Association Between Shift Length, Job Satisfaction, and Quality

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/21

|7

|6865

|158

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a secondary analysis of the RN4Cast study, investigating the relationship between shift length and various outcomes for nurses in English hospitals. The study found that nurses working 12-hour shifts reported lower job satisfaction, poorer quality of care, and higher rates of care left undone compared to those working shorter shifts. The research, conducted across 31 NHS acute hospital Trusts, examined the impact of different shift patterns on nurses' self-reported measures, including job satisfaction, scheduling flexibility, care quality, patient safety, and care left undone. The findings emphasize the negative impact of longer shifts on both nurse well-being and the quality of patient care, supporting the growing international body of evidence. The study highlights the need for further research to optimize 12-hour shifts and mitigate potential risks associated with them, contributing valuable insights into the complex relationship between shift work and healthcare outcomes.

R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E Open Access

Cross-sectionalexamination of the

association between shift length and

hospitalnurses job satisfaction and nurse

reported quality measures

Jane Ball1,2,3 , Tina Day4*

, Trevor Murrells4

, Chiara Dall’Ora1,2

, Anne Marie Rafferty4

, Peter Griffiths1,2

and

Jill Maben4

Abstract

Background:Twenty-four hour nursing care involves shift work including 12-h shifts.England is unusualin

deploying a mix of shift patterns.Internationalevidence on the effects of such shifts is growing.A secondary

analysis of data collected in England exploring outcomes with 12-h shifts examined the association betwee

length,job satisfaction,scheduling flexibility,care quality,patient safety,and care left undone.

Methods:Data were collected from a questionnaire survey of nurses in a sample of English hospitals,conducted as

part of the RN4CAST study,an EU 7th Framework funded study.The sample comprised 31 NHS acute hospitalTrusts

from 401 wards,in 46 acute hospitalsites.Descriptive analysis included frequencies,percentages and mean scores

by shift length,working beyond contracted hours and day or night shift.Multi-levelregression models established

statisticalassociations between shift length and nurse self-reported measures.

Results:Seventy-four percent (1898) of nurses worked a day shift and 26% (670) a night shift.Most Trusts had a

mixture of shifts lengths.Self-reported quality of care was higher amongst nurses working ≤8 h (15.9%) compa

to those working longer hours (20.0 to 21.1%).The odds of poor quality care were 1.64 times higher for nurses

working ≥12 h (OR = 1.64,95% CI1.18–2.28,p = 0.003).

Mean ‘care left undone’scores varied by shift length:3.85 (≤8 h),3.72 (8.01–10.00 h),3.80 (10.01–11.99 h) and were

highest amongst those working ≥12 h (4.23) (p < 0.001).The rate of care left undone was 1.13 times higher for

nurses working ≥12 h (RR = 1.13,95% CI1.06–1.20,p < 0.001).

Job dissatisfaction was higher the longer the shift length:42.9% (≥12 h (OR = 1.51,95% CI1.17–1.95,p = .001);

35.1% (≤8 h) 45.0% (8.01–10.00 h),39.5% (10.01–11.99 h).

Conclusions:Our findings add to the growing international body of evidence reporting that ≥12 shifts are as

with poor ratings of quality of care and higher rates of care left undone.Future research should focus on how 12-h

shifts can be optimised to minimise potential risks.

Keywords: Shift work,12 h shift,Work hours,Care left undone,Quality of health care,Job satisfaction,Patient safety,

England

* Correspondence:tina.day@kcl.ac.uk

4Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery,King’s College

London,James Clerk MaxwellBuilding,57 Waterloo Road,London SE1 8WA,

UK

Fulllist of author information is available at the end of the article

© The Author(s).2017 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

InternationalLicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided you give appropriate credit to the originalauthor(s) and the source,provide a link to

the Creative Commons license,and indicate if changes were made.The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,unless otherwise stated.

Ball et al.BMC Nursing (2017) 16:26

DOI10.1186/s12912-017-0221-7

Cross-sectionalexamination of the

association between shift length and

hospitalnurses job satisfaction and nurse

reported quality measures

Jane Ball1,2,3 , Tina Day4*

, Trevor Murrells4

, Chiara Dall’Ora1,2

, Anne Marie Rafferty4

, Peter Griffiths1,2

and

Jill Maben4

Abstract

Background:Twenty-four hour nursing care involves shift work including 12-h shifts.England is unusualin

deploying a mix of shift patterns.Internationalevidence on the effects of such shifts is growing.A secondary

analysis of data collected in England exploring outcomes with 12-h shifts examined the association betwee

length,job satisfaction,scheduling flexibility,care quality,patient safety,and care left undone.

Methods:Data were collected from a questionnaire survey of nurses in a sample of English hospitals,conducted as

part of the RN4CAST study,an EU 7th Framework funded study.The sample comprised 31 NHS acute hospitalTrusts

from 401 wards,in 46 acute hospitalsites.Descriptive analysis included frequencies,percentages and mean scores

by shift length,working beyond contracted hours and day or night shift.Multi-levelregression models established

statisticalassociations between shift length and nurse self-reported measures.

Results:Seventy-four percent (1898) of nurses worked a day shift and 26% (670) a night shift.Most Trusts had a

mixture of shifts lengths.Self-reported quality of care was higher amongst nurses working ≤8 h (15.9%) compa

to those working longer hours (20.0 to 21.1%).The odds of poor quality care were 1.64 times higher for nurses

working ≥12 h (OR = 1.64,95% CI1.18–2.28,p = 0.003).

Mean ‘care left undone’scores varied by shift length:3.85 (≤8 h),3.72 (8.01–10.00 h),3.80 (10.01–11.99 h) and were

highest amongst those working ≥12 h (4.23) (p < 0.001).The rate of care left undone was 1.13 times higher for

nurses working ≥12 h (RR = 1.13,95% CI1.06–1.20,p < 0.001).

Job dissatisfaction was higher the longer the shift length:42.9% (≥12 h (OR = 1.51,95% CI1.17–1.95,p = .001);

35.1% (≤8 h) 45.0% (8.01–10.00 h),39.5% (10.01–11.99 h).

Conclusions:Our findings add to the growing international body of evidence reporting that ≥12 shifts are as

with poor ratings of quality of care and higher rates of care left undone.Future research should focus on how 12-h

shifts can be optimised to minimise potential risks.

Keywords: Shift work,12 h shift,Work hours,Care left undone,Quality of health care,Job satisfaction,Patient safety,

England

* Correspondence:tina.day@kcl.ac.uk

4Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery,King’s College

London,James Clerk MaxwellBuilding,57 Waterloo Road,London SE1 8WA,

UK

Fulllist of author information is available at the end of the article

© The Author(s).2017 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

InternationalLicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and

reproduction in any medium,provided you give appropriate credit to the originalauthor(s) and the source,provide a link to

the Creative Commons license,and indicate if changes were made.The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,unless otherwise stated.

Ball et al.BMC Nursing (2017) 16:26

DOI10.1186/s12912-017-0221-7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Background

This study was a secondary analysis of data collected in

England as part of the RN4Cast study,exploring the risk

of negative outcomes with nurses working 12 h shifts.

Specifically,we sought to establish whether there was an

association between shift length and reported outcomes:

nurse job satisfaction,satisfaction with work flexibility,

care quality,patientsafety,and care leftundone.This

paperis based on a reportpublished to the research

funder,NHS England [1].This report is available online

via the web,but was neither peer reviewed nor widely

disseminated and should be viewed as a reportto the

funder and not an academic publication.

The provision of 24-h nursing care involves shift work,

including “long days” or 12-h shifts [2,3]. Historically,

shift patterns were based on three eight-hour shifts per

day [4,5] but over the past20 years there has been a

tendency to move towards the 12-h shift[6, 7]. In the

last few decades,an increasing number of NHS hospitals

in England started to utilise 12-h shifts in the belief that

it is a more costeffective way ofproviding 24-h care,

with fewer overlaps between shifts,offering greater con-

tinuity of staffingover day and night [8]. However,

claims offinancialbenefits of12-h shifts by NHS Trust

Boards are made in the absence of economic evaluations.

Furthermore,some nurses preferto work longerdaily

hourswith fewershifts,giving them greaterflexibility

and more days away from work [9–11].As the majority

of the nursing workforce is female,this may also make it

easier to balance work and personalresponsibilities but

long days may carry hidden costs for staffand patients

[11,12].

However,some employers are increasingly concerned

over potential threats to patient safety and quality of care

and are choosing to revert to eight-hour shifts [13,14].

Although the handover period has been criticised for

being unproductive,with no formal ‘overlap’,12-h shifts

can have a negative impacton opportunities for ward

meetings,teaching,mentorship,teambuilding and re-

search [15,16]. A study by Stimpfeland colleagues

found that nurses who worked shifts of12-h or longer

were significantly more likely to reportpoor quality

care and poor patientsafety when compared to those

working eight-hour shifts [17].Furthermore,a study in-

cluding the patients’perspective reported lower satis-

faction with care in hospitals where staff worked longer

shifts[18].A recent systematic review oferror rates

among nurses found evidence ofa higher risk ofmis-

takes when working a 12 h shiftcompared to shorter

shifts (mostof the studies used 8 and 12 h as cut-off

points) [19].

The shift length argument has been explored by other

occupationalsectorsthan nursing and expertsbelieve

thatfatigue associated with long shifts played a major

role in the unfolding of disasters such as the Chernobyl

nuclearaccident,Three Mile Island incidentand the

grounding of the Exxon Valdez [20] A systematic review

by Smith and colleagues compared eight and 12-h shifts

across a broad range ofindustries and concluded that

working longershiftswithoutsufficientrest between

shifts may increase fatigue and,therefore,pose a threat

to safety[21]. However,researchbeyondhealth is

equivocaland some studies have found little differences

in terms ofcost or productivity [22] or levels offatigue

[23] by shift length.

In nursing,Geiger-Brown and Trinkoffcollated evi-

dence on 12-h shifts and concluded that long shifts are

unsafe for both patients,in terms ofmedication errors

and for nurses,who are at greater risk of musculoskeletal

diseases,needle stick injuries and drowsy driving behav-

iour [13].Estabrooks and colleagues reviewed 12 studies

comparing the effect of eight and 12-h shifts on quality of

care and health care provider outcomes. They found insuf-

ficient evidence to conclude that shift length had an effect

on patient or healthcare outcomes [4].

