Relationship Development in Alliance Contracting for Construction

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/12

|18

|9252

|38

Report

AI Summary

This report analyzes a research paper titled "Alliance contracting: adding value through relationship development" published in Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management (ECAM). The study, conducted by Davis and Love, explores the significance of relationship development in successful alliance contracting within the Australian construction industry. The authors propose a three-phase model – assessment, commitment, and endurance – for building alliances. The research, based on 49 in-depth interviews with industry practitioners, highlights trust, commitment, and organizational development as critical factors. The paper emphasizes the need for a collaborative approach, moving away from traditional adversarial practices, to foster value creation and innovation throughout the supply chain. The model aims to promote reflective learning and mutual trust, ultimately improving project performance and sustainability in construction alliances. The research also addresses the challenges of maintaining relationships throughout a project's lifecycle, especially in the context of changing economic conditions and the increasing use of alliances as an alternative procurement method.

Alliance contracting: adding value

through relationship development

Peter Davis and Peter Love

Department of Construction Management, Curtin University of Technolo

Perth, Australia

Abstract

Purpose – Alliancing and partnering have been extensively used to stimulate collaborative relat

between supply chain members as well as to address the need to improve the performance of

Recognising the need to build and sustain relationships in alliances, the paper aims to present

thatis developed and tested by industry practitioners who are regularly involved with alliance

contracting. The developed model can be used to encourage a culture of reflective learning and

trust,beyond merely project-specific performance outcomes.

Design/methodology/approach – To examine the applicability of the conceptual model to allianc

contracting in construction an exploratory approach was adopted.A total of 49 in-depth interviews

were conducted over a six-month period with a variety of industry practitioners (clients,contractors,

design consultants, construction lawyers, and alliance facilitators) who had extensive experienc

working in alliance contracts.Interviews were used as the mechanism to examine the themes and

constructs identified from the literature.

Findings – The relationship developmentprocess represents a majorcontributorto successful

alliancecontracting and can add considerablevalue throughoutthe supply chain.Thereis a

recognisable structure to relationship development that is underpinned by specific themes that

be considered when managing the alliance relationship.Trust and commitment are explicit elements

that should be continually maintained in an alliance contract, and can significantly contribute to

learning from joint problem-solving activities. From the respondents’perspectives it appears that the

entireprocessof relationship developmenthinged around individualrelationships,trust and

organizational development.

Practical implications – A three-phase model for building alliances is developed and can be used

by practitioners to improve the performance of projects.

Social implications – It is suggested that the developed model can be used to promote a culture

reflective learning and mutual trust,beyond merely project-specific performance outcomes.

Originality/value – The research develops a model for relationship development and maintenan

in construction projects so that sustainable relationships can be established.The proposed model

includes three phases:assessment,commitment and endurance.Being able to manage each of these

phases effectively is critical for successful project delivery and stimulating innovation.

Keywords Contracting out, Partnership, Strategic alliances, Supply chain management,

Supplier relations

Paper type Research paper

Introduction

The Australian construction industry has been going through an intense period o

introspection since the publication of various reports identifying the industry’s p

performance and productivity (e.g.NPWC and NBCC,1990;Gyles,1991;CIDA,1993;

APCC,1998;DIST, 1998,1999;Cole,2002).Extensive criticisms of the construction

industry have followed from these initiatives together with the general consensu

reforms, and in particular improvements in quality, productivity and performanc

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/0969-9988.htm

ECAM

18,5

444

Received 17 February 2010

Revised 28 September 2010

Accepted 19 October 2010

Engineering,Construction and

Architectural Management

Vol.18 No.5,2011

pp.444-461

q Emerald Group Publishing Limited

0969-9988

DOI 10.1108/09699981111165167

through relationship development

Peter Davis and Peter Love

Department of Construction Management, Curtin University of Technolo

Perth, Australia

Abstract

Purpose – Alliancing and partnering have been extensively used to stimulate collaborative relat

between supply chain members as well as to address the need to improve the performance of

Recognising the need to build and sustain relationships in alliances, the paper aims to present

thatis developed and tested by industry practitioners who are regularly involved with alliance

contracting. The developed model can be used to encourage a culture of reflective learning and

trust,beyond merely project-specific performance outcomes.

Design/methodology/approach – To examine the applicability of the conceptual model to allianc

contracting in construction an exploratory approach was adopted.A total of 49 in-depth interviews

were conducted over a six-month period with a variety of industry practitioners (clients,contractors,

design consultants, construction lawyers, and alliance facilitators) who had extensive experienc

working in alliance contracts.Interviews were used as the mechanism to examine the themes and

constructs identified from the literature.

Findings – The relationship developmentprocess represents a majorcontributorto successful

alliancecontracting and can add considerablevalue throughoutthe supply chain.Thereis a

recognisable structure to relationship development that is underpinned by specific themes that

be considered when managing the alliance relationship.Trust and commitment are explicit elements

that should be continually maintained in an alliance contract, and can significantly contribute to

learning from joint problem-solving activities. From the respondents’perspectives it appears that the

entireprocessof relationship developmenthinged around individualrelationships,trust and

organizational development.

Practical implications – A three-phase model for building alliances is developed and can be used

by practitioners to improve the performance of projects.

Social implications – It is suggested that the developed model can be used to promote a culture

reflective learning and mutual trust,beyond merely project-specific performance outcomes.

Originality/value – The research develops a model for relationship development and maintenan

in construction projects so that sustainable relationships can be established.The proposed model

includes three phases:assessment,commitment and endurance.Being able to manage each of these

phases effectively is critical for successful project delivery and stimulating innovation.

Keywords Contracting out, Partnership, Strategic alliances, Supply chain management,

Supplier relations

Paper type Research paper

Introduction

The Australian construction industry has been going through an intense period o

introspection since the publication of various reports identifying the industry’s p

performance and productivity (e.g.NPWC and NBCC,1990;Gyles,1991;CIDA,1993;

APCC,1998;DIST, 1998,1999;Cole,2002).Extensive criticisms of the construction

industry have followed from these initiatives together with the general consensu

reforms, and in particular improvements in quality, productivity and performanc

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/0969-9988.htm

ECAM

18,5

444

Received 17 February 2010

Revised 28 September 2010

Accepted 19 October 2010

Engineering,Construction and

Architectural Management

Vol.18 No.5,2011

pp.444-461

q Emerald Group Publishing Limited

0969-9988

DOI 10.1108/09699981111165167

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

the way in which projects are delivered are required.In particular,it has been

acknowledged that an integrated and seamless supply chain is required in construction

to deliver “value money” and encourage innovation (Cox and Ireland,2002).At the

heartof an integrated supply chain is the formation ofcollaborative relationships

(Ellram,1990;Araujo et al.,1999).

Alliancing and partnering have been extensively used to stimulate collaborative

relations between supply chain members as well as address the need to improve the

performance of projects (e.g.Abudayyeh,1994;Larson,1995;Black et al.,2000;Holt

et al., 2000; Li et al., 2001; Anvuur and Kumaraswamy, 2007; Wong et al., 2008). While

parties that have formed an alliance or entered into a partnering agreement have every

intention to operate in a collaborative manner there is always a danger that a party

may attempt to exploit the other,especially if used as an “add on” to pre-existing

construction contract forms where the fundamental transactional nature of the contract

remains the same (Howell et al.,1996;Uher,1999;Love et al.,2002).

When entering into an alliance it is essential that the mindsets of parties break away

from the traditional “adversarial” approach inherent within construction and attempt

to work cooperatively (focussing on building and perpetuating relationships)to

enhance communication and create value throughoutthe supply chain (Holtet al.,

2000).Alliancing is now recognised as a formal contracting arrangement.Two types

tend to dominate the Australian marketplace: cost competitive and pure alliances (Love

et al., 2010). In particular, alliance relationship development process is pivotal to value

creation asit enablestrust to be nurtured,knowledgetransfer,continualgoal

alignment,and network maintenance within the supply chain (Araujo etal.,1999;

Arin˜o et al., 2005). There is, however, a propensity for parties to eschew developing and

maintaining the “collaborative” nature of their alliance once it has been established by

parties (Love et al.,2010,2011).

