Psychosocial Characteristics and Vaccine Attitudes in Australia Report

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/14

|8

|9374

|17

Report

AI Summary

This research report, based on a survey of 4370 Australians, investigates the relationship between vaccine attitudes and various psychosocial and demographic characteristics. The study categorizes participants into five vaccine attitude groups and analyzes how these groups differ in terms of health consumer behavior, trust in the healthcare system, adherence to complementary medicine, conspiracist ideation, political preferences, and demographic factors like gender and religious beliefs. The findings reveal that individuals with negative vaccine attitudes tend to be more informed health consumers, distrustful of the mainstream healthcare system, and more likely to hold conspiratorial beliefs. The research highlights the importance of understanding these psychosocial profiles to tailor communication strategies about vaccination and potentially refine the measurement and classification of vaccine attitudes. The study emphasizes the context-specific nature of vaccine attitudes and the need for granular analysis of hesitancy within the broader spectrum of vaccine acceptance and refusal. This report is a valuable resource for public health professionals and anyone interested in understanding the complexities of vaccine attitudes in Australia.

Psychosocialand demographiccharacteristicsrelating to vaccine

attitudes in Australia

TomasRozbroja,

*, Anthony Lyonsa

, Jayne Luckea,b

aAustralianResearchCentrein Sex,Healthand Society,La TrobeUniversity,Australia

b Schoolof PublicHealth,The Universityof Queensland,Australia

A R T I C L E I N F O

Articlehistory:

Received30 April 2018

Receivedin revised form 13 August 2018

Accepted21 August 2018

Keywords:

Vaccine hesitancy

Vaccine attitude

Vaccine refusal

Vaccine acceptance

Anti-vaccination

Community level

A B S T R A C T

Objective:Distrust in vaccinationis a public health concern.In respondingto vaccinationdistrust, the

psychosocialcontextit occursin needsto be accountedfor. But this psychosocialcontextis insufficiently

understood. We examined how Australians’ attitudes to childhood vaccination relate to broader

psychosocialcharacteristicspertaining to two key areas: health and government.

Design:4370Australianswere surveyedand divided into five vaccineattitudegroups.Logisticunivariable

and multivariableregressionanalyseswere used to comparedifferencesin psychosocialcharacteristics

between these groups.

Results:Multivariate analysisshowed that, comparedto groups with positive vaccineattitudes,groups

with negativeattitudeswere more informed,engagedand independenthealth consumers,with greater

adherenceto complementarymedicine,but lower belief in holistic health.Theyhad higher distrust in the

mainstreamhealthcaresystem,higher conspiracistideation, and were more likely to vote for minor

political parties.They were more likely to be male,religious,havechildren,and self-reportbetterhealth.

Conclusions:This researchrevealedHOW profilesof psychosocialcharacteristicsdifferedbetweeneachof

the five attitudes to childhood vaccines.

Practiceimplications:These findings are useful for tailoring communicationsabout vaccination-related

concerns.Theyalso show that more granularclassificationand measurementof vaccineattitudesmay be

useful.

© 2018 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Lack of confidencein vaccinationis a concern in Australia [1]

and around the world [2]. Although vaccinationrates in Australia

are high, they are below national targets [3]. Under-vaccinated

people are unevenly distributed, increasing risk of disease

transmission [4,5]. Vaccine-preventabledisease outbreaks and

deaths continue to occur [6]. Confidencein vaccinesis low; in a

2017 study, only 48% of Australian parents reported having no

concernsabout vaccines,while over a fifth believedthat vaccines

causeautism[7]. Other countriesare facingsimilar problems,with

low confidencein many Europeanand North American countries

[8], and vaccine-preventabledeaths continuing to occur despite

good access to vaccination [9–11]. Increasing confidence in

vaccineswill boost vaccineuptake [12–14],but there is a paucity

of effectivestrategiesto do so [15–18].

To help increase confidence, a better understandingof the

relationshipbetween vaccineattitudesand broaderdemographic

and psychosocialattributes within which they exist is needed

[2,15,18].Understandingthe relationship between vaccine atti-

tudes and psychosocial attributes related to healthcare and

governmentis particularlyimportant,becausevaccineconfidence

is linked to beliefs about health [12,17,19,20]and government

[12,21,22],and healthcareand governmentbodies are central to

promoting,delivering and regulatingvaccination.

Existing researchshows that vaccineattitudes exist as part of

psychosocialand demographicattributes[21,23,24].In Australia,

demographicattributeslike socioeconomicstatus(SES)and access

to services [5,7,8,25,26] are linked to vaccine confidence.

Psychosocialfactors related to health, like trust in healthcare

providers,predict vaccineuptake in Australia [27] and elsewhere

[17,28,29].Accessingalternativemedicalpractitionersand greater

relianceon the internetfor health informationare associatedwith

Abbreviations:CAM, complementaryand alternativemedicine; CI, confidence

interval;CMQ, conspiracistmentalityquestionnaire;HCAMQ, holistic complemen-

tary and alternativehealth questionnaire;HCSDS-R, healthcaresystem distrust

scale- revised;HH, holistic health; PSAS,patientself-advocacyscale;RR, risk ratio;

SES,socioeconomicstatus; WHO, World Health Organisation.

* Correspondingauthorat: AustralianResearchCentrein Sex,Health and Society,

La Trobe University,Building NR6, Bundoora,Victoria, 3086, Australia.

E-mail address:t.rozbroj@latrobe.edu.au(T. Rozbroj).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.027

0738-3991/©2018 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Patient Educationand Counselingxxx (2018)xxx–xxx

G Model

PEC 6049No. of Pages8

Pleasecite this article in press as: T. Rozbroj, et al., Psychosocialand demographiccharacteristicsrelating to vaccineattitudes in Australia,

Patient Educ Couns (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.027

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Patient Educationand Counseling

j o u r n a lhomep age: w w w . e l s ev i er . c o m / l o c a t e/ p a t e d u c o u

attitudes in Australia

TomasRozbroja,

*, Anthony Lyonsa

, Jayne Luckea,b

aAustralianResearchCentrein Sex,Healthand Society,La TrobeUniversity,Australia

b Schoolof PublicHealth,The Universityof Queensland,Australia

A R T I C L E I N F O

Articlehistory:

Received30 April 2018

Receivedin revised form 13 August 2018

Accepted21 August 2018

Keywords:

Vaccine hesitancy

Vaccine attitude

Vaccine refusal

Vaccine acceptance

Anti-vaccination

Community level

A B S T R A C T

Objective:Distrust in vaccinationis a public health concern.In respondingto vaccinationdistrust, the

psychosocialcontextit occursin needsto be accountedfor. But this psychosocialcontextis insufficiently

understood. We examined how Australians’ attitudes to childhood vaccination relate to broader

psychosocialcharacteristicspertaining to two key areas: health and government.

Design:4370Australianswere surveyedand divided into five vaccineattitudegroups.Logisticunivariable

and multivariableregressionanalyseswere used to comparedifferencesin psychosocialcharacteristics

between these groups.

Results:Multivariate analysisshowed that, comparedto groups with positive vaccineattitudes,groups

with negativeattitudeswere more informed,engagedand independenthealth consumers,with greater

adherenceto complementarymedicine,but lower belief in holistic health.Theyhad higher distrust in the

mainstreamhealthcaresystem,higher conspiracistideation, and were more likely to vote for minor

political parties.They were more likely to be male,religious,havechildren,and self-reportbetterhealth.

Conclusions:This researchrevealedHOW profilesof psychosocialcharacteristicsdifferedbetweeneachof

the five attitudes to childhood vaccines.

Practiceimplications:These findings are useful for tailoring communicationsabout vaccination-related

concerns.Theyalso show that more granularclassificationand measurementof vaccineattitudesmay be

useful.

© 2018 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Lack of confidencein vaccinationis a concern in Australia [1]

and around the world [2]. Although vaccinationrates in Australia

are high, they are below national targets [3]. Under-vaccinated

people are unevenly distributed, increasing risk of disease

transmission [4,5]. Vaccine-preventabledisease outbreaks and

deaths continue to occur [6]. Confidencein vaccinesis low; in a

2017 study, only 48% of Australian parents reported having no

concernsabout vaccines,while over a fifth believedthat vaccines

causeautism[7]. Other countriesare facingsimilar problems,with

low confidencein many Europeanand North American countries

[8], and vaccine-preventabledeaths continuing to occur despite

good access to vaccination [9–11]. Increasing confidence in

vaccineswill boost vaccineuptake [12–14],but there is a paucity

of effectivestrategiesto do so [15–18].

To help increase confidence, a better understandingof the

relationshipbetween vaccineattitudesand broaderdemographic

and psychosocialattributes within which they exist is needed

[2,15,18].Understandingthe relationship between vaccine atti-

tudes and psychosocial attributes related to healthcare and

governmentis particularlyimportant,becausevaccineconfidence

is linked to beliefs about health [12,17,19,20]and government

[12,21,22],and healthcareand governmentbodies are central to

promoting,delivering and regulatingvaccination.

Existing researchshows that vaccineattitudes exist as part of

psychosocialand demographicattributes[21,23,24].In Australia,

demographicattributeslike socioeconomicstatus(SES)and access

to services [5,7,8,25,26] are linked to vaccine confidence.

Psychosocialfactors related to health, like trust in healthcare

providers,predict vaccineuptake in Australia [27] and elsewhere

[17,28,29].Accessingalternativemedicalpractitionersand greater

relianceon the internetfor health informationare associatedwith

Abbreviations:CAM, complementaryand alternativemedicine; CI, confidence

interval;CMQ, conspiracistmentalityquestionnaire;HCAMQ, holistic complemen-

tary and alternativehealth questionnaire;HCSDS-R, healthcaresystem distrust

scale- revised;HH, holistic health; PSAS,patientself-advocacyscale;RR, risk ratio;

SES,socioeconomicstatus; WHO, World Health Organisation.

