Higher Education: Week 1 Notes on Formulating and Clarifying Research

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/02

|12

|5468

|26

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This document provides comprehensive notes extracted from various sources, focusing on formulating and clarifying research. It defines research, emphasizing its systematic and rigorous nature. The notes cover quantitative research, its philosophical underpinnings in the postpositivist worldview, and its characteristics. It explains the importance of developing a coherent research topic, including the four Ps (people, problems, programmes, phenomena) and considerations for topic selection, such as interest, magnitude, measurement of concepts, expertise, relevance, data availability, and ethical issues. The document also includes a detailed explanation of the research process, emphasizing its systematic, valid, and empirical nature, and the importance of critical scrutiny. The notes aim to provide a solid foundation for understanding research methodologies and the process of formulating research questions within the context of higher education.

1

WEEK 1 NOTES

FORMULATING AND CLARIFYING RESEARCH

The notes are mostly extracted (copy paste) from the references provided at the end of this document.

An Introduction to Research

Research defined

The word research is composed of two syllables, re and search. The dictionary defines the

former as a prefix meaning again, anew or over again and the latter as a verb meaning to

examine closely and carefully, to test and try, or to probe. Together they form a noun describing

a careful, systematic, patient study and investigation in some field of knowledge, undertaken

to establish facts or principles (Grinnell 1993: 4).

As such, research does not necessarily mean conducting a study that has never been done

before.

Grinnell further adds: ‘research is a structured inquiry that utilises acceptable scientific

methodology to solve problems and creates new knowledge that is generally applicable’ (1993:

4). Lundberg (1942) draws a parallel between the social research process, which is considered

scientific, and the process that we use in our daily lives. According to him:

Scientific methods consist of systematic observation, classification and interpretation of data.

Now, obviously, this process is one in which nearly all people engage in the course of their

daily lives. The main difference between our day-to-day generalisations and the conclusions

usually recognised as scientific method lies in the degree of formality, rigorousness,

verifiability and general validity of the latter (Lundberg 1942: 5).

Burns (1997: 2) defines research as ‘a systematic investigation to find answers to a problem’.

According to Kerlinger (1986: 10), ‘scientific research is a systematic, controlled empirical

and critical investigation of propositions about the presumed relationships about various

phenomena’. Bulmer (1977: 5) states: ‘Nevertheless sociological research, as research, is

primarily committed to establishing systematic, reliable and valid knowledge about the social

world.’

To sum up, a research (1) is undertaken within a framework of a set of philosophies; (2) uses

procedures, methods and techniques that have been tested for their validity and reliability and;

(3) is designed to be unbiased and objective.

Characteristics and requirements of the research process

To qualify as research in social sciences, its process must have these characteristics and

requirements:

1. Rigorous

WEEK 1 NOTES

FORMULATING AND CLARIFYING RESEARCH

The notes are mostly extracted (copy paste) from the references provided at the end of this document.

An Introduction to Research

Research defined

The word research is composed of two syllables, re and search. The dictionary defines the

former as a prefix meaning again, anew or over again and the latter as a verb meaning to

examine closely and carefully, to test and try, or to probe. Together they form a noun describing

a careful, systematic, patient study and investigation in some field of knowledge, undertaken

to establish facts or principles (Grinnell 1993: 4).

As such, research does not necessarily mean conducting a study that has never been done

before.

Grinnell further adds: ‘research is a structured inquiry that utilises acceptable scientific

methodology to solve problems and creates new knowledge that is generally applicable’ (1993:

4). Lundberg (1942) draws a parallel between the social research process, which is considered

scientific, and the process that we use in our daily lives. According to him:

Scientific methods consist of systematic observation, classification and interpretation of data.

Now, obviously, this process is one in which nearly all people engage in the course of their

daily lives. The main difference between our day-to-day generalisations and the conclusions

usually recognised as scientific method lies in the degree of formality, rigorousness,

verifiability and general validity of the latter (Lundberg 1942: 5).

Burns (1997: 2) defines research as ‘a systematic investigation to find answers to a problem’.

According to Kerlinger (1986: 10), ‘scientific research is a systematic, controlled empirical

and critical investigation of propositions about the presumed relationships about various

phenomena’. Bulmer (1977: 5) states: ‘Nevertheless sociological research, as research, is

primarily committed to establishing systematic, reliable and valid knowledge about the social

world.’

To sum up, a research (1) is undertaken within a framework of a set of philosophies; (2) uses

procedures, methods and techniques that have been tested for their validity and reliability and;

(3) is designed to be unbiased and objective.

Characteristics and requirements of the research process

To qualify as research in social sciences, its process must have these characteristics and

requirements:

1. Rigorous

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

You must be scrupulous in ensuring that the procedures followed to find answers to

questions are relevant, appropriate and justified. The degree of rigour varies markedly

within the social sciences.

2. Systematic

This implies that the procedures adopted to undertake an investigation follow a certain

logical sequence. The different steps cannot be taken in a haphazard way. Some

procedures must follow others.

3. Valid and verifiable

This concept implies that whatever you conclude on the basis of your findings is correct

and can be verified by you and others.

4. Empirical

This means that any conclusions drawn are based upon hard evidence gathered from

information collected from real-life experiences or observations.

5. Critical

Critical scrutiny of the procedures used and the methods employed is crucial to a

research enquiry. The process of investigation must be foolproof and free from any

drawbacks. The process adopted and the procedures used must be able to withstand

critical scrutiny.

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research is an approach for testing objective theories by examining the

relationship among variables. These variables, in turn, can be measured, typically on

instruments, so that numbered data can be analyzed using statistical procedures. Those who

engage in this form of inquiry have assumptions about testing theories deductively, building in

protections against bias, controlling for alternative or counterfactual explanations, and being

able to generalize and replicate the findings.

The philosophical underpinning of quantitative research is the Postpositivist Worldview. The

postpositivist assumptions have represented the traditional form of research, and these

assumptions hold true more for quantitative research than qualitative research. This worldview

is sometimes called the scientific method, or doing science research. It is also called

positivist/postpositivist research, empirical science, and postpositivism. This last term is called

postpositivism because it represents the thinking after positivism, challenging the traditional

notion of the absolute truth of knowledge (Phillips & Burbules, 2000) and recognizing that we

cannot be absolutely positive about our claims of knowledge when studying the behavior and

actions of humans. The postpositivist tradition comes from 19th-century writers, such as

Comte, Mill, Durkheim, Newton, and Locke (Smith, 1983) and more recently from writers

such as Phillips and Burbules (2000).

Postpositivists hold a deterministic philosophy in which causes (probably) determine effects or

outcomes. Thus, the problems studied by postpositivists reflect the need to identify and assess

the causes that influence outcomes, such as those found in experiments. It is also reductionistic

in that the intent is to reduce the ideas into a small, discrete set to test, such as the variables that

You must be scrupulous in ensuring that the procedures followed to find answers to

questions are relevant, appropriate and justified. The degree of rigour varies markedly

within the social sciences.

2. Systematic

This implies that the procedures adopted to undertake an investigation follow a certain

logical sequence. The different steps cannot be taken in a haphazard way. Some

procedures must follow others.

3. Valid and verifiable

This concept implies that whatever you conclude on the basis of your findings is correct

and can be verified by you and others.

4. Empirical

This means that any conclusions drawn are based upon hard evidence gathered from

information collected from real-life experiences or observations.

5. Critical

Critical scrutiny of the procedures used and the methods employed is crucial to a

research enquiry. The process of investigation must be foolproof and free from any

drawbacks. The process adopted and the procedures used must be able to withstand

critical scrutiny.

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research is an approach for testing objective theories by examining the

relationship among variables. These variables, in turn, can be measured, typically on

instruments, so that numbered data can be analyzed using statistical procedures. Those who

engage in this form of inquiry have assumptions about testing theories deductively, building in

protections against bias, controlling for alternative or counterfactual explanations, and being

able to generalize and replicate the findings.

