Analysis of Transfer Functions, Complex Numbers and Polynomial Fitting

VerifiedAdded on 2020/02/05

|20

|5953

|377

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This document presents a comprehensive solution to an electrical engineering assignment. The first part delves into the concept of transfer functions, explaining their role in determining system response characteristics, defining poles and zeros, and discussing the stability of systems based on the location of poles. It also explores the use of impulse response and absolute integrability to determine system stability. The second part examines complex numbers, their various forms (algebraic, trigonometric, and exponential), operations, and properties, including conjugates. It includes a practical example of converting a complex number to exponential form. The third part provides a step-by-step guide to polynomial fitting using MATLAB, demonstrating how to input data, use the polyfit function to fit a third-order polynomial, and evaluate the polynomial at data points. The assignment covers fundamental concepts in electrical engineering, including system analysis, complex numbers, and data fitting techniques.

Q.No:1

(A)

The transfer function provides a basis for determining important system response

characteristics

without solving the complete differential equation. As defined, the transfer function is a

rational

function in the complex variable s = σ + jω, that is

H(s) = bmsm + bm−1sm−1 + ... + b1s + b0

ansn + an−1sn−1 + ... + a1s + a0

(1)

It is often convenient to factor the polynomials in the numerator and denominator, and to write

the transfer function in terms of those factors:

H(s) = N(s)

D(s) = K (s − z1)(s − z2)...(s − zm−1)(s − zm)

(s − p1)(s − p2)...(s − pn−1)(s − pn)

, (2)

where the numerator and denominator polynomials, N(s) and D(s), have real coefficients

defined

by the system’s differential equation and K = bm/an. As written in Eq. (2) the zi’s are the roots

of the equation

N(s)=0, (3)

and are defined to be the system zeros, and the pi’s are the roots of the equation

D(s)=0, (4)

and are defined to be the system poles. In Eq. (2) the factors in the numerator and

denominator

are written so that when s = zi the numerator N(s) = 0 and the transfer function vanishes, that is

(A)

The transfer function provides a basis for determining important system response

characteristics

without solving the complete differential equation. As defined, the transfer function is a

rational

function in the complex variable s = σ + jω, that is

H(s) = bmsm + bm−1sm−1 + ... + b1s + b0

ansn + an−1sn−1 + ... + a1s + a0

(1)

It is often convenient to factor the polynomials in the numerator and denominator, and to write

the transfer function in terms of those factors:

H(s) = N(s)

D(s) = K (s − z1)(s − z2)...(s − zm−1)(s − zm)

(s − p1)(s − p2)...(s − pn−1)(s − pn)

, (2)

where the numerator and denominator polynomials, N(s) and D(s), have real coefficients

defined

by the system’s differential equation and K = bm/an. As written in Eq. (2) the zi’s are the roots

of the equation

N(s)=0, (3)

and are defined to be the system zeros, and the pi’s are the roots of the equation

D(s)=0, (4)

and are defined to be the system poles. In Eq. (2) the factors in the numerator and

denominator

are written so that when s = zi the numerator N(s) = 0 and the transfer function vanishes, that is

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

lims→zi

H(s)=0.

and similarly when s = pi the denominator polynomial D(s) = 0 and the value of the transfer

function becomes unbounded,

lims→pi

H(s) = ∞.

All of the coefficients of polynomials N(s) and D(s) are real, therefore the poles and zeros must

be either purely real, or appear in complex conjugate pairs. In general for the poles, either pi =

σi,

or else pi, pi+1 = σi±jωi. The existence of a single complex pole without a corresponding

conjugate

pole would generate complex coefficients in the polynomial D(s). Similarly, the system zeros are

either real or appear in complex conjugate pairs.

(B)

(i)

We wish to know if a system with transfer function

G(s) = 1 s + γ is stable. If γ < 0, let u(t)

= σ(t), the unit step function, which is obviously bounded.

Then, y(t) = L −1 [ 1 s (s + γ) ] = L −1 [ 1 γ ( 1 s − 1 s + γ )]

= 1 γ (1 − e −γt)σ(t), which goes to ∞ when t goes to ∞,

and hence is unbounded. This shows that the system is unstable.

If

γ = 0,

the system is called an integrator. Again let u(t)

= σ(t). Then, y(t) = L −1 [ 1 s 2 ]

= tσ(t), which goes to ∞ as t goes to ∞.

This shows that the system is again unstable.

H(s)=0.

and similarly when s = pi the denominator polynomial D(s) = 0 and the value of the transfer

function becomes unbounded,

lims→pi

H(s) = ∞.

All of the coefficients of polynomials N(s) and D(s) are real, therefore the poles and zeros must

be either purely real, or appear in complex conjugate pairs. In general for the poles, either pi =

σi,

or else pi, pi+1 = σi±jωi. The existence of a single complex pole without a corresponding

conjugate

pole would generate complex coefficients in the polynomial D(s). Similarly, the system zeros are

either real or appear in complex conjugate pairs.

(B)

(i)

We wish to know if a system with transfer function

G(s) = 1 s + γ is stable. If γ < 0, let u(t)

= σ(t), the unit step function, which is obviously bounded.

Then, y(t) = L −1 [ 1 s (s + γ) ] = L −1 [ 1 γ ( 1 s − 1 s + γ )]

= 1 γ (1 − e −γt)σ(t), which goes to ∞ when t goes to ∞,

and hence is unbounded. This shows that the system is unstable.

If

γ = 0,

the system is called an integrator. Again let u(t)

= σ(t). Then, y(t) = L −1 [ 1 s 2 ]

= tσ(t), which goes to ∞ as t goes to ∞.

This shows that the system is again unstable.

If γ > 0, the impulse response of G(s) is g(t)

= e −γtσ(t). Then, |y(t)|

= ∫ t 0 g(τ )u(t − τ )dτ ≤ ∫ t 0 |g(τ )||u(t − τ )|dτ. If |u(t)| ≤ M for all t ∈ [0, ∞),

then |y(t)| ≤ M ∫ ∞ 0 |g(τ )|dτ

= M ∫ ∞ 0 e −γτ dτ

= M γ . Hence, as long as u(t) is bounded by M, then y(t) is bounded by M/γ. This shows that the system

is stable. In summary, a system with transfer function G(s)

= 1 s + γ is stable if γ > 0 and is unstable if γ ≤ 0.

Using the procedure in the example to test the stability of a system is often tedious. We desire to have

a simple stability test.

An LTI system with impulse response function g(t) is stable if and only if ∫ ∞ 0 |g(t)|dt < ∞. (3.1) Proof .

