Research Methods: An Introductory Guide to Social Science Research

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/10

|19

|6305

|227

Report

AI Summary

This report serves as a brief introduction to research methods, beginning with an overview of the scientific method and its application. It explores deductive and inductive reasoning, contrasting the approaches used in natural and social sciences. The report then delves into the philosophical debate between positivism and interpretivism, highlighting their differing perspectives on objectivity and the role of the researcher. It also provides concise explanations of various research philosophies, including grounded theory, phenomenology, and ethnography. The report aims to provide a foundational understanding of research methodologies commonly used in social science, making it a valuable resource for students undertaking research projects.

1

Research Methods

A brief Introduction

“Between the rock of natural scientific and a hard place of

social science”

Peter Carroll

March 08

Research Methods

A brief Introduction

“Between the rock of natural scientific and a hard place of

social science”

Peter Carroll

March 08

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

Contents

1.0 Introduction

2.0 “The scientific method”

3.0 Deductive/Inductive reasoning

4.0 From natural science to social science

5.0 Positivism versus Interpretivism

6.0 Research Philosophies

7.0 Grounded theory

8.0 Phenomenology

9.0 Ethnography

10.0 The purpose of research

11.0 The Research Process

References

Contents

1.0 Introduction

2.0 “The scientific method”

3.0 Deductive/Inductive reasoning

4.0 From natural science to social science

5.0 Positivism versus Interpretivism

6.0 Research Philosophies

7.0 Grounded theory

8.0 Phenomenology

9.0 Ethnography

10.0 The purpose of research

11.0 The Research Process

References

3

1.0 Introduction

This is intended to be a short guide to the process of undertaking a small

scale research project. Undertaking research may be thought of as some kind

of experiment or investigation. The word experiment evokes images of

science whilst an investigation may lead to thoughts of detectives.

In general science tries to make sense of the natural world; it provides us with

theories that can be generally applied in solving problems of a similar kind.

Criminal investigations examine evidence and provide a theory to explain

what may have happened so that judgements can be made.

Interest in science and experimentation has been of interest to mankind since

at least the time of the ancient Greeks. Since ancient times mankind has also

sought to understand the nature of life and human interactions. This has given

rise to a branch of academic study known as philosophy and given fame to

the likes of Aristotle and Plato.

The Seventeenth Century saw a re-birth or renaissance in scientific interest

and discovery, giving rise to what is often referred to as “the scientific

method” The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century saw the emergence of new

areas of academic study such as sociology and psychology. The study of

chemistry and physics has often been referred to as “real science” whilst

sociology is often regarded as a “pseudo science”. It would appear that

making discoveries about electricity and atoms involve the gathering of hard

evidence leading to concrete conclusions. Social scientists have also sought

to analyse data and provide explanations between cause and effect. Their

purpose has been to help us make sense of the everyday world so that we

can understand whether “prison works” or what is the best method to teach

children how to read.

The social scientists have tended to try to adopt “the scientific method” as it

is perceived to have rigour and therefore legitimacy. However the challenge to

the scientist looking through the lens of a microscope at a virus is perhaps

different to the view taken by a sociologist, when observing the impact of the

welfare state.

Over time therefore difficulties have arisen in adopting “the scientific

method” in areas such as education, economics, politics and the general

area of humanities and social science. This has led to the development of

scientific approaches or methodologies rooted is some philosophical position

based upon “the scientific method” The scientific approach has been

adapted so that subjects coloured by human values and emotions can be

studied and analysed. This has been done in order to advance the study of

phenomena perhaps less tangible than forces or electricity..

In attempting to understand the range of “orthodox” methodologies that have

emerged such as epistemology or grounded theory, it is first necessary to

have a grasp of the classical “scientific method”.

1.0 Introduction

This is intended to be a short guide to the process of undertaking a small

scale research project. Undertaking research may be thought of as some kind

of experiment or investigation. The word experiment evokes images of

science whilst an investigation may lead to thoughts of detectives.

In general science tries to make sense of the natural world; it provides us with

theories that can be generally applied in solving problems of a similar kind.

Criminal investigations examine evidence and provide a theory to explain

what may have happened so that judgements can be made.

Interest in science and experimentation has been of interest to mankind since

at least the time of the ancient Greeks. Since ancient times mankind has also

sought to understand the nature of life and human interactions. This has given

rise to a branch of academic study known as philosophy and given fame to

the likes of Aristotle and Plato.

The Seventeenth Century saw a re-birth or renaissance in scientific interest

and discovery, giving rise to what is often referred to as “the scientific

method” The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century saw the emergence of new

areas of academic study such as sociology and psychology. The study of

chemistry and physics has often been referred to as “real science” whilst

sociology is often regarded as a “pseudo science”. It would appear that

making discoveries about electricity and atoms involve the gathering of hard

evidence leading to concrete conclusions. Social scientists have also sought

to analyse data and provide explanations between cause and effect. Their

purpose has been to help us make sense of the everyday world so that we

can understand whether “prison works” or what is the best method to teach

children how to read.

The social scientists have tended to try to adopt “the scientific method” as it

is perceived to have rigour and therefore legitimacy. However the challenge to

the scientist looking through the lens of a microscope at a virus is perhaps

different to the view taken by a sociologist, when observing the impact of the

welfare state.

