SEB725 Engineering Entrepreneurship: Eastern Kentucky Adolescents

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/08

|14

|6622

|407

Report

AI Summary

This research examines the entrepreneurial attitudes of high school seniors in Eastern Kentucky and their preferences to stay or leave the region. Using the GET2Test, the study measures enterprising tendency and its components like need for achievement, creative tendency, and calculated risk-taking. The findings indicate that few students exhibit high levels of enterprising tendency and that those who do are more likely to leave Eastern Kentucky for education and career opportunities. The report discusses the implications of these findings for economic development in the region, highlighting the need for entrepreneurship education to reverse outward migration and improve future prospects. It also contextualizes Eastern Kentucky's socioeconomic challenges, including its history of poverty and dependence on the coal industry, emphasizing the importance of fostering an entrepreneurial ecosystem to promote innovation and economic diversification. This document is available on Desklib, a platform offering a wide range of academic resources and study tools for students.

Small Business Institute® Journal Small Business Institute®

2017, Vol. 13, No. 2, 1-14 ISSN: 1994-1150/69

Full Citation:

Snow, D. and Prater, J. (2017). Entrepreneurship Elsewhere: Examining the Entrepreneurial

Characteristics of Eastern Kentucky Adolescents. Small Business Institute® Journal. Vol. 13, No. 2., pp.

1-14

Entrepreneurship Elsewhere: Examining the Entrepreneurial Characteristics

of Eastern Kentucky Adolescents

David Snow

DavidSnow@upike.edu

University of Pikeville and the Kentucky Innovation Network

Justin Prater

University of Pikeville and the Kentucky Innovation Network

Abstract

Entrepreneurshipis known as a legitimate academic discipline and significant

contributor to economic development. Eastern Kentucky is known for its high levels of

poverty and unemployment. This research examines the entrepreneurial attitudes of hig

school seniors and their preferences to remain in or leave Eastern Kentucky. Findings

indicate few students scored in the high level of enterprisingtendency and the

entrepreneurial characteristics of need for achievement, calculated risk-taking, and

creative tendency. Findings also indicate those with a high level of enterprising tendenc

are more likely to leave Eastern Kentucky for education and career with no intention of

returning.

Keywords: Entrepreneurship; Education; Poverty; Socioeconomic Status

Introduction

“Entrepreneurship Everywhere” is the current slogan for the United States Association

for Small Businessand Entrepreneurship(USASBE). This is one of the premier

organizations for post-secondary teaching, research, and experiential learning in th

entrepreneurship discipline. The reason for this motto is obvious. In many parts of the

U.S. and the world, entrepreneurship is thriving. In 1975, only one hundred form

majors, minors, and certificates existed, but over the last twenty years entrepreneurship

has emerged as a mainstream discipline (Lee et al., 2005; Torrance et al., 2013).

According to Kuratko (2014), over 1,000 schools offer majors in entrepreneurship and

over 2,200 universities teach at least one course in entrepreneurship. Along with this

growth, an increasein business plan competitions,technologycommercialization

programs, product development activities, and startup company internships has occurred

(Duval-Couetil, 2013).

Entrepreneurship education is now also widely offered in secondary schools. With

organizations such as Junior Achievement (JA), the Kauffman Foundation, the Young

Entrepreneurs Academy (YEA), the Network for Teaching Entrepreneurship (NFTE), and

university-based programs, millions of students each year are taught entrepreneurship

(Frazier, 2014; Hamilton, & Hamilton, 2012; Lorz, Mueller, & Volery, 2013).

Entrepreneurship education at the secondary and post-secondary levels has been shown

2017, Vol. 13, No. 2, 1-14 ISSN: 1994-1150/69

Full Citation:

Snow, D. and Prater, J. (2017). Entrepreneurship Elsewhere: Examining the Entrepreneurial

Characteristics of Eastern Kentucky Adolescents. Small Business Institute® Journal. Vol. 13, No. 2., pp.

1-14

Entrepreneurship Elsewhere: Examining the Entrepreneurial Characteristics

of Eastern Kentucky Adolescents

David Snow

DavidSnow@upike.edu

University of Pikeville and the Kentucky Innovation Network

Justin Prater

University of Pikeville and the Kentucky Innovation Network

Abstract

Entrepreneurshipis known as a legitimate academic discipline and significant

contributor to economic development. Eastern Kentucky is known for its high levels of

poverty and unemployment. This research examines the entrepreneurial attitudes of hig

school seniors and their preferences to remain in or leave Eastern Kentucky. Findings

indicate few students scored in the high level of enterprisingtendency and the

entrepreneurial characteristics of need for achievement, calculated risk-taking, and

creative tendency. Findings also indicate those with a high level of enterprising tendenc

are more likely to leave Eastern Kentucky for education and career with no intention of

returning.

Keywords: Entrepreneurship; Education; Poverty; Socioeconomic Status

Introduction

“Entrepreneurship Everywhere” is the current slogan for the United States Association

for Small Businessand Entrepreneurship(USASBE). This is one of the premier

organizations for post-secondary teaching, research, and experiential learning in th

entrepreneurship discipline. The reason for this motto is obvious. In many parts of the

U.S. and the world, entrepreneurship is thriving. In 1975, only one hundred form

majors, minors, and certificates existed, but over the last twenty years entrepreneurship

has emerged as a mainstream discipline (Lee et al., 2005; Torrance et al., 2013).

According to Kuratko (2014), over 1,000 schools offer majors in entrepreneurship and

over 2,200 universities teach at least one course in entrepreneurship. Along with this

growth, an increasein business plan competitions,technologycommercialization

programs, product development activities, and startup company internships has occurred

(Duval-Couetil, 2013).

Entrepreneurship education is now also widely offered in secondary schools. With

organizations such as Junior Achievement (JA), the Kauffman Foundation, the Young

Entrepreneurs Academy (YEA), the Network for Teaching Entrepreneurship (NFTE), and

university-based programs, millions of students each year are taught entrepreneurship

(Frazier, 2014; Hamilton, & Hamilton, 2012; Lorz, Mueller, & Volery, 2013).

Entrepreneurship education at the secondary and post-secondary levels has been shown

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Small Business Institute® Journal – Vol. 13, No. 2, 1-14

Snow and Prater Pg. 2

to positively impact students’ self-efficacy, desire to attend college, academic succ

attitude toward entrepreneurship, intention to become entrepreneurs, business skil

and desirability by employers (Abu Talib et al., 2012; Brown, Bowlus, & Seibert 2

Hernandez & Newman, 2009; McNally, Martin, & Kay, 2010; NFTE, 2011; Studda

Dawson, & Jackson, 2013).

It is known entrepreneurship is integral in the efforts of innovation and economic

development (Acs & Audretsch, 2003; Audretsch & Keilbach, 2004; Baumol, 2002;

Hessels & van Stel, 2011; Morris, Neumeyer, & Kuratko, 2015). Research has specifical

examined entrepreneurship as an effective strategy for economic development in rural

areas as well (Jaafar, Dahalan, & Rosdi, 2014; Mojica, Gebremedhim, T., & Schaeffer,

2010; Robinson, Dassie, & Christy, 2004). Entrepreneurial startups are typically born as

small businesses. The majority of small business creations remain classified as sm

businessesthroughouttheir lifespan (Clayton et al., 2013). Even though these

organizations employ less than five hundred employees each, the economic contribution

is significant. In 2011, there were 28.2 million small businesses. Small business

comprise 99.7 percent of U.S. firms, are responsible for 63 percent of net new private-

sector jobs, and employ 49.2% of all private-sector workers (Audretsch & Link, 2012; SB

2014).

Eastern Kentucky

Eastern Kentucky sits in the central region of the Appalachian Mountains. Consisting of

such a vast area, the Appalachian Mountains run from southern New York to northern

Mississippi in eastern North America and include 420 counties in 13 states. Appalachia

is classified into northern, southern, and central regions. Historically, communities in

Appalachia have lagged behind the rest of the country and Central Appalachia is

poorest performing of the three regions (Bauman, 2006; Stephens and Partridge, 2011).

