Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and Solutions in Microsurgery Practice

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/25

|8

|4273

|343

Report

AI Summary

This report, based on a survey of plastic surgeons in East, Central, and Southern Africa, investigates the challenges faced in global reconstructive microsurgery within the sub-Saharan region. The study, which had a 56% response rate, highlights key issues such as inadequate perioperative care due to a shortage of support staff, lack of surgical expertise, insufficient equipment, and public unawareness of the benefits of microsurgery. The research emphasizes the need for enhanced training through a multidisciplinary team approach, increased advocacy, publications, and funding to improve microsurgical practices. The findings underscore the importance of addressing these challenges to advance reconstructive surgery in the region, with a focus on improving outcomes and expanding access to this essential medical technique. The survey results identified Kenya and Uganda as having surgeons performing more than 10 cases annually, with most participants emphasizing the importance of microsurgery in the region.

JPRAS Open 20 (2019) 19–26

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

JPRAS Open

journal homepage:www.elsevier.com/locate/jpra

Original Article

Challengesin global reconstructivemicrosurgery:

The sub-Saharanafrican surgeons’perspective

Chihena H. Bandaa,b,∗, Pafitanis Georgiosc,

Mitsunaga Narushimaa, Ryohei Ishiuraa, Minami Fujitaa,

Jovic Gorand

a Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Mie University, Tsu, Japan

b Department of Surgery, Arthur Davison Children’s Hospital, Ndola, Zambia

c Group for Academic Plastic Surgery, The Royal London Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust, Queen Mary

University of London, London, UK

d Department of Surgery, The University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 20 November 2018

Accepted 20 January 2019

Available online 4 February 2019

Keywords:

Microsurgery

Free tissue transfer

Africa

Challenges

Training

Global surgery

a b s t r a c t

Background:Microsurgeryis an essentialelementof plastic surgery

practice.However,it remainsunavailableor rudimentaryin several

developingcountries, especially in sub-SaharanAfrica. This study

presents the local plastic surgeons experience,while focusing on

specific challengesencounteredand methods to improve the sub-

Saharanglobal microsurgerypractice.

Methodology: An online survey was sent to all plastic surgeons

registeredwith the College of SurgeonsEast Central and Southern

Africa and respectivenational plastic surgical societiesin the east

central and southern Africa regional community. A total of 57

questionnaireswere sent. Surgeons’country of practice, years of

experienceand rate of performing microsurgicalprocedureswere

considered.

∗ Corresponding author: Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Mie University,

2-174 Edobashi, Tsu, Mie Prefecture, 514-8507, JAPAN.

E-mail addresses: 318001c@m.mie-u.ac.jp , chihenab@gmail.com (C.H. Banda).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpra.2019.01.009

2352-5878/© 2019 The Author(s).Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of British Association of Plastic,Reconstructive and

Aesthetic Surgeons. This is an open access article under the CC BY license. ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ )

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

JPRAS Open

journal homepage:www.elsevier.com/locate/jpra

Original Article

Challengesin global reconstructivemicrosurgery:

The sub-Saharanafrican surgeons’perspective

Chihena H. Bandaa,b,∗, Pafitanis Georgiosc,

Mitsunaga Narushimaa, Ryohei Ishiuraa, Minami Fujitaa,

Jovic Gorand

a Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Mie University, Tsu, Japan

b Department of Surgery, Arthur Davison Children’s Hospital, Ndola, Zambia

c Group for Academic Plastic Surgery, The Royal London Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust, Queen Mary

University of London, London, UK

d Department of Surgery, The University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 20 November 2018

Accepted 20 January 2019

Available online 4 February 2019

Keywords:

Microsurgery

Free tissue transfer

Africa

Challenges

Training

Global surgery

a b s t r a c t

Background:Microsurgeryis an essentialelementof plastic surgery

practice.However,it remainsunavailableor rudimentaryin several

developingcountries, especially in sub-SaharanAfrica. This study

presents the local plastic surgeons experience,while focusing on

specific challengesencounteredand methods to improve the sub-

Saharanglobal microsurgerypractice.

Methodology: An online survey was sent to all plastic surgeons

registeredwith the College of SurgeonsEast Central and Southern

Africa and respectivenational plastic surgical societiesin the east

central and southern Africa regional community. A total of 57

questionnaireswere sent. Surgeons’country of practice, years of

experienceand rate of performing microsurgicalprocedureswere

considered.

∗ Corresponding author: Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Mie University,

2-174 Edobashi, Tsu, Mie Prefecture, 514-8507, JAPAN.

E-mail addresses: 318001c@m.mie-u.ac.jp , chihenab@gmail.com (C.H. Banda).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpra.2019.01.009

2352-5878/© 2019 The Author(s).Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of British Association of Plastic,Reconstructive and

Aesthetic Surgeons. This is an open access article under the CC BY license. ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ )

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

20 C.H. Banda, P. Georgios and M. Narushima et al. / JPRAS Open 20 (2019) 19–26

Results: The survey responserate was 56%(n = 32). Most partici-

pants believedmicrosurgerywas essentialin the region. The lead-

ing challengewas inadequateperioperativecare,mainly attributed

to shortageof support staff (n = 29, 91%).Others were lack of sur-

gical expertiseand resources.Interestingly,public unawarenessof

the benefitsof microsurgerywas also noted as a critical hindrance.

The foremost suggestionon improvement(n = 19, 59%)was to en-

hance training with a multidisciplinary team-building approach.

Others included increasedadvocacy,publicationsand funding.

Conclusion: The Plastic surgeons’perspectiverecognizesthe needs

of Global ReconstructiveMicrosurgeryin sub-SaharanAfrica. How-

ever, inadequateperioperativecare, insufficient expertise,lack of

equipment and lack of public awarenesswere major hindrances.

Finally, there is a need to improve microsurgery in the region

through advocacy,training and multidisciplinaryteam building.

© 2019The Author(s).Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of

British Associationof Plastic,Reconstructiveand Aesthetic

Surgeons.

This is an open accessarticle under the CC BY license.

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Introduction

Microsurgery is an essential component of modern plastic reconstructivesurgery. The technique

facilitatesfree tissue transfer providing optimal functional and aestheticrecoveryfor a wide range of

complex tissue defects.Although traditionally pioneered by plastic surgeons,microsurgeryhas since

progressedand is increasinglybeing utilized by other specialitiessuch as otolaryngology,orthopaedics

and neurosurgery.With the current refinementsin techniqueand materials,the successrates of free

flaps in developedcountries are as high as 97%–99%.1,2 However,there is a growing gap between de-

veloped and developingcountries,with microsurgerycompletelyunavailableor rudimentary in many

developingcountries,particularly in the east, central and southern Africa (ECSA) region.3

Excluding South Africa, there are scarcely any reports on microsurgical free tissue transfer per-

formed in sub-SaharanAfrica. A few proceduresare occasionallyperformed by surgeonsvisiting from

developed countries with variable results.4–7 Nevertheless,local teams most notably in Kenya and

Uganda have overcomethe numerous challengesand have published their experiencesin a resource-

limited setting not indifferent from those found in other developing countries.3,6 Operations in the

region have largely been electivereconstructiveproceduresmost commonly for head and neck pathol-

ogy, such as cancer,noma and post-burn contracture,with the most frequentlyutilized flaps being the

radial forearm, free fibular and anterolateralthigh flaps.3–6 ,8 Nangole et al. reported using relatively

inexpensivemethods in Kenya including a basic microsurgeryset along with surgical loupes to per-

form free tissue transfers.3 However, such methods have attracted a mixed response of both praise

and criticism from the global community.9

Severalchallengesto performing microsurgeryin the region have been noted from the publications

of individual units and visiting surgeons.These include poor postoperativemonitoring, lack of high-

quality equipment and a lack of surgical skill together resulting in relatively low free flap survival

rates of 76%–89%.3,6,7 However,there is a paucity of literature objectively assessingthese challenges

particularly in countries that do not often practicemicrosurgery.Additionally,the perceivedchallenges

noted from individual unit experiencesdiffer widely. For instance,Citron et al.6 found equivocalflap

survival rates in casesperformed in Ugandabetweenlocal surgeonsand experiencedvisiting surgeons

from developedcountries suggestinglack of surgical skill3 may not be the prime cause of stagnation.

This highlights the crucial need to further explore the causesof suboptimal results in the region.

Results: The survey responserate was 56%(n = 32). Most partici-

pants believedmicrosurgerywas essentialin the region. The lead-

ing challengewas inadequateperioperativecare,mainly attributed

to shortageof support staff (n = 29, 91%).Others were lack of sur-

gical expertiseand resources.Interestingly,public unawarenessof

the benefitsof microsurgerywas also noted as a critical hindrance.

The foremost suggestionon improvement(n = 19, 59%)was to en-

hance training with a multidisciplinary team-building approach.

Others included increasedadvocacy,publicationsand funding.

Conclusion: The Plastic surgeons’perspectiverecognizesthe needs

of Global ReconstructiveMicrosurgeryin sub-SaharanAfrica. How-

ever, inadequateperioperativecare, insufficient expertise,lack of

equipment and lack of public awarenesswere major hindrances.

