Technological Innovation: Sources, Problems, and Competitive Advantage

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/25

|15

|11163

|34

Report

AI Summary

This report delves into the sources of technological innovation, examining how firms develop radical and incremental innovations to sustain a competitive advantage. The study focuses on a conceptual framework of problem-driven innovation, using the pharmaceutical industry, specifically groundbreaking drugs for lung cancer treatment, as a case study. The research suggests that the coevolution of consequential problems and their solutions drives the emergence of radical innovations. Firms are incentivized to find innovative solutions to unsolved problems to achieve a temporary profit monopoly. The report positions this analysis within existing frameworks, reviewing approaches like induced innovations, evolutionary theory, and path-dependent development. The core argument centers on how relevant problems/needs induce problem-solving activities, leading to both incremental and radical innovations. The framework highlights the importance of problem-solving in R&D labs for competitive advantage and technological change in a Schumpeterian world. The research concludes with a hypothesis that relevant problems support new technological paradigms, which induce the development of these innovations over time. The report underscores the high mortality rate of lung cancer as a major unsolved problem that has driven the development of innovative anticancer treatments.

Technology Analysis & Strategic Manageme

ISSN: 0953-7325 (Print) 1465-3990 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandf

Sources of technological innovation: Ra

incremental innovation problem-driven

competitive advantage of firms

Mario Coccia

To cite this article: Mario Coccia (2016): Sources of technological innovation:

incremental innovation problem-driven to support competitive advantage of firm

Analysis & Strategic Management, DOI: 10.1080/09537325.2016.1268682

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2016.1268682

Published online: 29 Dec 2016.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 2

View related articles

View Crossmark data

ISSN: 0953-7325 (Print) 1465-3990 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandf

Sources of technological innovation: Ra

incremental innovation problem-driven

competitive advantage of firms

Mario Coccia

To cite this article: Mario Coccia (2016): Sources of technological innovation:

incremental innovation problem-driven to support competitive advantage of firm

Analysis & Strategic Management, DOI: 10.1080/09537325.2016.1268682

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2016.1268682

Published online: 29 Dec 2016.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 2

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Sources of technological innovation:Radical and incremental

innovation problem-driven to support competitive advantage of

firms

Mario Coccia

Arizona State University & CNR – NationalResearch Councilof Italy,Tempe,AZ 85287,USA

ABSTRACT

A fundamentalproblem in the field of management of technology is how

firms develop radicaland incrementalinnovationsthat sustainthe

competitive advantage in markets.Currentframeworksprovide some

explanations butthe generalsources ofmajorand minortechnological

breakthroughs are hardly known.The study here confronts this problem

by developing a conceptualframework of problem-driven innovation.The

inductive studyof the pharmaceuticalindustry(focusing on ground-

breaking drugs for lung cancertreatment)seems to show thatthe co-

evolution ofconsequentialproblemsand their solutionsinducethe

emergence and development ofradicalinnovations.In fact,firms have a

strong incentive to find innovative solutions to unsolved problems in order

to achieve the prospect of a (temporary) profit monopoly and competitive

advantage in marketscharacterised bytechnologicaldynamisms.The

theoreticalframework of this study can be generalised to explain one of

the sourcesof innovation thatsupportstechnologicaland industrial

change in a Schumpeterian world of innovation-based competition.

ARTICLE HISTORY

Received 15 January 2016

Revised 6 September 2016

Accepted 28 November 2016

KEYWORDS

Radicalinnovation;problem

solving;sources of

innovation;innovation

management;technological

paradigm;technological

trajectory

JEL CLASSIFICATION

O31;O39;I19

Overview of the problem

This article has two goals.The first is to develop a theoretical framework,which explains one of the

sources of radicaland incrementalinnovations.The second is to stress the importance of problem-

solving activity in R&D labsof firms for developing innovationsand supporting competitive

advantage.

These topics are basic in the field of the economics of innovation and management of techn

to explain the competitive advantage offirms in markets with technologicaldynamisms (Coccia

2009b, 2010c, 2014b; Tushman and Anderson 1986; Nicholson, Rees, and Brooks-Rooney 199

tensen 1997; Garud et al. 2015). In fact, a main question in these research fields is how firms

and sustain radicaland incrementalinnovations for competitive advantage in markets (cf.Coccia

2016a;Teece,Pisano,and Shuen 1997;von Hippel1988).The study here confronts this question

by developing the approach ofproblem-driven innovation,which endeavours to explain one of

the sources of innovation in markets.As a matter of fact,this framework clarifies the understanding

of how firms generate innovative products/processes to supporttheircompetitive advantage in

markets with rapid change.This study can also provide results in both building a better theoretica

framework of the sources of technological innovation and informing best-practices of R&D ma

ment. In order to position this analysis in a manner that displays similarities and differences w

ing approaches,the study here begins by reviewing some frameworks of technologicalanalysis.

© 2016 Informa UK Limited,trading as Taylor & Francis Group

CONTACT Mario Cocciamario.coccia@cnr.it

TECHNOLOGY ANALYSIS & STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT,2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2016.1268682

innovation problem-driven to support competitive advantage of

firms

Mario Coccia

Arizona State University & CNR – NationalResearch Councilof Italy,Tempe,AZ 85287,USA

ABSTRACT

A fundamentalproblem in the field of management of technology is how

firms develop radicaland incrementalinnovationsthat sustainthe

competitive advantage in markets.Currentframeworksprovide some

explanations butthe generalsources ofmajorand minortechnological

breakthroughs are hardly known.The study here confronts this problem

by developing a conceptualframework of problem-driven innovation.The

inductive studyof the pharmaceuticalindustry(focusing on ground-

breaking drugs for lung cancertreatment)seems to show thatthe co-

evolution ofconsequentialproblemsand their solutionsinducethe

emergence and development ofradicalinnovations.In fact,firms have a

strong incentive to find innovative solutions to unsolved problems in order

to achieve the prospect of a (temporary) profit monopoly and competitive

advantage in marketscharacterised bytechnologicaldynamisms.The

theoreticalframework of this study can be generalised to explain one of

the sourcesof innovation thatsupportstechnologicaland industrial

change in a Schumpeterian world of innovation-based competition.

ARTICLE HISTORY

Received 15 January 2016

Revised 6 September 2016

Accepted 28 November 2016

KEYWORDS

Radicalinnovation;problem

solving;sources of

innovation;innovation

management;technological

paradigm;technological

trajectory

JEL CLASSIFICATION

O31;O39;I19

Overview of the problem

This article has two goals.The first is to develop a theoretical framework,which explains one of the

sources of radicaland incrementalinnovations.The second is to stress the importance of problem-

solving activity in R&D labsof firms for developing innovationsand supporting competitive

advantage.

These topics are basic in the field of the economics of innovation and management of techn

to explain the competitive advantage offirms in markets with technologicaldynamisms (Coccia

2009b, 2010c, 2014b; Tushman and Anderson 1986; Nicholson, Rees, and Brooks-Rooney 199

tensen 1997; Garud et al. 2015). In fact, a main question in these research fields is how firms

and sustain radicaland incrementalinnovations for competitive advantage in markets (cf.Coccia

2016a;Teece,Pisano,and Shuen 1997;von Hippel1988).The study here confronts this question

by developing the approach ofproblem-driven innovation,which endeavours to explain one of

the sources of innovation in markets.As a matter of fact,this framework clarifies the understanding

of how firms generate innovative products/processes to supporttheircompetitive advantage in

markets with rapid change.This study can also provide results in both building a better theoretica

framework of the sources of technological innovation and informing best-practices of R&D ma

ment. In order to position this analysis in a manner that displays similarities and differences w

ing approaches,the study here begins by reviewing some frameworks of technologicalanalysis.

© 2016 Informa UK Limited,trading as Taylor & Francis Group

CONTACT Mario Cocciamario.coccia@cnr.it

TECHNOLOGY ANALYSIS & STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT,2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2016.1268682

In general,innovation is driven by several concomitant determinants,and scholars of economics,

management oftechnology and related disciplines have described three principalapproaches of

technologicalchange:induced innovations,evolutionary theory oftechnologicalchange,and

path-dependent development of innovations (cf.Dixon 1997).The first approach of induced inno-

vationsshowsthat the demand-pullis an importantfactorfor supporting innovations.Hicks

argued that:‘A change in the relative prices of factors of production is itself a spur to innovation

and to inventions ofa particularkind – directed ateconomising the use ofa factorwhich has

become relatively expensive’(Hicks as quoted by Ruttan 1997,1521).

The second approach is the evolutionary theory of technological change,which abandons the dis-

tinction between factor substitutions and shifts in the production function (Nelson and Winter

This theoretical framework is based on (1) local search for technical innovations, organisationa

and learning processes,(2) imitation of the practices of firms,and (3) satisficing behaviour of firms.

Third approach is the path-dependence developmentof innovation thatconsiders a specific

sequence of micro-level historical events for the evolution of innovations: i.e. current choices

niques may influence the future characteristics oftechnology and knowledge over the long run

(Arthur 1989).Ruttan (1997,1524) argues that:

each of the three approaches to understanding the sources of technical change – induced technical change,

utionary theory,and path dependence – is approaching a dead end.Attempts to construct bridges linking the

separate approaches are now necessary to advance our understanding of the sources of technical change.

Severalstudies in management,to explain how firms achieve and sustain innovation,focus on the

concept of ambidexterity:firms simultaneously engage in exploratory and exploitative activities th

supportboth incrementaland radicalinnovations (cf.Coccia 2009b,2012e;Durisin and Todorova

2012;Lin and McDonough III2014;O’Reilly IIIand Tushman 2004,76,2008;Danneels 2006).Other

approaches argue that a stage-gate model can rationalise and structure the technological dev

of new products (Conforto and Amaral 2016;Cooper 1990).Wuest et al.(2014,33) claim that:

The basic idea of the stage gate model is to divide a process in different phases and create a quality gate a

points in order to secure that the targeted goals are reached before proceeding to the next process phase.The

quality gates represent decision points,which determine on the basis of the current status of the process if the

project is continued,adapted/revised or terminated.The development process cannot pass a gate when it does

not meet all set criteria.(cf.Cooper 2008)

Ambartsoumian et al.(2011) argue that the phases of a new product development process are diffi

cult to plan,especially when goals are not clearly defined (cf.Calabrese,Coccia,and Rolfo 2005;

Cavallo etal. 2014a,2014b;Cavallo,Ferrari,and Coccia 2015).Currenttheoreticalframeworks

analysedifferentcharacteristicsof patternsof technologicalinnovation,2 however,current

approaches in economics and management of technology have trouble explaining some deter

nants that foster incrementaland radicalinnovations in markets.In fact,the generaldriving force

of innovations at micro- and macro-levelis hardly known (Dixon 1997).

