A Stakeholder Model for Effective Water Resource Project Management

VerifiedAdded on 2024/01/18

|19

|15402

|208

Report

AI Summary

This report explores the application of the stakeholder model to water resource development projects, addressing issues like time and cost overruns and the neglect of less-vocal stakeholders. It proposes a three-tier approach to identify and classify stakeholders into an eight-fold classification, exemplified by the Sardar Sarovar Project. The report suggests a four-level stakeholder relationship model, aiming for an 'engaged' level to create synergy and optimize stakeholder value. It introduces a 'comparative measure' approach for evaluating stakeholder value, emphasizing moral reasoning and rational valuation of emotions and conditions. The implications of the stakeholder model include its role in sensing, scanning, signaling, and strategizing, as well as its utility in investigation, redressal, and management of stakeholder issues, ultimately contributing to balanced and sustainable water resource development.

The Stakeholder Model for

Water Resource Projects

The water resource development projects in India have been facing problems due to

immense time and cost overruns. There is also the risk of taking a skewed path whe

planners and policy makers tend to ignore the existence of less-vocal and non-vocal

entities. This could be due to a lack of a proper framework for understanding the na

and dimensions of the competing, conflicting, and varied demands both by the adve

affected and the beneficiary entities. This calls for identifying various stakeholders o

water resource projects so as to develop a stakeholder’s model which is expected to

only help categorize the stakeholders along the lines of beneficial and adverse effec

also to gauge their capacity to influence change in the course of the projects.

The stakeholders can be defined as individuals or group of entities who may be

affected by the water resource project during its conception, construction, and opera

who, in turn, may also influence the future course of the project. For identifying the

stakeholders, this paper proposes a three-tier approach leading to an eight-fold clas

cation of stakeholders.

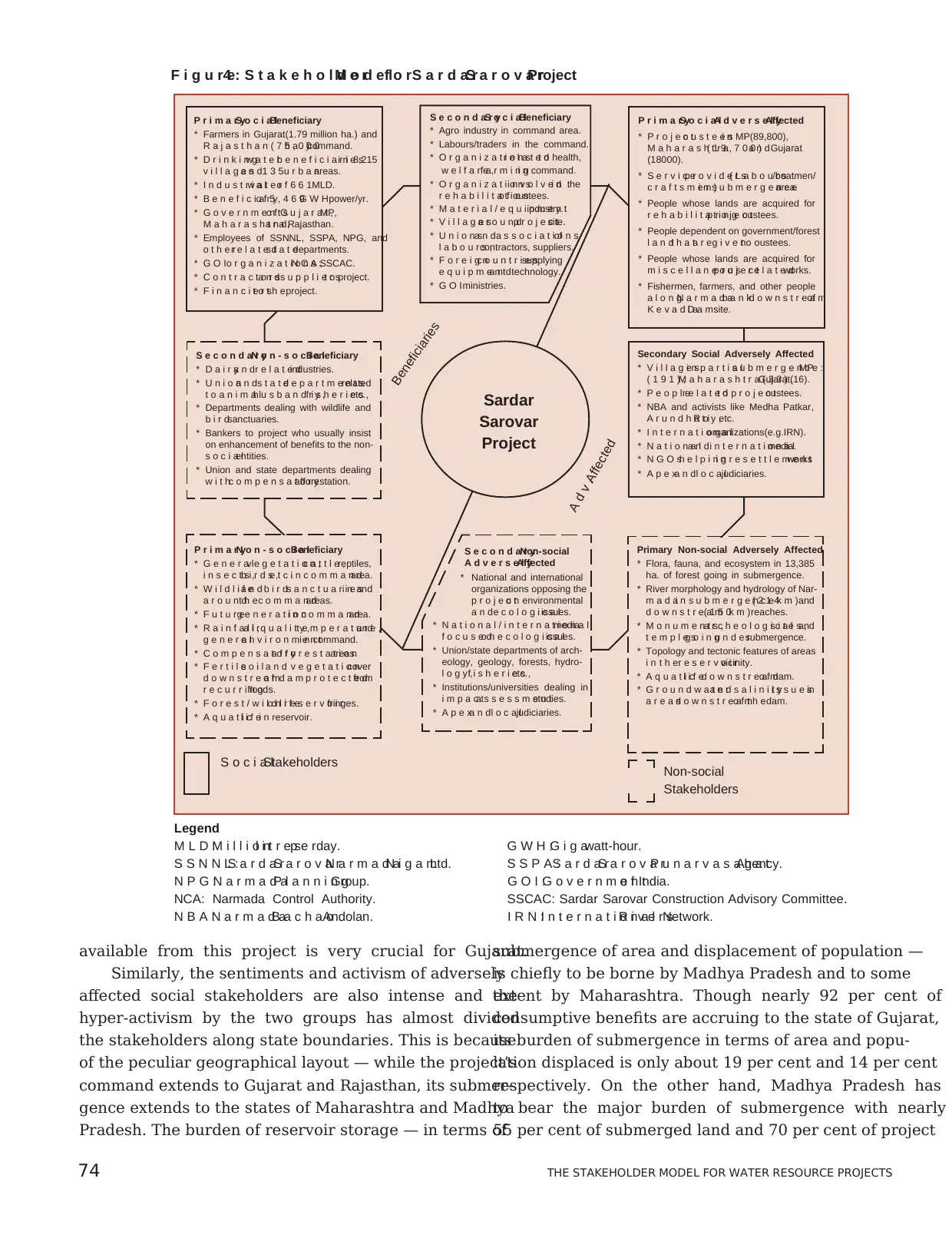

As exemplified by the Sardar Sarovar Project, the identified classes of stakeholde

can be structured into a model indicating their octagonal congregate of influences a

the networked effect on the water resource project. Since stakeholders are importan

social and economic assets for public good, the best recourse is to create a win-win

situation for all of them or work out a balance in relationships with its diverse consti

for optimum realization of stakeholder value. With these objectives in view, this pap

suggests a four-level stakeholder relationship model incorporating levels of: (i) unin-

formed, (ii) compliant, (iii) responsive, (iv) engaged. On attaining the highest ‘engag

level, the project is able to create synergy among all elements of its relationship net

so as to realize optimum stakeholder value.

The measurement of stakeholder value is of immense importance for understand

and responding to shifts in stakeholder expectations and reactions. The propo

‘comparative measure’ approach for evaluating stakeholder value has the advantag

being discernible, forward-looking, and capable of eliminating the element of percep

tion in measurement by taking a comparative (rather than absolute) measure

impact on beneficiary and adversely affected groups of stakeholders. This approach

requires moral reasoning, involving a rational valuation of emotions (joy or grief) in

of social stakeholders, and conditions (favourable or unfavourable) in case of non-so

stakeholders, as epitomized by the factual illustration of a decision related to the he

of the Sardar Sarovar Dam.

The implications of the stakeholder model are as follows:

It serves the ‘4S’ management functions of Sensing, Scanning, Signalling, and

Strategizing.

It can be used as a powerful tool for investigation, prognostication, redressal, an

management of stakeholder issues.

It can also be aptly used for guiding the continuous process of national water

resource reforms with an aim to achieve balanced and sustainable developme

with minimum conflicts.

To conclude, water resource projects would ultimately help maximize societal we

fare and improve the governance system besides becoming stakeholder responsive.

KEY WORDS

Stakeholder Model

Project Management

Water Resource Management

Governance System

Executive Summary

G C Maheshwari and B Ravi Kumar Pillai

presents articles focusing on managerial

applications of management practices,

theories, and concepts

I N T E R F A C E S

VIKALPA • VOLUME 29 • NO 1 • JANUARY - MARCH 2004 63

Water Resource Projects

The water resource development projects in India have been facing problems due to

immense time and cost overruns. There is also the risk of taking a skewed path whe

planners and policy makers tend to ignore the existence of less-vocal and non-vocal

entities. This could be due to a lack of a proper framework for understanding the na

and dimensions of the competing, conflicting, and varied demands both by the adve

affected and the beneficiary entities. This calls for identifying various stakeholders o

water resource projects so as to develop a stakeholder’s model which is expected to

only help categorize the stakeholders along the lines of beneficial and adverse effec

also to gauge their capacity to influence change in the course of the projects.

The stakeholders can be defined as individuals or group of entities who may be

affected by the water resource project during its conception, construction, and opera

who, in turn, may also influence the future course of the project. For identifying the

stakeholders, this paper proposes a three-tier approach leading to an eight-fold clas

cation of stakeholders.

As exemplified by the Sardar Sarovar Project, the identified classes of stakeholde

can be structured into a model indicating their octagonal congregate of influences a

the networked effect on the water resource project. Since stakeholders are importan

social and economic assets for public good, the best recourse is to create a win-win

situation for all of them or work out a balance in relationships with its diverse consti

for optimum realization of stakeholder value. With these objectives in view, this pap

suggests a four-level stakeholder relationship model incorporating levels of: (i) unin-

formed, (ii) compliant, (iii) responsive, (iv) engaged. On attaining the highest ‘engag

level, the project is able to create synergy among all elements of its relationship net

so as to realize optimum stakeholder value.