Since the subprime crisis and collapse of the capital markets, the viability of PPPs has

increasingly come into question (Regan et al., 2011). According to Regan et al. (2011) the

funding methods previously used are not applicable in the prevailing economic climate

and as a result,alternative procurementand finance arrangements forprocuring

infrastructure projects (including alliances) should be considered. Alliances have proven

to be effective in delivering infrastructure projects in Australia (e.g. Jefferies et al., 2000;

Love et al., 2010,2011),as they engendercollaboration and integration between

client/owner organizations (e.g.state or authority) and non-owner participants (NOPs)

(e.g. design consultant, construction contractor, supplier) (Love et al., 2002). Essentially,

the alliance procurement arrangement aims to share both risk and reward amongst the

project team via the use of a risk reward model (Love et al., 2011). A challenge for clients

and NOPs is to maintain and sustain their relationship throughout a project’s life cycle

(Arin˜o et al.,2005;Love etal.,2011).Recognising the need to build and sustain

relationships in alliances, a model is developed from the normative literature and tested

by industry practitioners who are regularly involved with alliance contracting.It is

proffered that the developed modelcan be used to encourage a culture of reflective

learning and mutual trust,beyond merely project-specific performance outcomes.

Relationship development

Relationship development is an inherent feature of relationship marketing.A plethora

of definitions of relationship marketing can be found in the normative literature.For

Alliance

contracting

445

acknowledged that an integrated and seamless supply chain is required in construction

to deliver “value money” and encourage innovation (Cox and Ireland,2002).At the

heartof an integrated supply chain is the formation ofcollaborative relationships

(Ellram,1990;Araujo et al.,1999).

Alliancing and partnering have been extensively used to stimulate collaborative

relations between supply chain members as well as address the need to improve the

performance of projects (e.g.Abudayyeh,1994;Larson,1995;Black et al.,2000;Holt

et al., 2000; Li et al., 2001; Anvuur and Kumaraswamy, 2007; Wong et al., 2008). While

parties that have formed an alliance or entered into a partnering agreement have every

intention to operate in a collaborative manner there is always a danger that a party

may attempt to exploit the other,especially if used as an “add on” to pre-existing

construction contract forms where the fundamental transactional nature of the contract

remains the same (Howell et al.,1996;Uher,1999;Love et al.,2002).

When entering into an alliance it is essential that the mindsets of parties break away

from the traditional “adversarial” approach inherent within construction and attempt

to work cooperatively (focussing on building and perpetuating relationships)to

enhance communication and create value throughoutthe supply chain (Holtet al.,

2000).Alliancing is now recognised as a formal contracting arrangement.Two types

tend to dominate the Australian marketplace: cost competitive and pure alliances (Love

et al., 2010). In particular, alliance relationship development process is pivotal to value

creation asit enablestrust to be nurtured,knowledgetransfer,continualgoal

alignment,and network maintenance within the supply chain (Araujo etal.,1999;

Arin˜o et al., 2005). There is, however, a propensity for parties to eschew developing and

maintaining the “collaborative” nature of their alliance once it has been established by

parties (Love et al.,2010,2011).

Since the subprime crisis and collapse of the capital markets, the viability of PPPs has

increasingly come into question (Regan et al., 2011). According to Regan et al. (2011) the

funding methods previously used are not applicable in the prevailing economic climate

and as a result,alternative procurementand finance arrangements forprocuring

infrastructure projects (including alliances) should be considered. Alliances have proven

to be effective in delivering infrastructure projects in Australia (e.g. Jefferies et al., 2000;

Love et al., 2010,2011),as they engendercollaboration and integration between

client/owner organizations (e.g.state or authority) and non-owner participants (NOPs)

(e.g. design consultant, construction contractor, supplier) (Love et al., 2002). Essentially,

the alliance procurement arrangement aims to share both risk and reward amongst the

project team via the use of a risk reward model (Love et al., 2011). A challenge for clients

and NOPs is to maintain and sustain their relationship throughout a project’s life cycle

(Arin˜o et al.,2005;Love etal.,2011).Recognising the need to build and sustain

relationships in alliances, a model is developed from the normative literature and tested

by industry practitioners who are regularly involved with alliance contracting.It is

proffered that the developed modelcan be used to encourage a culture of reflective

learning and mutual trust,beyond merely project-specific performance outcomes.

Relationship development

Relationship development is an inherent feature of relationship marketing.A plethora

of definitions of relationship marketing can be found in the normative literature.For

Alliance

contracting

445

example,Berry (1983,p.143,cited in Ferguson and Brown,1991) defines relationship

marketing as the “process of establishing and maintaining mutually beneficiallong

term relationships among organization and theircustomers,employees and other

stakeholders”(p. 143).Gro¨nroos(1996,p. 7) statesthat the underlying aim of

relationshipmarketingis “to identify and establish,maintain,and enhance

relationshipswith customersand otherstakeholders,at a profit, so that the

objectives of all parties involved are met; and this is done by mutual exchange

fulfilment of promises”.Contrastingly,Morris et al.(1998,p.239) bring the aspect of

strategy in to play and suggest that relationship marketing is “a strategic orient

adopted by both the buyer and seller organizations, which represents a commit

long term mutually beneficial collaboration”.While there is a lack of consensus on a

definitionfor relationshipmarketing,conceptsof trust building/maintenance,

long-term commitment,and generation/evaluation ofmutualgoals can be seen to

be underlying themes. Moreover, these themes marry with those central to the

and partnering literature in construction (e.g.Anvuur and Kumaraswamy,2007).

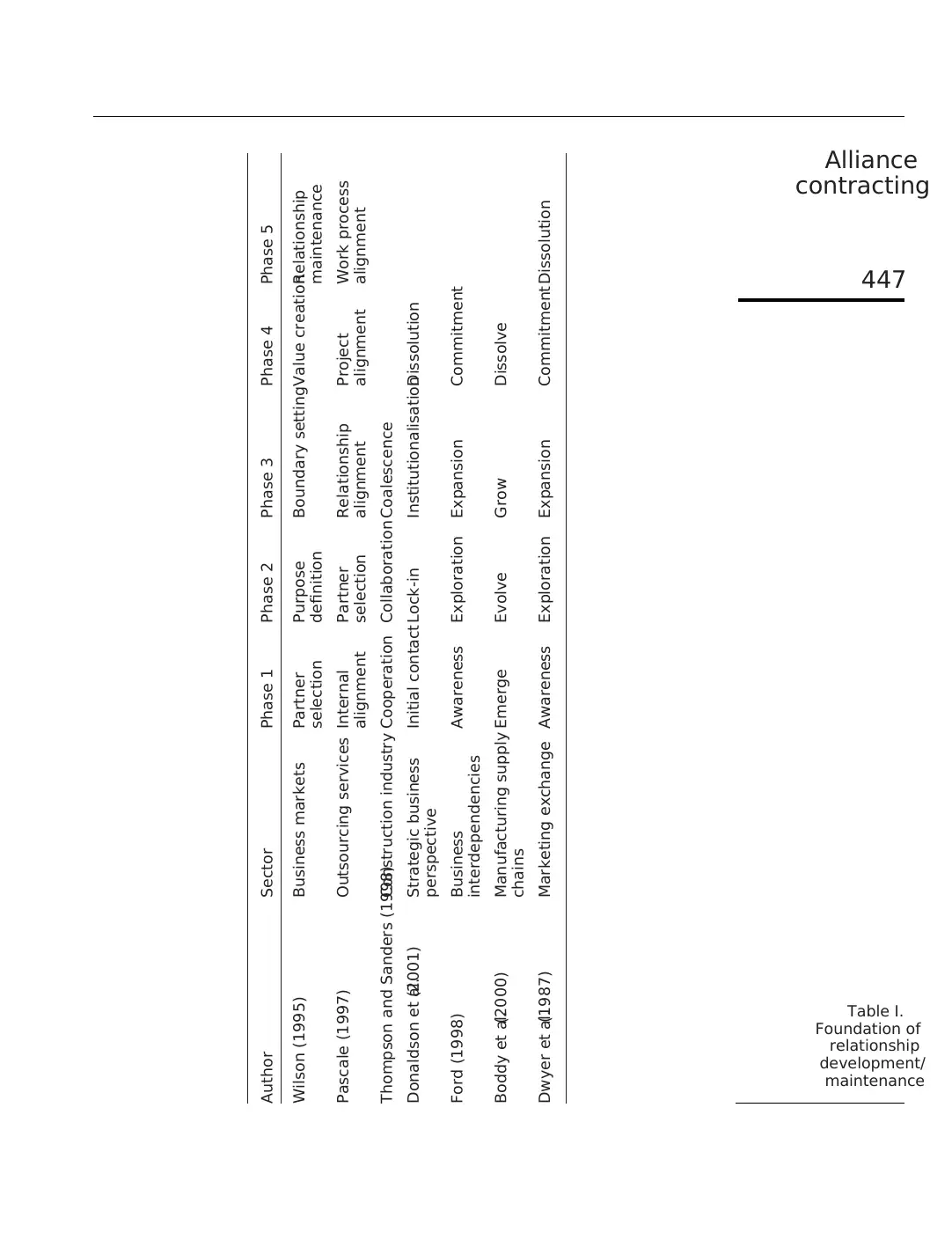

Relationship development,as a centralcomponent of exchange management,has

been recognised as a series of iterative phases (Table I). Wilson (1995) identifie