In this context,the study here addresses the following questions:What is a general driver of inno-

vations in markets? How firms achieve and sustain innovation? The study here confronts these

scribed questionsby developing aconceptualframeworkof problem-driven based on the

coevolution ofconsequentialproblems and problem-solving activity offirms.In particular,this

study endeavours to explain one of the contributing factors that supports the innovation of firm

in markets. Accordingly, this study does not display a new model of product development but

grative approach within current theoreticalframeworks that can clarify one of the sources of inno-

vations with R&D management implications.

Conceptual framework and working hypothesis

Usher (1954),using the theoretical framework of the Gestalt psychology,shows four main concepts

for explaining the evolution of technology:

2 M.COCCIA

management oftechnology and related disciplines have described three principalapproaches of

technologicalchange:induced innovations,evolutionary theory oftechnologicalchange,and

path-dependent development of innovations (cf.Dixon 1997).The first approach of induced inno-

vationsshowsthat the demand-pullis an importantfactorfor supporting innovations.Hicks

argued that:‘A change in the relative prices of factors of production is itself a spur to innovation

and to inventions ofa particularkind – directed ateconomising the use ofa factorwhich has

become relatively expensive’(Hicks as quoted by Ruttan 1997,1521).

The second approach is the evolutionary theory of technological change,which abandons the dis-

tinction between factor substitutions and shifts in the production function (Nelson and Winter

This theoretical framework is based on (1) local search for technical innovations, organisationa

and learning processes,(2) imitation of the practices of firms,and (3) satisficing behaviour of firms.

Third approach is the path-dependence developmentof innovation thatconsiders a specific

sequence of micro-level historical events for the evolution of innovations: i.e. current choices

niques may influence the future characteristics oftechnology and knowledge over the long run

(Arthur 1989).Ruttan (1997,1524) argues that:

each of the three approaches to understanding the sources of technical change – induced technical change,

utionary theory,and path dependence – is approaching a dead end.Attempts to construct bridges linking the

separate approaches are now necessary to advance our understanding of the sources of technical change.

Severalstudies in management,to explain how firms achieve and sustain innovation,focus on the

concept of ambidexterity:firms simultaneously engage in exploratory and exploitative activities th

supportboth incrementaland radicalinnovations (cf.Coccia 2009b,2012e;Durisin and Todorova

2012;Lin and McDonough III2014;O’Reilly IIIand Tushman 2004,76,2008;Danneels 2006).Other

approaches argue that a stage-gate model can rationalise and structure the technological dev

of new products (Conforto and Amaral 2016;Cooper 1990).Wuest et al.(2014,33) claim that:

The basic idea of the stage gate model is to divide a process in different phases and create a quality gate a

points in order to secure that the targeted goals are reached before proceeding to the next process phase.The

quality gates represent decision points,which determine on the basis of the current status of the process if the

project is continued,adapted/revised or terminated.The development process cannot pass a gate when it does

not meet all set criteria.(cf.Cooper 2008)

Ambartsoumian et al.(2011) argue that the phases of a new product development process are diffi

cult to plan,especially when goals are not clearly defined (cf.Calabrese,Coccia,and Rolfo 2005;

Cavallo etal. 2014a,2014b;Cavallo,Ferrari,and Coccia 2015).Currenttheoreticalframeworks

analysedifferentcharacteristicsof patternsof technologicalinnovation,2 however,current

approaches in economics and management of technology have trouble explaining some deter

nants that foster incrementaland radicalinnovations in markets.In fact,the generaldriving force

of innovations at micro- and macro-levelis hardly known (Dixon 1997).

In this context,the study here addresses the following questions:What is a general driver of inno-

vations in markets? How firms achieve and sustain innovation? The study here confronts these

scribed questionsby developing aconceptualframeworkof problem-driven based on the

coevolution ofconsequentialproblems and problem-solving activity offirms.In particular,this

study endeavours to explain one of the contributing factors that supports the innovation of firm

in markets. Accordingly, this study does not display a new model of product development but

grative approach within current theoreticalframeworks that can clarify one of the sources of inno-

vations with R&D management implications.

Conceptual framework and working hypothesis

Usher (1954),using the theoretical framework of the Gestalt psychology,shows four main concepts

for explaining the evolution of technology:

2 M.COCCIA

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

(1) Perception of the problem:an incomplete pattern in need of resolution is recognised.

(2) Setting stage:assimilation of data related to the problem.

(3) Act of insight:a mentalact finds a solution to the problem.

(4) Critical revision:overall exploration and revision of the problem and improvements by means

new acts of insight.

This theoretical framework focuses on acts of insight that solve technological problems. The

cations of Usher’s theory are the evolution of new technology with a vitalcumulative change.As a

matterof fact,specific technologicalinnovations are the outcome ofa specific problem-solving

activity in the developmentof a specifictechnology in a defined research/technologicalfield

(Coccia 2014c, 2014d, 2016a, 2016b). This conceptual background is important to underpin th

eticalframework here.

We suppose the existence of a relevant problem/need (unsolved) in society.Moreover,we con-

sider firms as purposefulsystems that have purposefulelements with a common purpose,such as

maximising the profit,supporting the market leadership,etc.(cf.Ackoff 1971).

The working hypothesis (HPθ) of the study here is:

HPθ :Relevant and consequentialproblems/needs of consumers induce problem solving activities of firms (by

learning processes and acts ofinsight)that generate incrementaland radicalinnovations in markets,ceteris

paribus.

