Cognitive Psychology Report: Semantic Priming and Emotional Valence

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/11

|13

|3666

|27

Report

AI Summary

This report investigates semantic priming, a cognitive phenomenon where exposure to a word influences the processing of a subsequent related word. The study examines how emotional valence (positive or negative) affects the priming effect at both conscious and unconscious levels of cognitive processing. Sixty-five university students participated in an experiment where they were presented with words and asked to classify them based on emotional valence while also completing a cognitive load task. The research tested three hypotheses: that priming effects would be stronger for negative words, that reaction times would be faster for related words, and that participants with higher anxiety would show a larger priming effect. Results indicated a significant priming effect overall, with greater effects under cognitive load, particularly for negative words. The study highlights the complex interplay between attention, memory, and emotional processing in word recognition and cognitive load.

SEMANTIC PRIMING

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................3

METHOD........................................................................................................................................5

RESULTS........................................................................................................................................6

DISCUSSION..................................................................................................................................9

LIMITATIONS..............................................................................................................................10

CONCLUSION..............................................................................................................................10

REFERENCES..............................................................................................................................12

INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................3

METHOD........................................................................................................................................5

RESULTS........................................................................................................................................6

DISCUSSION..................................................................................................................................9

LIMITATIONS..............................................................................................................................10

CONCLUSION..............................................................................................................................10

REFERENCES..............................................................................................................................12

INTRODUCTION

Cognitive psychology has been evolving regularly and the connection between stimulus,

attention, consciousness and brain function still remains a highly studied but controversial area.

The reading and processing of words can highly depend on whether a person has had a prior

conscious perception of them or they perceive them for the first time. Conscious processing,

however, is traditionally known as the extent to which important stimuli is given selective

attentive space (Deutsch & Deutsch, 1963). Consciously, when a person is processing symbolic

stimuli such as words, it requires an extensive cortical process. Word processing starts in the

ventral visual pathway then processing to the lexical and lastly through semantic access (Gaillard,

Del Cul, Naccache, Vinckier, Cohen &Dehaene, 2006). Visual consciousness and the rate words

are detected depend on perceptual awareness, individual personality traits, lexical decision, and

working memory. These processes are found to interact with each other during this conscious

process.

Processing of stimuli mostly occurs when a person is conscious and aware as opposed to

unconscious one. When being exposed to words influences a response to another word without

conscious guidance or intent, priming occurs. However, if the words are semantically related

such as table and chair, or unrelated like table and tiger, semantic priming occurs. In visual word

recognition, semantic priming is used as a powerful tool to research cognitive processes relating

to memory, language, and attention. Some words, however, are not prime– target pairs but the

human mind constitutes them as related. Examples of these kinds of words are book and worm or

sky and blue. The priming effect has been proven to occur for word pairs that are associatively

related, categorically related or simply look or sound similar (Okubo & Ogawa, 2013).

Further when the unconscious processing of the stimuli that is received becomes

automatic, the process is termed as semantic activation. The semantic activation occurs at the

deepest level of processing, as, Neely and Khan (2001), in their critical re-evaluation highlight

semantic activation is indeed automatic. Words automatically activate their meanings once read

slightly, and the semantic activation is unaffected by the intention for it to occur and by the

amount and quality of the intentional resources allocated to it.

The masked semantic priming paradigm is often referred to as the ‘sandwich’ technique.

This is due to the prime word being sandwiched between the pattern mask and the targeted

stimulus (Forster, n.d.). Research in this area by Merikle, Smilek & Eastwood (2000) concludes

3

Cognitive psychology has been evolving regularly and the connection between stimulus,

attention, consciousness and brain function still remains a highly studied but controversial area.

The reading and processing of words can highly depend on whether a person has had a prior

conscious perception of them or they perceive them for the first time. Conscious processing,

however, is traditionally known as the extent to which important stimuli is given selective

attentive space (Deutsch & Deutsch, 1963). Consciously, when a person is processing symbolic

stimuli such as words, it requires an extensive cortical process. Word processing starts in the

ventral visual pathway then processing to the lexical and lastly through semantic access (Gaillard,

Del Cul, Naccache, Vinckier, Cohen &Dehaene, 2006). Visual consciousness and the rate words

are detected depend on perceptual awareness, individual personality traits, lexical decision, and

working memory. These processes are found to interact with each other during this conscious

process.

Processing of stimuli mostly occurs when a person is conscious and aware as opposed to

unconscious one. When being exposed to words influences a response to another word without

conscious guidance or intent, priming occurs. However, if the words are semantically related

such as table and chair, or unrelated like table and tiger, semantic priming occurs. In visual word

recognition, semantic priming is used as a powerful tool to research cognitive processes relating

to memory, language, and attention. Some words, however, are not prime– target pairs but the

human mind constitutes them as related. Examples of these kinds of words are book and worm or

sky and blue. The priming effect has been proven to occur for word pairs that are associatively

related, categorically related or simply look or sound similar (Okubo & Ogawa, 2013).

Further when the unconscious processing of the stimuli that is received becomes

automatic, the process is termed as semantic activation. The semantic activation occurs at the

deepest level of processing, as, Neely and Khan (2001), in their critical re-evaluation highlight

semantic activation is indeed automatic. Words automatically activate their meanings once read

slightly, and the semantic activation is unaffected by the intention for it to occur and by the

amount and quality of the intentional resources allocated to it.

The masked semantic priming paradigm is often referred to as the ‘sandwich’ technique.

