A Scoping Review of Dementia and Alcohol Consumption (MD7069)

VerifiedAdded on 2022/04/26

|16

|4979

|42

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a scoping review that investigates the relationship between alcohol consumption and dementia, drawing on systematic reviews published between January 2000 and January 2019. The review examines the impact of alcohol on cognitive decline and the incidence of different types of dementia, including Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. The methodology involved a systematic search of databases such as PubMed, ScienceDirect, Elsevier, and Google Scholar, adhering to the PRISMA guidelines. The findings indicate that while light to moderate alcohol consumption may be associated with a lower risk of cognitive decline, heavy alcohol consumption is linked to structural changes in the brain, cognitive problems, and an increased risk of all forms of dementia. The review highlights the importance of reducing heavy alcohol consumption as a potential strategy for reducing the risk of dementia. The report also addresses the methodological limitations and challenges faced in assessing the relationship between alcohol use and the onset of dementia, including the exclusion of heavy drinkers in some studies and the focus on older populations.

MD7069 : ASSESSMENT AND CONSULTATION IN CLINICAL SETTINGS:

ASSESSMENT : SCOPING REVIEW

ASSESSMENT NUMBER : J87859

ASSESSMENT : SCOPING REVIEW

ASSESSMENT NUMBER : J87859

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

TITLE: A SCOPING REVIEW OF DEMENTIA AND ALCOHOL COMSUMPTION

Abstract: Liquor consumption has been distinguished as one of the risk factors for

dementia and brain cognitive delay. In some case, a few examples of drinking have

been related with beneficial impacts. Methods: A scoping review was undertaking to

understand the relationship between the alcohol consumptions and dementia based

on systematic review search from the articles which were published from January

2000 to January 2019 with the use of PubMed, ScienceDirect, Elsevier and google

scholar. Result: There were 8 systematic reviews found in total: 20 on the

connections between the amount of alcohol use as well as occurrence of cognitive

dysfunction, six on the connections between alcohol use measurements and

particular cognitive abilities, and two on triggered dementias. Even though causality

could never be founded, light to moderate consumption of alcohol in middle to late

adulthood was linked to a lower risk of cognitive decline and dementia. Heavy

alcohol consumption has been linked to structural changes in the brain, cognitive

problems, and an increased incidence of all forms of dementia. Conclusion: Thus, by

reducing the heavy consumption of alcohol is an effective way of reducing Dementia

which can be achieved and considered as one of the best strategies.

INTRODUCTION:

Dementia is a clinical syndrome that is distinguished by a progressive declining

cognitive ability as well as the opportunity to survive and remain independent.

Dementia impairs memory, thinking, behaviour, and daily tasks, and it is a major

cause of disability in the elderly. Dementia affects 5 to 7% of people over the age of

60 worldwide. Consequently, the global dementia population is expected to nearly

triple, from around 50 million by 2020 to 130 to 150 million in 2050, owing primarily to

the world's population epidemiological transition to older people, especially in low-

and middle countries (Albanese et al., 2017).

Alcohol is the most common and rapidly growing recreational drug in almost every

culture, and psychotropic drugs are often used in almost every culture. Only about

57% of the global population has not drunk alcohol in the previous year (Beydoun et

al., 2014). Alcohol consumption is widely acknowledged to have potential negative

effects and to make a significant contribution global burden of disease. More than

Abstract: Liquor consumption has been distinguished as one of the risk factors for

dementia and brain cognitive delay. In some case, a few examples of drinking have

been related with beneficial impacts. Methods: A scoping review was undertaking to

understand the relationship between the alcohol consumptions and dementia based

on systematic review search from the articles which were published from January

2000 to January 2019 with the use of PubMed, ScienceDirect, Elsevier and google

scholar. Result: There were 8 systematic reviews found in total: 20 on the

connections between the amount of alcohol use as well as occurrence of cognitive

dysfunction, six on the connections between alcohol use measurements and

particular cognitive abilities, and two on triggered dementias. Even though causality

could never be founded, light to moderate consumption of alcohol in middle to late

adulthood was linked to a lower risk of cognitive decline and dementia. Heavy

alcohol consumption has been linked to structural changes in the brain, cognitive

problems, and an increased incidence of all forms of dementia. Conclusion: Thus, by

reducing the heavy consumption of alcohol is an effective way of reducing Dementia

which can be achieved and considered as one of the best strategies.

INTRODUCTION:

Dementia is a clinical syndrome that is distinguished by a progressive declining

cognitive ability as well as the opportunity to survive and remain independent.

Dementia impairs memory, thinking, behaviour, and daily tasks, and it is a major

cause of disability in the elderly. Dementia affects 5 to 7% of people over the age of

60 worldwide. Consequently, the global dementia population is expected to nearly

triple, from around 50 million by 2020 to 130 to 150 million in 2050, owing primarily to

the world's population epidemiological transition to older people, especially in low-

and middle countries (Albanese et al., 2017).

Alcohol is the most common and rapidly growing recreational drug in almost every

culture, and psychotropic drugs are often used in almost every culture. Only about

57% of the global population has not drunk alcohol in the previous year (Beydoun et

al., 2014). Alcohol consumption is widely acknowledged to have potential negative

effects and to make a significant contribution global burden of disease. More than

200 health conditions, ranging from liver disease to cancer, have been connected to

harmful alcohol use (Day et al., 2013).

Dementia is a widely acknowledged significant public health concern due to the

growing number of individuals living with the condition and the associated health,

socioeconomic, and economic costs (Kivimaki et al., 2020). Thus, Targeting the risk

contributing factors in the pathophysiological mechanisms triggering dementia has

the opportunities for intervention and prevention. These consultations as well as

prevention strategies may differ depending on the type of dementia, with Alzheimer's

disease (AD) seems to be the most prevalent type, accompanied by vascular

dementia or other less common types of dementia (Letenneur et al., 2004).

However, no details were given of harmful alcohol and is used as a possible future

prevention and control target. Despite substantial evidence of alcohol's neurotoxicity

on the brain, the lack of alcohol use as a major risk factor for dementia could be due,

in portion, to seemingly contradictory scientific proof from epidemiological studies

(Peters et al., 2008). From the recent large-scale retrospective cohort which includes

more than 30 million from the French hospital patients suggested that alcohol plays a

crucial role for the development of dementia especially with people younger and 64

years old (Ridley et al., 2013). In the studies majority of the cases were considered

as patients observed with alcohol use disorder previously diagnosed with dementia.