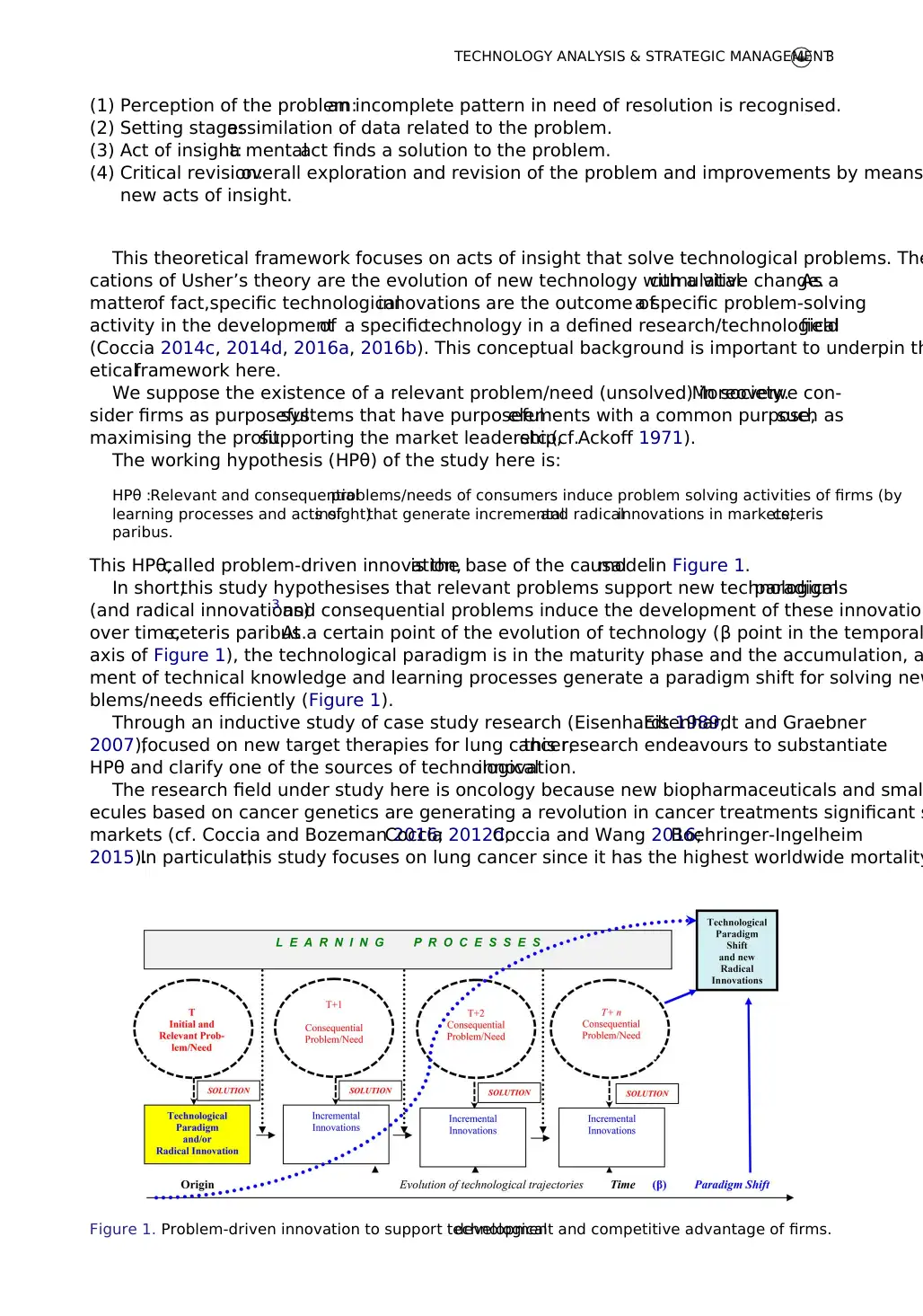

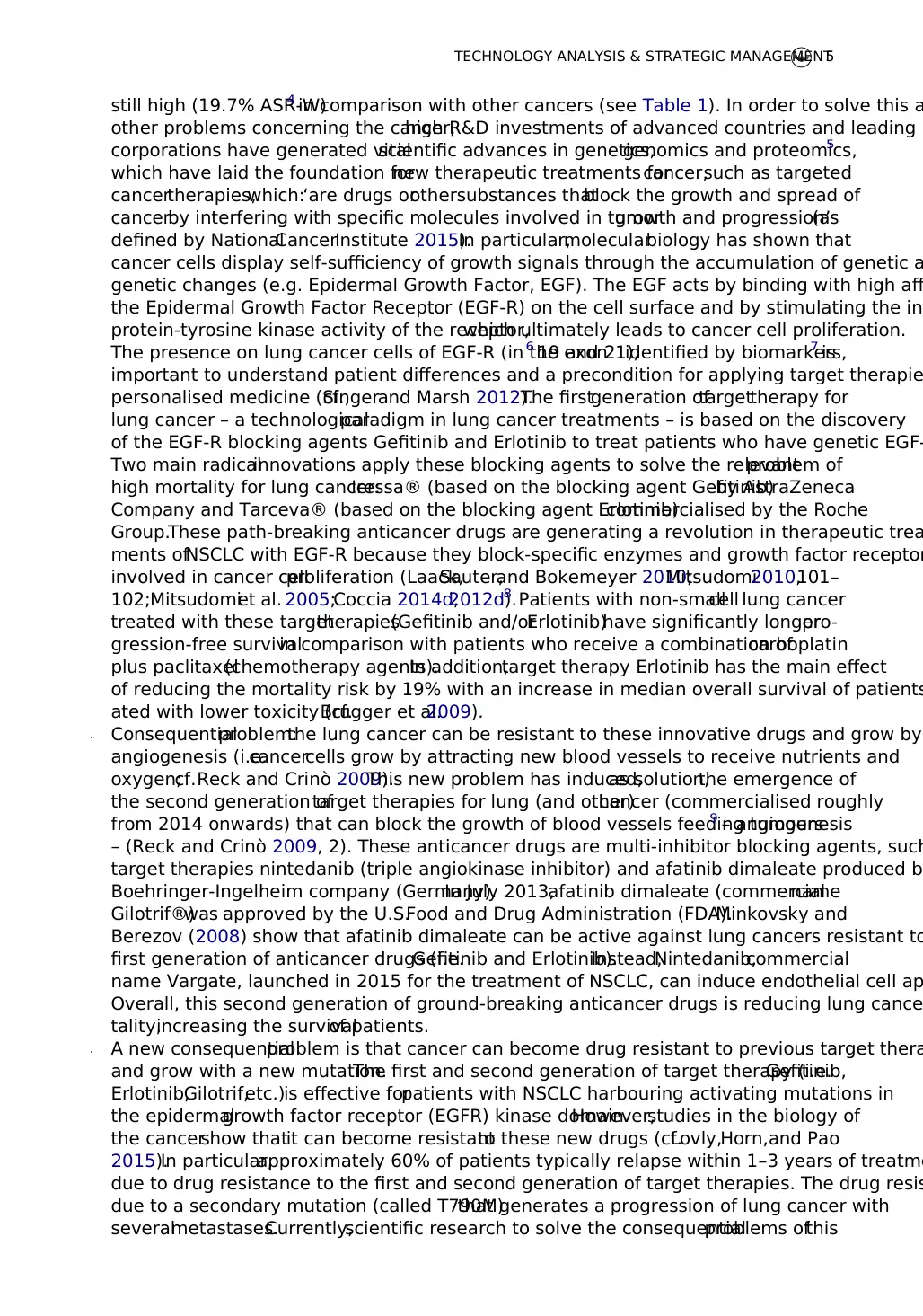

This HPθ,called problem-driven innovation,is the base of the causalmodelin Figure 1.

In short,this study hypothesises that relevant problems support new technologicalparadigms

(and radical innovations)3 and consequential problems induce the development of these innovation

over time,ceteris paribus.At a certain point of the evolution of technology (β point in the temporal

axis of Figure 1), the technological paradigm is in the maturity phase and the accumulation, a

ment of technical knowledge and learning processes generate a paradigm shift for solving new

blems/needs efficiently (Figure 1).

Through an inductive study of case study research (Eisenhardt 1989;Eisenhardt and Graebner

2007),focused on new target therapies for lung cancer,this research endeavours to substantiate

HPθ and clarify one of the sources of technologicalinnovation.

The research field under study here is oncology because new biopharmaceuticals and smal

ecules based on cancer genetics are generating a revolution in cancer treatments significant s

markets (cf. Coccia and Bozeman 2016;Coccia 2012d;Coccia and Wang 2016;Boehringer-Ingelheim

2015).In particular,this study focuses on lung cancer since it has the highest worldwide mortality

Figure 1. Problem-driven innovation to support technologicaldevelopment and competitive advantage of firms.

TECHNOLOGY ANALYSIS & STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT3

(2) Setting stage:assimilation of data related to the problem.

(3) Act of insight:a mentalact finds a solution to the problem.

(4) Critical revision:overall exploration and revision of the problem and improvements by means

new acts of insight.

This theoretical framework focuses on acts of insight that solve technological problems. The

cations of Usher’s theory are the evolution of new technology with a vitalcumulative change.As a

matterof fact,specific technologicalinnovations are the outcome ofa specific problem-solving

activity in the developmentof a specifictechnology in a defined research/technologicalfield

(Coccia 2014c, 2014d, 2016a, 2016b). This conceptual background is important to underpin th

eticalframework here.

We suppose the existence of a relevant problem/need (unsolved) in society.Moreover,we con-

sider firms as purposefulsystems that have purposefulelements with a common purpose,such as

maximising the profit,supporting the market leadership,etc.(cf.Ackoff 1971).

The working hypothesis (HPθ) of the study here is:

HPθ :Relevant and consequentialproblems/needs of consumers induce problem solving activities of firms (by

learning processes and acts ofinsight)that generate incrementaland radicalinnovations in markets,ceteris

paribus.

This HPθ,called problem-driven innovation,is the base of the causalmodelin Figure 1.

In short,this study hypothesises that relevant problems support new technologicalparadigms

(and radical innovations)3 and consequential problems induce the development of these innovation

over time,ceteris paribus.At a certain point of the evolution of technology (β point in the temporal

axis of Figure 1), the technological paradigm is in the maturity phase and the accumulation, a

ment of technical knowledge and learning processes generate a paradigm shift for solving new

blems/needs efficiently (Figure 1).

Through an inductive study of case study research (Eisenhardt 1989;Eisenhardt and Graebner

2007),focused on new target therapies for lung cancer,this research endeavours to substantiate

HPθ and clarify one of the sources of technologicalinnovation.

The research field under study here is oncology because new biopharmaceuticals and smal

ecules based on cancer genetics are generating a revolution in cancer treatments significant s

markets (cf. Coccia and Bozeman 2016;Coccia 2012d;Coccia and Wang 2016;Boehringer-Ingelheim

2015).In particular,this study focuses on lung cancer since it has the highest worldwide mortality

Figure 1. Problem-driven innovation to support technologicaldevelopment and competitive advantage of firms.

TECHNOLOGY ANALYSIS & STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT3

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

rates – for both sexes (cf.Ferlay et al.2013).This study assumes that the lung cancer is a relevant

problem and leading firms in the drug-discovery industry have a primary incentive to find solu

(with innovative and effective anticancer drugs) to this unsolved problem in order to achieve t

spect of a (temporary) profit monopoly in innovation-based markets.New consequentialproblems

and problem-solving activity can generate a main impetus for the development of innovations

markets of anticancer treatments (cf.Coccia 2012a,2012b,2013a,2014a,2014b).Expected evidence

of the inductive study here is to instantiate the HPθ.

Overall,then,the conceptualframework here seeks to explain one of the sources of radicaland

incrementalinnovations forcompetitive advantage offirms.It has also the potentialto explain

one of the generaland basic sources of the technologicalchange in regimes of rapid change.

Evidence to support the hypothesis

The high mortality rate of lung cancer is a major unsolved problem that has had a critical impe

for the development of innovative anticancer treatments.In order to substantiate the HPθ,case

study research here analyses the evolution oftargettherapies (vitalradicalinnovations)for

lung cancer.

. Firstly, as said above, high mortality of the lung cancer is a relevant problem (unsolved) in s

Irigaray et al. (2007) argue that the growing incidence of a variety of cancer in advanced co

is due to several factors such as ageing of the population, progress in health technology, expa

diagnostic and screening programmes,and in particular to the diffusion of environmentalcarcino-

gens (cf. Coccia 2015a; Obe et al. 2011). In fact, cancer incidence (the number of new cases o

