Analyzing Safety Case Regime for Risk Management in Hazard Facilities

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/11

|14

|3357

|169

Report

AI Summary

This report examines the Safety Case Regime and its crucial role in risk management, particularly within Major Hazard Facilities (MHFs). It defines the Safety Case as a document outlining workplace hazards, risks, control measures, and safety management systems. Key risk management features of the regime include addressing risks inherent in the workplace and providing a performance-based system to ensure safe operations. The report emphasizes the regime's ability to allow MHFs to modify their risk management systems, promoting greater responsibility for worker safety. It highlights the importance of identifying and managing operating protocols to maintain risks at the lowest achievable level. The Safety Case Regime's core concepts encompass regulations applicable to MHFs, offering a performance-based approach for operators to identify and implement proper controls. The report also discusses the reduction of risk to a reasonably practicable level, balancing risk reduction against time, challenges, and expenses. Furthermore, the report analyzes how the Safety Case Regime could have potentially prevented the Piper Alpha Oil and Gas platform explosion in 1988, emphasizing the importance of communication, maintenance, and safety protocols.

Running head: Safety Case Regime

Risk Management

-Safety Case Regime

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Author Note

Risk Management

-Safety Case Regime

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Author Note

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1Safety case regime

Safety Case Regime and its role in Risk Management:

Safety Case can be understood as a document that is produced by the facility’s

operator, in which the hazards and risks of the workplace, control measures for those risks

and the safety management systems that are in place to ensure such control are being properly

used/applied. According to the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental

Management Authority (NOPSEMA), the safety cases must be presented by the operator of

installations, the documents should outline all the important aspects (both managerial and

technical) of the facility, outlining the performance standards for the operation in critical

aspects of the operation, involve the workforce of the installation and moreover should be

prepared keeping in mind that the documents are liable to be scrutinized by an independent

and competent regulator (nopsema.gov.au 2018; Hopkins 2015; Mearns et al. 2003).

Facilities that frequently work with large amounts of dangerous substances have risks

of major accidents, and the consequence of these accidents may be in the scale of natural

disaster in terms of fatalities, injuries and property damage. Facilities where such risks are

high are called the Major hazard facilities (Nicol 2001). Since these facilities have only rare

occurrences of Catastrophic events, this can lead to a condition where adequate attention are

not given to assess the risks of major incidents, compared to the regular operational

challenges (Briassoulis and Papazoglou 1993). The Safety Case Regime acts as a regulatory

mechanism that focuses on the potential of these major and catastrophic incidents (Leveson

2011).

Key risk management features of the safety case regime in reducing the risk of major

accidents

The key features of risk management under the safety case regime that can

reduce the risks of major accidents include: risk management systems that addresses

Safety Case Regime and its role in Risk Management:

Safety Case can be understood as a document that is produced by the facility’s

operator, in which the hazards and risks of the workplace, control measures for those risks

and the safety management systems that are in place to ensure such control are being properly

used/applied. According to the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental

Management Authority (NOPSEMA), the safety cases must be presented by the operator of

installations, the documents should outline all the important aspects (both managerial and

technical) of the facility, outlining the performance standards for the operation in critical

aspects of the operation, involve the workforce of the installation and moreover should be

prepared keeping in mind that the documents are liable to be scrutinized by an independent

and competent regulator (nopsema.gov.au 2018; Hopkins 2015; Mearns et al. 2003).

Facilities that frequently work with large amounts of dangerous substances have risks

of major accidents, and the consequence of these accidents may be in the scale of natural

disaster in terms of fatalities, injuries and property damage. Facilities where such risks are

high are called the Major hazard facilities (Nicol 2001). Since these facilities have only rare

occurrences of Catastrophic events, this can lead to a condition where adequate attention are

not given to assess the risks of major incidents, compared to the regular operational

challenges (Briassoulis and Papazoglou 1993). The Safety Case Regime acts as a regulatory

mechanism that focuses on the potential of these major and catastrophic incidents (Leveson

2011).

Key risk management features of the safety case regime in reducing the risk of major

accidents

The key features of risk management under the safety case regime that can

reduce the risks of major accidents include: risk management systems that addresses

2Safety case regime

the risks inherent in a workplace and the provision of a performance based regime

which can help the facility operator to ensure safe operations of the facility, analyzing

how effective the control strategies are and implement them in practice.

One of the major risk management features of the Safety Case Regime is that it allows

the MHF to modify their risk management systems, enabling them to address the risks in a

more wholesome way. Under the regime, the facilities are required to assume more

responsibilities towards the safety of the workers and the workplace identify and manage all

the operating protocols effectively and exhibit that the risks in the facility are at the lowest

level that can be practically achieved (nopsema.gov.au 2018; worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018).

According to the Australian Ministry of Manpower, Major Hazard Facility (MHF) includes

facilities involved in: petroleum refining, petrochemical manufacturing, chemical processing,

storage and usage of large quantities of flammable substances. Facilities are also identified as

MHF depending on the nature of the work and the inventory levels (exceeding threshold

amount) of dangerous substances that are there or likely to be there in the facility

(safeworkaustralia.gov.au 2018). The MHF can be considered as an environment of high

hazard levels. Even though the risks of major accidents are low, the presence of dangerous

substances and the complicated operating processes can result in catastrophic results

(worksafe.qld.gov.au 2018). The Safety Case Regime allows the MHF to modify their risk

management systems, enabling them to address the risks in a more wholesome way. Under

the regime, the facilities are required to assume more responsibilities towards the safety of

the workers and the workplace identify and manage all the operating protocols effectively

and exhibit that the risks in the facility are at the lowest level that can be practically achieved

(nopsema.gov.au 2018; worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018).

The core concepts of the safety regime include different aspects of regulations

applicable for MHF. It provides a performance based regime using which the operator of the

the risks inherent in a workplace and the provision of a performance based regime

which can help the facility operator to ensure safe operations of the facility, analyzing

how effective the control strategies are and implement them in practice.

One of the major risk management features of the Safety Case Regime is that it allows

the MHF to modify their risk management systems, enabling them to address the risks in a

more wholesome way. Under the regime, the facilities are required to assume more

responsibilities towards the safety of the workers and the workplace identify and manage all

the operating protocols effectively and exhibit that the risks in the facility are at the lowest

level that can be practically achieved (nopsema.gov.au 2018; worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018).

According to the Australian Ministry of Manpower, Major Hazard Facility (MHF) includes

facilities involved in: petroleum refining, petrochemical manufacturing, chemical processing,

storage and usage of large quantities of flammable substances. Facilities are also identified as

MHF depending on the nature of the work and the inventory levels (exceeding threshold

amount) of dangerous substances that are there or likely to be there in the facility

(safeworkaustralia.gov.au 2018). The MHF can be considered as an environment of high

hazard levels. Even though the risks of major accidents are low, the presence of dangerous

substances and the complicated operating processes can result in catastrophic results

(worksafe.qld.gov.au 2018). The Safety Case Regime allows the MHF to modify their risk

management systems, enabling them to address the risks in a more wholesome way. Under

the regime, the facilities are required to assume more responsibilities towards the safety of

the workers and the workplace identify and manage all the operating protocols effectively

and exhibit that the risks in the facility are at the lowest level that can be practically achieved

(nopsema.gov.au 2018; worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018).