The philosophical underpinning of quantitative research is the Postpositivist Worldview. The

postpositivist assumptions have represented the traditional form of research, and these

assumptions hold true more for quantitative research than qualitative research. This worldview

is sometimes called the scientific method, or doing science research. It is also called

positivist/postpositivist research, empirical science, and postpositivism. This last term is called

postpositivism because it represents the thinking after positivism, challenging the traditional

notion of the absolute truth of knowledge (Phillips & Burbules, 2000) and recognizing that we

cannot be absolutely positive about our claims of knowledge when studying the behavior and

actions of humans. The postpositivist tradition comes from 19th-century writers, such as

Comte, Mill, Durkheim, Newton, and Locke (Smith, 1983) and more recently from writers

such as Phillips and Burbules (2000).

Postpositivists hold a deterministic philosophy in which causes (probably) determine effects or

outcomes. Thus, the problems studied by postpositivists reflect the need to identify and assess

the causes that influence outcomes, such as those found in experiments. It is also reductionistic

in that the intent is to reduce the ideas into a small, discrete set to test, such as the variables that

3

comprise hypotheses and research questions. The knowledge that develops through a

postpositivist lens is based on careful observation and measurement of the

objective reality that exists “out there” in the world. Thus, developing numeric measures of

observations and studying the behavior of individuals becomes paramount for a

postpositivist. Finally, there are laws or theories that govern the world, and these need to be

tested or verified and refined so that we can understand the world. Thus, in the scientific

method—the accepted approach to research by postpositivists—a researcher begins with a

theory, collects data that either supports or refutes the theory, and then makes necessary

revisions and conducts additional tests.

In reading Phillips and Burbules (2000), you can gain a sense of the key assumptions of this

position, such as the following:

1. Knowledge is conjectural (and antifoundational)—absolute truth can never be found.

Thus, evidence established in research is always imperfect and fallible. It is for this

reason that researchers state that they do not prove a hypothesis; instead, they indicate

a failure to reject the hypothesis.

2. Research is the process of making claims and then refining or abandoning some of

them for other claims more strongly warranted. Most quantitative research, for

example, starts with the test of a theory.

3. Data, evidence, and rational considerations shape knowledge. In practice, the

researcher collects information on instruments based on measures completed by the

participants or by observations recorded by the researcher.

4. Research seeks to develop relevant, true statements, ones that can serve to explain the

situation of concern or that describe the causal relationships of interest. In quantitative

studies, researchers advance the relationship among variables and pose this in terms

of questions or hypotheses.

5. Being objective is an essential aspect of competent inquiry; researchers must examine

methods and conclusions for bias. For example, standard of validity and reliability are

important in quantitative research.

Developing a Coherent Research Topic

To come up with a research topic, it is crucial that you think of a research problem. As a matter

of fact, the term research topic and research problem is used interchangeably. You must have

a clear idea with regard to what it is that you want to find out about and not what you think you

must find. Reflect on whether it is practical and useful to undertake the study. It is also

important for you to understand that the way you formulate a research problem determines all

the subsequent steps that you have to follow during your research journey.

Most research in the humanities revolves around four Ps: (1) people; (2) problems; (3)

programmes; (4) phenomena. In practice, most research studies are based upon at least a

combination of two Ps. You may select a group of individuals (a group of individuals – or a

comprise hypotheses and research questions. The knowledge that develops through a

postpositivist lens is based on careful observation and measurement of the

objective reality that exists “out there” in the world. Thus, developing numeric measures of

observations and studying the behavior of individuals becomes paramount for a

postpositivist. Finally, there are laws or theories that govern the world, and these need to be

tested or verified and refined so that we can understand the world. Thus, in the scientific

method—the accepted approach to research by postpositivists—a researcher begins with a

theory, collects data that either supports or refutes the theory, and then makes necessary

revisions and conducts additional tests.

In reading Phillips and Burbules (2000), you can gain a sense of the key assumptions of this

position, such as the following:

1. Knowledge is conjectural (and antifoundational)—absolute truth can never be found.

Thus, evidence established in research is always imperfect and fallible. It is for this

reason that researchers state that they do not prove a hypothesis; instead, they indicate

a failure to reject the hypothesis.

2. Research is the process of making claims and then refining or abandoning some of

them for other claims more strongly warranted. Most quantitative research, for

example, starts with the test of a theory.

3. Data, evidence, and rational considerations shape knowledge. In practice, the

researcher collects information on instruments based on measures completed by the

participants or by observations recorded by the researcher.

4. Research seeks to develop relevant, true statements, ones that can serve to explain the

situation of concern or that describe the causal relationships of interest. In quantitative

studies, researchers advance the relationship among variables and pose this in terms

of questions or hypotheses.

5. Being objective is an essential aspect of competent inquiry; researchers must examine

methods and conclusions for bias. For example, standard of validity and reliability are

important in quantitative research.

Developing a Coherent Research Topic

To come up with a research topic, it is crucial that you think of a research problem. As a matter

of fact, the term research topic and research problem is used interchangeably. You must have

a clear idea with regard to what it is that you want to find out about and not what you think you

must find. Reflect on whether it is practical and useful to undertake the study. It is also

important for you to understand that the way you formulate a research problem determines all

the subsequent steps that you have to follow during your research journey.

Most research in the humanities revolves around four Ps: (1) people; (2) problems; (3)

programmes; (4) phenomena. In practice, most research studies are based upon at least a

combination of two Ps. You may select a group of individuals (a group of individuals – or a

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

community as such – ‘people’), to examine the existence of certain issues or problems relating

to their lives, to ascertain their attitude towards an issue (‘problem’), to establish the existence

of a regularity (‘phenomenon’) or to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention

(‘programme’). Your focus may be the study of an issue, an association or a phenomenon per

se; for example, the relationship between unemployment and street crime, smoking and cancer,

or fertility and mortality, which is done on the basis of information collected from individuals,

groups, communities or organisations. The emphasis in these studies is on exploring,

discovering or establishing associations or causation. Similarly, you can study different aspects

of a programme: its effectiveness, its structure, the need for it, consumers’ satisfaction with it,

and so on. In order to ascertain these you collect information from people.