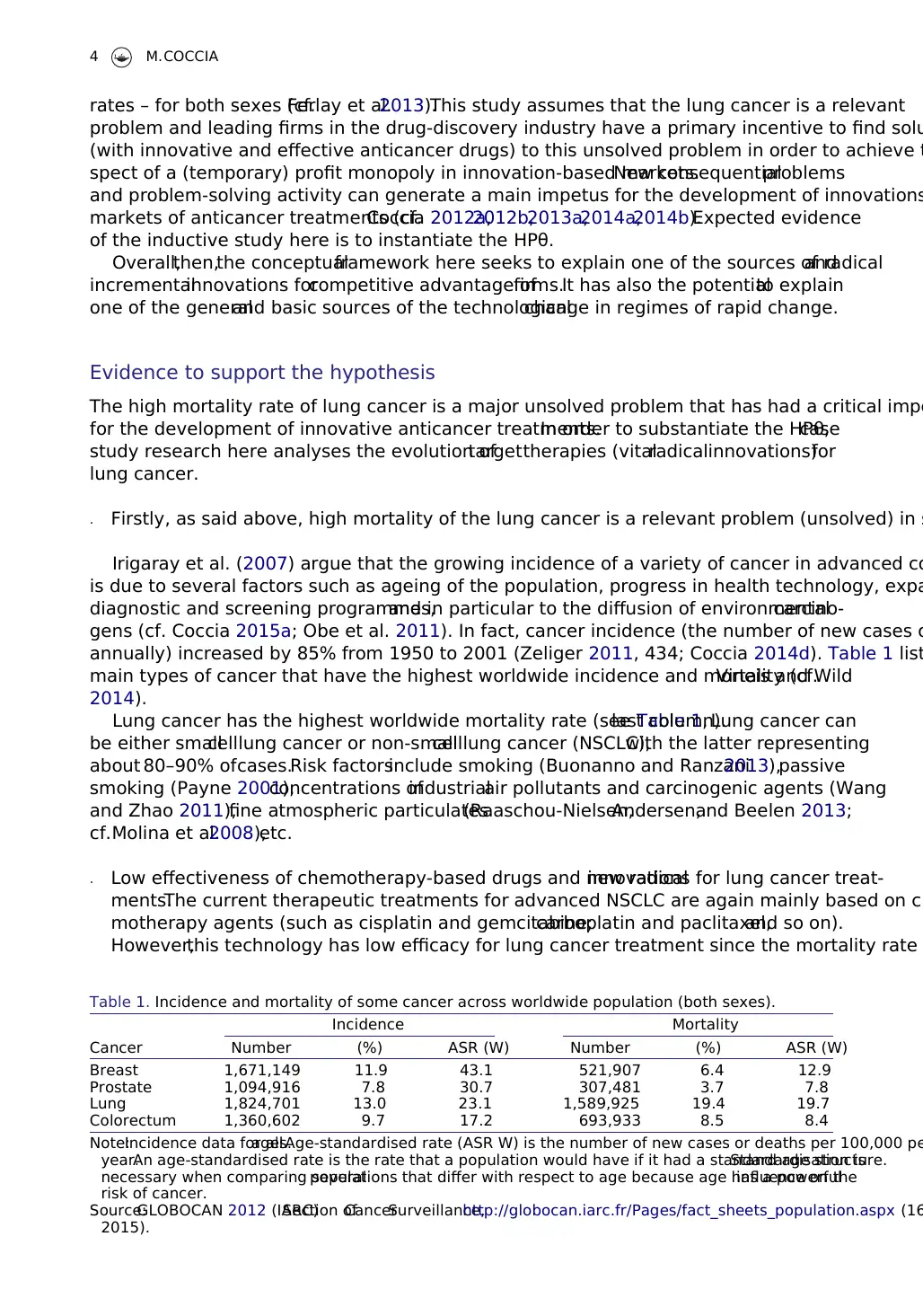

annually) increased by 85% from 1950 to 2001 (Zeliger 2011, 434; Coccia 2014d). Table 1 list

main types of cancer that have the highest worldwide incidence and mortality (cf.Vineis and Wild

2014).

Lung cancer has the highest worldwide mortality rate (see Table 1,last column).Lung cancer can

be either smallcelllung cancer or non-smallcelllung cancer (NSCLC),with the latter representing

about 80–90% ofcases.Risk factorsinclude smoking (Buonanno and Ranzani2013),passive

smoking (Payne 2001),concentrations ofindustrialair pollutants and carcinogenic agents (Wang

and Zhao 2011),fine atmospheric particulates(Raaschou-Nielsen,Andersen,and Beelen 2013;

cf.Molina et al.2008),etc.

. Low effectiveness of chemotherapy-based drugs and new radicalinnovations for lung cancer treat-

ments.The current therapeutic treatments for advanced NSCLC are again mainly based on ch

motherapy agents (such as cisplatin and gemcitabine;carboplatin and paclitaxel,and so on).

However,this technology has low efficacy for lung cancer treatment since the mortality rate

Table 1. Incidence and mortality of some cancer across worldwide population (both sexes).

Cancer

Incidence Mortality

Number (%) ASR (W) Number (%) ASR (W)

Breast 1,671,149 11.9 43.1 521,907 6.4 12.9

Prostate 1,094,916 7.8 30.7 307,481 3.7 7.8

Lung 1,824,701 13.0 23.1 1,589,925 19.4 19.7

Colorectum 1,360,602 9.7 17.2 693,933 8.5 8.4

Note:Incidence data for allages.Age-standardised rate (ASR W) is the number of new cases or deaths per 100,000 pe

year.An age-standardised rate is the rate that a population would have if it had a standard age structure.Standardisation is

necessary when comparing severalpopulations that differ with respect to age because age has a powerfulinfluence on the

risk of cancer.

Source:GLOBOCAN 2012 (IARC)Section ofCancerSurveillance,http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_population.aspx (16

2015).

4 M.COCCIA

problem and leading firms in the drug-discovery industry have a primary incentive to find solu

(with innovative and effective anticancer drugs) to this unsolved problem in order to achieve t

spect of a (temporary) profit monopoly in innovation-based markets.New consequentialproblems

and problem-solving activity can generate a main impetus for the development of innovations

markets of anticancer treatments (cf.Coccia 2012a,2012b,2013a,2014a,2014b).Expected evidence

of the inductive study here is to instantiate the HPθ.

Overall,then,the conceptualframework here seeks to explain one of the sources of radicaland

incrementalinnovations forcompetitive advantage offirms.It has also the potentialto explain

one of the generaland basic sources of the technologicalchange in regimes of rapid change.

Evidence to support the hypothesis

The high mortality rate of lung cancer is a major unsolved problem that has had a critical impe

for the development of innovative anticancer treatments.In order to substantiate the HPθ,case

study research here analyses the evolution oftargettherapies (vitalradicalinnovations)for

lung cancer.

. Firstly, as said above, high mortality of the lung cancer is a relevant problem (unsolved) in s

Irigaray et al. (2007) argue that the growing incidence of a variety of cancer in advanced co

is due to several factors such as ageing of the population, progress in health technology, expa

diagnostic and screening programmes,and in particular to the diffusion of environmentalcarcino-

gens (cf. Coccia 2015a; Obe et al. 2011). In fact, cancer incidence (the number of new cases o

annually) increased by 85% from 1950 to 2001 (Zeliger 2011, 434; Coccia 2014d). Table 1 list

main types of cancer that have the highest worldwide incidence and mortality (cf.Vineis and Wild

2014).

Lung cancer has the highest worldwide mortality rate (see Table 1,last column).Lung cancer can

be either smallcelllung cancer or non-smallcelllung cancer (NSCLC),with the latter representing

about 80–90% ofcases.Risk factorsinclude smoking (Buonanno and Ranzani2013),passive

smoking (Payne 2001),concentrations ofindustrialair pollutants and carcinogenic agents (Wang

and Zhao 2011),fine atmospheric particulates(Raaschou-Nielsen,Andersen,and Beelen 2013;

cf.Molina et al.2008),etc.

. Low effectiveness of chemotherapy-based drugs and new radicalinnovations for lung cancer treat-

ments.The current therapeutic treatments for advanced NSCLC are again mainly based on ch

motherapy agents (such as cisplatin and gemcitabine;carboplatin and paclitaxel,and so on).

However,this technology has low efficacy for lung cancer treatment since the mortality rate

Table 1. Incidence and mortality of some cancer across worldwide population (both sexes).

Cancer

Incidence Mortality

Number (%) ASR (W) Number (%) ASR (W)

Breast 1,671,149 11.9 43.1 521,907 6.4 12.9

Prostate 1,094,916 7.8 30.7 307,481 3.7 7.8

Lung 1,824,701 13.0 23.1 1,589,925 19.4 19.7

Colorectum 1,360,602 9.7 17.2 693,933 8.5 8.4

Note:Incidence data for allages.Age-standardised rate (ASR W) is the number of new cases or deaths per 100,000 pe

year.An age-standardised rate is the rate that a population would have if it had a standard age structure.Standardisation is

necessary when comparing severalpopulations that differ with respect to age because age has a powerfulinfluence on the

risk of cancer.

Source:GLOBOCAN 2012 (IARC)Section ofCancerSurveillance,http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_population.aspx (16

2015).

4 M.COCCIA

still high (19.7% ASR-W)4 in comparison with other cancers (see Table 1). In order to solve this a

other problems concerning the cancer,high R&D investments of advanced countries and leading

corporations have generated vitalscientific advances in genetics,genomics and proteomics,5

which have laid the foundation fornew therapeutic treatments forcancer,such as targeted

cancertherapies,which:‘are drugs orothersubstances thatblock the growth and spread of

cancerby interfering with specific molecules involved in tumorgrowth and progression’(as

defined by NationalCancerInstitute 2015).In particular,molecularbiology has shown that

cancer cells display self-sufficiency of growth signals through the accumulation of genetic a

genetic changes (e.g. Epidermal Growth Factor, EGF). The EGF acts by binding with high affi

the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGF-R) on the cell surface and by stimulating the in

protein-tyrosine kinase activity of the receptor,which ultimately leads to cancer cell proliferation.

The presence on lung cancer cells of EGF-R (in the exon6 19 and 21),identified by biomarkers,7 is

important to understand patient differences and a precondition for applying target therapie

personalised medicine (cf.,Singerand Marsh 2012).The firstgeneration oftargettherapy for

lung cancer – a technologicalparadigm in lung cancer treatments – is based on the discovery

of the EGF-R blocking agents Gefitinib and Erlotinib to treat patients who have genetic EGF-

Two main radicalinnovations apply these blocking agents to solve the relevantproblem of

high mortality for lung cancer:Iressa® (based on the blocking agent Gefitinib)by AstraZeneca

Company and Tarceva® (based on the blocking agent Erlotinib)commercialised by the Roche

Group.These path-breaking anticancer drugs are generating a revolution in therapeutic trea

ments ofNSCLC with EGF-R because they block-specific enzymes and growth factor receptor

involved in cancer cellproliferation (Laack,Sauter,and Bokemeyer 2010;Mitsudomi2010,101–

102;Mitsudomiet al. 2005;Coccia 2014d,2012d).8 Patients with non-smallcell lung cancer

treated with these targettherapies(Gefitinib and/orErlotinib)have significantly longerpro-

gression-free survivalin comparison with patients who receive a combination ofcarboplatin

plus paclitaxel(chemotherapy agents).In addition,target therapy Erlotinib has the main effect

of reducing the mortality risk by 19% with an increase in median overall survival of patients

ated with lower toxicity (cf.Brugger et al.2009).

