Environmental Engineering Project: SBR Simulation for Nutrient Removal

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/25

|29

|4614

|22

Project

AI Summary

This project simulates the nitrogen and phosphorus removal process in a granular sequencing batch reactor (SBR) using Aquasim software. The research focuses on mathematically modeling the simultaneous heterotrophic and autotrophic growth within the SBR, considering biofilm, mixed, and settler compartments linked through advective and bifurcation links. The model utilizes the ASM2d model and floc models for biological processes, incorporating stoichiometric coefficients and laboratory data for validation. Key aspects include understanding the kinetics of nitrification and denitrification, the role of aerobic granules, and the impact of factors such as temperature, DO levels, and pH on the process. The project aims to provide insights into reactor performance, the fractions of active biomass, and the efficient removal of nutrients from wastewater, addressing the challenges of stringent discharge standards and eutrophication. The model simulates various parameters, including bacteria profiles, nitrite and nitrate concentrations, and the variation of mixed compartment volume with time. The results highlight the importance of understanding the interactions between autotrophs and heterotrophs for optimizing nutrient removal in wastewater treatment systems.

1

Nitrogen and phosphorus removal process in a granular SBR

Student’s Name

Institutional affiliation

Date

Nitrogen and phosphorus removal process in a granular SBR

Student’s Name

Institutional affiliation

Date

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

Abstract

The objective of this research was to investigate the performance of a granule SBR used in

the removal of nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater. The removal process of these

elements was mathematically modeled taking into account the simultaneous heterotrophic

and autotrophic growth in the SBR. Aquasim software was then used to simulate the system

using three compartments including the biofilm, mixed and settler compartments. These were

linked using advective links with a bifurcation link circulating Qwaste between the mixed

and biofilm compartments. The results obtained indicate that this model is sufficient for the

validation of experimental data.

Keywords

Autotrophic, heterotrophic, aerobic, anaerobic

Introduction

Nitrogen and phosphorous are crucial constituents of organic materials. The cycle of

these materials in the natural surroundings is one of the key material cycles in the biosphere.

According to Zhu et al., (2018), emissions and water pollution from nitrogen and

phosphorous-based compounds has increased with the rapid growth of manufacturing and

processing industries as well as agricultural activities. If wastewater containing high

ammonia content enters into water bodies, eutrophication results. Eutrophication can cause

algal blooms, which in turn lead to plant and fish mortality as a result of oxygen and light

deficiency (Sengupta, Nawaz, & Beaudry, 2015). Consequently, the treatment of wastewater

is necessary to reduce nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations before discharging into water

bodies. With the increasing stringent discharge standards, the sequencing batch reactor (SBR)

treatment technology offers flexible process control and design to achieve these standards.

SBR cycle phases depend on time rather than space which provides a high degree of

Abstract

The objective of this research was to investigate the performance of a granule SBR used in

the removal of nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater. The removal process of these

elements was mathematically modeled taking into account the simultaneous heterotrophic

and autotrophic growth in the SBR. Aquasim software was then used to simulate the system

using three compartments including the biofilm, mixed and settler compartments. These were

linked using advective links with a bifurcation link circulating Qwaste between the mixed

and biofilm compartments. The results obtained indicate that this model is sufficient for the

validation of experimental data.

Keywords

Autotrophic, heterotrophic, aerobic, anaerobic

Introduction

Nitrogen and phosphorous are crucial constituents of organic materials. The cycle of

these materials in the natural surroundings is one of the key material cycles in the biosphere.

According to Zhu et al., (2018), emissions and water pollution from nitrogen and

phosphorous-based compounds has increased with the rapid growth of manufacturing and

processing industries as well as agricultural activities. If wastewater containing high

ammonia content enters into water bodies, eutrophication results. Eutrophication can cause

algal blooms, which in turn lead to plant and fish mortality as a result of oxygen and light

deficiency (Sengupta, Nawaz, & Beaudry, 2015). Consequently, the treatment of wastewater

is necessary to reduce nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations before discharging into water

bodies. With the increasing stringent discharge standards, the sequencing batch reactor (SBR)

treatment technology offers flexible process control and design to achieve these standards.

SBR cycle phases depend on time rather than space which provides a high degree of

3

flexibility for the removal of nutrients through mixing regimes and the alteration of aeration

to create an alternating anoxic and aerobic environment in the 'react' phase (Dutta & Sarkar,

2015).

Two steps are involved in the removal of biological nutrients. These include

nitrification and denitrification. The first step involves the conversion of the organic nitrogen

into ammonia-nitrogen. In complete nitrification, chemoautotrophic bacteria oxidize

ammonia-nitrogen to nitrate-nitrogen (Samer, 2015). The process comprises two steps with

the conversion of ammonia to nitrite in the first step and conversion of nitrite to nitrate in the

second step. This process is catalyzed by two types of autotrophic bacteria namely ammonia

oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and nitrite oxidizing bacteria (NOB) respectively. An aerobic

environment is required for nitrification and is achieved by aeration in the SBR tank. In the

second step (denitrification), the active bacteria are heterotrophic which require an anaerobic

environment. In nitrification kinetics, factors such as temperature, DO level, pH and solids

retention time (SRT) are very important. The optimum temperature ranges from 25 to 35℃.

If the pH lies beyond 7.5 to 9.8, the rate of nitrification drops to about half of the optimum

(Li et al., 2010). Nitrification lowers the pH (increases acidity). Generally, aerobic

granulation makes it possible to treat the same wastewater volume using about 3 to 5 times

more biomass (Dutta & Sarkar 2015).

Review

The settling properties in an SBR treatment plant have a significant dependency on

the type of sludge (Li et al., 2010). The higher density of granules and larger diameter

compared to flocs allows a granular bioreactor to maintain a high concentration of biomass

flexibility for the removal of nutrients through mixing regimes and the alteration of aeration

to create an alternating anoxic and aerobic environment in the 'react' phase (Dutta & Sarkar,

2015).

Two steps are involved in the removal of biological nutrients. These include

nitrification and denitrification. The first step involves the conversion of the organic nitrogen

into ammonia-nitrogen. In complete nitrification, chemoautotrophic bacteria oxidize

ammonia-nitrogen to nitrate-nitrogen (Samer, 2015). The process comprises two steps with

the conversion of ammonia to nitrite in the first step and conversion of nitrite to nitrate in the

second step. This process is catalyzed by two types of autotrophic bacteria namely ammonia

oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and nitrite oxidizing bacteria (NOB) respectively. An aerobic

environment is required for nitrification and is achieved by aeration in the SBR tank. In the

second step (denitrification), the active bacteria are heterotrophic which require an anaerobic

environment. In nitrification kinetics, factors such as temperature, DO level, pH and solids

retention time (SRT) are very important. The optimum temperature ranges from 25 to 35℃.

