HMSV3503 Qualitative Research Study Review: Health and Human Services

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/26

|11

|10373

|23

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive review of a qualitative research study by Broad et al. (2017), focusing on the experiences of young people transitioning from Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) to Adult Mental Health Services (AMHS). The study, involving 18 articles and 253 unique service-users, utilized thematic synthesis to analyze the perspectives of youth, highlighting the challenges and opportunities associated with this transition. Key findings revealed that youth value preparation, flexible timing, individualized plans, and continuity in care. The analysis underscores the significant cultural shift between CAMHS and AMHS and emphasizes the need for individualized and flexible approaches to transition, incorporating youth perspectives for service improvement. The study also discusses the importance of research in healthcare for evidence-based practice, problem identification, and decision-making capabilities, ultimately improving patient care and outcomes. The report also outlines the key components of the research process and the ethical considerations involved in research.

R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E Open Access

Youth experiences of transition from child

mentalhealth services to adult mental

health services:a qualitative thematic

synthesis

Kathleen L.Broad1

, Vijay K.Sandhu2

, Nadiya Sunderji3,4,5*

and Alice Charach6,7

Abstract

Background:Adolescence and young adulthood is a vulnerable time during which young people experience

development milestones,as well as an increased incidence of mental illness.During this time,youth also transition

between Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) to Adult Mental Health Services (AMHS).This transition

puts many youth at risk of disengagement from service use;however,our understanding of this transition from

the perspective of youth is limited.This systematic review aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding

of youth experiences of transition from CAMHS to AMHS,through a qualitative thematic synthesis of the extant

literature in this area.

Method:Published and unpublished literature was searched using keywords targeting three subject areas:Transition,

Age and Mental Health.Studies were included if they qualitatively explored the perceptions and experiences of

who received mental health services in both CAMHS and AMHS.There were no limitations on diagnosis or age of

youth.Studies examining youth with chronic physical health conditions were excluded.

Results: Eighteen studies,representing 14 datasets and the experiences of 253 unique service-users were includ

Youth experiences of moving from CAMHS and AMHS are influenced by concurrent life transitions and thei

preferences regarding autonomy and independence.Youth identified preparation,flexible transition timing,

individualized transition plans,and informationalcontinuity as positive factors during transition.Youth also valued

joint working and relationalcontinuity between CAMHS and AMHS.

Conclusions:Youth experience a dramatic culture shift between CAMHS and AMHS,which can be mitigated by

individualized and flexible approaches to transition.Youth have valuable perspectives to guide the intelligent

design of mental health services and their perspectives should be used to inform tools to evaluate and inc

youth perspectives into transitional service improvement.

Trial registration: Clinical Trial or Systematic Review Registry:PROSPERO International Prospective Register of

Systematic Reviews CRD42014013799.

Keywords: Transition to adult care,Transitional programs,Health transition,Continuum of care,Adolescent,Young

adult,Child adolescent psychiatry,Adolescent health services,Mental disorders,Mental health services

* Correspondence:sunderjin@smh.ca

3MentalHealth and Addictions Service,St.Michael’s Hospital,Toronto,ON,

Canada

4Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute,Toronto,ON,Canada

Fulllist of author information is available at the end of the article

© The Author(s).2017 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

InternationalLicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided you give appropriate credit to the originalauthor(s) and the source,provide a link to

the Creative Commons license,and indicate if changes were made.The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,unless otherwise stated.

Broad et al.BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380

DOI10.1186/s12888-017-1538-1

Youth experiences of transition from child

mentalhealth services to adult mental

health services:a qualitative thematic

synthesis

Kathleen L.Broad1

, Vijay K.Sandhu2

, Nadiya Sunderji3,4,5*

and Alice Charach6,7

Abstract

Background:Adolescence and young adulthood is a vulnerable time during which young people experience

development milestones,as well as an increased incidence of mental illness.During this time,youth also transition

between Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) to Adult Mental Health Services (AMHS).This transition

puts many youth at risk of disengagement from service use;however,our understanding of this transition from

the perspective of youth is limited.This systematic review aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding

of youth experiences of transition from CAMHS to AMHS,through a qualitative thematic synthesis of the extant

literature in this area.

Method:Published and unpublished literature was searched using keywords targeting three subject areas:Transition,

Age and Mental Health.Studies were included if they qualitatively explored the perceptions and experiences of

who received mental health services in both CAMHS and AMHS.There were no limitations on diagnosis or age of

youth.Studies examining youth with chronic physical health conditions were excluded.

Results: Eighteen studies,representing 14 datasets and the experiences of 253 unique service-users were includ

Youth experiences of moving from CAMHS and AMHS are influenced by concurrent life transitions and thei

preferences regarding autonomy and independence.Youth identified preparation,flexible transition timing,

individualized transition plans,and informationalcontinuity as positive factors during transition.Youth also valued

joint working and relationalcontinuity between CAMHS and AMHS.

Conclusions:Youth experience a dramatic culture shift between CAMHS and AMHS,which can be mitigated by

individualized and flexible approaches to transition.Youth have valuable perspectives to guide the intelligent

design of mental health services and their perspectives should be used to inform tools to evaluate and inc

youth perspectives into transitional service improvement.

Trial registration: Clinical Trial or Systematic Review Registry:PROSPERO International Prospective Register of

Systematic Reviews CRD42014013799.

Keywords: Transition to adult care,Transitional programs,Health transition,Continuum of care,Adolescent,Young

adult,Child adolescent psychiatry,Adolescent health services,Mental disorders,Mental health services

* Correspondence:sunderjin@smh.ca

3MentalHealth and Addictions Service,St.Michael’s Hospital,Toronto,ON,

Canada

4Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute,Toronto,ON,Canada

Fulllist of author information is available at the end of the article

© The Author(s).2017 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

InternationalLicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided you give appropriate credit to the originalauthor(s) and the source,provide a link to

the Creative Commons license,and indicate if changes were made.The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,unless otherwise stated.

Broad et al.BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380

DOI10.1186/s12888-017-1538-1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Background

At least 75% ofmentalhealth problems and illness have

onset in childhood,adolescence,or young adulthood [1].

However,this increased incidence of mental health condi-

tionsin youth correspondsto a weak pointin mental

health care provision [2].The transition from Child and

AdolescentMentalHealth Services (CAMHS)to Adult

Mental Health Services (AMHS) typically occurs between

18 and 21 years according to traditional age boundaries of

service provision organizations,a period that overlaps im-

portant development milestones for emerging adults [3].

This is a vulnerable period [4] during which service users

may disengage from utilizing mentalhealth servicesat

higher rates than other age cohorts [5, 6].

Many factors may contribute to youth disengagement,

including disease-specific ambivalence ordenial[7, 8]

and the potentialfor mentalillness and/or addictions to

interfere with functioning and with acceptance of formal

supports [9,10].It has also been postulated that differ-

ences betweenCAMHS and AMHS servicesmay

contribute to high disengagementrates [11].However,

overallfactors contributing to disengagement,especially

from the perspective of youth remain poorly understood.

Even when youth do receive care in AMHS,only 23%

report finding the service helpful [12].Gaps and subopti-

malcare during this vulnerable time have the potential

for lasting functionalimpairmentand development

derailment[13, 14]. Age-specificoutpatientprograms

have been shown to increasementalhealth service

utilization,compared to standard adultoutpatientpro-

grams[15];however,they lack consistentevidence of

effectiveness [16].Given the vulnerability ofthis period

and the unique needs of transition-aged youth,it is cru-

cialto further understand youth experiences during the

transition from CAMHS to AMHS.

Previoussystematicreviewshaveshown thatyoung

people transitioning to adulthealth services experience

concern over a loss of familiar surroundings and relation-

ships [17] and want providers to be sensitive to their di-

verse needs [18].Personalaccounts from youth [19] and

stakeholders [20, 21] have emphasized the need to directly

involve young adults in the development of mental health

services.Existing literature reviews ofservice transitions

for youth with mental health concerns have identified gaps

in the provision of transitionalcare [22],however,few of

the includedstudiesexaminedthe experiencesand

perspectives ofyouth [23–25].Thus,the youth voice in

mentalhealth planning and service deliveryis under-

represented, and their subjective experiences of transition-

ing from CMHS to AMHS are insufficiently understood.

Our primary aim is to understand and describe the sub-

jective experiences ofyoung people with mentalhealth

problems as they transition from the child and adolescent

services to adult mental health services.This information

will be helpful in planning services to address the needs of

youth transitioning between service systems.

Methods

In this systematic review,we examined youth experi-

ences as they transition from CAMHS to AMHS.The

scope was international,and focusedon qualitative

materialbecausequalitativestudiesenablerich and

open-ended exploration ofsubjective experiences.Such

reviewshave the advantageof providinga greater

breadth and depth ofunderstanding by accessing a lar-

ger number and diversity of service users accounts and a

greaterrangeof methodologiesto elicit and analyze

these accounts [26].This review was designed as a the-

matic synthesis [27],a method thatadapts approaches

from both meta-ethnography and grounded theory and

has been used in severalsystematic reviews examining

people’s perspectives [26,28].Thematic synthesis allows

our analysisto “stay close”to the expressed viewsof

youth in the primary studies and retain particularities,

while also allowing development ofhigher levelthemes

occurringacrossmultiplestudy populationsto offer

both cumulative and novelinterpretations ofthe find-

ings from primary studies as a whole [27].Thus, by being

interpretative and not merely aggregative, this type of syn-

thesis can reduce uncertainty (e.g.in the case of recurrent

themes across studies) and also enhance complexity (e.g.

by highlighting differences and discrepancies) [29].

This review followed the “Enhancing Transparency in

Reporting the Synthesisof QualitativeResearch”

(ENTREQ) guidelines[29] (See Additionalfile 1 for

ENTREQ checklist) and consisted of (1) a systematic lit-

erature search for relevant qualitative and mixed methods

research reports;(2) criticalappraisalof included reports;

and (3) inductive and iterative analysis of included reports.

The protocolfor this thematic synthesis was published a

prioriwith PROSPERO Internationalprospective register

of systematicreviews (availableonline at http://

www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.asp?ID=CRD

42014013799; registration number CRD42014013799).

Search strategy

We searched both published and unpublished (“grey”)

literature.We identified published articles through sys-

tematic searchesof the following electronic databases

for academic journals from inception to October 2014:

MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Social

Services Abstracts,Applied SocialSciences Indexes and

Abstracts (ASSIA);and ofthe following evidence-based

medicine databases:The Cochrane database ofsystem-

atic reviews,EBM Reviews, The Campbell Collaboration,

and Centre for Reviews and Dissemination.A systematic

search strategy was developed with the assistance ofa

Broad et al.BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380 Page 2 of 11

At least 75% ofmentalhealth problems and illness have

onset in childhood,adolescence,or young adulthood [1].

However,this increased incidence of mental health condi-

tionsin youth correspondsto a weak pointin mental

health care provision [2].The transition from Child and

AdolescentMentalHealth Services (CAMHS)to Adult

Mental Health Services (AMHS) typically occurs between

18 and 21 years according to traditional age boundaries of

service provision organizations,a period that overlaps im-

portant development milestones for emerging adults [3].

This is a vulnerable period [4] during which service users

may disengage from utilizing mentalhealth servicesat

higher rates than other age cohorts [5, 6].

Many factors may contribute to youth disengagement,

including disease-specific ambivalence ordenial[7, 8]

and the potentialfor mentalillness and/or addictions to

interfere with functioning and with acceptance of formal

supports [9,10].It has also been postulated that differ-

ences betweenCAMHS and AMHS servicesmay

contribute to high disengagementrates [11].However,

overallfactors contributing to disengagement,especially

from the perspective of youth remain poorly understood.

