Expatriate Leadership: Cultural Influence on Managerial Actions

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/26

|19

|8905

|53

Report

AI Summary

This report, authored by Muenjohn and Armstrong, investigates the impact of cultural values on the leadership behaviors of expatriate managers, specifically focusing on Australian managers working in Thailand. The study examines the relationship between the cultural values of Thai subordinates, assessed using Hofstede's cultural framework, and the leadership styles of expatriate managers, measured through the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) based on Bass and Avolio's transformational leadership model. The research aims to determine whether expatriate managers should adapt their leadership styles to the cultural backgrounds of their subordinates. The findings indicate a limited role for Thai subordinates' culture in predicting the leadership behaviors of expatriate managers, supporting a near universalistic perspective for the transformational-transactional paradigm. The study contributes to the understanding of cross-cultural leadership and provides insights for managing expatriates in Thailand. The report includes a literature review covering Hofstede's cultural framework, transformational leadership, and the debate between culture-specific and culture-universal leadership approaches. The study uses quantitative methods to analyze the relationships between cultural values and leadership behaviors, differentiating itself from previous qualitative studies. The conclusion emphasizes that transformational leadership is effective across cultures, though specific behaviors might vary.

Muenjohn and Armstrong

Volume 2, Number 2, December 2007

265

Transformational Leadership:

The Influence of Culture on the Leadership Behaviours

of Expatriate Managers

Nuttawuth Muenjohn

School of Management, RMIT University

239 Bourke St. Level 16 (Office 108.16.42)

Melbourne, Victoria 3000 Australia

nuttawuth.muenjohn@rmit.edu.au

Anona Armstrong

Centre for International Corporate Governance Research (CICGR)

Victoria University, Australia

ABSTRACT

One of the basic reasons that the authors investigated cross-cultural leadership

was to determine the extent to which leadership behaviours can be influenced by

cultural values. Some researchers suggest that certain leadership behaviours are

likely to be particular to a given culture, whereas others argue that there should

be certain structures that leaders must perform to be effective, regardless of

cultures. This study was conducted to determine the possible relationships

between the work-related values of subordinates and the leadership behaviours

exhibited by expatriate managers. Ninety-one Thai subordinates, direct-report of

expatriates, responded on the instruments called the Multifactor Leadership

Questionnaire (MLQ) and the Value Survey Module (VSM). Major results

indicate that the culture of Thai subordinates has a very limited role in predicting

the leadership behaviours of expatriate managers. Furthermore, the study seems

to provide evidence to support a near universalistic position for the

transformational-transactional paradigm.

Keywords: Leadership, cultural values, transformational leadership, expatriate

management

_____________

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to thank the Centre for International

Corporate Governance Research (CICGR), Faculty of Business & Law, Victoria

University, Australia, and the Faculty of Business, Asian University, Thailand, for their

support of this work.

Volume 2, Number 2, December 2007

265

Transformational Leadership:

The Influence of Culture on the Leadership Behaviours

of Expatriate Managers

Nuttawuth Muenjohn

School of Management, RMIT University

239 Bourke St. Level 16 (Office 108.16.42)

Melbourne, Victoria 3000 Australia

nuttawuth.muenjohn@rmit.edu.au

Anona Armstrong

Centre for International Corporate Governance Research (CICGR)

Victoria University, Australia

ABSTRACT

One of the basic reasons that the authors investigated cross-cultural leadership

was to determine the extent to which leadership behaviours can be influenced by

cultural values. Some researchers suggest that certain leadership behaviours are

likely to be particular to a given culture, whereas others argue that there should

be certain structures that leaders must perform to be effective, regardless of

cultures. This study was conducted to determine the possible relationships

between the work-related values of subordinates and the leadership behaviours

exhibited by expatriate managers. Ninety-one Thai subordinates, direct-report of

expatriates, responded on the instruments called the Multifactor Leadership

Questionnaire (MLQ) and the Value Survey Module (VSM). Major results

indicate that the culture of Thai subordinates has a very limited role in predicting

the leadership behaviours of expatriate managers. Furthermore, the study seems

to provide evidence to support a near universalistic position for the

transformational-transactional paradigm.

Keywords: Leadership, cultural values, transformational leadership, expatriate

management

_____________

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to thank the Centre for International

Corporate Governance Research (CICGR), Faculty of Business & Law, Victoria

University, Australia, and the Faculty of Business, Asian University, Thailand, for their

support of this work.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Transformational Leadership:

The Influence of Culture on Leadership Behaviours

International Journal of Business and Information

266

1. INTRODUCTION

Multinational corporations (MNCs) seeking a competitive advantage in the

management of their companies are increasingly relying on the appointment of

expatriate managers to carry out headquarters‟ policies in the host markets.

