Engage in Collaborative Alliances - BSBPMG637 Task 2 Written Report

VerifiedAdded on 2022/01/21

|49

|21952

|46

Report

AI Summary

This report, completed as part of the BSBPMG637 unit, focuses on developing a collaborative alliance with a social media company to increase customer base. The assignment involves researching a social media company and creating a collaboration agreement. The report analyzes various partnership categories such as marketing, advertising, rewards programs, events, and sponsorship. It explores the importance of humanizing brands in B2B social media, highlighting the need for constant attention and experimentation. The report references successful joint campaigns and emphasizes the value of audience engagement and content creation. It also discusses different types of joint campaigns, including partnerships, collaborations, cross-promotions, content placement, and value-add strategies, while stressing the importance of respecting the audience. The report emphasizes the potential for brands to leverage their assets through collaborations and partnerships to extend their marketing impact. Finally, it provides examples of successful joint campaigns, such as Taco Bell's partnership with Frito-Lay and the Campari Group's campaign with Deadpool, illustrating how different brands can work together to benefit their audiences.

BSBPMG637 Engage in collaborative alliances

Task 2 – Written Report

Task summary

This assessment is to be completed using the case study provided.

Required

Access to textbooks/other learning materials

Access to Canvas

Computer with Microsoft Office and internet access

Timing

Your assessor will advise you of the due date of this assessment via Canvas.

Submit

This completed workbook.

Assessment criteria

For your performance to be deemed satisfactory in this assessment task, you must satisfactorily

address all the assessment criteria. If part of this task is not satisfactorily completed, you will be asked

to complete further assessment to demonstrate competence.

Re-submission opportunities

You will be provided feedback on your performance by the Assessor. The feedback will indicate if you

have satisfactorily addressed the requirements of each part of this task.

If any parts of the task are not satisfactorily completed, the assessor will explain why, and provide you

written feedback along with guidance on what you must undertake to demonstrate satisfactory

performance. Re-assessment attempt(s) will be arranged at a later time and date.

You have the right to appeal the outcome of assessment decisions if you feel that you have been dealt

with unfairly or have other appropriate grounds for an appeal.

You are encouraged to consult with the assessor prior to attempting this task if you do not understand

any part of this task or if you have any learning issues or needs that may hinder you when attempting

any part of the assessment.

Assessment Cover Sheet

IH Sydney Training Services Pty Ltd

RTO Code: 91109 CRICOS Code: 02623G

Task 2 – Written Report

Task summary

This assessment is to be completed using the case study provided.

Required

Access to textbooks/other learning materials

Access to Canvas

Computer with Microsoft Office and internet access

Timing

Your assessor will advise you of the due date of this assessment via Canvas.

Submit

This completed workbook.

Assessment criteria

For your performance to be deemed satisfactory in this assessment task, you must satisfactorily

address all the assessment criteria. If part of this task is not satisfactorily completed, you will be asked

to complete further assessment to demonstrate competence.

Re-submission opportunities

You will be provided feedback on your performance by the Assessor. The feedback will indicate if you

have satisfactorily addressed the requirements of each part of this task.

If any parts of the task are not satisfactorily completed, the assessor will explain why, and provide you

written feedback along with guidance on what you must undertake to demonstrate satisfactory

performance. Re-assessment attempt(s) will be arranged at a later time and date.

You have the right to appeal the outcome of assessment decisions if you feel that you have been dealt

with unfairly or have other appropriate grounds for an appeal.

You are encouraged to consult with the assessor prior to attempting this task if you do not understand

any part of this task or if you have any learning issues or needs that may hinder you when attempting

any part of the assessment.

Assessment Cover Sheet

IH Sydney Training Services Pty Ltd

RTO Code: 91109 CRICOS Code: 02623G

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Candidate name:

Candidate ID

Trainer’s Name:

Date Submitted:

Candidate

declaration:

I declare that:

I have read and understood all the information provided in relation to

the assessment requirements to complete this unit, the instructions

and the purpose and processes of undertaking this assessment task

This assessment is my own work and where other’s works or ideas have

been used, I have appropriately referenced or acknowledged them

I understand that plagiarism is a serious offence that may lead to

disciplinary action.

Candidate signature:

2 | P a g e

Candidate ID

Trainer’s Name:

Date Submitted:

Candidate

declaration:

I declare that:

I have read and understood all the information provided in relation to

the assessment requirements to complete this unit, the instructions

and the purpose and processes of undertaking this assessment task

This assessment is my own work and where other’s works or ideas have

been used, I have appropriately referenced or acknowledged them

I understand that plagiarism is a serious offence that may lead to

disciplinary action.

Candidate signature:

2 | P a g e

Task 2 –Written Report

You are currently the project manager and you would like to develop a partnership or alliance with an

existing company or business to increase your own customer base. This can be done through a number

or ways from marketing, sharing adverting costs, sharing the costs of a project or event. You may

choose from one of the following choices:

1. Construction Company

2. Social Media Company

3. Fashion Label

4. Restaurant / Café

5. BYO

I want to choose second option for this written repot.

Social Media Company

Any executive or marketing director working in professional services knows how rapidly change occurs

in B2B marketing. And of the various spaces included in most marketing plans, B2B social media wins

the superlative for most likely to change again tomorrow.

The world of B2B social media is frustrating — often leaving marketing directors disoriented because

what was working three months ago doesn’t work anymore. Professionals building their personal

brands face a similar challenge. An endless stream of new features… More ways to analyze data…

Emerging platforms to join… How can you keep up? Inevitably this means that a good B2B social media

strategy requires constant attention and experimentation.