Over time therefore difficulties have arisen in adopting “the scientific

method” in areas such as education, economics, politics and the general

area of humanities and social science. This has led to the development of

scientific approaches or methodologies rooted is some philosophical position

based upon “the scientific method” The scientific approach has been

adapted so that subjects coloured by human values and emotions can be

studied and analysed. This has been done in order to advance the study of

phenomena perhaps less tangible than forces or electricity..

In attempting to understand the range of “orthodox” methodologies that have

emerged such as epistemology or grounded theory, it is first necessary to

have a grasp of the classical “scientific method”.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

This guide therefore begins by looking at ideas connected with undertaking

research, discusses “the scientific method” and then seeks to provide a

thumbnail sketch of “orthodox” methodologies commonly used in social

science.

2.0 “The scientific method”

To understand “the scientific method”, consider Newton, as legend has it

standing in his garden observing apples falling from a tree. He evidently

wondered why it was that this happened. He seems to have recognised that

there was some force of attraction between the apple and the ground. He may

have similarly observed that most if not all objects seem to possess the

uncanny knack of falling to earth. This by itself is not a proof of a gravitational

force but it does provide persuasive evidence rooted in experience. Such

knowledge is known as empirical as it is based on experience; Newton then

developed his experience into a hypothesis from which he developed his

theory of gravitational attraction. Newton devised equations from which he

was able to make predictions of the force of gravitational attraction; this has

been tested found valid and reliable. This gave rise to a branch of physics

known as “Newtonian Mechanics” which was not contradicted until the early

Twentieth Century when scientists developed the study of quantum

mechanics and proved that in certain circumstances Newton’s prediction

doesn’t always hold true. This demonstrate the “the scientific method”, and

it also shows how it is difficult to ever say something is universally true for all

time. Hence theories are advanced tested and used until new evidence and

theories emerge.

Denscombe (2002; 7) comments

“The “natural science model” of research methodology provides the

best starting point for understanding the various issues and

controversies that surround social research. The debates about “good

practice” in social research sometimes favour the natural science

model. Either way, they do not ignore the natural science model and

more or less explicitly the arguments assume a basic knowledge of

what the principles are.”

This guide therefore begins by looking at ideas connected with undertaking

research, discusses “the scientific method” and then seeks to provide a

thumbnail sketch of “orthodox” methodologies commonly used in social

science.

2.0 “The scientific method”

To understand “the scientific method”, consider Newton, as legend has it

standing in his garden observing apples falling from a tree. He evidently

wondered why it was that this happened. He seems to have recognised that

there was some force of attraction between the apple and the ground. He may

have similarly observed that most if not all objects seem to possess the

uncanny knack of falling to earth. This by itself is not a proof of a gravitational

force but it does provide persuasive evidence rooted in experience. Such

knowledge is known as empirical as it is based on experience; Newton then

developed his experience into a hypothesis from which he developed his

theory of gravitational attraction. Newton devised equations from which he

was able to make predictions of the force of gravitational attraction; this has

been tested found valid and reliable. This gave rise to a branch of physics

known as “Newtonian Mechanics” which was not contradicted until the early

Twentieth Century when scientists developed the study of quantum

mechanics and proved that in certain circumstances Newton’s prediction

doesn’t always hold true. This demonstrate the “the scientific method”, and

it also shows how it is difficult to ever say something is universally true for all

time. Hence theories are advanced tested and used until new evidence and

theories emerge.

Denscombe (2002; 7) comments

“The “natural science model” of research methodology provides the

best starting point for understanding the various issues and

controversies that surround social research. The debates about “good

practice” in social research sometimes favour the natural science

model. Either way, they do not ignore the natural science model and

more or less explicitly the arguments assume a basic knowledge of

what the principles are.”

