Commercialization of Technological Innovation: A Strategic Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2022/01/23

|8

|6158

|23

Report

AI Summary

This report analyzes the factors contributing to the successful development and commercialization of technological innovations, focusing on the interplay between a firm's strategic orientation (Prospector, Analyzer, Defender) and its market strategy. It examines how firms can navigate the innovator's dilemma by selecting appropriate target markets and implementing effective market orientations. The report builds links between Christensen's work on the innovator's dilemma and Moore's work on crossing the chasm. It also explores the relationship between customer-market orientation and the development of disruptive innovations. The study emphasizes the importance of developing contradictory skill sets to succeed across various innovation types and customer segments, drawing on market strategy and market orientation literature to refine the understanding of technological innovation commercialization. The report discusses the adoption and diffusion cycle, the chasm between visionaries and pragmatists, and the role of cross-market communication in successful commercialization.

Successful Development and Commercialization of

Technological Innovation: Insights Based on Strategy Type

Stanley F. Slater and Jakki J. Mohr

H ow can market leaders avoid the innovator’s

dilemma and continually develop disruptive

innovations to retain their leadership posi-

tion? We argue that the capability to successfully de-

velop and commercializeone type of disruptive

innovation—technologicalinnovation—isbased on

the interaction between a firm’s strategic orientation

(Prospector, Analyzer, Defender) and (1) its selection

of targetmarket;and (2) the way it implements its

market orientation.The insights offered by this

framework assist in predicting whether a firm’s stra-

tegic orientation enhancesor thwartsits ability to

successfully commercialize disruptive innovations and

also suggests the development of critical,yet contra-

dictory,skill sets in order to remain successfulover

time.

How can industry leaders reinvent themselves by

developing and successfully commercializing disrup-

tive innovations that challenge their existing business

models? Known as the innovator’s dilemma, Christen-

sen (1997) argued that market leaders have difficulty

diverting resources from the development of sustain-

ing innovations, which address known customer needs

in established markets, to the development of disrup-

tive innovations,which often underperform estab-

lished productsin mainstream marketsbut offer

benefits some emerging customers value.

Christensen’s (1997) initial research focused prima-

rily on technologicalinnovations,broadly defined as

those that introduce a different set of features,per-

formance,and price attributesrelativeto existing

products and technologies.In other words,techno-

logical innovations create new products based on new

underlying technologicalunderpinnings.Over time,

further developments improve the new technology’s

performance on the attributes mainstream customers

do value, to a level where the new technology begins

to cannibalize the existing technology.This progres-

sion reflects the classic S-shaped curve prevalent in the

study of technologicaldiscontinuities (e.g.,Chandy

and Tellis, 2000;Shanklin and Ryans,1987).The

focus of this article is on these technologicalinno-

vations, though distinctions exist between other types

of innovations and their dimensions.For example,

Govindarajan and Kopalle (2004) distinguish disrup-

tive innovations further based on their radicalness, or

new products based on a new technology relative to

whatalready exists in the industry.Their empirical

research shows that all disruptive innovations are not

necessarily radical (e.g., Schwab’s discount brokerage

businessmodel), nor are all radical innovations

necessarily disruptive (e.g.,cordless phones relied on

substantially new technology relative to wired phones

but were not disruptive to the industry). Some can be

both radical and disruptive (e.g., cellular phones).

Through his studiesof disruptiveinnovations,

Christensen(Christensen,1997; Christensenand

Bower,1996;Christensen and Raynor,2003;Chris-

tensen,Scott,and Roth, 2004)has spawned a sub-

stantial stream of research investigating many aspects

of the innovator’sdilemma (e.g.,Danneels,2004).

One componentof Christensen’s arguments is that

because incumbents listen too carefully to their cus-

tomers,they are disrupted by industry newcomers

that serve emerging customer segments. For example,

Christensen and Bower (1996, p. 198) state that mar-

ket-oriented firmscannotcreate disruptive innova-

tions since ‘‘firms lose their position of industry

leadership . . . because they listen too carefully to their

customers.’’ At its heart, this issue ties to both the se-

lection of a firm’s target market (emerging customer

segments versus existing customer segments) as well as

Address correspondence to: Stanley F. Slater, College of Business,

Colorado State University,Fort Collins, CO 80523-1275.Tel: (970)

491-2994. Fax: (970) 491-5956. E-mail: Stanley.Slater@Colostate.edu.

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2006;23:26–33

r 2006 Product Development & Management Association

Technological Innovation: Insights Based on Strategy Type

Stanley F. Slater and Jakki J. Mohr

H ow can market leaders avoid the innovator’s

dilemma and continually develop disruptive

innovations to retain their leadership posi-

tion? We argue that the capability to successfully de-

velop and commercializeone type of disruptive

innovation—technologicalinnovation—isbased on

the interaction between a firm’s strategic orientation

(Prospector, Analyzer, Defender) and (1) its selection

of targetmarket;and (2) the way it implements its

market orientation.The insights offered by this

framework assist in predicting whether a firm’s stra-

tegic orientation enhancesor thwartsits ability to

successfully commercialize disruptive innovations and

also suggests the development of critical,yet contra-

dictory,skill sets in order to remain successfulover

time.

How can industry leaders reinvent themselves by

developing and successfully commercializing disrup-

tive innovations that challenge their existing business

models? Known as the innovator’s dilemma, Christen-

sen (1997) argued that market leaders have difficulty

diverting resources from the development of sustain-

ing innovations, which address known customer needs

in established markets, to the development of disrup-

tive innovations,which often underperform estab-

lished productsin mainstream marketsbut offer

benefits some emerging customers value.

Christensen’s (1997) initial research focused prima-

rily on technologicalinnovations,broadly defined as

those that introduce a different set of features,per-

formance,and price attributesrelativeto existing

products and technologies.In other words,techno-

logical innovations create new products based on new

underlying technologicalunderpinnings.Over time,

further developments improve the new technology’s

performance on the attributes mainstream customers

do value, to a level where the new technology begins

to cannibalize the existing technology.This progres-

sion reflects the classic S-shaped curve prevalent in the

study of technologicaldiscontinuities (e.g.,Chandy

and Tellis, 2000;Shanklin and Ryans,1987).The

focus of this article is on these technologicalinno-

vations, though distinctions exist between other types

of innovations and their dimensions.For example,

Govindarajan and Kopalle (2004) distinguish disrup-

tive innovations further based on their radicalness, or

new products based on a new technology relative to

whatalready exists in the industry.Their empirical

research shows that all disruptive innovations are not

necessarily radical (e.g., Schwab’s discount brokerage

businessmodel), nor are all radical innovations

necessarily disruptive (e.g.,cordless phones relied on

substantially new technology relative to wired phones

but were not disruptive to the industry). Some can be

both radical and disruptive (e.g., cellular phones).

Through his studiesof disruptiveinnovations,

Christensen(Christensen,1997; Christensenand

Bower,1996;Christensen and Raynor,2003;Chris-

tensen,Scott,and Roth, 2004)has spawned a sub-

stantial stream of research investigating many aspects

of the innovator’sdilemma (e.g.,Danneels,2004).

One componentof Christensen’s arguments is that

because incumbents listen too carefully to their cus-

tomers,they are disrupted by industry newcomers

that serve emerging customer segments. For example,

Christensen and Bower (1996, p. 198) state that mar-

ket-oriented firmscannotcreate disruptive innova-

tions since ‘‘firms lose their position of industry

leadership . . . because they listen too carefully to their

customers.’’ At its heart, this issue ties to both the se-

lection of a firm’s target market (emerging customer

segments versus existing customer segments) as well as

Address correspondence to: Stanley F. Slater, College of Business,

Colorado State University,Fort Collins, CO 80523-1275.Tel: (970)

491-2994. Fax: (970) 491-5956. E-mail: Stanley.Slater@Colostate.edu.

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2006;23:26–33

r 2006 Product Development & Management Association

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

the way a firm implements its market orientation (e.g.,

listening to current customers’ articulation of existing

needs or conducting proactive research on potential

customers’unarticulated needs;see also Henderson,

this issue).

For those who study the successful commercializa-

tion of technologicalinnovation,a logicalquestion

arises as to the overlap between Christensen’s work

and the influential work of Geoffrey Moore in Cross-

ing the Chasm (1991, 2002). Moore’s work highlights

the difficulties firms face in commercializing new tech-

nologies, focusing on (among other things) the choice

of the initialmarketsegmentto targetand how to

modify the initialmarketing approach that was suc-

cessfulwith early adoptersof the productso that

mainstream customers will also embrace the new tech-

nology. These issues were also identified in Danneels’s

(2004) critique of Christensen’s (1997) work. For ex-

ample,Danneels discusses the complexities in fore-

castingwhen mainstream customerswill actually

embrace the new technology and in selecting a target

market for the new innovation when the firm has not

previously served customers in that target market.

Given the commonalitiesbetween Christensen’s

(1997) and Moore’s (1991, 2002) works in understand-

ing the successful development and commercialization

of technological innovations, one purpose of this ar-

ticle is to build links between Christensen’s influential

work on the innovator’s dilemma and Moore’s work

on crossing the chasm. A second purpose is to explore

whether or nota customer–marketorientation is a

liability in developing disruptive innovations.

The common thread in this article binding these

two somewhat distinct purposes together is our belief

that a firm’s strategic orientation (in particular, based

on the Miles and Snow [1978] typology of prospectors,

analyzers, and defenders) offers useful insights for un-

derstanding why some firms are more successfulat

commercializingtechnological innovations than

others. This typology is well validated and continues

to receive quite a bitof empiricalattention (e.g.,

DeSarbo et al.,2005;Hambrick,2003;Vorhies and

Morgan, 2003).