But what if there were some foundations you could always rely on when building your B2B social

media content strategy? In this article, we’re going to look beyond the unpredictable updates that

each platform releases and focus on two evergreen rules that are here to stay.

Rule #1 – Be Human.

Professionals who spend time on social media are doing so for a variety of reasons, ranging from

researching competitors to recruiting new employees. But one business purpose for being on social

media stands taller than the rest — networking with people you know and people you want to know.

Put another way, the chief business purpose of social media is to connect and engage with people.

These people include potential and existing clients, referral sources, other thought leaders and

possible recruits. Social media is so effective because we are always curious about what certain

individuals are doing, experiencing, learning and accomplishing. So if connecting with people is the

driving force behind social media, why do so many firms neglect to humanize their brands in this

space?

3 | P a g e

You are currently the project manager and you would like to develop a partnership or alliance with an

existing company or business to increase your own customer base. This can be done through a number

or ways from marketing, sharing adverting costs, sharing the costs of a project or event. You may

choose from one of the following choices:

1. Construction Company

2. Social Media Company

3. Fashion Label

4. Restaurant / Café

5. BYO

I want to choose second option for this written repot.

Social Media Company

Any executive or marketing director working in professional services knows how rapidly change occurs

in B2B marketing. And of the various spaces included in most marketing plans, B2B social media wins

the superlative for most likely to change again tomorrow.

The world of B2B social media is frustrating — often leaving marketing directors disoriented because

what was working three months ago doesn’t work anymore. Professionals building their personal

brands face a similar challenge. An endless stream of new features… More ways to analyze data…

Emerging platforms to join… How can you keep up? Inevitably this means that a good B2B social media

strategy requires constant attention and experimentation.

But what if there were some foundations you could always rely on when building your B2B social

media content strategy? In this article, we’re going to look beyond the unpredictable updates that

each platform releases and focus on two evergreen rules that are here to stay.

Rule #1 – Be Human.

Professionals who spend time on social media are doing so for a variety of reasons, ranging from

researching competitors to recruiting new employees. But one business purpose for being on social

media stands taller than the rest — networking with people you know and people you want to know.

Put another way, the chief business purpose of social media is to connect and engage with people.

These people include potential and existing clients, referral sources, other thought leaders and

possible recruits. Social media is so effective because we are always curious about what certain

individuals are doing, experiencing, learning and accomplishing. So if connecting with people is the

driving force behind social media, why do so many firms neglect to humanize their brands in this

space?

3 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

By humanizing your brand on social media, we mean bringing a human touch to every piece of content

you share.

For example, the articles you shared were all written by individuals. Have you tagged them in your

post, highlighting their individual expertise?

And what about your firm’s news? Aren’t most of these updates related to the achievements of

individual people? Have you shared a picture showing them in action?

And finally, are people on social media interacting with your posts? If so, have you responded to them?

All of them? And have you reciprocated the interaction?

On this point we are inspired by the work of Mark Schaefer, who authored the book Marketing

Rebellion: The Most Human Company Wins. On his blog, Schaefer writes, “In the past, our businesses

were built through an accumulation of advertising impressions. Today, our brands will be known, at

least in part, though an accumulation of human impressions.” What Schaefer wants business leaders

and marketers to understand is that the future of marketing is being driven by authentic human

expression.

So when it comes to your B2B social media strategy, highlight the humanity behind your brand.

Allow the voices behind your content to be heard and bring visibility to the individuals at your firm

doing excellent work for your clients.

WHAT TO DO:

Encourage thought leaders at your firm to become Visible Experts®.

Tag individuals in every post you share on social media and list them as authors on your website

Celebrate and promote the achievements of your business partners and clients

WHAT NOT TO DO:

Maintain overly rigorous standards for sharing content

Hide who authored content on your page

Forbid staff from using social media during business hours

Once you have selected an area to focus in, you are to research one of the above categories, and then

develop a Collaboration Agreement in Part C to submit to the intended company. The partnership or

alliance can include one of the following categories:

a. Marketing

b. Advertising

4 | P a g e

you share.

For example, the articles you shared were all written by individuals. Have you tagged them in your

post, highlighting their individual expertise?

And what about your firm’s news? Aren’t most of these updates related to the achievements of

individual people? Have you shared a picture showing them in action?

And finally, are people on social media interacting with your posts? If so, have you responded to them?

All of them? And have you reciprocated the interaction?

On this point we are inspired by the work of Mark Schaefer, who authored the book Marketing

Rebellion: The Most Human Company Wins. On his blog, Schaefer writes, “In the past, our businesses

were built through an accumulation of advertising impressions. Today, our brands will be known, at

least in part, though an accumulation of human impressions.” What Schaefer wants business leaders

and marketers to understand is that the future of marketing is being driven by authentic human

expression.

So when it comes to your B2B social media strategy, highlight the humanity behind your brand.

Allow the voices behind your content to be heard and bring visibility to the individuals at your firm

doing excellent work for your clients.

WHAT TO DO:

Encourage thought leaders at your firm to become Visible Experts®.

Tag individuals in every post you share on social media and list them as authors on your website

Celebrate and promote the achievements of your business partners and clients

WHAT NOT TO DO:

Maintain overly rigorous standards for sharing content

Hide who authored content on your page

Forbid staff from using social media during business hours

Once you have selected an area to focus in, you are to research one of the above categories, and then

develop a Collaboration Agreement in Part C to submit to the intended company. The partnership or

alliance can include one of the following categories:

a. Marketing

b. Advertising

4 | P a g e

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

c. Rewards Programs

d. Events

e. Sponsorship

Rewards Programs

The pace and competitiveness of social media marketing often narrow our focus to a cycle of making

content and then pushing it through platforms of choice using the latest and greatest best practices.