This is due to the prime word being sandwiched between the pattern mask and the targeted

stimulus (Forster, n.d.). Research in this area by Merikle, Smilek & Eastwood (2000) concludes

3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

that stimulus information can be visually perceived even when there is no awareness of

perceiving it. This is further supported by a study by Kinoshita & Norris (2012) who highlighted

that this is related to the belief that an ‘unconscious’ prime will tap into automatic processes and

can, therefore, be used to identify the obligatory representations and processes that support

reading. Presentation of a masked prime word automatically causes a lexical entry to be opened,

if the same word is encountered a second time straight after the masked prime word, the lexical

entry remains opened thus, having little effect on cognitive load (Bodner &Stalinski, 2008).

However, depending on the multitude of information consciously thrown at our working

memory, it can exceed a person’s capacity to process, thus overwhelming the brain and causing

an effect on cognitive processing. This is explained as a cognitive load. This refers to the amount

of mental activity imposed on our semantic memory at any one time. Though the semantic

memory can overload, Neuroscience has mapped a cognitive pathway that demonstrates

unconscious processing, underlying emotional experience and maps out the road to unconscious

processing. Even if stimuli have not been perceived consciously, the sub cortical pathway,

otherwise known as the thalamus – amygdale connection may unconsciously perceive the word

and its meaning (Mack & Rock, 1998).

Consequently, unconsciously perceived stimuli can have an impact on affective state, which

in turn, is affected by a person’s personality traits. A person’s choices and preferences can have

an automatic influence on a participant’s judgement on words whether positive or negative. A

study conducted by Scott, Mogg & Bradley (2001), highlights that participants with a higher

level of depression showed enhanced masked semantic priming of words surrounding depression

as opposed to words related to happiness. Furthermore, four studies conducted by Rogers &

Revelle (1998), discovered that personality factors influenced judgment when the choice was

between positive and negative words. They concluded that mood factor highly influenced

judgement and perception. Their research showed, however, that their cognitive load was not

affected when choosing the word. Participants choose negative valance words a lot quicker than

positive valance words.

The present research will examine the influence of emotional valence words on a semantic

priming level. It will review the priming effect at conscious and unconscious cognitive

processing and how these processes relate to emotional valence words. This research will look at

three hypotheses that will support literature review:

4

perceiving it. This is further supported by a study by Kinoshita & Norris (2012) who highlighted

that this is related to the belief that an ‘unconscious’ prime will tap into automatic processes and

can, therefore, be used to identify the obligatory representations and processes that support

reading. Presentation of a masked prime word automatically causes a lexical entry to be opened,

if the same word is encountered a second time straight after the masked prime word, the lexical

entry remains opened thus, having little effect on cognitive load (Bodner &Stalinski, 2008).

However, depending on the multitude of information consciously thrown at our working

memory, it can exceed a person’s capacity to process, thus overwhelming the brain and causing

an effect on cognitive processing. This is explained as a cognitive load. This refers to the amount

of mental activity imposed on our semantic memory at any one time. Though the semantic

memory can overload, Neuroscience has mapped a cognitive pathway that demonstrates

unconscious processing, underlying emotional experience and maps out the road to unconscious

processing. Even if stimuli have not been perceived consciously, the sub cortical pathway,

otherwise known as the thalamus – amygdale connection may unconsciously perceive the word

and its meaning (Mack & Rock, 1998).

Consequently, unconsciously perceived stimuli can have an impact on affective state, which

in turn, is affected by a person’s personality traits. A person’s choices and preferences can have

an automatic influence on a participant’s judgement on words whether positive or negative. A

study conducted by Scott, Mogg & Bradley (2001), highlights that participants with a higher

level of depression showed enhanced masked semantic priming of words surrounding depression

as opposed to words related to happiness. Furthermore, four studies conducted by Rogers &

Revelle (1998), discovered that personality factors influenced judgment when the choice was

between positive and negative words. They concluded that mood factor highly influenced

judgement and perception. Their research showed, however, that their cognitive load was not

affected when choosing the word. Participants choose negative valance words a lot quicker than

positive valance words.

The present research will examine the influence of emotional valence words on a semantic

priming level. It will review the priming effect at conscious and unconscious cognitive

processing and how these processes relate to emotional valence words. This research will look at

three hypotheses that will support literature review:

4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1. It was hypothesized that the priming effect would be stronger for negative valance words

as compared to positively valance words.

2. It was hypothesized that reaction times would be faster when prime words are related as

compared to unrelated prime words.

3. It was hypothesized that participants who have higher anxiety tendencies will have a

large priming effect across emotional valence words than a participant who has higher

happiness tendencies.

METHOD

Participants

Sixty-five students from a medium sized university in Melbourne participated in the

experiment. All claimed to be native speakers of English.

Materials

Word stimuli. There were sixty target words, half of which were positive and half of

which were negative. In addition to these target words there were thirty neutral words that were

used as unrelated primes. This created sixty prime target pairs for each valence, thirty of which

were related (repetition priming) and thirty were unrelated. The words in each group were

balanced on psycholinguistic characteristics including word frequency, letter length, and

association strength using the website of Landauer and Dumais. Repetition priming was used

such that each target word (in lower case) was primed by the same word in upper case (related

prime-target pair), or was paired with a prime word (in upper case) of neutral emotional valence

(unrelated prime-target pair). An example negative related repetition prime-target pair was

TORTURE-torture, and the corresponding unrelated prime-target pair was JETTY-torture.