In particular,we examine how firm strategy (i.e.,

prospector, analyzer, defender) can explain success in

commercializing technologicalinnovationswith re-

spectto (1) the customergroupsthe firm targets;

and (2) its approach to being marketoriented.For

clarity, it is importantto realize thatwe are not

offering a new classification of Christensen’s disrup-

tive-sustaining innovation typology.Rather,we are

suggesting thatby overlaying the Milesand Snow

(1978) typology of firm strategy onto the disruptive-

sustaining innovation typology,additionalinsights

regarding which firmsare more likely to develop

and benefit from sustaining or disruptive innovations

may be gleaned.

Market Strategy and Success with

Disruptive Innovations

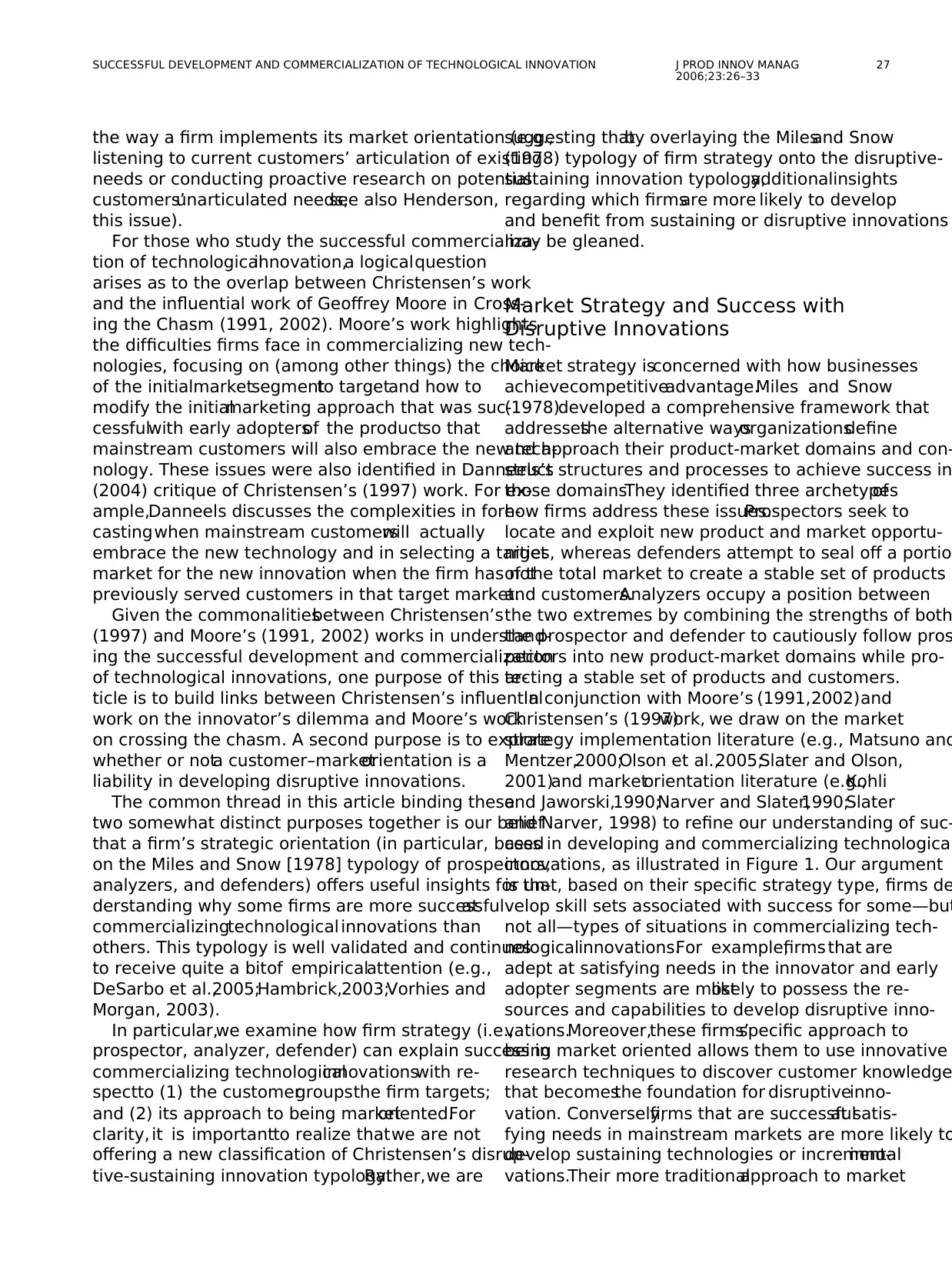

Market strategy isconcerned with how businesses

achievecompetitiveadvantage.Miles and Snow

(1978)developed a comprehensive framework that

addressesthe alternative waysorganizationsdefine

and approach their product-market domains and con-

struct structures and processes to achieve success in

those domains.They identified three archetypesof

how firms address these issues.Prospectors seek to

locate and exploit new product and market opportu-

nities, whereas defenders attempt to seal off a portio

of the total market to create a stable set of products

and customers.Analyzers occupy a position between

the two extremes by combining the strengths of both

the prospector and defender to cautiously follow pros

pectors into new product-market domains while pro-

tecting a stable set of products and customers.

In conjunction with Moore’s (1991,2002)and

Christensen’s (1997)work, we draw on the market

strategy implementation literature (e.g., Matsuno and

Mentzer,2000;Olson et al.,2005;Slater and Olson,

2001)and marketorientation literature (e.g.,Kohli

and Jaworski,1990;Narver and Slater,1990;Slater

and Narver, 1998) to refine our understanding of suc-

cess in developing and commercializing technological

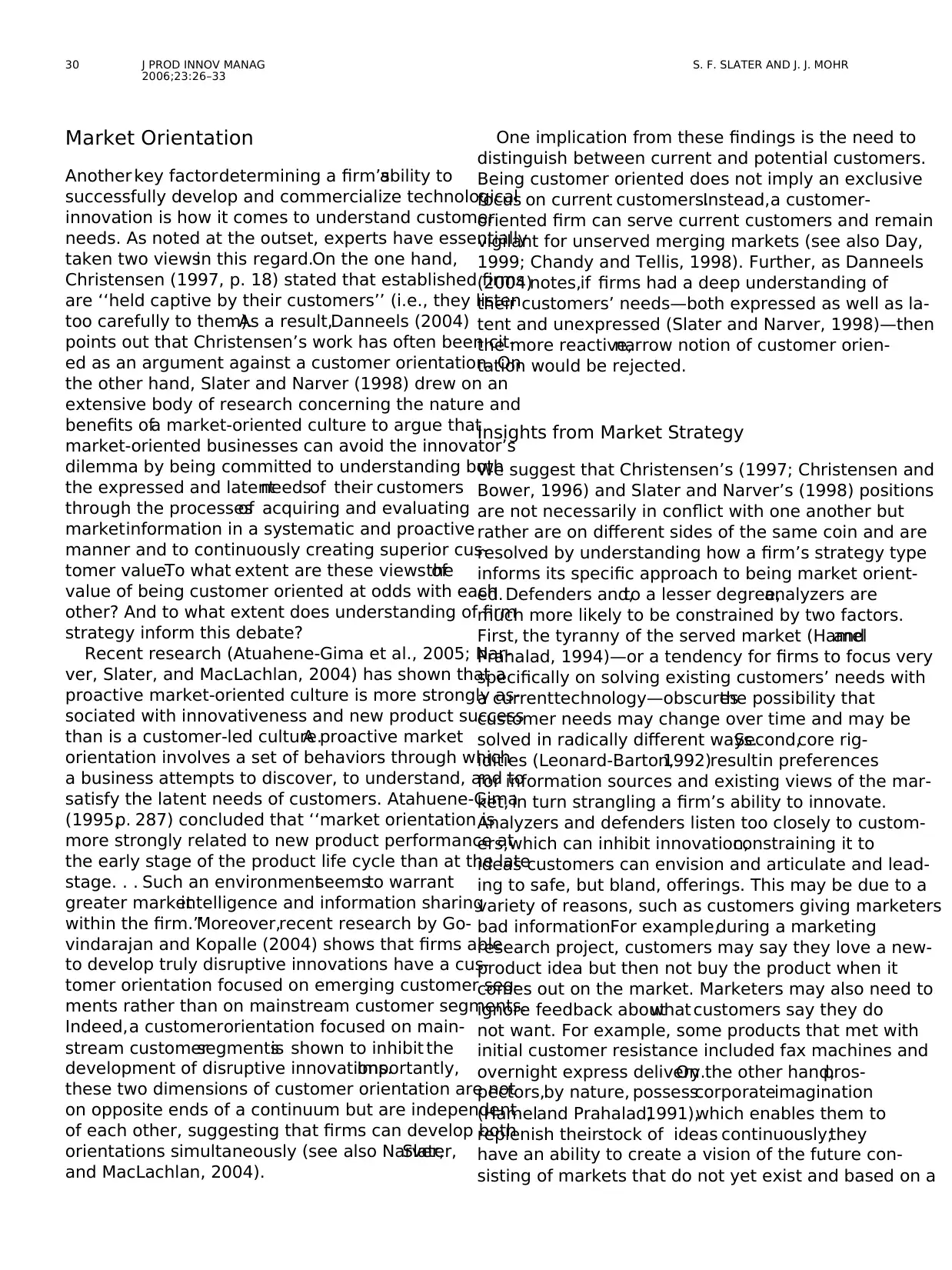

innovations, as illustrated in Figure 1. Our argument

is that, based on their specific strategy type, firms de

velop skill sets associated with success for some—but

not all—types of situations in commercializing tech-

nologicalinnovations.For example,firms that are

adept at satisfying needs in the innovator and early

adopter segments are mostlikely to possess the re-

sources and capabilities to develop disruptive inno-

vations.Moreover,these firms’specific approach to

being market oriented allows them to use innovative

research techniques to discover customer knowledge

that becomesthe foundation for disruptiveinno-

vation. Conversely,firms that are successfulat satis-

fying needs in mainstream markets are more likely to

develop sustaining technologies or incrementalinno-

vations.Their more traditionalapproach to market

SUCCESSFUL DEVELOPMENT AND COMMERCIALIZATION OF TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION J PROD INNOV MANAG

2006;23:26–33

27

listening to current customers’ articulation of existing

needs or conducting proactive research on potential

customers’unarticulated needs;see also Henderson,

this issue).