Finally, there is a need to improve microsurgery in the region

through advocacy,training and multidisciplinaryteam building.

© 2019The Author(s).Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of

British Associationof Plastic,Reconstructiveand Aesthetic

Surgeons.

This is an open accessarticle under the CC BY license.

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Introduction

Microsurgery is an essential component of modern plastic reconstructivesurgery. The technique

facilitatesfree tissue transfer providing optimal functional and aestheticrecoveryfor a wide range of

complex tissue defects.Although traditionally pioneered by plastic surgeons,microsurgeryhas since

progressedand is increasinglybeing utilized by other specialitiessuch as otolaryngology,orthopaedics

and neurosurgery.With the current refinementsin techniqueand materials,the successrates of free

flaps in developedcountries are as high as 97%–99%.1,2 However,there is a growing gap between de-

veloped and developingcountries,with microsurgerycompletelyunavailableor rudimentary in many

developingcountries,particularly in the east, central and southern Africa (ECSA) region.3

Excluding South Africa, there are scarcely any reports on microsurgical free tissue transfer per-

formed in sub-SaharanAfrica. A few proceduresare occasionallyperformed by surgeonsvisiting from

developed countries with variable results.4–7 Nevertheless,local teams most notably in Kenya and

Uganda have overcomethe numerous challengesand have published their experiencesin a resource-

limited setting not indifferent from those found in other developing countries.3,6 Operations in the

region have largely been electivereconstructiveproceduresmost commonly for head and neck pathol-

ogy, such as cancer,noma and post-burn contracture,with the most frequentlyutilized flaps being the

radial forearm, free fibular and anterolateralthigh flaps.3–6 ,8 Nangole et al. reported using relatively

inexpensivemethods in Kenya including a basic microsurgeryset along with surgical loupes to per-

form free tissue transfers.3 However, such methods have attracted a mixed response of both praise

and criticism from the global community.9

Severalchallengesto performing microsurgeryin the region have been noted from the publications

of individual units and visiting surgeons.These include poor postoperativemonitoring, lack of high-

quality equipment and a lack of surgical skill together resulting in relatively low free flap survival

rates of 76%–89%.3,6,7 However,there is a paucity of literature objectively assessingthese challenges

particularly in countries that do not often practicemicrosurgery.Additionally,the perceivedchallenges

noted from individual unit experiencesdiffer widely. For instance,Citron et al.6 found equivocalflap

survival rates in casesperformed in Ugandabetweenlocal surgeonsand experiencedvisiting surgeons

from developedcountries suggestinglack of surgical skill3 may not be the prime cause of stagnation.

This highlights the crucial need to further explore the causesof suboptimal results in the region.

C.H. Banda, P. Georgios and M. Narushima et al. / JPRAS Open 20 (2019) 19–26 21

On the positive side, the number of plastic surgeonsin the ECSA region is rapidly growing, largely

due to efforts in regional cooperation of surgical training fostered by the College of SurgeonsEast

Central and Southern Africa (COSECSA)and its partners.10,11 Consideringthis, coupled with the posi-

tive economic growth seen over the last decade,12,13 microsurgeryis poised to play a greater part in

reconstructivesurgery in this region in the years to come.

The aim of this study was to assessthe opinions of local plastic surgeonson the challengesfaced

practising microsurgeryin the ECSA region and how to improve the service.

Methodology

An anonymous survey (5-point Likert-style) was sent to all plastic surgeons registered with

COSECSA.Additional invitations were sent to all plastic surgeonsregisteredwith respectivenational

plastic surgeryassociations/societiesto ensuresurgeonsnot part of the regional collegewere also con-

tacted.The countries forming the ECSA region included in this survey were; Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya,

Malawi, Mozambique,Namibia, Rwanda,South Sudan,Tanzania,Uganda,Zambia and Zimbabwe.Sur-

geons from Namibia were contacted individually, as the country only recently joined the regional

body. A total of 57 surgeonswere invited. Plastic surgeonsresident and practising in the region (in-

cluding academic and administrativepositions) as of July 1, 2018, were included in this study. All

surgeonswithout permanentresidencyin the region, such as visiting surgeons,charity missions and

COSECSAoverseasfellows, were excluded.Email reminders were sent after 2 weeks and 4 weeks to

encourageparticipation.

Data were collected for country of clinical practice,years of experience,number of microsurgery

procedures performed over the last 5 years, opinions on the challengesof microsurgery and sug-

gestions for improvement. The survey was delivered through an online platform, Google Forms

(https://goo.gl/forms/nKnhD1MzFNN1Gxgh1). Respondentswere grouped into two groups by country

of practice: countries with surgeonsreporting > 10 microsurgicalproceduresannually were assigned

to study Group A and the rest to Group B.

All survey questionswere digitalisedand analysedusing IBM SPSSStatistics25 (IBM Corp. Released

2017.IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Data were analysed

depending on country group and surgeons’years of experienceusing two-tailed Mann–Whitney U

and Kruskal–Wallis tests,respectively.Statisticalsignificancewas defined as P < 0.05.