However, many expatriate appointments are unsuccessful. One of the reasons

may be cultural differences. Because of cultural differences, the question is

whether expatriates should adjust their style of leadership to conform to the

cultural background of subordinates. Given this case, some researchers believe

that leadership behaviours should be particular to a certain cultural environment

(Hofstede,1995), whereas others argue that the underlying constructs of effective

leadership tend to be similar across cultures [Levitt, 1995].

That Australian companies consider Thailand one of their important

investment bases is indicated by the continued, steady growth in trade between

the two countries. There are still few studies, however, of Australian expatriates

working in Thailand. To date, the most relevant studies are those by Thompson

[1981] and Edwards, Edwards, and Muthaly [1995]. Although both studies

selected Australian expatriates as the target population, the studies were limited

to providing guidelines for effective leadership behaviour for Australian

expatriates.

Australia and Thailand were identified as having different cultural values

when described by Hofstede‟s [1984] four cultural dimensions. Although

Australia is located in the Asia-Pacific region, it has a British historical

background and is heavily influenced by Western cultures [Harris and Moran,

1996]. Thailand, on the other hand, shares a common background with Eastern

cultures. These differences suggest that the two cultures would tend to diverge

from a common model of leadership. Understanding the influence of culture on

leadership behaviours would be a valuable contribution to the theory of cross-

cultural leadership and to the management practices of expatriate managers in

Thailand.

The purpose of this study is to determine the linkages between the cultural

values of host-nation subordinates and the leadership behaviours exhibited by

expatriate managers. More specifically, it seeks to answer a research question

about the extent to which the variance in three leadership behaviors exhibited by

Australian managers can be explained by four cultural values of Thai

subordinates. Two prominent theories were used in the current study. The

Hofstede [1984] four cultural model was adopted to determine the cultural values

of Thai subordinates, while transformational leadership [Bass and Avolio, 1997]

was used to capture the leadership behaviours of Australian expatriate managers.

The Influence of Culture on Leadership Behaviours

International Journal of Business and Information

266

1. INTRODUCTION

Multinational corporations (MNCs) seeking a competitive advantage in the

management of their companies are increasingly relying on the appointment of

expatriate managers to carry out headquarters‟ policies in the host markets.

However, many expatriate appointments are unsuccessful. One of the reasons

may be cultural differences. Because of cultural differences, the question is

whether expatriates should adjust their style of leadership to conform to the

cultural background of subordinates. Given this case, some researchers believe

that leadership behaviours should be particular to a certain cultural environment

(Hofstede,1995), whereas others argue that the underlying constructs of effective

leadership tend to be similar across cultures [Levitt, 1995].

That Australian companies consider Thailand one of their important

investment bases is indicated by the continued, steady growth in trade between

the two countries. There are still few studies, however, of Australian expatriates

working in Thailand. To date, the most relevant studies are those by Thompson

[1981] and Edwards, Edwards, and Muthaly [1995]. Although both studies

selected Australian expatriates as the target population, the studies were limited

to providing guidelines for effective leadership behaviour for Australian

expatriates.

Australia and Thailand were identified as having different cultural values

when described by Hofstede‟s [1984] four cultural dimensions. Although

Australia is located in the Asia-Pacific region, it has a British historical

background and is heavily influenced by Western cultures [Harris and Moran,

1996]. Thailand, on the other hand, shares a common background with Eastern

cultures. These differences suggest that the two cultures would tend to diverge

from a common model of leadership. Understanding the influence of culture on

leadership behaviours would be a valuable contribution to the theory of cross-

cultural leadership and to the management practices of expatriate managers in

Thailand.

The purpose of this study is to determine the linkages between the cultural

values of host-nation subordinates and the leadership behaviours exhibited by

expatriate managers. More specifically, it seeks to answer a research question

about the extent to which the variance in three leadership behaviors exhibited by

Australian managers can be explained by four cultural values of Thai

subordinates. Two prominent theories were used in the current study. The

Hofstede [1984] four cultural model was adopted to determine the cultural values

of Thai subordinates, while transformational leadership [Bass and Avolio, 1997]

was used to capture the leadership behaviours of Australian expatriate managers.

Muenjohn and Armstrong

Volume 2, Number 2, December 2007

267

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

This literature review is organized into four parts: Hofstede‟s cultural

framework (2.1), Bass and Avoilio‟s transformational leadership (2.2), culture-

specific versus culture-universal (2.3), and transformational leadership in the

cross-cultural setting (2.4).