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

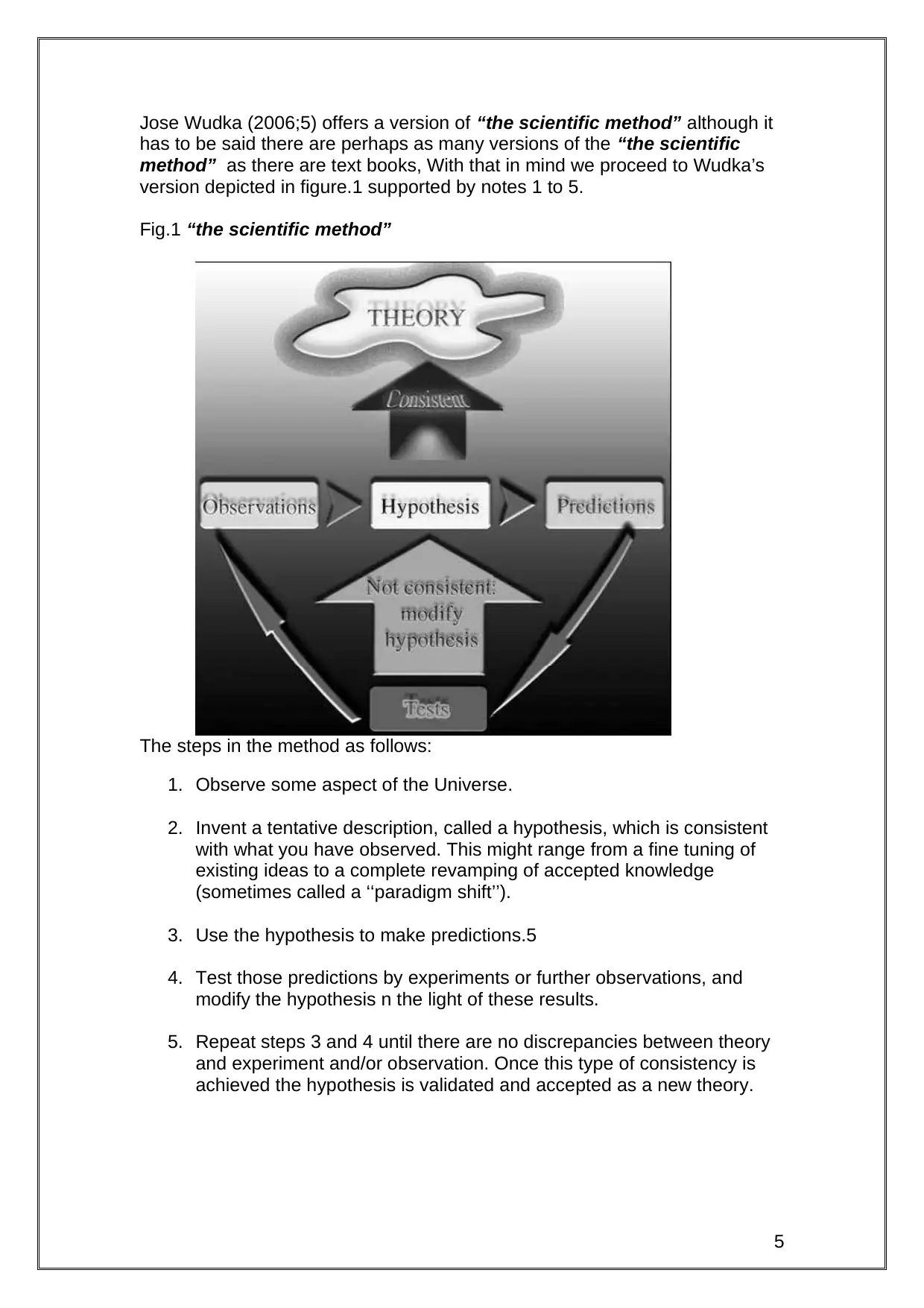

Jose Wudka (2006;5) offers a version of “the scientific method” although it

has to be said there are perhaps as many versions of the “the scientific

method” as there are text books, With that in mind we proceed to Wudka’s

version depicted in figure.1 supported by notes 1 to 5.

Fig.1 “the scientific method”

The steps in the method as follows:

1. Observe some aspect of the Universe.

2. Invent a tentative description, called a hypothesis, which is consistent

with what you have observed. This might range from a fine tuning of

existing ideas to a complete revamping of accepted knowledge

(sometimes called a ‘‘paradigm shift’’).

3. Use the hypothesis to make predictions.5

4. Test those predictions by experiments or further observations, and

modify the hypothesis n the light of these results.

5. Repeat steps 3 and 4 until there are no discrepancies between theory

and experiment and/or observation. Once this type of consistency is

achieved the hypothesis is validated and accepted as a new theory.

Jose Wudka (2006;5) offers a version of “the scientific method” although it

has to be said there are perhaps as many versions of the “the scientific

method” as there are text books, With that in mind we proceed to Wudka’s

version depicted in figure.1 supported by notes 1 to 5.

Fig.1 “the scientific method”

The steps in the method as follows:

1. Observe some aspect of the Universe.

2. Invent a tentative description, called a hypothesis, which is consistent

with what you have observed. This might range from a fine tuning of

existing ideas to a complete revamping of accepted knowledge

(sometimes called a ‘‘paradigm shift’’).

3. Use the hypothesis to make predictions.5

4. Test those predictions by experiments or further observations, and

modify the hypothesis n the light of these results.

5. Repeat steps 3 and 4 until there are no discrepancies between theory

and experiment and/or observation. Once this type of consistency is

achieved the hypothesis is validated and accepted as a new theory.

6

3.0 Deductive/Inductive reasoning

In applying “the scientific method” you may start with a theory i.e. a set of

scientific principles and then deduce whether an established set of principles

is valid in some defined context under particular circumstances.

Wudka (2006; 3) defines deductive reasoning as:

“Argument is based on a rule, law, principle, or generalization. In other

words, ‘‘I’m right because I said so.’’ Aristotle conducted some of the

earliest studies of the world around us, interpreting his observations

using this deductive approach. He did this by choosing a set of first

principles, which he considered eminently clear, obvious and natural”

In a sense the reverse of deductive reasoning is inductive reasoning which begins

with observation and then proceeds to rationalise observations into a coherent theory

that can be generally applied.

Wudka (2006; 3) defines Inductive reasoning

“Arguments are based on experience or observation. In other words,

‘‘I’m right and I can do an experiment to prove it.’’ The shift in science

from deductive to inductive reasoning was prompted by the various

writings of Francis Bacon, and perhaps more forcefully by the results

obtained by Galileo and Newton. The same basic approach used then

(with minor alterations) is still followed today in most research. The

reliability of scientific results we have come to expect is due to the

inductive approach.”

Wudka (2006;3) goes on to warn us that even Aristotle was capable of making

deductions based upon apparently logical observation leading to faulty

theories.

