Western Sydney University: SFRC Beam Bending Behaviour Thesis

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/07

|18

|4216

|22

Thesis and Dissertation

AI Summary

This thesis investigates the bending behavior of steel fiber reinforced concrete (SFRC) beams. The study reviews the existing literature on SFRC, focusing on both experimental and modeling methods. Experimental methods discussed include tests conducted by researchers such as Hannant, Noguchi, Hamid, Behzad, and Buttignol, exploring the impact of steel fiber content on flexural strength, crack patterns, and deflection. Modeling methods involve constitutive models and analysis of flexural capacity. The thesis includes detailed descriptions of experimental setups, results, and conclusions drawn from various studies. Key findings highlight the enhanced ductility, increased flexural strength, and reduced crack width observed in SFRC beams compared to traditional reinforced concrete. The research emphasizes the importance of steel fiber volume and its influence on the compressive and tensile properties of concrete. The thesis concludes by summarizing the benefits of SFRC in structural applications and its potential for improving the performance of concrete structures. This research contributes to the body of knowledge on SFRC and its application in civil engineering.

Thesis Title

Bending behaviour of steel fibre

reinforcement concrete beams and model

assignment

Student Name

A thesis submitted for partial fulfilment for the degree of

Bachelor of Engineering (Honours)/

Supervisor(s)

XXXXX

School of Computing Engineering & Mathematics

Western Sydney University

Month, Year

Page 1 of 18

Bending behaviour of steel fibre

reinforcement concrete beams and model

assignment

Student Name

A thesis submitted for partial fulfilment for the degree of

Bachelor of Engineering (Honours)/

Supervisor(s)

XXXXX

School of Computing Engineering & Mathematics

Western Sydney University

Month, Year

Page 1 of 18

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Contents

ABSTRACT..........................................................................................................................................1

LIST OF FICURES...............................................................................................................................1

INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................3

Overview...........................................................................................................................................3

Objectives..........................................................................................................................................3

LITERATURE REVIEW......................................................................................................................3

USING EXPERIMENTAL METHODS............................................................................................3

USING MODELLING METHODS..................................................................................................9

Constitutive model for SGR concrete............................................................................................9

Flexural capacity of SFRC...........................................................................................................12

CONCLUSION...................................................................................................................................12

REFERENCES....................................................................................................................................13

LIST OF FICURES

Figure 1. Load versus mid span displacement.......................................................................................4

Figure 2. Hamid beam experiment test setup.........................................................................................5

Figure 3. Load against deflection for fiber reinforced and reinforced concrete.....................................6

Figure 4. Stress strain curve for various reinforcement.........................................................................6

Figure 5. Nominal stress against deflection for 30kg/m3 concrete and 60 kg/m3...................................7

Figure 6. Four point bending test used by Buttignol..............................................................................7

Figure 7. Concrete beam length and sectional properties used by Buttignol in his experiments............8

Figure 8. Pressing force versus deflection of the reinforced and fiber reinforced beam........................8

Figure 9. Compressive stress against strain and tensile stress against strain..........................................9

Figure 10. Schematic diagram of a fiber embedded in concrete..........................................................10

Figure 11. Typical stress-strain response of SFRC in tension..............................................................10

Figure 12. Schematic diagram of SFR concrete section in flexure; stress and strain profile...............12

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. The mean Value of cube compressive strength according to Hamid........................................4

Table 2. Flexural cracking load and ultimate cracking load for RC and SFARC...................................4

Table 3. Ultimate flexural load and mid span displacement at ultimate tensile load..............................5

Table 4. Number of cracks and crack average width.............................................................................5

Table 5. Buttignol's concrete mixing properties....................................................................................7

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

RC: Reinforced Concrete

Page 2 of 18

ABSTRACT..........................................................................................................................................1

LIST OF FICURES...............................................................................................................................1

INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................3

Overview...........................................................................................................................................3

Objectives..........................................................................................................................................3

LITERATURE REVIEW......................................................................................................................3

USING EXPERIMENTAL METHODS............................................................................................3

USING MODELLING METHODS..................................................................................................9

Constitutive model for SGR concrete............................................................................................9

Flexural capacity of SFRC...........................................................................................................12

CONCLUSION...................................................................................................................................12

REFERENCES....................................................................................................................................13

LIST OF FICURES

Figure 1. Load versus mid span displacement.......................................................................................4

Figure 2. Hamid beam experiment test setup.........................................................................................5

Figure 3. Load against deflection for fiber reinforced and reinforced concrete.....................................6

Figure 4. Stress strain curve for various reinforcement.........................................................................6

Figure 5. Nominal stress against deflection for 30kg/m3 concrete and 60 kg/m3...................................7

Figure 6. Four point bending test used by Buttignol..............................................................................7

Figure 7. Concrete beam length and sectional properties used by Buttignol in his experiments............8

Figure 8. Pressing force versus deflection of the reinforced and fiber reinforced beam........................8

Figure 9. Compressive stress against strain and tensile stress against strain..........................................9

Figure 10. Schematic diagram of a fiber embedded in concrete..........................................................10

Figure 11. Typical stress-strain response of SFRC in tension..............................................................10

Figure 12. Schematic diagram of SFR concrete section in flexure; stress and strain profile...............12

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. The mean Value of cube compressive strength according to Hamid........................................4

Table 2. Flexural cracking load and ultimate cracking load for RC and SFARC...................................4

Table 3. Ultimate flexural load and mid span displacement at ultimate tensile load..............................5

Table 4. Number of cracks and crack average width.............................................................................5

Table 5. Buttignol's concrete mixing properties....................................................................................7

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

RC: Reinforced Concrete

Page 2 of 18

SF: Steel Fiber.