Results

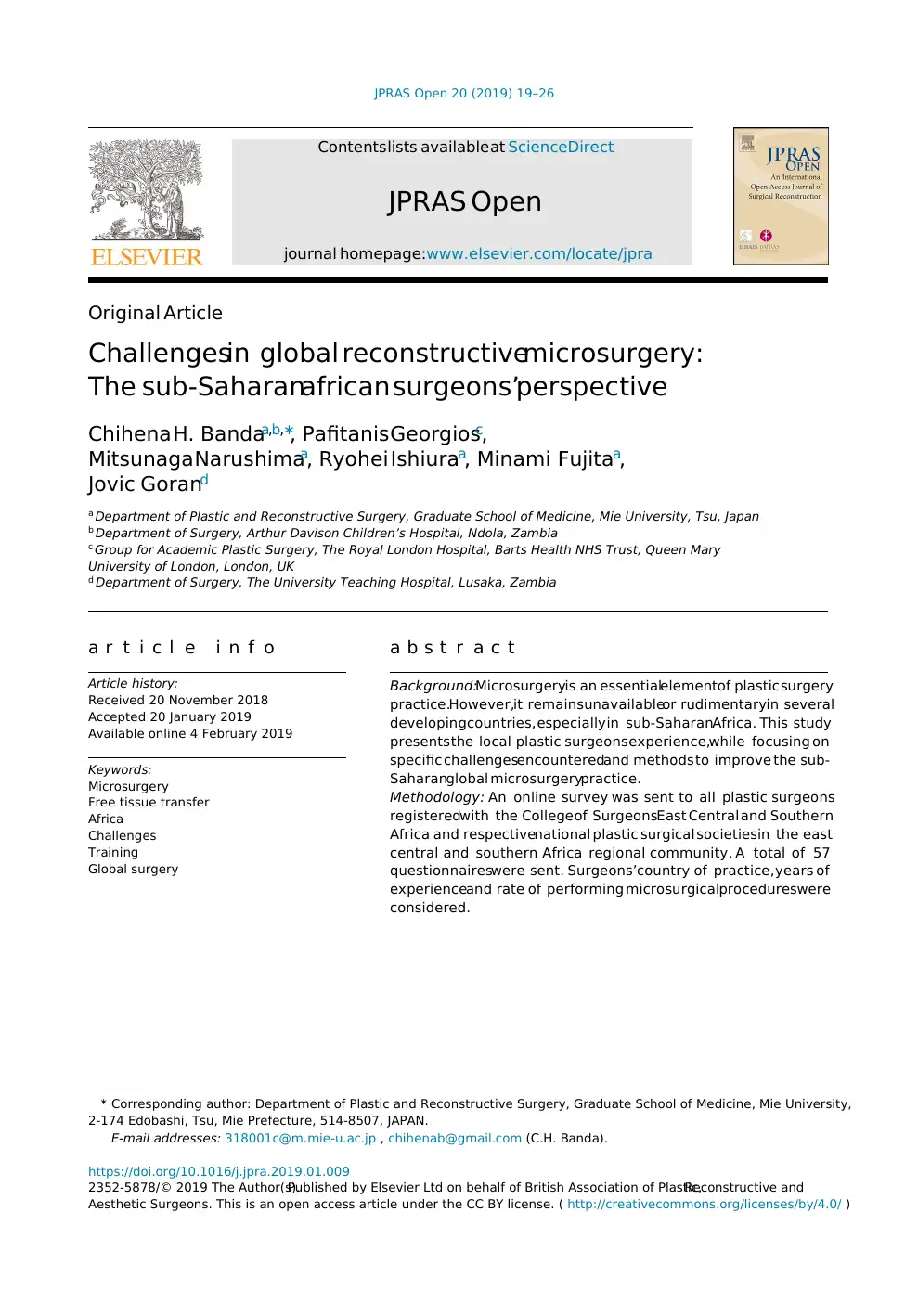

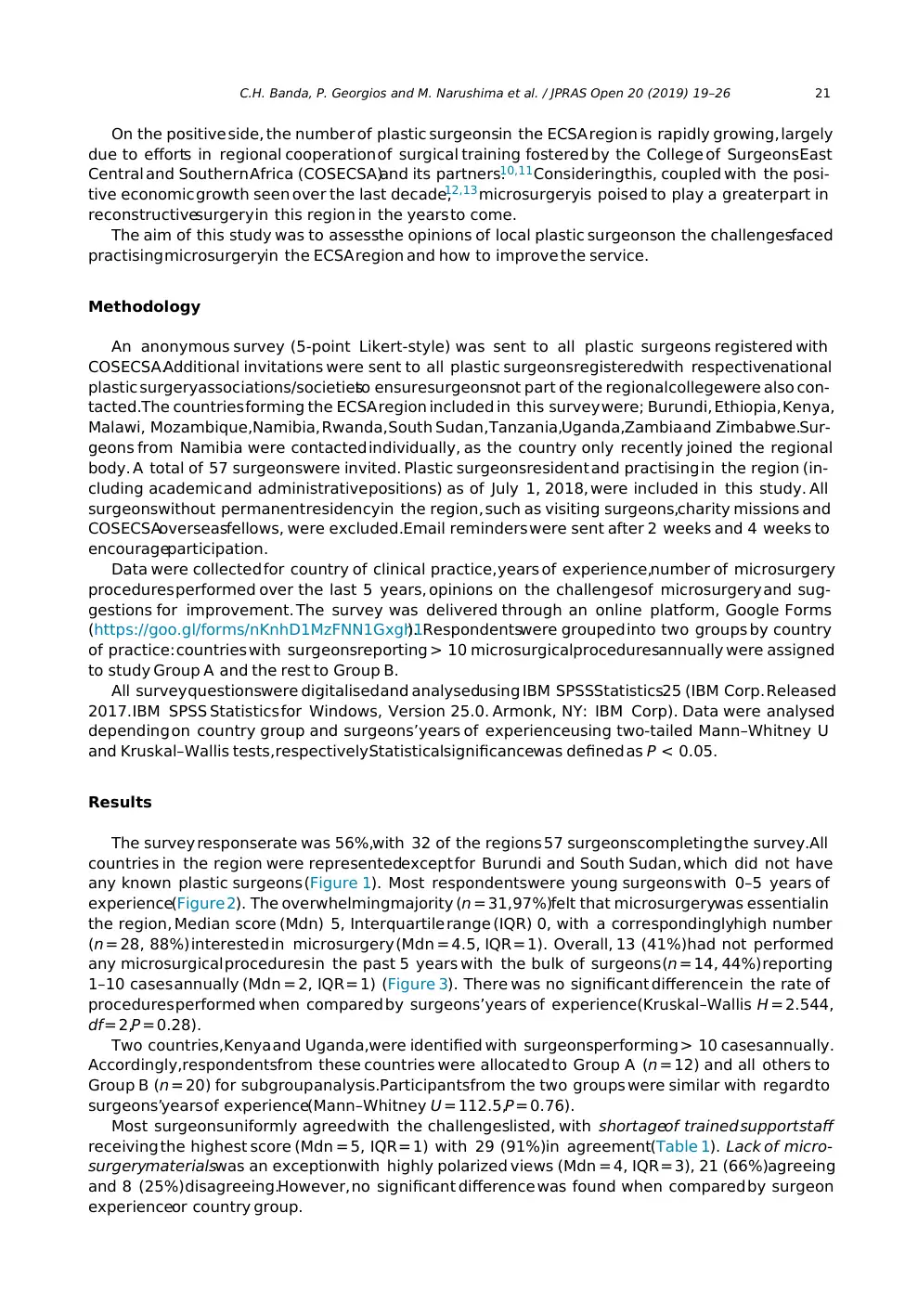

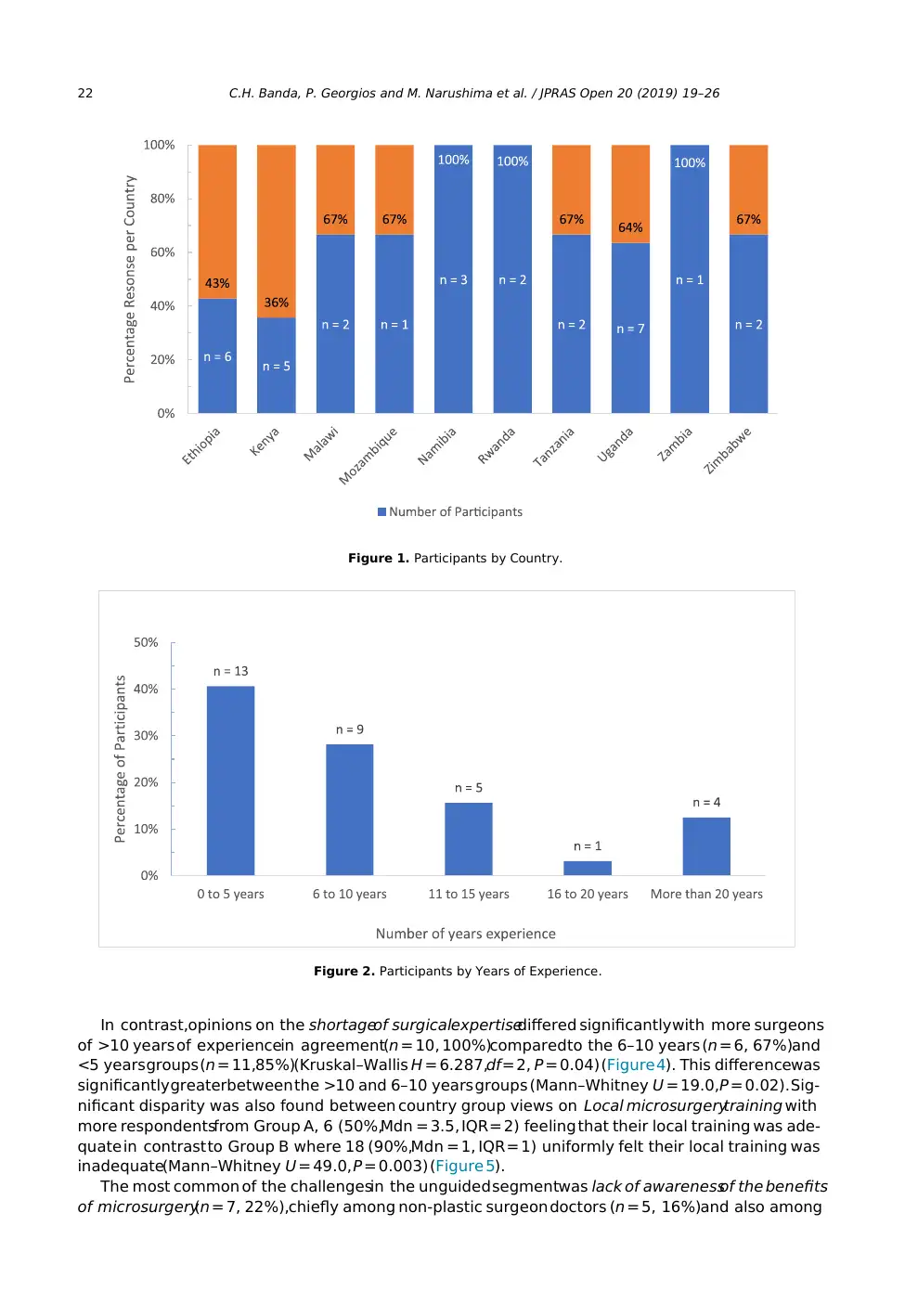

The survey responserate was 56%,with 32 of the regions 57 surgeonscompleting the survey.All

countries in the region were representedexcept for Burundi and South Sudan, which did not have

any known plastic surgeons (Figure 1). Most respondentswere young surgeons with 0–5 years of

experience(Figure 2). The overwhelmingmajority (n = 31,97%)felt that microsurgerywas essentialin

the region, Median score (Mdn) 5, Interquartile range (IQR) 0, with a correspondinglyhigh number

(n = 28, 88%) interested in microsurgery (Mdn = 4.5, IQR = 1). Overall, 13 (41%)had not performed

any microsurgical proceduresin the past 5 years with the bulk of surgeons (n = 14, 44%) reporting

1–10 cases annually (Mdn = 2, IQR = 1) (Figure 3). There was no significant difference in the rate of

procedures performed when compared by surgeons’years of experience(Kruskal–Wallis H = 2.544,

df = 2,P = 0.28).

Two countries,Kenya and Uganda,were identified with surgeonsperforming > 10 casesannually.

Accordingly,respondentsfrom these countries were allocated to Group A (n = 12) and all others to

Group B (n = 20) for subgroup analysis.Participantsfrom the two groups were similar with regard to

surgeons’years of experience(Mann–Whitney U = 112.5,P = 0.76).