If the pH lies beyond 7.5 to 9.8, the rate of nitrification drops to about half of the optimum

(Li et al., 2010). Nitrification lowers the pH (increases acidity). Generally, aerobic

granulation makes it possible to treat the same wastewater volume using about 3 to 5 times

more biomass (Dutta & Sarkar 2015).

Review

The settling properties in an SBR treatment plant have a significant dependency on

the type of sludge (Li et al., 2010). The higher density of granules and larger diameter

compared to flocs allows a granular bioreactor to maintain a high concentration of biomass

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

yielding excellent settling properties (Dutta & Sarkar, 2015). There has been extensive

research on aerobic granules, motivated by the advantages offered by granules compared to

flocs. In addition to their high biomass retention, they are more compact in structure.

According to (Ni, 2012), aerobic granules could be used in the removal of organic matters

including nitrogen and phosphorous as well as the decomposition of toxic wastewaters.

Aerobic granules are made up of two major microbial groups namely autotrophic and

heterotrophic bacteria. According to Ni (2012), the two types of bacteria interact and coexist

in aerobic granules. Both bacteria types play a critical role in the removal of nitrogen and

phosphorous. Yang, Li, Yang, & Luo (2011) investigated the simultaneous removal of

nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater. They established that it is possible to convert

conventional SBRs that use flocculating sludge into granular SBRs by the reduction of the

settling time. Studies have reported the formation of granules under aerobic and alternating

aerobic/anaerobic environments in SBRs utilizing flocculating sludge.

According to Ni, Yu, & Sun (2008), the organic matter present in wastewater presents

dissolved oxygen (DO) and space competition between the heterotrophs and autotrophs in the

granules. The limited oxygen diffusion in granules of large size with a mixed population

creates anoxic and aerobic conditions that allow the sequential use of acceptors including

oxygen and nitrate. The optimal removal of nutrients from wastewater in granule based SBRs

requires a deep understanding of the activities of autotrophs and heterotrophs such as growth

in aerobic granules. The rate of growth of heterotrophs is considerably higher than that of

autotrophs. The efficiency of nitrification may be reduced by the inhibition of the autotrophs

due to the interspecies competition (Duan, Fu, Zhu, Xu, & Li, 2011). Keluskar, Nerurkar, &

Desai (2013) studied the competition between heterotrophs and autotrophs for oxygen and

ammonia (substrates) and space in biofilms. Understanding this relationship is of major

practical importance. A study by Bassin, Kleerebezem, Rosado, Van Loosdrecht, & Dezotti

yielding excellent settling properties (Dutta & Sarkar, 2015). There has been extensive

research on aerobic granules, motivated by the advantages offered by granules compared to

flocs. In addition to their high biomass retention, they are more compact in structure.

According to (Ni, 2012), aerobic granules could be used in the removal of organic matters

including nitrogen and phosphorous as well as the decomposition of toxic wastewaters.

Aerobic granules are made up of two major microbial groups namely autotrophic and

heterotrophic bacteria. According to Ni (2012), the two types of bacteria interact and coexist

in aerobic granules. Both bacteria types play a critical role in the removal of nitrogen and

phosphorous. Yang, Li, Yang, & Luo (2011) investigated the simultaneous removal of

nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater. They established that it is possible to convert

conventional SBRs that use flocculating sludge into granular SBRs by the reduction of the

settling time. Studies have reported the formation of granules under aerobic and alternating

aerobic/anaerobic environments in SBRs utilizing flocculating sludge.

According to Ni, Yu, & Sun (2008), the organic matter present in wastewater presents

dissolved oxygen (DO) and space competition between the heterotrophs and autotrophs in the

granules. The limited oxygen diffusion in granules of large size with a mixed population

creates anoxic and aerobic conditions that allow the sequential use of acceptors including

oxygen and nitrate. The optimal removal of nutrients from wastewater in granule based SBRs

requires a deep understanding of the activities of autotrophs and heterotrophs such as growth

in aerobic granules. The rate of growth of heterotrophs is considerably higher than that of

autotrophs. The efficiency of nitrification may be reduced by the inhibition of the autotrophs

due to the interspecies competition (Duan, Fu, Zhu, Xu, & Li, 2011). Keluskar, Nerurkar, &

Desai (2013) studied the competition between heterotrophs and autotrophs for oxygen and

ammonia (substrates) and space in biofilms. Understanding this relationship is of major

practical importance. A study by Bassin, Kleerebezem, Rosado, Van Loosdrecht, & Dezotti

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

(2012) showed that competition in a biofilm produced a stratified biofilm structure with the

fast-growing heterotrophs on the outer layers where the rate of detachment and substrate

concentration were high and the slow-growing nitrifying bacteria located deeper inside the

biofilm. According to, research on heterotrophic and autotrophic growth in SBRs based on

aerobic granules is limited. He, Zhang, Zhang, Zou, & Wang (2017) studied the connection

between reactor operation performance and population dynamics. Their results showed that a

rise in hydraulic retention time (HRT) produced a decrease in the nitrification activity. They

used two biofilm reactors operating at HRTs of 0.8 and 5 hours from pure nitrification and

the combination of nitrification with organic carbon removal.

Method

Mathematical formulation and software simulations are important tools in the modeling of

physical systems. In this study, a mathematical model was developed to describe the process

of the removal of nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater. Laboratory data were also

collected for use as a basis for the validation of the developed model.