Moreover, prior AUD diagnosis was reported to be associated to dementia amongst

all age and subgroup categories, and the identified relative risk (RR) of dementia

surpassed the RRs of all the other modifiable risk factors (Kim et al., 2012). Provided

these developments, and in context of the experience and knowledge regarding

diseases as well as the connections between alcohol consumption and cognitive

decline, it is surprising that the topic has not been widely investigated in relation to

dementia up to this point (Sabai, 2012). Thus, our scoping review address the gap

between the alcohol consumption and dementia especially by searching average

volume of alcohol uptake and heavy episodic drinking and also included AUD as

exposure gauges. And it aims to identify the relationship between alcohol

consumptions and different kinds of outcomes and relationship varies with different

types of dementia and also address the methodological limitations and challenges

faced in assessing this relation prior alcohol use and onset of dementia.

harmful alcohol use (Day et al., 2013).

Dementia is a widely acknowledged significant public health concern due to the

growing number of individuals living with the condition and the associated health,

socioeconomic, and economic costs (Kivimaki et al., 2020). Thus, Targeting the risk

contributing factors in the pathophysiological mechanisms triggering dementia has

the opportunities for intervention and prevention. These consultations as well as

prevention strategies may differ depending on the type of dementia, with Alzheimer's

disease (AD) seems to be the most prevalent type, accompanied by vascular

dementia or other less common types of dementia (Letenneur et al., 2004).

However, no details were given of harmful alcohol and is used as a possible future

prevention and control target. Despite substantial evidence of alcohol's neurotoxicity

on the brain, the lack of alcohol use as a major risk factor for dementia could be due,

in portion, to seemingly contradictory scientific proof from epidemiological studies

(Peters et al., 2008). From the recent large-scale retrospective cohort which includes

more than 30 million from the French hospital patients suggested that alcohol plays a

crucial role for the development of dementia especially with people younger and 64

years old (Ridley et al., 2013). In the studies majority of the cases were considered

as patients observed with alcohol use disorder previously diagnosed with dementia.

Moreover, prior AUD diagnosis was reported to be associated to dementia amongst

all age and subgroup categories, and the identified relative risk (RR) of dementia

surpassed the RRs of all the other modifiable risk factors (Kim et al., 2012). Provided

these developments, and in context of the experience and knowledge regarding

diseases as well as the connections between alcohol consumption and cognitive

decline, it is surprising that the topic has not been widely investigated in relation to

dementia up to this point (Sabai, 2012). Thus, our scoping review address the gap

between the alcohol consumption and dementia especially by searching average

volume of alcohol uptake and heavy episodic drinking and also included AUD as

exposure gauges. And it aims to identify the relationship between alcohol

consumptions and different kinds of outcomes and relationship varies with different

types of dementia and also address the methodological limitations and challenges

faced in assessing this relation prior alcohol use and onset of dementia.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

METHODS:

Pattern of the systematic search:

This scoping review was constructed from the systematic search to identify all the

published systematic review from January 2000 to January 2019 on PubMed,

Elsevier, ScienceDirect and google scholar using the combination keywords such as

alcohol use, Azhemier dieases, dementia, cognitive health, brain function and

memory according to the Arksey and O’Malleys’s, 2005 framework for scoping

review, the PRISMA guidelines. In addition, the World Alzheimer Reports were used

to find specific systematic reviews. A systematic search of grey review was

undertaken using Google, but few contributions met our inclusion criteria. Systematic

reviews as well as meta-analyses are highly likely to be reported in scientific

journals. A systematic search in the ScienceDirect has given no contribution to the

studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Reviews and meta-analyses were included if they provided a detailed description of

the systematic search process, along with a list of databases as well as search

terms. Narrative reviews that did not include an implied search strategy were not

permitted. In addition, included studies had to be systematic reviews that looked at

the relationship between alcohol use and cognitive health, dementia, Alzheimer's

disease, vascular and other dementias, brain function, or memory. There have also

been systematic reviews on the relationship between alcohol consumption and brain

structure. Studies are included in if they were published in 2000 or later in order to

be included in only reviews conducted utilizing research methodology requirements

similar to what is used today; however, this does not imply that the original studies

that underpin these reviews were only published in 2000 or later. The scoping review

also included the search of relative keywords such as alcohol related brain damage

or alcohol induced disorder in the nervous system, but no systematic or meta-

analysis was found in the recent search.

Pattern of the systematic search:

This scoping review was constructed from the systematic search to identify all the

published systematic review from January 2000 to January 2019 on PubMed,

Elsevier, ScienceDirect and google scholar using the combination keywords such as

alcohol use, Azhemier dieases, dementia, cognitive health, brain function and

memory according to the Arksey and O’Malleys’s, 2005 framework for scoping

review, the PRISMA guidelines. In addition, the World Alzheimer Reports were used

to find specific systematic reviews. A systematic search of grey review was

undertaken using Google, but few contributions met our inclusion criteria. Systematic

reviews as well as meta-analyses are highly likely to be reported in scientific

journals. A systematic search in the ScienceDirect has given no contribution to the

studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Reviews and meta-analyses were included if they provided a detailed description of

the systematic search process, along with a list of databases as well as search

terms. Narrative reviews that did not include an implied search strategy were not

permitted. In addition, included studies had to be systematic reviews that looked at

the relationship between alcohol use and cognitive health, dementia, Alzheimer's

disease, vascular and other dementias, brain function, or memory. There have also

been systematic reviews on the relationship between alcohol consumption and brain

structure. Studies are included in if they were published in 2000 or later in order to

be included in only reviews conducted utilizing research methodology requirements

similar to what is used today; however, this does not imply that the original studies

that underpin these reviews were only published in 2000 or later. The scoping review

also included the search of relative keywords such as alcohol related brain damage

or alcohol induced disorder in the nervous system, but no systematic or meta-

analysis was found in the recent search.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

DATA EXTRACTION:

All underlying individual studies were extracted for each review as well as meta-

analysis which managed to meet all inclusion criteria. Furthermore, the obtained data

on dementia diagnoses as well as alcohol exposure measurements, relevant data

about risk relationships, types of articles included, age restrictions, and review

conclusions The searches were carried out by two researchers, who then scanned

the results for inclusion.