The potential return on building and serving an audience with this approach is significant. However, as

we look for more ways to compete and more ways to engage, we should step back to evaluate the full

breadth of assets we develop as social media marketers and look to leverage all of them in a unique

way.

Your social media audience and the content you create to engage them are more versatile marketing

assets than you might realize.

The audience you build isn’t only a pool of customers to target. The content you create isn’t simply a

means to engage your audience.

Think of your content as an access road to your audience. If that access road and audience are high

quality, other brands will find value in the path you’ve created.

You can use these assets to extend the impact of your marketing through partnerships, cross-

promotions, and other off-social marketing activities to reach and deepen your impact with audiences

new and old.

5 Types of Joint Campaigns

The heart of this approach to marketing is the classic idea of bartering. Your audience and your

content have value, and you can trade that value to another brand to advance your strategic goals.

That said, you must make these trades in a way that doesn’t compromise the integrity of your brand,

or the trust you worked so hard to build between your brand and your audience. When a trade is

done well, your audience should actually benefit.

From a high-level perspective, these trades usually involve one of the following:

Partnerships: You enter into an agreement (formal or informal) to jointly pursue an objective with

another brand for the long-term. Along the way, you share rewards like revenue or leads.

Collaboration: You join forces with another brand to work on a short-term project or campaign, and

share the rewards. The popular practice of co-branding falls under this category, though the true

scope can be deeper.

Cross-promotion: You and another brand agree to promote each other’s products and services to

your respective audiences.

5 | P a g e

d. Events

e. Sponsorship

Rewards Programs

The pace and competitiveness of social media marketing often narrow our focus to a cycle of making

content and then pushing it through platforms of choice using the latest and greatest best practices.

The potential return on building and serving an audience with this approach is significant. However, as

we look for more ways to compete and more ways to engage, we should step back to evaluate the full

breadth of assets we develop as social media marketers and look to leverage all of them in a unique

way.

Your social media audience and the content you create to engage them are more versatile marketing

assets than you might realize.

The audience you build isn’t only a pool of customers to target. The content you create isn’t simply a

means to engage your audience.

Think of your content as an access road to your audience. If that access road and audience are high

quality, other brands will find value in the path you’ve created.

You can use these assets to extend the impact of your marketing through partnerships, cross-

promotions, and other off-social marketing activities to reach and deepen your impact with audiences

new and old.

5 Types of Joint Campaigns

The heart of this approach to marketing is the classic idea of bartering. Your audience and your

content have value, and you can trade that value to another brand to advance your strategic goals.

That said, you must make these trades in a way that doesn’t compromise the integrity of your brand,

or the trust you worked so hard to build between your brand and your audience. When a trade is

done well, your audience should actually benefit.

From a high-level perspective, these trades usually involve one of the following:

Partnerships: You enter into an agreement (formal or informal) to jointly pursue an objective with

another brand for the long-term. Along the way, you share rewards like revenue or leads.

Collaboration: You join forces with another brand to work on a short-term project or campaign, and

share the rewards. The popular practice of co-branding falls under this category, though the true

scope can be deeper.

Cross-promotion: You and another brand agree to promote each other’s products and services to

your respective audiences.

5 | P a g e

Content placement: You and another brand agree to periodically share each other’s content with

your respective audiences.

Value-add: When making a deal with another brand or vendor, you use some level of access to your

audience as a negotiating tool.

All of these potential opportunities hinge upon respecting your audience. If one of these opportunities

doesn’t bring value to your audience or compromises the trust they placed in you by supporting your

brand, you’ll ultimately poison your own well. When successfully executed, however, your audience

will celebrate your willingness to innovate and collaborate on their behalf.

Examples of Successful Joint Campaigns

Some of the most successful brands in the world use this strategy to unlock new opportunities for their

businesses. To illustrate, Taco Bell partnered with Frito-Lay to produce the Doritos Locos Taco, which

sold 450 million units and led to the hiring of 15,000 more people less than a year after its

launch, according to Fast Company. Leading up to that success, though, were dozens of iterations

where both Taco Bell and Frito-Lay insisted on developing a product that didn’t compromise the

quality of their brands.

In other words, the Doritos taco still had to match the experience of eating Doritos. Simply slapping a

logo on the packaging would have sabotaged the goals of the partnership for both parties, so they

worked together to develop a stellar product experience that got both of their audiences excited.

Campari Group, one of the world’s leaders in spirits with brands like Wild Turkey and Skyy Vodka under

its umbrella, ran a campaign where the comic book character Deadpool took over managing the social

media accounts for the tequila Espolòn in the runup to the release of the film Deadpool 2. Deadpool

made posts, in character, to the Espolòn pages and was featured in a limited-edition DeadpoolEspolòn

box set.

Dave Karraker, vice president of communications at Campari Group and one of the architects behind

the campaign, told me that not only was the campaign designed to generate interest and engagement

for Espolòn’s social media, but the product tie-in gave Espolòn access to premium display placement at

stores across the United States. At the same time, the Deadpool brand managers were able to build

interest in the new film.

6 | P a g e

your respective audiences.

Value-add: When making a deal with another brand or vendor, you use some level of access to your

audience as a negotiating tool.

