Qualitative Analysis of Adolescent Suicide Attempts and Revenge

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/26

|8

|8089

|412

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a qualitative study that investigated the experiences of adolescents and young adults who had attempted suicide. Conducted using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), the study involved semi-structured interviews with sixteen participants, with a focus on understanding their perspectives on the suicidal acts. The research identified two main themes: individual dimensions, encompassing negative self-emotions and the need for control, and relational dimensions, including interpersonal impasses, communication issues, and the often-neglected role of revenge. The study highlights that adolescents often feel trapped in both personal and relational dead-ends, with revenge emerging as a crucial, yet overlooked, factor bridging this gap and transforming personal distress into a relational matter. This research underscores the importance of considering relational dynamics and the powerful emotion of revenge in clinical and research contexts when addressing adolescent suicidal behavior. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of three hospitals in northeastern Italy.

Qualitative Approach to Attempted Suicide by

Adolescents and Young Adults:The (Neglected) Role of

Revenge

Massimiliano Orri1*, Matteo Paduanello2, Jonathan Lachal1,3, Bruno Falissard1, Jordan Sibeoni 1,3,

Anne Revah-Levy1,4

1 INSERM 669 research unit,Paris-Sud University and Paris-Descartes University,Paris,France,2 DepartmentApplied Psychology,University ofPadua,Padua,Italy,

3 Maison de Solenn, AP-HP Cochin Hospital, Paris, France, 4 Centre de Soins Psychothe´rapeutiques de Transition pour Adolescents, Argenteuil Hospital Centre, Argenteuil,

France

Abstract

Background:Suicide by adolescents and young adults is a major public health concern,and repetition of self-harm is an

important risk factor for future suicide attempts.

Objective:Our purpose is to explore the perspective of adolescents directly involved in suicidalacts.

Methods:Qualitative study involving 16 purposively selected adolescents (sex ratio1:1) from 3 different centers.Half had

been involved in repeated suicidal acts, and the other half only one. Data were gathered through semistructured interv

and analyzed according to Interpretative PhenomenologicalAnalysis.

Results:We found five main themes, organized in two superordinate themes.The first theme (individual dimensions of the

suicide attempt) describes the issues and explanations that the adolescents saw as related to themselves;it includes the

subthemes: (1) negative emotions toward the self and individual impasse, and (2) the need for some control over their

The second main theme (relational dimensions of attempted suicide) describes issues that adolescents mentioned that

related to others and includes three subthemes:(3) perceived impasse in interpersonalrelationships,(4) communication,

and (5) revenge.

Conclusions:Adolescents involved in suicidal behavior are stuck in both an individual and a relational impasse from whic

there is no exit and no apparent way to reach the other. Revenge can bridge this gap and thus transforms personal dis

into a relationalmatter.This powerfulemotion has been neglected by both clinicians and researchers.

Citation: OrriM, Paduanello M,LachalJ, Falissard B,SibeoniJ, et al.(2014) Qualitative Approach to Attempted Suicide by Adolescents and Young Adults:The

(Neglected) Role of Revenge.PLoS ONE 9(5):e96716.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096716

Editor: Fiona Harris,University of Stirling,United Kingdom

Received November 21,2013;Accepted April9, 2014;Published May 6,2014

Copyright: ß 2014 Orri et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestrict

use,distribution,and reproduction in any medium,provided the originalauthor and source are credited.

Funding: The authors have no support or funding to report.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

* E-mail:massimiliano.orri@inserm.fr

Introduction

Adolescentsuicideis a major publichealth concern in all

western countries. Epidemiologicaldata show that it is one of the

three leading causesof death worldwide among those younger

than 25 years [1,2].A more statistically widespread phenomenon

is attempted suicide:its prevalence is about7.8% in the United

States [2] and 10.5% in Europe [3]. The highest attempted suicide

rate is recorded amongthoseaged 15–24years,and their

attempted/completed suicide ratio is estimated to be between 50:1

and 100:1 [4].The prevention of suicidalbehavior is therefore a

primary socialand medicalconcern throughoutthe world [1,5].

Nonetheless,despite a large number ofresearch and prevention

programs,the attempted suicide rate among youth is increasing

[6], and secondary prevention interventions have thus far achieved

limited results[7,8]. The numerousstudies,conducted from

multipleperspectives(including psychological,psychiatric,and

sociological),show that one of the most important risk factors for

attempted suicide isa previousattempt[9–11].According to a

recent English study,repetition of self-harm occurs in about 27%

of adolescents,and the four major risk factors for repetition are

age,prior psychiatric treatment,self-cutting,and previousself-

harm.This study also found thatyouthswho soughtcare ata

hospitalfor self-harm are 10 times more likely to die by suicide

than would be expected in this age group [12].

Although an understanding ofthe adolescentperspective is

essentialin preventingthe relapseof suicidalbehaviors,the

subjective experience of those directly involved in suicidal acts ha

not been sufficientlyexplored [13].Qualitativemethodsare

particularly suited to investigating participants’viewpoints,their

lived experiences,and their interior worlds [14,15].Nevertheless,

qualitative research in adolescent suicidology is rare [16].To our

knowledge,only two qualitativestudies[17,18]havedirectly

addressed theproblem ofrelapseof suicidalor self-harming

PLOS ONE |www.plosone.org 1 May 2014 |Volume 9 |Issue 5 | e96716

Adolescents and Young Adults:The (Neglected) Role of

Revenge

Massimiliano Orri1*, Matteo Paduanello2, Jonathan Lachal1,3, Bruno Falissard1, Jordan Sibeoni 1,3,

Anne Revah-Levy1,4

1 INSERM 669 research unit,Paris-Sud University and Paris-Descartes University,Paris,France,2 DepartmentApplied Psychology,University ofPadua,Padua,Italy,

3 Maison de Solenn, AP-HP Cochin Hospital, Paris, France, 4 Centre de Soins Psychothe´rapeutiques de Transition pour Adolescents, Argenteuil Hospital Centre, Argenteuil,

France

Abstract

Background:Suicide by adolescents and young adults is a major public health concern,and repetition of self-harm is an

important risk factor for future suicide attempts.

Objective:Our purpose is to explore the perspective of adolescents directly involved in suicidalacts.

Methods:Qualitative study involving 16 purposively selected adolescents (sex ratio1:1) from 3 different centers.Half had

been involved in repeated suicidal acts, and the other half only one. Data were gathered through semistructured interv

and analyzed according to Interpretative PhenomenologicalAnalysis.

Results:We found five main themes, organized in two superordinate themes.The first theme (individual dimensions of the

suicide attempt) describes the issues and explanations that the adolescents saw as related to themselves;it includes the

subthemes: (1) negative emotions toward the self and individual impasse, and (2) the need for some control over their

The second main theme (relational dimensions of attempted suicide) describes issues that adolescents mentioned that

related to others and includes three subthemes:(3) perceived impasse in interpersonalrelationships,(4) communication,

and (5) revenge.

Conclusions:Adolescents involved in suicidal behavior are stuck in both an individual and a relational impasse from whic

there is no exit and no apparent way to reach the other. Revenge can bridge this gap and thus transforms personal dis

into a relationalmatter.This powerfulemotion has been neglected by both clinicians and researchers.

Citation: OrriM, Paduanello M,LachalJ, Falissard B,SibeoniJ, et al.(2014) Qualitative Approach to Attempted Suicide by Adolescents and Young Adults:The

(Neglected) Role of Revenge.PLoS ONE 9(5):e96716.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096716

Editor: Fiona Harris,University of Stirling,United Kingdom

Received November 21,2013;Accepted April9, 2014;Published May 6,2014

Copyright: ß 2014 Orri et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestrict

use,distribution,and reproduction in any medium,provided the originalauthor and source are credited.

Funding: The authors have no support or funding to report.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

* E-mail:massimiliano.orri@inserm.fr

Introduction

Adolescentsuicideis a major publichealth concern in all

western countries. Epidemiologicaldata show that it is one of the

three leading causesof death worldwide among those younger

than 25 years [1,2].A more statistically widespread phenomenon

is attempted suicide:its prevalence is about7.8% in the United

States [2] and 10.5% in Europe [3]. The highest attempted suicide

rate is recorded amongthoseaged 15–24years,and their

attempted/completed suicide ratio is estimated to be between 50:1

and 100:1 [4].The prevention of suicidalbehavior is therefore a

primary socialand medicalconcern throughoutthe world [1,5].

Nonetheless,despite a large number ofresearch and prevention

programs,the attempted suicide rate among youth is increasing

[6], and secondary prevention interventions have thus far achieved

limited results[7,8]. The numerousstudies,conducted from

multipleperspectives(including psychological,psychiatric,and

sociological),show that one of the most important risk factors for

attempted suicide isa previousattempt[9–11].According to a

recent English study,repetition of self-harm occurs in about 27%

of adolescents,and the four major risk factors for repetition are

age,prior psychiatric treatment,self-cutting,and previousself-

harm.This study also found thatyouthswho soughtcare ata

hospitalfor self-harm are 10 times more likely to die by suicide

than would be expected in this age group [12].