Assume that the input u(t) is bounded by M; then |y(t)|

= ∫ t 0 g(τ )u(t − τ )dτ

≤ ∫ t 0 |g(τ )||u(t − τ )|dτ ≤ M ∫ ∞ 0 |g(τ )|dτ.

Stability and Stabilization If (3.1) is satisfied, choose N = M ∫ ∞ 0 |g(τ )|dτ , and then the input bounded

by M generates the output bounded by N; i.e.,

the system is stable. This shows the sufficiency. If (3.1) is not satisfied,

∫ ∞ 0 |g(t)|dt = ∞. For any M > 0, choose t0 so that ∫ t0 0 |g(τ )|dτ > M and choose u(t)

= { 1, if g(t0 − t) ≥ 0; −1, if g(t0 − t) < 0 for 0 ≤ t ≤ t0. Then, |y(t0)|

= ∫ t0 0 g(t0 − τ )u(τ )dτ

= ∫ t0 0 |g(t0 − τ )|dτ

= ∫ t0 0 |g(τ )|dτ > M.

This shows that for an input u(t) bounded by 1, the output can be arbitrarily large. Hence, the system is

not stable. This proves the necessity. A signal is said to be absolutely integrable over an interval if the

integral of the absolute value of the signal over the interval is finite. Hence, a linear system is stable if its

impulse response is absolutely integrable over [0, ∞). This theorem makes it a bit easier to check the

stability of a system.

(ii)

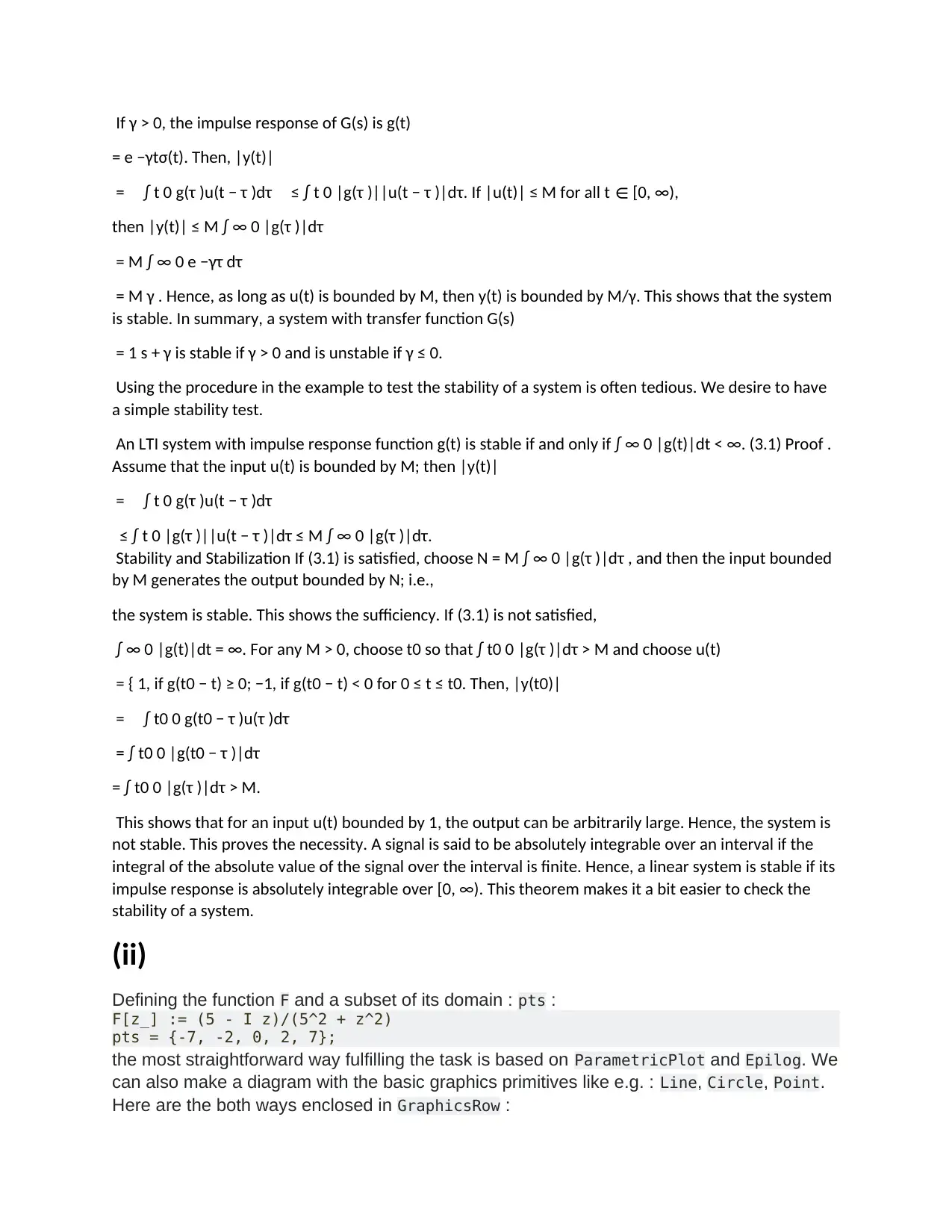

Defining the function F and a subset of its domain : pts :

F[z_] := (5 - I z)/(5^2 + z^2)

pts = {-7, -2, 0, 2, 7};

the most straightforward way fulfilling the task is based on ParametricPlot and Epilog. We

can also make a diagram with the basic graphics primitives like e.g. : Line, Circle, Point.

Here are the both ways enclosed in GraphicsRow :

= e −γtσ(t). Then, |y(t)|

= ∫ t 0 g(τ )u(t − τ )dτ ≤ ∫ t 0 |g(τ )||u(t − τ )|dτ. If |u(t)| ≤ M for all t ∈ [0, ∞),

then |y(t)| ≤ M ∫ ∞ 0 |g(τ )|dτ

= M ∫ ∞ 0 e −γτ dτ

= M γ . Hence, as long as u(t) is bounded by M, then y(t) is bounded by M/γ. This shows that the system

is stable. In summary, a system with transfer function G(s)

= 1 s + γ is stable if γ > 0 and is unstable if γ ≤ 0.

Using the procedure in the example to test the stability of a system is often tedious. We desire to have

a simple stability test.

An LTI system with impulse response function g(t) is stable if and only if ∫ ∞ 0 |g(t)|dt < ∞. (3.1) Proof .

Assume that the input u(t) is bounded by M; then |y(t)|

= ∫ t 0 g(τ )u(t − τ )dτ

≤ ∫ t 0 |g(τ )||u(t − τ )|dτ ≤ M ∫ ∞ 0 |g(τ )|dτ.