Most surgeonsuniformly agreed with the challengeslisted, with shortageof trained support staff

receiving the highest score (Mdn = 5, IQR = 1) with 29 (91%)in agreement(Table 1). Lack of micro-

surgerymaterialswas an exceptionwith highly polarized views (Mdn = 4, IQR = 3), 21 (66%)agreeing

and 8 (25%)disagreeing.However, no significant difference was found when compared by surgeon

experienceor country group.

On the positive side, the number of plastic surgeonsin the ECSA region is rapidly growing, largely

due to efforts in regional cooperation of surgical training fostered by the College of SurgeonsEast

Central and Southern Africa (COSECSA)and its partners.10,11 Consideringthis, coupled with the posi-

tive economic growth seen over the last decade,12,13 microsurgeryis poised to play a greater part in

reconstructivesurgery in this region in the years to come.

The aim of this study was to assessthe opinions of local plastic surgeonson the challengesfaced

practising microsurgeryin the ECSA region and how to improve the service.

Methodology

An anonymous survey (5-point Likert-style) was sent to all plastic surgeons registered with

COSECSA.Additional invitations were sent to all plastic surgeonsregisteredwith respectivenational

plastic surgeryassociations/societiesto ensuresurgeonsnot part of the regional collegewere also con-

tacted.The countries forming the ECSA region included in this survey were; Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya,

Malawi, Mozambique,Namibia, Rwanda,South Sudan,Tanzania,Uganda,Zambia and Zimbabwe.Sur-

geons from Namibia were contacted individually, as the country only recently joined the regional

body. A total of 57 surgeonswere invited. Plastic surgeonsresident and practising in the region (in-

cluding academic and administrativepositions) as of July 1, 2018, were included in this study. All

surgeonswithout permanentresidencyin the region, such as visiting surgeons,charity missions and

COSECSAoverseasfellows, were excluded.Email reminders were sent after 2 weeks and 4 weeks to

encourageparticipation.

Data were collected for country of clinical practice,years of experience,number of microsurgery

procedures performed over the last 5 years, opinions on the challengesof microsurgery and sug-

gestions for improvement. The survey was delivered through an online platform, Google Forms

(https://goo.gl/forms/nKnhD1MzFNN1Gxgh1). Respondentswere grouped into two groups by country

of practice: countries with surgeonsreporting > 10 microsurgicalproceduresannually were assigned

to study Group A and the rest to Group B.

All survey questionswere digitalisedand analysedusing IBM SPSSStatistics25 (IBM Corp. Released

2017.IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Data were analysed

depending on country group and surgeons’years of experienceusing two-tailed Mann–Whitney U

and Kruskal–Wallis tests,respectively.Statisticalsignificancewas defined as P < 0.05.

Results

The survey responserate was 56%,with 32 of the regions 57 surgeonscompleting the survey.All

countries in the region were representedexcept for Burundi and South Sudan, which did not have

any known plastic surgeons (Figure 1). Most respondentswere young surgeons with 0–5 years of

experience(Figure 2). The overwhelmingmajority (n = 31,97%)felt that microsurgerywas essentialin

the region, Median score (Mdn) 5, Interquartile range (IQR) 0, with a correspondinglyhigh number

(n = 28, 88%) interested in microsurgery (Mdn = 4.5, IQR = 1). Overall, 13 (41%)had not performed

any microsurgical proceduresin the past 5 years with the bulk of surgeons (n = 14, 44%) reporting

1–10 cases annually (Mdn = 2, IQR = 1) (Figure 3). There was no significant difference in the rate of

procedures performed when compared by surgeons’years of experience(Kruskal–Wallis H = 2.544,

df = 2,P = 0.28).

Two countries,Kenya and Uganda,were identified with surgeonsperforming > 10 casesannually.

Accordingly,respondentsfrom these countries were allocated to Group A (n = 12) and all others to

Group B (n = 20) for subgroup analysis.Participantsfrom the two groups were similar with regard to

surgeons’years of experience(Mann–Whitney U = 112.5,P = 0.76).

Most surgeonsuniformly agreed with the challengeslisted, with shortageof trained support staff

receiving the highest score (Mdn = 5, IQR = 1) with 29 (91%)in agreement(Table 1). Lack of micro-

surgerymaterialswas an exceptionwith highly polarized views (Mdn = 4, IQR = 3), 21 (66%)agreeing

and 8 (25%)disagreeing.However, no significant difference was found when compared by surgeon

experienceor country group.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

22 C.H. Banda, P. Georgios and M. Narushima et al. / JPRAS Open 20 (2019) 19–26

Figure 1. Participants by Country.

Figure 2. Participants by Years of Experience.