Even when youth do receive care in AMHS,only 23%

report finding the service helpful [12].Gaps and subopti-

malcare during this vulnerable time have the potential

for lasting functionalimpairmentand development

derailment[13, 14]. Age-specificoutpatientprograms

have been shown to increasementalhealth service

utilization,compared to standard adultoutpatientpro-

grams[15];however,they lack consistentevidence of

effectiveness [16].Given the vulnerability ofthis period

and the unique needs of transition-aged youth,it is cru-

cialto further understand youth experiences during the

transition from CAMHS to AMHS.

Previoussystematicreviewshaveshown thatyoung

people transitioning to adulthealth services experience

concern over a loss of familiar surroundings and relation-

ships [17] and want providers to be sensitive to their di-

verse needs [18].Personalaccounts from youth [19] and

stakeholders [20, 21] have emphasized the need to directly

involve young adults in the development of mental health

services.Existing literature reviews ofservice transitions

for youth with mental health concerns have identified gaps

in the provision of transitionalcare [22],however,few of

the includedstudiesexaminedthe experiencesand

perspectives ofyouth [23–25].Thus,the youth voice in

mentalhealth planning and service deliveryis under-

represented, and their subjective experiences of transition-

ing from CMHS to AMHS are insufficiently understood.

Our primary aim is to understand and describe the sub-

jective experiences ofyoung people with mentalhealth

problems as they transition from the child and adolescent

services to adult mental health services.This information

will be helpful in planning services to address the needs of

youth transitioning between service systems.

Methods

In this systematic review,we examined youth experi-

ences as they transition from CAMHS to AMHS.The

scope was international,and focusedon qualitative

materialbecausequalitativestudiesenablerich and

open-ended exploration ofsubjective experiences.Such

reviewshave the advantageof providinga greater

breadth and depth ofunderstanding by accessing a lar-

ger number and diversity of service users accounts and a

greaterrangeof methodologiesto elicit and analyze

these accounts [26].This review was designed as a the-

matic synthesis [27],a method thatadapts approaches

from both meta-ethnography and grounded theory and

has been used in severalsystematic reviews examining

people’s perspectives [26,28].Thematic synthesis allows

our analysisto “stay close”to the expressed viewsof

youth in the primary studies and retain particularities,

while also allowing development ofhigher levelthemes

occurringacrossmultiplestudy populationsto offer

both cumulative and novelinterpretations ofthe find-

ings from primary studies as a whole [27].Thus, by being

interpretative and not merely aggregative, this type of syn-

thesis can reduce uncertainty (e.g.in the case of recurrent

themes across studies) and also enhance complexity (e.g.

by highlighting differences and discrepancies) [29].

This review followed the “Enhancing Transparency in

Reporting the Synthesisof QualitativeResearch”

(ENTREQ) guidelines[29] (See Additionalfile 1 for

ENTREQ checklist) and consisted of (1) a systematic lit-

erature search for relevant qualitative and mixed methods

research reports;(2) criticalappraisalof included reports;

and (3) inductive and iterative analysis of included reports.

The protocolfor this thematic synthesis was published a

prioriwith PROSPERO Internationalprospective register

of systematicreviews (availableonline at http://

www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.asp?ID=CRD

42014013799; registration number CRD42014013799).

Search strategy

We searched both published and unpublished (“grey”)

literature.We identified published articles through sys-

tematic searchesof the following electronic databases

for academic journals from inception to October 2014:

MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Social

Services Abstracts,Applied SocialSciences Indexes and

Abstracts (ASSIA);and ofthe following evidence-based

medicine databases:The Cochrane database ofsystem-

atic reviews,EBM Reviews, The Campbell Collaboration,

and Centre for Reviews and Dissemination.A systematic

search strategy was developed with the assistance ofa

Broad et al.BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380 Page 2 of 11

librarian,and peer-reviewed by a second librarian.Key-

words,their truncationsand relevantdatabase-specific

subjectheadings and MeSH terms were used,targeting

three subjectareas:transition,age and mentalhealth.

For an example search strategy see Additional file 2.

We identified additionalpublished literature through

searchesof referencelists of relevantarticles(using

Science Citation Index and hand searching) and forward

citationsof relevantarticles(using ScienceCitation

Index or Google Scholar).We identified unpublished lit-

eraturethrough Googlesearcheswith the samekey-

words, and by contactingexpertsand key authors

identified in the search of published literature.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included studiespublished in English thatused a

qualitative methodology to (1) Describe the perceptions

and experiences of youth utilizing mental health services

and (2) Explore their experiences of receiving services or

care:(a) During the transition from CAMHS to AMHS

setting or (b) In both the CAMHS and AMHS settings.

We included allstudies examining young adults who

have utilized mentalhealth services,with no limitations

on diagnosis,age,ethnicity or geographic locale.We ex-

cluded studies examining youth with exclusively chronic

physicalhealth conditions because young people utiliz-

ing mentalhealth services have been much less studied

and may experienceunique challengescompared to

young people with primarily physical disabilities [30].

All titlesand abstractswere reviewed independently

by two research team members(KB and VS) using

DistillerSR,to organize the search,screen titles,and ab-

stracts and extractdata.Any differences were resolved

by consensus amongst the two team members (KB and

VS),and,if necessary,a third team member (NS).Inter--

rateragreementfor inclusion ofstudieswas assessed

using the chance-corrected Kappa statistic.Agreement

for inclusion atthe full textlevelranged from Kappa

scores of 86% to 95%.

Quality assessment

We critically appraised allstudies in duplicate (KB and

VS) using the Critical AppraisalSkills Programme

(CASP) Tool, which provideskey criteriarelevantto

criticallyappraisingqualitativeresearchstudies(e.g.

appropriateness of research design,consideration of eth-

icalissues,rigour ofdata analysis) [31].Any differences

were resolved byconsensusamongstthe two team

members.All studies were included in final analysis.

Data analysis

We conducted an initialcontentanalysis ofindividual

studies,followedby a thematicsynthesisacrossall

studies [27],focusing only on contentrepresenting the

views ofyouth (typically,sections labelled “findings” or

“results”).

Three ofthe authors (KB,VS and NS) independently

read the textof three included studiesand generated

“codes”,and then met over multiple sessions to develop

a consensus ofcodes and their meanings (i.e.a coding

dictionary).We then continued to analyze three more

studiesindependently,meeting regularly to triangulate

perspectives and revise the coding dictionary by adding,

merging,deleting,or modifying codes.Once the codes

were not changing,the remainder ofthe included stud-

ies were coded by the first author (KB).KB then led the

thematic analysis identifying over-arching themes emer-

ging from the results of the studies as a whole and com-

paring and contrastingfindings across studiesand

populations.