Individual differences measures. The state items from the Spielberg State-Trait Anxiety

Inventory (SSTAI; Spielberger et al., 1983) were used to provide a measure of anxiety, which is

a negatively valenced emotion. Items from the Oxford Happiness Scale (OHS; Argyle et al.,

1995) were used to provide a measure of happiness, which is a positive valenced emotion.

Procedure

Participants reached the experiment via a link on the Learning Management System.

Participants were informed about the sequence of events in the task, and asked to respond as

quickly and as accurately as possible. For each of the three main sections of the experiment, they

completed 10 practice trials followed by 60 experimental trials. The first section of the

5

as compared to positively valance words.

2. It was hypothesized that reaction times would be faster when prime words are related as

compared to unrelated prime words.

3. It was hypothesized that participants who have higher anxiety tendencies will have a

large priming effect across emotional valence words than a participant who has higher

happiness tendencies.

METHOD

Participants

Sixty-five students from a medium sized university in Melbourne participated in the

experiment. All claimed to be native speakers of English.

Materials

Word stimuli. There were sixty target words, half of which were positive and half of

which were negative. In addition to these target words there were thirty neutral words that were

used as unrelated primes. This created sixty prime target pairs for each valence, thirty of which

were related (repetition priming) and thirty were unrelated. The words in each group were

balanced on psycholinguistic characteristics including word frequency, letter length, and

association strength using the website of Landauer and Dumais. Repetition priming was used

such that each target word (in lower case) was primed by the same word in upper case (related

prime-target pair), or was paired with a prime word (in upper case) of neutral emotional valence

(unrelated prime-target pair). An example negative related repetition prime-target pair was

TORTURE-torture, and the corresponding unrelated prime-target pair was JETTY-torture.

Individual differences measures. The state items from the Spielberg State-Trait Anxiety

Inventory (SSTAI; Spielberger et al., 1983) were used to provide a measure of anxiety, which is

a negatively valenced emotion. Items from the Oxford Happiness Scale (OHS; Argyle et al.,

1995) were used to provide a measure of happiness, which is a positive valenced emotion.

Procedure

Participants reached the experiment via a link on the Learning Management System.

Participants were informed about the sequence of events in the task, and asked to respond as

quickly and as accurately as possible. For each of the three main sections of the experiment, they

completed 10 practice trials followed by 60 experimental trials. The first section of the

5

experiment asked participants to classify words presented on the screen as negative or positive

emotional valence (Meaning Task). The second task repeated the meaning task, but this time in a

dual task situation (Cognitive Load Task), where they were also asked to remember a pattern

containing four x's and 4 o's in various configurations. After every five trials of the meaning task,

they were asked to recall the current pattern, and then were asked to remember a new pattern.

Following this, they were presented with a list of questions that they should answer based on

their initial intuition without thinking too hard. The questions were from the two surveys, with

the questions from the SSTAI (Spielberger et al., 1983) being presented first and the OHS

second (Hills & Argyle, 2002). The experimental task and the two short surveys took about 15

minutes to complete.

All of the participants performed the sequence of tasks in the same order without

counterbalancing, beginning with the Meaning Task, followed by the Cognitive Load Task

followed by the surveys. The instructions in the Meaning Task were designed to get participants

to make a judgement about the words based on them being either of negative valence or positive

valence. In the Cognitive Load Task, the participants were performing two tasks simultaneously.

At the end of each block of trials, the participant were given performance feedback on latency to

response and accuracy.

In terms of the stimulus presentation, the main stimuli always appeared in the centre of

the screen. The timing was as follows: (a) a forward letter mask appeared for 500 ms; (b) the

prime was then presented for 48 ms; (c) a backward mask appeared for 96 ms; and (e) the target

remained on the screen until the participant responded. In the Cognitive Load Task, the pattern to

be remembered appeared on the screen for 2500 ms, then five trials of the Meaning Task

occurred, and then the participant was asked to recall the pattern. The participant had 20 seconds

to record their response, and were given feedback as to whether the entry was correct before

being shown another pattern to remember.

RESULTS

Data were screened for response times that were less than 200 ms or greater than 1000

ms, and for incomplete data sets. The final data set contained data from 65 participants. To

confirm that participants were successfully completing the meaning judgement in both

conditions tasks, the percentage of correct responses was collated for all conditions, and

presented in Table 1.

6

emotional valence (Meaning Task). The second task repeated the meaning task, but this time in a

dual task situation (Cognitive Load Task), where they were also asked to remember a pattern

containing four x's and 4 o's in various configurations. After every five trials of the meaning task,

they were asked to recall the current pattern, and then were asked to remember a new pattern.

Following this, they were presented with a list of questions that they should answer based on

their initial intuition without thinking too hard. The questions were from the two surveys, with

the questions from the SSTAI (Spielberger et al., 1983) being presented first and the OHS

second (Hills & Argyle, 2002). The experimental task and the two short surveys took about 15

minutes to complete.

All of the participants performed the sequence of tasks in the same order without

counterbalancing, beginning with the Meaning Task, followed by the Cognitive Load Task

followed by the surveys. The instructions in the Meaning Task were designed to get participants

to make a judgement about the words based on them being either of negative valence or positive

valence. In the Cognitive Load Task, the participants were performing two tasks simultaneously.

At the end of each block of trials, the participant were given performance feedback on latency to

response and accuracy.