The measurement of stakeholder value is of immense importance for understand

and responding to shifts in stakeholder expectations and reactions. The propo

‘comparative measure’ approach for evaluating stakeholder value has the advantag

being discernible, forward-looking, and capable of eliminating the element of percep

tion in measurement by taking a comparative (rather than absolute) measure

impact on beneficiary and adversely affected groups of stakeholders. This approach

requires moral reasoning, involving a rational valuation of emotions (joy or grief) in

of social stakeholders, and conditions (favourable or unfavourable) in case of non-so

stakeholders, as epitomized by the factual illustration of a decision related to the he

of the Sardar Sarovar Dam.

The implications of the stakeholder model are as follows:

It serves the ‘4S’ management functions of Sensing, Scanning, Signalling, and

Strategizing.

It can be used as a powerful tool for investigation, prognostication, redressal, an

management of stakeholder issues.

It can also be aptly used for guiding the continuous process of national water

resource reforms with an aim to achieve balanced and sustainable developme

with minimum conflicts.

To conclude, water resource projects would ultimately help maximize societal we

fare and improve the governance system besides becoming stakeholder responsive.

KEY WORDS

Stakeholder Model

Project Management

Water Resource Management

Governance System

Executive Summary

G C Maheshwari and B Ravi Kumar Pillai

presents articles focusing on managerial

applications of management practices,

theories, and concepts

I N T E R F A C E S

VIKALPA • VOLUME 29 • NO 1 • JANUARY - MARCH 2004 63

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

India has witnessed a dramatic rise in water-related

problems leading to the present crisis with ever

increasing intensity of conflicts amongst various

users of water. Some of the recent conflicts (e.g., water

sharing dispute on river Cauvery) also bring into focus

the manner in which activism by a few people can

complicate the matter to unmanageable proportions.

They also highlight the fact that the nation realizes the

gravity of the crisis only after it reaches a precarious

state. However, this situation could lead to future water

resource development taking up a skewed path where

policy makers and water resource planners of the nation

may tend to ignore the existence of less-vocal and non-

vocal entities. Despite the country’s enormous experi-

ence in developing a good number of large projects,

almost every present-day project is faced with a fire-

fighting situation causing immense time and cost

overruns besides putting considerable pressure on the

national resources. This, to our mind, is due to lack of

a proper framework for understanding the nature and

dimensions of the competing, conflicting, and varied

demands, both by the adversely affected and the ben-

eficiary constituents as a result of the water resource

sector remaining in the control of the government.

At a time when the central government, many state

governments, the apex judiciary, and most of the polit-

ical parties are at the threshold of formulating new

perspectives and taking measures to meet the challenges

posed by the present situation, the totality of the picture,

the attendant issues or even the parties involved are not

clearly known. This calls for identifying various stake-

holders of water resource projects and recognizing their

concerns for and against the projects. It is with this

objective of charting out a balanced and sustainable

water resource development plan for the country that

we attempt to develop in this paper an appropriate

stakeholder model applicable for water resource projects

calling for innovations in the system of governance.

STAKEHOLDERS OF WATER RESOURCE

PROJECTS

It is a paradox that despite the widely accepted social

domain status of water resource development in India,

the ardent supporters of social welfare economics have

only been opposing the water resource projects. It is also

ironical that the critical issues facing the water resource

projects often assume unmanageable proportions be-

cause of the overstated socio-economic objectives.

Though application of tools and philosophies of main-

stream economics is also attempted in selective in-

stances, they mostly go in vain because of an insufficient

understanding of the project intent. This management

dilemma can be overcome only by a clear understanding

of the vital differences amongst stakeholders of water

resource projects and business enterprises.

Who are Stakeholders?

The stakeholders of water resource projects would

include individuals or group of entities who may be

affected by the water resource project during its concep-

tion, construction, and operation and who, in turn, may

also influence the future course of the project. Unlike

business concerns, both social and ecological elements

are always a part of the direct action environment of

water resource projects. Thus, human as well as non-

human entities are called stakeholders of a water re-

source project if the quality of their existence is affected

by the construction and/or operation of the project. Even

non-living entities such as topographical or archaeologi-

cal elements of an affected place can become stakeholders

of the project because of their silent capacity to arouse

human action.

The effect of the project on the quality of existence

of stakeholders may be limited to the dimension of

economic rejuvenation or repression or may have other

dimensions such as affecting stakeholders’ natural habitat

or their social and cultural milieu and, in some cases,

may even jeopardize the very existence of the entities.

While the consequences of the project may be visible on

some entities during or immediately after the com-

mencement of project construction, on others, they may

become visible only after a considerably long time. The

comparative measure of the stakes will also depend

upon varying perceptions of different stakeholders.

However, the degree of return influence may not be in

proportion to the measure of stakes involved owing to

dissimilarity in stakeholders’ capabilities in bringing a

tangible or intangible influence on project activities.

Water as a ‘Social Good’ and ‘Social Investmen

Water is generally considered as a ‘social good’ having

significant spillover benefits or costs (Gleick et al., 2002).

It is essential for life and health and also has cultural

and religious significance especially in India where

rivers are considered sacred. Because of these reasons

and the fact that India is largely dependent on agricul-

64 THE STAKEHOLDER MODEL FOR WATER RESOURCE PROJECTS

problems leading to the present crisis with ever

increasing intensity of conflicts amongst various

users of water. Some of the recent conflicts (e.g., water

sharing dispute on river Cauvery) also bring into focus

the manner in which activism by a few people can

complicate the matter to unmanageable proportions.

They also highlight the fact that the nation realizes the

gravity of the crisis only after it reaches a precarious

state. However, this situation could lead to future water

resource development taking up a skewed path where

policy makers and water resource planners of the nation

may tend to ignore the existence of less-vocal and non-

vocal entities. Despite the country’s enormous experi-

ence in developing a good number of large projects,

almost every present-day project is faced with a fire-

fighting situation causing immense time and cost

overruns besides putting considerable pressure on the

national resources. This, to our mind, is due to lack of

a proper framework for understanding the nature and

dimensions of the competing, conflicting, and varied

demands, both by the adversely affected and the ben-

eficiary constituents as a result of the water resource

sector remaining in the control of the government.

At a time when the central government, many state

governments, the apex judiciary, and most of the polit-

ical parties are at the threshold of formulating new

perspectives and taking measures to meet the challenges

posed by the present situation, the totality of the picture,

the attendant issues or even the parties involved are not

clearly known. This calls for identifying various stake-

holders of water resource projects and recognizing their

concerns for and against the projects. It is with this

objective of charting out a balanced and sustainable

water resource development plan for the country that

we attempt to develop in this paper an appropriate

stakeholder model applicable for water resource projects

calling for innovations in the system of governance.

STAKEHOLDERS OF WATER RESOURCE

PROJECTS

It is a paradox that despite the widely accepted social

domain status of water resource development in India,

the ardent supporters of social welfare economics have

only been opposing the water resource projects. It is also

ironical that the critical issues facing the water resource

projects often assume unmanageable proportions be-

cause of the overstated socio-economic objectives.

Though application of tools and philosophies of main-

stream economics is also attempted in selective in-

stances, they mostly go in vain because of an insufficient

understanding of the project intent. This management

dilemma can be overcome only by a clear understanding

of the vital differences amongst stakeholders of water

resource projects and business enterprises.

Who are Stakeholders?

The stakeholders of water resource projects would

include individuals or group of entities who may be

affected by the water resource project during its concep-

tion, construction, and operation and who, in turn, may

also influence the future course of the project. Unlike

business concerns, both social and ecological elements

are always a part of the direct action environment of

water resource projects. Thus, human as well as non-

human entities are called stakeholders of a water re-

source project if the quality of their existence is affected

by the construction and/or operation of the project. Even

non-living entities such as topographical or archaeologi-

cal elements of an affected place can become stakeholders

of the project because of their silent capacity to arouse

human action.

The effect of the project on the quality of existence

of stakeholders may be limited to the dimension of

economic rejuvenation or repression or may have other

dimensions such as affecting stakeholders’ natural habitat

or their social and cultural milieu and, in some cases,

may even jeopardize the very existence of the entities.

While the consequences of the project may be visible on

some entities during or immediately after the com-

mencement of project construction, on others, they may

become visible only after a considerably long time. The

comparative measure of the stakes will also depend

upon varying perceptions of different stakeholders.

However, the degree of return influence may not be in

proportion to the measure of stakes involved owing to

dissimilarity in stakeholders’ capabilities in bringing a

tangible or intangible influence on project activities.

Water as a ‘Social Good’ and ‘Social Investmen

Water is generally considered as a ‘social good’ having

significant spillover benefits or costs (Gleick et al., 2002).

It is essential for life and health and also has cultural

and religious significance especially in India where

rivers are considered sacred. Because of these reasons

and the fact that India is largely dependent on agricul-

64 THE STAKEHOLDER MODEL FOR WATER RESOURCE PROJECTS

ture for its economic growth, government bodies alone

regulate the water resource projects in India. These

projects are essentially constructed and operated with

the intention of bringing economic and social develop-

ments in certain areas or to a certain set of people rather

than imparting profits to the owners of the projects.

Thus, construction or subsequent operation of water

resource projects cannot be construed as profit-oriented;

rather, it is for maximization of social welfare.

