBM Corporation, 2015). Significance were determined by using p<0.05.

Results

A total of 1132 students were approached during data collection. However, only 1023

completed the questionnaire were included in the data analysis (response rate: 90.4%). The

mean age of the respondents was 20.73 ± 1.49 years old (ranging from 18 to 28 years old).

There was almost equal proportion of female (50.90%) and male (49.1%) respondents. More

than half of the respondents were Malay (52.3%) followed by Chinese (40.0%), Indian (3.9%)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Pathological Internet Use among Undergraduate Students

70

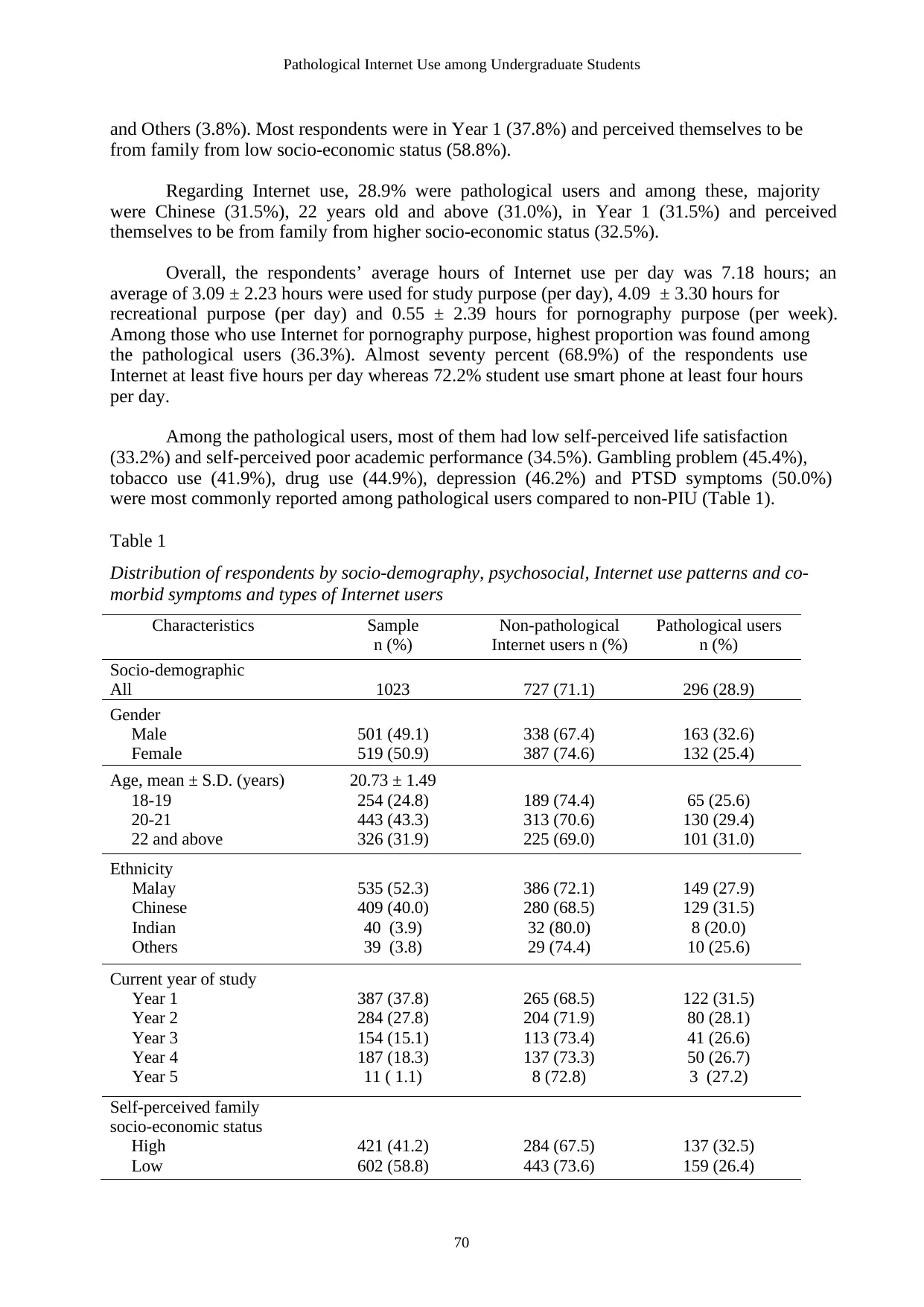

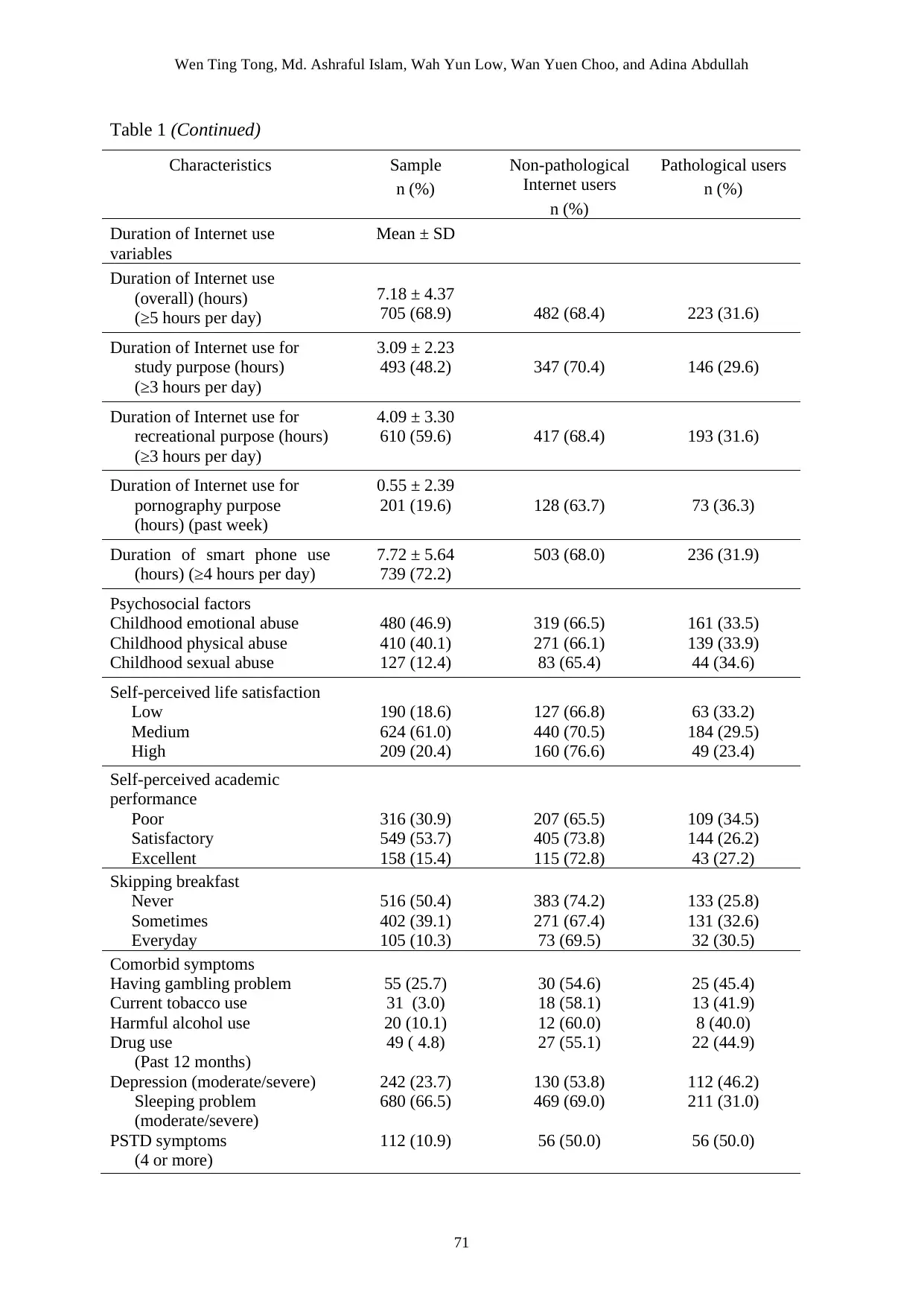

and Others (3.8%). Most respondents were in Year 1 (37.8%) and perceived themselves to be

from family from low socio-economic status (58.8%).

Regarding Internet use, 28.9% were pathological users and among these, majority

were Chinese (31.5%), 22 years old and above (31.0%), in Year 1 (31.5%) and perceived

themselves to be from family from higher socio-economic status (32.5%).

Overall, the respondents’ average hours of Internet use per day was 7.18 hours; an

average of 3.09 ± 2.23 hours were used for study purpose (per day), 4.09 ± 3.30 hours for

recreational purpose (per day) and 0.55 ± 2.39 hours for pornography purpose (per week).

Among those who use Internet for pornography purpose, highest proportion was found among

the pathological users (36.3%). Almost seventy percent (68.9%) of the respondents use

Internet at least five hours per day whereas 72.2% student use smart phone at least four hours