Although an understanding ofthe adolescentperspective is

essentialin preventingthe relapseof suicidalbehaviors,the

subjective experience of those directly involved in suicidal acts ha

not been sufficientlyexplored [13].Qualitativemethodsare

particularly suited to investigating participants’viewpoints,their

lived experiences,and their interior worlds [14,15].Nevertheless,

qualitative research in adolescent suicidology is rare [16].To our

knowledge,only two qualitativestudies[17,18]havedirectly

addressed theproblem ofrelapseof suicidalor self-harming

PLOS ONE |www.plosone.org 1 May 2014 |Volume 9 |Issue 5 | e96716

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

behavior among youth.In particular,one ofthem showed that

currentservicesrespond inadequately to self-harming behaviors

among young people and struggle to dealwith the needsthis

population experiences [18].

The aim of this qualitative study is to explore the perspective of

adolescents(for clarity’ssake,we referto our participantsas

adolescents)who have directly engaged in suicidalacts (in either

single or repeated suicide attempts).Exploring the factors related

to their success or failure in overcoming and moving beyond the

suicidalperiod mightprovide clinicianswith importantinsights

usefulin caring for young people involved in suicidalbehavior,

especially in a perspective of preventing repetition.

Methods

Participants and Setting

Participantsreceived complete written information aboutthe

scope of the research, the identity and affiliation of the researchers,

the possibilityof withdrawingfrom the studyat any point,

confidentiality,and allother information required in accordance

with Italian policiesfor psychologicalresearch and with the

HelsinkiDeclaration,as revised in 1989.Participants (and their

parents,for minors)provided written consent.This research

received approval from the institutional review boards of the three

hospitalsinvolved:Santa Giuliana Hospital, Verona; Este

Hospital,Padua;Monselice Hospital,Padua.These were two

localgeneralhospitals (with inpatientand outpatientadolescent

psychiatric departments)and one psychiatric hospitalin north-

eastern Italy.Physicians or psychologists atthese hospitals were

contacted and asked if they had patients who might be appropriate

subjects for a study ofadolescent suicide attempts.Subjects were

eligible only if they had attempted suicide during adolescence or in

the postadolescent period and were aged 15 to 25 years old at the

time of the interview.Eligible subjects were then contacted.

Purposivesampling[19] was undertaken,and inclusion of

subjects continued untilsaturation was reached [20].As recom-

mended for Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) [21,22],

we chose to focus on only a few cases and to analyze their accounts

in depth.Moreover,to includea heterogeneoussamplewith

maximum variation [19], we included both adolescents with only a

single suicidal act and those with multiple acts. We were therefore

ableto considera wide rangeof situationsand experiences.

SixteenItalian adolescents(sex ratio 1:1) freelyagreedto

participate in the study (two refused,one male and one female).

Their median age was 20 years atthe interview,and 16 atthe

suicide attempt.Half had a history of previous attempts ($1,see

Table 1).

Data Collection

Data were collected through 16 individual semi-structured face-

to-faceinterviews.The interviewswere audio-recordedand

subsequentlytranscribedverbatim,with all nuancesof the

participants’expressionrecorded.An interview topicguide

(Table 2)was developed in advance and included 8 open-ended

questionsand severalprompts.The logic underpinningthe

construction ofthe interview guide wasto elicitin-depth and

detailed accountsof the subjects’feelingsbeforethe suicide

attempt and afterwards, as wellas the expectations and meanings

that they connected to this action.Our overallobjective in using

this qualitative method was to put ourselves in the lived world of

each participantand explore the meaning ofthe experience to

each ofthem.Fourteen interviews took place atthe adolescents’

treatmentfacility,one atthe adolescent’s home,and one atthe

residentialfacility wherethe adolescentwas living.Sincethe

sensitive topic of our interviews,considerable attention was given

to the evaluation of participants’ opinion about the interview after

its end. All adolescents felt comfortable discussing their experienc

and explaining their perspective withoutreceiving any judgment

from the researcher.Referentpsychologistsor physiciansnever

reportedany concern.In addition,researchersthemselves

discussed theirown feelingsaboutthe interviewsduring study

group meetings, in order to take into account potentialinfluences

on data collection and analysis (reflexivity).

Data Analysis

Qualitative analysis was performed according to IPA method-

ology. The aim of this method is to understand how people make

sense oftheir majorlife experiencesby adopting an ‘‘insider

perspective’’[23].Three epistemologicalpointsunderpin IPA:

first,it is a phenomenologicalmethod thatseeks to explore the

informants’views ofthe world.As Husserlpointed out [24],the

objective of phenomenology is to understand how a phenomenon

appears in the individual’s conscious experience.Hence,experi-

ence is conceived as uniquely perspectival, embodied, and situate

[21]. Second, IPA is based on hermeneutics: interpretative activity

as defined by Smith & Osborn [22], is a dual process in which the

‘‘researcher istrying to make sense ofthe participanttrying to

make sense of what is happening to them’’. In practice, during the

analysis,the researchermightmovedialectically between the

wholeand the parts,as well as between understandingand

interpretation. Third, the idiographic approach emphasizes a deep

understandingof the individualcases.IPA is committed to

understanding the way in which participants understand particula

phenomena from their perspective and in their context [21].

The analyticprocessproceeded through severalstages:we

began by reading and rereading the entirety of each interview, to

familiarize ourselves with the participant’s expressive style and to

obtain an overall impression.We took initial notes that

corresponded to the fundamentalunits of meaning.At this stage,

the notes were descriptive and used the participants’own words;

particular attention was paid to linguistic details, including the use

of expressions(especiallyyouth slang)and metaphors.Then

conceptual/psychological notes were drafted, through processes o

condensation,comparison,and abstractingthe initial notes.

Connectionswith noteswere mappedand synthesized,and

emergentthemesdeveloped.Each interview wasseparately

analyzed in this way and then compared to enable us to cluster

themesinto superordinate categories.Through thisprocess,the

analysis moved through different interpretative levels,from more

descriptive stages to more interpretative ones;every conceptnot

supported by data waseliminated.The primary concern for

researchersis to maintain thelink between theirconceptual

organization and the participants’ words [25]. For this reason, the

categoriesof analysisare notworked outin advance,but are

derived inductively from the empiricaldata.

To ensure validity,two researchers (MO and MP,both expert

psychologists trained in qualitative research)conducted separate

analysesof these interviewsand compared them afterwards.A

third researcher(ARL, psychiatristspecialistin qualitative

research)triangulatedthe analysis.Every discrepancywas

negotiated during study group meetings, and the final organizatio

emerged from the work in concertof all the researchers.We

agreed to considered data saturation to be reached because no

new aspects emerged from the interviews (i.e. no more coded we

added to our codebook) in each of our themes, and last interviews

did not provideadditionalunderstanding ofour participants’

experience.

Qualitative Approach to Attempted Suicide by Youth

PLOS ONE |www.plosone.org 2 May 2014 |Volume 9 |Issue 5 | e96716

currentservicesrespond inadequately to self-harming behaviors

among young people and struggle to dealwith the needsthis

population experiences [18].

The aim of this qualitative study is to explore the perspective of

adolescents(for clarity’ssake,we referto our participantsas

adolescents)who have directly engaged in suicidalacts (in either

single or repeated suicide attempts).Exploring the factors related

to their success or failure in overcoming and moving beyond the

suicidalperiod mightprovide clinicianswith importantinsights

usefulin caring for young people involved in suicidalbehavior,

especially in a perspective of preventing repetition.

Methods

Participants and Setting

Participantsreceived complete written information aboutthe

scope of the research, the identity and affiliation of the researchers,

the possibilityof withdrawingfrom the studyat any point,

confidentiality,and allother information required in accordance

with Italian policiesfor psychologicalresearch and with the

HelsinkiDeclaration,as revised in 1989.Participants (and their

parents,for minors)provided written consent.This research

received approval from the institutional review boards of the three

hospitalsinvolved:Santa Giuliana Hospital, Verona; Este

Hospital,Padua;Monselice Hospital,Padua.These were two

localgeneralhospitals (with inpatientand outpatientadolescent

psychiatric departments)and one psychiatric hospitalin north-

eastern Italy.Physicians or psychologists atthese hospitals were

contacted and asked if they had patients who might be appropriate

subjects for a study ofadolescent suicide attempts.Subjects were

eligible only if they had attempted suicide during adolescence or in

the postadolescent period and were aged 15 to 25 years old at the

time of the interview.Eligible subjects were then contacted.

Purposivesampling[19] was undertaken,and inclusion of

subjects continued untilsaturation was reached [20].As recom-

mended for Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) [21,22],

we chose to focus on only a few cases and to analyze their accounts

in depth.Moreover,to includea heterogeneoussamplewith

maximum variation [19], we included both adolescents with only a

single suicidal act and those with multiple acts. We were therefore

ableto considera wide rangeof situationsand experiences.

SixteenItalian adolescents(sex ratio 1:1) freelyagreedto

participate in the study (two refused,one male and one female).

Their median age was 20 years atthe interview,and 16 atthe

suicide attempt.Half had a history of previous attempts ($1,see

Table 1).