Often, with a view to emphasize efficiency in use

of water, economic tools and principles are applied on

water, but with sub-optimal results. The International

Conference on Water and Environment (1992) held at

Dublin concluded that water has an economic value in

all its competing uses and should be recognized as an

economic good. The application of this concept will

mean that a given amount of water shall be allocated

across competing uses in such a way that the net value

of water resources is maximized. But, this approach

cannot be applied in a mathematical sense because there

are several benefits of water that would defy economic

measurement.Thus, despite the economic elements

being present in water, it may not be fully definable as

an ‘economic good.’ To a limited extent, as in the case

of bottled mineral water — usually consumed by upper

income group people — water may be treated as a

commodity and thus subjected to the market forces.

Also, full or partial privatization of water supply projects

is possible and is even being resorted to in some parts

of the world. But, such efforts are fraught with heavy

risks to both humans and the environment as this can

lead to situations of business people overlooking water

as the basic need for survival of the mankind and

ecosystem. Water may have economic value but it also

has social, cultural, and ecological values that cannot be

entirely realized and taken care of by the market forces.

Water projects are taken up with huge investments

and the natural constraints like topography, geology,

hydrology, etc. may not allow for splitting up of a project

into many smaller investment projects to suit private

participation. Such projects as hitherto envisaged and

implemented in public domain are not always financial-

ly viable and may not be attractive for private sector

participation (Maheshwari and Pillai, 2001). Further,

due to the social and political implications of such

projects, community level efforts are being resorted to

instead of privatization.

Compared to normal business organizations, water

resource projects bring about far more intense social,

economical, and environmental changes and political

pay-offs. These changes, with negative (to some) as well

as positive (to others) consequences, span over much

larger areas and affect a much larger population of

stakeholders. From the human stakeholders’ point of

view, generally, the number of beneficiary stakeholders

surpasses the number of adversely affected stakehold-

ers; however, this assessment of beneficiary and ad-

versely affected stakeholders may not hold good for non-

human stakeholders or for the total stakeholders’ spec-

trum. Compared to commercial organizations, changes

brought about by the water resource projects are long-

lasting and dynamic. The duration of changes may range

from a few years to several decades affecting different

sets of entities at different points of time, and may even

affect the same entities differently at different time

spans. For instance, in the initial years of a construction

project, water may submerge several thousand hectares

of land, affecting a large set of stakeholders (people, flora

and fauna) adversely. Decades later, it may benefit a

larger but different set of stakeholders by providing

them the much needed water. Sometimes, with pro-

longed use of irrigation, the beneficiary areas may get

waterlogged causing adverse affects. The consequences

on the non-living entities such as geology, topology or

atmospheremay vary from small to large at times

causing permanent and irrevocable environmental

changes.

The water resource projects also differ in terms of

strong influences brought about by the stakeholders. In

the case of human and non-human entities, concerns are

voiced by the socially-responsiveand environment-

responsive groups. Moreover, the response of different

sets of people varies considerably over time. Project

oustees who are hyperactive during the construction

stage of the project may cease to be active during its

operational stage, while people at the tail end of the

command area may not show any concern during the

construction or initial stages of the project, but may

become most vocal at the operational stage. Because of

the larger time span and possibilities for change in the

scope of the project, people originally classified as

affected may not actually get affected while others, not

originally in the spectrum of benefits or loss, may

eventually get affected. Time-related attitudinal change

is also possible for other reasons; for instance, the people

adversely affected by submergence of their land may

VIKALPA • VOLUME 29 • NO 1 • JANUARY - MARCH 2004 65

regulate the water resource projects in India. These

projects are essentially constructed and operated with

the intention of bringing economic and social develop-

ments in certain areas or to a certain set of people rather

than imparting profits to the owners of the projects.

Thus, construction or subsequent operation of water

resource projects cannot be construed as profit-oriented;

rather, it is for maximization of social welfare.

Often, with a view to emphasize efficiency in use

of water, economic tools and principles are applied on

water, but with sub-optimal results. The International

Conference on Water and Environment (1992) held at

Dublin concluded that water has an economic value in

all its competing uses and should be recognized as an

economic good. The application of this concept will

mean that a given amount of water shall be allocated

across competing uses in such a way that the net value

of water resources is maximized. But, this approach

cannot be applied in a mathematical sense because there

are several benefits of water that would defy economic

measurement.Thus, despite the economic elements

being present in water, it may not be fully definable as

an ‘economic good.’ To a limited extent, as in the case

of bottled mineral water — usually consumed by upper

income group people — water may be treated as a

commodity and thus subjected to the market forces.

Also, full or partial privatization of water supply projects

is possible and is even being resorted to in some parts

of the world. But, such efforts are fraught with heavy

risks to both humans and the environment as this can

lead to situations of business people overlooking water

as the basic need for survival of the mankind and

ecosystem. Water may have economic value but it also

has social, cultural, and ecological values that cannot be

entirely realized and taken care of by the market forces.

Water projects are taken up with huge investments

and the natural constraints like topography, geology,

hydrology, etc. may not allow for splitting up of a project

into many smaller investment projects to suit private

participation. Such projects as hitherto envisaged and

implemented in public domain are not always financial-

ly viable and may not be attractive for private sector

participation (Maheshwari and Pillai, 2001). Further,

due to the social and political implications of such

projects, community level efforts are being resorted to

instead of privatization.

Compared to normal business organizations, water

resource projects bring about far more intense social,

economical, and environmental changes and political

pay-offs. These changes, with negative (to some) as well

as positive (to others) consequences, span over much

larger areas and affect a much larger population of

stakeholders. From the human stakeholders’ point of

view, generally, the number of beneficiary stakeholders

surpasses the number of adversely affected stakehold-

ers; however, this assessment of beneficiary and ad-

versely affected stakeholders may not hold good for non-

human stakeholders or for the total stakeholders’ spec-

trum. Compared to commercial organizations, changes

brought about by the water resource projects are long-

lasting and dynamic. The duration of changes may range

from a few years to several decades affecting different

sets of entities at different points of time, and may even

affect the same entities differently at different time

spans. For instance, in the initial years of a construction

project, water may submerge several thousand hectares

of land, affecting a large set of stakeholders (people, flora

and fauna) adversely. Decades later, it may benefit a

larger but different set of stakeholders by providing

them the much needed water. Sometimes, with pro-

longed use of irrigation, the beneficiary areas may get

waterlogged causing adverse affects. The consequences

on the non-living entities such as geology, topology or

atmospheremay vary from small to large at times

causing permanent and irrevocable environmental

changes.

The water resource projects also differ in terms of

strong influences brought about by the stakeholders. In

the case of human and non-human entities, concerns are

voiced by the socially-responsiveand environment-

responsive groups. Moreover, the response of different

sets of people varies considerably over time. Project

oustees who are hyperactive during the construction

stage of the project may cease to be active during its

operational stage, while people at the tail end of the

command area may not show any concern during the

construction or initial stages of the project, but may

become most vocal at the operational stage. Because of

the larger time span and possibilities for change in the

scope of the project, people originally classified as

affected may not actually get affected while others, not

originally in the spectrum of benefits or loss, may

eventually get affected. Time-related attitudinal change

is also possible for other reasons; for instance, the people

adversely affected by submergence of their land may

VIKALPA • VOLUME 29 • NO 1 • JANUARY - MARCH 2004 65

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

later get rehabilitated in the command area of the project

thereby making them beneficiaries of the project.

The business enterprisesare, to a large extent,

shielded against direct public or political pressures. The

roles of external stakeholders are generally demanding

in nature while the management plays a reactive role

after a careful examination of the stakeholders’ demands

vis-à-vis organization’s immediate objectives and long-

term mission. In contrast to this, the management of a

water resource project is open to direct public influence

— generally brought through a capricious political

response for want of clientele effect — allowing for

prejudicial dilution of project objectives and mission.

Since a large number of people are affected by even small

scale changes in the scope of such projects, the political

forces play a vital role in influencing decisions related

to them. These decisions have significant financial and

economic outcomes and heighten the role played by

politically active interest groups, exacerbated by the

media to a much larger proportion.

THE STAKEHOLDER MODEL

It is against this background that we attempt to develop

a proper model that will permit identification, classifi-

cation, and understanding of the whole spectrum of

stakeholders and imparting efficacy to the management

system.

IdentifyingStakeholders

The stakeholders of business concerns are identified

under two broad categories, viz., internal and external,

because of the highly competitive environment in which

internal stakeholders present a monolith front to counter

the challenges posed by numerous divergent external

stakeholders. But, this approach is highly unsuitable for

identifying stakeholders of water resource projects for

the reason that the internal stakeholders are generally

a part of the government (as policy makers, planners or

project executors) and their existence is not critically

linked with the success of the project. A plethora of

departments and ministries may not present a monolith

front (especially in case of multi-state projects) for

reasons of well established principles of accountability

and thus the notion of internal stakeholders may not be

as crucial as in the case of business organizations.

Moreover, identifying the large and influential segment

of the external environment as mere external stakeholders

may reduce the significance of some of the diverse, but

consequential, stakeholder groups.

What are the other ways of identifying the stake-

holders of water resource projects? One of the approach-

es could be the biological and physical differentiation

of stakeholders along the lines of living and non-living,

human and non-human, urban and rural, etc. Another

approach could be in terms of project outcomes on the

stakeholders with economic, social, cultural or environ-

mental dimensions. Yet another approach is possible

according to the timing of impact (i.e. immediate or

later), extent of impact (severe vs. marginal), or the

stakeholders’capacity to voice response to changes

caused by the project. As no single approach for iden-

tifying the stakeholders of water resource projects is

capable of permitting full understanding of the various

issues of project construction and operation, we propose

a three-tier approach.