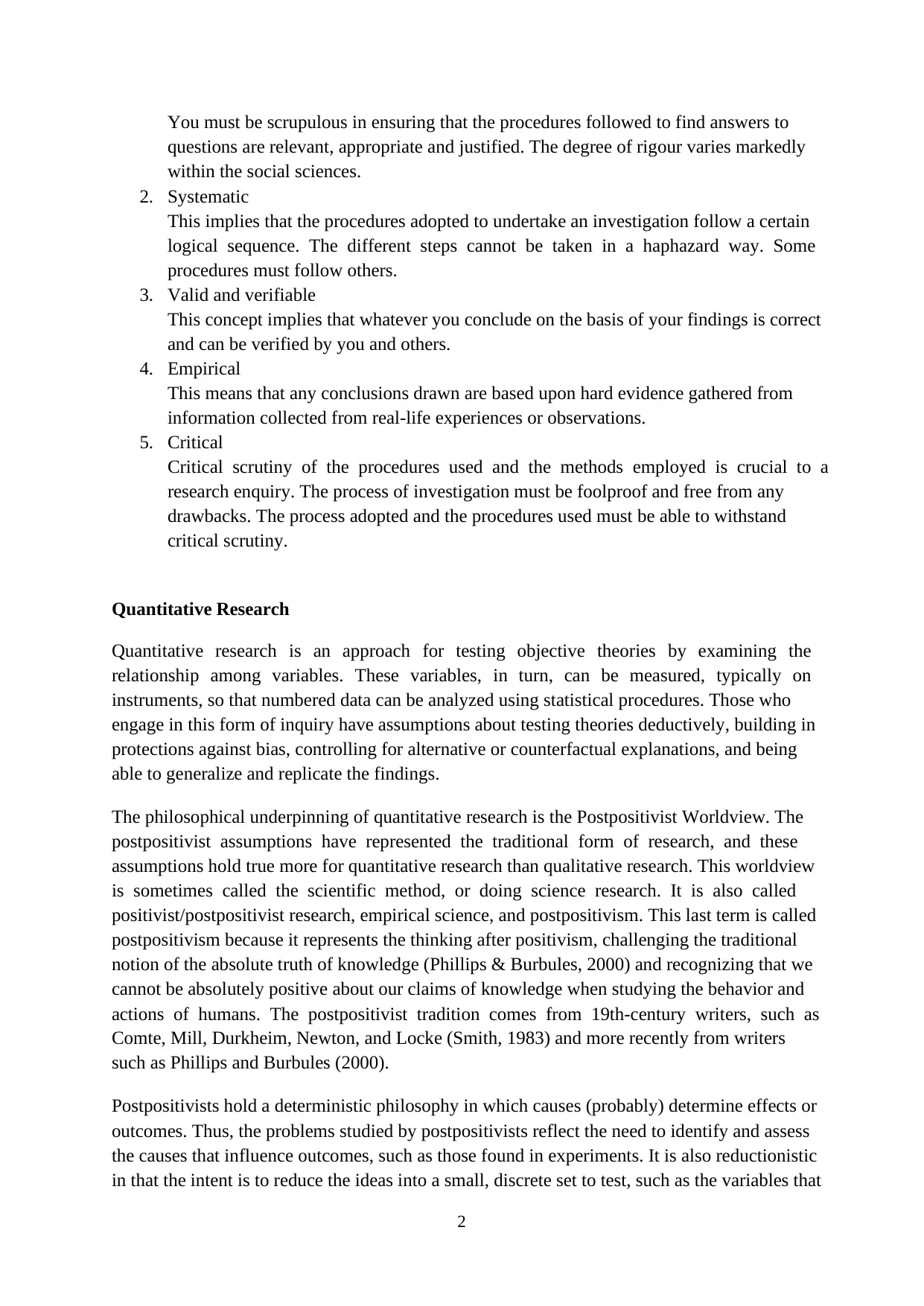

Every research study has two aspects: the people provide you with the ‘study population’,

whereas the other three Ps furnish the ‘subject areas’. Your study population – individuals,

groups and communities – is the people from whom the information is collected. Your subject

area is a problem, programme or phenomenon about which the information is collected. This

is outlined further in Table 1, which shows the aspects of a research problem.

Table 1

Examine your own academic discipline in the context of the four Ps in order to identify

anything that looks interesting. For example, in education there are several issues: students’

satisfaction with a teacher, attributes of a good teacher, the impact of the home environment

on the educational achievement of students, and the supervisory needs of postgraduate students

in higher education. Any other academic or occupational field can similarly be dissected into

subfields and examined for a potential research problem. Most fields lend themselves to the

above categorisation even though specific problems and programmes vary markedly from field

to field.

In addition, there are a number of considerations to keep in mind which will help to ensure that

your study will be manageable and that you remain motivated. These considerations are:

1. Interest

Interest should be the most important consideration in selecting a research problem. A

research endeavour is usually time consuming, and involves hard work and possibly

unforeseen problems. If you select a topic which does not greatly interest you, it could

community as such – ‘people’), to examine the existence of certain issues or problems relating

to their lives, to ascertain their attitude towards an issue (‘problem’), to establish the existence

of a regularity (‘phenomenon’) or to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention

(‘programme’). Your focus may be the study of an issue, an association or a phenomenon per

se; for example, the relationship between unemployment and street crime, smoking and cancer,

or fertility and mortality, which is done on the basis of information collected from individuals,

groups, communities or organisations. The emphasis in these studies is on exploring,

discovering or establishing associations or causation. Similarly, you can study different aspects

of a programme: its effectiveness, its structure, the need for it, consumers’ satisfaction with it,

and so on. In order to ascertain these you collect information from people.

Every research study has two aspects: the people provide you with the ‘study population’,

whereas the other three Ps furnish the ‘subject areas’. Your study population – individuals,

groups and communities – is the people from whom the information is collected. Your subject

area is a problem, programme or phenomenon about which the information is collected. This

is outlined further in Table 1, which shows the aspects of a research problem.

Table 1

Examine your own academic discipline in the context of the four Ps in order to identify

anything that looks interesting. For example, in education there are several issues: students’

satisfaction with a teacher, attributes of a good teacher, the impact of the home environment

on the educational achievement of students, and the supervisory needs of postgraduate students

in higher education. Any other academic or occupational field can similarly be dissected into

subfields and examined for a potential research problem. Most fields lend themselves to the

above categorisation even though specific problems and programmes vary markedly from field

to field.

In addition, there are a number of considerations to keep in mind which will help to ensure that

your study will be manageable and that you remain motivated. These considerations are:

1. Interest

Interest should be the most important consideration in selecting a research problem. A

research endeavour is usually time consuming, and involves hard work and possibly

unforeseen problems. If you select a topic which does not greatly interest you, it could

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

become extremely difficult to sustain the required motivation and put in enough time

and energy to complete it.

2. Magnitude

You should have sufficient knowledge about the research process to be able to visualise

the work involved in completing the proposed study. Narrow the topic down to

something manageable, specific and clear. It is extremely important to select a topic

that you can manage within the time and with the resources at your disposal. Even if

you are undertaking a descriptive study, you need to consider its magnitude carefully.

3. Measurement of concepts

Make sure you are clear about its indicators and their measurement. For example, if

you plan to measure the effectiveness of a health promotion programme, you must be

clear as to what determines effectiveness and how it will be measured. Do not use

concepts in your research problem that you are not sure how to measure. This does not

mean you cannot develop a measurement procedure as the study progresses. While

most of the developmental work will be done during your study, it is imperative that

you are reasonably clear about the measurement of these concepts at this stage.

4. Level of expertise

Make sure you have an adequate level of expertise for the task you are proposing.

Allow for the fact that you will learn during the study and may receive help from your

research supervisor and others, but remember that you need to do most of the work

yourself.

5. Relevance

Select a topic that is of relevance to you as a professional. Ensure that your study adds

to the existing body of knowledge, bridges current gaps or is useful in policy

formulation. This will help you to sustain interest in the study.

6. Availability of data

If your topic entails collection of information from secondary sources (office records,

client records, census or other already-published reports, etc.) make sure that this data

is available and in the format you want before finalising your topic.

7. Ethical issues

Another important consideration in formulating a research problem is the ethical issues

involved. In the course of conducting a research study, the study population may be

adversely affected by some of the questions (directly or indirectly); deprived of an

intervention; expected to share sensitive and private information; or expected to be

simply experimental ‘guinea pigs’. How ethical issues can affect the study population

and how ethical problems can be overcome should be thoroughly examined at the

problem-formulation stage.

To further refine your research topic, you can go through the following steps:

Step 1 Identify a broad field or subject area of interest to you.

Ask yourself, ‘What is it that really interests me as a professional?’ In the author’s opinion, it

is a good idea to think about the field in which you would like to work after graduation. This

will help you to find an interesting topic, and one which may be of use to you in the future. For

example, if you are a social work student, inclined to work in the area of youth welfare, refugees

become extremely difficult to sustain the required motivation and put in enough time

and energy to complete it.

2. Magnitude

You should have sufficient knowledge about the research process to be able to visualise

the work involved in completing the proposed study. Narrow the topic down to

something manageable, specific and clear. It is extremely important to select a topic

that you can manage within the time and with the resources at your disposal. Even if

you are undertaking a descriptive study, you need to consider its magnitude carefully.

3. Measurement of concepts

Make sure you are clear about its indicators and their measurement. For example, if

you plan to measure the effectiveness of a health promotion programme, you must be

clear as to what determines effectiveness and how it will be measured. Do not use

concepts in your research problem that you are not sure how to measure. This does not

mean you cannot develop a measurement procedure as the study progresses. While

most of the developmental work will be done during your study, it is imperative that

you are reasonably clear about the measurement of these concepts at this stage.

4. Level of expertise

Make sure you have an adequate level of expertise for the task you are proposing.

Allow for the fact that you will learn during the study and may receive help from your

research supervisor and others, but remember that you need to do most of the work

yourself.

5. Relevance

Select a topic that is of relevance to you as a professional. Ensure that your study adds

to the existing body of knowledge, bridges current gaps or is useful in policy

formulation. This will help you to sustain interest in the study.

6. Availability of data

If your topic entails collection of information from secondary sources (office records,

client records, census or other already-published reports, etc.) make sure that this data

is available and in the format you want before finalising your topic.

7. Ethical issues

Another important consideration in formulating a research problem is the ethical issues

involved. In the course of conducting a research study, the study population may be

adversely affected by some of the questions (directly or indirectly); deprived of an

intervention; expected to share sensitive and private information; or expected to be

simply experimental ‘guinea pigs’. How ethical issues can affect the study population

and how ethical problems can be overcome should be thoroughly examined at the

problem-formulation stage.

