Discrimination in Social Psychology: Theories, Measurement, and Impact

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/10

|29

|10948

|361

Report

AI Summary

This report delves into the social psychology of discrimination, examining its definition in relation to prejudice and stereotypes, and discussing its prevalence. It outlines key theories such as social identity theory, the BIAS map, aversive racism, and system justification theory, explaining how these frameworks help understand the origins and manifestations of discrimination. The report also explores various measurement techniques used in social psychological studies, including both explicit and implicit measures, and presents findings from laboratory and field studies. Furthermore, it considers the systemic consequences of discrimination, encompassing its impact on intergroup relations, social mobility, and personal wellbeing. The report concludes by summarizing the key findings and offering insights into the multifaceted nature of discrimination within society.

84

Chapter 5

The Social Psychology of Discrimination:

Theory, Measurement and Consequences

Ananthi Al Ramiah, Miles Hewstone,

John F. Dovidio and Louis A. Penner

ocial psychologists engage with the prevalence and problems

of discrimination by studying the processes that underlie it.

Understanding when discrimination is likely to occur suggests

ways that we can overcome it. In this chapter, we begin by dis‐

cussing the ways in which social psychologists talk about dis‐

crimination and discussits prevalence. Second, we outline some

theories underlying the phenomenon. Third, we consider the

ways in which social psychological studies have measured dis‐

crimination, discussing findings from laboratory and field stud‐

ies with explicit and implicit measures. Fourth, we consider the

systemic consequences of discrimination and their implications

for intergrouprelations, social mobility and personal wellbeing.

Finally, we provide a summary and some conclusions.

Defining Discrimination

Social psychologistsare carefulto disentanglediscrimination

from its close cousins of prejudice and stereotypes. Prejudice re‐

fers to an unjustifiable negative attitude toward a group and its

individual members. Stereotypes are beliefs about the personal

S

Chapter 5

The Social Psychology of Discrimination:

Theory, Measurement and Consequences

Ananthi Al Ramiah, Miles Hewstone,

John F. Dovidio and Louis A. Penner

ocial psychologists engage with the prevalence and problems

of discrimination by studying the processes that underlie it.

Understanding when discrimination is likely to occur suggests

ways that we can overcome it. In this chapter, we begin by dis‐

cussing the ways in which social psychologists talk about dis‐

crimination and discussits prevalence. Second, we outline some

theories underlying the phenomenon. Third, we consider the

ways in which social psychological studies have measured dis‐

crimination, discussing findings from laboratory and field stud‐

ies with explicit and implicit measures. Fourth, we consider the

systemic consequences of discrimination and their implications

for intergrouprelations, social mobility and personal wellbeing.

Finally, we provide a summary and some conclusions.

Defining Discrimination

Social psychologistsare carefulto disentanglediscrimination

from its close cousins of prejudice and stereotypes. Prejudice re‐

fers to an unjustifiable negative attitude toward a group and its

individual members. Stereotypes are beliefs about the personal

S

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The Social Psychology of Discrimination

85

attributes of a group of people, and can be over‐generalised, inac‐

curate, and resistant to change in the presence of new informa‐

tion. Discrimination refers to unjustifiable negative behaviour to‐

wards a group or its members, where behaviour is adjudged to

include both actions towards, and judgements/decisions about,

group members.Correll et al. (2010, p. 46) provide a very useful

definition of discrimination as ‘behaviour directed towards cate‐

gory members that is consequential for their outcomes and that is

directed towards them not because of any particular deserving‐

ness or reciprocity, but simply because they happen to be mem‐

bersof that category’. The notion of ‘deservingness’ is central to

the expression and experience of discrimination. It is not an ob‐

jectively defined criterion but one that has its roots in historical

and present‐dayinequalitiesand societalnorms. Perpetrators

may see their behaviours as justified by the deservingness of the

targets, while the targets themselves may disagree. Thus the be‐

haviours, which some judge to be discriminatory, will not be seen

as such by others.

The expression of discrimination can broadly be classified

into two types: overt or direct, and subtle, unconscious or auto‐

matic. Manifestations include verbal and non‐verbal hostility

(Darley and Fazio, 1980; Word et al., 1974), avoidance of contact

(Cuddy et al., 2007; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006), aggressive ap‐

proach behaviours (Cuddy, et al., 2007) and the denial of oppor‐

tunities and access or equal treatment (Bobo, 2001; Sidanius and

Pratto, 1999).

Across a range of domains,cultures and historical periods,

there are and have been systemic disparities between members

of dominant and non‐dominant groups (Sidaniuis and Pratto,

1999). For example, ethnic minorities consistently experience

worse health outcomes (Barnett and Halverson, 2001;

Underwood et al., 2004), worse school performance (Cohen et

al., 2006), and harsher treatment in the justice system

(Steffensmeier and Demuth, 2000). In both business and aca‐

85

attributes of a group of people, and can be over‐generalised, inac‐

curate, and resistant to change in the presence of new informa‐

tion. Discrimination refers to unjustifiable negative behaviour to‐

wards a group or its members, where behaviour is adjudged to

include both actions towards, and judgements/decisions about,

group members.Correll et al. (2010, p. 46) provide a very useful

definition of discrimination as ‘behaviour directed towards cate‐

gory members that is consequential for their outcomes and that is

directed towards them not because of any particular deserving‐

ness or reciprocity, but simply because they happen to be mem‐

bersof that category’. The notion of ‘deservingness’ is central to

the expression and experience of discrimination. It is not an ob‐

jectively defined criterion but one that has its roots in historical

and present‐dayinequalitiesand societalnorms. Perpetrators

may see their behaviours as justified by the deservingness of the

targets, while the targets themselves may disagree. Thus the be‐

haviours, which some judge to be discriminatory, will not be seen

as such by others.