In terms of the stimulus presentation, the main stimuli always appeared in the centre of

the screen. The timing was as follows: (a) a forward letter mask appeared for 500 ms; (b) the

prime was then presented for 48 ms; (c) a backward mask appeared for 96 ms; and (e) the target

remained on the screen until the participant responded. In the Cognitive Load Task, the pattern to

be remembered appeared on the screen for 2500 ms, then five trials of the Meaning Task

occurred, and then the participant was asked to recall the pattern. The participant had 20 seconds

to record their response, and were given feedback as to whether the entry was correct before

being shown another pattern to remember.

RESULTS

Data were screened for response times that were less than 200 ms or greater than 1000

ms, and for incomplete data sets. The final data set contained data from 65 participants. To

confirm that participants were successfully completing the meaning judgement in both

conditions tasks, the percentage of correct responses was collated for all conditions, and

presented in Table 1.

6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

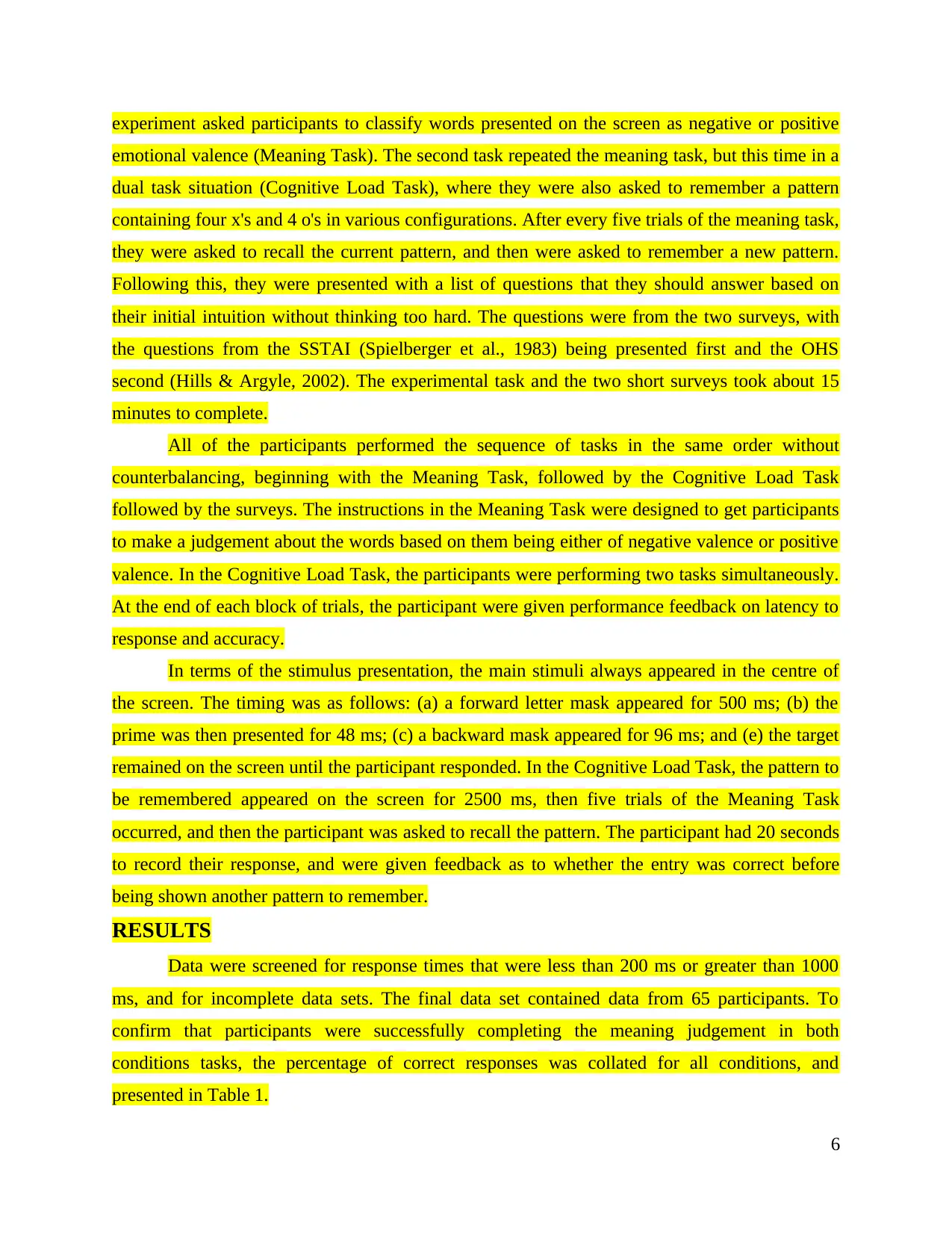

Table 1

Mean and SDs of the percentage of correct responses across conditions

Meaning Cognitive Load

Mean SD Mean SD

Percent

correct 94.10 (5.19) 94.97 (4.31)

As can be seen from this table, the mean percent correct for all tasks was well above 90%

and there were no obvious differences across the two tasks. The mean percent correct for the

pattern task was 82.11 (SD=15.63), confirming that participants were genuinely attempting the

second task in the cognitive load condition. Reaction times as a function of emotional valence,

task condition and prime relatedness are presented in Figure 1.