“In his work ‘‘The History of Animals’’ the Greek philosopher Aristotle

claimed that men and women had a different number of teeth, and that

their internal organs were also different.”

“A good example of the sort of logical traps hiding in deductive

reasoning can be seen in what is known as a syllogism. A syllogism is

a logically incorrect generalization. For example, one might state ‘‘All

cats have fur,’’ and then state ‘‘A dog has fur; therefore a dog is a cat.’’

Though it may seem silly to us now, this type of argument resulting

from the deductive approach formed the basis of science for centuries.”

3.0 Deductive/Inductive reasoning

In applying “the scientific method” you may start with a theory i.e. a set of

scientific principles and then deduce whether an established set of principles

is valid in some defined context under particular circumstances.

Wudka (2006; 3) defines deductive reasoning as:

“Argument is based on a rule, law, principle, or generalization. In other

words, ‘‘I’m right because I said so.’’ Aristotle conducted some of the

earliest studies of the world around us, interpreting his observations

using this deductive approach. He did this by choosing a set of first

principles, which he considered eminently clear, obvious and natural”

In a sense the reverse of deductive reasoning is inductive reasoning which begins

with observation and then proceeds to rationalise observations into a coherent theory

that can be generally applied.

Wudka (2006; 3) defines Inductive reasoning

“Arguments are based on experience or observation. In other words,

‘‘I’m right and I can do an experiment to prove it.’’ The shift in science

from deductive to inductive reasoning was prompted by the various

writings of Francis Bacon, and perhaps more forcefully by the results

obtained by Galileo and Newton. The same basic approach used then

(with minor alterations) is still followed today in most research. The

reliability of scientific results we have come to expect is due to the

inductive approach.”

Wudka (2006;3) goes on to warn us that even Aristotle was capable of making

deductions based upon apparently logical observation leading to faulty

theories.

“In his work ‘‘The History of Animals’’ the Greek philosopher Aristotle

claimed that men and women had a different number of teeth, and that

their internal organs were also different.”

“A good example of the sort of logical traps hiding in deductive

reasoning can be seen in what is known as a syllogism. A syllogism is

a logically incorrect generalization. For example, one might state ‘‘All

cats have fur,’’ and then state ‘‘A dog has fur; therefore a dog is a cat.’’

Though it may seem silly to us now, this type of argument resulting

from the deductive approach formed the basis of science for centuries.”

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

4.0 From natural science to social science

Having gained a rudimentary idea of “the scientific method” we can look at

the way social scientist have developed this model for tackling research more

sociological in nature.

It is worth however noting Denscombe’s caution (2002; 5)

“Theoretical debates have been deep, complicated and, sometimes,

abrasive between researches who hold different beliefs about the

nature of social reality (“ontology”) and competing visions about the

ways that humans create their knowledge about the social world in

which they live (“epistemology”). “

Immediately this quotation demonstrates how jargon laden the study of

research methods becomes. It is necessary to gain some grasp of this jargon

unfortunately it is difficult to find concise definitions which are free from further

reference to yet more jargon. Therefore other terms need to be understood

before you can sensibly proceed. The further one delves the more jargon

emerges and inevitably you are drawn into a deep philosophical world in

which religion and notions of being are discussed. In order to maintain a

practical perspective it is necessary to realise that only a basic understanding

is needed and as a result you are likely to fall into some semantic trap at

some point. Console yourself in what Denscombe has to say, particularly that

expert researchers constantly disagree even to the point of being abrasive!

Leaving aside for the time being ontology and epistemology we proceed by

comparing positivism with interpretivism.

5.0 Positivism versus Interpretivism

At the heart of the debate is whether the “the scientific method” provides an

adequate approach to studying and analysing the cause and effect of human

interaction. To understand this it is necessary to separate the “natural world”

from the “social world”. That is to say a world unaffected by the value

judgements of the people involved, as distinct from one where the feelings of

people are seen as affecting the collection of data and resulting analysis.

In the study of the “natural world” the researcher may be more likely to

observe and collect data in an unbiased and unobtrusive manner. The social

scientist however may lack detachment from his/her subject and indeed the

subject may be significantly affected by being observed. Moreover it may be

argued that atoms and molecules behave in a predictable and regular

manner. By contrast the study of social interaction is far less predictable;

hence it is not so easily analysed in order to produce some generalised

theory. The natural scientist is not so constrained by ethical issues as the

social scientist. When observing the behaviour of human beings the social

4.0 From natural science to social science

Having gained a rudimentary idea of “the scientific method” we can look at

the way social scientist have developed this model for tackling research more

sociological in nature.

It is worth however noting Denscombe’s caution (2002; 5)

“Theoretical debates have been deep, complicated and, sometimes,

abrasive between researches who hold different beliefs about the

nature of social reality (“ontology”) and competing visions about the

ways that humans create their knowledge about the social world in

which they live (“epistemology”). “

Immediately this quotation demonstrates how jargon laden the study of

research methods becomes. It is necessary to gain some grasp of this jargon

unfortunately it is difficult to find concise definitions which are free from further

reference to yet more jargon. Therefore other terms need to be understood

before you can sensibly proceed. The further one delves the more jargon

emerges and inevitably you are drawn into a deep philosophical world in

which religion and notions of being are discussed. In order to maintain a

practical perspective it is necessary to realise that only a basic understanding

is needed and as a result you are likely to fall into some semantic trap at

some point. Console yourself in what Denscombe has to say, particularly that

expert researchers constantly disagree even to the point of being abrasive!

