Analysis of Wine Consumption in US Restaurants: A Research Report

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/18

|19

|12097

|34

Report

AI Summary

This research report, published in the International Journal of Wine Business Research, investigates the interaction between wine involvement, dining group dynamics, and consumption behavior in US restaurants. The study, based on an online survey of 513 respondents, segments diners into low and high wine involvement categories to examine differences in dining group size, composition, wine ordering methods, choice factors, and spending habits across various restaurant categories. The findings reveal that high-involvement diners tend to dine in larger groups, order more wine, spend more money on wine, and are more likely to be the primary decision-makers for wine selection, utilizing wine menus and displays more frequently. Furthermore, they exhibit a greater discernment for wine taste, grape variety, and style. The study's practical implications offer valuable insights for the restaurant industry, providing wine-related profile descriptions for different restaurant categories to assist in the development of effective business strategies. The research contributes to the existing body of knowledge by being the first to explore these relationships, providing a framework for understanding the complex interplay of wine involvement and dining experiences in the US restaurant environment.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331355823

Wine involvement interaction with dining group dynamics, group

composition and consumption behavioural aspects in USA restaurant

Article in International Journal of Wine Business Research · February 2019

DOI: 10.1108/IJWBR-06-2018-0027

CITATIONS

0

READS

55

3 authors, including:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

The cellar door as catalyst for wine consumption changes and multiplier of sales in the Australian wine marketView project

Adaptation to climate change in Mekong Delta, VietnamView project

Johan Bruwer

University of South Australia

137PUBLICATIONS3,386CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Wine involvement interaction with dining group dynamics, group

composition and consumption behavioural aspects in USA restaurant

Article in International Journal of Wine Business Research · February 2019

DOI: 10.1108/IJWBR-06-2018-0027

CITATIONS

0

READS

55

3 authors, including:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

The cellar door as catalyst for wine consumption changes and multiplier of sales in the Australian wine marketView project

Adaptation to climate change in Mekong Delta, VietnamView project

Johan Bruwer

University of South Australia

137PUBLICATIONS3,386CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

International Journal of Wine Business Research

Wine involvement interaction with dining group dynamics, group composition and

consumption behavioural aspects in USA restaurants

Johan Bruwer, Justin Cohen, Kathleen Kelley,

Article information:

To cite this document:

Johan Bruwer, Justin Cohen, Kathleen Kelley, (2019) "Wine involvement interaction with dining

group dynamics, group composition and consumption behavioural aspects in USA restaurants",

International Journal of Wine Business Research, Vol. 31 Issue: 1, pp.12-28, https://doi.org/10.1108/

IJWBR-06-2018-0027

Permanent link to this document:

https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWBR-06-2018-0027

Downloaded on: 11 April 2019, At: 17:53 (PT)

References: this document contains references to 49 other documents.

To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com

The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 31 times since 2019*

Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:

(2018),"New approach to segmenting tourists in a German wine region", International Journal

of Wine Business Research, Vol. 30 Iss 2 pp. 153-168 <a href="https://doi.org/10.1108/

IJWBR-07-2017-0044">https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWBR-07-2017-0044</a>

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by emerald-

srm:416658 []

For Authors

If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emera

for Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submis

guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more informa

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The compa

manages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes

well as providing an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and

services.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the

Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for

digital archive preservation.

*Related content and download information correct at time of download.

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

Wine involvement interaction with dining group dynamics, group composition and

consumption behavioural aspects in USA restaurants

Johan Bruwer, Justin Cohen, Kathleen Kelley,

Article information:

To cite this document:

Johan Bruwer, Justin Cohen, Kathleen Kelley, (2019) "Wine involvement interaction with dining

group dynamics, group composition and consumption behavioural aspects in USA restaurants",

International Journal of Wine Business Research, Vol. 31 Issue: 1, pp.12-28, https://doi.org/10.1108/

IJWBR-06-2018-0027

Permanent link to this document:

https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWBR-06-2018-0027

Downloaded on: 11 April 2019, At: 17:53 (PT)

References: this document contains references to 49 other documents.

To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com

The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 31 times since 2019*

Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:

(2018),"New approach to segmenting tourists in a German wine region", International Journal

of Wine Business Research, Vol. 30 Iss 2 pp. 153-168 <a href="https://doi.org/10.1108/

IJWBR-07-2017-0044">https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWBR-07-2017-0044</a>

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by emerald-

srm:416658 []

For Authors

If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emera

for Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submis

guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more informa

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The compa

manages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes

well as providing an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and

services.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the

Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for

digital archive preservation.

*Related content and download information correct at time of download.

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

Wine involvement interaction

with dining group dynamics, group

composition and consumption

behavioural aspects in

USA restaurants

Johan Bruwer and Justin Cohen

School of Marketing, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia, an

Kathleen Kelley

Department of Plant Science, The Pennsylvania State University, University

Pennsylvania, USA

Abstract

Purpose –The importance of the wine involvement construct in explaining consumers’ wine consu

behaviour is widely acknowledged in the literature, as is the social nature of dining out with others

is a paucity of research examining the relationships between how this construct interacts with din

dynamics and wine consumption behaviouralaspects in the restaurant environment.This study aims to

investigate these aspects in US restaurants.

Design/methodology/approach –Utilising an online survey that yielded a sampleof 513

respondentsfrom across the USA who frequentedall the recognisedrestaurantcategories,

respondents are segmented into low and high wine involvementcategories using a reliable wine

involvement scale.The authors examine differences between various dining group dynamics,dining

group composition,main choice factors when ordering wine and method ofordering wine in US

restaurants.

Findings –The authors find that diners’ level of involvement with wine provides sharp insights into

significant differences between involvement and dining group dynamics,group composition,choice factors

when ordering wine and method of ordering wine in restaurants. High involvement diners dine out

groups, order more wine, spend more money on wine, are more often the main decision-maker or

for the dining group and use wine menus and wallboard displays more often when ordering than low

involvement diners.They are also more discerning about the taste of wine,grape variety and wine style in

terms of choice factors when ordering.

Practical implications –The nature and dynamics of dining groups are aspects that have profound

implications, in various ways, for the restaurant industry. The level of involvement diners have wit

strong predictor of various outcomes in terms of dining group behavioural aspects regarding wineWine-

related restaurant category-specific profile descriptions, such as those developed in this study, ca

for restaurants when creating business strategies.

Originality/value – The authors make a substantive contribution by being the firststudy to

examinethe relationshipsbetweendining group dynamics,dining group compositionand

behaviouralaspects concerning wine consumption and involvement in the restaurant environment.

The authors then map this information to derive wine-related profile descriptions for all US restau

categories.

Keywords Market segmentation, Conceptual/theoretical, Wines, Consumer behaviour,

Survey research, Scale development/testing

Paper type Research paper

IJWBR

31,1

12

Received 16 June 2018

Revised 20 August 2018

Accepted 17 September 2018

International Journal of Wine

Business Research

Vol. 31 No. 1, 2019

pp.12-28

© Emerald Publishing Limited

1751-1062

DOI 10.1108/IJWBR-06-2018-0027

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at:

www.emeraldinsight.com/1751-1062.htm

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

with dining group dynamics, group

composition and consumption

behavioural aspects in

USA restaurants

Johan Bruwer and Justin Cohen

School of Marketing, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia, an

Kathleen Kelley

Department of Plant Science, The Pennsylvania State University, University

Pennsylvania, USA

Abstract

Purpose –The importance of the wine involvement construct in explaining consumers’ wine consu

behaviour is widely acknowledged in the literature, as is the social nature of dining out with others

is a paucity of research examining the relationships between how this construct interacts with din

dynamics and wine consumption behaviouralaspects in the restaurant environment.This study aims to

investigate these aspects in US restaurants.

Design/methodology/approach –Utilising an online survey that yielded a sampleof 513

respondentsfrom across the USA who frequentedall the recognisedrestaurantcategories,

respondents are segmented into low and high wine involvementcategories using a reliable wine

involvement scale.The authors examine differences between various dining group dynamics,dining

group composition,main choice factors when ordering wine and method ofordering wine in US

restaurants.

Findings –The authors find that diners’ level of involvement with wine provides sharp insights into

significant differences between involvement and dining group dynamics,group composition,choice factors

when ordering wine and method of ordering wine in restaurants. High involvement diners dine out

groups, order more wine, spend more money on wine, are more often the main decision-maker or

for the dining group and use wine menus and wallboard displays more often when ordering than low

involvement diners.They are also more discerning about the taste of wine,grape variety and wine style in

terms of choice factors when ordering.

Practical implications –The nature and dynamics of dining groups are aspects that have profound

implications, in various ways, for the restaurant industry. The level of involvement diners have wit

strong predictor of various outcomes in terms of dining group behavioural aspects regarding wineWine-

related restaurant category-specific profile descriptions, such as those developed in this study, ca

for restaurants when creating business strategies.

Originality/value – The authors make a substantive contribution by being the firststudy to

examinethe relationshipsbetweendining group dynamics,dining group compositionand

behaviouralaspects concerning wine consumption and involvement in the restaurant environment.

The authors then map this information to derive wine-related profile descriptions for all US restau

categories.