All of these potential opportunities hinge upon respecting your audience. If one of these opportunities

doesn’t bring value to your audience or compromises the trust they placed in you by supporting your

brand, you’ll ultimately poison your own well. When successfully executed, however, your audience

will celebrate your willingness to innovate and collaborate on their behalf.

Examples of Successful Joint Campaigns

Some of the most successful brands in the world use this strategy to unlock new opportunities for their

businesses. To illustrate, Taco Bell partnered with Frito-Lay to produce the Doritos Locos Taco, which

sold 450 million units and led to the hiring of 15,000 more people less than a year after its

launch, according to Fast Company. Leading up to that success, though, were dozens of iterations

where both Taco Bell and Frito-Lay insisted on developing a product that didn’t compromise the

quality of their brands.

In other words, the Doritos taco still had to match the experience of eating Doritos. Simply slapping a

logo on the packaging would have sabotaged the goals of the partnership for both parties, so they

worked together to develop a stellar product experience that got both of their audiences excited.

Campari Group, one of the world’s leaders in spirits with brands like Wild Turkey and Skyy Vodka under

its umbrella, ran a campaign where the comic book character Deadpool took over managing the social

media accounts for the tequila Espolòn in the runup to the release of the film Deadpool 2. Deadpool

made posts, in character, to the Espolòn pages and was featured in a limited-edition DeadpoolEspolòn

box set.

Dave Karraker, vice president of communications at Campari Group and one of the architects behind

the campaign, told me that not only was the campaign designed to generate interest and engagement

for Espolòn’s social media, but the product tie-in gave Espolòn access to premium display placement at

stores across the United States. At the same time, the Deadpool brand managers were able to build

interest in the new film.

6 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Both of these examples show how different brands can come together to serve their audiences in new,

beneficial ways. The relationships may be complex and take time to structure, but the joining of forces

and the recognition that they’re targeting similar audiences but aren’t competitors are powerful. And

their fans benefited just as much as the businesses, because these collaborations and partnerships

meant new products and additional entertainment.

Your brand, big or small, has access to similar opportunities.

When you look at the landscape of brand-to-brand collaborations, the work between international

businesses can make the scale of these marketing campaigns appear out of reach.

Yes, the Deadpool collaboration with Espolòn was the joining of two brand titans, but partnerships

don’t have to operate at this scale to be effective. Several small businesses are applying the same

principles in myriad ways.

The husband and wife team behind Inverted Gear, a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu brand, uses collaboration with

martial arts content creators and business owners to tap into new customer markets.

Their diverse strategy includes co-branded apparel products worn by instructors and event organizers,

such as a Greenland-themed kimono to celebrate their growing martial arts community. They co-

developed content and videos with those instructors as well.

Through Inverted Gear, the martial artists get access to new audiences while Inverted Gear uses the

relationships to deepen community ties.

Many of the Inverted Gear relationships with instructors and athletes begin with basic

sponsorships and grow into content sharing, product co-branding, and more involved

collaborations like documentaries.

Collaborations can also start out as classic social media marketing initiatives.

The PT Services Group, a B2B appointment-setting firm based in Pittsburgh, used thought leadership

content developed for industry publications to build new industry relationships. What started as a

guest blogging-style relationship grew into industry event invitations and offers for speaking gigs from

those publications, all of which were major wins for the PT sales pipeline.

7 | P a g e

beneficial ways. The relationships may be complex and take time to structure, but the joining of forces

and the recognition that they’re targeting similar audiences but aren’t competitors are powerful. And

their fans benefited just as much as the businesses, because these collaborations and partnerships

meant new products and additional entertainment.

Your brand, big or small, has access to similar opportunities.

When you look at the landscape of brand-to-brand collaborations, the work between international

businesses can make the scale of these marketing campaigns appear out of reach.

Yes, the Deadpool collaboration with Espolòn was the joining of two brand titans, but partnerships

don’t have to operate at this scale to be effective. Several small businesses are applying the same

principles in myriad ways.

The husband and wife team behind Inverted Gear, a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu brand, uses collaboration with

martial arts content creators and business owners to tap into new customer markets.

Their diverse strategy includes co-branded apparel products worn by instructors and event organizers,

such as a Greenland-themed kimono to celebrate their growing martial arts community. They co-

developed content and videos with those instructors as well.

Through Inverted Gear, the martial artists get access to new audiences while Inverted Gear uses the

relationships to deepen community ties.

Many of the Inverted Gear relationships with instructors and athletes begin with basic

sponsorships and grow into content sharing, product co-branding, and more involved

collaborations like documentaries.

Collaborations can also start out as classic social media marketing initiatives.

The PT Services Group, a B2B appointment-setting firm based in Pittsburgh, used thought leadership

content developed for industry publications to build new industry relationships. What started as a

guest blogging-style relationship grew into industry event invitations and offers for speaking gigs from

those publications, all of which were major wins for the PT sales pipeline.