per day.

Among the pathological users, most of them had low self-perceived life satisfaction

(33.2%) and self-perceived poor academic performance (34.5%). Gambling problem (45.4%),

tobacco use (41.9%), drug use (44.9%), depression (46.2%) and PTSD symptoms (50.0%)

were most commonly reported among pathological users compared to non-PIU (Table 1).

Table 1

Distribution of respondents by socio-demography, psychosocial, Internet use patterns and co-

morbid symptoms and types of Internet users

Characteristics Sample

n (%)

Non-pathological

Internet users n (%)

Pathological users

n (%)

Socio-demographic

All 1023 727 (71.1) 296 (28.9)

Gender

Male 501 (49.1) 338 (67.4) 163 (32.6)

Female 519 (50.9) 387 (74.6) 132 (25.4)

Age, mean ± S.D. (years) 20.73 ± 1.49

18-19 254 (24.8) 189 (74.4) 65 (25.6)

20-21 443 (43.3) 313 (70.6) 130 (29.4)

22 and above 326 (31.9) 225 (69.0) 101 (31.0)

Ethnicity

Malay 535 (52.3) 386 (72.1) 149 (27.9)

Chinese 409 (40.0) 280 (68.5) 129 (31.5)

Indian 40 (3.9) 32 (80.0) 8 (20.0)

Others 39 (3.8) 29 (74.4) 10 (25.6)

Current year of study

Year 1 387 (37.8) 265 (68.5) 122 (31.5)

Year 2 284 (27.8) 204 (71.9) 80 (28.1)

Year 3 154 (15.1) 113 (73.4) 41 (26.6)

Year 4 187 (18.3) 137 (73.3) 50 (26.7)

Year 5 11 ( 1.1) 8 (72.8) 3 (27.2)

Self-perceived family

socio-economic status

High 421 (41.2) 284 (67.5) 137 (32.5)

Low 602 (58.8) 443 (73.6) 159 (26.4)

70

and Others (3.8%). Most respondents were in Year 1 (37.8%) and perceived themselves to be

from family from low socio-economic status (58.8%).

