SMILE EXPERIMENT: SNHU SCS 502 Module Eight Research Project

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/15

|10

|1902

|425

Project

AI Summary

This assignment details a psychology project involving a smile experiment conducted by a student. The study investigates the impact of smiling on social interactions in different environments, specifically a shopping mall and a playground. The student developed a hypothesis, designed a naturalistic observation study, and collected data by smiling at consumers in these locations, recording their reactions. The results, although not entirely supporting the initial prediction, provided insights into facial expressions as social cues. The paper includes an introduction with a literature review, methodology, results, and discussion, along with references to relevant research. The experiment aimed to understand how context influences the interpretation of a smile, contributing to the broader understanding of nonverbal communication and social behavior. The student adhered to ethical guidelines by avoiding direct interaction with participants, focusing solely on observation.

Running head: SMILE EXPERIMENT

SMILE EXPERIMENT

Name of Student

Name of University

Author’s Note

SMILE EXPERIMENT

Name of Student

Name of University

Author’s Note

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1SMILE EXPERIMENT

Abstract

In human beings, the sensory corridors are the origin of a Smile. The event of smiling is a very

short event and does not last for more than 3-4 seconds, but the impact of smiling can be very

generous. Emotions perform an extensive role in our day-to-day lives. Smiling is an emotion,

which can have both positive and negative effects on others. The main objective of this study is

to conduct an experiment based on the hypothesis, that smiling has both positive and negative

meanings depending on the situation. The experiment was conducted in an outdoor children’s

playground and a shopping mall, to see how the social convention dictates on smiling. The

prediction was that the consumers in the playground will show negative engagement and the

consumers in the shopping mall will show positive engagement. However, the results were quite

opposite, but it was significant enough to support the experimental hypothesis, the study also

embraces the aim of the facial expressions and friendly clues.

Abstract

In human beings, the sensory corridors are the origin of a Smile. The event of smiling is a very

short event and does not last for more than 3-4 seconds, but the impact of smiling can be very

generous. Emotions perform an extensive role in our day-to-day lives. Smiling is an emotion,

which can have both positive and negative effects on others. The main objective of this study is

to conduct an experiment based on the hypothesis, that smiling has both positive and negative

meanings depending on the situation. The experiment was conducted in an outdoor children’s

playground and a shopping mall, to see how the social convention dictates on smiling. The

prediction was that the consumers in the playground will show negative engagement and the

consumers in the shopping mall will show positive engagement. However, the results were quite

opposite, but it was significant enough to support the experimental hypothesis, the study also

embraces the aim of the facial expressions and friendly clues.

2SMILE EXPERIMENT

Introduction

Facial displays vary vastly across different social conventions, when the social act is

served by a Smile. Humans interact with other creatures by using facial expressions like Smile.

According to Lipps’ philosophy, humans are those minded creatures who have the need for

“inner imitation” (Haendiges, 2014). Some mirror neurons, which acts as a mechanism to help

human understand other’s emotions because of their facial expression are found by the

neuroscientists after getting inspired by the Lipps’ philosophy (Stanley, 2015).

The main objective of this study to understand the impact of sender’s smile to receiver

and to understand what the smile is interpreted by the receiver (Takahashi, Oishi & Shimada,

2017). The research hypothesis was if I smile at 10 consumers while exercising in the

playground and while exploring the shopping mall, the consumers in the playground will

interpret my smile in a negative way and the consumers in the mall will interpret in a positive

way (Arminjon et al., 2015). The primary agenda of the hypothesis was not to talk to any of the

consumer; I just have to make a direct eye contact and smile, and then record their reaction. The