SFRC: Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete

LVDT: Linear Variable Differential Transducer

SFARC: Steel Fiber Added Reinforced Concrete.

Page 3 of 18

SFRC: Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete

LVDT: Linear Variable Differential Transducer

SFARC: Steel Fiber Added Reinforced Concrete.

Page 3 of 18

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ABSTRACT

Reinforced concrete has been used for various construction works over the years. Numerous materials

and forms have been developed to come up with better concrete that can withstand bigger loads in

both tension and compression. One such material is the steel fiber. The steel fiber arranged randomly

has been proven be superior to the traditional reinforced concrete. This report aims at reviewing the

mechanical bending behaviour of Steel Fiber Reinforced concrete experimentally and using modal

assessment.

Page 4 of 18

Reinforced concrete has been used for various construction works over the years. Numerous materials

and forms have been developed to come up with better concrete that can withstand bigger loads in

both tension and compression. One such material is the steel fiber. The steel fiber arranged randomly

has been proven be superior to the traditional reinforced concrete. This report aims at reviewing the

mechanical bending behaviour of Steel Fiber Reinforced concrete experimentally and using modal

assessment.

Page 4 of 18

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

STATEMENT OF AUTHENTICATION

This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of any other degree or

diploma and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, this thesis contains no material

previously published or written by another person, expect when due reference is made in the

text of this thesis.

Signature ................................................. Date ........ /........ /........

Page 5 of 18

This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of any other degree or

diploma and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, this thesis contains no material

previously published or written by another person, expect when due reference is made in the

text of this thesis.

Signature ................................................. Date ........ /........ /........

Page 5 of 18

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Page 6 of 18

Page 6 of 18

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

INTRODUCTION

Overview

By far, structural concrete is one of the popularly used building and construction material in the field

of engineering today. Concrete on its own has little ability to withstand strains and stresses without

cracking since it is a brittle material. Reinforcement using steel bars is done to increase the endurance

to stresses and strains of the concrete. The bars are placed at certain critical locations of the beam in a

continuous manner in order to withstand the tensile and compressive loads on the beam. Other

methods of reinforcing the concrete beams is by using fibers. Fibers forms a short, randomly

distributed and discontinuous reinforcements in the concrete structure. Concrete that has been

reinforced using fibers is called Fiber Reinforced Concrete. The most common fibers used in the

world is the Steel Fiber (SF). Concrete reinforced with SF are called Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete

(SFRC) or Steel Fiber Added Concrete (SFAC) beams.

Steel fibers are used to control the shrinkage of concrete during drying process and the plastic

deformation of the beam by improving on the toughness of the beams, the capacity of absorbing the

strain energy, improving the ductility of the beam before fracturing, improving on durability by

reducing formation of cracks.

Beams reinforced with SF have numerous application such as in building bridges, slabs, dams, decks,

slope stabilization, tunnel linings. It is also used for retrofitting against earthquakes, construction of

marine vessels, pipelines and sewaline construction, fire protection coatings and many other

applications where huge live loads are incurred.

Objectives

This report aims at describing the bending behaviour of the steel fiber reinforced concrete.

LITERATURE REVIEW

USING EXPERIMENTAL METHODS.

Hannant, in his book ‘Fiber Cements and Fiber Concrete’, stated that the flexural strength of concrete

is affected by the numbers of steel fibers used for reinforcement. The reinforced concrete’s flexural

stress changes in comparrison to the compressive and tensile properties of unreinforced concrete.

(Hannant, 2008).

Noguchi in his paper determined the change in tensile strength of concrete when reinforced with an

additional 2% of the steel fibers. He found out that the tensile strength of the concrete improves by

55%. He also found out that with steel fiber addition of 1.2% the compressive strength improves by

20%. Addition of steel fibers to a concrete by 1.5% volume changes the compressive strength by 15%.

(Noguchi, 2018).

Hamid used two grades of concrete for 50MPa and 30 MPa. He mixed attained the grades by

following the standard mixing guidelines. In his study, he used hooked end shaped fibers of steel. In

his work, he first determined the percentage of steel fibers in the concrete. He then conducted cube

compressive strength tests after 28 days using the BS 1881 rules. He prepared 150 x 150 x 150 cubes

of concrete. He used a hand poker machine to compact the concrete. He compacted five specimens for

each of the grades. (Hamid, 2011).

Page 7 of 18

Overview

By far, structural concrete is one of the popularly used building and construction material in the field

of engineering today. Concrete on its own has little ability to withstand strains and stresses without

cracking since it is a brittle material. Reinforcement using steel bars is done to increase the endurance

to stresses and strains of the concrete. The bars are placed at certain critical locations of the beam in a

continuous manner in order to withstand the tensile and compressive loads on the beam. Other

methods of reinforcing the concrete beams is by using fibers. Fibers forms a short, randomly

distributed and discontinuous reinforcements in the concrete structure. Concrete that has been

reinforced using fibers is called Fiber Reinforced Concrete. The most common fibers used in the

world is the Steel Fiber (SF). Concrete reinforced with SF are called Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete

(SFRC) or Steel Fiber Added Concrete (SFAC) beams.