The core concepts of the safety regime include different aspects of regulations

applicable for MHF. It provides a performance based regime using which the operator of the

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3Safety case regime

facility can identify proper controls for safe operation of the facility, analyze how adequate

the controls are, and also strategies to implement and maintain the controls in place, which

are described in the safety case. The operator also has the responsibility to ensure that the

facility is operating safely (Sefton 1994). The facility will be provided the license to operate

only after the operator complies with the regulatory duties and have shown the ability to

operate the facility with safety. The regulations also outline duties that can reduce the risks at

the workplace as much as practically possible. It is also vital that operators are able to

develop their own specific standards of performance, based on the outlined duties. The

regulations can ensure safe operation of the facility through the use to sufficient control

techniques and the use of Safety Management Systems (SMS) that can support and maintain

a safe workplace (Knapp and Lincoln 2016). These strategies need to be based upon a

complete understanding of the risks of major accidents which can be identified from Safety

Assessment and Hazard Identification processes (Ericson 2015). The safety case should

reflect the organizational culture, operational and safety philosophies, risk profiles of the

facility, and thus the operator should be able to clearly identify them, and kept in mind while

preparing the safety case. The safety case also should be am integrated process instead of

series of discrete studies. The aspects of the safety case should relate to the different factors

involved in major hazard in the facility (worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018).

Role of Safety Case Regime in reducing the risk of major Accidents

The focus on the reduction of risk to a level that is practicable reasonably involves the

reduction of risks to be balanced against time, challenges and expenses to achieve it. This

requires the consideration of different aspects such as the probability of a hazard or a risk

causing an incident, the extent of damage caused by such incidents and what is known or

should be known by the operator and workers about these risks and hazards and identify

strategies which can be used to reduce the risks or hazards (Leveson 2011). The efficacy,

facility can identify proper controls for safe operation of the facility, analyze how adequate

the controls are, and also strategies to implement and maintain the controls in place, which

are described in the safety case. The operator also has the responsibility to ensure that the

facility is operating safely (Sefton 1994). The facility will be provided the license to operate

only after the operator complies with the regulatory duties and have shown the ability to

operate the facility with safety. The regulations also outline duties that can reduce the risks at

the workplace as much as practically possible. It is also vital that operators are able to

develop their own specific standards of performance, based on the outlined duties. The

regulations can ensure safe operation of the facility through the use to sufficient control

techniques and the use of Safety Management Systems (SMS) that can support and maintain

a safe workplace (Knapp and Lincoln 2016). These strategies need to be based upon a

complete understanding of the risks of major accidents which can be identified from Safety

Assessment and Hazard Identification processes (Ericson 2015). The safety case should

reflect the organizational culture, operational and safety philosophies, risk profiles of the

facility, and thus the operator should be able to clearly identify them, and kept in mind while

preparing the safety case. The safety case also should be am integrated process instead of

series of discrete studies. The aspects of the safety case should relate to the different factors

involved in major hazard in the facility (worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018).

Role of Safety Case Regime in reducing the risk of major Accidents

The focus on the reduction of risk to a level that is practicable reasonably involves the

reduction of risks to be balanced against time, challenges and expenses to achieve it. This

requires the consideration of different aspects such as the probability of a hazard or a risk

causing an incident, the extent of damage caused by such incidents and what is known or

should be known by the operator and workers about these risks and hazards and identify

strategies which can be used to reduce the risks or hazards (Leveson 2011). The efficacy,

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4Safety case regime

suitability and the availability of these strategies and measures also should be considered

along with the expenses related to the reduction or elimination of the risks or hazards in the

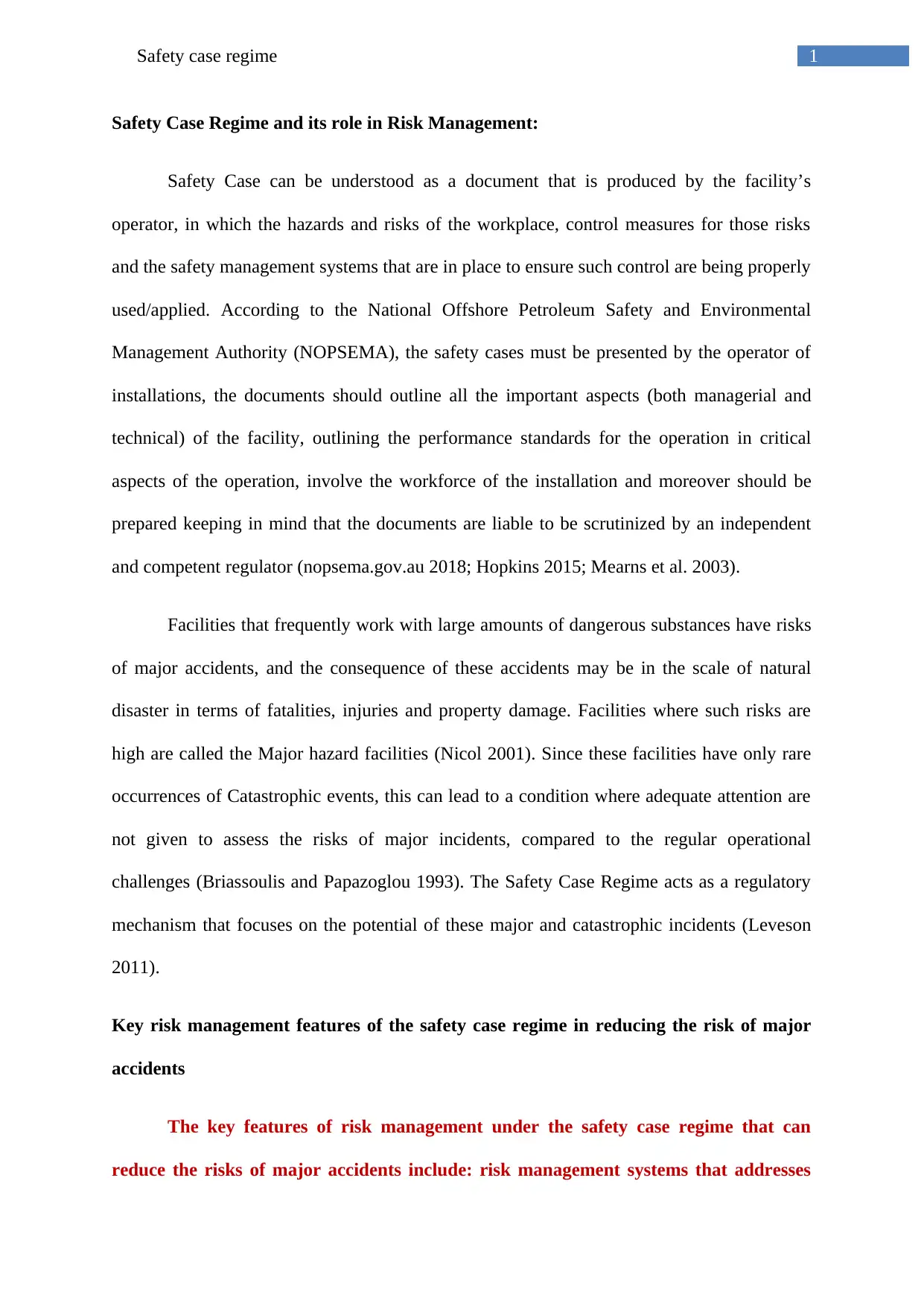

workplace. The risks can be categorized into 4 groups based on its frequency and

consequence: major hazard risks (low frequency high consequence), very high risks (high

frequency and high consequence), Minor risks (low frequency and consequence) and OHS

risks (high frequency and low consequence) (worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018; Khan 2017)