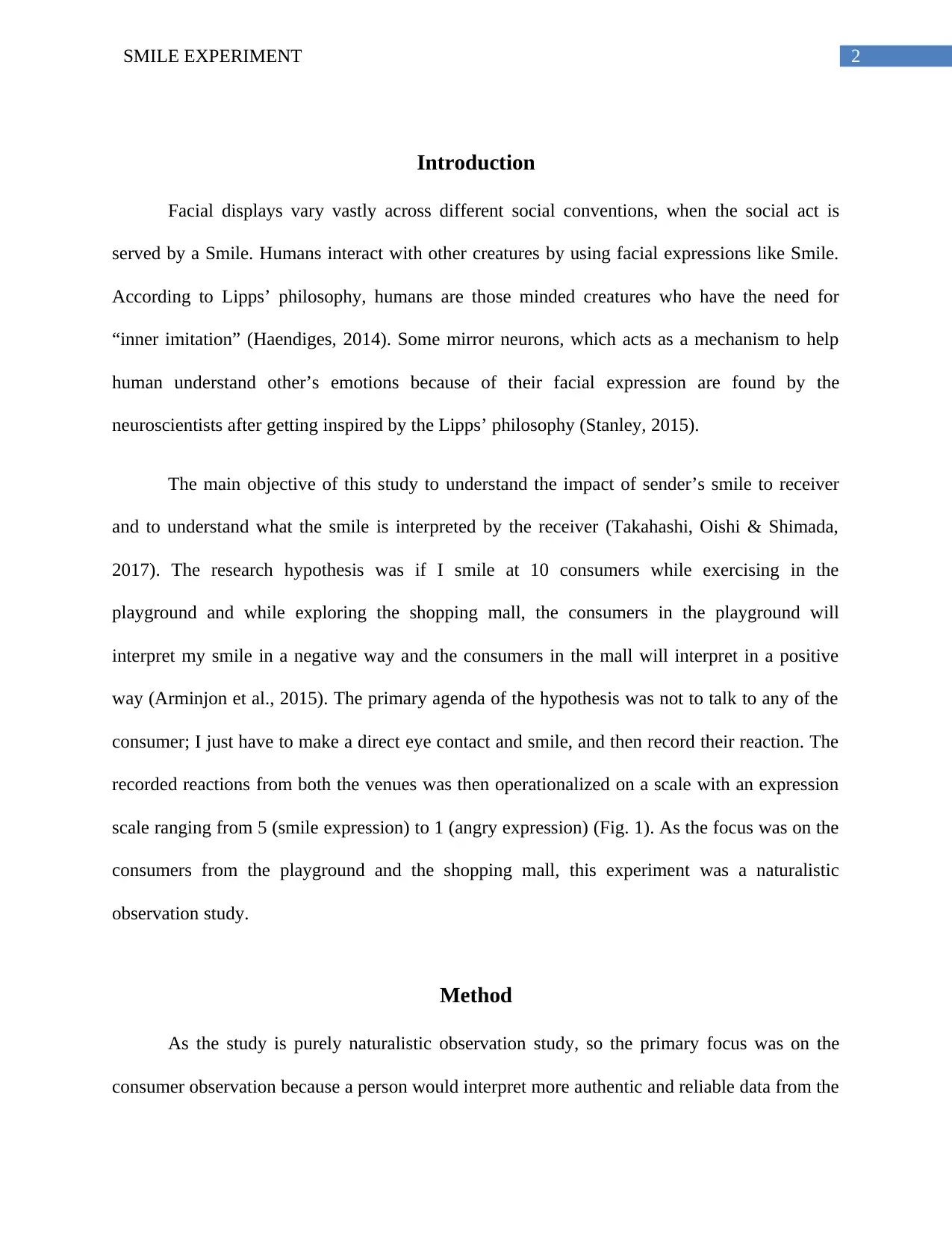

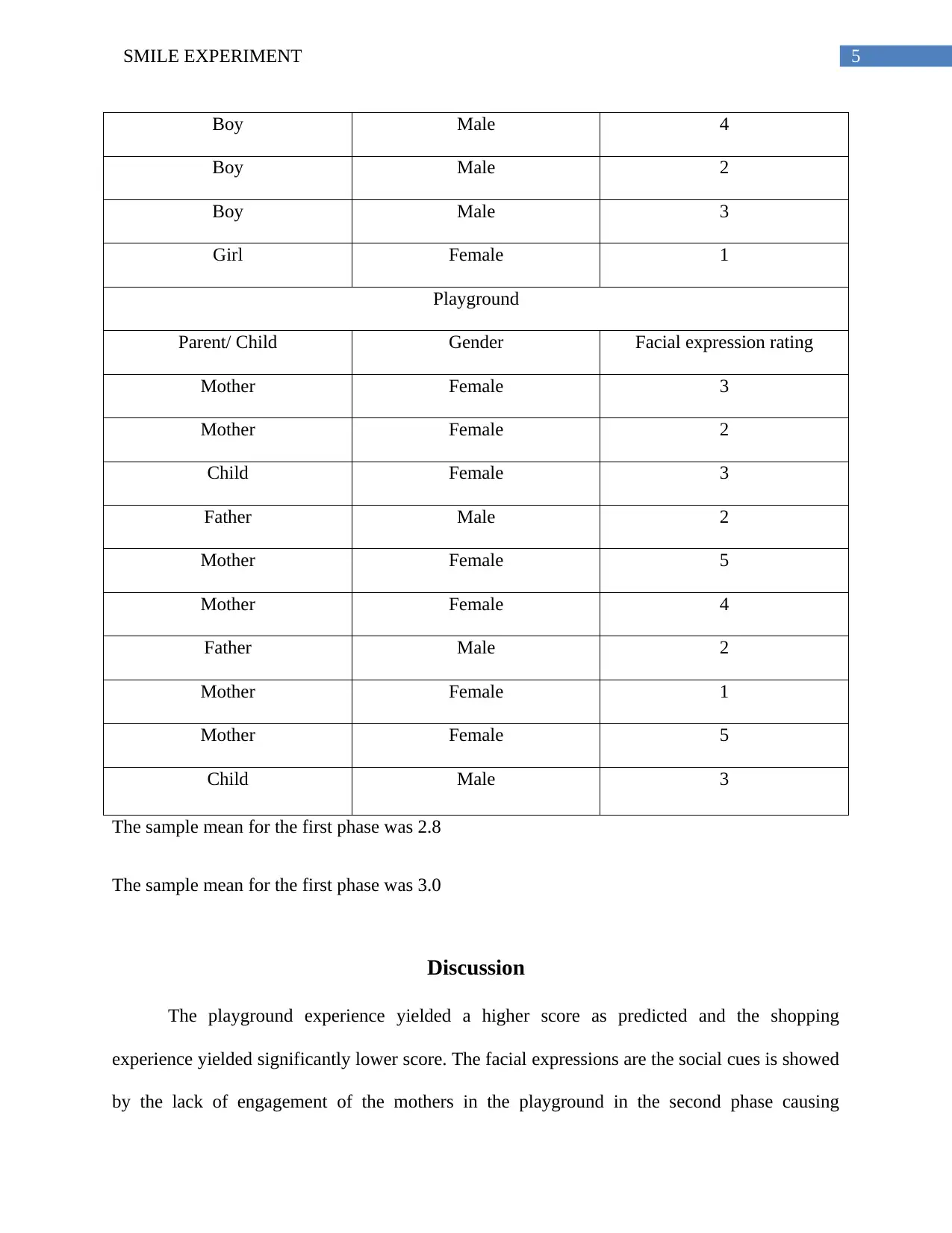

recorded reactions from both the venues was then operationalized on a scale with an expression

scale ranging from 5 (smile expression) to 1 (angry expression) (Fig. 1). As the focus was on the

consumers from the playground and the shopping mall, this experiment was a naturalistic

observation study.

Method

As the study is purely naturalistic observation study, so the primary focus was on the

consumer observation because a person would interpret more authentic and reliable data from the

Introduction

Facial displays vary vastly across different social conventions, when the social act is

served by a Smile. Humans interact with other creatures by using facial expressions like Smile.

According to Lipps’ philosophy, humans are those minded creatures who have the need for

“inner imitation” (Haendiges, 2014). Some mirror neurons, which acts as a mechanism to help

human understand other’s emotions because of their facial expression are found by the

neuroscientists after getting inspired by the Lipps’ philosophy (Stanley, 2015).

The main objective of this study to understand the impact of sender’s smile to receiver

and to understand what the smile is interpreted by the receiver (Takahashi, Oishi & Shimada,

2017). The research hypothesis was if I smile at 10 consumers while exercising in the

playground and while exploring the shopping mall, the consumers in the playground will

interpret my smile in a negative way and the consumers in the mall will interpret in a positive

way (Arminjon et al., 2015). The primary agenda of the hypothesis was not to talk to any of the

consumer; I just have to make a direct eye contact and smile, and then record their reaction. The

recorded reactions from both the venues was then operationalized on a scale with an expression

scale ranging from 5 (smile expression) to 1 (angry expression) (Fig. 1). As the focus was on the

consumers from the playground and the shopping mall, this experiment was a naturalistic

observation study.

Method

As the study is purely naturalistic observation study, so the primary focus was on the

consumer observation because a person would interpret more authentic and reliable data from the

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3SMILE EXPERIMENT

facial expressions as the friendly clues (Kawamoto, Nittono & Ura, 2014). In order to confirm

the hypothesis, the study was conducted on a holiday, last Thursday (4th July), which in U.S is

Independence Day. The reason behind the execution of the study on this particular day was that

the shopping malls and the playgrounds would be extra busy and crowded (Kret & De Gelder,