Stability and Stabilization If (3.1) is satisfied, choose N = M ∫ ∞ 0 |g(τ )|dτ , and then the input bounded

by M generates the output bounded by N; i.e.,

the system is stable. This shows the sufficiency. If (3.1) is not satisfied,

∫ ∞ 0 |g(t)|dt = ∞. For any M > 0, choose t0 so that ∫ t0 0 |g(τ )|dτ > M and choose u(t)

= { 1, if g(t0 − t) ≥ 0; −1, if g(t0 − t) < 0 for 0 ≤ t ≤ t0. Then, |y(t0)|

= ∫ t0 0 g(t0 − τ )u(τ )dτ

= ∫ t0 0 |g(t0 − τ )|dτ

= ∫ t0 0 |g(τ )|dτ > M.

This shows that for an input u(t) bounded by 1, the output can be arbitrarily large. Hence, the system is

not stable. This proves the necessity. A signal is said to be absolutely integrable over an interval if the

integral of the absolute value of the signal over the interval is finite. Hence, a linear system is stable if its

impulse response is absolutely integrable over [0, ∞). This theorem makes it a bit easier to check the

stability of a system.

(ii)

Defining the function F and a subset of its domain : pts :

F[z_] := (5 - I z)/(5^2 + z^2)

pts = {-7, -2, 0, 2, 7};

the most straightforward way fulfilling the task is based on ParametricPlot and Epilog. We

can also make a diagram with the basic graphics primitives like e.g. : Line, Circle, Point.

Here are the both ways enclosed in GraphicsRow :

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

GraphicsRow[{

Graphics[{Line[{{0, -0.1}, {0, 0.1}}], Line[{{0, 0}, {0.21, 0}}],

Blue, Thick, Circle[{0.1, 0}, 0.1],

Red, PointSize[.03], Point[{Re @ #, Im @ #} & /@ F[pts]]}],

ParametricPlot[{Re @ #, Im @ #}& @ F[z], {z, -200, 200}, PlotRange ->

All,

PlotStyle -> Thick, Epilog -> { Red, PointSize[0.03],

Point[{Re @ F @ #, Im @ F @ #} & /@ pts]}] }]

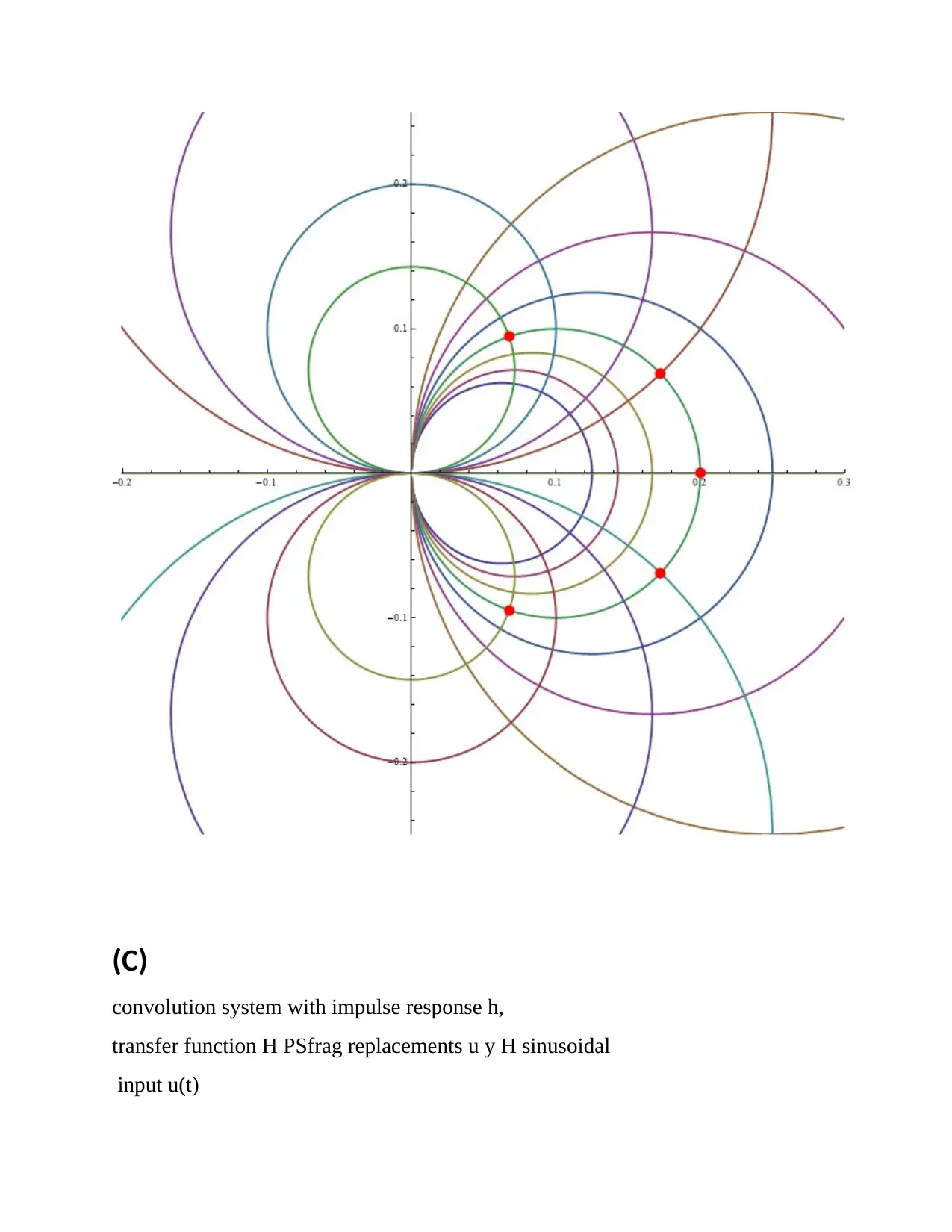

Studying properties of holomorphic complex mappings is really rewarding, therefore one

should take a closer look at it. This function has a simple pole in 5 I :

Residue[ F[z], {z, 5 I}]

-I

and it is conformal in its domain :

Reduce[ D[ F[z], z] == 0, z]

False

i.e. it preserves angles locally. One can easily recognize the type of F evaluating Simplify[

F[z]], namely it is a composition of a translation, rescaling and inversion. We should look

at images (via F) of simple geometric objects. To visualize the structure of the mapping F we

choose an appropriate grid in the complex domain of F and look at its image. We take a

continuous parameter $t$ varying in a range $(-25, 25)$ and contours $\;t+ i\;y $ for $y$ in a

discrete set of values $\{-3, -2,-1, 0, 1, 2, 3 \}$ and another orthogonal contours $\;x+ i\;t$

for $x$ in a discrete set $\{-7,-5,-3, -2, 0, 2, 3, 5, 5\;\}$, i.e.we have a grid of straight lines in

the complex plane. Next we'd like to plot the image of this grid through the mapping $F$.