* Correspondingauthorat: AustralianResearchCentrein Sex,Health and Society,

La Trobe University,Building NR6, Bundoora,Victoria, 3086, Australia.

E-mail address:t.rozbroj@latrobe.edu.au(T. Rozbroj).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.027

0738-3991/©2018 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Patient Educationand Counselingxxx (2018)xxx–xxx

G Model

PEC 6049No. of Pages8

Pleasecite this article in press as: T. Rozbroj, et al., Psychosocialand demographiccharacteristicsrelating to vaccineattitudes in Australia,

Patient Educ Couns (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.027

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Patient Educationand Counseling

j o u r n a lhomep age: w w w . e l s ev i er . c o m / l o c a t e/ p a t e d u c o u

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

higher distrust in vaccines [7,19,30–33].Psychosocial factors

related to governmentalso predict vaccine confidence.A study

of 24 countries, including Australia, found that antivaccination

attitudes are associatedwith conspiratorialbeliefs and individu-

alist world views [23]. Research from outside the Australian

context has shown that vaccine confidence is associatedwith

trust in government[21,34],culture and values[35,36]and world

views [37].

Important gaps persist in knowledge about how Australians’

attitudes to vaccination relate to psychosocial characteristics

pertaining to healthcare and government.Overseasstudies are

problematic to apply to Australia, because the relationships

between vaccine attitudes and broader attributes are context-

specific [2,38–40]. While it is known that in Australia vaccine

attitudes relate to trust in healthcareproviders, little is known

about how they relate to health decision-making,health educa-

tion, and beliefs about the healthcare system, which may all

influence attitudes. Furthermore, little is known about how

vaccine attitudes in Australia relate to trust in governmentor

political orientations, despite both potentially being important

[21]. Few Australian studies have directly evaluatedhow people

across the spectrum of vaccine attitudes compare in broader

attributes related to either governmentor health, limiting the

extent to which intergroup differencescan be assessed.

The taxonomyand measurementof vaccineattitudes present

further challenges.The prevailing taxonomy,developed by the

World Health Organization (WHO), divides the spectrum of

attitudes into three categories:i) full acceptanceon one end, iii)

full refusal on the other, and ii) vaccine hesitancy in-between

[2,18,41].The hesitancy category is heterogeneous,comprising

those who accept vaccineswith some doubts, those who refuse

almostall vaccines,and all between[2,38].‘Hesitancy’is treatedas

a distinct entity in research [38], measurement [2,42] and

intervention design [18]. But hesitancy is an ambiguous“catch-

all category”, which potentially lumps together contrasting

attributes [43]. A more sensitive measurement of ‘hesitancy’,

which takesaccountof subgroupswithin this broadcategory,may

expose important differences. The prevailing taxonomy also

conflatesbehaviourwith attitude.For example,one point on the

spectrumis “acceptbut unsure”: acceptancereferring to uptake,

level of surenessbeing attitude [2]. But studiesconsistentlyshow

that uptakedoes not correspondto acceptance[7,12,25,27,35,44–

46], so a taxonomy focusing on attitude alone is needed for

researchinto vaccineattitudes.

The aim of this paper was to investigatehow Australianadults’

demographicattributesand psychosocialattributespertaining to

health and government compare among five vaccine attitude

groups, ranging from unwavering support to rejection of all

vaccines.

2. Methods

2.1.Designand sample

We analyseddata collected as part of the Australian Vaccine

Attitudes Survey.The online survey sampled adults (18+)living

acrossAustralia.A conveniencesampleof at least 250 participants

for eachattitudegroup was sought,to enablestatisticalanalysisat

95%CI. Participantswere recruitedbetweenJanuaryand May 2017

by distributinga genericlink to the surveyvia Facebookadverts,e-

newsletters/magazines,and posts on webpagesrelatedto parent-

hood and wellbeing. One Facebookadvert was targetedtowards

people who reject vaccines (approximately 2% of Australians

[7,25]) to boost participation from this group. The survey was

anonymous,and no reminderswere sent to encouragecompletion.

No incentives were offered to encourage participation. Ethics

approval was granted by the La Trobe University Human Ethics

Committee (ref: S16-208). The final sample comprised 4370

respondents.

2.2.Measures

We measured vaccine attitude, demographicattributes, and

psychosocial attributes relating to: i) relationship with the

healthcaresystem,which concernedhow respondentsconsume

health, and ii) relationship with government,which concerned

voting behaviourand trust in government.All study variablesare

listed in Table 2 and explainedin detail below.

2.2.1.Vaccineattitude

Table1 shows the questionused to measurevaccineattitudeas

a categorical variable, and the category labels used. Vaccine

attitude was also measured as a continuous variable, using a

validatedVaccinationScale,which measuresthe extent to which

attitudes are supportive of vaccination[47]. The six-point Likert

scalecomprisesfive items.Scalescorescan rangebetween1 and 6,

with high scores indicating supportive attitudes.This scale was

used to gauge the reliability of the categoricalvaccine attitude

variable.

2.2.2.Demographicprofile

Demographicmeasuresincluded: i) age,codedas 18–29/30–49

/50+; ii) gender,coded as male/female; iii) state or territory in

which participants lived; iv) remotenessof residence,coded as

urban/rural/regional;v) whether respondentshave children; vi)

education,coded as whether university educationwas attained,

vii) income, coded as above/below median weekly personal

income; and viii) perceivedhealth, measuredusing the General

Self-RatedHealth scale: a validated single-item 5-point scale of

Table 1

Vaccineattitude questionwording and categorylabels.

Original Question Outcome variable

category labels

Which of the followingbestdescribesyour attitudeto vaccination?

All recommendedchildhood vaccinesshould be administeredto all eligible children. I have no concernsabout them. All, unconcerned

All recommendedchildhood vaccinesshould be administeredto all eligible children. However,I have some concernsabout them. All, concerned

Most of the recommendedchildhood vaccinesshould be administeredto eligible children, but not in all casesand/or not for all the vaccines

on the schedule.

Most

Some recommendedchildhood vaccinesshould be administeredto eligible children, but not in most casesand/or not for the majority of the

vaccineson the schedule.

Some

None of the recommendedchildhood vaccinesshould be administeredto children. None

2 T. Rozbrojet al. / PatientEducationand Counselingxxx (2018)xxx–xxx

G Model

PEC 6049No. of Pages8

Pleasecite this article in press as: T. Rozbroj, et al., Psychosocialand demographiccharacteristicsrelating to vaccineattitudes in Australia,

Patient Educ Couns (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.027

related to governmentalso predict vaccine confidence.A study

of 24 countries, including Australia, found that antivaccination

attitudes are associatedwith conspiratorialbeliefs and individu-

alist world views [23]. Research from outside the Australian

context has shown that vaccine confidence is associatedwith

trust in government[21,34],culture and values[35,36]and world

views [37].

Important gaps persist in knowledge about how Australians’

attitudes to vaccination relate to psychosocial characteristics

pertaining to healthcare and government.Overseasstudies are

problematic to apply to Australia, because the relationships

between vaccine attitudes and broader attributes are context-

specific [2,38–40]. While it is known that in Australia vaccine

attitudes relate to trust in healthcareproviders, little is known

about how they relate to health decision-making,health educa-

tion, and beliefs about the healthcare system, which may all

influence attitudes. Furthermore, little is known about how

vaccine attitudes in Australia relate to trust in governmentor

political orientations, despite both potentially being important

[21]. Few Australian studies have directly evaluatedhow people

across the spectrum of vaccine attitudes compare in broader

attributes related to either governmentor health, limiting the

extent to which intergroup differencescan be assessed.

The taxonomyand measurementof vaccineattitudes present

further challenges.The prevailing taxonomy,developed by the

World Health Organization (WHO), divides the spectrum of

attitudes into three categories:i) full acceptanceon one end, iii)

full refusal on the other, and ii) vaccine hesitancy in-between

[2,18,41].The hesitancy category is heterogeneous,comprising

those who accept vaccineswith some doubts, those who refuse

almostall vaccines,and all between[2,38].‘Hesitancy’is treatedas

a distinct entity in research [38], measurement [2,42] and

intervention design [18]. But hesitancy is an ambiguous“catch-

all category”, which potentially lumps together contrasting

attributes [43]. A more sensitive measurement of ‘hesitancy’,

which takesaccountof subgroupswithin this broadcategory,may

expose important differences. The prevailing taxonomy also

conflatesbehaviourwith attitude.For example,one point on the

spectrumis “acceptbut unsure”: acceptancereferring to uptake,

level of surenessbeing attitude [2]. But studiesconsistentlyshow

that uptakedoes not correspondto acceptance[7,12,25,27,35,44–

46], so a taxonomy focusing on attitude alone is needed for

researchinto vaccineattitudes.

The aim of this paper was to investigatehow Australianadults’

demographicattributesand psychosocialattributespertaining to

health and government compare among five vaccine attitude

groups, ranging from unwavering support to rejection of all

vaccines.

2. Methods

2.1.Designand sample

We analyseddata collected as part of the Australian Vaccine

Attitudes Survey.The online survey sampled adults (18+)living

acrossAustralia.A conveniencesampleof at least 250 participants

for eachattitudegroup was sought,to enablestatisticalanalysisat

95%CI. Participantswere recruitedbetweenJanuaryand May 2017

by distributinga genericlink to the surveyvia Facebookadverts,e-

newsletters/magazines,and posts on webpagesrelatedto parent-

hood and wellbeing. One Facebookadvert was targetedtowards

people who reject vaccines (approximately 2% of Australians

[7,25]) to boost participation from this group. The survey was

anonymous,and no reminderswere sent to encouragecompletion.

No incentives were offered to encourage participation. Ethics

approval was granted by the La Trobe University Human Ethics

Committee (ref: S16-208). The final sample comprised 4370

respondents.