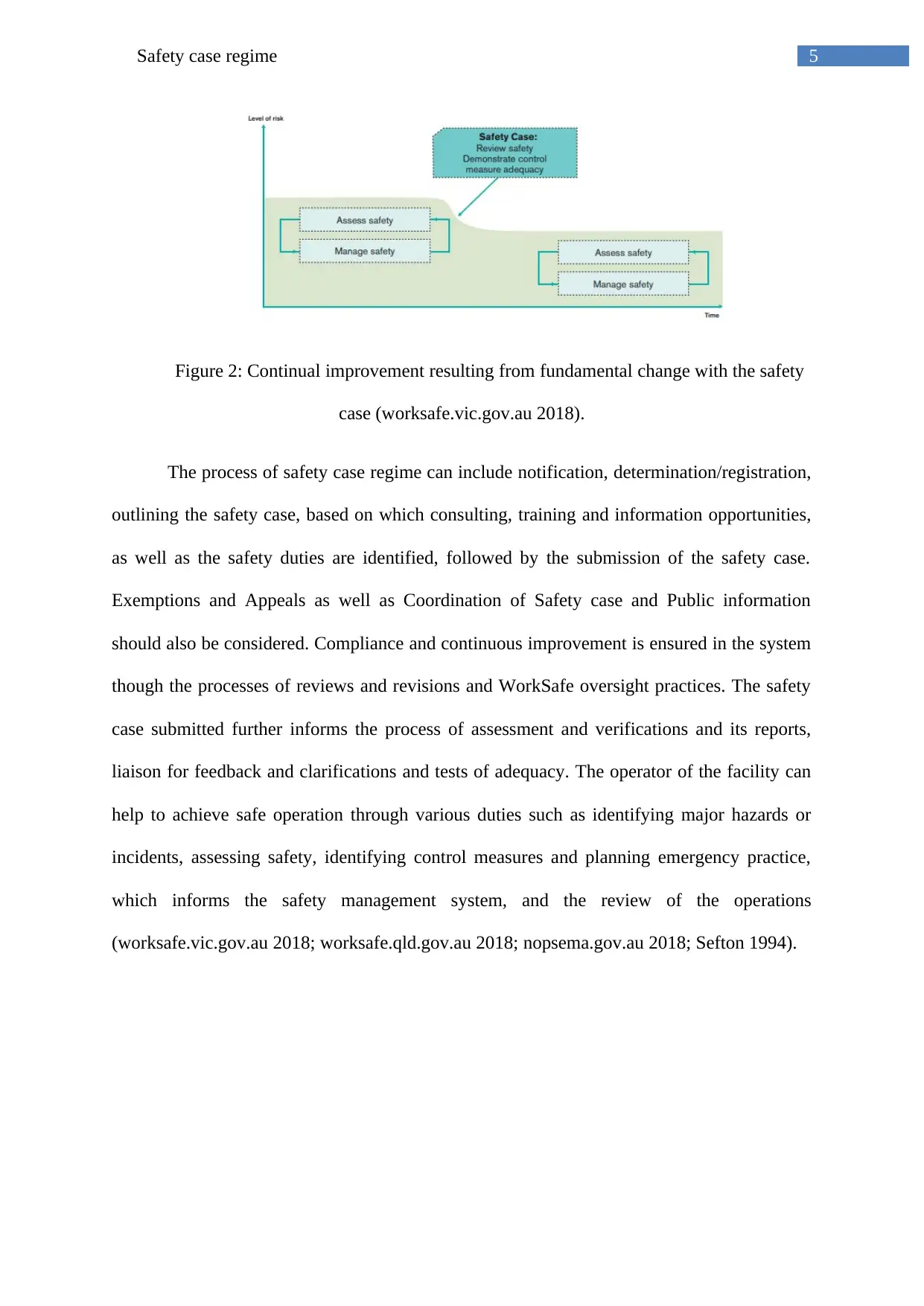

Figure 1: Focus of safety case; source: (worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018).

The objectives of the Regime are to ensure the safe operation of MHF and reduce the

risks of major incidents, and thus should be prepared by the operator of the facility outlining

the safe operation of the facility, which can be followed by the workers. However, the regime

should not reduce the focus on the Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) issues, which

usually are more frequent but with lower potential of adverse consequences, and instead the

regime ensures that preventative measures of major incidents are also focused on and utilized

in all facilities to which it is relevant. Continual improvement can also be ensured in the

safety case through constant assessment and management of safety, in which safety practices

can be reviewed, control measures demonstrated and its adequacy measured to identify scope

for further improvement (worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018).

suitability and the availability of these strategies and measures also should be considered

along with the expenses related to the reduction or elimination of the risks or hazards in the

workplace. The risks can be categorized into 4 groups based on its frequency and

consequence: major hazard risks (low frequency high consequence), very high risks (high

frequency and high consequence), Minor risks (low frequency and consequence) and OHS

risks (high frequency and low consequence) (worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018; Khan 2017)

Figure 1: Focus of safety case; source: (worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018).

The objectives of the Regime are to ensure the safe operation of MHF and reduce the

risks of major incidents, and thus should be prepared by the operator of the facility outlining

the safe operation of the facility, which can be followed by the workers. However, the regime

should not reduce the focus on the Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) issues, which

usually are more frequent but with lower potential of adverse consequences, and instead the

regime ensures that preventative measures of major incidents are also focused on and utilized

in all facilities to which it is relevant. Continual improvement can also be ensured in the

safety case through constant assessment and management of safety, in which safety practices

can be reviewed, control measures demonstrated and its adequacy measured to identify scope

for further improvement (worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018).