2.1. Defining Culture: Hofstede’s Cultural Framework

Culture can be defined by several terms. In fact, Kroeber and Kluckhohn

[1952] gathered more than 160 distinct definitions of the word “culture” and

catalogued it into seven separate groups. Perhaps the best-known work is that of

Hofstede [1984], whose survey of 88,000 respondents in 66 countries generated a

33-item questionnaire that measured four cultural dimensions.

Power distance described the extent to which inequalities were accepted

among the people of a society. In countries with high power distance, people

accepted and expected differences in power among them, whereas in countries

with low power distance, the majority expected that the differences in power

should be minimized.

Uncertainty avoidance indicated the extent to which people in a society feel

threatened by unpredictable or unknown situations and thus “[try] to avoid these

situations by providing greater career stability, establishing more formal rules…

and believing in absolute truths and the attainment of expertise” [Hofstede, 1995,

p. 195].

Masculinity, with its opposite pole, Femininity, reflected the distribution of

roles between sexes that different societies exhibited in different ways.

Hofstede‟s [1984] analysis revealed that the dominant values of people in a

masculine society were assertive and competitive, whereas members of a

feminine culture valued more nurturing, caring, and modesty.

Individualism, with its opposite, Collectivism, described the degree to which

individuals in a society were integrated into groups. In an individualistic society,

the ties between individuals were loose. People were supposed to take care of

themselves and their immediate families. In a collectivistic country, people were

described as living within a tight social framework.

Hofstede‟s cultural framework, according to Mead [1998, p. 43], provided

“the best there is” of a conceptual benchmark for understanding culture in many

societies or countries. The model not only showed the significant relationships

between its dimensions and several areas of general management [see, for

example, Katz and Seifer, 1996, for motivation systems; and Boyacigiller,

Kleinberg, Phillips, and Sackmann, 1996, for decision making], but also its

relationships with leadership behaviors [e.g., Blunt and Jones, 1997; Elenkov,

1997].

Volume 2, Number 2, December 2007

267

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

This literature review is organized into four parts: Hofstede‟s cultural

framework (2.1), Bass and Avoilio‟s transformational leadership (2.2), culture-

specific versus culture-universal (2.3), and transformational leadership in the

cross-cultural setting (2.4).

2.1. Defining Culture: Hofstede’s Cultural Framework

Culture can be defined by several terms. In fact, Kroeber and Kluckhohn

[1952] gathered more than 160 distinct definitions of the word “culture” and

catalogued it into seven separate groups. Perhaps the best-known work is that of

Hofstede [1984], whose survey of 88,000 respondents in 66 countries generated a

33-item questionnaire that measured four cultural dimensions.

Power distance described the extent to which inequalities were accepted

among the people of a society. In countries with high power distance, people

accepted and expected differences in power among them, whereas in countries

with low power distance, the majority expected that the differences in power

should be minimized.

Uncertainty avoidance indicated the extent to which people in a society feel

threatened by unpredictable or unknown situations and thus “[try] to avoid these

situations by providing greater career stability, establishing more formal rules…

and believing in absolute truths and the attainment of expertise” [Hofstede, 1995,

p. 195].

Masculinity, with its opposite pole, Femininity, reflected the distribution of

roles between sexes that different societies exhibited in different ways.

Hofstede‟s [1984] analysis revealed that the dominant values of people in a

masculine society were assertive and competitive, whereas members of a

feminine culture valued more nurturing, caring, and modesty.

Individualism, with its opposite, Collectivism, described the degree to which

individuals in a society were integrated into groups. In an individualistic society,

the ties between individuals were loose. People were supposed to take care of

themselves and their immediate families. In a collectivistic country, people were

described as living within a tight social framework.

Hofstede‟s cultural framework, according to Mead [1998, p. 43], provided

“the best there is” of a conceptual benchmark for understanding culture in many

societies or countries. The model not only showed the significant relationships

between its dimensions and several areas of general management [see, for

example, Katz and Seifer, 1996, for motivation systems; and Boyacigiller,

Kleinberg, Phillips, and Sackmann, 1996, for decision making], but also its

relationships with leadership behaviors [e.g., Blunt and Jones, 1997; Elenkov,

1997].

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Transformational Leadership:

The Influence of Culture on Leadership Behaviours

International Journal of Business and Information

268

2.2. Leadership: Bass and Avolio’s Transformational Leadership

Although the constructs of the transformational leadership model are not new

and could be found in the works of earlier management theorists [Humphreys and

Einstein, 2003], transformational leadership was recognized as a new and current

approach to leadership [Northouse, 1997]. Based on the work of Burns [1978],

Bass [1985] identified three major leadership behaviours: laissez-faire,

transactional, and transformational leadership.