Keywords Market segmentation, Conceptual/theoretical, Wines, Consumer behaviour,

Survey research, Scale development/testing

Paper type Research paper

IJWBR

31,1

12

Received 16 June 2018

Revised 20 August 2018

Accepted 17 September 2018

International Journal of Wine

Business Research

Vol. 31 No. 1, 2019

pp.12-28

© Emerald Publishing Limited

1751-1062

DOI 10.1108/IJWBR-06-2018-0027

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at:

www.emeraldinsight.com/1751-1062.htm

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

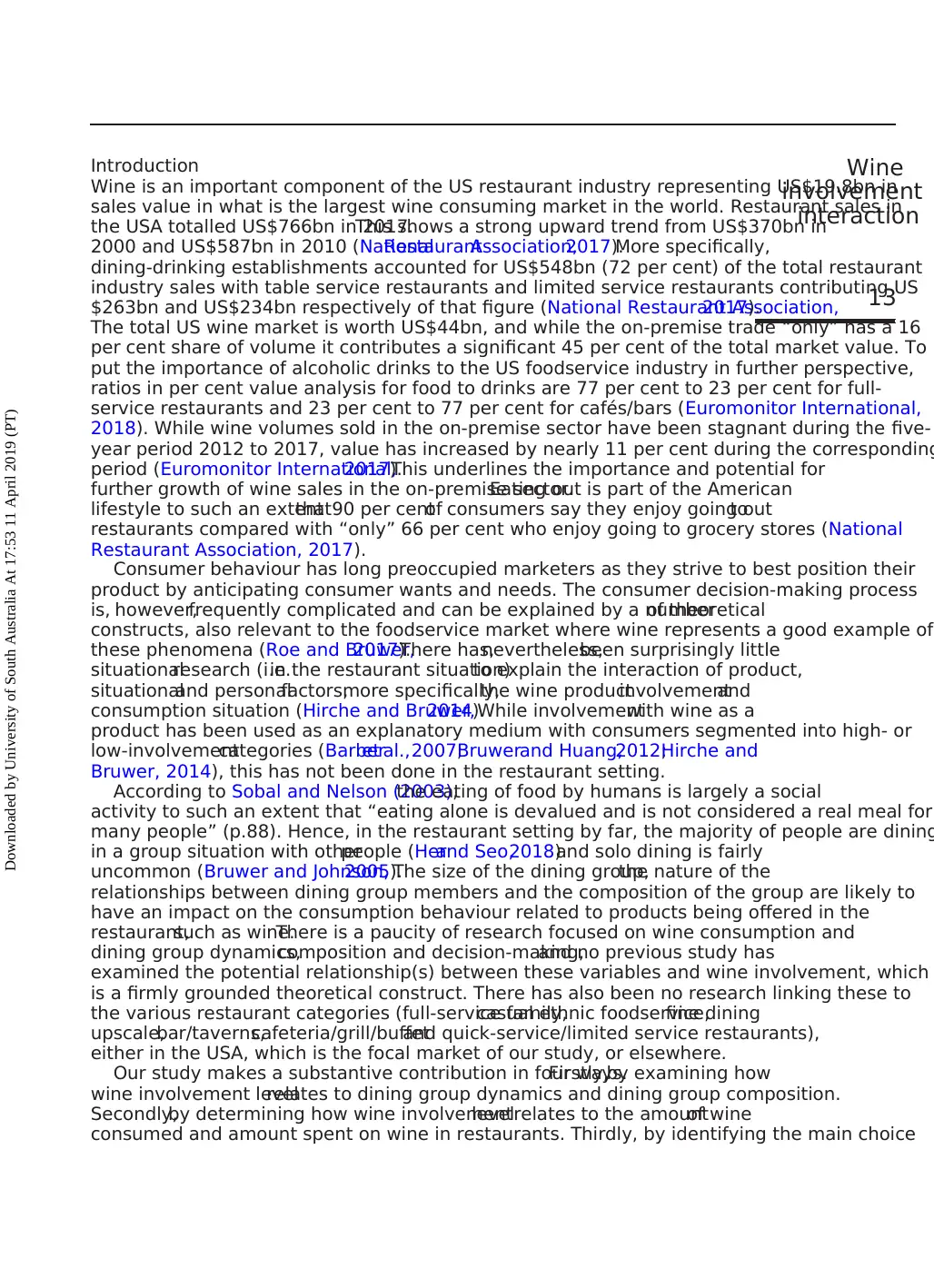

Introduction

Wine is an important component of the US restaurant industry representing US$19.8bn in

sales value in what is the largest wine consuming market in the world. Restaurant sales in

the USA totalled US$766bn in 2017.This shows a strong upward trend from US$370bn in

2000 and US$587bn in 2010 (NationalRestaurantAssociation,2017).More specifically,

dining-drinking establishments accounted for US$548bn (72 per cent) of the total restaurant

industry sales with table service restaurants and limited service restaurants contributing US

$263bn and US$234bn respectively of that figure (National Restaurant Association,2017).

The total US wine market is worth US$44bn, and while the on-premise trade “only” has a 16

per cent share of volume it contributes a significant 45 per cent of the total market value. To

put the importance of alcoholic drinks to the US foodservice industry in further perspective,

ratios in per cent value analysis for food to drinks are 77 per cent to 23 per cent for full-

service restaurants and 23 per cent to 77 per cent for cafés/bars (Euromonitor International,

2018). While wine volumes sold in the on-premise sector have been stagnant during the five-

year period 2012 to 2017, value has increased by nearly 11 per cent during the corresponding

period (Euromonitor International,2017).This underlines the importance and potential for

further growth of wine sales in the on-premise sector.Eating out is part of the American

lifestyle to such an extentthat90 per centof consumers say they enjoy going outto

restaurants compared with “only” 66 per cent who enjoy going to grocery stores (National

Restaurant Association, 2017).

Consumer behaviour has long preoccupied marketers as they strive to best position their

product by anticipating consumer wants and needs. The consumer decision-making process

is, however,frequently complicated and can be explained by a numberof theoretical

constructs, also relevant to the foodservice market where wine represents a good example of

these phenomena (Roe and Bruwer,2017).There has,nevertheless,been surprisingly little

situationalresearch (i.e.in the restaurant situation)to explain the interaction of product,

situationaland personalfactors,more specifically,the wine productinvolvementand

consumption situation (Hirche and Bruwer,2014).While involvementwith wine as a

product has been used as an explanatory medium with consumers segmented into high- or

low-involvementcategories (Barberet al.,2007;Bruwerand Huang,2012;Hirche and

Bruwer, 2014), this has not been done in the restaurant setting.

According to Sobal and Nelson (2003),the eating of food by humans is largely a social

activity to such an extent that “eating alone is devalued and is not considered a real meal for

many people” (p.88). Hence, in the restaurant setting by far, the majority of people are dining

in a group situation with otherpeople (Herand Seo,2018)and solo dining is fairly

uncommon (Bruwer and Johnson,2005).The size of the dining group,the nature of the

relationships between dining group members and the composition of the group are likely to

have an impact on the consumption behaviour related to products being offered in the

restaurant,such as wine.There is a paucity of research focused on wine consumption and

dining group dynamics,composition and decision-making,and no previous study has

examined the potential relationship(s) between these variables and wine involvement, which

is a firmly grounded theoretical construct. There has also been no research linking these to

the various restaurant categories (full-service family,casual ethnic foodservice,fine dining

upscale,bar/taverns,cafeteria/grill/buffetand quick-service/limited service restaurants),

either in the USA, which is the focal market of our study, or elsewhere.

Our study makes a substantive contribution in four ways.Firstly,by examining how

wine involvement levelrelates to dining group dynamics and dining group composition.

Secondly,by determining how wine involvementlevelrelates to the amountof wine

consumed and amount spent on wine in restaurants. Thirdly, by identifying the main choice

Wine

involvement

interaction

13

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

Wine is an important component of the US restaurant industry representing US$19.8bn in

sales value in what is the largest wine consuming market in the world. Restaurant sales in

the USA totalled US$766bn in 2017.This shows a strong upward trend from US$370bn in

2000 and US$587bn in 2010 (NationalRestaurantAssociation,2017).More specifically,

dining-drinking establishments accounted for US$548bn (72 per cent) of the total restaurant

industry sales with table service restaurants and limited service restaurants contributing US

$263bn and US$234bn respectively of that figure (National Restaurant Association,2017).

The total US wine market is worth US$44bn, and while the on-premise trade “only” has a 16

per cent share of volume it contributes a significant 45 per cent of the total market value. To

put the importance of alcoholic drinks to the US foodservice industry in further perspective,

ratios in per cent value analysis for food to drinks are 77 per cent to 23 per cent for full-

service restaurants and 23 per cent to 77 per cent for cafés/bars (Euromonitor International,

2018). While wine volumes sold in the on-premise sector have been stagnant during the five-

year period 2012 to 2017, value has increased by nearly 11 per cent during the corresponding

period (Euromonitor International,2017).This underlines the importance and potential for

further growth of wine sales in the on-premise sector.Eating out is part of the American

lifestyle to such an extentthat90 per centof consumers say they enjoy going outto

restaurants compared with “only” 66 per cent who enjoy going to grocery stores (National

Restaurant Association, 2017).

Consumer behaviour has long preoccupied marketers as they strive to best position their

product by anticipating consumer wants and needs. The consumer decision-making process

is, however,frequently complicated and can be explained by a numberof theoretical

constructs, also relevant to the foodservice market where wine represents a good example of

these phenomena (Roe and Bruwer,2017).There has,nevertheless,been surprisingly little

situationalresearch (i.e.in the restaurant situation)to explain the interaction of product,

situationaland personalfactors,more specifically,the wine productinvolvementand

consumption situation (Hirche and Bruwer,2014).While involvementwith wine as a

product has been used as an explanatory medium with consumers segmented into high- or

low-involvementcategories (Barberet al.,2007;Bruwerand Huang,2012;Hirche and

Bruwer, 2014), this has not been done in the restaurant setting.

According to Sobal and Nelson (2003),the eating of food by humans is largely a social

activity to such an extent that “eating alone is devalued and is not considered a real meal for

many people” (p.88). Hence, in the restaurant setting by far, the majority of people are dining

in a group situation with otherpeople (Herand Seo,2018)and solo dining is fairly

uncommon (Bruwer and Johnson,2005).The size of the dining group,the nature of the

relationships between dining group members and the composition of the group are likely to

have an impact on the consumption behaviour related to products being offered in the

restaurant,such as wine.There is a paucity of research focused on wine consumption and

dining group dynamics,composition and decision-making,and no previous study has

examined the potential relationship(s) between these variables and wine involvement, which

is a firmly grounded theoretical construct. There has also been no research linking these to

the various restaurant categories (full-service family,casual ethnic foodservice,fine dining

upscale,bar/taverns,cafeteria/grill/buffetand quick-service/limited service restaurants),

either in the USA, which is the focal market of our study, or elsewhere.