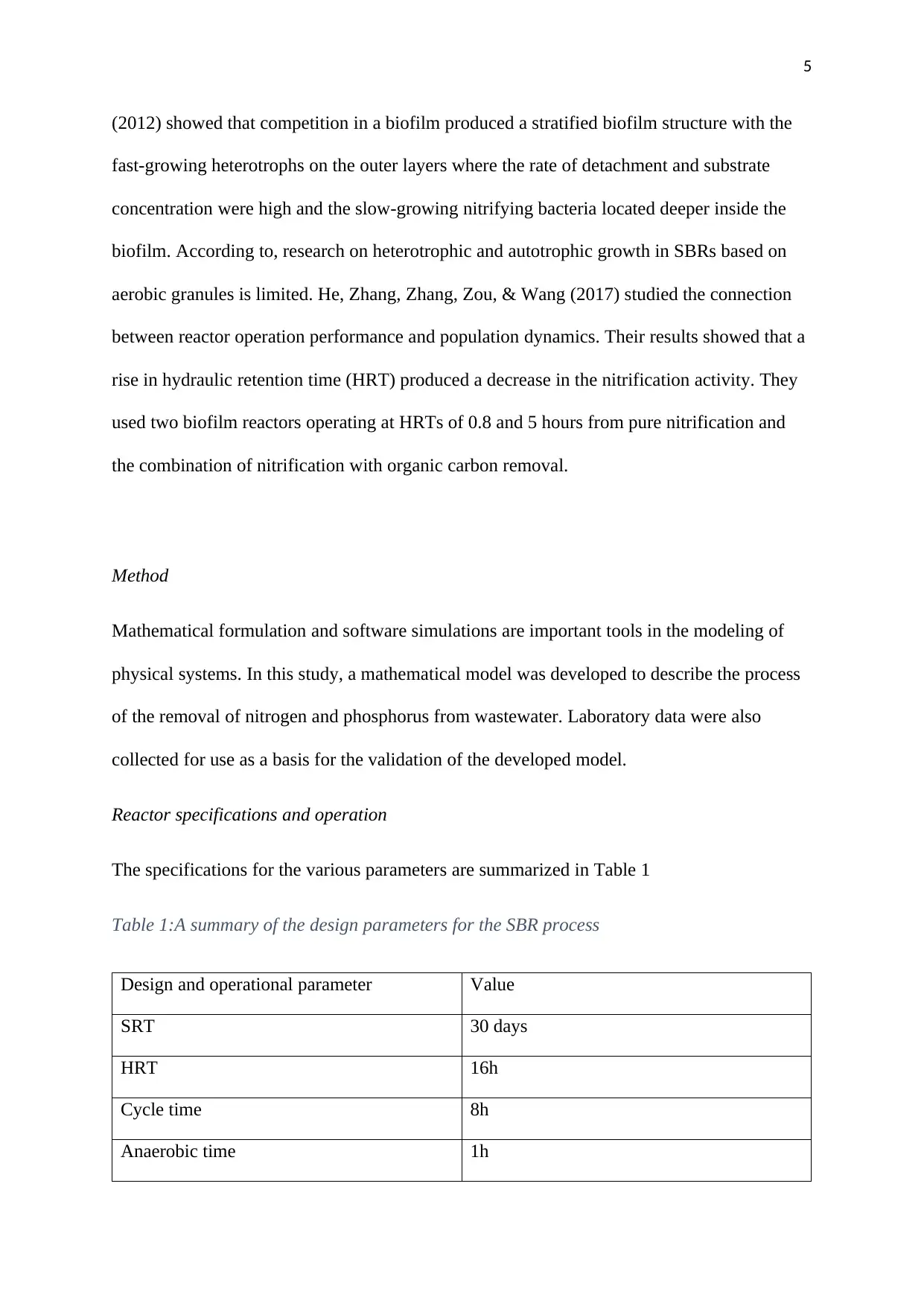

Reactor specifications and operation

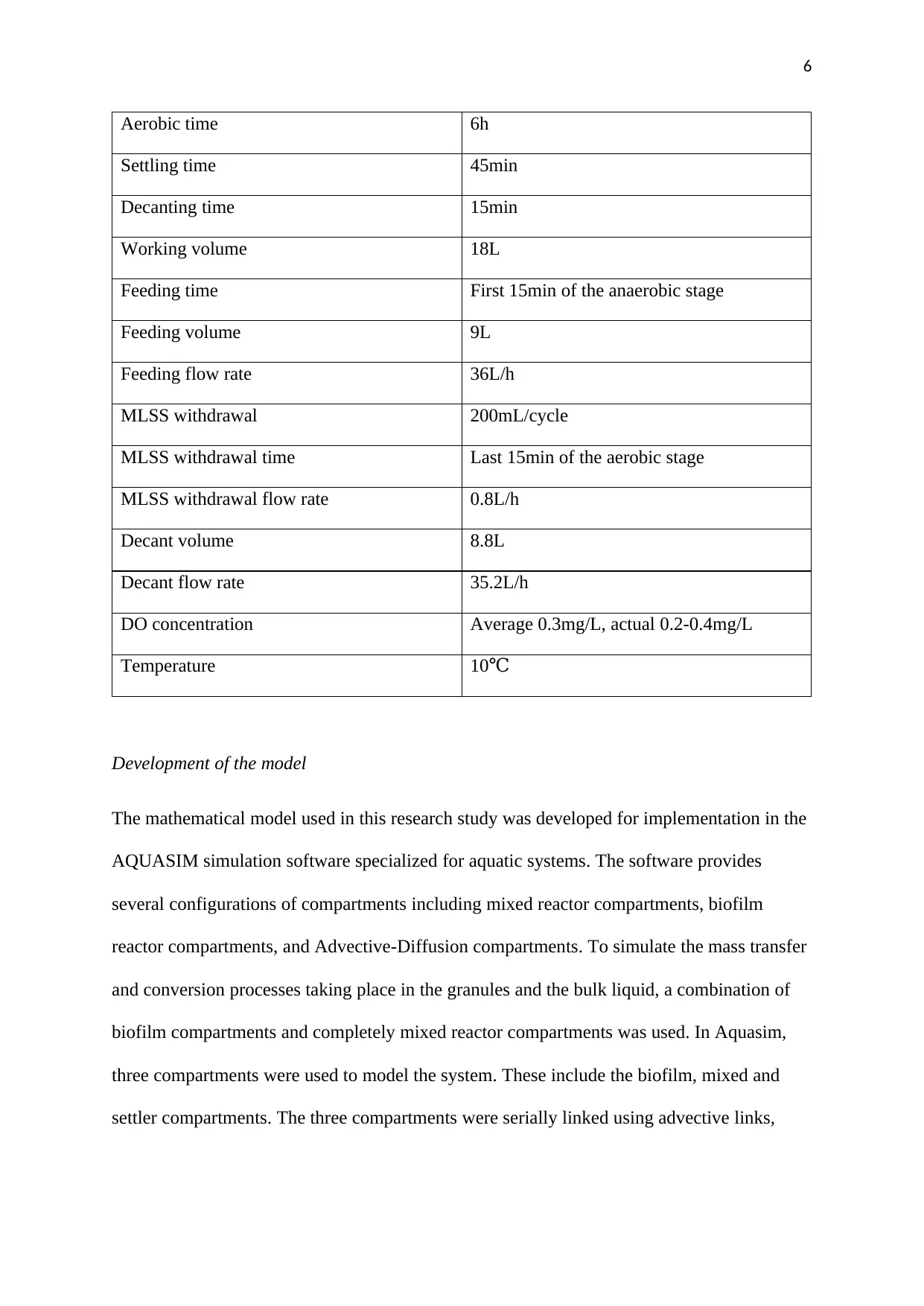

The specifications for the various parameters are summarized in Table 1

Table 1:A summary of the design parameters for the SBR process

Design and operational parameter Value

SRT 30 days

HRT 16h

Cycle time 8h

Anaerobic time 1h

(2012) showed that competition in a biofilm produced a stratified biofilm structure with the

fast-growing heterotrophs on the outer layers where the rate of detachment and substrate

concentration were high and the slow-growing nitrifying bacteria located deeper inside the

biofilm. According to, research on heterotrophic and autotrophic growth in SBRs based on

aerobic granules is limited. He, Zhang, Zhang, Zou, & Wang (2017) studied the connection

between reactor operation performance and population dynamics. Their results showed that a

rise in hydraulic retention time (HRT) produced a decrease in the nitrification activity. They

used two biofilm reactors operating at HRTs of 0.8 and 5 hours from pure nitrification and

the combination of nitrification with organic carbon removal.