Steel fibers are used to control the shrinkage of concrete during drying process and the plastic

deformation of the beam by improving on the toughness of the beams, the capacity of absorbing the

strain energy, improving the ductility of the beam before fracturing, improving on durability by

reducing formation of cracks.

Beams reinforced with SF have numerous application such as in building bridges, slabs, dams, decks,

slope stabilization, tunnel linings. It is also used for retrofitting against earthquakes, construction of

marine vessels, pipelines and sewaline construction, fire protection coatings and many other

applications where huge live loads are incurred.

Objectives

This report aims at describing the bending behaviour of the steel fiber reinforced concrete.

LITERATURE REVIEW

USING EXPERIMENTAL METHODS.

Hannant, in his book ‘Fiber Cements and Fiber Concrete’, stated that the flexural strength of concrete

is affected by the numbers of steel fibers used for reinforcement. The reinforced concrete’s flexural

stress changes in comparrison to the compressive and tensile properties of unreinforced concrete.

(Hannant, 2008).

Noguchi in his paper determined the change in tensile strength of concrete when reinforced with an

additional 2% of the steel fibers. He found out that the tensile strength of the concrete improves by

55%. He also found out that with steel fiber addition of 1.2% the compressive strength improves by

20%. Addition of steel fibers to a concrete by 1.5% volume changes the compressive strength by 15%.

(Noguchi, 2018).

Hamid used two grades of concrete for 50MPa and 30 MPa. He mixed attained the grades by

following the standard mixing guidelines. In his study, he used hooked end shaped fibers of steel. In

his work, he first determined the percentage of steel fibers in the concrete. He then conducted cube

compressive strength tests after 28 days using the BS 1881 rules. He prepared 150 x 150 x 150 cubes

of concrete. He used a hand poker machine to compact the concrete. He compacted five specimens for

each of the grades. (Hamid, 2011).

Page 7 of 18

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Table 1. The mean Value of cube’s compressive properties according to Hamid.

He concluded that the cube compressive strength of cubes made of the two concrete grades increased

notably after the addition of 1% steel fiber by volume, by a bigger margin than the rest of the of the

volumes.

Table 2. Flexural cracking load and ultimate cracking load for RC and SFARC.

From his results, he also showed that the prisms’ flexural toughness and the first cracking strength of

C30 and C50 improved relatively when a 1%volume of SF was added then the other volumes.