Results

Description of included studies

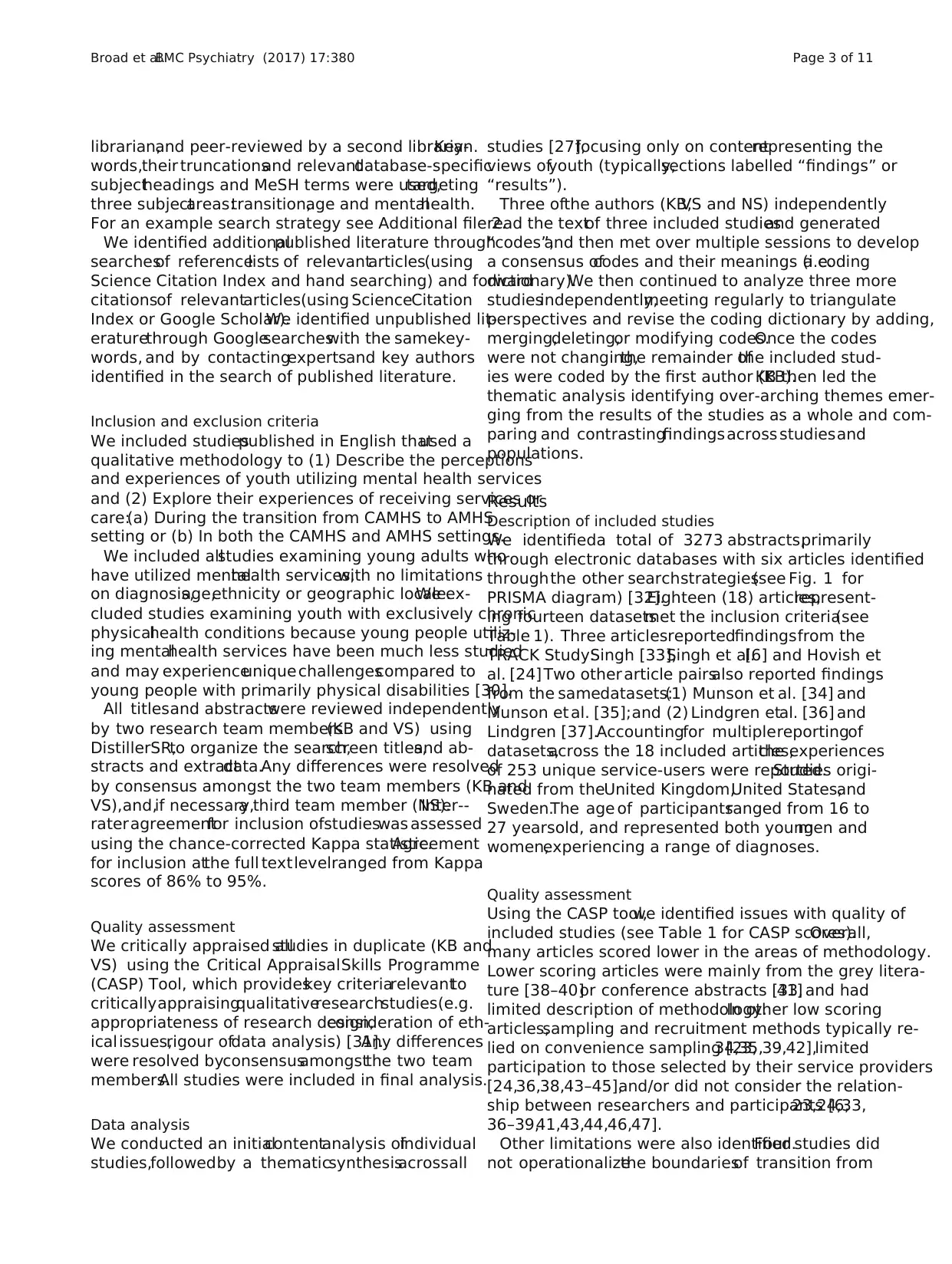

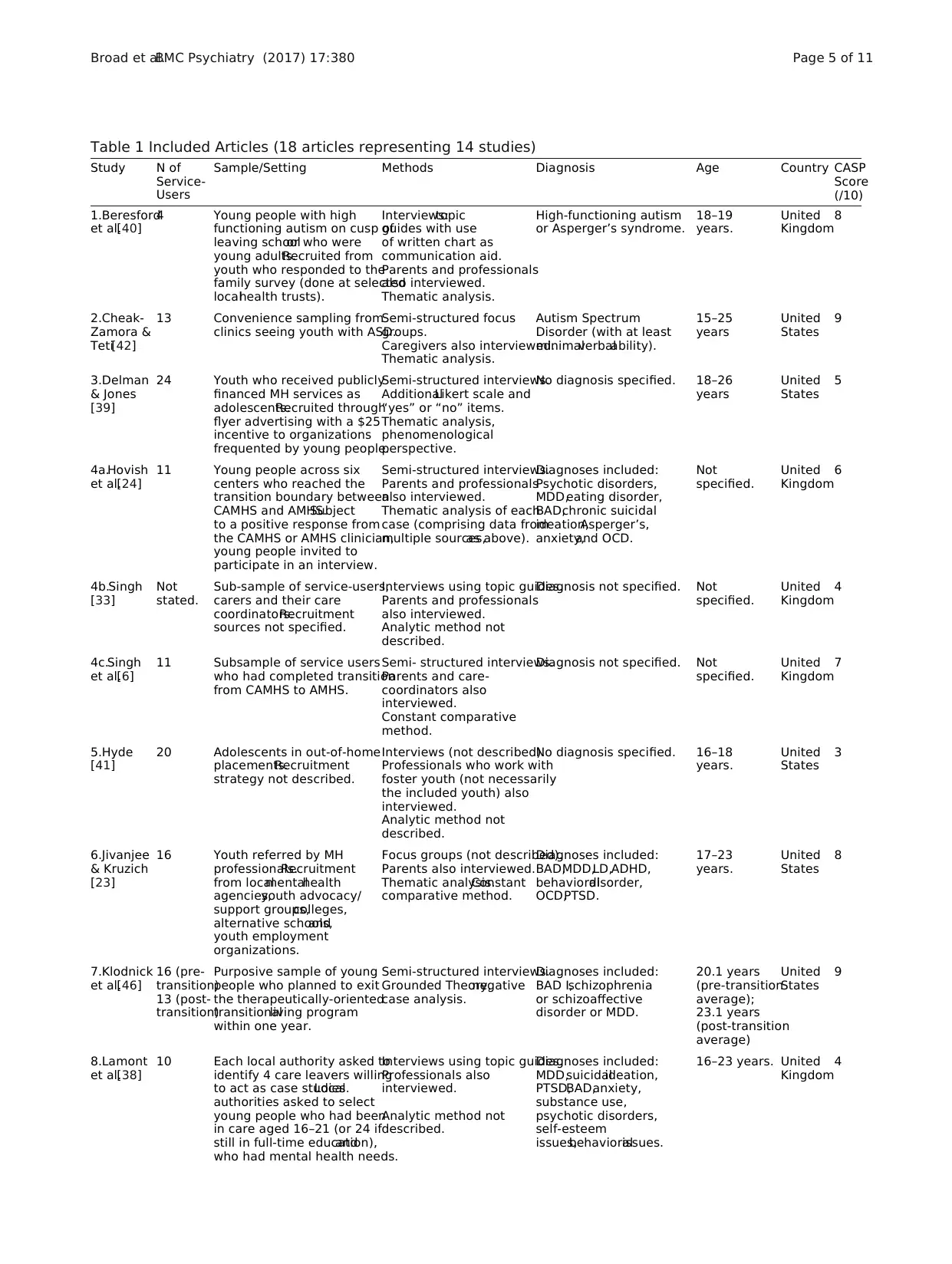

We identifieda total of 3273 abstracts,primarily

through electronic databases with six articles identified

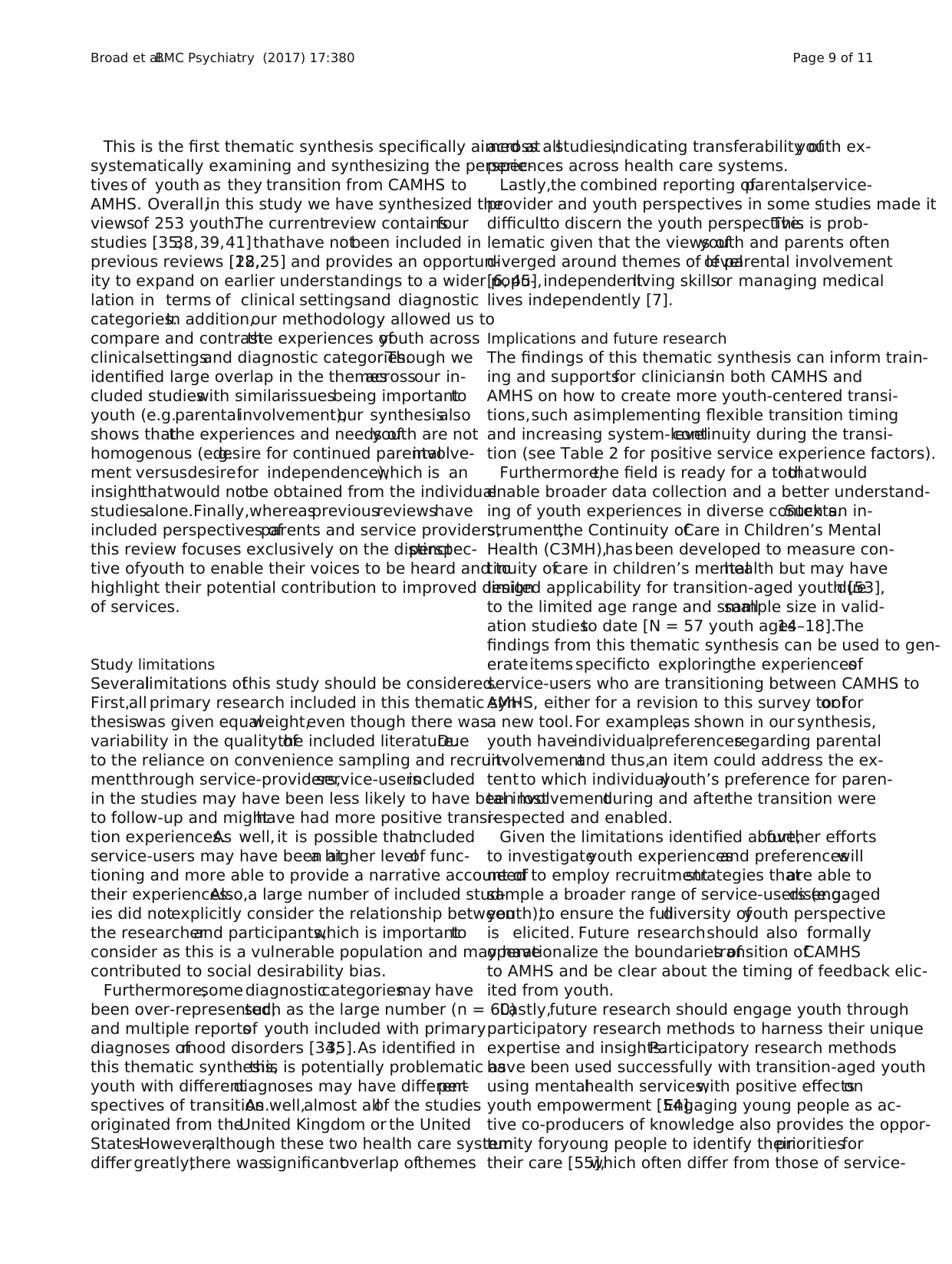

throughthe other searchstrategies(see Fig. 1 for

PRISMA diagram) [32].Eighteen (18) articles,represent-

ing fourteen datasetsmet the inclusion criteria(see

Table 1). Three articlesreportedfindingsfrom the

TRACK Study:Singh [33],Singh et al.[6] and Hovish et

al. [24] Two other article pairsalso reported findings

from the samedatasets:(1) Munson et al. [34] and

Munson et al. [35];and (2) Lindgren etal. [36] and

Lindgren [37].Accountingfor multiplereportingof

datasets,across the 18 included articles,the experiences

of 253 unique service-users were reported.Studies origi-

nated from theUnited Kingdom,United States,and

Sweden.The age of participantsranged from 16 to

27 yearsold, and represented both youngmen and

women,experiencing a range of diagnoses.

Quality assessment

Using the CASP tool,we identified issues with quality of

included studies (see Table 1 for CASP scores).Overall,

many articles scored lower in the areas of methodology.

Lower scoring articles were mainly from the grey litera-

ture [38–40]or conference abstracts [33,41] and had

limited description of methodology.In other low scoring

articles,sampling and recruitment methods typically re-

lied on convenience sampling [23,34,35,39,42],limited

participation to those selected by their service providers

[24,36,38,43–45],and/or did not consider the relation-

ship between researchers and participants [6,23,24,33,

36–39,41,43,44,46,47].

Other limitations were also identified.Four studies did

not operationalizethe boundariesof transition from

Broad et al.BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380 Page 3 of 11

words,their truncationsand relevantdatabase-specific

subjectheadings and MeSH terms were used,targeting

three subjectareas:transition,age and mentalhealth.

For an example search strategy see Additional file 2.

We identified additionalpublished literature through

searchesof referencelists of relevantarticles(using

Science Citation Index and hand searching) and forward

citationsof relevantarticles(using ScienceCitation

Index or Google Scholar).We identified unpublished lit-

eraturethrough Googlesearcheswith the samekey-

words, and by contactingexpertsand key authors

identified in the search of published literature.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included studiespublished in English thatused a

qualitative methodology to (1) Describe the perceptions

and experiences of youth utilizing mental health services

and (2) Explore their experiences of receiving services or

care:(a) During the transition from CAMHS to AMHS

setting or (b) In both the CAMHS and AMHS settings.

We included allstudies examining young adults who

have utilized mentalhealth services,with no limitations

on diagnosis,age,ethnicity or geographic locale.We ex-

cluded studies examining youth with exclusively chronic

physicalhealth conditions because young people utiliz-

ing mentalhealth services have been much less studied

and may experienceunique challengescompared to

young people with primarily physical disabilities [30].

All titlesand abstractswere reviewed independently

by two research team members(KB and VS) using

DistillerSR,to organize the search,screen titles,and ab-

stracts and extractdata.Any differences were resolved

by consensus amongst the two team members (KB and

VS),and,if necessary,a third team member (NS).Inter--

rateragreementfor inclusion ofstudieswas assessed

using the chance-corrected Kappa statistic.Agreement

for inclusion atthe full textlevelranged from Kappa

scores of 86% to 95%.

Quality assessment

We critically appraised allstudies in duplicate (KB and

VS) using the Critical AppraisalSkills Programme

(CASP) Tool, which provideskey criteriarelevantto

criticallyappraisingqualitativeresearchstudies(e.g.

appropriateness of research design,consideration of eth-

icalissues,rigour ofdata analysis) [31].Any differences

were resolved byconsensusamongstthe two team

members.All studies were included in final analysis.

Data analysis

We conducted an initialcontentanalysis ofindividual

studies,followedby a thematicsynthesisacrossall

studies [27],focusing only on contentrepresenting the

views ofyouth (typically,sections labelled “findings” or

“results”).

Three ofthe authors (KB,VS and NS) independently

read the textof three included studiesand generated

“codes”,and then met over multiple sessions to develop

a consensus ofcodes and their meanings (i.e.a coding

dictionary).We then continued to analyze three more

studiesindependently,meeting regularly to triangulate

perspectives and revise the coding dictionary by adding,

merging,deleting,or modifying codes.Once the codes

were not changing,the remainder ofthe included stud-

ies were coded by the first author (KB).KB then led the

thematic analysis identifying over-arching themes emer-

ging from the results of the studies as a whole and com-

paring and contrastingfindings across studiesand

populations.

Results

Description of included studies

We identifieda total of 3273 abstracts,primarily

through electronic databases with six articles identified

throughthe other searchstrategies(see Fig. 1 for

PRISMA diagram) [32].Eighteen (18) articles,represent-

ing fourteen datasetsmet the inclusion criteria(see

Table 1). Three articlesreportedfindingsfrom the

TRACK Study:Singh [33],Singh et al.[6] and Hovish et

al. [24] Two other article pairsalso reported findings

from the samedatasets:(1) Munson et al. [34] and

Munson et al. [35];and (2) Lindgren etal. [36] and

Lindgren [37].Accountingfor multiplereportingof

datasets,across the 18 included articles,the experiences

of 253 unique service-users were reported.Studies origi-

nated from theUnited Kingdom,United States,and

Sweden.The age of participantsranged from 16 to

27 yearsold, and represented both youngmen and

women,experiencing a range of diagnoses.

Quality assessment

Using the CASP tool,we identified issues with quality of

included studies (see Table 1 for CASP scores).Overall,

many articles scored lower in the areas of methodology.

Lower scoring articles were mainly from the grey litera-

ture [38–40]or conference abstracts [33,41] and had

limited description of methodology.In other low scoring

articles,sampling and recruitment methods typically re-

lied on convenience sampling [23,34,35,39,42],limited

participation to those selected by their service providers

[24,36,38,43–45],and/or did not consider the relation-

ship between researchers and participants [6,23,24,33,

36–39,41,43,44,46,47].