Images of every line in the grid will be circles with centers on the abscissa and ordinate

respectively intersecting orthogonally. The red points denote values of $F(x)$ on the

complex plane for $x$ in $\{-7, -2, 0, 2, 7 \}$. On the lhs we have the original grid in the

domain of Fand on the rhs we have the plot of its image :

Graphics[{Line[{{0, -0.1}, {0, 0.1}}], Line[{{0, 0}, {0.21, 0}}],

Blue, Thick, Circle[{0.1, 0}, 0.1],

Red, PointSize[.03], Point[{Re @ #, Im @ #} & /@ F[pts]]}],

ParametricPlot[{Re @ #, Im @ #}& @ F[z], {z, -200, 200}, PlotRange ->

All,

PlotStyle -> Thick, Epilog -> { Red, PointSize[0.03],

Point[{Re @ F @ #, Im @ F @ #} & /@ pts]}] }]

Studying properties of holomorphic complex mappings is really rewarding, therefore one

should take a closer look at it. This function has a simple pole in 5 I :

Residue[ F[z], {z, 5 I}]

-I

and it is conformal in its domain :

Reduce[ D[ F[z], z] == 0, z]

False

i.e. it preserves angles locally. One can easily recognize the type of F evaluating Simplify[

F[z]], namely it is a composition of a translation, rescaling and inversion. We should look

at images (via F) of simple geometric objects. To visualize the structure of the mapping F we

choose an appropriate grid in the complex domain of F and look at its image. We take a

continuous parameter $t$ varying in a range $(-25, 25)$ and contours $\;t+ i\;y $ for $y$ in a

discrete set of values $\{-3, -2,-1, 0, 1, 2, 3 \}$ and another orthogonal contours $\;x+ i\;t$

for $x$ in a discrete set $\{-7,-5,-3, -2, 0, 2, 3, 5, 5\;\}$, i.e.we have a grid of straight lines in

the complex plane. Next we'd like to plot the image of this grid through the mapping $F$.

Images of every line in the grid will be circles with centers on the abscissa and ordinate

respectively intersecting orthogonally. The red points denote values of $F(x)$ on the

complex plane for $x$ in $\{-7, -2, 0, 2, 7 \}$. On the lhs we have the original grid in the

domain of Fand on the rhs we have the plot of its image :

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

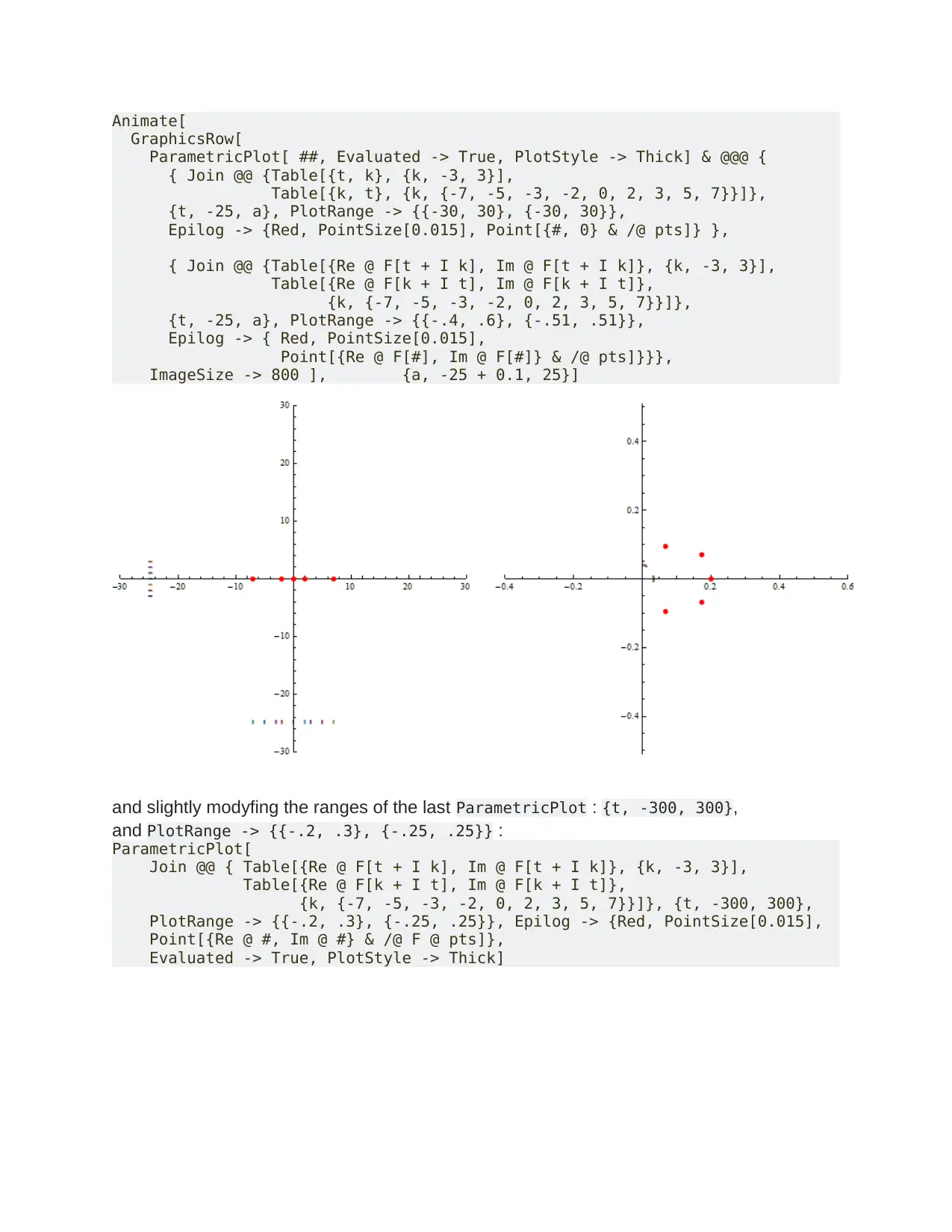

Animate[

GraphicsRow[

ParametricPlot[ ##, Evaluated -> True, PlotStyle -> Thick] & @@@ {

{ Join @@ {Table[{t, k}, {k, -3, 3}],

Table[{k, t}, {k, {-7, -5, -3, -2, 0, 2, 3, 5, 7}}]},

{t, -25, a}, PlotRange -> {{-30, 30}, {-30, 30}},

Epilog -> {Red, PointSize[0.015], Point[{#, 0} & /@ pts]} },

{ Join @@ {Table[{Re @ F[t + I k], Im @ F[t + I k]}, {k, -3, 3}],

Table[{Re @ F[k + I t], Im @ F[k + I t]},

{k, {-7, -5, -3, -2, 0, 2, 3, 5, 7}}]},

{t, -25, a}, PlotRange -> {{-.4, .6}, {-.51, .51}},

Epilog -> { Red, PointSize[0.015],

Point[{Re @ F[#], Im @ F[#]} & /@ pts]}}},

ImageSize -> 800 ], {a, -25 + 0.1, 25}]

and slightly modyfing the ranges of the last ParametricPlot : {t, -300, 300},

and PlotRange -> {{-.2, .3}, {-.25, .25}} :