Laissez-faire represented an absence of leadership. A laissez-faire leader

showed no concern and responsibility for the results of his or her projects.

Followers working under this leader were usually left to their own

responsibilities and might need to seek assistance and supervision from

alternative sources [Dubinsky, Yammarino, Jolson, and Spangler, 1995].

A transactional leader identified and clarified his or her expectation to

followers and promised rewards in exchange for the desired goals. To achieve the

goals, the transactional leader needed to clearly determine and define the role and

task required of the followers. A transactional leader also exhibited his or her

behaviour when involved in corrective criticism, negative feedback, and negative

reinforcement.

Transformational leadership was a process in which the leaders took

actions to try to increase their followers‟ awareness of what was right and

important. This process was associated with motivating followers to perform

“beyond expectation” and encouraging followers to look beyond their own self-

interest for the good of the group or organisation. By working harder for a

transformational leader, his or her followers could develop their skills by using

their own decisions and taking greater responsibility [Den Hartog, Van Muijen,

and Koopman, 1997].

Several authors have confirmed that transformational leadership behaviour

was, on average, highly positively correlated with subordinates‟ satisfaction,

extra effort, and effectiveness, whereas transactional leadership was generally

viewed as being positively linked to performance outcomes. For laissez-faire, it

had been found consistently to be negatively correlated with all of the measures

of performance outcomes among followers [see, for example, Kirkbride, 2006;

Ingram, 1997; Medley and Larochelle, 1995; Bass and Avolio, 1997].

2.3. Culture and Leadership: Culture-Specific versus Culture-Universal

One of the main debates among cross-cultural management scholars was

that of how well the application of management practices could be transferred

across cultures. On the one hand, it was believed that the significant changes of

technology, communication, transportation, and free-market capitalism had

resulted in cultures‟ becoming more alike [Levitt, 1995]. On the other hand, it

was argued that culture was steeped in a deep value system that was unlikely to

change; thus, management practices needed to be tailor-made to fit diverse

cultural backgrounds [Hofstede, 1995].

The Influence of Culture on Leadership Behaviours

International Journal of Business and Information

268

2.2. Leadership: Bass and Avolio’s Transformational Leadership

Although the constructs of the transformational leadership model are not new

and could be found in the works of earlier management theorists [Humphreys and

Einstein, 2003], transformational leadership was recognized as a new and current

approach to leadership [Northouse, 1997]. Based on the work of Burns [1978],

Bass [1985] identified three major leadership behaviours: laissez-faire,

transactional, and transformational leadership.

Laissez-faire represented an absence of leadership. A laissez-faire leader

showed no concern and responsibility for the results of his or her projects.

Followers working under this leader were usually left to their own

responsibilities and might need to seek assistance and supervision from

alternative sources [Dubinsky, Yammarino, Jolson, and Spangler, 1995].

A transactional leader identified and clarified his or her expectation to

followers and promised rewards in exchange for the desired goals. To achieve the

goals, the transactional leader needed to clearly determine and define the role and

task required of the followers. A transactional leader also exhibited his or her

behaviour when involved in corrective criticism, negative feedback, and negative

reinforcement.

Transformational leadership was a process in which the leaders took

actions to try to increase their followers‟ awareness of what was right and

important. This process was associated with motivating followers to perform

“beyond expectation” and encouraging followers to look beyond their own self-

interest for the good of the group or organisation. By working harder for a

transformational leader, his or her followers could develop their skills by using

their own decisions and taking greater responsibility [Den Hartog, Van Muijen,

and Koopman, 1997].

Several authors have confirmed that transformational leadership behaviour

was, on average, highly positively correlated with subordinates‟ satisfaction,

extra effort, and effectiveness, whereas transactional leadership was generally

viewed as being positively linked to performance outcomes. For laissez-faire, it

had been found consistently to be negatively correlated with all of the measures

of performance outcomes among followers [see, for example, Kirkbride, 2006;

Ingram, 1997; Medley and Larochelle, 1995; Bass and Avolio, 1997].

2.3. Culture and Leadership: Culture-Specific versus Culture-Universal

One of the main debates among cross-cultural management scholars was

that of how well the application of management practices could be transferred

across cultures. On the one hand, it was believed that the significant changes of

technology, communication, transportation, and free-market capitalism had

resulted in cultures‟ becoming more alike [Levitt, 1995]. On the other hand, it

was argued that culture was steeped in a deep value system that was unlikely to

change; thus, management practices needed to be tailor-made to fit diverse

cultural backgrounds [Hofstede, 1995].

