FESTEVER Campaign: A Marketing Report for Sydney CBD Revitalisation

VerifiedAdded on 2022/06/01

|11

|3319

|14

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a landscape overview and background analysis for the revitalisation of Sydney's CBD, focusing on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on footfall and patronage. It identifies young people as the target audience and outlines core objectives to bring them back to the city. The report delves into buyer behavior analysis, examining the characteristics and preferences of Millennials and Pivotals, and the influence of geo-demographic groups. It proposes a marketing strategy centered around a series of weekly festivals called 'FESTEVER,' leveraging social media, particularly Instagram, with visually appealing content and symbolic imagery to build consumer confidence and encourage engagement. The report recommends using the Elaboration Likelihood Model's peripheral route to persuasion and incorporates the functional theory of attitudes to understand and influence young people's behavior. The campaign aims to promote the CBD as a destination for discovery and social experiences by showcasing cultural programming and supporting local businesses.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

CBD Revitalisation Brief

Landscape Overview and Background

Footfall and patronage in Sydney’s CBD is down. The COVID-19 pandemic continues to have

a devastating impact on our communities and economy.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic output in the City of Sydney’s local area was

$140 billion per year with an estimated 1.3 million people in the city centre every day. The

economic output of the City of Sydney local area is forecast to fall up to 15.8%.

Workers and visitors make up over 80% of the number of people who are in the city every

day and account for over 80% of expenditure in the local government area. Currently it is

estimated 59% of workers have returned to the CBD. Visitors to CBD are down 40%.

Target Audience

Young people

(looking for a night out, something to do on weekends)

Core Objectives

Primary

Get residents, workers and intra-state visitors (when practicable) back into the city and

reframe it as a place of discovery; eat, drink, dwell, see (both day and night).

Secondary

Support uptake and use of free footway dining, showcase array of cultural programming

(live music, art) along with the other ‘fine-grain’ opportunities.

Lastly

Build consumer confidence – the city is safe and open.

Landscape Overview and Background

Footfall and patronage in Sydney’s CBD is down. The COVID-19 pandemic continues to have

a devastating impact on our communities and economy.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic output in the City of Sydney’s local area was

$140 billion per year with an estimated 1.3 million people in the city centre every day. The

economic output of the City of Sydney local area is forecast to fall up to 15.8%.

Workers and visitors make up over 80% of the number of people who are in the city every

day and account for over 80% of expenditure in the local government area. Currently it is

estimated 59% of workers have returned to the CBD. Visitors to CBD are down 40%.

Target Audience

Young people

(looking for a night out, something to do on weekends)

Core Objectives

Primary

Get residents, workers and intra-state visitors (when practicable) back into the city and

reframe it as a place of discovery; eat, drink, dwell, see (both day and night).

Secondary

Support uptake and use of free footway dining, showcase array of cultural programming

(live music, art) along with the other ‘fine-grain’ opportunities.

Lastly

Build consumer confidence – the city is safe and open.

Buyer Behaviour Analysis

Young people can be identified collectively as members of Generations Y and Z, otherwise known as

Millennials and Pivotals, the two generational age cohorts of adults in their late teens to early thirties

who “share similar early life experiences that shape their values, preferences, and behaviours

throughout their lives” (Hoyer, MacInnis & Pieters, 2018, p. 323). These cohorts are “young, well

informed, and they have money to spend” (Lobo, 2014). “They share a love of social media, extensive

friend networks, and visibility into the lives of others. They both desire active participation and

cocreation with brands, and pledge to make a difference in the world.” (Fromm & Read, 2018, p. 7).