Two large European cross sectionalstudies of31,627

registered nurses concluded that those working shifts of

12 h or longer were more likely to report poor quality of

care,poor patientsafety,and higher rates ofcare left

undone [24]and higherlevelsof job dissatisfaction,

burnoutand intention to leave [25],when compared

with nurses working 8 h or shorter shifts.

Harris et al. reviewed 85 studiespublished between

1973 and 2014 according to five broad themes:‘risks to

patients’,‘patientexperience’,‘risks to staff ’,‘staffexperi-

ence’and ‘impacton organisationalwork’.The review

concluded thatthe evidence ofany clear effectof 12-h

shifts is inconsistent in outcomes and study design [26].

Dall’Ora etal’sscoping review ofthe effectof shift

work on employees’performance and well-being synthe-

sised shiftpatterns across allsectors,not just nursing.

Although some large scale multicentre studies showed

that 12 h shifts are associated with worse staffand pa-

tient outcomes,the authors concluded that most studies

evaluated one single characteristic and failed to take ac-

count ofthe many complex facets ofshift work.It was

not therefore possible to draw firm conclusions as stud-

ies were often confounded by extraneous variables [27].

Currentknowledge showsthat widespread variation

exists in shift length across the EU. Recent analysis of data

from 12 EU countries (31,627 nurses in 2170 medical/sur-

gicalunits within 487 hospitals) explored variation in the

shiftlength nurses work between and within countries,

and within hospitals [24].Variation in typicalshift length

has been observed,with most countries presenting a clear

8 or 12 h shift pattern;England is unusual in presenting a

mixed economy in shiftpatterns with 32% ofday shifts

and 36% of night shifts lasting 12 h or more making it a

Ball et al.BMC Nursing (2017) 16:26 Page 2 of 7

This study was a secondary analysis of data collected in

England as part of the RN4Cast study,exploring the risk

of negative outcomes with nurses working 12 h shifts.

Specifically,we sought to establish whether there was an

association between shift length and reported outcomes:

nurse job satisfaction,satisfaction with work flexibility,

care quality,patientsafety,and care leftundone.This

paperis based on a reportpublished to the research

funder,NHS England [1].This report is available online

via the web,but was neither peer reviewed nor widely

disseminated and should be viewed as a reportto the

funder and not an academic publication.

The provision of 24-h nursing care involves shift work,

including “long days” or 12-h shifts [2,3]. Historically,

shift patterns were based on three eight-hour shifts per

day [4,5] but over the past20 years there has been a

tendency to move towards the 12-h shift[6, 7]. In the

last few decades,an increasing number of NHS hospitals

in England started to utilise 12-h shifts in the belief that

it is a more costeffective way ofproviding 24-h care,

with fewer overlaps between shifts,offering greater con-

tinuity of staffingover day and night [8]. However,

claims offinancialbenefits of12-h shifts by NHS Trust

Boards are made in the absence of economic evaluations.

Furthermore,some nurses preferto work longerdaily

hourswith fewershifts,giving them greaterflexibility

and more days away from work [9–11].As the majority

of the nursing workforce is female,this may also make it

easier to balance work and personalresponsibilities but

long days may carry hidden costs for staffand patients

[11,12].

However,some employers are increasingly concerned

over potential threats to patient safety and quality of care

and are choosing to revert to eight-hour shifts [13,14].

Although the handover period has been criticised for

being unproductive,with no formal ‘overlap’,12-h shifts

can have a negative impacton opportunities for ward

meetings,teaching,mentorship,teambuilding and re-

search [15,16]. A study by Stimpfeland colleagues

found that nurses who worked shifts of12-h or longer

were significantly more likely to reportpoor quality

care and poor patientsafety when compared to those

working eight-hour shifts [17].Furthermore,a study in-

cluding the patients’perspective reported lower satis-

faction with care in hospitals where staff worked longer

shifts[18].A recent systematic review oferror rates

among nurses found evidence ofa higher risk ofmis-

takes when working a 12 h shiftcompared to shorter

shifts (mostof the studies used 8 and 12 h as cut-off

points) [19].

The shift length argument has been explored by other

occupationalsectorsthan nursing and expertsbelieve

thatfatigue associated with long shifts played a major

role in the unfolding of disasters such as the Chernobyl

nuclearaccident,Three Mile Island incidentand the

grounding of the Exxon Valdez [20] A systematic review

by Smith and colleagues compared eight and 12-h shifts

across a broad range ofindustries and concluded that

working longershiftswithoutsufficientrest between

shifts may increase fatigue and,therefore,pose a threat

to safety[21]. However,researchbeyondhealth is

equivocaland some studies have found little differences

in terms ofcost or productivity [22] or levels offatigue

[23] by shift length.

In nursing,Geiger-Brown and Trinkoffcollated evi-

dence on 12-h shifts and concluded that long shifts are

unsafe for both patients,in terms ofmedication errors

and for nurses,who are at greater risk of musculoskeletal

diseases,needle stick injuries and drowsy driving behav-

iour [13].Estabrooks and colleagues reviewed 12 studies

comparing the effect of eight and 12-h shifts on quality of

care and health care provider outcomes. They found insuf-

ficient evidence to conclude that shift length had an effect

on patient or healthcare outcomes [4].

Two large European cross sectionalstudies of31,627

registered nurses concluded that those working shifts of

12 h or longer were more likely to report poor quality of

care,poor patientsafety,and higher rates ofcare left

undone [24]and higherlevelsof job dissatisfaction,

burnoutand intention to leave [25],when compared

with nurses working 8 h or shorter shifts.

Harris et al. reviewed 85 studiespublished between

1973 and 2014 according to five broad themes:‘risks to

patients’,‘patientexperience’,‘risks to staff ’,‘staffexperi-

ence’and ‘impacton organisationalwork’.The review

concluded thatthe evidence ofany clear effectof 12-h

shifts is inconsistent in outcomes and study design [26].

Dall’Ora etal’sscoping review ofthe effectof shift

work on employees’performance and well-being synthe-

sised shiftpatterns across allsectors,not just nursing.

Although some large scale multicentre studies showed

that 12 h shifts are associated with worse staffand pa-

tient outcomes,the authors concluded that most studies

evaluated one single characteristic and failed to take ac-

count ofthe many complex facets ofshift work.It was

not therefore possible to draw firm conclusions as stud-

ies were often confounded by extraneous variables [27].

Currentknowledge showsthat widespread variation

exists in shift length across the EU. Recent analysis of data

from 12 EU countries (31,627 nurses in 2170 medical/sur-

gicalunits within 487 hospitals) explored variation in the

shiftlength nurses work between and within countries,

and within hospitals [24].Variation in typicalshift length

has been observed,with most countries presenting a clear

8 or 12 h shift pattern;England is unusual in presenting a

mixed economy in shiftpatterns with 32% ofday shifts

and 36% of night shifts lasting 12 h or more making it a

Ball et al.BMC Nursing (2017) 16:26 Page 2 of 7

‘naturallaboratory’for examining the effect of such vari-

ation on outcomes [24].

Data on nurses’work patterns,including their working

hours are notroutinely collected in the UK.However,

analysisof data collected through aseriesof cross-

sectionalsurveys ofnurses’employment in the UK indi-

cate that there has been a steep increase in the prevalence

of nurses working long shifts (12-h plus) in NHS hospitals,

from 31% in 2005 to 52% in 2009 [1].

Methods

We used data from a survey of nurses in a random sample

of English hospitals,conducted as partof the RN4Cast

study,an EU 7th Framework funded study of the nursing

workforcecovering12 EU countriesand threeinter-

nationalpartner countries beyond Europe [1].The study

soughtto examine the relationship between nursing in-

puts and patientoutcomes,whilstcontrolling for other

potentially confounding factors.The study included a sur-

vey of registered nurses in medicaland surgicalwards in

England.The sample comprised 31 NHS acute hospital

Trusts (administrative groupings ofhospitals)from 400

wards,in 46 acute hospitalsites.The questionnaire cov-

ered:practice environment,staffing and patient numbers

on the lastshift worked,quality and safety measures,

frequency ofadverse events,care left undone,job dis-

satisfaction and working hours (including shift length).

The survey was administered in spring/summer of2010,

2917 registered nurses responded achieving an estimated

response rate of39%.Ethicalapprovalfor the RN4Cast

study in England was sought and gained from the National

Research Ethics Committee (Ref:09/H0808/69) and per-

missions acquired for the research to be undertaken at

each hospital. Informed consent was obtained from partic-

ipants by completion of the questionnaire,as approved by

the ethics committee.

Measures

Five self-report measures representing care quality,safety

and job and work schedule flexibility satisfaction were

drawn from the survey.Four were converted into dichot-

omous (binomial) variables: poor quality of care nurse rat-

ing (poor/fair),poor patientsafety rating (failing/poor),

not satisfied with job (very dissatisfied/a little dissatisfied)

and not satisfied with work schedule flexibility (very dis-

satisfied/a little dissatisfied).A fifth measure ofcare left

undone was created from a list of 13 activities where re-

spondents were asked:‘On your most recent shift,which

of the following activities were necessary but left undone

because you lacked the time to complete them’. The num-

ber of activities leftundone was counted to produce a

score out of 13.

Analysis

Descriptive analysis was undertaken,measures were de-

scribed using frequencies,percentages and mean scores

(care left undone with 95% confidence intervals) by shift

length,working beyond contracted hours and day (in-

cluding afternoon and evening) or night shift,and a box

plot of shift length by day or night shift.Multi-levelre-

gression modelswere used to establish whetherthere

were statisticalassociations between shiftlength and a

number ofnurse self-reported measures ofcare quality

and job and work schedule flexibility satisfaction,whilst

accounting for other factors and correcting for cluster-

ing within trustsand wards.The potentialpredictors

identified were:shift length,working beyond contracted

hours,day/night shift,medicalor surgicalunit,patients

per nurse (grouped in patientincrements oftwo),pa-

tients per HCA (Quintiles),full or part-time work,age

(in ten year bands),Trust size,high (or not) technology

trust,teaching (or non-teaching) trust.