RESULTS:

Identification of relevant studies:

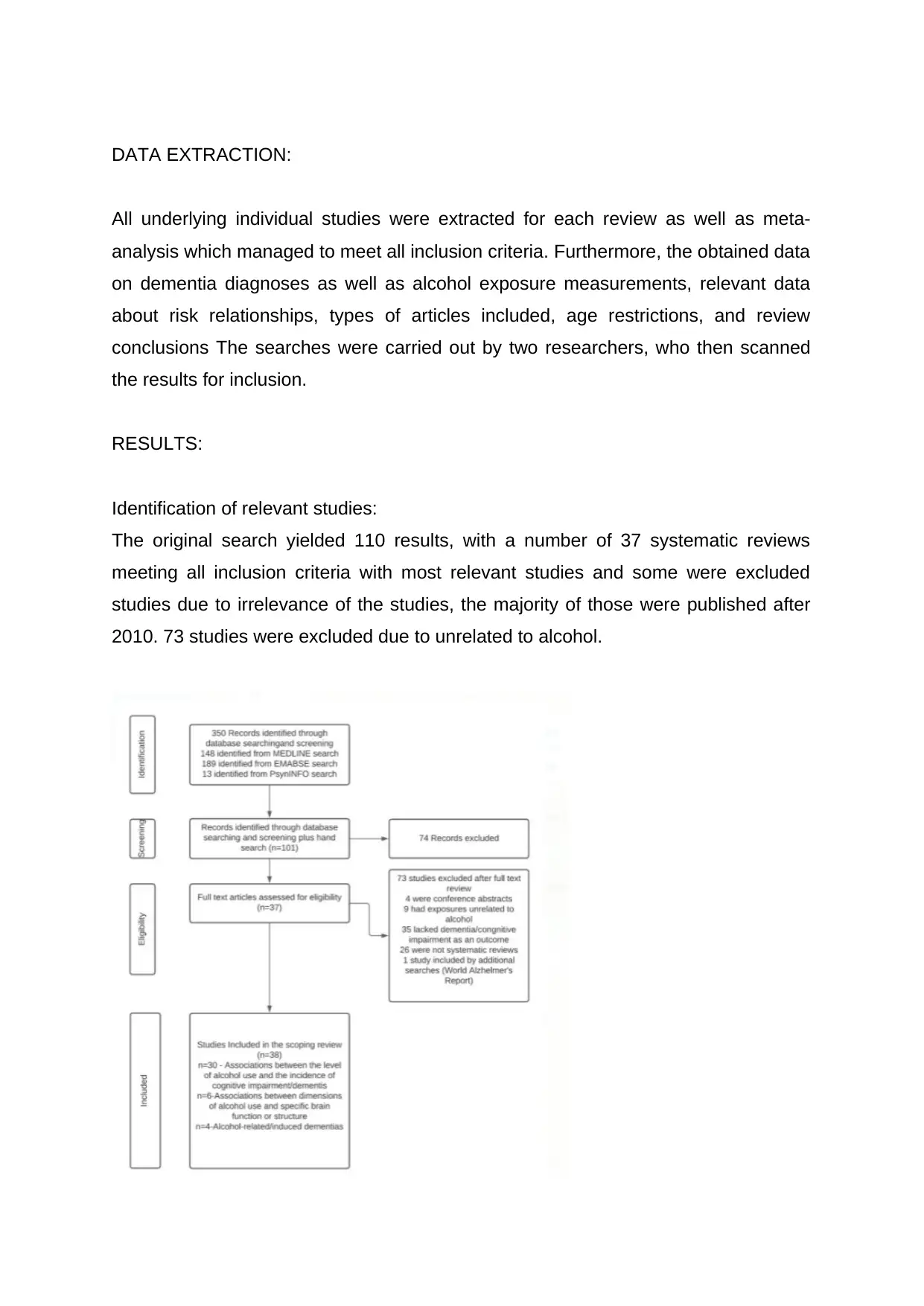

The original search yielded 110 results, with a number of 37 systematic reviews

meeting all inclusion criteria with most relevant studies and some were excluded

studies due to irrelevance of the studies, the majority of those were published after

2010. 73 studies were excluded due to unrelated to alcohol.

All underlying individual studies were extracted for each review as well as meta-

analysis which managed to meet all inclusion criteria. Furthermore, the obtained data

on dementia diagnoses as well as alcohol exposure measurements, relevant data

about risk relationships, types of articles included, age restrictions, and review

conclusions The searches were carried out by two researchers, who then scanned

the results for inclusion.

RESULTS:

Identification of relevant studies:

The original search yielded 110 results, with a number of 37 systematic reviews

meeting all inclusion criteria with most relevant studies and some were excluded

studies due to irrelevance of the studies, the majority of those were published after

2010. 73 studies were excluded due to unrelated to alcohol.

Figure 1: indicates the study selection process.