selection,purposedefinition,boundary setting,valuecreation and relationship

maintenanceas stageswhen commitment,trust, cooperation and mutualgoal

development become either active or latent primary components.Active components

require significant management time and energy,whilst latent components require

limited time or attention (Wilson, 1995). Likewise, Pascale (1997) refers to five p

relationship development appropriate for outsourcing services as internal alignm

partner selection,partner relationship alignment,project alignment and work process

alignment.A phased continuum isoffered by Thompson and Sanders(1998)

encompassing the stages of cooperation, collaboration and coalescence. Donald

(2001)refer to initial contact,lock-in,institutionalisation,and dissolutionas

relationshipdevelopmentphases.Ford (1998)uses awareness,exploration,

expansionand commitmentas terms to describebusinessinterdependencies.

Conversely,Boddy etal. (2000)conceptualise relationship developmentin terms of

emerge, evolve, grow and dissolve. Dwyer et al. (1987) define relationship deve

in marketing exchange relationships as an iterative process comprising several

of awareness,exploration,expansion,commitment and dissolution.

In any exchange there are contractualissues thatshould be addressed such as

discrete and relational transactions (Dwyer et al.,2000).A discrete transaction is the

foundation ofa relationship whereby money is exchanged fora simple specified

commodity.Discrete transactions entaillimited communication and narrow content.

However,prolonged relationalexchangefounded through dependencepersonal

characteristics,benefit from deeper communication,cooperative planning and higher

expectations of trustworthiness (Anvuur and Kumaraswamy, 2007; Wong et al.,

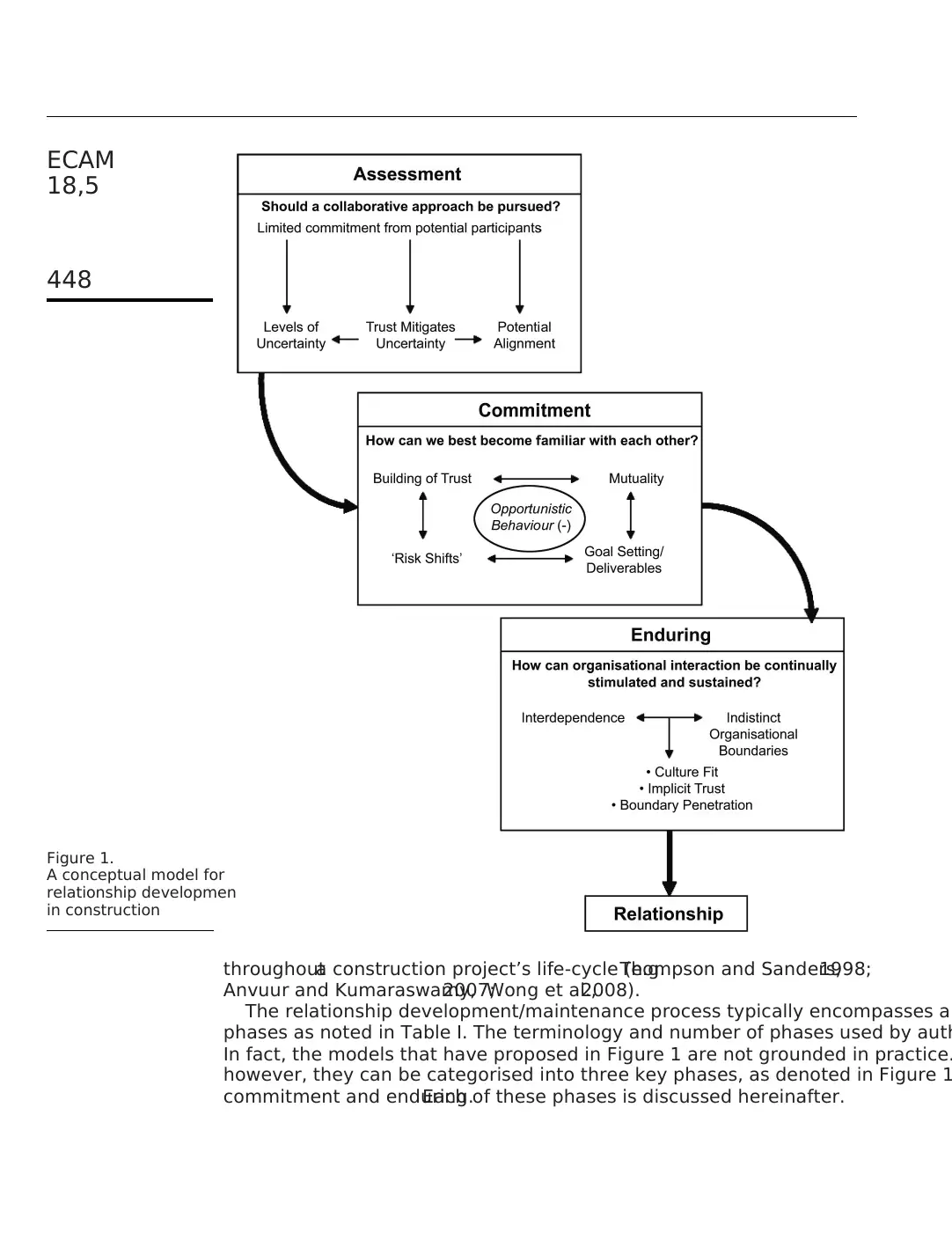

Drawing on the work of severalauthorsthat have examinedrelationship

development/maintenance (Table I),a conceptualmodelis proposed in Figure 1

(e.g.Ford et al.,1985;Wilson,1995;Araujo et al.,1999;Thompson and Sanders,1998;

Dwyer etal.,2000;Anvuurand Kumaraswamy,2007).There exists a morass of

research that has examined alliances since the calls of the Latham Report (1994to

ameliorate integration and engender trust in projects. However, there have only

limited number of studies that have examined the relationship development pro

ECAM

18,5

446

marketing as the “process of establishing and maintaining mutually beneficiallong

term relationships among organization and theircustomers,employees and other

stakeholders”(p. 143).Gro¨nroos(1996,p. 7) statesthat the underlying aim of

relationshipmarketingis “to identify and establish,maintain,and enhance

relationshipswith customersand otherstakeholders,at a profit, so that the

objectives of all parties involved are met; and this is done by mutual exchange

fulfilment of promises”.Contrastingly,Morris et al.(1998,p.239) bring the aspect of

strategy in to play and suggest that relationship marketing is “a strategic orient

adopted by both the buyer and seller organizations, which represents a commit

long term mutually beneficial collaboration”.While there is a lack of consensus on a

definitionfor relationshipmarketing,conceptsof trust building/maintenance,

long-term commitment,and generation/evaluation ofmutualgoals can be seen to

be underlying themes. Moreover, these themes marry with those central to the

and partnering literature in construction (e.g.Anvuur and Kumaraswamy,2007).

Relationship development,as a centralcomponent of exchange management,has

been recognised as a series of iterative phases (Table I). Wilson (1995) identifie

selection,purposedefinition,boundary setting,valuecreation and relationship

maintenanceas stageswhen commitment,trust, cooperation and mutualgoal

development become either active or latent primary components.Active components

require significant management time and energy,whilst latent components require

limited time or attention (Wilson, 1995). Likewise, Pascale (1997) refers to five p

relationship development appropriate for outsourcing services as internal alignm

partner selection,partner relationship alignment,project alignment and work process

alignment.A phased continuum isoffered by Thompson and Sanders(1998)

encompassing the stages of cooperation, collaboration and coalescence. Donald

(2001)refer to initial contact,lock-in,institutionalisation,and dissolutionas

relationshipdevelopmentphases.Ford (1998)uses awareness,exploration,

expansionand commitmentas terms to describebusinessinterdependencies.