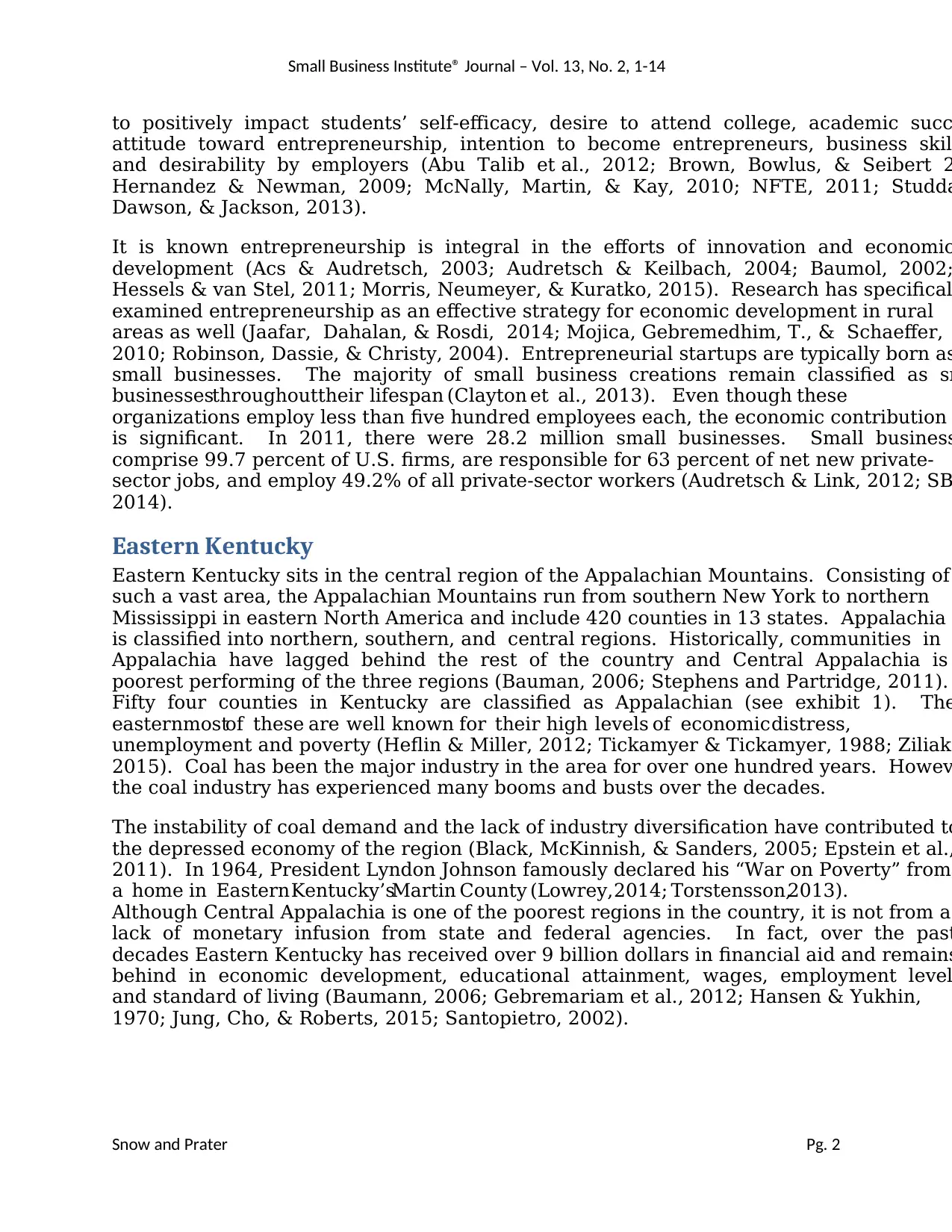

Fifty four counties in Kentucky are classified as Appalachian (see exhibit 1). The

easternmostof these are well known for their high levels of economic distress,

unemployment and poverty (Heflin & Miller, 2012; Tickamyer & Tickamyer, 1988; Ziliak,

2015). Coal has been the major industry in the area for over one hundred years. Howev

the coal industry has experienced many booms and busts over the decades.

The instability of coal demand and the lack of industry diversification have contributed to

the depressed economy of the region (Black, McKinnish, & Sanders, 2005; Epstein et al.,

2011). In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson famously declared his “War on Poverty” from

a home in Eastern Kentucky’sMartin County (Lowrey, 2014; Torstensson,2013).

Although Central Appalachia is one of the poorest regions in the country, it is not from a

lack of monetary infusion from state and federal agencies. In fact, over the past

decades Eastern Kentucky has received over 9 billion dollars in financial aid and remains

behind in economic development, educational attainment, wages, employment level

and standard of living (Baumann, 2006; Gebremariam et al., 2012; Hansen & Yukhin,

1970; Jung, Cho, & Roberts, 2015; Santopietro, 2002).

Snow and Prater Pg. 2

to positively impact students’ self-efficacy, desire to attend college, academic succ

attitude toward entrepreneurship, intention to become entrepreneurs, business skil

and desirability by employers (Abu Talib et al., 2012; Brown, Bowlus, & Seibert 2

Hernandez & Newman, 2009; McNally, Martin, & Kay, 2010; NFTE, 2011; Studda

Dawson, & Jackson, 2013).

It is known entrepreneurship is integral in the efforts of innovation and economic

development (Acs & Audretsch, 2003; Audretsch & Keilbach, 2004; Baumol, 2002;

Hessels & van Stel, 2011; Morris, Neumeyer, & Kuratko, 2015). Research has specifical

examined entrepreneurship as an effective strategy for economic development in rural

areas as well (Jaafar, Dahalan, & Rosdi, 2014; Mojica, Gebremedhim, T., & Schaeffer,

2010; Robinson, Dassie, & Christy, 2004). Entrepreneurial startups are typically born as

small businesses. The majority of small business creations remain classified as sm

businessesthroughouttheir lifespan (Clayton et al., 2013). Even though these

organizations employ less than five hundred employees each, the economic contribution

is significant. In 2011, there were 28.2 million small businesses. Small business

comprise 99.7 percent of U.S. firms, are responsible for 63 percent of net new private-

sector jobs, and employ 49.2% of all private-sector workers (Audretsch & Link, 2012; SB

2014).

Eastern Kentucky

Eastern Kentucky sits in the central region of the Appalachian Mountains. Consisting of

such a vast area, the Appalachian Mountains run from southern New York to northern

Mississippi in eastern North America and include 420 counties in 13 states. Appalachia

is classified into northern, southern, and central regions. Historically, communities in

Appalachia have lagged behind the rest of the country and Central Appalachia is

poorest performing of the three regions (Bauman, 2006; Stephens and Partridge, 2011).

Fifty four counties in Kentucky are classified as Appalachian (see exhibit 1). The

easternmostof these are well known for their high levels of economic distress,

unemployment and poverty (Heflin & Miller, 2012; Tickamyer & Tickamyer, 1988; Ziliak,

2015). Coal has been the major industry in the area for over one hundred years. Howev

the coal industry has experienced many booms and busts over the decades.

The instability of coal demand and the lack of industry diversification have contributed to

the depressed economy of the region (Black, McKinnish, & Sanders, 2005; Epstein et al.,

2011). In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson famously declared his “War on Poverty” from

a home in Eastern Kentucky’sMartin County (Lowrey, 2014; Torstensson,2013).

Although Central Appalachia is one of the poorest regions in the country, it is not from a

lack of monetary infusion from state and federal agencies. In fact, over the past

decades Eastern Kentucky has received over 9 billion dollars in financial aid and remains

behind in economic development, educational attainment, wages, employment level

and standard of living (Baumann, 2006; Gebremariam et al., 2012; Hansen & Yukhin,

1970; Jung, Cho, & Roberts, 2015; Santopietro, 2002).

Small Business Institute® Journal – Vol. 13, No. 2, #-##

Snow and Prater Pg. 3

Exhibit 1

Because of the perceived lack of opportunity for each younger generation as it reaches

early adulthood, and the factual conditions of a poorer performing economy, Easte

Kentucky has and continues to see an outward migration (Green, 2015; Hansen & Yukhin

1970; Lichter et al., 2005; Pugel, 2016; Sanders, 1969). From the period between 2010

and 2015, some counties in Kentucky have seen an increase in population as high as 8%.

However, some counties in Eastern Kentucky have seen declines higher than 6% with

many of the counties in the 4-5% range (US Census Bureau, 2015). As a means

reversing this trend and improving the future prospects of this region, it is proposed a

committed effort to entrepreneurship education at all levels needs to occur.

Given that Eastern Kentucky does not have a thriving entrepreneurial ecosystem, there

are a couple possibilities offered as explanations. One reason may be residents of this

region are not inherently or educated to be entrepreneurial. Entrepreneurship education

is not mandated by the Kentucky Department of Education. Also, this region does not

have any active chapters of Junior Achievement or the Young Entrepreneurs Academy,

which are available elsewhere in the state. One reason may be entrepreneurial intention

do exist in these citizens. However, those possessing the wherewithal choose to move to

more prosperous communities. Therefore, the purpose of this exploratory research is to

(A) measure the enterprising tendency of high school seniors to see if they curre

possess the mindset to be entrepreneurial, and (B) determine what proportion of these

adolescents plan to move away from Eastern Kentucky.

Methodology

The instrument used for this research was the GET2Test created by Sally Caird (Caird,

2013). This is a revision of the original GET Test created to measure enterprising tenden

(Caird, 1991). This instrument is well known and has been used by other researc

(Caird, 1991; Ishiguro, 2014; Katundu & Gabagambi, 2014; Mayer et al., 2014; Mazzarol

2007; Pizarro, 2014; Sethu, 2012). This instrument reliability (Cronbach α = .7)

sufficient for the purposes of this study. The survey examines five characteristics shown

to be important qualities for entrepreneurs: need for achievement, creative tenden

calculated risk taking, locus of control, and need for autonomy (Caird, 1991). The GET2

Test includes 54 items. The need for achievement, creative tendency, calculated r

taking, and locus of control are measured by 12 items each. The need for autonomy is

Snow and Prater Pg. 3

Exhibit 1

Because of the perceived lack of opportunity for each younger generation as it reaches

early adulthood, and the factual conditions of a poorer performing economy, Easte

Kentucky has and continues to see an outward migration (Green, 2015; Hansen & Yukhin

1970; Lichter et al., 2005; Pugel, 2016; Sanders, 1969). From the period between 2010

and 2015, some counties in Kentucky have seen an increase in population as high as 8%.

However, some counties in Eastern Kentucky have seen declines higher than 6% with

many of the counties in the 4-5% range (US Census Bureau, 2015). As a means

reversing this trend and improving the future prospects of this region, it is proposed a

committed effort to entrepreneurship education at all levels needs to occur.

Given that Eastern Kentucky does not have a thriving entrepreneurial ecosystem, there

are a couple possibilities offered as explanations. One reason may be residents of this

region are not inherently or educated to be entrepreneurial. Entrepreneurship education

is not mandated by the Kentucky Department of Education. Also, this region does not

have any active chapters of Junior Achievement or the Young Entrepreneurs Academy,

which are available elsewhere in the state. One reason may be entrepreneurial intention

do exist in these citizens. However, those possessing the wherewithal choose to move to

more prosperous communities. Therefore, the purpose of this exploratory research is to

(A) measure the enterprising tendency of high school seniors to see if they curre

possess the mindset to be entrepreneurial, and (B) determine what proportion of these

adolescents plan to move away from Eastern Kentucky.