5Safety case regime

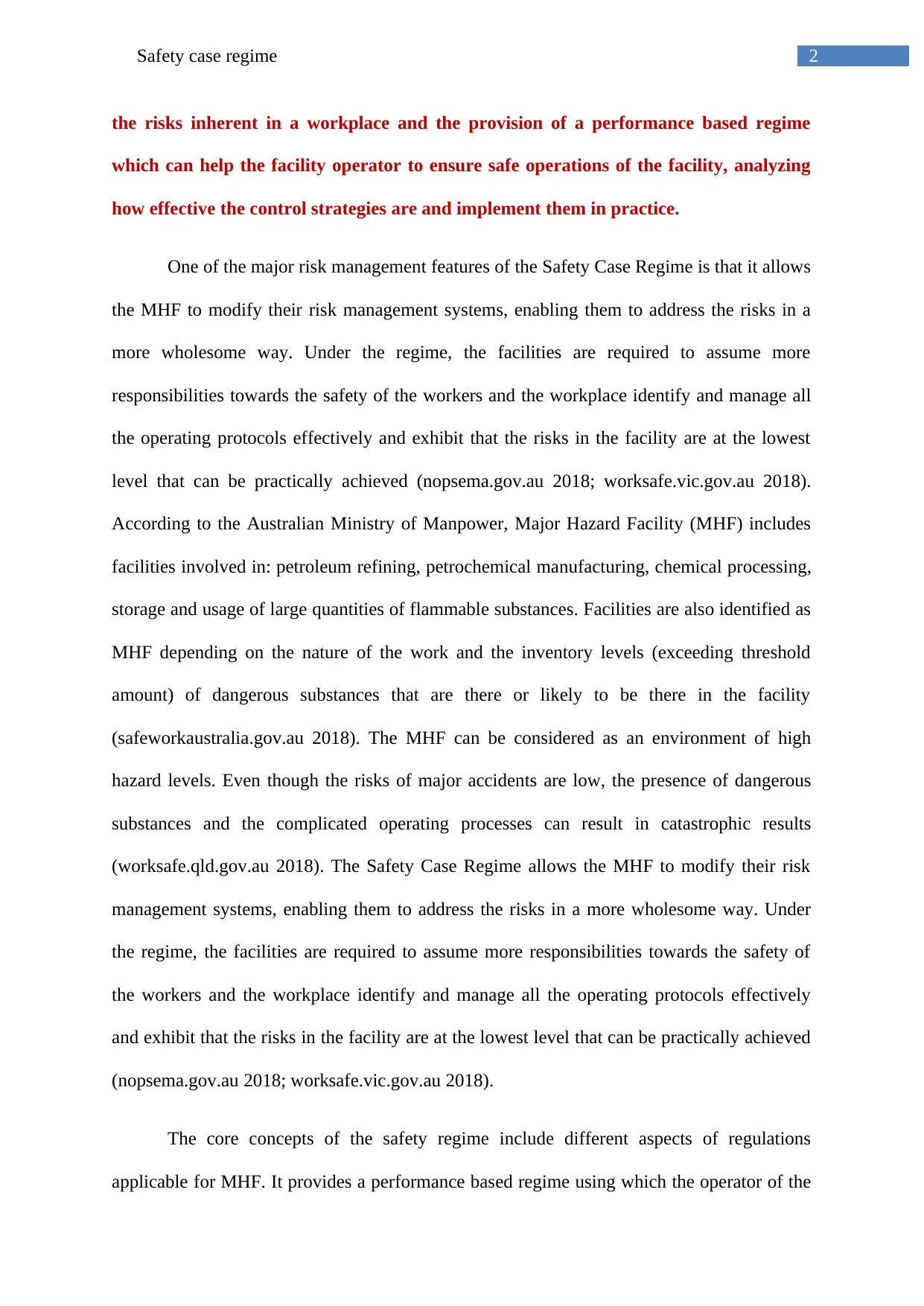

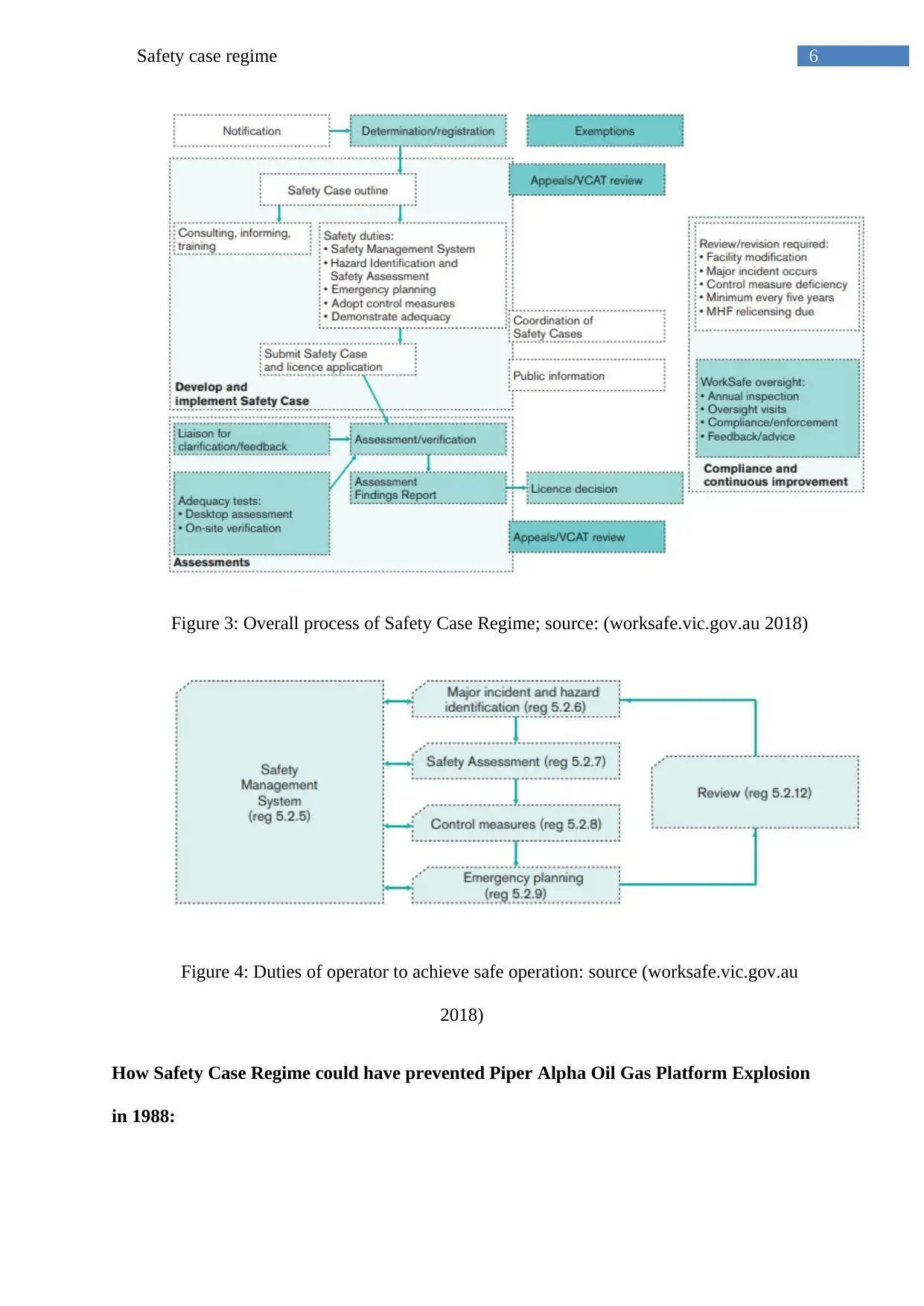

Figure 2: Continual improvement resulting from fundamental change with the safety

case (worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018).