Our study makes a substantive contribution in four ways.Firstly,by examining how

wine involvement levelrelates to dining group dynamics and dining group composition.

Secondly,by determining how wine involvementlevelrelates to the amountof wine

consumed and amount spent on wine in restaurants. Thirdly, by identifying the main choice

Wine

involvement

interaction

13

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

factorsused by low-versushigh-involvementconsumerswhen ordering winein a

restaurant and method(s) of ordering it. Finally, it provides a wine-related profiling

grid for all restaurant categories in the US market.

Literature review

There has been a multitude ofresearch studies focusing on wine in the hospitality

environment,specifically within the restaurant domain.These include,but are not limited

to, wine service training (Gultek et al., 2005); wine menu/list design (Barth, 2011; B

et al.,2009;Gil et al.,2009;McCall and Lynn,2008),wine origin (Bruwer et al.,2012),risk

perception and risk reduction (Bruwer et al., 2017a; Lacey et al., 2009; Terrier and

2016),and wine involvement (Barber etal.,2007;Bruwer and Huang,2012;Hirche and

Bruwer,2014;Hollebeek and Brodie,2009;Roe and Bruwer,2017).Despite some advocacy

for marketsegmentation based on consumers’wine involvement(Barberet al.,2007;

Lesschaeve and Bruwer,2010),no previous study has focused solely on diners in the

restaurant environment and explored relationships between involvement, dining gr

and composition, etc.

Role of wine in restaurants

Wine is widely served as a food accompanimentin restaurants.It is also a generally

accepted fact that the sale of wine can add significantly to a restaurant’s profitabili

2011; Berenguer et al., 2009; Frost, 2015; Gil et al., 2009; Hansen, 2015; Wansink

For example, in Australia, profitability varies between 26 per cent and 29 per cent (

and Johnson,2005;Bruwer et al.,2012),and in Spain,it accounts for 32 per cent of the

average restaurant bill(Gilet al.,2009).However,studies have discovered that selecting

wine in a restaurant is associated with a stressfulexperience and has an associated risk

perception (Bruwer et al., 2017a; Lacey et al., 2009). Nevertheless, surprisingly litt

has been conducted on illuminating various aspects of the dining occasion and spe

the dining group,method of ordering wine,choice factors and wine involvement level,as

these relate to wine consumption in restaurants.

Wine product involvement and wine purchasing

The historical roots of the involvement construct can be found many decades ago i

psychology,but it was not untilthe mid-1980s that researchers began to understand the

importance of studying this construct for the purpose of segmenting markets (Less

and Bruwer,2010).It has been described as “a person’s perceived relevance of the ob

based on inherent values,needs and interests” (Zaichkowsky,1985,p. 342).Much of the

initialinvolvementresearch focused on its role in advertising (Celsiand Olson,1988;

Laurentand Kapferer,1985).Since then,the involvementconstructhas received much

attention due to its significantinfluence on consumer purchasing behaviour (Dholakia,

2001).

Although involvement theory views consumer behaviour as a continuum coverin

range of cognitive and behaviouralprocesses (Barber et al.,2009,p. 61),from early on,

researchers (Bloch, 1981; Bloch and Richins, 1983; Celsi and Olson, 1988; Richins e

distinguished between enduring involvement and situational involvement in the pro

studying involvement.In its simplestform,a primary distinction between enduring

involvement and situationalinvolvement is temporalduration (Richins and Bloch,1986).

Enduring involvementis a ratherstable phenomenon thatrepresents the consumer’s

personalinterest in the productclass over a long period (Park etal.,2013).Situational

involvement,on the other hand,is the temporary arousalof a consumer’s interest that

IJWBR

31,1

14

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

restaurant and method(s) of ordering it. Finally, it provides a wine-related profiling

grid for all restaurant categories in the US market.

Literature review

There has been a multitude ofresearch studies focusing on wine in the hospitality

environment,specifically within the restaurant domain.These include,but are not limited

to, wine service training (Gultek et al., 2005); wine menu/list design (Barth, 2011; B

et al.,2009;Gil et al.,2009;McCall and Lynn,2008),wine origin (Bruwer et al.,2012),risk

perception and risk reduction (Bruwer et al., 2017a; Lacey et al., 2009; Terrier and

2016),and wine involvement (Barber etal.,2007;Bruwer and Huang,2012;Hirche and

Bruwer,2014;Hollebeek and Brodie,2009;Roe and Bruwer,2017).Despite some advocacy

for marketsegmentation based on consumers’wine involvement(Barberet al.,2007;

Lesschaeve and Bruwer,2010),no previous study has focused solely on diners in the

restaurant environment and explored relationships between involvement, dining gr

and composition, etc.

Role of wine in restaurants

Wine is widely served as a food accompanimentin restaurants.It is also a generally

accepted fact that the sale of wine can add significantly to a restaurant’s profitabili

2011; Berenguer et al., 2009; Frost, 2015; Gil et al., 2009; Hansen, 2015; Wansink

For example, in Australia, profitability varies between 26 per cent and 29 per cent (

and Johnson,2005;Bruwer et al.,2012),and in Spain,it accounts for 32 per cent of the

average restaurant bill(Gilet al.,2009).However,studies have discovered that selecting

wine in a restaurant is associated with a stressfulexperience and has an associated risk

perception (Bruwer et al., 2017a; Lacey et al., 2009). Nevertheless, surprisingly litt

has been conducted on illuminating various aspects of the dining occasion and spe

the dining group,method of ordering wine,choice factors and wine involvement level,as

these relate to wine consumption in restaurants.

Wine product involvement and wine purchasing

The historical roots of the involvement construct can be found many decades ago i

psychology,but it was not untilthe mid-1980s that researchers began to understand the

importance of studying this construct for the purpose of segmenting markets (Less

and Bruwer,2010).It has been described as “a person’s perceived relevance of the ob

based on inherent values,needs and interests” (Zaichkowsky,1985,p. 342).Much of the

initialinvolvementresearch focused on its role in advertising (Celsiand Olson,1988;

Laurentand Kapferer,1985).Since then,the involvementconstructhas received much

attention due to its significantinfluence on consumer purchasing behaviour (Dholakia,

2001).

Although involvement theory views consumer behaviour as a continuum coverin

range of cognitive and behaviouralprocesses (Barber et al.,2009,p. 61),from early on,

researchers (Bloch, 1981; Bloch and Richins, 1983; Celsi and Olson, 1988; Richins e

distinguished between enduring involvement and situational involvement in the pro

studying involvement.In its simplestform,a primary distinction between enduring

involvement and situationalinvolvement is temporalduration (Richins and Bloch,1986).

Enduring involvementis a ratherstable phenomenon thatrepresents the consumer’s

personalinterest in the productclass over a long period (Park etal.,2013).Situational

involvement,on the other hand,is the temporary arousalof a consumer’s interest that

IJWBR

31,1

14

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

fluctuates,usually within the timeframe of a purchase decision (Park et al.,2013),such as

ordering a bottle of wine or wine by-the-glass (WBG) from a restaurant’s wine list when

dining there (Bruwer and Cohen,2019).Situationalinvolvementis the outcome ofthe

consumer’s interaction with the productand the purchase situation.It is an incorrect

assumption that a consumer with low involvement in a certain product would always put

little effort in purchasing (Hirche and Bruwer, 2014).

Both enduring and situationalinvolvementrepresentstates ofarousaland product

interest.Both also have similar behaviouraloutcomes such as information search and

dissemination (Ogbeide and Bruwer,2013;Richins and Bloch,1986).There is considerable

evidence that information seeking is used mainly as a risk-reduction strategy in response to

risk perceptions and has been identified as an important risk-reduction strategy in wine

purchasing (Bruwer et al.,2017a).In the current study,we examine methods of ordering

wine using information (i.e. wine menus, table talkers, etc.) provided in restaurants.

Wine has long been regarded as a product category well suited to involvement research

with the firstwine-specific involvementstudy executed by Zaichkowsky (1985).Not

surprisingly, research has identified involvement as an important variable that has a certain

impact upon consumer behaviour in the wine market (Lesschaeve and Bruwer, 2010). Wine

involvement has been loosely referred to as one’s personal involvement with wine (Barber

et al., 2007) and the demonstrated relevance of involvement in wine purchasing is supported

by several studies (Barber et al.,2007;Bruwer and Buller,2013;Bruwer and Huang,2012;

Hirche and Bruwer, 2014; Ogbeide and Bruwer, 2013). Involvement has also been linked to

wine buying and it has been shown that consumers with different levels of involvement

behave differently (Bruwer and Huang, 2012; Hirche and Bruwer, 2014). Zaichkowsky (1985)

is of the opinion that the use of key attributes such as grape variety,region of origin and

price is influenced by involvement.There is,nevertheless,a dearth of research examining

the role of wine involvement in the restaurant environment among diners and how this

relates to aspects such as dining group behaviour and decision-making.

Dining group dynamics and composition

The literature emphasises that communal eating and sharing mealtimes with other people is

a deeply embedded human behaviour (Sobal and Nelson, 2003). Unsurprisingly, the intense

social nature of dining out in restaurants has,thus,been well documented (Alonso et al.,

2013; Bruwer and Johnson, 2005; Her and Seo, 2018; Sun and Morrison, 2007). Moreover, in a

service environmentsuch as restaurants,other individuals have been highlighted as a

crucialhuman factor,influencing consumers’affective and cognitive responses (Her and

Seo,2018;Liu and Mattila,2015).People form their self-concept (Roe and Bruwer,2017)

according to the social identity theory and also the social categorization theory with respect

to which social groups or categories the individual belongs to,is affiliated with and feels

psychologically connected to (White and Dahl, 2007).

In response to the question if the presence of others affects how much other people eat,

Herman, Roth and Polivy (2003, p. 873) go as far as to emphatically answer “definitely yes”.