Methodology

The instrument used for this research was the GET2Test created by Sally Caird (Caird,

2013). This is a revision of the original GET Test created to measure enterprising tenden

(Caird, 1991). This instrument is well known and has been used by other researc

(Caird, 1991; Ishiguro, 2014; Katundu & Gabagambi, 2014; Mayer et al., 2014; Mazzarol

2007; Pizarro, 2014; Sethu, 2012). This instrument reliability (Cronbach α = .7)

sufficient for the purposes of this study. The survey examines five characteristics shown

to be important qualities for entrepreneurs: need for achievement, creative tenden

calculated risk taking, locus of control, and need for autonomy (Caird, 1991). The GET2

Test includes 54 items. The need for achievement, creative tendency, calculated r

taking, and locus of control are measured by 12 items each. The need for autonomy is

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Small Business Institute® Journal – Vol. 13, No. 2, 1-14

Snow and Prater Pg. 4

measured by 6 items. Half of these items represent positive entrepreneurial statements,

and the rest of them represent negative entrepreneurial statements (Ishiguro, 2014).

The survey was administered to 287 seniors attending Eastern Kentucky high schools.

The survey was administered in four Eastern Kentucky high schools from four separate

counties. This was done to acquire a sample more representative of the region and not

one specific school in one particular county. The method used may be considere

convenience sampling. At the time this research was conducted an attempt was made to

elicit participation from additional schools to generate a larger sample size. However, th

four high schools were the only ones immediately available to participate.

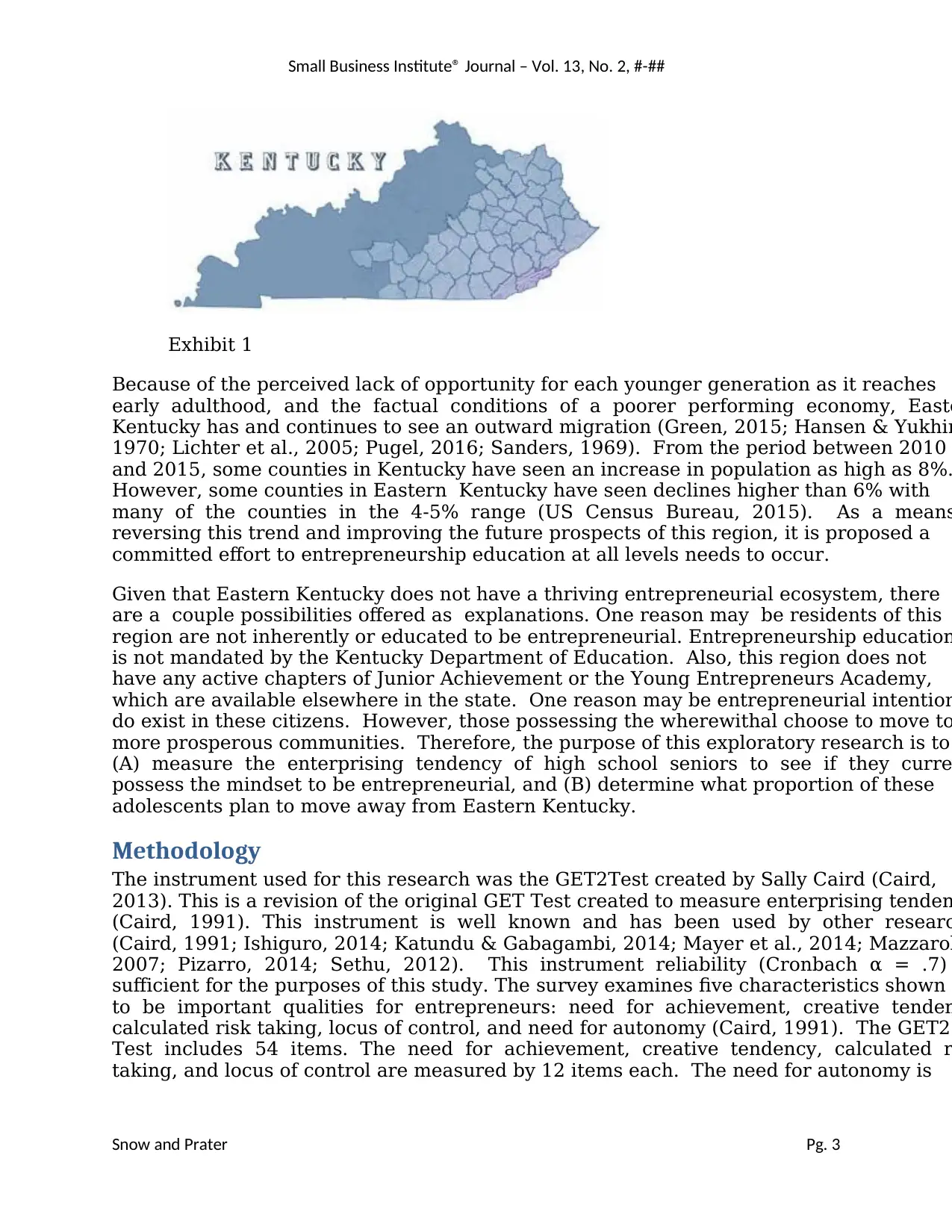

A generalization may be made that rural high schools are poorer performing than urban

or suburban high schools. However, the four schools in this study rank favorably in the

state of Kentucky (see table 1) ranging from the 77th percentile to the 97th percentile. Fifty

four surveys were eliminated from analysis because they were not completed in full. The

remaining 233 surveys were analyzed. Demographic data was collected to make

connection between student’s enterprising tendency levels and their preferences to begin

employment and/or seek a college education. Questions asked if students planned

attend college immediately after high school, planned to seek employment immediately

after high school, and if they planned to pursue these activities outside of eastern

Kentucky.

Table 1: 2014-2015 Rankings

Results

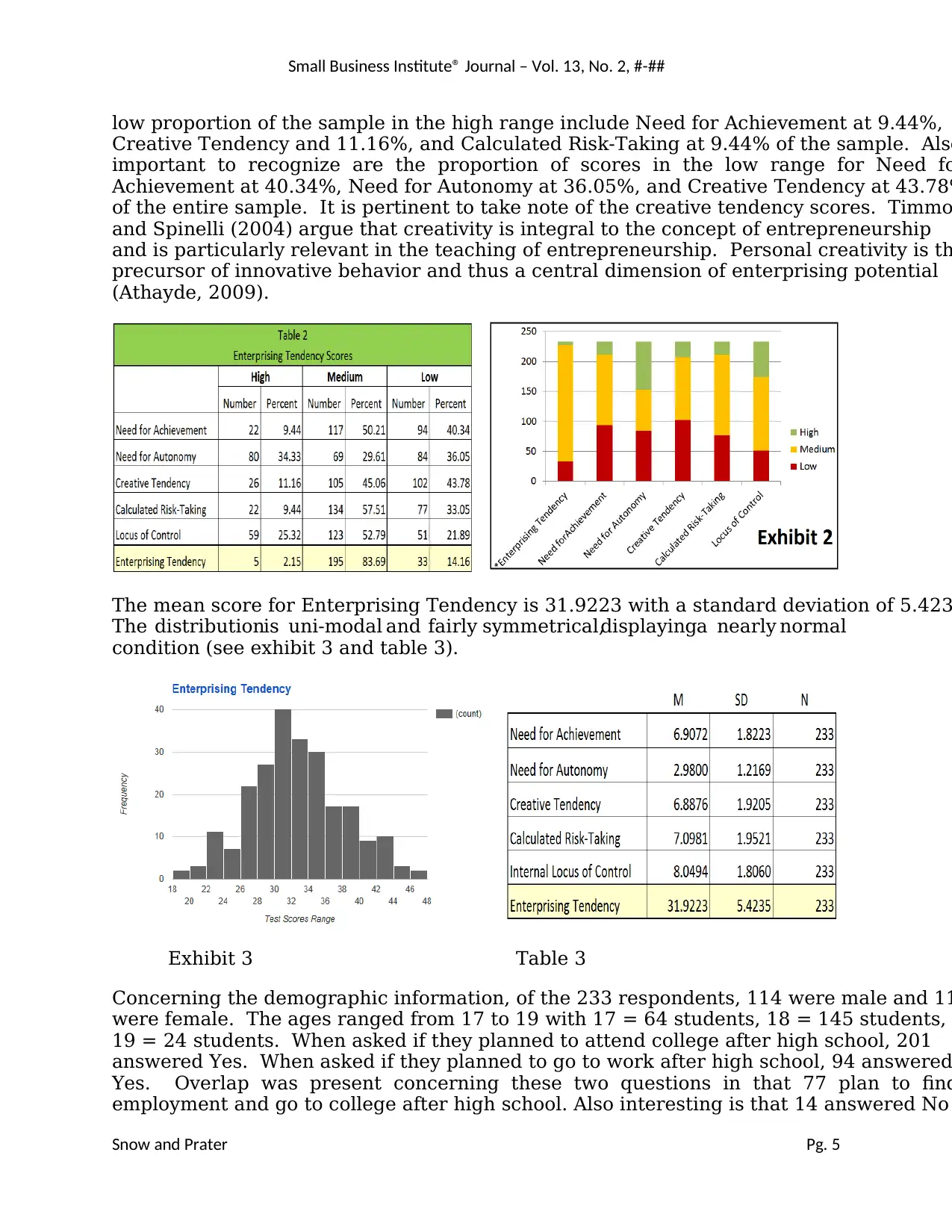

Measurements for each of the five criteria and for the composite score of enterprising

tendency are classified into three levels: low, medium, or high, based upon survey scorin

For the measure of enterprising tendency, scores from 44-54 are high (very enterprising)

27-43 medium (somewhat enterprising), and 0-26 low (likely prefer guidance from

superiors). For the individual characteristicsof Need for Achievement,Creative

Tendency, Calculated-Risk Taking, and Locus of Control, the maximum score is 12 with

10-12 the high range and 0-6 the low range. For Need for Autonomy, the maximum score

is 6 with the high range 4-6 and 0-2 the low range. Table 2 and Exhibit 2 display the

results of the students.