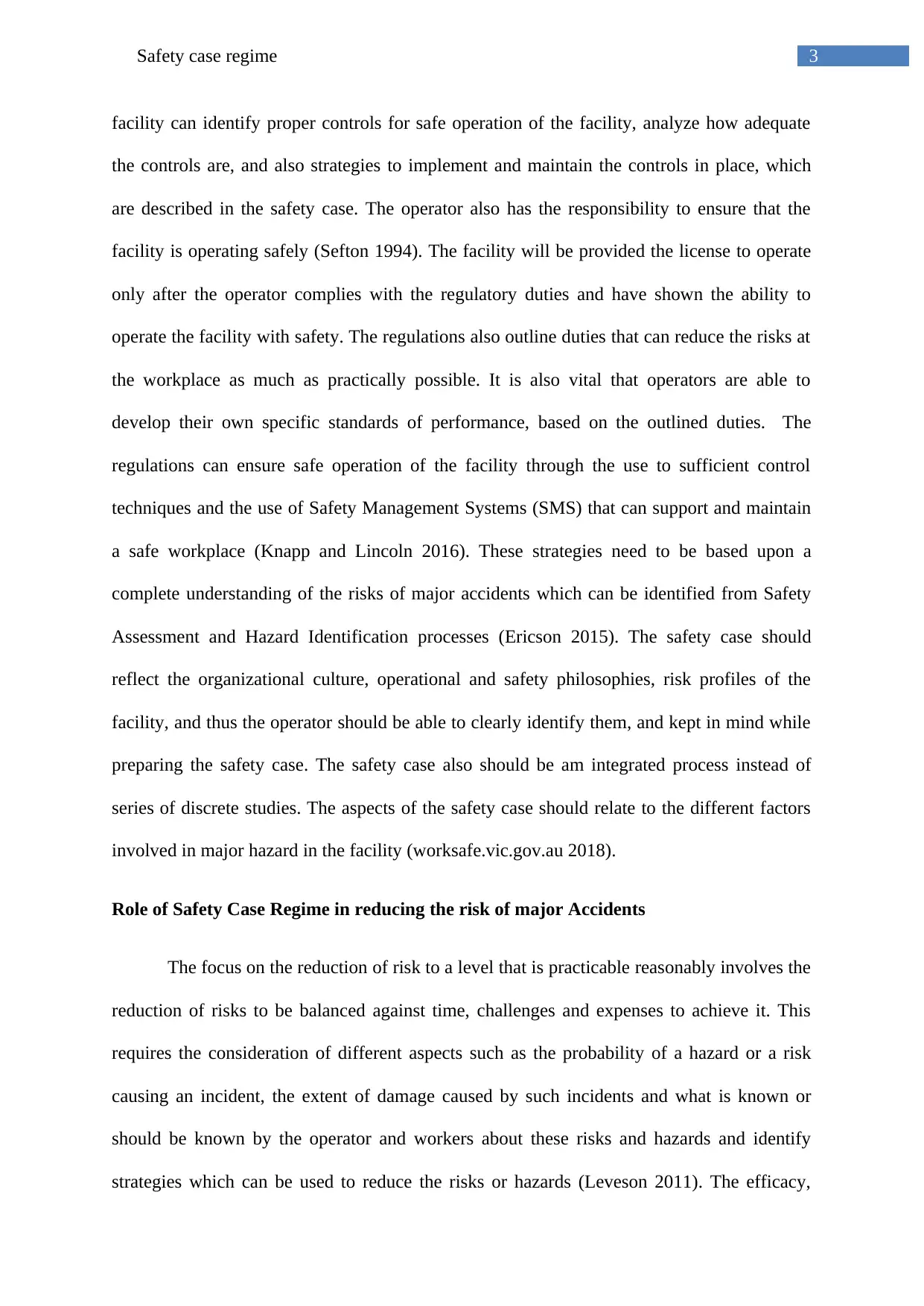

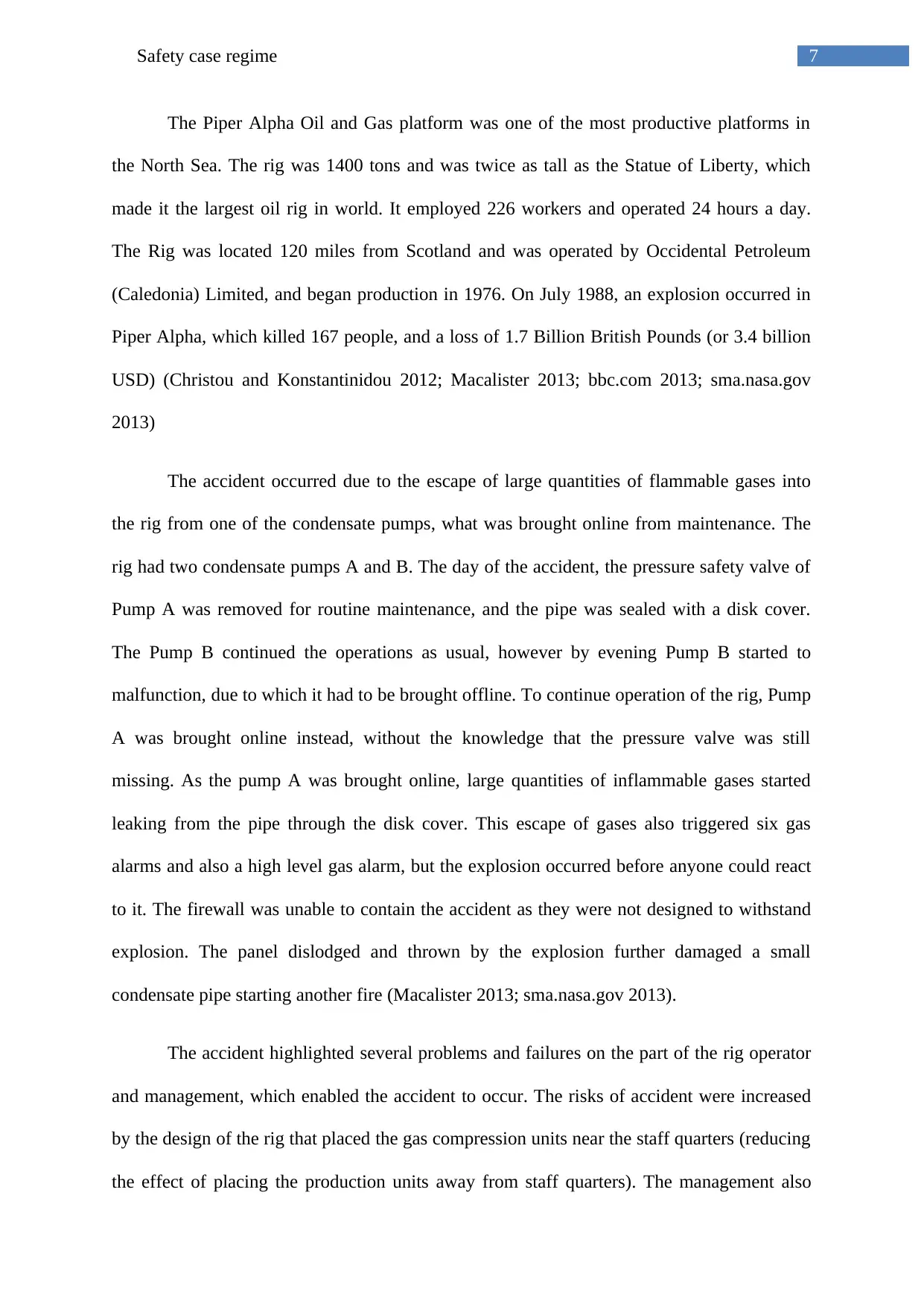

The process of safety case regime can include notification, determination/registration,

outlining the safety case, based on which consulting, training and information opportunities,

as well as the safety duties are identified, followed by the submission of the safety case.

Exemptions and Appeals as well as Coordination of Safety case and Public information

should also be considered. Compliance and continuous improvement is ensured in the system

though the processes of reviews and revisions and WorkSafe oversight practices. The safety

case submitted further informs the process of assessment and verifications and its reports,