2.2.Measures

We measured vaccine attitude, demographicattributes, and

psychosocial attributes relating to: i) relationship with the

healthcaresystem,which concernedhow respondentsconsume

health, and ii) relationship with government,which concerned

voting behaviourand trust in government.All study variablesare

listed in Table 2 and explainedin detail below.

2.2.1.Vaccineattitude

Table1 shows the questionused to measurevaccineattitudeas

a categorical variable, and the category labels used. Vaccine

attitude was also measured as a continuous variable, using a

validatedVaccinationScale,which measuresthe extent to which

attitudes are supportive of vaccination[47]. The six-point Likert

scalecomprisesfive items.Scalescorescan rangebetween1 and 6,

with high scores indicating supportive attitudes.This scale was

used to gauge the reliability of the categoricalvaccine attitude

variable.

2.2.2.Demographicprofile

Demographicmeasuresincluded: i) age,codedas 18–29/30–49

/50+; ii) gender,coded as male/female; iii) state or territory in

which participants lived; iv) remotenessof residence,coded as

urban/rural/regional;v) whether respondentshave children; vi)

education,coded as whether university educationwas attained,

vii) income, coded as above/below median weekly personal

income; and viii) perceivedhealth, measuredusing the General

Self-RatedHealth scale: a validated single-item 5-point scale of

Table 1

Vaccineattitude questionwording and categorylabels.

Original Question Outcome variable

category labels

Which of the followingbestdescribesyour attitudeto vaccination?

All recommendedchildhood vaccinesshould be administeredto all eligible children. I have no concernsabout them. All, unconcerned

All recommendedchildhood vaccinesshould be administeredto all eligible children. However,I have some concernsabout them. All, concerned

Most of the recommendedchildhood vaccinesshould be administeredto eligible children, but not in all casesand/or not for all the vaccines

on the schedule.

Most

Some recommendedchildhood vaccinesshould be administeredto eligible children, but not in most casesand/or not for the majority of the

vaccineson the schedule.

Some

None of the recommendedchildhood vaccinesshould be administeredto children. None

2 T. Rozbrojet al. / PatientEducationand Counselingxxx (2018)xxx–xxx

G Model

PEC 6049No. of Pages8

Pleasecite this article in press as: T. Rozbroj, et al., Psychosocialand demographiccharacteristicsrelating to vaccineattitudes in Australia,

Patient Educ Couns (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.027

self-reportedoverall health. Possiblescoresrangedbetween 1–5,

with 1 indicating “poor health” and 5 indicating “excellent

health” [48].

2.2.3.Relationshipwith healthcaresystem

Relationship with the healthcaresystem was assessedusing

eight measures, covering trust in mainstream and alternative

healthcaresystems,and confidence/involvementin health deci-

sion-making.

Trust in the healthcaresystemwas measuredusing the Revised

Health Care System Distrust Scale (HCSDS-R) [49] on two

dimensions: i) values, comprising five items measuring trust in

the healthcare system’s honesty, motives and equity; and ii)

competence, comprising four items measuring trust in the

competencyof the healthcare system. Answers were provided

on a 5-point Likert scale. Possible score ranges were 5–25 for

values and 4–20 for competence.Higher scores indicate higher

distrust.

Attitudes to alternative medicine were measured using the

Holistic Complementaryand Alternative Health Questionnaire

(HCAMQ) [50] across two dimensions: i) holistic health (HH),

comprisingfive items measuringbelief that health and wellbeing

rely on treating the body holistically; and ii) complementaryand

alternativemedicine(CAM), comprisingsix items measuringbelief

in the scientificvalidity of CAM. Answers were providedon a six-

point Likert scale.Possiblescorerangeswere 5–30 for HH and 6–36

for CAM. Higher scoresindicate greaterbelief in CAM/HH.

Health decision-making was measured using two scales

assessing patient involvement in their health decisions and

confidencein their health decision-makingability. Confidencein

health decision-makingability was measured using the single-

dimensional Decision Self-EfficacyScale [51], which contains 11

items on a five-point Likert scale.Scorescould range between 0-

100.Patientinvolvementin healthdecision-makingwas measured

using the Patient Self-AdvocacyScale(PSAS)[52], which has three

subscales,each comprising four items measured on a 5-point

Likert scale measuringpatients’:i) illness and treatmenteduca-

tion; ii) assertivenessin health decisionmaking; and iii) potential

for non-adherenceto recommendedtreatments.Subscalescores

could range between 1-5. Higher scores indicate greater confi-

dence/involvementin health decision-making.

2.2.4.Relationshipwith government

Relationship with the governmentwas assessedusing three

measures,coveringtrust in government,conspiracistideation and

voter preference.Trust in governmentwas measuredby a single

questiondevelopedby PEW research[53], with possiblescoresof

1-5. High scores indicate high trust. The Conspiracy Mentality

Questionnaire(CMQ) measureddifferencesin the generictenden-

cy for conspiracistideation[54].It containsfive items measuredon

an 11-point scale,with possiblescoresbetween0–10. High scores

indicate high conspiracist ideation. Voter preferencewas mea-

sured by a non-standardisedquestionaskingwhich political party

respondentsvoted for in the last Federalelection,coded as ‘voted

for: major/minor party’.

2.3.Analysis

Descriptivestatisticswere calculatedfor the sample i) overall,

and ii) cross-tabulatedby five vaccine attitudes.Validity of the

categorical vaccine attitude variable was checked using linear

regression,comparingvaccineattitude categorieswith scoreson

the VaccinationScale.Multinomial logistic regressionwas used to

test the extent to which vaccine attitude was predicted by

demographic and psychosocial attributes. The ‘most’ attitude

was assignedthe referencecategory,becausewe were particularly

interested in differences between the three ‘hesitant’ groups.

Univariableregressionswere first conductedfor eachdemographic

and psychosocialvariable.A single multivariable regressionwas

then conducted.Only predictors that were associatedwith the

outcome variable at p < 0.25 in the univariableregressionswere

entered into the multivariable regression.Respondentswho did

not respond on all variablesunder analysis were excludedfrom

multivariableregression,which was conductedwith a sample of

3471.Risk ratios (RR) and 95%confidenceintervals (95%CI) were

calculated,and a Wald test was used to assessthe overall effectof

each predictor variable.Associationsat p < 0.05 were considered

significant.

3. Results

3.1.Preliminaryanalysis

To gaugethe reliability of the five categorymeasureof vaccine

attitude,linear regressionwas usedto comparethe categorieswith

scoreson the VaccinationScale[47].The scalescoressignificantly

differed in the expected direction across the five categories(F

[4,4365]=7319.74,p < 0.001).With the ‘most’categoryas the base,

the coefficients were β =1.69 (p < 0.001) for ‘all unconcerned’,

β =1.27(p < 0.001)for ‘all concerned’,β=-1.83(p < 0.001)for ‘some’,

and β=-2.44(p < 0.001)for ‘none’.This suggeststhat the categorical

outcome variable served as an accurate indicator of vaccine

attitude.

3.2.Sampleprofile

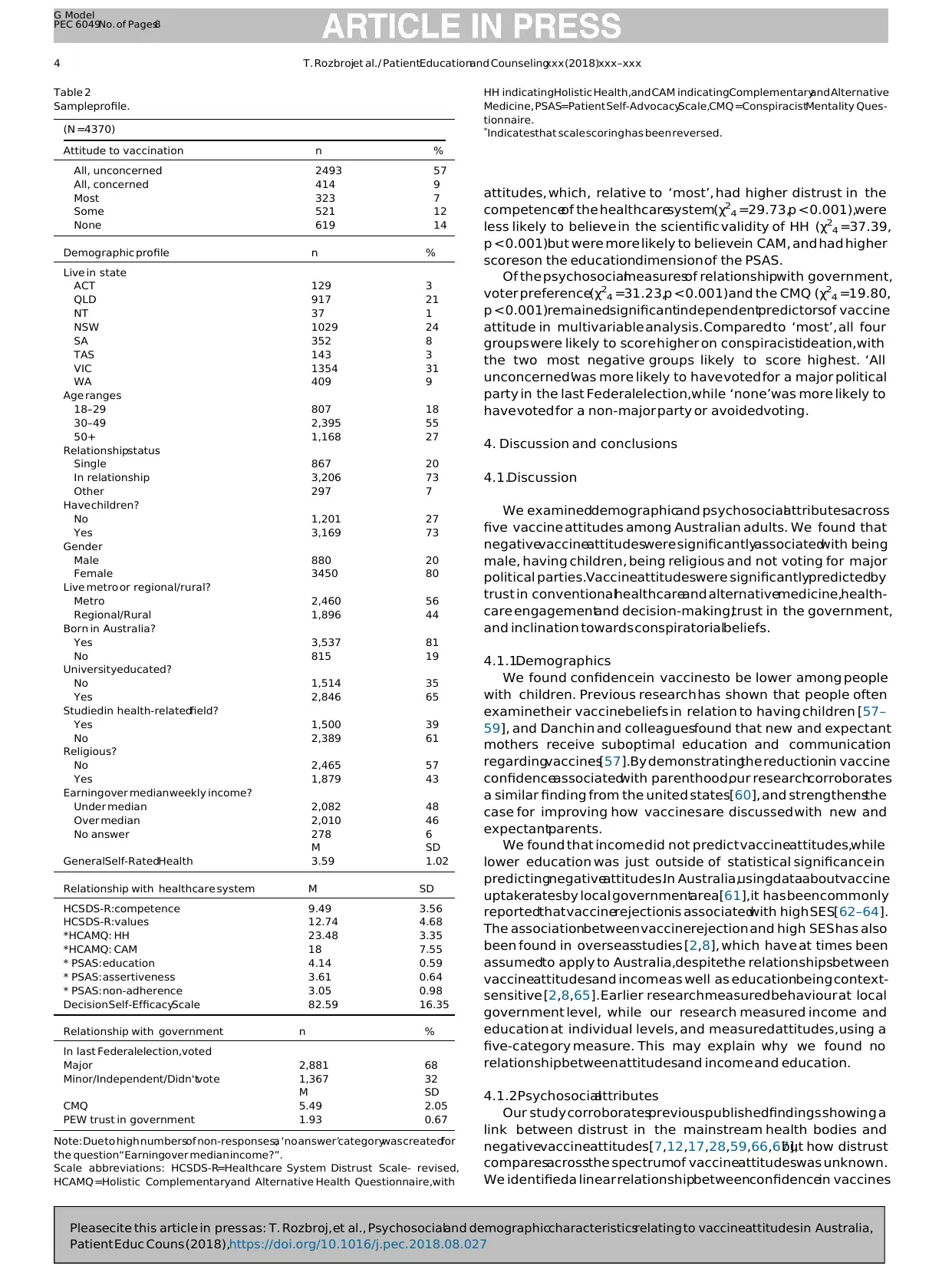

The sampleprofile is displayedin Table2. Typical respondents

were 30–49 yearsold, in a relationship,with children and born in

Australia.Relativeto the Australianpopulation,over-represented

were women (n =80%,comparedto 50.4%in Australiain 2016)[55]

and thosewith a universityeducation(n =65%,comparedto 23.7%

in Australia in 2011) [56]. Among the 4370 respondents,almost

three-fifths supportedvaccineswithout concerns.