Other limitations were also identified.Four studies did

not operationalizethe boundariesof transition from

Broad et al.BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380 Page 3 of 11

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

CAMHS to AMHS and the timing ofinterviewswith

youth was often unclear [23,38,41,42],making it un-

clear how much exposure youth had to AMHS.Further-

more,in studies that also examined parent,caregiver or

professionalviews,three studieslinked parentaland

youth views together in the discussion of themes [6,24,

44].To keep this thematic analysis in line with views of

youth,only findings indicated as originating from youth

were used in analysis.

Thematic foci

Three thematic fociemerged from the thematic synthe-

sis: (1) Complex Interplayof Multiple Concurrent

Transitions (2)Balancing Autonomy and the Need for

Supports and (3)Factors Impacting Youth Experiences

of Transition.

Complex interplay of multiple concurrent transitions

On the path to becoming an adult,young people experi-

ence multipletransitionsin a varietyof domainsin

addition to the transition from CAMHS to AMHS,such

as change in levelof parentalinvolvement,life events,

and community agency involvement.For some youth,

these transitionswere a majorobstacle forcontinued

mentalhealth service use,such as described by a youth

interviewed by Sakai et al.:

“I didn’t even get no Medicaid when I left foster care.I

had it but,it was never mailed to me.I didn’t even have

an address.” [43],p6.

In contrast,for some,life transitions,such as becom-

ing a parent,were a way for young people to become re-

engagedin mental health servicesas describedin

Munson et al.[35]:

“…and shortly after she was born Ihad talked to the

doctor about postpartum depression… I’m like ‘…I don’t

want to get out ofbed… I don’t want to do nothing’… He

was like ‘Wellyou could be having postpartum depres-

sion,’and that’s when allof my childhood mentalprob-

lems came up,because he had accessed my information

from my old doctor… he’s like ‘Wellyou know you need

to be on this medication…’” [pg 3].

As youth prepared to undergo major life transitions,

some voiced worries about the overlap of these

changes with their mentalhealth care transition.The

interplayof thesetransitionsmadesome feel more

vulnerable,especiallyas they sensed theimpact of

diminishing supports:

“I turn 18 in like 2 weeks,and I want to move out and

live on my own,but it is going to be hard for me because

once Iturn 18,the supports thatI have,some ofthem

are going to disappear.... I am going to have to be able

to dealwith my issues on my own and find other sup-

ports.” [23,p 11].

Fig. 1 PRISMA diagram

Broad et al.BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380 Page 4 of 11

youth was often unclear [23,38,41,42],making it un-

clear how much exposure youth had to AMHS.Further-

more,in studies that also examined parent,caregiver or

professionalviews,three studieslinked parentaland

youth views together in the discussion of themes [6,24,

44].To keep this thematic analysis in line with views of

youth,only findings indicated as originating from youth

were used in analysis.

Thematic foci

Three thematic fociemerged from the thematic synthe-

sis: (1) Complex Interplayof Multiple Concurrent

Transitions (2)Balancing Autonomy and the Need for

Supports and (3)Factors Impacting Youth Experiences

of Transition.

Complex interplay of multiple concurrent transitions

On the path to becoming an adult,young people experi-

ence multipletransitionsin a varietyof domainsin

addition to the transition from CAMHS to AMHS,such

as change in levelof parentalinvolvement,life events,

and community agency involvement.For some youth,

these transitionswere a majorobstacle forcontinued

mentalhealth service use,such as described by a youth

interviewed by Sakai et al.:

“I didn’t even get no Medicaid when I left foster care.I

had it but,it was never mailed to me.I didn’t even have

an address.” [43],p6.

In contrast,for some,life transitions,such as becom-

ing a parent,were a way for young people to become re-

engagedin mental health servicesas describedin

Munson et al.[35]:

“…and shortly after she was born Ihad talked to the

doctor about postpartum depression… I’m like ‘…I don’t

want to get out ofbed… I don’t want to do nothing’… He

was like ‘Wellyou could be having postpartum depres-

sion,’and that’s when allof my childhood mentalprob-

lems came up,because he had accessed my information

from my old doctor… he’s like ‘Wellyou know you need

to be on this medication…’” [pg 3].

As youth prepared to undergo major life transitions,

some voiced worries about the overlap of these

changes with their mentalhealth care transition.The

interplayof thesetransitionsmadesome feel more

vulnerable,especiallyas they sensed theimpact of

diminishing supports:

“I turn 18 in like 2 weeks,and I want to move out and

live on my own,but it is going to be hard for me because

once Iturn 18,the supports thatI have,some ofthem

are going to disappear.... I am going to have to be able

to dealwith my issues on my own and find other sup-

ports.” [23,p 11].

Fig. 1 PRISMA diagram

Broad et al.BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380 Page 4 of 11

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

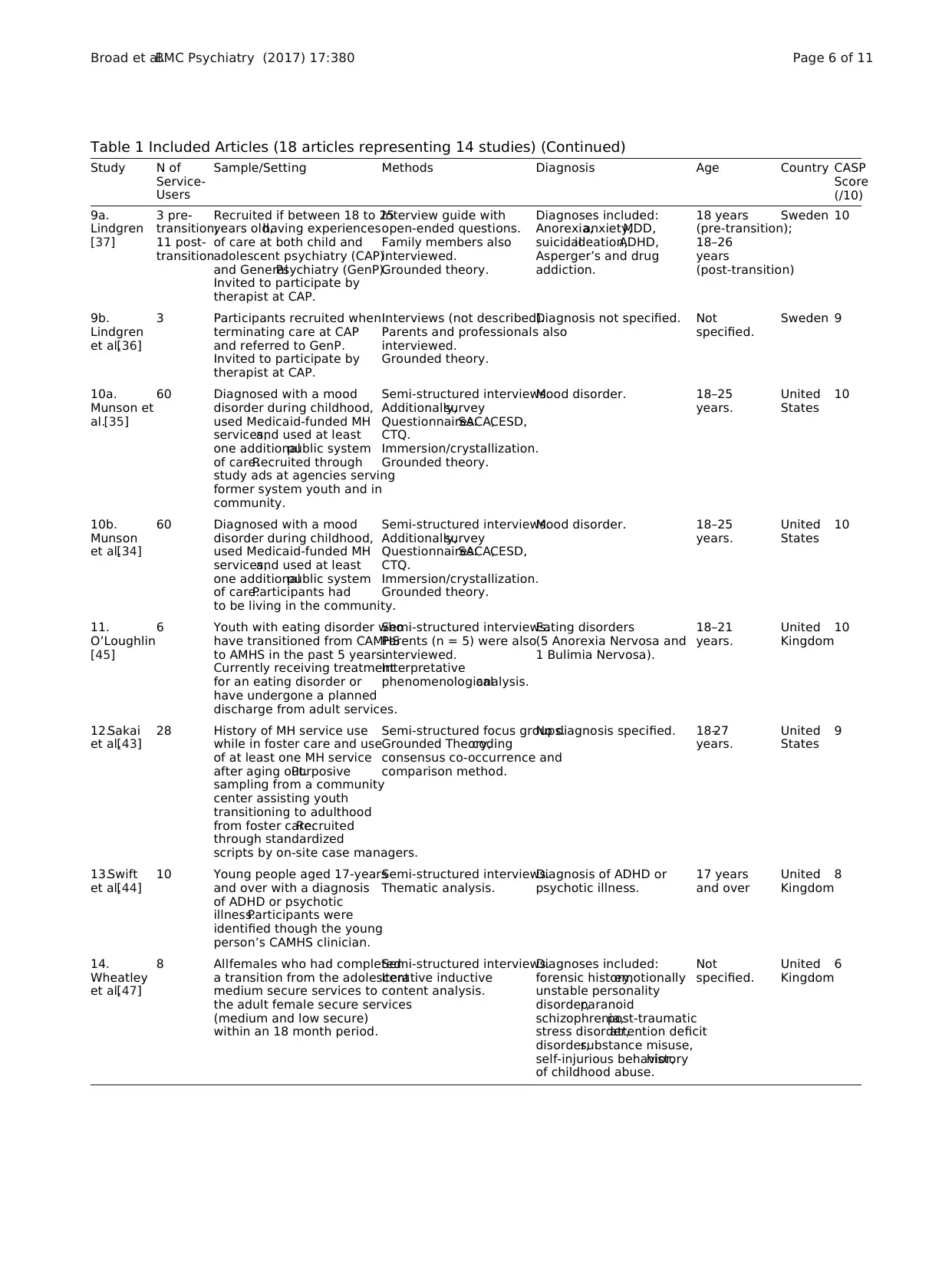

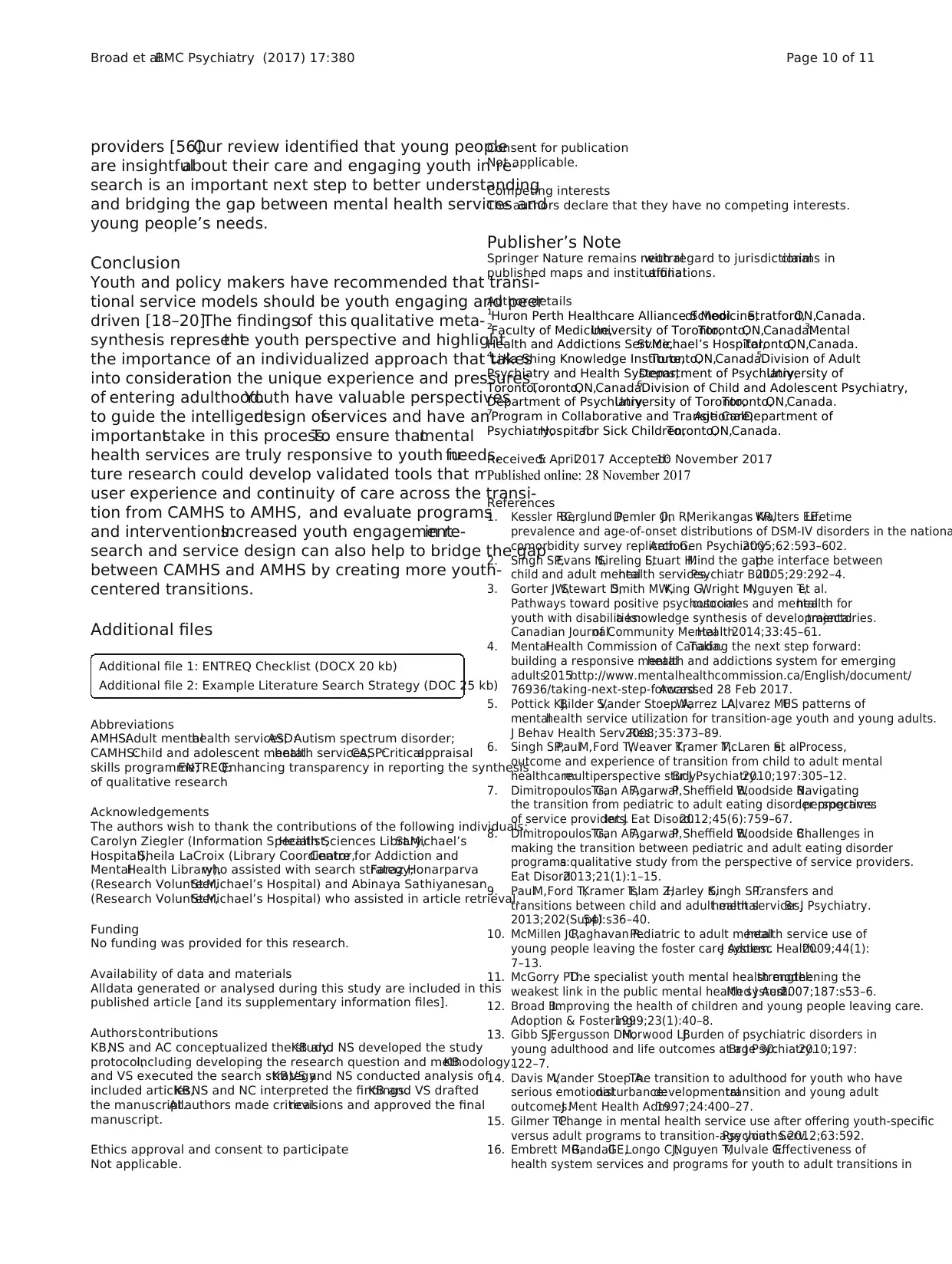

Table 1 Included Articles (18 articles representing 14 studies)

Study N of

Service-

Users

Sample/Setting Methods Diagnosis Age Country CASP

Score

(/10)

1.Beresford

et al.[40]

4 Young people with high

functioning autism on cusp of

leaving schoolor who were

young adults.Recruited from

youth who responded to the

family survey (done at selected

localhealth trusts).