For those who study the successful commercializa-

tion of technologicalinnovation,a logicalquestion

arises as to the overlap between Christensen’s work

and the influential work of Geoffrey Moore in Cross-

ing the Chasm (1991, 2002). Moore’s work highlights

the difficulties firms face in commercializing new tech-

nologies, focusing on (among other things) the choice

of the initialmarketsegmentto targetand how to

modify the initialmarketing approach that was suc-

cessfulwith early adoptersof the productso that

mainstream customers will also embrace the new tech-

nology. These issues were also identified in Danneels’s

(2004) critique of Christensen’s (1997) work. For ex-

ample,Danneels discusses the complexities in fore-

castingwhen mainstream customerswill actually

embrace the new technology and in selecting a target

market for the new innovation when the firm has not

previously served customers in that target market.

Given the commonalitiesbetween Christensen’s

(1997) and Moore’s (1991, 2002) works in understand-

ing the successful development and commercialization

of technological innovations, one purpose of this ar-

ticle is to build links between Christensen’s influential

work on the innovator’s dilemma and Moore’s work

on crossing the chasm. A second purpose is to explore

whether or nota customer–marketorientation is a

liability in developing disruptive innovations.

The common thread in this article binding these

two somewhat distinct purposes together is our belief

that a firm’s strategic orientation (in particular, based

on the Miles and Snow [1978] typology of prospectors,

analyzers, and defenders) offers useful insights for un-

derstanding why some firms are more successfulat

commercializingtechnological innovations than

others. This typology is well validated and continues

to receive quite a bitof empiricalattention (e.g.,

DeSarbo et al.,2005;Hambrick,2003;Vorhies and

Morgan, 2003).

In particular,we examine how firm strategy (i.e.,

prospector, analyzer, defender) can explain success in

commercializing technologicalinnovationswith re-

spectto (1) the customergroupsthe firm targets;

and (2) its approach to being marketoriented.For

clarity, it is importantto realize thatwe are not

offering a new classification of Christensen’s disrup-

tive-sustaining innovation typology.Rather,we are

suggesting thatby overlaying the Milesand Snow

(1978) typology of firm strategy onto the disruptive-

sustaining innovation typology,additionalinsights

regarding which firmsare more likely to develop

and benefit from sustaining or disruptive innovations

may be gleaned.

Market Strategy and Success with

Disruptive Innovations

Market strategy isconcerned with how businesses

achievecompetitiveadvantage.Miles and Snow

(1978)developed a comprehensive framework that

addressesthe alternative waysorganizationsdefine

and approach their product-market domains and con-

struct structures and processes to achieve success in

those domains.They identified three archetypesof

how firms address these issues.Prospectors seek to

locate and exploit new product and market opportu-

nities, whereas defenders attempt to seal off a portio

of the total market to create a stable set of products

and customers.Analyzers occupy a position between

the two extremes by combining the strengths of both

the prospector and defender to cautiously follow pros

pectors into new product-market domains while pro-

tecting a stable set of products and customers.

In conjunction with Moore’s (1991,2002)and

Christensen’s (1997)work, we draw on the market

strategy implementation literature (e.g., Matsuno and

Mentzer,2000;Olson et al.,2005;Slater and Olson,

2001)and marketorientation literature (e.g.,Kohli

and Jaworski,1990;Narver and Slater,1990;Slater

and Narver, 1998) to refine our understanding of suc-

cess in developing and commercializing technological

innovations, as illustrated in Figure 1. Our argument

is that, based on their specific strategy type, firms de

velop skill sets associated with success for some—but

not all—types of situations in commercializing tech-

nologicalinnovations.For example,firms that are

adept at satisfying needs in the innovator and early

adopter segments are mostlikely to possess the re-

sources and capabilities to develop disruptive inno-

vations.Moreover,these firms’specific approach to

being market oriented allows them to use innovative

research techniques to discover customer knowledge

that becomesthe foundation for disruptiveinno-

vation. Conversely,firms that are successfulat satis-

fying needs in mainstream markets are more likely to

develop sustaining technologies or incrementalinno-

vations.Their more traditionalapproach to market

SUCCESSFUL DEVELOPMENT AND COMMERCIALIZATION OF TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION J PROD INNOV MANAG

2006;23:26–33

27

orientation is to listen to customers and to develop

innovations based on customer feedback.

However,to be successfulacross a range of inno-

vations (both sustaining and disruptive),firms must

also develop skill sets of other strategy types. For ex-

ample,a firm that tends to be more successfulwith

late majority customers may need a more proactive

approach to developing customerknowledge;new

techniques of market research may help it avoid fo-

cusing myopically only on existing customers and may

facilitate the development of disruptive technological

innovations. In essence, the capability to develop con-

tradictory skill sets is vital.

We first examine the relationship between selection

of target market and strategy type and then explore

the relationshipbetweenmarket orientationand

strategy type.

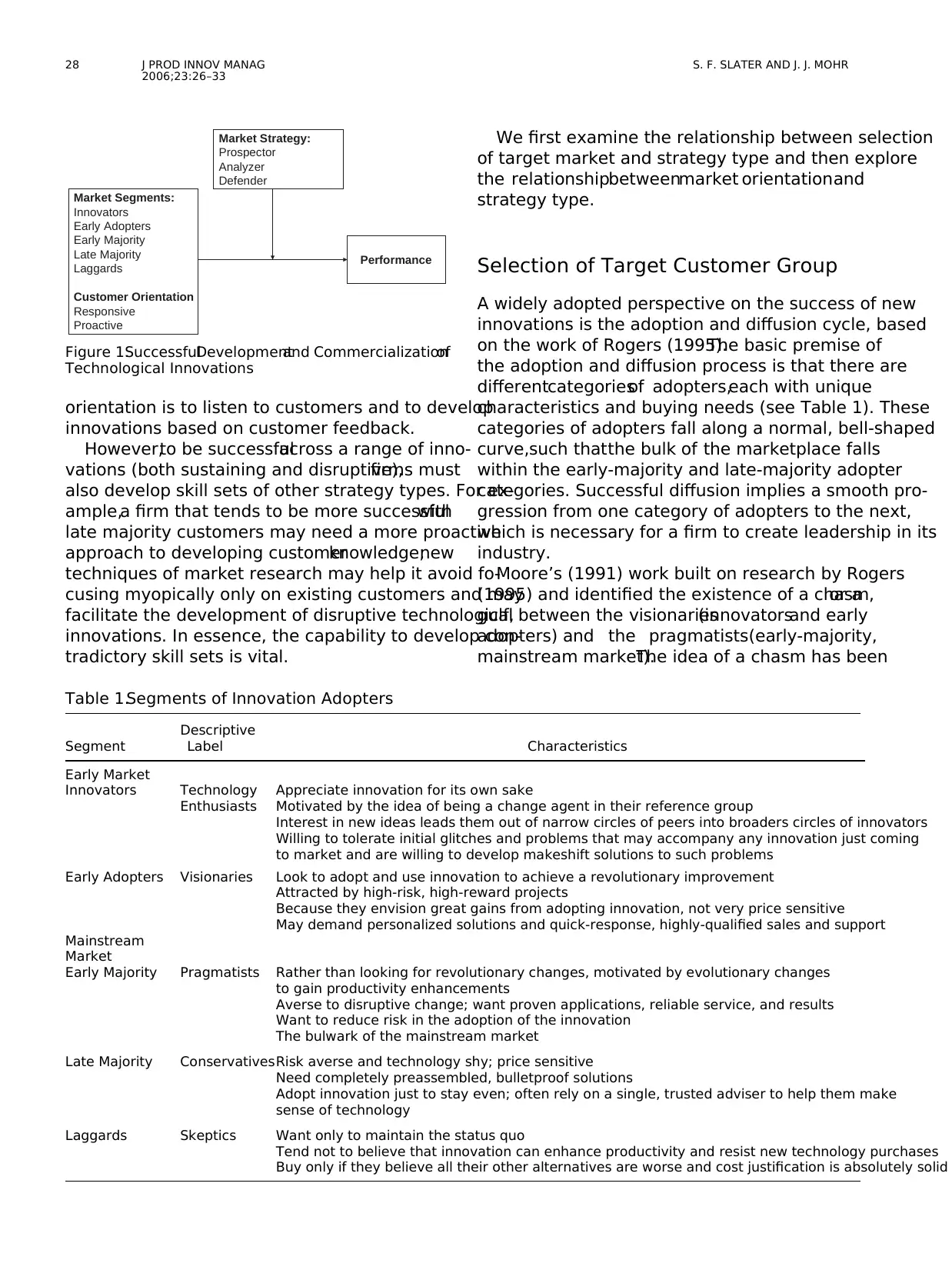

Selection of Target Customer Group

A widely adopted perspective on the success of new

innovations is the adoption and diffusion cycle, based

on the work of Rogers (1995).The basic premise of

the adoption and diffusion process is that there are

differentcategoriesof adopters,each with unique

characteristics and buying needs (see Table 1). These

categories of adopters fall along a normal, bell-shaped

curve,such thatthe bulk of the marketplace falls

within the early-majority and late-majority adopter

categories. Successful diffusion implies a smooth pro-

gression from one category of adopters to the next,

which is necessary for a firm to create leadership in its

industry.