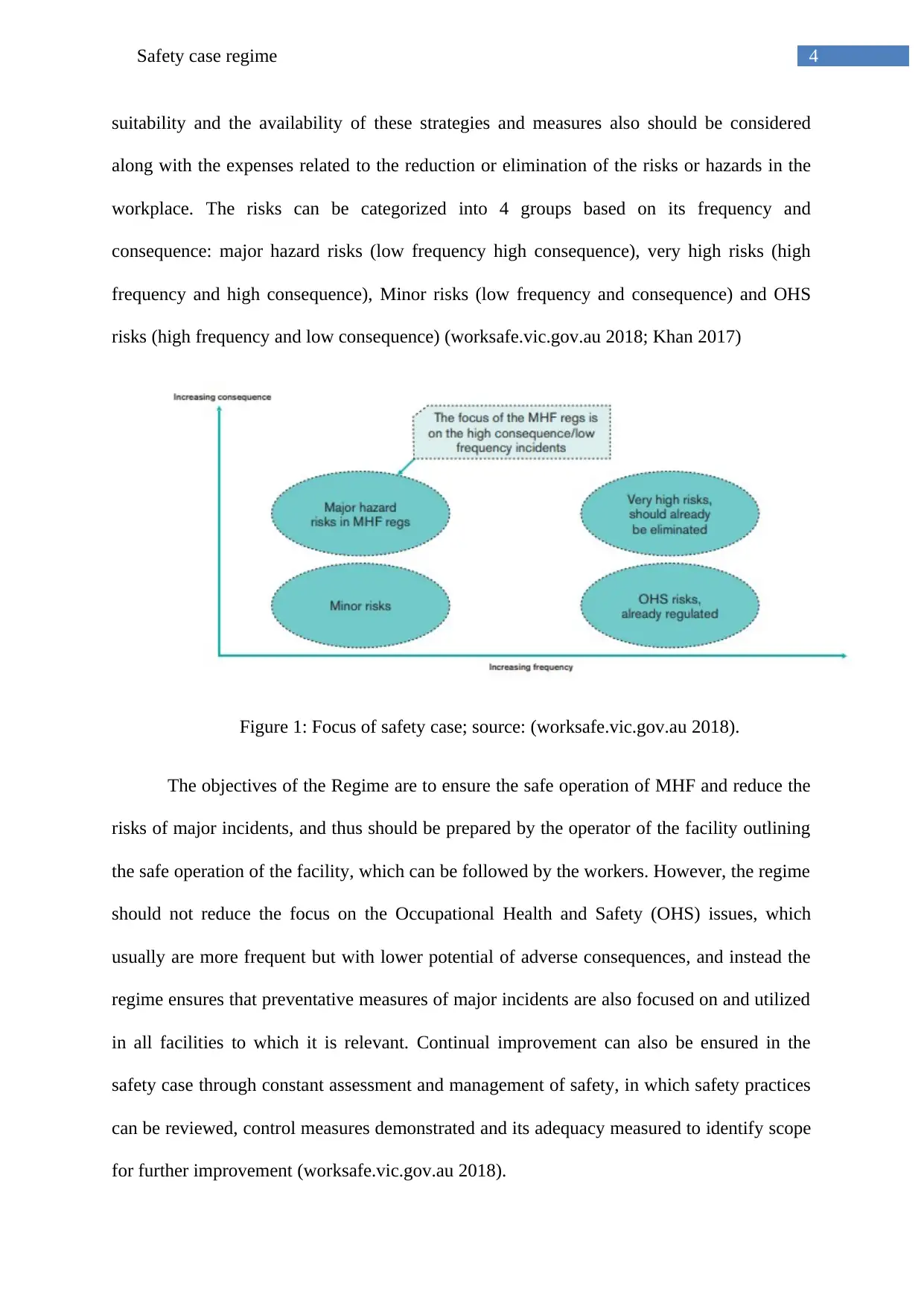

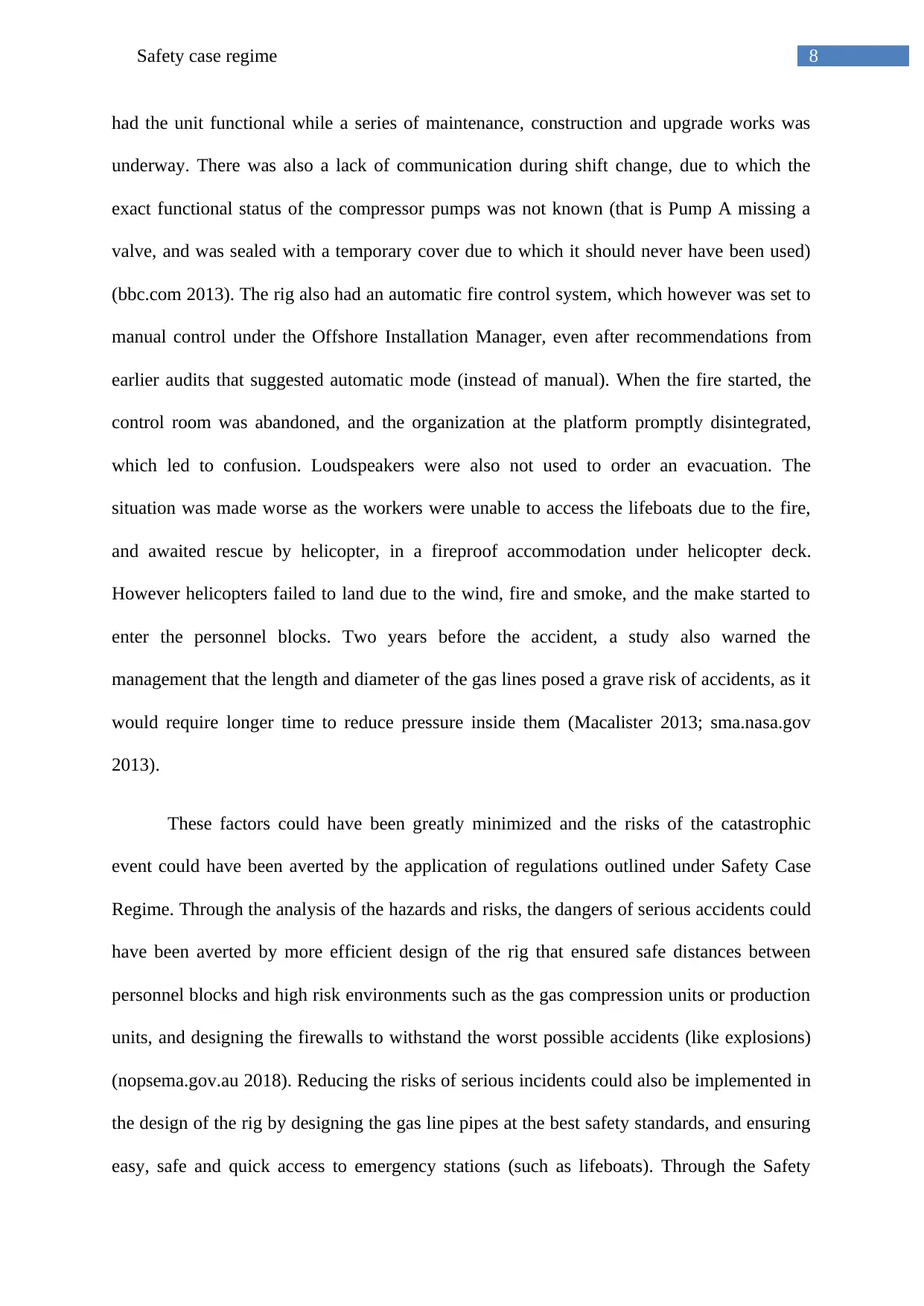

liaison for feedback and clarifications and tests of adequacy. The operator of the facility can

help to achieve safe operation through various duties such as identifying major hazards or

incidents, assessing safety, identifying control measures and planning emergency practice,

which informs the safety management system, and the review of the operations

(worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018; worksafe.qld.gov.au 2018; nopsema.gov.au 2018; Sefton 1994).

Figure 2: Continual improvement resulting from fundamental change with the safety

case (worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018).

The process of safety case regime can include notification, determination/registration,

outlining the safety case, based on which consulting, training and information opportunities,

as well as the safety duties are identified, followed by the submission of the safety case.

Exemptions and Appeals as well as Coordination of Safety case and Public information

should also be considered. Compliance and continuous improvement is ensured in the system

though the processes of reviews and revisions and WorkSafe oversight practices. The safety

case submitted further informs the process of assessment and verifications and its reports,

liaison for feedback and clarifications and tests of adequacy. The operator of the facility can

help to achieve safe operation through various duties such as identifying major hazards or

incidents, assessing safety, identifying control measures and planning emergency practice,

which informs the safety management system, and the review of the operations

(worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018; worksafe.qld.gov.au 2018; nopsema.gov.au 2018; Sefton 1994).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6Safety case regime

Figure 3: Overall process of Safety Case Regime; source: (worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018)

Figure 4: Duties of operator to achieve safe operation: source (worksafe.vic.gov.au

2018)

How Safety Case Regime could have prevented Piper Alpha Oil Gas Platform Explosion

in 1988:

Figure 3: Overall process of Safety Case Regime; source: (worksafe.vic.gov.au 2018)

Figure 4: Duties of operator to achieve safe operation: source (worksafe.vic.gov.au

2018)

How Safety Case Regime could have prevented Piper Alpha Oil Gas Platform Explosion

in 1988:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7Safety case regime

The Piper Alpha Oil and Gas platform was one of the most productive platforms in

the North Sea. The rig was 1400 tons and was twice as tall as the Statue of Liberty, which

made it the largest oil rig in world. It employed 226 workers and operated 24 hours a day.