3.3.Multivariableanalysis

In the univariableanalyses,all demographicand psychosocial

variables were significantly associatedwith vaccine attitude at

p < 0.001.

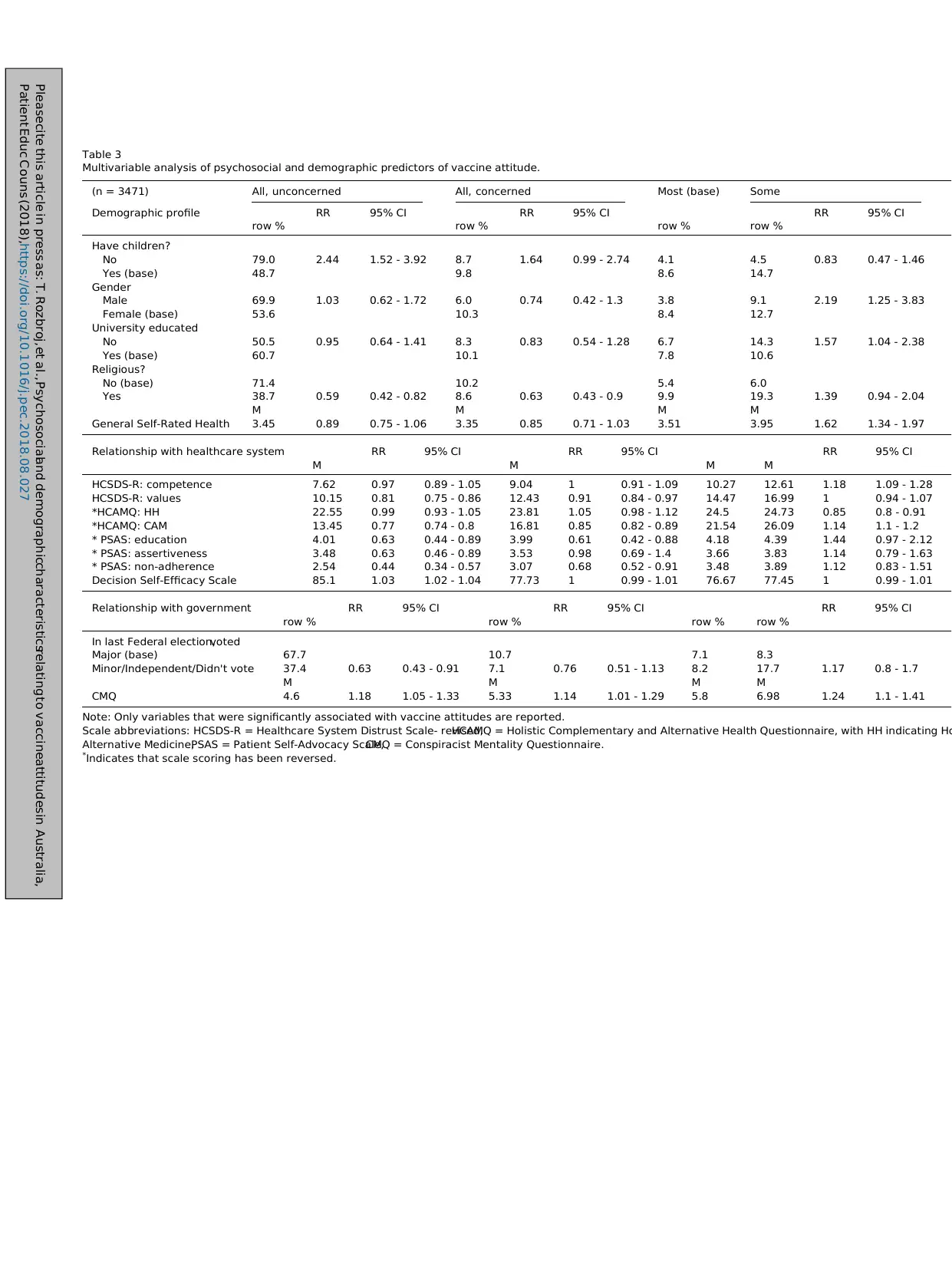

In the multivariableanalysis(Table3), significantindependent

demographicfactorsincluded whether respondentshavechildren

(χ24 =28.40,p < 0.001),respondents’gender(χ24 =16.75,p =0.002),

whether they were religious(χ24 =20.09,p =0.001),and their self-

reported health (χ24 =43.82, p < 0.001). Compared to the ‘most’

group,the two ‘all’ groupswere more likely to be childlessand not

religious,while the two most negativegroupswere more likely to

be male and to report being healthier.The ‘none’group was also

more likely to report havingchildrencomparedto the ‘most’group.

Insignificant predictors included respondents’income (p =0.93),

education (p =0.06) and whether they studied a health-related

field (p =0.09).

All psychosocialmeasuresof relationship with the healthcare

systemwere significantindependentfactorsof vaccineattitudein

the multivariableanalysis.Comparedto the ‘most’group,the two

‘all’ groups had significantly higher trust in the values of the

healthcare system (X24 =55.83, p < 0.001), lower education and

non-adherence scores on the PSAS (χ24 =21.12, p < 0.001 and

χ24 =62.86,p < 0.001respectively),and were less likely to believe

in the scientific validity of CAM (χ24 =313.07,p < 0.001).Further-

more, ‘all unconcerned’was associatedwith lower assertiveness

on the PSAS(χ24 =16.79,p =0.002)but higher decisionself-efficacy

(χ24 =47.19,p < 0.001).This comparedto the two least accepting

T. Rozbrojet al./ PatientEducationand Counselingxxx (2018)xxx–xxx 3

G Model

PEC 6049No. of Pages8

Pleasecite this article in press as: T. Rozbroj, et al., Psychosocialand demographiccharacteristicsrelating to vaccineattitudes in Australia,

Patient Educ Couns (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.027

with 1 indicating “poor health” and 5 indicating “excellent

health” [48].

2.2.3.Relationshipwith healthcaresystem

Relationship with the healthcaresystem was assessedusing

eight measures, covering trust in mainstream and alternative

healthcaresystems,and confidence/involvementin health deci-

sion-making.

Trust in the healthcaresystemwas measuredusing the Revised

Health Care System Distrust Scale (HCSDS-R) [49] on two

dimensions: i) values, comprising five items measuring trust in

the healthcare system’s honesty, motives and equity; and ii)

competence, comprising four items measuring trust in the

competencyof the healthcare system. Answers were provided

on a 5-point Likert scale. Possible score ranges were 5–25 for

values and 4–20 for competence.Higher scores indicate higher

distrust.

Attitudes to alternative medicine were measured using the

Holistic Complementaryand Alternative Health Questionnaire

(HCAMQ) [50] across two dimensions: i) holistic health (HH),

comprisingfive items measuringbelief that health and wellbeing

rely on treating the body holistically; and ii) complementaryand

alternativemedicine(CAM), comprisingsix items measuringbelief

in the scientificvalidity of CAM. Answers were providedon a six-

point Likert scale.Possiblescorerangeswere 5–30 for HH and 6–36

for CAM. Higher scoresindicate greaterbelief in CAM/HH.

Health decision-making was measured using two scales

assessing patient involvement in their health decisions and

confidencein their health decision-makingability. Confidencein

health decision-makingability was measured using the single-

dimensional Decision Self-EfficacyScale [51], which contains 11

items on a five-point Likert scale.Scorescould range between 0-

100.Patientinvolvementin healthdecision-makingwas measured

using the Patient Self-AdvocacyScale(PSAS)[52], which has three

subscales,each comprising four items measured on a 5-point

Likert scale measuringpatients’:i) illness and treatmenteduca-

tion; ii) assertivenessin health decisionmaking; and iii) potential

for non-adherenceto recommendedtreatments.Subscalescores

could range between 1-5. Higher scores indicate greater confi-

dence/involvementin health decision-making.

2.2.4.Relationshipwith government

Relationship with the governmentwas assessedusing three

measures,coveringtrust in government,conspiracistideation and

voter preference.Trust in governmentwas measuredby a single

questiondevelopedby PEW research[53], with possiblescoresof

1-5. High scores indicate high trust. The Conspiracy Mentality

Questionnaire(CMQ) measureddifferencesin the generictenden-

cy for conspiracistideation[54].It containsfive items measuredon

an 11-point scale,with possiblescoresbetween0–10. High scores

indicate high conspiracist ideation. Voter preferencewas mea-

sured by a non-standardisedquestionaskingwhich political party

respondentsvoted for in the last Federalelection,coded as ‘voted

for: major/minor party’.