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Muenjohn and Armstrong

Volume 2, Number 2, December 2007

269

These conflicting viewpoints were also applied to the study of leadership

when culture was used to explain leadership behaviour. Two terms used by

Triandis [1994] to distinguish the different types of cross-cultural studies were

“emic” and “etic.” Emics referred to ideas, behaviours, and concepts that were

culturally unique or specific, whereas etics referred to ideas, behaviours, and

concepts that were culturally universal.

In terms of leadership, the emic approach assumed that different leadership

prototypes or characteristics would be expected to occur in societies that had

different cultural profiles. In contrast, the etic approach suggested that, although

differences between cultures might exist, there were certain underlying structures

or behaviours that leaders had to perform to be effective leaders, regardless of

cultures.

2.4. Transformational Leadership in a Cross-Cultural Setting

A limited number of studies have examined the relationships between

culture and transformational leadership. Many of those, however, were

conceptual investigations. For example, Jung, Bass, and Sosik [1995], based on

their review, proposed that several characteristics of collectivistic cultures should

enhance an easier emergence of transformational leadership than would be the

case in individualistic cultures. Dorfman [1996] also believed that the basic

behaviours recognised in transformational leadership, such as inspiration,

motivation, individual consideration, and intellectual challenge, were seen as a

“core function” of outstanding leaders that should be similar around the world.

Based on their empirical data in the U.S. and Taiwan, Spreitzer, Perttula,

and Xin [2005] found that cultural values play a significant role in the

relationships between transformational leadership and leadership effectiveness.

Madzar [2005] also found that transformation leadership seems to be a

meaningful determinant of subordinates‟ information-seeking across five

countries.

Bass [1997] believed that transformational leadership should travel well

across cultures. The universality of transformational leadership, according to

Bass [1977] was based on the fact that leaders who practiced transformational

leadership were more effective than those who displayed transactional or non-

leadership behaviours, regardless of cultures, countries, and organisations. Bass

[1997] also acknowledged that „universal,‟ in his meaning, was a universally

applicable conceptualization. That is, although the concept of transformational

leadership appeared to be universally valid, the specific behaviours associated

with each leadership factor might vary to some extent, particularly from one

country to another.

Volume 2, Number 2, December 2007

269

These conflicting viewpoints were also applied to the study of leadership

when culture was used to explain leadership behaviour. Two terms used by

Triandis [1994] to distinguish the different types of cross-cultural studies were

“emic” and “etic.” Emics referred to ideas, behaviours, and concepts that were

culturally unique or specific, whereas etics referred to ideas, behaviours, and

concepts that were culturally universal.

In terms of leadership, the emic approach assumed that different leadership

prototypes or characteristics would be expected to occur in societies that had

different cultural profiles. In contrast, the etic approach suggested that, although

differences between cultures might exist, there were certain underlying structures

or behaviours that leaders had to perform to be effective leaders, regardless of

cultures.

2.4. Transformational Leadership in a Cross-Cultural Setting

A limited number of studies have examined the relationships between

culture and transformational leadership. Many of those, however, were

conceptual investigations. For example, Jung, Bass, and Sosik [1995], based on

their review, proposed that several characteristics of collectivistic cultures should

enhance an easier emergence of transformational leadership than would be the

case in individualistic cultures. Dorfman [1996] also believed that the basic

behaviours recognised in transformational leadership, such as inspiration,

motivation, individual consideration, and intellectual challenge, were seen as a

“core function” of outstanding leaders that should be similar around the world.

Based on their empirical data in the U.S. and Taiwan, Spreitzer, Perttula,

and Xin [2005] found that cultural values play a significant role in the

relationships between transformational leadership and leadership effectiveness.

Madzar [2005] also found that transformation leadership seems to be a

meaningful determinant of subordinates‟ information-seeking across five

countries.

Bass [1997] believed that transformational leadership should travel well

across cultures. The universality of transformational leadership, according to

Bass [1977] was based on the fact that leaders who practiced transformational

leadership were more effective than those who displayed transactional or non-

leadership behaviours, regardless of cultures, countries, and organisations. Bass

[1997] also acknowledged that „universal,‟ in his meaning, was a universally

applicable conceptualization. That is, although the concept of transformational

leadership appeared to be universally valid, the specific behaviours associated

with each leadership factor might vary to some extent, particularly from one

country to another.

