Exploring Research Paradigms: A Guide to Methodology and Methods

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/20

|22

|8165

|316

Literature Review

AI Summary

This document provides a detailed overview of selecting a research approach by examining various paradigms, methodologies, and methods. It begins by defining a paradigm as a shared worldview influenced by philosophical assumptions about social reality, ways of knowing, and value systems. The review explores several paradigms, including positivism/post-positivism, constructivism/interpretativism, transformative/emancipatory, and postcolonial indigenous research paradigms, detailing their philosophical underpinnings, ontological assumptions, and epistemological considerations. The document emphasizes the relationship between paradigm and methodology, highlighting how paradigms inform the research process, theoretical frameworks, data collection, analysis, and ethical considerations. It also discusses the shift from positivism to post-positivism, influenced by critical realism, and includes a comparison table summarizing the key aspects of each paradigm. The document concludes by emphasizing the importance of understanding these paradigms in shaping research design and answering research questions effectively. Desklib is a valuable platform for students seeking similar solved assignments and study resources.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257944787

Selecting a research approach: Paradigm, methodology and methods

Chapter · January 2012

CITATIONS

6

READS

135,097

1 author:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Research methods pedagogyView project

Barbara Kawulich

University of West Georgia

37PUBLICATIONS586CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Barbara Kawulich on 08 October 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Selecting a research approach: Paradigm, methodology and methods

Chapter · January 2012

CITATIONS

6

READS

135,097

1 author:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Research methods pedagogyView project

Barbara Kawulich

University of West Georgia

37PUBLICATIONS586CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Barbara Kawulich on 08 October 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1

CHAPTER 3

Selecting a research approach: paradigm, methodology and methods

Bagele Chilisa

Barbara Kawulich

Once you have a topic in mind to study, you must consider how you want to go about investigating it.

Your approach will depend upon how you think about the problem and how it can be studied, such

that the findings are credible to you and others in your discipline. Every researcher has his/her own

view of what constitutes truth and knowledge. These views guide our thinking, our beliefs, and our

assumptions about society and ourselves, and they frame how we view the world around us, which is

what social scientists call a paradigm (Schwandt, 2001). In his monograph The Structure of Scientific

Revolutions (1962), Thomas Kuhn used the term ‘paradigm’ in two ways:

1. to represent a particular way of thinking that is shared by a community of scientists in

solving problems in their field and

2. to represent the “commitments, beliefs, values, methods, outlooks and so forth

shared across a discipline” (Schwandt, 2001, p. 183-4).

A paradigm is a way of describing a world view that is informed by philosophical assumptions about

the nature of social reality (known as ontology – that is, what do we believe about the nature of

reality?), ways of knowing (known as epistemology – that is, how do we know what we know?), and

ethics and value systems (known as axiology – that is, what do we believe is true?) (Patton, 2002). A

paradigm thus leads us to ask certain questions and use appropriate approaches to systematic inquiry

(known as methodology – that is, how should we study the world?). Ontology relates to whether we

believe there is one verifiable reality or whether there exist multiple, socially constructed realities

(Patton, 2002). Epistemology inquires into the nature of knowledge and truth. It asks the following

questions: What are the sources of knowledge? How reliable are these sources? What can one

know? How does one know if something is true? For instance, consider that some people think that

A paradigm is a shared world view that represents the beliefs and

values in a discipline and that guides how problems are solved

(Schwandt, 2001).

CHAPTER 3

Selecting a research approach: paradigm, methodology and methods

Bagele Chilisa

Barbara Kawulich

Once you have a topic in mind to study, you must consider how you want to go about investigating it.

Your approach will depend upon how you think about the problem and how it can be studied, such

that the findings are credible to you and others in your discipline. Every researcher has his/her own

view of what constitutes truth and knowledge. These views guide our thinking, our beliefs, and our

assumptions about society and ourselves, and they frame how we view the world around us, which is

what social scientists call a paradigm (Schwandt, 2001). In his monograph The Structure of Scientific

Revolutions (1962), Thomas Kuhn used the term ‘paradigm’ in two ways:

1. to represent a particular way of thinking that is shared by a community of scientists in

solving problems in their field and

2. to represent the “commitments, beliefs, values, methods, outlooks and so forth

shared across a discipline” (Schwandt, 2001, p. 183-4).

A paradigm is a way of describing a world view that is informed by philosophical assumptions about

the nature of social reality (known as ontology – that is, what do we believe about the nature of

reality?), ways of knowing (known as epistemology – that is, how do we know what we know?), and

ethics and value systems (known as axiology – that is, what do we believe is true?) (Patton, 2002). A

paradigm thus leads us to ask certain questions and use appropriate approaches to systematic inquiry

(known as methodology – that is, how should we study the world?). Ontology relates to whether we

believe there is one verifiable reality or whether there exist multiple, socially constructed realities

(Patton, 2002). Epistemology inquires into the nature of knowledge and truth. It asks the following

questions: What are the sources of knowledge? How reliable are these sources? What can one

know? How does one know if something is true? For instance, consider that some people think that

A paradigm is a shared world view that represents the beliefs and

values in a discipline and that guides how problems are solved

(Schwandt, 2001).

2

the notion that witches exist is just a belief. Epistemology asks further questions: Is a belief true

knowledge? Or is knowledge only that which can be proven using concrete data? For example, if you

say witches exist, what is the source of your evidence? What methods can you use to find out about

their existence? Together, these paradigmatic aspects help to determine the assumptions and beliefs

that frame a researcher’s view of a research problem, how he/she goes about investigating it, and the

methods he/she uses to answer the research questions.

The objectives of this chapter are to:

1. Describe the following paradigms: positivism/post-positivism,

constructivism/interpretativism, transformative/emancipatory and postcolonial

indigenous research paradigm.

2. Describe philosophical assumptions about perceptions of reality, what counts as truth

and value systems in each of the paradigms.

3. Demonstrate the relationship between paradigm and methodology.

PARADIGM, METHODOLOGY AND METHODS

Particular paradigms may be associated with certain methodologies. For example, as will be

discussed in more detail later in this chapter, a positivistic paradigm typically assumes a quantitative

methodology, while a constructivist or interpretative paradigm typically utilizes a qualitative

methodology. This is not universally the case, however; there are instances in which one may pursue

an interpretative study using a quantitative methodology. No one paradigmatic or theoretical

framework is ‘correct’ and it is your choice to determine your own paradigmatic view and how that

informs your research design to best answer the question under study. How you view what is real,

what you know and how you know it, along with the theoretical perspective(s) you have about the

topic under study, the literature that exists on the subject, and your own value system work together to

help you select the paradigm most appropriate for you to use (See Figure 3.1).

the notion that witches exist is just a belief. Epistemology asks further questions: Is a belief true

knowledge? Or is knowledge only that which can be proven using concrete data? For example, if you

say witches exist, what is the source of your evidence? What methods can you use to find out about

their existence? Together, these paradigmatic aspects help to determine the assumptions and beliefs

that frame a researcher’s view of a research problem, how he/she goes about investigating it, and the

methods he/she uses to answer the research questions.