However, depending on the explanatory theory used to understand such behaviour, people

eat either more or less when dining in the company of others depending on the amounts their

dining companions eat(Herman etal.,2003).Whilst severalstudies (Dibb-Smith and

Brindal,2015;Polivy and Pliner,2015;Salvy et al.,2007) examined and made conclusions

about the effects of group dynamics and composition (also known as socialfacilitation

theory)on food consumption,thereis a lack of similarresearch focused on wine

consumption in restaurants.

Wine

involvement

interaction

15

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

ordering a bottle of wine or wine by-the-glass (WBG) from a restaurant’s wine list when

dining there (Bruwer and Cohen,2019).Situationalinvolvementis the outcome ofthe

consumer’s interaction with the productand the purchase situation.It is an incorrect

assumption that a consumer with low involvement in a certain product would always put

little effort in purchasing (Hirche and Bruwer, 2014).

Both enduring and situationalinvolvementrepresentstates ofarousaland product

interest.Both also have similar behaviouraloutcomes such as information search and

dissemination (Ogbeide and Bruwer,2013;Richins and Bloch,1986).There is considerable

evidence that information seeking is used mainly as a risk-reduction strategy in response to

risk perceptions and has been identified as an important risk-reduction strategy in wine

purchasing (Bruwer et al.,2017a).In the current study,we examine methods of ordering

wine using information (i.e. wine menus, table talkers, etc.) provided in restaurants.

Wine has long been regarded as a product category well suited to involvement research

with the firstwine-specific involvementstudy executed by Zaichkowsky (1985).Not

surprisingly, research has identified involvement as an important variable that has a certain

impact upon consumer behaviour in the wine market (Lesschaeve and Bruwer, 2010). Wine

involvement has been loosely referred to as one’s personal involvement with wine (Barber

et al., 2007) and the demonstrated relevance of involvement in wine purchasing is supported

by several studies (Barber et al.,2007;Bruwer and Buller,2013;Bruwer and Huang,2012;

Hirche and Bruwer, 2014; Ogbeide and Bruwer, 2013). Involvement has also been linked to

wine buying and it has been shown that consumers with different levels of involvement

behave differently (Bruwer and Huang, 2012; Hirche and Bruwer, 2014). Zaichkowsky (1985)

is of the opinion that the use of key attributes such as grape variety,region of origin and

price is influenced by involvement.There is,nevertheless,a dearth of research examining

the role of wine involvement in the restaurant environment among diners and how this

relates to aspects such as dining group behaviour and decision-making.

Dining group dynamics and composition

The literature emphasises that communal eating and sharing mealtimes with other people is

a deeply embedded human behaviour (Sobal and Nelson, 2003). Unsurprisingly, the intense

social nature of dining out in restaurants has,thus,been well documented (Alonso et al.,

2013; Bruwer and Johnson, 2005; Her and Seo, 2018; Sun and Morrison, 2007). Moreover, in a

service environmentsuch as restaurants,other individuals have been highlighted as a

crucialhuman factor,influencing consumers’affective and cognitive responses (Her and

Seo,2018;Liu and Mattila,2015).People form their self-concept (Roe and Bruwer,2017)

according to the social identity theory and also the social categorization theory with respect

to which social groups or categories the individual belongs to,is affiliated with and feels

psychologically connected to (White and Dahl, 2007).

In response to the question if the presence of others affects how much other people eat,

Herman, Roth and Polivy (2003, p. 873) go as far as to emphatically answer “definitely yes”.

However, depending on the explanatory theory used to understand such behaviour, people

eat either more or less when dining in the company of others depending on the amounts their

dining companions eat(Herman etal.,2003).Whilst severalstudies (Dibb-Smith and

Brindal,2015;Polivy and Pliner,2015;Salvy et al.,2007) examined and made conclusions

about the effects of group dynamics and composition (also known as socialfacilitation

theory)on food consumption,thereis a lack of similarresearch focused on wine

consumption in restaurants.

Wine

involvement

interaction

15

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Given the general consensus that the majority of people dine out in restaurants

situation and the fact that the very nature of wine consumption is highly social(Bruwer

et al., 2012), we combine this with the fact that people with high wine involvement

highly likely to provide information about wine to others. Considering that people w

both a high involvement in and expertise of the wine product category are likely to

impress others (Roe and Bruwer, 2017; Hollebeek and Brodie, 2009; Lesschaeve an

2010), we derive the study’s first hypothesis and postulate that:

H1. Diners with a high level of wine involvement are more likely to be part of a la

dining group than those with a low wine involvement level.

Another aspect to consider when examining the nature of the dining group is the ty

relationship(s) a focal person has with the other group members.This can range between

extremes from a close spousalrelationship to a complete stranger such as a potential

business associate who is being met for the first time. In between the two, there ar

less close relationships such as with family, friends and work colleagues and combi

thereof, depending on the size of the dining group. There exists a dearth of informa

provides guidance regarding the potential setting of a hypothesis to direct the exam

of the nature of the relationship between group members and wine involvement le

we also set no specific hypothesis in this regard. We, nevertheless, examine this as

a view to providing direction for future studies to set hypotheses and add to the the

Quantity consumed and amount of money spent on wine

Although the group context is widely acknowledged as influencing quantity of food

and consumed (Alonso et al., 2013; Dibb-Smith and Brindal, 2015; Her and Seo, 2018;

and Pliner,2015),no similar study has been executed to examine wine ordering and

consumption in the contextof restaurants.This lack ofinformation relating to group

dynamics when considering wine in restaurants include baseline metrics such as th

the dining group. Our study contributes by examining these aspects.

When considering whether involvement level affects the quantity of wine consum

the amount of money spent on wine,there is a body of evidence confirming that high-

involvement wine drinkers spend more money on wine and consume larger quantit

low involvement drinkers (Barber et al., 2007; Bruwer and Huang, 2012; Gultek et a

Hirche and Bruwer, 2014). We, therefore, derive H2 and H3:

H2. Diners with a high levelof wine involvementconsume more wine than low

involvement diners when dining out in a restaurant.

H3. Diners with a high level of wine involvement spend more money on wine tha

involvement diners when dining out in a restaurant.

Decision-making, choice factors and method of ordering wine

There has also been little research on decision-making when ordering wine in a res

setting. Moreover, this decision is consistently referred to as being “complicated” (

Berenguer et al.,2009;Bruwer et al.,2017b;Bruwer and Huang,2012;Bruwer et al.,2012;

Gil et al., 2009; Lacey et al., 2009). This is not surprising, given the fact that wines

restaurant are generally not pre-viewed as they would be in a retail store, but inste

using a wine menu/list, which in a dining group situation has associated social pres

research contributes by not only identifying the incidence of primary decision-maki

IJWBR

31,1

16

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

situation and the fact that the very nature of wine consumption is highly social(Bruwer

et al., 2012), we combine this with the fact that people with high wine involvement

highly likely to provide information about wine to others. Considering that people w

both a high involvement in and expertise of the wine product category are likely to

impress others (Roe and Bruwer, 2017; Hollebeek and Brodie, 2009; Lesschaeve an

2010), we derive the study’s first hypothesis and postulate that:

H1. Diners with a high level of wine involvement are more likely to be part of a la

dining group than those with a low wine involvement level.

Another aspect to consider when examining the nature of the dining group is the ty

relationship(s) a focal person has with the other group members.This can range between

extremes from a close spousalrelationship to a complete stranger such as a potential

business associate who is being met for the first time. In between the two, there ar

less close relationships such as with family, friends and work colleagues and combi

thereof, depending on the size of the dining group. There exists a dearth of informa

provides guidance regarding the potential setting of a hypothesis to direct the exam

of the nature of the relationship between group members and wine involvement le

we also set no specific hypothesis in this regard. We, nevertheless, examine this as

a view to providing direction for future studies to set hypotheses and add to the the

Quantity consumed and amount of money spent on wine

Although the group context is widely acknowledged as influencing quantity of food

and consumed (Alonso et al., 2013; Dibb-Smith and Brindal, 2015; Her and Seo, 2018;

and Pliner,2015),no similar study has been executed to examine wine ordering and

consumption in the contextof restaurants.This lack ofinformation relating to group

dynamics when considering wine in restaurants include baseline metrics such as th

the dining group. Our study contributes by examining these aspects.

When considering whether involvement level affects the quantity of wine consum

the amount of money spent on wine,there is a body of evidence confirming that high-

involvement wine drinkers spend more money on wine and consume larger quantit

low involvement drinkers (Barber et al., 2007; Bruwer and Huang, 2012; Gultek et a

Hirche and Bruwer, 2014). We, therefore, derive H2 and H3:

H2. Diners with a high levelof wine involvementconsume more wine than low

involvement diners when dining out in a restaurant.

H3. Diners with a high level of wine involvement spend more money on wine tha

involvement diners when dining out in a restaurant.

Decision-making, choice factors and method of ordering wine

There has also been little research on decision-making when ordering wine in a res

setting. Moreover, this decision is consistently referred to as being “complicated” (

Berenguer et al.,2009;Bruwer et al.,2017b;Bruwer and Huang,2012;Bruwer et al.,2012;

Gil et al., 2009; Lacey et al., 2009). This is not surprising, given the fact that wines

restaurant are generally not pre-viewed as they would be in a retail store, but inste

using a wine menu/list, which in a dining group situation has associated social pres

research contributes by not only identifying the incidence of primary decision-maki

IJWBR

31,1

16

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ordering wine, but also by pinpointing the socio-demographics of the decision-maker within th

dining group. Firm theoretical grounding is provided by anchoring this aspect within the wine

involvement construct from which we derive H4:

H4: Diners with a high level of wine involvement are more often the main decision-

makerwhen ordering winein a restaurantthan thosewith a low wine

involvement level.