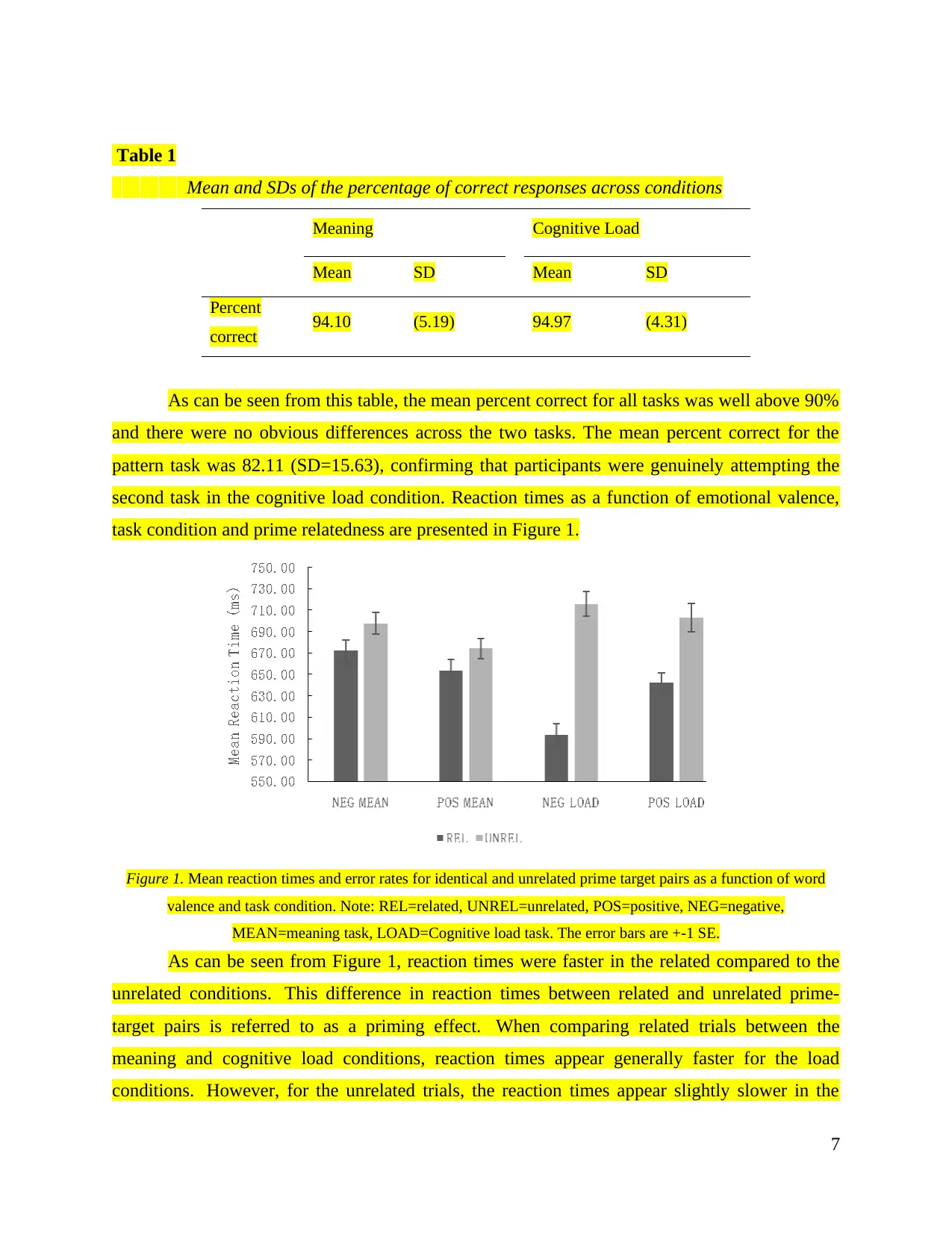

Figure 1. Mean reaction times and error rates for identical and unrelated prime target pairs as a function of word

valence and task condition. Note: REL=related, UNREL=unrelated, POS=positive, NEG=negative,

MEAN=meaning task, LOAD=Cognitive load task. The error bars are +-1 SE.

As can be seen from Figure 1, reaction times were faster in the related compared to the

unrelated conditions. This difference in reaction times between related and unrelated prime-

target pairs is referred to as a priming effect. When comparing related trials between the

meaning and cognitive load conditions, reaction times appear generally faster for the load

conditions. However, for the unrelated trials, the reaction times appear slightly slower in the

7

Mean and SDs of the percentage of correct responses across conditions

Meaning Cognitive Load

Mean SD Mean SD

Percent

correct 94.10 (5.19) 94.97 (4.31)

As can be seen from this table, the mean percent correct for all tasks was well above 90%

and there were no obvious differences across the two tasks. The mean percent correct for the

pattern task was 82.11 (SD=15.63), confirming that participants were genuinely attempting the

second task in the cognitive load condition. Reaction times as a function of emotional valence,

task condition and prime relatedness are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mean reaction times and error rates for identical and unrelated prime target pairs as a function of word

valence and task condition. Note: REL=related, UNREL=unrelated, POS=positive, NEG=negative,

MEAN=meaning task, LOAD=Cognitive load task. The error bars are +-1 SE.

As can be seen from Figure 1, reaction times were faster in the related compared to the

unrelated conditions. This difference in reaction times between related and unrelated prime-

target pairs is referred to as a priming effect. When comparing related trials between the

meaning and cognitive load conditions, reaction times appear generally faster for the load

conditions. However, for the unrelated trials, the reaction times appear slightly slower in the

7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

load task. In terms of priming effects, it appears the largest priming effects observed were for

negative words in the cognitive load task, followed by positive words in the same task. The

priming effects for the meaning tasks appear smaller than priming effects in the load condition,

and appear relatively similar in size across valence. The same data from Figure 1 are presented to

highlight priming effects for negatively and positively valenced words for the different task

conditions in Figure 2.