The objectives of this chapter are to:

1. Describe the following paradigms: positivism/post-positivism,

constructivism/interpretativism, transformative/emancipatory and postcolonial

indigenous research paradigm.

2. Describe philosophical assumptions about perceptions of reality, what counts as truth

and value systems in each of the paradigms.

3. Demonstrate the relationship between paradigm and methodology.

PARADIGM, METHODOLOGY AND METHODS

Particular paradigms may be associated with certain methodologies. For example, as will be

discussed in more detail later in this chapter, a positivistic paradigm typically assumes a quantitative

methodology, while a constructivist or interpretative paradigm typically utilizes a qualitative

methodology. This is not universally the case, however; there are instances in which one may pursue

an interpretative study using a quantitative methodology. No one paradigmatic or theoretical

framework is ‘correct’ and it is your choice to determine your own paradigmatic view and how that

informs your research design to best answer the question under study. How you view what is real,

what you know and how you know it, along with the theoretical perspective(s) you have about the

topic under study, the literature that exists on the subject, and your own value system work together to

help you select the paradigm most appropriate for you to use (See Figure 3.1).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3

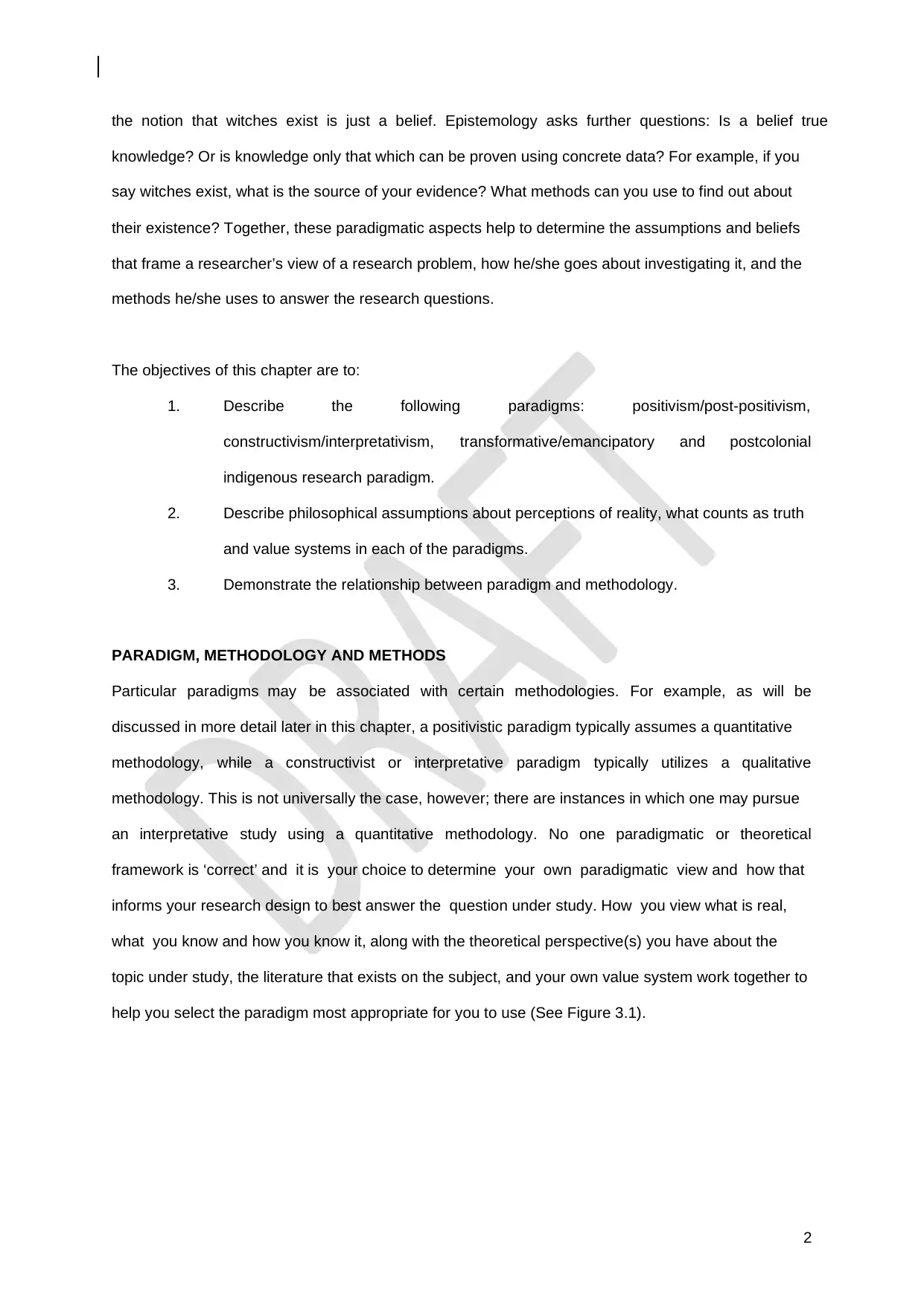

Figure 3.1 Factors influencing the choice of a paradigm

The methodology summarizes the research process, that is, how the research will proceed. Deciding

on a methodology starts with a choice of the research paradigm that informs the study. The

methodological process, therefore, is guided by philosophical beliefs about the nature of reality,

knowledge, and values and by the theoretical framework that informs comprehension, interpretation,

choice of literature and research practice on a given topic of study (see Figure 3.2). Methodology is

where assumptions about the nature of reality and knowledge, values, and theory and practice on a

given topic come together. Figure 3.2 illustrates the relationship. Methods are the means used for

gathering data and are an important part of the methodology.