ParametricPlot[

Join @@ { Table[{Re @ F[t + I k], Im @ F[t + I k]}, {k, -3, 3}],

Table[{Re @ F[k + I t], Im @ F[k + I t]},

{k, {-7, -5, -3, -2, 0, 2, 3, 5, 7}}]}, {t, -300, 300},

PlotRange -> {{-.2, .3}, {-.25, .25}}, Epilog -> {Red, PointSize[0.015],

Point[{Re @ #, Im @ #} & /@ F @ pts]},

Evaluated -> True, PlotStyle -> Thick]

GraphicsRow[

ParametricPlot[ ##, Evaluated -> True, PlotStyle -> Thick] & @@@ {

{ Join @@ {Table[{t, k}, {k, -3, 3}],

Table[{k, t}, {k, {-7, -5, -3, -2, 0, 2, 3, 5, 7}}]},

{t, -25, a}, PlotRange -> {{-30, 30}, {-30, 30}},

Epilog -> {Red, PointSize[0.015], Point[{#, 0} & /@ pts]} },

{ Join @@ {Table[{Re @ F[t + I k], Im @ F[t + I k]}, {k, -3, 3}],

Table[{Re @ F[k + I t], Im @ F[k + I t]},

{k, {-7, -5, -3, -2, 0, 2, 3, 5, 7}}]},

{t, -25, a}, PlotRange -> {{-.4, .6}, {-.51, .51}},

Epilog -> { Red, PointSize[0.015],

Point[{Re @ F[#], Im @ F[#]} & /@ pts]}}},

ImageSize -> 800 ], {a, -25 + 0.1, 25}]

and slightly modyfing the ranges of the last ParametricPlot : {t, -300, 300},

and PlotRange -> {{-.2, .3}, {-.25, .25}} :

ParametricPlot[

Join @@ { Table[{Re @ F[t + I k], Im @ F[t + I k]}, {k, -3, 3}],

Table[{Re @ F[k + I t], Im @ F[k + I t]},

{k, {-7, -5, -3, -2, 0, 2, 3, 5, 7}}]}, {t, -300, 300},

PlotRange -> {{-.2, .3}, {-.25, .25}}, Epilog -> {Red, PointSize[0.015],

Point[{Re @ #, Im @ #} & /@ F @ pts]},

Evaluated -> True, PlotStyle -> Thick]

(C)

convolution system with impulse response h,

transfer function H PSfrag replacements u y H sinusoidal

input u(t)

convolution system with impulse response h,

transfer function H PSfrag replacements u y H sinusoidal

input u(t)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

= cos(ωt)

=¡ejωt + e−jωt¢ /2 output is y(t)

= Z t 0 h(τ ) cos(ω(t − τ )) dτ let’s write this as y(t)

= Z ∞0 h(τ ) cos(ω(t − τ )) dτ − Z ∞t h(τ ) cos(ω(t − τ )) dτ

• first term is called sinusoidal steady-state response

• second term decays with t if system is stable;

if it decays it is called the transient Sinusoidal steady-state and frequency response

10–2 if system is stable, sinusoidal steady-state response can be expressed as

ysss(t)

= Z ∞0 h(τ ) cos(ω(t − τ )) dτ = (1/2) Z ∞0 h(τ ) ³ejω(t−τ) + e−jω(t−τ)´ dτ

= (1/2)ejωt Z ∞0 h(τ )e−jωτ dτ + (1/2)e−jωt Z ∞0 h(τ )ejωτ dτ

= (1/2)ejωtH(jω) + (1/2)e−jωtH(−jω)

= (<H(jω)) cos(ωt) − (=H(jω))sin(ωt)

= a cos(ωt + φ)

where a = |H(jω)|, φ = 6 H(jω).

Q.No:2

(A)

In a complex number, a+ib, a is the real part and b is the imaginary part, although, of course,

both a and b are real numbers.

The complex conjugate of z=a+ib is z*=a-ib.

You can express complex numbers in various forms, including algebraic, trigonometric and

exponential form. For instance:

a+ib (algebraic)

r(cosф +sinф) (trigonometric)

reiφ (exponential)

z=a+ib, Re(z)=a, Im(z)=b (Real and Imaginary parts)

=¡ejωt + e−jωt¢ /2 output is y(t)

= Z t 0 h(τ ) cos(ω(t − τ )) dτ let’s write this as y(t)

= Z ∞0 h(τ ) cos(ω(t − τ )) dτ − Z ∞t h(τ ) cos(ω(t − τ )) dτ

• first term is called sinusoidal steady-state response

• second term decays with t if system is stable;

if it decays it is called the transient Sinusoidal steady-state and frequency response

10–2 if system is stable, sinusoidal steady-state response can be expressed as

ysss(t)

= Z ∞0 h(τ ) cos(ω(t − τ )) dτ = (1/2) Z ∞0 h(τ ) ³ejω(t−τ) + e−jω(t−τ)´ dτ

= (1/2)ejωt Z ∞0 h(τ )e−jωτ dτ + (1/2)e−jωt Z ∞0 h(τ )ejωτ dτ

= (1/2)ejωtH(jω) + (1/2)e−jωtH(−jω)

= (<H(jω)) cos(ωt) − (=H(jω))sin(ωt)

= a cos(ωt + φ)

where a = |H(jω)|, φ = 6 H(jω).

Q.No:2

(A)

In a complex number, a+ib, a is the real part and b is the imaginary part, although, of course,

both a and b are real numbers.

The complex conjugate of z=a+ib is z*=a-ib.

You can express complex numbers in various forms, including algebraic, trigonometric and

exponential form. For instance:

a+ib (algebraic)

r(cosф +sinф) (trigonometric)

reiφ (exponential)

z=a+ib, Re(z)=a, Im(z)=b (Real and Imaginary parts)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Complex numbers are added as follows.