. Consequentialproblem:the lung cancer can be resistant to these innovative drugs and grow by

angiogenesis (i.e.cancercells grow by attracting new blood vessels to receive nutrients and

oxygen;cf.Reck and Crinò 2009).This new problem has induced,as solution,the emergence of

the second generation oftarget therapies for lung (and other)cancer (commercialised roughly

from 2014 onwards) that can block the growth of blood vessels feeding tumours9 – angiogenesis

– (Reck and Crinò 2009, 2). These anticancer drugs are multi-inhibitor blocking agents, such

target therapies nintedanib (triple angiokinase inhibitor) and afatinib dimaleate produced b

Boehringer-Ingelheim company (Germany).In July 2013,afatinib dimaleate (commercialname

Gilotrif®)was approved by the U.S.Food and Drug Administration (FDA).Minkovsky and

Berezov (2008) show that afatinib dimaleate can be active against lung cancers resistant to

first generation of anticancer drugs (i.e.Gefitinib and Erlotinib).Instead,Nintedanib,commercial

name Vargate, launched in 2015 for the treatment of NSCLC, can induce endothelial cell ap

Overall, this second generation of ground-breaking anticancer drugs is reducing lung cance

tality,increasing the survivalof patients.

. A new consequentialproblem is that cancer can become drug resistant to previous target thera

and grow with a new mutation.The first and second generation of target therapy (i.e.Gefitinib,

Erlotinib,Gilotrif,etc.)is effective forpatients with NSCLC harbouring activating mutations in

the epidermalgrowth factor receptor (EGFR) kinase domain.However,studies in the biology of

the cancershow thatit can become resistantto these new drugs (cf.Lovly,Horn,and Pao

2015).In particular,approximately 60% of patients typically relapse within 1–3 years of treatme

due to drug resistance to the first and second generation of target therapies. The drug resis

due to a secondary mutation (called T790M)that generates a progression of lung cancer with

severalmetastases.Currently,scientific research to solve the consequentialproblems ofthis

TECHNOLOGY ANALYSIS & STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT5

other problems concerning the cancer,high R&D investments of advanced countries and leading

corporations have generated vitalscientific advances in genetics,genomics and proteomics,5

which have laid the foundation fornew therapeutic treatments forcancer,such as targeted

cancertherapies,which:‘are drugs orothersubstances thatblock the growth and spread of

cancerby interfering with specific molecules involved in tumorgrowth and progression’(as

defined by NationalCancerInstitute 2015).In particular,molecularbiology has shown that

cancer cells display self-sufficiency of growth signals through the accumulation of genetic a

genetic changes (e.g. Epidermal Growth Factor, EGF). The EGF acts by binding with high affi

the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGF-R) on the cell surface and by stimulating the in

protein-tyrosine kinase activity of the receptor,which ultimately leads to cancer cell proliferation.

The presence on lung cancer cells of EGF-R (in the exon6 19 and 21),identified by biomarkers,7 is

important to understand patient differences and a precondition for applying target therapie

personalised medicine (cf.,Singerand Marsh 2012).The firstgeneration oftargettherapy for

lung cancer – a technologicalparadigm in lung cancer treatments – is based on the discovery

of the EGF-R blocking agents Gefitinib and Erlotinib to treat patients who have genetic EGF-

Two main radicalinnovations apply these blocking agents to solve the relevantproblem of

high mortality for lung cancer:Iressa® (based on the blocking agent Gefitinib)by AstraZeneca

Company and Tarceva® (based on the blocking agent Erlotinib)commercialised by the Roche

Group.These path-breaking anticancer drugs are generating a revolution in therapeutic trea

ments ofNSCLC with EGF-R because they block-specific enzymes and growth factor receptor

involved in cancer cellproliferation (Laack,Sauter,and Bokemeyer 2010;Mitsudomi2010,101–

102;Mitsudomiet al. 2005;Coccia 2014d,2012d).8 Patients with non-smallcell lung cancer

treated with these targettherapies(Gefitinib and/orErlotinib)have significantly longerpro-

gression-free survivalin comparison with patients who receive a combination ofcarboplatin

plus paclitaxel(chemotherapy agents).In addition,target therapy Erlotinib has the main effect

of reducing the mortality risk by 19% with an increase in median overall survival of patients

ated with lower toxicity (cf.Brugger et al.2009).

. Consequentialproblem:the lung cancer can be resistant to these innovative drugs and grow by

angiogenesis (i.e.cancercells grow by attracting new blood vessels to receive nutrients and

oxygen;cf.Reck and Crinò 2009).This new problem has induced,as solution,the emergence of

the second generation oftarget therapies for lung (and other)cancer (commercialised roughly

from 2014 onwards) that can block the growth of blood vessels feeding tumours9 – angiogenesis

– (Reck and Crinò 2009, 2). These anticancer drugs are multi-inhibitor blocking agents, such

target therapies nintedanib (triple angiokinase inhibitor) and afatinib dimaleate produced b

Boehringer-Ingelheim company (Germany).In July 2013,afatinib dimaleate (commercialname

Gilotrif®)was approved by the U.S.Food and Drug Administration (FDA).Minkovsky and

Berezov (2008) show that afatinib dimaleate can be active against lung cancers resistant to

first generation of anticancer drugs (i.e.Gefitinib and Erlotinib).Instead,Nintedanib,commercial

name Vargate, launched in 2015 for the treatment of NSCLC, can induce endothelial cell ap

Overall, this second generation of ground-breaking anticancer drugs is reducing lung cance

tality,increasing the survivalof patients.

. A new consequentialproblem is that cancer can become drug resistant to previous target thera

and grow with a new mutation.The first and second generation of target therapy (i.e.Gefitinib,

Erlotinib,Gilotrif,etc.)is effective forpatients with NSCLC harbouring activating mutations in

the epidermalgrowth factor receptor (EGFR) kinase domain.However,studies in the biology of

the cancershow thatit can become resistantto these new drugs (cf.Lovly,Horn,and Pao

2015).In particular,approximately 60% of patients typically relapse within 1–3 years of treatme

due to drug resistance to the first and second generation of target therapies. The drug resis

due to a secondary mutation (called T790M)that generates a progression of lung cancer with

severalmetastases.Currently,scientific research to solve the consequentialproblems ofthis

TECHNOLOGY ANALYSIS & STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT5

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

secondary mutation is supporting the third generation of inhibitors of mutant lung cancer an

types of cancer (Clovis Oncology 2015).The first and second generation of target therapy is orig-

inally designed to targetwild-type EGFR,whereas new targettherapiesin lung cancerare

designed for EGFR-mutant lung cancer.Clovis Oncology (a smallUS bio-pharmaceuticalfirm) is

developing some of these new drugs such as Rociletinib for the treatment of mutant non-sm

cell lung cancer.In particular,Rociletinib is a novel,oral,targeted covalent (irreversible) inhibitor

to selectively target both the initial activating EGFR mutations and the T790M resistance m

with an improved toxicity profile.Accordingly,it has the potentialto be a first-line treatment in

NSCLC patients with activating EGFR mutations and a second or later-line treatment in NSC

patients who become resistant to previous therapies due to the emergence of the T790M se

ary mutation (Clovis Oncology 2014, 2015). The biopharmaceutical company (AstraZeneca

2015b) has generated a similar selective and irreversible inhibitor for mutant lung cancer: t

anticancer drug is called TAGRISSO™—osimertinib (AZD9291) and wasapproved by US FDA in

2015.

. Future technological trajectories in lung cancer treatments and the potential emergence of

logicalparadigm shift.New generation oftargettherapiestreatsEGFR-mutantlung cancer.

However,Thress et al.(2015,560) analyze the new anticancer therapy AZD9291 by AstraZeneca

for EGFR-mutant lung cancer (a sub type of non-smallcell lung cancer) and show new problems

that will affect the evolution of these innovative target therapies,that is:‘diversity of mechanisms

through which tumors acquire resistance to AZD9291 and highlight the need for therapies t

able to overcome resistance mediated by the EGFRC 797S mutation’.Moreover,cutting-edge

research is opening new scientific frontiers in treatments of oncology by developing therapi

based cancer-fighting viruses and T cells that can generate a technological paradigm shift i

ancer drugs (cf.Ledford 2015).