It stands to reason that the previously discussed social cues and group pressures affect

behaviour in the restaurant environment (Dibb-Smith and Brindal,2015;Herman et al.,

2003),even more so when wine involvement levelis considered to be an independent

variable. More specifically, the effect on the diners’ ordering method of wine (Barth, 2011)

and the main choice factors used when ordering wine (Lacey etal.,2009)should be

considered.Amongst the choice factors when selecting wine,taste,wine style (i.e.red or

white)and grape variety (i.e.CabernetSauvignon or Chardonnay)and price tend to

dominate the decision (Bruwer and Johnson,2005;Lacey et al.,2009).Through H5,H6

and H7, we therefore postulate that:

H5. Diners with a high level of wine involvement are more likely to use the wine menu

when ordering wine in a restaurant than those with a low wine involvement level.

H6. Diners with a low level of wine involvement are more likely to use the advice of

service staffwhen ordering wine in a restaurantthan those with a high wine

involvement level.

H7. Diners with a high level of wine involvement are more likely to use the taste of wine,

wine style and grape variety as the main choice factors when ordering wine in a

restaurant than those with a low wine involvement level.

Methodology

The main aim of this study is to identify how diners’ involvement with wine impacts their

wine consumption behaviour when dining in US restaurants and how this relates to the

nature, composition and size of their dining group. During the operalisation process, a scale

was designedfor measuringthe diners’wine involvementlevel.To date,most

wine involvement studies either developed/used scales that measured only the enduring

wine involvementconstruct(Barber etal.,2007;Bruwer and Buller,2013;Bruwer and

Huang,2012;Hirche and Bruwer,2014;Hollebeek and Brodie,2009).In the restaurant

context,which is very situation-specific,it is essentialthatthe (temporal)situational

involvement construct also be incorporated in the measurement of wine involvement. A five-

item involvement scale developed by Dholakia (2001) brought together both components of

involvement and delivered robust results. Therefore, given the fact that no similar scale with

wine as product focus has been developed, we adopted Dholakia’s (2001) scale and adjusted

it to wine as a productand restaurants as its situation-specific context.As far as the

practicalimplications ofthis study are concerned,the main aim is to develop profile

descriptions, informed by the study’s findings, for all US restaurant categories.

Sample

An online survey was executed in the USA by engaging a professionalconsumer panel

company involving people of legal drinking age (21 years and older) who consumed wine

and had dined out at least once during the previous month at any one of the US restaurant

Wine

involvement

interaction

17

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

dining group. Firm theoretical grounding is provided by anchoring this aspect within the wine

involvement construct from which we derive H4:

H4: Diners with a high level of wine involvement are more often the main decision-

makerwhen ordering winein a restaurantthan thosewith a low wine

involvement level.

It stands to reason that the previously discussed social cues and group pressures affect

behaviour in the restaurant environment (Dibb-Smith and Brindal,2015;Herman et al.,

2003),even more so when wine involvement levelis considered to be an independent

variable. More specifically, the effect on the diners’ ordering method of wine (Barth, 2011)

and the main choice factors used when ordering wine (Lacey etal.,2009)should be

considered.Amongst the choice factors when selecting wine,taste,wine style (i.e.red or

white)and grape variety (i.e.CabernetSauvignon or Chardonnay)and price tend to

dominate the decision (Bruwer and Johnson,2005;Lacey et al.,2009).Through H5,H6

and H7, we therefore postulate that:

H5. Diners with a high level of wine involvement are more likely to use the wine menu

when ordering wine in a restaurant than those with a low wine involvement level.

H6. Diners with a low level of wine involvement are more likely to use the advice of

service staffwhen ordering wine in a restaurantthan those with a high wine

involvement level.

H7. Diners with a high level of wine involvement are more likely to use the taste of wine,

wine style and grape variety as the main choice factors when ordering wine in a

restaurant than those with a low wine involvement level.

Methodology

The main aim of this study is to identify how diners’ involvement with wine impacts their

wine consumption behaviour when dining in US restaurants and how this relates to the

nature, composition and size of their dining group. During the operalisation process, a scale

was designedfor measuringthe diners’wine involvementlevel.To date,most

wine involvement studies either developed/used scales that measured only the enduring

wine involvementconstruct(Barber etal.,2007;Bruwer and Buller,2013;Bruwer and

Huang,2012;Hirche and Bruwer,2014;Hollebeek and Brodie,2009).In the restaurant

context,which is very situation-specific,it is essentialthatthe (temporal)situational

involvement construct also be incorporated in the measurement of wine involvement. A five-

item involvement scale developed by Dholakia (2001) brought together both components of

involvement and delivered robust results. Therefore, given the fact that no similar scale with

wine as product focus has been developed, we adopted Dholakia’s (2001) scale and adjusted

it to wine as a productand restaurants as its situation-specific context.As far as the

practicalimplications ofthis study are concerned,the main aim is to develop profile

descriptions, informed by the study’s findings, for all US restaurant categories.

Sample

An online survey was executed in the USA by engaging a professionalconsumer panel

company involving people of legal drinking age (21 years and older) who consumed wine

and had dined out at least once during the previous month at any one of the US restaurant

Wine

involvement

interaction

17

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

categories(Canzianiet al., 2016;NationalRestaurantAssociation,2017)wherethey

consumed wine on that occasion. All information obtained from the respondents re

to their last dining occasion in a restaurant.The online survey eliminated the logistical

issues and invasion of diners’privacy that occurs when information is collected in situ at

restaurants whilst providing the advantage of sampling across the USA and its diffe