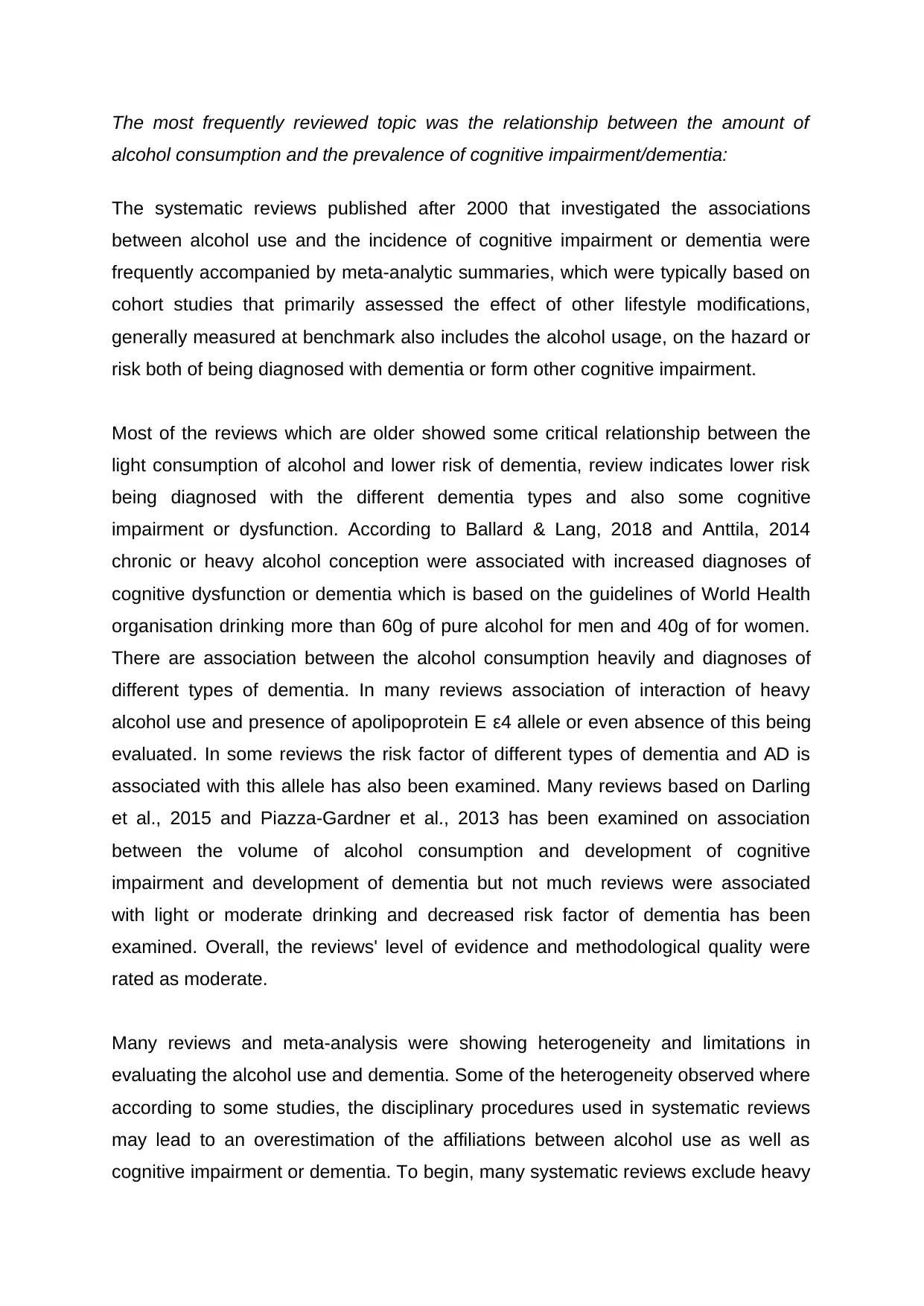

Study characteristics:

1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

number

Figure 2: indicates the number of studies published according to the year.