The Rig was located 120 miles from Scotland and was operated by Occidental Petroleum

(Caledonia) Limited, and began production in 1976. On July 1988, an explosion occurred in

Piper Alpha, which killed 167 people, and a loss of 1.7 Billion British Pounds (or 3.4 billion

USD) (Christou and Konstantinidou 2012; Macalister 2013; bbc.com 2013; sma.nasa.gov

2013)

The accident occurred due to the escape of large quantities of flammable gases into

the rig from one of the condensate pumps, what was brought online from maintenance. The

rig had two condensate pumps A and B. The day of the accident, the pressure safety valve of

Pump A was removed for routine maintenance, and the pipe was sealed with a disk cover.

The Pump B continued the operations as usual, however by evening Pump B started to

malfunction, due to which it had to be brought offline. To continue operation of the rig, Pump

A was brought online instead, without the knowledge that the pressure valve was still

missing. As the pump A was brought online, large quantities of inflammable gases started

leaking from the pipe through the disk cover. This escape of gases also triggered six gas

alarms and also a high level gas alarm, but the explosion occurred before anyone could react

to it. The firewall was unable to contain the accident as they were not designed to withstand

explosion. The panel dislodged and thrown by the explosion further damaged a small

condensate pipe starting another fire (Macalister 2013; sma.nasa.gov 2013).

The accident highlighted several problems and failures on the part of the rig operator

and management, which enabled the accident to occur. The risks of accident were increased

by the design of the rig that placed the gas compression units near the staff quarters (reducing

the effect of placing the production units away from staff quarters). The management also

The Piper Alpha Oil and Gas platform was one of the most productive platforms in

the North Sea. The rig was 1400 tons and was twice as tall as the Statue of Liberty, which

made it the largest oil rig in world. It employed 226 workers and operated 24 hours a day.

The Rig was located 120 miles from Scotland and was operated by Occidental Petroleum

(Caledonia) Limited, and began production in 1976. On July 1988, an explosion occurred in

Piper Alpha, which killed 167 people, and a loss of 1.7 Billion British Pounds (or 3.4 billion

USD) (Christou and Konstantinidou 2012; Macalister 2013; bbc.com 2013; sma.nasa.gov

2013)

The accident occurred due to the escape of large quantities of flammable gases into

the rig from one of the condensate pumps, what was brought online from maintenance. The

rig had two condensate pumps A and B. The day of the accident, the pressure safety valve of

Pump A was removed for routine maintenance, and the pipe was sealed with a disk cover.

The Pump B continued the operations as usual, however by evening Pump B started to

malfunction, due to which it had to be brought offline. To continue operation of the rig, Pump

A was brought online instead, without the knowledge that the pressure valve was still

missing. As the pump A was brought online, large quantities of inflammable gases started

leaking from the pipe through the disk cover. This escape of gases also triggered six gas

alarms and also a high level gas alarm, but the explosion occurred before anyone could react

to it. The firewall was unable to contain the accident as they were not designed to withstand

explosion. The panel dislodged and thrown by the explosion further damaged a small

condensate pipe starting another fire (Macalister 2013; sma.nasa.gov 2013).

The accident highlighted several problems and failures on the part of the rig operator

and management, which enabled the accident to occur. The risks of accident were increased

by the design of the rig that placed the gas compression units near the staff quarters (reducing

the effect of placing the production units away from staff quarters). The management also

8Safety case regime

had the unit functional while a series of maintenance, construction and upgrade works was

underway. There was also a lack of communication during shift change, due to which the

exact functional status of the compressor pumps was not known (that is Pump A missing a

valve, and was sealed with a temporary cover due to which it should never have been used)

(bbc.com 2013). The rig also had an automatic fire control system, which however was set to

manual control under the Offshore Installation Manager, even after recommendations from

earlier audits that suggested automatic mode (instead of manual). When the fire started, the

control room was abandoned, and the organization at the platform promptly disintegrated,

which led to confusion. Loudspeakers were also not used to order an evacuation. The

situation was made worse as the workers were unable to access the lifeboats due to the fire,

and awaited rescue by helicopter, in a fireproof accommodation under helicopter deck.

However helicopters failed to land due to the wind, fire and smoke, and the make started to

enter the personnel blocks. Two years before the accident, a study also warned the

management that the length and diameter of the gas lines posed a grave risk of accidents, as it

would require longer time to reduce pressure inside them (Macalister 2013; sma.nasa.gov

2013).

These factors could have been greatly minimized and the risks of the catastrophic

event could have been averted by the application of regulations outlined under Safety Case

Regime. Through the analysis of the hazards and risks, the dangers of serious accidents could

have been averted by more efficient design of the rig that ensured safe distances between

personnel blocks and high risk environments such as the gas compression units or production

units, and designing the firewalls to withstand the worst possible accidents (like explosions)

(nopsema.gov.au 2018). Reducing the risks of serious incidents could also be implemented in

the design of the rig by designing the gas line pipes at the best safety standards, and ensuring

easy, safe and quick access to emergency stations (such as lifeboats). Through the Safety

had the unit functional while a series of maintenance, construction and upgrade works was

underway. There was also a lack of communication during shift change, due to which the

exact functional status of the compressor pumps was not known (that is Pump A missing a

valve, and was sealed with a temporary cover due to which it should never have been used)

(bbc.com 2013). The rig also had an automatic fire control system, which however was set to

manual control under the Offshore Installation Manager, even after recommendations from

earlier audits that suggested automatic mode (instead of manual). When the fire started, the

control room was abandoned, and the organization at the platform promptly disintegrated,

which led to confusion. Loudspeakers were also not used to order an evacuation. The

situation was made worse as the workers were unable to access the lifeboats due to the fire,

and awaited rescue by helicopter, in a fireproof accommodation under helicopter deck.

However helicopters failed to land due to the wind, fire and smoke, and the make started to

enter the personnel blocks. Two years before the accident, a study also warned the

management that the length and diameter of the gas lines posed a grave risk of accidents, as it

would require longer time to reduce pressure inside them (Macalister 2013; sma.nasa.gov

2013).

These factors could have been greatly minimized and the risks of the catastrophic

event could have been averted by the application of regulations outlined under Safety Case

Regime. Through the analysis of the hazards and risks, the dangers of serious accidents could

have been averted by more efficient design of the rig that ensured safe distances between

personnel blocks and high risk environments such as the gas compression units or production

units, and designing the firewalls to withstand the worst possible accidents (like explosions)

(nopsema.gov.au 2018). Reducing the risks of serious incidents could also be implemented in

the design of the rig by designing the gas line pipes at the best safety standards, and ensuring

easy, safe and quick access to emergency stations (such as lifeboats). Through the Safety

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9Safety case regime

Case regime, the management could have focused on the risks of major accidents, and

thereby identify effective strategies to overcome them. The incident showed that the workers

and the management were not completely prepared for such an event, which could have been

avoided through prior planning. The regime also could have allowed the implementation of

training and consulting sessions on safety practices, which could have informed the

operations of the rig, and ensured higher safety levels than that was practiced

(safeworkaustralia.gov.au 2018). The communication error that led to the faulty pump to be

used could have been avoided through Safety case plans that outlined operations of high

hazard. Outlining strategies that could be put in place in case of high risk emergencies could

also have provided vital information to the management and the workers on the actions to be

taken during such emergencies (nopsema.gov.au 2018).

Conclusion:

Overall, the risk of accident in Piper Alpha was greatly increased as the management

and workers were not adequately prepared to handle such an event, and the worst case

scenario was not considered in its operation. This was compounded by certain unsafe

practices and design flaws, as well as a lack of communication and ineffective leadership,

which increased chaos and confusion at the onset of the accident, thereby increasing the

magnitude of damage caused by it. The Safety Case regimen could have allowed the

organization to predict the risks of such events, and help the organization to plan ahead the

safety precautions and strategies to tackle such events to ensure minimal losses to human life

and property.