As you can see, only 5 of the 233 respondents scored in the high range for enterprising

tendency. This equates to only 2.15% of the entire sample. Other noteworthy scores of

Snow and Prater Pg. 4

measured by 6 items. Half of these items represent positive entrepreneurial statements,

and the rest of them represent negative entrepreneurial statements (Ishiguro, 2014).

The survey was administered to 287 seniors attending Eastern Kentucky high schools.

The survey was administered in four Eastern Kentucky high schools from four separate

counties. This was done to acquire a sample more representative of the region and not

one specific school in one particular county. The method used may be considere

convenience sampling. At the time this research was conducted an attempt was made to

elicit participation from additional schools to generate a larger sample size. However, th

four high schools were the only ones immediately available to participate.

A generalization may be made that rural high schools are poorer performing than urban

or suburban high schools. However, the four schools in this study rank favorably in the

state of Kentucky (see table 1) ranging from the 77th percentile to the 97th percentile. Fifty

four surveys were eliminated from analysis because they were not completed in full. The

remaining 233 surveys were analyzed. Demographic data was collected to make

connection between student’s enterprising tendency levels and their preferences to begin

employment and/or seek a college education. Questions asked if students planned

attend college immediately after high school, planned to seek employment immediately

after high school, and if they planned to pursue these activities outside of eastern

Kentucky.

Table 1: 2014-2015 Rankings

Results

Measurements for each of the five criteria and for the composite score of enterprising

tendency are classified into three levels: low, medium, or high, based upon survey scorin

For the measure of enterprising tendency, scores from 44-54 are high (very enterprising)

27-43 medium (somewhat enterprising), and 0-26 low (likely prefer guidance from

superiors). For the individual characteristicsof Need for Achievement,Creative

Tendency, Calculated-Risk Taking, and Locus of Control, the maximum score is 12 with

10-12 the high range and 0-6 the low range. For Need for Autonomy, the maximum score

is 6 with the high range 4-6 and 0-2 the low range. Table 2 and Exhibit 2 display the

results of the students.

As you can see, only 5 of the 233 respondents scored in the high range for enterprising

tendency. This equates to only 2.15% of the entire sample. Other noteworthy scores of

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Small Business Institute® Journal – Vol. 13, No. 2, #-##

Snow and Prater Pg. 5

low proportion of the sample in the high range include Need for Achievement at 9.44%,

Creative Tendency and 11.16%, and Calculated Risk-Taking at 9.44% of the sample. Also

important to recognize are the proportion of scores in the low range for Need fo

Achievement at 40.34%, Need for Autonomy at 36.05%, and Creative Tendency at 43.78%

of the entire sample. It is pertinent to take note of the creative tendency scores. Timmo

and Spinelli (2004) argue that creativity is integral to the concept of entrepreneurship

and is particularly relevant in the teaching of entrepreneurship. Personal creativity is th

precursor of innovative behavior and thus a central dimension of enterprising potential

(Athayde, 2009).

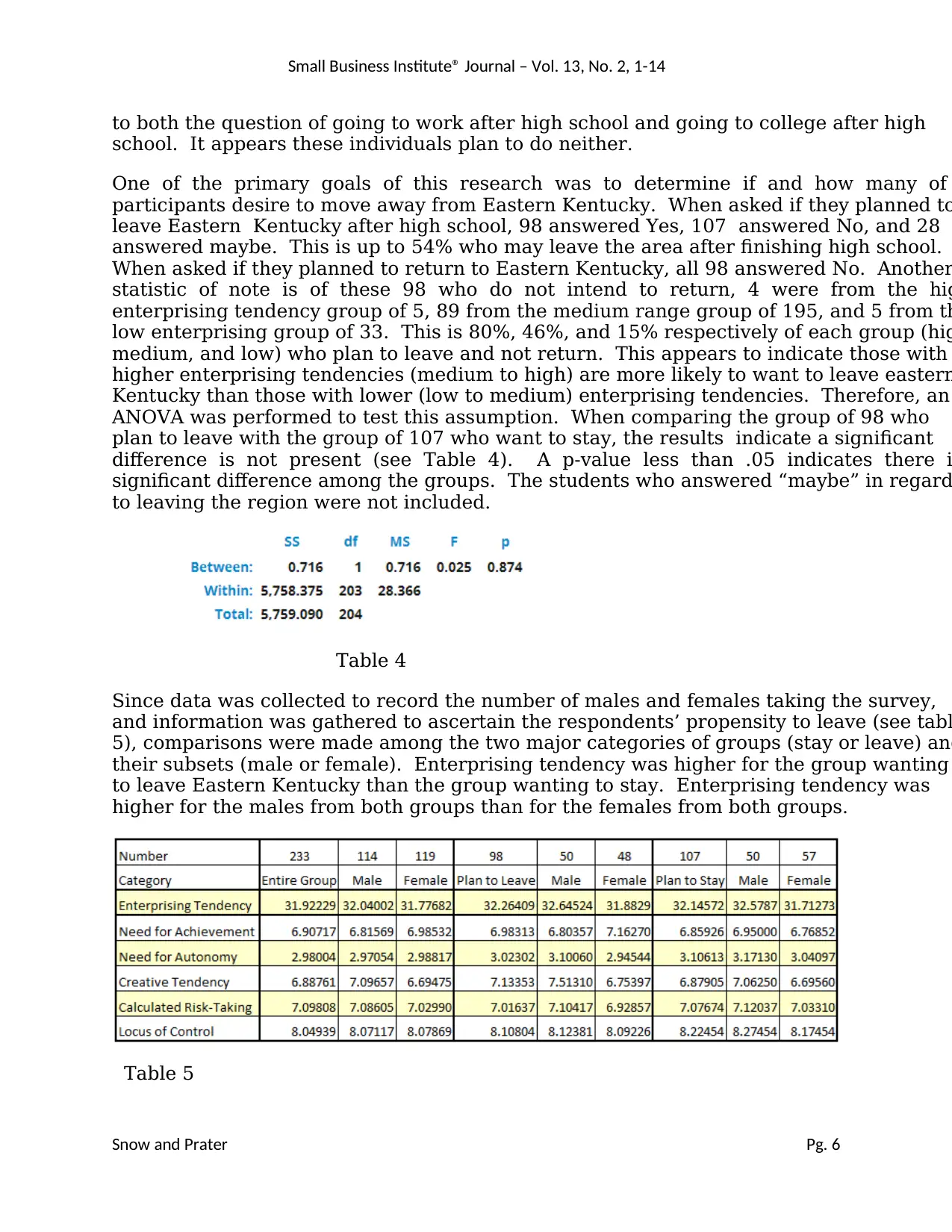

The mean score for Enterprising Tendency is 31.9223 with a standard deviation of 5.423

The distributionis uni-modal and fairly symmetrical,displayinga nearly normal

condition (see exhibit 3 and table 3).

Exhibit 3 Table 3

Concerning the demographic information, of the 233 respondents, 114 were male and 11

were female. The ages ranged from 17 to 19 with 17 = 64 students, 18 = 145 students,

19 = 24 students. When asked if they planned to attend college after high school, 201

answered Yes. When asked if they planned to go to work after high school, 94 answered

Yes. Overlap was present concerning these two questions in that 77 plan to find

employment and go to college after high school. Also interesting is that 14 answered No

Snow and Prater Pg. 5

low proportion of the sample in the high range include Need for Achievement at 9.44%,

Creative Tendency and 11.16%, and Calculated Risk-Taking at 9.44% of the sample. Also

important to recognize are the proportion of scores in the low range for Need fo

Achievement at 40.34%, Need for Autonomy at 36.05%, and Creative Tendency at 43.78%

of the entire sample. It is pertinent to take note of the creative tendency scores. Timmo

and Spinelli (2004) argue that creativity is integral to the concept of entrepreneurship

and is particularly relevant in the teaching of entrepreneurship. Personal creativity is th

precursor of innovative behavior and thus a central dimension of enterprising potential

(Athayde, 2009).

The mean score for Enterprising Tendency is 31.9223 with a standard deviation of 5.423

The distributionis uni-modal and fairly symmetrical,displayinga nearly normal

condition (see exhibit 3 and table 3).

Exhibit 3 Table 3

Concerning the demographic information, of the 233 respondents, 114 were male and 11

were female. The ages ranged from 17 to 19 with 17 = 64 students, 18 = 145 students,

19 = 24 students. When asked if they planned to attend college after high school, 201

answered Yes. When asked if they planned to go to work after high school, 94 answered

Yes. Overlap was present concerning these two questions in that 77 plan to find

employment and go to college after high school. Also interesting is that 14 answered No

Small Business Institute® Journal – Vol. 13, No. 2, 1-14

Snow and Prater Pg. 6

to both the question of going to work after high school and going to college after high

school. It appears these individuals plan to do neither.