Interviews:topic

guides with use

of written chart as

communication aid.

Parents and professionals

also interviewed.

Thematic analysis.

High-functioning autism

or Asperger’s syndrome.

18–19

years.

United

Kingdom

8

2.Cheak-

Zamora &

Teti[42]

13 Convenience sampling from

clinics seeing youth with ASD.

Semi-structured focus

groups.

Caregivers also interviewed.

Thematic analysis.

Autism Spectrum

Disorder (with at least

minimalverbalability).

15–25

years

United

States

9

3.Delman

& Jones

[39]

24 Youth who received publicly

financed MH services as

adolescents.Recruited through

flyer advertising with a $25

incentive to organizations

frequented by young people.

Semi-structured interviews.

AdditionalLikert scale and

“yes” or “no” items.

Thematic analysis,

phenomenological

perspective.

No diagnosis specified. 18–26

years

United

States

5

4a.Hovish

et al.[24]

11 Young people across six

centers who reached the

transition boundary between

CAMHS and AMHS.Subject

to a positive response from

the CAMHS or AMHS clinician,

young people invited to

participate in an interview.

Semi-structured interviews.

Parents and professionals

also interviewed.

Thematic analysis of each

case (comprising data from

multiple sources,as above).

Diagnoses included:

Psychotic disorders,

MDD,eating disorder,

BAD,chronic suicidal

ideation,Asperger’s,

anxiety,and OCD.

Not

specified.

United

Kingdom

6

4b.Singh

[33]

Not

stated.

Sub-sample of service-users,

carers and their care

coordinators.Recruitment

sources not specified.

Interviews using topic guides.

Parents and professionals

also interviewed.

Analytic method not

described.

Diagnosis not specified. Not

specified.

United

Kingdom

4

4c.Singh

et al.[6]

11 Subsample of service users

who had completed transition

from CAMHS to AMHS.

Semi- structured interviews.

Parents and care-

coordinators also

interviewed.

Constant comparative

method.

Diagnosis not specified. Not

specified.

United

Kingdom

7

5.Hyde

[41]

20 Adolescents in out-of-home

placements.Recruitment

strategy not described.

Interviews (not described).

Professionals who work with

foster youth (not necessarily

the included youth) also

interviewed.

Analytic method not

described.

No diagnosis specified. 16–18

years.

United

States

3

6.Jivanjee

& Kruzich

[23]

16 Youth referred by MH

professionals.Recruitment

from localmentalhealth

agencies,youth advocacy/

support groups,colleges,

alternative schools,and

youth employment

organizations.

Focus groups (not described).

Parents also interviewed.

Thematic analysis.Constant

comparative method.

Diagnoses included:

BAD,MDD,LD,ADHD,

behavioraldisorder,

OCD,PTSD.

17–23

years.

United

States

8

7.Klodnick

et al.[46]

16 (pre-

transition)

13 (post-

transition)

Purposive sample of young

people who planned to exit

the therapeutically-oriented

transitionalliving program

within one year.

Semi-structured interviews.

Grounded Theory,negative

case analysis.

Diagnoses included:

BAD I,schizophrenia

or schizoaffective

disorder or MDD.

20.1 years

(pre-transition

average);

23.1 years

(post-transition

average)

United

States

9

8.Lamont

et al.[38]

10 Each local authority asked to

identify 4 care leavers willing

to act as case studies.Local

authorities asked to select

young people who had been

in care aged 16–21 (or 24 if

still in full-time education),and

who had mental health needs.

Interviews using topic guides.

Professionals also

interviewed.

Analytic method not

described.

Diagnoses included:

MDD,suicidalideation,

PTSD,BAD,anxiety,

substance use,

psychotic disorders,

self-esteem

issues,behavioralissues.

16–23 years. United

Kingdom

4

Broad et al.BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380 Page 5 of 11

Study N of

Service-

Users

Sample/Setting Methods Diagnosis Age Country CASP

Score

(/10)

1.Beresford

et al.[40]

4 Young people with high

functioning autism on cusp of

leaving schoolor who were

young adults.Recruited from

youth who responded to the

family survey (done at selected

localhealth trusts).

Interviews:topic

guides with use

of written chart as

communication aid.

Parents and professionals

also interviewed.

Thematic analysis.

High-functioning autism

or Asperger’s syndrome.

18–19

years.

United

Kingdom

8

2.Cheak-

Zamora &

Teti[42]

13 Convenience sampling from

clinics seeing youth with ASD.

Semi-structured focus

groups.

Caregivers also interviewed.

Thematic analysis.

Autism Spectrum

Disorder (with at least

minimalverbalability).

15–25

years

United

States

9

3.Delman

& Jones

[39]

24 Youth who received publicly

financed MH services as

adolescents.Recruited through

flyer advertising with a $25

incentive to organizations

frequented by young people.

Semi-structured interviews.

AdditionalLikert scale and

“yes” or “no” items.

Thematic analysis,

phenomenological

perspective.

No diagnosis specified. 18–26

years

United

States

5

4a.Hovish

et al.[24]

11 Young people across six

centers who reached the

transition boundary between

CAMHS and AMHS.Subject

to a positive response from

the CAMHS or AMHS clinician,

young people invited to

participate in an interview.

Semi-structured interviews.

Parents and professionals

also interviewed.

Thematic analysis of each

case (comprising data from

multiple sources,as above).

Diagnoses included:

Psychotic disorders,

MDD,eating disorder,

BAD,chronic suicidal

ideation,Asperger’s,

anxiety,and OCD.

Not

specified.

United

Kingdom

6

4b.Singh

[33]

Not

stated.

Sub-sample of service-users,

carers and their care

coordinators.Recruitment

sources not specified.

Interviews using topic guides.

Parents and professionals

also interviewed.

Analytic method not

described.

Diagnosis not specified. Not

specified.

United

Kingdom

4

4c.Singh

et al.[6]

11 Subsample of service users

who had completed transition

from CAMHS to AMHS.

Semi- structured interviews.

Parents and care-

coordinators also

interviewed.

Constant comparative

method.

Diagnosis not specified. Not

specified.

United

Kingdom

7

5.Hyde

[41]

20 Adolescents in out-of-home

placements.Recruitment

strategy not described.

Interviews (not described).

Professionals who work with

foster youth (not necessarily

the included youth) also

interviewed.

Analytic method not

described.

No diagnosis specified. 16–18

years.

United

States

3

6.Jivanjee

& Kruzich

[23]

16 Youth referred by MH

professionals.Recruitment

from localmentalhealth

agencies,youth advocacy/

support groups,colleges,

alternative schools,and

youth employment

organizations.

Focus groups (not described).

Parents also interviewed.

Thematic analysis.Constant

comparative method.

Diagnoses included:

BAD,MDD,LD,ADHD,

behavioraldisorder,

OCD,PTSD.

17–23

years.

United

States

8

7.Klodnick

et al.[46]

16 (pre-

transition)

13 (post-

transition)

Purposive sample of young

people who planned to exit

the therapeutically-oriented

transitionalliving program

within one year.

Semi-structured interviews.

Grounded Theory,negative

case analysis.

Diagnoses included:

BAD I,schizophrenia

or schizoaffective

disorder or MDD.

20.1 years

(pre-transition

average);

23.1 years

(post-transition

average)

United

States

9

8.Lamont

et al.[38]

10 Each local authority asked to

identify 4 care leavers willing

to act as case studies.Local

authorities asked to select

young people who had been

in care aged 16–21 (or 24 if

still in full-time education),and

who had mental health needs.

Interviews using topic guides.

Professionals also

interviewed.

Analytic method not

described.

Diagnoses included:

MDD,suicidalideation,

PTSD,BAD,anxiety,

substance use,

psychotic disorders,

self-esteem

issues,behavioralissues.

16–23 years. United

Kingdom

4

Broad et al.BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380 Page 5 of 11

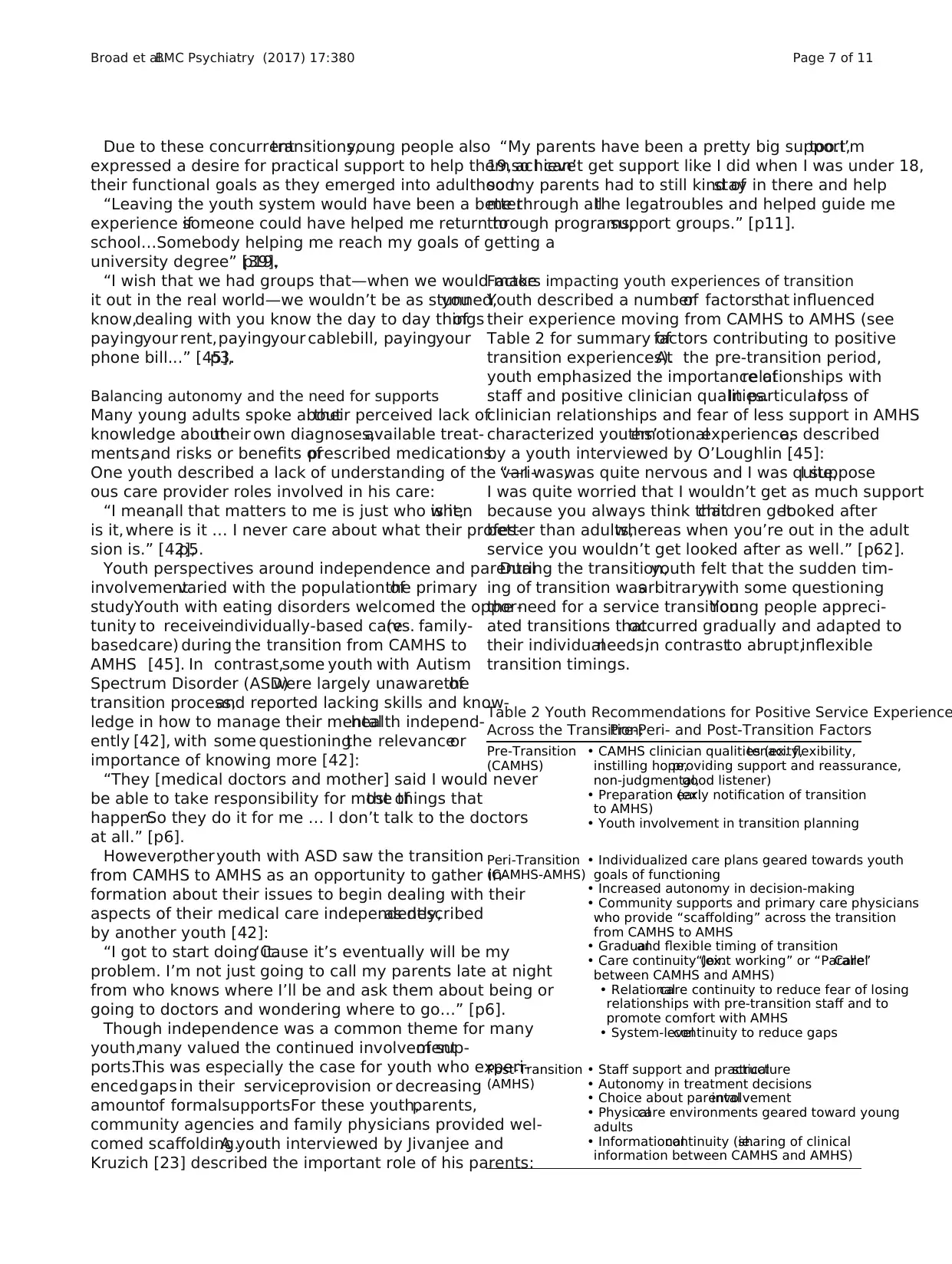

Table 1 Included Articles (18 articles representing 14 studies) (Continued)

Study N of

Service-

Users

Sample/Setting Methods Diagnosis Age Country CASP

Score

(/10)

9a.