Data Collection

Data were collected through 16 individual semi-structured face-

to-faceinterviews.The interviewswere audio-recordedand

subsequentlytranscribedverbatim,with all nuancesof the

participants’expressionrecorded.An interview topicguide

(Table 2)was developed in advance and included 8 open-ended

questionsand severalprompts.The logic underpinningthe

construction ofthe interview guide wasto elicitin-depth and

detailed accountsof the subjects’feelingsbeforethe suicide

attempt and afterwards, as wellas the expectations and meanings

that they connected to this action.Our overallobjective in using

this qualitative method was to put ourselves in the lived world of

each participantand explore the meaning ofthe experience to

each ofthem.Fourteen interviews took place atthe adolescents’

treatmentfacility,one atthe adolescent’s home,and one atthe

residentialfacility wherethe adolescentwas living.Sincethe

sensitive topic of our interviews,considerable attention was given

to the evaluation of participants’ opinion about the interview after

its end. All adolescents felt comfortable discussing their experienc

and explaining their perspective withoutreceiving any judgment

from the researcher.Referentpsychologistsor physiciansnever

reportedany concern.In addition,researchersthemselves

discussed theirown feelingsaboutthe interviewsduring study

group meetings, in order to take into account potentialinfluences

on data collection and analysis (reflexivity).

Data Analysis

Qualitative analysis was performed according to IPA method-

ology. The aim of this method is to understand how people make

sense oftheir majorlife experiencesby adopting an ‘‘insider

perspective’’[23].Three epistemologicalpointsunderpin IPA:

first,it is a phenomenologicalmethod thatseeks to explore the

informants’views ofthe world.As Husserlpointed out [24],the

objective of phenomenology is to understand how a phenomenon

appears in the individual’s conscious experience.Hence,experi-

ence is conceived as uniquely perspectival, embodied, and situate

[21]. Second, IPA is based on hermeneutics: interpretative activity

as defined by Smith & Osborn [22], is a dual process in which the

‘‘researcher istrying to make sense ofthe participanttrying to

make sense of what is happening to them’’. In practice, during the

analysis,the researchermightmovedialectically between the

wholeand the parts,as well as between understandingand

interpretation. Third, the idiographic approach emphasizes a deep

understandingof the individualcases.IPA is committed to

understanding the way in which participants understand particula

phenomena from their perspective and in their context [21].

The analyticprocessproceeded through severalstages:we

began by reading and rereading the entirety of each interview, to

familiarize ourselves with the participant’s expressive style and to

obtain an overall impression.We took initial notes that

corresponded to the fundamentalunits of meaning.At this stage,

the notes were descriptive and used the participants’own words;

particular attention was paid to linguistic details, including the use

of expressions(especiallyyouth slang)and metaphors.Then

conceptual/psychological notes were drafted, through processes o

condensation,comparison,and abstractingthe initial notes.

Connectionswith noteswere mappedand synthesized,and

emergentthemesdeveloped.Each interview wasseparately

analyzed in this way and then compared to enable us to cluster

themesinto superordinate categories.Through thisprocess,the

analysis moved through different interpretative levels,from more

descriptive stages to more interpretative ones;every conceptnot

supported by data waseliminated.The primary concern for

researchersis to maintain thelink between theirconceptual

organization and the participants’ words [25]. For this reason, the

categoriesof analysisare notworked outin advance,but are

derived inductively from the empiricaldata.

To ensure validity,two researchers (MO and MP,both expert

psychologists trained in qualitative research)conducted separate

analysesof these interviewsand compared them afterwards.A

third researcher(ARL, psychiatristspecialistin qualitative

research)triangulatedthe analysis.Every discrepancywas

negotiated during study group meetings, and the final organizatio

emerged from the work in concertof all the researchers.We

agreed to considered data saturation to be reached because no

new aspects emerged from the interviews (i.e. no more coded we

added to our codebook) in each of our themes, and last interviews

did not provideadditionalunderstanding ofour participants’

experience.

Qualitative Approach to Attempted Suicide by Youth

PLOS ONE |www.plosone.org 2 May 2014 |Volume 9 |Issue 5 | e96716

We reportthe study according to theCOREQ statement.

(Table S1)