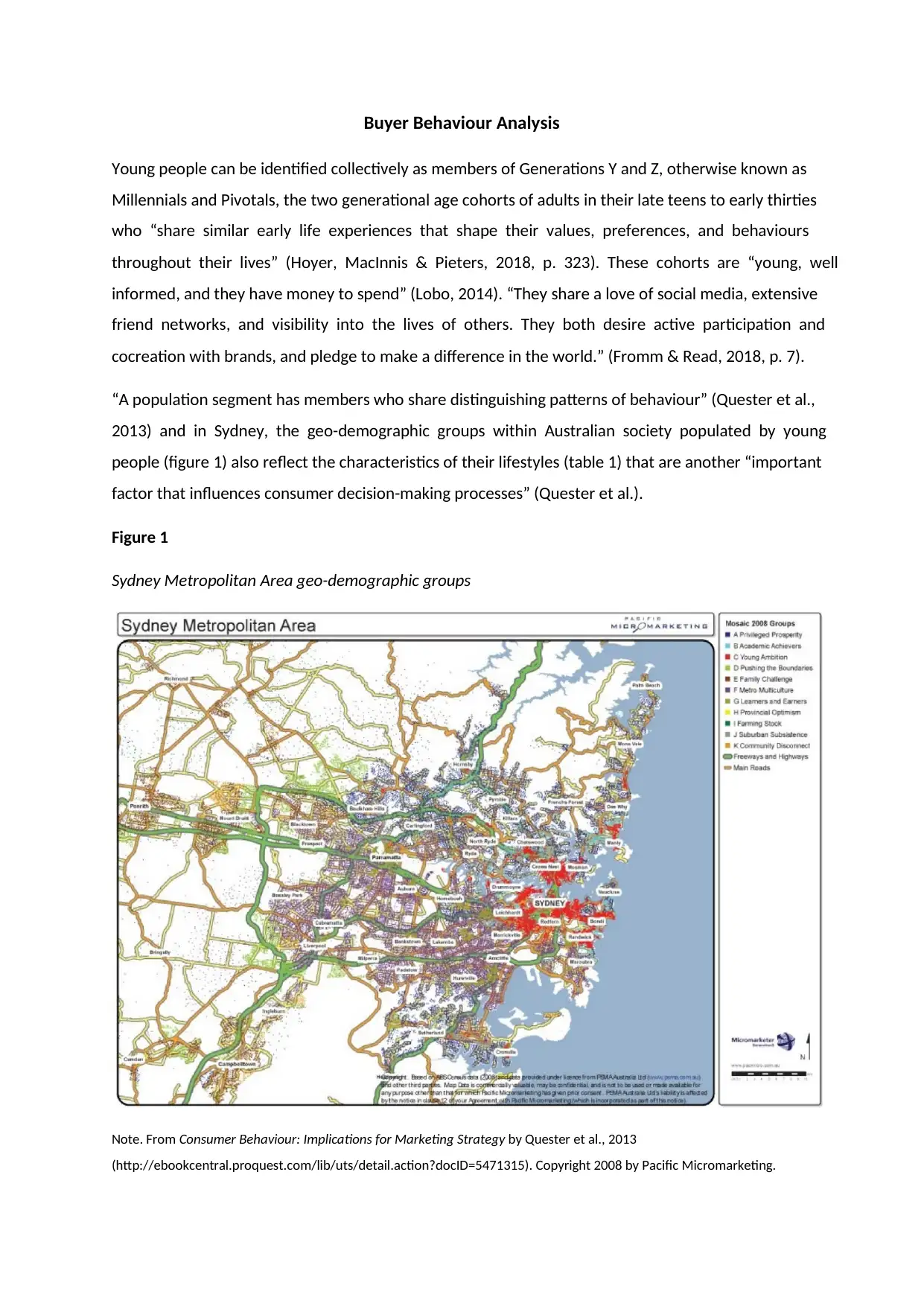

“A population segment has members who share distinguishing patterns of behaviour” (Quester et al.,

2013) and in Sydney, the geo-demographic groups within Australian society populated by young

people (figure 1) also reflect the characteristics of their lifestyles (table 1) that are another “important

factor that influences consumer decision-making processes” (Quester et al.).

Figure 1

Sydney Metropolitan Area geo-demographic groups

Note. From Consumer Behaviour: Implications for Marketing Strategy by Quester et al., 2013

(http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uts/detail.action?docID=5471315). Copyright 2008 by Pacific Micromarketing.

Young people can be identified collectively as members of Generations Y and Z, otherwise known as

Millennials and Pivotals, the two generational age cohorts of adults in their late teens to early thirties

who “share similar early life experiences that shape their values, preferences, and behaviours

throughout their lives” (Hoyer, MacInnis & Pieters, 2018, p. 323). These cohorts are “young, well

informed, and they have money to spend” (Lobo, 2014). “They share a love of social media, extensive

friend networks, and visibility into the lives of others. They both desire active participation and

cocreation with brands, and pledge to make a difference in the world.” (Fromm & Read, 2018, p. 7).

“A population segment has members who share distinguishing patterns of behaviour” (Quester et al.,

2013) and in Sydney, the geo-demographic groups within Australian society populated by young

people (figure 1) also reflect the characteristics of their lifestyles (table 1) that are another “important

factor that influences consumer decision-making processes” (Quester et al.).

Figure 1

Sydney Metropolitan Area geo-demographic groups

Note. From Consumer Behaviour: Implications for Marketing Strategy by Quester et al., 2013

(http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uts/detail.action?docID=5471315). Copyright 2008 by Pacific Micromarketing.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