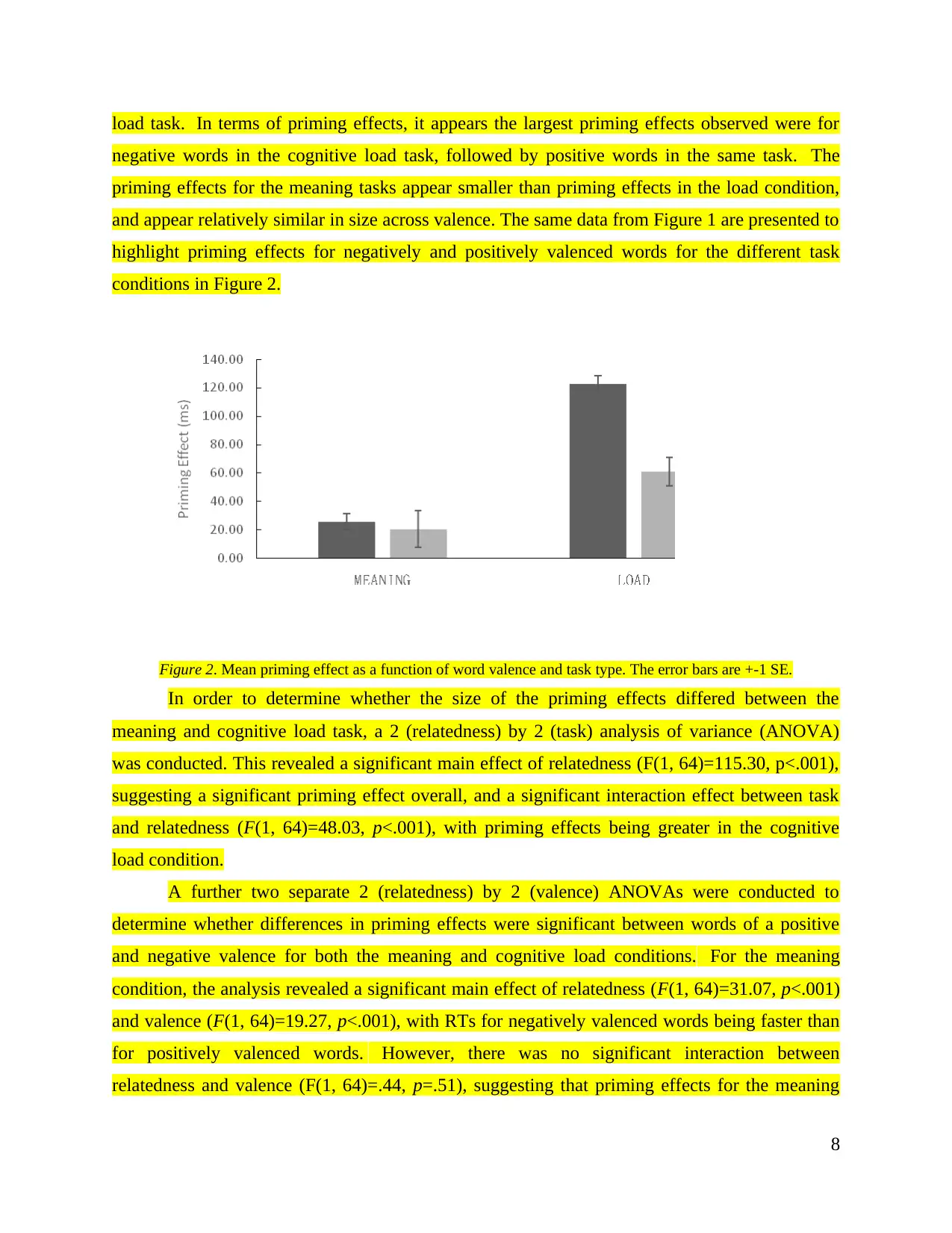

Figure 2. Mean priming effect as a function of word valence and task type. The error bars are +-1 SE.

In order to determine whether the size of the priming effects differed between the

meaning and cognitive load task, a 2 (relatedness) by 2 (task) analysis of variance (ANOVA)

was conducted. This revealed a significant main effect of relatedness (F(1, 64)=115.30, p<.001),

suggesting a significant priming effect overall, and a significant interaction effect between task

and relatedness (F(1, 64)=48.03, p<.001), with priming effects being greater in the cognitive

load condition.

A further two separate 2 (relatedness) by 2 (valence) ANOVAs were conducted to

determine whether differences in priming effects were significant between words of a positive

and negative valence for both the meaning and cognitive load conditions. For the meaning

condition, the analysis revealed a significant main effect of relatedness (F(1, 64)=31.07, p<.001)

and valence (F(1, 64)=19.27, p<.001), with RTs for negatively valenced words being faster than

for positively valenced words. However, there was no significant interaction between

relatedness and valence (F(1, 64)=.44, p=.51), suggesting that priming effects for the meaning

8

negative words in the cognitive load task, followed by positive words in the same task. The

priming effects for the meaning tasks appear smaller than priming effects in the load condition,

and appear relatively similar in size across valence. The same data from Figure 1 are presented to

highlight priming effects for negatively and positively valenced words for the different task

conditions in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Mean priming effect as a function of word valence and task type. The error bars are +-1 SE.

In order to determine whether the size of the priming effects differed between the

meaning and cognitive load task, a 2 (relatedness) by 2 (task) analysis of variance (ANOVA)

was conducted. This revealed a significant main effect of relatedness (F(1, 64)=115.30, p<.001),

suggesting a significant priming effect overall, and a significant interaction effect between task

and relatedness (F(1, 64)=48.03, p<.001), with priming effects being greater in the cognitive

load condition.