Stakeholders may be identified as beneficiaries and

adversely affected groups. This division, though com-

prehensive in terms of the nature of project’s effect on

stakeholders is too broad and leaves out the inherent

characteristicsof stakeholdersand their capacity to

respond to the project effects. Hence, this needs further

sub-classification as social and non-social groups de-

pending upon the presence or absence of social relation-

ship between stakeholders and the project. People af-

fected by the project are social stakeholders because

their interests are linked with the project through social

interaction;on the other hand, the affected natural

elements, non-human species, and the future human

generation — unable to forge social relationship with

the project — are examples of non-social stakeholders

(Wheeler and Sillanpaa, 1997). Thus, the second tier of

identification process leads to classification of stake-

holders as:

social beneficiary group

non-social beneficiary group

social adversely affected group

non-social adversely affected group.

So far, the identification has been confined to

stakeholders who are directly affected by the project.

Project effects on indirect stakeholders arise due to their

proximity — resulting from social, environmental or

economic ties — with the directly affected groups and

they also bring influences on the project. The directly

and indirectly affected stakeholders are classified as

primary and secondary sub-groups respectively. The

third tier of identification process, thus, leads to an eight-

66 THE STAKEHOLDER MODEL FOR WATER RESOURCE PROJECTS

thereby making them beneficiaries of the project.

The business enterprisesare, to a large extent,

shielded against direct public or political pressures. The

roles of external stakeholders are generally demanding

in nature while the management plays a reactive role

after a careful examination of the stakeholders’ demands

vis-à-vis organization’s immediate objectives and long-

term mission. In contrast to this, the management of a

water resource project is open to direct public influence

— generally brought through a capricious political

response for want of clientele effect — allowing for

prejudicial dilution of project objectives and mission.

Since a large number of people are affected by even small

scale changes in the scope of such projects, the political

forces play a vital role in influencing decisions related

to them. These decisions have significant financial and

economic outcomes and heighten the role played by

politically active interest groups, exacerbated by the

media to a much larger proportion.

THE STAKEHOLDER MODEL

It is against this background that we attempt to develop

a proper model that will permit identification, classifi-

cation, and understanding of the whole spectrum of

stakeholders and imparting efficacy to the management

system.

IdentifyingStakeholders

The stakeholders of business concerns are identified

under two broad categories, viz., internal and external,

because of the highly competitive environment in which

internal stakeholders present a monolith front to counter

the challenges posed by numerous divergent external

stakeholders. But, this approach is highly unsuitable for

identifying stakeholders of water resource projects for

the reason that the internal stakeholders are generally

a part of the government (as policy makers, planners or

project executors) and their existence is not critically

linked with the success of the project. A plethora of

departments and ministries may not present a monolith

front (especially in case of multi-state projects) for

reasons of well established principles of accountability

and thus the notion of internal stakeholders may not be

as crucial as in the case of business organizations.

Moreover, identifying the large and influential segment

of the external environment as mere external stakeholders

may reduce the significance of some of the diverse, but

consequential, stakeholder groups.

What are the other ways of identifying the stake-

holders of water resource projects? One of the approach-

es could be the biological and physical differentiation

of stakeholders along the lines of living and non-living,

human and non-human, urban and rural, etc. Another

approach could be in terms of project outcomes on the

stakeholders with economic, social, cultural or environ-

mental dimensions. Yet another approach is possible

according to the timing of impact (i.e. immediate or

later), extent of impact (severe vs. marginal), or the

stakeholders’capacity to voice response to changes

caused by the project. As no single approach for iden-

tifying the stakeholders of water resource projects is

capable of permitting full understanding of the various

issues of project construction and operation, we propose

a three-tier approach.

Stakeholders may be identified as beneficiaries and

adversely affected groups. This division, though com-

prehensive in terms of the nature of project’s effect on

stakeholders is too broad and leaves out the inherent

characteristicsof stakeholdersand their capacity to

respond to the project effects. Hence, this needs further

sub-classification as social and non-social groups de-

pending upon the presence or absence of social relation-

ship between stakeholders and the project. People af-

fected by the project are social stakeholders because

their interests are linked with the project through social

interaction;on the other hand, the affected natural

elements, non-human species, and the future human

generation — unable to forge social relationship with

the project — are examples of non-social stakeholders

(Wheeler and Sillanpaa, 1997). Thus, the second tier of

identification process leads to classification of stake-

holders as:

social beneficiary group

non-social beneficiary group

social adversely affected group

non-social adversely affected group.

So far, the identification has been confined to

stakeholders who are directly affected by the project.

Project effects on indirect stakeholders arise due to their

proximity — resulting from social, environmental or

economic ties — with the directly affected groups and

they also bring influences on the project. The directly

and indirectly affected stakeholders are classified as

primary and secondary sub-groups respectively. The

third tier of identification process, thus, leads to an eight-

66 THE STAKEHOLDER MODEL FOR WATER RESOURCE PROJECTS

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

fold classification of stakeholders as follows:

• primary social beneficiary group

• secondary social beneficiary group

• primary non-social beneficiary group

• secondary non-social beneficiary group

• primary social adversely affected group

• secondary social adversely affected group

• primary non-social adversely affected group

• secondary non-social adversely affected group.

