Short Selling's Impact on Earnings Management: An Experiment

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/18

|44

|25617

|76

Report

AI Summary

The provided document is a research paper titled "Short Selling and Earnings Management: A Controlled Experiment" published in the Journal of Finance. The study, conducted during the SEC's pilot program (2005-2007) where some stocks were exempt from short-sale price tests, investigates the impact of short selling on corporate financial reporting. The research reveals that pilot firms exhibited decreased discretionary accruals and a lower likelihood of marginally beating earnings targets. Moreover, these firms were more likely to be caught for pre-existing fraud and showed improved stock price efficiency in incorporating earnings information. The findings suggest that short selling, or the prospect of it, acts as a constraint on earnings management, aids in fraud detection, and enhances price efficiency. The paper contributes to the literature by demonstrating the influence of short selling on financial reporting, identifying it as a determinant of earnings management, highlighting its role in improving price efficiency, and adding to the policy debate surrounding the benefits and costs of short selling.

THE JOURNAL OF FINANCE • VOL. LXXI, NO. 3 • JUNE 2016

Short Selling and Earnings Management:

A Controlled Experiment

VIVIAN W. FANG, ALLEN H. HUANG, and JONATHAN M. KARPOFF ∗

ABSTRACT

During 2005 to 2007,the SEC ordered a pilot program in which one-third of the

Russell 3000 index were arbitrarily chosen as pilot stocks and exempted from short-

sale price tests. Pilot firms’ discretionary accruals and likelihood of marginally beating

earnings targets decrease during this period, and revert to pre-experiment levels when

the program ends. After the program starts, pilot firms are more likely to be caught

for fraud initiated before the program,and their stock returns better incorporate

earnings information. These results indicate that short selling, or its prospect, curbs

earnings management, helps detect fraud, and improves price efficiency.

PREVIOUS RESEARCH SHOWS that short sellers can identify earnings manipulation

and fraud before they are publicly revealed.1 But this is for earnings manip-

ulation that has already taken place. Might short selling also constrain firms’

incentives to manipulate or misrepresent earnings in the first place? That is,

does the prospect of short selling help improve the quality of firms’financial

reporting?

In this paper we exploit a randomized experiment that allows us to address

this question.In July 2004, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

adopted a new regulation governing short-selling activities in the U.S. equity

markets–Regulation SHO.Regulation SHO contained a Rule 202T pilot pro-

gram in which stocks in the Russell 3000 index were ranked by trading volume

∗Fang is with the University of Minnesota.Huang is with the Hong Kong University of Sci-

ence and Technology.Karpoff is with the University of Washington.We are grateful for helpful

comments from two anonymous referees, an anonymous Associate Editor, Kenneth Singleton (the

Editor), Vikas Agarwal, Mark Chen, John Core, Hemang Desai, Jarrad Harford, Adam Kolasin-

ski, Craig Lewis, Paul Ma, Scott Richardson,Ed Swanson, Jake Thornock, Wendy Wilson,and

seminar participants at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business,Peking University, the

SEC/Maryland Conference on the Regulation of Financial Markets, the CEAR/GSU Finance Sym-

posium on Corporate ControlMechanisms and Risk, the FARS Midyear Meeting, the HKUST

Accounting Symposium,the CFEA Conference,and the UC Berkeley Multi-disciplinary Confer-

ence on Fraud and Misconduct.We are grateful to Russell Investments for providing the list of

2004 Russell 3000 index firms, and to Jerry Martin for providing the KKLM data on financial mis-

representation. Huang gratefully acknowledges financial support from a grant from the Research

Grants Council of the HKSAR, China (Project No. HKUST691213).

1 See Dechow, Sloan, and Sweeney (1996), Christophe, Ferri, and Angel (2004), Efendi, Kinney,

and Swanson (2005),Desai, Krishnamurthy, and Venkataraman (2006),and Karpoff and Lou

(2010).

DOI: 10.1111/jofi.12369

1251

Short Selling and Earnings Management:

A Controlled Experiment

VIVIAN W. FANG, ALLEN H. HUANG, and JONATHAN M. KARPOFF ∗

ABSTRACT

During 2005 to 2007,the SEC ordered a pilot program in which one-third of the

Russell 3000 index were arbitrarily chosen as pilot stocks and exempted from short-

sale price tests. Pilot firms’ discretionary accruals and likelihood of marginally beating

earnings targets decrease during this period, and revert to pre-experiment levels when

the program ends. After the program starts, pilot firms are more likely to be caught

for fraud initiated before the program,and their stock returns better incorporate

earnings information. These results indicate that short selling, or its prospect, curbs

earnings management, helps detect fraud, and improves price efficiency.

PREVIOUS RESEARCH SHOWS that short sellers can identify earnings manipulation

and fraud before they are publicly revealed.1 But this is for earnings manip-

ulation that has already taken place. Might short selling also constrain firms’

incentives to manipulate or misrepresent earnings in the first place? That is,

does the prospect of short selling help improve the quality of firms’financial

reporting?

In this paper we exploit a randomized experiment that allows us to address

this question.In July 2004, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

adopted a new regulation governing short-selling activities in the U.S. equity

markets–Regulation SHO.Regulation SHO contained a Rule 202T pilot pro-

gram in which stocks in the Russell 3000 index were ranked by trading volume

∗Fang is with the University of Minnesota.Huang is with the Hong Kong University of Sci-

ence and Technology.Karpoff is with the University of Washington.We are grateful for helpful

comments from two anonymous referees, an anonymous Associate Editor, Kenneth Singleton (the

Editor), Vikas Agarwal, Mark Chen, John Core, Hemang Desai, Jarrad Harford, Adam Kolasin-

ski, Craig Lewis, Paul Ma, Scott Richardson,Ed Swanson, Jake Thornock, Wendy Wilson,and

seminar participants at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business,Peking University, the

SEC/Maryland Conference on the Regulation of Financial Markets, the CEAR/GSU Finance Sym-

posium on Corporate ControlMechanisms and Risk, the FARS Midyear Meeting, the HKUST

Accounting Symposium,the CFEA Conference,and the UC Berkeley Multi-disciplinary Confer-

ence on Fraud and Misconduct.We are grateful to Russell Investments for providing the list of

2004 Russell 3000 index firms, and to Jerry Martin for providing the KKLM data on financial mis-

representation. Huang gratefully acknowledges financial support from a grant from the Research

Grants Council of the HKSAR, China (Project No. HKUST691213).

1 See Dechow, Sloan, and Sweeney (1996), Christophe, Ferri, and Angel (2004), Efendi, Kinney,

and Swanson (2005),Desai, Krishnamurthy, and Venkataraman (2006),and Karpoff and Lou

(2010).

DOI: 10.1111/jofi.12369

1251

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1252 The Journal of FinanceR

within each exchange and every third one was designated as a pilot stock.

From May 2, 2005 to August 6, 2007, pilot stocks were exempted from short-

sale price tests, including the tick test for exchange-listed stocks and the bid

test for NASDAQ National Market (NASDAQ-NM) stocks.2

The pilot program creates an idealsetting to examine the effect ofshort

selling on corporate financial reporting decisions, for three reasons. First, the

exemption from short-sale price tests decreased the cost ofshort selling in

the pilot stocks relative to the nonpilot stocks (SEC (2007), Diether, Lee, and

Werner (2009)). The pilot program thus eliminates the need to directly estimate

short-selling costs, a notoriously difficult task (Lamont (2012)). Rather, we use

the fact that the prospect of short selling increased for pilot firms relative to

nonpilot firms during the program. Second, the pilot program represents a truly

exogenous shock to the cost of selling short in the affected firms. We identify no

evidence that the firms themselves lobbied for the pilot program, or that any

individual firm could know it would be in the pilot group until the program was

announced. Third, the pilot program had specific beginning and ending dates,

facilitating difference-in-differences (hereafter, DiD) analysis of the impact of

short-selling costs on firms’financial reporting. In particular, the anticipated

ending date allows us to investigate whether the effects of the pilot program

reversed when it ended – an important check on the internal validity of the

DiD tests (e.g., Roberts and Whited (2013)).

We begin by verifying that pilot firms represent a random draw from the Rus-

sell 3000 population. In the fiscal year before the pilot program, pilot and non-

pilot firms are similar in size, growth, investment, profitability, leverage, and

dividend payout. Although the two groups of firms also exhibit similar levels of

discretionary accruals before the program, pilot firms significantly reduce their

signed discretionary accruals once the program starts.3 After the program ends,

pilot firms’discretionary accruals revert to pre-program levels.The nonpilot

firms, meanwhile, show no significant change in discretionary accruals around

the pilot program. Our point estimates indicate that performance-matched dis-

cretionary accruals, as a percentage of assets, are one percentage point lower

for pilot firms than for nonpilot firms during the pilot program compared to

the pre-pilot period.This corresponds to 7.4% ofthe standard deviation of

discretionary accruals in our sample.