To further refine your research topic, you can go through the following steps:

Step 1 Identify a broad field or subject area of interest to you.

Ask yourself, ‘What is it that really interests me as a professional?’ In the author’s opinion, it

is a good idea to think about the field in which you would like to work after graduation. This

will help you to find an interesting topic, and one which may be of use to you in the future. For

example, if you are a social work student, inclined to work in the area of youth welfare, refugees

6

or domestic violence after graduation, you might take to research in one of these areas. Or if

you are studying marketing you might be interested in researching consumer behaviour. Or, as

a student of public health, intending to work with patients who have HIV/AIDS, you might like

to conduct research on a subject area relating to HIV/AIDS. As far as the research journey

goes, these are the broad research areas. It is imperative that you identify one of interest to you

before undertaking your research journey.

Step 2 Dissect the broad area into subareas.

At the onset, you will realise that all the broad areas mentioned above – youth welfare, refugees,

domestic violence, consumer behaviour and HIV/AIDS – have many aspects. Similarly, you

can select any subject area from other fields such as community health or consumer research

and go through this dissection process. In preparing this list of subareas you should also consult

others who have some knowledge of the area and the literature in your subject area. Once you

have developed an exhaustive list of the subareas from various sources, you proceed to the next

stage where you select what will become the basis of your enquiry.

Step 3 Select what is of most interest to you.

It is neither advisable nor feasible to study all subareas. Out of this list, select issues or subareas

about which you are passionate. This is because your interest should be the most important

determinant for selection, even though there are other considerations which have been

discussed in the previous section, ‘Considerations in selecting a research problem’. One way

to decide what interests you most is to start with the process of elimination. Go through your

list and delete all those subareas in which you are not very interested. You will find that towards

the end of this process, it will become very difficult for you to delete anything further. You

need to continue until you are left with something that is manageable considering the time

available to you, your level of expertise and other resources needed to undertake the study.

Once you are confident that you have selected an issue you are passionate about and can

manage, you are ready to go to the next step.

Step 4 Raise research questions.

At this step ask yourself, ‘What is it that I want to find out about in this subarea?’ Make a list

of whatever questions come to your mind relating to your chosen subarea and if you think there

are too many to be manageable, go through the process of elimination, as you did in Step 3.

Step 5 Formulate objectives.

Both your main objectives and your subobjectives now need to be formulated, which grow out

of your research questions. The main difference between objectives and research questions is

the way in which they are written. Research questions are obviously that – questions.

Objectives transform these questions into behavioural aims by using action-oriented words

such as ‘to find out’, ‘to determine’, ‘to ascertain’ and ‘to examine’. Some researchers prefer

to reverse the process; that is, they start from objectives and formulate research questions from

them. Some researchers are satisfied only with research questions, and do not formulate

objectives at all. If you prefer to have only research questions or only objectives, this is fine,

but keep in mind the requirements of your institution for research proposals. For guidance on

formulating objectives, see the later section.

or domestic violence after graduation, you might take to research in one of these areas. Or if

you are studying marketing you might be interested in researching consumer behaviour. Or, as

a student of public health, intending to work with patients who have HIV/AIDS, you might like

to conduct research on a subject area relating to HIV/AIDS. As far as the research journey

goes, these are the broad research areas. It is imperative that you identify one of interest to you

before undertaking your research journey.

Step 2 Dissect the broad area into subareas.

At the onset, you will realise that all the broad areas mentioned above – youth welfare, refugees,

domestic violence, consumer behaviour and HIV/AIDS – have many aspects. Similarly, you

can select any subject area from other fields such as community health or consumer research

and go through this dissection process. In preparing this list of subareas you should also consult

others who have some knowledge of the area and the literature in your subject area. Once you

have developed an exhaustive list of the subareas from various sources, you proceed to the next

stage where you select what will become the basis of your enquiry.

Step 3 Select what is of most interest to you.

It is neither advisable nor feasible to study all subareas. Out of this list, select issues or subareas

about which you are passionate. This is because your interest should be the most important

determinant for selection, even though there are other considerations which have been

discussed in the previous section, ‘Considerations in selecting a research problem’. One way

to decide what interests you most is to start with the process of elimination. Go through your

list and delete all those subareas in which you are not very interested. You will find that towards

the end of this process, it will become very difficult for you to delete anything further. You

need to continue until you are left with something that is manageable considering the time

available to you, your level of expertise and other resources needed to undertake the study.

Once you are confident that you have selected an issue you are passionate about and can

manage, you are ready to go to the next step.

Step 4 Raise research questions.

At this step ask yourself, ‘What is it that I want to find out about in this subarea?’ Make a list

of whatever questions come to your mind relating to your chosen subarea and if you think there

are too many to be manageable, go through the process of elimination, as you did in Step 3.

Step 5 Formulate objectives.

Both your main objectives and your subobjectives now need to be formulated, which grow out

of your research questions. The main difference between objectives and research questions is

the way in which they are written. Research questions are obviously that – questions.

Objectives transform these questions into behavioural aims by using action-oriented words

such as ‘to find out’, ‘to determine’, ‘to ascertain’ and ‘to examine’. Some researchers prefer

to reverse the process; that is, they start from objectives and formulate research questions from

them. Some researchers are satisfied only with research questions, and do not formulate

objectives at all. If you prefer to have only research questions or only objectives, this is fine,

but keep in mind the requirements of your institution for research proposals. For guidance on

formulating objectives, see the later section.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

Step 6 Assess your objectives.

Now examine your objectives to ascertain the feasibility of achieving them through your

research endeavour. Consider them in the light of the time, resources (financial and human)

and technical expertise at your disposal.

Step 7 Double-check.

Go back and give final consideration to whether or not you are sufficiently interested in the

study, and have adequate resources to undertake it. Ask yourself, ‘Am I really enthusiastic

about this study?’ and ‘Do I really have enough resources to undertake it?’ Answer these

questions thoughtfully and realistically. If your answer to one of them is ‘no’, reassess your