The expression of discrimination can broadly be classified

into two types: overt or direct, and subtle, unconscious or auto‐

matic. Manifestations include verbal and non‐verbal hostility

(Darley and Fazio, 1980; Word et al., 1974), avoidance of contact

(Cuddy et al., 2007; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006), aggressive ap‐

proach behaviours (Cuddy, et al., 2007) and the denial of oppor‐

tunities and access or equal treatment (Bobo, 2001; Sidanius and

Pratto, 1999).

Across a range of domains,cultures and historical periods,

there are and have been systemic disparities between members

of dominant and non‐dominant groups (Sidaniuis and Pratto,

1999). For example, ethnic minorities consistently experience

worse health outcomes (Barnett and Halverson, 2001;

Underwood et al., 2004), worse school performance (Cohen et

al., 2006), and harsher treatment in the justice system

(Steffensmeier and Demuth, 2000). In both business and aca‐

Making Equality Count

86

demic domains, women are paid less and hold positions of lower

status than men, controlling for occupation and qualifications

(Goldman et al., 2006). In terms of the labour market, sociologi‐

cal research shows that ethnic minority applicants tend to suffer

from a phenomenon known as the ethnic penalty. Ethnic penal‐

tiesare defined as the net disadvantages experienced by ethnic

minorities after controlling for their educational qualifications,

age and experience in the labour market (Heath and McMahon,

1997). While the ethnic penalty cannot be equated with dis‐

crimination, discrimination is likely to be a major factor respon‐

sible for its existence.This discrimination ranges from unequal

treatment that minority group members receive during the ap‐

plication process, and over the course of their education and so‐

cialisation, which can have grave consequences for the existence

of ‘bridging’ social networks, ‘spatial mismatch’ between labour

availability and opportunity, and differences in aspirations and

preferences(Heath and McMahon, 1997).

Theories of Discrimination

Several theories have shaped our understanding of intergroup

relations, prejudice and discrimination, and we focus on four

here: the social identity perspective, the ‘behaviours from inter‐

group affect and stereotypes’ map, aversive racism theory and

system justification theory.

As individuals living in a social context, we traverse the

continuum between our personal and collective selves. Differ‐

ent social contexts lead to the salience of particular group

memberships (Turner et al., 1987). The first theoretical frame‐

work that we outline, the social identity perspective (Tajfel and

Turner, 1979) holds that group members are motivated topro‐

tect their self‐esteem and achieve a positive and distinct social

identity. This drive for a positive social identity can result in

discrimination, which is expressed as either direct harm to the

86

demic domains, women are paid less and hold positions of lower

status than men, controlling for occupation and qualifications

(Goldman et al., 2006). In terms of the labour market, sociologi‐

cal research shows that ethnic minority applicants tend to suffer

from a phenomenon known as the ethnic penalty. Ethnic penal‐

tiesare defined as the net disadvantages experienced by ethnic

minorities after controlling for their educational qualifications,

age and experience in the labour market (Heath and McMahon,

1997). While the ethnic penalty cannot be equated with dis‐

crimination, discrimination is likely to be a major factor respon‐

sible for its existence.This discrimination ranges from unequal

treatment that minority group members receive during the ap‐

plication process, and over the course of their education and so‐

cialisation, which can have grave consequences for the existence

of ‘bridging’ social networks, ‘spatial mismatch’ between labour

availability and opportunity, and differences in aspirations and

preferences(Heath and McMahon, 1997).

Theories of Discrimination

Several theories have shaped our understanding of intergroup

relations, prejudice and discrimination, and we focus on four

here: the social identity perspective, the ‘behaviours from inter‐

group affect and stereotypes’ map, aversive racism theory and

system justification theory.

As individuals living in a social context, we traverse the

continuum between our personal and collective selves. Differ‐

ent social contexts lead to the salience of particular group

memberships (Turner et al., 1987). The first theoretical frame‐

work that we outline, the social identity perspective (Tajfel and

Turner, 1979) holds that group members are motivated topro‐

tect their self‐esteem and achieve a positive and distinct social

identity. This drive for a positive social identity can result in

discrimination, which is expressed as either direct harm to the

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The Social Psychology of Discrimination

87

outgroup, or more commonly and spontaneously, as giving

preferential treatment to the ingroup, a phenomenon known as

ingroup bias.

Going further, and illustrating the general tendency that

humans have to discriminate, the minimal group paradigm stud‐

ies (Tajfel and Turner, 1986) reveal how mere categorisation as a

group member can leadto ingroup bias, the favouring of in‐

group members over outgroup members in evaluations and allo‐

cation of resources (Turner, 1978). In the minimal group para‐

digm studies, participants are classified as belonging to arbitrary

groups (e.g. people who tend to overestimate or underestimate

the number of dots presented tothem) and evaluate members of

the ingroup and outgroup, and take part in a reward allocation

task (Tajfel and Turner, 1986) between the two groups. Results

across hundreds of studies show that participants rate ingroup

members more positively, exhibit preference for ingroup mem‐

bers in allocation of resources, and want tomaintain maximal

difference in allocation between ingroup and outgroup mem‐

bers, thereby giving outgroup members less than an equality

norm would require. Given the fact that group membership in

this paradigm does not involve a deeply‐held attachment and

operates within the wider context of equality norms, this ten‐

dencyto discriminate is an important finding, and indicative of

the spontaneous nature of prejudice and discrimination in inter‐

group contexts (Al Ramiah et al., in press). Whereas social cate‐

gorisation is sufficient to create discriminatory treatment, often

motivated by ingroup favouritism, direct competition between

groups exacerbates this bias, typically generating responses di‐

rectly to disadvantage the outgroup, as well (Sherif et al., 1961).