Let a+ib, and c+id be a complex number, where a, b, c, and d are real numbers.

i�, or j� = – 1

(a+i�b)+(c+i�d)=(a+b) + i(b+d)

For instance:

(2+3�i)+(4+5�i)= (2+4)+(3+5)i = 6+8�i

Complex numbers often come in pairs, such as a+b�i, a–b�i and are called conjugate. If we

use z to refer to a complex number, then the conjugate is written: z*, or complex conjugate

symbol so, if:

z=a+i�b, then z*=a–i�b

Conjugate complex numbers have these properties in arithmetic:

z+z* =2a (2�Re(z) )

z-z*=2b�i (2�Im(z) )

zz*=a2 + b2 (Re(z)2 + Im(z)2 )

That is, the result has a real part only, the imaginary part vanishes.

(B)

e have `r = 5` from the question.

We must express ` θ = 135^@` in radians.

Recall:

`1^text(o)=pi/180`

So

`135^text(o)=(135pi)/180`

`=(3pi)/4`

`~~2.36` radians

So we can write

`5(cos\ 135^text(o)+j\ sin135^text(o))`

`=5e^((3pij)/4)`

Let a+ib, and c+id be a complex number, where a, b, c, and d are real numbers.

i�, or j� = – 1

(a+i�b)+(c+i�d)=(a+b) + i(b+d)

For instance:

(2+3�i)+(4+5�i)= (2+4)+(3+5)i = 6+8�i

Complex numbers often come in pairs, such as a+b�i, a–b�i and are called conjugate. If we

use z to refer to a complex number, then the conjugate is written: z*, or complex conjugate

symbol so, if:

z=a+i�b, then z*=a–i�b

Conjugate complex numbers have these properties in arithmetic:

z+z* =2a (2�Re(z) )

z-z*=2b�i (2�Im(z) )

zz*=a2 + b2 (Re(z)2 + Im(z)2 )

That is, the result has a real part only, the imaginary part vanishes.

(B)

e have `r = 5` from the question.

We must express ` θ = 135^@` in radians.

Recall:

`1^text(o)=pi/180`

So

`135^text(o)=(135pi)/180`

`=(3pi)/4`

`~~2.36` radians

So we can write

`5(cos\ 135^text(o)+j\ sin135^text(o))`

`=5e^((3pij)/4)`

` ~~ 5e^(2.36j)`

Q.No:3

(A)

Step 1:

First, the data have to be entered as matrices by listing them between brackets, leaving a space

between each entry.

X=[0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.85];

ra=[0.0053 0.0052 0.005 0.0045 0.004 0.0033 0.0025 0.0018 0.00125 0.001];

4 Appendices

Step 2:

Next, the function polyfit is used to fit the data to a third-order polynomial. To learn more about the

function polyfit, type help polyfit at the command prompt.

p=polyfit(X,ra,3) (matrix of coefficients=polyfit(ind.

variable, dep. variable, order of polynomial)

p =0.0092 -0.0153 0.0013 0.0053

The coefficients are arranged in decreasing order of the independent variable of the polynomial;

therefore,

ra = 0.0092X3 – 0.0153X2 + 0.0013X = 0.0053

Please note that the typical mathematical convention for ordering coefficients is

y = a0 + a1x + a2x2 + ... + anxn whereas,

Matlab returns the solution ordered from an to a0.

Step 3:

Next, a variable f is assigned to evaluate the polynomial at the data points (i.e., f holds the ra values

calculated from the equation of the polynomial fit.)

Because X is a 1 × 10 matrix,

f will also be 1 × 10 in size.

f=polyval(p,X); f=polyval(matrix of coefficients, ind.

Q.No:3

(A)

Step 1:

First, the data have to be entered as matrices by listing them between brackets, leaving a space

between each entry.

X=[0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.85];

ra=[0.0053 0.0052 0.005 0.0045 0.004 0.0033 0.0025 0.0018 0.00125 0.001];

4 Appendices

Step 2:

Next, the function polyfit is used to fit the data to a third-order polynomial. To learn more about the

function polyfit, type help polyfit at the command prompt.

p=polyfit(X,ra,3) (matrix of coefficients=polyfit(ind.

variable, dep. variable, order of polynomial)

p =0.0092 -0.0153 0.0013 0.0053

The coefficients are arranged in decreasing order of the independent variable of the polynomial;

therefore,

ra = 0.0092X3 – 0.0153X2 + 0.0013X = 0.0053

Please note that the typical mathematical convention for ordering coefficients is

y = a0 + a1x + a2x2 + ... + anxn whereas,

Matlab returns the solution ordered from an to a0.

Step 3:

Next, a variable f is assigned to evaluate the polynomial at the data points (i.e., f holds the ra values

calculated from the equation of the polynomial fit.)

Because X is a 1 × 10 matrix,

f will also be 1 × 10 in size.

f=polyval(p,X); f=polyval(matrix of coefficients, ind.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

variable) To learn more about the function polyval, type help polyval at the command prompt.

Step 4:

Finally, a plot is prepared to show how well the polynomial fits the data.

plot(X,ra,'o',X,f,'-') plot(ind. var., dep. var., ‘symbol’, ind. var., f, ‘symbol’)

where ‘symbol’ denotes how the data are to be plotted.

In this case, the data set is plotted as circles and the fitted polynomial is plotted as a line. The following

commands label and define the scale of the axes.

xlabel('X'); ylabel('ra "o", f "-"');

axis([0 0.85 0 0.006]);

xlabel(‘text’); ylabel(‘text’);

axis([xmin xmax ymin ymax]) Please refer to help plot for more information on preparing plots. The

variance, or the sum of the squares of the difference between the actual data and the values calculated

from the polynomial, can also be calculated.

variance=sum((ra-f).^2) variance =1.6014e-008

The command (ra-f) creates a matrix the same size as ra and f and contains the element-by-element

subtraction of f from ra. Every element of this new matrix is then squared to create a third matrix. Then,

by summing all the elements of this third matrix, the result is a 1x1 matrix, a scalar, equal to the

variance.