Regarding Internet use, 28.9% were pathological users and among these, majority

were Chinese (31.5%), 22 years old and above (31.0%), in Year 1 (31.5%) and perceived

themselves to be from family from higher socio-economic status (32.5%).

Overall, the respondents’ average hours of Internet use per day was 7.18 hours; an

average of 3.09 ± 2.23 hours were used for study purpose (per day), 4.09 ± 3.30 hours for

recreational purpose (per day) and 0.55 ± 2.39 hours for pornography purpose (per week).

Among those who use Internet for pornography purpose, highest proportion was found among

the pathological users (36.3%). Almost seventy percent (68.9%) of the respondents use

Internet at least five hours per day whereas 72.2% student use smart phone at least four hours

per day.

Among the pathological users, most of them had low self-perceived life satisfaction

(33.2%) and self-perceived poor academic performance (34.5%). Gambling problem (45.4%),

tobacco use (41.9%), drug use (44.9%), depression (46.2%) and PTSD symptoms (50.0%)

were most commonly reported among pathological users compared to non-PIU (Table 1).

Table 1

Distribution of respondents by socio-demography, psychosocial, Internet use patterns and co-

morbid symptoms and types of Internet users

Characteristics Sample

n (%)

Non-pathological

Internet users n (%)

Pathological users

n (%)

Socio-demographic

All 1023 727 (71.1) 296 (28.9)

Gender

Male 501 (49.1) 338 (67.4) 163 (32.6)

Female 519 (50.9) 387 (74.6) 132 (25.4)

Age, mean ± S.D. (years) 20.73 ± 1.49

18-19 254 (24.8) 189 (74.4) 65 (25.6)

20-21 443 (43.3) 313 (70.6) 130 (29.4)

22 and above 326 (31.9) 225 (69.0) 101 (31.0)

Ethnicity

Malay 535 (52.3) 386 (72.1) 149 (27.9)

Chinese 409 (40.0) 280 (68.5) 129 (31.5)

Indian 40 (3.9) 32 (80.0) 8 (20.0)

Others 39 (3.8) 29 (74.4) 10 (25.6)

Current year of study

Year 1 387 (37.8) 265 (68.5) 122 (31.5)

Year 2 284 (27.8) 204 (71.9) 80 (28.1)

Year 3 154 (15.1) 113 (73.4) 41 (26.6)

Year 4 187 (18.3) 137 (73.3) 50 (26.7)

Year 5 11 ( 1.1) 8 (72.8) 3 (27.2)

Self-perceived family

socio-economic status

High 421 (41.2) 284 (67.5) 137 (32.5)

Low 602 (58.8) 443 (73.6) 159 (26.4)

Wen Ting Tong, Md. Ashraful Islam, Wah Yun Low, Wan Yuen Choo, and Adina Abdullah

71

Table 1 (Continued)

Characteristics Sample

n (%)

Non-pathological

Internet users

n (%)

Pathological users

n (%)

Duration of Internet use

variables

Mean ± SD

Duration of Internet use

(overall) (hours)

(≥5 hours per day)

7.18 ± 4.37

705 (68.9) 482 (68.4) 223 (31.6)

Duration of Internet use for

study purpose (hours)

(≥3 hours per day)

3.09 ± 2.23

493 (48.2) 347 (70.4) 146 (29.6)

Duration of Internet use for

recreational purpose (hours)

(≥3 hours per day)

4.09 ± 3.30

610 (59.6) 417 (68.4) 193 (31.6)

Duration of Internet use for

pornography purpose

(hours) (past week)

0.55 ± 2.39

201 (19.6) 128 (63.7) 73 (36.3)

Duration of smart phone use

(hours) (≥4 hours per day)

7.72 ± 5.64

739 (72.2)

503 (68.0) 236 (31.9)

Psychosocial factors

Childhood emotional abuse 480 (46.9) 319 (66.5) 161 (33.5)

Childhood physical abuse 410 (40.1) 271 (66.1) 139 (33.9)

Childhood sexual abuse 127 (12.4) 83 (65.4) 44 (34.6)

Self-perceived life satisfaction

Low 190 (18.6) 127 (66.8) 63 (33.2)

Medium 624 (61.0) 440 (70.5) 184 (29.5)

High 209 (20.4) 160 (76.6) 49 (23.4)

Self-perceived academic

performance

Poor 316 (30.9) 207 (65.5) 109 (34.5)

Satisfactory 549 (53.7) 405 (73.8) 144 (26.2)

Excellent 158 (15.4) 115 (72.8) 43 (27.2)

Skipping breakfast

Never 516 (50.4) 383 (74.2) 133 (25.8)

Sometimes 402 (39.1) 271 (67.4) 131 (32.6)

Everyday 105 (10.3) 73 (69.5) 32 (30.5)

Comorbid symptoms

Having gambling problem 55 (25.7) 30 (54.6) 25 (45.4)

Current tobacco use 31 (3.0) 18 (58.1) 13 (41.9)

Harmful alcohol use 20 (10.1) 12 (60.0) 8 (40.0)

Drug use

(Past 12 months)

49 ( 4.8) 27 (55.1) 22 (44.9)

Depression (moderate/severe) 242 (23.7) 130 (53.8) 112 (46.2)

Sleeping problem

(moderate/severe)

680 (66.5) 469 (69.0) 211 (31.0)

PSTD symptoms

(4 or more)

112 (10.9) 56 (50.0) 56 (50.0)

71

Table 1 (Continued)

Characteristics Sample

n (%)