Method

Mathematical formulation and software simulations are important tools in the modeling of

physical systems. In this study, a mathematical model was developed to describe the process

of the removal of nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater. Laboratory data were also

collected for use as a basis for the validation of the developed model.

Reactor specifications and operation

The specifications for the various parameters are summarized in Table 1

Table 1:A summary of the design parameters for the SBR process

Design and operational parameter Value

SRT 30 days

HRT 16h

Cycle time 8h

Anaerobic time 1h

6

Aerobic time 6h

Settling time 45min

Decanting time 15min

Working volume 18L

Feeding time First 15min of the anaerobic stage

Feeding volume 9L

Feeding flow rate 36L/h

MLSS withdrawal 200mL/cycle

MLSS withdrawal time Last 15min of the aerobic stage

MLSS withdrawal flow rate 0.8L/h

Decant volume 8.8L

Decant flow rate 35.2L/h

DO concentration Average 0.3mg/L, actual 0.2-0.4mg/L

Temperature 10℃

Development of the model

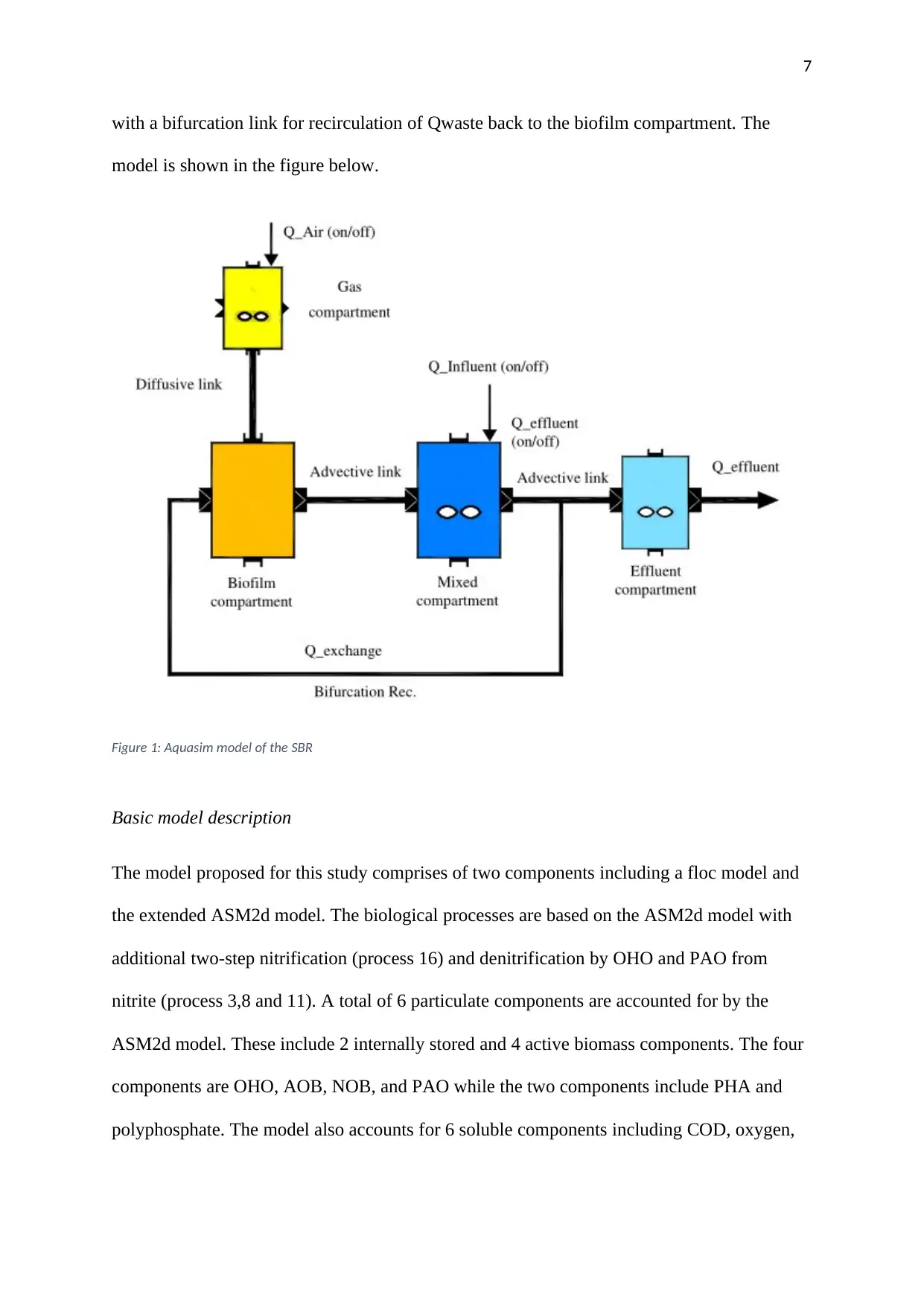

The mathematical model used in this research study was developed for implementation in the

AQUASIM simulation software specialized for aquatic systems. The software provides

several configurations of compartments including mixed reactor compartments, biofilm

reactor compartments, and Advective-Diffusion compartments. To simulate the mass transfer

and conversion processes taking place in the granules and the bulk liquid, a combination of

biofilm compartments and completely mixed reactor compartments was used. In Aquasim,

three compartments were used to model the system. These include the biofilm, mixed and

settler compartments. The three compartments were serially linked using advective links,

Aerobic time 6h

Settling time 45min

Decanting time 15min

Working volume 18L

Feeding time First 15min of the anaerobic stage

Feeding volume 9L

Feeding flow rate 36L/h

MLSS withdrawal 200mL/cycle

MLSS withdrawal time Last 15min of the aerobic stage

MLSS withdrawal flow rate 0.8L/h

Decant volume 8.8L

Decant flow rate 35.2L/h

DO concentration Average 0.3mg/L, actual 0.2-0.4mg/L

Temperature 10℃

Development of the model

The mathematical model used in this research study was developed for implementation in the

AQUASIM simulation software specialized for aquatic systems. The software provides

several configurations of compartments including mixed reactor compartments, biofilm

reactor compartments, and Advective-Diffusion compartments. To simulate the mass transfer

and conversion processes taking place in the granules and the bulk liquid, a combination of

biofilm compartments and completely mixed reactor compartments was used. In Aquasim,

three compartments were used to model the system. These include the biofilm, mixed and

settler compartments. The three compartments were serially linked using advective links,

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

with a bifurcation link for recirculation of Qwaste back to the biofilm compartment. The

model is shown in the figure below.