2.3.Analysis

Descriptivestatisticswere calculatedfor the sample i) overall,

and ii) cross-tabulatedby five vaccine attitudes.Validity of the

categorical vaccine attitude variable was checked using linear

regression,comparingvaccineattitude categorieswith scoreson

the VaccinationScale.Multinomial logistic regressionwas used to

test the extent to which vaccine attitude was predicted by

demographic and psychosocial attributes. The ‘most’ attitude

was assignedthe referencecategory,becausewe were particularly

interested in differences between the three ‘hesitant’ groups.

Univariableregressionswere first conductedfor eachdemographic

and psychosocialvariable.A single multivariable regressionwas

then conducted.Only predictors that were associatedwith the

outcome variable at p < 0.25 in the univariableregressionswere

entered into the multivariable regression.Respondentswho did

not respond on all variablesunder analysis were excludedfrom

multivariableregression,which was conductedwith a sample of

3471.Risk ratios (RR) and 95%confidenceintervals (95%CI) were

calculated,and a Wald test was used to assessthe overall effectof

each predictor variable.Associationsat p < 0.05 were considered

significant.

3. Results

3.1.Preliminaryanalysis

To gaugethe reliability of the five categorymeasureof vaccine

attitude,linear regressionwas usedto comparethe categorieswith

scoreson the VaccinationScale[47].The scalescoressignificantly

differed in the expected direction across the five categories(F

[4,4365]=7319.74,p < 0.001).With the ‘most’categoryas the base,

the coefficients were β =1.69 (p < 0.001) for ‘all unconcerned’,

β =1.27(p < 0.001)for ‘all concerned’,β=-1.83(p < 0.001)for ‘some’,

and β=-2.44(p < 0.001)for ‘none’.This suggeststhat the categorical

outcome variable served as an accurate indicator of vaccine

attitude.

3.2.Sampleprofile

The sampleprofile is displayedin Table2. Typical respondents

were 30–49 yearsold, in a relationship,with children and born in

Australia.Relativeto the Australianpopulation,over-represented

were women (n =80%,comparedto 50.4%in Australiain 2016)[55]

and thosewith a universityeducation(n =65%,comparedto 23.7%

in Australia in 2011) [56]. Among the 4370 respondents,almost

three-fifths supportedvaccineswithout concerns.

3.3.Multivariableanalysis

In the univariableanalyses,all demographicand psychosocial

variables were significantly associatedwith vaccine attitude at

p < 0.001.

In the multivariableanalysis(Table3), significantindependent

demographicfactorsincluded whether respondentshavechildren

(χ24 =28.40,p < 0.001),respondents’gender(χ24 =16.75,p =0.002),

whether they were religious(χ24 =20.09,p =0.001),and their self-

reported health (χ24 =43.82, p < 0.001). Compared to the ‘most’

group,the two ‘all’ groupswere more likely to be childlessand not

religious,while the two most negativegroupswere more likely to

be male and to report being healthier.The ‘none’group was also

more likely to report havingchildrencomparedto the ‘most’group.

Insignificant predictors included respondents’income (p =0.93),

education (p =0.06) and whether they studied a health-related

field (p =0.09).

All psychosocialmeasuresof relationship with the healthcare

systemwere significantindependentfactorsof vaccineattitudein

the multivariableanalysis.Comparedto the ‘most’group,the two

‘all’ groups had significantly higher trust in the values of the

healthcare system (X24 =55.83, p < 0.001), lower education and

non-adherence scores on the PSAS (χ24 =21.12, p < 0.001 and

χ24 =62.86,p < 0.001respectively),and were less likely to believe

in the scientific validity of CAM (χ24 =313.07,p < 0.001).Further-

more, ‘all unconcerned’was associatedwith lower assertiveness

on the PSAS(χ24 =16.79,p =0.002)but higher decisionself-efficacy

(χ24 =47.19,p < 0.001).This comparedto the two least accepting

T. Rozbrojet al./ PatientEducationand Counselingxxx (2018)xxx–xxx 3

G Model

PEC 6049No. of Pages8

Pleasecite this article in press as: T. Rozbroj, et al., Psychosocialand demographiccharacteristicsrelating to vaccineattitudes in Australia,

Patient Educ Couns (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.027

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

attitudes, which, relative to ‘most’, had higher distrust in the

competenceof the healthcaresystem(χ24 =29.73,p < 0.001),were

less likely to believe in the scientific validity of HH (χ24 =37.39,

p < 0.001)but were more likely to believein CAM, and had higher

scoreson the educationdimension of the PSAS.

Of the psychosocialmeasuresof relationshipwith government,

voter preference(χ24 =31.23,p < 0.001) and the CMQ (χ24 =19.80,

p < 0.001)remainedsignificantindependentpredictorsof vaccine

attitude in multivariable analysis. Compared to ‘most’, all four

groups were likely to score higher on conspiracistideation, with

the two most negative groups likely to score highest. ‘All

unconcerned’was more likely to have voted for a major political

party in the last Federalelection,while ‘none’was more likely to

have voted for a non-major party or avoidedvoting.

4. Discussion and conclusions

4.1.Discussion

We examineddemographicand psychosocialattributesacross

five vaccine attitudes among Australian adults. We found that

negativevaccineattitudeswere significantlyassociatedwith being

male, having children, being religious and not voting for major

political parties.Vaccineattitudeswere significantlypredictedby

trust in conventionalhealthcareand alternativemedicine,health-

care engagementand decision-making,trust in the government,

and inclination towards conspiratorialbeliefs.

4.1.1.Demographics

We found confidencein vaccinesto be lower among people

with children. Previous research has shown that people often

examinetheir vaccinebeliefs in relation to having children [57–

59], and Danchin and colleaguesfound that new and expectant

mothers receive suboptimal education and communication

regardingvaccines[57].By demonstratingthe reductionin vaccine

confidenceassociatedwith parenthood,our researchcorroborates

a similar finding from the united states[60], and strengthensthe

case for improving how vaccines are discussed with new and

expectantparents.

We found that income did not predict vaccineattitudes,while

lower education was just outside of statistical significance in

predictingnegativeattitudes.In Australia,usingdataaboutvaccine

uptakeratesby local governmentarea[61],it has been commonly

reportedthat vaccinerejectionis associatedwith high SES[62–64].

The associationbetween vaccinerejection and high SES has also

been found in overseasstudies [2,8], which have at times been

assumedto apply to Australia,despitethe relationshipsbetween

vaccineattitudesand income as well as educationbeing context-

sensitive [2,8,65]. Earlier research measured behaviour at local

government level, while our research measured income and

education at individual levels, and measured attitudes, using a

five-category measure. This may explain why we found no

relationship between attitudesand income and education.

4.1.2.Psychosocialattributes

Our study corroboratesprevious publishedfindings showing a

link between distrust in the mainstream health bodies and

negativevaccineattitudes[7,12,17,28,59,66,67],but how distrust

comparesacrossthe spectrumof vaccineattitudeswas unknown.

We identifieda linear relationshipbetweenconfidencein vaccines

Table 2

Sampleprofile.

(N =4370)

Attitude to vaccination n %

All, unconcerned 2493 57

All, concerned 414 9

Most 323 7

Some 521 12

None 619 14

Demographic profile n %

Live in state

ACT 129 3

QLD 917 21

NT 37 1

NSW 1029 24

SA 352 8

TAS 143 3

VIC 1354 31

WA 409 9

Age ranges

18–29 807 18

30–49 2,395 55

50+ 1,168 27

Relationshipstatus

Single 867 20

In relationship 3,206 73

Other 297 7

Have children?

No 1,201 27

Yes 3,169 73

Gender

Male 880 20

Female 3450 80

Live metro or regional/rural?

Metro 2,460 56

Regional/Rural 1,896 44

Born in Australia?

Yes 3,537 81

No 815 19

Universityeducated?

No 1,514 35

Yes 2,846 65

Studied in health-relatedfield?

Yes 1,500 39

No 2,389 61

Religious?

No 2,465 57

Yes 1,879 43

Earning over median weekly income?

Under median 2,082 48

Over median 2,010 46

No answer 278 6

M SD

GeneralSelf-RatedHealth 3.59 1.02

Relationship with healthcare system M SD

HCSDS-R:competence 9.49 3.56

HCSDS-R:values 12.74 4.68

*HCAMQ: HH 23.48 3.35

*HCAMQ: CAM 18 7.55

* PSAS: education 4.14 0.59

* PSAS: assertiveness 3.61 0.64

* PSAS: non-adherence 3.05 0.98

Decision Self-EfficacyScale 82.59 16.35

Relationship with government n %

In last Federalelection,voted

Major 2,881 68

Minor/Independent/Didn'tvote 1,367 32

M SD

CMQ 5.49 2.05

PEW trust in government 1.93 0.67

Note: Due to high numbersof non-responses,a ‘no answer’categorywas createdfor

the question“Earningover median income?”.

Scale abbreviations: HCSDS-R=Healthcare System Distrust Scale- revised,

HCAMQ =Holistic Complementaryand Alternative Health Questionnaire,with

HH indicatingHolistic Health,and CAM indicatingComplementaryand Alternative

Medicine, PSAS=Patient Self-AdvocacyScale,CMQ =ConspiracistMentality Ques-

tionnaire.

*

Indicatesthat scale scoring has been reversed.

4 T. Rozbrojet al. / PatientEducationand Counselingxxx (2018)xxx–xxx

G Model

PEC 6049No. of Pages8

Pleasecite this article in press as: T. Rozbroj, et al., Psychosocialand demographiccharacteristicsrelating to vaccineattitudes in Australia,

Patient Educ Couns (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.027

competenceof the healthcaresystem(χ24 =29.73,p < 0.001),were

less likely to believe in the scientific validity of HH (χ24 =37.39,

p < 0.001)but were more likely to believein CAM, and had higher

scoreson the educationdimension of the PSAS.