Conversely,Boddy etal. (2000)conceptualise relationship developmentin terms of

emerge, evolve, grow and dissolve. Dwyer et al. (1987) define relationship deve

in marketing exchange relationships as an iterative process comprising several

of awareness,exploration,expansion,commitment and dissolution.

In any exchange there are contractualissues thatshould be addressed such as

discrete and relational transactions (Dwyer et al.,2000).A discrete transaction is the

foundation ofa relationship whereby money is exchanged fora simple specified

commodity.Discrete transactions entaillimited communication and narrow content.

However,prolonged relationalexchangefounded through dependencepersonal

characteristics,benefit from deeper communication,cooperative planning and higher

expectations of trustworthiness (Anvuur and Kumaraswamy, 2007; Wong et al.,

Drawing on the work of severalauthorsthat have examinedrelationship

development/maintenance (Table I),a conceptualmodelis proposed in Figure 1

(e.g.Ford et al.,1985;Wilson,1995;Araujo et al.,1999;Thompson and Sanders,1998;

Dwyer etal.,2000;Anvuurand Kumaraswamy,2007).There exists a morass of

research that has examined alliances since the calls of the Latham Report (1994to

ameliorate integration and engender trust in projects. However, there have only

limited number of studies that have examined the relationship development pro

ECAM

18,5

446

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Author Sector Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Phase 4 Phase 5

Wilson (1995) Business markets Partner

selection

Purpose

definition

Boundary settingValue creationRelationship

maintenance

Pascale (1997) Outsourcing services Internal

alignment

Partner

selection

Relationship

alignment

Project

alignment

Work process

alignment

Thompson and Sanders (1998)Construction industry Cooperation Collaboration Coalescence

Donaldson et al.(2001) Strategic business

perspective

Initial contact Lock-in InstitutionalisationDissolution

Ford (1998) Business

interdependencies

Awareness Exploration Expansion Commitment

Boddy et al.(2000) Manufacturing supply

chains

Emerge Evolve Grow Dissolve

Dwyer et al.(1987) Marketing exchange Awareness Exploration Expansion CommitmentDissolution

Table I.

Foundation of

relationship

development/

maintenance

Alliance

contracting

447

Wilson (1995) Business markets Partner

selection

Purpose

definition

Boundary settingValue creationRelationship

maintenance

Pascale (1997) Outsourcing services Internal

alignment

Partner

selection

Relationship

alignment

Project

alignment

Work process

alignment

Thompson and Sanders (1998)Construction industry Cooperation Collaboration Coalescence

Donaldson et al.(2001) Strategic business

perspective

Initial contact Lock-in InstitutionalisationDissolution

Ford (1998) Business

interdependencies

Awareness Exploration Expansion Commitment

Boddy et al.(2000) Manufacturing supply

chains

Emerge Evolve Grow Dissolve

Dwyer et al.(1987) Marketing exchange Awareness Exploration Expansion CommitmentDissolution

Table I.

Foundation of

relationship

development/

maintenance

Alliance

contracting

447

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

throughouta construction project’s life-cycle (e.g.Thompson and Sanders,1998;

Anvuur and Kumaraswamy,2007;Wong et al.,2008).

The relationship development/maintenance process typically encompasses a

phases as noted in Table I. The terminology and number of phases used by auth

In fact, the models that have proposed in Figure 1 are not grounded in practice.

however, they can be categorised into three key phases, as denoted in Figure 1

commitment and enduring.Each of these phases is discussed hereinafter.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model for

relationship development

in construction

ECAM

18,5

448

Anvuur and Kumaraswamy,2007;Wong et al.,2008).

The relationship development/maintenance process typically encompasses a

phases as noted in Table I. The terminology and number of phases used by auth

In fact, the models that have proposed in Figure 1 are not grounded in practice.

however, they can be categorised into three key phases, as denoted in Figure 1

commitment and enduring.Each of these phases is discussed hereinafter.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model for

relationship development

in construction

ECAM

18,5

448

Assessment phase

Choosing the right partner and strategically positioning an organization in an alliance

is a challenging mission for all parties concerned (Donaldson and O’Toole, 2001;Love

et al., 2002). More often than not it is clients who initiate the use of alliance contract in

construction and projectteam memberscast themselvesinto a projectwithout

adequately surveying the implications ofthe relationships they have entered into.

Initialquestions that should be considered are:should a collaborative approach be

pursued?Which relationshipwarrants development?And how should an

organization’sstructurebe developed tomanagethe collaborativerelationship

(Donaldson and O’Toole, 2001)? Boddy et al. (2000) suggest that organizations need to

be cognisant of three factors when embarking on a collaborative strategy:

(1) The intra-organizationalcontextand its affecton initiating behaviour in a

relationship – for example,historicalactions of staff hindering collaborative

relations.

(2) Developmentof intra-organizationalframeworks thatencourage cooperative

behaviour with the firms involved in the collaborative relationship.

(3) The developmentof a formal institutionprovidingsupportto further

cooperation.This is likened to “norming” behaviour where early encounters

within relationship development create project-specific objectives and attempt

to improve interpersonal relationships and team membership (Thompson and

Sanders,1998).

Initially the relationship developmentprocess relies on one party identifying or

becoming aware of a need thatthey are capable of fulfilling (Ford etal.,1985).In

essencethis first phaseis one of strategy wherepotentialpartnerslook for

organizational alignment and strategic fit ( Johnson and Scholes,1999).Above all the

organization should attempt to determine goals and objectives at an institutionalor

project level depending on their strategy (Thompson and Sanders, 1998). To participate

effectively an organization should be able to analyse and describe itself in terms that

prospective partners can relate to and comprehend (Ford et al.,1985).

While the scope ofthe relationship atthis stage lacks definition in terms of

requirementsand benefits,consideration may begiven to finance,plant and

equipment, technology and managerial expertise that is required (Ford, 1982). This is a

criticalphase in relationship development process,which willbecome evident with

little realor perceived commitment.Commitment is difficult to assess and partners

may choose to proceed with the relationship slowly or enactlimited exchanges to

minimise commitment (Ford,1998).

To move away from competingobjectivesstakeholdersshould improve

communication and increasetrust (Thompson and Sanders,1998).Becauseof

difficulties in analysing partners, uncertainty remains high and any judgements will be

made on reputation as a substitute forexperience (Ford,1982).Discussion with

multiple partners is a typical risk reduction strategy (Wilson, 1995). Mutual trust may

begin to develop as cultural distance decreases and partners become familiar with the

organizational norms and behaviours that have been established (Wong et al.,2008).

Trust developmentmitigates high levels ofuncertainty more quickly with some

potentialpartners than others.Consequently,certain parties willnot be considered

appropriate for forming a relationship with.A relationship may failif one party

Alliance

contracting

449

Choosing the right partner and strategically positioning an organization in an alliance

is a challenging mission for all parties concerned (Donaldson and O’Toole, 2001;Love

et al., 2002). More often than not it is clients who initiate the use of alliance contract in

construction and projectteam memberscast themselvesinto a projectwithout

adequately surveying the implications ofthe relationships they have entered into.

Initialquestions that should be considered are:should a collaborative approach be

pursued?Which relationshipwarrants development?And how should an

organization’sstructurebe developed tomanagethe collaborativerelationship

(Donaldson and O’Toole, 2001)? Boddy et al. (2000) suggest that organizations need to

be cognisant of three factors when embarking on a collaborative strategy:

(1) The intra-organizationalcontextand its affecton initiating behaviour in a

relationship – for example,historicalactions of staff hindering collaborative

relations.

(2) Developmentof intra-organizationalframeworks thatencourage cooperative

behaviour with the firms involved in the collaborative relationship.

(3) The developmentof a formal institutionprovidingsupportto further

cooperation.This is likened to “norming” behaviour where early encounters

within relationship development create project-specific objectives and attempt

to improve interpersonal relationships and team membership (Thompson and

Sanders,1998).