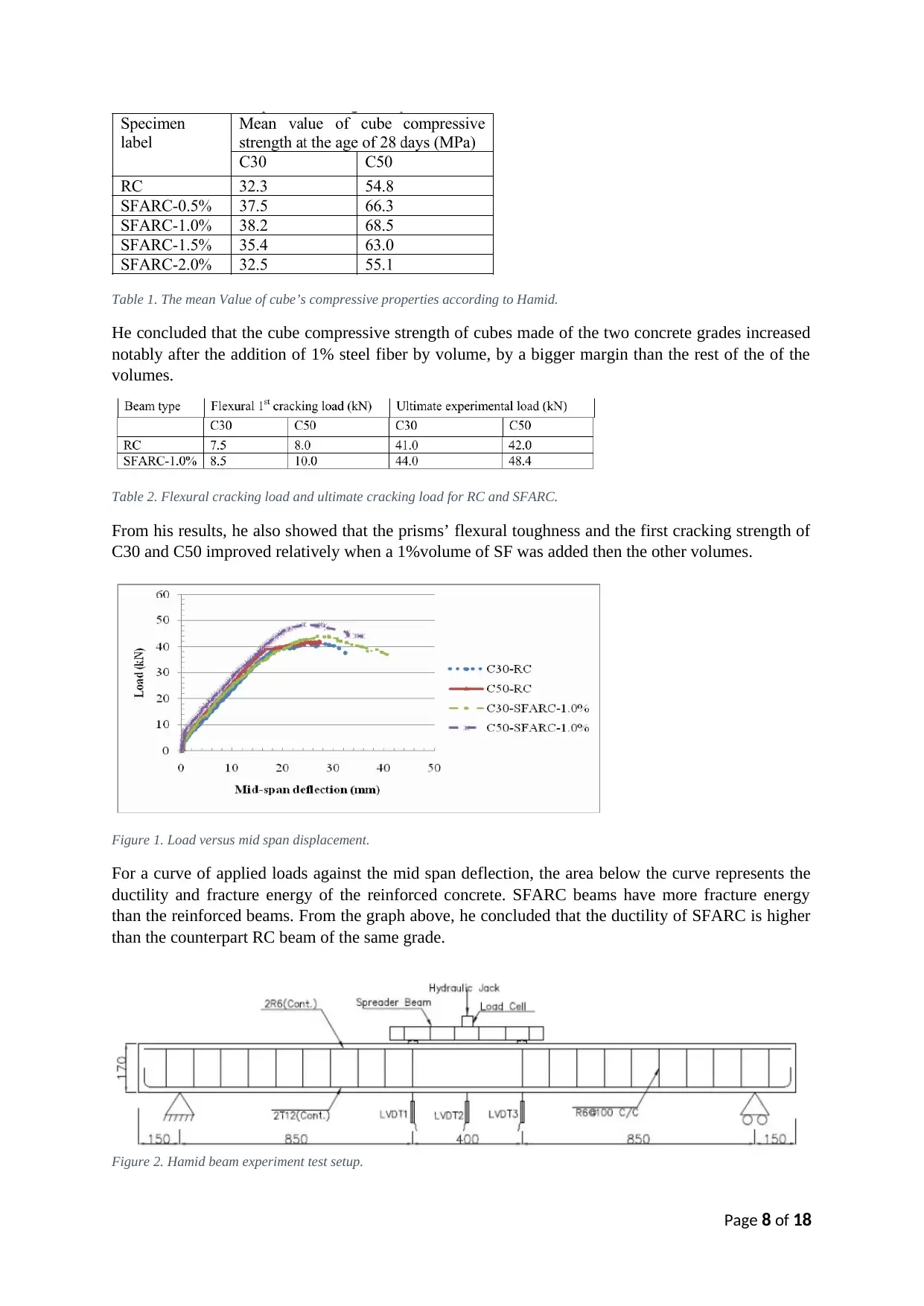

Figure 1. Load versus mid span displacement.

For a curve of applied loads against the mid span deflection, the area below the curve represents the

ductility and fracture energy of the reinforced concrete. SFARC beams have more fracture energy

than the reinforced beams. From the graph above, he concluded that the ductility of SFARC is higher

than the counterpart RC beam of the same grade.

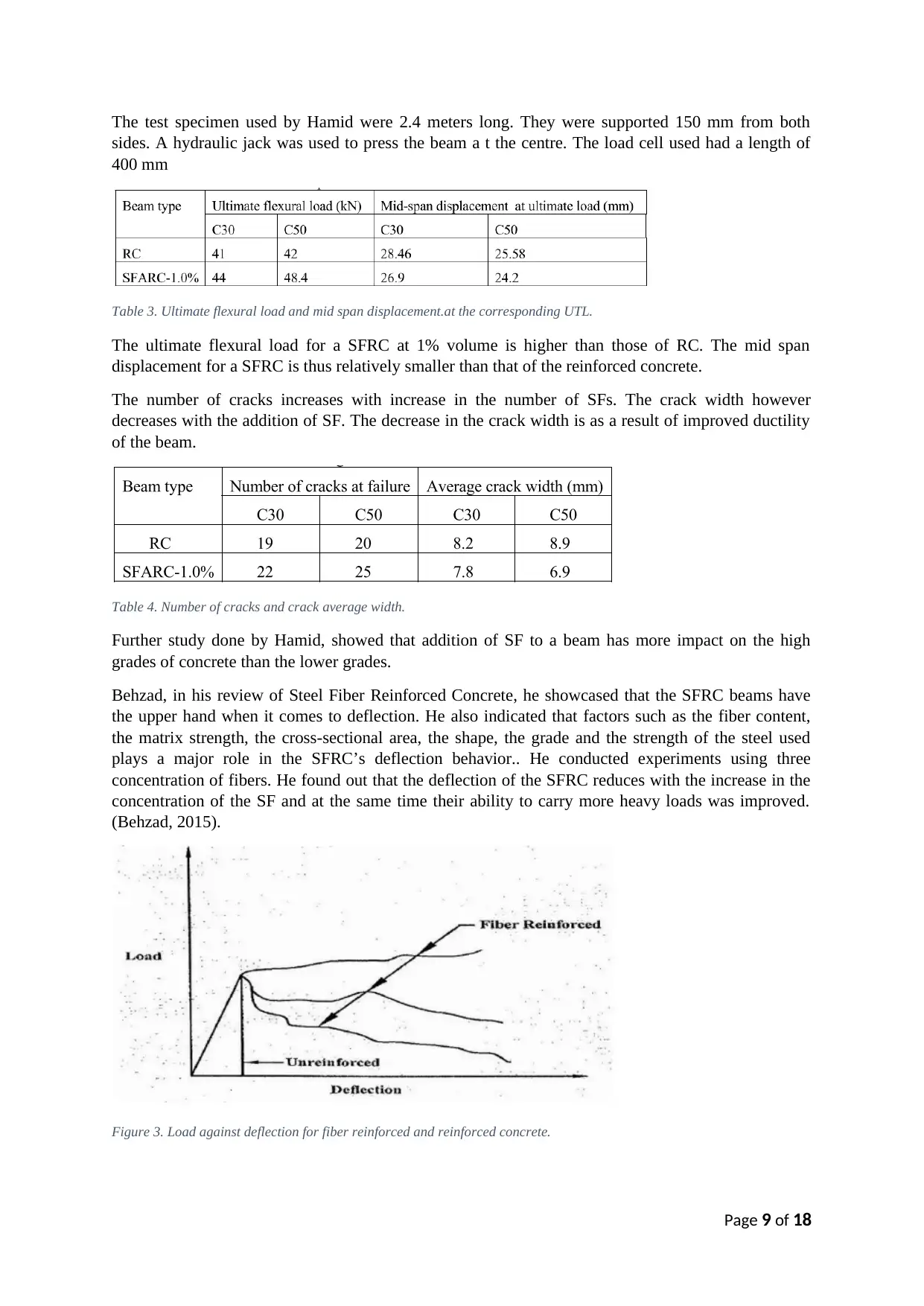

Figure 2. Hamid beam experiment test setup.

Page 8 of 18

He concluded that the cube compressive strength of cubes made of the two concrete grades increased

notably after the addition of 1% steel fiber by volume, by a bigger margin than the rest of the of the

volumes.

Table 2. Flexural cracking load and ultimate cracking load for RC and SFARC.