Figure 1: Aquasim model of the SBR

Basic model description

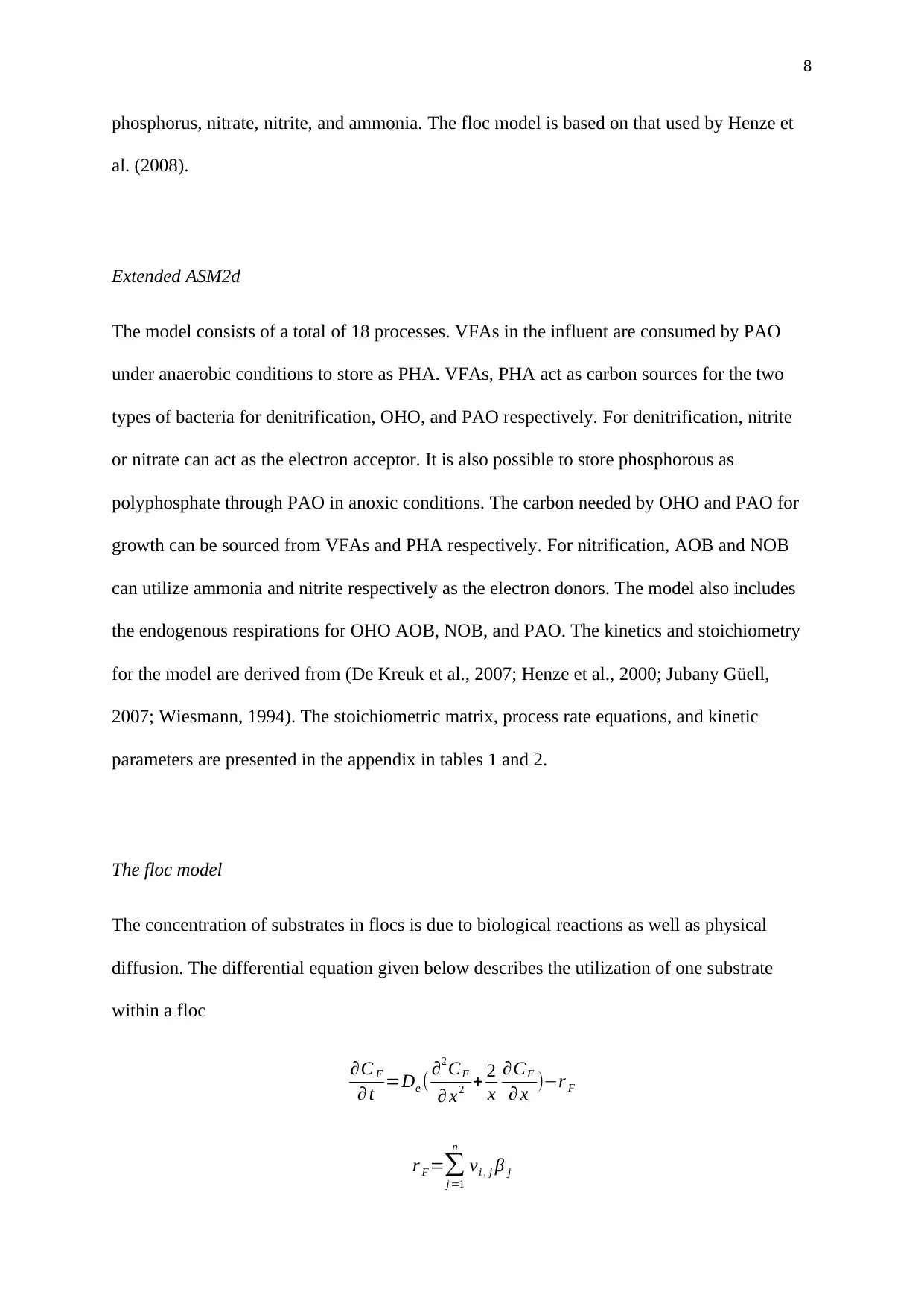

The model proposed for this study comprises of two components including a floc model and

the extended ASM2d model. The biological processes are based on the ASM2d model with

additional two-step nitrification (process 16) and denitrification by OHO and PAO from

nitrite (process 3,8 and 11). A total of 6 particulate components are accounted for by the

ASM2d model. These include 2 internally stored and 4 active biomass components. The four

components are OHO, AOB, NOB, and PAO while the two components include PHA and

polyphosphate. The model also accounts for 6 soluble components including COD, oxygen,

with a bifurcation link for recirculation of Qwaste back to the biofilm compartment. The

model is shown in the figure below.

Figure 1: Aquasim model of the SBR

Basic model description

The model proposed for this study comprises of two components including a floc model and

the extended ASM2d model. The biological processes are based on the ASM2d model with

additional two-step nitrification (process 16) and denitrification by OHO and PAO from

nitrite (process 3,8 and 11). A total of 6 particulate components are accounted for by the

ASM2d model. These include 2 internally stored and 4 active biomass components. The four

components are OHO, AOB, NOB, and PAO while the two components include PHA and

polyphosphate. The model also accounts for 6 soluble components including COD, oxygen,

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

phosphorus, nitrate, nitrite, and ammonia. The floc model is based on that used by Henze et

al. (2008).

Extended ASM2d

The model consists of a total of 18 processes. VFAs in the influent are consumed by PAO

under anaerobic conditions to store as PHA. VFAs, PHA act as carbon sources for the two

types of bacteria for denitrification, OHO, and PAO respectively. For denitrification, nitrite

or nitrate can act as the electron acceptor. It is also possible to store phosphorous as

polyphosphate through PAO in anoxic conditions. The carbon needed by OHO and PAO for

growth can be sourced from VFAs and PHA respectively. For nitrification, AOB and NOB

can utilize ammonia and nitrite respectively as the electron donors. The model also includes

the endogenous respirations for OHO AOB, NOB, and PAO. The kinetics and stoichiometry

for the model are derived from (De Kreuk et al., 2007; Henze et al., 2000; Jubany Güell,

2007; Wiesmann, 1994). The stoichiometric matrix, process rate equations, and kinetic

parameters are presented in the appendix in tables 1 and 2.

The floc model

The concentration of substrates in flocs is due to biological reactions as well as physical

diffusion. The differential equation given below describes the utilization of one substrate

within a floc

∂C F

∂ t =De ( ∂2 CF

∂ x2 + 2

x

∂CF

∂ x )−r F

r F =∑

j =1

n

vi , j β j

phosphorus, nitrate, nitrite, and ammonia. The floc model is based on that used by Henze et

al. (2008).

Extended ASM2d

The model consists of a total of 18 processes. VFAs in the influent are consumed by PAO

under anaerobic conditions to store as PHA. VFAs, PHA act as carbon sources for the two

types of bacteria for denitrification, OHO, and PAO respectively. For denitrification, nitrite

or nitrate can act as the electron acceptor. It is also possible to store phosphorous as

polyphosphate through PAO in anoxic conditions. The carbon needed by OHO and PAO for

growth can be sourced from VFAs and PHA respectively. For nitrification, AOB and NOB

can utilize ammonia and nitrite respectively as the electron donors. The model also includes

the endogenous respirations for OHO AOB, NOB, and PAO. The kinetics and stoichiometry

for the model are derived from (De Kreuk et al., 2007; Henze et al., 2000; Jubany Güell,

2007; Wiesmann, 1994). The stoichiometric matrix, process rate equations, and kinetic

parameters are presented in the appendix in tables 1 and 2.