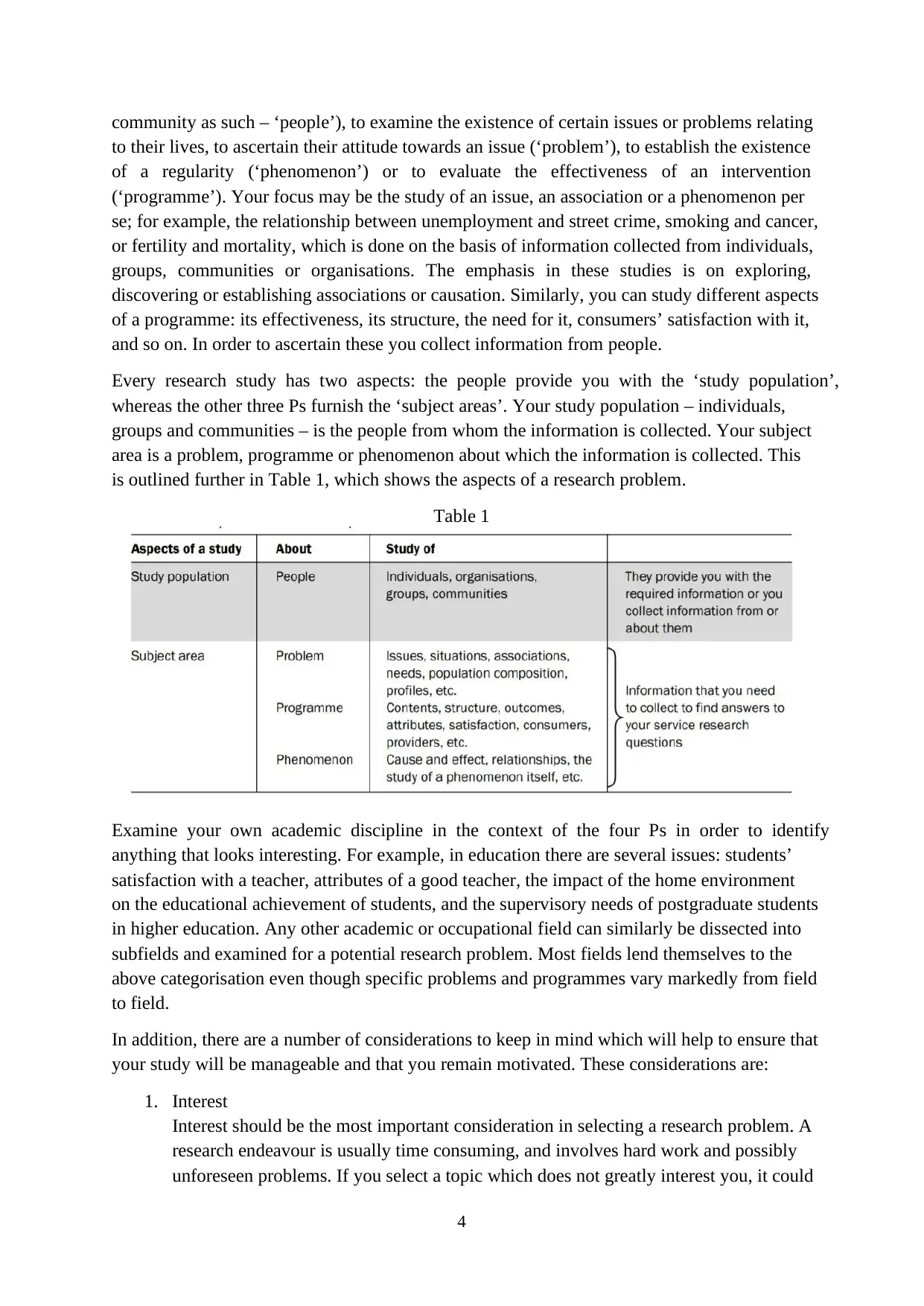

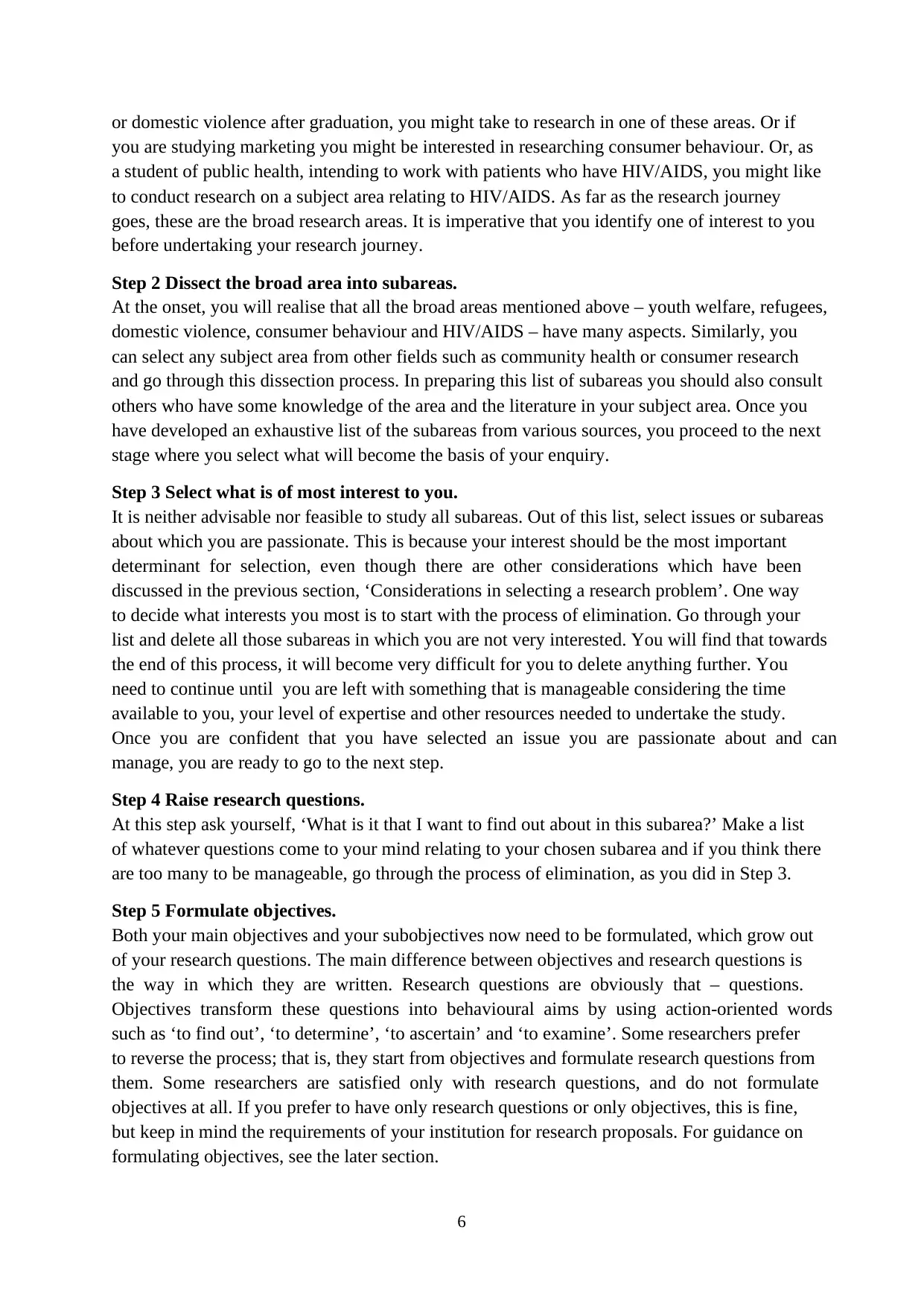

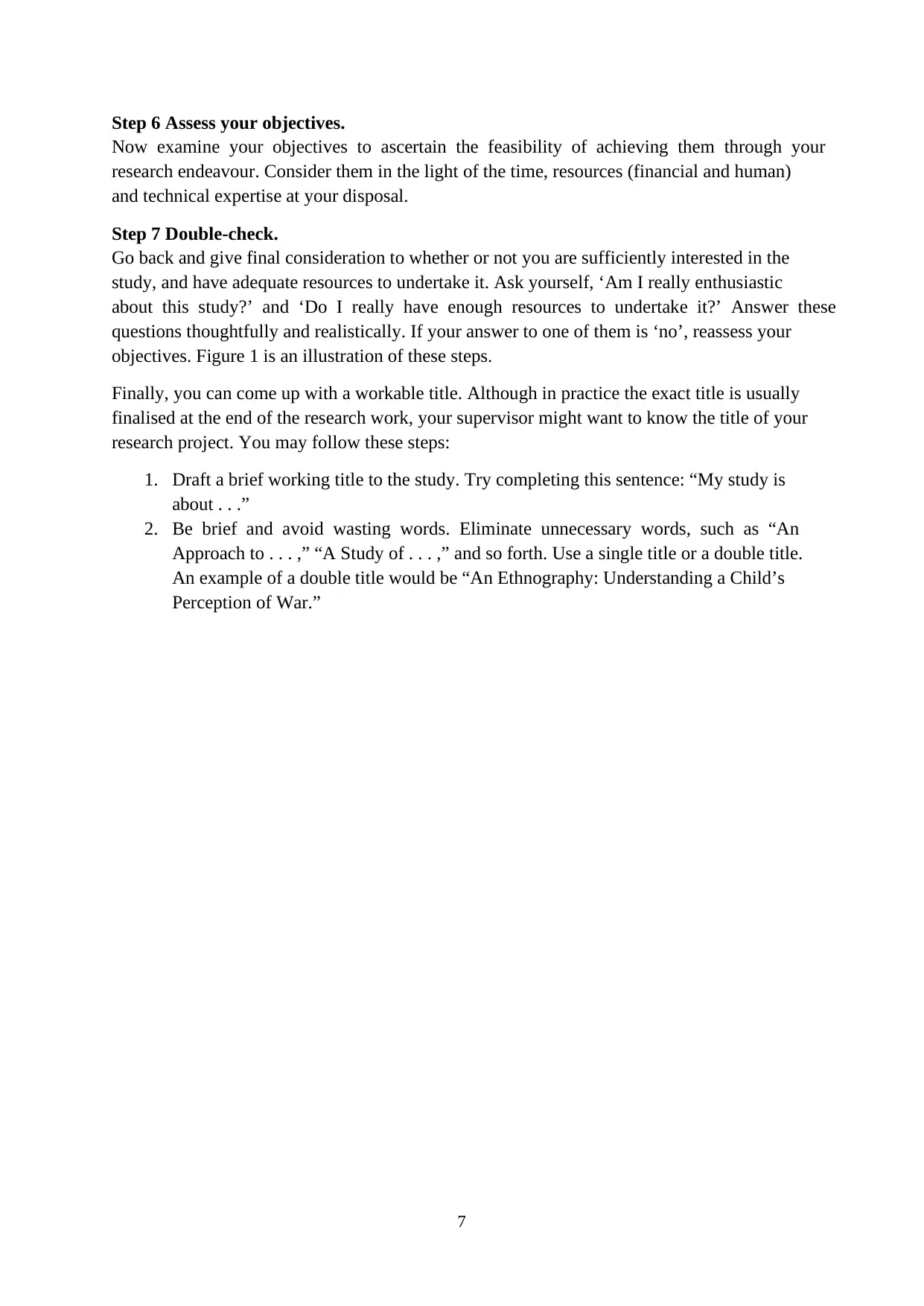

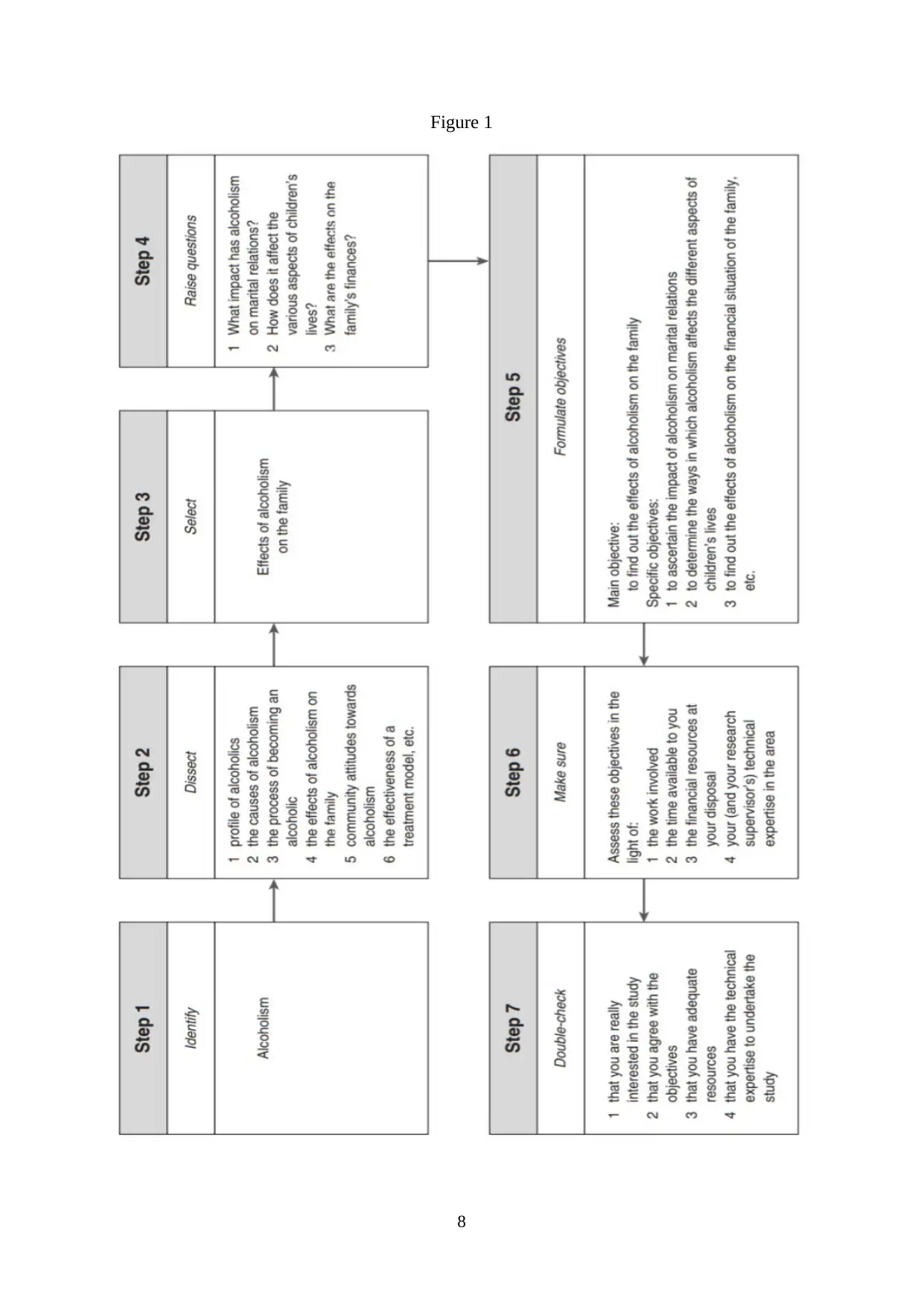

objectives. Figure 1 is an illustration of these steps.

Finally, you can come up with a workable title. Although in practice the exact title is usually

finalised at the end of the research work, your supervisor might want to know the title of your

research project. You may follow these steps:

1. Draft a brief working title to the study. Try completing this sentence: “My study is

about . . .”

2. Be brief and avoid wasting words. Eliminate unnecessary words, such as “An

Approach to . . . ,” “A Study of . . . ,” and so forth. Use a single title or a double title.

An example of a double title would be “An Ethnography: Understanding a Child’s

Perception of War.”

Step 6 Assess your objectives.

Now examine your objectives to ascertain the feasibility of achieving them through your

research endeavour. Consider them in the light of the time, resources (financial and human)

and technical expertise at your disposal.

Step 7 Double-check.

Go back and give final consideration to whether or not you are sufficiently interested in the

study, and have adequate resources to undertake it. Ask yourself, ‘Am I really enthusiastic

about this study?’ and ‘Do I really have enough resources to undertake it?’ Answer these

questions thoughtfully and realistically. If your answer to one of them is ‘no’, reassess your

objectives. Figure 1 is an illustration of these steps.

Finally, you can come up with a workable title. Although in practice the exact title is usually

finalised at the end of the research work, your supervisor might want to know the title of your

research project. You may follow these steps:

1. Draft a brief working title to the study. Try completing this sentence: “My study is

about . . .”

2. Be brief and avoid wasting words. Eliminate unnecessary words, such as “An

Approach to . . . ,” “A Study of . . . ,” and so forth. Use a single title or a double title.

An example of a double title would be “An Ethnography: Understanding a Child’s

Perception of War.”

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