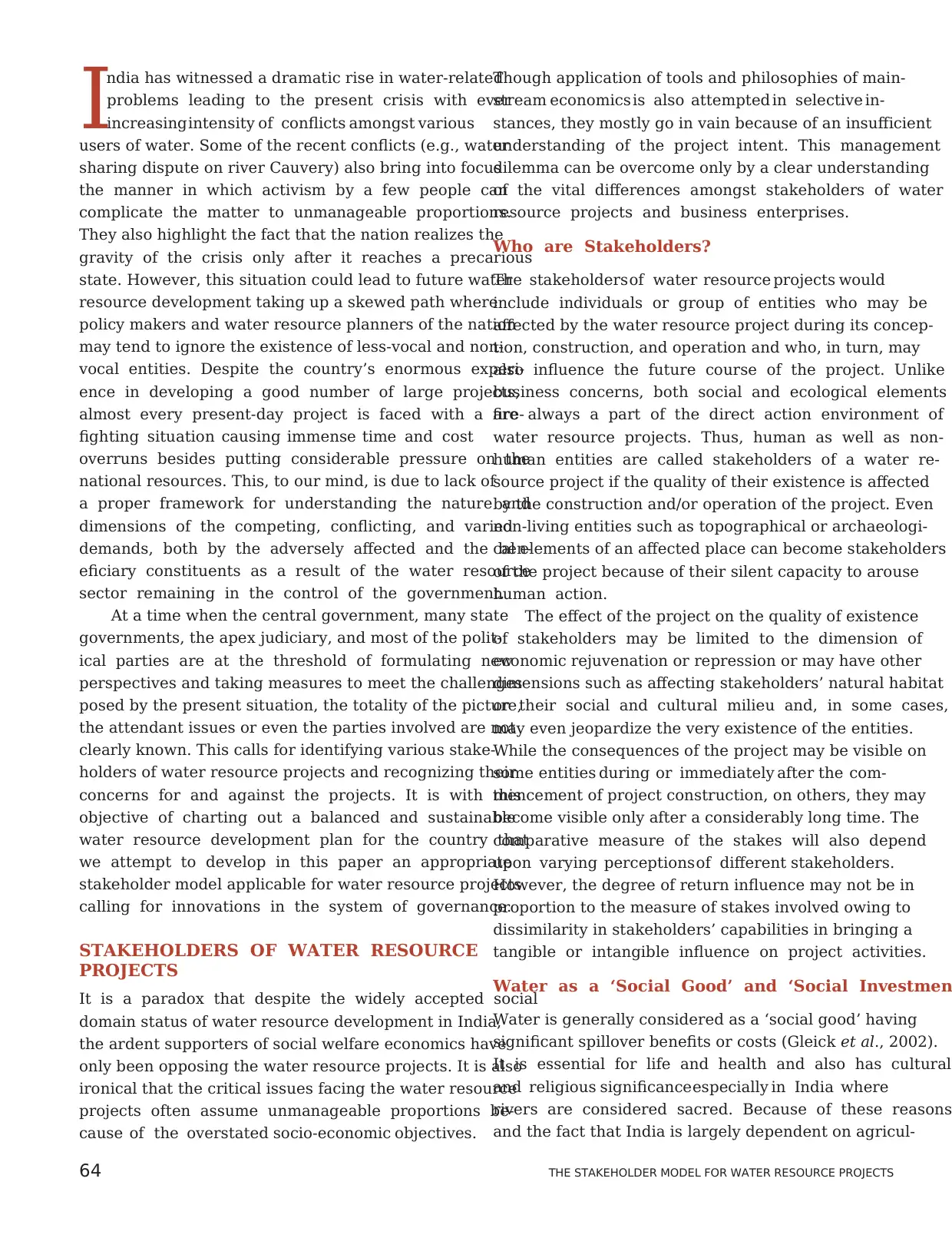

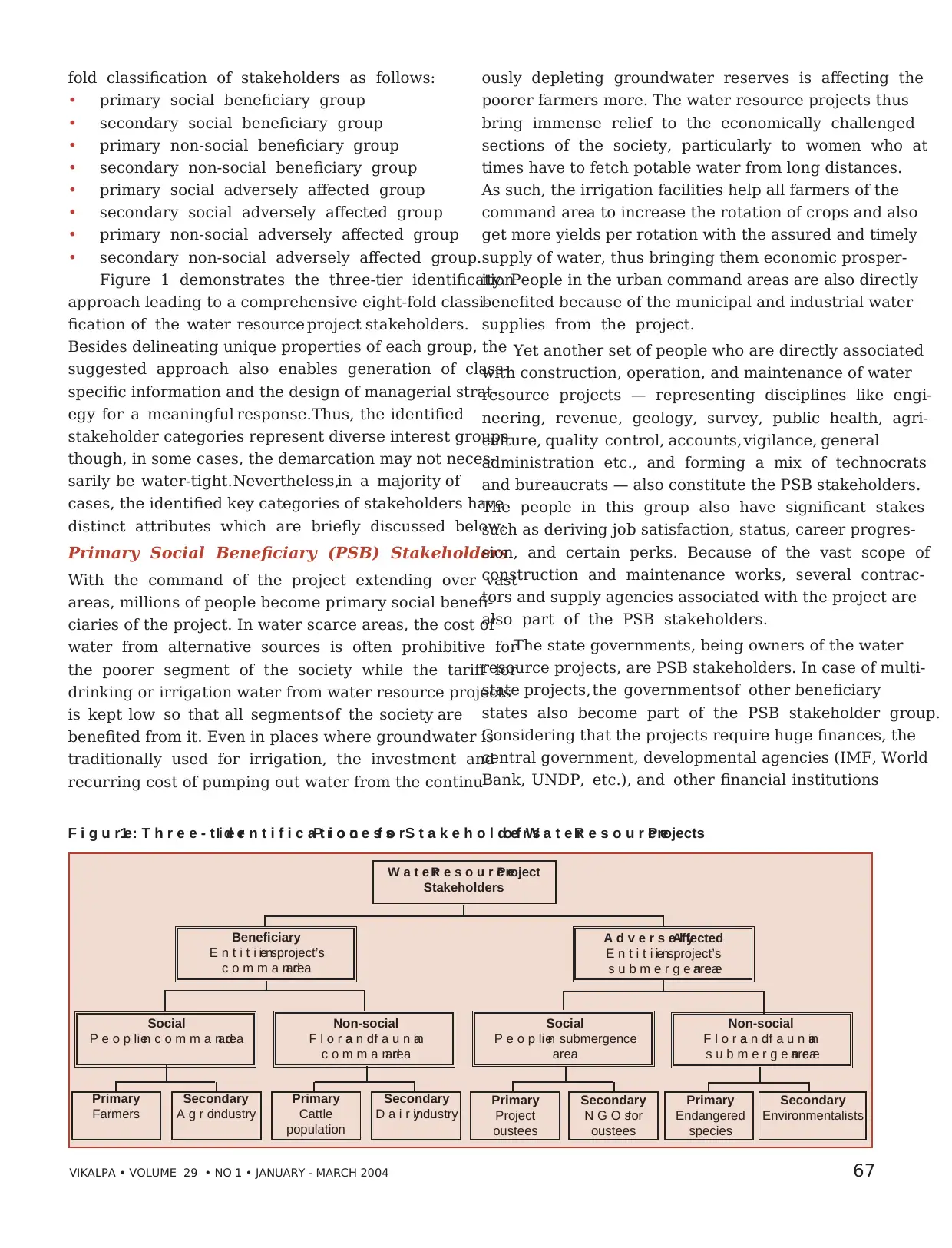

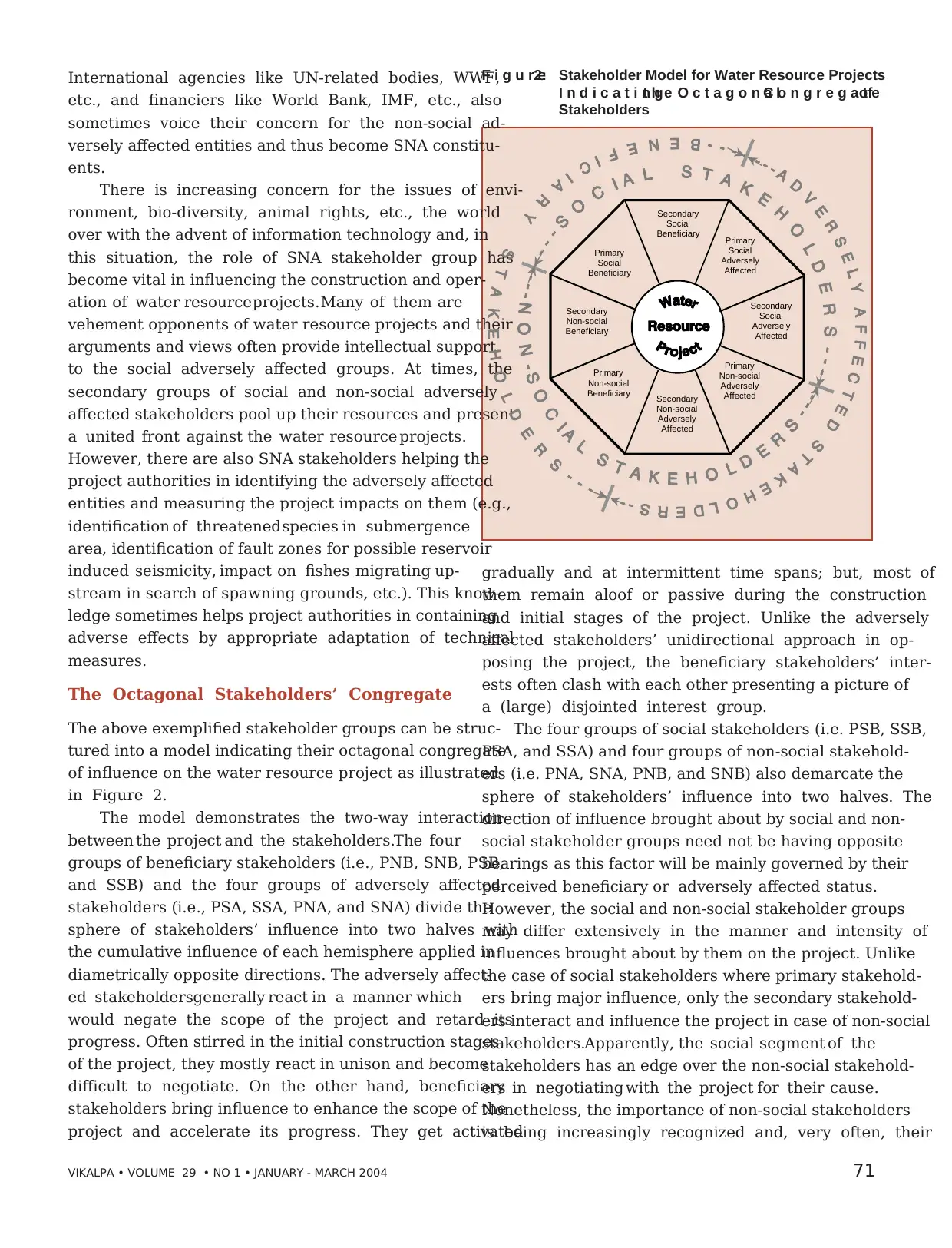

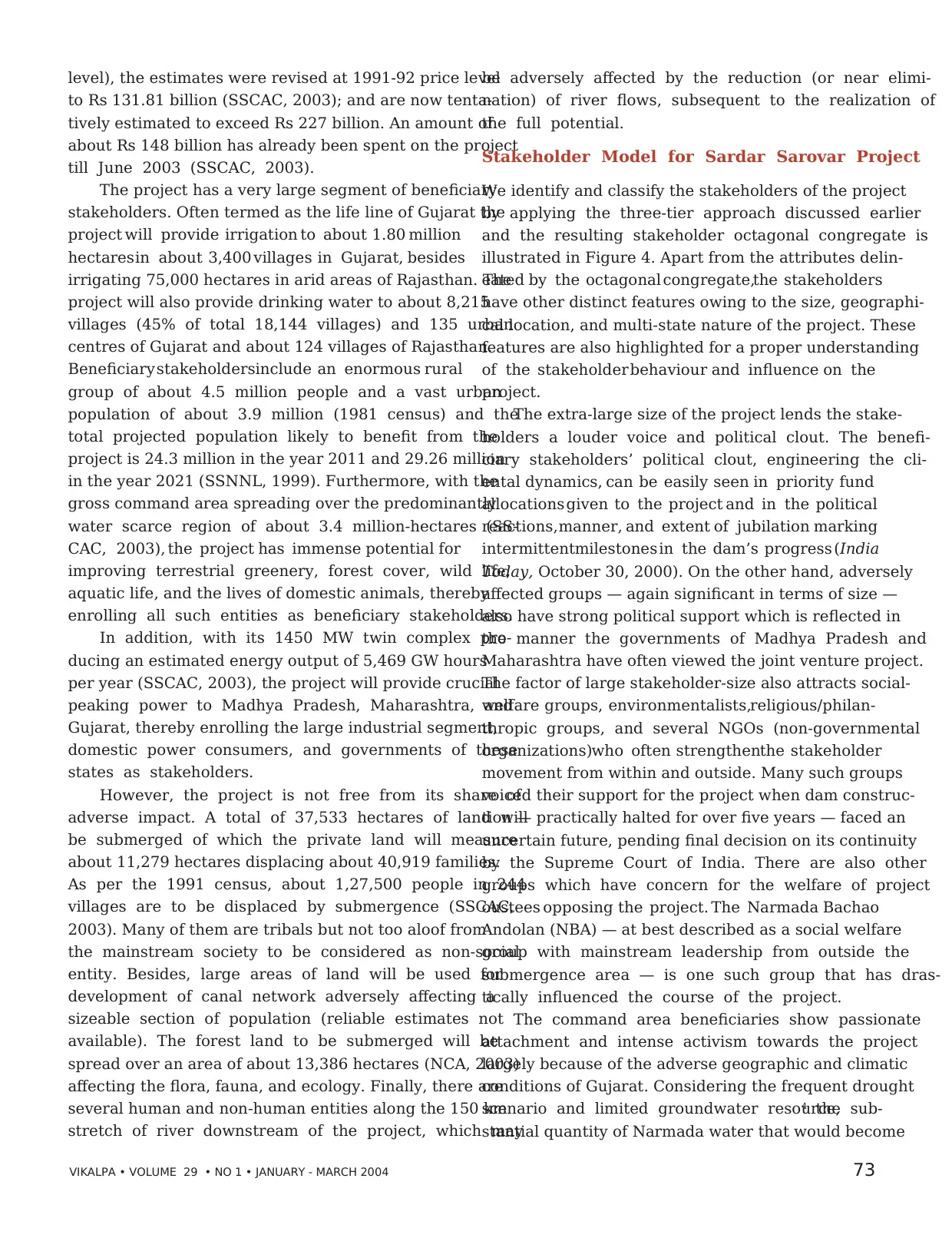

Figure 1 demonstrates the three-tier identification

approach leading to a comprehensive eight-fold classi-

fication of the water resource project stakeholders.

Besides delineating unique properties of each group, the

suggested approach also enables generation of class-

specific information and the design of managerial strat-

egy for a meaningful response.Thus, the identified

stakeholder categories represent diverse interest groups

though, in some cases, the demarcation may not neces-

sarily be water-tight. Nevertheless,in a majority of

cases, the identified key categories of stakeholders have

distinct attributes which are briefly discussed below:

Primary Social Beneficiary (PSB) Stakeholders

With the command of the project extending over vast

areas, millions of people become primary social benefi-

ciaries of the project. In water scarce areas, the cost of

water from alternative sources is often prohibitive for

the poorer segment of the society while the tariff for

drinking or irrigation water from water resource projects

is kept low so that all segments of the society are

benefited from it. Even in places where groundwater is

traditionally used for irrigation, the investment and

recurring cost of pumping out water from the continu-

ously depleting groundwater reserves is affecting the

poorer farmers more. The water resource projects thus

bring immense relief to the economically challenged

sections of the society, particularly to women who at

times have to fetch potable water from long distances.

As such, the irrigation facilities help all farmers of the

command area to increase the rotation of crops and also

get more yields per rotation with the assured and timely

supply of water, thus bringing them economic prosper-

ity. People in the urban command areas are also directly

benefited because of the municipal and industrial water

supplies from the project.

Yet another set of people who are directly associated

with construction, operation, and maintenance of water

resource projects — representing disciplines like engi-

neering, revenue, geology, survey, public health, agri-

culture, quality control, accounts, vigilance, general

administration etc., and forming a mix of technocrats

and bureaucrats — also constitute the PSB stakeholders.

The people in this group also have significant stakes

such as deriving job satisfaction, status, career progres-

sion, and certain perks. Because of the vast scope of

construction and maintenance works, several contrac-

tors and supply agencies associated with the project are

also part of the PSB stakeholders.

The state governments, being owners of the water

resource projects, are PSB stakeholders. In case of multi-

state projects, the governments of other beneficiary

states also become part of the PSB stakeholder group.

Considering that the projects require huge finances, the

central government, developmental agencies (IMF, World

Bank, UNDP, etc.), and other financial institutions

F i g u r e1 : T h r e e - t i e rI d e n t i f i c a t i o nP r o c e s sf o rS t a k e h o l d e r so f W a t e rR e s o u r c eProjects

W a t e rR e s o u r c eProject

Stakeholders

Beneficiary

E n t i t i e si n project’s

c o m m a n darea

A d v e r s e l yAffected

E n t i t i e si n project’s

s u b m e r g e n c earea

Social

P e o p l ei n c o m m a n darea

Non-social

F l o r aa n df a u n ain

c o m m a n darea

Social

P e o p l ei n submergence

area

Non-social

F l o r aa n df a u n ain

s u b m e r g e n c earea

Primary

Farmers

Secondary

A g r oindustry

Primary

Cattle

population

Secondary

D a i r yindustry

Primary

Project

oustees

Secondary

N G O sfor

oustees

Primary

Endangered

species

Secondary

Environmentalists

VIKALPA • VOLUME 29 • NO 1 • JANUARY - MARCH 2004 67

• primary social beneficiary group

• secondary social beneficiary group

• primary non-social beneficiary group

• secondary non-social beneficiary group

• primary social adversely affected group

• secondary social adversely affected group

• primary non-social adversely affected group

• secondary non-social adversely affected group.

Figure 1 demonstrates the three-tier identification

approach leading to a comprehensive eight-fold classi-

fication of the water resource project stakeholders.