Results

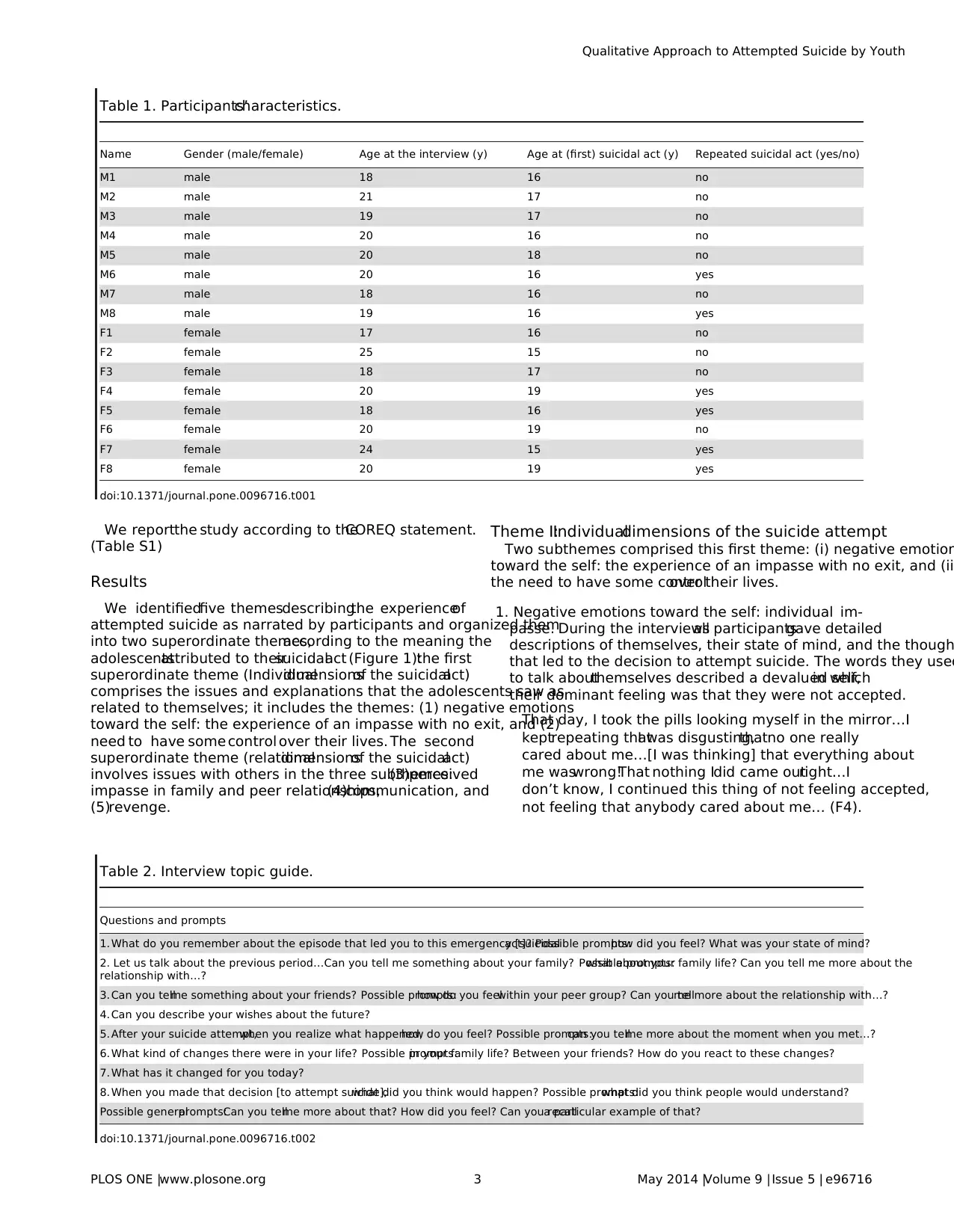

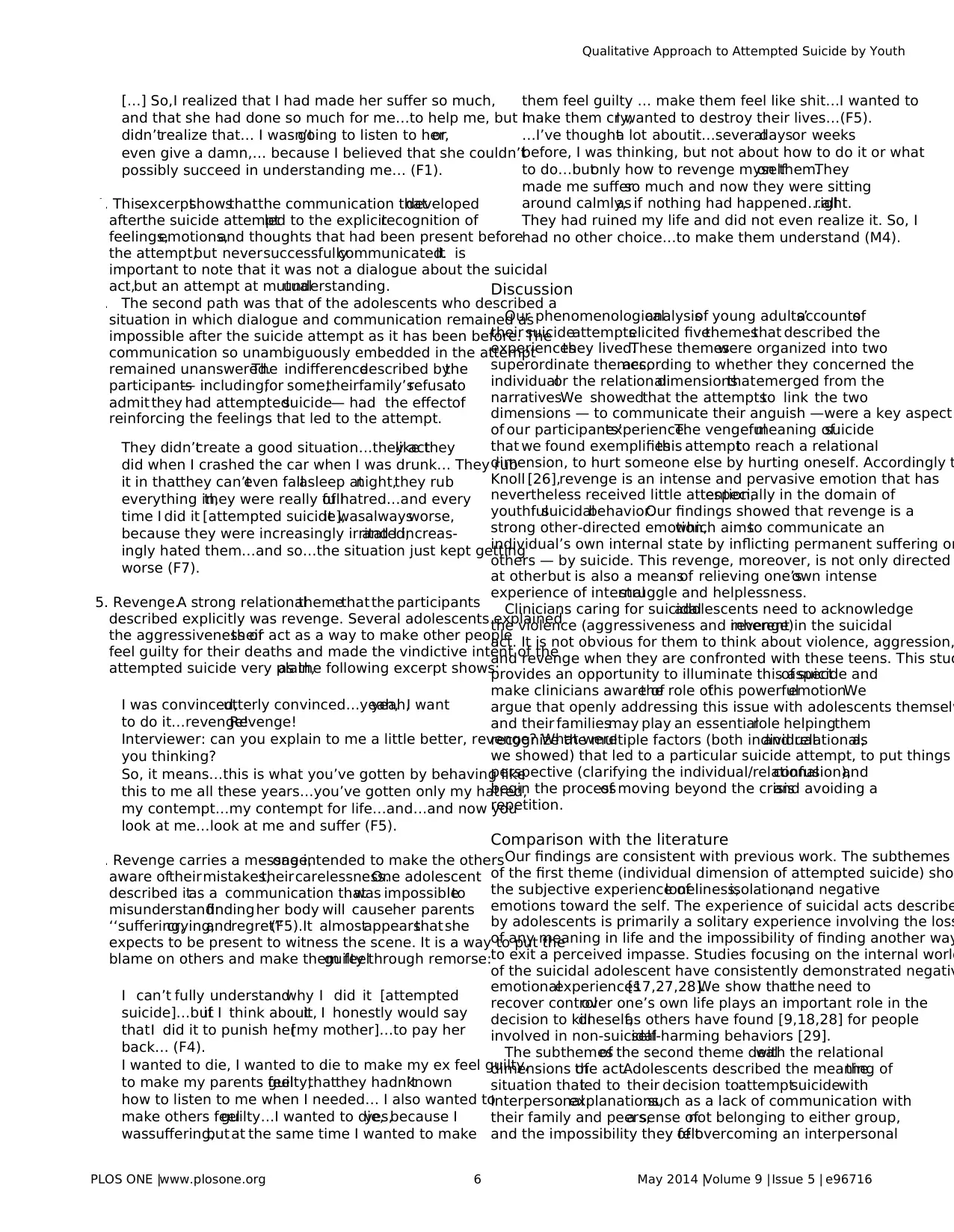

We identifiedfive themesdescribingthe experienceof

attempted suicide as narrated by participants and organized them

into two superordinate themes,according to the meaning the

adolescentsattributed to theirsuicidalact (Figure 1):the first

superordinate theme (Individualdimensionsof the suicidalact)

comprises the issues and explanations that the adolescents saw as

related to themselves; it includes the themes: (1) negative emotions

toward the self: the experience of an impasse with no exit, and (2)

need to have some control over their lives. The second

superordinate theme (relationaldimensionsof the suicidalact)

involves issues with others in the three subthemes:(3)perceived

impasse in family and peer relationships,(4)communication, and

(5)revenge.

Theme I:Individualdimensions of the suicide attempt

Two subthemes comprised this first theme: (i) negative emotion

toward the self: the experience of an impasse with no exit, and (ii

the need to have some controlover their lives.

1. Negative emotions toward the self: individual im-

passe. During the interviewsall participantsgave detailed

descriptions of themselves, their state of mind, and the though

that led to the decision to attempt suicide. The words they used

to talk aboutthemselves described a devalued self,in which

their dominant feeling was that they were not accepted.

That day, I took the pills looking myself in the mirror…I

keptrepeating thatI was disgusting,thatno one really

cared about me…[I was thinking] that everything about

me waswrong!That nothing Idid came outright…I

don’t know, I continued this thing of not feeling accepted,

not feeling that anybody cared about me… (F4).

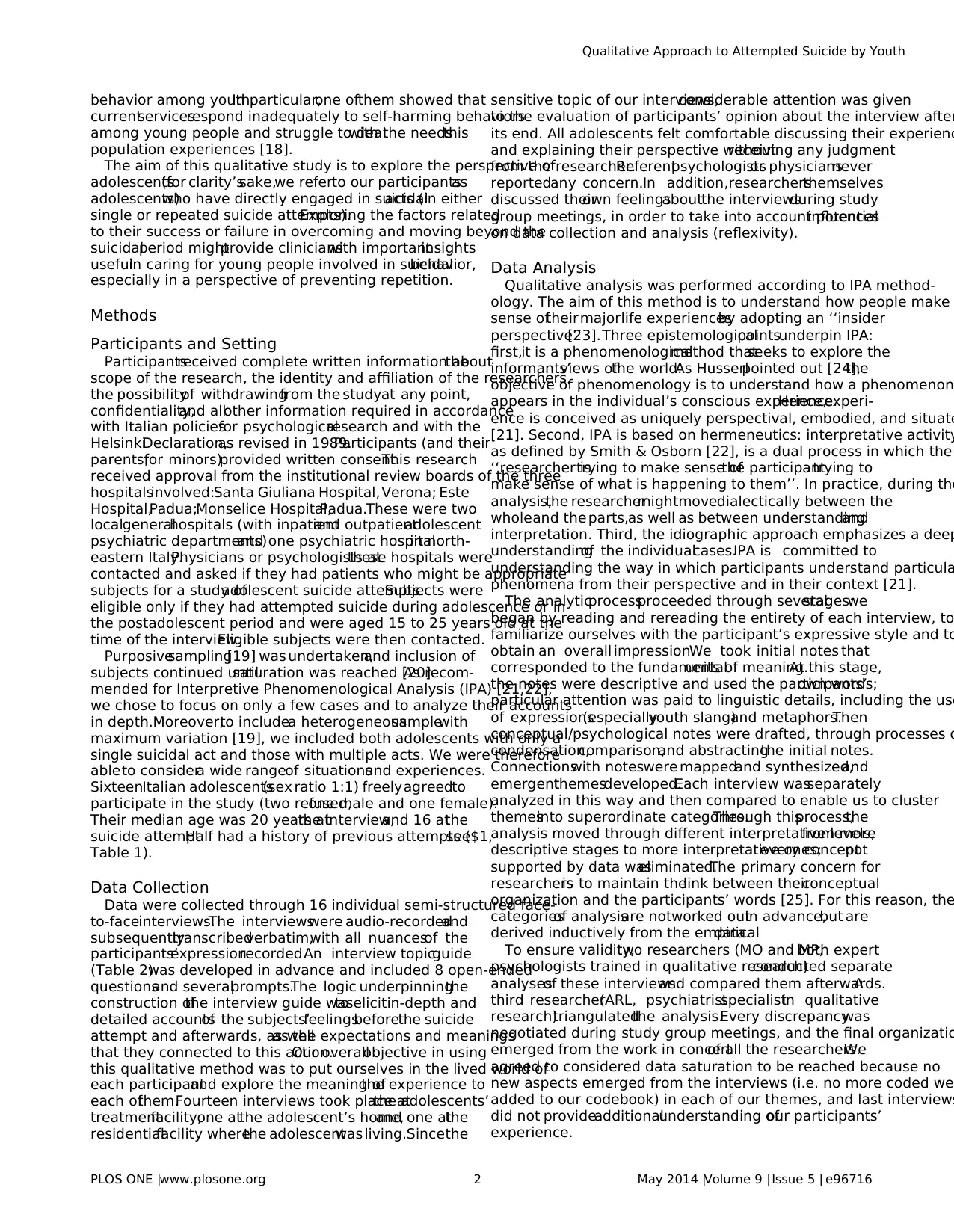

Table 1. Participants’characteristics.

Name Gender (male/female) Age at the interview (y) Age at (first) suicidal act (y) Repeated suicidal act (yes/no)

M1 male 18 16 no

M2 male 21 17 no

M3 male 19 17 no

M4 male 20 16 no

M5 male 20 18 no

M6 male 20 16 yes

M7 male 18 16 no

M8 male 19 16 yes

F1 female 17 16 no

F2 female 25 15 no

F3 female 18 17 no

F4 female 20 19 yes

F5 female 18 16 yes

F6 female 20 19 no

F7 female 24 15 yes

F8 female 20 19 yes

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096716.t001

Table 2. Interview topic guide.

Questions and prompts

1. What do you remember about the episode that led you to this emergency [suicidalact]? Possible prompts:how did you feel? What was your state of mind?

2. Let us talk about the previous period…Can you tell me something about your family? Possible prompts:what about your family life? Can you tell me more about the

relationship with…?

3. Can you tellme something about your friends? Possible prompts:how do you feelwithin your peer group? Can you tellme more about the relationship with…?

4. Can you describe your wishes about the future?

5. After your suicide attempt,when you realize what happened,how do you feel? Possible prompts:can you tellme more about the moment when you met…?

6. What kind of changes there were in your life? Possible prompts:in your family life? Between your friends? How do you react to these changes?

7. What has it changed for you today?

8. When you made that decision [to attempt suicide],what did you think would happen? Possible prompts:what did you think people would understand?

Possible generalprompts:Can you tellme more about that? How did you feel? Can you recalla particular example of that?

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096716.t002

Qualitative Approach to Attempted Suicide by Youth

PLOS ONE |www.plosone.org 3 May 2014 |Volume 9 |Issue 5 | e96716

(Table S1)

Results

We identifiedfive themesdescribingthe experienceof

attempted suicide as narrated by participants and organized them

into two superordinate themes,according to the meaning the

adolescentsattributed to theirsuicidalact (Figure 1):the first

superordinate theme (Individualdimensionsof the suicidalact)

comprises the issues and explanations that the adolescents saw as

related to themselves; it includes the themes: (1) negative emotions

toward the self: the experience of an impasse with no exit, and (2)

need to have some control over their lives. The second

superordinate theme (relationaldimensionsof the suicidalact)

involves issues with others in the three subthemes:(3)perceived

impasse in family and peer relationships,(4)communication, and

(5)revenge.