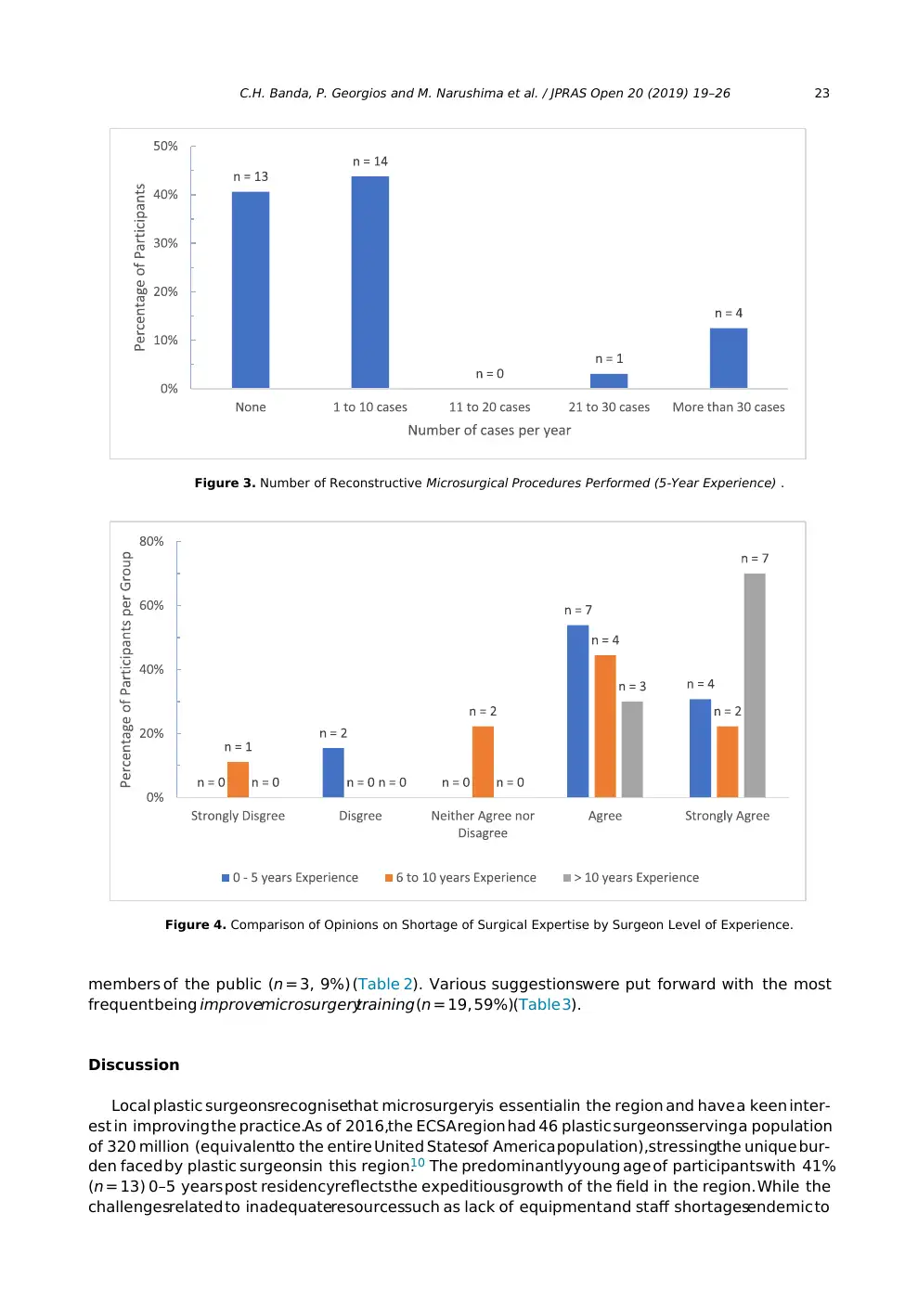

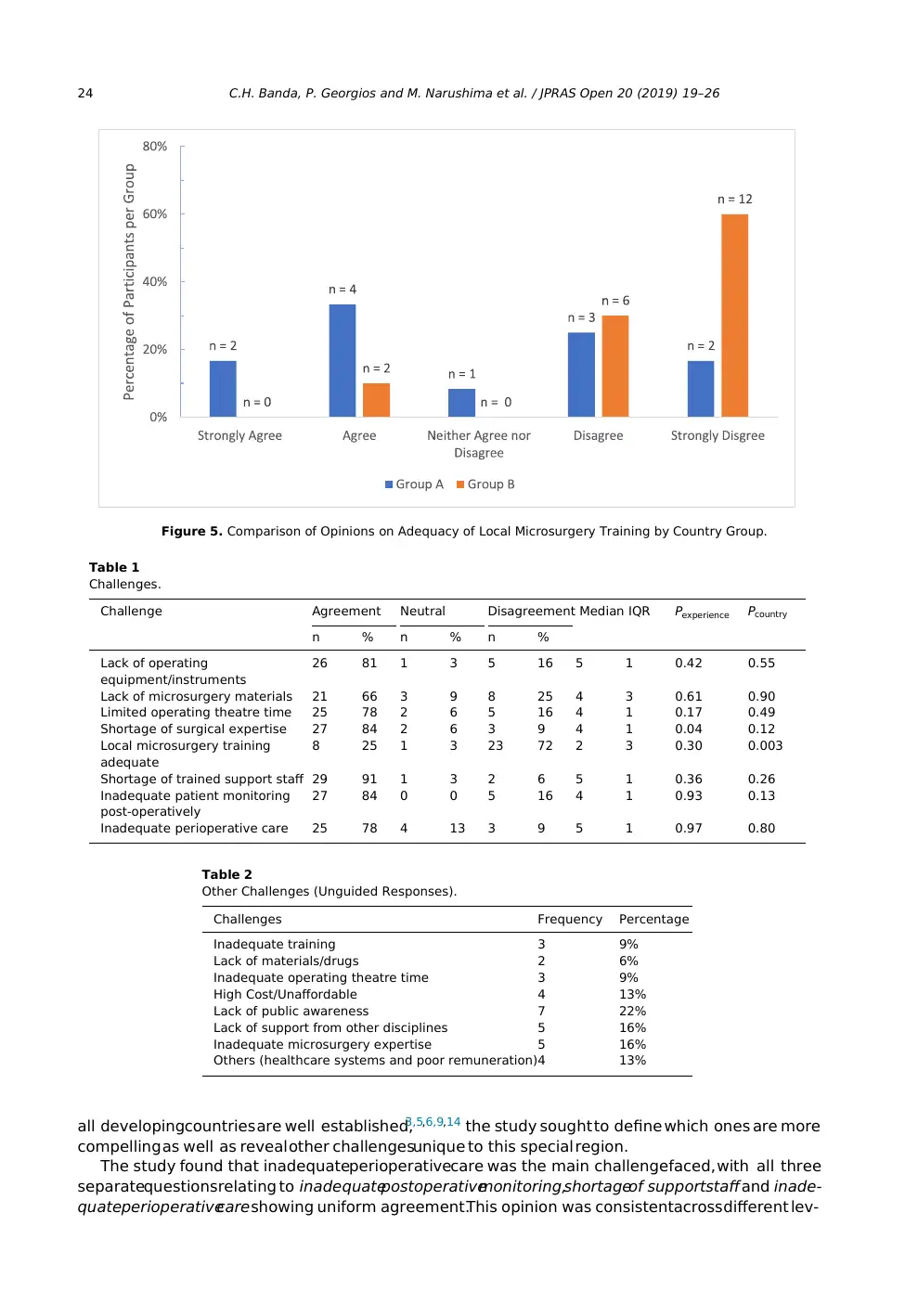

In contrast,opinions on the shortageof surgicalexpertisediffered significantly with more surgeons

of >10 years of experiencein agreement(n = 10, 100%)comparedto the 6–10 years (n = 6, 67%)and

<5 years groups (n = 11,85%)(Kruskal–Wallis H = 6.287,df = 2, P = 0.04) (Figure 4). This differencewas

significantly greaterbetween the >10 and 6–10 years groups (Mann–Whitney U = 19.0,P = 0.02). Sig-

nificant disparity was also found between country group views on Local microsurgerytraining with

more respondentsfrom Group A, 6 (50%,Mdn = 3.5, IQR = 2) feeling that their local training was ade-

quate in contrast to Group B where 18 (90%,Mdn = 1, IQR = 1) uniformly felt their local training was

inadequate(Mann–Whitney U = 49.0, P = 0.003) (Figure 5).

The most common of the challengesin the unguided segmentwas lack of awarenessof the benefits

of microsurgery(n = 7, 22%),chiefly among non-plastic surgeon doctors (n = 5, 16%)and also among

Figure 1. Participants by Country.

Figure 2. Participants by Years of Experience.

In contrast,opinions on the shortageof surgicalexpertisediffered significantly with more surgeons

of >10 years of experiencein agreement(n = 10, 100%)comparedto the 6–10 years (n = 6, 67%)and

<5 years groups (n = 11,85%)(Kruskal–Wallis H = 6.287,df = 2, P = 0.04) (Figure 4). This differencewas

significantly greaterbetween the >10 and 6–10 years groups (Mann–Whitney U = 19.0,P = 0.02). Sig-

nificant disparity was also found between country group views on Local microsurgerytraining with

more respondentsfrom Group A, 6 (50%,Mdn = 3.5, IQR = 2) feeling that their local training was ade-

quate in contrast to Group B where 18 (90%,Mdn = 1, IQR = 1) uniformly felt their local training was

inadequate(Mann–Whitney U = 49.0, P = 0.003) (Figure 5).

The most common of the challengesin the unguided segmentwas lack of awarenessof the benefits

of microsurgery(n = 7, 22%),chiefly among non-plastic surgeon doctors (n = 5, 16%)and also among

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

C.H. Banda, P. Georgios and M. Narushima et al. / JPRAS Open 20 (2019) 19–26 23

Figure 3. Number of Reconstructive Microsurgical Procedures Performed (5-Year Experience) .

Figure 4. Comparison of Opinions on Shortage of Surgical Expertise by Surgeon Level of Experience.

members of the public (n = 3, 9%) (Table 2). Various suggestionswere put forward with the most

frequent being improvemicrosurgerytraining (n = 19, 59%)(Table 3).

Discussion

Local plastic surgeonsrecognisethat microsurgeryis essentialin the region and have a keen inter-

est in improving the practice.As of 2016,the ECSA region had 46 plastic surgeonsserving a population

of 320 million (equivalentto the entire United Statesof America population),stressingthe unique bur-

den faced by plastic surgeonsin this region.10 The predominantlyyoung age of participantswith 41%

(n = 13) 0–5 years post residencyreflects the expeditiousgrowth of the field in the region. While the

challengesrelated to inadequateresourcessuch as lack of equipment and staff shortagesendemic to

Figure 3. Number of Reconstructive Microsurgical Procedures Performed (5-Year Experience) .

Figure 4. Comparison of Opinions on Shortage of Surgical Expertise by Surgeon Level of Experience.

members of the public (n = 3, 9%) (Table 2). Various suggestionswere put forward with the most

frequent being improvemicrosurgerytraining (n = 19, 59%)(Table 3).

Discussion

Local plastic surgeonsrecognisethat microsurgeryis essentialin the region and have a keen inter-

est in improving the practice.As of 2016,the ECSA region had 46 plastic surgeonsserving a population

of 320 million (equivalentto the entire United Statesof America population),stressingthe unique bur-

den faced by plastic surgeonsin this region.10 The predominantlyyoung age of participantswith 41%

(n = 13) 0–5 years post residencyreflects the expeditiousgrowth of the field in the region. While the

challengesrelated to inadequateresourcessuch as lack of equipment and staff shortagesendemic to

24 C.H. Banda, P. Georgios and M. Narushima et al. / JPRAS Open 20 (2019) 19–26

Figure 5. Comparison of Opinions on Adequacy of Local Microsurgery Training by Country Group.