Alcohol consumption and

dementia alcohol consumption and

other brain injuries alcohol and induced

dementia

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

Chart Title

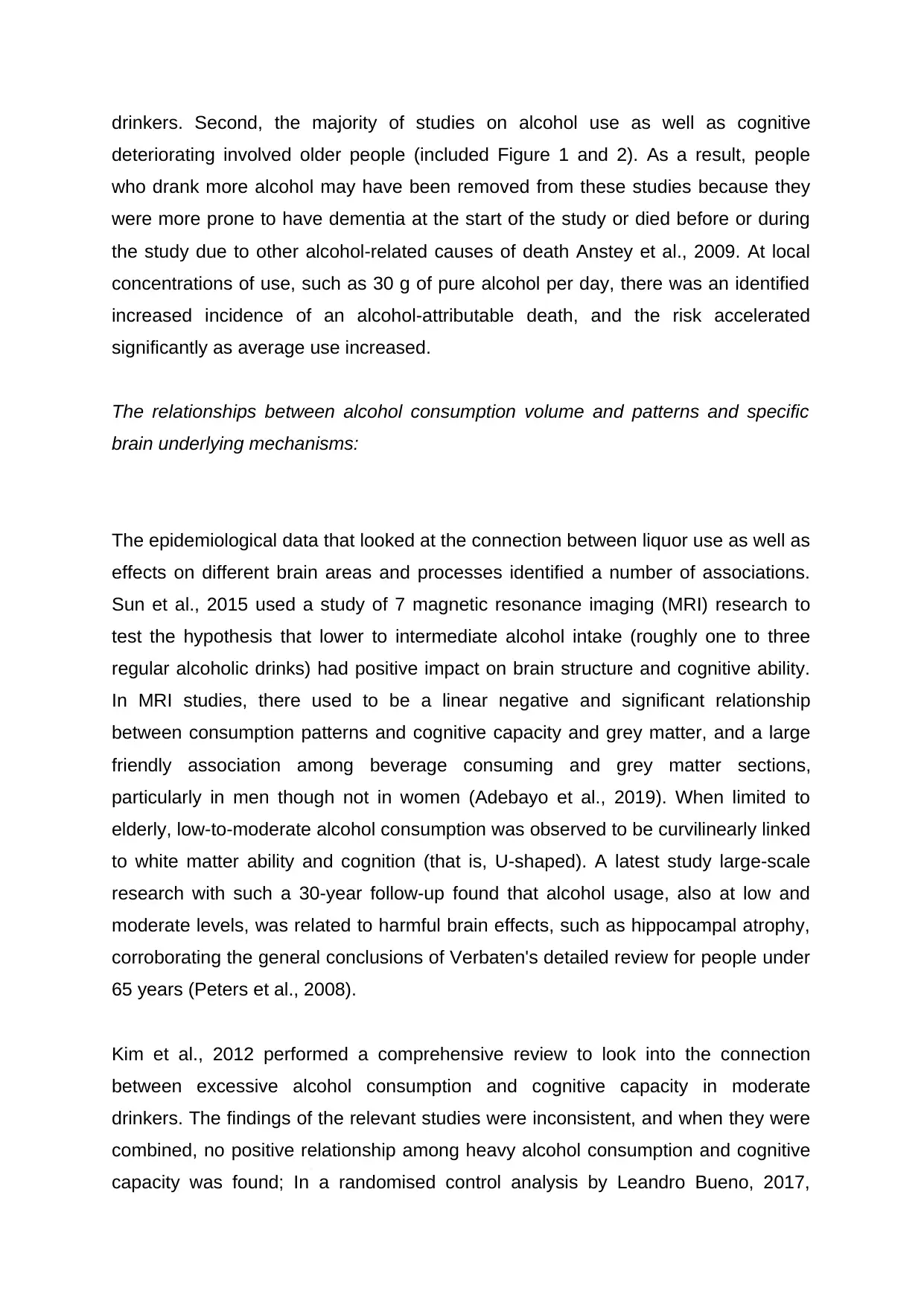

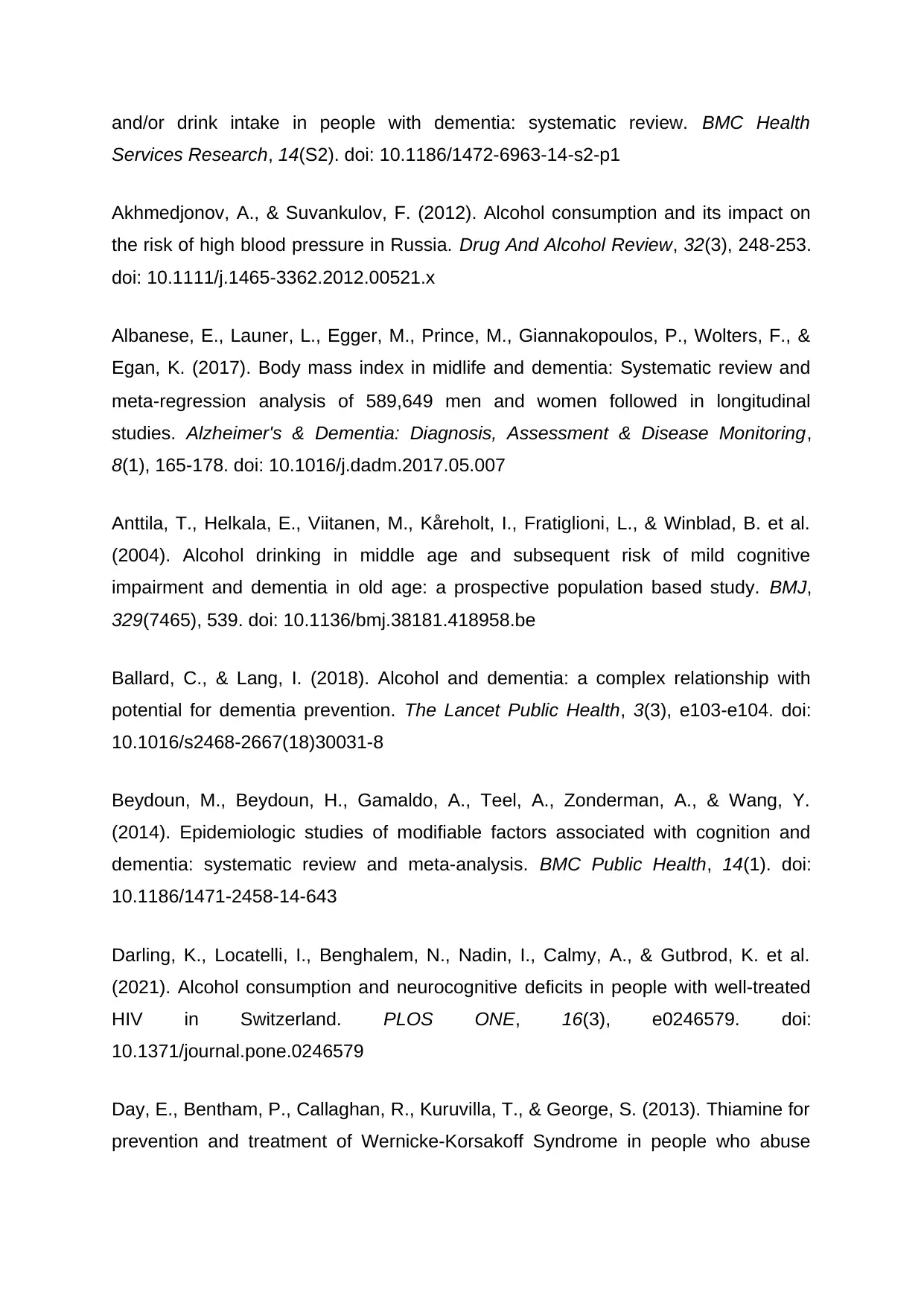

Figure 3: indicates the frequency of the studies to each outcomes.

RESEARCH TOPICS OUTCOMES:

Study characteristics:

1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

number

Figure 2: indicates the number of studies published according to the year.

Alcohol consumption and

dementia alcohol consumption and

other brain injuries alcohol and induced

dementia

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

Chart Title

Figure 3: indicates the frequency of the studies to each outcomes.

RESEARCH TOPICS OUTCOMES:

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The most frequently reviewed topic was the relationship between the amount of

alcohol consumption and the prevalence of cognitive impairment/dementia:

The systematic reviews published after 2000 that investigated the associations

between alcohol use and the incidence of cognitive impairment or dementia were

frequently accompanied by meta-analytic summaries, which were typically based on

cohort studies that primarily assessed the effect of other lifestyle modifications,

generally measured at benchmark also includes the alcohol usage, on the hazard or

risk both of being diagnosed with dementia or form other cognitive impairment.

Most of the reviews which are older showed some critical relationship between the

light consumption of alcohol and lower risk of dementia, review indicates lower risk

being diagnosed with the different dementia types and also some cognitive

impairment or dysfunction. According to Ballard & Lang, 2018 and Anttila, 2014

chronic or heavy alcohol conception were associated with increased diagnoses of

cognitive dysfunction or dementia which is based on the guidelines of World Health

organisation drinking more than 60g of pure alcohol for men and 40g of for women.

There are association between the alcohol consumption heavily and diagnoses of

different types of dementia. In many reviews association of interaction of heavy

alcohol use and presence of apolipoprotein E ε4 allele or even absence of this being

evaluated. In some reviews the risk factor of different types of dementia and AD is

associated with this allele has also been examined. Many reviews based on Darling

et al., 2015 and Piazza-Gardner et al., 2013 has been examined on association

between the volume of alcohol consumption and development of cognitive

impairment and development of dementia but not much reviews were associated

with light or moderate drinking and decreased risk factor of dementia has been

examined. Overall, the reviews' level of evidence and methodological quality were

rated as moderate.

Many reviews and meta-analysis were showing heterogeneity and limitations in

evaluating the alcohol use and dementia. Some of the heterogeneity observed where

according to some studies, the disciplinary procedures used in systematic reviews

may lead to an overestimation of the affiliations between alcohol use as well as

cognitive impairment or dementia. To begin, many systematic reviews exclude heavy

alcohol consumption and the prevalence of cognitive impairment/dementia:

The systematic reviews published after 2000 that investigated the associations

between alcohol use and the incidence of cognitive impairment or dementia were

frequently accompanied by meta-analytic summaries, which were typically based on

cohort studies that primarily assessed the effect of other lifestyle modifications,

generally measured at benchmark also includes the alcohol usage, on the hazard or

risk both of being diagnosed with dementia or form other cognitive impairment.