Theme I:Individualdimensions of the suicide attempt

Two subthemes comprised this first theme: (i) negative emotion

toward the self: the experience of an impasse with no exit, and (ii

the need to have some controlover their lives.

1. Negative emotions toward the self: individual im-

passe. During the interviewsall participantsgave detailed

descriptions of themselves, their state of mind, and the though

that led to the decision to attempt suicide. The words they used

to talk aboutthemselves described a devalued self,in which

their dominant feeling was that they were not accepted.

That day, I took the pills looking myself in the mirror…I

keptrepeating thatI was disgusting,thatno one really

cared about me…[I was thinking] that everything about

me waswrong!That nothing Idid came outright…I

don’t know, I continued this thing of not feeling accepted,

not feeling that anybody cared about me… (F4).

Table 1. Participants’characteristics.

Name Gender (male/female) Age at the interview (y) Age at (first) suicidal act (y) Repeated suicidal act (yes/no)

M1 male 18 16 no

M2 male 21 17 no

M3 male 19 17 no

M4 male 20 16 no

M5 male 20 18 no

M6 male 20 16 yes

M7 male 18 16 no

M8 male 19 16 yes

F1 female 17 16 no

F2 female 25 15 no

F3 female 18 17 no

F4 female 20 19 yes

F5 female 18 16 yes

F6 female 20 19 no

F7 female 24 15 yes

F8 female 20 19 yes

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096716.t001

Table 2. Interview topic guide.

Questions and prompts

1. What do you remember about the episode that led you to this emergency [suicidalact]? Possible prompts:how did you feel? What was your state of mind?

2. Let us talk about the previous period…Can you tell me something about your family? Possible prompts:what about your family life? Can you tell me more about the

relationship with…?

3. Can you tellme something about your friends? Possible prompts:how do you feelwithin your peer group? Can you tellme more about the relationship with…?

4. Can you describe your wishes about the future?

5. After your suicide attempt,when you realize what happened,how do you feel? Possible prompts:can you tellme more about the moment when you met…?

6. What kind of changes there were in your life? Possible prompts:in your family life? Between your friends? How do you react to these changes?

7. What has it changed for you today?

8. When you made that decision [to attempt suicide],what did you think would happen? Possible prompts:what did you think people would understand?

Possible generalprompts:Can you tellme more about that? How did you feel? Can you recalla particular example of that?

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096716.t002

Qualitative Approach to Attempted Suicide by Youth

PLOS ONE |www.plosone.org 3 May 2014 |Volume 9 |Issue 5 | e96716

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1. Shame and guilt were the feelings that adolescents evoked most

frequently during the interviews,and theirnarrativeswere

dominated by a sense ofestrangement,loneliness,and loss of

any meaning to theirlives.One participantdescribed her

feelings of loneliness with a meaningfulmetaphor:

I was alone,stretched out on the ground,I didn’t know

what to hang on to…I was looking in vain for something

to hang on to, but I failed…essentially I was alone… (F3).

1. From almost every adolescent’s account emerged the feeling of

trapped in a suffering present,with no better future possible.

They described feeling as if they were in a blind alley, had no

more energy,and were completely surrounded,vanquished;

they felt it was impossible to find a viable alternative to get out

of their situation and give their life a different meaning.One

girl’s question bluntly demonstrated the disintegration ofthe

meaning of her life:‘‘whatam I doing in this life?’’(F2):

I thoughtto myself:‘whatam I doing in thislife?’…I

didn’tacceptmyself,I wasn’taccepted by my family

and…so, I was depressed, I was depressed in that period,

that’s for sure…because for me it was really finished…I

wanted to finish it,I’d had enough (F2).

1. The suicidalactappeared salvational,a way to free oneself

from an intolerable condition.Participants thus used positive

adjectivesto describewhat they were seeking(air, light,

freedom),expressing the hope that their act would lead them

out of the impasse in which they felt trapped.

I only saw blacknessaround me,and perhapsthose

[suicide attempts], they were the only white things I could

see… I wanted to see the light.I was convinced that if I

died I would see white, light…a light bulb turning on…it

was a conviction I had.Because I saw everything black,

alwaysdarkness…between theblack thatI saw [that

others created around me] and the black I created around

me, I thought that dying…you know, all these attempts, I

wanted to see the light…you know,to breath… (F8).

2. Need to have some control over their lives. These

adolescents broached issues of control and mastery during the

interviews in severalways.During the period before their act,

they lived a situation thatthey perceived wasout of their

control.They described their strugglesto move beyond this

lived situation that,as we have just reported,appeared

impossibleto overcomeor resolve,that theyexperienced

passively, were subjected to. What emerged from the interview

wasthatacting on their body offered them controlof/over

their life,in contrast to allthe other uncontrollable situations

they were living.Half of the adolescents interviewed had cut

themselves as a positive action, to make themselves the actor

something in their life.

I had no controlover the others,but I had controlover

myself…so I could do what I wanted to myself …and the

cuts were a way to comfortmy pain… I stillhave the

scars– blood everywhere,I wascrying,but…butthe

problem was still there…however, during these moments

[…] it was as if I had controlof my life… (F7).

2. These adolescents lived their suicide attempt as an escape fro

an overwhelming life situation that was beyond their ability to

manage:

I said ‘that’s OK, stop, let’s finish it off, that way, I’ll put

everything straight…I won’t have to think about anything

anymore,there won’t be anythingto deal with,

and…everything willbe better.

Interviewer:Whatdo you mean by ‘‘everything willbe better’’?

Thatis, more than anything,thatthere willbe nothing

else so it will necessarily be better! […] I was glad to have

made thatdecision… Iwasglad and sure aboutmy

decision… (M7).

Figure 1. Thematic findings. Representation of themes and subthemes emerged from our analysis.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096716.g001

Qualitative Approach to Attempted Suicide by Youth

PLOS ONE |www.plosone.org 4 May 2014 |Volume 9 |Issue 5 | e96716

frequently during the interviews,and theirnarrativeswere

dominated by a sense ofestrangement,loneliness,and loss of

any meaning to theirlives.One participantdescribed her

feelings of loneliness with a meaningfulmetaphor:

I was alone,stretched out on the ground,I didn’t know

what to hang on to…I was looking in vain for something

to hang on to, but I failed…essentially I was alone… (F3).

1. From almost every adolescent’s account emerged the feeling of

trapped in a suffering present,with no better future possible.

They described feeling as if they were in a blind alley, had no

more energy,and were completely surrounded,vanquished;

they felt it was impossible to find a viable alternative to get out

of their situation and give their life a different meaning.One

girl’s question bluntly demonstrated the disintegration ofthe

meaning of her life:‘‘whatam I doing in this life?’’(F2):

I thoughtto myself:‘whatam I doing in thislife?’…I

didn’tacceptmyself,I wasn’taccepted by my family

and…so, I was depressed, I was depressed in that period,

that’s for sure…because for me it was really finished…I

wanted to finish it,I’d had enough (F2).

1. The suicidalactappeared salvational,a way to free oneself

from an intolerable condition.Participants thus used positive

adjectivesto describewhat they were seeking(air, light,

freedom),expressing the hope that their act would lead them

out of the impasse in which they felt trapped.

I only saw blacknessaround me,and perhapsthose

[suicide attempts], they were the only white things I could

see… I wanted to see the light.I was convinced that if I

died I would see white, light…a light bulb turning on…it

was a conviction I had.Because I saw everything black,

alwaysdarkness…between theblack thatI saw [that

others created around me] and the black I created around

me, I thought that dying…you know, all these attempts, I

wanted to see the light…you know,to breath… (F8).

2. Need to have some control over their lives. These

adolescents broached issues of control and mastery during the

interviews in severalways.During the period before their act,

they lived a situation thatthey perceived wasout of their

control.They described their strugglesto move beyond this

lived situation that,as we have just reported,appeared

impossibleto overcomeor resolve,that theyexperienced

passively, were subjected to. What emerged from the interview

wasthatacting on their body offered them controlof/over

their life,in contrast to allthe other uncontrollable situations

they were living.Half of the adolescents interviewed had cut

themselves as a positive action, to make themselves the actor

something in their life.

I had no controlover the others,but I had controlover

myself…so I could do what I wanted to myself …and the

cuts were a way to comfortmy pain… I stillhave the

scars– blood everywhere,I wascrying,but…butthe

problem was still there…however, during these moments

[…] it was as if I had controlof my life… (F7).

2. These adolescents lived their suicide attempt as an escape fro

an overwhelming life situation that was beyond their ability to

manage:

I said ‘that’s OK, stop, let’s finish it off, that way, I’ll put

everything straight…I won’t have to think about anything

anymore,there won’t be anythingto deal with,

and…everything willbe better.

Interviewer:Whatdo you mean by ‘‘everything willbe better’’?

Thatis, more than anything,thatthere willbe nothing

else so it will necessarily be better! […] I was glad to have

made thatdecision… Iwasglad and sure aboutmy

decision… (M7).

Figure 1. Thematic findings. Representation of themes and subthemes emerged from our analysis.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096716.g001

Qualitative Approach to Attempted Suicide by Youth

PLOS ONE |www.plosone.org 4 May 2014 |Volume 9 |Issue 5 | e96716

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2. Narratives related to the post-suicidalperiod shed light on the

failure ofthe adolescents’attempts to achieve controlof their

own lives.They talked aboutfeeling ofanger,described as a

physicaland violentrage closely linked to the failure oftheir

act, and about finding themselves in a situation they perceived

as stillmore difficult.They lived the failure of their act as yet

another demonstration oftheir ineptitude,justone more in

their long string of personalfailures.