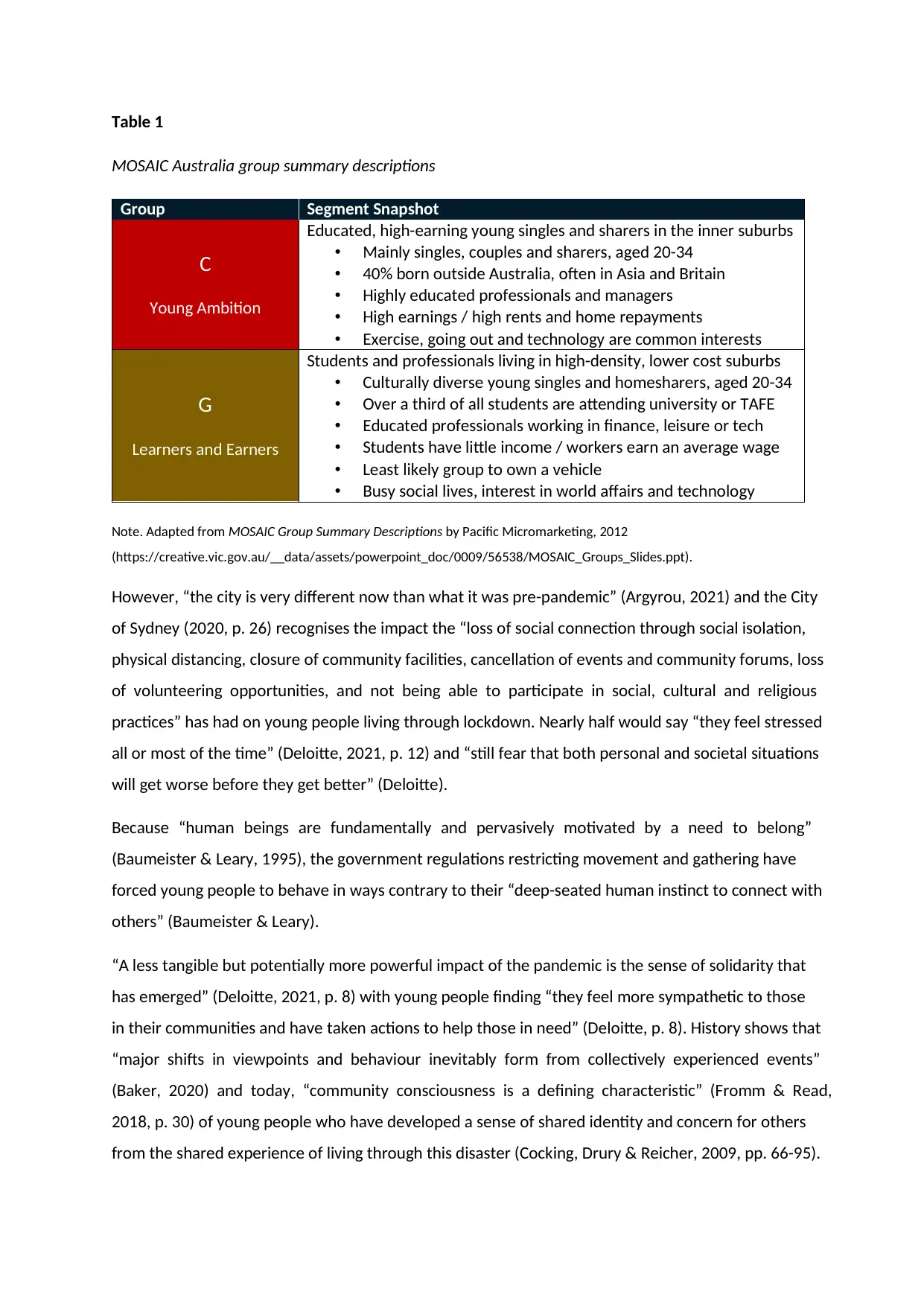

Table 1

MOSAIC Australia group summary descriptions

Group Segment Snapshot

C

Young Ambition

Educated, high-earning young singles and sharers in the inner suburbs

• Mainly singles, couples and sharers, aged 20-34

• 40% born outside Australia, often in Asia and Britain

• Highly educated professionals and managers

• High earnings / high rents and home repayments

• Exercise, going out and technology are common interests

G

Learners and Earners

Students and professionals living in high-density, lower cost suburbs

• Culturally diverse young singles and homesharers, aged 20-34

• Over a third of all students are attending university or TAFE

• Educated professionals working in finance, leisure or tech

• Students have little income / workers earn an average wage

• Least likely group to own a vehicle

• Busy social lives, interest in world affairs and technology

Note. Adapted from MOSAIC Group Summary Descriptions by Pacific Micromarketing, 2012

(https://creative.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/powerpoint_doc/0009/56538/MOSAIC_Groups_Slides.ppt).

However, “the city is very different now than what it was pre-pandemic” (Argyrou, 2021) and the City

of Sydney (2020, p. 26) recognises the impact the “loss of social connection through social isolation,

physical distancing, closure of community facilities, cancellation of events and community forums, loss

of volunteering opportunities, and not being able to participate in social, cultural and religious

practices” has had on young people living through lockdown. Nearly half would say “they feel stressed

all or most of the time” (Deloitte, 2021, p. 12) and “still fear that both personal and societal situations

will get worse before they get better” (Deloitte).

Because “human beings are fundamentally and pervasively motivated by a need to belong”

(Baumeister & Leary, 1995), the government regulations restricting movement and gathering have

forced young people to behave in ways contrary to their “deep-seated human instinct to connect with

others” (Baumeister & Leary).

“A less tangible but potentially more powerful impact of the pandemic is the sense of solidarity that

has emerged” (Deloitte, 2021, p. 8) with young people finding “they feel more sympathetic to those

in their communities and have taken actions to help those in need” (Deloitte, p. 8). History shows that

“major shifts in viewpoints and behaviour inevitably form from collectively experienced events”

(Baker, 2020) and today, “community consciousness is a defining characteristic” (Fromm & Read,

2018, p. 30) of young people who have developed a sense of shared identity and concern for others

from the shared experience of living through this disaster (Cocking, Drury & Reicher, 2009, pp. 66-95).

MOSAIC Australia group summary descriptions

Group Segment Snapshot

C

Young Ambition

Educated, high-earning young singles and sharers in the inner suburbs

• Mainly singles, couples and sharers, aged 20-34

• 40% born outside Australia, often in Asia and Britain

• Highly educated professionals and managers

• High earnings / high rents and home repayments

• Exercise, going out and technology are common interests

G

Learners and Earners

Students and professionals living in high-density, lower cost suburbs

• Culturally diverse young singles and homesharers, aged 20-34

• Over a third of all students are attending university or TAFE

• Educated professionals working in finance, leisure or tech

• Students have little income / workers earn an average wage

• Least likely group to own a vehicle

• Busy social lives, interest in world affairs and technology

Note. Adapted from MOSAIC Group Summary Descriptions by Pacific Micromarketing, 2012

(https://creative.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/powerpoint_doc/0009/56538/MOSAIC_Groups_Slides.ppt).

However, “the city is very different now than what it was pre-pandemic” (Argyrou, 2021) and the City

of Sydney (2020, p. 26) recognises the impact the “loss of social connection through social isolation,

physical distancing, closure of community facilities, cancellation of events and community forums, loss

of volunteering opportunities, and not being able to participate in social, cultural and religious

practices” has had on young people living through lockdown. Nearly half would say “they feel stressed

all or most of the time” (Deloitte, 2021, p. 12) and “still fear that both personal and societal situations

will get worse before they get better” (Deloitte).

Because “human beings are fundamentally and pervasively motivated by a need to belong”

(Baumeister & Leary, 1995), the government regulations restricting movement and gathering have

forced young people to behave in ways contrary to their “deep-seated human instinct to connect with

others” (Baumeister & Leary).

“A less tangible but potentially more powerful impact of the pandemic is the sense of solidarity that

has emerged” (Deloitte, 2021, p. 8) with young people finding “they feel more sympathetic to those

in their communities and have taken actions to help those in need” (Deloitte, p. 8). History shows that

“major shifts in viewpoints and behaviour inevitably form from collectively experienced events”

(Baker, 2020) and today, “community consciousness is a defining characteristic” (Fromm & Read,

2018, p. 30) of young people who have developed a sense of shared identity and concern for others

from the shared experience of living through this disaster (Cocking, Drury & Reicher, 2009, pp. 66-95).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Having “regularly avoided shops, public transport, and other crowded places … these generations are

eager to regain the freedoms lost during the pandemic” (Deloitte, 2021, p. 9) with “a strong appetite

for ‘going out’ and pursuing the experiences these groups value” (Deloitte, p. 9) now that the stay-at-

home health orders have come to an end.

Being “driven by a need for social recognition” (Fromm & Read, 2018, p. 27), young people are

“collectors of experiences and use it to further their social currency with friends and people in social

circles” (Cox, as cited in Fromm & Read, 2018, pp. 28-29). “Young people have the tendency to

participate in activities with their peers” (Cormack, 1992, p. 7) and as they emerge from lockdown,

they will “seek out opportunities to be seen doing fun and exciting activities, like attending concerts

and sporting events, going out to eat, traveling, or just hanging out in trendy places with their friends”

(Fromm & Read, pp. 27-28) however “most people indicated that it would take longer for them to feel

confident going to indoor cultural and community events” (City of Sydney, 2020, p. 14).