Case regime, the management could have focused on the risks of major accidents, and

thereby identify effective strategies to overcome them. The incident showed that the workers

and the management were not completely prepared for such an event, which could have been

avoided through prior planning. The regime also could have allowed the implementation of

training and consulting sessions on safety practices, which could have informed the

operations of the rig, and ensured higher safety levels than that was practiced

(safeworkaustralia.gov.au 2018). The communication error that led to the faulty pump to be

used could have been avoided through Safety case plans that outlined operations of high

hazard. Outlining strategies that could be put in place in case of high risk emergencies could

also have provided vital information to the management and the workers on the actions to be

taken during such emergencies (nopsema.gov.au 2018).

Conclusion:

Overall, the risk of accident in Piper Alpha was greatly increased as the management

and workers were not adequately prepared to handle such an event, and the worst case

scenario was not considered in its operation. This was compounded by certain unsafe

practices and design flaws, as well as a lack of communication and ineffective leadership,

which increased chaos and confusion at the onset of the accident, thereby increasing the

magnitude of damage caused by it. The Safety Case regimen could have allowed the

organization to predict the risks of such events, and help the organization to plan ahead the

safety precautions and strategies to tackle such events to ensure minimal losses to human life

and property.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10Safety case regime

References:

bbc.com, 2013. Piper Alpha: In their own words. [online] BBC News. Available at:

http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-22840445 [Accessed 30 May 2018].

Briassoulis, H. and Papazoglou, I., 1993, October. Determining the uses of land in the

vicinity of major hazard facilities: an optimization algorithm. In Proceedings of the IFIP

TC5/WG5. 11 Working Conference on Computer Support for Environmental Impact

Assessment (pp. 177-186). North-Holland Publishing Co..

Christou, M. and Konstantinidou, M., 2012. Safety of offshore oil and gas operations:

Lessons from past accident analysis. Joint Research Centre, European Commission,

Luxembourg.

Ericson, C.A., 2015. Hazard analysis techniques for system safety. John Wiley & Sons.

Hopkins, A., 2015. The cost–benefit hurdle for safety case regulation. Safety Science, 77,

pp.95-101.

Khan, F. and Hashemi, S.J., 2017. Introduction. In Methods in Chemical Process Safety (Vol.

1, pp. 1-36). Elsevier.

Knapp, G. and Lincoln, J., 2016. International Commercial Fishing Management Regime

Safety Study: Review of International Case Studies.

Leveson, N.G., 2011. The use of safety cases in certification and regulation.

Macalister, T., 2013. Piper Alpha disaster: how 167 oil rig workers died. [online] the

Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/jul/04/piper-alpha-

disaster-167-oil-rig [Accessed 30 May 2018].

References:

bbc.com, 2013. Piper Alpha: In their own words. [online] BBC News. Available at:

http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-22840445 [Accessed 30 May 2018].

Briassoulis, H. and Papazoglou, I., 1993, October. Determining the uses of land in the

vicinity of major hazard facilities: an optimization algorithm. In Proceedings of the IFIP

TC5/WG5. 11 Working Conference on Computer Support for Environmental Impact

Assessment (pp. 177-186). North-Holland Publishing Co..

Christou, M. and Konstantinidou, M., 2012. Safety of offshore oil and gas operations:

Lessons from past accident analysis. Joint Research Centre, European Commission,

Luxembourg.

Ericson, C.A., 2015. Hazard analysis techniques for system safety. John Wiley & Sons.

Hopkins, A., 2015. The cost–benefit hurdle for safety case regulation. Safety Science, 77,

pp.95-101.

Khan, F. and Hashemi, S.J., 2017. Introduction. In Methods in Chemical Process Safety (Vol.

1, pp. 1-36). Elsevier.

Knapp, G. and Lincoln, J., 2016. International Commercial Fishing Management Regime

Safety Study: Review of International Case Studies.

Leveson, N.G., 2011. The use of safety cases in certification and regulation.

Macalister, T., 2013. Piper Alpha disaster: how 167 oil rig workers died. [online] the

Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/jul/04/piper-alpha-

disaster-167-oil-rig [Accessed 30 May 2018].

11Safety case regime

Mearns, K., Whitaker, S.M. and Flin, R., 2003. Safety climate, safety management practice

and safety performance in offshore environments. Safety science, 41(8), pp.641-680.

mom.gov.sg, 2018. Safety Case Regime for MHIs. [online] Ministry of Manpower Singapore.

Available at: http://www.mom.gov.sg/workplace-safety-and-health/major-hazard-

installations/safety-case-regime [Accessed 30 May 2018].

Nicol, J., 2001. Have Australias Major Hazard Facilities Learnt from the Longford Disaster?:

An Evaluation of the Impact of the 1998 Esso Longford Explosion on Major Hazard

Facilities in 2001. Have Australias Major Hazard Facilities Learnt from the Longford

Disaster?: An Evaluation of the Impact of the 1998 Esso Longford Explosion on Major

Hazard Facilities in 2001, p.53.

Nopsema.gov.au., 2018. What is a safety case » NOPSEMA. [online] Nopsema.gov.au.

Available at: https://www.nopsema.gov.au/safety/safety-case/what-is-a-safety-case/

[Accessed 30 May 2018].

safeworkaustralia.gov.au, 2018. Major hazard facilities. [online] Safe Work Australia.

Available at: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/mhf [Accessed 30 May 2018].

Sefton, A.D., 1994, January. The Development of the UK Safety Case Regime: A Shift in

Responsibility from Government to Industry. In Offshore Technology Conference. Offshore

Technology Conference.

sma.nasa.gov, 2013. The Case for Safety The North Sea Piper Alpha Disaster. [online]

Available at: https://sma.nasa.gov/docs/default-source/safety-messages/safetymessage-2013-

05-06-piperalpha.pdf?sfvrsn=3daf1ef8_6 [Accessed 30 May 2018].

Mearns, K., Whitaker, S.M. and Flin, R., 2003. Safety climate, safety management practice

and safety performance in offshore environments. Safety science, 41(8), pp.641-680.

mom.gov.sg, 2018. Safety Case Regime for MHIs. [online] Ministry of Manpower Singapore.

Available at: http://www.mom.gov.sg/workplace-safety-and-health/major-hazard-

installations/safety-case-regime [Accessed 30 May 2018].

Nicol, J., 2001. Have Australias Major Hazard Facilities Learnt from the Longford Disaster?:

An Evaluation of the Impact of the 1998 Esso Longford Explosion on Major Hazard

Facilities in 2001. Have Australias Major Hazard Facilities Learnt from the Longford

Disaster?: An Evaluation of the Impact of the 1998 Esso Longford Explosion on Major

Hazard Facilities in 2001, p.53.

Nopsema.gov.au., 2018. What is a safety case » NOPSEMA. [online] Nopsema.gov.au.

Available at: https://www.nopsema.gov.au/safety/safety-case/what-is-a-safety-case/

[Accessed 30 May 2018].

safeworkaustralia.gov.au, 2018. Major hazard facilities. [online] Safe Work Australia.

Available at: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/mhf [Accessed 30 May 2018].

Sefton, A.D., 1994, January. The Development of the UK Safety Case Regime: A Shift in

Responsibility from Government to Industry. In Offshore Technology Conference. Offshore

Technology Conference.

sma.nasa.gov, 2013. The Case for Safety The North Sea Piper Alpha Disaster. [online]

Available at: https://sma.nasa.gov/docs/default-source/safety-messages/safetymessage-2013-

05-06-piperalpha.pdf?sfvrsn=3daf1ef8_6 [Accessed 30 May 2018].

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 14

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.