A further two separate 2 (relatedness) by 2 (valence) ANOVAs were conducted to

determine whether differences in priming effects were significant between words of a positive

and negative valence for both the meaning and cognitive load conditions. For the meaning

condition, the analysis revealed a significant main effect of relatedness (F(1, 64)=31.07, p<.001)

and valence (F(1, 64)=19.27, p<.001), with RTs for negatively valenced words being faster than

for positively valenced words. However, there was no significant interaction between

relatedness and valence (F(1, 64)=.44, p=.51), suggesting that priming effects for the meaning

8

conditions were relatively similar across valence. For the cognitive load condition, the analysis

revealed significant main effects for both relatedness (F(1, 64)=94.34, p<.001) and valence (F(1,

64)=4.88, p=.03), again revealing RTs for negative trials were faster overall compared to positive

trials. In contrast to the meaning task, a significant interaction between relatedness and valence

was observed (F(1, 64)=22.06, p<.001), confirming the size of the priming effect for negatively

valenced words was greater than that of positively valenced words within this cognitive load task

condition.

To examine any potential correlations between priming effects and individual difference

variables, the anxiety (STAI) and happiness (OHS) scores were correlated with the size of the

priming effect across emotional valence and task condition. While there was an expected

negative correlation between anxiety and happiness, (r = -.82, p < .001), none of the correlations

of specific interest to the research hypotheses were significant.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the semantic priming effect in conscious and

unconscious processing and how these processes relate to emotional valence words.

Furthermore, it reviews how individual differences such as anxiety and happiness can affect a

persons' cognitive processing.

The first hypothesis was supported as the results show that a significant priming effect sizes

occurred for both positive and negative valance words; however, there were no results for neutral

words. The largest priming effect that occurred was for the negative words in the cognitive load

task. Selection of these negative words was automatic showing that the priming effect was not

reduced under the cognitive load. With the events of co-occurrence within the larger text of the

task and word frequencies, the negative valence word was able to be computed a lot quicker.

Positive valance words usually have a higher number of associations than negative valance

words and therefore, they may be more prone to elicit semantic integration (Kuhlmann,

Hofmann, Briesemeister & Jacobs, 2016).

The second hypothesis was also supported as expected stating that participants reaction

times would be faster when prime words in the target pair are related than unrelated prime

words. When faced with related prime target pairs, participants reacted a lot faster as compared

to unrelated prime target pairs. When comparing tasks, reaction times were generally faster for

the cognitive load and when the words have a negative valence. Meyer and Schvaneveldt (1971),

9

revealed significant main effects for both relatedness (F(1, 64)=94.34, p<.001) and valence (F(1,

64)=4.88, p=.03), again revealing RTs for negative trials were faster overall compared to positive

trials. In contrast to the meaning task, a significant interaction between relatedness and valence

was observed (F(1, 64)=22.06, p<.001), confirming the size of the priming effect for negatively

valenced words was greater than that of positively valenced words within this cognitive load task

condition.

To examine any potential correlations between priming effects and individual difference

variables, the anxiety (STAI) and happiness (OHS) scores were correlated with the size of the

priming effect across emotional valence and task condition. While there was an expected

negative correlation between anxiety and happiness, (r = -.82, p < .001), none of the correlations

of specific interest to the research hypotheses were significant.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the semantic priming effect in conscious and

unconscious processing and how these processes relate to emotional valence words.

Furthermore, it reviews how individual differences such as anxiety and happiness can affect a

persons' cognitive processing.

The first hypothesis was supported as the results show that a significant priming effect sizes

occurred for both positive and negative valance words; however, there were no results for neutral

words. The largest priming effect that occurred was for the negative words in the cognitive load

task. Selection of these negative words was automatic showing that the priming effect was not

reduced under the cognitive load. With the events of co-occurrence within the larger text of the

task and word frequencies, the negative valence word was able to be computed a lot quicker.

Positive valance words usually have a higher number of associations than negative valance

words and therefore, they may be more prone to elicit semantic integration (Kuhlmann,

Hofmann, Briesemeister & Jacobs, 2016).

The second hypothesis was also supported as expected stating that participants reaction

times would be faster when prime words in the target pair are related than unrelated prime

words. When faced with related prime target pairs, participants reacted a lot faster as compared

to unrelated prime target pairs. When comparing tasks, reaction times were generally faster for

the cognitive load and when the words have a negative valence. Meyer and Schvaneveldt (1971),

9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

state that our long-term memory is organised semantically, in other words, there is a structure

within our long-term memory in which the location of two associated words are closer than those

of two associated words.

If the word is familiar to the participant, the starting location to cognitively process this

word is in the familiar sector of the lexical decision making. This is generally faster; a major

shift between locations in the brain is required to access potential information about unrelated

words, whereas such a shift is not required for related words.

Third hypothesis was the unsupported hypothesis where contrary to expectations, a negative

correlation was found between happiness and anxiety.

LIMITATIONS

However this does not show enough correlations of specific interest between priming effect

and individual methodological problem that might have interfered with the ability to find a

correlation between individual differences such as anxiety and happiness and persons' cognitive.