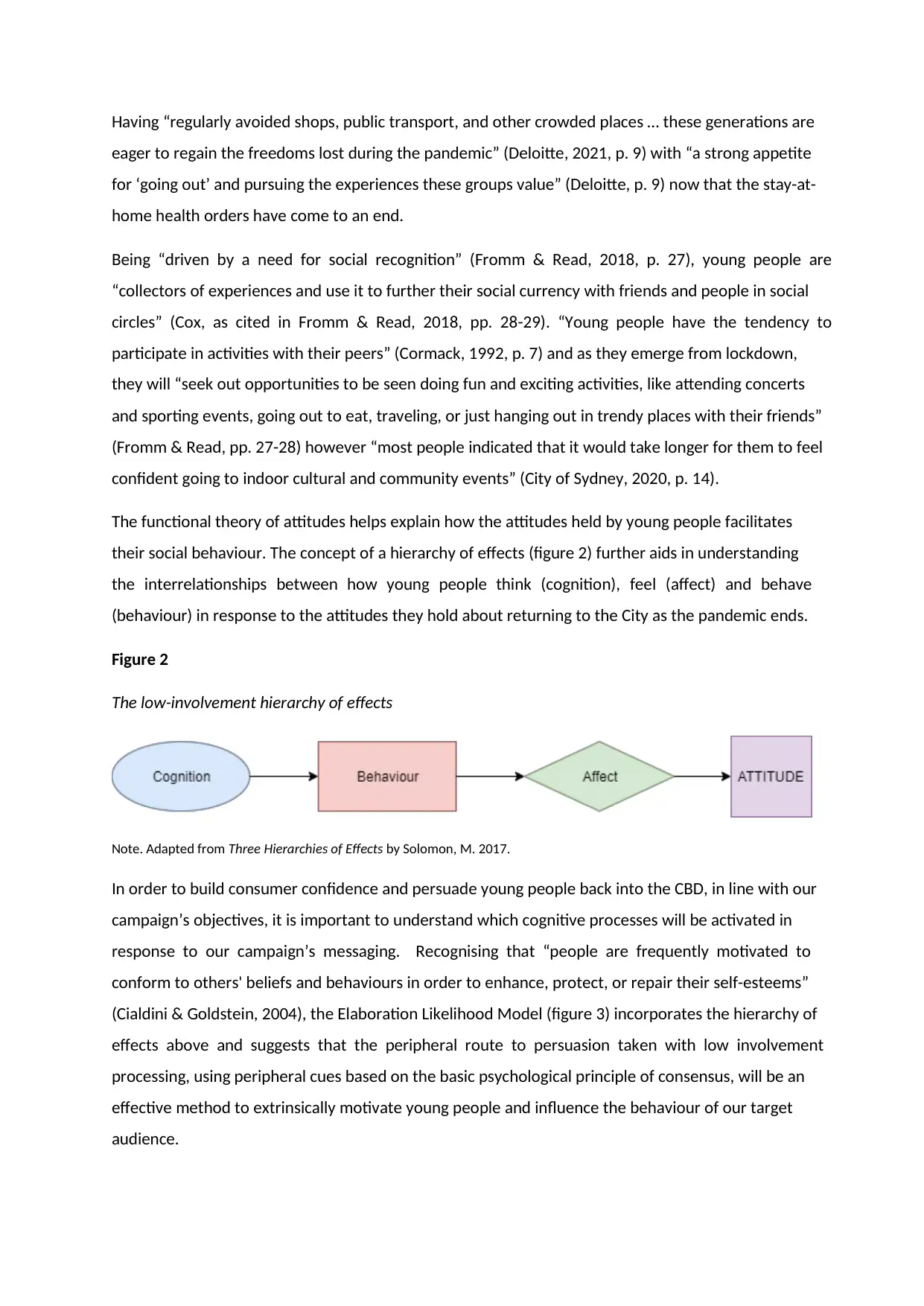

The functional theory of attitudes helps explain how the attitudes held by young people facilitates

their social behaviour. The concept of a hierarchy of effects (figure 2) further aids in understanding

the interrelationships between how young people think (cognition), feel (affect) and behave

(behaviour) in response to the attitudes they hold about returning to the City as the pandemic ends.

Figure 2

The low-involvement hierarchy of effects

Note. Adapted from Three Hierarchies of Effects by Solomon, M. 2017.