Moore’s (1991) work built on research by Rogers

(1995) and identified the existence of a chasm,or a

gulf, between the visionaries(innovatorsand early

adopters) and the pragmatists(early-majority,

mainstream market).The idea of a chasm has been

Market Segments:

Innovators

Early Adopters

Early Majority

Late Majority

Laggards

Customer Orientation

Responsive

Proactive

Performance

Market Strategy:

Prospector

Analyzer

Defender

Figure 1.SuccessfulDevelopmentand Commercializationof

Technological Innovations

Table 1.Segments of Innovation Adopters

Segment

Descriptive

Label Characteristics

Early Market

Innovators Technology

Enthusiasts

Appreciate innovation for its own sake

Motivated by the idea of being a change agent in their reference group

Interest in new ideas leads them out of narrow circles of peers into broaders circles of innovators

Willing to tolerate initial glitches and problems that may accompany any innovation just coming

to market and are willing to develop makeshift solutions to such problems

Early Adopters Visionaries Look to adopt and use innovation to achieve a revolutionary improvement

Attracted by high-risk, high-reward projects

Because they envision great gains from adopting innovation, not very price sensitive

May demand personalized solutions and quick-response, highly-qualified sales and support

Mainstream

Market

Early Majority Pragmatists Rather than looking for revolutionary changes, motivated by evolutionary changes

to gain productivity enhancements

Averse to disruptive change; want proven applications, reliable service, and results

Want to reduce risk in the adoption of the innovation

The bulwark of the mainstream market

Late Majority ConservativesRisk averse and technology shy; price sensitive

Need completely preassembled, bulletproof solutions

Adopt innovation just to stay even; often rely on a single, trusted adviser to help them make

sense of technology

Laggards Skeptics Want only to maintain the status quo

Tend not to believe that innovation can enhance productivity and resist new technology purchases

Buy only if they believe all their other alternatives are worse and cost justification is absolutely solid

28 J PROD INNOV MANAG

2006;23:26–33

S. F. SLATER AND J. J. MOHR

innovations based on customer feedback.

However,to be successfulacross a range of inno-

vations (both sustaining and disruptive),firms must

also develop skill sets of other strategy types. For ex-

ample,a firm that tends to be more successfulwith

late majority customers may need a more proactive

approach to developing customerknowledge;new

techniques of market research may help it avoid fo-

cusing myopically only on existing customers and may

facilitate the development of disruptive technological

innovations. In essence, the capability to develop con-

tradictory skill sets is vital.

We first examine the relationship between selection

of target market and strategy type and then explore

the relationshipbetweenmarket orientationand

strategy type.

Selection of Target Customer Group

A widely adopted perspective on the success of new

innovations is the adoption and diffusion cycle, based

on the work of Rogers (1995).The basic premise of

the adoption and diffusion process is that there are

differentcategoriesof adopters,each with unique

characteristics and buying needs (see Table 1). These

categories of adopters fall along a normal, bell-shaped

curve,such thatthe bulk of the marketplace falls

within the early-majority and late-majority adopter

categories. Successful diffusion implies a smooth pro-

gression from one category of adopters to the next,

which is necessary for a firm to create leadership in its

industry.

Moore’s (1991) work built on research by Rogers

(1995) and identified the existence of a chasm,or a

gulf, between the visionaries(innovatorsand early

adopters) and the pragmatists(early-majority,

mainstream market).The idea of a chasm has been

Market Segments:

Innovators

Early Adopters

Early Majority

Late Majority

Laggards

Customer Orientation

Responsive

Proactive

Performance

Market Strategy:

Prospector

Analyzer

Defender

Figure 1.SuccessfulDevelopmentand Commercializationof

Technological Innovations

Table 1.Segments of Innovation Adopters

Segment

Descriptive

Label Characteristics

Early Market

Innovators Technology

Enthusiasts

Appreciate innovation for its own sake

Motivated by the idea of being a change agent in their reference group

Interest in new ideas leads them out of narrow circles of peers into broaders circles of innovators

Willing to tolerate initial glitches and problems that may accompany any innovation just coming

to market and are willing to develop makeshift solutions to such problems

Early Adopters Visionaries Look to adopt and use innovation to achieve a revolutionary improvement

Attracted by high-risk, high-reward projects

Because they envision great gains from adopting innovation, not very price sensitive

May demand personalized solutions and quick-response, highly-qualified sales and support

Mainstream

Market

Early Majority Pragmatists Rather than looking for revolutionary changes, motivated by evolutionary changes

to gain productivity enhancements

Averse to disruptive change; want proven applications, reliable service, and results

Want to reduce risk in the adoption of the innovation

The bulwark of the mainstream market

Late Majority ConservativesRisk averse and technology shy; price sensitive

Need completely preassembled, bulletproof solutions

Adopt innovation just to stay even; often rely on a single, trusted adviser to help them make

sense of technology

Laggards Skeptics Want only to maintain the status quo

Tend not to believe that innovation can enhance productivity and resist new technology purchases

Buy only if they believe all their other alternatives are worse and cost justification is absolutely solid

28 J PROD INNOV MANAG

2006;23:26–33

S. F. SLATER AND J. J. MOHR

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

empirically validated in work by Goldenberg,Libai,

and Muller (2002).In their study ofthe pattern of

diffusion of a large number of innovative products in

the consumer electronicsindustry, they found

that between one-third and one-halfof the cases

exhibited a ‘‘saddle’’(i.e.,a lull in sales after initial

market take-off that stymied the steady adoption and

diffusion process). Their work also showed that word-

of-mouth effects among categoriesof adopters

(i.e.,cross-marketcommunication)were the critical

factor in determining the size and duration ofthe

sales slump.

Some firms are able to reach only a smallniche

market of technology enthusiasts, whereas other firms

are able to successfully commercialize their inventions

by reaching a broader base of customers in the main-

stream market as well. Moore (1991) argued that the

chasm arises because (1) criticaldifferences between

visionaries and pragmatists make cross-market com-

munication extremely difficult for technological inno-

vations (e.g.,Goldenberg,Libai, and Muller,2002);

and, more critically, (2) the marketing strategies firms

use to effectively reach the early market for technol-

ogy innovations do notspeak to the very different

needs of the mainstream market.

The question is to what extent a firm’s strategy type

affectsits ability to be successfulat marketing to

variouscategoriesof adopters,which is where the

intersection of firm strategy and success in commer-

cializing technology innovations becomes relevant.

Insights from Market Strategy

Becausemarket segmentationand targetingare

the foundation of market strategy, firm performance

is determined, at least in part, by the match between

target market selection and market strategy type. The

importance ofthis match is highlighted in a recent

study of technology-oriented businessesby Slater,

Hult, and Olson (2005),who examined the perform-

ance implicationsof targetingcustomeradoption

categoriesby strategy type.For prospectors,they

found a positive relationship between targeting the

innovator and early-adopter segments and perform-

ance and a negative relationship between targeting the

early-majority segmentand performance.This sug-

gests thatprospectors,who excelat exploiting new

productand marketopportunities,have a difficult

time reaching outto more mainstream customers

to successfullycommercializetheir technological

innovations.Conversely,for analyzers,they found a

positive relationship between targetingthe early-

adopterand early-majority segmentsand perform-

ance and a negative relationship between targeting th

innovator segment and performance;this latter find-

ing implies that analyzers may not have the capabil-

ities to develop the innovationsthat technology

enthusiasts value.

The findings from Slater,Hult, and Olson (2005)

and related studies (Conant, Mokway, and Varadara-

jan, 1990; Slater and Olson, 2001), which suggest tha

different strategy types have resources and capabiliti

that enable them to successfully target different mar-

ket segments,are quite consistent with Christensen’s

(1997)work. Market-share leaders tend to be anal-

yzers and defendersbecausethose strategy types

targetthe early-and late-majority segments ofthe

market comprising approximately two-thirds of mar-

ket demand. Of course, there is variation in the size o

the categories based on the nature of the innovation

and how its benefits are communicated,but the idea

of a normal, bell-shaped distribution is widely accept-

ed and has been confirmed by research using the Bas

model (e.g., Mahajan, Muller, and Bass, 1990). Anal-

yzersand defendersalso havethe marketing and

operationalcompetenciesto succeed in thoseseg-

ments(Slater and Olson, 2001;Slater,Hult, and

Olson, 2005).As Christensen notes,thesemarket

leaders are largely unsuccessfulwhen attempting to

introduce innovations into niche markets.One key

reason for this is that defenders prefer predictability;

as a result,they tend to be neither innovation nor

technology oriented.In contrast,analyzers,though

not as risk averse as defenders, prefer incremental in

novation to disruptive innovation.

A critical implicationarising from this inter-

section of strategytype and selectionof target

market is the idea that businessesmust develop

what are often contradictory resources and capabili-

ties to be successfulin appealing to a wide range of

customertypes.For example,for prospectorsto

appeal successfully to all categories of adopters, they

must develop some of the resources and capabilities

analyzers.Similarly,for analyzers and defenders to

avoid the innovator’s dilemma by successfully devel-

oping and introducing disruptiveinnovationsthat

appealto technology enthusiasts—customers in the

early market—they mustdevelop some prospector

resourcesand capabilities.More specificinsights

related to these ideas are discussed in the conclusion

section.

SUCCESSFUL DEVELOPMENT AND COMMERCIALIZATION OF TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION J PROD INNOV MANAG

2006;23:26–33

29

and Muller (2002).In their study ofthe pattern of

diffusion of a large number of innovative products in

the consumer electronicsindustry, they found

that between one-third and one-halfof the cases

exhibited a ‘‘saddle’’(i.e.,a lull in sales after initial

market take-off that stymied the steady adoption and

diffusion process). Their work also showed that word-

of-mouth effects among categoriesof adopters

(i.e.,cross-marketcommunication)were the critical

factor in determining the size and duration ofthe

sales slump.