We also examine the pilot program’s effect on two alternative measures of

earnings management. First, we find that the likelihood of beating the analyst

2 The pilot program was originally scheduled to commence on January 3,2005,and end on

December 31,2005 (Securities Exchange Act Release No.50104,July 28, 2004).However,the

SEC postponed the commencement date to May 2, 2005 (Securities and Exchange Act Release No.

50747, November 29, 2004) and extended the end date to August 6, 2007 (Securities and Exchange

Act Release No. 53684, April 20, 2006). Before the pilot program ran its entire course, the SEC

eliminated short-sale price tests for all exchange-listed stocks on July 6, 2007 (Securities Exchange

Act of 1934 Release No. 34-55970, July 3, 2007).

3 Following the literature (e.g., Kothari, Leone, and Wasley (2005)), we measure discretionary ac-

cruals as the difference between actual accruals and a benchmark estimated within each industry-

year. Details are provided in Section II.C.

within each exchange and every third one was designated as a pilot stock.

From May 2, 2005 to August 6, 2007, pilot stocks were exempted from short-

sale price tests, including the tick test for exchange-listed stocks and the bid

test for NASDAQ National Market (NASDAQ-NM) stocks.2

The pilot program creates an idealsetting to examine the effect ofshort

selling on corporate financial reporting decisions, for three reasons. First, the

exemption from short-sale price tests decreased the cost ofshort selling in

the pilot stocks relative to the nonpilot stocks (SEC (2007), Diether, Lee, and

Werner (2009)). The pilot program thus eliminates the need to directly estimate

short-selling costs, a notoriously difficult task (Lamont (2012)). Rather, we use

the fact that the prospect of short selling increased for pilot firms relative to

nonpilot firms during the program. Second, the pilot program represents a truly

exogenous shock to the cost of selling short in the affected firms. We identify no

evidence that the firms themselves lobbied for the pilot program, or that any

individual firm could know it would be in the pilot group until the program was

announced. Third, the pilot program had specific beginning and ending dates,

facilitating difference-in-differences (hereafter, DiD) analysis of the impact of

short-selling costs on firms’financial reporting. In particular, the anticipated

ending date allows us to investigate whether the effects of the pilot program

reversed when it ended – an important check on the internal validity of the

DiD tests (e.g., Roberts and Whited (2013)).

We begin by verifying that pilot firms represent a random draw from the Rus-

sell 3000 population. In the fiscal year before the pilot program, pilot and non-

pilot firms are similar in size, growth, investment, profitability, leverage, and

dividend payout. Although the two groups of firms also exhibit similar levels of

discretionary accruals before the program, pilot firms significantly reduce their

signed discretionary accruals once the program starts.3 After the program ends,

pilot firms’discretionary accruals revert to pre-program levels.The nonpilot

firms, meanwhile, show no significant change in discretionary accruals around

the pilot program. Our point estimates indicate that performance-matched dis-

cretionary accruals, as a percentage of assets, are one percentage point lower

for pilot firms than for nonpilot firms during the pilot program compared to

the pre-pilot period.This corresponds to 7.4% ofthe standard deviation of

discretionary accruals in our sample.

We also examine the pilot program’s effect on two alternative measures of

earnings management. First, we find that the likelihood of beating the analyst

2 The pilot program was originally scheduled to commence on January 3,2005,and end on

December 31,2005 (Securities Exchange Act Release No.50104,July 28, 2004).However,the

SEC postponed the commencement date to May 2, 2005 (Securities and Exchange Act Release No.

50747, November 29, 2004) and extended the end date to August 6, 2007 (Securities and Exchange

Act Release No. 53684, April 20, 2006). Before the pilot program ran its entire course, the SEC

eliminated short-sale price tests for all exchange-listed stocks on July 6, 2007 (Securities Exchange

Act of 1934 Release No. 34-55970, July 3, 2007).

3 Following the literature (e.g., Kothari, Leone, and Wasley (2005)), we measure discretionary ac-

cruals as the difference between actual accruals and a benchmark estimated within each industry-

year. Details are provided in Section II.C.

Short Selling and Earnings Management 1253

consensus forecast by up to one cent is 1.8 percentage points lower for the pilot

firms than for the nonpilot firms during the pilot program compared to the pre-

pilot period. This represents 11.1% of the unconditional likelihood of meeting

or just beating the analyst consensus forecast in our sample.Similarly, the

likelihood of meeting or just beating the firm’s quarterly earnings per share

(EPS) in the same quarter of the prior year is 0.8 percentage points lower

for the pilot firms during the pilot program compared to the pre-pilot period,

representing 14.2% of the unconditional likelihood.Second,we find that the

likelihood of being classified as a misstating firm,based on the F-score of

Dechow et al. (2011), is significantly lower for the pilot firms during the pilot

period compared to the pre-pilot period. Combined with our results regarding

discretionary accruals, these results indicate that pilot firms decrease earnings

management during the pilot program.

We consider several alternative interpretations for the patterns we observe

in discretionary accruals. One possibility is that pilot firms’ discretionary accru-

als reflect changes in their growth, investment, or equity issuance, as Grullon,

Michenaud, and Weston (2015) document a significant reduction in financially

constrained pilot firms’investment and equity issuance during the pilot pro-

gram. We consider several ways to control for firm growth and investment, both

in the construction of our discretionary accruals measures and in the multivari-

ate tests. None of these controls have a material effect on our main findings.

We also find that the pilot firms’ investment levels do not follow a pattern that

would explain the changes in their discretionary accruals during and after the

pilot program. Regarding the possible impact of equity issuance, we find that

pilot firms’discretionary accruals pattern is similar between firms that do not

seek to issue equity and the overall sample.These results indicate that the

effect of the pilot program on discretionary accruals is unlikely to be explained

by changes in pilot firms’growth, investment, or equity issuance around the

program.

Another possible explanation is that managers of the pilot firms decreased

earnings management because of a general increase in the attention investors

paid to these firms.Using three measures of market attention,however,we

do not find that pilot firms were subject to greater attention during the pilot

program.In multivariate DiD tests, the market attention measures are not

significantly related to discretionary accruals,nor do they affect our main

findings regarding discretionary accruals.

The most plausible interpretation of our results is that the pilot program

reduced the cost of short selling sufficiently among the pilot firms to increase

potential short sellers’ monitoring activities, and that the increased monitoring

induced a decrease in these firms’earnings management.4 We conduct three

additional tests to further probe this interpretation. First, we find that, among

the pilot firms during the pilot program, short selling is positively related to

signed discretionary accruals. Second, we find that short interest increases in

4 Throughout this paper, we use “potentialshort sellers” or “short sellers” to refer to both

investors who may take new short positions and investors with existing short positions.

consensus forecast by up to one cent is 1.8 percentage points lower for the pilot

firms than for the nonpilot firms during the pilot program compared to the pre-

pilot period. This represents 11.1% of the unconditional likelihood of meeting

or just beating the analyst consensus forecast in our sample.Similarly, the

likelihood of meeting or just beating the firm’s quarterly earnings per share

(EPS) in the same quarter of the prior year is 0.8 percentage points lower

for the pilot firms during the pilot program compared to the pre-pilot period,

representing 14.2% of the unconditional likelihood.Second,we find that the

likelihood of being classified as a misstating firm,based on the F-score of

Dechow et al. (2011), is significantly lower for the pilot firms during the pilot

period compared to the pre-pilot period. Combined with our results regarding

discretionary accruals, these results indicate that pilot firms decrease earnings

management during the pilot program.

We consider several alternative interpretations for the patterns we observe

in discretionary accruals. One possibility is that pilot firms’ discretionary accru-

als reflect changes in their growth, investment, or equity issuance, as Grullon,

Michenaud, and Weston (2015) document a significant reduction in financially

constrained pilot firms’investment and equity issuance during the pilot pro-

gram. We consider several ways to control for firm growth and investment, both

in the construction of our discretionary accruals measures and in the multivari-

ate tests. None of these controls have a material effect on our main findings.

We also find that the pilot firms’ investment levels do not follow a pattern that

would explain the changes in their discretionary accruals during and after the

pilot program. Regarding the possible impact of equity issuance, we find that

pilot firms’discretionary accruals pattern is similar between firms that do not

seek to issue equity and the overall sample.These results indicate that the

effect of the pilot program on discretionary accruals is unlikely to be explained

by changes in pilot firms’growth, investment, or equity issuance around the

program.

Another possible explanation is that managers of the pilot firms decreased

earnings management because of a general increase in the attention investors

paid to these firms.Using three measures of market attention,however,we

do not find that pilot firms were subject to greater attention during the pilot

program.In multivariate DiD tests, the market attention measures are not

significantly related to discretionary accruals,nor do they affect our main

findings regarding discretionary accruals.