Most of the reviews which are older showed some critical relationship between the

light consumption of alcohol and lower risk of dementia, review indicates lower risk

being diagnosed with the different dementia types and also some cognitive

impairment or dysfunction. According to Ballard & Lang, 2018 and Anttila, 2014

chronic or heavy alcohol conception were associated with increased diagnoses of

cognitive dysfunction or dementia which is based on the guidelines of World Health

organisation drinking more than 60g of pure alcohol for men and 40g of for women.

There are association between the alcohol consumption heavily and diagnoses of

different types of dementia. In many reviews association of interaction of heavy

alcohol use and presence of apolipoprotein E ε4 allele or even absence of this being

evaluated. In some reviews the risk factor of different types of dementia and AD is

associated with this allele has also been examined. Many reviews based on Darling

et al., 2015 and Piazza-Gardner et al., 2013 has been examined on association

between the volume of alcohol consumption and development of cognitive

impairment and development of dementia but not much reviews were associated

with light or moderate drinking and decreased risk factor of dementia has been

examined. Overall, the reviews' level of evidence and methodological quality were

rated as moderate.

Many reviews and meta-analysis were showing heterogeneity and limitations in

evaluating the alcohol use and dementia. Some of the heterogeneity observed where

according to some studies, the disciplinary procedures used in systematic reviews

may lead to an overestimation of the affiliations between alcohol use as well as

cognitive impairment or dementia. To begin, many systematic reviews exclude heavy

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

drinkers. Second, the majority of studies on alcohol use as well as cognitive

deteriorating involved older people (included Figure 1 and 2). As a result, people

who drank more alcohol may have been removed from these studies because they

were more prone to have dementia at the start of the study or died before or during

the study due to other alcohol-related causes of death Anstey et al., 2009. At local

concentrations of use, such as 30 g of pure alcohol per day, there was an identified

increased incidence of an alcohol-attributable death, and the risk accelerated

significantly as average use increased.

The relationships between alcohol consumption volume and patterns and specific

brain underlying mechanisms:

The epidemiological data that looked at the connection between liquor use as well as

effects on different brain areas and processes identified a number of associations.

Sun et al., 2015 used a study of 7 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) research to

test the hypothesis that lower to intermediate alcohol intake (roughly one to three

regular alcoholic drinks) had positive impact on brain structure and cognitive ability.

In MRI studies, there used to be a linear negative and significant relationship

between consumption patterns and cognitive capacity and grey matter, and a large

friendly association among beverage consuming and grey matter sections,

particularly in men though not in women (Adebayo et al., 2019). When limited to

elderly, low-to-moderate alcohol consumption was observed to be curvilinearly linked

to white matter ability and cognition (that is, U-shaped). A latest study large-scale

research with such a 30-year follow-up found that alcohol usage, also at low and

moderate levels, was related to harmful brain effects, such as hippocampal atrophy,

corroborating the general conclusions of Verbaten's detailed review for people under

65 years (Peters et al., 2008).

Kim et al., 2012 performed a comprehensive review to look into the connection

between excessive alcohol consumption and cognitive capacity in moderate

drinkers. The findings of the relevant studies were inconsistent, and when they were

combined, no positive relationship among heavy alcohol consumption and cognitive

capacity was found; In a randomised control analysis by Leandro Bueno, 2017,

deteriorating involved older people (included Figure 1 and 2). As a result, people

who drank more alcohol may have been removed from these studies because they

were more prone to have dementia at the start of the study or died before or during

the study due to other alcohol-related causes of death Anstey et al., 2009. At local

concentrations of use, such as 30 g of pure alcohol per day, there was an identified

increased incidence of an alcohol-attributable death, and the risk accelerated

significantly as average use increased.

The relationships between alcohol consumption volume and patterns and specific

brain underlying mechanisms:

The epidemiological data that looked at the connection between liquor use as well as

effects on different brain areas and processes identified a number of associations.

Sun et al., 2015 used a study of 7 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) research to

test the hypothesis that lower to intermediate alcohol intake (roughly one to three

regular alcoholic drinks) had positive impact on brain structure and cognitive ability.

In MRI studies, there used to be a linear negative and significant relationship

between consumption patterns and cognitive capacity and grey matter, and a large

friendly association among beverage consuming and grey matter sections,

particularly in men though not in women (Adebayo et al., 2019). When limited to

elderly, low-to-moderate alcohol consumption was observed to be curvilinearly linked

to white matter ability and cognition (that is, U-shaped). A latest study large-scale

research with such a 30-year follow-up found that alcohol usage, also at low and

moderate levels, was related to harmful brain effects, such as hippocampal atrophy,

corroborating the general conclusions of Verbaten's detailed review for people under

65 years (Peters et al., 2008).

Kim et al., 2012 performed a comprehensive review to look into the connection

between excessive alcohol consumption and cognitive capacity in moderate

drinkers. The findings of the relevant studies were inconsistent, and when they were

combined, no positive relationship among heavy alcohol consumption and cognitive

capacity was found; In a randomised control analysis by Leandro Bueno, 2017,

heavy alcohol use was positively associated with all sub-measures of cognitive

ability except memory updating. As a consequence, the negative effects of

consumption of alcohol can be mitigated by a reduction in cognitive capacity.

Excessive alcohol use has a clear detrimental impact on cognitive functions and their

ability to function efficiently, according to two systematic approaches that are based

on imaging studies. The systemic effects have also been confirmed by autopsy

reports. The structural and functional consequences of heavy usage have been

confirmed in a variety of possible narrative analyses (Luchsinger et al., 2004).

Dementia triggered or induced by alcohol:

Heavy use of alcohol has been considered as important factor for contribution of

development of multiple brain diseases and also use of alcohol can dramage relative

many brain nerves in different ways. In review of (Venkataraman et al., 2017) stated

that ethanol and its receptor acetaldehyde are neurotoxic, causing permanent brain

structure and function damage. Second, chronic heavy alcohol use can lead to

thiamine deficiency by causing insufficient nutritional thiamine intake, with decreased

thiamine absorption from the intestinal system, and impaired thiamine usage in the

cells, resulting in Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome according to Scalzo et al., 2015.