Leaving aside for the time being ontology and epistemology we proceed by

comparing positivism with interpretivism.

5.0 Positivism versus Interpretivism

At the heart of the debate is whether the “the scientific method” provides an

adequate approach to studying and analysing the cause and effect of human

interaction. To understand this it is necessary to separate the “natural world”

from the “social world”. That is to say a world unaffected by the value

judgements of the people involved, as distinct from one where the feelings of

people are seen as affecting the collection of data and resulting analysis.

In the study of the “natural world” the researcher may be more likely to

observe and collect data in an unbiased and unobtrusive manner. The social

scientist however may lack detachment from his/her subject and indeed the

subject may be significantly affected by being observed. Moreover it may be

argued that atoms and molecules behave in a predictable and regular

manner. By contrast the study of social interaction is far less predictable;

hence it is not so easily analysed in order to produce some generalised

theory. The natural scientist is not so constrained by ethical issues as the

social scientist. When observing the behaviour of human beings the social

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

scientist must take into consideration the feelings and privacy of his/her

subject(s).

Denscombe (2002; 14) defines positivism as:

“Positivism is an approach to social research that seeks to apply the

natural science model to investigations of social phenomena and

explanations of the social world.”

Positivism is about making empirical observations from which theories can

be deduced. The position of positivism is to contend that the social world

functions in a given way independently of the conciseness of the subject

being observed and that of the researcher. Further that reality can be

measured objectively and the reality of a situation can be established. This

raises issues about what people know or what they believe to be true and

whether something is objectively true i.e. free of feeling or emotion.

By contrast interpretivism recognises that when people are being observed

that their behaviour will change and thus observations will be consequently

affected. Furthermore the values of the researcher will also impact on the

validity of the research. Researchers following this tradition have developed

research philosophies that seek to remedy what they see as defects in the

“the scientific method”.

By nature positivism tends towards being objective whereas interpretivism

calls for greater subjectivity. It follows therefore that positivism is more likely

to use statistical analysis than interpretivism. In consequence the data

associated with positivism is more likely to be quantitative whereas the

qualitative data is associated with interpretivism.

6.0 Research Philosophies

There are a number of research philosophies but only epistemology and

ontology will be considered here. Seeking a simple concise definition of

these terms is almost impossible and indeed there appears to be once again

a sea of academic debate over their meaning and more critically their

application.

Chambers Dictionary (1988:337: 729) defines epistemology as study or

theory of knowledge and ontology as Philosophy, study of being.

In part it would seem that epistemology asks questions about knowledge in

relation to perception or belief. Greek philosophers equated knowledge with

absolute truth. In other words something that is absolutely true with complete

certainty can be considered knowledge. Conducting research often involves

asking people their opinions or what they know. Frequently what they say they

know they truly believe. Often though deeply held views falls short of what is

actually true. It was commonly believed before Galileo that the earth was flat.

scientist must take into consideration the feelings and privacy of his/her

subject(s).

Denscombe (2002; 14) defines positivism as:

“Positivism is an approach to social research that seeks to apply the

natural science model to investigations of social phenomena and

explanations of the social world.”

Positivism is about making empirical observations from which theories can

be deduced. The position of positivism is to contend that the social world

functions in a given way independently of the conciseness of the subject

being observed and that of the researcher. Further that reality can be

measured objectively and the reality of a situation can be established. This

raises issues about what people know or what they believe to be true and

whether something is objectively true i.e. free of feeling or emotion.

By contrast interpretivism recognises that when people are being observed

that their behaviour will change and thus observations will be consequently

affected. Furthermore the values of the researcher will also impact on the

validity of the research. Researchers following this tradition have developed

research philosophies that seek to remedy what they see as defects in the

“the scientific method”.

By nature positivism tends towards being objective whereas interpretivism

calls for greater subjectivity. It follows therefore that positivism is more likely

to use statistical analysis than interpretivism. In consequence the data

associated with positivism is more likely to be quantitative whereas the

qualitative data is associated with interpretivism.

6.0 Research Philosophies

There are a number of research philosophies but only epistemology and

ontology will be considered here. Seeking a simple concise definition of

these terms is almost impossible and indeed there appears to be once again

a sea of academic debate over their meaning and more critically their

application.

Chambers Dictionary (1988:337: 729) defines epistemology as study or

theory of knowledge and ontology as Philosophy, study of being.

In part it would seem that epistemology asks questions about knowledge in

relation to perception or belief. Greek philosophers equated knowledge with

absolute truth. In other words something that is absolutely true with complete

certainty can be considered knowledge. Conducting research often involves

asking people their opinions or what they know. Frequently what they say they

know they truly believe. Often though deeply held views falls short of what is

actually true. It was commonly believed before Galileo that the earth was flat.

9

People believed this presumably because it squared with their every day

experiences, that it is to say it was a belief based upon empirical data.

Much of natural science relies upon empirical evidence with few things in

life being certain. However the value a theory lies in its ability to predict

outcomes with certainty. The problem of what constitutes knowledge in the

“social world” is substantially more difficult to ascertain The Government

frequently claim that fear of crime amongst the population is substantially

greater than the reality.