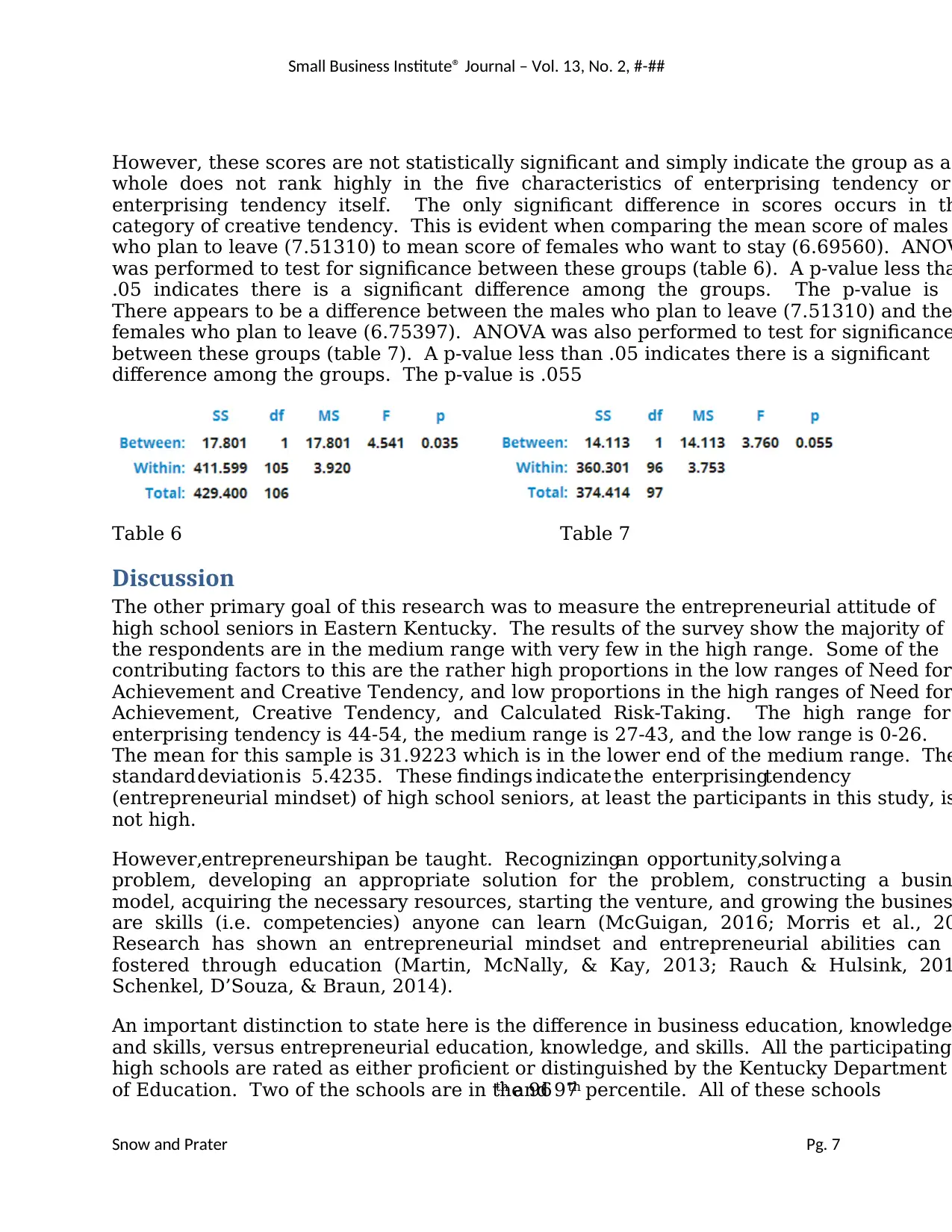

One of the primary goals of this research was to determine if and how many of

participants desire to move away from Eastern Kentucky. When asked if they planned to

leave Eastern Kentucky after high school, 98 answered Yes, 107 answered No, and 28

answered maybe. This is up to 54% who may leave the area after finishing high school.

When asked if they planned to return to Eastern Kentucky, all 98 answered No. Another

statistic of note is of these 98 who do not intend to return, 4 were from the hig

enterprising tendency group of 5, 89 from the medium range group of 195, and 5 from th

low enterprising group of 33. This is 80%, 46%, and 15% respectively of each group (hig

medium, and low) who plan to leave and not return. This appears to indicate those with

higher enterprising tendencies (medium to high) are more likely to want to leave eastern

Kentucky than those with lower (low to medium) enterprising tendencies. Therefore, an

ANOVA was performed to test this assumption. When comparing the group of 98 who

plan to leave with the group of 107 who want to stay, the results indicate a significant

difference is not present (see Table 4). A p-value less than .05 indicates there i

significant difference among the groups. The students who answered “maybe” in regard

to leaving the region were not included.

Table 4

Since data was collected to record the number of males and females taking the survey,

and information was gathered to ascertain the respondents’ propensity to leave (see tabl

5), comparisons were made among the two major categories of groups (stay or leave) and

their subsets (male or female). Enterprising tendency was higher for the group wanting

to leave Eastern Kentucky than the group wanting to stay. Enterprising tendency was

higher for the males from both groups than for the females from both groups.

Table 5

Snow and Prater Pg. 6

to both the question of going to work after high school and going to college after high

school. It appears these individuals plan to do neither.

One of the primary goals of this research was to determine if and how many of

participants desire to move away from Eastern Kentucky. When asked if they planned to

leave Eastern Kentucky after high school, 98 answered Yes, 107 answered No, and 28

answered maybe. This is up to 54% who may leave the area after finishing high school.

When asked if they planned to return to Eastern Kentucky, all 98 answered No. Another

statistic of note is of these 98 who do not intend to return, 4 were from the hig

enterprising tendency group of 5, 89 from the medium range group of 195, and 5 from th

low enterprising group of 33. This is 80%, 46%, and 15% respectively of each group (hig

medium, and low) who plan to leave and not return. This appears to indicate those with

higher enterprising tendencies (medium to high) are more likely to want to leave eastern

Kentucky than those with lower (low to medium) enterprising tendencies. Therefore, an

ANOVA was performed to test this assumption. When comparing the group of 98 who

plan to leave with the group of 107 who want to stay, the results indicate a significant

difference is not present (see Table 4). A p-value less than .05 indicates there i

significant difference among the groups. The students who answered “maybe” in regard

to leaving the region were not included.

Table 4

Since data was collected to record the number of males and females taking the survey,

and information was gathered to ascertain the respondents’ propensity to leave (see tabl

5), comparisons were made among the two major categories of groups (stay or leave) and

their subsets (male or female). Enterprising tendency was higher for the group wanting

to leave Eastern Kentucky than the group wanting to stay. Enterprising tendency was

higher for the males from both groups than for the females from both groups.

Table 5

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Small Business Institute® Journal – Vol. 13, No. 2, #-##

Snow and Prater Pg. 7

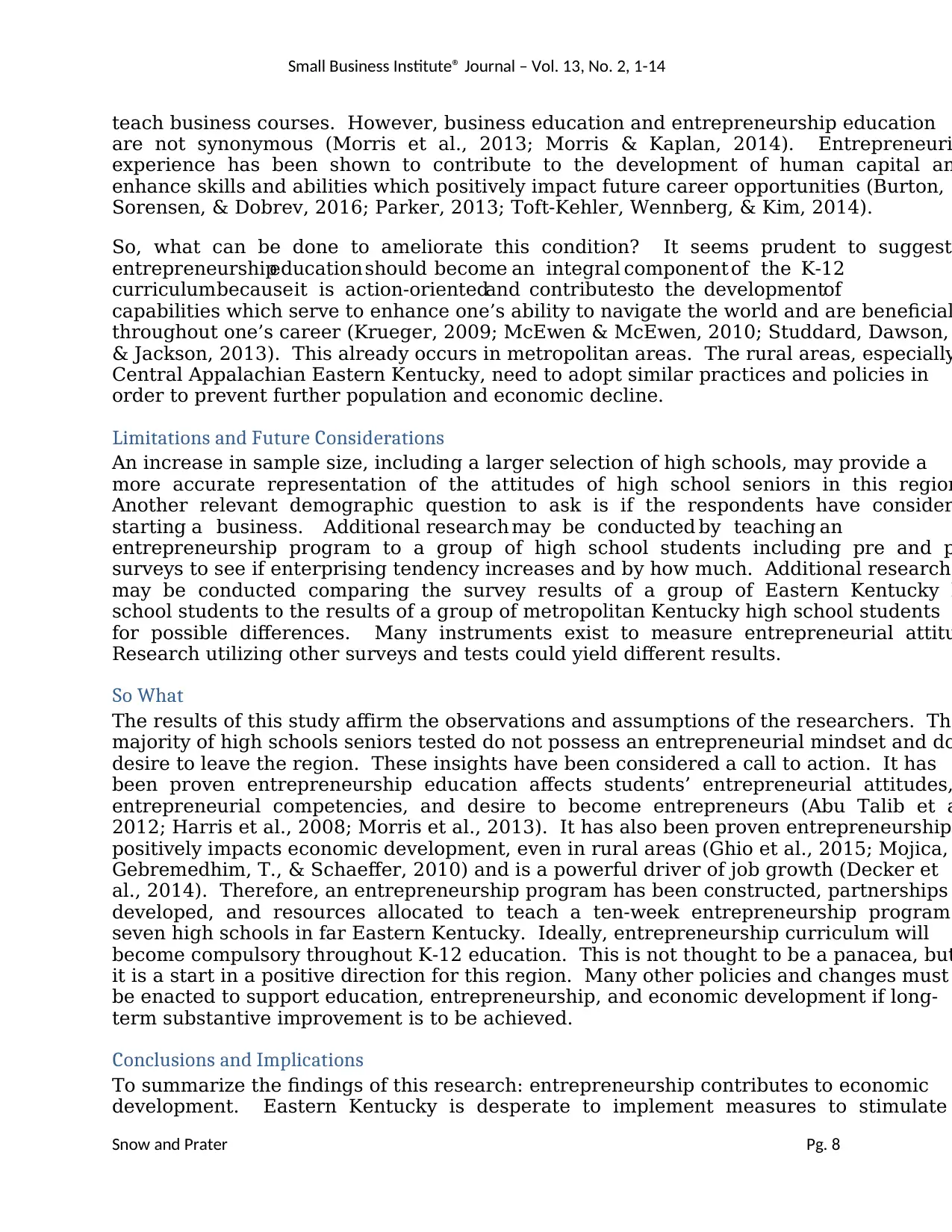

However, these scores are not statistically significant and simply indicate the group as a

whole does not rank highly in the five characteristics of enterprising tendency or

enterprising tendency itself. The only significant difference in scores occurs in th

category of creative tendency. This is evident when comparing the mean score of males

who plan to leave (7.51310) to mean score of females who want to stay (6.69560). ANOV

was performed to test for significance between these groups (table 6). A p-value less tha

.05 indicates there is a significant difference among the groups. The p-value is .