The most plausible interpretation of our results is that the pilot program

reduced the cost of short selling sufficiently among the pilot firms to increase

potential short sellers’ monitoring activities, and that the increased monitoring

induced a decrease in these firms’earnings management.4 We conduct three

additional tests to further probe this interpretation. First, we find that, among

the pilot firms during the pilot program, short selling is positively related to

signed discretionary accruals. Second, we find that short interest increases in

4 Throughout this paper, we use “potentialshort sellers” or “short sellers” to refer to both

investors who may take new short positions and investors with existing short positions.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1254 The Journal of FinanceR

months in which firms are later revealed to have engaged in financial misrepre-

sentation during our sample period. And third, we find that, among firms that

previously initiated financial fraud,pilot firms are more likely to get caught

than control firms after the pilot period started.We also find that the un-

conditional likelihood of pilot firms being caught for financial fraud converges

monotonically toward that of nonpilot firms as we sequentially include cases of

fraud initiated after the pilot program begins. This result is consistent with the

argument that pilot firms’conditional likelihood of being caught for any fraud

they commit is higher during the program, and with our main finding that pilot

firms endogenously adjust by decreasing earnings manipulation after the pilot

program begins.

Finally, we examine the implications of the pilot program for price efficiency

through its effect on firms’ reporting practices. We show that the coefficients of

pilot firms’ current returns on future earnings increase during the pilot period.

Among firms announcing particularly negative earnings surprises,the well-

documented post-earnings announcement drift (PEAD)disappears for pilot

firms during the period, while it remains significant for nonpilot firms. These

results indicate that the reduction in pilot firms’ earnings management during

the pilot program corresponds to an increase in the efficiency of their stock

prices as their stock returns better incorporate earnings information.

The above findings make four contributions to the literature. First, they show

that an increase in the prospect of short selling has a significant effect on firms’

financial reporting. This result demonstrates one avenue through which trad-

ing in secondary financial markets affects firms’decisions.5 Second, our find-

ings identify a new determinant of earnings management, namely, short-sale

constraints, adding to the factors identified in prior research (for a review, see

Dechow, Ge, and Schrand (2010)). Third, our results indicate that the prospect

of short selling improves price efficiency not only by facilitating the flow of

private information into prices (e.g., Miller (1977), Harrison and Kreps (1978),

Chang, Cheng, and Yu (2007), Boehmer and Wu (2013)), but also by decreasing

managers’tendency to manage earnings. And fourth, our findings contribute

to the policy debate on the benefits and costs of short selling. Previous research

demonstrates that short sellers are good at identifying the overpriced shares

of firms that have manipulated earnings, and short sellers’ trading accelerates

the discovery of financial misconduct.6 Our results indicate that the prospect

of short selling conveys additional external benefits to investors by improving

financial reporting quality and stock price efficiency in general,even among

firms not charged with financial reporting violations.

5 See Bond, Edmans, and Goldstein (2012) for a survey of research on the real effects of financial

markets. For example, Karpoff and Rice (1989) and Fang, Noe, and Tice (2009) examine the effect

of stock liquidity on firm performance, Fang, Tian, and Tice (2014) examine the effect of liquidity

on innovation,and Grullon, Michenaud, and Weston (2015) examine the effect of short-selling

constraints on investment and equity issuance.

6 See the references in footnote 1. To be sure, other studies have noted the potential dark side of

short selling, as manipulative short selling could reduce price efficiency (e.g., Gerard and Nanda

(1993), Henry and Koski (2010)).

months in which firms are later revealed to have engaged in financial misrepre-

sentation during our sample period. And third, we find that, among firms that

previously initiated financial fraud,pilot firms are more likely to get caught

than control firms after the pilot period started.We also find that the un-

conditional likelihood of pilot firms being caught for financial fraud converges

monotonically toward that of nonpilot firms as we sequentially include cases of

fraud initiated after the pilot program begins. This result is consistent with the

argument that pilot firms’conditional likelihood of being caught for any fraud

they commit is higher during the program, and with our main finding that pilot

firms endogenously adjust by decreasing earnings manipulation after the pilot

program begins.

Finally, we examine the implications of the pilot program for price efficiency

through its effect on firms’ reporting practices. We show that the coefficients of

pilot firms’ current returns on future earnings increase during the pilot period.

Among firms announcing particularly negative earnings surprises,the well-

documented post-earnings announcement drift (PEAD)disappears for pilot

firms during the period, while it remains significant for nonpilot firms. These

results indicate that the reduction in pilot firms’ earnings management during

the pilot program corresponds to an increase in the efficiency of their stock

prices as their stock returns better incorporate earnings information.

The above findings make four contributions to the literature. First, they show

that an increase in the prospect of short selling has a significant effect on firms’

financial reporting. This result demonstrates one avenue through which trad-

ing in secondary financial markets affects firms’decisions.5 Second, our find-

ings identify a new determinant of earnings management, namely, short-sale

constraints, adding to the factors identified in prior research (for a review, see

Dechow, Ge, and Schrand (2010)). Third, our results indicate that the prospect

of short selling improves price efficiency not only by facilitating the flow of

private information into prices (e.g., Miller (1977), Harrison and Kreps (1978),

Chang, Cheng, and Yu (2007), Boehmer and Wu (2013)), but also by decreasing

managers’tendency to manage earnings. And fourth, our findings contribute

to the policy debate on the benefits and costs of short selling. Previous research

demonstrates that short sellers are good at identifying the overpriced shares

of firms that have manipulated earnings, and short sellers’ trading accelerates

the discovery of financial misconduct.6 Our results indicate that the prospect

of short selling conveys additional external benefits to investors by improving

financial reporting quality and stock price efficiency in general,even among

firms not charged with financial reporting violations.

5 See Bond, Edmans, and Goldstein (2012) for a survey of research on the real effects of financial

markets. For example, Karpoff and Rice (1989) and Fang, Noe, and Tice (2009) examine the effect

of stock liquidity on firm performance, Fang, Tian, and Tice (2014) examine the effect of liquidity

on innovation,and Grullon, Michenaud, and Weston (2015) examine the effect of short-selling

constraints on investment and equity issuance.

6 See the references in footnote 1. To be sure, other studies have noted the potential dark side of

short selling, as manipulative short selling could reduce price efficiency (e.g., Gerard and Nanda

(1993), Henry and Koski (2010)).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Short Selling and Earnings Management 1255

This paper is organized as follows. Section I describes short-sale price tests in

the U.S. equity markets, how they can affect firms’tendency to manage earn-

ings, and related research.Section II describes the data.Section III reports

tests of the effect of Regulation SHO’s pilot program on firms’earnings man-

agement. Section IV examines whether short sellers actually increased their

scrutiny of the pilot stocks during the pilot program by comparing the prob-

ability of fraud detection between pilot and nonpilot firms. Section V reports

on tests that examine whether the pilot program coincided with an increase

in the efficiency of pilot firms’stock prices with respect to earnings.Finally,

Section VI concludes.

I. Short-Sale Price Tests, Their Effect on Earnings Management, and

Related Research

A. Short-Sale Price Tests in U.S. Equity Markets

Short-sale price tests were initially introduced in the U.S. equity markets in

the 1930s, ostensibly to avoid bear raids by short sellers in declining markets.

The NYSE adopted an uptick rule in 1935,which was replaced in 1938 by a

stricter SEC rule, Rule 10a-1,also known as the “tick test.” The latter rule

mandates that a short sale can only occur at a price above the most recently

traded price (plus tick) or at the most recently traded price if that price exceeds

the last different price (zero-plus tick).7 In 1994, the National Association of

Securities Dealers (NASD) adopted its own price test (the “bid test”) under Rule

3350. Rule 3350 requires that a short sale occur at a price one penny above the

bid price if the bid is a downtick from the previous bid.8

To facilitate research on the effects ofshort-sale price tests on financial

markets, the SEC initiated a pilot program under Rule 202T of Regulation

SHO in July 2004. Under the pilot program, every third stock in the Russell

3000 index ranked by trading volume within each exchange was selected as a

pilot stock. From May 2, 2005, to August 6, 2007, pilot stocks were exempted

from short-sale price tests. The program effectively ended one month early on

July 6, 2007, when the SEC eliminated short-sale price tests for all exchange-

listed stocks including the nonpilot stocks.

The decision to eliminate all short-sale price tests prompted a huge back-

lash from managers and politicians.In 2008, NYSE Euronext commissioned

Opinion Research Corporation (2008)to conduct a study to seek corporate

7 Narrow exceptions apply, as specified in SEC’s Rule 10a-1, section (e).

8 Rule 3350 applies to NASDAQ National Market (NASDAQ-NM or NNM) securities. Securities

traded in the OTC markets, including NASDAQ Small Cap, OTCBB, and OTC Pink Sheets, are

exempted. When NASDAQ became a national listed exchange in August 2006, NASD Rule 3350

was replaced by NASDAQ Rule 3350 for NASDAQ Global Market securities (formerly NASDAQ-

NM securities) traded on NASDAQ, and NASD Rule 5100 for NASDAQ-NM securities traded over

the counter. The NASDAQ switched from fractional pricing to decimal pricing over the March 12,

2001 to April 9, 2001 period. Prior to decimalization, Rule 3350 required a short sale to occur at a

price 1/8th of a dollar (if before June 2, 1997) or 1/16th of a dollar (if after June 2, 1997) above the

bid.