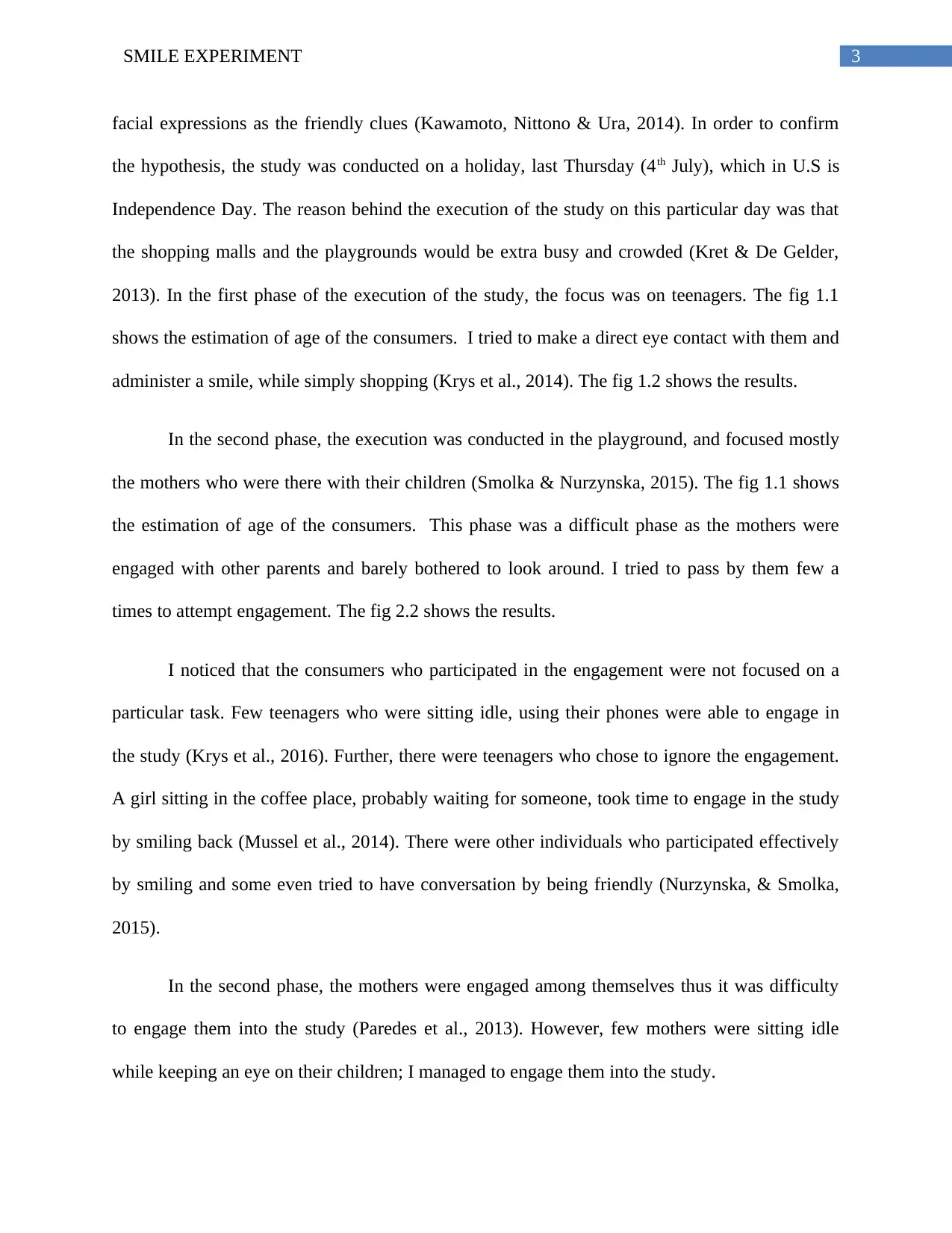

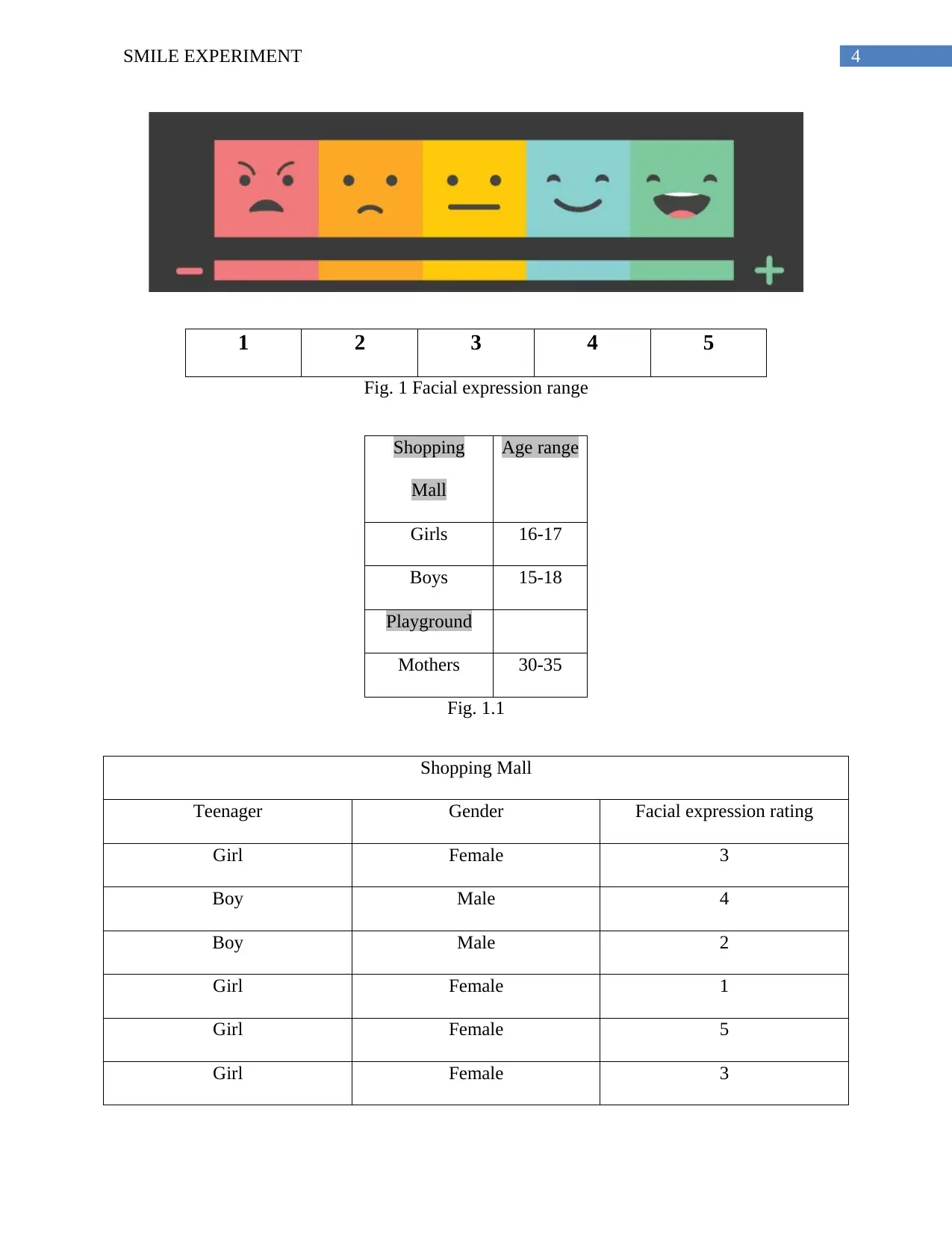

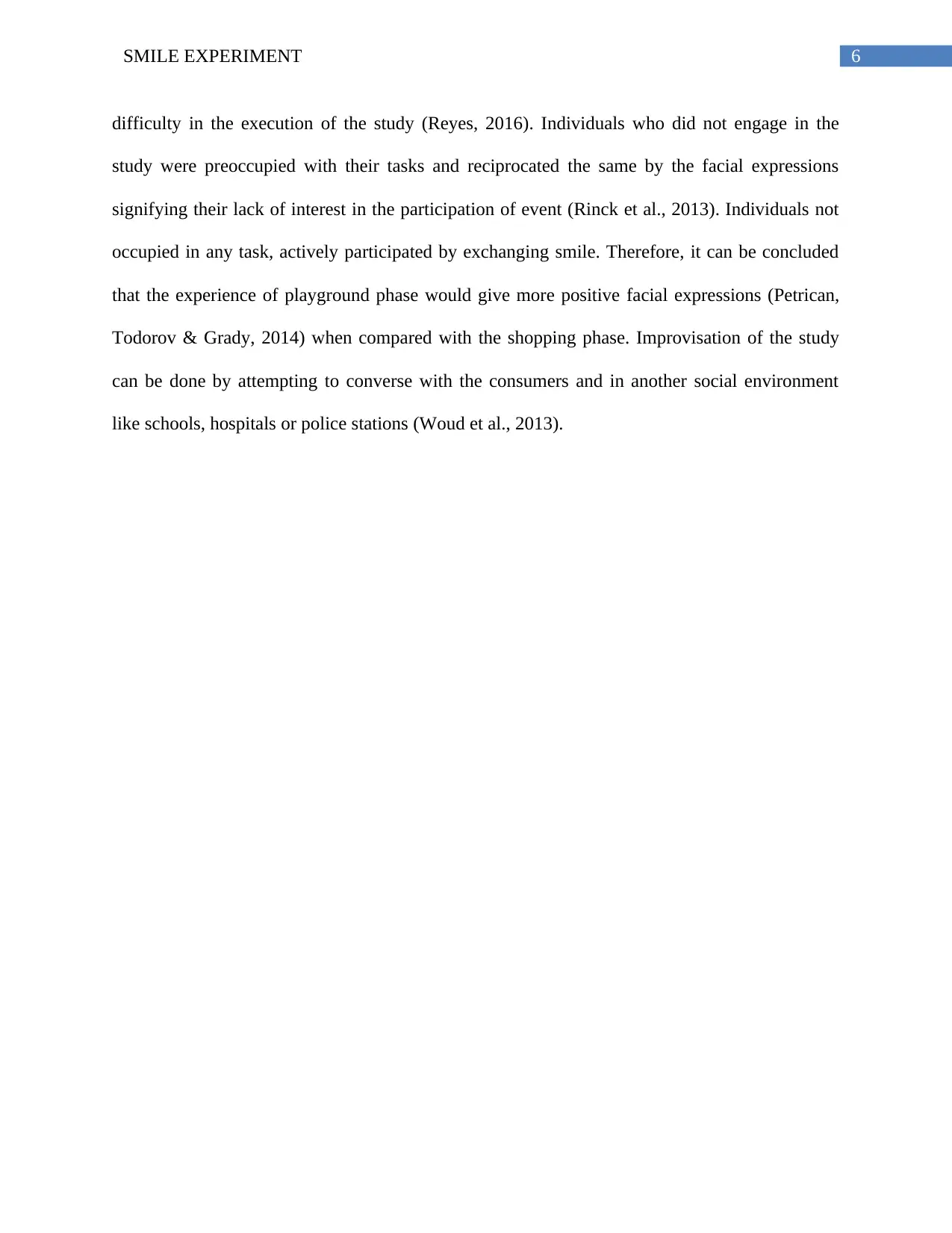

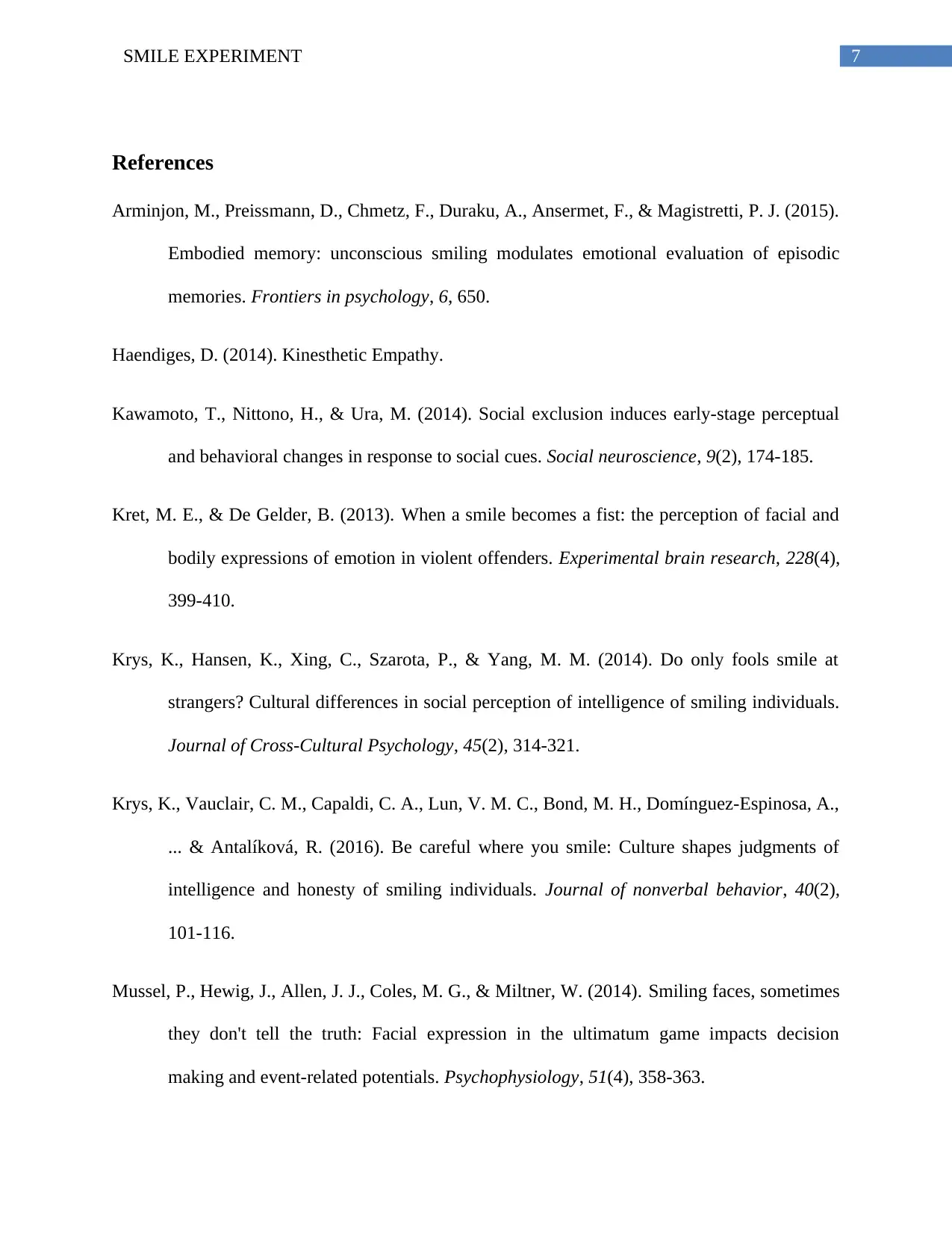

2013). In the first phase of the execution of the study, the focus was on teenagers. The fig 1.1

shows the estimation of age of the consumers. I tried to make a direct eye contact with them and

administer a smile, while simply shopping (Krys et al., 2014). The fig 1.2 shows the results.

In the second phase, the execution was conducted in the playground, and focused mostly

the mothers who were there with their children (Smolka & Nurzynska, 2015). The fig 1.1 shows

the estimation of age of the consumers. This phase was a difficult phase as the mothers were

engaged with other parents and barely bothered to look around. I tried to pass by them few a

times to attempt engagement. The fig 2.2 shows the results.

I noticed that the consumers who participated in the engagement were not focused on a

particular task. Few teenagers who were sitting idle, using their phones were able to engage in