Non-pathological

Internet users

n (%)

Pathological users

n (%)

Duration of Internet use

variables

Mean ± SD

Duration of Internet use

(overall) (hours)

(≥5 hours per day)

7.18 ± 4.37

705 (68.9) 482 (68.4) 223 (31.6)

Duration of Internet use for

study purpose (hours)

(≥3 hours per day)

3.09 ± 2.23

493 (48.2) 347 (70.4) 146 (29.6)

Duration of Internet use for

recreational purpose (hours)

(≥3 hours per day)

4.09 ± 3.30

610 (59.6) 417 (68.4) 193 (31.6)

Duration of Internet use for

pornography purpose

(hours) (past week)

0.55 ± 2.39

201 (19.6) 128 (63.7) 73 (36.3)

Duration of smart phone use

(hours) (≥4 hours per day)

7.72 ± 5.64

739 (72.2)

503 (68.0) 236 (31.9)

Psychosocial factors

Childhood emotional abuse 480 (46.9) 319 (66.5) 161 (33.5)

Childhood physical abuse 410 (40.1) 271 (66.1) 139 (33.9)

Childhood sexual abuse 127 (12.4) 83 (65.4) 44 (34.6)

Self-perceived life satisfaction

Low 190 (18.6) 127 (66.8) 63 (33.2)

Medium 624 (61.0) 440 (70.5) 184 (29.5)

High 209 (20.4) 160 (76.6) 49 (23.4)

Self-perceived academic

performance

Poor 316 (30.9) 207 (65.5) 109 (34.5)

Satisfactory 549 (53.7) 405 (73.8) 144 (26.2)

Excellent 158 (15.4) 115 (72.8) 43 (27.2)

Skipping breakfast

Never 516 (50.4) 383 (74.2) 133 (25.8)

Sometimes 402 (39.1) 271 (67.4) 131 (32.6)

Everyday 105 (10.3) 73 (69.5) 32 (30.5)

Comorbid symptoms

Having gambling problem 55 (25.7) 30 (54.6) 25 (45.4)

Current tobacco use 31 (3.0) 18 (58.1) 13 (41.9)

Harmful alcohol use 20 (10.1) 12 (60.0) 8 (40.0)

Drug use

(Past 12 months)

49 ( 4.8) 27 (55.1) 22 (44.9)

Depression (moderate/severe) 242 (23.7) 130 (53.8) 112 (46.2)

Sleeping problem

(moderate/severe)

680 (66.5) 469 (69.0) 211 (31.0)

PSTD symptoms

(4 or more)

112 (10.9) 56 (50.0) 56 (50.0)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Pathological Internet Use among Undergraduate Students