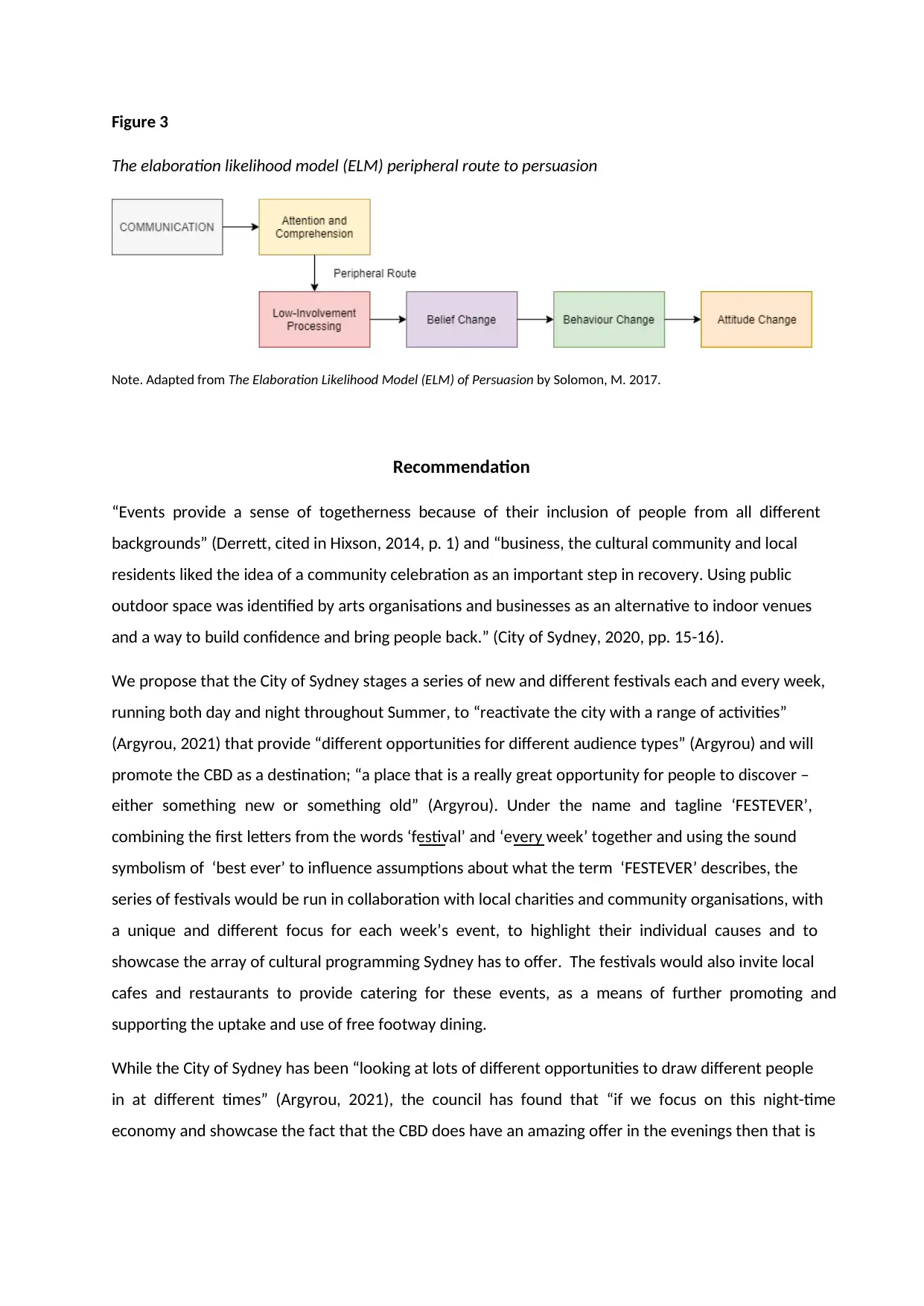

In order to build consumer confidence and persuade young people back into the CBD, in line with our

campaign’s objectives, it is important to understand which cognitive processes will be activated in

response to our campaign’s messaging. Recognising that “people are frequently motivated to

conform to others' beliefs and behaviours in order to enhance, protect, or repair their self-esteems”

(Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004), the Elaboration Likelihood Model (figure 3) incorporates the hierarchy of

effects above and suggests that the peripheral route to persuasion taken with low involvement

processing, using peripheral cues based on the basic psychological principle of consensus, will be an

effective method to extrinsically motivate young people and influence the behaviour of our target

audience.

eager to regain the freedoms lost during the pandemic” (Deloitte, 2021, p. 9) with “a strong appetite

for ‘going out’ and pursuing the experiences these groups value” (Deloitte, p. 9) now that the stay-at-

home health orders have come to an end.

Being “driven by a need for social recognition” (Fromm & Read, 2018, p. 27), young people are

“collectors of experiences and use it to further their social currency with friends and people in social

circles” (Cox, as cited in Fromm & Read, 2018, pp. 28-29). “Young people have the tendency to

participate in activities with their peers” (Cormack, 1992, p. 7) and as they emerge from lockdown,

they will “seek out opportunities to be seen doing fun and exciting activities, like attending concerts

and sporting events, going out to eat, traveling, or just hanging out in trendy places with their friends”

(Fromm & Read, pp. 27-28) however “most people indicated that it would take longer for them to feel

confident going to indoor cultural and community events” (City of Sydney, 2020, p. 14).

The functional theory of attitudes helps explain how the attitudes held by young people facilitates

their social behaviour. The concept of a hierarchy of effects (figure 2) further aids in understanding

the interrelationships between how young people think (cognition), feel (affect) and behave

(behaviour) in response to the attitudes they hold about returning to the City as the pandemic ends.

Figure 2

The low-involvement hierarchy of effects

Note. Adapted from Three Hierarchies of Effects by Solomon, M. 2017.

In order to build consumer confidence and persuade young people back into the CBD, in line with our

campaign’s objectives, it is important to understand which cognitive processes will be activated in

response to our campaign’s messaging. Recognising that “people are frequently motivated to

conform to others' beliefs and behaviours in order to enhance, protect, or repair their self-esteems”

(Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004), the Elaboration Likelihood Model (figure 3) incorporates the hierarchy of

effects above and suggests that the peripheral route to persuasion taken with low involvement

processing, using peripheral cues based on the basic psychological principle of consensus, will be an

effective method to extrinsically motivate young people and influence the behaviour of our target

audience.

Figure 3

The elaboration likelihood model (ELM) peripheral route to persuasion

Note. Adapted from The Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) of Persuasion by Solomon, M. 2017.

Recommendation

“Events provide a sense of togetherness because of their inclusion of people from all different

backgrounds” (Derrett, cited in Hixson, 2014, p. 1) and “business, the cultural community and local

residents liked the idea of a community celebration as an important step in recovery. Using public

outdoor space was identified by arts organisations and businesses as an alternative to indoor venues

and a way to build confidence and bring people back.” (City of Sydney, 2020, pp. 15-16).

We propose that the City of Sydney stages a series of new and different festivals each and every week,

running both day and night throughout Summer, to “reactivate the city with a range of activities”

(Argyrou, 2021) that provide “different opportunities for different audience types” (Argyrou) and will

promote the CBD as a destination; “a place that is a really great opportunity for people to discover –

either something new or something old” (Argyrou). Under the name and tagline ‘FESTEVER’,

combining the first letters from the words ‘festival’ and ‘every week’ together and using the sound

symbolism of ‘best ever’ to influence assumptions about what the term ‘FESTEVER’ describes, the

series of festivals would be run in collaboration with local charities and community organisations, with

a unique and different focus for each week’s event, to highlight their individual causes and to

showcase the array of cultural programming Sydney has to offer. The festivals would also invite local

cafes and restaurants to provide catering for these events, as a means of further promoting and

supporting the uptake and use of free footway dining.

While the City of Sydney has been “looking at lots of different opportunities to draw different people

in at different times” (Argyrou, 2021), the council has found that “if we focus on this night-time

economy and showcase the fact that the CBD does have an amazing offer in the evenings then that is

The elaboration likelihood model (ELM) peripheral route to persuasion

Note. Adapted from The Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) of Persuasion by Solomon, M. 2017.

Recommendation

“Events provide a sense of togetherness because of their inclusion of people from all different

backgrounds” (Derrett, cited in Hixson, 2014, p. 1) and “business, the cultural community and local

residents liked the idea of a community celebration as an important step in recovery. Using public

outdoor space was identified by arts organisations and businesses as an alternative to indoor venues

and a way to build confidence and bring people back.” (City of Sydney, 2020, pp. 15-16).