A multilevel logistic model was fitted to each of the di-

chotomous measures,and a multilevelPoisson modelto

the numberof activitiesleft undone using IBM SPSS

Version 22 GENLINMIXED.The dependentvariables

poor quality of care nurse rating (poor/fair),poor patient

safety rating (failing/poor),not satisfied with job (very

dissatisfied/a little dissatisfied with work schedule) were

modelled assuming the data were generated from a bino-

mial distribution.The care leftundone score (thirteen

items range 0–13) was modelled assuming the data were

generated from a Poisson distribution.

Each modelincluded random effects for intercepts at

the ward and trust levels.These random effects help to

establish whether significantresidualvariation remains

between trusts and wards (within trusts)in the model,

after the inclusion ofthe predictors,and to enable cor-

rect estimation ofstandard errorsin the presence of

clustering.It was not possible to fit random intercepts at

both trust and ward levels for either poor quality of care

nurse rating or poor patientsafety rating.We dropped

the trustlevelrandom interceptfrom the formerand

the ward levelrandom interceptfrom the latter to

achieve model convergence.

Results

A totalof 2568 nurses (out of2917) provided informa-

tion on the length of their last shift and whether it took

place during the day (morning/afternoon/evening) or at

nightof whom 74% (1898)had worked a day shift and

26% (670)a nightshift(Table 1).Analysis atthe ward

level showed a high degree of variation in day shift dura-

tions between wards in the same hospitals;most Trusts

having a mix of eight hour shifts,12-h shifts,and shifts

of a variety ofother lengths.Few Trusts have a single

Ball et al.BMC Nursing (2017) 16:26 Page 3 of 7

ation on outcomes [24].

Data on nurses’work patterns,including their working

hours are notroutinely collected in the UK.However,

analysisof data collected through aseriesof cross-

sectionalsurveys ofnurses’employment in the UK indi-

cate that there has been a steep increase in the prevalence

of nurses working long shifts (12-h plus) in NHS hospitals,

from 31% in 2005 to 52% in 2009 [1].

Methods

We used data from a survey of nurses in a random sample

of English hospitals,conducted as partof the RN4Cast

study,an EU 7th Framework funded study of the nursing

workforcecovering12 EU countriesand threeinter-

nationalpartner countries beyond Europe [1].The study

soughtto examine the relationship between nursing in-

puts and patientoutcomes,whilstcontrolling for other

potentially confounding factors.The study included a sur-

vey of registered nurses in medicaland surgicalwards in

England.The sample comprised 31 NHS acute hospital

Trusts (administrative groupings ofhospitals)from 400

wards,in 46 acute hospitalsites.The questionnaire cov-

ered:practice environment,staffing and patient numbers

on the lastshift worked,quality and safety measures,

frequency ofadverse events,care left undone,job dis-

satisfaction and working hours (including shift length).

The survey was administered in spring/summer of2010,

2917 registered nurses responded achieving an estimated

response rate of39%.Ethicalapprovalfor the RN4Cast

study in England was sought and gained from the National

Research Ethics Committee (Ref:09/H0808/69) and per-

missions acquired for the research to be undertaken at

each hospital. Informed consent was obtained from partic-

ipants by completion of the questionnaire,as approved by

the ethics committee.

Measures

Five self-report measures representing care quality,safety

and job and work schedule flexibility satisfaction were

drawn from the survey.Four were converted into dichot-

omous (binomial) variables: poor quality of care nurse rat-

ing (poor/fair),poor patientsafety rating (failing/poor),

not satisfied with job (very dissatisfied/a little dissatisfied)

and not satisfied with work schedule flexibility (very dis-

satisfied/a little dissatisfied).A fifth measure ofcare left

undone was created from a list of 13 activities where re-

spondents were asked:‘On your most recent shift,which

of the following activities were necessary but left undone

because you lacked the time to complete them’. The num-

ber of activities leftundone was counted to produce a

score out of 13.

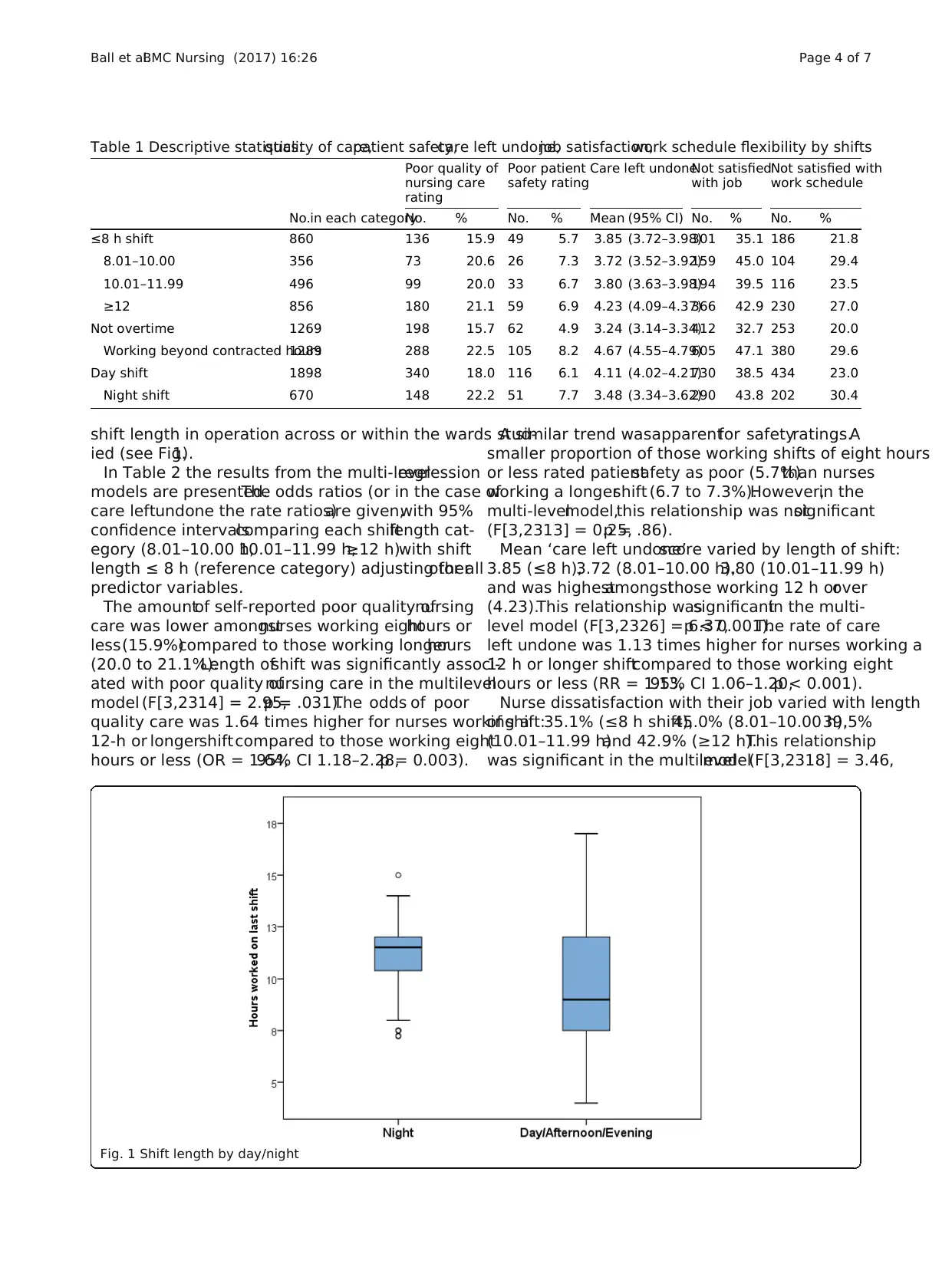

Analysis

Descriptive analysis was undertaken,measures were de-

scribed using frequencies,percentages and mean scores

(care left undone with 95% confidence intervals) by shift

length,working beyond contracted hours and day (in-

cluding afternoon and evening) or night shift,and a box

plot of shift length by day or night shift.Multi-levelre-

gression modelswere used to establish whetherthere

were statisticalassociations between shiftlength and a

number ofnurse self-reported measures ofcare quality

and job and work schedule flexibility satisfaction,whilst

accounting for other factors and correcting for cluster-

ing within trustsand wards.The potentialpredictors

identified were:shift length,working beyond contracted

hours,day/night shift,medicalor surgicalunit,patients

per nurse (grouped in patientincrements oftwo),pa-

tients per HCA (Quintiles),full or part-time work,age

(in ten year bands),Trust size,high (or not) technology

trust,teaching (or non-teaching) trust.

A multilevel logistic model was fitted to each of the di-

chotomous measures,and a multilevelPoisson modelto

the numberof activitiesleft undone using IBM SPSS

Version 22 GENLINMIXED.The dependentvariables

poor quality of care nurse rating (poor/fair),poor patient

safety rating (failing/poor),not satisfied with job (very

dissatisfied/a little dissatisfied with work schedule) were

modelled assuming the data were generated from a bino-

mial distribution.The care leftundone score (thirteen

items range 0–13) was modelled assuming the data were

generated from a Poisson distribution.

Each modelincluded random effects for intercepts at

the ward and trust levels.These random effects help to

establish whether significantresidualvariation remains

between trusts and wards (within trusts)in the model,

after the inclusion ofthe predictors,and to enable cor-

rect estimation ofstandard errorsin the presence of

clustering.It was not possible to fit random intercepts at

both trust and ward levels for either poor quality of care

nurse rating or poor patientsafety rating.We dropped

the trustlevelrandom interceptfrom the formerand

the ward levelrandom interceptfrom the latter to

achieve model convergence.

Results

A totalof 2568 nurses (out of2917) provided informa-

tion on the length of their last shift and whether it took

place during the day (morning/afternoon/evening) or at

nightof whom 74% (1898)had worked a day shift and

26% (670)a nightshift(Table 1).Analysis atthe ward

level showed a high degree of variation in day shift dura-

tions between wards in the same hospitals;most Trusts

having a mix of eight hour shifts,12-h shifts,and shifts

of a variety ofother lengths.Few Trusts have a single

Ball et al.BMC Nursing (2017) 16:26 Page 3 of 7

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

shift length in operation across or within the wards stud-

ied (see Fig.1).