72

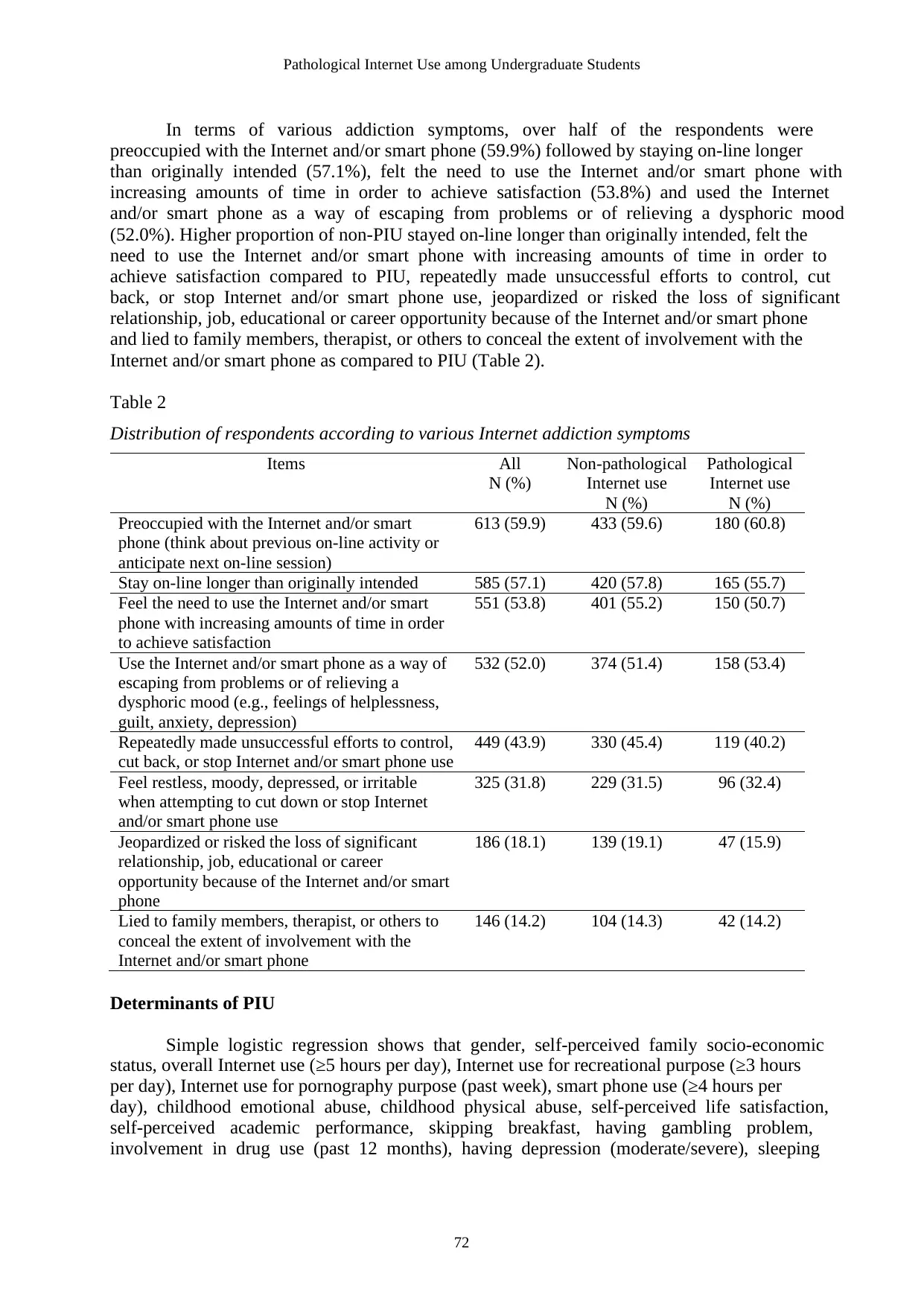

In terms of various addiction symptoms, over half of the respondents were

preoccupied with the Internet and/or smart phone (59.9%) followed by staying on-line longer

than originally intended (57.1%), felt the need to use the Internet and/or smart phone with

increasing amounts of time in order to achieve satisfaction (53.8%) and used the Internet

and/or smart phone as a way of escaping from problems or of relieving a dysphoric mood

(52.0%). Higher proportion of non-PIU stayed on-line longer than originally intended, felt the

need to use the Internet and/or smart phone with increasing amounts of time in order to

achieve satisfaction compared to PIU, repeatedly made unsuccessful efforts to control, cut

back, or stop Internet and/or smart phone use, jeopardized or risked the loss of significant

relationship, job, educational or career opportunity because of the Internet and/or smart phone

and lied to family members, therapist, or others to conceal the extent of involvement with the

Internet and/or smart phone as compared to PIU (Table 2).

Table 2

Distribution of respondents according to various Internet addiction symptoms

Items All

N (%)

Non-pathological

Internet use

N (%)

Pathological

Internet use

N (%)

Preoccupied with the Internet and/or smart

phone (think about previous on-line activity or

anticipate next on-line session)

613 (59.9) 433 (59.6) 180 (60.8)

Stay on-line longer than originally intended 585 (57.1) 420 (57.8) 165 (55.7)

Feel the need to use the Internet and/or smart

phone with increasing amounts of time in order

to achieve satisfaction

551 (53.8) 401 (55.2) 150 (50.7)

Use the Internet and/or smart phone as a way of

escaping from problems or of relieving a

dysphoric mood (e.g., feelings of helplessness,

guilt, anxiety, depression)

532 (52.0) 374 (51.4) 158 (53.4)

Repeatedly made unsuccessful efforts to control,

cut back, or stop Internet and/or smart phone use

449 (43.9) 330 (45.4) 119 (40.2)

Feel restless, moody, depressed, or irritable

when attempting to cut down or stop Internet

and/or smart phone use

325 (31.8) 229 (31.5) 96 (32.4)

Jeopardized or risked the loss of significant

relationship, job, educational or career

opportunity because of the Internet and/or smart

phone

186 (18.1) 139 (19.1) 47 (15.9)

Lied to family members, therapist, or others to

conceal the extent of involvement with the

Internet and/or smart phone

146 (14.2) 104 (14.3) 42 (14.2)