We propose that the City of Sydney stages a series of new and different festivals each and every week,

running both day and night throughout Summer, to “reactivate the city with a range of activities”

(Argyrou, 2021) that provide “different opportunities for different audience types” (Argyrou) and will

promote the CBD as a destination; “a place that is a really great opportunity for people to discover –

either something new or something old” (Argyrou). Under the name and tagline ‘FESTEVER’,

combining the first letters from the words ‘festival’ and ‘every week’ together and using the sound

symbolism of ‘best ever’ to influence assumptions about what the term ‘FESTEVER’ describes, the

series of festivals would be run in collaboration with local charities and community organisations, with

a unique and different focus for each week’s event, to highlight their individual causes and to

showcase the array of cultural programming Sydney has to offer. The festivals would also invite local

cafes and restaurants to provide catering for these events, as a means of further promoting and

supporting the uptake and use of free footway dining.

While the City of Sydney has been “looking at lots of different opportunities to draw different people

in at different times” (Argyrou, 2021), the council has found that “if we focus on this night-time

economy and showcase the fact that the CBD does have an amazing offer in the evenings then that is

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

actually then shared across the week and weekends” (Argyrou). With this in mind, our campaign will

primarily use evening and night-time imagery within the marketing of the campaign.

Unlike older generations, young people “do not as frequently use traditional channels of

communication such as television, radio, and the press” (Nikodemska-Wołowik, Bednarz & Foreman,

2019, p. 14). Having “grown up with unparalleled access to social media, smartphones and digital

universes” (Nikodemska-Wołowik, Bednarz & Foreman), young people have become “addicted to the

peer connection and affirmation they’re able to get via social media” (Underwood, cited in Fromm &

Read, 2018, p. 41) so much so that it has become the most effective way to communicate with this

target audience (Debevec, Schewe, Madden & Diamond, 2013).

Instagram is where young people “go to be inspired” (Fromm & Read, 2018, p. 45) and is the preferred

platform used for “creating the most aspirational versions of themselves” (Fromm & Read, p. 45).

Consistent with the images and messages they post online, young people “demand advertising serve

as a reflection of their lifestyle” (Fromm & Read, p. 41) and the “information needs to be direct, quick,

and simple” (Fromm & Garton, 2013, p. 54) as they “definitely prefer shorter forms of communication

that are full of graphic elements” (Nikodemska-Wołowik, Bednarz & Foreman, 2019, p. 14). “What

works best is, unsurprisingly, speed. Hence the importance of visual assets. Images. Short, punchy

text.” (Fromm & Read, p. 51) delivered through authentic “content more in line with their day-to-day

life” (Fromm & Read, p. 14).

Figure 4

Ferris wheel symbology

Symbolic associations can communicate semantic meanings, drawing on

episodic memories to create personal relevance.

“The ferris wheel is usually the most visible element of a fair that can be seen

from a distance” (Lennox) and “is associated with fun and excitement” (Amar).

Understanding the emotional and psychological associations we have with colours and the

corresponding meanings they communicate (Vos, 2020), the banner background is coloured dark blue

because “when you want to be viewed as trustworthy and cool, blue is the colour for you” (Morris,

2013) with the font green as it is “warm and inviting, lending customers a pleasing feeling. Second, it

denotes health, environment and goodwill.” (Morris).

primarily use evening and night-time imagery within the marketing of the campaign.

Unlike older generations, young people “do not as frequently use traditional channels of

communication such as television, radio, and the press” (Nikodemska-Wołowik, Bednarz & Foreman,

2019, p. 14). Having “grown up with unparalleled access to social media, smartphones and digital

universes” (Nikodemska-Wołowik, Bednarz & Foreman), young people have become “addicted to the

peer connection and affirmation they’re able to get via social media” (Underwood, cited in Fromm &

Read, 2018, p. 41) so much so that it has become the most effective way to communicate with this

target audience (Debevec, Schewe, Madden & Diamond, 2013).

Instagram is where young people “go to be inspired” (Fromm & Read, 2018, p. 45) and is the preferred

platform used for “creating the most aspirational versions of themselves” (Fromm & Read, p. 45).

Consistent with the images and messages they post online, young people “demand advertising serve

as a reflection of their lifestyle” (Fromm & Read, p. 41) and the “information needs to be direct, quick,

and simple” (Fromm & Garton, 2013, p. 54) as they “definitely prefer shorter forms of communication

that are full of graphic elements” (Nikodemska-Wołowik, Bednarz & Foreman, 2019, p. 14). “What

works best is, unsurprisingly, speed. Hence the importance of visual assets. Images. Short, punchy

text.” (Fromm & Read, p. 51) delivered through authentic “content more in line with their day-to-day

life” (Fromm & Read, p. 14).

Figure 4

Ferris wheel symbology

Symbolic associations can communicate semantic meanings, drawing on

episodic memories to create personal relevance.

“The ferris wheel is usually the most visible element of a fair that can be seen

from a distance” (Lennox) and “is associated with fun and excitement” (Amar).

Understanding the emotional and psychological associations we have with colours and the

corresponding meanings they communicate (Vos, 2020), the banner background is coloured dark blue

because “when you want to be viewed as trustworthy and cool, blue is the colour for you” (Morris,

2013) with the font green as it is “warm and inviting, lending customers a pleasing feeling. Second, it

denotes health, environment and goodwill.” (Morris).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