Figure 1

Figure 1

9

Transforming Research Ideas into Research Project

Now that you have your research topic, you can turn it into a research project by highlighting

the background of research, problem statement, research objectives, research questions, and

significance of the study. Still, you need to conduct the literature review first in order to figure

these out.

Background of research includes brief definition of your research topic, a relevant concise

history of your topic, a summary of your problem statement or the main issue related to your

topic, and the main objective of your research.

Problem statement describes and explains the issue(s) that had motivated you to undertake the

research topic. The issues can be anything, including literature gaps.

Research objectives (ROs) is self-explanatory. It usually consists of the main RO followed by

three ROs that describe the main objectives further. Three ROs is the standard number for

Masters and PhD thesis. Also, the research objectives should begin with the word “To”.

Research questions (RQs) is simply the ROs stated in question form. RQs can be more than

three.

Lastly, significance of the study highlights the positive implications of conducting the research.

Below (in blue) is an example of how these points are written; extracted from the lecturer’s

PhD thesis titled (research topic) “Impact of waqf financing on Federal government

expenditure and debt in Malaysia”. Note that for a Masters thesis, the write-up will not have to

be as rigourous.

1.1 Background of the Study

Waqf is a pious endowment in Islam that possesses significant economic potential. Due to religious

and altruistic motives, waqf became the supplier of public goods, mixed public goods, and other

related goods in Islamic history. It then emerged as a supplementary fiscal policy during the

Ayyubid Dynasty. The value of waqf then steadily rose to a third of the Ottoman’s fiscal revenue.

In the context of current economy, the mentioned goods are mainly provided by the government to

which government expenditures are incurred. Essentially, the goods make up the components of

government public expenditure thus rendering waqf unnecessary.