From his results, he also showed that the prisms’ flexural toughness and the first cracking strength of

C30 and C50 improved relatively when a 1%volume of SF was added then the other volumes.

Figure 1. Load versus mid span displacement.

For a curve of applied loads against the mid span deflection, the area below the curve represents the

ductility and fracture energy of the reinforced concrete. SFARC beams have more fracture energy

than the reinforced beams. From the graph above, he concluded that the ductility of SFARC is higher

than the counterpart RC beam of the same grade.

Figure 2. Hamid beam experiment test setup.

Page 8 of 18

The test specimen used by Hamid were 2.4 meters long. They were supported 150 mm from both

sides. A hydraulic jack was used to press the beam a t the centre. The load cell used had a length of

400 mm

Table 3. Ultimate flexural load and mid span displacement.at the corresponding UTL.

The ultimate flexural load for a SFRC at 1% volume is higher than those of RC. The mid span

displacement for a SFRC is thus relatively smaller than that of the reinforced concrete.

The number of cracks increases with increase in the number of SFs. The crack width however

decreases with the addition of SF. The decrease in the crack width is as a result of improved ductility

of the beam.

Table 4. Number of cracks and crack average width.

Further study done by Hamid, showed that addition of SF to a beam has more impact on the high

grades of concrete than the lower grades.

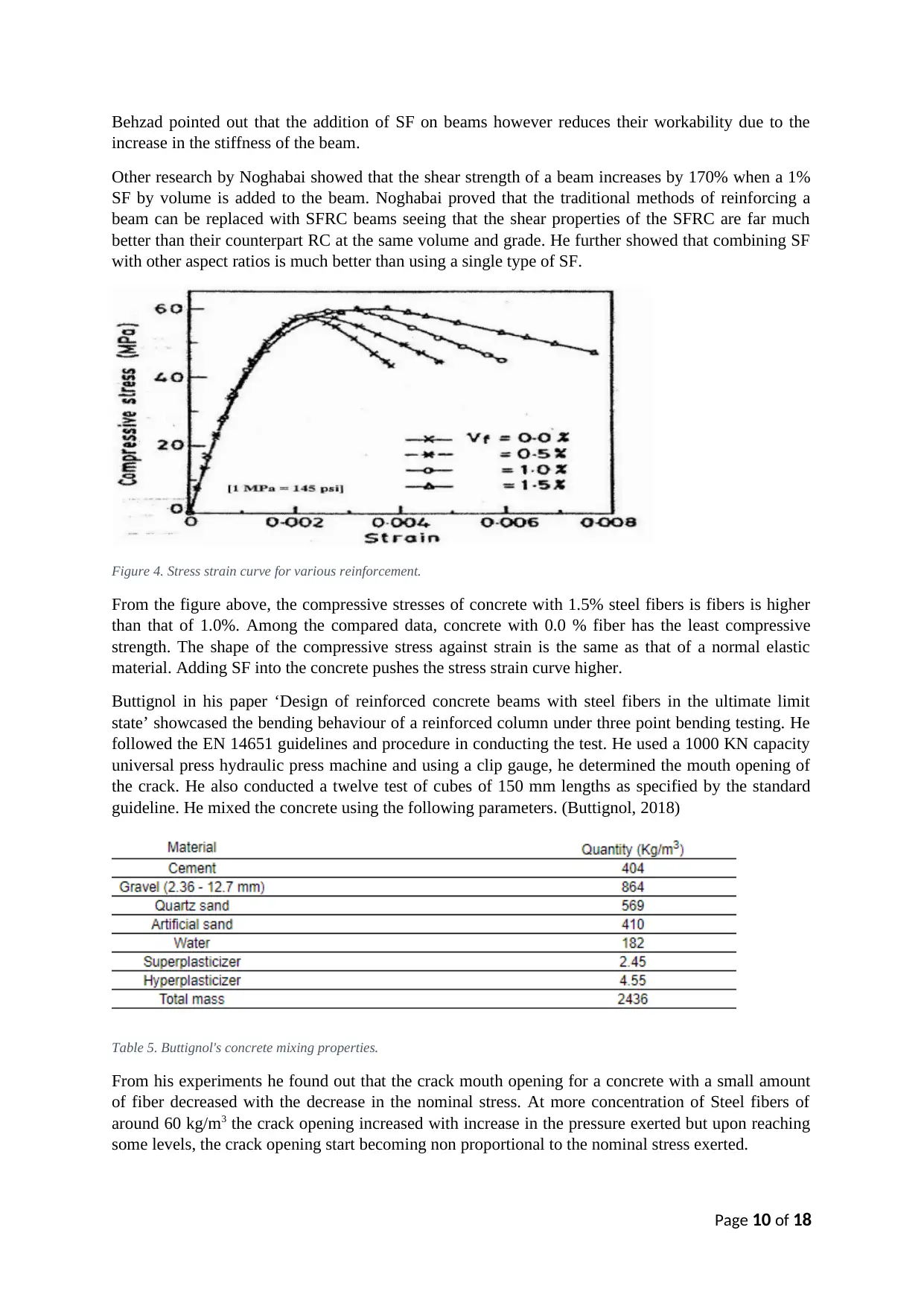

Behzad, in his review of Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete, he showcased that the SFRC beams have

the upper hand when it comes to deflection. He also indicated that factors such as the fiber content,

the matrix strength, the cross-sectional area, the shape, the grade and the strength of the steel used

plays a major role in the SFRC’s deflection behavior.. He conducted experiments using three

concentration of fibers. He found out that the deflection of the SFRC reduces with the increase in the

concentration of the SF and at the same time their ability to carry more heavy loads was improved.