There appears to be a difference between the males who plan to leave (7.51310) and the

females who plan to leave (6.75397). ANOVA was also performed to test for significance

between these groups (table 7). A p-value less than .05 indicates there is a significant

difference among the groups. The p-value is .055

Table 6 Table 7

Discussion

The other primary goal of this research was to measure the entrepreneurial attitude of

high school seniors in Eastern Kentucky. The results of the survey show the majority of

the respondents are in the medium range with very few in the high range. Some of the

contributing factors to this are the rather high proportions in the low ranges of Need for

Achievement and Creative Tendency, and low proportions in the high ranges of Need for

Achievement, Creative Tendency, and Calculated Risk-Taking. The high range for

enterprising tendency is 44-54, the medium range is 27-43, and the low range is 0-26.

The mean for this sample is 31.9223 which is in the lower end of the medium range. The

standard deviation is 5.4235. These findings indicate the enterprisingtendency

(entrepreneurial mindset) of high school seniors, at least the participants in this study, is

not high.

However,entrepreneurshipcan be taught. Recognizingan opportunity,solving a

problem, developing an appropriate solution for the problem, constructing a busin

model, acquiring the necessary resources, starting the venture, and growing the busines

are skills (i.e. competencies) anyone can learn (McGuigan, 2016; Morris et al., 20

Research has shown an entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurial abilities can

fostered through education (Martin, McNally, & Kay, 2013; Rauch & Hulsink, 201

Schenkel, D’Souza, & Braun, 2014).

An important distinction to state here is the difference in business education, knowledge

and skills, versus entrepreneurial education, knowledge, and skills. All the participating

high schools are rated as either proficient or distinguished by the Kentucky Department

of Education. Two of the schools are in the 96th and 97th percentile. All of these schools

Snow and Prater Pg. 7

However, these scores are not statistically significant and simply indicate the group as a

whole does not rank highly in the five characteristics of enterprising tendency or

enterprising tendency itself. The only significant difference in scores occurs in th

category of creative tendency. This is evident when comparing the mean score of males

who plan to leave (7.51310) to mean score of females who want to stay (6.69560). ANOV

was performed to test for significance between these groups (table 6). A p-value less tha

.05 indicates there is a significant difference among the groups. The p-value is .

There appears to be a difference between the males who plan to leave (7.51310) and the

females who plan to leave (6.75397). ANOVA was also performed to test for significance

between these groups (table 7). A p-value less than .05 indicates there is a significant

difference among the groups. The p-value is .055

Table 6 Table 7

Discussion

The other primary goal of this research was to measure the entrepreneurial attitude of

high school seniors in Eastern Kentucky. The results of the survey show the majority of

the respondents are in the medium range with very few in the high range. Some of the

contributing factors to this are the rather high proportions in the low ranges of Need for

Achievement and Creative Tendency, and low proportions in the high ranges of Need for

Achievement, Creative Tendency, and Calculated Risk-Taking. The high range for

enterprising tendency is 44-54, the medium range is 27-43, and the low range is 0-26.

The mean for this sample is 31.9223 which is in the lower end of the medium range. The

standard deviation is 5.4235. These findings indicate the enterprisingtendency

(entrepreneurial mindset) of high school seniors, at least the participants in this study, is

not high.

However,entrepreneurshipcan be taught. Recognizingan opportunity,solving a

problem, developing an appropriate solution for the problem, constructing a busin

model, acquiring the necessary resources, starting the venture, and growing the busines

are skills (i.e. competencies) anyone can learn (McGuigan, 2016; Morris et al., 20

Research has shown an entrepreneurial mindset and entrepreneurial abilities can

fostered through education (Martin, McNally, & Kay, 2013; Rauch & Hulsink, 201

Schenkel, D’Souza, & Braun, 2014).

An important distinction to state here is the difference in business education, knowledge

and skills, versus entrepreneurial education, knowledge, and skills. All the participating

high schools are rated as either proficient or distinguished by the Kentucky Department

of Education. Two of the schools are in the 96th and 97th percentile. All of these schools

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Small Business Institute® Journal – Vol. 13, No. 2, 1-14

Snow and Prater Pg. 8

teach business courses. However, business education and entrepreneurship education

are not synonymous (Morris et al., 2013; Morris & Kaplan, 2014). Entrepreneuri

experience has been shown to contribute to the development of human capital an

enhance skills and abilities which positively impact future career opportunities (Burton,

Sorensen, & Dobrev, 2016; Parker, 2013; Toft-Kehler, Wennberg, & Kim, 2014).

So, what can be done to ameliorate this condition? It seems prudent to suggest

entrepreneurshipeducation should become an integral component of the K-12

curriculumbecause it is action-orientedand contributesto the developmentof

capabilities which serve to enhance one’s ability to navigate the world and are beneficial

throughout one’s career (Krueger, 2009; McEwen & McEwen, 2010; Studdard, Dawson,

& Jackson, 2013). This already occurs in metropolitan areas. The rural areas, especially

Central Appalachian Eastern Kentucky, need to adopt similar practices and policies in

order to prevent further population and economic decline.

Limitations and Future Considerations

An increase in sample size, including a larger selection of high schools, may provide a

more accurate representation of the attitudes of high school seniors in this region

Another relevant demographic question to ask is if the respondents have consider

starting a business. Additional research may be conducted by teaching an

entrepreneurship program to a group of high school students including pre and p

surveys to see if enterprising tendency increases and by how much. Additional research

may be conducted comparing the survey results of a group of Eastern Kentucky h

school students to the results of a group of metropolitan Kentucky high school students

for possible differences. Many instruments exist to measure entrepreneurial attitu

Research utilizing other surveys and tests could yield different results.

So What

The results of this study affirm the observations and assumptions of the researchers. The

majority of high schools seniors tested do not possess an entrepreneurial mindset and do

desire to leave the region. These insights have been considered a call to action. It has

been proven entrepreneurship education affects students’ entrepreneurial attitudes,

entrepreneurial competencies, and desire to become entrepreneurs (Abu Talib et a

2012; Harris et al., 2008; Morris et al., 2013). It has also been proven entrepreneurship

positively impacts economic development, even in rural areas (Ghio et al., 2015; Mojica,

Gebremedhim, T., & Schaeffer, 2010) and is a powerful driver of job growth (Decker et

al., 2014). Therefore, an entrepreneurship program has been constructed, partnerships

developed, and resources allocated to teach a ten-week entrepreneurship program

seven high schools in far Eastern Kentucky. Ideally, entrepreneurship curriculum will

become compulsory throughout K-12 education. This is not thought to be a panacea, but

it is a start in a positive direction for this region. Many other policies and changes must

be enacted to support education, entrepreneurship, and economic development if long-

term substantive improvement is to be achieved.

Conclusions and Implications

To summarize the findings of this research: entrepreneurship contributes to economic

development. Eastern Kentucky is desperate to implement measures to stimulate

Snow and Prater Pg. 8

teach business courses. However, business education and entrepreneurship education

are not synonymous (Morris et al., 2013; Morris & Kaplan, 2014). Entrepreneuri

experience has been shown to contribute to the development of human capital an

enhance skills and abilities which positively impact future career opportunities (Burton,

Sorensen, & Dobrev, 2016; Parker, 2013; Toft-Kehler, Wennberg, & Kim, 2014).

So, what can be done to ameliorate this condition? It seems prudent to suggest

entrepreneurshipeducation should become an integral component of the K-12

curriculumbecause it is action-orientedand contributesto the developmentof

capabilities which serve to enhance one’s ability to navigate the world and are beneficial

throughout one’s career (Krueger, 2009; McEwen & McEwen, 2010; Studdard, Dawson,

& Jackson, 2013). This already occurs in metropolitan areas. The rural areas, especially

Central Appalachian Eastern Kentucky, need to adopt similar practices and policies in

order to prevent further population and economic decline.

Limitations and Future Considerations

An increase in sample size, including a larger selection of high schools, may provide a

more accurate representation of the attitudes of high school seniors in this region

Another relevant demographic question to ask is if the respondents have consider

starting a business. Additional research may be conducted by teaching an

entrepreneurship program to a group of high school students including pre and p

surveys to see if enterprising tendency increases and by how much. Additional research

may be conducted comparing the survey results of a group of Eastern Kentucky h

school students to the results of a group of metropolitan Kentucky high school students

for possible differences. Many instruments exist to measure entrepreneurial attitu

Research utilizing other surveys and tests could yield different results.

So What

The results of this study affirm the observations and assumptions of the researchers. The

majority of high schools seniors tested do not possess an entrepreneurial mindset and do

desire to leave the region. These insights have been considered a call to action. It has

been proven entrepreneurship education affects students’ entrepreneurial attitudes,

entrepreneurial competencies, and desire to become entrepreneurs (Abu Talib et a

2012; Harris et al., 2008; Morris et al., 2013). It has also been proven entrepreneurship

positively impacts economic development, even in rural areas (Ghio et al., 2015; Mojica,

Gebremedhim, T., & Schaeffer, 2010) and is a powerful driver of job growth (Decker et

al., 2014). Therefore, an entrepreneurship program has been constructed, partnerships

developed, and resources allocated to teach a ten-week entrepreneurship program

seven high schools in far Eastern Kentucky. Ideally, entrepreneurship curriculum will

become compulsory throughout K-12 education. This is not thought to be a panacea, but

it is a start in a positive direction for this region. Many other policies and changes must

be enacted to support education, entrepreneurship, and economic development if long-

term substantive improvement is to be achieved.