Even though the treatment of thiamine reverse administration can reduce the

syndrome but certain chronic neuropsychiatric is being observed in many patients

according to Scalzo et al., 2015. In some review the heavy use of alcohol can also

lead to damages in the brain which leads to cause of epilepsy, head injury and liver

dieases. Heavy alcohol use can also indirectly associate the vascular dementia

which can cause many vascular diseases includes hypertension, coronary heart

disease, cardiomyopathy, fibrillation, and stroke. Finally, excessive alcohol

consumption is linked to lower levels of learning, tobacco use, and anxiety, that are

all possible causes for dementia (Yates et al., 2016).

DISCUSSION:

In various observational studies, light to moderate liquor use from middle to late

adulthood was associated with a lower risk of cognitive impairment and dementia;

however, there were contradictory findings, and because of various methodological

ability except memory updating. As a consequence, the negative effects of

consumption of alcohol can be mitigated by a reduction in cognitive capacity.

Excessive alcohol use has a clear detrimental impact on cognitive functions and their

ability to function efficiently, according to two systematic approaches that are based

on imaging studies. The systemic effects have also been confirmed by autopsy

reports. The structural and functional consequences of heavy usage have been

confirmed in a variety of possible narrative analyses (Luchsinger et al., 2004).

Dementia triggered or induced by alcohol:

Heavy use of alcohol has been considered as important factor for contribution of

development of multiple brain diseases and also use of alcohol can dramage relative

many brain nerves in different ways. In review of (Venkataraman et al., 2017) stated

that ethanol and its receptor acetaldehyde are neurotoxic, causing permanent brain

structure and function damage. Second, chronic heavy alcohol use can lead to

thiamine deficiency by causing insufficient nutritional thiamine intake, with decreased

thiamine absorption from the intestinal system, and impaired thiamine usage in the

cells, resulting in Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome according to Scalzo et al., 2015.

Even though the treatment of thiamine reverse administration can reduce the

syndrome but certain chronic neuropsychiatric is being observed in many patients

according to Scalzo et al., 2015. In some review the heavy use of alcohol can also

lead to damages in the brain which leads to cause of epilepsy, head injury and liver

dieases. Heavy alcohol use can also indirectly associate the vascular dementia

which can cause many vascular diseases includes hypertension, coronary heart

disease, cardiomyopathy, fibrillation, and stroke. Finally, excessive alcohol

consumption is linked to lower levels of learning, tobacco use, and anxiety, that are

all possible causes for dementia (Yates et al., 2016).

DISCUSSION:

In various observational studies, light to moderate liquor use from middle to late

adulthood was associated with a lower risk of cognitive impairment and dementia;

however, there were contradictory findings, and because of various methodological

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

flaws, causality of this association couldn't be established. In observational and

imaging studies, heavy alcohol use was linked to changes in brain structures as well

as psychological and leadership difficulties. Significant alcohol use and AUDs were

also linked to an increased risk of a variety of dementias. Furthermore, a liquor

consumption limit above which sensitivity would be impaired may exist but has not

yet been identified.

The large degree of heterogeneity in the operationalization of results and the low

level of coverage of basic examinations between surveys hampered this checking

audit. This heterogeneity in result operationalization may have contributed to the

previously mentioned contradictory findings regarding light to direct drinking. As a

result, there is also a requirement for the use of normalized target proportions of

dementia and intellectual decay based on current agreement standards. More

extensive studies utilizing newer dementia, hereditary, and neuroimaging biomarkers

are expected to set up more clear guidelines for cutting edge clinicians in a time

when dementia anticipation is a public and individual wellbeing need.

The observational epidemiological studies hidden in the surveys listed in Figure 1

and 2 were limited because the majority of the examinations were limited to more

established populations. More research is required in agent more youthful

populations with long in general subsequent meetups and better philosophies, for

example, the utilization of imaging procedures and standardized psychological tests

at various subsequent focuses, joined with various proportions of baseline

measurement and the same subsequent focus. Furthermore, the majority of the

observational examination populations are not agents of heavy liquor clients or

individuals with AUDs, as these people are frequently prohibited by plan. Hefty liquor

clients and individuals with AUDs were barred from the examining outlines, were

forced to leave, and were forced to die at younger ages. To address these

impediments, future epidemiological studies on the role of heavy liquor use and

AUDs on dementia could begin in an emergency clinic setting where people with

such characteristics are over-treated.

According to review, the dangers of heavy drinking and AUDs for dementia have

been minimized. The French medical clinic companion study, which found that AUDs

imaging studies, heavy alcohol use was linked to changes in brain structures as well

as psychological and leadership difficulties. Significant alcohol use and AUDs were

also linked to an increased risk of a variety of dementias. Furthermore, a liquor

consumption limit above which sensitivity would be impaired may exist but has not

yet been identified.

The large degree of heterogeneity in the operationalization of results and the low

level of coverage of basic examinations between surveys hampered this checking

audit. This heterogeneity in result operationalization may have contributed to the

previously mentioned contradictory findings regarding light to direct drinking. As a

result, there is also a requirement for the use of normalized target proportions of

dementia and intellectual decay based on current agreement standards. More

extensive studies utilizing newer dementia, hereditary, and neuroimaging biomarkers

are expected to set up more clear guidelines for cutting edge clinicians in a time

when dementia anticipation is a public and individual wellbeing need.

The observational epidemiological studies hidden in the surveys listed in Figure 1

and 2 were limited because the majority of the examinations were limited to more

established populations. More research is required in agent more youthful

populations with long in general subsequent meetups and better philosophies, for

example, the utilization of imaging procedures and standardized psychological tests

at various subsequent focuses, joined with various proportions of baseline

measurement and the same subsequent focus. Furthermore, the majority of the

observational examination populations are not agents of heavy liquor clients or

individuals with AUDs, as these people are frequently prohibited by plan. Hefty liquor

clients and individuals with AUDs were barred from the examining outlines, were

forced to leave, and were forced to die at younger ages. To address these

impediments, future epidemiological studies on the role of heavy liquor use and

AUDs on dementia could begin in an emergency clinic setting where people with

such characteristics are over-treated.

According to review, the dangers of heavy drinking and AUDs for dementia have

been minimized. The French medical clinic companion study, which found that AUDs

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

had the highest RR for dementia of any modifiable risk factor for dementia,

established that liquor use should be considered by our health and social

government assistance frameworks. Replication centres from various countries

would also add to the evidence base.

Mendelian randomization studies may aid in determining causality; however, the

findings from such studies have yet to demonstrate a causal effect of liquor on

advertisement or psychological working/hindrance. A portion of the hereditary

markers used for liquor utilization are risky because their relationship with normal

volume of drinking and with hefty severing events by and large light consumers point

in inverse directions see also the discussion below. Furthermore, partner

concentrations in twins may contribute to distinguishing hereditary variations.