(Behzad, 2015).

Figure 3. Load against deflection for fiber reinforced and reinforced concrete.

Page 9 of 18

sides. A hydraulic jack was used to press the beam a t the centre. The load cell used had a length of

400 mm

Table 3. Ultimate flexural load and mid span displacement.at the corresponding UTL.

The ultimate flexural load for a SFRC at 1% volume is higher than those of RC. The mid span

displacement for a SFRC is thus relatively smaller than that of the reinforced concrete.

The number of cracks increases with increase in the number of SFs. The crack width however

decreases with the addition of SF. The decrease in the crack width is as a result of improved ductility

of the beam.

Table 4. Number of cracks and crack average width.

Further study done by Hamid, showed that addition of SF to a beam has more impact on the high

grades of concrete than the lower grades.

Behzad, in his review of Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete, he showcased that the SFRC beams have

the upper hand when it comes to deflection. He also indicated that factors such as the fiber content,

the matrix strength, the cross-sectional area, the shape, the grade and the strength of the steel used

plays a major role in the SFRC’s deflection behavior.. He conducted experiments using three

concentration of fibers. He found out that the deflection of the SFRC reduces with the increase in the

concentration of the SF and at the same time their ability to carry more heavy loads was improved.

(Behzad, 2015).

Figure 3. Load against deflection for fiber reinforced and reinforced concrete.

Page 9 of 18

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Behzad pointed out that the addition of SF on beams however reduces their workability due to the

increase in the stiffness of the beam.

Other research by Noghabai showed that the shear strength of a beam increases by 170% when a 1%

SF by volume is added to the beam. Noghabai proved that the traditional methods of reinforcing a

beam can be replaced with SFRC beams seeing that the shear properties of the SFRC are far much

better than their counterpart RC at the same volume and grade. He further showed that combining SF

with other aspect ratios is much better than using a single type of SF.

Figure 4. Stress strain curve for various reinforcement.

From the figure above, the compressive stresses of concrete with 1.5% steel fibers is fibers is higher

than that of 1.0%. Among the compared data, concrete with 0.0 % fiber has the least compressive

strength. The shape of the compressive stress against strain is the same as that of a normal elastic

material. Adding SF into the concrete pushes the stress strain curve higher.

Buttignol in his paper ‘Design of reinforced concrete beams with steel fibers in the ultimate limit

state’ showcased the bending behaviour of a reinforced column under three point bending testing. He

followed the EN 14651 guidelines and procedure in conducting the test. He used a 1000 KN capacity

universal press hydraulic press machine and using a clip gauge, he determined the mouth opening of

the crack. He also conducted a twelve test of cubes of 150 mm lengths as specified by the standard

guideline. He mixed the concrete using the following parameters. (Buttignol, 2018)

Table 5. Buttignol's concrete mixing properties.

From his experiments he found out that the crack mouth opening for a concrete with a small amount

of fiber decreased with the decrease in the nominal stress. At more concentration of Steel fibers of

around 60 kg/m3 the crack opening increased with increase in the pressure exerted but upon reaching

some levels, the crack opening start becoming non proportional to the nominal stress exerted.

Page 10 of 18

increase in the stiffness of the beam.

Other research by Noghabai showed that the shear strength of a beam increases by 170% when a 1%

SF by volume is added to the beam. Noghabai proved that the traditional methods of reinforcing a

beam can be replaced with SFRC beams seeing that the shear properties of the SFRC are far much

better than their counterpart RC at the same volume and grade. He further showed that combining SF

with other aspect ratios is much better than using a single type of SF.

Figure 4. Stress strain curve for various reinforcement.

From the figure above, the compressive stresses of concrete with 1.5% steel fibers is fibers is higher

than that of 1.0%. Among the compared data, concrete with 0.0 % fiber has the least compressive

strength. The shape of the compressive stress against strain is the same as that of a normal elastic

material. Adding SF into the concrete pushes the stress strain curve higher.

Buttignol in his paper ‘Design of reinforced concrete beams with steel fibers in the ultimate limit

state’ showcased the bending behaviour of a reinforced column under three point bending testing. He

followed the EN 14651 guidelines and procedure in conducting the test. He used a 1000 KN capacity

universal press hydraulic press machine and using a clip gauge, he determined the mouth opening of

the crack. He also conducted a twelve test of cubes of 150 mm lengths as specified by the standard

guideline. He mixed the concrete using the following parameters. (Buttignol, 2018)

Table 5. Buttignol's concrete mixing properties.

From his experiments he found out that the crack mouth opening for a concrete with a small amount

of fiber decreased with the decrease in the nominal stress. At more concentration of Steel fibers of

around 60 kg/m3 the crack opening increased with increase in the pressure exerted but upon reaching

some levels, the crack opening start becoming non proportional to the nominal stress exerted.