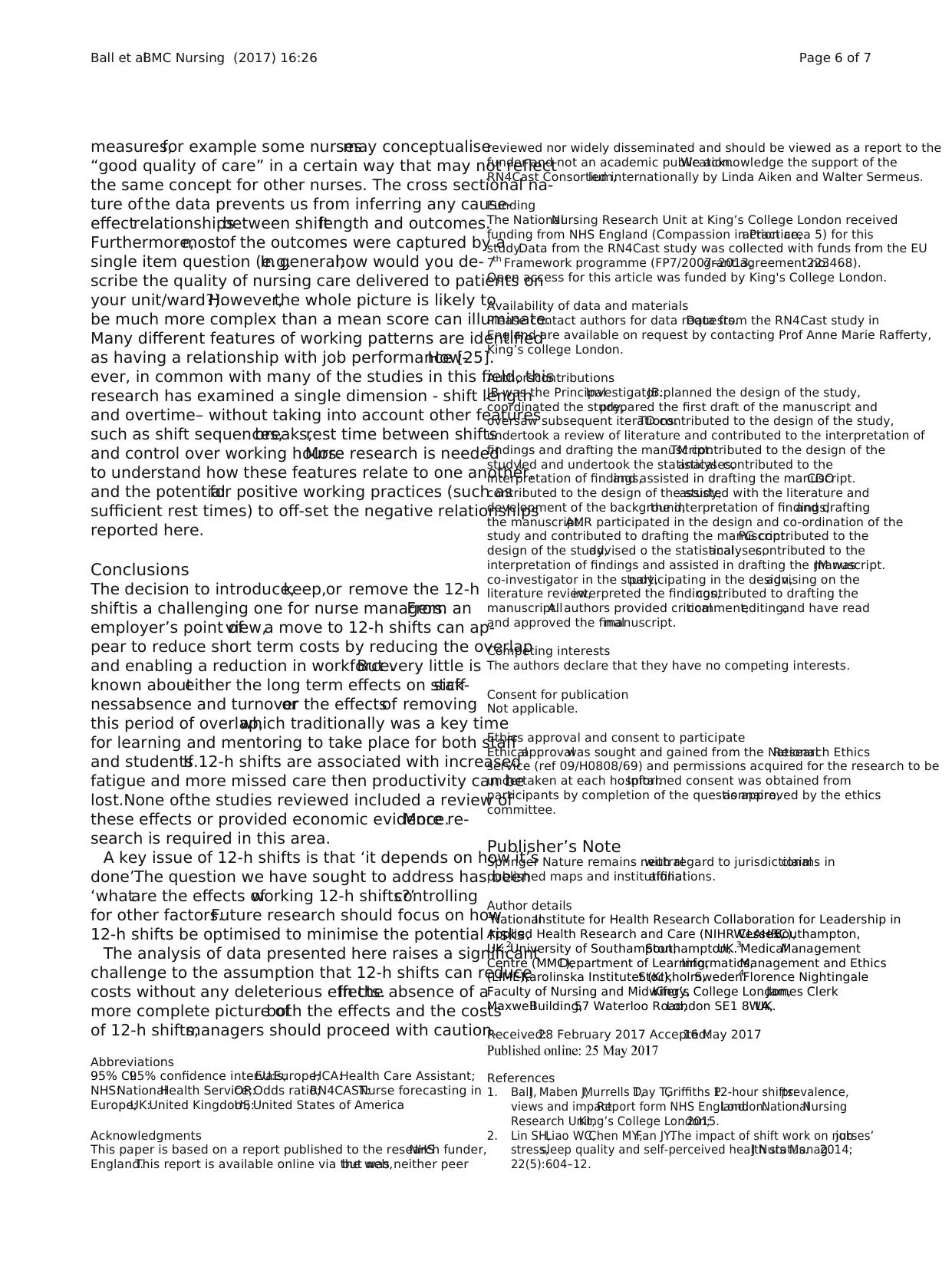

In Table 2 the results from the multi-levelregression

models are presented.The odds ratios (or in the case of

care leftundone the rate ratios)are given,with 95%

confidence intervalscomparing each shiftlength cat-

egory (8.01–10.00 h,10.01–11.99 h,≥12 h)with shift

length ≤ 8 h (reference category) adjusting for allother

predictor variables.

The amountof self-reported poor quality ofnursing

care was lower amongstnurses working eighthours or

less(15.9%)compared to those working longerhours

(20.0 to 21.1%).Length ofshift was significantly associ-

ated with poor quality ofnursing care in the multilevel

model (F[3,2314] = 2.95,p = .031).The odds of poor

quality care was 1.64 times higher for nurses working a

12-h or longershift compared to those working eight

hours or less (OR = 1.64,95% CI 1.18–2.28,p = 0.003).

A similar trend wasapparentfor safetyratings.A

smaller proportion of those working shifts of eight hours

or less rated patientsafety as poor (5.7%)than nurses

working a longershift (6.7 to 7.3%).However,in the

multi-levelmodel,this relationship was notsignificant

(F[3,2313] = 0.25,p = .86).

Mean ‘care left undone’score varied by length of shift:

3.85 (≤8 h),3.72 (8.01–10.00 h),3.80 (10.01–11.99 h)

and was highestamongstthose working 12 h orover

(4.23).This relationship wassignificantin the multi-

level model (F[3,2326] = 6.37,p < 0.001).The rate of care

left undone was 1.13 times higher for nurses working a

12 h or longer shiftcompared to those working eight

hours or less (RR = 1.13,95% CI 1.06–1.20,p < 0.001).