The floc model

The concentration of substrates in flocs is due to biological reactions as well as physical

diffusion. The differential equation given below describes the utilization of one substrate

within a floc

∂C F

∂ t =De ( ∂2 CF

∂ x2 + 2

x

∂CF

∂ x )−r F

r F =∑

j =1

n

vi , j β j

9

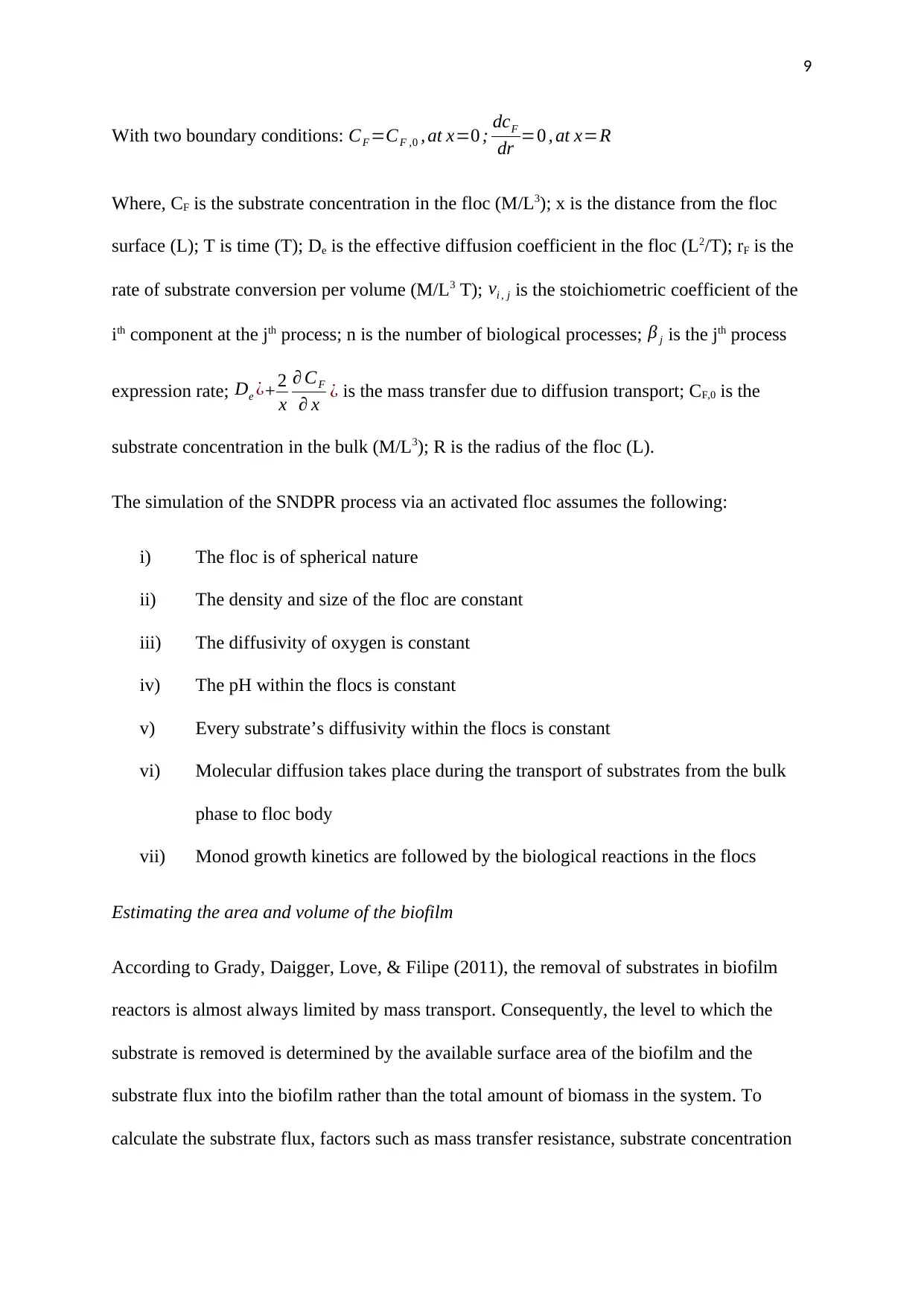

With two boundary conditions: CF =CF ,0 , at x=0 ; dcF

dr =0 , at x=R

Where, CF is the substrate concentration in the floc (M/L3); x is the distance from the floc

surface (L); T is time (T); De is the effective diffusion coefficient in the floc (L2/T); rF is the

rate of substrate conversion per volume (M/L3 T); vi , j is the stoichiometric coefficient of the

ith component at the jth process; n is the number of biological processes; β j is the jth process

expression rate; De ¿+ 2

x

∂ CF

∂ x ¿ is the mass transfer due to diffusion transport; CF,0 is the

substrate concentration in the bulk (M/L3); R is the radius of the floc (L).

The simulation of the SNDPR process via an activated floc assumes the following:

i) The floc is of spherical nature

ii) The density and size of the floc are constant

iii) The diffusivity of oxygen is constant

iv) The pH within the flocs is constant

v) Every substrate’s diffusivity within the flocs is constant

vi) Molecular diffusion takes place during the transport of substrates from the bulk

phase to floc body

vii) Monod growth kinetics are followed by the biological reactions in the flocs

Estimating the area and volume of the biofilm

According to Grady, Daigger, Love, & Filipe (2011), the removal of substrates in biofilm

reactors is almost always limited by mass transport. Consequently, the level to which the

substrate is removed is determined by the available surface area of the biofilm and the

substrate flux into the biofilm rather than the total amount of biomass in the system. To

calculate the substrate flux, factors such as mass transfer resistance, substrate concentration

With two boundary conditions: CF =CF ,0 , at x=0 ; dcF

dr =0 , at x=R

Where, CF is the substrate concentration in the floc (M/L3); x is the distance from the floc

surface (L); T is time (T); De is the effective diffusion coefficient in the floc (L2/T); rF is the

rate of substrate conversion per volume (M/L3 T); vi , j is the stoichiometric coefficient of the

ith component at the jth process; n is the number of biological processes; β j is the jth process

expression rate; De ¿+ 2

x

∂ CF

∂ x ¿ is the mass transfer due to diffusion transport; CF,0 is the

substrate concentration in the bulk (M/L3); R is the radius of the floc (L).