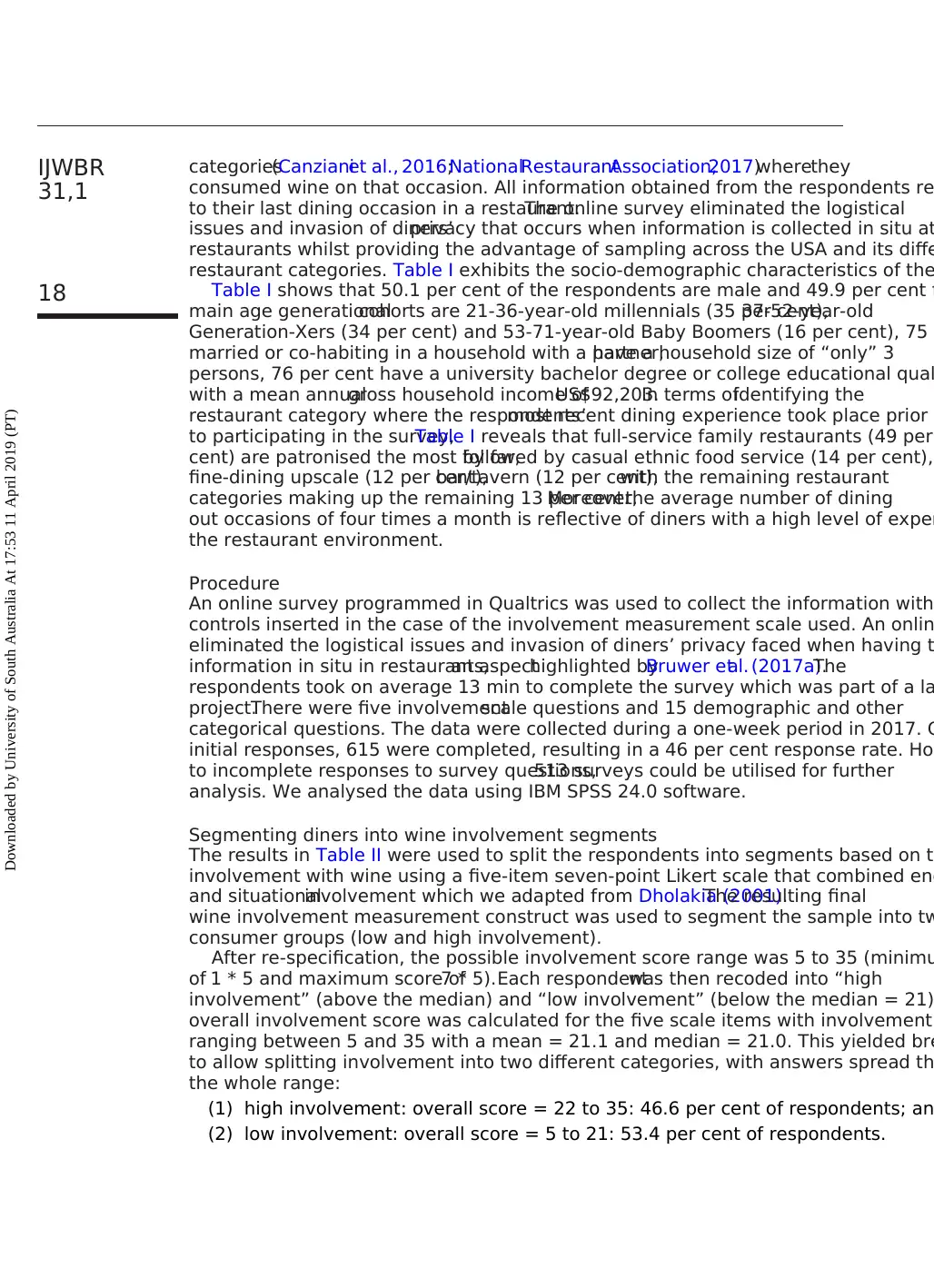

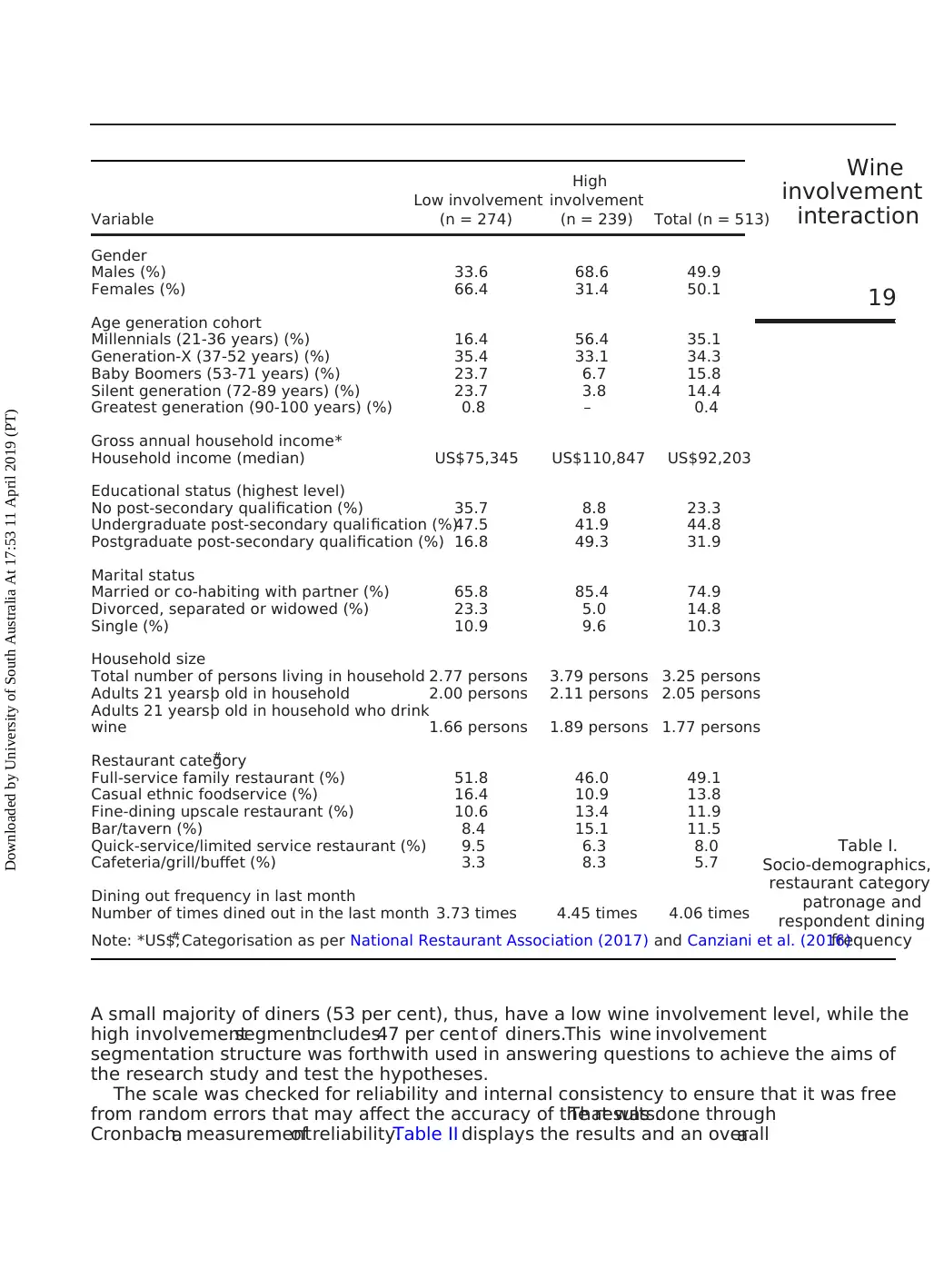

restaurant categories. Table I exhibits the socio-demographic characteristics of the

Table I shows that 50.1 per cent of the respondents are male and 49.9 per cent f

main age generationalcohorts are 21-36-year-old millennials (35 per cent),37-52-year-old

Generation-Xers (34 per cent) and 53-71-year-old Baby Boomers (16 per cent), 75

married or co-habiting in a household with a partner,have a household size of “only” 3

persons, 76 per cent have a university bachelor degree or college educational qual

with a mean annualgross household income ofUS$92,203.In terms ofidentifying the

restaurant category where the respondents’most recent dining experience took place prior

to participating in the survey,Table I reveals that full-service family restaurants (49 per

cent) are patronised the most by far,followed by casual ethnic food service (14 per cent),

fine-dining upscale (12 per cent),bar/tavern (12 per cent),with the remaining restaurant

categories making up the remaining 13 per cent.Moreover,the average number of dining

out occasions of four times a month is reflective of diners with a high level of exper

the restaurant environment.

Procedure

An online survey programmed in Qualtrics was used to collect the information with

controls inserted in the case of the involvement measurement scale used. An onlin

eliminated the logistical issues and invasion of diners’ privacy faced when having t

information in situ in restaurants,an aspecthighlighted byBruwer etal. (2017a).The

respondents took on average 13 min to complete the survey which was part of a la

project.There were five involvementscale questions and 15 demographic and other

categorical questions. The data were collected during a one-week period in 2017. O

initial responses, 615 were completed, resulting in a 46 per cent response rate. How

to incomplete responses to survey questions,513 surveys could be utilised for further

analysis. We analysed the data using IBM SPSS 24.0 software.

Segmenting diners into wine involvement segments

The results in Table II were used to split the respondents into segments based on th

involvement with wine using a five-item seven-point Likert scale that combined end

and situationalinvolvement which we adapted from Dholakia (2001).The resulting final

wine involvement measurement construct was used to segment the sample into tw

consumer groups (low and high involvement).

After re-specification, the possible involvement score range was 5 to 35 (minimu

of 1 * 5 and maximum score of7 * 5).Each respondentwas then recoded into “high

involvement” (above the median) and “low involvement” (below the median = 21)

overall involvement score was calculated for the five scale items with involvement

ranging between 5 and 35 with a mean = 21.1 and median = 21.0. This yielded bre

to allow splitting involvement into two different categories, with answers spread th

the whole range:

(1) high involvement: overall score = 22 to 35: 46.6 per cent of respondents; an

(2) low involvement: overall score = 5 to 21: 53.4 per cent of respondents.

IJWBR

31,1

18

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

consumed wine on that occasion. All information obtained from the respondents re

to their last dining occasion in a restaurant.The online survey eliminated the logistical

issues and invasion of diners’privacy that occurs when information is collected in situ at

restaurants whilst providing the advantage of sampling across the USA and its diffe

restaurant categories. Table I exhibits the socio-demographic characteristics of the

Table I shows that 50.1 per cent of the respondents are male and 49.9 per cent f

main age generationalcohorts are 21-36-year-old millennials (35 per cent),37-52-year-old

Generation-Xers (34 per cent) and 53-71-year-old Baby Boomers (16 per cent), 75

married or co-habiting in a household with a partner,have a household size of “only” 3

persons, 76 per cent have a university bachelor degree or college educational qual

with a mean annualgross household income ofUS$92,203.In terms ofidentifying the

restaurant category where the respondents’most recent dining experience took place prior

to participating in the survey,Table I reveals that full-service family restaurants (49 per

cent) are patronised the most by far,followed by casual ethnic food service (14 per cent),

fine-dining upscale (12 per cent),bar/tavern (12 per cent),with the remaining restaurant

categories making up the remaining 13 per cent.Moreover,the average number of dining

out occasions of four times a month is reflective of diners with a high level of exper

the restaurant environment.

Procedure

An online survey programmed in Qualtrics was used to collect the information with

controls inserted in the case of the involvement measurement scale used. An onlin

eliminated the logistical issues and invasion of diners’ privacy faced when having t

information in situ in restaurants,an aspecthighlighted byBruwer etal. (2017a).The

respondents took on average 13 min to complete the survey which was part of a la

project.There were five involvementscale questions and 15 demographic and other

categorical questions. The data were collected during a one-week period in 2017. O

initial responses, 615 were completed, resulting in a 46 per cent response rate. How

to incomplete responses to survey questions,513 surveys could be utilised for further

analysis. We analysed the data using IBM SPSS 24.0 software.

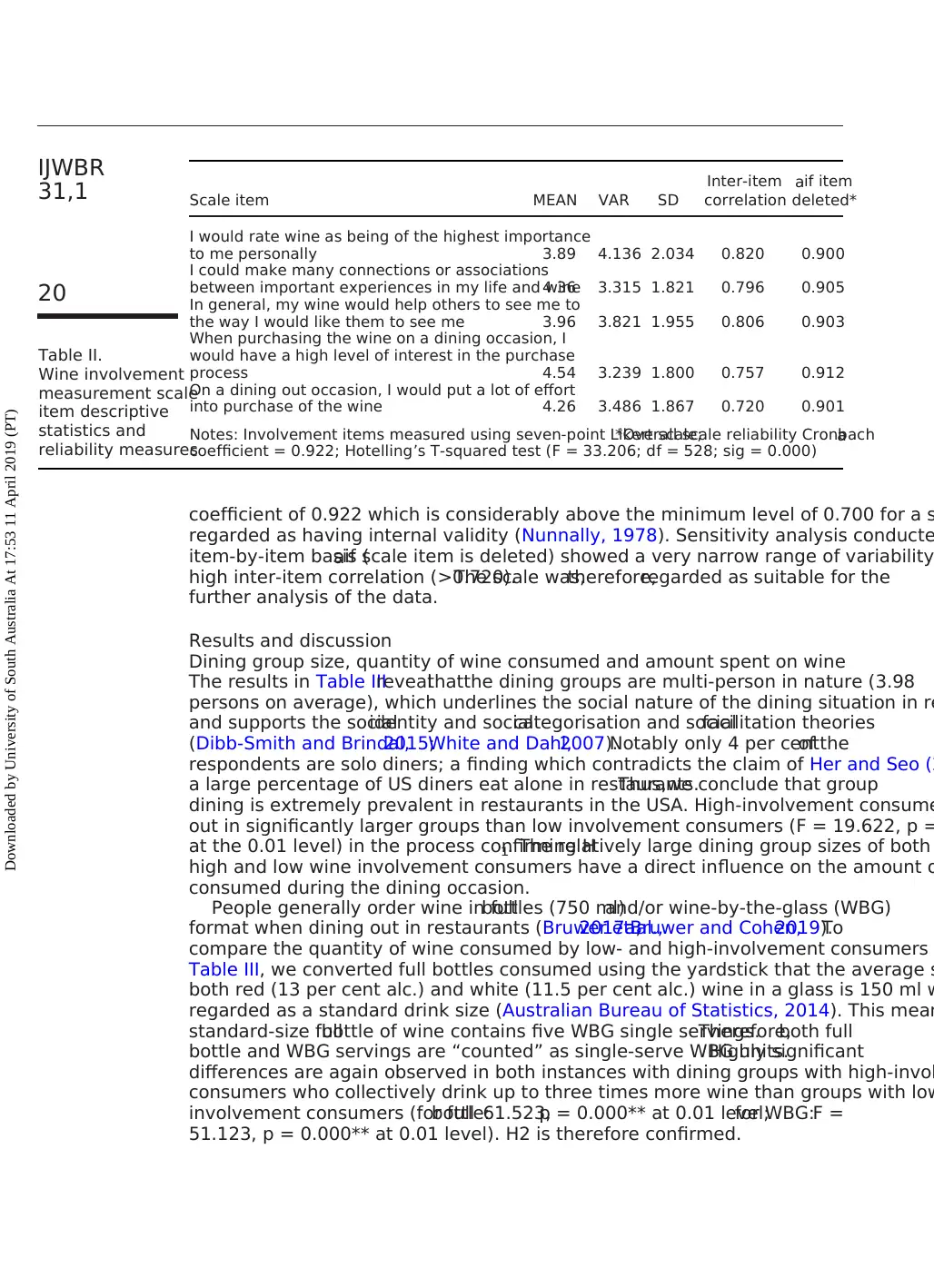

Segmenting diners into wine involvement segments

The results in Table II were used to split the respondents into segments based on th