Conclusions and Implications

To summarize the findings of this research: entrepreneurship contributes to economic

development. Eastern Kentucky is desperate to implement measures to stimulate

Small Business Institute® Journal – Vol. 13, No. 2, #-##

Snow and Prater Pg. 9

economic development. The region has highly ranked high schools teaching busin

courses, but they do not teach entrepreneurship. The students surveyed do not rate high

for enterprising tendency, need for achievement, creative tendency, calculated risk takin

locus of control, or need for autonomy. Entrepreneurship education is shown to positivel

impact academic success, attitude toward entrepreneurship, intention to become a

entrepreneur, business skills, and desirability by employers. It is logical to teach

entrepreneurship in Eastern Kentucky at the K-12 level as one initiative in an attempt to

improve the mindset of the youth. This will aid in the formation of an entrepreneurial

ecosystemto enhance economicdevelopmentin the region by enlighteningeach

successive generation to the possibilities of creating their own opportunities for career in

their home towns, as opposed to the continued migration of young adults to othe

communities for education, career, and contributions to society.

In conclusion, this research has provided results important to the fields of

entrepreneurship, education, and economic development as they pertain to rural areas

with traditionally non-diverse economies, similar to the conditions of Central

Appalachian Eastern Kentucky.

References

Abu Talib, M. (2012). Innovative Use of IT Applications for Teaching Entrepreneurship

to Youth: UAE Case Study. European, Mediterranean & Middle Eastern

Conference of Information Systems.

Acs, Z., & Audretsch, D. (2003). Innovation and Technological Change. Handbook of

Entrepreneurship Research: An Interdisciplinary Survey and Introduction.

Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer. 55-80.

Athayde, R. (2009). Measuring Enterprise Potential in Young People. Entrepreneurship

Theory & Practice, 33(2), 481-500.

Audretsch, D., & Link, A. (2012). Valuing an Entrepreneurial Enterprise. Small Business

Economics, 38(2), 139-145.

Audretsch, D., & Keilbach, M. (2004). Entrepreneurship Capital and Economic

Performance. Regional Studies, 38(8), 949–959.

Baumann, R. (2006). Changes in the Appalachian Wage Gap, 1970 to 2000. Growth

and Change, 37(3), 416-443.

Baumol, W. (2002). The Free-Market Innovation Machine: Analyzing the Growth

Miracle of Capitalism. Princeton. NJ: Princeton University Press.

Black, D., McKinnish, T., & Sanders, S. (2005). The Economic Impact of the Coal Boom

and Bust. Economic Journal, 115(503), 449-476.

Snow and Prater Pg. 9

economic development. The region has highly ranked high schools teaching busin

courses, but they do not teach entrepreneurship. The students surveyed do not rate high

for enterprising tendency, need for achievement, creative tendency, calculated risk takin

locus of control, or need for autonomy. Entrepreneurship education is shown to positivel

impact academic success, attitude toward entrepreneurship, intention to become a

entrepreneur, business skills, and desirability by employers. It is logical to teach

entrepreneurship in Eastern Kentucky at the K-12 level as one initiative in an attempt to

improve the mindset of the youth. This will aid in the formation of an entrepreneurial

ecosystemto enhance economicdevelopmentin the region by enlighteningeach

successive generation to the possibilities of creating their own opportunities for career in

their home towns, as opposed to the continued migration of young adults to othe

communities for education, career, and contributions to society.

In conclusion, this research has provided results important to the fields of

entrepreneurship, education, and economic development as they pertain to rural areas

with traditionally non-diverse economies, similar to the conditions of Central

Appalachian Eastern Kentucky.

References

Abu Talib, M. (2012). Innovative Use of IT Applications for Teaching Entrepreneurship

to Youth: UAE Case Study. European, Mediterranean & Middle Eastern

Conference of Information Systems.

Acs, Z., & Audretsch, D. (2003). Innovation and Technological Change. Handbook of

Entrepreneurship Research: An Interdisciplinary Survey and Introduction.

Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer. 55-80.

Athayde, R. (2009). Measuring Enterprise Potential in Young People. Entrepreneurship

Theory & Practice, 33(2), 481-500.

Audretsch, D., & Link, A. (2012). Valuing an Entrepreneurial Enterprise. Small Business

Economics, 38(2), 139-145.

Audretsch, D., & Keilbach, M. (2004). Entrepreneurship Capital and Economic

Performance. Regional Studies, 38(8), 949–959.

Baumann, R. (2006). Changes in the Appalachian Wage Gap, 1970 to 2000. Growth

and Change, 37(3), 416-443.

Baumol, W. (2002). The Free-Market Innovation Machine: Analyzing the Growth

Miracle of Capitalism. Princeton. NJ: Princeton University Press.

Black, D., McKinnish, T., & Sanders, S. (2005). The Economic Impact of the Coal Boom

and Bust. Economic Journal, 115(503), 449-476.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Small Business Institute® Journal – Vol. 13, No. 2, 1-14

Snow and Prater Pg. 10

Brown, K., Bowlus, D., & Seibert, S. (2011). Online Entrepreneurship Curriculum for

High School Students: Impact on Knowledge, Self-Efficacy, and Attitudes.

USASBE Proceedings, 1351-1364.

Burton, D., Sorensen, J., Dobrev, S. (2016). A Careers Perspective on Entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(2) 237-247.

Caird, S. (2013). General Measure of Enterprising Tendency Test. The Open University’s

Repository of Research Publications and Other Research Outputs. Retrieved from

http://oro.open.ac.uk/5393/2/Get2test_guide.pdf

Caird, S. (1991). Testing Enterprising Tendency in Occupational Groups. British Journal

of Mangement, 2, 177-186.

Clayton, R., Sadeghi, A., Spletzer, J. & Talan, D. (2013). High-Employment-Growth

Firms: Defining and Counting Them. Monthly Labor Review, 136(6), 3-13.

Decker, R., Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R. & Miranda, J. (2014). The Role of

Entrepreneurship in US Job Creation and Economic Dynamism. Journal of

Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 3-24.

Duval-Couetil, N. (2013). Assessing the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education

Programs: Challenges and Approaches. Journal of Small Business Management,

51(3), 394-409.

Epstein, P., Buonocore, J., Eckerle, K., Hendryx, M., Iii, B., Heinberg, R., Glustrom, L.

(2011). Full Cost Accounting for the Life Cycle of Coal. Annals of the New York

Academy of Sciences, 73-98.

Frazier, A. (2014). YEA! For Entrepreneurship. Business NH, 31(11) 10-11.

Gebremariam, G., Gebremeskel, H., Gebremedhin, T., Schaeffer, P., Phipps, T. &

Jackson, R. (2012). Employment, Income, Migration and Public Services: A

Simultaneous Spatial Panel Data Model of Regional Growth. Papers in Regional

Science, 91(2), 275-297.

Ghio, N., Guerini, M., Lehmann, E & Rossi-Lamstra, C. (2015). The Emergence of the

Knowledge Spillover Theory of Entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics,

44(1), 1-18.

Green, M. (2015, July8). More Than Half of Kentucky’s Counties Losing Population,

Census Data Shows. http://www.wdrb.com/story/29503122/more-than-half-of-

kentuckys-counties-losing-population-census-data-shows

Hamilton, S., Hamilton, M. (2012). Development in Youth Enterprises. New Directions

for Youth Development, 134, 65-75.

Snow and Prater Pg. 10

Brown, K., Bowlus, D., & Seibert, S. (2011). Online Entrepreneurship Curriculum for

High School Students: Impact on Knowledge, Self-Efficacy, and Attitudes.

USASBE Proceedings, 1351-1364.

Burton, D., Sorensen, J., Dobrev, S. (2016). A Careers Perspective on Entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(2) 237-247.

Caird, S. (2013). General Measure of Enterprising Tendency Test. The Open University’s

Repository of Research Publications and Other Research Outputs. Retrieved from

http://oro.open.ac.uk/5393/2/Get2test_guide.pdf

Caird, S. (1991). Testing Enterprising Tendency in Occupational Groups. British Journal

of Mangement, 2, 177-186.

Clayton, R., Sadeghi, A., Spletzer, J. & Talan, D. (2013). High-Employment-Growth

Firms: Defining and Counting Them. Monthly Labor Review, 136(6), 3-13.

Decker, R., Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R. & Miranda, J. (2014). The Role of

Entrepreneurship in US Job Creation and Economic Dynamism. Journal of

Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 3-24.

Duval-Couetil, N. (2013). Assessing the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education

Programs: Challenges and Approaches. Journal of Small Business Management,

51(3), 394-409.

Epstein, P., Buonocore, J., Eckerle, K., Hendryx, M., Iii, B., Heinberg, R., Glustrom, L.

(2011). Full Cost Accounting for the Life Cycle of Coal. Annals of the New York

Academy of Sciences, 73-98.

Frazier, A. (2014). YEA! For Entrepreneurship. Business NH, 31(11) 10-11.

Gebremariam, G., Gebremeskel, H., Gebremedhin, T., Schaeffer, P., Phipps, T. &

Jackson, R. (2012). Employment, Income, Migration and Public Services: A

Simultaneous Spatial Panel Data Model of Regional Growth. Papers in Regional

Science, 91(2), 275-297.

Ghio, N., Guerini, M., Lehmann, E & Rossi-Lamstra, C. (2015). The Emergence of the

Knowledge Spillover Theory of Entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics,

44(1), 1-18.

Green, M. (2015, July8). More Than Half of Kentucky’s Counties Losing Population,

Census Data Shows. http://www.wdrb.com/story/29503122/more-than-half-of-

kentuckys-counties-losing-population-census-data-shows

Hamilton, S., Hamilton, M. (2012). Development in Youth Enterprises. New Directions

for Youth Development, 134, 65-75.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Small Business Institute® Journal – Vol. 13, No. 2, #-##

Snow and Prater Pg. 11

Hansen, N. & Yukhin, R. (1970). Locational Preferences and Opportunity Costs in a

Lagging Region: A Study of High School Seniors in Eastern Kentucky. Journal of

Human Resources, 5(3), 341-353.