Figure 3.1 Factors influencing the choice of a paradigm

The methodology summarizes the research process, that is, how the research will proceed. Deciding

on a methodology starts with a choice of the research paradigm that informs the study. The

methodological process, therefore, is guided by philosophical beliefs about the nature of reality,

knowledge, and values and by the theoretical framework that informs comprehension, interpretation,

choice of literature and research practice on a given topic of study (see Figure 3.2). Methodology is

where assumptions about the nature of reality and knowledge, values, and theory and practice on a

given topic come together. Figure 3.2 illustrates the relationship. Methods are the means used for

gathering data and are an important part of the methodology.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4

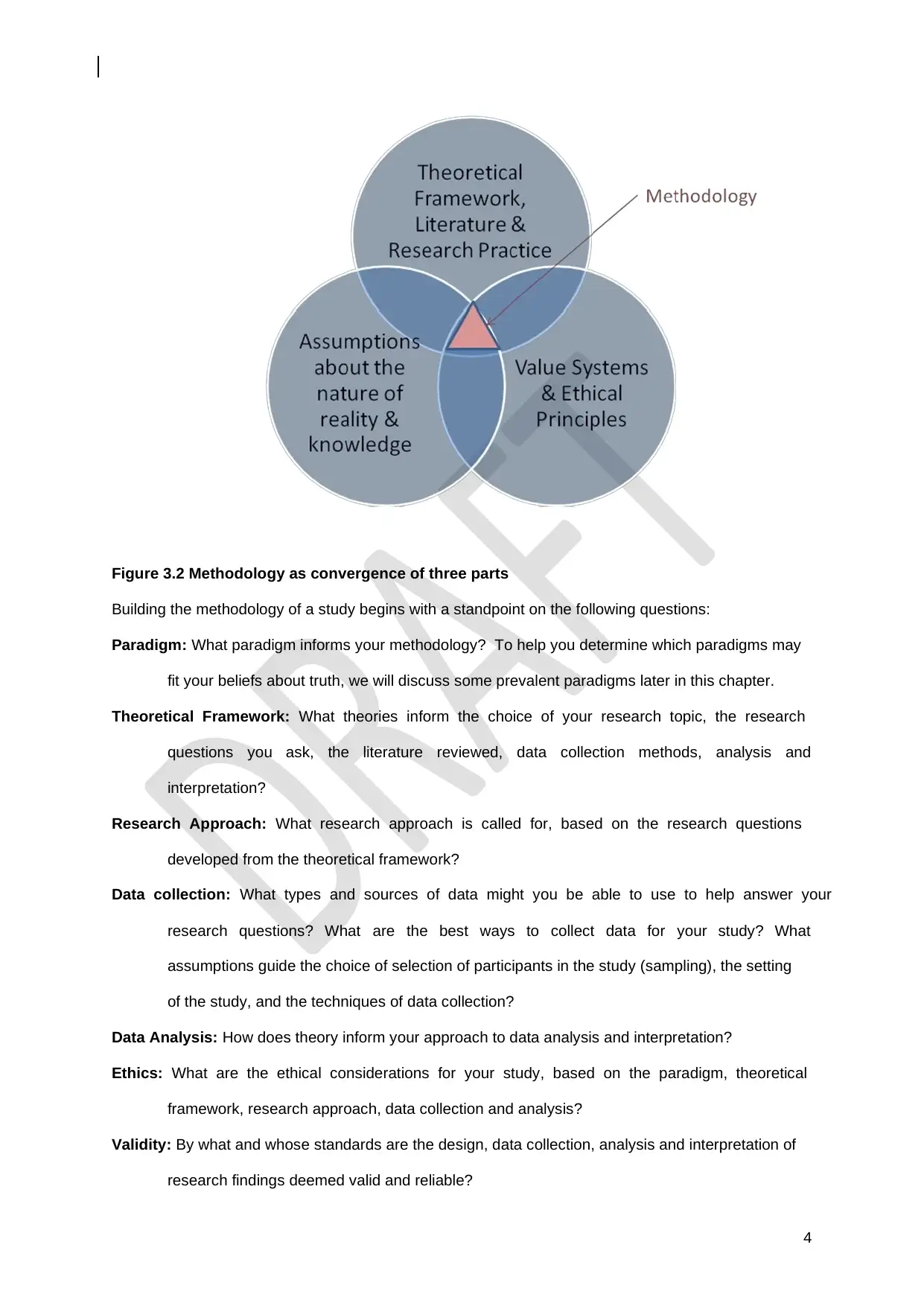

Figure 3.2 Methodology as convergence of three parts

Building the methodology of a study begins with a standpoint on the following questions:

Paradigm: What paradigm informs your methodology? To help you determine which paradigms may

fit your beliefs about truth, we will discuss some prevalent paradigms later in this chapter.

Theoretical Framework: What theories inform the choice of your research topic, the research

questions you ask, the literature reviewed, data collection methods, analysis and

interpretation?

Research Approach: What research approach is called for, based on the research questions

developed from the theoretical framework?

Data collection: What types and sources of data might you be able to use to help answer your

research questions? What are the best ways to collect data for your study? What

assumptions guide the choice of selection of participants in the study (sampling), the setting

of the study, and the techniques of data collection?

Data Analysis: How does theory inform your approach to data analysis and interpretation?

Ethics: What are the ethical considerations for your study, based on the paradigm, theoretical

framework, research approach, data collection and analysis?

Validity: By what and whose standards are the design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of

research findings deemed valid and reliable?

Figure 3.2 Methodology as convergence of three parts

Building the methodology of a study begins with a standpoint on the following questions:

Paradigm: What paradigm informs your methodology? To help you determine which paradigms may

fit your beliefs about truth, we will discuss some prevalent paradigms later in this chapter.

Theoretical Framework: What theories inform the choice of your research topic, the research

questions you ask, the literature reviewed, data collection methods, analysis and

interpretation?

Research Approach: What research approach is called for, based on the research questions

developed from the theoretical framework?

Data collection: What types and sources of data might you be able to use to help answer your

research questions? What are the best ways to collect data for your study? What

assumptions guide the choice of selection of participants in the study (sampling), the setting

of the study, and the techniques of data collection?

Data Analysis: How does theory inform your approach to data analysis and interpretation?

Ethics: What are the ethical considerations for your study, based on the paradigm, theoretical

framework, research approach, data collection and analysis?

Validity: By what and whose standards are the design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of

research findings deemed valid and reliable?