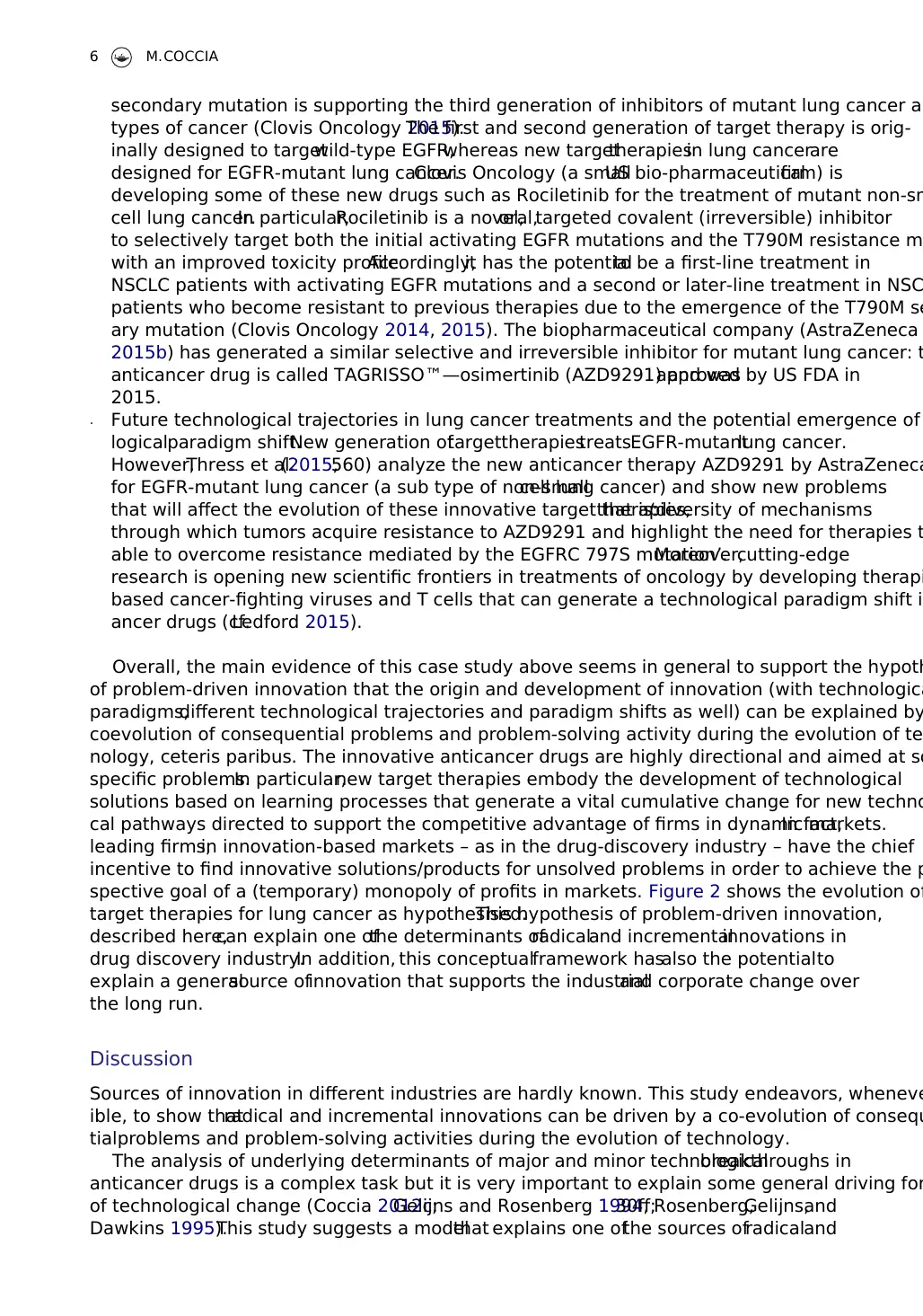

Overall, the main evidence of this case study above seems in general to support the hypoth

of problem-driven innovation that the origin and development of innovation (with technologica

paradigms,different technological trajectories and paradigm shifts as well) can be explained by

coevolution of consequential problems and problem-solving activity during the evolution of te

nology, ceteris paribus. The innovative anticancer drugs are highly directional and aimed at so

specific problems.In particular,new target therapies embody the development of technological

solutions based on learning processes that generate a vital cumulative change for new techno

cal pathways directed to support the competitive advantage of firms in dynamic markets.In fact,

leading firms,in innovation-based markets – as in the drug-discovery industry – have the chief

incentive to find innovative solutions/products for unsolved problems in order to achieve the p

spective goal of a (temporary) monopoly of profits in markets. Figure 2 shows the evolution of

target therapies for lung cancer as hypothesised.This hypothesis of problem-driven innovation,

described here,can explain one ofthe determinants ofradicaland incrementalinnovations in

drug discovery industry.In addition, this conceptualframework hasalso the potentialto

explain a generalsource ofinnovation that supports the industrialand corporate change over

the long run.

Discussion

Sources of innovation in different industries are hardly known. This study endeavors, wheneve

ible, to show thatradical and incremental innovations can be driven by a co-evolution of consequ

tialproblems and problem-solving activities during the evolution of technology.

The analysis of underlying determinants of major and minor technologicalbreakthroughs in

anticancer drugs is a complex task but it is very important to explain some general driving for

of technological change (Coccia 2012c;Gelijns and Rosenberg 1994,30ff;Rosenberg,Gelijns,and

Dawkins 1995).This study suggests a modelthat explains one ofthe sources ofradicaland

6 M.COCCIA

types of cancer (Clovis Oncology 2015).The first and second generation of target therapy is orig-

inally designed to targetwild-type EGFR,whereas new targettherapiesin lung cancerare

designed for EGFR-mutant lung cancer.Clovis Oncology (a smallUS bio-pharmaceuticalfirm) is

developing some of these new drugs such as Rociletinib for the treatment of mutant non-sm

cell lung cancer.In particular,Rociletinib is a novel,oral,targeted covalent (irreversible) inhibitor

to selectively target both the initial activating EGFR mutations and the T790M resistance m

with an improved toxicity profile.Accordingly,it has the potentialto be a first-line treatment in

NSCLC patients with activating EGFR mutations and a second or later-line treatment in NSC

patients who become resistant to previous therapies due to the emergence of the T790M se

ary mutation (Clovis Oncology 2014, 2015). The biopharmaceutical company (AstraZeneca

2015b) has generated a similar selective and irreversible inhibitor for mutant lung cancer: t

anticancer drug is called TAGRISSO™—osimertinib (AZD9291) and wasapproved by US FDA in

2015.

. Future technological trajectories in lung cancer treatments and the potential emergence of

logicalparadigm shift.New generation oftargettherapiestreatsEGFR-mutantlung cancer.

However,Thress et al.(2015,560) analyze the new anticancer therapy AZD9291 by AstraZeneca

for EGFR-mutant lung cancer (a sub type of non-smallcell lung cancer) and show new problems

that will affect the evolution of these innovative target therapies,that is:‘diversity of mechanisms

through which tumors acquire resistance to AZD9291 and highlight the need for therapies t

able to overcome resistance mediated by the EGFRC 797S mutation’.Moreover,cutting-edge

research is opening new scientific frontiers in treatments of oncology by developing therapi

based cancer-fighting viruses and T cells that can generate a technological paradigm shift i

ancer drugs (cf.Ledford 2015).

Overall, the main evidence of this case study above seems in general to support the hypoth

of problem-driven innovation that the origin and development of innovation (with technologica

paradigms,different technological trajectories and paradigm shifts as well) can be explained by

coevolution of consequential problems and problem-solving activity during the evolution of te

nology, ceteris paribus. The innovative anticancer drugs are highly directional and aimed at so

specific problems.In particular,new target therapies embody the development of technological

solutions based on learning processes that generate a vital cumulative change for new techno

cal pathways directed to support the competitive advantage of firms in dynamic markets.In fact,

leading firms,in innovation-based markets – as in the drug-discovery industry – have the chief

incentive to find innovative solutions/products for unsolved problems in order to achieve the p

spective goal of a (temporary) monopoly of profits in markets. Figure 2 shows the evolution of

target therapies for lung cancer as hypothesised.This hypothesis of problem-driven innovation,

described here,can explain one ofthe determinants ofradicaland incrementalinnovations in

drug discovery industry.In addition, this conceptualframework hasalso the potentialto

explain a generalsource ofinnovation that supports the industrialand corporate change over

the long run.

Discussion

Sources of innovation in different industries are hardly known. This study endeavors, wheneve

ible, to show thatradical and incremental innovations can be driven by a co-evolution of consequ

tialproblems and problem-solving activities during the evolution of technology.

The analysis of underlying determinants of major and minor technologicalbreakthroughs in

anticancer drugs is a complex task but it is very important to explain some general driving for

of technological change (Coccia 2012c;Gelijns and Rosenberg 1994,30ff;Rosenberg,Gelijns,and

Dawkins 1995).This study suggests a modelthat explains one ofthe sources ofradicaland

6 M.COCCIA

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

incrementalinnovations in competitive markets:the linkage between emergence ofrelevant/

consequentialproblems and their solution (i.e.coevolution of innovation with the evolution of

consequentialproblems).A principalcontribution of this article is the strategic role in firms of

an efficient and rapid problem-solving activity ofR&D labs.In fact,technicalcompetence and

problem-solving activity are crucialfor developing severalinnovationssince they translate

environmentaland organisationalinputs into valuable new products and processes for competi-

tive advantage in markets (cf.Atuahene-Gima and Wei2011,81–82).10 Simon (1962) argues that

the problems solving involves a process of trialand error.

The more difficult and novel the problem, the greater is likely to be the amount of trial and error required to

solution.At the same time,the trial and error is not completely random or blind;it is,in fact,rather highly selec-

tive … to see whether they represent progress toward the goal. Indications of progress spur further search i

same direction;lack of progress signals the abandonment of a line of search.Problem solving requires selective

trial and error.(Simon 1962,472)

The analysis here displays similarities and differences with some approaches.Unlike stage-gate

modelthat represents an approach for the product development process (Cooper 1990;cf.Wuest

et al.2014),the approach here explains a generaldeterminant of innovation,which can be due to

the interaction between relevant/consequential problems and related solutions during the evo

of technology. Moreover, the study here focuses on a technology development approach that

general goal of building new knowledge, whereas stage-gate model is rather a product develo

approach formarkets(Högman and Johannesson 2013).Hence,the approach here hasmain

elements of complementarity with established frameworks.Similarity of these approaches just men-

tioned is that both problem-driven framework here and stage-gate model support cooperationcol-

laboration and communication in organisations between stakeholders,managers and other experts

of a project/product/process.

Moreover,the theoretical framework of this study has the potential to be generalised for expl

ing sources of different innovations.Others studies in different industries can support the findings

here.Ruiz,Jain,and Grayson (2012,385ff) argue that new product development depends on accu-

rately identifying problems across consumers and the ‘problem-solving cycle’ is a key activity

totype-driven problem solving in heating products using information ofusers (Bogers and Horst

2014,744).Restuccia etal. (2015)analyse the industrialequipment and supply sectors and also

show that the concept of product-related problems is a vitalfactor for new product development

and based on the role of distributors that can support the innovation during the product life-cy

Figure 2.Modelof co-evolution of the technologicalparadigm of target therapy in lung cancer with consequentialproblems:

problem-driven innovations.

Note:Names of new drugs are underlined;in parentheses are the year/period of approvalby health authorities in the US/Europe.