7 | P a g e

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

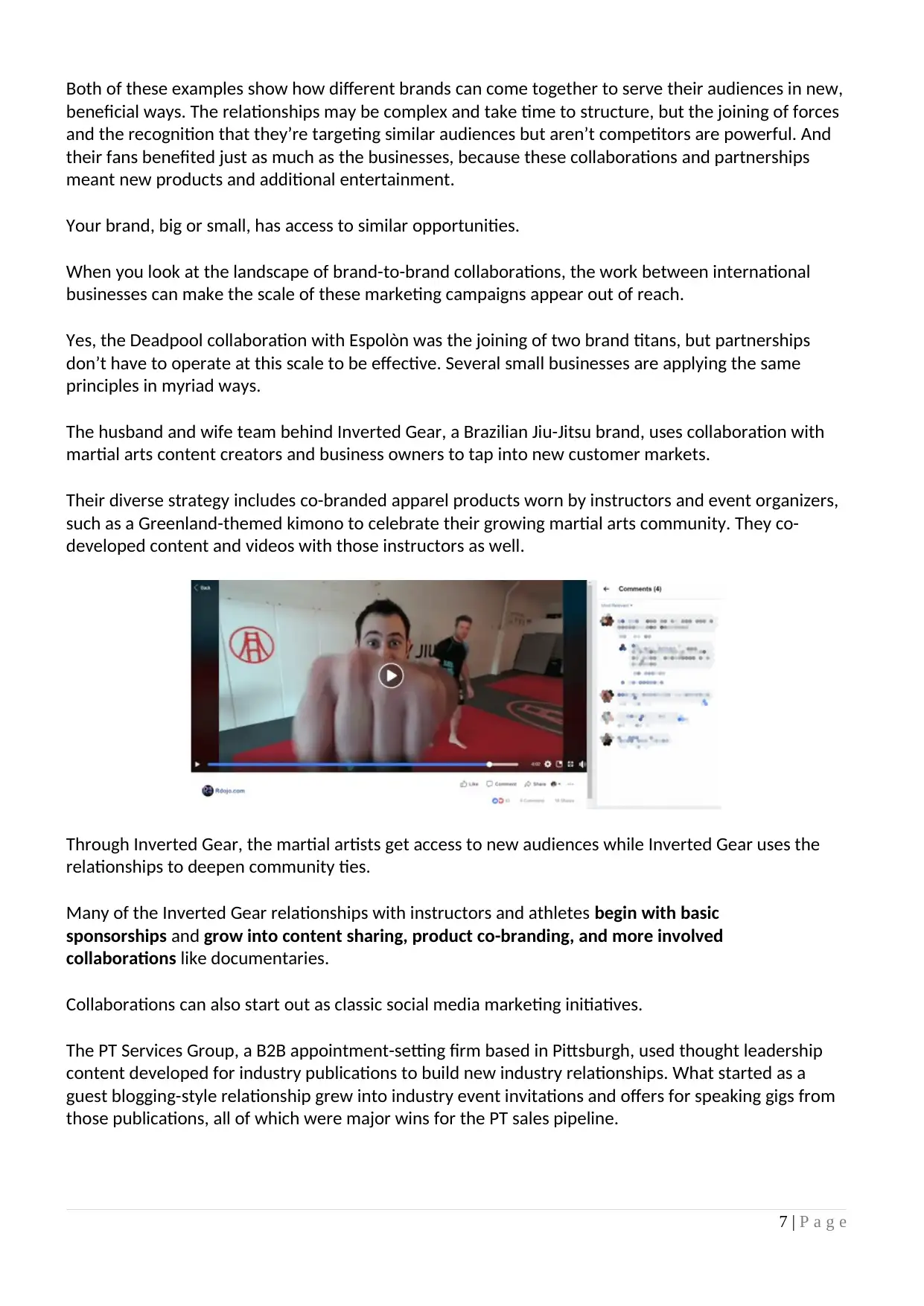

Part A - Identify opportunities for collaboration and develop collaborative alliances

Create a Partnership and alliance registry for 10 separate businesses that connect to your business

case study. In creating the registry make sure to:

1. Identify and evaluate opportunities for collaborative alliances according to organisational and

program objectives

2. Identify and evaluate potential collaborators according to organisational policies

3. Initiate and develop relationships with potential collaborators according to organisational

policies and procedures

Please follow the template:

Partnership Register

Numbe

r

Name Type of

Business

Product

s /

Services

Current

Marketing

Current

Advertisin

g

Benefits Negatives

1 Google Social

networkin

g sites

Social

Media

Marketing

strategies

Business Control

cost

efficiency

No

guarantees

2 Tweeter Reach a

target

audience

through ads

Online

Social

Media

Latest news

and other

advertisemen

t

News and

Knowledg

e

Immediacy Company

communicate

d not trusted

3 Faceboo

k

Network Online

Social

Media

Latest

Updates

Image

sharing

and

electronic

work

In Demand Takes time to

scale

4 Wikipedi

a

Research Online

Social

Media

Latest News

and research

work

Research

works

Scale

Control

Clutter

5 Instagra

m

Image

sharing

sites

Online

Social

Media

Current

affairs

Sales of

multiple

items

Key role in

most sales

Poor

credibility

6 YouTube Video

hosting

sites

Online

Social

Media

Latest Videos

and updates

Latest

Informativ

e videos

Transparen

t and lives

on

Declining

Response

rate

8 | P a g e

Create a Partnership and alliance registry for 10 separate businesses that connect to your business

case study. In creating the registry make sure to:

1. Identify and evaluate opportunities for collaborative alliances according to organisational and

program objectives

2. Identify and evaluate potential collaborators according to organisational policies

3. Initiate and develop relationships with potential collaborators according to organisational

policies and procedures

Please follow the template:

Partnership Register

Numbe

r

Name Type of

Business

Product

s /

Services

Current

Marketing

Current

Advertisin

g

Benefits Negatives

1 Google Social

networkin

g sites

Social

Media

Marketing

strategies

Business Control

cost

efficiency

No

guarantees

2 Tweeter Reach a

target

audience

through ads

Online

Social

Media

Latest news

and other

advertisemen

t

News and

Knowledg

e

Immediacy Company

communicate

d not trusted

3 Faceboo

k

Network Online

Social

Media

Latest

Updates

Image

sharing

and

electronic

work

In Demand Takes time to

scale

4 Wikipedi

a

Research Online

Social

Media

Latest News

and research

work

Research

works

Scale

Control

Clutter

5 Instagra

m

Image

sharing

sites

Online

Social

Media

Current

affairs

Sales of

multiple

items

Key role in

most sales

Poor

credibility

6 YouTube Video

hosting

sites

Online

Social

Media

Latest Videos

and updates

Latest

Informativ

e videos

Transparen

t and lives

on

Declining

Response

rate

8 | P a g e

7 Hosted

Websites

Communit

y blogs

Online

Social

sites

Latest web

links

Online

domain

users

In demand Hard to

measure

Part B - Establish collaborative agreements

Once you have completed the registry, select one business or company to focus on as the primary

candidate for your intended partnership or alliance.

Create a Collaborative Agreement and include the following details for your intended partnership or

alliance:

1. Collaborative approach with parties which adhere to organisational policies and relevant

legal requirements

Policies and procedures are an essential part of any organization. Together, policies and

procedures provide a roadmap for day-to-day operations. They ensure compliance with laws and

regulations, give guidance for decision-making, and streamline internal processes.

However, policies and procedures won’t do your organization any good if your employees don’t follow

them.

Employees don’t always like the idea of having to follow the rules. But policy implementation is not

just a matter of arbitrarily forcing employees to do things they don’t want to do.

Following policies and procedures is good for employees and your organization as a whole.

The importance of following policies and procedures

As your organization’s leaders create and enforce policies, it’s important to make sure your staff

understands why following policies and procedures is critical.

Here are just a few of the positive outcomes of following policies and procedures:

Consistent processes and structures

Policies and procedures keep operations from devolving into complete chaos.

When everyone is following policies and procedures, your organization can run smoothly.

Management structures and teams operate as they’re meant to. And mistakes and hiccups in

processes can be quickly identified and addressed.

When your staff is following policies and procedures, your organization will use time and resources

more efficiently. You’ll be able to grow and achieve your goals as an organization.

9 | P a g e

Websites

Communit

y blogs

Online

Social

sites

Latest web

links

Online

domain

users

In demand Hard to

measure

Part B - Establish collaborative agreements

Once you have completed the registry, select one business or company to focus on as the primary

candidate for your intended partnership or alliance.

Create a Collaborative Agreement and include the following details for your intended partnership or

alliance:

1. Collaborative approach with parties which adhere to organisational policies and relevant

legal requirements

Policies and procedures are an essential part of any organization. Together, policies and

procedures provide a roadmap for day-to-day operations. They ensure compliance with laws and

regulations, give guidance for decision-making, and streamline internal processes.

However, policies and procedures won’t do your organization any good if your employees don’t follow

them.

Employees don’t always like the idea of having to follow the rules. But policy implementation is not

just a matter of arbitrarily forcing employees to do things they don’t want to do.

Following policies and procedures is good for employees and your organization as a whole.

The importance of following policies and procedures

As your organization’s leaders create and enforce policies, it’s important to make sure your staff

understands why following policies and procedures is critical.

Here are just a few of the positive outcomes of following policies and procedures:

Consistent processes and structures

Policies and procedures keep operations from devolving into complete chaos.

When everyone is following policies and procedures, your organization can run smoothly.

Management structures and teams operate as they’re meant to. And mistakes and hiccups in

processes can be quickly identified and addressed.

When your staff is following policies and procedures, your organization will use time and resources

more efficiently. You’ll be able to grow and achieve your goals as an organization.