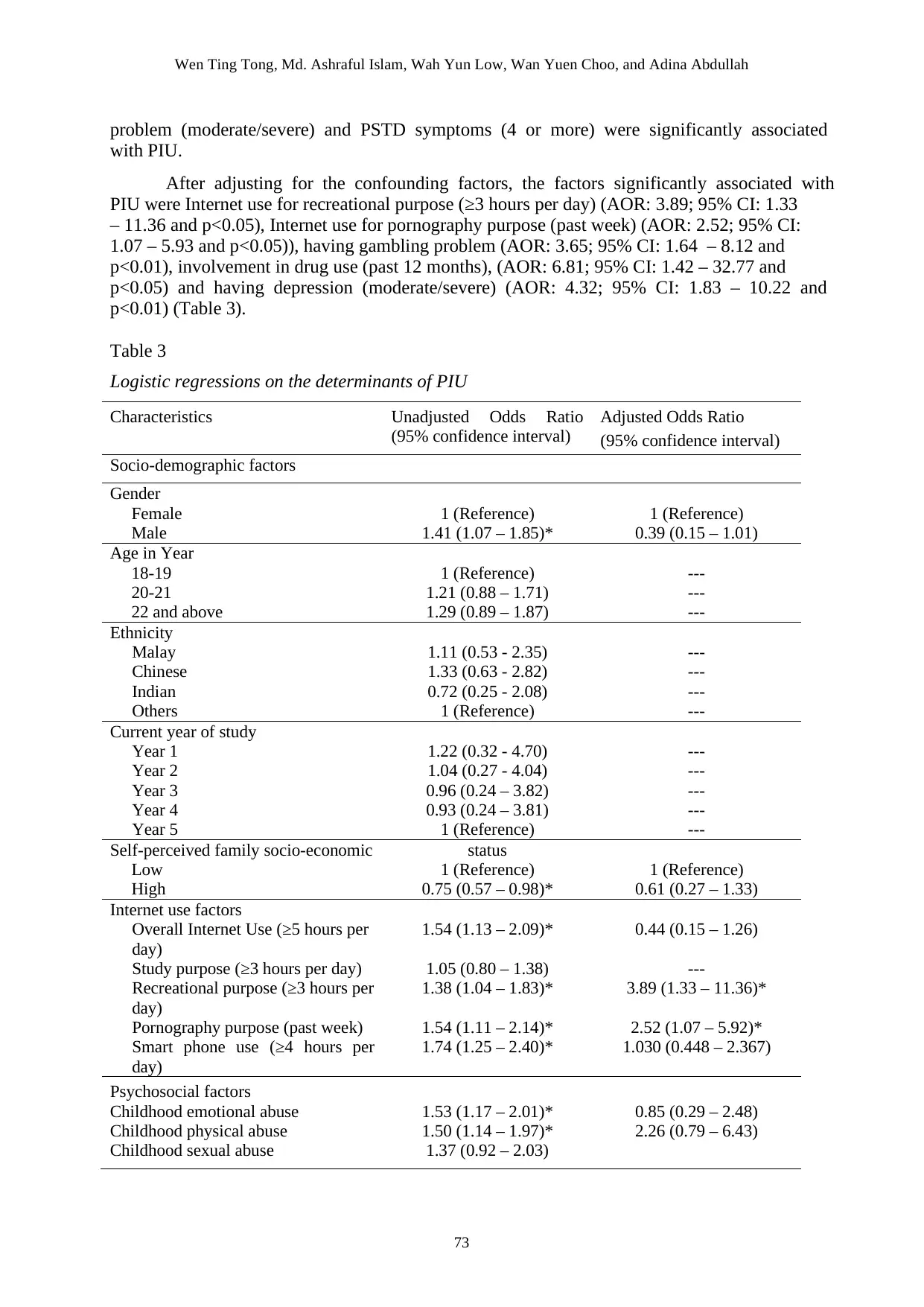

Determinants of PIU

Simple logistic regression shows that gender, self-perceived family socio-economic

status, overall Internet use (≥5 hours per day), Internet use for recreational purpose (≥3 hours

per day), Internet use for pornography purpose (past week), smart phone use (≥4 hours per

day), childhood emotional abuse, childhood physical abuse, self-perceived life satisfaction,

self-perceived academic performance, skipping breakfast, having gambling problem,

involvement in drug use (past 12 months), having depression (moderate/severe), sleeping

72

In terms of various addiction symptoms, over half of the respondents were

preoccupied with the Internet and/or smart phone (59.9%) followed by staying on-line longer

than originally intended (57.1%), felt the need to use the Internet and/or smart phone with

increasing amounts of time in order to achieve satisfaction (53.8%) and used the Internet

and/or smart phone as a way of escaping from problems or of relieving a dysphoric mood

(52.0%). Higher proportion of non-PIU stayed on-line longer than originally intended, felt the

need to use the Internet and/or smart phone with increasing amounts of time in order to

achieve satisfaction compared to PIU, repeatedly made unsuccessful efforts to control, cut

back, or stop Internet and/or smart phone use, jeopardized or risked the loss of significant

relationship, job, educational or career opportunity because of the Internet and/or smart phone

and lied to family members, therapist, or others to conceal the extent of involvement with the

Internet and/or smart phone as compared to PIU (Table 2).

Table 2

Distribution of respondents according to various Internet addiction symptoms

Items All

N (%)

Non-pathological

Internet use

N (%)

Pathological

Internet use

N (%)

Preoccupied with the Internet and/or smart

phone (think about previous on-line activity or

anticipate next on-line session)

613 (59.9) 433 (59.6) 180 (60.8)

Stay on-line longer than originally intended 585 (57.1) 420 (57.8) 165 (55.7)

Feel the need to use the Internet and/or smart

phone with increasing amounts of time in order

to achieve satisfaction

551 (53.8) 401 (55.2) 150 (50.7)

Use the Internet and/or smart phone as a way of

escaping from problems or of relieving a

dysphoric mood (e.g., feelings of helplessness,

guilt, anxiety, depression)

532 (52.0) 374 (51.4) 158 (53.4)

Repeatedly made unsuccessful efforts to control,

cut back, or stop Internet and/or smart phone use

449 (43.9) 330 (45.4) 119 (40.2)

Feel restless, moody, depressed, or irritable

when attempting to cut down or stop Internet

and/or smart phone use

325 (31.8) 229 (31.5) 96 (32.4)

Jeopardized or risked the loss of significant

relationship, job, educational or career

opportunity because of the Internet and/or smart

phone

186 (18.1) 139 (19.1) 47 (15.9)

Lied to family members, therapist, or others to

conceal the extent of involvement with the

Internet and/or smart phone

146 (14.2) 104 (14.3) 42 (14.2)

Determinants of PIU

Simple logistic regression shows that gender, self-perceived family socio-economic

status, overall Internet use (≥5 hours per day), Internet use for recreational purpose (≥3 hours

per day), Internet use for pornography purpose (past week), smart phone use (≥4 hours per

day), childhood emotional abuse, childhood physical abuse, self-perceived life satisfaction,

self-perceived academic performance, skipping breakfast, having gambling problem,

involvement in drug use (past 12 months), having depression (moderate/severe), sleeping

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Wen Ting Tong, Md. Ashraful Islam, Wah Yun Low, Wan Yuen Choo, and Adina Abdullah

73

problem (moderate/severe) and PSTD symptoms (4 or more) were significantly associated

with PIU.