the study (Krys et al., 2016). Further, there were teenagers who chose to ignore the engagement.

A girl sitting in the coffee place, probably waiting for someone, took time to engage in the study

by smiling back (Mussel et al., 2014). There were other individuals who participated effectively

by smiling and some even tried to have conversation by being friendly (Nurzynska, & Smolka,

2015).

In the second phase, the mothers were engaged among themselves thus it was difficulty

to engage them into the study (Paredes et al., 2013). However, few mothers were sitting idle

while keeping an eye on their children; I managed to engage them into the study.

facial expressions as the friendly clues (Kawamoto, Nittono & Ura, 2014). In order to confirm

the hypothesis, the study was conducted on a holiday, last Thursday (4th July), which in U.S is

Independence Day. The reason behind the execution of the study on this particular day was that

the shopping malls and the playgrounds would be extra busy and crowded (Kret & De Gelder,

2013). In the first phase of the execution of the study, the focus was on teenagers. The fig 1.1

shows the estimation of age of the consumers. I tried to make a direct eye contact with them and

administer a smile, while simply shopping (Krys et al., 2014). The fig 1.2 shows the results.

In the second phase, the execution was conducted in the playground, and focused mostly

the mothers who were there with their children (Smolka & Nurzynska, 2015). The fig 1.1 shows

the estimation of age of the consumers. This phase was a difficult phase as the mothers were

engaged with other parents and barely bothered to look around. I tried to pass by them few a

times to attempt engagement. The fig 2.2 shows the results.

I noticed that the consumers who participated in the engagement were not focused on a

particular task. Few teenagers who were sitting idle, using their phones were able to engage in

the study (Krys et al., 2016). Further, there were teenagers who chose to ignore the engagement.