Nurse dissatisfaction with their job varied with length

of shift:35.1% (≤8 h shift),45.0% (8.01–10.00 h),39.5%

(10.01–11.99 h)and 42.9% (≥12 h).This relationship

was significant in the multilevelmodel(F[3,2318] = 3.46,

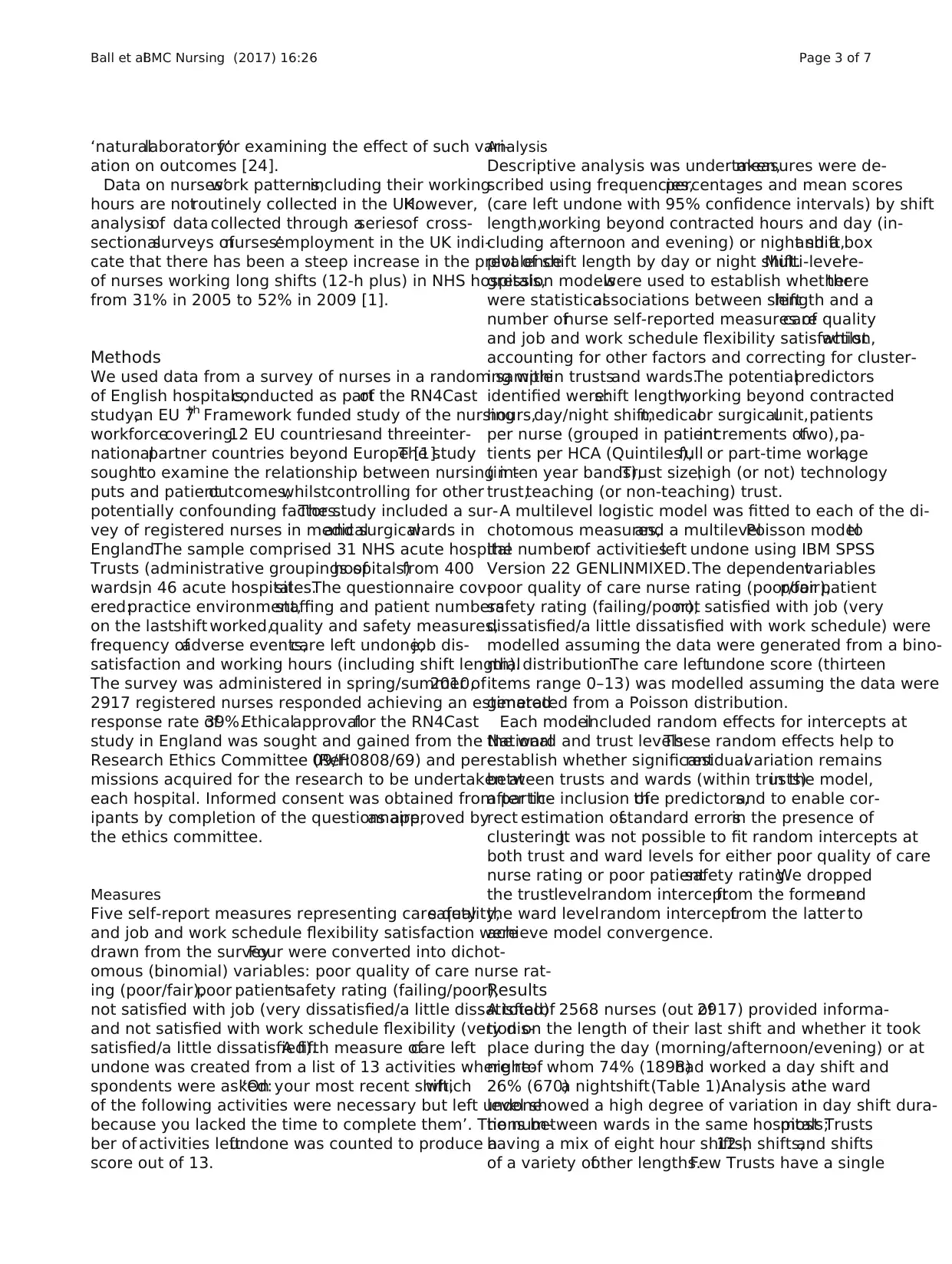

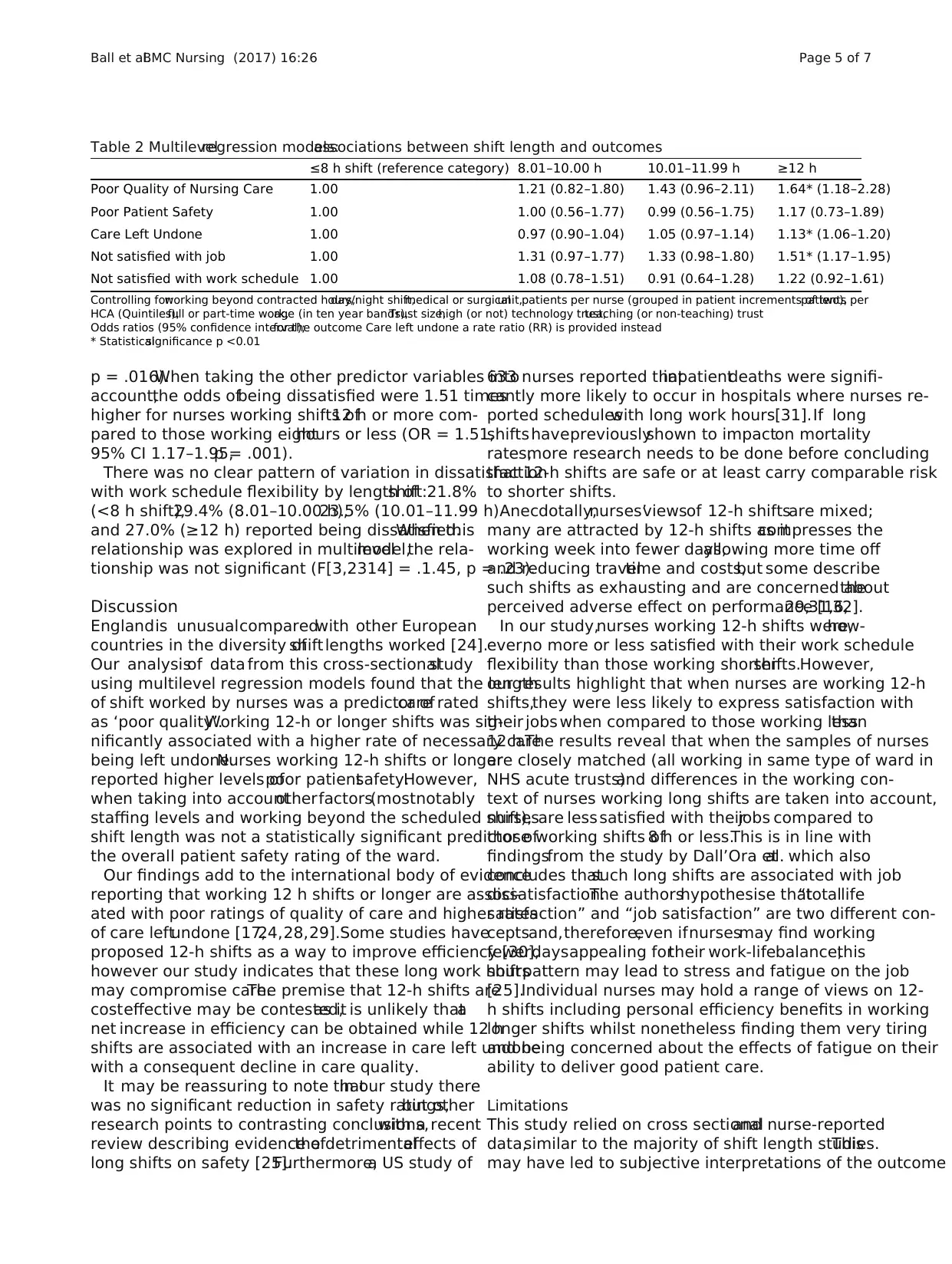

Table 1 Descriptive statistics:quality of care,patient safety,care left undone,job satisfaction,work schedule flexibility by shifts

Poor quality of

nursing care

rating

Poor patient

safety rating

Care left undoneNot satisfied

with job

Not satisfied with

work schedule

No.in each categoryNo. % No. % Mean (95% CI) No. % No. %

≤8 h shift 860 136 15.9 49 5.7 3.85 (3.72–3.98)301 35.1 186 21.8

8.01–10.00 356 73 20.6 26 7.3 3.72 (3.52–3.92)159 45.0 104 29.4

10.01–11.99 496 99 20.0 33 6.7 3.80 (3.63–3.98)194 39.5 116 23.5

≥12 856 180 21.1 59 6.9 4.23 (4.09–4.37)366 42.9 230 27.0

Not overtime 1269 198 15.7 62 4.9 3.24 (3.14–3.34)412 32.7 253 20.0

Working beyond contracted hours1289 288 22.5 105 8.2 4.67 (4.55–4.79)605 47.1 380 29.6

Day shift 1898 340 18.0 116 6.1 4.11 (4.02–4.21)730 38.5 434 23.0

Night shift 670 148 22.2 51 7.7 3.48 (3.34–3.62)290 43.8 202 30.4

Fig. 1 Shift length by day/night

Ball et al.BMC Nursing (2017) 16:26 Page 4 of 7

ied (see Fig.1).

In Table 2 the results from the multi-levelregression

models are presented.The odds ratios (or in the case of

care leftundone the rate ratios)are given,with 95%

confidence intervalscomparing each shiftlength cat-

egory (8.01–10.00 h,10.01–11.99 h,≥12 h)with shift

length ≤ 8 h (reference category) adjusting for allother

predictor variables.

The amountof self-reported poor quality ofnursing

care was lower amongstnurses working eighthours or

less(15.9%)compared to those working longerhours

(20.0 to 21.1%).Length ofshift was significantly associ-

ated with poor quality ofnursing care in the multilevel

model (F[3,2314] = 2.95,p = .031).The odds of poor

quality care was 1.64 times higher for nurses working a

12-h or longershift compared to those working eight

hours or less (OR = 1.64,95% CI 1.18–2.28,p = 0.003).

A similar trend wasapparentfor safetyratings.A

smaller proportion of those working shifts of eight hours

or less rated patientsafety as poor (5.7%)than nurses

working a longershift (6.7 to 7.3%).However,in the

multi-levelmodel,this relationship was notsignificant

(F[3,2313] = 0.25,p = .86).

Mean ‘care left undone’score varied by length of shift:

3.85 (≤8 h),3.72 (8.01–10.00 h),3.80 (10.01–11.99 h)

and was highestamongstthose working 12 h orover

(4.23).This relationship wassignificantin the multi-

level model (F[3,2326] = 6.37,p < 0.001).The rate of care

left undone was 1.13 times higher for nurses working a

12 h or longer shiftcompared to those working eight

hours or less (RR = 1.13,95% CI 1.06–1.20,p < 0.001).

Nurse dissatisfaction with their job varied with length

of shift:35.1% (≤8 h shift),45.0% (8.01–10.00 h),39.5%

(10.01–11.99 h)and 42.9% (≥12 h).This relationship

was significant in the multilevelmodel(F[3,2318] = 3.46,

Table 1 Descriptive statistics:quality of care,patient safety,care left undone,job satisfaction,work schedule flexibility by shifts

Poor quality of

nursing care

rating

Poor patient

safety rating

Care left undoneNot satisfied

with job

Not satisfied with

work schedule

No.in each categoryNo. % No. % Mean (95% CI) No. % No. %

≤8 h shift 860 136 15.9 49 5.7 3.85 (3.72–3.98)301 35.1 186 21.8

8.01–10.00 356 73 20.6 26 7.3 3.72 (3.52–3.92)159 45.0 104 29.4

10.01–11.99 496 99 20.0 33 6.7 3.80 (3.63–3.98)194 39.5 116 23.5

≥12 856 180 21.1 59 6.9 4.23 (4.09–4.37)366 42.9 230 27.0

Not overtime 1269 198 15.7 62 4.9 3.24 (3.14–3.34)412 32.7 253 20.0

Working beyond contracted hours1289 288 22.5 105 8.2 4.67 (4.55–4.79)605 47.1 380 29.6

Day shift 1898 340 18.0 116 6.1 4.11 (4.02–4.21)730 38.5 434 23.0

Night shift 670 148 22.2 51 7.7 3.48 (3.34–3.62)290 43.8 202 30.4

Fig. 1 Shift length by day/night

Ball et al.BMC Nursing (2017) 16:26 Page 4 of 7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

p = .016).When taking the other predictor variables into

account,the odds ofbeing dissatisfied were 1.51 times

higher for nurses working shifts of12 h or more com-

pared to those working eighthours or less (OR = 1.51,

95% CI 1.17–1.95,p = .001).

There was no clear pattern of variation in dissatisfaction

with work schedule flexibility by length ofshift:21.8%

(<8 h shift),29.4% (8.01–10.00 h),23.5% (10.01–11.99 h)

and 27.0% (≥12 h) reported being dissatisfied.When this

relationship was explored in multilevelmodel,the rela-

tionship was not significant (F[3,2314] = .1.45, p = .23).

Discussion

Englandis unusualcomparedwith other European

countries in the diversity ofshiftlengths worked [24].

Our analysisof data from this cross-sectionalstudy

using multilevel regression models found that the length

of shift worked by nurses was a predictor ofcare rated

as ‘poor quality’.Working 12-h or longer shifts was sig-

nificantly associated with a higher rate of necessary care

being left undone.Nurses working 12-h shifts or longer

reported higher levels ofpoor patientsafety.However,

when taking into accountotherfactors(mostnotably

staffing levels and working beyond the scheduled shift),

shift length was not a statistically significant predictor of

the overall patient safety rating of the ward.

Our findings add to the international body of evidence

reporting that working 12 h shifts or longer are associ-

ated with poor ratings of quality of care and higher rates

of care leftundone [17,24,28,29].Some studies have

proposed 12-h shifts as a way to improve efficiency [30],

however our study indicates that these long work hours

may compromise care.The premise that 12-h shifts are

costeffective may be contested,as it is unlikely thata

net increase in efficiency can be obtained while 12 h

shifts are associated with an increase in care left undone

with a consequent decline in care quality.

It may be reassuring to note thatin our study there

was no significant reduction in safety ratings,but other

research points to contrasting conclusions,with a recent

review describing evidence ofthe detrimentaleffects of

long shifts on safety [25].Furthermore,a US study of

633 nurses reported thatinpatientdeaths were signifi-

cantly more likely to occur in hospitals where nurses re-

ported scheduleswith long work hours[31].If long

shifts havepreviouslyshown to impacton mortality

rates,more research needs to be done before concluding

that 12-h shifts are safe or at least carry comparable risk

to shorter shifts.