However, burgeoning government expenditure puts a strain on government revenue which

ultimately causes excessive borrowing. Excessive borrowing in turn causes unsustainable debt. This

very issue has always been a major concern for every economy. Debt is only sustainable when

government is able to pay for its current and future debt obligation and is usually assessed by

observing the trend of debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio. A plethora of studies had been

conducted to address unsustainable debt. Suggestions include investing in productive government

expenditure, increase tax, reduce interest rate, and employing mix strategies. Upon learning the role

of waqf as a supplementary fiscal policy in Islamic history, this thesis would want to examine this

in light of current economy, specifically the current Malaysian economy.

Indeed, Çizakça (1998) envisioned that debt can be ultimately reduced should waqf be assigned

to finance certain components of government expenditure. A simulation was specifically done for

Malaysia by Mohd Umar, Shahida, Abdul Ghafar and Zaini (2012) which found that waqf can help

government save more thus enabling the savings to finance debt. Hence the primary aim of this

thesis is to investigate how waqf can finance certain Malaysian federal government expenditures

(pure and mixed public goods as well 2 as other related goods) and analyse the impact of this

particular waqf implementation on Malaysian federal government debt.

Transforming Research Ideas into Research Project

Now that you have your research topic, you can turn it into a research project by highlighting

the background of research, problem statement, research objectives, research questions, and

significance of the study. Still, you need to conduct the literature review first in order to figure

these out.

Background of research includes brief definition of your research topic, a relevant concise

history of your topic, a summary of your problem statement or the main issue related to your

topic, and the main objective of your research.

Problem statement describes and explains the issue(s) that had motivated you to undertake the

research topic. The issues can be anything, including literature gaps.

Research objectives (ROs) is self-explanatory. It usually consists of the main RO followed by

three ROs that describe the main objectives further. Three ROs is the standard number for

Masters and PhD thesis. Also, the research objectives should begin with the word “To”.

Research questions (RQs) is simply the ROs stated in question form. RQs can be more than

three.

Lastly, significance of the study highlights the positive implications of conducting the research.

Below (in blue) is an example of how these points are written; extracted from the lecturer’s

PhD thesis titled (research topic) “Impact of waqf financing on Federal government

expenditure and debt in Malaysia”. Note that for a Masters thesis, the write-up will not have to

be as rigourous.

1.1 Background of the Study

Waqf is a pious endowment in Islam that possesses significant economic potential. Due to religious

and altruistic motives, waqf became the supplier of public goods, mixed public goods, and other

related goods in Islamic history. It then emerged as a supplementary fiscal policy during the

Ayyubid Dynasty. The value of waqf then steadily rose to a third of the Ottoman’s fiscal revenue.

In the context of current economy, the mentioned goods are mainly provided by the government to

which government expenditures are incurred. Essentially, the goods make up the components of

government public expenditure thus rendering waqf unnecessary.

However, burgeoning government expenditure puts a strain on government revenue which

ultimately causes excessive borrowing. Excessive borrowing in turn causes unsustainable debt. This

very issue has always been a major concern for every economy. Debt is only sustainable when

government is able to pay for its current and future debt obligation and is usually assessed by

observing the trend of debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio. A plethora of studies had been

conducted to address unsustainable debt. Suggestions include investing in productive government

expenditure, increase tax, reduce interest rate, and employing mix strategies. Upon learning the role

of waqf as a supplementary fiscal policy in Islamic history, this thesis would want to examine this

in light of current economy, specifically the current Malaysian economy.

Indeed, Çizakça (1998) envisioned that debt can be ultimately reduced should waqf be assigned

to finance certain components of government expenditure. A simulation was specifically done for

Malaysia by Mohd Umar, Shahida, Abdul Ghafar and Zaini (2012) which found that waqf can help

government save more thus enabling the savings to finance debt. Hence the primary aim of this

thesis is to investigate how waqf can finance certain Malaysian federal government expenditures

(pure and mixed public goods as well 2 as other related goods) and analyse the impact of this

particular waqf implementation on Malaysian federal government debt.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

1.2 Problem Statement

The Malaysian federal government debt to GDP ratio is rising and this will bring negative

consequences to the country. Motley (1987), Sutherland (1997), as well as Checherita and Rother

(2010) found evidence that high government debt can cause contractionary effects. Teles and

Mussolini (2014) showed how high debt to GDP ratio can constrain the effects of productive

expenditures on growth in the long term. Kwon, McFarlane, and Robinson (2009) provided strong

evidence that rising public debt can cause inflation in high indebted developing countries. Even the

founder of Keynesian economics, John Maynard Keynes adopted a cautious view towards debt

(Aspromourgos, n.d.). The Malaysian federal government had addressed this problem by

introducing the goods and services tax (GST) and federal government expenditure reduction.

However, the simultaneous tax increase and expenditure decrease have negative consequences on

the Malaysian public welfare (Konzelmann, 2014).

On top of that, the steepest increase in Malaysian federal government debt to GDP ratio

occurred at the same time with the steepest increase in primary deficit. These occurrences were

during the aftermath of the 2008 global economic crisis which roughly suggests that external shocks

affect federal government debt. External shocks can be difficult to predict and may occur now and

then. The primary deficit is also an indication of burgeoning government expenditure. Moreover,

the federal government debt to GDP ratio has crossed the 50% threshold in times where persistent

primary deficit is already occurring. It is the intent of this study to find an effective solution.

Yet solutions stemming from conventional economics school of thought is already saturated. It

is for this very reason that this research chose to look solutions from Islamic 3 economics. Islamic

economics considers waqf, essentially a third sector component that has never been considered

seriously in the public finance literature. Studies that build macroeconomic models to study debt

sustainability very scarcely included the third sector in their modelled economy, inadvertently

dismissing the impact that third sector could have on debt sustainability. This leaves a huge gap in

the literature to which this study attempts to fill.

Meanwhile, studies done on the side of Islamic economics are vastly theoretical on the matter

of waqf, debt sustainability, and public expenditures. Also, studies of waqf in the public finance

field are mostly anachronistic. For instance, Faridi (1983) stated that Islamic economy consist of

three sectors; public, private, and voluntary but did not frame them in light of modern economics.

As a result, framework for waqf in current economies are lacking which pose difficulty to

mathematically calculate the impact of waqf financing public expenditure on debt. Although Mohd

Umar et al. (2012) did demonstrate how waqf can indirectly help the government to finance debt,

the study done was without a theoretical framework. In fact, very few contemporary studies actually

show this link between waqf and debt. This is expected because societies in modern economies

mostly recognise the government as the provider of public goods through government spending. It

is this research’s motivation to fill that gap.

1.3 Research Objectives

This research studies the impact of waqf on Malaysian federal government debt when waqf finances

public goods, mixed public goods, and other related goods. The related goods can also be termed

as social services. Social services include elderly care and other vulnerable groups, flood prevention

projects, river rehabilitation, and others. These goods also make up parts of the federal government

expenditures (Ministry of Finance [MOF] Malaysia, 2010/2011). The federal government allocated

budget to most Malaysian states 4 as waqf to provide for some of these goods. In addition, the

private sector has also collaborated with the State Islamic Religious Councils (SIRCs) to take

similar initiative. The Malaysian community too contributed waqf for the benefit of society.

To build a comprehensive understanding on the matter, this study firstly attempts to understand

the workings of waqf in Malaysia to gather reasons for waqf financing public expenditures. It also

seeks to understand the issues that may arise from that waqf implementation. By studying the issues,

this thesis proceeds to develop a model for waqf financing public expenditure that Malaysia can

adopt. Lastly, this thesis attempts to find out the impact of that waqf application on federal

1.2 Problem Statement

The Malaysian federal government debt to GDP ratio is rising and this will bring negative

consequences to the country. Motley (1987), Sutherland (1997), as well as Checherita and Rother

(2010) found evidence that high government debt can cause contractionary effects. Teles and

Mussolini (2014) showed how high debt to GDP ratio can constrain the effects of productive

expenditures on growth in the long term. Kwon, McFarlane, and Robinson (2009) provided strong

evidence that rising public debt can cause inflation in high indebted developing countries. Even the

founder of Keynesian economics, John Maynard Keynes adopted a cautious view towards debt

(Aspromourgos, n.d.). The Malaysian federal government had addressed this problem by

introducing the goods and services tax (GST) and federal government expenditure reduction.