Some firms are able to reach only a smallniche

market of technology enthusiasts, whereas other firms

are able to successfully commercialize their inventions

by reaching a broader base of customers in the main-

stream market as well. Moore (1991) argued that the

chasm arises because (1) criticaldifferences between

visionaries and pragmatists make cross-market com-

munication extremely difficult for technological inno-

vations (e.g.,Goldenberg,Libai, and Muller,2002);

and, more critically, (2) the marketing strategies firms

use to effectively reach the early market for technol-

ogy innovations do notspeak to the very different

needs of the mainstream market.

The question is to what extent a firm’s strategy type

affectsits ability to be successfulat marketing to

variouscategoriesof adopters,which is where the

intersection of firm strategy and success in commer-

cializing technology innovations becomes relevant.

Insights from Market Strategy

Becausemarket segmentationand targetingare

the foundation of market strategy, firm performance

is determined, at least in part, by the match between

target market selection and market strategy type. The

importance ofthis match is highlighted in a recent

study of technology-oriented businessesby Slater,

Hult, and Olson (2005),who examined the perform-

ance implicationsof targetingcustomeradoption

categoriesby strategy type.For prospectors,they

found a positive relationship between targeting the

innovator and early-adopter segments and perform-

ance and a negative relationship between targeting the

early-majority segmentand performance.This sug-

gests thatprospectors,who excelat exploiting new

productand marketopportunities,have a difficult

time reaching outto more mainstream customers

to successfullycommercializetheir technological

innovations.Conversely,for analyzers,they found a

positive relationship between targetingthe early-

adopterand early-majority segmentsand perform-

ance and a negative relationship between targeting th

innovator segment and performance;this latter find-

ing implies that analyzers may not have the capabil-

ities to develop the innovationsthat technology

enthusiasts value.

The findings from Slater,Hult, and Olson (2005)

and related studies (Conant, Mokway, and Varadara-

jan, 1990; Slater and Olson, 2001), which suggest tha

different strategy types have resources and capabiliti

that enable them to successfully target different mar-

ket segments,are quite consistent with Christensen’s

(1997)work. Market-share leaders tend to be anal-

yzers and defendersbecausethose strategy types

targetthe early-and late-majority segments ofthe

market comprising approximately two-thirds of mar-

ket demand. Of course, there is variation in the size o

the categories based on the nature of the innovation

and how its benefits are communicated,but the idea

of a normal, bell-shaped distribution is widely accept-

ed and has been confirmed by research using the Bas

model (e.g., Mahajan, Muller, and Bass, 1990). Anal-

yzersand defendersalso havethe marketing and

operationalcompetenciesto succeed in thoseseg-

ments(Slater and Olson, 2001;Slater,Hult, and

Olson, 2005).As Christensen notes,thesemarket

leaders are largely unsuccessfulwhen attempting to

introduce innovations into niche markets.One key

reason for this is that defenders prefer predictability;

as a result,they tend to be neither innovation nor

technology oriented.In contrast,analyzers,though

not as risk averse as defenders, prefer incremental in

novation to disruptive innovation.

A critical implicationarising from this inter-

section of strategytype and selectionof target

market is the idea that businessesmust develop

what are often contradictory resources and capabili-

ties to be successfulin appealing to a wide range of

customertypes.For example,for prospectorsto

appeal successfully to all categories of adopters, they

must develop some of the resources and capabilities

analyzers.Similarly,for analyzers and defenders to

avoid the innovator’s dilemma by successfully devel-

oping and introducing disruptiveinnovationsthat

appealto technology enthusiasts—customers in the

early market—they mustdevelop some prospector

resourcesand capabilities.More specificinsights

related to these ideas are discussed in the conclusion

section.

SUCCESSFUL DEVELOPMENT AND COMMERCIALIZATION OF TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION J PROD INNOV MANAG

2006;23:26–33

29

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Market Orientation

Another key factordetermining a firm’sability to

successfully develop and commercialize technological

innovation is how it comes to understand customer

needs. As noted at the outset, experts have essentially

taken two viewsin this regard.On the one hand,

Christensen (1997, p. 18) stated that established firms

are ‘‘held captive by their customers’’ (i.e., they listen

too carefully to them).As a result,Danneels (2004)

points out that Christensen’s work has often been cit-

ed as an argument against a customer orientation. On

the other hand, Slater and Narver (1998) drew on an

extensive body of research concerning the nature and

benefits ofa market-oriented culture to argue that

market-oriented businesses can avoid the innovator’s

dilemma by being committed to understanding both

the expressed and latentneedsof their customers

through the processesof acquiring and evaluating

marketinformation in a systematic and proactive

manner and to continuously creating superior cus-

tomer value.To what extent are these views ofthe

value of being customer oriented at odds with each

other? And to what extent does understanding of firm

strategy inform this debate?

Recent research (Atuahene-Gima et al., 2005; Nar-

ver, Slater, and MacLachlan, 2004) has shown that a

proactive market-oriented culture is more strongly as-

sociated with innovativeness and new product success

than is a customer-led culture.A proactive market

orientation involves a set of behaviors through which

a business attempts to discover, to understand, and to

satisfy the latent needs of customers. Atahuene-Gima

(1995,p. 287) concluded that ‘‘market orientation is

more strongly related to new product performance at

the early stage of the product life cycle than at the late

stage. . . Such an environmentseemsto warrant

greater marketintelligence and information sharing

within the firm.’’Moreover,recent research by Go-

vindarajan and Kopalle (2004) shows that firms able

to develop truly disruptive innovations have a cus-

tomer orientation focused on emerging customer seg-

ments rather than on mainstream customer segments.

Indeed,a customerorientation focused on main-

stream customersegmentsis shown to inhibit the

development of disruptive innovations.Importantly,

these two dimensions of customer orientation are not

on opposite ends of a continuum but are independent

of each other, suggesting that firms can develop both

orientations simultaneously (see also Narver,Slater,

and MacLachlan, 2004).

One implication from these findings is the need to

distinguish between current and potential customers.

Being customer oriented does not imply an exclusive

focus on current customers.Instead,a customer-

oriented firm can serve current customers and remain

vigilant for unserved merging markets (see also Day,

1999; Chandy and Tellis, 1998). Further, as Danneels

(2004)notes,if firms had a deep understanding of

their customers’ needs—both expressed as well as la-

tent and unexpressed (Slater and Narver, 1998)—then

the more reactive,narrow notion of customer orien-

tation would be rejected.

Insights from Market Strategy

We suggest that Christensen’s (1997; Christensen and

Bower, 1996) and Slater and Narver’s (1998) positions

are not necessarily in conflict with one another but

rather are on different sides of the same coin and are

resolved by understanding how a firm’s strategy type

informs its specific approach to being market orient-

ed. Defenders and,to a lesser degree,analyzers are

much more likely to be constrained by two factors.

First, the tyranny of the served market (Hameland

Prahalad, 1994)—or a tendency for firms to focus very

specifically on solving existing customers’ needs with

a currenttechnology—obscuresthe possibility that

customer needs may change over time and may be

solved in radically different ways.Second,core rig-

idities (Leonard-Barton,1992)resultin preferences

for information sources and existing views of the mar-

ket, in turn strangling a firm’s ability to innovate.

Analyzers and defenders listen too closely to custom-

ers,which can inhibit innovation,constraining it to

ideas customers can envision and articulate and lead-

ing to safe, but bland, offerings. This may be due to a

variety of reasons, such as customers giving marketers

bad information.For example,during a marketing

research project, customers may say they love a new-

product idea but then not buy the product when it

comes out on the market. Marketers may also need to

ignore feedback aboutwhat customers say they do

not want. For example, some products that met with

initial customer resistance included fax machines and

overnight express delivery.On the other hand,pros-

pectors,by nature, possesscorporateimagination

(Hameland Prahalad,1991),which enables them to

replenish theirstock of ideas continuously;they

have an ability to create a vision of the future con-

sisting of markets that do not yet exist and based on a

30 J PROD INNOV MANAG

2006;23:26–33

S. F. SLATER AND J. J. MOHR

Another key factordetermining a firm’sability to

successfully develop and commercialize technological

innovation is how it comes to understand customer

needs. As noted at the outset, experts have essentially

taken two viewsin this regard.On the one hand,

Christensen (1997, p. 18) stated that established firms

are ‘‘held captive by their customers’’ (i.e., they listen

too carefully to them).As a result,Danneels (2004)

points out that Christensen’s work has often been cit-

ed as an argument against a customer orientation. On

the other hand, Slater and Narver (1998) drew on an

extensive body of research concerning the nature and

benefits ofa market-oriented culture to argue that

market-oriented businesses can avoid the innovator’s

dilemma by being committed to understanding both

the expressed and latentneedsof their customers

through the processesof acquiring and evaluating

marketinformation in a systematic and proactive

manner and to continuously creating superior cus-

tomer value.To what extent are these views ofthe

value of being customer oriented at odds with each

other? And to what extent does understanding of firm

strategy inform this debate?

Recent research (Atuahene-Gima et al., 2005; Nar-

ver, Slater, and MacLachlan, 2004) has shown that a

proactive market-oriented culture is more strongly as-

sociated with innovativeness and new product success

than is a customer-led culture.A proactive market

orientation involves a set of behaviors through which

a business attempts to discover, to understand, and to

satisfy the latent needs of customers. Atahuene-Gima

(1995,p. 287) concluded that ‘‘market orientation is

more strongly related to new product performance at

the early stage of the product life cycle than at the late

stage. . . Such an environmentseemsto warrant

greater marketintelligence and information sharing

within the firm.’’Moreover,recent research by Go-

vindarajan and Kopalle (2004) shows that firms able

to develop truly disruptive innovations have a cus-

tomer orientation focused on emerging customer seg-

ments rather than on mainstream customer segments.