CONCLUSIONS:

Given the lack of comprehensive research on AD, alcohol, cognitive dysfunction and

dementia, future randomized anticipation and optional avoidance preliminaries with

liquor use interventions are required. Such investigations would incorporate

hereditary profiles, normalized cognition, mind-set and conduct evaluations, and

measurement of primary and practical availability cerebrum measures, which are

commonly used for dementia and were discovered to be underutilized in the current

reading survey. Such preliminaries would be arranged overwhelmingly in the primary

medical care framework, where screening and brief mediations have been

demonstrated to decrease significant liquor utilization and where a large number of

the less serious AUDs can be dealt with. Finally, because the expansion of new

investigations of existing and progressing accomplice studies will be influenced by

the recently mentioned constraints, there is a requirement for future research to

address these constraints.

REFERENCES:

Abdelhamid, A., Bunn, D., Dickinson, A., Killett, A., Poland, F., & Potter, J. et al.

(2014). Effectiveness of interventions to improve, maintain or facilitate oral food

established that liquor use should be considered by our health and social

government assistance frameworks. Replication centres from various countries

would also add to the evidence base.

Mendelian randomization studies may aid in determining causality; however, the

findings from such studies have yet to demonstrate a causal effect of liquor on

advertisement or psychological working/hindrance. A portion of the hereditary

markers used for liquor utilization are risky because their relationship with normal

volume of drinking and with hefty severing events by and large light consumers point

in inverse directions see also the discussion below. Furthermore, partner

concentrations in twins may contribute to distinguishing hereditary variations.

CONCLUSIONS:

Given the lack of comprehensive research on AD, alcohol, cognitive dysfunction and

dementia, future randomized anticipation and optional avoidance preliminaries with

liquor use interventions are required. Such investigations would incorporate

hereditary profiles, normalized cognition, mind-set and conduct evaluations, and

measurement of primary and practical availability cerebrum measures, which are

commonly used for dementia and were discovered to be underutilized in the current

reading survey. Such preliminaries would be arranged overwhelmingly in the primary

medical care framework, where screening and brief mediations have been

demonstrated to decrease significant liquor utilization and where a large number of

the less serious AUDs can be dealt with. Finally, because the expansion of new

investigations of existing and progressing accomplice studies will be influenced by

the recently mentioned constraints, there is a requirement for future research to

address these constraints.

REFERENCES:

Abdelhamid, A., Bunn, D., Dickinson, A., Killett, A., Poland, F., & Potter, J. et al.

(2014). Effectiveness of interventions to improve, maintain or facilitate oral food

and/or drink intake in people with dementia: systematic review. BMC Health

Services Research, 14(S2). doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-s2-p1

Akhmedjonov, A., & Suvankulov, F. (2012). Alcohol consumption and its impact on

the risk of high blood pressure in Russia. Drug And Alcohol Review, 32(3), 248-253.

doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00521.x

Albanese, E., Launer, L., Egger, M., Prince, M., Giannakopoulos, P., Wolters, F., &

Egan, K. (2017). Body mass index in midlife and dementia: Systematic review and

meta‐regression analysis of 589,649 men and women followed in longitudinal

studies. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring,

8(1), 165-178. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.05.007

Anttila, T., Helkala, E., Viitanen, M., Kåreholt, I., Fratiglioni, L., & Winblad, B. et al.

(2004). Alcohol drinking in middle age and subsequent risk of mild cognitive

impairment and dementia in old age: a prospective population based study. BMJ,

329(7465), 539. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38181.418958.be

Ballard, C., & Lang, I. (2018). Alcohol and dementia: a complex relationship with

potential for dementia prevention. The Lancet Public Health, 3(3), e103-e104. doi:

10.1016/s2468-2667(18)30031-8

Beydoun, M., Beydoun, H., Gamaldo, A., Teel, A., Zonderman, A., & Wang, Y.

(2014). Epidemiologic studies of modifiable factors associated with cognition and

dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 14(1). doi:

10.1186/1471-2458-14-643

Darling, K., Locatelli, I., Benghalem, N., Nadin, I., Calmy, A., & Gutbrod, K. et al.

(2021). Alcohol consumption and neurocognitive deficits in people with well-treated

HIV in Switzerland. PLOS ONE, 16(3), e0246579. doi:

10.1371/journal.pone.0246579

Day, E., Bentham, P., Callaghan, R., Kuruvilla, T., & George, S. (2013). Thiamine for

prevention and treatment of Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome in people who abuse

Services Research, 14(S2). doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-s2-p1

Akhmedjonov, A., & Suvankulov, F. (2012). Alcohol consumption and its impact on

the risk of high blood pressure in Russia. Drug And Alcohol Review, 32(3), 248-253.

doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00521.x

Albanese, E., Launer, L., Egger, M., Prince, M., Giannakopoulos, P., Wolters, F., &

Egan, K. (2017). Body mass index in midlife and dementia: Systematic review and

meta‐regression analysis of 589,649 men and women followed in longitudinal

studies. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring,

8(1), 165-178. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.05.007

Anttila, T., Helkala, E., Viitanen, M., Kåreholt, I., Fratiglioni, L., & Winblad, B. et al.

(2004). Alcohol drinking in middle age and subsequent risk of mild cognitive

impairment and dementia in old age: a prospective population based study. BMJ,

329(7465), 539. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38181.418958.be

Ballard, C., & Lang, I. (2018). Alcohol and dementia: a complex relationship with

potential for dementia prevention. The Lancet Public Health, 3(3), e103-e104. doi:

10.1016/s2468-2667(18)30031-8

Beydoun, M., Beydoun, H., Gamaldo, A., Teel, A., Zonderman, A., & Wang, Y.

(2014). Epidemiologic studies of modifiable factors associated with cognition and

dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 14(1). doi:

10.1186/1471-2458-14-643

Darling, K., Locatelli, I., Benghalem, N., Nadin, I., Calmy, A., & Gutbrod, K. et al.

(2021). Alcohol consumption and neurocognitive deficits in people with well-treated

HIV in Switzerland. PLOS ONE, 16(3), e0246579. doi:

10.1371/journal.pone.0246579

Day, E., Bentham, P., Callaghan, R., Kuruvilla, T., & George, S. (2013). Thiamine for

prevention and treatment of Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome in people who abuse

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 16

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.