This paper is organized as follows. Section I describes short-sale price tests in

the U.S. equity markets, how they can affect firms’tendency to manage earn-

ings, and related research.Section II describes the data.Section III reports

tests of the effect of Regulation SHO’s pilot program on firms’earnings man-

agement. Section IV examines whether short sellers actually increased their

scrutiny of the pilot stocks during the pilot program by comparing the prob-

ability of fraud detection between pilot and nonpilot firms. Section V reports

on tests that examine whether the pilot program coincided with an increase

in the efficiency of pilot firms’stock prices with respect to earnings.Finally,

Section VI concludes.

I. Short-Sale Price Tests, Their Effect on Earnings Management, and

Related Research

A. Short-Sale Price Tests in U.S. Equity Markets

Short-sale price tests were initially introduced in the U.S. equity markets in

the 1930s, ostensibly to avoid bear raids by short sellers in declining markets.

The NYSE adopted an uptick rule in 1935,which was replaced in 1938 by a

stricter SEC rule, Rule 10a-1,also known as the “tick test.” The latter rule

mandates that a short sale can only occur at a price above the most recently

traded price (plus tick) or at the most recently traded price if that price exceeds

the last different price (zero-plus tick).7 In 1994, the National Association of

Securities Dealers (NASD) adopted its own price test (the “bid test”) under Rule

3350. Rule 3350 requires that a short sale occur at a price one penny above the

bid price if the bid is a downtick from the previous bid.8

To facilitate research on the effects ofshort-sale price tests on financial

markets, the SEC initiated a pilot program under Rule 202T of Regulation

SHO in July 2004. Under the pilot program, every third stock in the Russell

3000 index ranked by trading volume within each exchange was selected as a

pilot stock. From May 2, 2005, to August 6, 2007, pilot stocks were exempted

from short-sale price tests. The program effectively ended one month early on

July 6, 2007, when the SEC eliminated short-sale price tests for all exchange-

listed stocks including the nonpilot stocks.

The decision to eliminate all short-sale price tests prompted a huge back-

lash from managers and politicians.In 2008, NYSE Euronext commissioned

Opinion Research Corporation (2008)to conduct a study to seek corporate

7 Narrow exceptions apply, as specified in SEC’s Rule 10a-1, section (e).

8 Rule 3350 applies to NASDAQ National Market (NASDAQ-NM or NNM) securities. Securities

traded in the OTC markets, including NASDAQ Small Cap, OTCBB, and OTC Pink Sheets, are

exempted. When NASDAQ became a national listed exchange in August 2006, NASD Rule 3350

was replaced by NASDAQ Rule 3350 for NASDAQ Global Market securities (formerly NASDAQ-

NM securities) traded on NASDAQ, and NASD Rule 5100 for NASDAQ-NM securities traded over

the counter. The NASDAQ switched from fractional pricing to decimal pricing over the March 12,

2001 to April 9, 2001 period. Prior to decimalization, Rule 3350 required a short sale to occur at a

price 1/8th of a dollar (if before June 2, 1997) or 1/16th of a dollar (if after June 2, 1997) above the

bid.

1256 The Journal of FinanceR

issuers’views on short selling. Fully 85% of the surveyed corporate managers

favored reinstituting the short-sale price tests “as soon as practical,” indicating

that managers are aware of and sensitive to the impact of eliminating price

tests on the potential amount of short selling in their firms. The former state

banking superintendent of New York argued that the SEC’s repeal of the price

tests added to market volatility, especially in down markets.9 The Wall Street

Journal argued that SEC (2007) was too biased to evaluate the short-sale price

tests fairly.10 Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, a well-known law firm, argued

that the uptick rule should be reinstated immediately,and three members

of Congress introduced a bill (H.R.6517) requiring the SEC to reinstate the

uptick rule. Presidential candidate Sen. John McCain blamed the SEC for the

recent financial turmoil by “turning our markets into a casino,” in part because

of the increased prospect of short sales, and called for the SEC’s chairman to

be dismissed. In response to this pressure, the SEC partially reversed course

and restored a modified uptick rule on February 24, 2010. Under the new rule,

price tests are triggered when a security’s price declines by 10% or more from

the previous day’s closing price. This policy reversal drew sharp criticism itself,

this time from hedge funds and short sellers.11

B. The Impact of the Pilot Program on Earnings Management

The strong public reactions to changes in the uptick rule indicate that the

rule is important to investors, managers, and politicians. Consistent with prac-

titioners’perception, most prior research indicates that short-sale price tests

impose meaningfulconstraints on short selling,an assumption we examine

further in the next section.12 In this section, we draw from prior studies to

construct our main hypothesis on how changes in the cost of short selling due

to the removal of short-sale price tests, and the corresponding changes in the

prospect of short selling,affect a manager’s tendency to engage in earnings

management.

Previous research indicates that executives have incentives to distort their

firms’ reported financial performance to bolster their compensation,gains

through stock sales, job security, operational flexibility, or control.13 These find-

ings imply that managers can earn a personal benefit from managing earnings

9 Gretchen Morgenson, “Why the roller coaster seems wilder,” The New York Times, August 26,

2007, page 31.

10 See “There’s a better way to prevent bear raids,” The Wall Street Journal, November 18, 2008,

page A19.

11 See “Hedge funds slam short-sale rule,” available at http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2010/02/

25/hedge-funds-slam-short-sale-rule/? r=0.

12 See, for example, McCormick and Reilly (1996), Angel (1997), Alexander and Peterson (1999,

2008),SEC (2007),and Diether,Lee, and Werner (2009).For a contradictory finding,see Ferri,

Christophe, and Angel (2004).

13 For evidence regarding compensation motives, see Bergstresser and Philippon (2006), Burns

and Kedia (2006), and Efendi, Srivastava, and Swanson (2007); for stock sale motives, see Beneish

and Vargus (2002); and for job security and control-related motives, see DeFond and Park (1997),

Ahmed, Lobo, and Zhou (2006), DeFond and Jiambalvo (1994), and Sweeney (1994).

issuers’views on short selling. Fully 85% of the surveyed corporate managers

favored reinstituting the short-sale price tests “as soon as practical,” indicating

that managers are aware of and sensitive to the impact of eliminating price

tests on the potential amount of short selling in their firms. The former state

banking superintendent of New York argued that the SEC’s repeal of the price

tests added to market volatility, especially in down markets.9 The Wall Street

Journal argued that SEC (2007) was too biased to evaluate the short-sale price

tests fairly.10 Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, a well-known law firm, argued

that the uptick rule should be reinstated immediately,and three members

of Congress introduced a bill (H.R.6517) requiring the SEC to reinstate the

uptick rule. Presidential candidate Sen. John McCain blamed the SEC for the

recent financial turmoil by “turning our markets into a casino,” in part because

of the increased prospect of short sales, and called for the SEC’s chairman to

be dismissed. In response to this pressure, the SEC partially reversed course

and restored a modified uptick rule on February 24, 2010. Under the new rule,

price tests are triggered when a security’s price declines by 10% or more from

the previous day’s closing price. This policy reversal drew sharp criticism itself,

this time from hedge funds and short sellers.11

B. The Impact of the Pilot Program on Earnings Management

The strong public reactions to changes in the uptick rule indicate that the

rule is important to investors, managers, and politicians. Consistent with prac-

titioners’perception, most prior research indicates that short-sale price tests

impose meaningfulconstraints on short selling,an assumption we examine

further in the next section.12 In this section, we draw from prior studies to

construct our main hypothesis on how changes in the cost of short selling due

to the removal of short-sale price tests, and the corresponding changes in the

prospect of short selling,affect a manager’s tendency to engage in earnings

management.

Previous research indicates that executives have incentives to distort their

firms’ reported financial performance to bolster their compensation,gains

through stock sales, job security, operational flexibility, or control.13 These find-

ings imply that managers can earn a personal benefit from managing earnings

9 Gretchen Morgenson, “Why the roller coaster seems wilder,” The New York Times, August 26,

2007, page 31.

10 See “There’s a better way to prevent bear raids,” The Wall Street Journal, November 18, 2008,

page A19.

11 See “Hedge funds slam short-sale rule,” available at http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2010/02/

25/hedge-funds-slam-short-sale-rule/? r=0.

12 See, for example, McCormick and Reilly (1996), Angel (1997), Alexander and Peterson (1999,

2008),SEC (2007),and Diether,Lee, and Werner (2009).For a contradictory finding,see Ferri,

Christophe, and Angel (2004).