Whereas social identity theory examines basic, general proc‐

esses leading to intergroup discrimination, the BIAS map (Be‐

haviours from Intergroup Affect and Stereotypes; see Cuddy, et

al., 2007) offers insights into the specific ways that we discrimi‐

nate against members of particular types of groups. The BIAS

87

outgroup, or more commonly and spontaneously, as giving

preferential treatment to the ingroup, a phenomenon known as

ingroup bias.

Going further, and illustrating the general tendency that

humans have to discriminate, the minimal group paradigm stud‐

ies (Tajfel and Turner, 1986) reveal how mere categorisation as a

group member can leadto ingroup bias, the favouring of in‐

group members over outgroup members in evaluations and allo‐

cation of resources (Turner, 1978). In the minimal group para‐

digm studies, participants are classified as belonging to arbitrary

groups (e.g. people who tend to overestimate or underestimate

the number of dots presented tothem) and evaluate members of

the ingroup and outgroup, and take part in a reward allocation

task (Tajfel and Turner, 1986) between the two groups. Results

across hundreds of studies show that participants rate ingroup

members more positively, exhibit preference for ingroup mem‐

bers in allocation of resources, and want tomaintain maximal

difference in allocation between ingroup and outgroup mem‐

bers, thereby giving outgroup members less than an equality

norm would require. Given the fact that group membership in

this paradigm does not involve a deeply‐held attachment and

operates within the wider context of equality norms, this ten‐

dencyto discriminate is an important finding, and indicative of

the spontaneous nature of prejudice and discrimination in inter‐

group contexts (Al Ramiah et al., in press). Whereas social cate‐

gorisation is sufficient to create discriminatory treatment, often

motivated by ingroup favouritism, direct competition between

groups exacerbates this bias, typically generating responses di‐

rectly to disadvantage the outgroup, as well (Sherif et al., 1961).