When epistemology is considered in relation to positivism and

interpretivism it can be seen that positivism is linked more to the collection

of quantitative data whist interpretivism is connected more with qualitative

data. Facts and figures tend to be regarded as more reliable than feelings or

opinions. The difficulty with social science is that research often delves into

areas where only subjective assessments can be made. For example you can

objectively count the number of people sent to prison however assessing the

impact of custodial sentences on criminals and attitudes of the threat of crime

amongst the public is deeply subjective. At a certain point perception

becomes reality whether it is a belief is rooted in truth or not. That it s to say,

that a strongly held belief can become a “self fulfilling prophecy”. This can

then affect people’s behaviour and an unfounded belief can become an

observable reality. Hence if a section of society is perceived in a certain way

they ultimately conform to the stereo-type imposed upon it by the broader

society. So if for example if a section of workers are perceived by

management to be lazy and untrustworthy they will ultimately conform to this

expectation. (See McGregor’s Theories X & Y)

Saunders et al (2007: 108) draw a distinction between epistemology and

ontology as follows:

“We noted earlier that epistemology concerns what constitutes

acceptable knowledge in a field of study. The key epistemological

question is “can the approach to the study of the social world including

that of management and business, be the same as to the approach to

studying the natural sciences?” The answer to that question points the

way to the acceptability of the knowledge developed from the research

process. Ontology on the other hand, is concerned with the nature of

reality. To a greater extent than epistemological considerations, this

raises questions of the assumptions researchers have about the world

operates and the commitment made to particular views.”

It may be noted that Saunders et al are somewhat cagey about drawing

categorical differences. It can be seen that epistemology and ontology

represent different schools of thought on the position that a researcher might

adopt in undertaking their research.

Whilst there maybe no clear definitions of what epistemology and ontology

are; it would seem that the main difference concerns the dynamic effects

people have on the situation in which they exist including the effect the

researcher has in influencing research findings.

People believed this presumably because it squared with their every day

experiences, that it is to say it was a belief based upon empirical data.

Much of natural science relies upon empirical evidence with few things in

life being certain. However the value a theory lies in its ability to predict

outcomes with certainty. The problem of what constitutes knowledge in the

“social world” is substantially more difficult to ascertain The Government

frequently claim that fear of crime amongst the population is substantially

greater than the reality.

When epistemology is considered in relation to positivism and

interpretivism it can be seen that positivism is linked more to the collection

of quantitative data whist interpretivism is connected more with qualitative

data. Facts and figures tend to be regarded as more reliable than feelings or

opinions. The difficulty with social science is that research often delves into

areas where only subjective assessments can be made. For example you can

objectively count the number of people sent to prison however assessing the

impact of custodial sentences on criminals and attitudes of the threat of crime

amongst the public is deeply subjective. At a certain point perception

becomes reality whether it is a belief is rooted in truth or not. That it s to say,

that a strongly held belief can become a “self fulfilling prophecy”. This can

then affect people’s behaviour and an unfounded belief can become an

observable reality. Hence if a section of society is perceived in a certain way

they ultimately conform to the stereo-type imposed upon it by the broader

society. So if for example if a section of workers are perceived by

management to be lazy and untrustworthy they will ultimately conform to this

expectation. (See McGregor’s Theories X & Y)

Saunders et al (2007: 108) draw a distinction between epistemology and

ontology as follows:

“We noted earlier that epistemology concerns what constitutes

acceptable knowledge in a field of study. The key epistemological

question is “can the approach to the study of the social world including

that of management and business, be the same as to the approach to

studying the natural sciences?” The answer to that question points the

way to the acceptability of the knowledge developed from the research

process. Ontology on the other hand, is concerned with the nature of

reality. To a greater extent than epistemological considerations, this

raises questions of the assumptions researchers have about the world

operates and the commitment made to particular views.”

It may be noted that Saunders et al are somewhat cagey about drawing

categorical differences. It can be seen that epistemology and ontology

represent different schools of thought on the position that a researcher might

adopt in undertaking their research.

Whilst there maybe no clear definitions of what epistemology and ontology

are; it would seem that the main difference concerns the dynamic effects

people have on the situation in which they exist including the effect the

researcher has in influencing research findings.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

Social science researchers adopting an ontological position recognise that

the influence people have in changing the circumstance under investigation.

So people may change their behaviour simply because they are being

observed, something which has come to be known as the “Hawthorn Effect”

In 1933 Elton Mayo studied a group of workers at the Hawthorne works of the

Western Electric Company in Chicago. He noted that a group of workers

became more productive whilst being the subject of an experiment in which

levels of illumination were changed. He concluded that the workers became

more motivated simply because they were flattered by the researcher’s

attention.

[http://www.psy.gla.ac.uk/] [~steve] accessed 3rd July 07

So an ontological position would not only consider the effect that the

researcher has on affecting the behaviour of the study group but also the

social dynamics that exist between people who are the subject of the study. It

also recognises the researcher can not approach a social situation without

being free from their own beliefs and values; this may also impact on the

value of the research. It follows that the “the scientific method” is seen as

inadequate under certain circumstances and hence different philosophical

stances have been developed.