Lindgren

[37]

3 pre-

transition;

11 post-

transition

Recruited if between 18 to 25

years old,having experiences

of care at both child and

adolescent psychiatry (CAP)

and GeneralPsychiatry (GenP).

Invited to participate by

therapist at CAP.

Interview guide with

open-ended questions.

Family members also

interviewed.

Grounded theory.

Diagnoses included:

Anorexia,anxiety,MDD,

suicidalideation,ADHD,

Asperger’s and drug

addiction.

18 years

(pre-transition);

18–26

years

(post-transition)

Sweden 10

9b.

Lindgren

et al.[36]

3 Participants recruited when

terminating care at CAP

and referred to GenP.

Invited to participate by

therapist at CAP.

Interviews (not described).

Parents and professionals also

interviewed.

Grounded theory.

Diagnosis not specified. Not

specified.

Sweden 9

10a.

Munson et

al.[35]

60 Diagnosed with a mood

disorder during childhood,

used Medicaid-funded MH

services,and used at least

one additionalpublic system

of care.Recruited through

study ads at agencies serving

former system youth and in

community.

Semi-structured interviews.

Additionally,survey

Questionnaires:SACA,CESD,

CTQ.

Immersion/crystallization.

Grounded theory.

Mood disorder. 18–25

years.

United

States

10

10b.

Munson

et al.[34]

60 Diagnosed with a mood

disorder during childhood,

used Medicaid-funded MH

services,and used at least

one additionalpublic system

of care.Participants had

to be living in the community.

Semi-structured interviews.

Additionally,survey

Questionnaires:SACA,CESD,

CTQ.

Immersion/crystallization.

Grounded theory.

Mood disorder. 18–25

years.

United

States

10

11.

O’Loughlin

[45]

6 Youth with eating disorder who

have transitioned from CAMHS

to AMHS in the past 5 years.

Currently receiving treatment

for an eating disorder or

have undergone a planned

discharge from adult services.

Semi-structured interviews.

Parents (n = 5) were also

interviewed.

Interpretative

phenomenologicalanalysis.

Eating disorders

(5 Anorexia Nervosa and

1 Bulimia Nervosa).

18–21

years.

United

Kingdom

10

12.Sakai

et al.[43]

28 History of MH service use

while in foster care and use

of at least one MH service

after aging out.Purposive

sampling from a community

center assisting youth

transitioning to adulthood

from foster care.Recruited

through standardized

scripts by on-site case managers.

Semi-structured focus groups.

Grounded Theory,coding

consensus co-occurrence and

comparison method.

No diagnosis specified. 18–27

years.

United

States

9

13.Swift

et al.[44]

10 Young people aged 17-years

and over with a diagnosis

of ADHD or psychotic

illness.Participants were

identified though the young

person’s CAMHS clinician.

Semi-structured interviews.

Thematic analysis.

Diagnosis of ADHD or

psychotic illness.

17 years

and over

United

Kingdom

8

14.

Wheatley

et al.[47]

8 Allfemales who had completed

a transition from the adolescent

medium secure services to

the adult female secure services

(medium and low secure)

within an 18 month period.

Semi-structured interviews.

Iterative inductive

content analysis.

Diagnoses included:

forensic history,emotionally

unstable personality

disorder,paranoid

schizophrenia,post-traumatic

stress disorder,attention deficit

disorder,substance misuse,

self-injurious behavior,history

of childhood abuse.

Not

specified.

United

Kingdom

6

Broad et al.BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380 Page 6 of 11

Study N of

Service-

Users

Sample/Setting Methods Diagnosis Age Country CASP

Score

(/10)

9a.

Lindgren

[37]

3 pre-

transition;

11 post-

transition

Recruited if between 18 to 25

years old,having experiences

of care at both child and

adolescent psychiatry (CAP)

and GeneralPsychiatry (GenP).

Invited to participate by

therapist at CAP.

Interview guide with

open-ended questions.

Family members also

interviewed.

Grounded theory.

Diagnoses included:

Anorexia,anxiety,MDD,

suicidalideation,ADHD,

Asperger’s and drug

addiction.

18 years

(pre-transition);

18–26

years

(post-transition)

Sweden 10

9b.

Lindgren

et al.[36]

3 Participants recruited when

terminating care at CAP

and referred to GenP.

Invited to participate by

therapist at CAP.

Interviews (not described).

Parents and professionals also

interviewed.

Grounded theory.

Diagnosis not specified. Not

specified.

Sweden 9

10a.

Munson et

al.[35]

60 Diagnosed with a mood

disorder during childhood,

used Medicaid-funded MH

services,and used at least

one additionalpublic system

of care.Recruited through

study ads at agencies serving

former system youth and in

community.

Semi-structured interviews.

Additionally,survey

Questionnaires:SACA,CESD,

CTQ.

Immersion/crystallization.

Grounded theory.

Mood disorder. 18–25

years.

United

States

10

10b.

Munson

et al.[34]

60 Diagnosed with a mood

disorder during childhood,

used Medicaid-funded MH

services,and used at least

one additionalpublic system

of care.Participants had

to be living in the community.

Semi-structured interviews.

Additionally,survey

Questionnaires:SACA,CESD,

CTQ.

Immersion/crystallization.

Grounded theory.

Mood disorder. 18–25

years.

United

States

10

11.

O’Loughlin

[45]

6 Youth with eating disorder who

have transitioned from CAMHS

to AMHS in the past 5 years.

Currently receiving treatment

for an eating disorder or

have undergone a planned

discharge from adult services.

Semi-structured interviews.

Parents (n = 5) were also

interviewed.

Interpretative

phenomenologicalanalysis.

Eating disorders

(5 Anorexia Nervosa and

1 Bulimia Nervosa).

18–21

years.

United

Kingdom

10

12.Sakai

et al.[43]

28 History of MH service use

while in foster care and use

of at least one MH service

after aging out.Purposive

sampling from a community

center assisting youth

transitioning to adulthood

from foster care.Recruited

through standardized

scripts by on-site case managers.

Semi-structured focus groups.

Grounded Theory,coding

consensus co-occurrence and

comparison method.

No diagnosis specified. 18–27

years.

United

States

9

13.Swift

et al.[44]

10 Young people aged 17-years

and over with a diagnosis

of ADHD or psychotic

illness.Participants were

identified though the young

person’s CAMHS clinician.

Semi-structured interviews.

Thematic analysis.

Diagnosis of ADHD or

psychotic illness.

17 years

and over

United

Kingdom

8

14.

Wheatley

et al.[47]

8 Allfemales who had completed

a transition from the adolescent

medium secure services to

the adult female secure services

(medium and low secure)

within an 18 month period.

Semi-structured interviews.

Iterative inductive

content analysis.

Diagnoses included:

forensic history,emotionally

unstable personality

disorder,paranoid

schizophrenia,post-traumatic

stress disorder,attention deficit

disorder,substance misuse,

self-injurious behavior,history

of childhood abuse.

Not

specified.

United

Kingdom

6

Broad et al.BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380 Page 6 of 11

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Due to these concurrenttransitions,young people also

expressed a desire for practical support to help them achieve

their functional goals as they emerged into adulthood.

“Leaving the youth system would have been a better

experience ifsomeone could have helped me return to

school…Somebody helping me reach my goals of getting a

university degree” [39],p19.

“I wish that we had groups that—when we would make

it out in the real world—we wouldn’t be as stunned,you

know,dealing with you know the day to day thingsof

payingyour rent,payingyour cablebill, payingyour

phone bill...” [45],p3.

Balancing autonomy and the need for supports

Many young adults spoke abouttheir perceived lack of

knowledge abouttheir own diagnoses,available treat-

ments,and risks or benefits ofprescribed medications.

One youth described a lack of understanding of the vari-

ous care provider roles involved in his care:

“I mean,all that matters to me is just who is it,when

is it, where is it … I never care about what their profes-

sion is.” [42],p5.

Youth perspectives around independence and parental

involvementvaried with the population ofthe primary

study.Youth with eating disorders welcomed the oppor-

tunity to receiveindividually-based care(vs. family-

basedcare) during the transition from CAMHS to

AMHS [45]. In contrast,some youth with Autism

Spectrum Disorder (ASD)were largely unaware ofthe

transition process,and reported lacking skills and know-

ledge in how to manage their mentalhealth independ-

ently [42], with some questioningthe relevanceor

importance of knowing more [42]:

“They [medical doctors and mother] said I would never

be able to take responsibility for most ofthe things that

happen.So they do it for me … I don’t talk to the doctors

at all.” [p6].

However,other youth with ASD saw the transition

from CAMHS to AMHS as an opportunity to gather in-

formation about their issues to begin dealing with their

aspects of their medical care independently,as described

by another youth [42]:

“I got to start doing it.‘Cause it’s eventually will be my

problem. I’m not just going to call my parents late at night

from who knows where I’ll be and ask them about being or

going to doctors and wondering where to go…” [p6].

Though independence was a common theme for many

youth,many valued the continued involvementof sup-

ports.This was especially the case for youth who experi-

encedgaps in their serviceprovision or decreasing

amountof formalsupports.For these youth,parents,

community agencies and family physicians provided wel-

comed scaffolding.A youth interviewed by Jivanjee and

Kruzich [23] described the important role of his parents:

“My parents have been a pretty big support,too.I’m

19,so I can’t get support like I did when I was under 18,

so my parents had to still kind ofstay in there and help

me through allthe legaltroubles and helped guide me

through programs,support groups.” [p11].