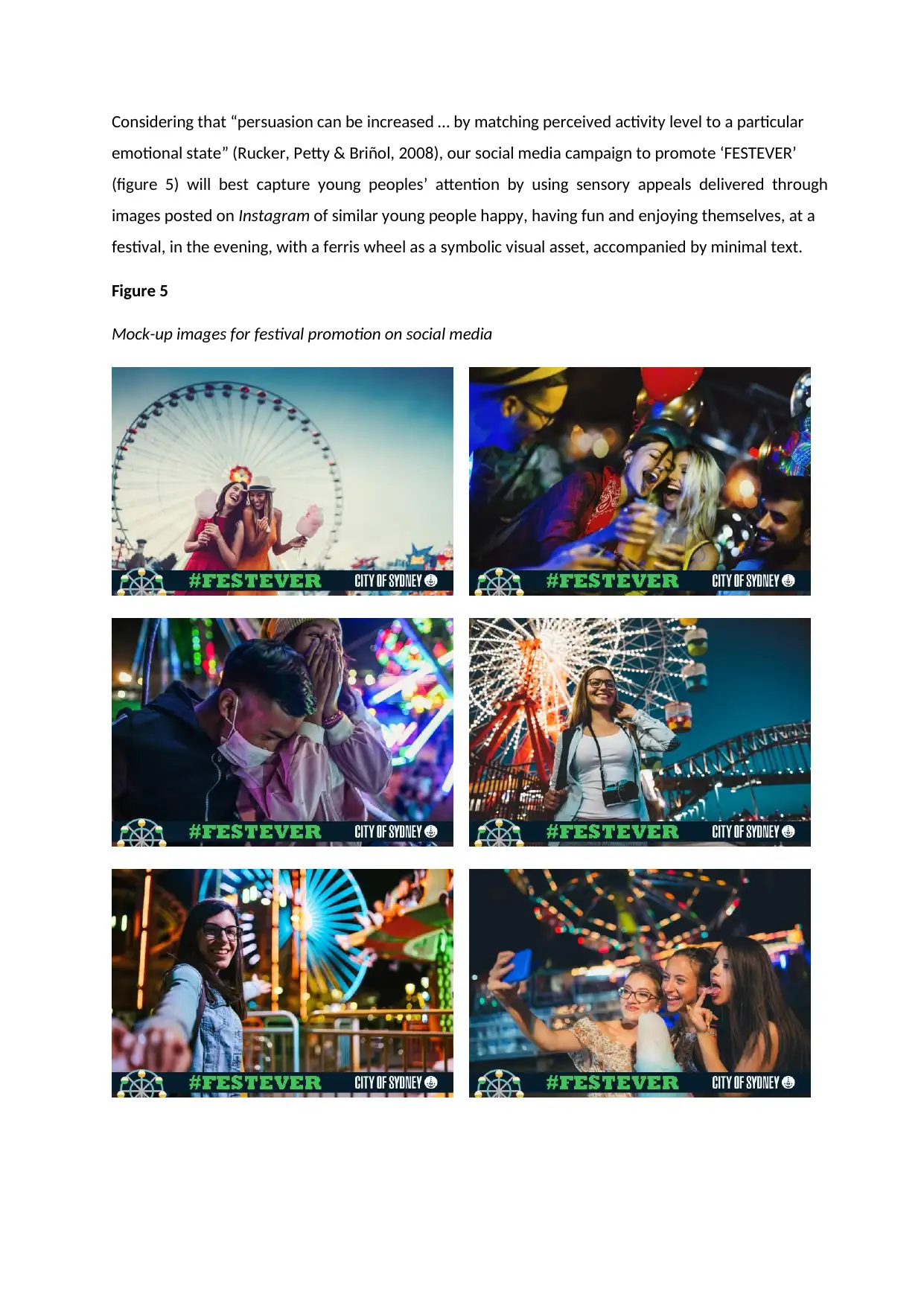

Considering that “persuasion can be increased … by matching perceived activity level to a particular

emotional state” (Rucker, Petty & Briñol, 2008), our social media campaign to promote ‘FESTEVER’

(figure 5) will best capture young peoples’ attention by using sensory appeals delivered through

images posted on Instagram of similar young people happy, having fun and enjoying themselves, at a

festival, in the evening, with a ferris wheel as a symbolic visual asset, accompanied by minimal text.

Figure 5

Mock-up images for festival promotion on social media

emotional state” (Rucker, Petty & Briñol, 2008), our social media campaign to promote ‘FESTEVER’

(figure 5) will best capture young peoples’ attention by using sensory appeals delivered through

images posted on Instagram of similar young people happy, having fun and enjoying themselves, at a

festival, in the evening, with a ferris wheel as a symbolic visual asset, accompanied by minimal text.

Figure 5

Mock-up images for festival promotion on social media

References

Amar, S. The bedside dream dictionary, cited in Dream Encyclopedia.

https://www.dreamencyclopedia.net/ferris-wheel

Argyrou, O. (2021, August 9). City of Sydney - Chat with Olga Argyrou [recording] UTS Kaltura.

https://kaltura.uts.edu.au/media/City+of+Sydney+-+Chat+with+Olga+Argyrou/1_88fl3j93

Baker, P. (2020, March 31). We can’t go back to normal: how will coronavirus change the world? The

Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/31/how-will-the-world-emerge-

from-the-coronavirus-crisis.

Baumeister, R. F. & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as

a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), pp. 497–529.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Cialdini, R. B. & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: compliance and conformity. Annual Review

of Psychology, 55(1), pp. 591–621.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015

City of Sydney (2020, June). Community Recovery Plan. pp. 14-16.

https://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/-/media/corporate/files/2020-07-migrated/files_c-

1/community-recovery-plan.pdf

Cocking, C., Drury, J. & Reicher, S. (2009). The nature of collective resilience: survivor reactions to

the 2005 London bombings. International Journal of Mass Emergency Disasters, 27, pp. 66–

95.

Cormack, P. (1992), cited in Hixson, E. (2014, October). The impact of young people's participation in

events: developing a model of social event impact. International Journal of Event and

Festival Management, 5(3), p. 7. https://core.ac.uk/download/29018885.pdf

Cox, J. cited in Fromm, J. & Read, A. (2018). Marketing to Gen Z: The Rules for Reaching This Vast -

And Very Different - Generation of Influencers [ebook]. ProQuest Ebook Central. pp. 28-29.

http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uts/detail.action?docID=5275471

Deloitte (2021). The Deloitte Global 2021 Millennial and Gen Z Survey. pp. 8-9, 12.

https://deloitte.com/millennialsurvey

Amar, S. The bedside dream dictionary, cited in Dream Encyclopedia.

https://www.dreamencyclopedia.net/ferris-wheel

Argyrou, O. (2021, August 9). City of Sydney - Chat with Olga Argyrou [recording] UTS Kaltura.

https://kaltura.uts.edu.au/media/City+of+Sydney+-+Chat+with+Olga+Argyrou/1_88fl3j93

Baker, P. (2020, March 31). We can’t go back to normal: how will coronavirus change the world? The

Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/31/how-will-the-world-emerge-

from-the-coronavirus-crisis.

Baumeister, R. F. & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as

a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), pp. 497–529.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Cialdini, R. B. & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: compliance and conformity. Annual Review

of Psychology, 55(1), pp. 591–621.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015

City of Sydney (2020, June). Community Recovery Plan. pp. 14-16.

https://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/-/media/corporate/files/2020-07-migrated/files_c-

1/community-recovery-plan.pdf

Cocking, C., Drury, J. & Reicher, S. (2009). The nature of collective resilience: survivor reactions to

the 2005 London bombings. International Journal of Mass Emergency Disasters, 27, pp. 66–

95.