13 For evidence regarding compensation motives, see Bergstresser and Philippon (2006), Burns

and Kedia (2006), and Efendi, Srivastava, and Swanson (2007); for stock sale motives, see Beneish

and Vargus (2002); and for job security and control-related motives, see DeFond and Park (1997),

Ahmed, Lobo, and Zhou (2006), DeFond and Jiambalvo (1994), and Sweeney (1994).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Short Selling and Earnings Management 1257

to inflate the stock price.Prior research also demonstrates that short sell-

ing facilitates the flow of unfavorable information into stock prices, increases

price efficiency,and dampens the price inflation that motivates managers to

manipulate earnings in the first place (e.g., Miller (1977), Harrison and Kreps

(1978), Chang, Cheng, and Yu (2007), Karpoff and Lou (2010), Boehmer and Wu

(2013)). These findings imply that managers’ benefits of manipulating earnings

decrease with the prospect of short selling because these benefits are at least

partially offset by short sellers’activities.

Although earnings management conveys benefits to managers,managers

cannot manipulate earnings with impunity. Previous research shows that ag-

gressive earnings management is associated with an increased likelihood of

forced CEO turnover (Karpoff, Lee, and Martin (2008), Hazarika, Karpoff, and

Nahata (2012)), and that short sellers monitor managers’reporting behavior

and uncover aggressive earnings management (Efendi, Kinney, and Swanson

(2005),Desai, Krishnamurthy, and Venkataraman (2006),Karpoff and Lou

(2010)). These results indicate that, for a given level of earnings management,

managers’potential costs increase with a reduction in the cost of short selling

and an increase in short sellers’scrutiny.

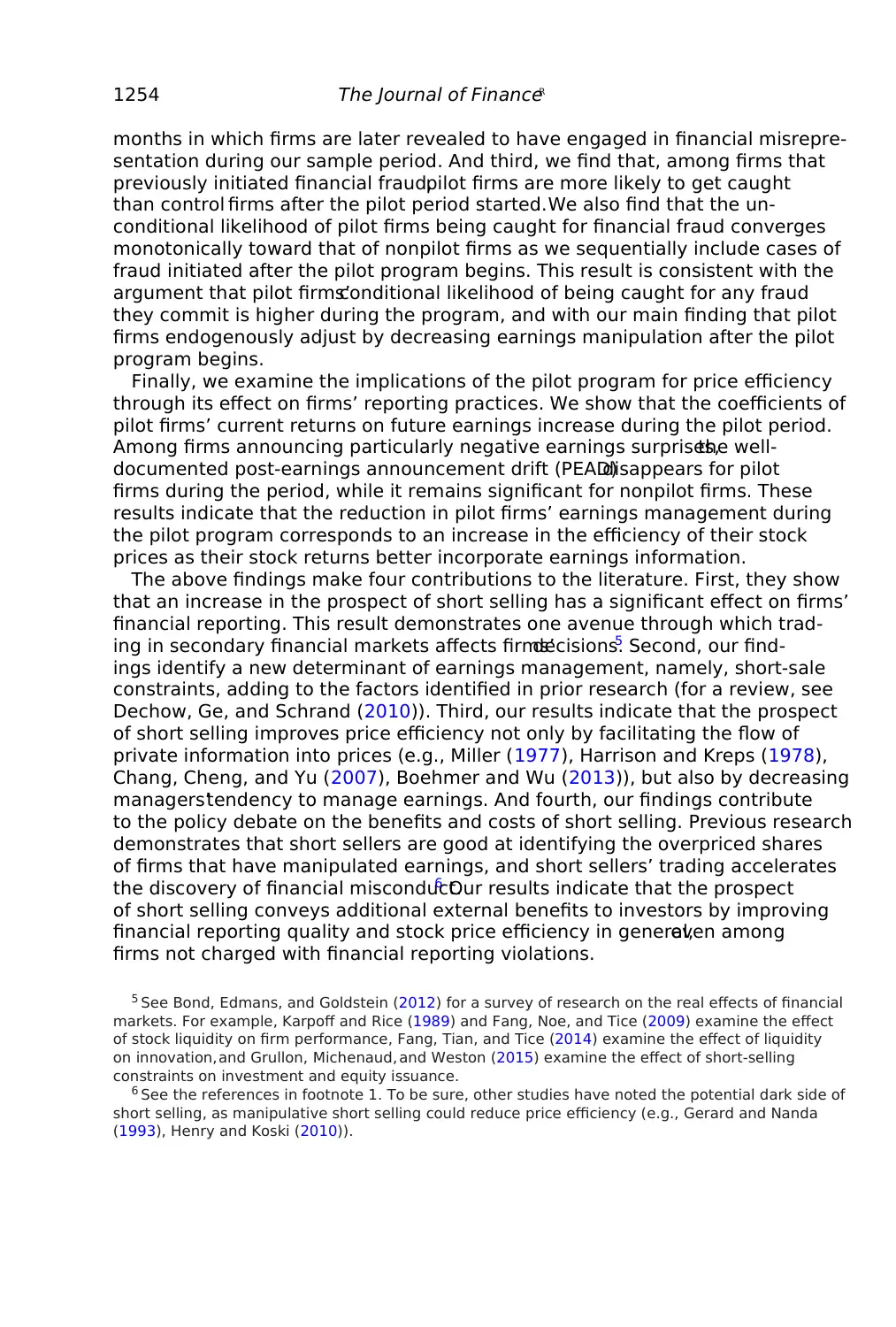

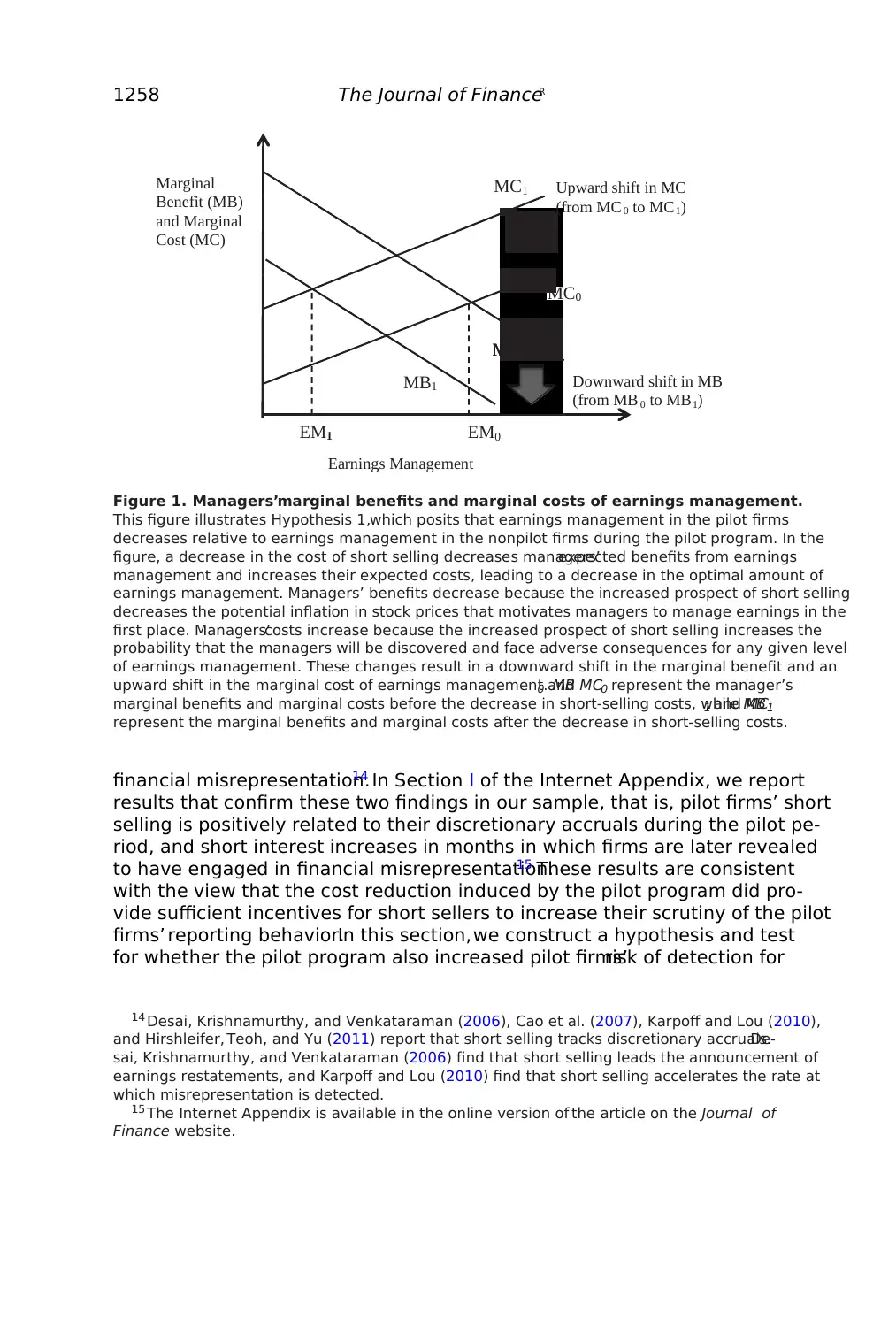

Regulation SHO’s pilot program, which eliminated short-sale price tests for

the pilot stocks,represents an exogenously imposed reduction in the cost of

short selling and hence an increase in the prospect of short selling in these

stocks. The effect was to decrease pilot firm managers’expected benefits and

increase their expected costs of earnings management. These effects on a man-

ager’s earnings management decisions are illustrated in Figure 1. Let MB0 and

MC 0 represent the manager’s marginal benefit and marginal cost of managing

earnings before initiation of the pilot program. In drawing these curves with

their normal slopes,we assume that the benefits from artificialstock price

inflation increase at a decreasing rate in the level of earnings management,

while the costs from the prospect of being discovered increase at an increas-

ing rate. The pre-program optimum amount of earnings management is EM0.