Besides delineating unique properties of each group, the

suggested approach also enables generation of class-

specific information and the design of managerial strat-

egy for a meaningful response.Thus, the identified

stakeholder categories represent diverse interest groups

though, in some cases, the demarcation may not neces-

sarily be water-tight. Nevertheless,in a majority of

cases, the identified key categories of stakeholders have

distinct attributes which are briefly discussed below:

Primary Social Beneficiary (PSB) Stakeholders

With the command of the project extending over vast

areas, millions of people become primary social benefi-

ciaries of the project. In water scarce areas, the cost of

water from alternative sources is often prohibitive for

the poorer segment of the society while the tariff for

drinking or irrigation water from water resource projects

is kept low so that all segments of the society are

benefited from it. Even in places where groundwater is

traditionally used for irrigation, the investment and

recurring cost of pumping out water from the continu-

ously depleting groundwater reserves is affecting the

poorer farmers more. The water resource projects thus

bring immense relief to the economically challenged

sections of the society, particularly to women who at

times have to fetch potable water from long distances.

As such, the irrigation facilities help all farmers of the

command area to increase the rotation of crops and also

get more yields per rotation with the assured and timely

supply of water, thus bringing them economic prosper-

ity. People in the urban command areas are also directly

benefited because of the municipal and industrial water

supplies from the project.

Yet another set of people who are directly associated

with construction, operation, and maintenance of water

resource projects — representing disciplines like engi-

neering, revenue, geology, survey, public health, agri-

culture, quality control, accounts, vigilance, general

administration etc., and forming a mix of technocrats

and bureaucrats — also constitute the PSB stakeholders.

The people in this group also have significant stakes

such as deriving job satisfaction, status, career progres-

sion, and certain perks. Because of the vast scope of

construction and maintenance works, several contrac-

tors and supply agencies associated with the project are

also part of the PSB stakeholders.

The state governments, being owners of the water

resource projects, are PSB stakeholders. In case of multi-

state projects, the governments of other beneficiary

states also become part of the PSB stakeholder group.

Considering that the projects require huge finances, the

central government, developmental agencies (IMF, World

Bank, UNDP, etc.), and other financial institutions

F i g u r e1 : T h r e e - t i e rI d e n t i f i c a t i o nP r o c e s sf o rS t a k e h o l d e r so f W a t e rR e s o u r c eProjects

W a t e rR e s o u r c eProject

Stakeholders

Beneficiary

E n t i t i e si n project’s

c o m m a n darea

A d v e r s e l yAffected

E n t i t i e si n project’s

s u b m e r g e n c earea

Social

P e o p l ei n c o m m a n darea

Non-social

F l o r aa n df a u n ain

c o m m a n darea

Social

P e o p l ei n submergence

area

Non-social

F l o r aa n df a u n ain

s u b m e r g e n c earea

Primary

Farmers

Secondary

A g r oindustry

Primary

Cattle

population

Secondary

D a i r yindustry

Primary

Project

oustees

Secondary

N G O sfor

oustees

Primary

Endangered

species

Secondary

Environmentalists

VIKALPA • VOLUME 29 • NO 1 • JANUARY - MARCH 2004 67

(ICICI, IDBI, etc.), which agree to provide or help raise

funds, also form a part of the PSB stakeholders’ group.

Secondary Social Beneficiary (SSB) Stakeholders

People who are indirectly concerned with the benefits

of construction and operation of the water resource

projects belong to the SSB stakeholder class. Agricul-

tural growth also spurs economic prosperity of farm

labourers, craftsmen, and traders, besides encouraging

agro-product industries in the command area of the

project. Growth of cities in the command area and

commercial activities like tourism also flourish with the

development of water resource projects. Such projects

usually come up in remote and economically backward

regions and thus give tremendous boost to the infra-

structure development of that area bringing large-scale

economic development.