Anecdotally,nurses’viewsof 12-h shiftsare mixed;

many are attracted by 12-h shifts as itcompresses the

working week into fewer days,allowing more time off

and reducing traveltime and costs,but some describe

such shifts as exhausting and are concerned aboutthe

perceived adverse effect on performance [16,29,31,32].

In our study,nurses working 12-h shifts were,how-

ever,no more or less satisfied with their work schedule

flexibility than those working shortershifts.However,

our results highlight that when nurses are working 12-h

shifts,they were less likely to express satisfaction with

their jobs when compared to those working lessthan

12 h.The results reveal that when the samples of nurses

are closely matched (all working in same type of ward in

NHS acute trusts)and differences in the working con-

text of nurses working long shifts are taken into account,

nursesare less satisfied with theirjobs compared to

those working shifts of8 h or less.This is in line with

findingsfrom the study by Dall’Ora etal. which also

concludes thatsuch long shifts are associated with job

dissatisfaction.The authorshypothesise that“totallife

satisfaction” and “job satisfaction” are two different con-

ceptsand,therefore,even ifnursesmay find working

fewerdaysappealing fortheir work-lifebalance,this

shiftpattern may lead to stress and fatigue on the job

[25].Individual nurses may hold a range of views on 12-

h shifts including personal efficiency benefits in working

longer shifts whilst nonetheless finding them very tiring

and being concerned about the effects of fatigue on their

ability to deliver good patient care.

Limitations

This study relied on cross sectionaland nurse-reported

data,similar to the majority of shift length studies.This

may have led to subjective interpretations of the outcome

Table 2 Multilevelregression models:associations between shift length and outcomes

≤8 h shift (reference category) 8.01–10.00 h 10.01–11.99 h ≥12 h

Poor Quality of Nursing Care 1.00 1.21 (0.82–1.80) 1.43 (0.96–2.11) 1.64* (1.18–2.28)

Poor Patient Safety 1.00 1.00 (0.56–1.77) 0.99 (0.56–1.75) 1.17 (0.73–1.89)

Care Left Undone 1.00 0.97 (0.90–1.04) 1.05 (0.97–1.14) 1.13* (1.06–1.20)

Not satisfied with job 1.00 1.31 (0.97–1.77) 1.33 (0.98–1.80) 1.51* (1.17–1.95)

Not satisfied with work schedule 1.00 1.08 (0.78–1.51) 0.91 (0.64–1.28) 1.22 (0.92–1.61)

Controlling for:working beyond contracted hours,day/night shift,medical or surgicalunit,patients per nurse (grouped in patient increments of two),patients per

HCA (Quintiles),full or part-time work,age (in ten year bands),Trust size,high (or not) technology trust,teaching (or non-teaching) trust

Odds ratios (95% confidence interval);for the outcome Care left undone a rate ratio (RR) is provided instead

* Statisticalsignificance p <0.01

Ball et al.BMC Nursing (2017) 16:26 Page 5 of 7

account,the odds ofbeing dissatisfied were 1.51 times

higher for nurses working shifts of12 h or more com-

pared to those working eighthours or less (OR = 1.51,

95% CI 1.17–1.95,p = .001).

There was no clear pattern of variation in dissatisfaction

with work schedule flexibility by length ofshift:21.8%

(<8 h shift),29.4% (8.01–10.00 h),23.5% (10.01–11.99 h)

and 27.0% (≥12 h) reported being dissatisfied.When this

relationship was explored in multilevelmodel,the rela-

tionship was not significant (F[3,2314] = .1.45, p = .23).

Discussion

Englandis unusualcomparedwith other European

countries in the diversity ofshiftlengths worked [24].

Our analysisof data from this cross-sectionalstudy

using multilevel regression models found that the length

of shift worked by nurses was a predictor ofcare rated

as ‘poor quality’.Working 12-h or longer shifts was sig-

nificantly associated with a higher rate of necessary care

being left undone.Nurses working 12-h shifts or longer

reported higher levels ofpoor patientsafety.However,

when taking into accountotherfactors(mostnotably

staffing levels and working beyond the scheduled shift),

shift length was not a statistically significant predictor of

the overall patient safety rating of the ward.

Our findings add to the international body of evidence

reporting that working 12 h shifts or longer are associ-

ated with poor ratings of quality of care and higher rates

of care leftundone [17,24,28,29].Some studies have

proposed 12-h shifts as a way to improve efficiency [30],

however our study indicates that these long work hours

may compromise care.The premise that 12-h shifts are

costeffective may be contested,as it is unlikely thata

net increase in efficiency can be obtained while 12 h

shifts are associated with an increase in care left undone

with a consequent decline in care quality.

It may be reassuring to note thatin our study there

was no significant reduction in safety ratings,but other

research points to contrasting conclusions,with a recent

review describing evidence ofthe detrimentaleffects of

long shifts on safety [25].Furthermore,a US study of

633 nurses reported thatinpatientdeaths were signifi-

cantly more likely to occur in hospitals where nurses re-

ported scheduleswith long work hours[31].If long

shifts havepreviouslyshown to impacton mortality

rates,more research needs to be done before concluding

that 12-h shifts are safe or at least carry comparable risk

to shorter shifts.

Anecdotally,nurses’viewsof 12-h shiftsare mixed;

many are attracted by 12-h shifts as itcompresses the

working week into fewer days,allowing more time off

and reducing traveltime and costs,but some describe

such shifts as exhausting and are concerned aboutthe

perceived adverse effect on performance [16,29,31,32].

In our study,nurses working 12-h shifts were,how-

ever,no more or less satisfied with their work schedule

flexibility than those working shortershifts.However,

our results highlight that when nurses are working 12-h

shifts,they were less likely to express satisfaction with

their jobs when compared to those working lessthan

12 h.The results reveal that when the samples of nurses

are closely matched (all working in same type of ward in

NHS acute trusts)and differences in the working con-

text of nurses working long shifts are taken into account,

nursesare less satisfied with theirjobs compared to

those working shifts of8 h or less.This is in line with

findingsfrom the study by Dall’Ora etal. which also

concludes thatsuch long shifts are associated with job

dissatisfaction.The authorshypothesise that“totallife

satisfaction” and “job satisfaction” are two different con-

ceptsand,therefore,even ifnursesmay find working

fewerdaysappealing fortheir work-lifebalance,this

shiftpattern may lead to stress and fatigue on the job

[25].Individual nurses may hold a range of views on 12-

h shifts including personal efficiency benefits in working

longer shifts whilst nonetheless finding them very tiring

and being concerned about the effects of fatigue on their

ability to deliver good patient care.

Limitations

This study relied on cross sectionaland nurse-reported

data,similar to the majority of shift length studies.This

may have led to subjective interpretations of the outcome

Table 2 Multilevelregression models:associations between shift length and outcomes

≤8 h shift (reference category) 8.01–10.00 h 10.01–11.99 h ≥12 h

Poor Quality of Nursing Care 1.00 1.21 (0.82–1.80) 1.43 (0.96–2.11) 1.64* (1.18–2.28)

Poor Patient Safety 1.00 1.00 (0.56–1.77) 0.99 (0.56–1.75) 1.17 (0.73–1.89)

Care Left Undone 1.00 0.97 (0.90–1.04) 1.05 (0.97–1.14) 1.13* (1.06–1.20)

Not satisfied with job 1.00 1.31 (0.97–1.77) 1.33 (0.98–1.80) 1.51* (1.17–1.95)

Not satisfied with work schedule 1.00 1.08 (0.78–1.51) 0.91 (0.64–1.28) 1.22 (0.92–1.61)

Controlling for:working beyond contracted hours,day/night shift,medical or surgicalunit,patients per nurse (grouped in patient increments of two),patients per

HCA (Quintiles),full or part-time work,age (in ten year bands),Trust size,high (or not) technology trust,teaching (or non-teaching) trust

Odds ratios (95% confidence interval);for the outcome Care left undone a rate ratio (RR) is provided instead

* Statisticalsignificance p <0.01

Ball et al.BMC Nursing (2017) 16:26 Page 5 of 7

measures,for example some nursesmay conceptualise

“good quality of care” in a certain way that may not reflect

the same concept for other nurses. The cross sectional na-

ture of the data prevents us from inferring any cause-

effectrelationshipsbetween shiftlength and outcomes.

Furthermore,mostof the outcomes were captured by a

single item question (e.g.In general,how would you de-

scribe the quality of nursing care delivered to patients on

your unit/ward?).However,the whole picture is likely to

be much more complex than a mean score can illuminate.

Many different features of working patterns are identified

as having a relationship with job performance [25].How-

ever, in common with many of the studies in this field, this

research has examined a single dimension - shift length

and overtime– without taking into account other features

such as shift sequences,breaks,rest time between shifts

and control over working hours.More research is needed

to understand how these features relate to one another,

and the potentialfor positive working practices (such as

sufficient rest times) to off-set the negative relationships

reported here.

Conclusions

The decision to introduce,keep,or remove the 12-h

shiftis a challenging one for nurse managers.From an

employer’s point ofview,a move to 12-h shifts can ap-

pear to reduce short term costs by reducing the overlap

and enabling a reduction in workforce.But very little is

known abouteither the long term effects on staffsick-

nessabsence and turnoveror the effectsof removing

this period of overlap,which traditionally was a key time

for learning and mentoring to take place for both staff

and students.If 12-h shifts are associated with increased

fatigue and more missed care then productivity can be

lost.None ofthe studies reviewed included a review of

these effects or provided economic evidence.More re-

search is required in this area.

A key issue of 12-h shifts is that ‘it depends on how it’s

done’.The question we have sought to address has been

‘whatare the effects ofworking 12-h shifts?’controlling

for other factors.Future research should focus on how

12-h shifts be optimised to minimise the potential risks.

The analysis of data presented here raises a significant

challenge to the assumption that 12-h shifts can reduce

costs without any deleterious effects.In the absence of a

more complete picture ofboth the effects and the costs

of 12-h shifts,managers should proceed with caution.

Abbreviations

95% CI:95% confidence intervals;EU:Europe;HCA:Health Care Assistant;

NHS:NationalHealth Service;OR:Odds ratio;RN4CAST:Nurse forecasting in

Europe;UK:United Kingdom;US:United States of America

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on a report published to the research funder,NHS

England.This report is available online via the web,but was neither peer

reviewed nor widely disseminated and should be viewed as a report to the

funder and not an academic publication.We acknowledge the support of the

RN4Cast Consortium,led internationally by Linda Aiken and Walter Sermeus.