Of the psychosocialmeasuresof relationshipwith government,

voter preference(χ24 =31.23,p < 0.001) and the CMQ (χ24 =19.80,

p < 0.001)remainedsignificantindependentpredictorsof vaccine

attitude in multivariable analysis. Compared to ‘most’, all four

groups were likely to score higher on conspiracistideation, with

the two most negative groups likely to score highest. ‘All

unconcerned’was more likely to have voted for a major political

party in the last Federalelection,while ‘none’was more likely to

have voted for a non-major party or avoidedvoting.

4. Discussion and conclusions

4.1.Discussion

We examineddemographicand psychosocialattributesacross

five vaccine attitudes among Australian adults. We found that

negativevaccineattitudeswere significantlyassociatedwith being

male, having children, being religious and not voting for major

political parties.Vaccineattitudeswere significantlypredictedby

trust in conventionalhealthcareand alternativemedicine,health-

care engagementand decision-making,trust in the government,

and inclination towards conspiratorialbeliefs.

4.1.1.Demographics

We found confidencein vaccinesto be lower among people

with children. Previous research has shown that people often

examinetheir vaccinebeliefs in relation to having children [57–

59], and Danchin and colleaguesfound that new and expectant

mothers receive suboptimal education and communication

regardingvaccines[57].By demonstratingthe reductionin vaccine

confidenceassociatedwith parenthood,our researchcorroborates

a similar finding from the united states[60], and strengthensthe

case for improving how vaccines are discussed with new and

expectantparents.

We found that income did not predict vaccineattitudes,while

lower education was just outside of statistical significance in

predictingnegativeattitudes.In Australia,usingdataaboutvaccine

uptakeratesby local governmentarea[61],it has been commonly

reportedthat vaccinerejectionis associatedwith high SES[62–64].

The associationbetween vaccinerejection and high SES has also

been found in overseasstudies [2,8], which have at times been

assumedto apply to Australia,despitethe relationshipsbetween

vaccineattitudesand income as well as educationbeing context-

sensitive [2,8,65]. Earlier research measured behaviour at local

government level, while our research measured income and

education at individual levels, and measured attitudes, using a

five-category measure. This may explain why we found no

relationship between attitudesand income and education.

4.1.2.Psychosocialattributes

Our study corroboratesprevious publishedfindings showing a

link between distrust in the mainstream health bodies and

negativevaccineattitudes[7,12,17,28,59,66,67],but how distrust

comparesacrossthe spectrumof vaccineattitudeswas unknown.

We identifieda linear relationshipbetweenconfidencein vaccines

Table 2

Sampleprofile.

(N =4370)

Attitude to vaccination n %

All, unconcerned 2493 57

All, concerned 414 9

Most 323 7

Some 521 12

None 619 14

Demographic profile n %

Live in state

ACT 129 3

QLD 917 21

NT 37 1

NSW 1029 24

SA 352 8

TAS 143 3

VIC 1354 31

WA 409 9

Age ranges

18–29 807 18

30–49 2,395 55

50+ 1,168 27

Relationshipstatus

Single 867 20

In relationship 3,206 73

Other 297 7

Have children?

No 1,201 27

Yes 3,169 73

Gender

Male 880 20

Female 3450 80

Live metro or regional/rural?

Metro 2,460 56

Regional/Rural 1,896 44

Born in Australia?

Yes 3,537 81

No 815 19

Universityeducated?

No 1,514 35

Yes 2,846 65

Studied in health-relatedfield?

Yes 1,500 39

No 2,389 61

Religious?

No 2,465 57

Yes 1,879 43

Earning over median weekly income?

Under median 2,082 48

Over median 2,010 46

No answer 278 6

M SD

GeneralSelf-RatedHealth 3.59 1.02

Relationship with healthcare system M SD

HCSDS-R:competence 9.49 3.56

HCSDS-R:values 12.74 4.68

*HCAMQ: HH 23.48 3.35

*HCAMQ: CAM 18 7.55

* PSAS: education 4.14 0.59

* PSAS: assertiveness 3.61 0.64

* PSAS: non-adherence 3.05 0.98

Decision Self-EfficacyScale 82.59 16.35

Relationship with government n %

In last Federalelection,voted

Major 2,881 68

Minor/Independent/Didn'tvote 1,367 32

M SD

CMQ 5.49 2.05

PEW trust in government 1.93 0.67

Note: Due to high numbersof non-responses,a ‘no answer’categorywas createdfor

the question“Earningover median income?”.

Scale abbreviations: HCSDS-R=Healthcare System Distrust Scale- revised,

HCAMQ =Holistic Complementaryand Alternative Health Questionnaire,with

HH indicatingHolistic Health,and CAM indicatingComplementaryand Alternative

Medicine, PSAS=Patient Self-AdvocacyScale,CMQ =ConspiracistMentality Ques-

tionnaire.

*

Indicatesthat scale scoring has been reversed.

4 T. Rozbrojet al. / PatientEducationand Counselingxxx (2018)xxx–xxx

G Model

PEC 6049No. of Pages8

Pleasecite this article in press as: T. Rozbroj, et al., Psychosocialand demographiccharacteristicsrelating to vaccineattitudes in Australia,

Patient Educ Couns (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.027

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Table 3

Multivariable analysis of psychosocial and demographic predictors of vaccine attitude.

(n = 3471) All, unconcerned All, concerned Most (base) Some

Demographic profile RR 95% CI RR 95% CI RR 95% CI

row % row % row % row %

Have children?

No 79.0 2.44 1.52 - 3.92 8.7 1.64 0.99 - 2.74 4.1 4.5 0.83 0.47 - 1.46

Yes (base) 48.7 9.8 8.6 14.7

Gender

Male 69.9 1.03 0.62 - 1.72 6.0 0.74 0.42 - 1.3 3.8 9.1 2.19 1.25 - 3.83

Female (base) 53.6 10.3 8.4 12.7

University educated

No 50.5 0.95 0.64 - 1.41 8.3 0.83 0.54 - 1.28 6.7 14.3 1.57 1.04 - 2.38

Yes (base) 60.7 10.1 7.8 10.6

Religious?

No (base) 71.4 10.2 5.4 6.0

Yes 38.7 0.59 0.42 - 0.82 8.6 0.63 0.43 - 0.9 9.9 19.3 1.39 0.94 - 2.04

M M M M

General Self-Rated Health 3.45 0.89 0.75 - 1.06 3.35 0.85 0.71 - 1.03 3.51 3.95 1.62 1.34 - 1.97

Relationship with healthcare system RR 95% CI RR 95% CI RR 95% CI

M M M M

HCSDS-R: competence 7.62 0.97 0.89 - 1.05 9.04 1 0.91 - 1.09 10.27 12.61 1.18 1.09 - 1.28

HCSDS-R: values 10.15 0.81 0.75 - 0.86 12.43 0.91 0.84 - 0.97 14.47 16.99 1 0.94 - 1.07

*HCAMQ: HH 22.55 0.99 0.93 - 1.05 23.81 1.05 0.98 - 1.12 24.5 24.73 0.85 0.8 - 0.91

*HCAMQ: CAM 13.45 0.77 0.74 - 0.8 16.81 0.85 0.82 - 0.89 21.54 26.09 1.14 1.1 - 1.2

* PSAS: education 4.01 0.63 0.44 - 0.89 3.99 0.61 0.42 - 0.88 4.18 4.39 1.44 0.97 - 2.12

* PSAS: assertiveness 3.48 0.63 0.46 - 0.89 3.53 0.98 0.69 - 1.4 3.66 3.83 1.14 0.79 - 1.63

* PSAS: non-adherence 2.54 0.44 0.34 - 0.57 3.07 0.68 0.52 - 0.91 3.48 3.89 1.12 0.83 - 1.51

Decision Self-Efficacy Scale 85.1 1.03 1.02 - 1.04 77.73 1 0.99 - 1.01 76.67 77.45 1 0.99 - 1.01

Relationship with government RR 95% CI RR 95% CI RR 95% CI

row % row % row % row %

In last Federal election,voted

Major (base) 67.7 10.7 7.1 8.3

Minor/Independent/Didn't vote 37.4 0.63 0.43 - 0.91 7.1 0.76 0.51 - 1.13 8.2 17.7 1.17 0.8 - 1.7

M M M M

CMQ 4.6 1.18 1.05 - 1.33 5.33 1.14 1.01 - 1.29 5.8 6.98 1.24 1.1 - 1.41

Note: Only variables that were significantly associated with vaccine attitudes are reported.

Scale abbreviations: HCSDS-R = Healthcare System Distrust Scale- revised,HCAMQ = Holistic Complementary and Alternative Health Questionnaire, with HH indicating Ho

Alternative Medicine,PSAS = Patient Self-Advocacy Scale,CMQ = Conspiracist Mentality Questionnaire.

*

Indicates that scale scoring has been reversed.

Pleasecite this article in press as: T. Rozbroj, et al., Psychosocialand demographiccharacteristicsrelating to vaccineattitudes in Australia,

Patient Educ Couns (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.027

Multivariable analysis of psychosocial and demographic predictors of vaccine attitude.

(n = 3471) All, unconcerned All, concerned Most (base) Some

Demographic profile RR 95% CI RR 95% CI RR 95% CI

row % row % row % row %

Have children?

No 79.0 2.44 1.52 - 3.92 8.7 1.64 0.99 - 2.74 4.1 4.5 0.83 0.47 - 1.46

Yes (base) 48.7 9.8 8.6 14.7

Gender

Male 69.9 1.03 0.62 - 1.72 6.0 0.74 0.42 - 1.3 3.8 9.1 2.19 1.25 - 3.83

Female (base) 53.6 10.3 8.4 12.7

University educated

No 50.5 0.95 0.64 - 1.41 8.3 0.83 0.54 - 1.28 6.7 14.3 1.57 1.04 - 2.38

Yes (base) 60.7 10.1 7.8 10.6

Religious?