5

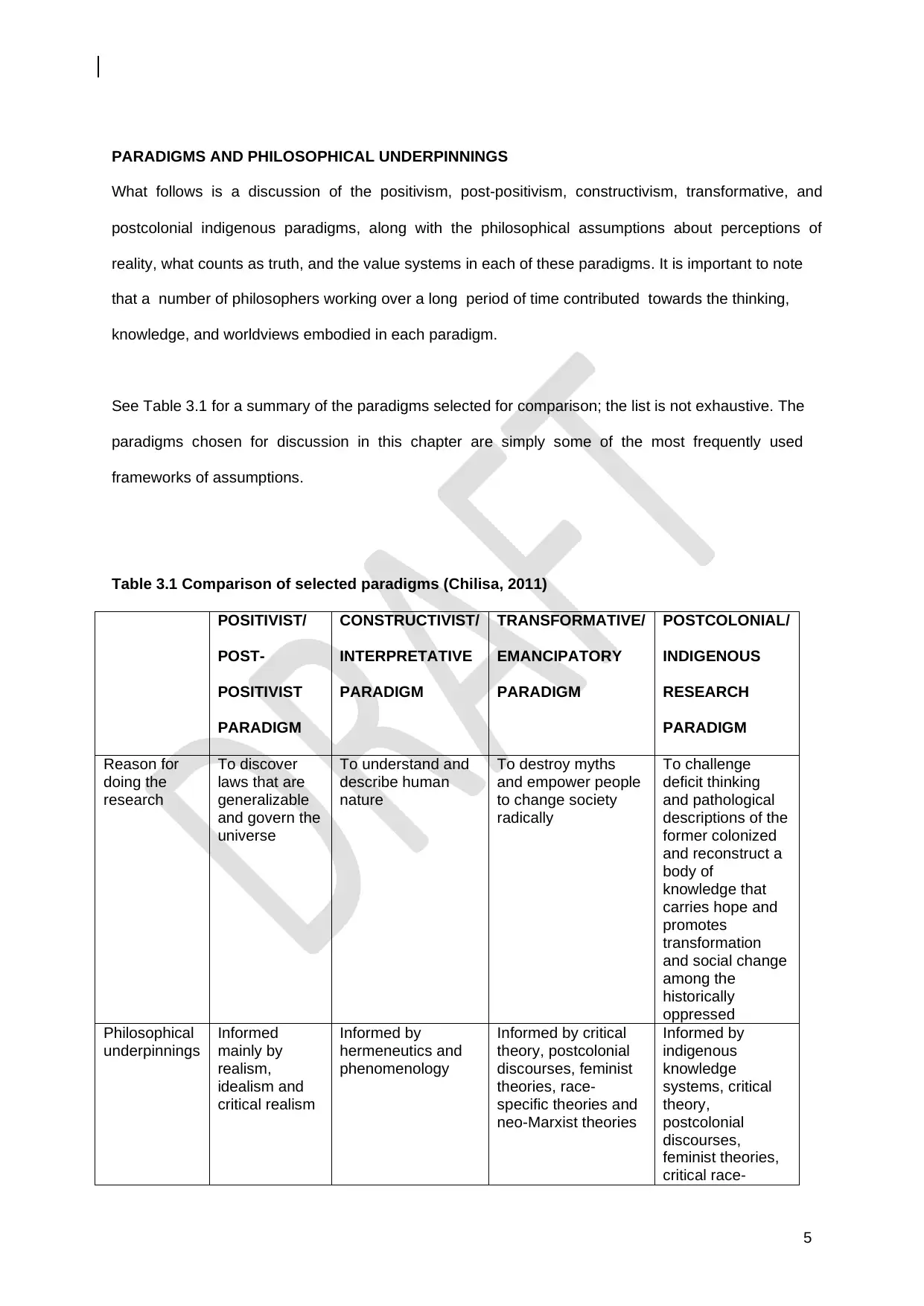

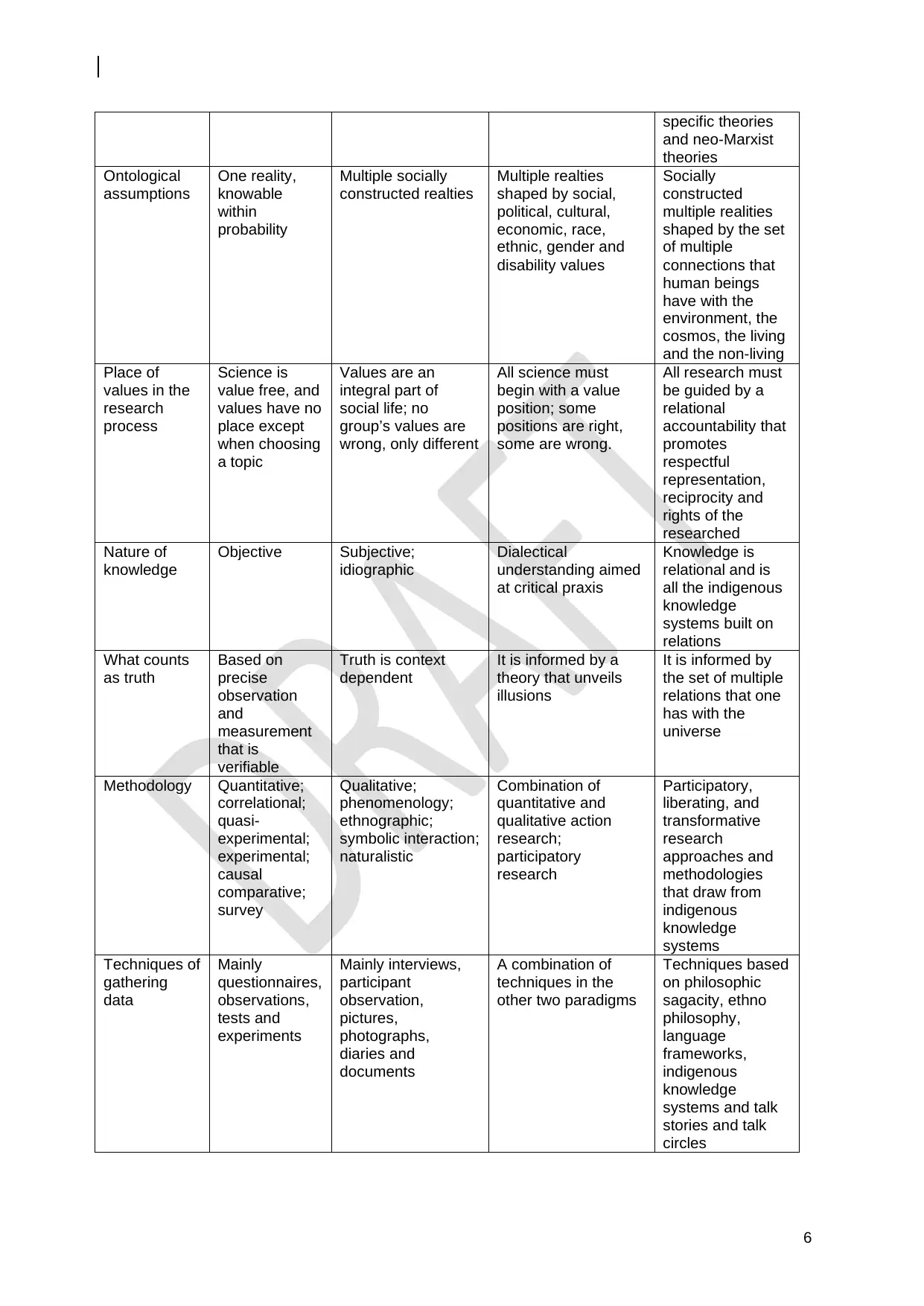

PARADIGMS AND PHILOSOPHICAL UNDERPINNINGS

What follows is a discussion of the positivism, post-positivism, constructivism, transformative, and

postcolonial indigenous paradigms, along with the philosophical assumptions about perceptions of

reality, what counts as truth, and the value systems in each of these paradigms. It is important to note

that a number of philosophers working over a long period of time contributed towards the thinking,

knowledge, and worldviews embodied in each paradigm.