A girl sitting in the coffee place, probably waiting for someone, took time to engage in the study

by smiling back (Mussel et al., 2014). There were other individuals who participated effectively

by smiling and some even tried to have conversation by being friendly (Nurzynska, & Smolka,

2015).

In the second phase, the mothers were engaged among themselves thus it was difficulty

to engage them into the study (Paredes et al., 2013). However, few mothers were sitting idle

while keeping an eye on their children; I managed to engage them into the study.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4SMILE EXPERIMENT

1 2 3 4 5

Fig. 1 Facial expression range

Shopping

Mall

Age range

Girls 16-17

Boys 15-18

Playground

Mothers 30-35

Fig. 1.1

Shopping Mall

Teenager Gender Facial expression rating

Girl Female 3

Boy Male 4

Boy Male 2

Girl Female 1

Girl Female 5

Girl Female 3

1 2 3 4 5

Fig. 1 Facial expression range

Shopping

Mall

Age range

Girls 16-17

Boys 15-18

Playground

Mothers 30-35

Fig. 1.1

Shopping Mall

Teenager Gender Facial expression rating

Girl Female 3

Boy Male 4

Boy Male 2

Girl Female 1

Girl Female 5

Girl Female 3

5SMILE EXPERIMENT

Boy Male 4

Boy Male 2

Boy Male 3

Girl Female 1

Playground

Parent/ Child Gender Facial expression rating

Mother Female 3

Mother Female 2

Child Female 3

Father Male 2

Mother Female 5

Mother Female 4

Father Male 2

Mother Female 1

Mother Female 5

Child Male 3

The sample mean for the first phase was 2.8

The sample mean for the first phase was 3.0

Discussion

The playground experience yielded a higher score as predicted and the shopping

experience yielded significantly lower score. The facial expressions are the social cues is showed

by the lack of engagement of the mothers in the playground in the second phase causing

Boy Male 4

Boy Male 2

Boy Male 3

Girl Female 1

Playground

Parent/ Child Gender Facial expression rating

Mother Female 3

Mother Female 2

Child Female 3

Father Male 2

Mother Female 5

Mother Female 4

Father Male 2

Mother Female 1

Mother Female 5

Child Male 3

The sample mean for the first phase was 2.8

The sample mean for the first phase was 3.0

Discussion

The playground experience yielded a higher score as predicted and the shopping

experience yielded significantly lower score. The facial expressions are the social cues is showed

by the lack of engagement of the mothers in the playground in the second phase causing

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6SMILE EXPERIMENT

difficulty in the execution of the study (Reyes, 2016). Individuals who did not engage in the

study were preoccupied with their tasks and reciprocated the same by the facial expressions

signifying their lack of interest in the participation of event (Rinck et al., 2013). Individuals not

occupied in any task, actively participated by exchanging smile. Therefore, it can be concluded

that the experience of playground phase would give more positive facial expressions (Petrican,

Todorov & Grady, 2014) when compared with the shopping phase. Improvisation of the study

can be done by attempting to converse with the consumers and in another social environment

like schools, hospitals or police stations (Woud et al., 2013).

difficulty in the execution of the study (Reyes, 2016). Individuals who did not engage in the

study were preoccupied with their tasks and reciprocated the same by the facial expressions

signifying their lack of interest in the participation of event (Rinck et al., 2013). Individuals not

occupied in any task, actively participated by exchanging smile. Therefore, it can be concluded

that the experience of playground phase would give more positive facial expressions (Petrican,

Todorov & Grady, 2014) when compared with the shopping phase. Improvisation of the study

can be done by attempting to converse with the consumers and in another social environment

like schools, hospitals or police stations (Woud et al., 2013).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7SMILE EXPERIMENT

References

Arminjon, M., Preissmann, D., Chmetz, F., Duraku, A., Ansermet, F., & Magistretti, P. J. (2015).

Embodied memory: unconscious smiling modulates emotional evaluation of episodic

memories. Frontiers in psychology, 6, 650.

Haendiges, D. (2014). Kinesthetic Empathy.

Kawamoto, T., Nittono, H., & Ura, M. (2014). Social exclusion induces early-stage perceptual

and behavioral changes in response to social cues. Social neuroscience, 9(2), 174-185.

Kret, M. E., & De Gelder, B. (2013). When a smile becomes a fist: the perception of facial and

bodily expressions of emotion in violent offenders. Experimental brain research, 228(4),

399-410.

Krys, K., Hansen, K., Xing, C., Szarota, P., & Yang, M. M. (2014). Do only fools smile at

strangers? Cultural differences in social perception of intelligence of smiling individuals.

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(2), 314-321.

Krys, K., Vauclair, C. M., Capaldi, C. A., Lun, V. M. C., Bond, M. H., Domínguez-Espinosa, A.,

... & Antalíková, R. (2016). Be careful where you smile: Culture shapes judgments of

intelligence and honesty of smiling individuals. Journal of nonverbal behavior, 40(2),

101-116.

Mussel, P., Hewig, J., Allen, J. J., Coles, M. G., & Miltner, W. (2014). Smiling faces, sometimes

they don't tell the truth: Facial expression in the ultimatum game impacts decision

making and event‐related potentials. Psychophysiology, 51(4), 358-363.