Indeed,a customerorientation focused on main-

stream customersegmentsis shown to inhibit the

development of disruptive innovations.Importantly,

these two dimensions of customer orientation are not

on opposite ends of a continuum but are independent

of each other, suggesting that firms can develop both

orientations simultaneously (see also Narver,Slater,

and MacLachlan, 2004).

One implication from these findings is the need to

distinguish between current and potential customers.

Being customer oriented does not imply an exclusive

focus on current customers.Instead,a customer-

oriented firm can serve current customers and remain

vigilant for unserved merging markets (see also Day,

1999; Chandy and Tellis, 1998). Further, as Danneels

(2004)notes,if firms had a deep understanding of

their customers’ needs—both expressed as well as la-

tent and unexpressed (Slater and Narver, 1998)—then

the more reactive,narrow notion of customer orien-

tation would be rejected.

Insights from Market Strategy

We suggest that Christensen’s (1997; Christensen and

Bower, 1996) and Slater and Narver’s (1998) positions

are not necessarily in conflict with one another but

rather are on different sides of the same coin and are

resolved by understanding how a firm’s strategy type

informs its specific approach to being market orient-

ed. Defenders and,to a lesser degree,analyzers are

much more likely to be constrained by two factors.

First, the tyranny of the served market (Hameland

Prahalad, 1994)—or a tendency for firms to focus very

specifically on solving existing customers’ needs with

a currenttechnology—obscuresthe possibility that

customer needs may change over time and may be

solved in radically different ways.Second,core rig-

idities (Leonard-Barton,1992)resultin preferences

for information sources and existing views of the mar-

ket, in turn strangling a firm’s ability to innovate.

Analyzers and defenders listen too closely to custom-

ers,which can inhibit innovation,constraining it to

ideas customers can envision and articulate and lead-

ing to safe, but bland, offerings. This may be due to a

variety of reasons, such as customers giving marketers

bad information.For example,during a marketing

research project, customers may say they love a new-

product idea but then not buy the product when it

comes out on the market. Marketers may also need to

ignore feedback aboutwhat customers say they do

not want. For example, some products that met with

initial customer resistance included fax machines and

overnight express delivery.On the other hand,pros-

pectors,by nature, possesscorporateimagination

(Hameland Prahalad,1991),which enables them to

replenish theirstock of ideas continuously;they

have an ability to create a vision of the future con-

sisting of markets that do not yet exist and based on a

30 J PROD INNOV MANAG

2006;23:26–33

S. F. SLATER AND J. J. MOHR

horizon not confined by the boundaries of the current

business.

Once again, analyzers and defenders must augment

their skill sets with those more characteristicof

prospectors.One means for doing this is to rely on

novel types of market research to provide new types of

insights for innovation. For example, customers may

not always be able to articulate their needs;that is,

they have needs of which they are not aware; the needs

are real but are not yet in the customer’s awareness. If

these needs are not satisfied by a provider, there is no

customer demand or response. They are not dissatis-

fied, because the need is unknown to them. If a pro-

vider understandssuch a need and fulfillsit, the

customer is rapidly delighted.Based on this belief,

usefulinformation can be gleaned through observa-

tion of what customers do under normal, natural con-

ditions.

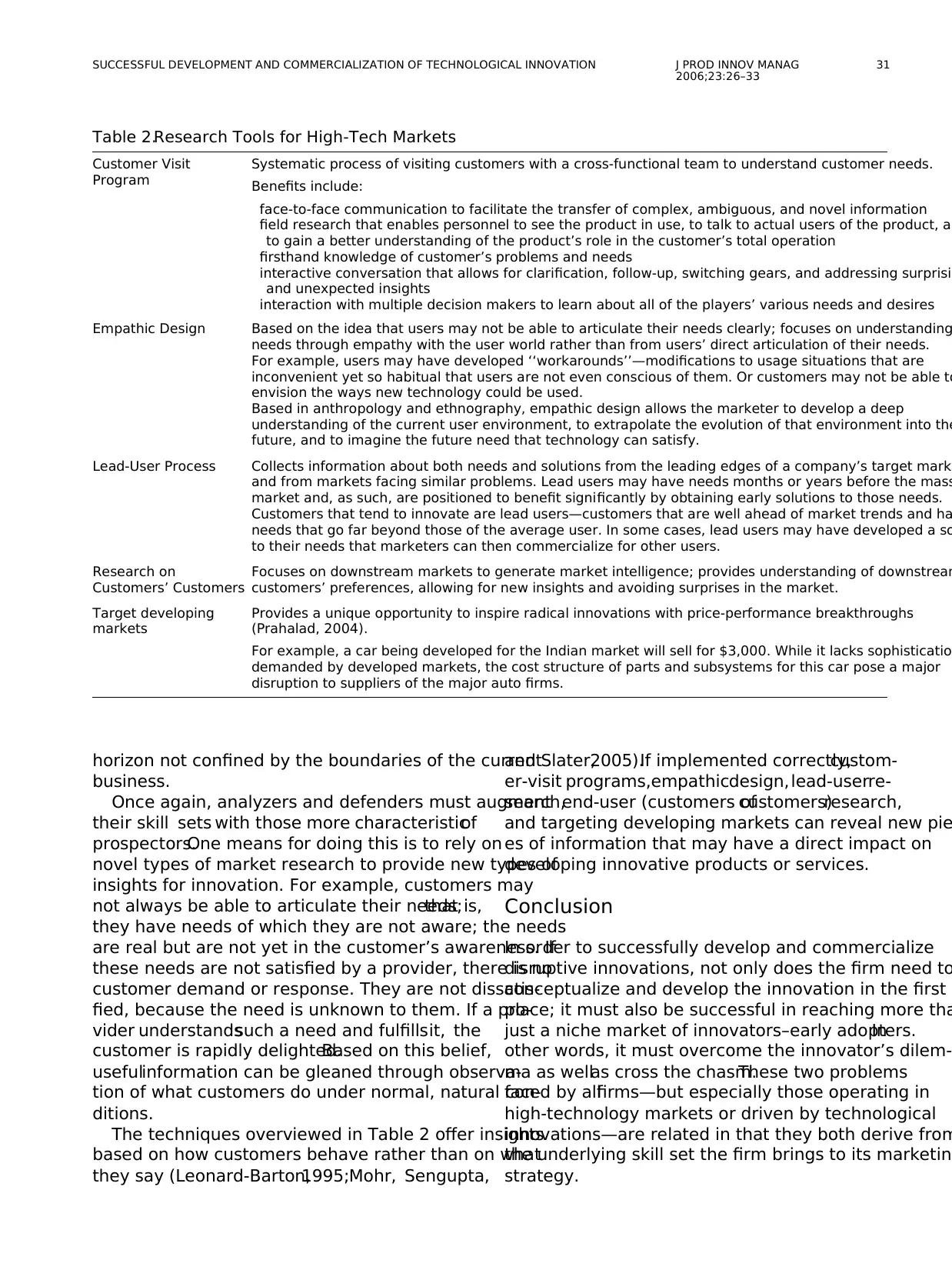

The techniques overviewed in Table 2 offer insights

based on how customers behave rather than on what

they say (Leonard-Barton,1995;Mohr, Sengupta,

and Slater,2005).If implemented correctly,custom-

er-visit programs,empathicdesign,lead-userre-

search,end-user (customers ofcustomers)research,

and targeting developing markets can reveal new pie

es of information that may have a direct impact on

developing innovative products or services.

Conclusion

In order to successfully develop and commercialize

disruptive innovations, not only does the firm need to

conceptualize and develop the innovation in the first

place; it must also be successful in reaching more tha

just a niche market of innovators–early adopters.In

other words, it must overcome the innovator’s dilem-

ma as wellas cross the chasm.These two problems

faced by allfirms—but especially those operating in

high-technology markets or driven by technological

innovations—are related in that they both derive from

the underlying skill set the firm brings to its marketin

strategy.

Table 2.Research Tools for High-Tech Markets

Customer Visit

Program

Systematic process of visiting customers with a cross-functional team to understand customer needs.

Benefits include:

face-to-face communication to facilitate the transfer of complex, ambiguous, and novel information

field research that enables personnel to see the product in use, to talk to actual users of the product, an

to gain a better understanding of the product’s role in the customer’s total operation

firsthand knowledge of customer’s problems and needs

interactive conversation that allows for clarification, follow-up, switching gears, and addressing surprisin

and unexpected insights

interaction with multiple decision makers to learn about all of the players’ various needs and desires

Empathic Design Based on the idea that users may not be able to articulate their needs clearly; focuses on understanding

needs through empathy with the user world rather than from users’ direct articulation of their needs.

For example, users may have developed ‘‘workarounds’’—modifications to usage situations that are

inconvenient yet so habitual that users are not even conscious of them. Or customers may not be able to

envision the ways new technology could be used.

Based in anthropology and ethnography, empathic design allows the marketer to develop a deep

understanding of the current user environment, to extrapolate the evolution of that environment into the

future, and to imagine the future need that technology can satisfy.

Lead-User Process Collects information about both needs and solutions from the leading edges of a company’s target marke

and from markets facing similar problems. Lead users may have needs months or years before the mass

market and, as such, are positioned to benefit significantly by obtaining early solutions to those needs.

Customers that tend to innovate are lead users—customers that are well ahead of market trends and ha

needs that go far beyond those of the average user. In some cases, lead users may have developed a so

to their needs that marketers can then commercialize for other users.