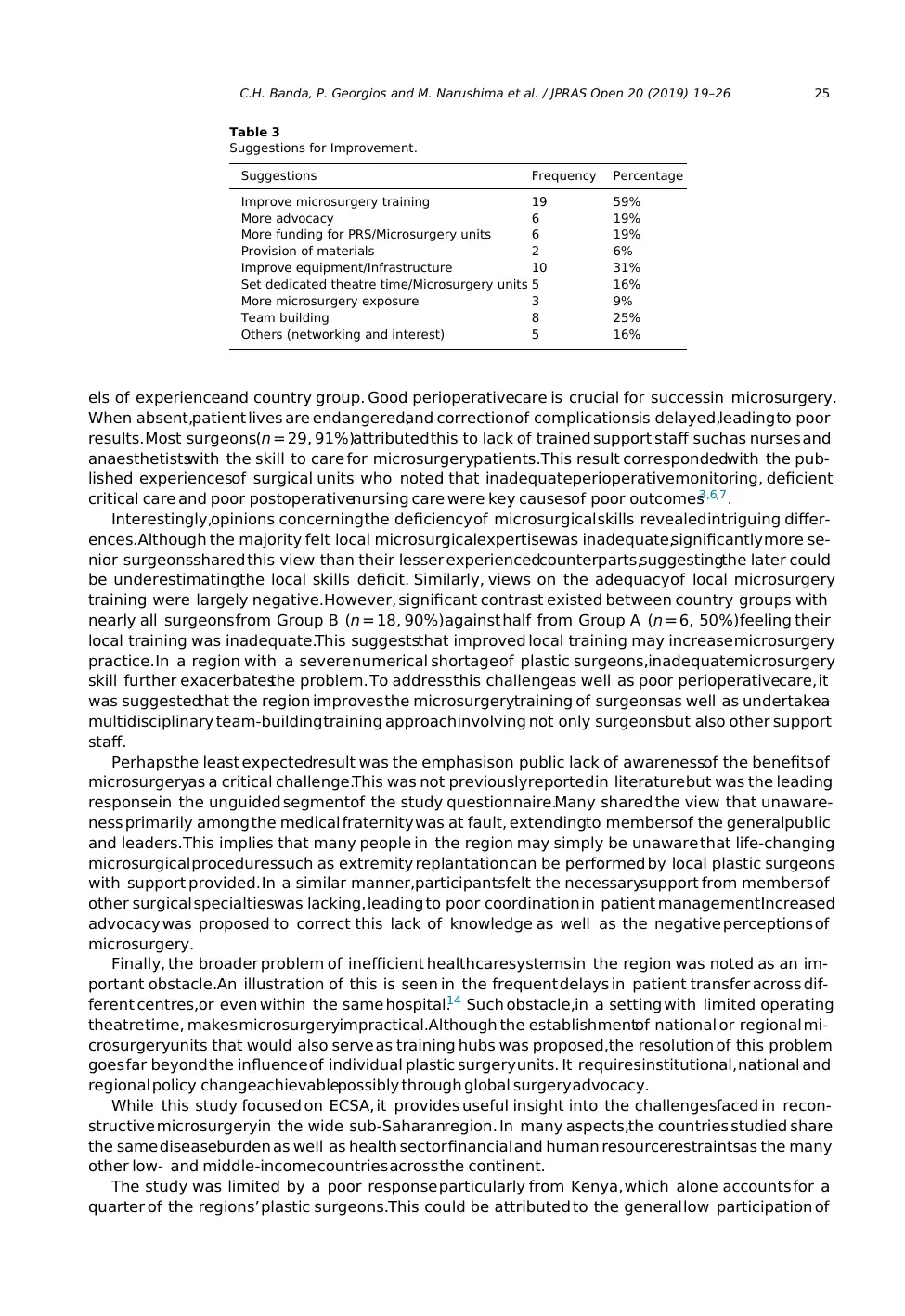

Table 1

Challenges.

Challenge Agreement Neutral Disagreement Median IQR Pexperience Pcountry

n % n % n %

Lack of operating

equipment/instruments

26 81 1 3 5 16 5 1 0.42 0.55

Lack of microsurgery materials 21 66 3 9 8 25 4 3 0.61 0.90

Limited operating theatre time 25 78 2 6 5 16 4 1 0.17 0.49

Shortage of surgical expertise 27 84 2 6 3 9 4 1 0.04 0.12

Local microsurgery training

adequate

8 25 1 3 23 72 2 3 0.30 0.003

Shortage of trained support staff 29 91 1 3 2 6 5 1 0.36 0.26

Inadequate patient monitoring

post-operatively

27 84 0 0 5 16 4 1 0.93 0.13

Inadequate perioperative care 25 78 4 13 3 9 5 1 0.97 0.80

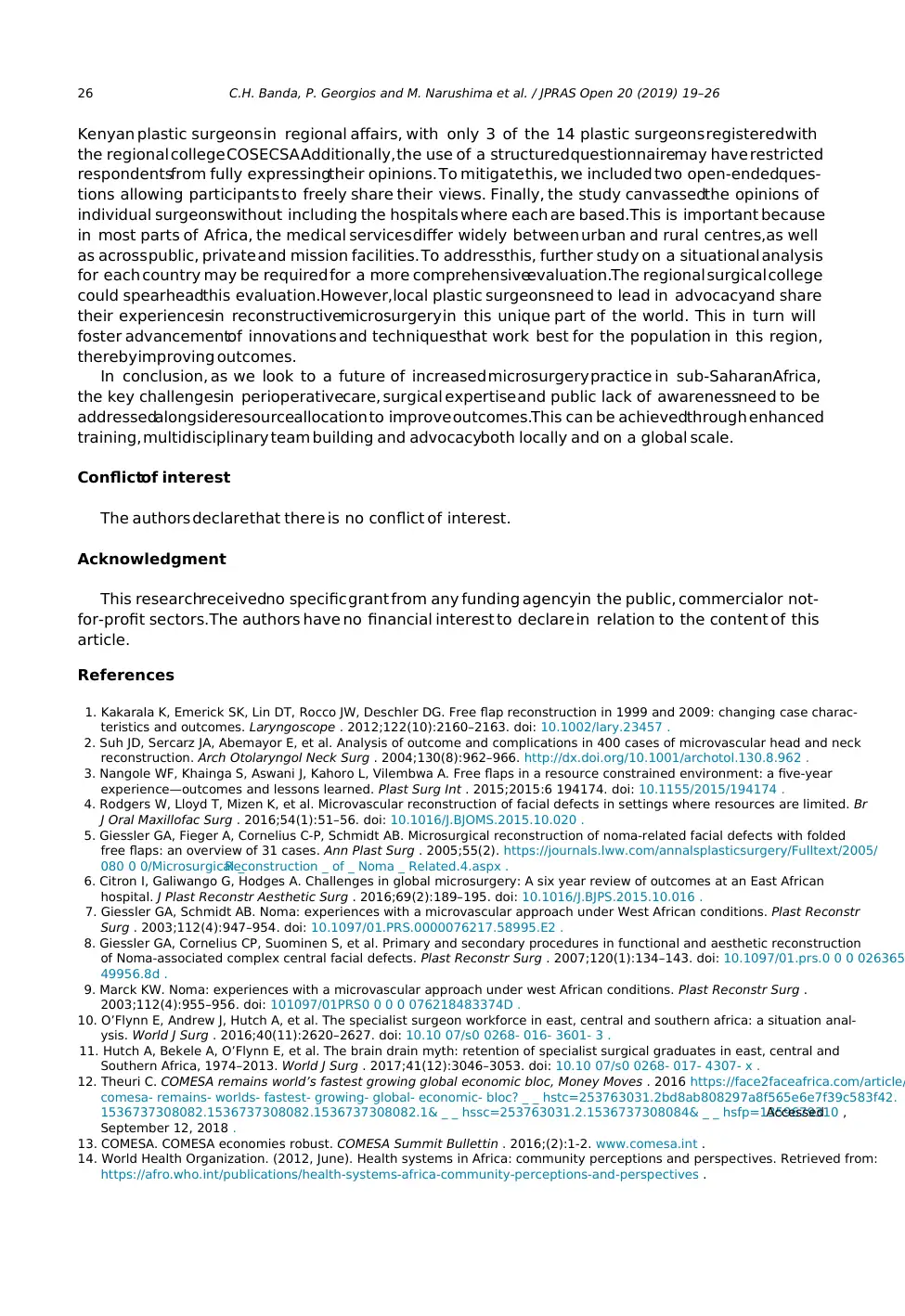

Table 2

Other Challenges (Unguided Responses).

Challenges Frequency Percentage

Inadequate training 3 9%

Lack of materials/drugs 2 6%

Inadequate operating theatre time 3 9%

High Cost/Unaffordable 4 13%

Lack of public awareness 7 22%

Lack of support from other disciplines 5 16%

Inadequate microsurgery expertise 5 16%

Others (healthcare systems and poor remuneration)4 13%

all developingcountries are well established,3,5,6,9,14 the study sought to define which ones are more

compelling as well as reveal other challengesunique to this special region.

The study found that inadequateperioperativecare was the main challengefaced, with all three

separatequestionsrelating to inadequatepostoperativemonitoring,shortageof supportstaffand inade-

quateperioperativecare showing uniform agreement.This opinion was consistentacross different lev-

Figure 5. Comparison of Opinions on Adequacy of Local Microsurgery Training by Country Group.

Table 1

Challenges.

Challenge Agreement Neutral Disagreement Median IQR Pexperience Pcountry

n % n % n %

Lack of operating

equipment/instruments

26 81 1 3 5 16 5 1 0.42 0.55

Lack of microsurgery materials 21 66 3 9 8 25 4 3 0.61 0.90

Limited operating theatre time 25 78 2 6 5 16 4 1 0.17 0.49

Shortage of surgical expertise 27 84 2 6 3 9 4 1 0.04 0.12

Local microsurgery training

adequate

8 25 1 3 23 72 2 3 0.30 0.003

Shortage of trained support staff 29 91 1 3 2 6 5 1 0.36 0.26

Inadequate patient monitoring

post-operatively

27 84 0 0 5 16 4 1 0.93 0.13

Inadequate perioperative care 25 78 4 13 3 9 5 1 0.97 0.80

Table 2

Other Challenges (Unguided Responses).