Initially the relationship developmentprocess relies on one party identifying or

becoming aware of a need thatthey are capable of fulfilling (Ford etal.,1985).In

essencethis first phaseis one of strategy wherepotentialpartnerslook for

organizational alignment and strategic fit ( Johnson and Scholes,1999).Above all the

organization should attempt to determine goals and objectives at an institutionalor

project level depending on their strategy (Thompson and Sanders, 1998). To participate

effectively an organization should be able to analyse and describe itself in terms that

prospective partners can relate to and comprehend (Ford et al.,1985).

While the scope ofthe relationship atthis stage lacks definition in terms of

requirementsand benefits,consideration may begiven to finance,plant and

equipment, technology and managerial expertise that is required (Ford, 1982). This is a

criticalphase in relationship development process,which willbecome evident with

little realor perceived commitment.Commitment is difficult to assess and partners

may choose to proceed with the relationship slowly or enactlimited exchanges to

minimise commitment (Ford,1998).

To move away from competingobjectivesstakeholdersshould improve

communication and increasetrust (Thompson and Sanders,1998).Becauseof

difficulties in analysing partners, uncertainty remains high and any judgements will be

made on reputation as a substitute forexperience (Ford,1982).Discussion with

multiple partners is a typical risk reduction strategy (Wilson, 1995). Mutual trust may

begin to develop as cultural distance decreases and partners become familiar with the

organizational norms and behaviours that have been established (Wong et al.,2008).

Trust developmentmitigates high levels ofuncertainty more quickly with some

potentialpartners than others.Consequently,certain parties willnot be considered

appropriate for forming a relationship with.A relationship may failif one party

Alliance

contracting

449

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

believes thatthe other has no intention ofbuilding and sustaining a relationship.

Selection disqualification can also occurif displayed behaviours orcompetencies

appear to be less than expected (Boddy et al.,2000).

During this phase individual parties are not exclusively committed to one ano

and there is a limited degree of trust present, as guarded exchanges of informa

place.However,trust willincrease as a consequence of perceived investments of an

economic or social nature become identified.They may be product or person related,

designed to add project value. Comparison with alternative potential relationshi

take place, but eventually a decision based on limited information available will

continuation to the commitment phase.

Commitment phase

The commitment phase is intensive and is often referred to as definition (Wilson

lock-in (Donaldson and O’Toole,2001)or exploratory (Dwyer etal.,1985).Serious

discussion and negotiation takes place and information is exchanged juxtapose

mutual learning. The negotiationprocess will invariably entail bilateral

communication of wants,issues,inputs and priorities (Dwyer et al.,1987).Ford et al.

(1985) use the term “mutuality”,as this phase rests on the importance of determining

common goals. Mutuality is a measure of how much a company is prepared to g

its own individual goals or intentions, in order to increase positive outcomes of o

it is a trade off between opportunism and long-term gain.

In this phase trust is not principally in play and there are mutual concerns abo

commitment.However,the parties to the potentialrelationship must display serious

interestand consider relationship obligations to overcome a propensity to depart

(Dwyeret al., 1987).Additionalcommitmenthas proclivity with trust,which is

fundamental to relationship interaction (Dwyer et al., 1987; Love et al., 2002; W

2008).Trust affects buyers’behaviour and attitude;it impacts on negotiation and

bargaining. Social bonding and trust development underpin relationship develop

(Wong et al.,2008).If they are not in place,then invariably a lack of personal trust or

incompatible personal chemistry are blamed for failure (Wilson, 1995). At this st

relationship needs to reach a business friendship level. Due to the seeming abse

shared culture and understanding,the project’s scope and goaldefinition become

criticaldecisions for the relationship partners which are obtained through technic

knowledge and social bonds (Figure 1).

Norms thatdictate standards ofconductare adopted.In effectregulations of

exchange are created and become ground rules for future exchanges (Ford,1982).

Generalised expectations guide perceptions of social exchange and may exert p

influences upon behaviour. This is supported by Boddy et al. (2000), who indica

dealings become more directas relationships develop.In the formative phases of

relation development,risk is prevalent because partners are assessing their strategi

operationaland tacticalpositioning in the project.As trust and the desire to work

togetherincreases the potentialpartners’risk-shifts are augmented.Examples of

risk-shifts include:a large concession thatrequires reciprocation,a proposalfor a

compromise, a unilateral action of tension reduction, or a candid statement con

motives and priorities (Dwyer et al.,1987).

In the context of risk-shifts,Ford (1998)refers to adaptations that may be either

formal or informal.Formal adaptations are contractual agreements that may take t

ECAM

18,5

450

Selection disqualification can also occurif displayed behaviours orcompetencies

appear to be less than expected (Boddy et al.,2000).

During this phase individual parties are not exclusively committed to one ano

and there is a limited degree of trust present, as guarded exchanges of informa

place.However,trust willincrease as a consequence of perceived investments of an

economic or social nature become identified.They may be product or person related,

designed to add project value. Comparison with alternative potential relationshi

take place, but eventually a decision based on limited information available will

continuation to the commitment phase.

Commitment phase

The commitment phase is intensive and is often referred to as definition (Wilson

lock-in (Donaldson and O’Toole,2001)or exploratory (Dwyer etal.,1985).Serious

discussion and negotiation takes place and information is exchanged juxtapose

mutual learning. The negotiationprocess will invariably entail bilateral

communication of wants,issues,inputs and priorities (Dwyer et al.,1987).Ford et al.

(1985) use the term “mutuality”,as this phase rests on the importance of determining

common goals. Mutuality is a measure of how much a company is prepared to g

its own individual goals or intentions, in order to increase positive outcomes of o

it is a trade off between opportunism and long-term gain.

In this phase trust is not principally in play and there are mutual concerns abo

commitment.However,the parties to the potentialrelationship must display serious

interestand consider relationship obligations to overcome a propensity to depart

(Dwyeret al., 1987).Additionalcommitmenthas proclivity with trust,which is

fundamental to relationship interaction (Dwyer et al., 1987; Love et al., 2002; W

2008).Trust affects buyers’behaviour and attitude;it impacts on negotiation and

bargaining. Social bonding and trust development underpin relationship develop

(Wong et al.,2008).If they are not in place,then invariably a lack of personal trust or

incompatible personal chemistry are blamed for failure (Wilson, 1995). At this st

relationship needs to reach a business friendship level. Due to the seeming abse

shared culture and understanding,the project’s scope and goaldefinition become

criticaldecisions for the relationship partners which are obtained through technic

knowledge and social bonds (Figure 1).

Norms thatdictate standards ofconductare adopted.In effectregulations of

exchange are created and become ground rules for future exchanges (Ford,1982).

Generalised expectations guide perceptions of social exchange and may exert p

influences upon behaviour. This is supported by Boddy et al. (2000), who indica

dealings become more directas relationships develop.In the formative phases of

relation development,risk is prevalent because partners are assessing their strategi

operationaland tacticalpositioning in the project.As trust and the desire to work

togetherincreases the potentialpartners’risk-shifts are augmented.Examples of

risk-shifts include:a large concession thatrequires reciprocation,a proposalfor a

compromise, a unilateral action of tension reduction, or a candid statement con

motives and priorities (Dwyer et al.,1987).

In the context of risk-shifts,Ford (1998)refers to adaptations that may be either

formal or informal.Formal adaptations are contractual agreements that may take t

ECAM

18,5

450

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

form of special products.Informal adaptations are more ad hoc and arise to cope with

particular instances as the relationship develops, for example flexibility of resources to

cope with sudden demand.Boddy etal. (2000)have demonstrated thatinformal

cooperation orworking togethertranslatesinto new rolesas the relationship

development progresses.This development happens at severallevels and creates a

new context of working together, with cooperative behaviour embedding new values in

the wider context of both organizations.A counter point to this positive change is the

potential danger of unintentional behaviours developing as the relationship begins to

settle and parties become comfortable with one another. In support of these arguments

Ford (1982) states that commitment is built and displayed by the way in which a firm

organizes patterns of contact with its partner;the level of personnel involved and the

frequency of contact.

A relationship will remain fragile with limited commitment and can end relatively

easily;however,dissonance willnot dissolve the relationship development.It is

common for partners to have overall mutual interest,whilst simultaneously being in

conflict over what they should be doing for mutual achievement (Ford et al., 1985). The

parties to the relationship willstill make comparisons and measurementagainst

predetermined benchmarks,though performance satisfaction should reduce this trait

(Wilson, 1995). According to Thompson and Sanders (1998) several characteristics of a

committed environment include:

. longer term focus on the strategic goals of the stakeholders;

. relationship agreements without guarantees in terms of workload and resource

transfer;

. reduced duplication and process improvements;and

. shared authority with open and honest risk sharing.