involvement with wine using a five-item seven-point Likert scale that combined end

and situationalinvolvement which we adapted from Dholakia (2001).The resulting final

wine involvement measurement construct was used to segment the sample into tw

consumer groups (low and high involvement).

After re-specification, the possible involvement score range was 5 to 35 (minimu

of 1 * 5 and maximum score of7 * 5).Each respondentwas then recoded into “high

involvement” (above the median) and “low involvement” (below the median = 21)

overall involvement score was calculated for the five scale items with involvement

ranging between 5 and 35 with a mean = 21.1 and median = 21.0. This yielded bre

to allow splitting involvement into two different categories, with answers spread th

the whole range:

(1) high involvement: overall score = 22 to 35: 46.6 per cent of respondents; an

(2) low involvement: overall score = 5 to 21: 53.4 per cent of respondents.

IJWBR

31,1

18

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

A small majority of diners (53 per cent), thus, have a low wine involvement level, while the

high involvementsegmentincludes47 per centof diners.This wine involvement

segmentation structure was forthwith used in answering questions to achieve the aims of

the research study and test the hypotheses.

The scale was checked for reliability and internal consistency to ensure that it was free

from random errors that may affect the accuracy of the results.That was done through

Cronbacha measurementof reliability.Table II displays the results and an overalla

Table I.

Socio-demographics,

restaurant category

patronage and

respondent dining

frequency

Variable

Low involvement

(n = 274)

High

involvement

(n = 239) Total (n = 513)

Gender

Males (%) 33.6 68.6 49.9

Females (%) 66.4 31.4 50.1

Age generation cohort

Millennials (21-36 years) (%) 16.4 56.4 35.1

Generation-X (37-52 years) (%) 35.4 33.1 34.3

Baby Boomers (53-71 years) (%) 23.7 6.7 15.8

Silent generation (72-89 years) (%) 23.7 3.8 14.4

Greatest generation (90-100 years) (%) 0.8 – 0.4

Gross annual household income*

Household income (median) US$75,345 US$110,847 US$92,203

Educational status (highest level)

No post-secondary qualification (%) 35.7 8.8 23.3

Undergraduate post-secondary qualification (%)47.5 41.9 44.8

Postgraduate post-secondary qualification (%) 16.8 49.3 31.9

Marital status

Married or co-habiting with partner (%) 65.8 85.4 74.9

Divorced, separated or widowed (%) 23.3 5.0 14.8

Single (%) 10.9 9.6 10.3

Household size

Total number of persons living in household 2.77 persons 3.79 persons 3.25 persons

Adults 21 yearsþ old in household 2.00 persons 2.11 persons 2.05 persons

Adults 21 yearsþ old in household who drink

wine 1.66 persons 1.89 persons 1.77 persons

Restaurant category#

Full-service family restaurant (%) 51.8 46.0 49.1

Casual ethnic foodservice (%) 16.4 10.9 13.8

Fine-dining upscale restaurant (%) 10.6 13.4 11.9

Bar/tavern (%) 8.4 15.1 11.5

Quick-service/limited service restaurant (%) 9.5 6.3 8.0

Cafeteria/grill/buffet (%) 3.3 8.3 5.7

Dining out frequency in last month

Number of times dined out in the last month 3.73 times 4.45 times 4.06 times

Note: *US$;# Categorisation as per National Restaurant Association (2017) and Canziani et al. (2016)

Wine

involvement

interaction

19

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

high involvementsegmentincludes47 per centof diners.This wine involvement

segmentation structure was forthwith used in answering questions to achieve the aims of

the research study and test the hypotheses.

The scale was checked for reliability and internal consistency to ensure that it was free

from random errors that may affect the accuracy of the results.That was done through

Cronbacha measurementof reliability.Table II displays the results and an overalla

Table I.

Socio-demographics,

restaurant category

patronage and

respondent dining

frequency

Variable

Low involvement

(n = 274)

High

involvement

(n = 239) Total (n = 513)

Gender

Males (%) 33.6 68.6 49.9

Females (%) 66.4 31.4 50.1

Age generation cohort

Millennials (21-36 years) (%) 16.4 56.4 35.1

Generation-X (37-52 years) (%) 35.4 33.1 34.3

Baby Boomers (53-71 years) (%) 23.7 6.7 15.8

Silent generation (72-89 years) (%) 23.7 3.8 14.4

Greatest generation (90-100 years) (%) 0.8 – 0.4

Gross annual household income*

Household income (median) US$75,345 US$110,847 US$92,203

Educational status (highest level)

No post-secondary qualification (%) 35.7 8.8 23.3

Undergraduate post-secondary qualification (%)47.5 41.9 44.8

Postgraduate post-secondary qualification (%) 16.8 49.3 31.9

Marital status

Married or co-habiting with partner (%) 65.8 85.4 74.9

Divorced, separated or widowed (%) 23.3 5.0 14.8

Single (%) 10.9 9.6 10.3

Household size

Total number of persons living in household 2.77 persons 3.79 persons 3.25 persons

Adults 21 yearsþ old in household 2.00 persons 2.11 persons 2.05 persons

Adults 21 yearsþ old in household who drink

wine 1.66 persons 1.89 persons 1.77 persons

Restaurant category#

Full-service family restaurant (%) 51.8 46.0 49.1

Casual ethnic foodservice (%) 16.4 10.9 13.8

Fine-dining upscale restaurant (%) 10.6 13.4 11.9

Bar/tavern (%) 8.4 15.1 11.5

Quick-service/limited service restaurant (%) 9.5 6.3 8.0

Cafeteria/grill/buffet (%) 3.3 8.3 5.7

Dining out frequency in last month

Number of times dined out in the last month 3.73 times 4.45 times 4.06 times

Note: *US$;# Categorisation as per National Restaurant Association (2017) and Canziani et al. (2016)

Wine

involvement

interaction

19

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

coefficient of 0.922 which is considerably above the minimum level of 0.700 for a s

regarded as having internal validity (Nunnally, 1978). Sensitivity analysis conducte

item-by-item basis (aif scale item is deleted) showed a very narrow range of variability

high inter-item correlation (>0.720).The scale was,therefore,regarded as suitable for the

further analysis of the data.

Results and discussion

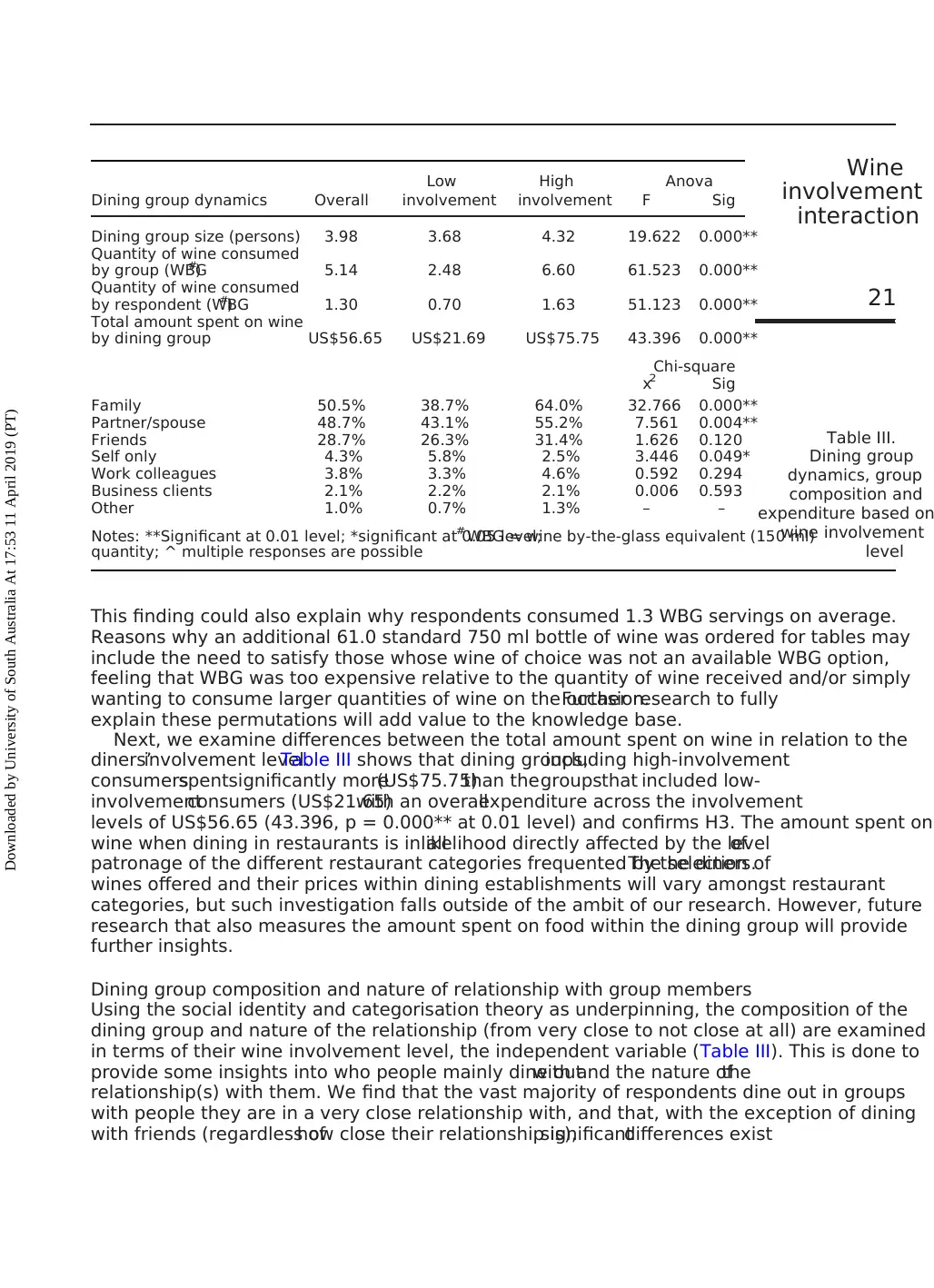

Dining group size, quantity of wine consumed and amount spent on wine

The results in Table IIIrevealthatthe dining groups are multi-person in nature (3.98