See Table 3.1 for a summary of the paradigms selected for comparison; the list is not exhaustive. The

paradigms chosen for discussion in this chapter are simply some of the most frequently used

frameworks of assumptions.

Table 3.1 Comparison of selected paradigms (Chilisa, 2011)

POSITIVIST/

POST-

POSITIVIST

PARADIGM

CONSTRUCTIVIST/

INTERPRETATIVE

PARADIGM

TRANSFORMATIVE/

EMANCIPATORY

PARADIGM

POSTCOLONIAL/

INDIGENOUS

RESEARCH

PARADIGM

Reason for

doing the

research

To discover

laws that are

generalizable

and govern the

universe

To understand and

describe human

nature

To destroy myths

and empower people

to change society

radically

To challenge

deficit thinking

and pathological

descriptions of the

former colonized

and reconstruct a

body of

knowledge that

carries hope and

promotes

transformation

and social change

among the

historically

oppressed

Philosophical

underpinnings

Informed

mainly by

realism,

idealism and

critical realism

Informed by

hermeneutics and

phenomenology

Informed by critical

theory, postcolonial

discourses, feminist

theories, race-

specific theories and

neo-Marxist theories

Informed by

indigenous

knowledge

systems, critical

theory,

postcolonial

discourses,

feminist theories,

critical race-

PARADIGMS AND PHILOSOPHICAL UNDERPINNINGS

What follows is a discussion of the positivism, post-positivism, constructivism, transformative, and

postcolonial indigenous paradigms, along with the philosophical assumptions about perceptions of

reality, what counts as truth, and the value systems in each of these paradigms. It is important to note

that a number of philosophers working over a long period of time contributed towards the thinking,

knowledge, and worldviews embodied in each paradigm.

See Table 3.1 for a summary of the paradigms selected for comparison; the list is not exhaustive. The

paradigms chosen for discussion in this chapter are simply some of the most frequently used

frameworks of assumptions.

Table 3.1 Comparison of selected paradigms (Chilisa, 2011)

POSITIVIST/

POST-

POSITIVIST

PARADIGM

CONSTRUCTIVIST/

INTERPRETATIVE

PARADIGM

TRANSFORMATIVE/

EMANCIPATORY

PARADIGM

POSTCOLONIAL/

INDIGENOUS

RESEARCH

PARADIGM

Reason for

doing the

research

To discover

laws that are

generalizable

and govern the

universe

To understand and

describe human

nature

To destroy myths

and empower people

to change society

radically

To challenge

deficit thinking

and pathological

descriptions of the

former colonized

and reconstruct a

body of

knowledge that

carries hope and

promotes

transformation

and social change

among the

historically

oppressed

Philosophical

underpinnings

Informed

mainly by

realism,

idealism and

critical realism

Informed by

hermeneutics and

phenomenology

Informed by critical

theory, postcolonial

discourses, feminist

theories, race-

specific theories and

neo-Marxist theories

Informed by

indigenous

knowledge

systems, critical

theory,

postcolonial

discourses,

feminist theories,

critical race-

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6

specific theories

and neo-Marxist

theories

Ontological

assumptions

One reality,

knowable

within

probability

Multiple socially

constructed realties

Multiple realties

shaped by social,

political, cultural,

economic, race,

ethnic, gender and

disability values

Socially

constructed

multiple realities

shaped by the set

of multiple

connections that

human beings

have with the

environment, the

cosmos, the living

and the non-living

Place of

values in the

research

process

Science is

value free, and

values have no

place except

when choosing

a topic

Values are an

integral part of

social life; no

group’s values are

wrong, only different

All science must

begin with a value

position; some

positions are right,

some are wrong.

All research must

be guided by a

relational

accountability that

promotes

respectful

representation,

reciprocity and

rights of the

researched

Nature of

knowledge

Objective Subjective;

idiographic

Dialectical

understanding aimed

at critical praxis

Knowledge is

relational and is

all the indigenous

knowledge

systems built on

relations

What counts

as truth

Based on

precise

observation

and

measurement

that is

verifiable

Truth is context

dependent

It is informed by a

theory that unveils

illusions

It is informed by

the set of multiple

relations that one

has with the

universe

Methodology Quantitative;

correlational;

quasi-

experimental;

experimental;

causal

comparative;

survey

Qualitative;

phenomenology;

ethnographic;

symbolic interaction;

naturalistic

Combination of

quantitative and

qualitative action

research;

participatory

research

Participatory,

liberating, and

transformative

research

approaches and

methodologies

that draw from

indigenous

knowledge

systems

Techniques of

gathering

data

Mainly

questionnaires,

observations,

tests and

experiments

Mainly interviews,

participant

observation,

pictures,

photographs,

diaries and

documents

A combination of

techniques in the

other two paradigms

Techniques based

on philosophic

sagacity, ethno

philosophy,

language

frameworks,

indigenous

knowledge

systems and talk

stories and talk

circles

specific theories

and neo-Marxist

theories

Ontological

assumptions

One reality,

knowable

within

probability

Multiple socially

constructed realties

Multiple realties

shaped by social,

political, cultural,

economic, race,

ethnic, gender and

disability values

Socially

constructed

multiple realities

shaped by the set

of multiple

connections that

human beings

have with the

environment, the

cosmos, the living

and the non-living

Place of

values in the

research

process

Science is

value free, and

values have no

place except

when choosing

a topic

Values are an

integral part of

social life; no

group’s values are

wrong, only different

All science must

begin with a value

position; some

positions are right,

some are wrong.

All research must

be guided by a

relational

accountability that

promotes

respectful

representation,

reciprocity and

rights of the

researched

Nature of

knowledge

Objective Subjective;

idiographic

Dialectical

understanding aimed

at critical praxis

Knowledge is

relational and is

all the indigenous

knowledge

systems built on

relations

What counts

as truth

Based on

precise

observation

and

measurement

that is

verifiable

Truth is context

dependent

It is informed by a

theory that unveils

illusions

It is informed by

the set of multiple

relations that one

has with the

universe

Methodology Quantitative;

correlational;

quasi-

experimental;

experimental;

causal

comparative;

survey

Qualitative;

phenomenology;

ethnographic;

symbolic interaction;

naturalistic

Combination of

quantitative and

qualitative action

research;

participatory

research

Participatory,

liberating, and

transformative

research

approaches and

methodologies

that draw from

indigenous

knowledge

systems

Techniques of

gathering

data

Mainly

questionnaires,

observations,

tests and

experiments

Mainly interviews,

participant

observation,

pictures,

photographs,

diaries and

documents

A combination of

techniques in the

other two paradigms

Techniques based

on philosophic

sagacity, ethno

philosophy,

language

frameworks,

indigenous

knowledge

systems and talk

stories and talk

circles

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7

Positivism/Post-positivism paradigm

Positivism (also known as logical positivism) holds that the scientific method is the only way to

establish truth and objective reality. Can you imagine using scientific methods to carry out research on

witches? The positivists would conclude that, since the scientific method does not yield any tangible

results on the nature of witches, then witches do not exist. Positivism is based upon the view that

science is the only foundation for true knowledge. It holds that the methods, techniques and

procedures used in the natural sciences offer the best framework for investigating the social world.