9 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

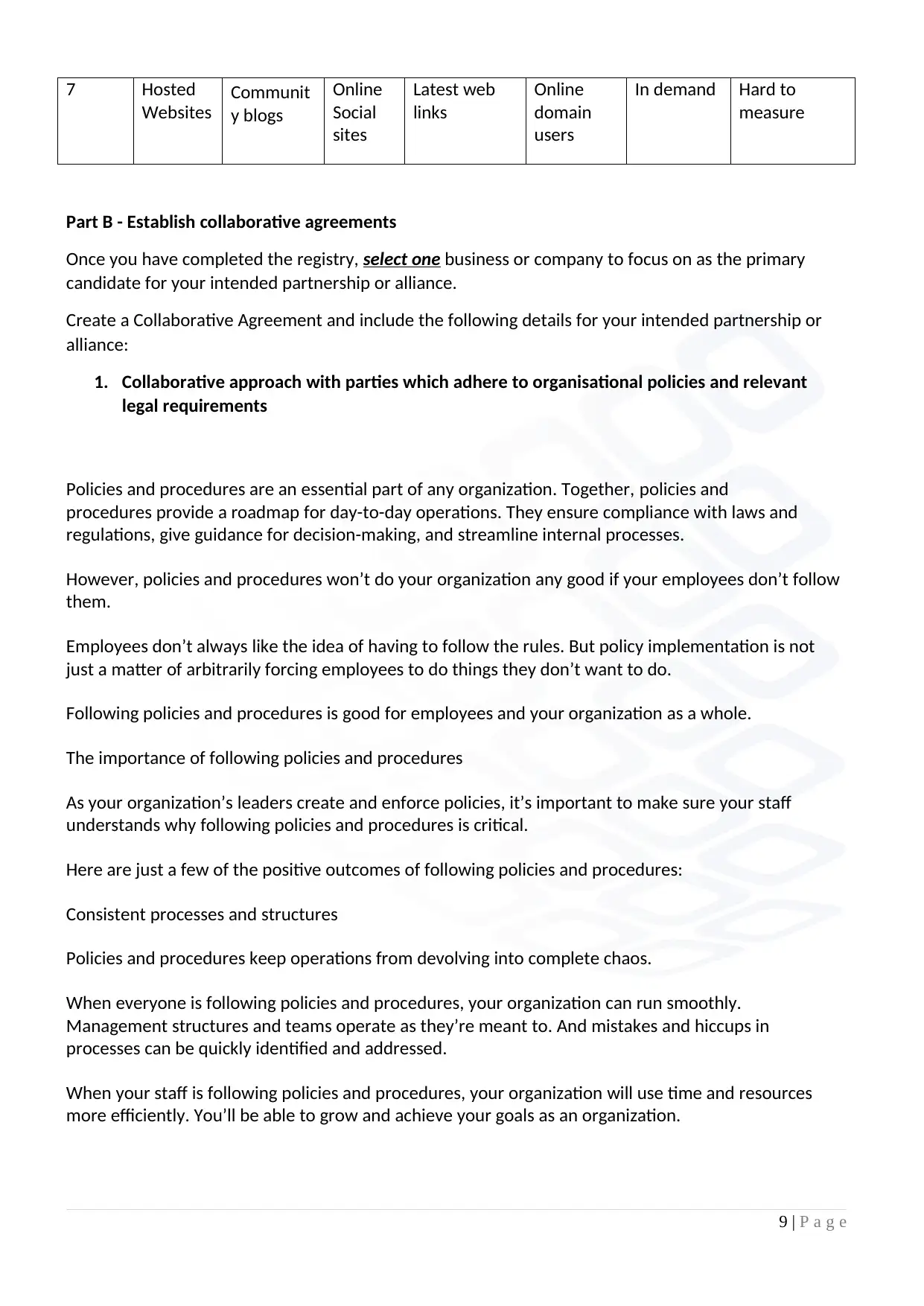

Consistency in practices is also right for employees individually. They know what they’re responsible

for, what’s expected of them, and what they can expect from their supervisors and co-workers. This

frees them up to do their jobs with confidence and excellence.

Better quality service

When employees follow procedures, they perform tasks correctly and provide consistent customer

service. This enhances the quality of your organization’s products and services. And, in turn, improves

your company’s reputation. Employees can know they are fulfilling their roles and take pride in their

work.

A safer workplace

When your staff is following policies and procedures, workplace accidents and incidents are less likely

to occur.

This reduces liability risks for your organization and limits interruptions in operations. Your employees

can feel safe and comfortable in the workplace, knowing that their managers and co-workers are

looking out for their best interest. They can rest assured that they’ll be taken care of if something does

happen.

2. Formal agreement to ensure continuation of envisaged value and to identify potential need

for changes and additions according to organisational policies and procedures

Organizations need to develop policies and procedures that reflect their vision, values and culture

as well as the needs of their employees. Once they are in place, enforcing these guidelines is even

more important. However, accomplishing these goals can be tougher than it sounds.

A policy is a set of general guidelines that outline the organization’s plan for tackling an issue. Policies

communicate the connection between the organization’s vision and values and its day-to-day

operations.

10 | P a g e

for, what’s expected of them, and what they can expect from their supervisors and co-workers. This

frees them up to do their jobs with confidence and excellence.

Better quality service

When employees follow procedures, they perform tasks correctly and provide consistent customer

service. This enhances the quality of your organization’s products and services. And, in turn, improves

your company’s reputation. Employees can know they are fulfilling their roles and take pride in their

work.

A safer workplace

When your staff is following policies and procedures, workplace accidents and incidents are less likely

to occur.

This reduces liability risks for your organization and limits interruptions in operations. Your employees

can feel safe and comfortable in the workplace, knowing that their managers and co-workers are

looking out for their best interest. They can rest assured that they’ll be taken care of if something does

happen.

2. Formal agreement to ensure continuation of envisaged value and to identify potential need

for changes and additions according to organisational policies and procedures

Organizations need to develop policies and procedures that reflect their vision, values and culture

as well as the needs of their employees. Once they are in place, enforcing these guidelines is even

more important. However, accomplishing these goals can be tougher than it sounds.

A policy is a set of general guidelines that outline the organization’s plan for tackling an issue. Policies

communicate the connection between the organization’s vision and values and its day-to-day

operations.

10 | P a g e

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

A procedure explains a specific action plan for carrying out a policy. Procedures tells employees how to

deal with a situation and when.

Using policies and procedures together gives employees a well-rounded view of their workplace. They

know the type of culture that the organization is striving for, what behavioris expected of them and

how to achieve both of these.

The Importance of Policies and Procedures

Regardless of your organization’s size, developing formal policies and procedures can make it run

much more smoothly and efficiently. They communicate the values and vision of the organization,

ensuring employees understand exactly what is expected of them in certain situations.

Because both individual and team responsibilities are clearly documented, there is no need for trial-

and-error or micromanaging. Upon reading the workplace policies and procedures, employees should

clearly understand how to approach their jobs.

Formal policies and procedures save time and stress when handling HR issues. The absence of written

policies results in unnecessary time and effort spent trying to agree on a course of action. With strict

guidelines already in place, employees simply have to follow the procedures and managers just have to

enforce the policies.