TECHNOLOGY ANALYSIS & STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT7

consequentialproblems and their solution (i.e.coevolution of innovation with the evolution of

consequentialproblems).A principalcontribution of this article is the strategic role in firms of

an efficient and rapid problem-solving activity ofR&D labs.In fact,technicalcompetence and

problem-solving activity are crucialfor developing severalinnovationssince they translate

environmentaland organisationalinputs into valuable new products and processes for competi-

tive advantage in markets (cf.Atuahene-Gima and Wei2011,81–82).10 Simon (1962) argues that

the problems solving involves a process of trialand error.

The more difficult and novel the problem, the greater is likely to be the amount of trial and error required to

solution.At the same time,the trial and error is not completely random or blind;it is,in fact,rather highly selec-

tive … to see whether they represent progress toward the goal. Indications of progress spur further search i

same direction;lack of progress signals the abandonment of a line of search.Problem solving requires selective

trial and error.(Simon 1962,472)

The analysis here displays similarities and differences with some approaches.Unlike stage-gate

modelthat represents an approach for the product development process (Cooper 1990;cf.Wuest

et al.2014),the approach here explains a generaldeterminant of innovation,which can be due to

the interaction between relevant/consequential problems and related solutions during the evo

of technology. Moreover, the study here focuses on a technology development approach that

general goal of building new knowledge, whereas stage-gate model is rather a product develo

approach formarkets(Högman and Johannesson 2013).Hence,the approach here hasmain

elements of complementarity with established frameworks.Similarity of these approaches just men-

tioned is that both problem-driven framework here and stage-gate model support cooperationcol-

laboration and communication in organisations between stakeholders,managers and other experts

of a project/product/process.

Moreover,the theoretical framework of this study has the potential to be generalised for expl

ing sources of different innovations.Others studies in different industries can support the findings

here.Ruiz,Jain,and Grayson (2012,385ff) argue that new product development depends on accu-

rately identifying problems across consumers and the ‘problem-solving cycle’ is a key activity

totype-driven problem solving in heating products using information ofusers (Bogers and Horst

2014,744).Restuccia etal. (2015)analyse the industrialequipment and supply sectors and also

show that the concept of product-related problems is a vitalfactor for new product development

and based on the role of distributors that can support the innovation during the product life-cy

Figure 2.Modelof co-evolution of the technologicalparadigm of target therapy in lung cancer with consequentialproblems:

problem-driven innovations.

Note:Names of new drugs are underlined;in parentheses are the year/period of approvalby health authorities in the US/Europe.

TECHNOLOGY ANALYSIS & STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT7

management.Critical problem-solving activity is also present in the semiconductor industry and

associated with the main variable of speed because in this specific industry,expeditious problem

solving ofR&D lab is an importantperformance goalto supporttechnologicalinnovations with

short market life cycles (Appleyard, Brown, and Sattler 2006). Macher and Mowery (2003), in s

ductormanufacturing,also find thatthe allocation ofengineering resources to problem-solving

activities,associated with information technologyand scheduleproduction,influencesnew

process technologies and manufacturing performance (forpublic research labs cf.Coccia 2001a,

2003;Coccia and Rolfo,2002).

In general,problem-solving competence is an important factor to develop in R&D labs to sust

innovation and competitive advantage of firms.In particular,an efficient R&D management of firms

depends on the ability to speed up the activities of solving complex problems in the presence

environmentalturbulence (cf.Atuahene-Gima and Wei2011).In short,the approach ofproblem-

driven innovation here seems to be a comprehensive framework with the potentialof explaining

one of the generalsources of technicalchange over time and space.

However,innovations are due to manifold factors.For instance,the learning process between

clinicalresearch and clinicalpractice in drug discovery industry is also a vitalfactor that sup-

ports innovative products with the accumulation and advancement oftechnicalknowledge in

specific research fields (cf.Gelijns and Rosenberg 1995b,4ff; Gershon 1998;Kim and Nelson

2000;Morlacchiand Nelson 2011;Gelijns and Rosenberg 1995b,67).Anotherfactorfor the

developmentof innovation isthe dynamic capability:‘the firm’sability to integrate,build,

and reconfigure internaland externalcompetences to address rapidly changing environments’

(Teece,Pisano,and Shuen 1997,516;Helfat et al.2007,4; Coccia 2014b).Coccia (2016c) shows

that the technologicalevolution can be also due to technologicalparasitism and symbiotic

interaction between technologies.Innovations are also due to organisationallearning,which

is a strategic process forcompetitive advantage offirms (Vera and Crossan 2004).Moreover,

managers with strategic leadership play a vitalrole for innovation processes offirms because

they inspire others with theirvision,create excitementin groups and provide incentives for

achieving goals in competitive environments (Bass and Avolio 1990).Finally,new technology

can be also due to ‘inventive analogical transfer’from experience and solutions of consequential

problems in one knowledge field – source domain – to other fields – target domains (Kalogerak

Lüthje,and Herstatt 2010,418).

Concluding observations

The high mortality rate of lung cancer is a major unsolved problem that generates a main imp

firms in drug-discovery industry – characterised by technologicaland marketdynamisms – to

develop path-breaking innovations of anticancer drugs.The inductive study here seems in general

to support the hypothesis that sources of radical and incremental innovations can be also exp

by a coevolution between relevant/consequentialproblems and problem-solving activities during

the evolution oftechnology,ceteris paribus.These findings seem to be also confirmed by other

studies,such as Coccia and Wang (2015,155ff) show that:

the sharp increase of several technological trajectories of anticancer drugs applied by nanotechnology seem

be driven by high rates of mortality of some types of cancers (e.g.pancreatic and brain) in order to find more

effective anticancer therapies that increase the progression-free survivalof patients.

These ‘technological trajectories mortality driven’ are problem-driven by high mortality in pan

and brain cancer.In short,relevant and consequentialproblems seem to be a main and general

driving force for the evolution of innovation in several industries. In fact, Roche (2015), a mult

health-care company,claims that the research process has to find:‘innovative solutions for serious,

currently unsolved medicalproblems’.Hence,leading firms in the drug-discovery industry have a

main incentive to find innovative solutions/products forunsolved problems in orderto achieve

8 M.COCCIA

associated with the main variable of speed because in this specific industry,expeditious problem

solving ofR&D lab is an importantperformance goalto supporttechnologicalinnovations with

short market life cycles (Appleyard, Brown, and Sattler 2006). Macher and Mowery (2003), in s

ductormanufacturing,also find thatthe allocation ofengineering resources to problem-solving

activities,associated with information technologyand scheduleproduction,influencesnew

process technologies and manufacturing performance (forpublic research labs cf.Coccia 2001a,

2003;Coccia and Rolfo,2002).

In general,problem-solving competence is an important factor to develop in R&D labs to sust

innovation and competitive advantage of firms.In particular,an efficient R&D management of firms

depends on the ability to speed up the activities of solving complex problems in the presence

environmentalturbulence (cf.Atuahene-Gima and Wei2011).In short,the approach ofproblem-

driven innovation here seems to be a comprehensive framework with the potentialof explaining

one of the generalsources of technicalchange over time and space.

However,innovations are due to manifold factors.For instance,the learning process between

clinicalresearch and clinicalpractice in drug discovery industry is also a vitalfactor that sup-

ports innovative products with the accumulation and advancement oftechnicalknowledge in

specific research fields (cf.Gelijns and Rosenberg 1995b,4ff; Gershon 1998;Kim and Nelson

2000;Morlacchiand Nelson 2011;Gelijns and Rosenberg 1995b,67).Anotherfactorfor the

developmentof innovation isthe dynamic capability:‘the firm’sability to integrate,build,

and reconfigure internaland externalcompetences to address rapidly changing environments’

(Teece,Pisano,and Shuen 1997,516;Helfat et al.2007,4; Coccia 2014b).Coccia (2016c) shows

that the technologicalevolution can be also due to technologicalparasitism and symbiotic

interaction between technologies.Innovations are also due to organisationallearning,which

is a strategic process forcompetitive advantage offirms (Vera and Crossan 2004).Moreover,

managers with strategic leadership play a vitalrole for innovation processes offirms because

they inspire others with theirvision,create excitementin groups and provide incentives for

achieving goals in competitive environments (Bass and Avolio 1990).Finally,new technology

can be also due to ‘inventive analogical transfer’from experience and solutions of consequential

problems in one knowledge field – source domain – to other fields – target domains (Kalogerak

Lüthje,and Herstatt 2010,418).

Concluding observations

The high mortality rate of lung cancer is a major unsolved problem that generates a main imp

firms in drug-discovery industry – characterised by technologicaland marketdynamisms – to

develop path-breaking innovations of anticancer drugs.The inductive study here seems in general

to support the hypothesis that sources of radical and incremental innovations can be also exp

by a coevolution between relevant/consequentialproblems and problem-solving activities during

the evolution oftechnology,ceteris paribus.These findings seem to be also confirmed by other

studies,such as Coccia and Wang (2015,155ff) show that:

the sharp increase of several technological trajectories of anticancer drugs applied by nanotechnology seem

be driven by high rates of mortality of some types of cancers (e.g.pancreatic and brain) in order to find more

effective anticancer therapies that increase the progression-free survivalof patients.

These ‘technological trajectories mortality driven’ are problem-driven by high mortality in pan

and brain cancer.In short,relevant and consequentialproblems seem to be a main and general

driving force for the evolution of innovation in several industries. In fact, Roche (2015), a mult

health-care company,claims that the research process has to find:‘innovative solutions for serious,

currently unsolved medicalproblems’.Hence,leading firms in the drug-discovery industry have a

main incentive to find innovative solutions/products forunsolved problems in orderto achieve

8 M.COCCIA

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

the goal of a (temporary)profit monopolyin a Schumpeterian world ofinnovation-based

competition.