Page 10 of 18

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

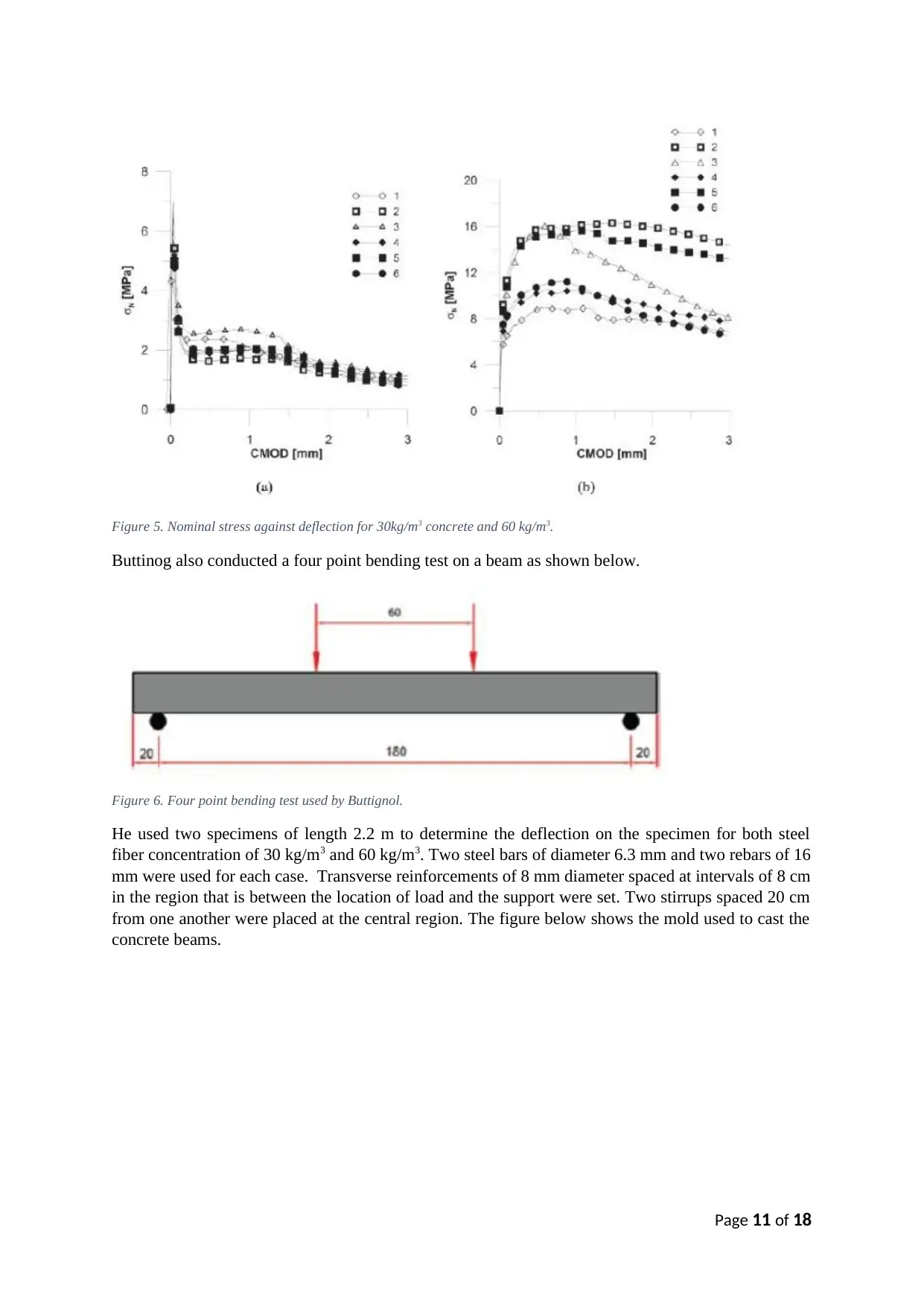

Figure 5. Nominal stress against deflection for 30kg/m3 concrete and 60 kg/m3.

Buttinog also conducted a four point bending test on a beam as shown below.

Figure 6. Four point bending test used by Buttignol.

He used two specimens of length 2.2 m to determine the deflection on the specimen for both steel

fiber concentration of 30 kg/m3 and 60 kg/m3. Two steel bars of diameter 6.3 mm and two rebars of 16

mm were used for each case. Transverse reinforcements of 8 mm diameter spaced at intervals of 8 cm

in the region that is between the location of load and the support were set. Two stirrups spaced 20 cm

from one another were placed at the central region. The figure below shows the mold used to cast the

concrete beams.

Page 11 of 18

Buttinog also conducted a four point bending test on a beam as shown below.

Figure 6. Four point bending test used by Buttignol.

He used two specimens of length 2.2 m to determine the deflection on the specimen for both steel

fiber concentration of 30 kg/m3 and 60 kg/m3. Two steel bars of diameter 6.3 mm and two rebars of 16

mm were used for each case. Transverse reinforcements of 8 mm diameter spaced at intervals of 8 cm

in the region that is between the location of load and the support were set. Two stirrups spaced 20 cm

from one another were placed at the central region. The figure below shows the mold used to cast the

concrete beams.