Denscombe (2002; 18) explains:

“Social reality is something that is constructed and interpreted by

people – rather than something that exists objectively “out there”. From

the interpretivists’ point of view the social world does not have the

tangible, material qualities that allow it to be measured, touched or

observed in some way. It is a social creation, constructed in the minds

of people and reinforced through their interactions with each other. It is

a reality that only exists through the way people believe in it, relate to it

and interpret it. And for this reason, interpretivists tend to focus their

attention on the way people make sense of the world and how they

create their social world through their actions and interpretations of the

world. Whereas positivism focuses on the way the social reality exists

externally to people, acting as a constraining force on values and

behaviour. Interpretivist approaches stress the way people shape

society.”

Simplistically this appears to construct a spectrum from positivism to

interpretivism reflecting a range of philosophical positions from

epistemology to ontology.

Regrettably this is a gross simplification and indeed whist the impression that

epistemology and ontology are philosophies in the singular it appears that

there are multiple epistemologies and ontologies. So within these broad

philosophical categories, subcategories exist that have been developed by

different schools of thought that can be applied in a range to different fields of

study.

Social science researchers adopting an ontological position recognise that

the influence people have in changing the circumstance under investigation.

So people may change their behaviour simply because they are being

observed, something which has come to be known as the “Hawthorn Effect”

In 1933 Elton Mayo studied a group of workers at the Hawthorne works of the

Western Electric Company in Chicago. He noted that a group of workers

became more productive whilst being the subject of an experiment in which

levels of illumination were changed. He concluded that the workers became

more motivated simply because they were flattered by the researcher’s

attention.

[http://www.psy.gla.ac.uk/] [~steve] accessed 3rd July 07

So an ontological position would not only consider the effect that the

researcher has on affecting the behaviour of the study group but also the

social dynamics that exist between people who are the subject of the study. It

also recognises the researcher can not approach a social situation without

being free from their own beliefs and values; this may also impact on the

value of the research. It follows that the “the scientific method” is seen as

inadequate under certain circumstances and hence different philosophical

stances have been developed.

Denscombe (2002; 18) explains:

“Social reality is something that is constructed and interpreted by

people – rather than something that exists objectively “out there”. From

the interpretivists’ point of view the social world does not have the

tangible, material qualities that allow it to be measured, touched or

observed in some way. It is a social creation, constructed in the minds

of people and reinforced through their interactions with each other. It is

a reality that only exists through the way people believe in it, relate to it

and interpret it. And for this reason, interpretivists tend to focus their

attention on the way people make sense of the world and how they

create their social world through their actions and interpretations of the

world. Whereas positivism focuses on the way the social reality exists

externally to people, acting as a constraining force on values and

behaviour. Interpretivist approaches stress the way people shape

society.”

Simplistically this appears to construct a spectrum from positivism to

interpretivism reflecting a range of philosophical positions from

epistemology to ontology.

Regrettably this is a gross simplification and indeed whist the impression that

epistemology and ontology are philosophies in the singular it appears that

there are multiple epistemologies and ontologies. So within these broad

philosophical categories, subcategories exist that have been developed by

different schools of thought that can be applied in a range to different fields of

study.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

It can be seen that the occasional researcher could easily drown in a sea

academic debate and it is worth reflecting on what Denscombe (2002; 22) has

to say.

“There is, though, a more practical reason why the world of social

research does not involve a simple dichotomy between positivists and

interpretivists. This is that both positions have their strengths and

weaknesses and that in the maturing field of social research people are

becoming increasingly willing to acknowledge that neither position has

all the answers. There have been influential attempts to integrate the

two positions and get the best of both worlds but, at the beginning of

the twenty first century, it is fair to say that there is no theoretical

stance that has managed to successfully to combine the strong points

of either approach and avoid criticisms linked to their weaknesses.”

As there are debates, disagreement and perhaps lack of clarity amongst

academics it leaves researchers in need of some compromise. Pragmatism

is a position which seeks to steer a course through the methodological debate

whilst adopting some rigor in addressing a research question.

Saunders et al (2007; 110) confirm:

.

“Pragmatism argues that the most important determinant of the

research philosophy adopted is the research question – one approach

may be “better” than the other for answering particular questions.

Moreover, if the research question does not unambiguously state that

either a positivist or an Interpretivist philosophy is adopted, this

confirms the pragmatist’s view that it is perfectly possible to work with

both philosophies.”

Furthermore it can be seen that maintaining a sense of perspective between

following an “orthodox” philosophy and actually doing some practical research

is highly important. Julia Brannen (2005; 5) in her paper on mixed methods

research cautions:

“However, in putting more emphasis on methodology, we need also to

be mindful of Lewis Coser’s admonition to the American Sociological

Association made in 1975 against producing new generations of

researchers ‘with superior research skills but with a trained incapacity

to think in theoretically innovative ways’ (Coser 1975).”

7.0 Grounded theory

Grounded theory is a methodological approach pioneered in the 1960s by

sociologists Barney Glaser and Anslem Strauss. In general it is an inductive

approach based upon “the scientific method” That is to say that the

researcher commences their research without reference to an established

theory and seeks to gather data grounded in within the study. This tends to

suggest that the data is quantitative in nature; however interviews may be

used, which are perhaps coded and categorised afterwards.

It can be seen that the occasional researcher could easily drown in a sea

academic debate and it is worth reflecting on what Denscombe (2002; 22) has

to say.