Whereas social identity theory examines basic, general proc‐

esses leading to intergroup discrimination, the BIAS map (Be‐

haviours from Intergroup Affect and Stereotypes; see Cuddy, et

al., 2007) offers insights into the specific ways that we discrimi‐

nate against members of particular types of groups. The BIAS

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Making Equality Count

88

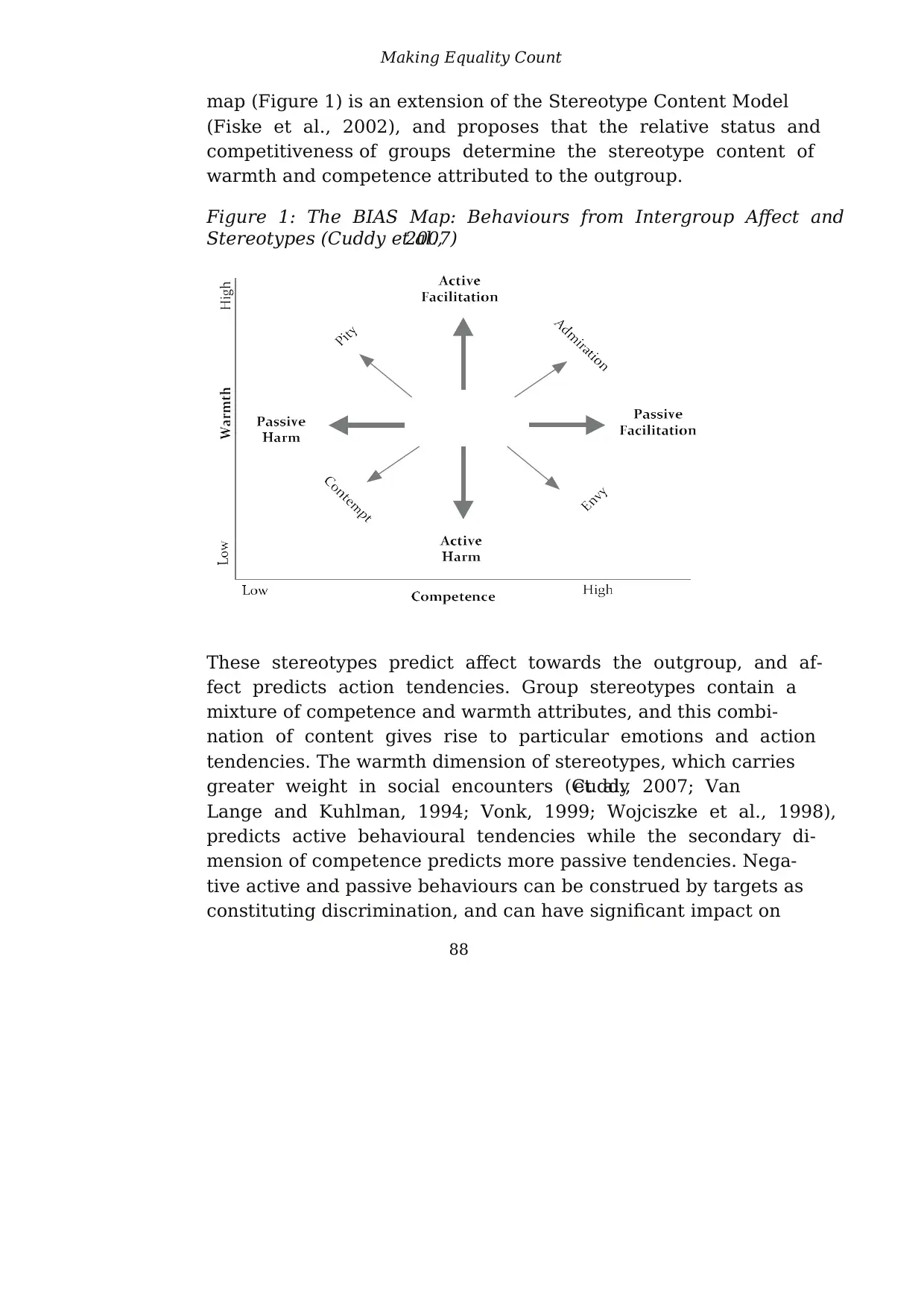

map (Figure 1) is an extension of the Stereotype Content Model

(Fiske et al., 2002), and proposes that the relative status and

competitiveness of groups determine the stereotype content of

warmth and competence attributed to the outgroup.

Figure 1: The BIAS Map: Behaviours from Intergroup Affect and

Stereotypes (Cuddy et al.,2007)

These stereotypes predict affect towards the outgroup, and af‐

fect predicts action tendencies. Group stereotypes contain a

mixture of competence and warmth attributes, and this combi‐

nation of content gives rise to particular emotions and action

tendencies. The warmth dimension of stereotypes, which carries

greater weight in social encounters (Cuddyet al., 2007; Van

Lange and Kuhlman, 1994; Vonk, 1999; Wojciszke et al., 1998),

predicts active behavioural tendencies while the secondary di‐

mension of competence predicts more passive tendencies. Nega‐

tive active and passive behaviours can be construed by targets as

constituting discrimination, and can have significant impact on

88

map (Figure 1) is an extension of the Stereotype Content Model

(Fiske et al., 2002), and proposes that the relative status and

competitiveness of groups determine the stereotype content of

warmth and competence attributed to the outgroup.

Figure 1: The BIAS Map: Behaviours from Intergroup Affect and

Stereotypes (Cuddy et al.,2007)

These stereotypes predict affect towards the outgroup, and af‐

fect predicts action tendencies. Group stereotypes contain a

mixture of competence and warmth attributes, and this combi‐

nation of content gives rise to particular emotions and action

tendencies. The warmth dimension of stereotypes, which carries

greater weight in social encounters (Cuddyet al., 2007; Van

Lange and Kuhlman, 1994; Vonk, 1999; Wojciszke et al., 1998),

predicts active behavioural tendencies while the secondary di‐

mension of competence predicts more passive tendencies. Nega‐

tive active and passive behaviours can be construed by targets as

constituting discrimination, and can have significant impact on

The Social Psychology of Discrimination

89

the quality of their lives. Examples of negative passive behav‐

iours are ignoring another’s presence, not making eye contact

with them, excluding members of certain groups from getting

opportunities, and so on, while examples of negative active be‐

haviours include supporting institutional racism or voting for

anti‐immigration political parties. Theseexamples show that

discriminatory behaviours can range from the subtle to the

overt, and the particular views that we have about each out‐

group determines the manifestation of discrimination.

The third theory that we consider, aversive racism (Dovidio

and Gaertner, 2004) complements social identity theory (which

suggests the pervasiveness ofintergroup discrimination) and the

BIAS map (which helps identify the form in which discrimina‐

tion will be manifested) by further identifying when discrimina‐

tion will be manifested or inhibited. The aversive racism frame‐

work essentially evolved to understand the psychological con‐

flict that afflicts many White Americans with regard to theirra‐

cial attitudes.Changingsocial norms increasinglyprohibit

prejudice and discrimination towards minority and other stig‐

matised groups (Crandall et al., 2002), and work in the United

States has shown that appearing racist has become aversive to

many White Americans (Dovidio and Gaertner, 2004; Gaertner

and Dovidio, 1986; Katz andHass, 1988; McConahay, 1986) in

terms not only of their public image but also of their private self

concept. However, a multitude of individual and societal factors

continue to reinforce stereotypes and negative evaluative biases

(which are rooted, in part, in biases identified by social identity

theory), which result in continued expression and experience of

discrimination. Equality norms give rise to considerable psycho‐

logical conflict in which people regard prejudice as unjust and

offensive, but remain unable to fully suppress their own biases.

Thus ethnic and racial attitudes have become more complex

than they were in the past.

89

the quality of their lives. Examples of negative passive behav‐

iours are ignoring another’s presence, not making eye contact

with them, excluding members of certain groups from getting

opportunities, and so on, while examples of negative active be‐

haviours include supporting institutional racism or voting for

anti‐immigration political parties. Theseexamples show that

discriminatory behaviours can range from the subtle to the

overt, and the particular views that we have about each out‐

group determines the manifestation of discrimination.