Challenges Frequency Percentage

Inadequate training 3 9%

Lack of materials/drugs 2 6%

Inadequate operating theatre time 3 9%

High Cost/Unaffordable 4 13%

Lack of public awareness 7 22%

Lack of support from other disciplines 5 16%

Inadequate microsurgery expertise 5 16%

Others (healthcare systems and poor remuneration)4 13%

all developingcountries are well established,3,5,6,9,14 the study sought to define which ones are more

compelling as well as reveal other challengesunique to this special region.

The study found that inadequateperioperativecare was the main challengefaced, with all three

separatequestionsrelating to inadequatepostoperativemonitoring,shortageof supportstaffand inade-

quateperioperativecare showing uniform agreement.This opinion was consistentacross different lev-

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

C.H. Banda, P. Georgios and M. Narushima et al. / JPRAS Open 20 (2019) 19–26 25

Table 3

Suggestions for Improvement.

Suggestions Frequency Percentage

Improve microsurgery training 19 59%

More advocacy 6 19%

More funding for PRS/Microsurgery units 6 19%

Provision of materials 2 6%

Improve equipment/Infrastructure 10 31%

Set dedicated theatre time/Microsurgery units 5 16%

More microsurgery exposure 3 9%

Team building 8 25%

Others (networking and interest) 5 16%

els of experienceand country group. Good perioperativecare is crucial for successin microsurgery.

When absent,patient lives are endangered,and correction of complicationsis delayed,leading to poor

results. Most surgeons(n = 29, 91%)attributed this to lack of trained support staff such as nurses and

anaesthetistswith the skill to care for microsurgerypatients.This result correspondedwith the pub-

lished experiencesof surgical units who noted that inadequateperioperativemonitoring, deficient

critical care and poor postoperativenursing care were key causesof poor outcomes3,6,7.

Interestingly,opinions concerning the deficiency of microsurgical skills revealedintriguing differ-

ences.Although the majority felt local microsurgicalexpertisewas inadequate,significantly more se-

nior surgeonsshared this view than their lesser experiencedcounterparts,suggestingthe later could

be underestimatingthe local skills deficit. Similarly, views on the adequacyof local microsurgery

training were largely negative.However, significant contrast existed between country groups with

nearly all surgeons from Group B (n = 18, 90%)against half from Group A (n = 6, 50%)feeling their

local training was inadequate.This suggeststhat improved local training may increase microsurgery

practice. In a region with a severe numerical shortage of plastic surgeons,inadequatemicrosurgery

skill further exacerbatesthe problem. To addressthis challengeas well as poor perioperativecare, it

was suggestedthat the region improves the microsurgerytraining of surgeonsas well as undertakea

multidisciplinary team-building training approachinvolving not only surgeonsbut also other support

staff.

Perhaps the least expectedresult was the emphasison public lack of awarenessof the benefits of

microsurgeryas a critical challenge.This was not previouslyreported in literature but was the leading

responsein the unguided segmentof the study questionnaire.Many shared the view that unaware-

ness primarily among the medical fraternity was at fault, extendingto membersof the generalpublic

and leaders.This implies that many people in the region may simply be unaware that life-changing

microsurgical proceduressuch as extremity replantation can be performed by local plastic surgeons

with support provided. In a similar manner,participantsfelt the necessarysupport from members of

other surgical specialtieswas lacking, leading to poor coordination in patient management.Increased

advocacy was proposed to correct this lack of knowledge as well as the negative perceptions of

microsurgery.

Finally, the broader problem of inefficient healthcaresystemsin the region was noted as an im-

portant obstacle.An illustration of this is seen in the frequent delays in patient transfer across dif-

ferent centres,or even within the same hospital.14 Such obstacle,in a setting with limited operating

theatre time, makes microsurgeryimpractical.Although the establishmentof national or regional mi-

crosurgeryunits that would also serve as training hubs was proposed,the resolution of this problem

goes far beyond the influence of individual plastic surgery units. It requires institutional, national and

regional policy changeachievablepossibly through global surgery advocacy.

While this study focused on ECSA, it provides useful insight into the challengesfaced in recon-

structive microsurgeryin the wide sub-Saharanregion. In many aspects,the countries studied share

the same diseaseburden as well as health sector financial and human resourcerestraintsas the many

other low- and middle-income countries across the continent.

The study was limited by a poor response particularly from Kenya, which alone accounts for a

quarter of the regions’ plastic surgeons.This could be attributed to the general low participation of

Table 3

Suggestions for Improvement.

Suggestions Frequency Percentage

Improve microsurgery training 19 59%

More advocacy 6 19%

More funding for PRS/Microsurgery units 6 19%

Provision of materials 2 6%

Improve equipment/Infrastructure 10 31%

Set dedicated theatre time/Microsurgery units 5 16%

More microsurgery exposure 3 9%

Team building 8 25%

Others (networking and interest) 5 16%

els of experienceand country group. Good perioperativecare is crucial for successin microsurgery.

When absent,patient lives are endangered,and correction of complicationsis delayed,leading to poor

results. Most surgeons(n = 29, 91%)attributed this to lack of trained support staff such as nurses and

anaesthetistswith the skill to care for microsurgerypatients.This result correspondedwith the pub-

lished experiencesof surgical units who noted that inadequateperioperativemonitoring, deficient

critical care and poor postoperativenursing care were key causesof poor outcomes3,6,7.

Interestingly,opinions concerning the deficiency of microsurgical skills revealedintriguing differ-

ences.Although the majority felt local microsurgicalexpertisewas inadequate,significantly more se-

nior surgeonsshared this view than their lesser experiencedcounterparts,suggestingthe later could

be underestimatingthe local skills deficit. Similarly, views on the adequacyof local microsurgery

training were largely negative.However, significant contrast existed between country groups with

nearly all surgeons from Group B (n = 18, 90%)against half from Group A (n = 6, 50%)feeling their

local training was inadequate.This suggeststhat improved local training may increase microsurgery

practice. In a region with a severe numerical shortage of plastic surgeons,inadequatemicrosurgery

skill further exacerbatesthe problem. To addressthis challengeas well as poor perioperativecare, it

was suggestedthat the region improves the microsurgerytraining of surgeonsas well as undertakea

multidisciplinary team-building training approachinvolving not only surgeonsbut also other support

staff.

Perhaps the least expectedresult was the emphasison public lack of awarenessof the benefits of

microsurgeryas a critical challenge.This was not previouslyreported in literature but was the leading

responsein the unguided segmentof the study questionnaire.Many shared the view that unaware-

ness primarily among the medical fraternity was at fault, extendingto membersof the generalpublic

and leaders.This implies that many people in the region may simply be unaware that life-changing

microsurgical proceduressuch as extremity replantation can be performed by local plastic surgeons

with support provided. In a similar manner,participantsfelt the necessarysupport from members of

other surgical specialtieswas lacking, leading to poor coordination in patient management.Increased

advocacy was proposed to correct this lack of knowledge as well as the negative perceptions of

microsurgery.

Finally, the broader problem of inefficient healthcaresystemsin the region was noted as an im-

portant obstacle.An illustration of this is seen in the frequent delays in patient transfer across dif-

ferent centres,or even within the same hospital.14 Such obstacle,in a setting with limited operating

theatre time, makes microsurgeryimpractical.Although the establishmentof national or regional mi-

crosurgeryunits that would also serve as training hubs was proposed,the resolution of this problem

goes far beyond the influence of individual plastic surgery units. It requires institutional, national and

regional policy changeachievablepossibly through global surgery advocacy.

While this study focused on ECSA, it provides useful insight into the challengesfaced in recon-

structive microsurgeryin the wide sub-Saharanregion. In many aspects,the countries studied share

the same diseaseburden as well as health sector financial and human resourcerestraintsas the many

other low- and middle-income countries across the continent.

The study was limited by a poor response particularly from Kenya, which alone accounts for a

quarter of the regions’ plastic surgeons.This could be attributed to the general low participation of

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

26 C.H. Banda, P. Georgios and M. Narushima et al. / JPRAS Open 20 (2019) 19–26

Kenyan plastic surgeons in regional affairs, with only 3 of the 14 plastic surgeons registered with

the regional college COSECSA.Additionally, the use of a structured questionnairemay have restricted

respondentsfrom fully expressingtheir opinions. To mitigate this, we included two open-endedques-

tions allowing participants to freely share their views. Finally, the study canvassedthe opinions of

individual surgeonswithout including the hospitals where each are based.This is important because

in most parts of Africa, the medical services differ widely between urban and rural centres,as well

as across public, private and mission facilities. To addressthis, further study on a situational analysis

for each country may be required for a more comprehensiveevaluation.The regional surgical college

could spearheadthis evaluation.However,local plastic surgeonsneed to lead in advocacyand share

their experiencesin reconstructivemicrosurgery in this unique part of the world. This in turn will

foster advancementof innovations and techniquesthat work best for the population in this region,

therebyimproving outcomes.