Interviewer:Whataboutthe changes in your life [after the suicide

attempt]?

Nothing…maybe,I began to see thingsdarker[…], I

thoughtI wasn’table to do anything,that I was

afraid…now I’m tired,I can’t take it anymore,before it

wasn’tlike this […]. I began tosee everythingas

darker…I began to think thatI was wrong,thatI was

the problem…because when there is a problem now,I

give up…and before it wasn’t so. From that, I feel my life

has changed (F6).

Theme II:Relationaldimensions of the suicide attempt

The second superordinate theme is the relationaldimension of

the suicidal act. The three subthemes belonging to this domain are

described below:

3. Perceived impasse in interpersonal relationships.

Our participants’narrativesof their family relationships

focused on the description ofan impasse,a sortof gridlock

dominated by the absence ofacceptance ortrustand the

perception ofbeing written down oreven off.It seemsto

parallel the negative emotions toward the self and the perceived

impasse described above (theme 1).

Because I was changing and they didn’t realize that, they

only realized it when I ran away from home […] at the

beginning,I did it because…thatis, I didn’teven think

about it much, but then, as the hours were going by I kept

on thinking aboutit and…I don’tknow,butit was like

running away to make myself visible… (M1).

3. Theparticipantsdescribed rigid and overwhelming family

dynamics and their perception that it was impossible to escape

an unbearable situation. They also directly linked their need to

escape and their choice to attempt suicide:

‘‘When I began to make her understand thatI wasn’t

going to acceptthissituation anymore,all hell broke

loose…and then, from that, my act…since I began to tell

her ‘look, Mama, I can’t take that anymore.’ …she didn’t

acceptthat…maybe she understood I’m no longer the

baby who’s happy with a new pair ofshoes so she’llbe

good,keep quiet and make believe she’s happy…I don’t

know…’’

Interviewer: can you tell me more about the relationship between that

and your act?

I think that it is… the fundamentalrelationship…I think

that is the main reason that I did it, fundamentally… (F6).

3. The peergroup wasalso described asa source ofintense

emotions.Although thenarrativesrevealed thatthe teens

hoped their peer group might supply what their families failed

to give them,these textsalso demonstrated fragility.Some-

times,they feltthatbeing partof their peer group produced

emotions very like to those about their family life; this increase

the feelings of loneliness and of not being understood:

I felt they were superficial,and I didn’t want to keep on

pretending to be like that…I didn’t feel at ease with them,

and slowly I lost the people I went out with (M5).

3. A frequenttopic wasthe emotionalinvestmentin one core

relationship, an investment the adolescents perceived as a way

to cope with the instability and difficulties of their lives. It was

described in terms of dependency: the relationship became the

repository oftheir hopes,and the person they were involved

with,the reference point of their life:

My ex-boyfriend F. was my first one…I was sixteen…my

first sexual relationship, my first love story, it lasted 3 and

a halfyears.He was my reference,because my parents

are separated, my father is far away, and I have an awful

relationship with my mother…and he was like… like an

older brother… a father…his mother was like a mother to

me,and she was almost my mother for three and a half

year[…]. With F. I had finally found thatkind of

stability…but,I guess itwas only a stopgap,a stopgap

that covered up allmy problems…and in fact,when he

was gone,they allreappeared on the surface (F3).

4. Communication. All the participants explicitly described the

communicative issues related to their suicide attempt. It is clea

that each suicidalact was primarilyan interpersonalact,

concerning notonly theselfbut also theenvironmentof

significant others.The suicide attempt was closely linked to a

situation with which the adolescent could not deal — all efforts

were in vain. Suicide thus became the only possible way to get

the person to listen to the adolescent’s difficulties and to send

message that was impossible to deliver otherwise. The suicidal

act was described asthe only choice,once everyother

communicative possibility had failed.

I was sick and tired ofmy mother’sbehavior…and to

keep on talking was useless. I went on for several months

and kepttalkingand talkingand…thatwas hurting

me…and I was tired. And so I finally did something like

that[attempted suicide],but itwas mainly to make her

understand that she was killing me!…either she would kill

me, or…or I had to find another way […]. If I tried to do

thatthere,it’s because I had already talked aboutit in

every other way… (F4).

4. Our analysisof the narrativesaboutthe period afterthe

suicidalact found these youth travelled two differentpaths.

Those who successfullyemergedfrom the suicidalcrisis

described the firstas a progressive opening ofthe line of

communication with others,a process that established a basis

for a change in the family relationship:

Before,I didn’t even talk to her,while now we can talk

fairly peacefully…aboutschool,or work…thatkind of

thing…we alwaysspoke aboutmy past,and we each

understood … whatshe feltand whatI felt…yeah,we

talked about that […] I told her what I had been doing in

[thattown],whatI wasdoing,whatsubstancesI was

taking…and she told me she was always crying,that she

was desperate,alwaysworrying,that she had done

everything possible to make me come back home again

Qualitative Approach to Attempted Suicide by Youth

PLOS ONE |www.plosone.org 5 May 2014 |Volume 9 |Issue 5 | e96716

failure ofthe adolescents’attempts to achieve controlof their

own lives.They talked aboutfeeling ofanger,described as a

physicaland violentrage closely linked to the failure oftheir

act, and about finding themselves in a situation they perceived

as stillmore difficult.They lived the failure of their act as yet

another demonstration oftheir ineptitude,justone more in

their long string of personalfailures.

Interviewer:Whataboutthe changes in your life [after the suicide

attempt]?

Nothing…maybe,I began to see thingsdarker[…], I

thoughtI wasn’table to do anything,that I was

afraid…now I’m tired,I can’t take it anymore,before it

wasn’tlike this […]. I began tosee everythingas

darker…I began to think thatI was wrong,thatI was

the problem…because when there is a problem now,I

give up…and before it wasn’t so. From that, I feel my life

has changed (F6).

Theme II:Relationaldimensions of the suicide attempt

The second superordinate theme is the relationaldimension of

the suicidal act. The three subthemes belonging to this domain are

described below:

3. Perceived impasse in interpersonal relationships.

Our participants’narrativesof their family relationships

focused on the description ofan impasse,a sortof gridlock

dominated by the absence ofacceptance ortrustand the

perception ofbeing written down oreven off.It seemsto

parallel the negative emotions toward the self and the perceived

impasse described above (theme 1).

Because I was changing and they didn’t realize that, they

only realized it when I ran away from home […] at the

beginning,I did it because…thatis, I didn’teven think

about it much, but then, as the hours were going by I kept

on thinking aboutit and…I don’tknow,butit was like

running away to make myself visible… (M1).

3. Theparticipantsdescribed rigid and overwhelming family

dynamics and their perception that it was impossible to escape

an unbearable situation. They also directly linked their need to

escape and their choice to attempt suicide:

‘‘When I began to make her understand thatI wasn’t

going to acceptthissituation anymore,all hell broke

loose…and then, from that, my act…since I began to tell

her ‘look, Mama, I can’t take that anymore.’ …she didn’t

acceptthat…maybe she understood I’m no longer the

baby who’s happy with a new pair ofshoes so she’llbe

good,keep quiet and make believe she’s happy…I don’t

know…’’

Interviewer: can you tell me more about the relationship between that

and your act?

I think that it is… the fundamentalrelationship…I think

that is the main reason that I did it, fundamentally… (F6).

3. The peergroup wasalso described asa source ofintense

emotions.Although thenarrativesrevealed thatthe teens

hoped their peer group might supply what their families failed

to give them,these textsalso demonstrated fragility.Some-

times,they feltthatbeing partof their peer group produced

emotions very like to those about their family life; this increase

the feelings of loneliness and of not being understood:

I felt they were superficial,and I didn’t want to keep on

pretending to be like that…I didn’t feel at ease with them,

and slowly I lost the people I went out with (M5).

3. A frequenttopic wasthe emotionalinvestmentin one core

relationship, an investment the adolescents perceived as a way

to cope with the instability and difficulties of their lives. It was

described in terms of dependency: the relationship became the

repository oftheir hopes,and the person they were involved

with,the reference point of their life:

My ex-boyfriend F. was my first one…I was sixteen…my

first sexual relationship, my first love story, it lasted 3 and

a halfyears.He was my reference,because my parents

are separated, my father is far away, and I have an awful

relationship with my mother…and he was like… like an

older brother… a father…his mother was like a mother to

me,and she was almost my mother for three and a half

year[…]. With F. I had finally found thatkind of

stability…but,I guess itwas only a stopgap,a stopgap

that covered up allmy problems…and in fact,when he

was gone,they allreappeared on the surface (F3).

4. Communication. All the participants explicitly described the

communicative issues related to their suicide attempt. It is clea

that each suicidalact was primarilyan interpersonalact,

concerning notonly theselfbut also theenvironmentof

significant others.The suicide attempt was closely linked to a

situation with which the adolescent could not deal — all efforts

were in vain. Suicide thus became the only possible way to get

the person to listen to the adolescent’s difficulties and to send

message that was impossible to deliver otherwise. The suicidal

act was described asthe only choice,once everyother

communicative possibility had failed.