The term ‘positivism’ was coined by Auguste Compte to reflect a strict empirical approach in which

claims about knowledge are based directly on experience; it emphasizes facts and the causes of

behaviour (Bogdan & Biklen, 2003). Compte sought to distinguish between empirical knowledge and

knowledge derived from metaphysics or theology; he proposed that scientific knowledge was more

representative of truth than that derived from metaphysical speculation (Schwandt, 2001, p. 199).

Positivism typically applies the scientific method to the study of human action. Positivism today is

viewed as being objectivist – that is, objects around us have existence and meaning, independent of

our consciousness of them (Crotty, 1998). The middle part of the 20

th century saw a shift from

positivism to post-positivism.

Post-positivism

Physicists Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr chipped away at the dogmatic view of positivism,

turning the emphasis from absolute certainty to probability; they portrayed the scientist as one who

constructs knowledge, instead of just passively noting the laws of nature (Crotty, 1998). Their

argument is that “no matter how faithfully the scientist adheres to scientific method research, research

outcomes are neither totally objective, nor unquestionably certain” (Crotty, 1998, p. 40). This view is

known as post-positivism (or logical empiricism); it describes a less strict form of positivism. Logical

empiricists (or post-positivists) support the idea that social scientists and natural scientists share the

same goals for research and employ similar methods of investigation.

Post-positivism is influenced by a philosophy called critical realism (Trochim, 2002). It can be

distinguished from positivism according to whether the focus is on theory verification (positivism) or on

Positivism/Post-positivism paradigm

Positivism (also known as logical positivism) holds that the scientific method is the only way to

establish truth and objective reality. Can you imagine using scientific methods to carry out research on

witches? The positivists would conclude that, since the scientific method does not yield any tangible

results on the nature of witches, then witches do not exist. Positivism is based upon the view that

science is the only foundation for true knowledge. It holds that the methods, techniques and

procedures used in the natural sciences offer the best framework for investigating the social world.

The term ‘positivism’ was coined by Auguste Compte to reflect a strict empirical approach in which

claims about knowledge are based directly on experience; it emphasizes facts and the causes of

behaviour (Bogdan & Biklen, 2003). Compte sought to distinguish between empirical knowledge and

knowledge derived from metaphysics or theology; he proposed that scientific knowledge was more

representative of truth than that derived from metaphysical speculation (Schwandt, 2001, p. 199).

Positivism typically applies the scientific method to the study of human action. Positivism today is

viewed as being objectivist – that is, objects around us have existence and meaning, independent of

our consciousness of them (Crotty, 1998). The middle part of the 20

th century saw a shift from

positivism to post-positivism.

Post-positivism

Physicists Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr chipped away at the dogmatic view of positivism,

turning the emphasis from absolute certainty to probability; they portrayed the scientist as one who

constructs knowledge, instead of just passively noting the laws of nature (Crotty, 1998). Their

argument is that “no matter how faithfully the scientist adheres to scientific method research, research

outcomes are neither totally objective, nor unquestionably certain” (Crotty, 1998, p. 40). This view is

known as post-positivism (or logical empiricism); it describes a less strict form of positivism. Logical

empiricists (or post-positivists) support the idea that social scientists and natural scientists share the

same goals for research and employ similar methods of investigation.

Post-positivism is influenced by a philosophy called critical realism (Trochim, 2002). It can be

distinguished from positivism according to whether the focus is on theory verification (positivism) or on

8

theory falsification (postpositivism) (Ponterotto, 2005). Guba and Lincoln (1994) share an example to

explain this difference in which, as they put it, a million white swans cannot prove that all swans are

white, but one black swan can disprove this contention. The post-positivists, like the positivists,

believe that there is a reality independent of our thinking that can be studied through the scientific

method. Critical realism, however, recognizes that observations may involve error and that theories

can be modified (Trochim, 2002). Reality cannot be known with certainty. Observations are theory-

laden and influenced by the observer’s biases and worldview. For example, two people may observe

the same event and understand it differently, based upon their own experiences and beliefs.

Objectivity can nevertheless be achieved by using multiple measures and observations and

triangulating the data to gain a clearer understanding of what is happening in reality. It is important to

note that the post-positivists share a lot in common with positivists, but most of the research

approaches and practices in social science today fit better into the post-positivist category. In the

discussion below, the two are treated as belonging to the same family.

Assumptions about the Nature of Reality, Knowledge and Values

Let us look closely at the positivist/post-positivist assumptions about the nature of reality (ontology),

knowledge (epistemology) and values (axiology).

Ontology: On the question of what is the nature of reality, positivists hold that there is a single,

tangible reality that is relatively constant across time and setting (known as naïve realism). Part of the

researcher’s duty is to discover this reality. Positivists believe that reality is objective and independent

of the researcher’s interest in it. It is measurable and can be broken into variables. Post-positivists

concur that reality does exist but maintain that it can be known only imperfectly because of the

researcher’s human limitations (known as critical realism). The researcher can discover reality within

a certain realm of probability (Mertens, 2009; Ponterotto, 2005).

Epistemology: For the positivist, the nature of knowledge is inherent in the natural science paradigm.

Positivists view knowledge as those statements of belief or fact that can be tested empirically, can be

confirmed and verified or disconfirmed, and are stable and can be generalized (Eichelberger, 1989).

Knowledge constitutes hard data, is objective and, therefore, independent of the values, interest and

feelings of the researcher. Positivists believe that researchers only need the right data gathering

instrument or tools to produce absolute truth for a given inquiry. The research approaches are

theory falsification (postpositivism) (Ponterotto, 2005). Guba and Lincoln (1994) share an example to

explain this difference in which, as they put it, a million white swans cannot prove that all swans are

white, but one black swan can disprove this contention. The post-positivists, like the positivists,

believe that there is a reality independent of our thinking that can be studied through the scientific

method. Critical realism, however, recognizes that observations may involve error and that theories

can be modified (Trochim, 2002). Reality cannot be known with certainty. Observations are theory-

laden and influenced by the observer’s biases and worldview. For example, two people may observe

the same event and understand it differently, based upon their own experiences and beliefs.

Objectivity can nevertheless be achieved by using multiple measures and observations and

triangulating the data to gain a clearer understanding of what is happening in reality. It is important to

note that the post-positivists share a lot in common with positivists, but most of the research

approaches and practices in social science today fit better into the post-positivist category. In the

discussion below, the two are treated as belonging to the same family.

Assumptions about the Nature of Reality, Knowledge and Values

Let us look closely at the positivist/post-positivist assumptions about the nature of reality (ontology),

knowledge (epistemology) and values (axiology).