Being large-scale infrastructure projects involving

heavy investment, they have huge capacities to generate

demand for construction material (cement, steel, chem-

icals etc.), equipment (excavators, bulldozers, hoists,

cranes, concrete mixers, pavers, generators,pumps,

drilling equipment etc.), fabricators, bankers, consult-

ants, designers, and other support services. Because of

the projects’ potential to give employment to millions

of people and opportunities to thousands of entrepre-

neurs, people affiliated to labour unions and political

parties (with capacity to influence manpower recruit-

ment and works/supply contracts) also get interested

in these projects. Since technology and equipment are

often imported from the developed countries, the gov-

ernments of such countries also take interest in these

projects. All these entities constitute the group of SSB

stakeholders.

Generally, infrastructure projects positively impact

a nation’s economic growth which is indicated by the

quantitative economic change, usually measured as

increase in per capita income or output. Investment in

water resource projects is intended not only for present

consumption but also for production of other goods

through agriculture (e.g. food and non-food crops and

several agro-products)and power (whole industrial

sector), and hence is a factor of output growth. Since

progress in the agricultural sector is a pre-condition for

stimulating growth in the modern sector1 in developing

countries, the water resource projects play a vital role

in the economic development of India. Thus, the central

government, its numerous ministries, departments,

institutions, and the Planning Commission which advo-

cate the cause of water resource projects form a part of

SSB shareholders. Similarly, the NGOs working for the

upliftment of rural populace, social and cultural welfare

societies, agricultural and dairy promotional agencies,

public health departments, and the national level indus-

trial and trade bodies, etc. who express their concern for

the successful completion and operation of the water

resource projects fall under the same category.

Primary Non-social Beneficiary (PNB) Stakeholde

The ecology of the area that is fed with water from the

projects gets immensely benefited. The irrigation water

not only brings greenery to the farmers’ fields but also

enhances the vegetation cover over the whole terrain.

As is seen from past experiences (e.g., Indira Gandhi

Canal Project in Rajasthan), most of the time, the projects

turn an otherwise barren land into a land full of crops,

cattle fodder, and fruit-bearing and woody trees. Besides

flora, irrigation projects also benefit the fauna in com-

mand areas. Many kinds of insects, reptiles, and birds

not only enjoy a conducive environment but also con-

tribute towards development of food chain which is

basic for their natural existence. Cattle population, wild

life, and bird sanctuaries are benefited by the newly

augmented supply of water and fodder in the command

areas. All such entities of the command area constitute

the PNB stakeholder group. With accruing benefits, the

economic and social life styles of people in the command

areas may go through a sea change which, in turn, in-

fluence the lives of their children as well; thus, the future

generation of command areas is also a part of PNB

stakeholders.

Since command areas extend from a few thousand

hectares to a few million hectares, the increase in green

cover of such vast areas improves the ambient condi-

tions and local rainfall pattern, besides contributing to

reduction in global warming. There are some positive

effects on the river ecology also such as reduction in

frequency and intensity of floods leading to relief from

recurring wash-out of fertile soil and vegetation cover

of downstream flood planes. By tapping significant

amounts of river silt, the projects also help in providing

cleaner water to the downstream reaches of the project.

The abundance of water for most part of the year may

help the growth of forest cover and wild life along the

reservoir fringes and also help in growth of aquatic lives

in project reservoir. All such entities outside the com-

mand area may also constitute the PNB stakeholder

group.

68 THE STAKEHOLDER MODEL FOR WATER RESOURCE PROJECTS

funds, also form a part of the PSB stakeholders’ group.

Secondary Social Beneficiary (SSB) Stakeholders

People who are indirectly concerned with the benefits

of construction and operation of the water resource

projects belong to the SSB stakeholder class. Agricul-

tural growth also spurs economic prosperity of farm

labourers, craftsmen, and traders, besides encouraging

agro-product industries in the command area of the

project. Growth of cities in the command area and

commercial activities like tourism also flourish with the

development of water resource projects. Such projects

usually come up in remote and economically backward

regions and thus give tremendous boost to the infra-

structure development of that area bringing large-scale

economic development.

Being large-scale infrastructure projects involving

heavy investment, they have huge capacities to generate

demand for construction material (cement, steel, chem-

icals etc.), equipment (excavators, bulldozers, hoists,

cranes, concrete mixers, pavers, generators,pumps,

drilling equipment etc.), fabricators, bankers, consult-

ants, designers, and other support services. Because of

the projects’ potential to give employment to millions

of people and opportunities to thousands of entrepre-

neurs, people affiliated to labour unions and political

parties (with capacity to influence manpower recruit-

ment and works/supply contracts) also get interested

in these projects. Since technology and equipment are

often imported from the developed countries, the gov-

ernments of such countries also take interest in these

projects. All these entities constitute the group of SSB

stakeholders.

Generally, infrastructure projects positively impact

a nation’s economic growth which is indicated by the

quantitative economic change, usually measured as

increase in per capita income or output. Investment in

water resource projects is intended not only for present

consumption but also for production of other goods

through agriculture (e.g. food and non-food crops and

several agro-products)and power (whole industrial

sector), and hence is a factor of output growth. Since

progress in the agricultural sector is a pre-condition for

stimulating growth in the modern sector1 in developing

countries, the water resource projects play a vital role

in the economic development of India. Thus, the central

government, its numerous ministries, departments,

institutions, and the Planning Commission which advo-

cate the cause of water resource projects form a part of

SSB shareholders. Similarly, the NGOs working for the

upliftment of rural populace, social and cultural welfare

societies, agricultural and dairy promotional agencies,

public health departments, and the national level indus-

trial and trade bodies, etc. who express their concern for

the successful completion and operation of the water

resource projects fall under the same category.

Primary Non-social Beneficiary (PNB) Stakeholde

The ecology of the area that is fed with water from the

projects gets immensely benefited. The irrigation water

not only brings greenery to the farmers’ fields but also

enhances the vegetation cover over the whole terrain.

As is seen from past experiences (e.g., Indira Gandhi

Canal Project in Rajasthan), most of the time, the projects

turn an otherwise barren land into a land full of crops,

cattle fodder, and fruit-bearing and woody trees. Besides

flora, irrigation projects also benefit the fauna in com-

mand areas. Many kinds of insects, reptiles, and birds

not only enjoy a conducive environment but also con-

tribute towards development of food chain which is

basic for their natural existence. Cattle population, wild

life, and bird sanctuaries are benefited by the newly

augmented supply of water and fodder in the command

areas. All such entities of the command area constitute

the PNB stakeholder group. With accruing benefits, the

economic and social life styles of people in the command

areas may go through a sea change which, in turn, in-

fluence the lives of their children as well; thus, the future

generation of command areas is also a part of PNB

stakeholders.

Since command areas extend from a few thousand

hectares to a few million hectares, the increase in green

cover of such vast areas improves the ambient condi-

tions and local rainfall pattern, besides contributing to

reduction in global warming. There are some positive

effects on the river ecology also such as reduction in

frequency and intensity of floods leading to relief from

recurring wash-out of fertile soil and vegetation cover

of downstream flood planes. By tapping significant

amounts of river silt, the projects also help in providing

cleaner water to the downstream reaches of the project.

The abundance of water for most part of the year may

help the growth of forest cover and wild life along the

reservoir fringes and also help in growth of aquatic lives

in project reservoir. All such entities outside the com-

mand area may also constitute the PNB stakeholder

group.

68 THE STAKEHOLDER MODEL FOR WATER RESOURCE PROJECTS

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Secondary Non-social Beneficiary (SNB)

Stakeholders

Because of the improvement in the conditions of cattle

population, the dairies and affiliated industries in com-

mand areas get immensely benefited thereby making

them SNB stakeholders. Besides, the organizations re-

sponsible for the compensatory afforestation programmes

of the project, along with those associated with reserve

forests, wild life sanctuaries, bird sanctuaries, etc. in the

command areas, also constitute the SNB stakeholder

group. Though the state government responsible for

formulation of water resource projects generally takes

into account the ecological and environmental benefits

of the projects, yet many of the central government

agencies, non-governmental organizations, and some-

times institutional financiers, also exert influence to

enhance project benefits to the non-social entities. All

such entities also fall under the SNB stakeholder class.

Primary Social Adversely Affected (PSA)

Stakeholders

Spread over vast geographical areas, the people dis-

placed by project submergence are the main constituents

of the PSA stakeholders. Being affected at a very early

stage of the project, they try their best to stall the project

and often succeed as well. Statistically, rural areas seem

to be more prone though instances of urban and semi-

urban areas coming under reservoir submergence are

also not uncommon.

Sometimes, the entire area is submerged leading to

large-scale displacement of people, generally to distant

locations. In such a case, the social fabric of the village

may be recreated with careful planning and execution.