“There is, though, a more practical reason why the world of social

research does not involve a simple dichotomy between positivists and

interpretivists. This is that both positions have their strengths and

weaknesses and that in the maturing field of social research people are

becoming increasingly willing to acknowledge that neither position has

all the answers. There have been influential attempts to integrate the

two positions and get the best of both worlds but, at the beginning of

the twenty first century, it is fair to say that there is no theoretical

stance that has managed to successfully to combine the strong points

of either approach and avoid criticisms linked to their weaknesses.”

As there are debates, disagreement and perhaps lack of clarity amongst

academics it leaves researchers in need of some compromise. Pragmatism

is a position which seeks to steer a course through the methodological debate

whilst adopting some rigor in addressing a research question.

Saunders et al (2007; 110) confirm:

.

“Pragmatism argues that the most important determinant of the

research philosophy adopted is the research question – one approach

may be “better” than the other for answering particular questions.

Moreover, if the research question does not unambiguously state that

either a positivist or an Interpretivist philosophy is adopted, this

confirms the pragmatist’s view that it is perfectly possible to work with

both philosophies.”

Furthermore it can be seen that maintaining a sense of perspective between

following an “orthodox” philosophy and actually doing some practical research

is highly important. Julia Brannen (2005; 5) in her paper on mixed methods

research cautions:

“However, in putting more emphasis on methodology, we need also to

be mindful of Lewis Coser’s admonition to the American Sociological

Association made in 1975 against producing new generations of

researchers ‘with superior research skills but with a trained incapacity

to think in theoretically innovative ways’ (Coser 1975).”

7.0 Grounded theory

Grounded theory is a methodological approach pioneered in the 1960s by

sociologists Barney Glaser and Anslem Strauss. In general it is an inductive

approach based upon “the scientific method” That is to say that the

researcher commences their research without reference to an established

theory and seeks to gather data grounded in within the study. This tends to

suggest that the data is quantitative in nature; however interviews may be

used, which are perhaps coded and categorised afterwards.

12

Denscombe (2002; 33) tells us:

“Where the research is more exploratory, setting on a journey of

discovery in which the researcher follows up leads and avenues of

enquiry as they emerge during the course of an investigation, it

becomes effectively impossible to be precise at the start about exactly

when and how many who and what will be the focus of the study.”

It follows therefore that this practice is used in more experimental research

where it is inevitable that the research question may lack definition. However

as the research proceeds a body theory may emerge which can then form the

basis for more research. As theory emerges and is subsequently tested

research moves from being inductive to deductive.

Saunders et al (2007; 142) confirms this view:

“Grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss) is often thought of the best

example of the inductive approach, although this conclusion would be

too simplistic. It s better think of it as “theory building” through a

combination of induction and deduction.”

8.0 Phenomenology

Myron Orleans defines phenomenology as:

“Phenomenology is a movement in philosophy that has been adapted

by certain sociologists to promote an understanding of the relationship

between states of individual consciousness and social life. As an

approach within sociology, phenomenology seeks to reveal how human

awareness is implicated in the production of social action, social

situations and social worlds (Natanson 1970).”

shttp://hss.fullerton.edu/sociology/orleans/phenomenology.htm accessed 3rd

July 07

Phenomenology was developed by a German mathematician Edmund

Husserl (1859-1938). He felt that “the scientific method” was inadequate

when applied to the way humans make sense of their social situation.

The challenge for the researcher when researching the social world of others

is to remain objective.

Denscombe (2002; 168) states:

“Objectivity in social research calls for detachment. Such a

detachment, though need not involve the impossible demand for the

researcher to somehow to cease to be a social person with views of his

or her own, with emotions or preferences, with a lifetime of experiences

Denscombe (2002; 33) tells us:

“Where the research is more exploratory, setting on a journey of

discovery in which the researcher follows up leads and avenues of

enquiry as they emerge during the course of an investigation, it

becomes effectively impossible to be precise at the start about exactly

when and how many who and what will be the focus of the study.”

It follows therefore that this practice is used in more experimental research

where it is inevitable that the research question may lack definition. However

as the research proceeds a body theory may emerge which can then form the

basis for more research. As theory emerges and is subsequently tested

research moves from being inductive to deductive.

Saunders et al (2007; 142) confirms this view:

“Grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss) is often thought of the best

example of the inductive approach, although this conclusion would be

too simplistic. It s better think of it as “theory building” through a

combination of induction and deduction.”

8.0 Phenomenology

Myron Orleans defines phenomenology as:

“Phenomenology is a movement in philosophy that has been adapted

by certain sociologists to promote an understanding of the relationship

between states of individual consciousness and social life. As an

approach within sociology, phenomenology seeks to reveal how human

awareness is implicated in the production of social action, social

situations and social worlds (Natanson 1970).”

shttp://hss.fullerton.edu/sociology/orleans/phenomenology.htm accessed 3rd

July 07

Phenomenology was developed by a German mathematician Edmund

Husserl (1859-1938). He felt that “the scientific method” was inadequate

when applied to the way humans make sense of their social situation.

The challenge for the researcher when researching the social world of others

is to remain objective.

Denscombe (2002; 168) states:

“Objectivity in social research calls for detachment. Such a

detachment, though need not involve the impossible demand for the

researcher to somehow to cease to be a social person with views of his

or her own, with emotions or preferences, with a lifetime of experiences

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 19

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.