Transformational Leadership:

The Influence of Culture on Leadership Behaviours

International Journal of Business and Information

270

3. PRESENT INVESTIGATION AND ITS HYPOTHESES

As previously mentioned, the studies of Thompson [1981] and Edwards et

al. [1995] only investigated the general experience of Australian expatriates in

Thailand, and both studies conducted their research by relying mainly on

qualitative approaches that might lead researchers to use their personal judgments

when it came to interpreting the results [Sekaran, 2000]. The present study,

therefore, will differ from the previous studies by: (a) investigating the leadership

behaviours of Australian expatriate managers; (b) linking those leadership

behaviours to the cultural background of Thai subordinates; (c) drawing on two

well-recognized theoretical models, transformational leadership [Bass and

Avolio, 1997] and four cultural dimensions [Hofstede, 1984]; and (d) using a

quantitative approach.

Reviews of cross-cultural leadership [e.g., Dorfman, 1996; Bass, 1990; Den

Hartog et al., 1999] had raised the basic question: Were there universally

endorsed prototypes of ideal leaders, regardless of culture? In fact, their studies

of cross-cultural leadership showed the conflict of viewpoints between “culture-

specific” and “culture-universal” approaches. Regarding the two approaches,

Chemers [1997] argued that, if an investigation concerned leadership at the

general or basic function, then the universal perspective was likely to be

confirmed. However, if leadership was examined at the level of specific

behaviour, then culture seemed to play a strong role.

Chemers‟ [1997] proposition seemed to be consistent with previous

literature investigating the influence of culture on leadership, which found that

culture was likely to have a very limited role in the transformational-transactional

paradigm at the principle level [see Drofman, 1996; Den Hartong et al., 1999;

Bass, 1997], whereas specific behaviours might vary across cultures [Jung et al.,

1995]. Furthermore, transformational leadership, according to Bass [1997] and

Den Hartog et al. [1999], tended to show that leadership behaviours were

“culture-free” when considering different types of universals. Accordingly, the

following three hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 1: that the four cultural dimensions of Thai subordinates will

not significantly explain the variance in the transformational leadership

behaviour exhibited by Australian managers.

Hypothesis 2: that the four cultural dimensions of Thai subordinates will

not significantly explain the variance in the transactional leadership behaviour

exhibited by Australian managers.

Hypothesis 3: that the four cultural dimensions of Thai subordinates will

not significantly explain the variance in the laissez-faire leadership behaviour

exhibited by Australian managers.

The Influence of Culture on Leadership Behaviours

International Journal of Business and Information

270

3. PRESENT INVESTIGATION AND ITS HYPOTHESES

As previously mentioned, the studies of Thompson [1981] and Edwards et

al. [1995] only investigated the general experience of Australian expatriates in

Thailand, and both studies conducted their research by relying mainly on

qualitative approaches that might lead researchers to use their personal judgments

when it came to interpreting the results [Sekaran, 2000]. The present study,

therefore, will differ from the previous studies by: (a) investigating the leadership

behaviours of Australian expatriate managers; (b) linking those leadership

behaviours to the cultural background of Thai subordinates; (c) drawing on two

well-recognized theoretical models, transformational leadership [Bass and

Avolio, 1997] and four cultural dimensions [Hofstede, 1984]; and (d) using a

quantitative approach.

Reviews of cross-cultural leadership [e.g., Dorfman, 1996; Bass, 1990; Den

Hartog et al., 1999] had raised the basic question: Were there universally

endorsed prototypes of ideal leaders, regardless of culture? In fact, their studies

of cross-cultural leadership showed the conflict of viewpoints between “culture-

specific” and “culture-universal” approaches. Regarding the two approaches,

Chemers [1997] argued that, if an investigation concerned leadership at the

general or basic function, then the universal perspective was likely to be

confirmed. However, if leadership was examined at the level of specific

behaviour, then culture seemed to play a strong role.

Chemers‟ [1997] proposition seemed to be consistent with previous

literature investigating the influence of culture on leadership, which found that

culture was likely to have a very limited role in the transformational-transactional

paradigm at the principle level [see Drofman, 1996; Den Hartong et al., 1999;

Bass, 1997], whereas specific behaviours might vary across cultures [Jung et al.,

1995]. Furthermore, transformational leadership, according to Bass [1997] and

Den Hartog et al. [1999], tended to show that leadership behaviours were

“culture-free” when considering different types of universals. Accordingly, the

following three hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 1: that the four cultural dimensions of Thai subordinates will

not significantly explain the variance in the transformational leadership

behaviour exhibited by Australian managers.

Hypothesis 2: that the four cultural dimensions of Thai subordinates will

not significantly explain the variance in the transactional leadership behaviour

exhibited by Australian managers.

Hypothesis 3: that the four cultural dimensions of Thai subordinates will

not significantly explain the variance in the laissez-faire leadership behaviour

exhibited by Australian managers.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Muenjohn and Armstrong

Volume 2, Number 2, December 2007

271

4. METHODOLOGY

This discussion of methodology covers sample (4.1), instruments (4.2), and

methods (4.3).