In conclusion, as we look to a future of increased microsurgery practice in sub-SaharanAfrica,

the key challengesin perioperativecare, surgical expertise and public lack of awarenessneed to be

addressedalongsideresourceallocation to improve outcomes.This can be achievedthrough enhanced

training, multidisciplinary team building and advocacyboth locally and on a global scale.

Conflictof interest

The authors declarethat there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

This researchreceivedno specific grant from any funding agencyin the public, commercialor not-

for-profit sectors.The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this

article.

References

1. Kakarala K, Emerick SK, Lin DT, Rocco JW, Deschler DG. Free flap reconstruction in 1999 and 2009: changing case charac-

teristics and outcomes. Laryngoscope . 2012;122(10):2160–2163. doi: 10.1002/lary.23457 .

2. Suh JD, Sercarz JA, Abemayor E, et al. Analysis of outcome and complications in 400 cases of microvascular head and neck

reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Neck Surg . 2004;130(8):962–966. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archotol.130.8.962 .

3. Nangole WF, Khainga S, Aswani J, Kahoro L, Vilembwa A. Free flaps in a resource constrained environment: a five-year

experience—outcomes and lessons learned. Plast Surg Int . 2015;2015:6 194174. doi: 10.1155/2015/194174 .

4. Rodgers W, Lloyd T, Mizen K, et al. Microvascular reconstruction of facial defects in settings where resources are limited. Br

J Oral Maxillofac Surg . 2016;54(1):51–56. doi: 10.1016/J.BJOMS.2015.10.020 .

5. Giessler GA, Fieger A, Cornelius C-P, Schmidt AB. Microsurgical reconstruction of noma-related facial defects with folded

free flaps: an overview of 31 cases. Ann Plast Surg . 2005;55(2). https://journals.lww.com/annalsplasticsurgery/Fulltext/2005/

080 0 0/Microsurgical _Reconstruction _ of _ Noma _ Related.4.aspx .

6. Citron I, Galiwango G, Hodges A. Challenges in global microsurgery: A six year review of outcomes at an East African

hospital. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg . 2016;69(2):189–195. doi: 10.1016/J.BJPS.2015.10.016 .

7. Giessler GA, Schmidt AB. Noma: experiences with a microvascular approach under West African conditions. Plast Reconstr

Surg . 2003;112(4):947–954. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000076217.58995.E2 .

8. Giessler GA, Cornelius CP, Suominen S, et al. Primary and secondary procedures in functional and aesthetic reconstruction

of Noma-associated complex central facial defects. Plast Reconstr Surg . 2007;120(1):134–143. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0 0 0 026365

49956.8d .

9. Marck KW. Noma: experiences with a microvascular approach under west African conditions. Plast Reconstr Surg .

2003;112(4):955–956. doi: 101097/01PRS0 0 0 0 076218483374D .

10. O’Flynn E, Andrew J, Hutch A, et al. The specialist surgeon workforce in east, central and southern africa: a situation anal-

ysis. World J Surg . 2016;40(11):2620–2627. doi: 10.10 07/s0 0268- 016- 3601- 3 .

11. Hutch A, Bekele A, O’Flynn E, et al. The brain drain myth: retention of specialist surgical graduates in east, central and

Southern Africa, 1974–2013. World J Surg . 2017;41(12):3046–3053. doi: 10.10 07/s0 0268- 017- 4307- x .

12. Theuri C. COMESA remains world’s fastest growing global economic bloc, Money Moves . 2016 https://face2faceafrica.com/article/

comesa- remains- worlds- fastest- growing- global- economic- bloc? _ _ hstc=253763031.2bd8ab808297a8f565e6e7f39c583f42.

1536737308082.1536737308082.1536737308082.1& _ _ hssc=253763031.2.1536737308084& _ _ hsfp=1359679310 ,Accessed

September 12, 2018 .

13. COMESA. COMESA economies robust. COMESA Summit Bullettin . 2016;(2):1-2. www.comesa.int .

14. World Health Organization. (2012, June). Health systems in Africa: community perceptions and perspectives. Retrieved from:

https://afro.who.int/publications/health-systems-africa-community-perceptions-and-perspectives .

Kenyan plastic surgeons in regional affairs, with only 3 of the 14 plastic surgeons registered with

the regional college COSECSA.Additionally, the use of a structured questionnairemay have restricted

respondentsfrom fully expressingtheir opinions. To mitigate this, we included two open-endedques-

tions allowing participants to freely share their views. Finally, the study canvassedthe opinions of

individual surgeonswithout including the hospitals where each are based.This is important because

in most parts of Africa, the medical services differ widely between urban and rural centres,as well

as across public, private and mission facilities. To addressthis, further study on a situational analysis

for each country may be required for a more comprehensiveevaluation.The regional surgical college

could spearheadthis evaluation.However,local plastic surgeonsneed to lead in advocacyand share

their experiencesin reconstructivemicrosurgery in this unique part of the world. This in turn will

foster advancementof innovations and techniquesthat work best for the population in this region,

therebyimproving outcomes.

In conclusion, as we look to a future of increased microsurgery practice in sub-SaharanAfrica,

the key challengesin perioperativecare, surgical expertise and public lack of awarenessneed to be

addressedalongsideresourceallocation to improve outcomes.This can be achievedthrough enhanced

training, multidisciplinary team building and advocacyboth locally and on a global scale.

Conflictof interest

The authors declarethat there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

This researchreceivedno specific grant from any funding agencyin the public, commercialor not-

for-profit sectors.The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this

article.

References

1. Kakarala K, Emerick SK, Lin DT, Rocco JW, Deschler DG. Free flap reconstruction in 1999 and 2009: changing case charac-

teristics and outcomes. Laryngoscope . 2012;122(10):2160–2163. doi: 10.1002/lary.23457 .

2. Suh JD, Sercarz JA, Abemayor E, et al. Analysis of outcome and complications in 400 cases of microvascular head and neck

reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Neck Surg . 2004;130(8):962–966. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archotol.130.8.962 .

3. Nangole WF, Khainga S, Aswani J, Kahoro L, Vilembwa A. Free flaps in a resource constrained environment: a five-year

experience—outcomes and lessons learned. Plast Surg Int . 2015;2015:6 194174. doi: 10.1155/2015/194174 .

4. Rodgers W, Lloyd T, Mizen K, et al. Microvascular reconstruction of facial defects in settings where resources are limited. Br

J Oral Maxillofac Surg . 2016;54(1):51–56. doi: 10.1016/J.BJOMS.2015.10.020 .

5. Giessler GA, Fieger A, Cornelius C-P, Schmidt AB. Microsurgical reconstruction of noma-related facial defects with folded

free flaps: an overview of 31 cases. Ann Plast Surg . 2005;55(2). https://journals.lww.com/annalsplasticsurgery/Fulltext/2005/

080 0 0/Microsurgical _Reconstruction _ of _ Noma _ Related.4.aspx .

6. Citron I, Galiwango G, Hodges A. Challenges in global microsurgery: A six year review of outcomes at an East African

hospital. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg . 2016;69(2):189–195. doi: 10.1016/J.BJPS.2015.10.016 .

7. Giessler GA, Schmidt AB. Noma: experiences with a microvascular approach under West African conditions. Plast Reconstr

Surg . 2003;112(4):947–954. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000076217.58995.E2 .

8. Giessler GA, Cornelius CP, Suominen S, et al. Primary and secondary procedures in functional and aesthetic reconstruction

of Noma-associated complex central facial defects. Plast Reconstr Surg . 2007;120(1):134–143. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0 0 0 026365

49956.8d .

9. Marck KW. Noma: experiences with a microvascular approach under west African conditions. Plast Reconstr Surg .

2003;112(4):955–956. doi: 101097/01PRS0 0 0 0 076218483374D .

10. O’Flynn E, Andrew J, Hutch A, et al. The specialist surgeon workforce in east, central and southern africa: a situation anal-

ysis. World J Surg . 2016;40(11):2620–2627. doi: 10.10 07/s0 0268- 016- 3601- 3 .

11. Hutch A, Bekele A, O’Flynn E, et al. The brain drain myth: retention of specialist surgical graduates in east, central and

Southern Africa, 1974–2013. World J Surg . 2017;41(12):3046–3053. doi: 10.10 07/s0 0268- 017- 4307- x .

12. Theuri C. COMESA remains world’s fastest growing global economic bloc, Money Moves . 2016 https://face2faceafrica.com/article/

comesa- remains- worlds- fastest- growing- global- economic- bloc? _ _ hstc=253763031.2bd8ab808297a8f565e6e7f39c583f42.

1536737308082.1536737308082.1536737308082.1& _ _ hssc=253763031.2.1536737308084& _ _ hsfp=1359679310 ,Accessed

September 12, 2018 .

13. COMESA. COMESA economies robust. COMESA Summit Bullettin . 2016;(2):1-2. www.comesa.int .

14. World Health Organization. (2012, June). Health systems in Africa: community perceptions and perspectives. Retrieved from:

https://afro.who.int/publications/health-systems-africa-community-perceptions-and-perspectives .

1 out of 8

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.