persons on average), which underlines the social nature of the dining situation in re

and supports the socialidentity and socialcategorisation and socialfacilitation theories

(Dibb-Smith and Brindal,2015;White and Dahl,2007).Notably only 4 per centof the

respondents are solo diners; a finding which contradicts the claim of Her and Seo (2

a large percentage of US diners eat alone in restaurants.Thus,we conclude that group

dining is extremely prevalent in restaurants in the USA. High-involvement consume

out in significantly larger groups than low involvement consumers (F = 19.622, p =

at the 0.01 level) in the process confirming H1. The relatively large dining group sizes of both

high and low wine involvement consumers have a direct influence on the amount o

consumed during the dining occasion.

People generally order wine in fullbottles (750 ml)and/or wine-by-the-glass (WBG)

format when dining out in restaurants (Bruwer et al.,2017a;Bruwer and Cohen,2019).To

compare the quantity of wine consumed by low- and high-involvement consumers

Table III, we converted full bottles consumed using the yardstick that the average s

both red (13 per cent alc.) and white (11.5 per cent alc.) wine in a glass is 150 ml w

regarded as a standard drink size (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2014). This mean

standard-size fullbottle of wine contains five WBG single servings.Therefore,both full

bottle and WBG servings are “counted” as single-serve WBG units.Highly significant

differences are again observed in both instances with dining groups with high-invol

consumers who collectively drink up to three times more wine than groups with low

involvement consumers (for fullbottle:61.523,p = 0.000** at 0.01 level;for WBG:F =

51.123, p = 0.000** at 0.01 level). H2 is therefore confirmed.

Table II.

Wine involvement

measurement scale

item descriptive

statistics and

reliability measures

Scale item MEAN VAR SD

Inter-item

correlation

aif item

deleted*

I would rate wine as being of the highest importance

to me personally 3.89 4.136 2.034 0.820 0.900

I could make many connections or associations

between important experiences in my life and wine4.36 3.315 1.821 0.796 0.905

In general, my wine would help others to see me to

the way I would like them to see me 3.96 3.821 1.955 0.806 0.903

When purchasing the wine on a dining occasion, I

would have a high level of interest in the purchase

process 4.54 3.239 1.800 0.757 0.912

On a dining out occasion, I would put a lot of effort

into purchase of the wine 4.26 3.486 1.867 0.720 0.901

Notes: Involvement items measured using seven-point Likert scale;*Overall scale reliability Cronbacha

coefficient = 0.922; Hotelling’s T-squared test (F = 33.206; df = 528; sig = 0.000)

IJWBR

31,1

20

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

regarded as having internal validity (Nunnally, 1978). Sensitivity analysis conducte

item-by-item basis (aif scale item is deleted) showed a very narrow range of variability

high inter-item correlation (>0.720).The scale was,therefore,regarded as suitable for the

further analysis of the data.

Results and discussion

Dining group size, quantity of wine consumed and amount spent on wine

The results in Table IIIrevealthatthe dining groups are multi-person in nature (3.98

persons on average), which underlines the social nature of the dining situation in re

and supports the socialidentity and socialcategorisation and socialfacilitation theories

(Dibb-Smith and Brindal,2015;White and Dahl,2007).Notably only 4 per centof the

respondents are solo diners; a finding which contradicts the claim of Her and Seo (2

a large percentage of US diners eat alone in restaurants.Thus,we conclude that group

dining is extremely prevalent in restaurants in the USA. High-involvement consume

out in significantly larger groups than low involvement consumers (F = 19.622, p =

at the 0.01 level) in the process confirming H1. The relatively large dining group sizes of both

high and low wine involvement consumers have a direct influence on the amount o

consumed during the dining occasion.

People generally order wine in fullbottles (750 ml)and/or wine-by-the-glass (WBG)

format when dining out in restaurants (Bruwer et al.,2017a;Bruwer and Cohen,2019).To

compare the quantity of wine consumed by low- and high-involvement consumers

Table III, we converted full bottles consumed using the yardstick that the average s

both red (13 per cent alc.) and white (11.5 per cent alc.) wine in a glass is 150 ml w

regarded as a standard drink size (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2014). This mean

standard-size fullbottle of wine contains five WBG single servings.Therefore,both full

bottle and WBG servings are “counted” as single-serve WBG units.Highly significant

differences are again observed in both instances with dining groups with high-invol

consumers who collectively drink up to three times more wine than groups with low

involvement consumers (for fullbottle:61.523,p = 0.000** at 0.01 level;for WBG:F =

51.123, p = 0.000** at 0.01 level). H2 is therefore confirmed.

Table II.

Wine involvement

measurement scale

item descriptive

statistics and

reliability measures

Scale item MEAN VAR SD

Inter-item

correlation

aif item

deleted*

I would rate wine as being of the highest importance

to me personally 3.89 4.136 2.034 0.820 0.900

I could make many connections or associations

between important experiences in my life and wine4.36 3.315 1.821 0.796 0.905

In general, my wine would help others to see me to

the way I would like them to see me 3.96 3.821 1.955 0.806 0.903

When purchasing the wine on a dining occasion, I

would have a high level of interest in the purchase

process 4.54 3.239 1.800 0.757 0.912

On a dining out occasion, I would put a lot of effort

into purchase of the wine 4.26 3.486 1.867 0.720 0.901

Notes: Involvement items measured using seven-point Likert scale;*Overall scale reliability Cronbacha

coefficient = 0.922; Hotelling’s T-squared test (F = 33.206; df = 528; sig = 0.000)

IJWBR

31,1

20

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

This finding could also explain why respondents consumed 1.3 WBG servings on average.

Reasons why an additional 61.0 standard 750 ml bottle of wine was ordered for tables may

include the need to satisfy those whose wine of choice was not an available WBG option,

feeling that WBG was too expensive relative to the quantity of wine received and/or simply

wanting to consume larger quantities of wine on the occasion.Further research to fully

explain these permutations will add value to the knowledge base.

Next, we examine differences between the total amount spent on wine in relation to the

diners’involvement level.Table III shows that dining groups,including high-involvement

consumersspentsignificantly more(US$75.75)than thegroupsthat included low-

involvementconsumers (US$21.65)with an overallexpenditure across the involvement

levels of US$56.65 (43.396, p = 0.000** at 0.01 level) and confirms H3. The amount spent on

wine when dining in restaurants is in alllikelihood directly affected by the levelof

patronage of the different restaurant categories frequented by the diners.The selection of

wines offered and their prices within dining establishments will vary amongst restaurant

categories, but such investigation falls outside of the ambit of our research. However, future

research that also measures the amount spent on food within the dining group will provide

further insights.

Dining group composition and nature of relationship with group members

Using the social identity and categorisation theory as underpinning, the composition of the

dining group and nature of the relationship (from very close to not close at all) are examined

in terms of their wine involvement level, the independent variable (Table III). This is done to

provide some insights into who people mainly dine outwith and the nature ofthe

relationship(s) with them. We find that the vast majority of respondents dine out in groups

with people they are in a very close relationship with, and that, with the exception of dining

with friends (regardless ofhow close their relationship is),significantdifferences exist

Table III.

Dining group

dynamics, group

composition and

expenditure based on

wine involvement

level

Low High Anova

Dining group dynamics Overall involvement involvement F Sig

Dining group size (persons) 3.98 3.68 4.32 19.622 0.000**

Quantity of wine consumed

by group (WBG#) 5.14 2.48 6.60 61.523 0.000**

Quantity of wine consumed

by respondent (WBG#) 1.30 0.70 1.63 51.123 0.000**

Total amount spent on wine

by dining group US$56.65 US$21.69 US$75.75 43.396 0.000**

Chi-square

x2 Sig

Family 50.5% 38.7% 64.0% 32.766 0.000**

Partner/spouse 48.7% 43.1% 55.2% 7.561 0.004**

Friends 28.7% 26.3% 31.4% 1.626 0.120

Self only 4.3% 5.8% 2.5% 3.446 0.049*

Work colleagues 3.8% 3.3% 4.6% 0.592 0.294

Business clients 2.1% 2.2% 2.1% 0.006 0.593

Other 1.0% 0.7% 1.3% – –

Notes: **Significant at 0.01 level; *significant at 0.05 level;# WBG = wine by-the-glass equivalent (150 ml)

quantity; ^ multiple responses are possible

Wine

involvement

interaction

21

Downloaded by University of South Australia At 17:53 11 April 2019 (PT)

Reasons why an additional 61.0 standard 750 ml bottle of wine was ordered for tables may

include the need to satisfy those whose wine of choice was not an available WBG option,