Funding

The NationalNursing Research Unit at King’s College London received

funding from NHS England (Compassion in Practice,action area 5) for this

study.Data from the RN4Cast study was collected with funds from the EU

7th Framework programme (FP7/2007–2013,grant agreement no.223468).

Open access for this article was funded by King's College London.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact authors for data requests.Data from the RN4Cast study in

England are available on request by contacting Prof Anne Marie Rafferty,

King’s college London.

Authors’contributions

JB was the PrincipalInvestigator.JB:planned the design of the study,

coordinated the study,prepared the first draft of the manuscript and

oversaw subsequent iterations.TD contributed to the design of the study,

undertook a review of literature and contributed to the interpretation of

findings and drafting the manuscript.TM contributed to the design of the

study,led and undertook the statisticalanalyses,contributed to the

interpretation of findings,and assisted in drafting the manuscript.CDO

contributed to the design of the study,assisted with the literature and

development of the background,the interpretation of findings,and drafting

the manuscript.AMR participated in the design and co-ordination of the

study and contributed to drafting the manuscript.PG contributed to the

design of the study,advised o the statisticalanalyses,contributed to the

interpretation of findings and assisted in drafting the manuscript.JM was

co-investigator in the study,participating in the design,advising on the

literature review,interpreted the findings,contributed to drafting the

manuscript.Allauthors provided criticalcomment,editing,and have read

and approved the finalmanuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethicalapprovalwas sought and gained from the NationalResearch Ethics

service (ref 09/H0808/69) and permissions acquired for the research to be

undertaken at each hospital.Informed consent was obtained from

participants by completion of the questionnaire,as approved by the ethics

committee.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutralwith regard to jurisdictionalclaims in

published maps and institutionalaffiliations.

Author details

1NationalInstitute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in

Applied Health Research and Care (NIHR CLAHRC),Wessex,Southampton,

UK.2University of Southampton,Southampton,UK.3MedicalManagement

Centre (MMC),Department of Learning,Informatics,Management and Ethics

(LIME),Karolinska Institutet (KI),Stockholm,Sweden.4Florence Nightingale

Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery,King’s College London,James Clerk

MaxwellBuilding,57 Waterloo Road,London SE1 8WA,UK.

Received:28 February 2017 Accepted:16 May 2017

References

1. BallJ, Maben J,Murrells T,Day T,Griffiths P.12‐hour shifts:prevalence,

views and impact.Report form NHS England.London:NationalNursing

Research Unit,King’s College London;2015.

2. Lin SH,Liao WC,Chen MY,Fan JY.The impact of shift work on nurses’job

stress,sleep quality and self-perceived health status.J Nurs Manag.2014;

22(5):604–12.

Ball et al.BMC Nursing (2017) 16:26 Page 6 of 7

“good quality of care” in a certain way that may not reflect

the same concept for other nurses. The cross sectional na-

ture of the data prevents us from inferring any cause-

effectrelationshipsbetween shiftlength and outcomes.

Furthermore,mostof the outcomes were captured by a

single item question (e.g.In general,how would you de-

scribe the quality of nursing care delivered to patients on

your unit/ward?).However,the whole picture is likely to

be much more complex than a mean score can illuminate.

Many different features of working patterns are identified

as having a relationship with job performance [25].How-

ever, in common with many of the studies in this field, this

research has examined a single dimension - shift length

and overtime– without taking into account other features

such as shift sequences,breaks,rest time between shifts

and control over working hours.More research is needed

to understand how these features relate to one another,

and the potentialfor positive working practices (such as

sufficient rest times) to off-set the negative relationships

reported here.

Conclusions

The decision to introduce,keep,or remove the 12-h

shiftis a challenging one for nurse managers.From an

employer’s point ofview,a move to 12-h shifts can ap-

pear to reduce short term costs by reducing the overlap

and enabling a reduction in workforce.But very little is

known abouteither the long term effects on staffsick-

nessabsence and turnoveror the effectsof removing

this period of overlap,which traditionally was a key time

for learning and mentoring to take place for both staff

and students.If 12-h shifts are associated with increased

fatigue and more missed care then productivity can be

lost.None ofthe studies reviewed included a review of

these effects or provided economic evidence.More re-

search is required in this area.

A key issue of 12-h shifts is that ‘it depends on how it’s

done’.The question we have sought to address has been

‘whatare the effects ofworking 12-h shifts?’controlling

for other factors.Future research should focus on how

12-h shifts be optimised to minimise the potential risks.

The analysis of data presented here raises a significant

challenge to the assumption that 12-h shifts can reduce

costs without any deleterious effects.In the absence of a

more complete picture ofboth the effects and the costs

of 12-h shifts,managers should proceed with caution.

Abbreviations

95% CI:95% confidence intervals;EU:Europe;HCA:Health Care Assistant;

NHS:NationalHealth Service;OR:Odds ratio;RN4CAST:Nurse forecasting in

Europe;UK:United Kingdom;US:United States of America

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on a report published to the research funder,NHS

England.This report is available online via the web,but was neither peer

reviewed nor widely disseminated and should be viewed as a report to the

funder and not an academic publication.We acknowledge the support of the

RN4Cast Consortium,led internationally by Linda Aiken and Walter Sermeus.

Funding

The NationalNursing Research Unit at King’s College London received

funding from NHS England (Compassion in Practice,action area 5) for this

study.Data from the RN4Cast study was collected with funds from the EU

7th Framework programme (FP7/2007–2013,grant agreement no.223468).

Open access for this article was funded by King's College London.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact authors for data requests.Data from the RN4Cast study in

England are available on request by contacting Prof Anne Marie Rafferty,

King’s college London.

Authors’contributions

JB was the PrincipalInvestigator.JB:planned the design of the study,

coordinated the study,prepared the first draft of the manuscript and

oversaw subsequent iterations.TD contributed to the design of the study,

undertook a review of literature and contributed to the interpretation of

findings and drafting the manuscript.TM contributed to the design of the

study,led and undertook the statisticalanalyses,contributed to the

interpretation of findings,and assisted in drafting the manuscript.CDO

contributed to the design of the study,assisted with the literature and

development of the background,the interpretation of findings,and drafting

the manuscript.AMR participated in the design and co-ordination of the

study and contributed to drafting the manuscript.PG contributed to the

design of the study,advised o the statisticalanalyses,contributed to the

interpretation of findings and assisted in drafting the manuscript.JM was

co-investigator in the study,participating in the design,advising on the

literature review,interpreted the findings,contributed to drafting the

manuscript.Allauthors provided criticalcomment,editing,and have read

and approved the finalmanuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethicalapprovalwas sought and gained from the NationalResearch Ethics

service (ref 09/H0808/69) and permissions acquired for the research to be

undertaken at each hospital.Informed consent was obtained from

participants by completion of the questionnaire,as approved by the ethics

committee.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutralwith regard to jurisdictionalclaims in

published maps and institutionalaffiliations.

Author details

1NationalInstitute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in

Applied Health Research and Care (NIHR CLAHRC),Wessex,Southampton,

UK.2University of Southampton,Southampton,UK.3MedicalManagement

Centre (MMC),Department of Learning,Informatics,Management and Ethics

(LIME),Karolinska Institutet (KI),Stockholm,Sweden.4Florence Nightingale

Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery,King’s College London,James Clerk

MaxwellBuilding,57 Waterloo Road,London SE1 8WA,UK.

Received:28 February 2017 Accepted:16 May 2017

References

1. BallJ, Maben J,Murrells T,Day T,Griffiths P.12‐hour shifts:prevalence,

views and impact.Report form NHS England.London:NationalNursing

Research Unit,King’s College London;2015.

2. Lin SH,Liao WC,Chen MY,Fan JY.The impact of shift work on nurses’job

stress,sleep quality and self-perceived health status.J Nurs Manag.2014;

22(5):604–12.

Ball et al.BMC Nursing (2017) 16:26 Page 6 of 7

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3. Trinkoff AM,Le R,Geiger-Brown J,Lipscomb J,Lang G.Longitudinal

relationship of work hours,mandatory overtime,and on-callto

musculoskeletalproblems in nurses.Am J Ind Med.2006;49(11):964–71.

4. Estabrooks CA,Cummings GG,Olivo SA,Squires JE,Giblin C,Simpson N.

Effects of shift length on quality of patient care and health provider

outcomes:systematic review.QualSaf Health Care.2009;18(3):181–8.

5. Ferguson SA,Dawson D.12-h or 8-h shifts? It depends.Sleep Med Rev.

2012;16(6):519–28.

6. McGettrick KS,O’NeillMA.Criticalcare nurses–perceptions of 12-h shifts.

Nurs Crit Care.2006;11(4):188–97.

7. Todd C,Reid N,Robinson G.The quality of nursing care on wards working

eight and twelve hour shifts:a repeated measures study using the

MONITOR index of quality of care.Int J Nurs Stud.1989;26(4):359–68.

8. NHS Evidence.Moving to 12-hour shift patterns:to increase continuity and

reduce costs.London:QIPP,Basingstoke and North Hampshire NHS

Foundation Trust;2010.

9. BallJ, Dall’Ora C,Griffiths P.The 12-hour shift:friend or foe? Nurs Times.

2015;111(6):12–4.

10. Bambra C,Whitehead M,Sowden A,Akers J,Petticrew M.“A hard day’s

night?” The effects of Compressed Working Week interventions on the

health and work-life balance of shift workers:a systematic review.J

EpidemiolCommunity Health.2008;62(9):764–77.

11. Estryn-Behar M,Van der Heijden BI,Group NS.Effects of extended work

shifts on employee fatigue,health,satisfaction,work/family balance,and

patient safety.Work.2012;41 Suppl1:4283–90.

12. Josten EJ,Ng ATJE,Thierry H.The effects of extended workdays on fatigue,

health,performance and satisfaction in nursing.J Adv Nurs.2003;44(6):643–52.

13. Geiger-Brown J,Trinkoff AM.Is it time to pullthe plug on 12-hour shifts?:

Part 1.The evidence.J Nurs Adm.2010;40(3):100–2.