The third theory that we consider, aversive racism (Dovidio

and Gaertner, 2004) complements social identity theory (which

suggests the pervasiveness ofintergroup discrimination) and the

BIAS map (which helps identify the form in which discrimina‐

tion will be manifested) by further identifying when discrimina‐

tion will be manifested or inhibited. The aversive racism frame‐

work essentially evolved to understand the psychological con‐

flict that afflicts many White Americans with regard to theirra‐

cial attitudes.Changingsocial norms increasinglyprohibit

prejudice and discrimination towards minority and other stig‐

matised groups (Crandall et al., 2002), and work in the United

States has shown that appearing racist has become aversive to

many White Americans (Dovidio and Gaertner, 2004; Gaertner

and Dovidio, 1986; Katz andHass, 1988; McConahay, 1986) in

terms not only of their public image but also of their private self

concept. However, a multitude of individual and societal factors

continue to reinforce stereotypes and negative evaluative biases

(which are rooted, in part, in biases identified by social identity

theory), which result in continued expression and experience of

discrimination. Equality norms give rise to considerable psycho‐

logical conflict in which people regard prejudice as unjust and

offensive, but remain unable to fully suppress their own biases.

Thus ethnic and racial attitudes have become more complex

than they were in the past.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Making Equality Count

90

According to the aversive racism framework, people resolve

this conflict by upholding egalitarian norms and simultaneously

maintaining subtle or automatic forms of prejudice. Specifically,

people generally will not discriminate in situations in which

right and wrong is clearly defined; discrimination would be ob‐

vious to others and to oneself, and aversiveracists do not want

to appear or be discriminatory. However, aversive racists will

systematically discriminate when appropriate behaviours are not

clearly prescribed or they can justify their behaviour on the basis

of some factor other than race (see Dovidio and Gaertner, 2004).

The pervasiveness of discrimination and its systematic, andof‐

ten subtle, expression shapes society in ways that perpetuate in‐

equities. The final theory that we outline is system justification

theory, which hinges on the finding that low‐status groups in ‘un‐

equal social systems … internalize a sense of personal or collective

inferiority’ (Jost et al., 2001, p. 367).System justification theorists

argue that the social identity perspective posited need for positive

distinctiveness as a function of feeling good about oneself (ego

justification) and one’s group (group justification) is related (posi‐

tively or negatively, depending on your status) to the belief that

the system in which the groups arebased is fair (Jost and Banaji,

1994). For high‐status groups, ego and group justification corre‐

spond to a belief that the system is just and that their high‐status

is a reward for their worthiness. This leads to ingroup bias. People

with a history of personal and group advantage often derive the

prescriptive from the descriptive, or in other words, labour under

the 'is‐ought' illusion (Hume, 1939); they believe that as this is

what the world looks like and has looked like for a long time, this

is in fact what it should look like. For low‐status group members,

however, these justification needs can be at odds (Jost and Bur‐

gess, 2000) if they believe that the system is just. Their low‐status

can be seen as deserved punishment for their unworthiness and

can lead to the expression of outgroup bias, or a sense that the

outgroup is betterand therefore ought to be privileged. Thus sys‐

90

According to the aversive racism framework, people resolve

this conflict by upholding egalitarian norms and simultaneously

maintaining subtle or automatic forms of prejudice. Specifically,

people generally will not discriminate in situations in which

right and wrong is clearly defined; discrimination would be ob‐

vious to others and to oneself, and aversiveracists do not want

to appear or be discriminatory. However, aversive racists will

systematically discriminate when appropriate behaviours are not

clearly prescribed or they can justify their behaviour on the basis

of some factor other than race (see Dovidio and Gaertner, 2004).

The pervasiveness of discrimination and its systematic, andof‐

ten subtle, expression shapes society in ways that perpetuate in‐

equities. The final theory that we outline is system justification

theory, which hinges on the finding that low‐status groups in ‘un‐

equal social systems … internalize a sense of personal or collective

inferiority’ (Jost et al., 2001, p. 367).System justification theorists

argue that the social identity perspective posited need for positive

distinctiveness as a function of feeling good about oneself (ego

justification) and one’s group (group justification) is related (posi‐

tively or negatively, depending on your status) to the belief that

the system in which the groups arebased is fair (Jost and Banaji,

1994). For high‐status groups, ego and group justification corre‐

spond to a belief that the system is just and that their high‐status

is a reward for their worthiness. This leads to ingroup bias. People

with a history of personal and group advantage often derive the

prescriptive from the descriptive, or in other words, labour under

the 'is‐ought' illusion (Hume, 1939); they believe that as this is

what the world looks like and has looked like for a long time, this

is in fact what it should look like. For low‐status group members,

however, these justification needs can be at odds (Jost and Bur‐

gess, 2000) if they believe that the system is just. Their low‐status

can be seen as deserved punishment for their unworthiness and

can lead to the expression of outgroup bias, or a sense that the

outgroup is betterand therefore ought to be privileged. Thus sys‐

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The Social Psychology of Discrimination

91

tem justification theory extends the social identity perspective to

explain why inequality and discrimination amongst groups is per‐

petuated and tolerated.

While these theories underlying discrimination are by no

means exhaustive of the social psychological literature, we be‐

lieve that these approaches help explain why, how, and when

discrimination occurs andis perpetuated over time. These theo‐

ries thus offer a solid grounding from which to consider the

studies of discrimination that follow.

Measuring Discrimination

The United States General Social Survey dropped its equal‐

employment‐opportunity question because of near‐unanimous

support for the principle (Quillan, 2006). However, the evolu‐

tion and predictive power of the theories just discussed speak to

the fact that prejudice and discrimination, rather than evaporat‐

ing in the heat of social change, remain strong and reliable fea‐

tures of intergroup life. There are overt and subtle ways to cap‐

ture the impulses and evaluations that precede discrimination.