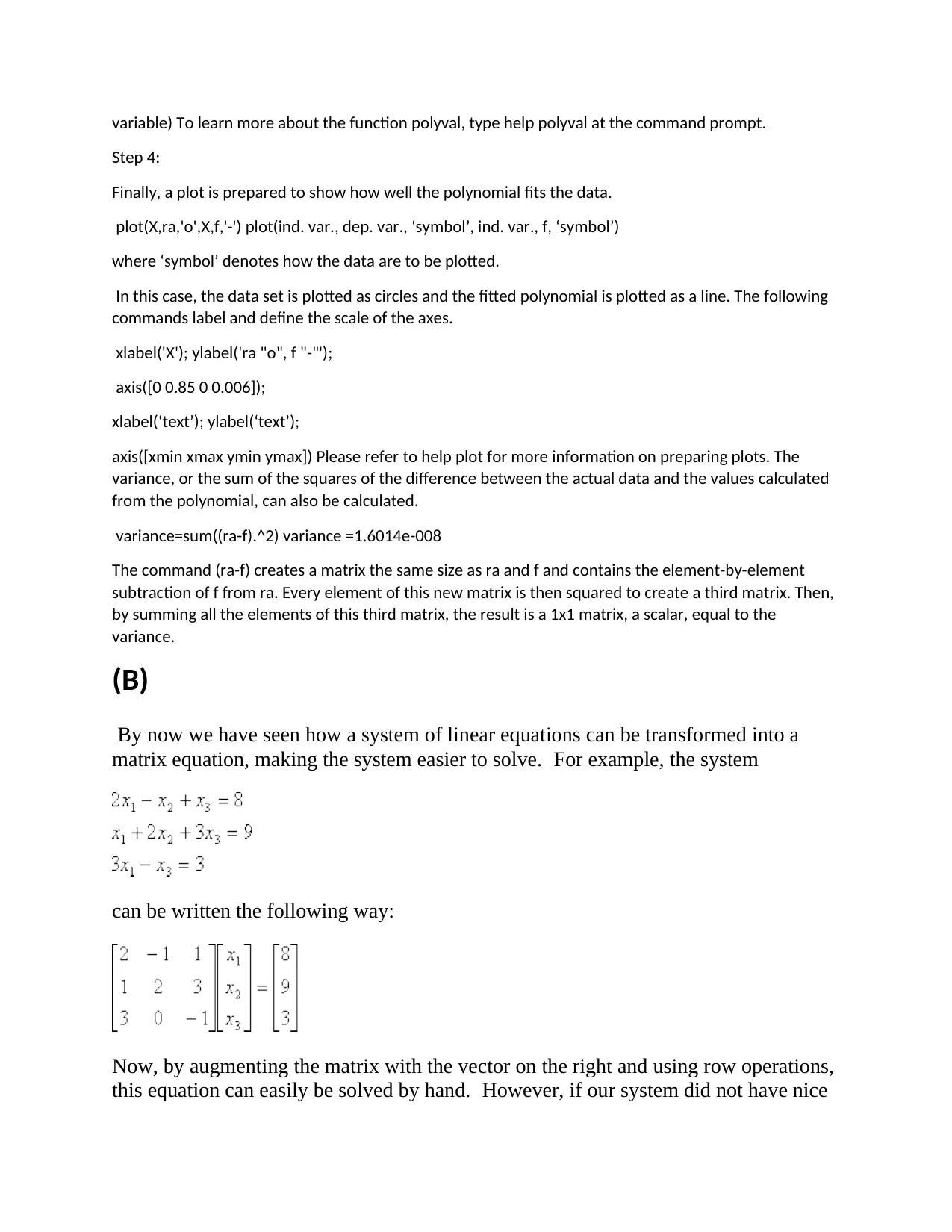

(B)

By now we have seen how a system of linear equations can be transformed into a

matrix equation, making the system easier to solve. For example, the system

can be written the following way:

Now, by augmenting the matrix with the vector on the right and using row operations,

this equation can easily be solved by hand. However, if our system did not have nice

Step 4:

Finally, a plot is prepared to show how well the polynomial fits the data.

plot(X,ra,'o',X,f,'-') plot(ind. var., dep. var., ‘symbol’, ind. var., f, ‘symbol’)

where ‘symbol’ denotes how the data are to be plotted.

In this case, the data set is plotted as circles and the fitted polynomial is plotted as a line. The following

commands label and define the scale of the axes.

xlabel('X'); ylabel('ra "o", f "-"');

axis([0 0.85 0 0.006]);

xlabel(‘text’); ylabel(‘text’);

axis([xmin xmax ymin ymax]) Please refer to help plot for more information on preparing plots. The

variance, or the sum of the squares of the difference between the actual data and the values calculated

from the polynomial, can also be calculated.

variance=sum((ra-f).^2) variance =1.6014e-008

The command (ra-f) creates a matrix the same size as ra and f and contains the element-by-element

subtraction of f from ra. Every element of this new matrix is then squared to create a third matrix. Then,

by summing all the elements of this third matrix, the result is a 1x1 matrix, a scalar, equal to the

variance.

(B)

By now we have seen how a system of linear equations can be transformed into a

matrix equation, making the system easier to solve. For example, the system

can be written the following way:

Now, by augmenting the matrix with the vector on the right and using row operations,

this equation can easily be solved by hand. However, if our system did not have nice

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

integer entries, solving the system by hand using row reduction could become very

difficult. MATLAB provides us with an easier way to get an answer.

A system of this type has the form Ax = b, so we can enter these numbers into

MATLAB using the following commands:

>> A = [2 -1 1; 1 2 3; 3 0 -1]

>> b = [8; 9; 3]

(Notice that for the column vector b, we include semicolons after each entry to ensure

that the entries are on different rows; the command

>> b = [8 9 3]

would produce a row vector, which is not the same thing.)

The command

>> x = A\b

will find the solution (if it exists) to our equation Ax = b. In this case, MATLAB tells

us

x =

2.0000

-1.0000

3.0000

Remark 2.1 Please take care in entering "A\b" command. It has a backslash "\", NOT

a forward slash "/".