However, the simultaneous tax increase and expenditure decrease have negative consequences on

the Malaysian public welfare (Konzelmann, 2014).

On top of that, the steepest increase in Malaysian federal government debt to GDP ratio

occurred at the same time with the steepest increase in primary deficit. These occurrences were

during the aftermath of the 2008 global economic crisis which roughly suggests that external shocks

affect federal government debt. External shocks can be difficult to predict and may occur now and

then. The primary deficit is also an indication of burgeoning government expenditure. Moreover,

the federal government debt to GDP ratio has crossed the 50% threshold in times where persistent

primary deficit is already occurring. It is the intent of this study to find an effective solution.

Yet solutions stemming from conventional economics school of thought is already saturated. It

is for this very reason that this research chose to look solutions from Islamic 3 economics. Islamic

economics considers waqf, essentially a third sector component that has never been considered

seriously in the public finance literature. Studies that build macroeconomic models to study debt

sustainability very scarcely included the third sector in their modelled economy, inadvertently

dismissing the impact that third sector could have on debt sustainability. This leaves a huge gap in

the literature to which this study attempts to fill.

Meanwhile, studies done on the side of Islamic economics are vastly theoretical on the matter

of waqf, debt sustainability, and public expenditures. Also, studies of waqf in the public finance

field are mostly anachronistic. For instance, Faridi (1983) stated that Islamic economy consist of

three sectors; public, private, and voluntary but did not frame them in light of modern economics.

As a result, framework for waqf in current economies are lacking which pose difficulty to

mathematically calculate the impact of waqf financing public expenditure on debt. Although Mohd

Umar et al. (2012) did demonstrate how waqf can indirectly help the government to finance debt,

the study done was without a theoretical framework. In fact, very few contemporary studies actually

show this link between waqf and debt. This is expected because societies in modern economies

mostly recognise the government as the provider of public goods through government spending. It

is this research’s motivation to fill that gap.

1.3 Research Objectives

This research studies the impact of waqf on Malaysian federal government debt when waqf finances

public goods, mixed public goods, and other related goods. The related goods can also be termed

as social services. Social services include elderly care and other vulnerable groups, flood prevention

projects, river rehabilitation, and others. These goods also make up parts of the federal government

expenditures (Ministry of Finance [MOF] Malaysia, 2010/2011). The federal government allocated

budget to most Malaysian states 4 as waqf to provide for some of these goods. In addition, the

private sector has also collaborated with the State Islamic Religious Councils (SIRCs) to take

similar initiative. The Malaysian community too contributed waqf for the benefit of society.

To build a comprehensive understanding on the matter, this study firstly attempts to understand

the workings of waqf in Malaysia to gather reasons for waqf financing public expenditures. It also

seeks to understand the issues that may arise from that waqf implementation. By studying the issues,

this thesis proceeds to develop a model for waqf financing public expenditure that Malaysia can

adopt. Lastly, this thesis attempts to find out the impact of that waqf application on federal

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

government debt. It must be duly noted that this research recommends waqf as a supplementary

fiscal strategy and do not dismiss the role of tax and debt altogether. Below are this thesis’s research

objectives (ROs):

I. To explore the extent to which waqf financing Malaysian federal government public

expenditure is doable.

II. To propose a model of waqf financing federal government public expenditure for

Malaysia.

III. To analyse the impact that waqf has on Malaysian federal government debt in the event

that waqf finances Malaysian federal government public expenditure.

1.4 Research Questions

The research questions (RQs) of this study correspond to the ROs. To be specific, RQ1 and RQ 2

corresponds to RO 1, RQ 3 corresponds to RO 2, while RQ 4 corresponds to RO 3. The RQs are

framed as follows:

I. Why waqf financing Malaysian federal government public expenditure is doable?

II. What are the issues that could obstruct the use of waqf to finance Malaysian federal

government public expenditure?

III. How can waqf finance Malaysian federal government public expenditure?

IV. How will waqf impact Malaysian federal government debt in the event that waqf finances

Malaysian federal government public expenditure?

1.5 Significance of the Study

This thesis argues that waqf can be an indirect solution to the Malaysian federal government debt

problem by employing it to finance public expenditure. This thesis shows evidence that this

implementation of waqf can be applied in Malaysia. Further, challenges as well as the way

forward for this implementation of waqf are provided. As alluded in Section 2.0, there is a limited

number of literature that addressed the topic of waqf in the public finance context thus exhibits the

significance of this thesis. There are also positive implications beside from the literature gap. All

of these are summed up as follows:

I. This research made an effort to provide solutions to the Malaysian federal government

debt problem which is in need of urgent and continuous attention.

II. This research identifies the challenges and way forward for this particular implementation

of waqf hence can be used as a reference by persons of authority in Malaysia and

academicians worldwide.

III. This research can also possibly be of use as reference by other countries intending to

mimic this particular implementation of waqf which inadvertently adds on to the waqf

literature.

IV. This research establishes another solution to sustain debt aside from the typical conduct

of fiscal and monetary policy. Since waqf originates from Islamic economics and related

to the third sector economy, then this research has also introduced solutions to

government debt problem from these fields.

V. Following item IV, this research provides evidence on the significance of third sector role

and Islamic economics.

VI. This research contributes to the literature of waqf by helping to extend and argue the

implementation of waqf outside of its traditional uses thus expounding the need of waqf in

modern economy structure.

government debt. It must be duly noted that this research recommends waqf as a supplementary

fiscal strategy and do not dismiss the role of tax and debt altogether. Below are this thesis’s research

objectives (ROs):

I. To explore the extent to which waqf financing Malaysian federal government public

expenditure is doable.

II. To propose a model of waqf financing federal government public expenditure for

Malaysia.

III. To analyse the impact that waqf has on Malaysian federal government debt in the event

that waqf finances Malaysian federal government public expenditure.

1.4 Research Questions

The research questions (RQs) of this study correspond to the ROs. To be specific, RQ1 and RQ 2

corresponds to RO 1, RQ 3 corresponds to RO 2, while RQ 4 corresponds to RO 3. The RQs are

framed as follows:

I. Why waqf financing Malaysian federal government public expenditure is doable?

II. What are the issues that could obstruct the use of waqf to finance Malaysian federal

government public expenditure?

III. How can waqf finance Malaysian federal government public expenditure?

IV. How will waqf impact Malaysian federal government debt in the event that waqf finances

Malaysian federal government public expenditure?

1.5 Significance of the Study

This thesis argues that waqf can be an indirect solution to the Malaysian federal government debt

problem by employing it to finance public expenditure. This thesis shows evidence that this

implementation of waqf can be applied in Malaysia. Further, challenges as well as the way

forward for this implementation of waqf are provided. As alluded in Section 2.0, there is a limited

number of literature that addressed the topic of waqf in the public finance context thus exhibits the

significance of this thesis. There are also positive implications beside from the literature gap. All

of these are summed up as follows:

I. This research made an effort to provide solutions to the Malaysian federal government

debt problem which is in need of urgent and continuous attention.

II. This research identifies the challenges and way forward for this particular implementation

of waqf hence can be used as a reference by persons of authority in Malaysia and

academicians worldwide.

III. This research can also possibly be of use as reference by other countries intending to

mimic this particular implementation of waqf which inadvertently adds on to the waqf

literature.

IV. This research establishes another solution to sustain debt aside from the typical conduct

of fiscal and monetary policy. Since waqf originates from Islamic economics and related

to the third sector economy, then this research has also introduced solutions to

government debt problem from these fields.

V. Following item IV, this research provides evidence on the significance of third sector role

and Islamic economics.

VI. This research contributes to the literature of waqf by helping to extend and argue the

implementation of waqf outside of its traditional uses thus expounding the need of waqf in

modern economy structure.

12

References

Ambrose, A. H. (2018). Impact of waqf financing on Federal government expenditure and

debt in Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and

Mixed Methods Approaches. California: SAGE Publications.

Kumar, R. (2011). Research Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners. London:

SAGE Publications.

References

Ambrose, A. H. (2018). Impact of waqf financing on Federal government expenditure and

debt in Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and

Mixed Methods Approaches. California: SAGE Publications.

Kumar, R. (2011). Research Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners. London:

SAGE Publications.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 12

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.