Explicit measures ofprejudice are self‐report measuresin

which the participants state their attitudes about, or action ten‐

dencies toward, a particular target. These measures presume that

participants are conscious of their evaluations and behavioural

tendencies, and are constructed in a way to reduce the amount of

socially desirable responding.In meta‐analyses of the relationship

between explicit prejudice and discrimination, the authors found

a modest correlation between the two (r = .32: Dovidio et al., 1996;

r=.36: Greenwald et al., 2009). Despite the modest effect sizes, the

fact that they are derived from studies conducted in a range of

situations and intergroup contexts suggests the reliability of the

relationships, and the value of explicit measures.

However, as our review of theories of discrimination sug‐

gests, biases do not necessarily have to be conscious or inten‐

91

tem justification theory extends the social identity perspective to

explain why inequality and discrimination amongst groups is per‐

petuated and tolerated.

While these theories underlying discrimination are by no

means exhaustive of the social psychological literature, we be‐

lieve that these approaches help explain why, how, and when

discrimination occurs andis perpetuated over time. These theo‐

ries thus offer a solid grounding from which to consider the

studies of discrimination that follow.

Measuring Discrimination

The United States General Social Survey dropped its equal‐

employment‐opportunity question because of near‐unanimous

support for the principle (Quillan, 2006). However, the evolu‐

tion and predictive power of the theories just discussed speak to

the fact that prejudice and discrimination, rather than evaporat‐

ing in the heat of social change, remain strong and reliable fea‐

tures of intergroup life. There are overt and subtle ways to cap‐

ture the impulses and evaluations that precede discrimination.

Explicit measures ofprejudice are self‐report measuresin

which the participants state their attitudes about, or action ten‐

dencies toward, a particular target. These measures presume that

participants are conscious of their evaluations and behavioural

tendencies, and are constructed in a way to reduce the amount of

socially desirable responding.In meta‐analyses of the relationship

between explicit prejudice and discrimination, the authors found

a modest correlation between the two (r = .32: Dovidio et al., 1996;

r=.36: Greenwald et al., 2009). Despite the modest effect sizes, the

fact that they are derived from studies conducted in a range of

situations and intergroup contexts suggests the reliability of the

relationships, and the value of explicit measures.

However, as our review of theories of discrimination sug‐

gests, biases do not necessarily have to be conscious or inten‐

Making Equality Count

92

tional to create unfair discrimination.Implicit measuresof

prejudice capture the evaluations and beliefs that are automati‐

cally, often unconsciously, activated by the presence or thought

of the target group (Dovidio et al., 2001). These measures over‐

come the social desirability concerns that plague explicit meas‐

ures because they allow usto capture prejudice that people may

be unwilling and/or unable to express (Fazio and Olson, 2003).

The Implicit Association Test (IAT) is an example of implicit

measurement (Greenwald et al., 1998), that is based on the find‐

ing that people make connections more quickly between pairs of

ideas that arealready related in our minds. Thus, it should be

more difficult, and hence take longer, to produce evaluatively

incompatible than compatible responses. For example, in the

case of ageism, people typically take longer to pair the words

‘old’ and ‘good’ than they do to pair the words ‘old’ and ‘bad’. It

is considered to be an instance of prejudice because it involves a

bias in our minds such that there are stronger mental associa‐

tions between stereotype‐consistent features (typically negative)

and particular groups than between stereotype‐inconsistent fea‐

tures and group membership. The time taken to respond does

not dependon any essential or accurate feature of the groups in

question,but reflectswell‐learnedculturalassociationsthat

automatically come to mind (Blair et al., 2004). In a meta‐analysis

of the relationship between implicit prejudice and discrimination,

the authors found a weak‐to‐modestrelationship(r = .27:

Greenwald etal., 2009), though in the context of studies that

dealt with Black‐White relations in the US, the relationship be‐

tween implicit measures and discrimination (r = .24) was stronger

than that between explicit measures and discrimination (r= .12).

Experiments on unobtrusive forms of prejudice show that

White bias againstBlacks is more prevalent than indicated by

surveys (Crosby et al., 1980). Despite people’s best intentions,

their ethnically biased cognitions and associations may persist.

The result is a modern, subtle form of prejudice (that can be

92

tional to create unfair discrimination.Implicit measuresof

prejudice capture the evaluations and beliefs that are automati‐

cally, often unconsciously, activated by the presence or thought

of the target group (Dovidio et al., 2001). These measures over‐

come the social desirability concerns that plague explicit meas‐

ures because they allow usto capture prejudice that people may

be unwilling and/or unable to express (Fazio and Olson, 2003).

The Implicit Association Test (IAT) is an example of implicit

measurement (Greenwald et al., 1998), that is based on the find‐

ing that people make connections more quickly between pairs of

ideas that arealready related in our minds. Thus, it should be

more difficult, and hence take longer, to produce evaluatively

incompatible than compatible responses. For example, in the

case of ageism, people typically take longer to pair the words

‘old’ and ‘good’ than they do to pair the words ‘old’ and ‘bad’. It

is considered to be an instance of prejudice because it involves a

bias in our minds such that there are stronger mental associa‐

tions between stereotype‐consistent features (typically negative)

and particular groups than between stereotype‐inconsistent fea‐

tures and group membership. The time taken to respond does

not dependon any essential or accurate feature of the groups in

question,but reflectswell‐learnedculturalassociationsthat

automatically come to mind (Blair et al., 2004). In a meta‐analysis

of the relationship between implicit prejudice and discrimination,

the authors found a weak‐to‐modestrelationship(r = .27:

Greenwald etal., 2009), though in the context of studies that

dealt with Black‐White relations in the US, the relationship be‐

tween implicit measures and discrimination (r = .24) was stronger

than that between explicit measures and discrimination (r= .12).