Page 11 of 18

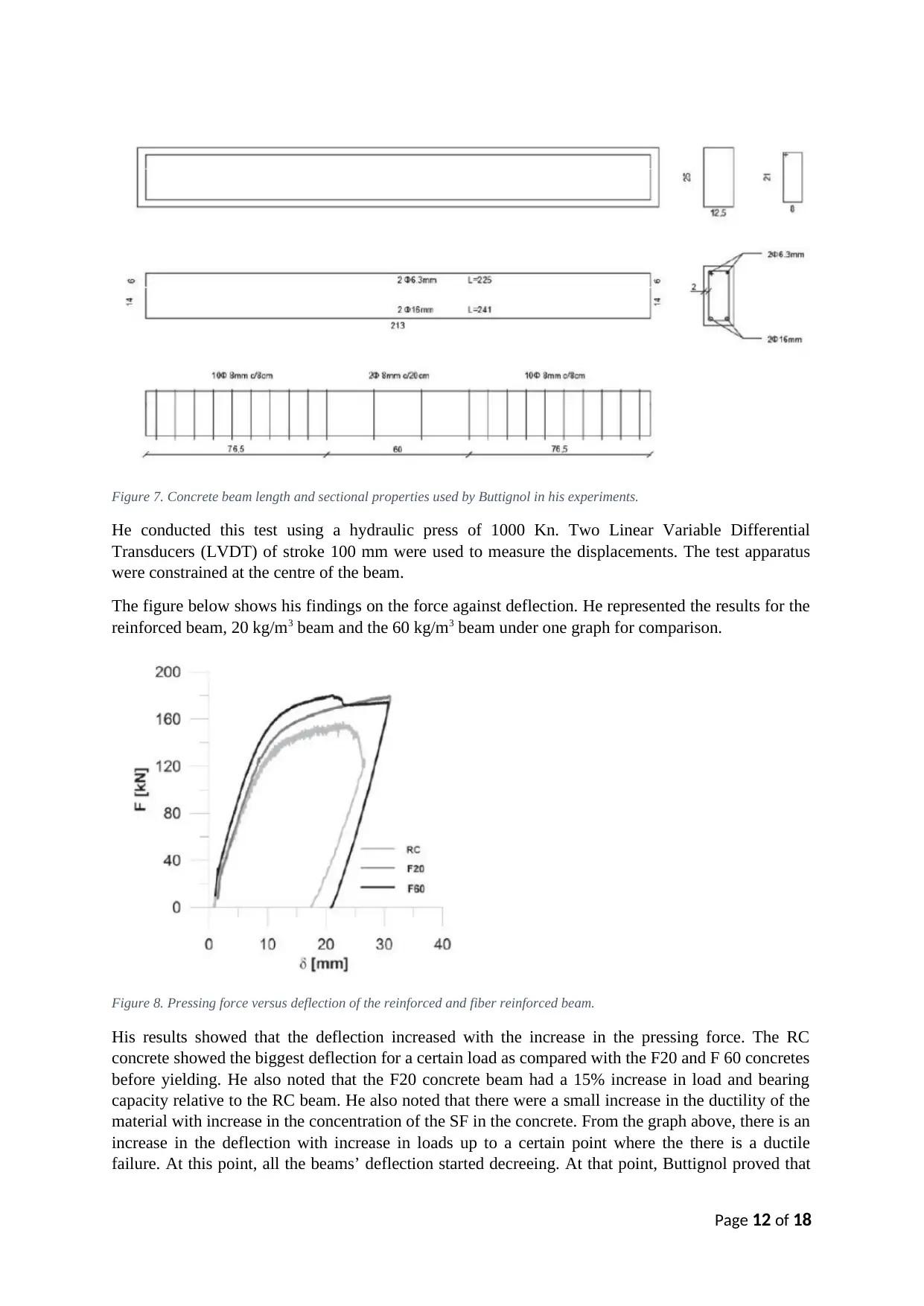

Figure 7. Concrete beam length and sectional properties used by Buttignol in his experiments.

He conducted this test using a hydraulic press of 1000 Kn. Two Linear Variable Differential

Transducers (LVDT) of stroke 100 mm were used to measure the displacements. The test apparatus

were constrained at the centre of the beam.

The figure below shows his findings on the force against deflection. He represented the results for the

reinforced beam, 20 kg/m3 beam and the 60 kg/m3 beam under one graph for comparison.

Figure 8. Pressing force versus deflection of the reinforced and fiber reinforced beam.

His results showed that the deflection increased with the increase in the pressing force. The RC

concrete showed the biggest deflection for a certain load as compared with the F20 and F 60 concretes

before yielding. He also noted that the F20 concrete beam had a 15% increase in load and bearing

capacity relative to the RC beam. He also noted that there were a small increase in the ductility of the

material with increase in the concentration of the SF in the concrete. From the graph above, there is an

increase in the deflection with increase in loads up to a certain point where the there is a ductile

failure. At this point, all the beams’ deflection started decreeing. At that point, Buttignol proved that

Page 12 of 18

He conducted this test using a hydraulic press of 1000 Kn. Two Linear Variable Differential

Transducers (LVDT) of stroke 100 mm were used to measure the displacements. The test apparatus

were constrained at the centre of the beam.

The figure below shows his findings on the force against deflection. He represented the results for the

reinforced beam, 20 kg/m3 beam and the 60 kg/m3 beam under one graph for comparison.

Figure 8. Pressing force versus deflection of the reinforced and fiber reinforced beam.

His results showed that the deflection increased with the increase in the pressing force. The RC

concrete showed the biggest deflection for a certain load as compared with the F20 and F 60 concretes

before yielding. He also noted that the F20 concrete beam had a 15% increase in load and bearing

capacity relative to the RC beam. He also noted that there were a small increase in the ductility of the

material with increase in the concentration of the SF in the concrete. From the graph above, there is an

increase in the deflection with increase in loads up to a certain point where the there is a ductile

failure. At this point, all the beams’ deflection started decreeing. At that point, Buttignol proved that

Page 12 of 18

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 18

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.