14. O’Connor T.Director or Nursing at ADHB wants end to 12-hour shifts.Kai

TiakiNursing New Zealand.2011;17(9):37.

15. Sprinks J.Trust says shorter shifts willgive nurses more time at the bedside.

Nurs Stand.2012;27(7):8.

16. Maben J.Long days come with a high price for staff and patients.Nurs

Times.2010;106(2):25.

17. StimpfelAW,Aiken LH.Hospitalstaff nurses’shift length associated with

safety and quality of care.J Nurs Care Qual.2013;28(2):122–9.

18. StimpfelAW,Sloane DM,Aiken LH.The longer the shifts for hospitalnurses,

the higher the levels of burnout and patient dissatisfaction.Health Aff

(Millwood).2012;31(11):2501–9.

19. Clendon J,Gibbons V.12 h shifts and rates of error among nurses:a

systematic review.Int J Nurs Stud.2015;52(7):1231–42.

20. Burgess PA.Optimalshift duration and sequence:recommended approach

for short-term emergency response activations for public health and

emergency management.Am J Public Health.2007;97 Suppl1:S88–92.

21. Smith L,Folkard S,Tucker P,Macdonald I.Work shift duration:a review

comparing eight hour and 12 hour shift systems.Occup Environ Med.

1998;55(4):217–29.

22. Williamson AM,Gower CG,Clarke BC.Changing the hours of shiftwork:a

comparison of 8- and 12-hour shift rosters in a group of computer

operators.Ergonomics.1994;37(2):287–98.

23. Duchon JC,Keran CM,Smith TJ.Extended workdays in an underground

mine:a work performance analysis.Hum Factors.1994;36(2):258–68.

24. Griffiths P,Dall’Ora C,Simon M,BallJ, Lindqvist R,Rafferty AM,

SchoonhovenL,Tishelman C,Aiken LH.Nurses’shift length and overtime

working in 12 European countries:the association with perceived quality of

care and patient safety.Med Care.2014;52(11):975–81.

25. Dall’Ora C,Griffiths P,BallJ, Simon M,Aiken LH.Association of 12 h

shifts and nurses’job satisfaction,burnout and intention to leave:

findings from a cross-sectionalstudy of 12 European countries.BMJ

Open.2015;5(9):e008331.

26. Harris R,Sims S,Parr J,Davies N.Impact of 12 h shift patterns in nursing:a

scoping review.Int J Nurs Stud.2015;52(2):605–34.

27. Dall’Ora C,BallJ, Recio-Saucedo A,Griffiths P.Characteristics of shift work

and their impact on employee performance and wellbeing:a literature

review.Int J Nurs Stud.2016;57:12–27.

28. StimpfelAW,Lake ET,Barton S,Gorman KC,Aiken LH.How differing

shift lengths relate to quality outcomes in pediatrics.J Nurs Adm.2013;

43(2):95–100.

29. Stone PW,Du Y,CowellR,Amsterdam N,Helfrich TA,Linn RW,Gladstein A,

Walsh M,Mojica LA.Comparison of nurse,system and quality patient care

outcomes in 8-hour and 12-hour shifts.Med Care.2006;44(12):1099–106.

30. Trinkoff AM,Johantgen M,Storr CL,Gurses AP,Liang Y,Han K.Nurses’

work schedule characteristics,nurse staffing and patient mortality.Nurs

Res.2011;60(1):1–8.

31. Calkin S.Shift patterns divide nursing.Nurs Times.2012;108(29):2–3.

32. Maben J.What struck me was the powerlessness many nurses felt.In:

Nursing times.2010.http://www.nursingtimes.net/what-struck-me-was-the-

powerlessness-many-nurses-felt/5014247.article.

• We accept pre-submission inquiries

• Our selector tool helps you to find the most relevant journal

• We provide round the clock customer support

• Convenient online submission

• Thorough peer review

• Inclusion in PubMed and all major indexing services

• Maximum visibility for your research

Submit your manuscript at

www.biomedcentral.com/submit

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central

and we will help you at every step:

Ball et al.BMC Nursing (2017) 16:26 Page 7 of 7

relationship of work hours,mandatory overtime,and on-callto

musculoskeletalproblems in nurses.Am J Ind Med.2006;49(11):964–71.

4. Estabrooks CA,Cummings GG,Olivo SA,Squires JE,Giblin C,Simpson N.

Effects of shift length on quality of patient care and health provider

outcomes:systematic review.QualSaf Health Care.2009;18(3):181–8.

5. Ferguson SA,Dawson D.12-h or 8-h shifts? It depends.Sleep Med Rev.

2012;16(6):519–28.

6. McGettrick KS,O’NeillMA.Criticalcare nurses–perceptions of 12-h shifts.

Nurs Crit Care.2006;11(4):188–97.

7. Todd C,Reid N,Robinson G.The quality of nursing care on wards working

eight and twelve hour shifts:a repeated measures study using the

MONITOR index of quality of care.Int J Nurs Stud.1989;26(4):359–68.

8. NHS Evidence.Moving to 12-hour shift patterns:to increase continuity and

reduce costs.London:QIPP,Basingstoke and North Hampshire NHS

Foundation Trust;2010.

9. BallJ, Dall’Ora C,Griffiths P.The 12-hour shift:friend or foe? Nurs Times.

2015;111(6):12–4.

10. Bambra C,Whitehead M,Sowden A,Akers J,Petticrew M.“A hard day’s

night?” The effects of Compressed Working Week interventions on the

health and work-life balance of shift workers:a systematic review.J

EpidemiolCommunity Health.2008;62(9):764–77.

11. Estryn-Behar M,Van der Heijden BI,Group NS.Effects of extended work

shifts on employee fatigue,health,satisfaction,work/family balance,and

patient safety.Work.2012;41 Suppl1:4283–90.

12. Josten EJ,Ng ATJE,Thierry H.The effects of extended workdays on fatigue,

health,performance and satisfaction in nursing.J Adv Nurs.2003;44(6):643–52.

13. Geiger-Brown J,Trinkoff AM.Is it time to pullthe plug on 12-hour shifts?:

Part 1.The evidence.J Nurs Adm.2010;40(3):100–2.

14. O’Connor T.Director or Nursing at ADHB wants end to 12-hour shifts.Kai

TiakiNursing New Zealand.2011;17(9):37.

15. Sprinks J.Trust says shorter shifts willgive nurses more time at the bedside.

Nurs Stand.2012;27(7):8.

16. Maben J.Long days come with a high price for staff and patients.Nurs

Times.2010;106(2):25.

17. StimpfelAW,Aiken LH.Hospitalstaff nurses’shift length associated with

safety and quality of care.J Nurs Care Qual.2013;28(2):122–9.

18. StimpfelAW,Sloane DM,Aiken LH.The longer the shifts for hospitalnurses,

the higher the levels of burnout and patient dissatisfaction.Health Aff

(Millwood).2012;31(11):2501–9.

19. Clendon J,Gibbons V.12 h shifts and rates of error among nurses:a

systematic review.Int J Nurs Stud.2015;52(7):1231–42.

20. Burgess PA.Optimalshift duration and sequence:recommended approach

for short-term emergency response activations for public health and

emergency management.Am J Public Health.2007;97 Suppl1:S88–92.

21. Smith L,Folkard S,Tucker P,Macdonald I.Work shift duration:a review

comparing eight hour and 12 hour shift systems.Occup Environ Med.

1998;55(4):217–29.

22. Williamson AM,Gower CG,Clarke BC.Changing the hours of shiftwork:a

comparison of 8- and 12-hour shift rosters in a group of computer

operators.Ergonomics.1994;37(2):287–98.

23. Duchon JC,Keran CM,Smith TJ.Extended workdays in an underground

mine:a work performance analysis.Hum Factors.1994;36(2):258–68.

24. Griffiths P,Dall’Ora C,Simon M,BallJ, Lindqvist R,Rafferty AM,

SchoonhovenL,Tishelman C,Aiken LH.Nurses’shift length and overtime

working in 12 European countries:the association with perceived quality of

care and patient safety.Med Care.2014;52(11):975–81.

25. Dall’Ora C,Griffiths P,BallJ, Simon M,Aiken LH.Association of 12 h

shifts and nurses’job satisfaction,burnout and intention to leave:

findings from a cross-sectionalstudy of 12 European countries.BMJ

Open.2015;5(9):e008331.

26. Harris R,Sims S,Parr J,Davies N.Impact of 12 h shift patterns in nursing:a

scoping review.Int J Nurs Stud.2015;52(2):605–34.

27. Dall’Ora C,BallJ, Recio-Saucedo A,Griffiths P.Characteristics of shift work

and their impact on employee performance and wellbeing:a literature

review.Int J Nurs Stud.2016;57:12–27.

28. StimpfelAW,Lake ET,Barton S,Gorman KC,Aiken LH.How differing

shift lengths relate to quality outcomes in pediatrics.J Nurs Adm.2013;

43(2):95–100.

29. Stone PW,Du Y,CowellR,Amsterdam N,Helfrich TA,Linn RW,Gladstein A,

Walsh M,Mojica LA.Comparison of nurse,system and quality patient care

outcomes in 8-hour and 12-hour shifts.Med Care.2006;44(12):1099–106.

30. Trinkoff AM,Johantgen M,Storr CL,Gurses AP,Liang Y,Han K.Nurses’

work schedule characteristics,nurse staffing and patient mortality.Nurs

Res.2011;60(1):1–8.

31. Calkin S.Shift patterns divide nursing.Nurs Times.2012;108(29):2–3.

32. Maben J.What struck me was the powerlessness many nurses felt.In:

Nursing times.2010.http://www.nursingtimes.net/what-struck-me-was-the-

powerlessness-many-nurses-felt/5014247.article.

• We accept pre-submission inquiries

• Our selector tool helps you to find the most relevant journal

• We provide round the clock customer support

• Convenient online submission

• Thorough peer review

• Inclusion in PubMed and all major indexing services

• Maximum visibility for your research

Submit your manuscript at

www.biomedcentral.com/submit

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central

and we will help you at every step:

Ball et al.BMC Nursing (2017) 16:26 Page 7 of 7

1 out of 7

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.