By extending the survey and including more emotions, such as depression and apprehensive for

negative valance and self-worth, and health traits for the positive valance, it would have helped

in analysing wider aspects. The involvement of negative and positive emotions such as anxiety

and happiness have briefly been explored, but it is equally important to explore how mental

health traits such as anxiety and happiness correlate to prime words both negative and positive

and how these words provoke an emotional response for participants. Additionally, further

research is needed to investigate the impact of emotion- evoking words on behaviour.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study has highlighted some important key findings surrounding priming

effect on conscious and unconscious levels, however further research is needed to establish

whether or not emotional valence words affected participant’s mental health traits of feeling

anxious or happiness. It was highlighted that a significant priming effect did occur when

participants viewed emotional valence words. For negative valance words particularly, the size

of the priming effect was greater than positively valance words. The reaction time for negative

prime words was significantly faster than positive prime words, showing that negative words

increased unconscious processing speed particularly when the targeted words were related.

Overall, regardless of results only supporting two out of the three hypotheses,

comprehensively results demonstrate how powerful the connection between stimulus, attention,

10

within our long-term memory in which the location of two associated words are closer than those

of two associated words.

If the word is familiar to the participant, the starting location to cognitively process this

word is in the familiar sector of the lexical decision making. This is generally faster; a major

shift between locations in the brain is required to access potential information about unrelated

words, whereas such a shift is not required for related words.

Third hypothesis was the unsupported hypothesis where contrary to expectations, a negative

correlation was found between happiness and anxiety.

LIMITATIONS

However this does not show enough correlations of specific interest between priming effect

and individual methodological problem that might have interfered with the ability to find a

correlation between individual differences such as anxiety and happiness and persons' cognitive.

By extending the survey and including more emotions, such as depression and apprehensive for

negative valance and self-worth, and health traits for the positive valance, it would have helped

in analysing wider aspects. The involvement of negative and positive emotions such as anxiety

and happiness have briefly been explored, but it is equally important to explore how mental

health traits such as anxiety and happiness correlate to prime words both negative and positive

and how these words provoke an emotional response for participants. Additionally, further

research is needed to investigate the impact of emotion- evoking words on behaviour.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study has highlighted some important key findings surrounding priming

effect on conscious and unconscious levels, however further research is needed to establish

whether or not emotional valence words affected participant’s mental health traits of feeling

anxious or happiness. It was highlighted that a significant priming effect did occur when

participants viewed emotional valence words. For negative valance words particularly, the size

of the priming effect was greater than positively valance words. The reaction time for negative

prime words was significantly faster than positive prime words, showing that negative words

increased unconscious processing speed particularly when the targeted words were related.

Overall, regardless of results only supporting two out of the three hypotheses,

comprehensively results demonstrate how powerful the connection between stimulus, attention,

10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

consciousness and brain function is and how someone’s perception of words can still influence

conscious behaviour through reaction time and valance.

11

conscious behaviour through reaction time and valance.

11

REFERENCES

Bodner, G.E., &Stalinski, S.M.. (2008). Masked repetition priming and proportion effects under

cognitive load. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 6(2), 127-131.

Deutsch, J. A., & Deutsch, D. (1963). Attention: Some theoretical considerations.

Psychological Review, 70, 80-90.

Heyman, T., Van Rensbergen, B., Storms, G., Hutchison, K. A., & De Deyne, S. (2015). The

influence of working memory load on semantic priming.

Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 41(3), 911-920.

Hills, P., & Argyle, M. (2002). The Oxford happiness questionnaire: A compact scale for the

measurement of psychological well-being.

Personality and Individual Differences, 33,1073-1082.

Merikle, P. M., Smilek, D., & Eastwood, J. D. (2001). Perception without awareness:

perspectives from cognitive psychology. Cognition, 79, 115-134.

Meyer, D. E., L. Schvaneveldt, R. W. (1971).

Facilitation in recognizing pairs of words: Evidence of a dependence between retrieval op

erations. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 1971, 90, 227-234.

Neely, J.H.& Kahan, T.A.. (2001). Is semantic activation automatic? A critical re-evaluation. In:

Roedinger, H.L., Naime, J.S., &Suprenant., A.M. (Eds). The nature of

remembering. Essays in honour of Robert G. Crowder. pp 69-93. Washington, DC, US:

American Psychological Association.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1983). Manual for

the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

12

Bodner, G.E., &Stalinski, S.M.. (2008). Masked repetition priming and proportion effects under

cognitive load. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 6(2), 127-131.

Deutsch, J. A., & Deutsch, D. (1963). Attention: Some theoretical considerations.

Psychological Review, 70, 80-90.

Heyman, T., Van Rensbergen, B., Storms, G., Hutchison, K. A., & De Deyne, S. (2015). The

influence of working memory load on semantic priming.

Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 41(3), 911-920.

Hills, P., & Argyle, M. (2002). The Oxford happiness questionnaire: A compact scale for the

measurement of psychological well-being.

Personality and Individual Differences, 33,1073-1082.

Merikle, P. M., Smilek, D., & Eastwood, J. D. (2001). Perception without awareness:

perspectives from cognitive psychology. Cognition, 79, 115-134.

Meyer, D. E., L. Schvaneveldt, R. W. (1971).

Facilitation in recognizing pairs of words: Evidence of a dependence between retrieval op

erations. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 1971, 90, 227-234.

Neely, J.H.& Kahan, T.A.. (2001). Is semantic activation automatic? A critical re-evaluation. In:

Roedinger, H.L., Naime, J.S., &Suprenant., A.M. (Eds). The nature of

remembering. Essays in honour of Robert G. Crowder. pp 69-93. Washington, DC, US:

American Psychological Association.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1983). Manual for

the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 13

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.