4.1. Sample

Thai subordinates who worked under Australian expatriates in Thailand

were identified as the target population. According to the Directory of Members

of the Australian-Thai Chamber of Commerce in Bangkok, 95 Australian

expatriates working in Thailand met the criterion for participation in this study.

It was revealed that, at the time, there were 221 Thai subordinates who “directly

reported” to 95 Australian managers. As a result, these 221 were treated as the

population of Thai subordinates in this study. This suggested that the ratio of 2

Thai subordinates per 1 Australian manager (221 divided by 95 = 2.3) should be

used in the study. Consequently, the ratio produced the sample size of 190 direct-

reporting Thai subordinates. This sample size represented 86% of the total

population.

Initially, this study attempted to calculate a suitable sample size by

considering other formulas or methods; for example, the formula for calculating

the sample size based on a known population size developed by Krejcie and

Morgan [1970]. Within this formula, a 95% level of confidence and a 5% degree

of error were adopted. The formula was:

n = χ² NP (1-P) / [d² (N-1) + χ² P (1-P)]

n = 3.841 x 221 x 0.2 (1-0.2) / [0.05²(221-1) + 3.841 x 0.2 (1-0.2)]

n = 115.86, or the sample size would consist of 115 Thai subordinates.

Considering the sample size above, the ratio of Thai subordinates per 1

Australian manager would be 1:1 (115 divided by 95 = 1.2), which was not

recommended for the lower-level raters because of the protection of the

anonymity of the raters [Bass and Avolio, 1997]. As a result, two Thai

subordinates were selected by each Australian superior to complete the

questionnaires.

4.2. Instruments

Leadership behaviours displayed by Australian expatriates were measured

by the “Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire” (MLQ 5x-short) developed by

Bass and Avolio [1997]. The MLQ 5x-short contained 45 items, tapping nine

conceptually distinct leadership factors. Five scales were identified as

characteristics of transformational leadership (idealized influence attributed and

behaviour, inspirational motivation, individual consideration, and intellectual

stimulation). Three scales were defined as characteristic of transactional

leadership (contingent reward, management-by-exception-active, and

management-by-exception-passive). One scale was described as non-leadership

(laissez-faire). Participants were asked on the questionnaire to judge how

frequently expatriate managers displayed their behaviours, using this five-item

Volume 2, Number 2, December 2007

271

4. METHODOLOGY

This discussion of methodology covers sample (4.1), instruments (4.2), and

methods (4.3).

4.1. Sample

Thai subordinates who worked under Australian expatriates in Thailand

were identified as the target population. According to the Directory of Members

of the Australian-Thai Chamber of Commerce in Bangkok, 95 Australian

expatriates working in Thailand met the criterion for participation in this study.

It was revealed that, at the time, there were 221 Thai subordinates who “directly

reported” to 95 Australian managers. As a result, these 221 were treated as the

population of Thai subordinates in this study. This suggested that the ratio of 2

Thai subordinates per 1 Australian manager (221 divided by 95 = 2.3) should be

used in the study. Consequently, the ratio produced the sample size of 190 direct-

reporting Thai subordinates. This sample size represented 86% of the total

population.

Initially, this study attempted to calculate a suitable sample size by

considering other formulas or methods; for example, the formula for calculating

the sample size based on a known population size developed by Krejcie and

Morgan [1970]. Within this formula, a 95% level of confidence and a 5% degree

of error were adopted. The formula was:

n = χ² NP (1-P) / [d² (N-1) + χ² P (1-P)]

n = 3.841 x 221 x 0.2 (1-0.2) / [0.05²(221-1) + 3.841 x 0.2 (1-0.2)]

n = 115.86, or the sample size would consist of 115 Thai subordinates.

Considering the sample size above, the ratio of Thai subordinates per 1

Australian manager would be 1:1 (115 divided by 95 = 1.2), which was not

recommended for the lower-level raters because of the protection of the

anonymity of the raters [Bass and Avolio, 1997]. As a result, two Thai

subordinates were selected by each Australian superior to complete the

questionnaires.

4.2. Instruments

Leadership behaviours displayed by Australian expatriates were measured

by the “Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire” (MLQ 5x-short) developed by

Bass and Avolio [1997]. The MLQ 5x-short contained 45 items, tapping nine

conceptually distinct leadership factors. Five scales were identified as

characteristics of transformational leadership (idealized influence attributed and

behaviour, inspirational motivation, individual consideration, and intellectual

stimulation). Three scales were defined as characteristic of transactional

leadership (contingent reward, management-by-exception-active, and

management-by-exception-passive). One scale was described as non-leadership

(laissez-faire). Participants were asked on the questionnaire to judge how

frequently expatriate managers displayed their behaviours, using this five-item

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Transformational Leadership:

The Influence of Culture on Leadership Behaviours

International Journal of Business and Information

272

scale: 0 = not at all, 1 = once in a while, 2 = sometimes, 3 = fairly often, and 4 =

frequently, if not always.