Implementing these documents also improves the way an organization looks from the outside. Formal

policies and procedures help to ensure your company complies with relevant regulations. They also

demonstrate that organizations are efficient, professional and stable. This can lead to stronger

business relationships and a better public reputation.

How to Develop Policies and Procedures in the Workplace

When creating a policy or procedure for your workplace, start by reviewing the mission statement,

vision and values. According to the New South Wales Government Industrial Relations, “a workplace

policy should:

set out the aim of the policy

explain why the policy was developed

11 | P a g e

deal with a situation and when.

Using policies and procedures together gives employees a well-rounded view of their workplace. They

know the type of culture that the organization is striving for, what behavioris expected of them and

how to achieve both of these.

The Importance of Policies and Procedures

Regardless of your organization’s size, developing formal policies and procedures can make it run

much more smoothly and efficiently. They communicate the values and vision of the organization,

ensuring employees understand exactly what is expected of them in certain situations.

Because both individual and team responsibilities are clearly documented, there is no need for trial-

and-error or micromanaging. Upon reading the workplace policies and procedures, employees should

clearly understand how to approach their jobs.

Formal policies and procedures save time and stress when handling HR issues. The absence of written

policies results in unnecessary time and effort spent trying to agree on a course of action. With strict

guidelines already in place, employees simply have to follow the procedures and managers just have to

enforce the policies.

Implementing these documents also improves the way an organization looks from the outside. Formal

policies and procedures help to ensure your company complies with relevant regulations. They also

demonstrate that organizations are efficient, professional and stable. This can lead to stronger

business relationships and a better public reputation.

How to Develop Policies and Procedures in the Workplace

When creating a policy or procedure for your workplace, start by reviewing the mission statement,

vision and values. According to the New South Wales Government Industrial Relations, “a workplace

policy should:

set out the aim of the policy

explain why the policy was developed

11 | P a g e

list who the policy applies to

set out what is acceptable or unacceptable behavior

set out the consequences of not complying with the policy

provide a date when the policy was developed or updated”

Once you implement your policies and procedures, the next step is to inform and train employees on

them. You can’t expect employees to follow guidelines if they aren’t aware of them. Be sure to

schedule regular refresher training sessions, too, to keep employees on track.

Paychex WORX says that “employees may be more likely to embrace rules when they understand their

purpose and that they are not meant to be a form of control or punishment.” For this reason, keep a

positive attitude during training sessions and leave plenty of time for employee questions.

Policies and procedures should not be written once and left alone for decades. Reviewing these

documents regularly and updating them when necessary is key to their success. In addition to an

annual review, consider updating them when you:

adopt new equipment, software, etc.

see an increase in accidents or failures on-site

experience increased customer complaints

have a feeling of general confusion or increased staff questions regarding day-to-day operations

see inconsistency in employee job performance

feel increased stress levels across the office

3. Collaboration plans for each agreement to support implementation

The Collaboration Planning Approach refers to the process of considering the specific conditions

associated with a set of key influences for a given research team, center, or initiative. A primary step in

the Collaboration Planning Approach involves documenting the key influences and agreed upon

actions to address each influencing factor. This process results in a written Collaboration Plan that is

tailored to a given team science effort.

Ten key influences on team science were identified to guide the Collaboration Planning process. These

ten influences range from the initial scientific rationale for a team approach to the collaboration

readiness of participating individuals and institutions to team communication and coordination

mechanisms to approaches to quality improvement for team functioning (Fig. 45.1). The Collaboration

Planning framework serves to guide collaborators through dialogue and planning around each

influence and draws their attention to key issues for consideration related to each influence. Decisions

are captured in the written Collaboration Plan.

12 | P a g e

set out what is acceptable or unacceptable behavior

set out the consequences of not complying with the policy

provide a date when the policy was developed or updated”

Once you implement your policies and procedures, the next step is to inform and train employees on

them. You can’t expect employees to follow guidelines if they aren’t aware of them. Be sure to

schedule regular refresher training sessions, too, to keep employees on track.

Paychex WORX says that “employees may be more likely to embrace rules when they understand their

purpose and that they are not meant to be a form of control or punishment.” For this reason, keep a

positive attitude during training sessions and leave plenty of time for employee questions.

Policies and procedures should not be written once and left alone for decades. Reviewing these

documents regularly and updating them when necessary is key to their success. In addition to an

annual review, consider updating them when you:

adopt new equipment, software, etc.

see an increase in accidents or failures on-site

experience increased customer complaints

have a feeling of general confusion or increased staff questions regarding day-to-day operations

see inconsistency in employee job performance

feel increased stress levels across the office

3. Collaboration plans for each agreement to support implementation

The Collaboration Planning Approach refers to the process of considering the specific conditions

associated with a set of key influences for a given research team, center, or initiative. A primary step in

the Collaboration Planning Approach involves documenting the key influences and agreed upon

actions to address each influencing factor. This process results in a written Collaboration Plan that is

tailored to a given team science effort.

Ten key influences on team science were identified to guide the Collaboration Planning process. These

ten influences range from the initial scientific rationale for a team approach to the collaboration

readiness of participating individuals and institutions to team communication and coordination

mechanisms to approaches to quality improvement for team functioning (Fig. 45.1). The Collaboration

Planning framework serves to guide collaborators through dialogue and planning around each

influence and draws their attention to key issues for consideration related to each influence. Decisions

are captured in the written Collaboration Plan.

12 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 49

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.