Alternatively, only a part of the village may get affected

but it may be possible to accommodate displaced people

within the vicinity of that village. However, the most

common case is that of partly affected villages where

affected people are resettled in far-off places due to non-

availability of sufficient land; and, in such situations, the

social balance of villages gets disturbed threatening

their sustainability. From an economic viewpoint, some

of the project affected people may lose their entire

agricultural land and also their dwellings; some may

lose only the land or part of it but not the house; some

may lose only house but not the land. Those who are

affected significantly have no option against displace-

ment but they retain or even surpass their earlier social

and economic status, if properly compensated. Ironical-

ly, marginally affected people may not like to leave their

native place but may suffer long-term economic losses

and fall in social status despite reasonable cash compen-

sation for the lost land. Sometimes, people get affected

adversely even without losing land properties, as may

happen in the cases of landless farm labourers, boatmen,

traditional craftsmen, carpenters,blacksmiths, shoe-

makers, tailors, etc, whose means of livelihood get

affected due to large scale displacement of village

population. For large scale resettlement of project ous-

tees, the government is often required to procure land

from villages which are otherwise unaffected by the

project. This may create a secondary layer of displaced

people. Sometimes, a portion of the forest land or other

state-owned land is utilized for resettlementof the

project affected people thereby adversely affecting

another set of people who are dependent on the forest

produce or have encroached on the government land for

cultivation. All these people constitute the PSA stake-

holder group.

With commencement of project operations, fisher-

men along the downstream river stretch may get ad-

versely affected due to reduction in stream flows. The

farmers along the downstream river banks may also get

affected due to shortage of irrigation water. The econ-

omy of religious and tourist places along the down-

stream river banks may also get affected as these places

lose eminence due to degradation of the river. Industries

in the vicinity of rivers too get affected due to reduction

in stream flows leading to river pollution affecting

people along the downstream river stretches. All such

adversely affected people are also categorized as PSA

stakeholders.

Secondary Social Adversely Affected (SSA)

Stakeholders

The SSA stakeholders are indirectly concerned with the

adverse consequences of the project. This group may

include people who are emotionally aggrieved by the

displacement of near and dear ones, though they are

themselves not displaced. Similarly, in the case of

partially affected villages, the people left out from

displacement may suffer social, cultural, and economic

deprivation, and not being treated as project affected,

may not get compensated for the loss.

The SSA stakeholders also include individuals or

organizations who themselves are not affected but voice

concern for those subjected to large scale displacement

and hardships. They unite the segmented group of

oustees who are not only dispersed but belong to diverse

VIKALPA • VOLUME 29 • NO 1 • JANUARY - MARCH 2004 69

Stakeholders

Because of the improvement in the conditions of cattle

population, the dairies and affiliated industries in com-

mand areas get immensely benefited thereby making

them SNB stakeholders. Besides, the organizations re-

sponsible for the compensatory afforestation programmes

of the project, along with those associated with reserve

forests, wild life sanctuaries, bird sanctuaries, etc. in the

command areas, also constitute the SNB stakeholder

group. Though the state government responsible for

formulation of water resource projects generally takes

into account the ecological and environmental benefits

of the projects, yet many of the central government

agencies, non-governmental organizations, and some-

times institutional financiers, also exert influence to

enhance project benefits to the non-social entities. All

such entities also fall under the SNB stakeholder class.

Primary Social Adversely Affected (PSA)

Stakeholders

Spread over vast geographical areas, the people dis-

placed by project submergence are the main constituents

of the PSA stakeholders. Being affected at a very early

stage of the project, they try their best to stall the project

and often succeed as well. Statistically, rural areas seem

to be more prone though instances of urban and semi-

urban areas coming under reservoir submergence are

also not uncommon.

Sometimes, the entire area is submerged leading to

large-scale displacement of people, generally to distant

locations. In such a case, the social fabric of the village

may be recreated with careful planning and execution.

Alternatively, only a part of the village may get affected

but it may be possible to accommodate displaced people

within the vicinity of that village. However, the most

common case is that of partly affected villages where

affected people are resettled in far-off places due to non-

availability of sufficient land; and, in such situations, the

social balance of villages gets disturbed threatening

their sustainability. From an economic viewpoint, some

of the project affected people may lose their entire

agricultural land and also their dwellings; some may

lose only the land or part of it but not the house; some

may lose only house but not the land. Those who are

affected significantly have no option against displace-

ment but they retain or even surpass their earlier social

and economic status, if properly compensated. Ironical-

ly, marginally affected people may not like to leave their

native place but may suffer long-term economic losses

and fall in social status despite reasonable cash compen-

sation for the lost land. Sometimes, people get affected

adversely even without losing land properties, as may

happen in the cases of landless farm labourers, boatmen,

traditional craftsmen, carpenters,blacksmiths, shoe-

makers, tailors, etc, whose means of livelihood get

affected due to large scale displacement of village

population. For large scale resettlement of project ous-

tees, the government is often required to procure land

from villages which are otherwise unaffected by the

project. This may create a secondary layer of displaced

people. Sometimes, a portion of the forest land or other

state-owned land is utilized for resettlementof the

project affected people thereby adversely affecting

another set of people who are dependent on the forest

produce or have encroached on the government land for

cultivation. All these people constitute the PSA stake-

holder group.

With commencement of project operations, fisher-

men along the downstream river stretch may get ad-

versely affected due to reduction in stream flows. The

farmers along the downstream river banks may also get

affected due to shortage of irrigation water. The econ-

omy of religious and tourist places along the down-

stream river banks may also get affected as these places

lose eminence due to degradation of the river. Industries

in the vicinity of rivers too get affected due to reduction

in stream flows leading to river pollution affecting

people along the downstream river stretches. All such

adversely affected people are also categorized as PSA

stakeholders.

Secondary Social Adversely Affected (SSA)

Stakeholders

The SSA stakeholders are indirectly concerned with the

adverse consequences of the project. This group may

include people who are emotionally aggrieved by the

displacement of near and dear ones, though they are

themselves not displaced. Similarly, in the case of

partially affected villages, the people left out from

displacement may suffer social, cultural, and economic

deprivation, and not being treated as project affected,

may not get compensated for the loss.

The SSA stakeholders also include individuals or

organizations who themselves are not affected but voice

concern for those subjected to large scale displacement

and hardships. They unite the segmented group of

oustees who are not only dispersed but belong to diverse

VIKALPA • VOLUME 29 • NO 1 • JANUARY - MARCH 2004 69

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

social, cultural, and economic strata. They educate the

oustees, who are mostly illiterate, about their own rights

in a democratic set-up. They provide oustees with

financial and material support for commencing and

sustaining agitations against projects. On behalf of

seemingly failing oustees, they also file legal suits

against the projects and thus provide judicial opportu-

nities to the displaced people. Many a times, such groups

with high-tech resources like large databank, audio-

video documentation, websites, etc., not only awaken

the media, political parties, and the general public but

also create significant hurdles in the way of project

funding by bringing influences on the funding foreign

governments and international financiers like World

Bank, IMF, etc. They often oppose water resource projects

in all their dimensions and fail to see any possible

advantages from them. They also refuse negotiated

settlements thereby jeopardizing the best interests of the

oustees. Remaining in the shadows of leading person-

alities of these (secondary) stakeholders, the directly

affected people may sometimes find their real issues and

voices muffled altogether.

There are also cases of SSA stakeholders’ entities

that work in collaboration with project authorities for

resettlement and rehabilitation of project oustees. Since

the project-displaced people are often not a part of the

mainstream society, they tend to be vulnerable when

officials with little competency in handling their affairs

try to mediate. In such cases, presence of secondary

stakeholders (with knowledge of local dialect and famil-

iarity of culture) considerably helps in mitigating the

hardships of project oustees.

Primary Non-social Adversely Affected (PNA)

Stakeholders

The flooding of large river valley areas by project

reservoirs along with the project construction activities

involving laying of roads, power lines, etc., leads to

fragmentation and destruction of forests. The deforesta-

tion (especially of tropical forests) caused by the water

resource projects is considered as one of the gravest

environmental concerns the world over. Between 50 to

90 per cent of all the earth’s species are believed to be

living in tropical rainforests which cover less than six

per cent of the total land area. It is estimated that project

reservoirs have traditionally caused about 10 per cent

of the total annual deforestation in the tropics, thereby

posing a great threat to biological diversity with the

possibility of total extinction of some of the genes,

species, and ecosystems (FIVAS, 1996). Though it is

difficult to predict the consequences of loss of such life

forms, it is generally believed that the loss will prove

to be a serious threat to our biosphere. Besides, forests

control the earth’s climate and deforestation may change

the global hydrological cycle, distribution of heat and

rainfall, and the chemical composition of the atmos-

phere. Thus, the forest ecology affected by project

constructionconstitutesthe PNA stakeholderentity.

The nomadic tribes of hunters and gatherers who are

the original inhabitants of these forests with immense

traditional knowledge of herbs, fruits, spices, and

medicinal plants, even unknown to modern science,

often fail to establish any social relationship with the

outside world. This set of people, affected along with

the flora and fauna of forest areas undergoing submer-

gence also falls in the PNA stakeholder group.

Many ancient monuments, religious places, and

archaeological sites may also go under submergence.

Artificially created submergences are known to induce

seismicity2 in and around reservoir areas. Numerous

adverse ecological effects are also felt in the area down-

stream of project reservoir due to changes in the channel

and flow characteristics of the river with major impact

falling on aquatic lives.3 Changes in the river bed grade

due to increased bed erosion are also possible owing to

reduction in the river silt load. Sustained reduction in

river flow may also cause salt intrusion in the estuarine