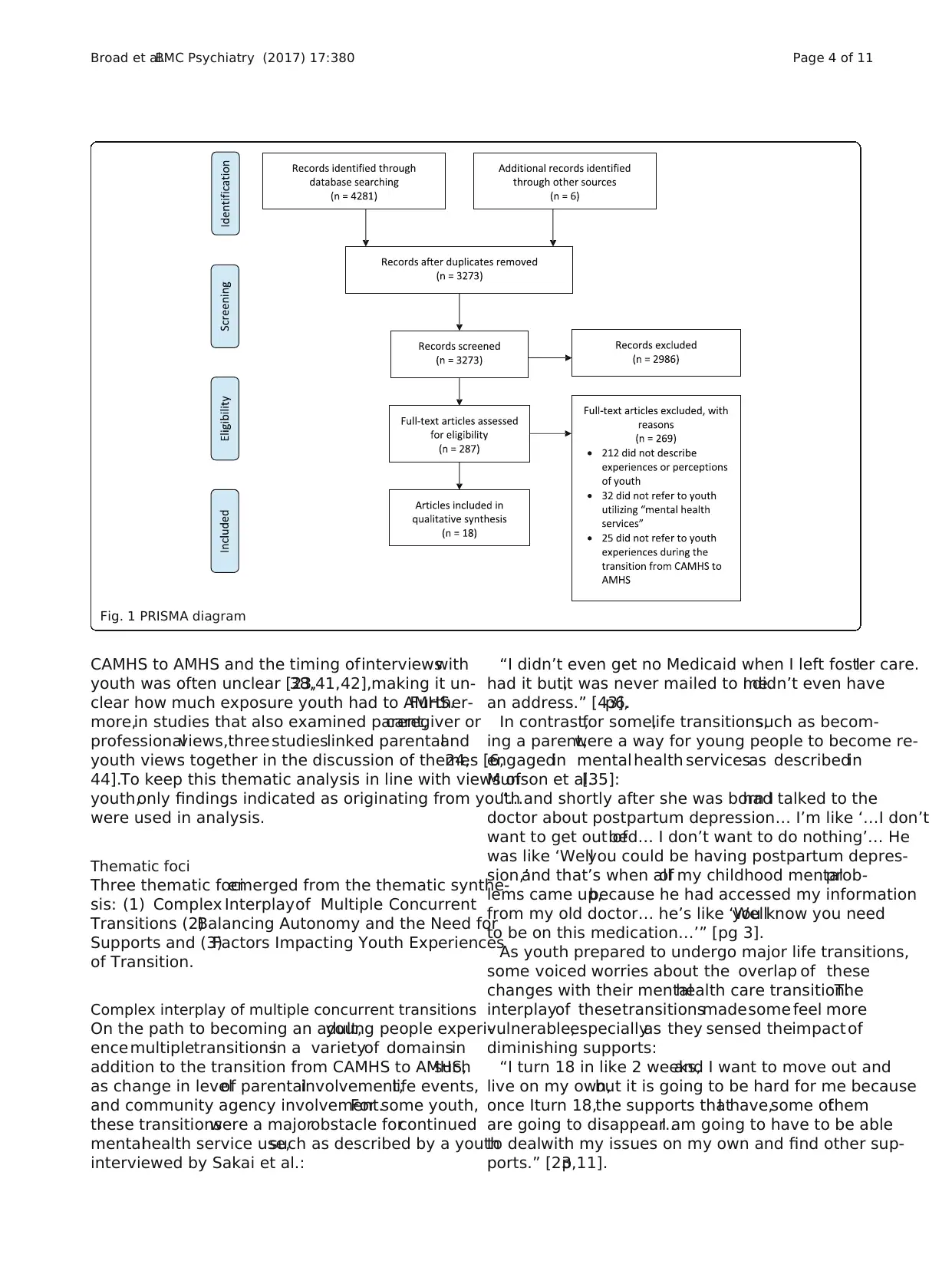

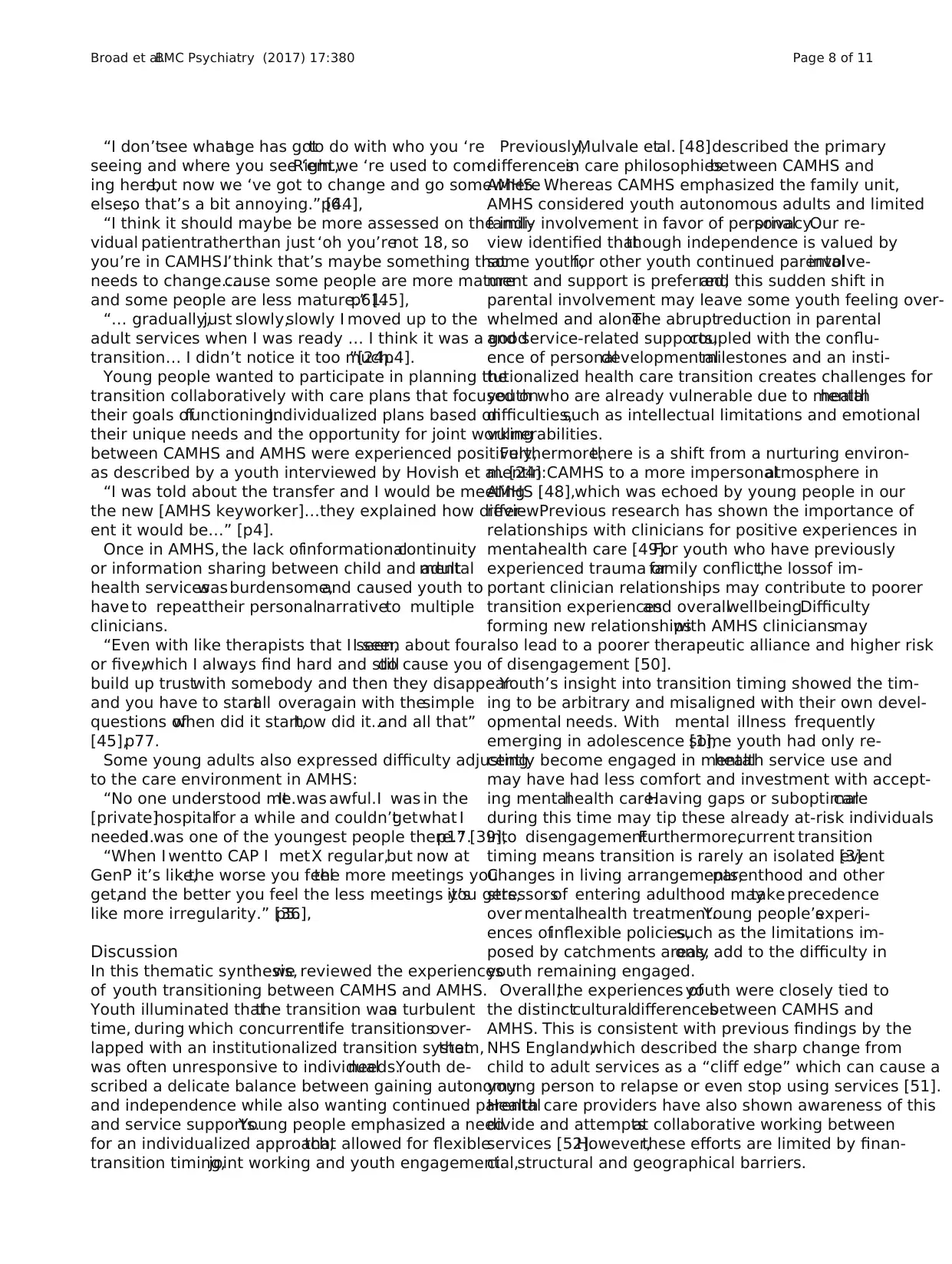

Factors impacting youth experiences of transition

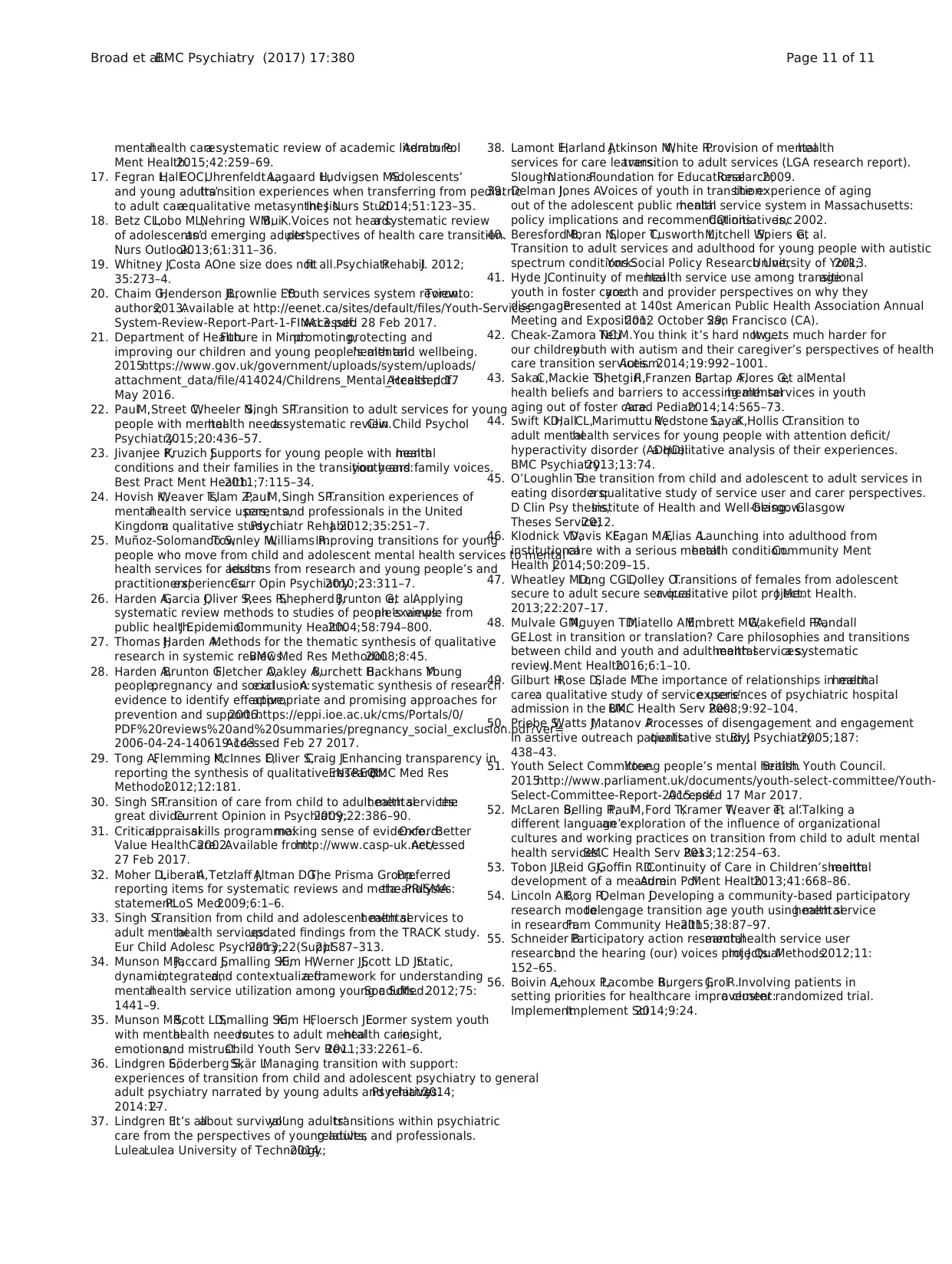

Youth described a numberof factorsthat influenced

their experience moving from CAMHS to AMHS (see

Table 2 for summary offactors contributing to positive

transition experiences).At the pre-transition period,

youth emphasized the importance ofrelationships with

staff and positive clinician qualities.In particular,loss of

clinician relationships and fear of less support in AMHS

characterized youths’emotionalexperience,as described

by a youth interviewed by O’Loughlin [45]:

“—I was,was quite nervous and I was quite,I suppose

I was quite worried that I wouldn’t get as much support

because you always think thatchildren getlooked after

better than adults,whereas when you’re out in the adult

service you wouldn’t get looked after as well.” [p62].

During the transition,youth felt that the sudden tim-

ing of transition wasarbitrary,with some questioning

the need for a service transition.Young people appreci-

ated transitions thatoccurred gradually and adapted to

their individualneeds,in contrastto abrupt,inflexible

transition timings.

Table 2 Youth Recommendations for Positive Service Experience

Across the Transition:Pre-,Peri- and Post-Transition Factors

Pre-Transition

(CAMHS)

• CAMHS clinician qualities (ex.tenacity,flexibility,

instilling hope,providing support and reassurance,

non-judgmental,good listener)

• Preparation (ex.early notification of transition

to AMHS)

• Youth involvement in transition planning

Peri-Transition

(CAMHS-AMHS)

• Individualized care plans geared towards youth

goals of functioning

• Increased autonomy in decision-making

• Community supports and primary care physicians

who provide “scaffolding” across the transition

from CAMHS to AMHS

• Gradualand flexible timing of transition

• Care continuity (ex.“Joint working” or “ParallelCare”

between CAMHS and AMHS)

• Relationalcare continuity to reduce fear of losing

relationships with pre-transition staff and to

promote comfort with AMHS

• System-levelcontinuity to reduce gaps

Post-Transition

(AMHS)

• Staff support and practicalstructure

• Autonomy in treatment decisions

• Choice about parentalinvolvement

• Physicalcare environments geared toward young

adults

• Informationalcontinuity (ie.sharing of clinical

information between CAMHS and AMHS)

Broad et al.BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380 Page 7 of 11

expressed a desire for practical support to help them achieve

their functional goals as they emerged into adulthood.