Research on

Customers’ Customers

Focuses on downstream markets to generate market intelligence; provides understanding of downstream

customers’ preferences, allowing for new insights and avoiding surprises in the market.

Target developing

markets

Provides a unique opportunity to inspire radical innovations with price-performance breakthroughs

(Prahalad, 2004).

For example, a car being developed for the Indian market will sell for $3,000. While it lacks sophisticatio

demanded by developed markets, the cost structure of parts and subsystems for this car pose a major

disruption to suppliers of the major auto firms.

SUCCESSFUL DEVELOPMENT AND COMMERCIALIZATION OF TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION J PROD INNOV MANAG

2006;23:26–33

31

business.

Once again, analyzers and defenders must augment

their skill sets with those more characteristicof

prospectors.One means for doing this is to rely on

novel types of market research to provide new types of

insights for innovation. For example, customers may

not always be able to articulate their needs;that is,

they have needs of which they are not aware; the needs

are real but are not yet in the customer’s awareness. If

these needs are not satisfied by a provider, there is no

customer demand or response. They are not dissatis-

fied, because the need is unknown to them. If a pro-

vider understandssuch a need and fulfillsit, the

customer is rapidly delighted.Based on this belief,

usefulinformation can be gleaned through observa-

tion of what customers do under normal, natural con-

ditions.

The techniques overviewed in Table 2 offer insights

based on how customers behave rather than on what

they say (Leonard-Barton,1995;Mohr, Sengupta,

and Slater,2005).If implemented correctly,custom-

er-visit programs,empathicdesign,lead-userre-

search,end-user (customers ofcustomers)research,

and targeting developing markets can reveal new pie

es of information that may have a direct impact on

developing innovative products or services.

Conclusion

In order to successfully develop and commercialize

disruptive innovations, not only does the firm need to

conceptualize and develop the innovation in the first

place; it must also be successful in reaching more tha

just a niche market of innovators–early adopters.In

other words, it must overcome the innovator’s dilem-

ma as wellas cross the chasm.These two problems

faced by allfirms—but especially those operating in

high-technology markets or driven by technological

innovations—are related in that they both derive from

the underlying skill set the firm brings to its marketin

strategy.

Table 2.Research Tools for High-Tech Markets

Customer Visit

Program

Systematic process of visiting customers with a cross-functional team to understand customer needs.

Benefits include:

face-to-face communication to facilitate the transfer of complex, ambiguous, and novel information

field research that enables personnel to see the product in use, to talk to actual users of the product, an

to gain a better understanding of the product’s role in the customer’s total operation

firsthand knowledge of customer’s problems and needs

interactive conversation that allows for clarification, follow-up, switching gears, and addressing surprisin

and unexpected insights

interaction with multiple decision makers to learn about all of the players’ various needs and desires

Empathic Design Based on the idea that users may not be able to articulate their needs clearly; focuses on understanding

needs through empathy with the user world rather than from users’ direct articulation of their needs.

For example, users may have developed ‘‘workarounds’’—modifications to usage situations that are

inconvenient yet so habitual that users are not even conscious of them. Or customers may not be able to

envision the ways new technology could be used.

Based in anthropology and ethnography, empathic design allows the marketer to develop a deep

understanding of the current user environment, to extrapolate the evolution of that environment into the

future, and to imagine the future need that technology can satisfy.

Lead-User Process Collects information about both needs and solutions from the leading edges of a company’s target marke

and from markets facing similar problems. Lead users may have needs months or years before the mass

market and, as such, are positioned to benefit significantly by obtaining early solutions to those needs.

Customers that tend to innovate are lead users—customers that are well ahead of market trends and ha

needs that go far beyond those of the average user. In some cases, lead users may have developed a so

to their needs that marketers can then commercialize for other users.

Research on

Customers’ Customers

Focuses on downstream markets to generate market intelligence; provides understanding of downstream

customers’ preferences, allowing for new insights and avoiding surprises in the market.

Target developing

markets

Provides a unique opportunity to inspire radical innovations with price-performance breakthroughs

(Prahalad, 2004).

For example, a car being developed for the Indian market will sell for $3,000. While it lacks sophisticatio

demanded by developed markets, the cost structure of parts and subsystems for this car pose a major

disruption to suppliers of the major auto firms.

SUCCESSFUL DEVELOPMENT AND COMMERCIALIZATION OF TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION J PROD INNOV MANAG

2006;23:26–33

31

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Firms typically become industry leaders (analyzers,

defenders) by appealing to a broad base of customers

in the marketplace (i.e., the mainstream market) and

by continually meeting their needs for value over time.

These firms are able to develop sustaining innovations

based on customerinput to continually hold their

position of marketleadership.But, paradoxically,

thesevery skills put them at risk of being out-

innovated by industry newcomers.

The root causesof the innovator’s dilemma are

the tyranny of the served market and core rigidities

most common to analyzerand defenderfirms.To

solve the innovator’sdilemma,a firm must attack

the rootcauses ofthe dilemma by developing new

ways of looking at the world developing proactive

marketlearning competencies such asthe ones we

described.

On the other hand,based on their ability to see

opportunity from a fresh perspective,industry new-

comers—or prospectors—are able to develop disrup-

tive innovationsthat appealto emergingmarket

segments and to eventually supersede prior industry

leaders. Whether or not these industry newcomers are

able to successfully establish themselves in any indus-

try depends critically on their ability to augment their

skill set with the capabilities to serve mainstream cus-

tomers as well. To penetrate the mainstream market,

prospectors must expand their focus from the inno-

vator and early-majority segments and must demon-

strate clear advantage over existing solutions (Rogers,

1995).They mustdevelop distribution systems that

reach the mainstream market and offer their products

at a lower price to reduce the financial risk associated

with adopting the innovation (Slaterand Olson,

2001).Not every prospectorcan develop analyzer-

like marketing capabilities,nor should they.Often,

it makes more sense for the prospector to ally with

another organization already possessingthese

capabilities.

Blending the insights from marketstrategy with

those from innovation managementmay illuminate

why some firms succeed with disruptive innovations

and others do not. Importantly, augmenting a firm’s

capabilities based on other strategy types can be crit-

ical to ongoing success.

References

Atuahene-Gima,Kwaku (1995).An Exploratory Analysis of the Im-

pact of Market Orientation on New Product Performance. Journal

of Product Innovation Management 12(4):275–293.

Atuahene-Gima, Kwaku, Slater, Stanley F. and Olson, Eric M. (2005).

The ContingentValue of Responsiveand Proactive Market

Orientations for New ProductProgram Performance.Journal of

Product Innovation Management 22(6):464–482.

Chandy,Rajesh and Tellis,Gerard (2000).The Incumbent’s Curse?

Incumbency,Size, and Radical Product Innovation.Journal of

Marketing 64(3):1–17.

Christensen, Clayton M. (1997). The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New

Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Boston: Harvard Business

School Press.

Christensen, Clayton M. and Bower, Joseph (1996). Customer Power,

Strategic Investment, and the Failure of Leading Firms. Strategic

Management Journal 17(3):197–218.

Christensen, Clayton M. and Raynor, Michael E. (2003). The Innova-

tor’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth. Boston:

Harvard Business School Press.

Christensen, Clayton M., Scott, Anthony and Roth, Erik (2004). See-

ing What’s Next: Using Theories of Innovation to Predict Industry

Change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Conant,Jeffrey S.,Mokwa, Michael P. and Varadarajan,P. Rajan

(1990). Strategic Types, Distinctive Marketing Competencies,and

OrganizationalPerformance:A Multiple Measures-Based Study.

Strategic Management Journal 11(5):365–383.

Danneels,Erwin (2004). DisruptiveTechnologyReconsidered:A

Critique and Research Agenda.Journal of Product Innovation

Management 21(4):246–258.

DeSarbo, Wayne, C., Di Benedetto, Anthony, Song, Michael and Sin-

ha, Indrajit (2005). Revisiting the Miles and Snow Strategic Frame-

work: Uncovering InterrelationshipsbetweenStrategictypes,

Capabilities,EnvironmentalUncertainty,and Firm Performance.

Strategic Management Journal 26(1):47–74.

Goldenberg, Jacob, Libai, Barak and Muller, Eitan (2002). Riding the

Saddle:How Cross-Market Communication Can Create a Major

Slump in Sales. Journal of Marketing 66(2):1–16.

Govindarajan,Vijay and Kopalle,Praveen (2004).Can Incumbents

Introduce Radicaland Disruptive Innovations?Working Paper

#04-001. Marketing Science, Cambridge, MA.

Hambrick,Don (2003).On the Staying Power of Miles and Snow’s

Defenders,Analyzers,and Prospectors.Academy of Management

Executive 17(4):115–118.

Hamel, Gary and Prahalad, C.K. (1991). Corporate Imagination and

Expeditionary Marketing. Harvard Business Review 69(4):81–92.

Hamel,Gary and Prahalad,C.K. (1994).Competing for the Future.

Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Kohli, Ajay and Jaworski,Bernard (1990).Market Orientation:The

Construct,Research Propositions,and ManagerialImplications.

Journal of Marketing 57(3):53–70.

Leonard-Barton, Dorothy (1992). Core Capabilities and Core Rigidi-

ties: A Paradox in Managing New Product Development. Strategic

Management Journal 13(6):111–125.

Leonard-Barton,Dorothy (1995).Wellsprings of Knowledge.Boston:

Harvard Business School Press.

Mahajan, Vijay, Muller, Eitan and Bass, Frank (1990). New Product

Diffusion Models in Marketing: A Review and Directions for Re-

search. Journal of Marketing 54(1):1–26.