Enduring phase

As the actors within the relationship development process become conscious of the

project’s definition and scope, their roles and responsibilities and the emergent culture

(norms and values),then the degree oforganizationalinteraction thattakes place

increases at all levels (Ford, 1982).Wilson (1995) refers to a “hybrid team” to describe

the actorsin the relationship developmentprocessthat commenceto acquire

communal assets. The team begin to become more interdependent (Dywer et al., 2000)

and organizational lines disappear (Thompson and Sanders,1998) during this phase.

Dwyer etal.(2000)suggest that when exemplary exchange takes place surpassing

expectations,attractivenessincreasestherebyenhancinggoal congruenceand

cooperativeness.Informalrules created by the team establish governance within the

structure ofthe relationship (Wilson,1995).Both organizations tend to alter their

procedures and make informaladaptations (Holt et al.,2000).Reciprocaladaptation

involves cost,as asset specific resources are difficult to transfer to other uses;these

actions bind the actors together.Thompson and Sanders (1998)highlightseveral

characteristics of a coalesced environment in an enduring phase that includes: a single

common performancemeasuring system;cooperativerelationshipssupported by

collaborative experiences and activities;cultures thatfit the projectand processes;

indistinctboundaries are penetrated by parties to the relationship and there is an

environment of implicit trust and shared risk.

Alliance

contracting

451

particular instances as the relationship develops, for example flexibility of resources to

cope with sudden demand.Boddy etal. (2000)have demonstrated thatinformal

cooperation orworking togethertranslatesinto new rolesas the relationship

development progresses.This development happens at severallevels and creates a

new context of working together, with cooperative behaviour embedding new values in

the wider context of both organizations.A counter point to this positive change is the

potential danger of unintentional behaviours developing as the relationship begins to

settle and parties become comfortable with one another. In support of these arguments

Ford (1982) states that commitment is built and displayed by the way in which a firm

organizes patterns of contact with its partner;the level of personnel involved and the

frequency of contact.

A relationship will remain fragile with limited commitment and can end relatively

easily;however,dissonance willnot dissolve the relationship development.It is

common for partners to have overall mutual interest,whilst simultaneously being in

conflict over what they should be doing for mutual achievement (Ford et al., 1985). The

parties to the relationship willstill make comparisons and measurementagainst

predetermined benchmarks,though performance satisfaction should reduce this trait

(Wilson, 1995). According to Thompson and Sanders (1998) several characteristics of a

committed environment include:

. longer term focus on the strategic goals of the stakeholders;

. relationship agreements without guarantees in terms of workload and resource

transfer;

. reduced duplication and process improvements;and

. shared authority with open and honest risk sharing.

Enduring phase

As the actors within the relationship development process become conscious of the

project’s definition and scope, their roles and responsibilities and the emergent culture

(norms and values),then the degree oforganizationalinteraction thattakes place

increases at all levels (Ford, 1982).Wilson (1995) refers to a “hybrid team” to describe

the actorsin the relationship developmentprocessthat commenceto acquire

communal assets. The team begin to become more interdependent (Dywer et al., 2000)

and organizational lines disappear (Thompson and Sanders,1998) during this phase.

Dwyer etal.(2000)suggest that when exemplary exchange takes place surpassing

expectations,attractivenessincreasestherebyenhancinggoal congruenceand

cooperativeness.Informalrules created by the team establish governance within the

structure ofthe relationship (Wilson,1995).Both organizations tend to alter their

procedures and make informaladaptations (Holt et al.,2000).Reciprocaladaptation

involves cost,as asset specific resources are difficult to transfer to other uses;these

actions bind the actors together.Thompson and Sanders (1998)highlightseveral

characteristics of a coalesced environment in an enduring phase that includes: a single

common performancemeasuring system;cooperativerelationshipssupported by

collaborative experiences and activities;cultures thatfit the projectand processes;

indistinctboundaries are penetrated by parties to the relationship and there is an

environment of implicit trust and shared risk.

Alliance

contracting

451

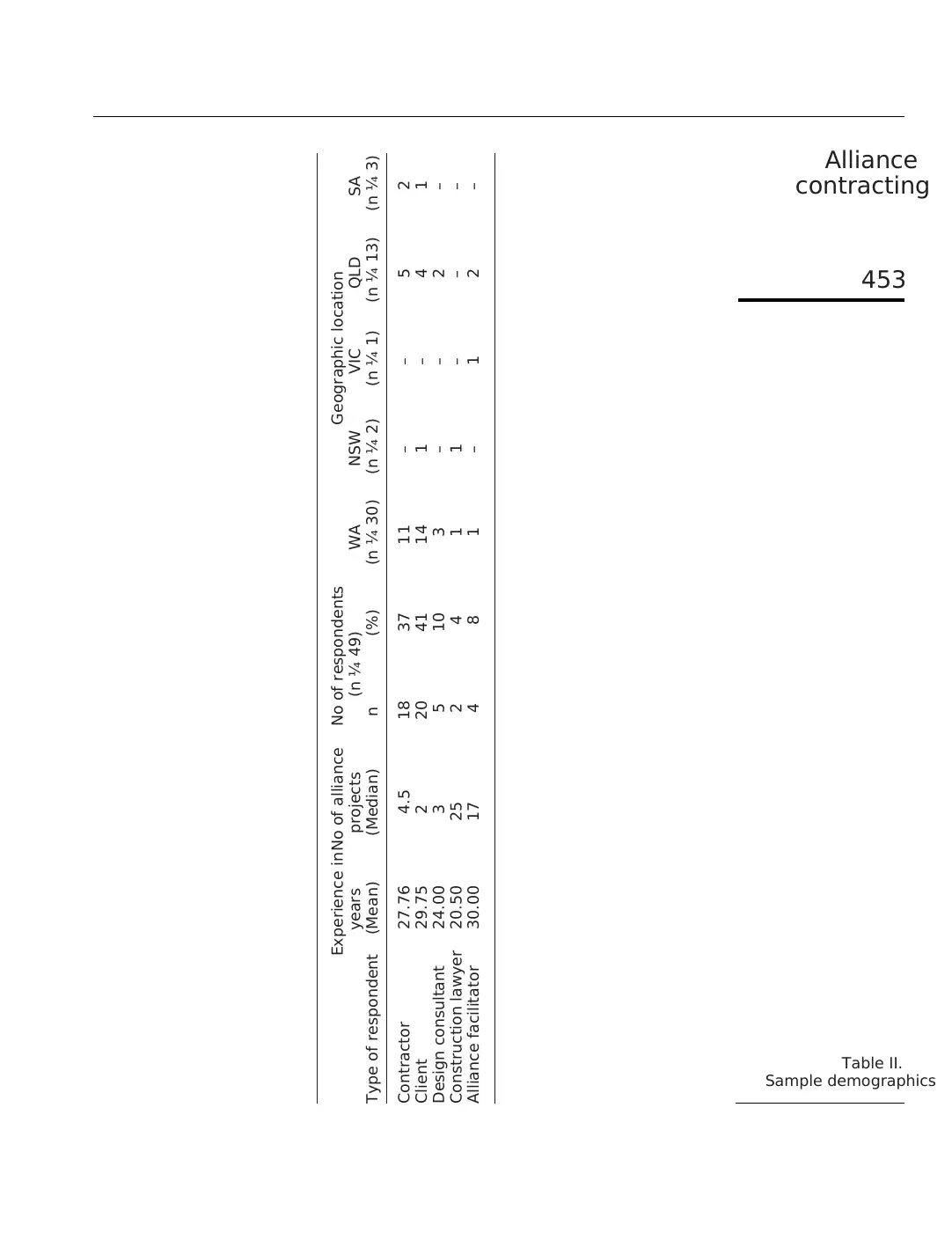

Research approach

To examine the applicability ofthe conceptualmodelto alliance contracting in

construction an exploratory approach was adopted.A total of 49 in-depth interviews

were conducted overa six-month period with a variety ofindustry practitioners

(clients, contractors, design consultants, construction lawyers, and alliance facil

who had extensive experience with working in alliance contracts (Table II). Inter

were used as the mechanism to examine the themes and constructs identified i

Figure 1.Interviews were chosen as the primary data collection mechanism beca

they are an effective tool for learning about matters that cannot be observed an

gaining an insight to people’s experiences in particular scenarios. According to T

and Bogdan (1984, p. 79), no other method “can provide the detailed understan

comes from directly observing people and listening to what they have to say at

scene”.