The simulation of the SNDPR process via an activated floc assumes the following:

i) The floc is of spherical nature

ii) The density and size of the floc are constant

iii) The diffusivity of oxygen is constant

iv) The pH within the flocs is constant

v) Every substrate’s diffusivity within the flocs is constant

vi) Molecular diffusion takes place during the transport of substrates from the bulk

phase to floc body

vii) Monod growth kinetics are followed by the biological reactions in the flocs

Estimating the area and volume of the biofilm

According to Grady, Daigger, Love, & Filipe (2011), the removal of substrates in biofilm

reactors is almost always limited by mass transport. Consequently, the level to which the

substrate is removed is determined by the available surface area of the biofilm and the

substrate flux into the biofilm rather than the total amount of biomass in the system. To

calculate the substrate flux, factors such as mass transfer resistance, substrate concentration

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

of the effluent, mass transport and the reactions in the biofilm. The surface area of the biofilm

can be estimated from the equation given below,

AF =Q(C¿−CB)

J LF

Where CB is the concentration of the soluble substrates in the bulk water, C¿ is the

concentration of the soluble substrate in the influent and J LF is the substrate flux at the

surface of the biofilm. This equation assumes that the removal of substrates in the bulk phase

is negligible. The minimum volume of the reactorV R is then given by.

V R= A F

aF

Where aFis the specific area of the biofilm.

Results and discussion

Mixed model

of the effluent, mass transport and the reactions in the biofilm. The surface area of the biofilm

can be estimated from the equation given below,

AF =Q(C¿−CB)

J LF

Where CB is the concentration of the soluble substrates in the bulk water, C¿ is the

concentration of the soluble substrate in the influent and J LF is the substrate flux at the

surface of the biofilm. This equation assumes that the removal of substrates in the bulk phase

is negligible. The minimum volume of the reactorV R is then given by.

V R= A F

aF

Where aFis the specific area of the biofilm.