“Leaving the youth system would have been a better

experience ifsomeone could have helped me return to

school…Somebody helping me reach my goals of getting a

university degree” [39],p19.

“I wish that we had groups that—when we would make

it out in the real world—we wouldn’t be as stunned,you

know,dealing with you know the day to day thingsof

payingyour rent,payingyour cablebill, payingyour

phone bill...” [45],p3.

Balancing autonomy and the need for supports

Many young adults spoke abouttheir perceived lack of

knowledge abouttheir own diagnoses,available treat-

ments,and risks or benefits ofprescribed medications.

One youth described a lack of understanding of the vari-

ous care provider roles involved in his care:

“I mean,all that matters to me is just who is it,when

is it, where is it … I never care about what their profes-

sion is.” [42],p5.

Youth perspectives around independence and parental

involvementvaried with the population ofthe primary

study.Youth with eating disorders welcomed the oppor-

tunity to receiveindividually-based care(vs. family-

basedcare) during the transition from CAMHS to

AMHS [45]. In contrast,some youth with Autism

Spectrum Disorder (ASD)were largely unaware ofthe

transition process,and reported lacking skills and know-

ledge in how to manage their mentalhealth independ-

ently [42], with some questioningthe relevanceor

importance of knowing more [42]:

“They [medical doctors and mother] said I would never

be able to take responsibility for most ofthe things that

happen.So they do it for me … I don’t talk to the doctors

at all.” [p6].

However,other youth with ASD saw the transition

from CAMHS to AMHS as an opportunity to gather in-

formation about their issues to begin dealing with their

aspects of their medical care independently,as described

by another youth [42]:

“I got to start doing it.‘Cause it’s eventually will be my

problem. I’m not just going to call my parents late at night

from who knows where I’ll be and ask them about being or

going to doctors and wondering where to go…” [p6].

Though independence was a common theme for many

youth,many valued the continued involvementof sup-

ports.This was especially the case for youth who experi-

encedgaps in their serviceprovision or decreasing

amountof formalsupports.For these youth,parents,

community agencies and family physicians provided wel-

comed scaffolding.A youth interviewed by Jivanjee and

Kruzich [23] described the important role of his parents:

“My parents have been a pretty big support,too.I’m

19,so I can’t get support like I did when I was under 18,

so my parents had to still kind ofstay in there and help

me through allthe legaltroubles and helped guide me

through programs,support groups.” [p11].

Factors impacting youth experiences of transition

Youth described a numberof factorsthat influenced

their experience moving from CAMHS to AMHS (see

Table 2 for summary offactors contributing to positive

transition experiences).At the pre-transition period,

youth emphasized the importance ofrelationships with

staff and positive clinician qualities.In particular,loss of

clinician relationships and fear of less support in AMHS

characterized youths’emotionalexperience,as described

by a youth interviewed by O’Loughlin [45]:

“—I was,was quite nervous and I was quite,I suppose

I was quite worried that I wouldn’t get as much support

because you always think thatchildren getlooked after

better than adults,whereas when you’re out in the adult

service you wouldn’t get looked after as well.” [p62].

During the transition,youth felt that the sudden tim-

ing of transition wasarbitrary,with some questioning

the need for a service transition.Young people appreci-

ated transitions thatoccurred gradually and adapted to

their individualneeds,in contrastto abrupt,inflexible

transition timings.

Table 2 Youth Recommendations for Positive Service Experience

Across the Transition:Pre-,Peri- and Post-Transition Factors

Pre-Transition

(CAMHS)

• CAMHS clinician qualities (ex.tenacity,flexibility,

instilling hope,providing support and reassurance,

non-judgmental,good listener)

• Preparation (ex.early notification of transition

to AMHS)

• Youth involvement in transition planning

Peri-Transition

(CAMHS-AMHS)

• Individualized care plans geared towards youth

goals of functioning

• Increased autonomy in decision-making

• Community supports and primary care physicians

who provide “scaffolding” across the transition

from CAMHS to AMHS

• Gradualand flexible timing of transition

• Care continuity (ex.“Joint working” or “ParallelCare”

between CAMHS and AMHS)

• Relationalcare continuity to reduce fear of losing

relationships with pre-transition staff and to

promote comfort with AMHS

• System-levelcontinuity to reduce gaps

Post-Transition

(AMHS)

• Staff support and practicalstructure

• Autonomy in treatment decisions

• Choice about parentalinvolvement

• Physicalcare environments geared toward young

adults

• Informationalcontinuity (ie.sharing of clinical

information between CAMHS and AMHS)

Broad et al.BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380 Page 7 of 11

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

“I don’tsee whatage has gotto do with who you ‘re

seeing and where you see ‘em.Right,we ‘re used to com-

ing here,but now we ‘ve got to change and go somewhere

else,so that’s a bit annoying.” [44],p6.

“I think it should maybe be more assessed on the indi-

vidual patientratherthan just ‘oh you’renot 18, so

you’re in CAMHS.’I think that’s maybe something that

needs to change…...cause some people are more mature

and some people are less mature.” [45],p61.

“… gradually,just slowly,slowly I moved up to the

adult services when I was ready … I think it was a good

transition… I didn’t notice it too much.”[24,p4].

Young people wanted to participate in planning the

transition collaboratively with care plans that focused on

their goals offunctioning.Individualized plans based on

their unique needs and the opportunity for joint working

between CAMHS and AMHS were experienced positively,

as described by a youth interviewed by Hovish et al. [24]:

“I was told about the transfer and I would be meeting

the new [AMHS keyworker]…they explained how differ-

ent it would be…” [p4].

Once in AMHS, the lack ofinformationalcontinuity

or information sharing between child and adultmental

health serviceswasburdensome,and caused youth to

have to repeattheir personalnarrativeto multiple

clinicians.

“Even with like therapists that I seen,I seen about four

or five,which I always find hard and stilldo cause you

build up trustwith somebody and then they disappear

and you have to startall overagain with thesimple

questions ofwhen did it start,how did it...and all that”

[45],p77.

Some young adults also expressed difficulty adjusting

to the care environment in AMHS:

“No one understood me.It was awful.I was in the

[private]hospitalfor a while and couldn’tgetwhat I

needed.I was one of the youngest people there.” [39],p17.

“When I wentto CAP I metX regular,but now at

GenP it’s like,the worse you feelthe more meetings you

get,and the better you feel the less meetings you gets,it’s

like more irregularity.” [36],p5.

Discussion

In this thematic synthesis,we reviewed the experiences

of youth transitioning between CAMHS and AMHS.

Youth illuminated thatthe transition wasa turbulent

time, during which concurrentlife transitionsover-

lapped with an institutionalized transition system,that

was often unresponsive to individualneeds.Youth de-

scribed a delicate balance between gaining autonomy

and independence while also wanting continued parental

and service supports.Young people emphasized a need

for an individualized approach,that allowed for flexible

transition timing,joint working and youth engagement.

Previously,Mulvale etal. [48]described the primary

differencesin care philosophiesbetween CAMHS and

AMHS. Whereas CAMHS emphasized the family unit,

AMHS considered youth autonomous adults and limited

family involvement in favor of personalprivacy.Our re-

view identified thatthough independence is valued by

some youth,for other youth continued parentalinvolve-

ment and support is preferred,and this sudden shift in

parental involvement may leave some youth feeling over-

whelmed and alone.The abruptreduction in parental

and service-related supports,coupled with the conflu-

ence of personaldevelopmentalmilestones and an insti-

tutionalized health care transition creates challenges for

youth who are already vulnerable due to mentalhealth

difficulties,such as intellectual limitations and emotional

vulnerabilities.

Furthermore,there is a shift from a nurturing environ-

mentin CAMHS to a more impersonalatmosphere in

AMHS [48],which was echoed by young people in our

review.Previous research has shown the importance of

relationships with clinicians for positive experiences in

mentalhealth care [49].For youth who have previously

experienced trauma orfamily conflict,the lossof im-

portant clinician relationships may contribute to poorer

transition experiencesand overallwellbeing.Difficulty

forming new relationshipswith AMHS cliniciansmay

also lead to a poorer therapeutic alliance and higher risk

of disengagement [50].

Youth’s insight into transition timing showed the tim-

ing to be arbitrary and misaligned with their own devel-

opmental needs. With mental illness frequently

emerging in adolescence [1],some youth had only re-

cently become engaged in mentalhealth service use and

may have had less comfort and investment with accept-

ing mentalhealth care.Having gaps or suboptimalcare

during this time may tip these already at-risk individuals

into disengagement.Furthermore,current transition

timing means transition is rarely an isolated event[3].

Changes in living arrangements,parenthood and other

stressorsof entering adulthood maytake precedence

over mentalhealth treatment.Young people’sexperi-

ences ofinflexible policies,such as the limitations im-

posed by catchments areas,only add to the difficulty in

youth remaining engaged.

Overall,the experiences ofyouth were closely tied to

the distinctculturaldifferencesbetween CAMHS and

AMHS. This is consistent with previous findings by the

NHS England,which described the sharp change from

child to adult services as a “cliff edge” which can cause a

young person to relapse or even stop using services [51].

Health care providers have also shown awareness of this

divide and attemptsat collaborative working between

services [52].However,these efforts are limited by finan-

cial,structural and geographical barriers.

Broad et al.BMC Psychiatry (2017) 17:380 Page 8 of 11

seeing and where you see ‘em.Right,we ‘re used to com-

ing here,but now we ‘ve got to change and go somewhere

else,so that’s a bit annoying.” [44],p6.

“I think it should maybe be more assessed on the indi-

vidual patientratherthan just ‘oh you’renot 18, so

you’re in CAMHS.’I think that’s maybe something that

needs to change…...cause some people are more mature

and some people are less mature.” [45],p61.

“… gradually,just slowly,slowly I moved up to the

adult services when I was ready … I think it was a good

transition… I didn’t notice it too much.”[24,p4].

Young people wanted to participate in planning the

transition collaboratively with care plans that focused on

their goals offunctioning.Individualized plans based on

their unique needs and the opportunity for joint working

between CAMHS and AMHS were experienced positively,

as described by a youth interviewed by Hovish et al. [24]:

“I was told about the transfer and I would be meeting

the new [AMHS keyworker]…they explained how differ-

ent it would be…” [p4].

Once in AMHS, the lack ofinformationalcontinuity

or information sharing between child and adultmental

health serviceswasburdensome,and caused youth to

have to repeattheir personalnarrativeto multiple

clinicians.

“Even with like therapists that I seen,I seen about four

or five,which I always find hard and stilldo cause you

build up trustwith somebody and then they disappear

and you have to startall overagain with thesimple

questions ofwhen did it start,how did it...and all that”

[45],p77.

Some young adults also expressed difficulty adjusting

to the care environment in AMHS:

“No one understood me.It was awful.I was in the

[private]hospitalfor a while and couldn’tgetwhat I

needed.I was one of the youngest people there.” [39],p17.

“When I wentto CAP I metX regular,but now at

GenP it’s like,the worse you feelthe more meetings you

get,and the better you feel the less meetings you gets,it’s

like more irregularity.” [36],p5.

Discussion

In this thematic synthesis,we reviewed the experiences

of youth transitioning between CAMHS and AMHS.

Youth illuminated thatthe transition wasa turbulent

time, during which concurrentlife transitionsover-

lapped with an institutionalized transition system,that

was often unresponsive to individualneeds.Youth de-

scribed a delicate balance between gaining autonomy

and independence while also wanting continued parental

and service supports.Young people emphasized a need

for an individualized approach,that allowed for flexible

transition timing,joint working and youth engagement.

Previously,Mulvale etal. [48]described the primary

differencesin care philosophiesbetween CAMHS and

AMHS. Whereas CAMHS emphasized the family unit,

AMHS considered youth autonomous adults and limited