References

Arminjon, M., Preissmann, D., Chmetz, F., Duraku, A., Ansermet, F., & Magistretti, P. J. (2015).

Embodied memory: unconscious smiling modulates emotional evaluation of episodic

memories. Frontiers in psychology, 6, 650.

Haendiges, D. (2014). Kinesthetic Empathy.

Kawamoto, T., Nittono, H., & Ura, M. (2014). Social exclusion induces early-stage perceptual

and behavioral changes in response to social cues. Social neuroscience, 9(2), 174-185.

Kret, M. E., & De Gelder, B. (2013). When a smile becomes a fist: the perception of facial and

bodily expressions of emotion in violent offenders. Experimental brain research, 228(4),

399-410.

Krys, K., Hansen, K., Xing, C., Szarota, P., & Yang, M. M. (2014). Do only fools smile at

strangers? Cultural differences in social perception of intelligence of smiling individuals.

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(2), 314-321.

Krys, K., Vauclair, C. M., Capaldi, C. A., Lun, V. M. C., Bond, M. H., Domínguez-Espinosa, A.,

... & Antalíková, R. (2016). Be careful where you smile: Culture shapes judgments of

intelligence and honesty of smiling individuals. Journal of nonverbal behavior, 40(2),

101-116.

Mussel, P., Hewig, J., Allen, J. J., Coles, M. G., & Miltner, W. (2014). Smiling faces, sometimes

they don't tell the truth: Facial expression in the ultimatum game impacts decision

making and event‐related potentials. Psychophysiology, 51(4), 358-363.

8SMILE EXPERIMENT

Nurzynska, K., & Smolka, B. (2015, May). PCA application in classification of smiling and

neutral facial displays. In International Conference: Beyond Databases, Architectures

and Structures (pp. 398-407). Springer, Cham.

Paredes, B., Stavraki, M., Briñol, P., & Petty, R. E. (2013). Smiling after thinking increases

reliance on thoughts. Social Psychology.

Petrican, R., Todorov, A., & Grady, C. (2014). Personality at face value: Facial appearance

predicts self and other personality judgments among strangers and spouses. Journal of

nonverbal behavior, 38(2), 259-277.

Reyes, R. C. (2016). Meaningless vs. Worthwhile Encounters?: Sustaining Social Interactions in

Privatized Public Spaces of Manila Shopping Malls. Sains Humanika, 8(4-3).

Rinck, M., Telli, S., Kampmann, I., Woud, M. L., Kerstholt, M., te Velthuis, S., ... & Becker, E.

S. (2013). Training approach-avoidance of smiling faces affects emotional vulnerability

in socially anxious individuals. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 481.

Smolka, B., & Nurzynska, K. (2015). Power LBP: A novel texture operator for smiling and

neutral facial display classification. Procedia Computer Science, 51, 1555-1564.

Stanley, P. (2015). Talking to strangers. Language learning beyond the classroom, 244.

Takahashi, K., Oishi, T., & Shimada, M. (2017). Is☺ smiling? Cross-cultural study on

recognition of emoticon’s emotion. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(10), 1578-

1586.

Nurzynska, K., & Smolka, B. (2015, May). PCA application in classification of smiling and

neutral facial displays. In International Conference: Beyond Databases, Architectures

and Structures (pp. 398-407). Springer, Cham.

Paredes, B., Stavraki, M., Briñol, P., & Petty, R. E. (2013). Smiling after thinking increases

reliance on thoughts. Social Psychology.

Petrican, R., Todorov, A., & Grady, C. (2014). Personality at face value: Facial appearance

predicts self and other personality judgments among strangers and spouses. Journal of

nonverbal behavior, 38(2), 259-277.

Reyes, R. C. (2016). Meaningless vs. Worthwhile Encounters?: Sustaining Social Interactions in

Privatized Public Spaces of Manila Shopping Malls. Sains Humanika, 8(4-3).

Rinck, M., Telli, S., Kampmann, I., Woud, M. L., Kerstholt, M., te Velthuis, S., ... & Becker, E.

S. (2013). Training approach-avoidance of smiling faces affects emotional vulnerability

in socially anxious individuals. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 481.

Smolka, B., & Nurzynska, K. (2015). Power LBP: A novel texture operator for smiling and

neutral facial display classification. Procedia Computer Science, 51, 1555-1564.

Stanley, P. (2015). Talking to strangers. Language learning beyond the classroom, 244.

Takahashi, K., Oishi, T., & Shimada, M. (2017). Is☺ smiling? Cross-cultural study on

recognition of emoticon’s emotion. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(10), 1578-

1586.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9SMILE EXPERIMENT

Woud, M. L., Becker, E. S., Lange, W. G., & Rinck, M. (2013). Effects of approach-avoidance

training on implicit and explicit evaluations of neutral, angry, and smiling face stimuli.

Psychological Reports, 113(1), 199-216.

Woud, M. L., Becker, E. S., Lange, W. G., & Rinck, M. (2013). Effects of approach-avoidance

training on implicit and explicit evaluations of neutral, angry, and smiling face stimuli.

Psychological Reports, 113(1), 199-216.

1 out of 10

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.