Experiments on unobtrusive forms of prejudice show that

White bias againstBlacks is more prevalent than indicated by

surveys (Crosby et al., 1980). Despite people’s best intentions,

their ethnically biased cognitions and associations may persist.

The result is a modern, subtle form of prejudice (that can be

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The Social Psychology of Discrimination

93

tapped by both implicit and explicit measures) that goes under‐

ground so as not to conflict with anti‐racist norms while it con‐

tinues to shape people’scognition,emotionsand behaviours

(Dovidio and Gaertner, 2004). Discrimination may take the form

of blaming the outgroup for their disadvantage (Hewstone et al.,

2002;Jost and Banaji, 1994; Pettigrew et al., 1998), not supporting

policies that uplift outgroup members (Gilens, 1996), avoidance of

interactions with outgroup members (Van Laar et al.,2005),

automatically treating outgroup members as embodying stereo‐

typical traits of their groups (Fiske, 1998), preference for the in‐

group over outgroup leadingto preferential reward allocation

(Tajfel and Turner, 1986), and ambivalent responses to the out‐

group, that is having mixed positive and negative views about

outgroup members (Glick and Fiske, 1996) which can lead to

avoidance and passive harm to the outgroup (Cuddy et al., 2007).

We now consider two empirical approaches– laboratory and

field studies – to the study of discrimination and the processes

that underlie it.

Laboratory Studies

In a laboratory study, the investigator manipulates a variable of

interest, randomly assigns participants to different conditions of

the variable or treatments, and measures their responses to the

manipulation while attempting to control for other relevant

conditions or attributes.

Laboratory studies can reveal both subtle and blatant dis‐

criminatory responses, and illuminate the processes that shape

these responses. In a classic social psychological paper, Word et

al. (1974) studied the presence and effects of subtle non‐verbal

discriminatory behaviours among university studentsin a series

of two studies. In Study 1, they identified non‐verbal discrimina‐

tory behaviours from White interviewers of Black versus White

job applicants. In Study 2 they were able to demonstrate that

93

tapped by both implicit and explicit measures) that goes under‐

ground so as not to conflict with anti‐racist norms while it con‐

tinues to shape people’scognition,emotionsand behaviours

(Dovidio and Gaertner, 2004). Discrimination may take the form

of blaming the outgroup for their disadvantage (Hewstone et al.,

2002;Jost and Banaji, 1994; Pettigrew et al., 1998), not supporting

policies that uplift outgroup members (Gilens, 1996), avoidance of

interactions with outgroup members (Van Laar et al.,2005),

automatically treating outgroup members as embodying stereo‐

typical traits of their groups (Fiske, 1998), preference for the in‐

group over outgroup leadingto preferential reward allocation

(Tajfel and Turner, 1986), and ambivalent responses to the out‐

group, that is having mixed positive and negative views about

outgroup members (Glick and Fiske, 1996) which can lead to

avoidance and passive harm to the outgroup (Cuddy et al., 2007).

We now consider two empirical approaches– laboratory and

field studies – to the study of discrimination and the processes

that underlie it.

Laboratory Studies

In a laboratory study, the investigator manipulates a variable of

interest, randomly assigns participants to different conditions of

the variable or treatments, and measures their responses to the

manipulation while attempting to control for other relevant

conditions or attributes.

Laboratory studies can reveal both subtle and blatant dis‐

criminatory responses, and illuminate the processes that shape

these responses. In a classic social psychological paper, Word et

al. (1974) studied the presence and effects of subtle non‐verbal

discriminatory behaviours among university studentsin a series

of two studies. In Study 1, they identified non‐verbal discrimina‐

tory behaviours from White interviewers of Black versus White

job applicants. In Study 2 they were able to demonstrate that

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Making Equality Count

94

such subtle discriminatory behaviours when directed against

White applicantsby White interviewerselicited behaviours

stereotypically associated with Blacks, and led to poor perform‐

ance in the interview,a demonstrationof the self‐fulfilling

prophesy; i.e. treating others like they will fail causes them to

fail. This study powerfully demonstrated that negativestereo‐

types about an outgroup can give rise to negative passive behav‐

iour, which in turn can have performance‐reducingconse‐

quences for the recipients of such non‐verbal behaviours. In le‐

gal settings, negative verbal and non‐verbal treatment may con‐

stitute unlawful discrimination when they result in thecreation

of a hostile work environment (Blank et al., 2004).

In an effort to examine the relationship between explicit and

implicit measures of prejudice and verbal and non‐verbal dis‐

criminatory behaviours, Dovidio et al. (2002) first asked White

university student participants to complete a self‐report meas‐

ure of theirattitudes towards Blacks. Some time later, during the

experimental phase of the study, they subliminally primed par‐

ticipants with White and Black faces and positive and negative

non‐stereotypic characteristics which participants had to pair

together. Subliminal priming refers to stimuli presented fleet‐

ingly, outside conscious awareness. Their response timeto each

category‐word combination (e.g. black/ friendly) was measured

as an indication of their implicit associations, with shorter re‐

sponse latencies reflecting higher implicit associations of par‐

ticular ethnic groups with particular stereotypes. Then partici‐

pants, who were told they were taking part in an unrelated

study, engaged in aninteraction task first with a White (Black)

confederate and then with a Black (White) confederate; these

interactions were videotaped. After each interaction, both the

participant and the confederate completed rating scales of their

own and the confederate’s friendliness. In the next stage of the

study, the videotaped interactions were playedin silent mode to

two judges who rated the friendliness of non‐verbal behaviours

94

such subtle discriminatory behaviours when directed against

White applicantsby White interviewerselicited behaviours

stereotypically associated with Blacks, and led to poor perform‐

ance in the interview,a demonstrationof the self‐fulfilling

prophesy; i.e. treating others like they will fail causes them to

fail. This study powerfully demonstrated that negativestereo‐

types about an outgroup can give rise to negative passive behav‐

iour, which in turn can have performance‐reducingconse‐

quences for the recipients of such non‐verbal behaviours. In le‐

gal settings, negative verbal and non‐verbal treatment may con‐

stitute unlawful discrimination when they result in thecreation

of a hostile work environment (Blank et al., 2004).