Results and discussion

Mixed model

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

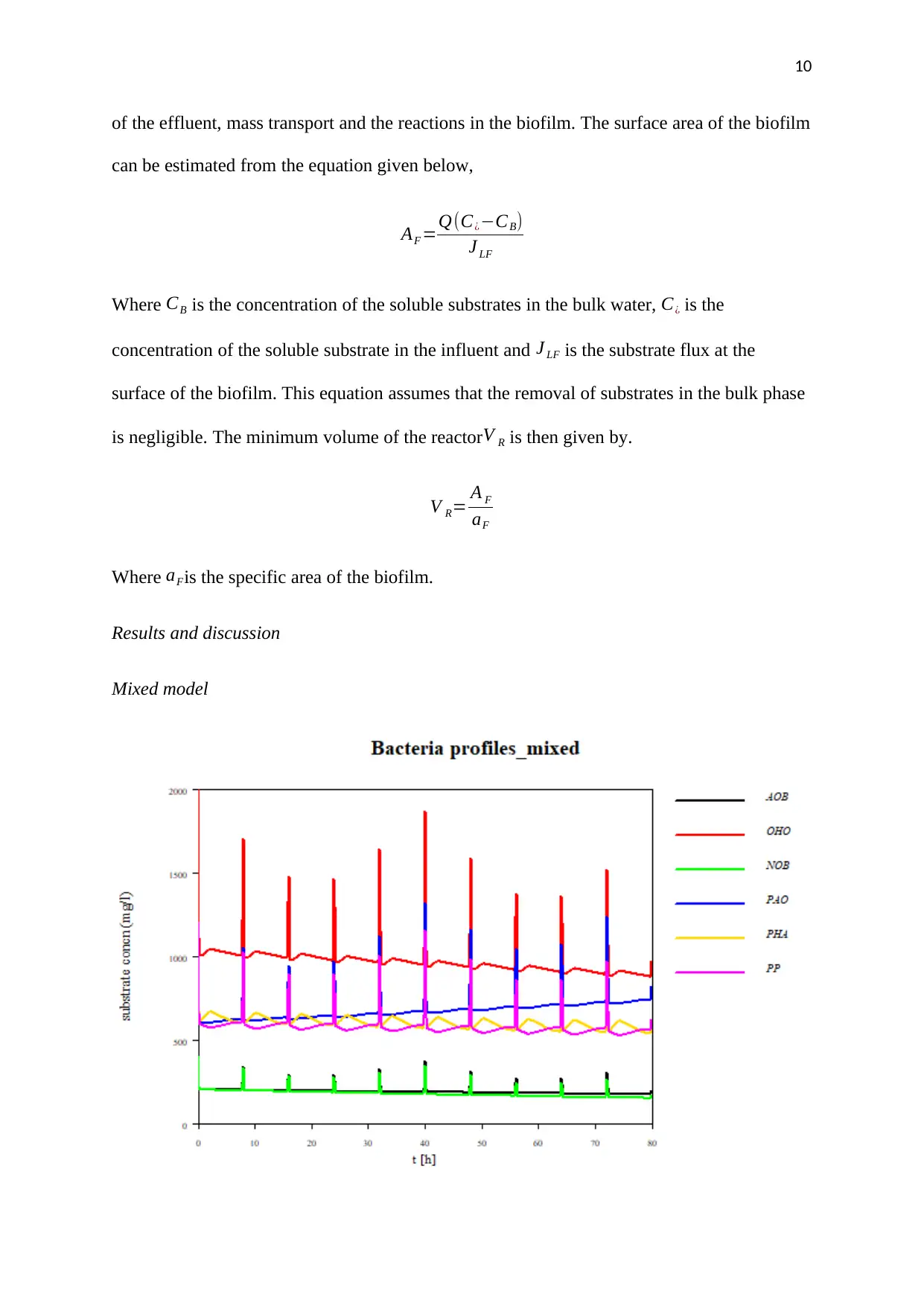

Figure 2: Bacteria profiles in the mixed compartment

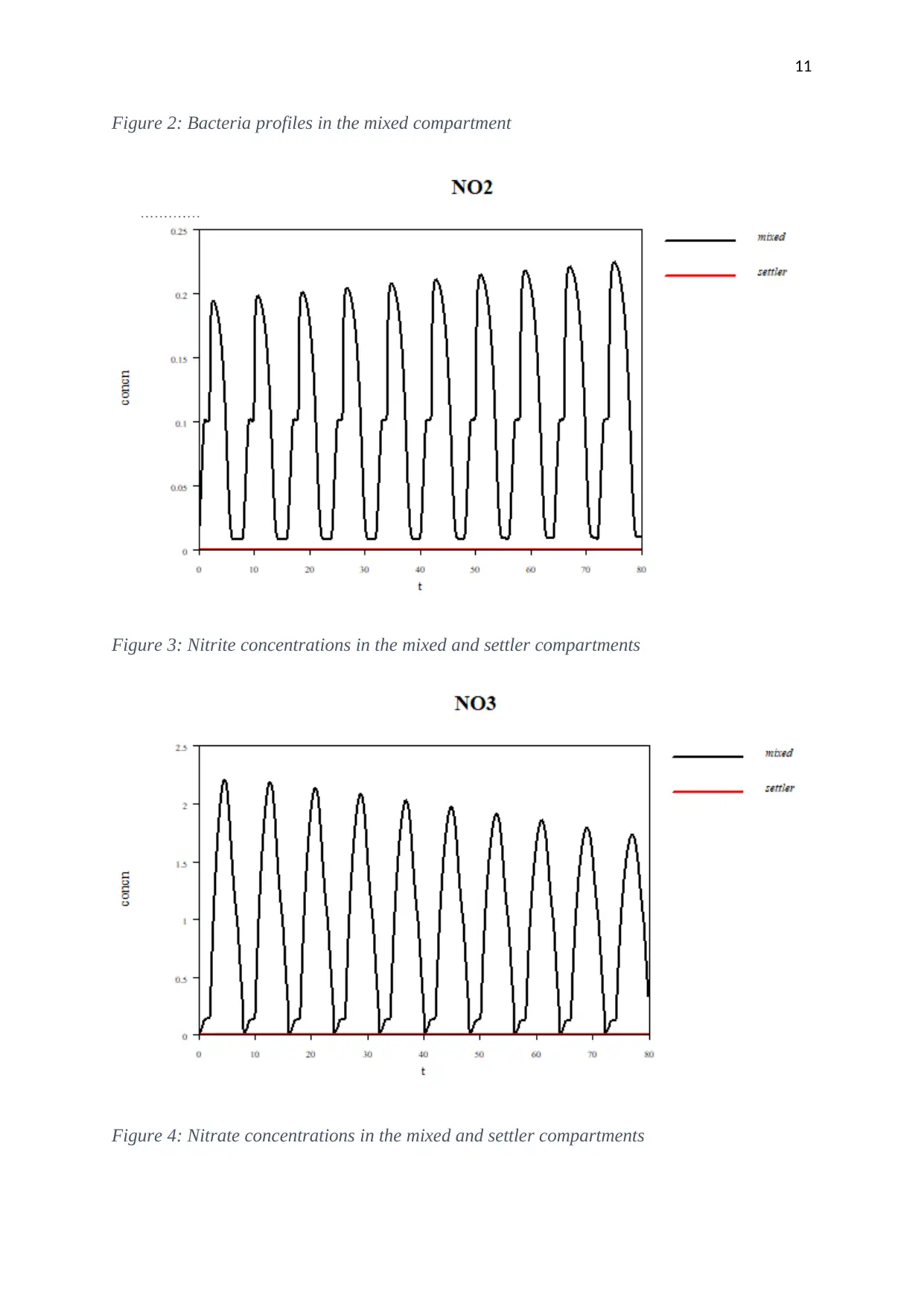

Figure 3: Nitrite concentrations in the mixed and settler compartments

Figure 4: Nitrate concentrations in the mixed and settler compartments

Figure 2: Bacteria profiles in the mixed compartment

Figure 3: Nitrite concentrations in the mixed and settler compartments

Figure 4: Nitrate concentrations in the mixed and settler compartments

12

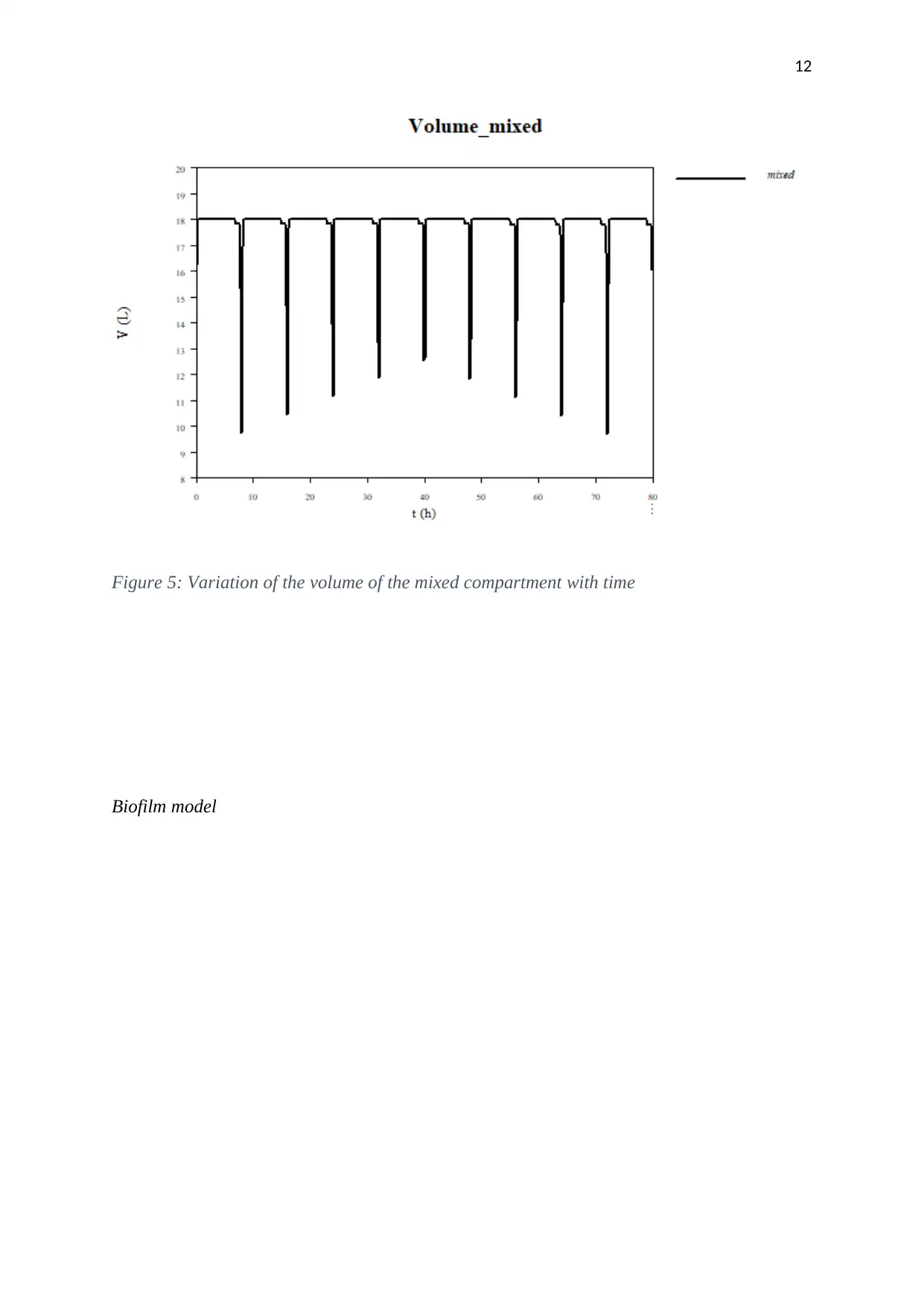

Figure 5: Variation of the volume of the mixed compartment with time

Biofilm model

Figure 5: Variation of the volume of the mixed compartment with time

Biofilm model

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 29

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.