After adjusting for the confounding factors, the factors significantly associated with

PIU were Internet use for recreational purpose (≥3 hours per day) (AOR: 3.89; 95% CI: 1.33

– 11.36 and p<0.05), Internet use for pornography purpose (past week) (AOR: 2.52; 95% CI:

1.07 – 5.93 and p<0.05)), having gambling problem (AOR: 3.65; 95% CI: 1.64 – 8.12 and

p<0.01), involvement in drug use (past 12 months), (AOR: 6.81; 95% CI: 1.42 – 32.77 and

p<0.05) and having depression (moderate/severe) (AOR: 4.32; 95% CI: 1.83 – 10.22 and

p<0.01) (Table 3).

Table 3

Logistic regressions on the determinants of PIU

Characteristics Unadjusted Odds Ratio

(95% confidence interval)

Adjusted Odds Ratio

(95% confidence interval)

Socio-demographic factors

Gender

Female 1 (Reference) 1 (Reference)

Male 1.41 (1.07 – 1.85)* 0.39 (0.15 – 1.01)

Age in Year

18-19 1 (Reference) ---

20-21 1.21 (0.88 – 1.71) ---

22 and above 1.29 (0.89 – 1.87) ---

Ethnicity

Malay 1.11 (0.53 - 2.35) ---

Chinese 1.33 (0.63 - 2.82) ---

Indian 0.72 (0.25 - 2.08) ---

Others 1 (Reference) ---

Current year of study

Year 1 1.22 (0.32 - 4.70) ---

Year 2 1.04 (0.27 - 4.04) ---

Year 3 0.96 (0.24 – 3.82) ---

Year 4 0.93 (0.24 – 3.81) ---

Year 5 1 (Reference) ---

Self-perceived family socio-economic status

Low 1 (Reference) 1 (Reference)

High 0.75 (0.57 – 0.98)* 0.61 (0.27 – 1.33)

Internet use factors

Overall Internet Use (≥5 hours per

day)

1.54 (1.13 – 2.09)* 0.44 (0.15 – 1.26)

Study purpose (≥3 hours per day) 1.05 (0.80 – 1.38) ---

Recreational purpose (≥3 hours per

day)

1.38 (1.04 – 1.83)* 3.89 (1.33 – 11.36)*

Pornography purpose (past week) 1.54 (1.11 – 2.14)* 2.52 (1.07 – 5.92)*

Smart phone use (≥4 hours per

day)

1.74 (1.25 – 2.40)* 1.030 (0.448 – 2.367)

Psychosocial factors

Childhood emotional abuse 1.53 (1.17 – 2.01)* 0.85 (0.29 – 2.48)

Childhood physical abuse 1.50 (1.14 – 1.97)* 2.26 (0.79 – 6.43)

Childhood sexual abuse 1.37 (0.92 – 2.03)

73

problem (moderate/severe) and PSTD symptoms (4 or more) were significantly associated

with PIU.

After adjusting for the confounding factors, the factors significantly associated with

PIU were Internet use for recreational purpose (≥3 hours per day) (AOR: 3.89; 95% CI: 1.33

– 11.36 and p<0.05), Internet use for pornography purpose (past week) (AOR: 2.52; 95% CI:

1.07 – 5.93 and p<0.05)), having gambling problem (AOR: 3.65; 95% CI: 1.64 – 8.12 and

p<0.01), involvement in drug use (past 12 months), (AOR: 6.81; 95% CI: 1.42 – 32.77 and

p<0.05) and having depression (moderate/severe) (AOR: 4.32; 95% CI: 1.83 – 10.22 and

p<0.01) (Table 3).

Table 3

Logistic regressions on the determinants of PIU

Characteristics Unadjusted Odds Ratio

(95% confidence interval)

Adjusted Odds Ratio

(95% confidence interval)

Socio-demographic factors

Gender

Female 1 (Reference) 1 (Reference)

Male 1.41 (1.07 – 1.85)* 0.39 (0.15 – 1.01)

Age in Year

18-19 1 (Reference) ---

20-21 1.21 (0.88 – 1.71) ---

22 and above 1.29 (0.89 – 1.87) ---

Ethnicity

Malay 1.11 (0.53 - 2.35) ---

Chinese 1.33 (0.63 - 2.82) ---

Indian 0.72 (0.25 - 2.08) ---

Others 1 (Reference) ---

Current year of study

Year 1 1.22 (0.32 - 4.70) ---

Year 2 1.04 (0.27 - 4.04) ---

Year 3 0.96 (0.24 – 3.82) ---

Year 4 0.93 (0.24 – 3.81) ---

Year 5 1 (Reference) ---

Self-perceived family socio-economic status

Low 1 (Reference) 1 (Reference)

High 0.75 (0.57 – 0.98)* 0.61 (0.27 – 1.33)

Internet use factors

Overall Internet Use (≥5 hours per

day)

1.54 (1.13 – 2.09)* 0.44 (0.15 – 1.26)

Study purpose (≥3 hours per day) 1.05 (0.80 – 1.38) ---

Recreational purpose (≥3 hours per

day)

1.38 (1.04 – 1.83)* 3.89 (1.33 – 11.36)*

Pornography purpose (past week) 1.54 (1.11 – 2.14)* 2.52 (1.07 – 5.92)*

Smart phone use (≥4 hours per

day)

1.74 (1.25 – 2.40)* 1.030 (0.448 – 2.367)

Psychosocial factors

Childhood emotional abuse 1.53 (1.17 – 2.01)* 0.85 (0.29 – 2.48)

Childhood physical abuse 1.50 (1.14 – 1.97)* 2.26 (0.79 – 6.43)

Childhood sexual abuse 1.37 (0.92 – 2.03)