Harris, M., Gibson, S., Taylor, S., & Mick, T. (2008). Examining the Entrepreneurial

Attitudes of Business Students: The Impact of Participation in the Small Business

Institute®. USASBE Proceedings, 1471-1481.

Heflin, C. & Miller, K. (2012). The Geography of Need: Identifying Human Service

Needs in Rural America. Journal of Family Social Work, 15(5), 359-374.

Hernandez, S. & Newman, C. (2009). Positive Long-Term Impact of Minding Our

Business Entrepreneurship Programs for Low-Income Middle School Students.

Hessels, J., & van Stel, A. (2011). Entrepreneurship, export orientation, and economic

growth. Small Business Economics, 37(2), 255-268.

Ishiguro, J. (2014). What Influences Entrepreneurial Career Choice?: An Exploratory

Analysis of the Sally Caird’s GET2 for Japanese High School Students. Allied

Academies International Conference: Proceedings of the Academy of

Entrepreneurship, 20(1), 9-13.

Jaafar, M., Dahalan, N., & Rosdi, S. (2014). Local Community Entrepreneurship: A Case

Study of the Lenggong Valley. Asian Social Science, 10(10), 226-235.

Jung, S., Cho, S., & Roberts, R. (2015). The Impact of Government Funding of Poverty

Reduction Programmes. Papers in Regional Science, 94(3), 653-675.

Katundu, M. & Gabagambi, D. (2014). Entrepreneurial Tendencies of Tanzanian

University Graduates: Evidence from University of Dar-es-Salaam. European

Academic Research, 1(12), 5525-5558.

Krueger, N. (2009). The Microfoundations of Entrepreneurial Learning

and….Education: The Experiential Essence of Entrepreneurial Education. In

Page, G., Gatewood, L. & Shaver, G. University-Wide Entrepreneurship

Education (35-59). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Kuratko, D. (2014). Entrepreneurship: Theory, Process, Practice. 9th ed. Mason, OH:

Cengage/South-Western Publishers.

Lee, S., Chang, D., & Lim, S. (2005). Impact of Entreprenuerial Education: A

Comprative Study of the U.S. and Korea. International Entrepreneurship and

Management Journal, 1(1), 27-43.

Lichter, D., Garrat, J., Marshall, M., & Cardella, M. (2005). Emerging Patterns of

Population Redistribution and Migration in Appalachia. Washington DC:

Appalachian Regional Commission.

Snow and Prater Pg. 11

Hansen, N. & Yukhin, R. (1970). Locational Preferences and Opportunity Costs in a

Lagging Region: A Study of High School Seniors in Eastern Kentucky. Journal of

Human Resources, 5(3), 341-353.

Harris, M., Gibson, S., Taylor, S., & Mick, T. (2008). Examining the Entrepreneurial

Attitudes of Business Students: The Impact of Participation in the Small Business

Institute®. USASBE Proceedings, 1471-1481.

Heflin, C. & Miller, K. (2012). The Geography of Need: Identifying Human Service

Needs in Rural America. Journal of Family Social Work, 15(5), 359-374.

Hernandez, S. & Newman, C. (2009). Positive Long-Term Impact of Minding Our

Business Entrepreneurship Programs for Low-Income Middle School Students.

Hessels, J., & van Stel, A. (2011). Entrepreneurship, export orientation, and economic

growth. Small Business Economics, 37(2), 255-268.

Ishiguro, J. (2014). What Influences Entrepreneurial Career Choice?: An Exploratory

Analysis of the Sally Caird’s GET2 for Japanese High School Students. Allied

Academies International Conference: Proceedings of the Academy of

Entrepreneurship, 20(1), 9-13.

Jaafar, M., Dahalan, N., & Rosdi, S. (2014). Local Community Entrepreneurship: A Case

Study of the Lenggong Valley. Asian Social Science, 10(10), 226-235.

Jung, S., Cho, S., & Roberts, R. (2015). The Impact of Government Funding of Poverty

Reduction Programmes. Papers in Regional Science, 94(3), 653-675.

Katundu, M. & Gabagambi, D. (2014). Entrepreneurial Tendencies of Tanzanian

University Graduates: Evidence from University of Dar-es-Salaam. European

Academic Research, 1(12), 5525-5558.

Krueger, N. (2009). The Microfoundations of Entrepreneurial Learning

and….Education: The Experiential Essence of Entrepreneurial Education. In

Page, G., Gatewood, L. & Shaver, G. University-Wide Entrepreneurship

Education (35-59). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Kuratko, D. (2014). Entrepreneurship: Theory, Process, Practice. 9th ed. Mason, OH:

Cengage/South-Western Publishers.

Lee, S., Chang, D., & Lim, S. (2005). Impact of Entreprenuerial Education: A

Comprative Study of the U.S. and Korea. International Entrepreneurship and

Management Journal, 1(1), 27-43.

Lichter, D., Garrat, J., Marshall, M., & Cardella, M. (2005). Emerging Patterns of

Population Redistribution and Migration in Appalachia. Washington DC:

Appalachian Regional Commission.

Small Business Institute® Journal – Vol. 13, No. 2, 1-14

Snow and Prater Pg. 12

Lorz, M, Mueller, S., & Volery, T. (2013). Entrepreneurship Education: A Systematic

Review of the Methods in Impact Studies. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 21(2),

123-151.

Lowrey, A. (2014, January 5). 50 Years Later, War on Poverty is a Mixed Bag. New York

Times, pp A1-A4.

Martin, B., McNally, J., & Kay, M. (2013). Examining the Formation of Human Capital

in Entrepreneurship: A meta-analysis of Entrepreneurship Education Outcomes.

Journal of Business Venturing, 28(2), 211-224.

Mayer, I., Kortmann, R., Wenzler, I., Wetters, A., & Spaans, J. (2014). Game-Based

Entrepreneurship Education: Identifying Enterprising Personality, Motivation

and Intentions Amongst Engineering Students. Journal of Entrepreneurship

Education, 17(2), 217-244.

Mazzarol, T. (2007). Awakening the Entrepreneur: An Examination of Entrepreneurial

Orientation Among MBA Students. Paper presented at the EFMD 37th

Entrepreneurship, Innovation, & Small Business (EISB) Annual Conference,

September 13-14, 2007.

McEwen, T. & McEwen, B. (2010). Adding Entrepreneurship to the General Education

Curriculum. Allied Academics Conference: Proceedings of the Academy of

Entrepreneurship, 16(2), 37-42.

McGuigan, P. (2016). Practicing What We Preach: Entrepreneurship in

Entrepreneurship Education. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 19(1), 38-

50.

McNally, J., Martin, B. & Kay, N. (2010). Examining the Formation of Human Capital

Entrepreneurship: A Meta-analysis of Entrepreneurship Education Outcomes.

Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management. Montreal

Canada.

Mojica, M., Gebremedhim, T., & Schaeffer, P. (2010). A County-Level Assessment of

Entrepreneurship Development in Appalachia Using Simultaneous Equations.

Journal of Developing Entrepreneurship, 15(1), 3-18.

Morris, M., Neumeyer, X., Kuratko, D. (2015). A Portfolio Perspective on

Entrepreneurship and Economic Development. Small Business Economics,

45(4), 713-728.

Morris, M., Kaplin, J. (2014). Entrepreneurial (Versus Managerial) Competencies as

Drivers of Entrepreneurship Education. Annals of Entrepreneurship Education

and Pedagogy (134-151). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Snow and Prater Pg. 12

Lorz, M, Mueller, S., & Volery, T. (2013). Entrepreneurship Education: A Systematic

Review of the Methods in Impact Studies. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 21(2),

123-151.

Lowrey, A. (2014, January 5). 50 Years Later, War on Poverty is a Mixed Bag. New York

Times, pp A1-A4.

Martin, B., McNally, J., & Kay, M. (2013). Examining the Formation of Human Capital

in Entrepreneurship: A meta-analysis of Entrepreneurship Education Outcomes.

Journal of Business Venturing, 28(2), 211-224.

Mayer, I., Kortmann, R., Wenzler, I., Wetters, A., & Spaans, J. (2014). Game-Based

Entrepreneurship Education: Identifying Enterprising Personality, Motivation

and Intentions Amongst Engineering Students. Journal of Entrepreneurship

Education, 17(2), 217-244.

Mazzarol, T. (2007). Awakening the Entrepreneur: An Examination of Entrepreneurial

Orientation Among MBA Students. Paper presented at the EFMD 37th

Entrepreneurship, Innovation, & Small Business (EISB) Annual Conference,

September 13-14, 2007.

McEwen, T. & McEwen, B. (2010). Adding Entrepreneurship to the General Education

Curriculum. Allied Academics Conference: Proceedings of the Academy of

Entrepreneurship, 16(2), 37-42.

McGuigan, P. (2016). Practicing What We Preach: Entrepreneurship in

Entrepreneurship Education. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 19(1), 38-

50.

McNally, J., Martin, B. & Kay, N. (2010). Examining the Formation of Human Capital

Entrepreneurship: A Meta-analysis of Entrepreneurship Education Outcomes.

Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management. Montreal

Canada.

Mojica, M., Gebremedhim, T., & Schaeffer, P. (2010). A County-Level Assessment of

Entrepreneurship Development in Appalachia Using Simultaneous Equations.

Journal of Developing Entrepreneurship, 15(1), 3-18.

Morris, M., Neumeyer, X., Kuratko, D. (2015). A Portfolio Perspective on

Entrepreneurship and Economic Development. Small Business Economics,

45(4), 713-728.

Morris, M., Kaplin, J. (2014). Entrepreneurial (Versus Managerial) Competencies as

Drivers of Entrepreneurship Education. Annals of Entrepreneurship Education

and Pedagogy (134-151). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 14

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.