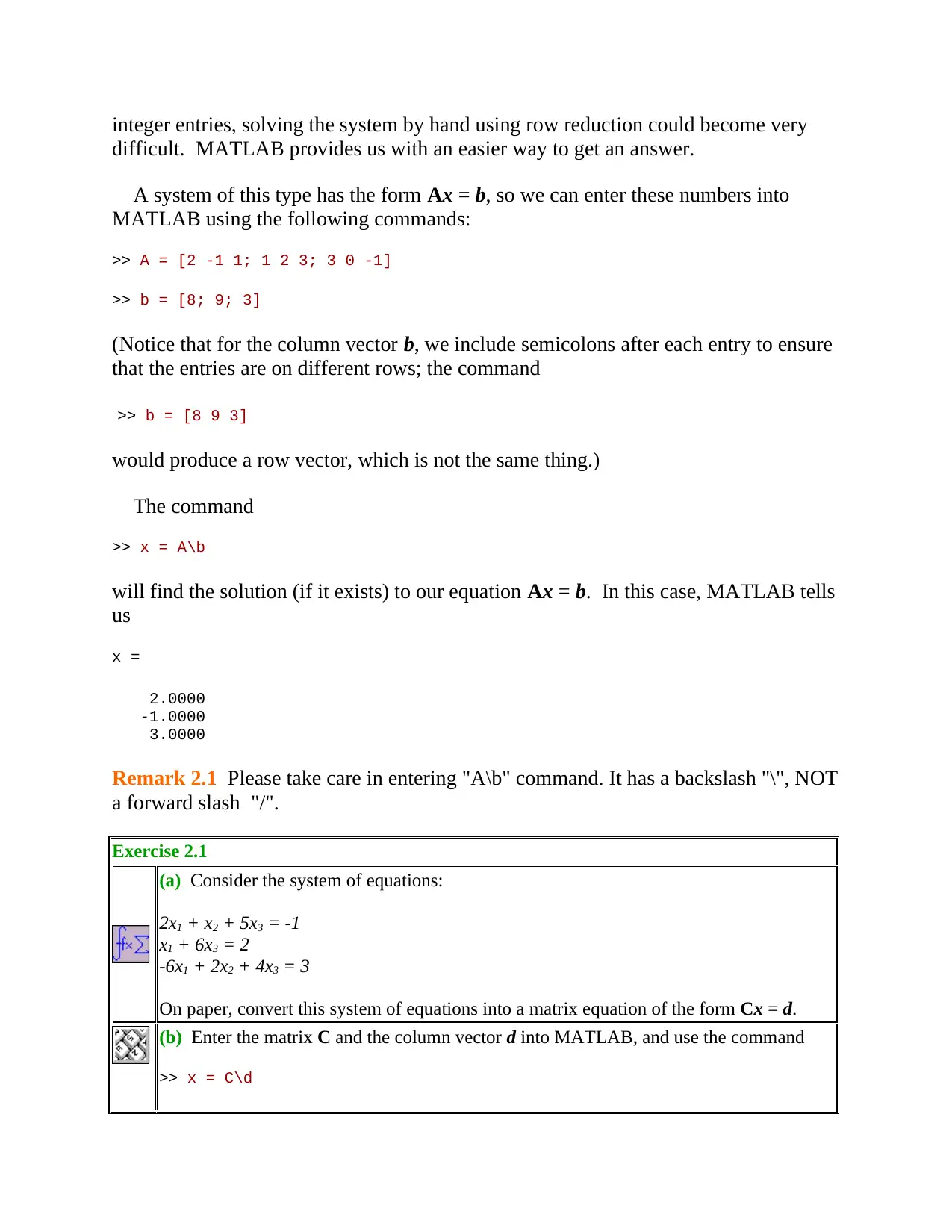

Exercise 2.1

(a) Consider the system of equations:

2x1 + x2 + 5x3 = -1

x1 + 6x3 = 2

-6x1 + 2x2 + 4x3 = 3

On paper, convert this system of equations into a matrix equation of the form Cx = d.

(b) Enter the matrix C and the column vector d into MATLAB, and use the command

>> x = C\d

difficult. MATLAB provides us with an easier way to get an answer.

A system of this type has the form Ax = b, so we can enter these numbers into

MATLAB using the following commands:

>> A = [2 -1 1; 1 2 3; 3 0 -1]

>> b = [8; 9; 3]

(Notice that for the column vector b, we include semicolons after each entry to ensure

that the entries are on different rows; the command

>> b = [8 9 3]

would produce a row vector, which is not the same thing.)

The command

>> x = A\b

will find the solution (if it exists) to our equation Ax = b. In this case, MATLAB tells

us

x =

2.0000

-1.0000

3.0000

Remark 2.1 Please take care in entering "A\b" command. It has a backslash "\", NOT

a forward slash "/".

Exercise 2.1

(a) Consider the system of equations:

2x1 + x2 + 5x3 = -1

x1 + 6x3 = 2

-6x1 + 2x2 + 4x3 = 3

On paper, convert this system of equations into a matrix equation of the form Cx = d.

(b) Enter the matrix C and the column vector d into MATLAB, and use the command

>> x = C\d

to check your solution.

(c) We would expect to get the column vector d in MATLAB if we ran the

command C*x, right? In other words, C*x - d should be zero. Enter this equation into

MATLAB:

>> C*x-d

What do you get?

Remark 2.2 The discrepancy in part (c) of the above exercise is simply due to

rounding error. You'll notice that the error is a vector multiplied by a very small

number, one on the order of 10-15. But why is there any error at all? After all, solving

by row reduction gave very nice numbers, right? The reason lies in the way

MATLAB stores numbers. In this calculation MATLAB represents numbers in

"floating point form", which means it represents them in scientifc notation to 10^(-14)

accuracy. Thus when you see 10^(-14) printed in calculations, it is equivalent to zero.

There is a drawback, however, to solving systems of equations using the command

"x = C\d". Let us explore that further.

Exercise 2.2 Consider the following system of equations:

-10x1 + 4x2 = 0

15x1 - 6x2 = 0

As you did in the previous exercise, enter the corresponding matrix C and the

column vector d into MATLAB. Then type in

>> x = C\d

Note the strange output. Include it in your write up. Now go ahead and solve

this system by hand. How many free variables do you need to write down the

solution? Based on your answer, can you explain why you got the error

message when trying to use "x = C\d" command?

To deal with the case of inconsistent systems or systems with infinitely many

solutions, it may sometimes be better to use MATLAB to simply row-reduce your

matrix and then read off the solutions. We happen to be very lucky since MATLAB

has a command that performs Gaussian elimination for you.

Consider the following homogeneous system of equations:

(c) We would expect to get the column vector d in MATLAB if we ran the

command C*x, right? In other words, C*x - d should be zero. Enter this equation into

MATLAB:

>> C*x-d

What do you get?

Remark 2.2 The discrepancy in part (c) of the above exercise is simply due to

rounding error. You'll notice that the error is a vector multiplied by a very small

number, one on the order of 10-15. But why is there any error at all? After all, solving

by row reduction gave very nice numbers, right? The reason lies in the way

MATLAB stores numbers. In this calculation MATLAB represents numbers in

"floating point form", which means it represents them in scientifc notation to 10^(-14)

accuracy. Thus when you see 10^(-14) printed in calculations, it is equivalent to zero.

There is a drawback, however, to solving systems of equations using the command

"x = C\d". Let us explore that further.

Exercise 2.2 Consider the following system of equations:

-10x1 + 4x2 = 0

15x1 - 6x2 = 0

As you did in the previous exercise, enter the corresponding matrix C and the

column vector d into MATLAB. Then type in

>> x = C\d

Note the strange output. Include it in your write up. Now go ahead and solve

this system by hand. How many free variables do you need to write down the

solution? Based on your answer, can you explain why you got the error

message when trying to use "x = C\d" command?

To deal with the case of inconsistent systems or systems with infinitely many

solutions, it may sometimes be better to use MATLAB to simply row-reduce your

matrix and then read off the solutions. We happen to be very lucky since MATLAB

has a command that performs Gaussian elimination for you.

Consider the following homogeneous system of equations:

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 20

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.