Once the program starts, the marginal benefit and marginal cost of earnings

management shift to MB1 and MC1, and the manager endogenously adjusts by

choosing a new,lower level of earnings management,EM 1. This adjustment

among pilot firms leads to our first hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 1: Earnings management in the pilot firms decreases relative to

earnings management in the nonpilot firms during the pilot program.

C. The Impact of the Pilot Program on Fraud Discovery

In developing Hypothesis 1,we assume that the pilot program had a sub-

stantial enough effect on short sellers’ activities to induce a measurable change

in the pilot firms’financial reporting decisions. Previous research finds that,

in general, short selling tracks firms’ discretionary accruals and helps uncover

to inflate the stock price.Prior research also demonstrates that short sell-

ing facilitates the flow of unfavorable information into stock prices, increases

price efficiency,and dampens the price inflation that motivates managers to

manipulate earnings in the first place (e.g., Miller (1977), Harrison and Kreps

(1978), Chang, Cheng, and Yu (2007), Karpoff and Lou (2010), Boehmer and Wu

(2013)). These findings imply that managers’ benefits of manipulating earnings

decrease with the prospect of short selling because these benefits are at least

partially offset by short sellers’activities.

Although earnings management conveys benefits to managers,managers

cannot manipulate earnings with impunity. Previous research shows that ag-

gressive earnings management is associated with an increased likelihood of

forced CEO turnover (Karpoff, Lee, and Martin (2008), Hazarika, Karpoff, and

Nahata (2012)), and that short sellers monitor managers’reporting behavior

and uncover aggressive earnings management (Efendi, Kinney, and Swanson

(2005),Desai, Krishnamurthy, and Venkataraman (2006),Karpoff and Lou

(2010)). These results indicate that, for a given level of earnings management,

managers’potential costs increase with a reduction in the cost of short selling

and an increase in short sellers’scrutiny.

Regulation SHO’s pilot program, which eliminated short-sale price tests for

the pilot stocks,represents an exogenously imposed reduction in the cost of

short selling and hence an increase in the prospect of short selling in these

stocks. The effect was to decrease pilot firm managers’expected benefits and

increase their expected costs of earnings management. These effects on a man-

ager’s earnings management decisions are illustrated in Figure 1. Let MB0 and

MC 0 represent the manager’s marginal benefit and marginal cost of managing

earnings before initiation of the pilot program. In drawing these curves with

their normal slopes,we assume that the benefits from artificialstock price

inflation increase at a decreasing rate in the level of earnings management,

while the costs from the prospect of being discovered increase at an increas-

ing rate. The pre-program optimum amount of earnings management is EM0.

Once the program starts, the marginal benefit and marginal cost of earnings

management shift to MB1 and MC1, and the manager endogenously adjusts by

choosing a new,lower level of earnings management,EM 1. This adjustment

among pilot firms leads to our first hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 1: Earnings management in the pilot firms decreases relative to

earnings management in the nonpilot firms during the pilot program.

C. The Impact of the Pilot Program on Fraud Discovery

In developing Hypothesis 1,we assume that the pilot program had a sub-

stantial enough effect on short sellers’ activities to induce a measurable change

in the pilot firms’financial reporting decisions. Previous research finds that,

in general, short selling tracks firms’ discretionary accruals and helps uncover

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1258 The Journal of FinanceR

MC1

MC0

MB1

MB0

Marginal

Benefit (MB)

and Marginal

Cost (MC)

Earnings Management

EM0EM1

M

MB0

Upward shift in MC

(from MC 0 to MC1)

Downward shift in MB

(from MB 0 to MB1)

Figure 1. Managers’marginal benefits and marginal costs of earnings management.

This figure illustrates Hypothesis 1,which posits that earnings management in the pilot firms

decreases relative to earnings management in the nonpilot firms during the pilot program. In the

figure, a decrease in the cost of short selling decreases managers’expected benefits from earnings

management and increases their expected costs, leading to a decrease in the optimal amount of

earnings management. Managers’ benefits decrease because the increased prospect of short selling

decreases the potential inflation in stock prices that motivates managers to manage earnings in the

first place. Managers’costs increase because the increased prospect of short selling increases the

probability that the managers will be discovered and face adverse consequences for any given level

of earnings management. These changes result in a downward shift in the marginal benefit and an

upward shift in the marginal cost of earnings management. MB0 and MC0 represent the manager’s

marginal benefits and marginal costs before the decrease in short-selling costs, while MB1 and MC1

represent the marginal benefits and marginal costs after the decrease in short-selling costs.

financial misrepresentation.14 In Section I of the Internet Appendix, we report

results that confirm these two findings in our sample, that is, pilot firms’ short

selling is positively related to their discretionary accruals during the pilot pe-

riod, and short interest increases in months in which firms are later revealed

to have engaged in financial misrepresentation.15 These results are consistent

with the view that the cost reduction induced by the pilot program did pro-

vide sufficient incentives for short sellers to increase their scrutiny of the pilot

firms’ reporting behavior.In this section,we construct a hypothesis and test

for whether the pilot program also increased pilot firms’risk of detection for

14 Desai, Krishnamurthy, and Venkataraman (2006), Cao et al. (2007), Karpoff and Lou (2010),

and Hirshleifer, Teoh, and Yu (2011) report that short selling tracks discretionary accruals.De-

sai, Krishnamurthy, and Venkataraman (2006) find that short selling leads the announcement of

earnings restatements, and Karpoff and Lou (2010) find that short selling accelerates the rate at

which misrepresentation is detected.

15 The Internet Appendix is available in the online version of the article on the Journal of

Finance website.

MC1

MC0

MB1

MB0

Marginal

Benefit (MB)

and Marginal

Cost (MC)

Earnings Management

EM0EM1

M

MB0

Upward shift in MC

(from MC 0 to MC1)

Downward shift in MB

(from MB 0 to MB1)

Figure 1. Managers’marginal benefits and marginal costs of earnings management.

This figure illustrates Hypothesis 1,which posits that earnings management in the pilot firms

decreases relative to earnings management in the nonpilot firms during the pilot program. In the

figure, a decrease in the cost of short selling decreases managers’expected benefits from earnings

management and increases their expected costs, leading to a decrease in the optimal amount of

earnings management. Managers’ benefits decrease because the increased prospect of short selling

decreases the potential inflation in stock prices that motivates managers to manage earnings in the

first place. Managers’costs increase because the increased prospect of short selling increases the

probability that the managers will be discovered and face adverse consequences for any given level

of earnings management. These changes result in a downward shift in the marginal benefit and an

upward shift in the marginal cost of earnings management. MB0 and MC0 represent the manager’s

marginal benefits and marginal costs before the decrease in short-selling costs, while MB1 and MC1

represent the marginal benefits and marginal costs after the decrease in short-selling costs.

financial misrepresentation.14 In Section I of the Internet Appendix, we report

results that confirm these two findings in our sample, that is, pilot firms’ short

selling is positively related to their discretionary accruals during the pilot pe-

riod, and short interest increases in months in which firms are later revealed

to have engaged in financial misrepresentation.15 These results are consistent

with the view that the cost reduction induced by the pilot program did pro-

vide sufficient incentives for short sellers to increase their scrutiny of the pilot

firms’ reporting behavior.In this section,we construct a hypothesis and test

for whether the pilot program also increased pilot firms’risk of detection for

14 Desai, Krishnamurthy, and Venkataraman (2006), Cao et al. (2007), Karpoff and Lou (2010),

and Hirshleifer, Teoh, and Yu (2011) report that short selling tracks discretionary accruals.De-

sai, Krishnamurthy, and Venkataraman (2006) find that short selling leads the announcement of

earnings restatements, and Karpoff and Lou (2010) find that short selling accelerates the rate at

which misrepresentation is detected.

15 The Internet Appendix is available in the online version of the article on the Journal of

Finance website.