Cormack, P. (1992), cited in Hixson, E. (2014, October). The impact of young people's participation in

events: developing a model of social event impact. International Journal of Event and

Festival Management, 5(3), p. 7. https://core.ac.uk/download/29018885.pdf

Cox, J. cited in Fromm, J. & Read, A. (2018). Marketing to Gen Z: The Rules for Reaching This Vast -

And Very Different - Generation of Influencers [ebook]. ProQuest Ebook Central. pp. 28-29.

http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uts/detail.action?docID=5275471

Deloitte (2021). The Deloitte Global 2021 Millennial and Gen Z Survey. pp. 8-9, 12.

https://deloitte.com/millennialsurvey

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Derrett, R. (2003), cited in Hixson, E. (2014, October). The impact of young people's participation in

events: developing a model of social event impact. International Journal of Event and

Festival Management, 5(3), p. 1. https://core.ac.uk/download/29018885.pdf

Fromm, J. & Garton, C. (2013). Marketing to Millennials: Reach the Largest and Most Influential

Generation of Consumers Ever. American Management Association, p. 54.

Fromm, J. & Read, A. (2018). Marketing to Gen Z: The Rules for Reaching This Vast - And Very

Different - Generation of Influencers [ebook]. ProQuest Ebook Central. pp. 14, 27-28, 30.

http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uts/detail.action?docID=5275471

Hoyer, W.D., MacInnis, D.J. & Pieters, R. (2018). Consumer Behaviour, 7th edition. Cengage Learning,

USA, p. 323.

Lennox, M. Complete dictionary of dreams, cited in Dream Encyclopedia.

https://www.dreamencyclopedia.net/ferris-wheel

Lobo, R. (2014). Millennials: the perfect consumers? The New Economy.

https://www.theneweconomy.com/strategy/millennials-the-perfect-consumers

Morris, B. (2013, January 2). 10 colors that increase sales, and why. Business 2 Community.

https://www.business2community.com/marketing/10-colors-that-increase-sales-and-why-

0366997

Nikodemska-Wołowik, A. M., Bednarz, J. & Foreman, J. R. (2019). Trends in young consumers’

behaviour - implications for family enterprises. Journal of Scientific Papers: Economics &

Sociology, 12(3), p. 14. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2019/12-3/1

Pacific Micromarketing (2012). MOSAIC Group Summary Descriptions [slides]. Creative Victoria.

https://creative.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/powerpoint_doc/0009/56538/MOSAIC_Groups_Sl

ides.ppt

Quester, P., Pettigrew, S., Rao Hill, S., Kopanidis, F. & Hawkins, D. (2013). Consumer Behaviour:

Implications for Marketing Strategy [ebook]. McGraw-Hill Education, Australia.

Rucker, D., Petty, R. & Briñol, P. (2008). What’s in a frame anyway?: a meta-cognitive analysis of

the impact of one versus two sided message framing on attitude certainty. Journal of

Consumer Psychology, 18(2), pp. 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2008.01.008

Solomon, M. (2017). Consumer Behaviour: Buying, Having & Being, 12th edition. Pearson Education,

England, pp. 286-324.

events: developing a model of social event impact. International Journal of Event and

Festival Management, 5(3), p. 1. https://core.ac.uk/download/29018885.pdf

Fromm, J. & Garton, C. (2013). Marketing to Millennials: Reach the Largest and Most Influential

Generation of Consumers Ever. American Management Association, p. 54.

Fromm, J. & Read, A. (2018). Marketing to Gen Z: The Rules for Reaching This Vast - And Very

Different - Generation of Influencers [ebook]. ProQuest Ebook Central. pp. 14, 27-28, 30.

http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uts/detail.action?docID=5275471

Hoyer, W.D., MacInnis, D.J. & Pieters, R. (2018). Consumer Behaviour, 7th edition. Cengage Learning,

USA, p. 323.

Lennox, M. Complete dictionary of dreams, cited in Dream Encyclopedia.

https://www.dreamencyclopedia.net/ferris-wheel

Lobo, R. (2014). Millennials: the perfect consumers? The New Economy.

https://www.theneweconomy.com/strategy/millennials-the-perfect-consumers

Morris, B. (2013, January 2). 10 colors that increase sales, and why. Business 2 Community.

https://www.business2community.com/marketing/10-colors-that-increase-sales-and-why-

0366997

Nikodemska-Wołowik, A. M., Bednarz, J. & Foreman, J. R. (2019). Trends in young consumers’

behaviour - implications for family enterprises. Journal of Scientific Papers: Economics &

Sociology, 12(3), p. 14. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2019/12-3/1

Pacific Micromarketing (2012). MOSAIC Group Summary Descriptions [slides]. Creative Victoria.

https://creative.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/powerpoint_doc/0009/56538/MOSAIC_Groups_Sl

ides.ppt

Quester, P., Pettigrew, S., Rao Hill, S., Kopanidis, F. & Hawkins, D. (2013). Consumer Behaviour:

Implications for Marketing Strategy [ebook]. McGraw-Hill Education, Australia.

Rucker, D., Petty, R. & Briñol, P. (2008). What’s in a frame anyway?: a meta-cognitive analysis of

the impact of one versus two sided message framing on attitude certainty. Journal of

Consumer Psychology, 18(2), pp. 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2008.01.008

Solomon, M. (2017). Consumer Behaviour: Buying, Having & Being, 12th edition. Pearson Education,

England, pp. 286-324.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Underwood, M., cited in Fromm, J. & Read, A. (2018). Marketing to Gen Z : The Rules for Reaching

This Vast - And Very Different - Generation of Influencers [ebook]. ProQuest Ebook Central.

p. 41. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uts/detail.action?docID=5275471

Vos, L. (2020, September 25). Semiotics in marketing: what it means for your brand and messaging.

CXL. https://cxl.com/blog/semiotics-marketing/

This Vast - And Very Different - Generation of Influencers [ebook]. ProQuest Ebook Central.

p. 41. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uts/detail.action?docID=5275471

Vos, L. (2020, September 25). Semiotics in marketing: what it means for your brand and messaging.

CXL. https://cxl.com/blog/semiotics-marketing/

1 out of 11

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.