No (base) 71.4 10.2 5.4 6.0

Yes 38.7 0.59 0.42 - 0.82 8.6 0.63 0.43 - 0.9 9.9 19.3 1.39 0.94 - 2.04

M M M M

General Self-Rated Health 3.45 0.89 0.75 - 1.06 3.35 0.85 0.71 - 1.03 3.51 3.95 1.62 1.34 - 1.97

Relationship with healthcare system RR 95% CI RR 95% CI RR 95% CI

M M M M

HCSDS-R: competence 7.62 0.97 0.89 - 1.05 9.04 1 0.91 - 1.09 10.27 12.61 1.18 1.09 - 1.28

HCSDS-R: values 10.15 0.81 0.75 - 0.86 12.43 0.91 0.84 - 0.97 14.47 16.99 1 0.94 - 1.07

*HCAMQ: HH 22.55 0.99 0.93 - 1.05 23.81 1.05 0.98 - 1.12 24.5 24.73 0.85 0.8 - 0.91

*HCAMQ: CAM 13.45 0.77 0.74 - 0.8 16.81 0.85 0.82 - 0.89 21.54 26.09 1.14 1.1 - 1.2

* PSAS: education 4.01 0.63 0.44 - 0.89 3.99 0.61 0.42 - 0.88 4.18 4.39 1.44 0.97 - 2.12

* PSAS: assertiveness 3.48 0.63 0.46 - 0.89 3.53 0.98 0.69 - 1.4 3.66 3.83 1.14 0.79 - 1.63

* PSAS: non-adherence 2.54 0.44 0.34 - 0.57 3.07 0.68 0.52 - 0.91 3.48 3.89 1.12 0.83 - 1.51

Decision Self-Efficacy Scale 85.1 1.03 1.02 - 1.04 77.73 1 0.99 - 1.01 76.67 77.45 1 0.99 - 1.01

Relationship with government RR 95% CI RR 95% CI RR 95% CI

row % row % row % row %

In last Federal election,voted

Major (base) 67.7 10.7 7.1 8.3

Minor/Independent/Didn't vote 37.4 0.63 0.43 - 0.91 7.1 0.76 0.51 - 1.13 8.2 17.7 1.17 0.8 - 1.7

M M M M

CMQ 4.6 1.18 1.05 - 1.33 5.33 1.14 1.01 - 1.29 5.8 6.98 1.24 1.1 - 1.41

Note: Only variables that were significantly associated with vaccine attitudes are reported.

Scale abbreviations: HCSDS-R = Healthcare System Distrust Scale- revised,HCAMQ = Holistic Complementary and Alternative Health Questionnaire, with HH indicating Ho

Alternative Medicine,PSAS = Patient Self-Advocacy Scale,CMQ = Conspiracist Mentality Questionnaire.

*

Indicates that scale scoring has been reversed.

Pleasecite this article in press as: T. Rozbroj, et al., Psychosocialand demographiccharacteristicsrelating to vaccineattitudes in Australia,

Patient Educ Couns (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.027

and trust in both the values and competenceof the healthcare

system.Interestingly,even respondentswho believedall vaccines

should be administered,but had concerns,had lower trust in the

valuesof the healthcaresystemthan those without concerns.The

subscale measured level of agreement on items such as “the

healthcare system:. . . lies to make money”, “experimentson

patientswithout them knowing”,and “coversup its mistakes”[49].

The differencein risk ratios betweenthe two ‘all’ groupsshould be

interpreted with caution, as both scores were calculated in

reference to the ‘most’ category.Nevertheless,the increase in

healthcaresystem distrust associatedwith lower confidencein

vaccines is worrying. HCWs are integral to addressingvaccine

concerns[30,31,68],and this role may be encumberedby patients’

distrust in the healthcaresystem.Distrustof both competenceand

values of the healthcare system among people who distrust

vaccines should be accounted for when responding to vaccine

distrust.

To our knowledge,this studywas the first to assessboth HH and

CAM belief across the spectrum of attitudes. Previous research

linked negativeattitudeswith adherenceto alternativemedicine

in general[30,69–71].Theselinks are supportedby our finding that

negativeattitudeswere associatedwith belief in CAM. But we also

found negativeattitudesto be associatedwith rejectionof HH. This

is interesting,becauseusually belief in HH predictsbelief in CAM

[50,72,73].Studiesfrom other topics showed that, in lieu of belief

in HH, CAM was often chosen due to dissatisfaction with

conventional treatment experiences [74–76]. This explanation

would be plausible for our findings,given that negativeattitudes

were also associatedwith lower trust in the competenceof the

healthcaresystem.It may be worth investigatingthis further in

future research to gain insights into why some people begin

distrusting vaccines.

We found that vaccinerejection relatedto broaderdissatisfac-

tion with governance.On the CMQ, which contains no health-

specific questions [54], negativeattitudes were associatedwith

higher scores, suggesting a higher tendency towards general

conspiracistideation. These findings corroborateanother recent

study showing that antivaccination attitudes are linked to

conspiratorialthinking [23]. Negativeattitudes were also linked

to voting for minor political parties, which supports Larson’s

argument that political views play an important role in vaccine

decisions[21].Previousresearchhas shown links betweenvaccine

rejection and conspiracistviews regarding vaccination [77–79].

Our and other findings[21,23]suggestthat vaccinedistrustmay be

linked to broader anti-establishmentbeliefs.

4.1.3.Implicationsfor taxonomyof vaccineattitudes

Substantialresearcheffortsare beinginvestedinto understand-

ing and addressingvaccine‘hesitancy’[2,18,38–43,80].However,

in our data,the ‘hesitant’categorydoesnot capturea distinct set of

demographic or psychosocial attributes. On most predictor

variables,there is a linear pattern between risk ratios across the

five attitudes,with scores often being most similar between ‘all

unconcerned’ and ‘all concerned, and ‘some’ and ‘none’. Our

researchwas designedto respondto a key aim of the WHO: assess

how the hesitantcategoryrelatesto socioculturalprofiles [2,18].In

responding to this aim, we found it would be better to assess

‘hesitancy’using a more granularset of categories,like thosein the

present study, or other alternatives,like the categoriesused by

Leask and colleagues[14].

4.2.Limitations

This researchhad severallimitations.It was not viableto recruit

a representativesample.Sincevaccinationis refusedby only about

2%of the population [7,25],untargetedrecruitmentof this group

would not be feasible.As noted in the results,some demographic

attributeswere over-represented.But overall,a diversesamplewas

achieved.

The cross-sectionaldesign only enabled us to assessassocia-

tions. Understanding the causal interplay between vaccine

attitudes and demographic and psychosocial attributes would

providefurther understandingof how particularattitudesemerge.

Longitudinal design could be considered for future research to

assess directions of causality between attitudes and broader

attributes.

4.3.Practiceimplications

This researchcontributesto understandingvaccineattitudesin

their socio-culturalcontext,which is useful for improving patient

education and communication about vaccines. Our findings

suggestthat vaccinepromotion,which tends to focus on benefits

and safety of vaccines,should also focus on building trust in the

governmentand healthcaresystem.Both healthcaresystem and

governmentwere distrusted by participants who lacked confi-

dence in vaccines,meaning their messagesabout benefits and

safety of vaccines may not persuade people who lack vaccine

confidence.Furthermore,we found that respondentswho distrust

vaccines are highly health-literate, engaged and independent

health consumers,who havelikely encounteredcommonvaccine-

promotion messages.Communicationsresponding to their con-

cerns should be written for a sophisticatedaudience,and respond

to their nuanced concerns in depth. Finally, the variance in

psychosocialprofiles betweeneach of the three subgroupsfalling

under the ‘vaccinehesitancy’categorysuggeststhat communica-

tion should focus on subgroups,rather than target‘hesitancy’as a

whole. Communicationsneed to be sensitiveto the psychosocial

contextwithin which vaccinebeliefsoccur [18],and the hesitancy

categoryappearsto group distinct psychosocialprofiles together.

Similarly,in measuringattitudes,subgroupscomprisinghesitancy

may be more appropriateunits of measurementthan the category

of hesitancy.

4.4.Conclusion

In assessinghow vaccineattitudes relate to psychosocialand

demographic attributes, we found that Australians holding

negative attitudes to vaccines are more likely to distrust the

government,the healthcare system, and to have conspiratorial

beliefs. They are also more likely to report being informed,

independenthealth consumerswith better-than-averagehealth.

These factors may be important to consider in communicating

about vaccines.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

[1] Departmentof Health, Further StrengtheningNo Jab, No Pay. 2017 01 May

Availablefrom:, (2017). http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ministers/

publishing.nsf/Content/health-mediarel-yr2017-hunt041.htm.

[2] World Health Organisation,Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine

Hesitancy,(2014) Geneva,Switzerland.

[3] Department of Health, AIR - All Children CoverageData [cited 2017 22

November2017];Availablefrom:, (2017). http://www.immunise.health.gov.

au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/all-child-cover-data.htm.

[4] H. Brynley,et al.,Annual ImmunisationCoverageReport2015,NationalCentre

for ImmunisationResearchand Surveillanceof VaccinePreventableDiseases:

The Children’sHospital at Westmeadand University of Sydney,2015.

[5] F.H.Beard,et al.,Trendsand patternsin vaccinationobjection,Australia,2002–

2013,Med. J. Aust. 204 (7) (2016)275, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5694/

mja15.01226.

6 T. Rozbrojet al. / PatientEducationand Counselingxxx (2018)xxx–xxx

G Model

PEC 6049No. of Pages8

Pleasecite this article in press as: T. Rozbroj, et al., Psychosocialand demographiccharacteristicsrelating to vaccineattitudes in Australia,

Patient Educ Couns (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.027

system.Interestingly,even respondentswho believedall vaccines

should be administered,but had concerns,had lower trust in the

valuesof the healthcaresystemthan those without concerns.The

subscale measured level of agreement on items such as “the

healthcare system:. . . lies to make money”, “experimentson

patientswithout them knowing”,and “coversup its mistakes”[49].