Short Selling and Earnings Management 1259

earnings manipulation that rises to the level of financial misrepresentation or

fraud.16

We begin by noting that there is generally a time lag between when a firm

begins misrepresenting its earnings and when the misrepresentation is de-

tected.Karpoff and Lou (2010)report that this lag varies across firms and

has a median of 26 months in their sample. We therefore characterize a firm’s

conditional probability of being caught as

Pr (Caught(t + n) |Fraud (t)) = δ n

s=0msSSP (t + s) . (1)

In equation (1), Pr(Caught(t + n)|Fraud(t)) is the firm’s probability of being

caught at time t + n conditional on misrepresenting at time t, where n ࣙ 0. On

the right-hand side, SSP(t + s) is short selling potential at time t + s; we expect

this potential to be higher for pilot firms when t + s falls within the pilot period.

We use ms to denote the individual weight each period’s short-selling potential

contributes to the conditional probability of detection. This weight depends on

the wide range of non short-selling factors that affect a firm’s probability of

being caught. We hypothesize that an increase in short-selling potential helps

uncover aggressive reporting, that is, δ > 0. This leads to our second hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 2: Conditional on misreporting,pilot firms are more likely than

nonpilot firms to get caught after the pilot program begins.

A challenge in testing Hypothesis 2 is that we do not directly observe the

conditional probability of detection,but rather the unconditional probability

that a firm both commits fraud and is detected, which can be expressed as

Pr Caught(t + n) , Fraud (t) = Pr (Fraud (t))× Pr Caught(t + n) |Fraud (t) . (2)

To test Hypothesis 2, we exploit the time lag between the commission and

detection of fraud. Since the pilot firms are randomly selected, it is reasonable

to assume that, before the pilot program was announced in July 2004, the actual

rate of fraud commission was equal between the pilot and nonpilot firms, that

is, Pr(Fraud(t))pilot = Pr(Fraud(t))nonpilot for t < July 2004.17 This allows us to

use the unconditional probability of detection for fraud initiated before the pilot

program was announced in July 2004 but detected after the program began in

May 2005 to infer the conditional probability of getting caught. Hypothesis 2

then implies that

Pr (Caught(post-May 2005) , Fraud (pre-July 2004))pilot >

Pr (Caught(post-May 2005) , Fraud (pre-July 2004))nonpilot.

16 Karpoff et al. (2016) point out that many instances of financial misrepresentation do not in-

clude charges of fraud. We nonetheless use the term “fraud” to refer to any illegal misrepresentation

that attracts SEC enforcement action.

17 We restrict t to the period before the announcement of the pilot program (in July 2004) to

ensure that the expected rate of fraud commission is equal across the two groups of firms. Whereas

short sellers arguably begin to change their behavior after the pilot program is implemented in

May 2005, managers of pilot firms could change their reporting behavior in response to the prospect

of short selling as early as when they learn the identity of the pilot stocks in July 2004.

earnings manipulation that rises to the level of financial misrepresentation or

fraud.16

We begin by noting that there is generally a time lag between when a firm

begins misrepresenting its earnings and when the misrepresentation is de-

tected.Karpoff and Lou (2010)report that this lag varies across firms and

has a median of 26 months in their sample. We therefore characterize a firm’s

conditional probability of being caught as

Pr (Caught(t + n) |Fraud (t)) = δ n

s=0msSSP (t + s) . (1)

In equation (1), Pr(Caught(t + n)|Fraud(t)) is the firm’s probability of being

caught at time t + n conditional on misrepresenting at time t, where n ࣙ 0. On

the right-hand side, SSP(t + s) is short selling potential at time t + s; we expect

this potential to be higher for pilot firms when t + s falls within the pilot period.

We use ms to denote the individual weight each period’s short-selling potential

contributes to the conditional probability of detection. This weight depends on

the wide range of non short-selling factors that affect a firm’s probability of

being caught. We hypothesize that an increase in short-selling potential helps

uncover aggressive reporting, that is, δ > 0. This leads to our second hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 2: Conditional on misreporting,pilot firms are more likely than

nonpilot firms to get caught after the pilot program begins.

A challenge in testing Hypothesis 2 is that we do not directly observe the

conditional probability of detection,but rather the unconditional probability

that a firm both commits fraud and is detected, which can be expressed as

Pr Caught(t + n) , Fraud (t) = Pr (Fraud (t))× Pr Caught(t + n) |Fraud (t) . (2)

To test Hypothesis 2, we exploit the time lag between the commission and

detection of fraud. Since the pilot firms are randomly selected, it is reasonable

to assume that, before the pilot program was announced in July 2004, the actual

rate of fraud commission was equal between the pilot and nonpilot firms, that

is, Pr(Fraud(t))pilot = Pr(Fraud(t))nonpilot for t < July 2004.17 This allows us to

use the unconditional probability of detection for fraud initiated before the pilot

program was announced in July 2004 but detected after the program began in

May 2005 to infer the conditional probability of getting caught. Hypothesis 2

then implies that

Pr (Caught(post-May 2005) , Fraud (pre-July 2004))pilot >

Pr (Caught(post-May 2005) , Fraud (pre-July 2004))nonpilot.

16 Karpoff et al. (2016) point out that many instances of financial misrepresentation do not in-

clude charges of fraud. We nonetheless use the term “fraud” to refer to any illegal misrepresentation

that attracts SEC enforcement action.

17 We restrict t to the period before the announcement of the pilot program (in July 2004) to

ensure that the expected rate of fraud commission is equal across the two groups of firms. Whereas

short sellers arguably begin to change their behavior after the pilot program is implemented in

May 2005, managers of pilot firms could change their reporting behavior in response to the prospect

of short selling as early as when they learn the identity of the pilot stocks in July 2004.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1260 The Journal of FinanceR

Once the pilot program was announced, Hypothesis 1 implies that managers

of the pilot firms endogenously began to adjust to the higher conditional prob-

ability of detection by decreasing earnings management, that is,

Pr (Fraud (t))pilot < Pr (Fraud (t))nonpilot for t > July 2004.

The pilot program therefore has two offsetting effects on the unconditional

probability of detection for fraud committed after July 2004: pilot firms commit

fewer frauds, but conditional on committing fraud, they are more likely to be

caught.This implies that the difference between pilot and nonpilot firms in

the unconditional likelihood of fraud detection should decrease as we consider

fraud initiated after July 2004. Section IV reports results that support these

implications of Hypothesis 2.

D. Related Research

Our investigation is related to the small but growing literature that exploits

changes in short-sale regulations to examine the economic implications of short

selling. Autore, Billingsley, and Kovacs (2011), Frino, Lecce, and Lepone (2011),

and Boehmer, Jones, and Zhang (2013) examine the impact of a widespread ban

on short selling in U.S. equity markets in 2008, and Beber and Pagano (2013)

examine the impacts ofshort-selling bans around the world.These studies

conclude that short-selling bans decrease various measures of market quality.

Using Regulation SHO’s Rule 202T pilot program, Alexander and Peterson

(2008)find that order execution and market quality improved for the pilot

stocks during the pilot program.Diether, Lee, and Werner (2009) and SEC

(2007) show that pilot stocks listed on both NYSE and NASDAQ experienced a

significant increase in short-sale trades and in the ratio of short sales to share

volume during the term of the pilot program. The former also shows that NYSE-

listed pilot stocks experienced a higher level of order-splitting, suggesting that

short sellers apply more active trading strategies.Other papers relate the

pilot program to firm outcomes.Grullon, Michenaud,and Weston (2015),for

example,examine the effect of the pilot program on pilot firms’stock prices,

equity issuance, and investment. Kecsk´es, Mansi, and Zhang (2013) study bond

yields, De Angelis, Grullon, and Michenaud (2015) equity incentives, He and

Tian (2014) corporate innovation,and Li and Zhang (2015) firms’voluntary

disclosure practices.

In our main analyses, we use the experiment created by the pilot program

to examine the effect ofshort-selling costs on firms’earnings management

decisions.This experiment is well suited for our research question, as it

facilitates DiD comparisons of pilot vs. nonpilot firms’earnings management

before, during, and after the pilot program. The DiD tests allow us to control

for time trends that may be common to both the pilot and nonpilot firms,

and mitigate concerns about reverse causality or omitted variables (because

the SEC assigned pilot stocks arbitrarily).This experimental design is thus

superior to a blanket ban of short selling that applies to the entire cross-section

Once the pilot program was announced, Hypothesis 1 implies that managers

of the pilot firms endogenously began to adjust to the higher conditional prob-

ability of detection by decreasing earnings management, that is,

Pr (Fraud (t))pilot < Pr (Fraud (t))nonpilot for t > July 2004.

The pilot program therefore has two offsetting effects on the unconditional

probability of detection for fraud committed after July 2004: pilot firms commit

fewer frauds, but conditional on committing fraud, they are more likely to be

caught.This implies that the difference between pilot and nonpilot firms in

the unconditional likelihood of fraud detection should decrease as we consider

fraud initiated after July 2004. Section IV reports results that support these

implications of Hypothesis 2.