Industry practitioners were purposefully sampled from various states in Austr

and invited to participate in the research.Interviews were conducted at the offices of

interviewees. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim to allo

the nuances in the interview to be apparent in the text.The interviewees’ details were

coded to allow for anonymity,although all interviewees were aware that it might be

possible to identify them from the content of the text. The format of the intervie

kept as consistentas possiblefollowing thethemesassociated with developed

conceptual model.Interviews were kept open using phrases such as “tell me about

or “can you give me an example”. The open nature of the questions allowed for

of interest to be pursued as they arose without introducing bias in the response

were taken during the interview to support the tapes to maintain validity. Each

interviews varied in length from one to two hours.Interviews were open to stimulate

conversation and break down any barriersthat may haveexisted between the

interviewer and interviewee.

Data analysis

The text derived from the interviews was analysed using QSR N6 (which is a ver

NUD*IST and combines the efficientmanagementof Non-numericalUnstructured

Data with powerfulprocessesof Indexingand Theorising)and enabledthe

developmentof themes to be identified.One advantage ofsuch software is thatit

enables additional data sources and journal notes to be incorporated into the an

The development and re-assessment of themes as analysis progresses accords

calls for avoiding confining data to pre-determined sets of categories (Silverman

Kvale (1996,p.204) suggests that ad hoc methods for generating meaning enable

researcher access to “a variety of common-sense approaches to interview text u

interplayof techniquessuch as noting patterns,seeingplausibility,making

comparisons etc.”.

Using NUD*IST enabled the researchers to develop an organic approach to cod

as it enabled triggers or categories of interest in the text to be coded and used

track of emerging and developing ideas (Kvale, 1996).These codings can be modified,

integrated or migrated as the analysis progresses and the generation of reportsusing

Boolean search, facilitates the recognition of conflicts and contradictions. This p

enabled key themes identified in the conceptual model to be explored, which le

model being amended based upon the practitioners’experiences and viewpoints.

ECAM

18,5

452

To examine the applicability ofthe conceptualmodelto alliance contracting in

construction an exploratory approach was adopted.A total of 49 in-depth interviews

were conducted overa six-month period with a variety ofindustry practitioners

(clients, contractors, design consultants, construction lawyers, and alliance facil

who had extensive experience with working in alliance contracts (Table II). Inter

were used as the mechanism to examine the themes and constructs identified i

Figure 1.Interviews were chosen as the primary data collection mechanism beca

they are an effective tool for learning about matters that cannot be observed an

gaining an insight to people’s experiences in particular scenarios. According to T

and Bogdan (1984, p. 79), no other method “can provide the detailed understan

comes from directly observing people and listening to what they have to say at

scene”.

Industry practitioners were purposefully sampled from various states in Austr

and invited to participate in the research.Interviews were conducted at the offices of

interviewees. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim to allo

the nuances in the interview to be apparent in the text.The interviewees’ details were

coded to allow for anonymity,although all interviewees were aware that it might be

possible to identify them from the content of the text. The format of the intervie

kept as consistentas possiblefollowing thethemesassociated with developed

conceptual model.Interviews were kept open using phrases such as “tell me about

or “can you give me an example”. The open nature of the questions allowed for

of interest to be pursued as they arose without introducing bias in the response

were taken during the interview to support the tapes to maintain validity. Each

interviews varied in length from one to two hours.Interviews were open to stimulate

conversation and break down any barriersthat may haveexisted between the

interviewer and interviewee.

Data analysis

The text derived from the interviews was analysed using QSR N6 (which is a ver

NUD*IST and combines the efficientmanagementof Non-numericalUnstructured

Data with powerfulprocessesof Indexingand Theorising)and enabledthe

developmentof themes to be identified.One advantage ofsuch software is thatit

enables additional data sources and journal notes to be incorporated into the an

The development and re-assessment of themes as analysis progresses accords

calls for avoiding confining data to pre-determined sets of categories (Silverman

Kvale (1996,p.204) suggests that ad hoc methods for generating meaning enable

researcher access to “a variety of common-sense approaches to interview text u

interplayof techniquessuch as noting patterns,seeingplausibility,making

comparisons etc.”.

Using NUD*IST enabled the researchers to develop an organic approach to cod

as it enabled triggers or categories of interest in the text to be coded and used

track of emerging and developing ideas (Kvale, 1996).These codings can be modified,

integrated or migrated as the analysis progresses and the generation of reportsusing

Boolean search, facilitates the recognition of conflicts and contradictions. This p

enabled key themes identified in the conceptual model to be explored, which le

model being amended based upon the practitioners’experiences and viewpoints.

ECAM

18,5

452

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

No of respondents Geographic locationExperience in

years

No of alliance

projects (n ¼ 49) WA NSW VIC QLD SA

Type of respondent (Mean) (Median) n (%) (n ¼ 30) (n ¼ 2) (n ¼ 1) (n ¼ 13) (n ¼ 3)

Contractor 27.76 4.5 18 37 11 – – 5 2

Client 29.75 2 20 41 14 1 – 4 1

Design consultant 24.00 3 5 10 3 – – 2 –

Construction lawyer 20.50 25 2 4 1 1 – – –

Alliance facilitator 30.00 17 4 8 1 – 1 2 –

Table II.

Sample demographics

Alliance

contracting

453

years

No of alliance

projects (n ¼ 49) WA NSW VIC QLD SA

Type of respondent (Mean) (Median) n (%) (n ¼ 30) (n ¼ 2) (n ¼ 1) (n ¼ 13) (n ¼ 3)

Contractor 27.76 4.5 18 37 11 – – 5 2

Client 29.75 2 20 41 14 1 – 4 1

Design consultant 24.00 3 5 10 3 – – 2 –

Construction lawyer 20.50 25 2 4 1 1 – – –

Alliance facilitator 30.00 17 4 8 1 – 1 2 –

Table II.

Sample demographics

Alliance

contracting

453

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Alliance relationship building

From the analysis three interdependent themes, in the context of the conceptua

was presented, were identified. These were the ability of parties to establish and

individualrelationships,engendering oftrust,and organizationaldevelopment.While

every effort was made by the researchers to steer participants toward issues ide

the conceptualmodel,therewereinstanceswhen thisdid not happen and other

serendipitous issues emerged. As a result the conceptual model was amended a

Individualrelationships

A detailed analysisof the data indicated thatparticipantsdeemed thealliance

development as a process that was subjected to considerable risks as parties jo

to determine their strategic position and define the project’s scope. On another

relationship developmentprocess wasdeemed to benoveland thus required a

considerable amount planning and investigation,which could be used to identify and

manage the risks. It was something that participants were not use too, albeit in

formalised way.Needless to say,participants had a preference forworking and

forming relationshipswith individualsand organizationswith which they had

favourable experience.Previous experience would reduce risk and provide a more

tangible assessment of their development strategies.Despite the fact that the alliance

development in the conceptual model was somewhat staged,the use of management

games and selection themes could facilitate parties to fast track development; e

them to assess associates within a reduced time frame.