The hypothesis of problem-driven innovation can explain a criticaldriving force of severalinno-

vations in drug discovery industry and has also the potentialto explain one of the generalsources

of the technologicalchange.Overall,the conceptualframework here contributesto integrate

currentapproaches ofthe sources ofinnovation in economics and managementof technology

(Dixon 1997;Ruttan 1997;von Tunzelmann et al.2008).In particular,

(1) The conceptualframework assigns a centralrole to relevantproblems and theirsolution to

explain the emergence of path-breaking innovations that sustain the industrialchange;

(2) The conceptual framework here is able to explain the development of technological traject

by solutions of consequential problems of initial radical innovation, based on learning proc

and act of insights in R&D labs of firms;

(3) Finally,the conceptualframework here is also able to show the vitalfunction of the problem-

solving activity in the R&D management directed to solve problems that induces radicaland

incrementalinnovation for sustaining and safeguarding extant competitive advantage of firm

in environment characterised by technologicaland market dynamism.

Hence, the conceptual framework here, substantiated in drug discovery industry, has sever

ponents of generalisation that could easily be extended to explain the evolution of new techno

across several industries for supporting industrialand corporate change.

However, these results are of course tentative because this study provides a preliminary an

some sources of specific radical/incremental innovations in markets with high technological co

tition.In fact,identifying the determinants ofradicalinnovations in drug discovery industry is a

complex and problematic matter,since we know that other things are often not equal.To conclude,

this study shows that the co-evolution of consequentialproblems and problem solving activities in

R&D labs of firms can be a main source of innovation, but Wright (1997, 1562) properly claims

world of technologicalchange,bounded rationality is the rule.’

Notes

1. This research began in 2014 at the UNU-MERIT (The Netherlands) and is further developed in 2015 and 2

Arizona State University while Iam a visiting scholar funded by NationalResearch Councilof Italy.This paper

benefited from helpfulcomments and suggestions by Christopher S.Hayter and two anonymous referees.The

author declares that he has no relevant or materialfinancialinterests that relate to the research discussed in

this paper.

2. Cf.Coccia (2004,2014b,2014e,2006b,2010b,2015b,2015c,2016b) and Coccia,Finardi,and Margon (2012).

3. Dosi (1982, 152, original emphasis) posits that ‘“technological paradigm” as “model” and a “pattern” of

selected technologicalproblems based on selected principles derived from naturalsciences and on selected

material technologies’(cf.Dosi,1988).

4. Age-standardized rate (W) is the rate that a population would have if it had a standard age structure.Standard-

ization is necessary when comparing several populations that differ with respect to age because age has

fulinfluence on the risk of cancer (GLOBOCAN,2012,http://globocan.iarc.fr/ –accessed February 2015).

5. Cf.Afshar (2003) and Fraser and Pai(2014).For countries with high R&D investment,see Coccia (2005,2007,

2008a,2008b,2009c,2009d,2010a,2010c,2013b,2015b);Rolfo and Coccia (2005).

6. An exon is the portion of a gene that codes for amino acids.

7. ‘A characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processe

genic processes, or pharmacologic responses to therapeutic intervention’ (National Institute of Health, as

by Amir-Aslani and Mangematin 2010,204)

8. The literature is vast and not fully cited here,but a good list of references is found in Dempke,Sutob,and Reck

(2010,262–263,271–274) and Coccia (2012d,2014d).

9. The evolution of technological paradigms is also based on developing new technological trajectories by ‘

tive analogicaltransfer’from experience and solutions in one knowledge field—source domain e.g.a type of

cancer—to solve new problems in other fields -target domains e.g. other cancers (cf. Kalogerakis, Lüthje,

statt 2010,418).

TECHNOLOGY ANALYSIS & STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT9

competition.

The hypothesis of problem-driven innovation can explain a criticaldriving force of severalinno-

vations in drug discovery industry and has also the potentialto explain one of the generalsources

of the technologicalchange.Overall,the conceptualframework here contributesto integrate

currentapproaches ofthe sources ofinnovation in economics and managementof technology

(Dixon 1997;Ruttan 1997;von Tunzelmann et al.2008).In particular,

(1) The conceptualframework assigns a centralrole to relevantproblems and theirsolution to

explain the emergence of path-breaking innovations that sustain the industrialchange;

(2) The conceptual framework here is able to explain the development of technological traject

by solutions of consequential problems of initial radical innovation, based on learning proc

and act of insights in R&D labs of firms;

(3) Finally,the conceptualframework here is also able to show the vitalfunction of the problem-

solving activity in the R&D management directed to solve problems that induces radicaland

incrementalinnovation for sustaining and safeguarding extant competitive advantage of firm

in environment characterised by technologicaland market dynamism.

Hence, the conceptual framework here, substantiated in drug discovery industry, has sever

ponents of generalisation that could easily be extended to explain the evolution of new techno

across several industries for supporting industrialand corporate change.

However, these results are of course tentative because this study provides a preliminary an

some sources of specific radical/incremental innovations in markets with high technological co

tition.In fact,identifying the determinants ofradicalinnovations in drug discovery industry is a

complex and problematic matter,since we know that other things are often not equal.To conclude,

this study shows that the co-evolution of consequentialproblems and problem solving activities in

R&D labs of firms can be a main source of innovation, but Wright (1997, 1562) properly claims

world of technologicalchange,bounded rationality is the rule.’

Notes

1. This research began in 2014 at the UNU-MERIT (The Netherlands) and is further developed in 2015 and 2

Arizona State University while Iam a visiting scholar funded by NationalResearch Councilof Italy.This paper

benefited from helpfulcomments and suggestions by Christopher S.Hayter and two anonymous referees.The

author declares that he has no relevant or materialfinancialinterests that relate to the research discussed in

this paper.

2. Cf.Coccia (2004,2014b,2014e,2006b,2010b,2015b,2015c,2016b) and Coccia,Finardi,and Margon (2012).

3. Dosi (1982, 152, original emphasis) posits that ‘“technological paradigm” as “model” and a “pattern” of

selected technologicalproblems based on selected principles derived from naturalsciences and on selected

material technologies’(cf.Dosi,1988).

4. Age-standardized rate (W) is the rate that a population would have if it had a standard age structure.Standard-

ization is necessary when comparing several populations that differ with respect to age because age has

fulinfluence on the risk of cancer (GLOBOCAN,2012,http://globocan.iarc.fr/ –accessed February 2015).

5. Cf.Afshar (2003) and Fraser and Pai(2014).For countries with high R&D investment,see Coccia (2005,2007,

2008a,2008b,2009c,2009d,2010a,2010c,2013b,2015b);Rolfo and Coccia (2005).

6. An exon is the portion of a gene that codes for amino acids.

7. ‘A characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processe

genic processes, or pharmacologic responses to therapeutic intervention’ (National Institute of Health, as

by Amir-Aslani and Mangematin 2010,204)

8. The literature is vast and not fully cited here,but a good list of references is found in Dempke,Sutob,and Reck

(2010,262–263,271–274) and Coccia (2012d,2014d).

9. The evolution of technological paradigms is also based on developing new technological trajectories by ‘

tive analogicaltransfer’from experience and solutions in one knowledge field—source domain e.g.a type of

cancer—to solve new problems in other fields -target domains e.g. other cancers (cf. Kalogerakis, Lüthje,

statt 2010,418).

TECHNOLOGY ANALYSIS & STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT9

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10. Cf.also Coccia 2001b,2006a,2008,2009a,2009e;Coccia and Cadario 2014;Coccia and Rolfo 2007,2013;Coccia,

Falavigna, and Manello 2015; for public research labs see also Coccia 2001a, 2003; Coccia and Rolfo 199

Notes on contributor

Mario Coccia is a Senior researcher at the NationalResearch Councilof Italy and Visiting Scholar at the Arizona State

University (Center for social dynamics and complexity). He has been Research Fellow at the Max Planck Institu

omics,Visiting Professor at the Polytechnics of Torino and University of Piemonte Orientale (Italy).He has conducted

research work at the Georgia Institute of Technology,Yale University,United Nations University – MERIT,University of

Maryland,Bureau d’Économie Théorique et Appliquée,University of Toronto,RAND Corporations and University of Bie-

lefeld. He has written extensively more than 280 papers in economics of science and technology, R&D manage

related disciplines.

ORCID

Coccia Mario http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1957-6731

References

Ackoff,R.L.1971.“Towards a System of Systems Concepts.” Management Science 17 (11):661–671.

Afshar,M. 2003.“From Genes to Products:Innovations in Drug Discovery.” Drug Discovery Today 8 (9):392–394.

Ambartsoumian,V.,J. Dhaliwal,E.Lee,T.Meservy,and C.Zhang.2011.“Implementing Quality Gates Throughout the

Enterprise it Production Process.” Journalof Information Technology Management 22 XXII (1):28–38.

Amir-Aslani,A.,and V.Mangematin.2010.“The Future of Drug Discovery and Development:Shifting Emphasis Towards

Personalized Medicine.” Technology Forecasting & SocialChange 77 (2):203–217.

Appleyard,M. M.,C.Brown,and L.Sattler.2006.“An International Investigation of Problem-Solving Performance in the

Semiconductor Industry.” Journalof Product Innovation Management 23 (2):147–167.

Arthur, W. B. 1989. “Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-In by Historical Events.” The Econo

99 (394):116–131.

AstraZeneca.2015a.Accessed April,2015.http://www.astrazeneca.com/Research/areas-of-interest.

AstraZeneca.2015b.“Openinnovation.” Accessed October1. http://openinnovation.astrazeneca.com/what-we-offer/

compound/azd9291/.

Atuahene-Gima, K., and Y. Wei. 2011. “The Vital Role of Problem-Solving Competence in New Product Success.

Product Innovation Management 28 (1):81–98.

Bass, B. M., and B. J. Avolio. 1990. “The Implications of Transactional and Transformational Leadership for Indiv

and Organizational Development.” In Research in Organizational Change and Development, edited by B. M.

L.Cummings,4 Vols,231–272.Greenwich,CT:JAI Press.

Boehringer-Ingelheim.2015.Accessed April,2015.https://www.boehringer-ingelheim.com/research_development/

drug_discovery/drug_discovery_process.html.

Bogers, M., and W. Horst. 2014. “Collaborative Prototyping: Cross-Fertilization of Knowledge in Prototype-Drive