I was sick and tired ofmy mother’sbehavior…and to

keep on talking was useless. I went on for several months

and kepttalkingand talkingand…thatwas hurting

me…and I was tired. And so I finally did something like

that[attempted suicide],but itwas mainly to make her

understand that she was killing me!…either she would kill

me, or…or I had to find another way […]. If I tried to do

thatthere,it’s because I had already talked aboutit in

every other way… (F4).

4. Our analysisof the narrativesaboutthe period afterthe

suicidalact found these youth travelled two differentpaths.

Those who successfullyemergedfrom the suicidalcrisis

described the firstas a progressive opening ofthe line of

communication with others,a process that established a basis

for a change in the family relationship:

Before,I didn’t even talk to her,while now we can talk

fairly peacefully…aboutschool,or work…thatkind of

thing…we alwaysspoke aboutmy past,and we each

understood … whatshe feltand whatI felt…yeah,we

talked about that […] I told her what I had been doing in

[thattown],whatI wasdoing,whatsubstancesI was

taking…and she told me she was always crying,that she

was desperate,alwaysworrying,that she had done

everything possible to make me come back home again

Qualitative Approach to Attempted Suicide by Youth

PLOS ONE |www.plosone.org 5 May 2014 |Volume 9 |Issue 5 | e96716

[…] So,I realized that I had made her suffer so much,

and that she had done so much for me…to help me, but I

didn’trealize that… I wasn’tgoing to listen to her,or

even give a damn,… because I believed that she couldn’t

possibly succeed in understanding me… (F1).

4. Thisexcerptshowsthatthe communication thatdeveloped

afterthe suicide attemptled to the explicitrecognition of

feelings,emotions,and thoughts that had been present before

the attempt,but neversuccessfullycommunicated.It is

important to note that it was not a dialogue about the suicidal

act,but an attempt at mutualunderstanding.

4. The second path was that of the adolescents who described a

situation in which dialogue and communication remained as

impossible after the suicide attempt as it has been before. The

communication so unambiguously embedded in the attempt

remained unanswered.The indifferencedescribed bythe

participants— including,for some,theirfamily’srefusalto

admit they had attemptedsuicide— had the effectof

reinforcing the feelings that led to the attempt.

They didn’tcreate a good situation…they actlike they

did when I crashed the car when I was drunk… They rub

it in thatthey can’teven fallasleep atnight,they rub

everything in,they were really fullof hatred…and every

time I did it [attempted suicide],it wasalwaysworse,

because they were increasingly irritated,and I increas-

ingly hated them…and so…the situation just kept getting

worse (F7).

5. Revenge.A strong relationalthemethat the participants

described explicitly was revenge. Several adolescents explained

the aggressiveness oftheir act as a way to make other people

feel guilty for their deaths and made the vindictive intent of the

attempted suicide very plain,as the following excerpt shows:

I was convinced,utterly convinced…yeah,yeah,I want

to do it…revenge!Revenge!

Interviewer: can you explain to me a little better, revenge? What were

you thinking?

So, it means…this is what you’ve gotten by behaving like

this to me all these years…you’ve gotten only my hatred,

my contempt…my contempt for life…and…and now you

look at me…look at me and suffer (F5).

5. Revenge carries a message,one intended to make the others

aware oftheirmistakes,theircarelessness.One adolescent

described itas a communication thatwas impossibleto

misunderstand:findingher body will causeher parents

‘‘suffering,crying,andregret’’(F5).It almostappearsthatshe

expects to be present to witness the scene. It is a way to put the

blame on others and make them feelguilty through remorse:

I can’t fully understandwhy I did it [attempted

suicide]…butif I think aboutit, I honestly would say

thatI did it to punish her[my mother]…to pay her

back… (F4).

I wanted to die, I wanted to die to make my ex feel guilty,

to make my parents feelguilty,thatthey hadn’tknown

how to listen to me when I needed… I also wanted to

make others feelguilty…I wanted to die,yes,because I

wassuffering,but at the same time I wanted to make

them feel guilty … make them feel like shit…I wanted to

make them cry,I wanted to destroy their lives…(F5).

…I’ve thoughta lot aboutit…severaldaysor weeks

before, I was thinking, but not about how to do it or what

to do…butonly how to revenge myselfon them.They

made me sufferso much and now they were sitting

around calmly,as if nothing had happened…allright.

They had ruined my life and did not even realize it. So, I

had no other choice…to make them understand (M4).

Discussion

Our phenomenologicalanalysisof young adults’accountsof

their suicideattemptselicited fivethemesthat described the

experiencesthey lived.These themeswere organized into two

superordinate themes,according to whether they concerned the

individualor the relationaldimensionsthatemerged from the

narratives.We showedthat the attemptsto link the two

dimensions — to communicate their anguish —were a key aspect

of our participants’experience.The vengefulmeaning ofsuicide

that we found exemplifiesthis attemptto reach a relational

dimension, to hurt someone else by hurting oneself. Accordingly t

Knoll [26],revenge is an intense and pervasive emotion that has

nevertheless received little attention,especially in the domain of

youthfulsuicidalbehavior.Our findings showed that revenge is a

strong other-directed emotion,which aimsto communicate an

individual’s own internal state by inflicting permanent suffering on

others — by suicide. This revenge, moreover, is not only directed

at otherbut is also a meansof relieving one’sown intense

experience of internalstruggle and helplessness.

Clinicians caring for suicidaladolescents need to acknowledge

the violence (aggressiveness and revenge)inherent in the suicidal

act. It is not obvious for them to think about violence, aggression,

and revenge when they are confronted with these teens. This stud

provides an opportunity to illuminate this aspectof suicide and

make clinicians aware ofthe role ofthis powerfulemotion.We

argue that openly addressing this issue with adolescents themselv

and their familiesmay play an essentialrole helpingthem

recognize the multiple factors (both individualand relational,as

we showed) that led to a particular suicide attempt, to put things

perspective (clarifying the individual/relationalconfusion),and

begin the processof moving beyond the crisisand avoiding a

repetition.

Comparison with the literature

Our findings are consistent with previous work. The subthemes

of the first theme (individual dimension of attempted suicide) sho

the subjective experience ofloneliness,isolation,and negative

emotions toward the self. The experience of suicidal acts describe

by adolescents is primarily a solitary experience involving the loss

of any meaning in life and the impossibility of finding another way

to exit a perceived impasse. Studies focusing on the internal world

of the suicidal adolescent have consistently demonstrated negativ

emotionalexperiences[17,27,28].We show thatthe need to

recover controlover one’s own life plays an important role in the

decision to killoneself,as others have found [9,18,28] for people

involved in non-suicidalself-harming behaviors [29].

The subthemesof the second theme dealwith the relational

dimensions ofthe act.Adolescents described the meaning ofthe

situation thatled to their decision toattemptsuicidewith

interpersonalexplanations,such as a lack of communication with

their family and peers,a sense ofnot belonging to either group,

and the impossibility they feltof overcoming an interpersonal

Qualitative Approach to Attempted Suicide by Youth

PLOS ONE |www.plosone.org 6 May 2014 |Volume 9 |Issue 5 | e96716

and that she had done so much for me…to help me, but I

didn’trealize that… I wasn’tgoing to listen to her,or

even give a damn,… because I believed that she couldn’t

possibly succeed in understanding me… (F1).

4. Thisexcerptshowsthatthe communication thatdeveloped

afterthe suicide attemptled to the explicitrecognition of

feelings,emotions,and thoughts that had been present before

the attempt,but neversuccessfullycommunicated.It is

important to note that it was not a dialogue about the suicidal

act,but an attempt at mutualunderstanding.

4. The second path was that of the adolescents who described a

situation in which dialogue and communication remained as

impossible after the suicide attempt as it has been before. The

communication so unambiguously embedded in the attempt

remained unanswered.The indifferencedescribed bythe

participants— including,for some,theirfamily’srefusalto

admit they had attemptedsuicide— had the effectof

reinforcing the feelings that led to the attempt.

They didn’tcreate a good situation…they actlike they

did when I crashed the car when I was drunk… They rub

it in thatthey can’teven fallasleep atnight,they rub

everything in,they were really fullof hatred…and every

time I did it [attempted suicide],it wasalwaysworse,

because they were increasingly irritated,and I increas-

ingly hated them…and so…the situation just kept getting

worse (F7).

5. Revenge.A strong relationalthemethat the participants

described explicitly was revenge. Several adolescents explained

the aggressiveness oftheir act as a way to make other people

feel guilty for their deaths and made the vindictive intent of the

attempted suicide very plain,as the following excerpt shows:

I was convinced,utterly convinced…yeah,yeah,I want

to do it…revenge!Revenge!

Interviewer: can you explain to me a little better, revenge? What were

you thinking?

So, it means…this is what you’ve gotten by behaving like

this to me all these years…you’ve gotten only my hatred,

my contempt…my contempt for life…and…and now you

look at me…look at me and suffer (F5).

5. Revenge carries a message,one intended to make the others

aware oftheirmistakes,theircarelessness.One adolescent

described itas a communication thatwas impossibleto

misunderstand:findingher body will causeher parents

‘‘suffering,crying,andregret’’(F5).It almostappearsthatshe

expects to be present to witness the scene. It is a way to put the

blame on others and make them feelguilty through remorse:

I can’t fully understandwhy I did it [attempted

suicide]…butif I think aboutit, I honestly would say

thatI did it to punish her[my mother]…to pay her

back… (F4).