The interviews showed the relationship that alliance partners strove to attain

equivalent to the establishment of respectable personal relationships.For example,the

contractors sampled had an objective of maintaining a position of high regard fr

client.A “relationship test” could determine if parties are able to behave as expe

whether they would be likely to persist with adversarial or “business as usual” p

Participants revealed that they were uncomfortable with the notion of undertak

“relationship test” as itwas subjective and thatfamiliar tangible criteria,under the

auspices of prequalification, were more appropriate. Because of the novelty of t

and unfamiliarity with issues formalising trust,participants were particularly hesitant

about adopting this part of the process.It was also perceived that during this intensive

period of relationship building there was a possibility that parent organization c

neglected.However,to address this issue individual,interand intra organizational

relationships were addressed simultaneously to ensure both strategic and goal

Alliance initiators. Clients identified themselves as the initiators of an alliance

particularly interested to unearth individuals that had people skills and the abili

judge, intervene and build on strengths; identify weaknesses and understand be

With regard to individuals the clients endeavoured to identify people who appea

willing to share and display characteristics of openness.These traits were deemed to

provide clients with evidence that individuals are apposite for an alliance enviro

was suggested that openness during the initial assessment phase could instil fe

integration between parties,and thus enable parties to talk candidly in an environmen

that potentially overcamedisagreementand dispute.Individualcommitmentand

personal investment were identified as being a prerequisite for the developmen

objectives and ultimately alliance success. Openness, honesty, and a willingnes

were perceived a necessity in alliance development. The discourse on openness

ECAM

18,5

454

From the analysis three interdependent themes, in the context of the conceptua

was presented, were identified. These were the ability of parties to establish and

individualrelationships,engendering oftrust,and organizationaldevelopment.While

every effort was made by the researchers to steer participants toward issues ide

the conceptualmodel,therewereinstanceswhen thisdid not happen and other

serendipitous issues emerged. As a result the conceptual model was amended a

Individualrelationships

A detailed analysisof the data indicated thatparticipantsdeemed thealliance

development as a process that was subjected to considerable risks as parties jo

to determine their strategic position and define the project’s scope. On another

relationship developmentprocess wasdeemed to benoveland thus required a

considerable amount planning and investigation,which could be used to identify and

manage the risks. It was something that participants were not use too, albeit in

formalised way.Needless to say,participants had a preference forworking and

forming relationshipswith individualsand organizationswith which they had

favourable experience.Previous experience would reduce risk and provide a more

tangible assessment of their development strategies.Despite the fact that the alliance

development in the conceptual model was somewhat staged,the use of management

games and selection themes could facilitate parties to fast track development; e

them to assess associates within a reduced time frame.

The interviews showed the relationship that alliance partners strove to attain

equivalent to the establishment of respectable personal relationships.For example,the

contractors sampled had an objective of maintaining a position of high regard fr

client.A “relationship test” could determine if parties are able to behave as expe

whether they would be likely to persist with adversarial or “business as usual” p

Participants revealed that they were uncomfortable with the notion of undertak

“relationship test” as itwas subjective and thatfamiliar tangible criteria,under the

auspices of prequalification, were more appropriate. Because of the novelty of t

and unfamiliarity with issues formalising trust,participants were particularly hesitant

about adopting this part of the process.It was also perceived that during this intensive

period of relationship building there was a possibility that parent organization c

neglected.However,to address this issue individual,interand intra organizational

relationships were addressed simultaneously to ensure both strategic and goal

Alliance initiators. Clients identified themselves as the initiators of an alliance

particularly interested to unearth individuals that had people skills and the abili

judge, intervene and build on strengths; identify weaknesses and understand be

With regard to individuals the clients endeavoured to identify people who appea

willing to share and display characteristics of openness.These traits were deemed to

provide clients with evidence that individuals are apposite for an alliance enviro

was suggested that openness during the initial assessment phase could instil fe

integration between parties,and thus enable parties to talk candidly in an environmen

that potentially overcamedisagreementand dispute.Individualcommitmentand

personal investment were identified as being a prerequisite for the developmen

objectives and ultimately alliance success. Openness, honesty, and a willingnes

were perceived a necessity in alliance development. The discourse on openness

ECAM

18,5

454

simultaneously with that of trust by all respondents. Seemingly by acting in an open and

candid way participants felt that trust could be engendered.

The clientrespondentsindicated thatduring a typicalalliancedevelopment

program the group commenced with an open mind to address possible integration

issues. For example, how the non-owner participants were going to overcome technical,

community and environmentalissues;or how the alliance was going to dealwith

safety? Other issues concerned the on-going management of relationships within the

project team,between the governing body and the project lead team or within the

projectteam itself.Somerespondentsused rationalchecksto supplementless

subjective measures of credibility.Examples of rationalchecks included calling for

Curriculum Vitae,financialstatementsor referencesfrom previousclients.A

preparedness to provide open books was described as an act of credibility.

Non-owner participants indicated that individual relationship developed over time.

The alliancedevelopmentperiod enabled theparticipantsto enterthe alliance

implementphase as committed partners.This could enable the projectto operate

effectively from the earliest opportunity. There was recognition that individuals within

the alliance would be at different levels of development and strategies could be put in

place to intervene and consequently redress any imbalance,if it existed.The goals

developed in a relationship development workshop can be directed to further develop

teams to challenge their own norms and values.

Engendering of trust

Trust was an important concept raised by respondents.Trust enabled contractors to

differentiate themselves or be selected in a different way from the more traditional,

business as usual price-alone selection.Early development of trust was considered to

engender harmony and respect within a project team. The conceptual model in Figure 1

implicitly aims to deconstruct formality of the relationship development process by

using a mixture ofactivities and scenarios to assess participants’reactions.For

example,the extentto which empathetic behaviours is displayed in a particular

circumstance. Contextualising this, several respondents suggested that it was easy for

them to respond from the “heart” in the alliance development environment as mutual

understandingwas often a consequenceof their past experience.Invariably

respondentsenteredan alliancedevelopmentwith “openminds” and often

proceeded with the underlying assumption that their trust would be reciprocated.

It was indicated that trust was often assessed in parallelwith commitment.For

example,commitment to others through resource allocation,generated attitudes that

reduced risk for all parties. It enabled a client to have a more detailed understanding of

the process of the project they were generating than would ordinarily happen. Because

a NOP team is assessed as a collective entity it is important that they are able to

demonstrate a bond that can translate into a team that is prepared to integrate with

other participants. Testing bonds, in this instance, with technical scenarios would form

part of the relationship development workshop. From the respondent’s perspective an

integrated team should be the goal of the relationship development workshop. In effect

become a team working together as if part of the same organization, solving problems

and being prepared to confront hard to solve issues.

All respondents indicated that they perceived increasing levels of trust throughout

the alliance developmentduration.When asked ifthey had any specialway of

Alliance

contracting

455

candid way participants felt that trust could be engendered.

The clientrespondentsindicated thatduring a typicalalliancedevelopment

program the group commenced with an open mind to address possible integration

issues. For example, how the non-owner participants were going to overcome technical,

community and environmentalissues;or how the alliance was going to dealwith

safety? Other issues concerned the on-going management of relationships within the

project team,between the governing body and the project lead team or within the

projectteam itself.Somerespondentsused rationalchecksto supplementless

subjective measures of credibility.Examples of rationalchecks included calling for

Curriculum Vitae,financialstatementsor referencesfrom previousclients.A

preparedness to provide open books was described as an act of credibility.

Non-owner participants indicated that individual relationship developed over time.

The alliancedevelopmentperiod enabled theparticipantsto enterthe alliance

implementphase as committed partners.This could enable the projectto operate

effectively from the earliest opportunity. There was recognition that individuals within

the alliance would be at different levels of development and strategies could be put in

place to intervene and consequently redress any imbalance,if it existed.The goals

developed in a relationship development workshop can be directed to further develop

teams to challenge their own norms and values.

Engendering of trust

Trust was an important concept raised by respondents.Trust enabled contractors to

differentiate themselves or be selected in a different way from the more traditional,

business as usual price-alone selection.Early development of trust was considered to

engender harmony and respect within a project team. The conceptual model in Figure 1

implicitly aims to deconstruct formality of the relationship development process by

using a mixture ofactivities and scenarios to assess participants’reactions.For

example,the extentto which empathetic behaviours is displayed in a particular

circumstance. Contextualising this, several respondents suggested that it was easy for

them to respond from the “heart” in the alliance development environment as mutual

understandingwas often a consequenceof their past experience.Invariably

respondentsenteredan alliancedevelopmentwith “openminds” and often

proceeded with the underlying assumption that their trust would be reciprocated.

It was indicated that trust was often assessed in parallelwith commitment.For

example,commitment to others through resource allocation,generated attitudes that

reduced risk for all parties. It enabled a client to have a more detailed understanding of

the process of the project they were generating than would ordinarily happen. Because

a NOP team is assessed as a collective entity it is important that they are able to

demonstrate a bond that can translate into a team that is prepared to integrate with

other participants. Testing bonds, in this instance, with technical scenarios would form

part of the relationship development workshop. From the respondent’s perspective an

integrated team should be the goal of the relationship development workshop. In effect

become a team working together as if part of the same organization, solving problems

and being prepared to confront hard to solve issues.

All respondents indicated that they perceived increasing levels of trust throughout

the alliance developmentduration.When asked ifthey had any specialway of

Alliance

contracting

455

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 18

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.