In an effort to examine the relationship between explicit and

implicit measures of prejudice and verbal and non‐verbal dis‐

criminatory behaviours, Dovidio et al. (2002) first asked White

university student participants to complete a self‐report meas‐

ure of theirattitudes towards Blacks. Some time later, during the

experimental phase of the study, they subliminally primed par‐

ticipants with White and Black faces and positive and negative

non‐stereotypic characteristics which participants had to pair

together. Subliminal priming refers to stimuli presented fleet‐

ingly, outside conscious awareness. Their response timeto each

category‐word combination (e.g. black/ friendly) was measured

as an indication of their implicit associations, with shorter re‐

sponse latencies reflecting higher implicit associations of par‐

ticular ethnic groups with particular stereotypes. Then partici‐

pants, who were told they were taking part in an unrelated

study, engaged in aninteraction task first with a White (Black)

confederate and then with a Black (White) confederate; these

interactions were videotaped. After each interaction, both the

participant and the confederate completed rating scales of their

own and the confederate’s friendliness. In the next stage of the

study, the videotaped interactions were playedin silent mode to

two judges who rated the friendliness of non‐verbal behaviours

The Social Psychology of Discrimination

95

of the participants.As the authorsanticipated,the explicit

prejudice measure significantly predicted bias in White partici‐

pants’ verbal behaviour to Black relative to White confederates.

The implicit measure significantly predicted White participants’

non‐verbal friendliness and the extent to which the confederates

and observers perceived bias in the participants’ friendliness.

This study powerfully elucidates a point raised earlier in this

chapter, that behaviours which some judge to be discriminatory

will not be seen as such by others. Specifically, implicit negative

attitudes towards the outgroup can lead majority/minority or

advantaged/disadvantaged group members to form divergent

impressions of their interaction partner. Theseimplicit attitudes

are associated in this study and in the one by Word et al. (1974)

with non‐verbal behaviours (what the BIAS map would term

passive harm), which led to the development of self‐fulfilling

prophesies. The inconsistency of one’s implicit and explicit atti‐

tudes explains why majority and minoritygroup members ex‐

perience interethnic interactions in such divergent ways; major‐

ity group members refer to their explicit attitudes when thinking

about interactionswith outgroupmembers,while minority

group members seem to rely more on the majority group mem‐

ber’s implicit attitude, as reflected in their non‐verbal behav‐

iours,to determine the friendliness of the interaction.

Consistent with the predictions of aversive racism, discrimi‐

nation against Blacks in helping behaviours was more likely

when participants could rationalise decisions not to help with

reasons that had nothing to do with ethnicity. For example, us‐

ing university students, Gaertner and Dovidio (1977) showed

that in an emergency, Black victims were less likely to be helped

when the participant had the opportunity to diffuse responsibil‐

ity over several other people, who could potentially be called

upon to help; however, Blacks and Whites were helped equally

when the participant was the only bystander. Ina meta‐analysis

on helping behaviours, Saucier et al. (2005) found that when

95

of the participants.As the authorsanticipated,the explicit

prejudice measure significantly predicted bias in White partici‐

pants’ verbal behaviour to Black relative to White confederates.

The implicit measure significantly predicted White participants’

non‐verbal friendliness and the extent to which the confederates

and observers perceived bias in the participants’ friendliness.

This study powerfully elucidates a point raised earlier in this

chapter, that behaviours which some judge to be discriminatory

will not be seen as such by others. Specifically, implicit negative

attitudes towards the outgroup can lead majority/minority or

advantaged/disadvantaged group members to form divergent

impressions of their interaction partner. Theseimplicit attitudes

are associated in this study and in the one by Word et al. (1974)

with non‐verbal behaviours (what the BIAS map would term

passive harm), which led to the development of self‐fulfilling

prophesies. The inconsistency of one’s implicit and explicit atti‐

tudes explains why majority and minoritygroup members ex‐

perience interethnic interactions in such divergent ways; major‐

ity group members refer to their explicit attitudes when thinking

about interactionswith outgroupmembers,while minority

group members seem to rely more on the majority group mem‐

ber’s implicit attitude, as reflected in their non‐verbal behav‐

iours,to determine the friendliness of the interaction.

Consistent with the predictions of aversive racism, discrimi‐

nation against Blacks in helping behaviours was more likely

when participants could rationalise decisions not to help with

reasons that had nothing to do with ethnicity. For example, us‐

ing university students, Gaertner and Dovidio (1977) showed

that in an emergency, Black victims were less likely to be helped

when the participant had the opportunity to diffuse responsibil‐

ity over several other people, who could potentially be called

upon to help; however, Blacks and Whites were helped equally

when the participant was the only bystander. Ina meta‐analysis

on helping behaviours, Saucier et al. (2005) found that when

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 29

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.