Ontology: On the question of what is the nature of reality, positivists hold that there is a single,

tangible reality that is relatively constant across time and setting (known as naïve realism). Part of the

researcher’s duty is to discover this reality. Positivists believe that reality is objective and independent

of the researcher’s interest in it. It is measurable and can be broken into variables. Post-positivists

concur that reality does exist but maintain that it can be known only imperfectly because of the

researcher’s human limitations (known as critical realism). The researcher can discover reality within

a certain realm of probability (Mertens, 2009; Ponterotto, 2005).

Epistemology: For the positivist, the nature of knowledge is inherent in the natural science paradigm.

Positivists view knowledge as those statements of belief or fact that can be tested empirically, can be

confirmed and verified or disconfirmed, and are stable and can be generalized (Eichelberger, 1989).

Knowledge constitutes hard data, is objective and, therefore, independent of the values, interest and

feelings of the researcher. Positivists believe that researchers only need the right data gathering

instrument or tools to produce absolute truth for a given inquiry. The research approaches are

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9

quantitative and include experimental, quasi-experimental, correlational, causal comparative, and

survey designs. The techniques of gathering data are mainly questionnaires, observations, tests and

experiments. Within this context, the purpose of research is to discover laws and principles that

govern the universe and to predict behaviours and situations. Post-positivists believe that perfect

objectivity cannot be achieved but is approachable.

Axiology: For the positivist, all inquiries should be value-free. The researchers should use the

scientific methods of gathering data to achieve objectivity and neutrality during the inquiry process.

Post-positivists, however, modified the belief that the researcher and the subject of study were

independent by recognizing that the theories, hypothesis and background knowledge held by the

investigator can strongly influence what is observed, how it is observed and the outcome of what is

observed.

Methodology: In the positivism/post-positivism paradigm, the purpose of research is to predict

results, test a theory, or find the strength of relationships between variables or a cause and effect

relationship. Quantitative researchers begin with ideas, theories or concepts that are defined as they

are used in the study to point to the variables of interest. The problem statement at minimum specifies

the variables to be studied and the relationship among them. Variables also are operationally defined

to enable others to replicate, verify and confirm the results. Operationally defining a variable means

that the trait to be measured is defined according to the way it is used or measured or observed in the

study. Typical methodologies include designs that are experimental, quasi-experimental, correlational,

causal comparative, quantitative and randomized control trials research. Data gathering instruments

include questionnaires, observations, experiments and tests. Chapter 8 discusses quantitative

designs in more detail.

The Constructivist/Interpretativist paradigm

Constructivism and interpretativism are related concepts that address understanding the world as

others experience it. Constructivists differ from the positivists on assumptions about the nature of

reality, what counts as knowledge and its sources, values and their role in the research process. The

constructivist approach can be traced back to Edmund Husserl’s philosophy of phenomenology (the

study of human consciousness and self-awareness; see chapters 9 and 15) and to the German

philosopher Wilhem Dilthey’s philosophy of hermeneutics (hermeneutics is the study of interpretation

and was elaborated upon in later years by Martin Heidegger and Max Weber) (Eichelberger, 1989;

quantitative and include experimental, quasi-experimental, correlational, causal comparative, and

survey designs. The techniques of gathering data are mainly questionnaires, observations, tests and

experiments. Within this context, the purpose of research is to discover laws and principles that

govern the universe and to predict behaviours and situations. Post-positivists believe that perfect

objectivity cannot be achieved but is approachable.

Axiology: For the positivist, all inquiries should be value-free. The researchers should use the

scientific methods of gathering data to achieve objectivity and neutrality during the inquiry process.

Post-positivists, however, modified the belief that the researcher and the subject of study were

independent by recognizing that the theories, hypothesis and background knowledge held by the

investigator can strongly influence what is observed, how it is observed and the outcome of what is

observed.

Methodology: In the positivism/post-positivism paradigm, the purpose of research is to predict

results, test a theory, or find the strength of relationships between variables or a cause and effect

relationship. Quantitative researchers begin with ideas, theories or concepts that are defined as they

are used in the study to point to the variables of interest. The problem statement at minimum specifies

the variables to be studied and the relationship among them. Variables also are operationally defined

to enable others to replicate, verify and confirm the results. Operationally defining a variable means

that the trait to be measured is defined according to the way it is used or measured or observed in the

study. Typical methodologies include designs that are experimental, quasi-experimental, correlational,

causal comparative, quantitative and randomized control trials research. Data gathering instruments

include questionnaires, observations, experiments and tests. Chapter 8 discusses quantitative

designs in more detail.

The Constructivist/Interpretativist paradigm

Constructivism and interpretativism are related concepts that address understanding the world as

others experience it. Constructivists differ from the positivists on assumptions about the nature of

reality, what counts as knowledge and its sources, values and their role in the research process. The

constructivist approach can be traced back to Edmund Husserl’s philosophy of phenomenology (the

study of human consciousness and self-awareness; see chapters 9 and 15) and to the German

philosopher Wilhem Dilthey’s philosophy of hermeneutics (hermeneutics is the study of interpretation

and was elaborated upon in later years by Martin Heidegger and Max Weber) (Eichelberger, 1989;

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10

Neuman, 1997). Let us examine these, and the related assumptions on ontology, epistemology,

axiology and methodologies used in the constructivist paradigm.

Ontology: On the question of what is reality, the interpretativists believe that it is socially constructed

(Creswell, 2003; Mertens, 2009) and that there are as many intangible realities as there are people

constructing them. Reality is, therefore, mind dependent and a personal or social construct. Do you

believe, for instance, that witches exist? If you do, it is your personal reality, a way in which you try to

make sense of the world around you. Reality is, in this sense, limited to context, space, time and

individuals or group in a given situation and cannot be generalized into one common reality. These

assumptions are a direct challenge to the positivist’s assumption about the existence of a tangible

external reality. The assumptions legitimize conceptions of realities from all cultures. There are

individual realities as well as group-shared realities. Of interest is how these assumptions about the

nature of reality are built into the research process.

Epistemology: Constructivists believe that knowledge is subjective, because it is socially constructed

and mind dependent. Truth lies within the human experience. Statements on what is true or false are,

therefore, culture bound, historically and context dependent, although some may be universal. Within

this context, communities’ stories, belief systems and claims of spiritual and earth connections find

space as legitimate knowledge.

Axiology: Constructivists assert that, since reality is mind constructed and mind dependent and

knowledge subjective, social inquiry is in turn value-bound and value-laden. You are inevitably

influenced by your values, which inform the paradigm you choose for inquiry, the choice of topic you

study, the methods you choose to collect and analyse data, how you interpret the findings and the

way you report the findings. As a constructivist researcher, you admit the value-laden nature of the

study and report your values and biases related to the topic under study that may interfere with

neutrality.