D. Related Research

Our investigation is related to the small but growing literature that exploits

changes in short-sale regulations to examine the economic implications of short

selling. Autore, Billingsley, and Kovacs (2011), Frino, Lecce, and Lepone (2011),

and Boehmer, Jones, and Zhang (2013) examine the impact of a widespread ban

on short selling in U.S. equity markets in 2008, and Beber and Pagano (2013)

examine the impacts ofshort-selling bans around the world.These studies

conclude that short-selling bans decrease various measures of market quality.

Using Regulation SHO’s Rule 202T pilot program, Alexander and Peterson

(2008)find that order execution and market quality improved for the pilot

stocks during the pilot program.Diether, Lee, and Werner (2009) and SEC

(2007) show that pilot stocks listed on both NYSE and NASDAQ experienced a

significant increase in short-sale trades and in the ratio of short sales to share

volume during the term of the pilot program. The former also shows that NYSE-

listed pilot stocks experienced a higher level of order-splitting, suggesting that

short sellers apply more active trading strategies.Other papers relate the

pilot program to firm outcomes.Grullon, Michenaud,and Weston (2015),for

example,examine the effect of the pilot program on pilot firms’stock prices,

equity issuance, and investment. Kecsk´es, Mansi, and Zhang (2013) study bond

yields, De Angelis, Grullon, and Michenaud (2015) equity incentives, He and

Tian (2014) corporate innovation,and Li and Zhang (2015) firms’voluntary

disclosure practices.

In our main analyses, we use the experiment created by the pilot program

to examine the effect ofshort-selling costs on firms’earnings management

decisions.This experiment is well suited for our research question, as it

facilitates DiD comparisons of pilot vs. nonpilot firms’earnings management

before, during, and after the pilot program. The DiD tests allow us to control

for time trends that may be common to both the pilot and nonpilot firms,

and mitigate concerns about reverse causality or omitted variables (because

the SEC assigned pilot stocks arbitrarily).This experimental design is thus

superior to a blanket ban of short selling that applies to the entire cross-section

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Short Selling and Earnings Management 1261

of firms because the latter can be muddled by possible confounding events. For

example, changes in accruals following the blanket ban on short selling during

the recent financial crisis could be associated with economy-wide changes in

investment opportunities rather than changes in short-selling regulations.

A contemporaneous paper by Massa, Zhang, and Zhang (MZZ, 2015) also in-

vestigates the effects of short selling on firms’ earnings management. Whereas

we use the exogenous variation in firms’ short-selling costs created by the pilot

program to identify our tests, MZZ focus on 33 international markets and use

the amount of shares available for lending to measure short-selling potential.

Like us, MZZ also infer that short selling plays a disciplinary role in deterring

firms’opportunistic reporting behavior.

II. Data

A. Sample

On July 28, 2004, the SEC issued its first pilot order (Securities Exchange

Act Release No.50104) and published a list of 986 stocks that would trade

without being subject to any price tests during the term of the pilot program

(available at http://www.sec.gov/rules/other/34-50104.htm). To create this list,

the SEC started with 2004 Russell 3000 index members and excluded stocks

that were not previously subject to price tests (i.e., not listed on NYSE, Amex,

or NASDAQ-NM) and stocks that went public or had spin-offs after April 30,

2004.The remaining stocks were then sorted by their average daily dollar

volume computed over the June 2003 to May 2004 period within each of the

three listing markets. Every third stock (beginning with the second one) within

each listing market was designated as a pilot stock.

Based on the description in the SEC’s pilot orders and its report on the pilot

program (SEC (2007)),we identify an initial sample of 986 pilot stocks and

1,966 nonpilot stocks.18 An examination of the exchange distribution of these

stocks shows that both the pilot and the nonpilot groups are representative

of the Russell 3000 index,confirming the statistics reported by SEC (2007).

Specifically,of the 986 pilot stocks,49.9% (492) are listed on NYSE,47.9%

(472) on NASDAQ-NM, and 2.2% (22) on Amex. The exchange distribution of

nonpilot stocks is very similar, with 50% (982) listed on NYSE, 48% (944) on

NASDAQ-NM, and 2% (40) on Amex.

In our tests, we delete firms in the financial services (SIC 6000–6999)

and utilities (SIC 4900–4949) industries because disclosure requirements,

18 We use Thomson Reuters’s Securities Data Company (SDC) Platinum database and the Com-

pustat database to identify firms that went public or had spinoffs after April 30,2004,and the

CRSP monthly files to identify stocks that are not exchange-listed,and exclude all such stocks

from the nonpilot sample.The SEC did not publish the final list of nonpilot stocks in its 2007

analysis, but any discrepancies between the SEC’s sample and our sample of nonpilot stocks are

likely to be immaterial. Further, firms that are not exchange-listed or that had significant changes

in ownership structure around the pilot program are likely to be excluded from our tests because

our main tests require that the sample firms have financial data each year from 2001 to 2003

(inclusive) and 2005 to 2010 (inclusive).

of firms because the latter can be muddled by possible confounding events. For

example, changes in accruals following the blanket ban on short selling during

the recent financial crisis could be associated with economy-wide changes in

investment opportunities rather than changes in short-selling regulations.

A contemporaneous paper by Massa, Zhang, and Zhang (MZZ, 2015) also in-

vestigates the effects of short selling on firms’ earnings management. Whereas

we use the exogenous variation in firms’ short-selling costs created by the pilot

program to identify our tests, MZZ focus on 33 international markets and use

the amount of shares available for lending to measure short-selling potential.

Like us, MZZ also infer that short selling plays a disciplinary role in deterring

firms’opportunistic reporting behavior.

II. Data

A. Sample

On July 28, 2004, the SEC issued its first pilot order (Securities Exchange

Act Release No.50104) and published a list of 986 stocks that would trade

without being subject to any price tests during the term of the pilot program

(available at http://www.sec.gov/rules/other/34-50104.htm). To create this list,

the SEC started with 2004 Russell 3000 index members and excluded stocks

that were not previously subject to price tests (i.e., not listed on NYSE, Amex,

or NASDAQ-NM) and stocks that went public or had spin-offs after April 30,

2004.The remaining stocks were then sorted by their average daily dollar

volume computed over the June 2003 to May 2004 period within each of the

three listing markets. Every third stock (beginning with the second one) within

each listing market was designated as a pilot stock.

Based on the description in the SEC’s pilot orders and its report on the pilot

program (SEC (2007)),we identify an initial sample of 986 pilot stocks and

1,966 nonpilot stocks.18 An examination of the exchange distribution of these

stocks shows that both the pilot and the nonpilot groups are representative

of the Russell 3000 index,confirming the statistics reported by SEC (2007).

Specifically,of the 986 pilot stocks,49.9% (492) are listed on NYSE,47.9%

(472) on NASDAQ-NM, and 2.2% (22) on Amex. The exchange distribution of

nonpilot stocks is very similar, with 50% (982) listed on NYSE, 48% (944) on

NASDAQ-NM, and 2% (40) on Amex.

In our tests, we delete firms in the financial services (SIC 6000–6999)

and utilities (SIC 4900–4949) industries because disclosure requirements,

18 We use Thomson Reuters’s Securities Data Company (SDC) Platinum database and the Com-

pustat database to identify firms that went public or had spinoffs after April 30,2004,and the

CRSP monthly files to identify stocks that are not exchange-listed,and exclude all such stocks

from the nonpilot sample.The SEC did not publish the final list of nonpilot stocks in its 2007

analysis, but any discrepancies between the SEC’s sample and our sample of nonpilot stocks are

likely to be immaterial. Further, firms that are not exchange-listed or that had significant changes

in ownership structure around the pilot program are likely to be excluded from our tests because

our main tests require that the sample firms have financial data each year from 2001 to 2003

(inclusive) and 2005 to 2010 (inclusive).

1262 The Journal of FinanceR

accounting rules,and processes by which accruals are generated are signif-

icantly different for these regulated industries.A further complication with

financial stocks is the 2008 short-sale ban imposed on this sector.We obtain

data from the Compustat Industrial Annual Files to construct earnings man-

agement proxies and controlvariables.In most tests, we require that firms

have data to calculate firm characteristics over the entire sample period, that

is, 2001 to 2003 (inclusive) and 2005 to 2010 (inclusive). The resulting balanced

panel sample consists of 388 pilot firms and 709 nonpilot firms. If we relax this

requirement, our unbalanced panel sample contains 741 to 782 pilot firms and

1,504 to 1,610 nonpilot firms in the year immediately before the announcement

of the pilot program (i.e., 2003), depending on data availability to calculate a

given firm characteristic.We emphasize the results from the balanced panel

sample,but also report results for the unbalanced sample.Throughout,the

results are similar using either sample.

B. Key Test Variables