Matsuno,Ken and Mentzer,John T. (2000).The Effects of Strategy

Type on the Market Orientation-Performance Relationship.Jour-

nal of Marketing 64(4):1–16.

Miles, Robert E. and Snow, Charles C. (1978). Organizational, Strat-

egy, Structure, and Process. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Mohr, Jakki, Sengupta,Sanjit and Slater,Stanley (2005).Marketing

High Technology Products and Innovations.Englewood Cliffs,NJ:

Prentice-Hall.

Moore, Geoffrey (1991, 2002). Crossing the Chasm. New York: Harp-

erBusiness.

32 J PROD INNOV MANAG

2006;23:26–33

S. F. SLATER AND J. J. MOHR

defenders) by appealing to a broad base of customers

in the marketplace (i.e., the mainstream market) and

by continually meeting their needs for value over time.

These firms are able to develop sustaining innovations

based on customerinput to continually hold their

position of marketleadership.But, paradoxically,

thesevery skills put them at risk of being out-

innovated by industry newcomers.

The root causesof the innovator’s dilemma are

the tyranny of the served market and core rigidities

most common to analyzerand defenderfirms.To

solve the innovator’sdilemma,a firm must attack

the rootcauses ofthe dilemma by developing new

ways of looking at the world developing proactive

marketlearning competencies such asthe ones we

described.

On the other hand,based on their ability to see

opportunity from a fresh perspective,industry new-

comers—or prospectors—are able to develop disrup-

tive innovationsthat appealto emergingmarket

segments and to eventually supersede prior industry

leaders. Whether or not these industry newcomers are

able to successfully establish themselves in any indus-

try depends critically on their ability to augment their

skill set with the capabilities to serve mainstream cus-

tomers as well. To penetrate the mainstream market,

prospectors must expand their focus from the inno-

vator and early-majority segments and must demon-

strate clear advantage over existing solutions (Rogers,

1995).They mustdevelop distribution systems that

reach the mainstream market and offer their products

at a lower price to reduce the financial risk associated

with adopting the innovation (Slaterand Olson,

2001).Not every prospectorcan develop analyzer-

like marketing capabilities,nor should they.Often,

it makes more sense for the prospector to ally with

another organization already possessingthese

capabilities.

Blending the insights from marketstrategy with

those from innovation managementmay illuminate

why some firms succeed with disruptive innovations

and others do not. Importantly, augmenting a firm’s

capabilities based on other strategy types can be crit-

ical to ongoing success.

References

Atuahene-Gima,Kwaku (1995).An Exploratory Analysis of the Im-

pact of Market Orientation on New Product Performance. Journal

of Product Innovation Management 12(4):275–293.

Atuahene-Gima, Kwaku, Slater, Stanley F. and Olson, Eric M. (2005).

The ContingentValue of Responsiveand Proactive Market

Orientations for New ProductProgram Performance.Journal of

Product Innovation Management 22(6):464–482.

Chandy,Rajesh and Tellis,Gerard (2000).The Incumbent’s Curse?

Incumbency,Size, and Radical Product Innovation.Journal of

Marketing 64(3):1–17.

Christensen, Clayton M. (1997). The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New

Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Boston: Harvard Business

School Press.

Christensen, Clayton M. and Bower, Joseph (1996). Customer Power,

Strategic Investment, and the Failure of Leading Firms. Strategic

Management Journal 17(3):197–218.

Christensen, Clayton M. and Raynor, Michael E. (2003). The Innova-

tor’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth. Boston:

Harvard Business School Press.

Christensen, Clayton M., Scott, Anthony and Roth, Erik (2004). See-

ing What’s Next: Using Theories of Innovation to Predict Industry

Change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Conant,Jeffrey S.,Mokwa, Michael P. and Varadarajan,P. Rajan

(1990). Strategic Types, Distinctive Marketing Competencies,and

OrganizationalPerformance:A Multiple Measures-Based Study.

Strategic Management Journal 11(5):365–383.

Danneels,Erwin (2004). DisruptiveTechnologyReconsidered:A

Critique and Research Agenda.Journal of Product Innovation

Management 21(4):246–258.

DeSarbo, Wayne, C., Di Benedetto, Anthony, Song, Michael and Sin-

ha, Indrajit (2005). Revisiting the Miles and Snow Strategic Frame-

work: Uncovering InterrelationshipsbetweenStrategictypes,

Capabilities,EnvironmentalUncertainty,and Firm Performance.

Strategic Management Journal 26(1):47–74.

Goldenberg, Jacob, Libai, Barak and Muller, Eitan (2002). Riding the

Saddle:How Cross-Market Communication Can Create a Major

Slump in Sales. Journal of Marketing 66(2):1–16.

Govindarajan,Vijay and Kopalle,Praveen (2004).Can Incumbents

Introduce Radicaland Disruptive Innovations?Working Paper

#04-001. Marketing Science, Cambridge, MA.

Hambrick,Don (2003).On the Staying Power of Miles and Snow’s

Defenders,Analyzers,and Prospectors.Academy of Management

Executive 17(4):115–118.

Hamel, Gary and Prahalad, C.K. (1991). Corporate Imagination and

Expeditionary Marketing. Harvard Business Review 69(4):81–92.

Hamel,Gary and Prahalad,C.K. (1994).Competing for the Future.

Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Kohli, Ajay and Jaworski,Bernard (1990).Market Orientation:The

Construct,Research Propositions,and ManagerialImplications.

Journal of Marketing 57(3):53–70.

Leonard-Barton, Dorothy (1992). Core Capabilities and Core Rigidi-

ties: A Paradox in Managing New Product Development. Strategic

Management Journal 13(6):111–125.

Leonard-Barton,Dorothy (1995).Wellsprings of Knowledge.Boston:

Harvard Business School Press.

Mahajan, Vijay, Muller, Eitan and Bass, Frank (1990). New Product

Diffusion Models in Marketing: A Review and Directions for Re-

search. Journal of Marketing 54(1):1–26.

Matsuno,Ken and Mentzer,John T. (2000).The Effects of Strategy

Type on the Market Orientation-Performance Relationship.Jour-

nal of Marketing 64(4):1–16.

Miles, Robert E. and Snow, Charles C. (1978). Organizational, Strat-

egy, Structure, and Process. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Mohr, Jakki, Sengupta,Sanjit and Slater,Stanley (2005).Marketing

High Technology Products and Innovations.Englewood Cliffs,NJ:

Prentice-Hall.

Moore, Geoffrey (1991, 2002). Crossing the Chasm. New York: Harp-

erBusiness.

32 J PROD INNOV MANAG

2006;23:26–33

S. F. SLATER AND J. J. MOHR

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Narver, John C. and Slater, Stanley F. (1990). The Effect of a Market

Orientation on BusinessProfitability. Journal of Marketing

57(4):20–35.

Narver, John C., Slater,Stanley F. and MacLachlan,DouglasL.

(2004).Responsive and Proactive MarketOrientation,and New

Product Success.Journal of Product InnovationManagement

21(5):334–347.

Olson, Eric M., Slater, Stanley F. and Hult, G. Tomas M. (2005). The

Performance Implications of Fitamong Business Strategy,Mar-

keting Organization Structure,and Strategic Behavior.Journalof

Marketing 69(3):49–65.

Prahalad,C. K. (2004).Why Selling to the Poor Makes for Good

Business. Fortune 150(10):70–72.

Rogers, Everett (1995). The Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed. New York:

Free Press.

Shanklin,William and Ryans,John (1987).Essentials ofMarketing

High Technology. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Slater, Stanley F., Hult, G.Tomas M. and Olson, Eric M. (2005). Key

Success Factors in High-Tech Markets. Working Paper. Colorado

State University.

Slater,Stanley F. and Narver,John C. (1998).Customer-Led and

Market-Oriented:Let’s Not Confuse the Two.Strategic Manage-

ment Journal 19(10):1001–1006.

Slater, Stanley F. and Olson, Eric M. (2001). Marketing’s Contribution

to the Implementation of Business Strategy: An Empirical Analysis.

Strategic Management Journal 22(11):1055–1068.

Vorhies,Douglas W.and Morgan,Neil A. (2003).A Configuration

Theory Assessment of Marketing Organization Fit with Business

Strategy and Its Relationship with Market Performance. Journal of

Marketing 67(1):100–115.

SUCCESSFUL DEVELOPMENT AND COMMERCIALIZATION OF TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION J PROD INNOV MANAG

2006;23:26–33

33

Orientation on BusinessProfitability. Journal of Marketing

57(4):20–35.

Narver, John C., Slater,Stanley F. and MacLachlan,DouglasL.

(2004).Responsive and Proactive MarketOrientation,and New

Product Success.Journal of Product InnovationManagement

21(5):334–347.

Olson, Eric M., Slater, Stanley F. and Hult, G. Tomas M. (2005). The

Performance Implications of Fitamong Business Strategy,Mar-

keting Organization Structure,and Strategic Behavior.Journalof

Marketing 69(3):49–65.

Prahalad,C. K. (2004).Why Selling to the Poor Makes for Good

Business. Fortune 150(10):70–72.

Rogers, Everett (1995). The Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed. New York:

Free Press.

Shanklin,William and Ryans,John (1987).Essentials ofMarketing

High Technology. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Slater, Stanley F., Hult, G.Tomas M. and Olson, Eric M. (2005). Key

Success Factors in High-Tech Markets. Working Paper. Colorado

State University.

Slater,Stanley F. and Narver,John C. (1998).Customer-Led and

Market-Oriented:Let’s Not Confuse the Two.Strategic Manage-

ment Journal 19(10):1001–1006.

Slater, Stanley F. and Olson, Eric M. (2001). Marketing’s Contribution

to the Implementation of Business Strategy: An Empirical Analysis.

Strategic Management Journal 22(11):1055–1068.