The differencein risk ratios betweenthe two ‘all’ groupsshould be

interpreted with caution, as both scores were calculated in

reference to the ‘most’ category.Nevertheless,the increase in

healthcaresystem distrust associatedwith lower confidencein

vaccines is worrying. HCWs are integral to addressingvaccine

concerns[30,31,68],and this role may be encumberedby patients’

distrust in the healthcaresystem.Distrustof both competenceand

values of the healthcare system among people who distrust

vaccines should be accounted for when responding to vaccine

distrust.

To our knowledge,this studywas the first to assessboth HH and

CAM belief across the spectrum of attitudes. Previous research

linked negativeattitudeswith adherenceto alternativemedicine

in general[30,69–71].Theselinks are supportedby our finding that

negativeattitudeswere associatedwith belief in CAM. But we also

found negativeattitudesto be associatedwith rejectionof HH. This

is interesting,becauseusually belief in HH predictsbelief in CAM

[50,72,73].Studiesfrom other topics showed that, in lieu of belief

in HH, CAM was often chosen due to dissatisfaction with

conventional treatment experiences [74–76]. This explanation

would be plausible for our findings,given that negativeattitudes

were also associatedwith lower trust in the competenceof the

healthcaresystem.It may be worth investigatingthis further in

future research to gain insights into why some people begin

distrusting vaccines.

We found that vaccinerejection relatedto broaderdissatisfac-

tion with governance.On the CMQ, which contains no health-

specific questions [54], negativeattitudes were associatedwith

higher scores, suggesting a higher tendency towards general

conspiracistideation. These findings corroborateanother recent

study showing that antivaccination attitudes are linked to

conspiratorialthinking [23]. Negativeattitudes were also linked

to voting for minor political parties, which supports Larson’s

argument that political views play an important role in vaccine

decisions[21].Previousresearchhas shown links betweenvaccine

rejection and conspiracistviews regarding vaccination [77–79].

Our and other findings[21,23]suggestthat vaccinedistrustmay be

linked to broader anti-establishmentbeliefs.

4.1.3.Implicationsfor taxonomyof vaccineattitudes

Substantialresearcheffortsare beinginvestedinto understand-

ing and addressingvaccine‘hesitancy’[2,18,38–43,80].However,

in our data,the ‘hesitant’categorydoesnot capturea distinct set of

demographic or psychosocial attributes. On most predictor

variables,there is a linear pattern between risk ratios across the

five attitudes,with scores often being most similar between ‘all

unconcerned’ and ‘all concerned, and ‘some’ and ‘none’. Our

researchwas designedto respondto a key aim of the WHO: assess

how the hesitantcategoryrelatesto socioculturalprofiles [2,18].In

responding to this aim, we found it would be better to assess

‘hesitancy’using a more granularset of categories,like thosein the

present study, or other alternatives,like the categoriesused by

Leask and colleagues[14].

4.2.Limitations

This researchhad severallimitations.It was not viableto recruit

a representativesample.Sincevaccinationis refusedby only about

2%of the population [7,25],untargetedrecruitmentof this group

would not be feasible.As noted in the results,some demographic

attributeswere over-represented.But overall,a diversesamplewas

achieved.

The cross-sectionaldesign only enabled us to assessassocia-

tions. Understanding the causal interplay between vaccine

attitudes and demographic and psychosocial attributes would

providefurther understandingof how particularattitudesemerge.

Longitudinal design could be considered for future research to

assess directions of causality between attitudes and broader

attributes.

4.3.Practiceimplications

This researchcontributesto understandingvaccineattitudesin

their socio-culturalcontext,which is useful for improving patient

education and communication about vaccines. Our findings

suggestthat vaccinepromotion,which tends to focus on benefits

and safety of vaccines,should also focus on building trust in the

governmentand healthcaresystem.Both healthcaresystem and

governmentwere distrusted by participants who lacked confi-

dence in vaccines,meaning their messagesabout benefits and

safety of vaccines may not persuade people who lack vaccine

confidence.Furthermore,we found that respondentswho distrust

vaccines are highly health-literate, engaged and independent

health consumers,who havelikely encounteredcommonvaccine-

promotion messages.Communicationsresponding to their con-

cerns should be written for a sophisticatedaudience,and respond

to their nuanced concerns in depth. Finally, the variance in

psychosocialprofiles betweeneach of the three subgroupsfalling

under the ‘vaccinehesitancy’categorysuggeststhat communica-

tion should focus on subgroups,rather than target‘hesitancy’as a

whole. Communicationsneed to be sensitiveto the psychosocial

contextwithin which vaccinebeliefsoccur [18],and the hesitancy

categoryappearsto group distinct psychosocialprofiles together.

Similarly,in measuringattitudes,subgroupscomprisinghesitancy

may be more appropriateunits of measurementthan the category

of hesitancy.

4.4.Conclusion

In assessinghow vaccineattitudes relate to psychosocialand

demographic attributes, we found that Australians holding

negative attitudes to vaccines are more likely to distrust the

government,the healthcare system, and to have conspiratorial

beliefs. They are also more likely to report being informed,

independenthealth consumerswith better-than-averagehealth.

These factors may be important to consider in communicating

about vaccines.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

[1] Departmentof Health, Further StrengtheningNo Jab, No Pay. 2017 01 May

Availablefrom:, (2017). http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ministers/

publishing.nsf/Content/health-mediarel-yr2017-hunt041.htm.

[2] World Health Organisation,Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine

Hesitancy,(2014) Geneva,Switzerland.

[3] Department of Health, AIR - All Children CoverageData [cited 2017 22

November2017];Availablefrom:, (2017). http://www.immunise.health.gov.

au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/all-child-cover-data.htm.

[4] H. Brynley,et al.,Annual ImmunisationCoverageReport2015,NationalCentre

for ImmunisationResearchand Surveillanceof VaccinePreventableDiseases:

The Children’sHospital at Westmeadand University of Sydney,2015.

[5] F.H.Beard,et al.,Trendsand patternsin vaccinationobjection,Australia,2002–

2013,Med. J. Aust. 204 (7) (2016)275, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5694/

mja15.01226.

6 T. Rozbrojet al. / PatientEducationand Counselingxxx (2018)xxx–xxx

G Model

PEC 6049No. of Pages8

Pleasecite this article in press as: T. Rozbroj, et al., Psychosocialand demographiccharacteristicsrelating to vaccineattitudes in Australia,

Patient Educ Couns (2018),https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.027

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

[6] A. Dey,et al., Summaryof National SurveillanceData on VaccinePreventable

Diseasesin Australia,2008–2011,National Centrefor ImmunisationResearch

and Surveillanceof Vaccine PreventableDiseases:University of Sydney,

2016.

[7] M. Yui Kwan Chow, et al., Parentalattitudes,beliefs,behavioursand concerns

towards childhood vaccinationsin Australia: a national online survey,Aust.

Fam. Phys. 46 (2017)145–151.

[8] H.J. Larson,et al.,The stateof vaccineconfidence2016:globalinsightsthrough

a 67-Countrysurvey,EBioMedicine(2016),doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.

ebiom.2016.08.042.

[9] L. Caron-Poulin,et al., Burdenand deathsassociatedwith vaccinepreventable

diseasesin Canada,2010-2014,Online J. Public Health Inform. 9 (1) (2017)

e094, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/ojphi.v9i1.7676.

[10] Centresfor DiseaseControl and Prevention,Epidemiologyand Preventionof

Vaccine-preventableDiseases:ReportedCasesand DeathsFrom Vaccine

PreventableDiseases,United States[cited 201829th July]; Availablefrom:, (

2018). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/

appendices/e/reported-cases.pdf.

[11] S. Wicker, H.C. Maltezou, Vaccine-preventablediseasesin Europe: where do

we stand? Expert Rev.Vaccines13 (8) (2014)979–987,doi:http://dx.doi.org/

10.1586/14760584.2014.933077.

[12] O. Yaqub,et al., Attitudes to vaccination:a critical review, Soc. Sci. Med. 112

(2014)1–11,doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.018.

[13] J. Leask, et al., What maintains parental support for vaccination when

challengedby anti-vaccinationmessages?A qualitativestudy,Vaccine24 (49–

50) (2006) 7238–7245,doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.010.

[14] J. Leask,et al., Communicatingwith parentsabout vaccination:a framework

for healthprofessionals,BMC Pediatr.12 (1) (2012)1–11,doi:http://dx.doi.org/

10.1186/1471-2431-12-154.

[15] A. Sadaf, et al., A systematicreview of interventionsfor reducing parental

vaccinerefusaland vaccinehesitancy,Vaccine31 (40) (2013)4293–4304,doi:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.07.013.

[16] E. Dubé, D. Gagnon,N.E. MacDonald,Strategiesintended to addressvaccine

hesitancy:review of published reviews,Vaccine33 (34) (2015) 4191–4203,

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.041.

[17] C. Jarrett, et al., Strategiesfor addressingvaccine hesitancy– a systematic

review, Vaccine 33 (34) (2015)4180–4190,doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.

vaccine.2015.04.040.

[18] World Health Organisation,Strategiesfor AddressingVaccine Hesitancy: a

SystematicReview,(2014) Geneva,Switzerland.

[19] P.R. Ward, et al., Understanding the perceived logic of care by vaccine-

hesitant and vaccine-refusingparents: a qualitativestudy in Australia,PLoS

ONE 12 (10) (2017),doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185955

e0185955.

[20] J.C. Bester,Vaccinerefusaland trust: the troublewith coercionand education

and suggestionsfor a cure,J. Bioeth.Inq. 12 (4) (2015)555–559,doi:http://dx.

doi.org/10.1007/s11673-015-9673-1.

[21] H.J. Larson,Politics and Public Trust ShapeVaccineRisk Perceptions,Nat.Hum.

Behav.(2018),doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0331-6.