Methodology: The purpose of interpretative research is to understand people’s experiences. The

research takes place in a natural setting where the participants make their living. The purpose of the

study expresses the assumptions of the interpretativist researcher in attempting to understand human

experiences. Assumptions about the multiplicity of realities also inform the research process. For

instance, the research questions may not be established before the study begins but rather may

evolve as the study progresses (Mertens, 2009). The research questions are generally open-ended,

Neuman, 1997). Let us examine these, and the related assumptions on ontology, epistemology,

axiology and methodologies used in the constructivist paradigm.

Ontology: On the question of what is reality, the interpretativists believe that it is socially constructed

(Creswell, 2003; Mertens, 2009) and that there are as many intangible realities as there are people

constructing them. Reality is, therefore, mind dependent and a personal or social construct. Do you

believe, for instance, that witches exist? If you do, it is your personal reality, a way in which you try to

make sense of the world around you. Reality is, in this sense, limited to context, space, time and

individuals or group in a given situation and cannot be generalized into one common reality. These

assumptions are a direct challenge to the positivist’s assumption about the existence of a tangible

external reality. The assumptions legitimize conceptions of realities from all cultures. There are

individual realities as well as group-shared realities. Of interest is how these assumptions about the

nature of reality are built into the research process.

Epistemology: Constructivists believe that knowledge is subjective, because it is socially constructed

and mind dependent. Truth lies within the human experience. Statements on what is true or false are,

therefore, culture bound, historically and context dependent, although some may be universal. Within

this context, communities’ stories, belief systems and claims of spiritual and earth connections find

space as legitimate knowledge.

Axiology: Constructivists assert that, since reality is mind constructed and mind dependent and

knowledge subjective, social inquiry is in turn value-bound and value-laden. You are inevitably

influenced by your values, which inform the paradigm you choose for inquiry, the choice of topic you

study, the methods you choose to collect and analyse data, how you interpret the findings and the

way you report the findings. As a constructivist researcher, you admit the value-laden nature of the

study and report your values and biases related to the topic under study that may interfere with

neutrality.

Methodology: The purpose of interpretative research is to understand people’s experiences. The

research takes place in a natural setting where the participants make their living. The purpose of the

study expresses the assumptions of the interpretativist researcher in attempting to understand human

experiences. Assumptions about the multiplicity of realities also inform the research process. For

instance, the research questions may not be established before the study begins but rather may

evolve as the study progresses (Mertens, 2009). The research questions are generally open-ended,

11

descriptive and non-directional (Creswell, 2003). A typical model includes a “grand tour” question

followed by a small number of sub-questions (Spradley, 1979). The grand tour question is a statement

of the problem that is examined in the study in its broadest form, posed as a general issue, so as not

to limit the inquiry (Creswell, 2003). The sub-questions are used as guides for the methodology and

methods used to enable the researcher to answer the broad-based grand tour question.

You, the researcher, gather most of the data. In recognition of the assumption about the subjective

nature of research, you will need to describe yourself, your values, ideological biases, relationship to

the participants and closeness to the research topic. Access and entry to the study site are important

and sensitive issues that need to be addressed (Kawulich, 2011). You also have to establish trust,

rapport and authentic communication patterns with the participants so that you can capture the subtle

nuances of meaning from their voices (Denzin & Lincoln, 1998). Ethics is an important issue that the

researcher addresses throughout the study whenever it arises (cf Chapter 5). Common designs

include ethnography, phenomenology, biography, case study and grounded theory (Creswell, 2003),

several of which are discussed further in Chapter 10. Data gathering techniques are selected,

depending on the choice of design, the nature of the respondents and the research problem. They

include interviews, observations, visual aids, personal and official documents, photographs, drawings,

informal conversations, and artifacts.

Transformative/Emancipatory paradigm

There are scholars who criticize both the positivist/post-positivist and the interpretative paradigms.

Some scholars (i.e., Gillian, 1982) argue that most research studies that inform sociological and

psychological theories were developed by white male intellectuals on the basis of studying male

subjects. In the United States, African Americans argue that research-driven policies and projects

have not benefited them, because they were racially biased (Mertens, 2009). In Africa, some scholars

(e.g., Chambers, 1997; Escobar, 1995; Mshana, 1992) argue that the dominant research paradigms

have marginalized African communities’ ways of knowing and have thus led to the design of research-

driven development projects that are irrelevant to the needs of the people, a sentiment echoed by

indigenous scholars in the West (e.g., Fixico, 1998; Mihesuah, 2005). A third paradigm,

transformative or emancipatory research, which includes critical social science research (Neuman,

1997), participatory action research (Mertler, 2005; Mills, 2007; Stringer & Dwyer, 2005) and feminist

descriptive and non-directional (Creswell, 2003). A typical model includes a “grand tour” question

followed by a small number of sub-questions (Spradley, 1979). The grand tour question is a statement

of the problem that is examined in the study in its broadest form, posed as a general issue, so as not

to limit the inquiry (Creswell, 2003). The sub-questions are used as guides for the methodology and

methods used to enable the researcher to answer the broad-based grand tour question.

You, the researcher, gather most of the data. In recognition of the assumption about the subjective

nature of research, you will need to describe yourself, your values, ideological biases, relationship to

the participants and closeness to the research topic. Access and entry to the study site are important

and sensitive issues that need to be addressed (Kawulich, 2011). You also have to establish trust,

rapport and authentic communication patterns with the participants so that you can capture the subtle

nuances of meaning from their voices (Denzin & Lincoln, 1998). Ethics is an important issue that the

researcher addresses throughout the study whenever it arises (cf Chapter 5). Common designs

include ethnography, phenomenology, biography, case study and grounded theory (Creswell, 2003),

several of which are discussed further in Chapter 10. Data gathering techniques are selected,

depending on the choice of design, the nature of the respondents and the research problem. They

include interviews, observations, visual aids, personal and official documents, photographs, drawings,

informal conversations, and artifacts.

Transformative/Emancipatory paradigm

There are scholars who criticize both the positivist/post-positivist and the interpretative paradigms.

Some scholars (i.e., Gillian, 1982) argue that most research studies that inform sociological and

psychological theories were developed by white male intellectuals on the basis of studying male

subjects. In the United States, African Americans argue that research-driven policies and projects

have not benefited them, because they were racially biased (Mertens, 2009). In Africa, some scholars

(e.g., Chambers, 1997; Escobar, 1995; Mshana, 1992) argue that the dominant research paradigms

have marginalized African communities’ ways of knowing and have thus led to the design of research-

driven development projects that are irrelevant to the needs of the people, a sentiment echoed by

indigenous scholars in the West (e.g., Fixico, 1998; Mihesuah, 2005). A third paradigm,

transformative or emancipatory research, which includes critical social science research (Neuman,

1997), participatory action research (Mertler, 2005; Mills, 2007; Stringer & Dwyer, 2005) and feminist

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 22

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.