Pathological Internet Use among Undergraduate Students

74

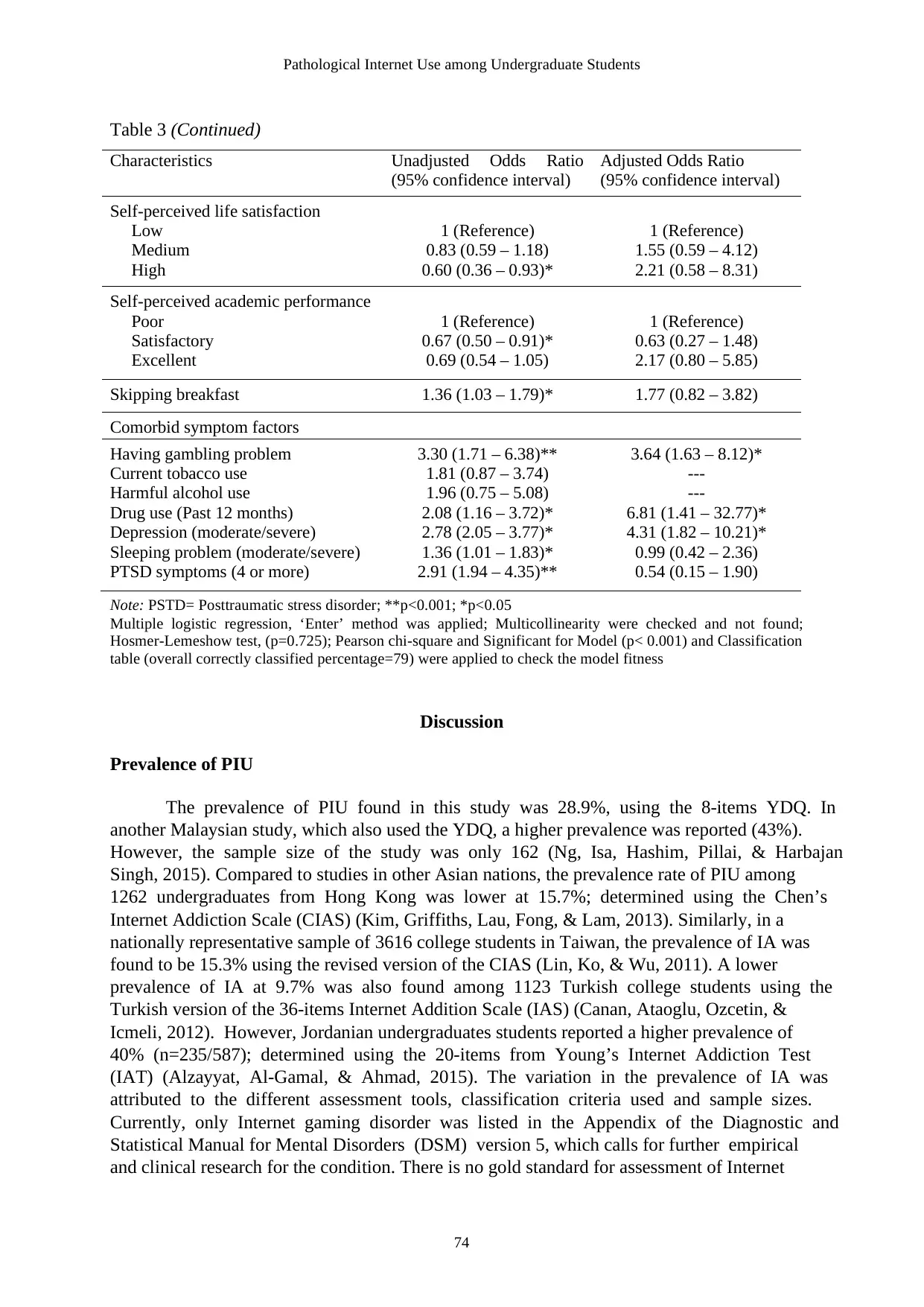

Table 3 (Continued)

Characteristics Unadjusted Odds Ratio

(95% confidence interval)

Adjusted Odds Ratio

(95% confidence interval)

Self-perceived life satisfaction

Low 1 (Reference) 1 (Reference)

Medium 0.83 (0.59 – 1.18) 1.55 (0.59 – 4.12)

High 0.60 (0.36 – 0.93)* 2.21 (0.58 – 8.31)

Self-perceived academic performance

Poor 1 (Reference) 1 (Reference)

Satisfactory 0.67 (0.50 – 0.91)* 0.63 (0.27 – 1.48)

Excellent 0.69 (0.54 – 1.05) 2.17 (0.80 – 5.85)

Skipping breakfast 1.36 (1.03 – 1.79)* 1.77 (0.82 – 3.82)

Comorbid symptom factors

Having gambling problem 3.30 (1.71 – 6.38)** 3.64 (1.63 – 8.12)*

Current tobacco use 1.81 (0.87 – 3.74) ---

Harmful alcohol use 1.96 (0.75 – 5.08) ---

Drug use (Past 12 months) 2.08 (1.16 – 3.72)* 6.81 (1.41 – 32.77)*

Depression (moderate/severe) 2.78 (2.05 – 3.77)* 4.31 (1.82 – 10.21)*

Sleeping problem (moderate/severe) 1.36 (1.01 – 1.83)* 0.99 (0.42 – 2.36)

PTSD symptoms (4 or more) 2.91 (1.94 – 4.35)** 0.54 (0.15 – 1.90)

Note: PSTD= Posttraumatic stress disorder; **p<0.001; *p<0.05

Multiple logistic regression, ‘Enter’ method was applied; Multicollinearity were checked and not found;

Hosmer-Lemeshow test, (p=0.725); Pearson chi-square and Significant for Model (p< 0.001) and Classification