I wanted to die, I wanted to die to make my ex feel guilty,

to make my parents feelguilty,thatthey hadn’tknown

how to listen to me when I needed… I also wanted to

make others feelguilty…I wanted to die,yes,because I

wassuffering,but at the same time I wanted to make

them feel guilty … make them feel like shit…I wanted to

make them cry,I wanted to destroy their lives…(F5).

…I’ve thoughta lot aboutit…severaldaysor weeks

before, I was thinking, but not about how to do it or what

to do…butonly how to revenge myselfon them.They

made me sufferso much and now they were sitting

around calmly,as if nothing had happened…allright.

They had ruined my life and did not even realize it. So, I

had no other choice…to make them understand (M4).

Discussion

Our phenomenologicalanalysisof young adults’accountsof

their suicideattemptselicited fivethemesthat described the

experiencesthey lived.These themeswere organized into two

superordinate themes,according to whether they concerned the

individualor the relationaldimensionsthatemerged from the

narratives.We showedthat the attemptsto link the two

dimensions — to communicate their anguish —were a key aspect

of our participants’experience.The vengefulmeaning ofsuicide

that we found exemplifiesthis attemptto reach a relational

dimension, to hurt someone else by hurting oneself. Accordingly t

Knoll [26],revenge is an intense and pervasive emotion that has

nevertheless received little attention,especially in the domain of

youthfulsuicidalbehavior.Our findings showed that revenge is a

strong other-directed emotion,which aimsto communicate an

individual’s own internal state by inflicting permanent suffering on

others — by suicide. This revenge, moreover, is not only directed

at otherbut is also a meansof relieving one’sown intense

experience of internalstruggle and helplessness.

Clinicians caring for suicidaladolescents need to acknowledge

the violence (aggressiveness and revenge)inherent in the suicidal

act. It is not obvious for them to think about violence, aggression,

and revenge when they are confronted with these teens. This stud

provides an opportunity to illuminate this aspectof suicide and

make clinicians aware ofthe role ofthis powerfulemotion.We

argue that openly addressing this issue with adolescents themselv

and their familiesmay play an essentialrole helpingthem

recognize the multiple factors (both individualand relational,as

we showed) that led to a particular suicide attempt, to put things

perspective (clarifying the individual/relationalconfusion),and

begin the processof moving beyond the crisisand avoiding a

repetition.

Comparison with the literature

Our findings are consistent with previous work. The subthemes

of the first theme (individual dimension of attempted suicide) sho

the subjective experience ofloneliness,isolation,and negative

emotions toward the self. The experience of suicidal acts describe

by adolescents is primarily a solitary experience involving the loss

of any meaning in life and the impossibility of finding another way

to exit a perceived impasse. Studies focusing on the internal world

of the suicidal adolescent have consistently demonstrated negativ

emotionalexperiences[17,27,28].We show thatthe need to

recover controlover one’s own life plays an important role in the

decision to killoneself,as others have found [9,18,28] for people

involved in non-suicidalself-harming behaviors [29].

The subthemesof the second theme dealwith the relational

dimensions ofthe act.Adolescents described the meaning ofthe

situation thatled to their decision toattemptsuicidewith

interpersonalexplanations,such as a lack of communication with

their family and peers,a sense ofnot belonging to either group,

and the impossibility they feltof overcoming an interpersonal

Qualitative Approach to Attempted Suicide by Youth

PLOS ONE |www.plosone.org 6 May 2014 |Volume 9 |Issue 5 | e96716

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

stalemate.Moreover,they recounted changesthatthe primary

suicidalact produced (or failed to produce)in their interpersonal

world that eventuallyenabledimportantrelationshipsto be

restructuredin ways that, for example,increasedmutual

understanding.Severalauthorshave investigated the relational

aspects of suicide attempts in various populations, including LGBT

[30], ethnicminorities[31], and depressed adolescents[32].

Consistentlywith our findings,thesestudiespointed outthe

importance ofinterpersonalrelations in understanding both the

reasonsfor suicideattemptsand the patternsof recovery in

adolescent suicidalbehavior.

We go further,however.Althoughpreviousstudieshave

mentioned the relation between the individualand interpersonal

dimensions of suicidalacts, they have not discussed it clearly, and

severalgaps remain.The hypothesis we propose,which emerges

from ourfindings,is thatconfusion existsbetween these two

dimensions.Adolescentscontinually try to link theirindividual

stateof personaldistress,helplessness,and lonelinessto the

presence of others, seeking to connect. They described situations in

which their unhappinessis not recognized or acknowledged by

others. Our findings suggest that for adolescents suicidal behavior

representsa meansof establishing a connection between their

personal distress and the others, through the act itself. Revenge, as

discussed above,is one way to do that.

Moreover,failure to establish thatlink appears to be a major

factor responsible for keeping the adolescent in the same state of

mind that led to the initial act and thus keeps him or her at risk for

repeating it.

Limitations

This study hastwo main limitations.The firstconcernsits

generalizability.Our purposive sampling procedure allowed us to

include a wide sample ofexperiencesamong young men and

women,with both single and multiple suicidalacts,of different

durations of time since the act,and initially treated at 3 different

hospitals.Nonetheless,our findingscan be generalized only to

young Italian adults, and attitudes may differ in other countries or

even in otherregionsof Italy. However,our methodological

precautions assure the trustworthiness of our findings. Because th

socio-culturalenvironmenthas a strong influenceon suicidal

behaviors [31], further research needs to be conducted to compar

and integrate perspectivesfrom severalcountries.The second

limitation isthatall the participantswere contacted through a

healthcare facility where they underwent a period of psychiatric o

psychologicaltreatment.This mighthave affected the way that

they retrospectively understood their act

Conclusion and perspectives for future research

Adolescent suicidalbehavior appears to be a relationalact that

aims to bridge a gap between the adolescents and their significan

others in order to resolve a perceived impasse.Failure – by the

others and by the therapist – to recognize this intent and take it

into accountappearsto be a key factorfor repetition ofthis

behavior. Revenge assumes a particular role that appears to have

been neglected by both clinicians and researchers untilnow,and

further research should address this issue. Additionally, qualitativ

studies should be conducted to understand both caregivers’and

health-care professionals’ perspectives about the issue of revenge

adolescent suicide attempts.

Supporting Information

Table S1 COREQ checklist.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank: all participants in this research, the heads and staff

of the departments in which the research had been conducted (especially,

Dr Marco Previdiand Dr Maria Grazia Covre, Santa Giuliana Hospital,

Verona),and Ms JoAnn Cahn for revision of the English.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed theexperiments:MO MP. Performed the

experiments:MO MP. Analyzed the data:MO MP ARL JL JS BF.

Wrote the paper:MO MP ARL JL JS BF.

References

1. WHO | Suicide prevention (SUPRE).WHO. Available:http://www.who.int/

mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/. Accessed 2 May 2013.

2. Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Flint KH, et al.(2012)Youth risk

behavior surveillance -United States,2011.Morb MortalWkly Rep Surveill

Summ Wash DC 2002 61:1–162.

3. Kaess M, Brunner R (2012) Prevalence of adolescents’ suicide attempts and self-

harm thoughts vary across Europe.Evid Based Ment Health 15:66.

4. Hawton K, Arensman E, Wasserman D, Hulten A, Bille-Brahe U, et al. (1998)

Relation between attempted suicide and suicide rates among young people in

Europe.J EpidemiolCommunity Health 52:191–194.

5. Council of Europe (2008) Child and teenage suicide in Europe: A serious public-

healthissue.Available:http://assembly.coe.int/ASP/Doc/XrefViewPDF.

asp?FileID = 17639&Language = EN.Accessed 2 May 2013.

6. Hawton K, Hall S, Simkin S, Bale L, Bond A, et al. (2003) Deliberate self-harm

in adolescents:a study ofcharacteristicsand trendsin Oxford,1990–2000.

J Child PsycholPsychiatry 44:1191–1198.

7. Scottish Executive SAH (2008) Effectiveness of Interventions to Prevent Suicide

and SuicidalBehaviour: A Systematic Review. Available: http://www.scotland.

gov.uk/Publications/2008/01/15102257/0.Accessed 2 July 2013.

8. Tyrer P, Thompson S, Schmidt U, Jones V, Knapp M, et al. (2003) Randomized

controlled trialof brief cognitive behaviour therapy versus treatment as usualin

recurrent deliberate self-harm: the POPMACT study. Psychol Med 33: 969–976.

9. Hawton K,Bergen H,Kapur N,Cooper J,Steeg S,et al.(2012)Repetition of

self-harm and suicide following self-harm in children and adolescents:findings

from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. J Child Psychol Psychiatry

53:1212–1219.

10. Chitsabesan P,Harrington R,Harrington V,Tomenson B (2003)Predicting

repeatself-harm in children—how accurate can we expectto be? Eur Child

Adolesc Psychiatry 12:23–29.

11. Cash SJ, Bridge JA (2009) Epidemiology of youth suicide and suicidal behavior.

Curr Opin Pediatr 21:613–619.

12. Hawton K,Harriss L (2007)Deliberate self-harm in young people:character-

isticsand subsequentmortality in a 20-year cohortof patientspresenting to

hospital.J Clin Psychiatry 68:1574–1583.

13. Connor J, Rueter M (2009) Predicting adolescent suicidality: comparing multiple

informants and assessment techniques.J Adolesc 32:619–631.