The Values Survey Module (VSM) was used to identify the four cultural

dimensions of the Thai subordinates [Hofstede, 1984]. The VSM was a product

of an international attitude survey program held between 1967 and 1973, using

about 117,000 survey questionnaires from 66 countries. It produced the scores of

the four cultural dimensions; namely, power distance (PDI), uncertainty

avoidance (UAI), individualism (IDV), and masculinity (MAS). The VSM used

in this study consisted of 14 items selected from the original VSM, but shorter, to

overcome the low response rate to mailed questionnaires [Sekaran, 2000]. The

three questions measuring PDI and the three questions representing UAI were

kept in the short version. The difference was that the 14 work goal items were

reduced to 8 in this version. Four work goal items represented the MAS

dimension, and another four items measured the IDV dimension. In order to

minimize cultural and language problems, the questionnaires were first translated

formally from English to Thai by a Thai native translator from the Royal Thai

Consulate General in Melbourne, and then, when completed, independently re-

translated back to English by the researcher.

4.3. Method

To answer the research question, a series of multiple-regression analyses

was employed. Multiple-regression analysis provides statistical results showing

how much of the variance in the dependent variable can be explained when

several independent variables are examined [Punch, 1998]. In the multiple-

regression equation, various values for the dependent variable are predicted by

the corresponding values for the independent variables when the intercept and

regression coefficients are constants. In addition, the analysis also statistically

computes the estimate effect of each independent variable on the dependent

variable while simultaneously controlling for the effects of other independent

variables [Singleton, Straits, and Straits, 1993].

In this study, the power distance, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity, and

individualism cultural dimensions were presented as the group of independent

variables while transformational, transactional, and non-leadership behaviour

was treated separately as dependent variables.

The analysis used a two-step approach proposed by Haire, Rolph, Ronald,

and William [1998], particularly recommended when the data analyst has little

previous knowledge about relationships among the set of variables. In the first

step, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was initially used to test the

overall effect of the set of independent variables (i.e., power distance,

individualism, masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance) on the set of dependent

variables (transformational, transactional, and non-leadership). Then, a set of

multiple-regression analysis was conducted separately to test hypothesis 1, 2, and

3 concerning the possible effect of the four cultural dimensions on the three

individual leadership behaviours.

The Influence of Culture on Leadership Behaviours

International Journal of Business and Information

272

scale: 0 = not at all, 1 = once in a while, 2 = sometimes, 3 = fairly often, and 4 =

frequently, if not always.

The Values Survey Module (VSM) was used to identify the four cultural

dimensions of the Thai subordinates [Hofstede, 1984]. The VSM was a product

of an international attitude survey program held between 1967 and 1973, using

about 117,000 survey questionnaires from 66 countries. It produced the scores of

the four cultural dimensions; namely, power distance (PDI), uncertainty

avoidance (UAI), individualism (IDV), and masculinity (MAS). The VSM used

in this study consisted of 14 items selected from the original VSM, but shorter, to

overcome the low response rate to mailed questionnaires [Sekaran, 2000]. The

three questions measuring PDI and the three questions representing UAI were

kept in the short version. The difference was that the 14 work goal items were

reduced to 8 in this version. Four work goal items represented the MAS

dimension, and another four items measured the IDV dimension. In order to

minimize cultural and language problems, the questionnaires were first translated

formally from English to Thai by a Thai native translator from the Royal Thai

Consulate General in Melbourne, and then, when completed, independently re-

translated back to English by the researcher.

4.3. Method

To answer the research question, a series of multiple-regression analyses

was employed. Multiple-regression analysis provides statistical results showing

how much of the variance in the dependent variable can be explained when

several independent variables are examined [Punch, 1998]. In the multiple-

regression equation, various values for the dependent variable are predicted by

the corresponding values for the independent variables when the intercept and

regression coefficients are constants. In addition, the analysis also statistically

computes the estimate effect of each independent variable on the dependent

variable while simultaneously controlling for the effects of other independent

variables [Singleton, Straits, and Straits, 1993].

In this study, the power distance, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity, and

individualism cultural dimensions were presented as the group of independent

variables while transformational, transactional, and non-leadership behaviour

was treated separately as dependent variables.

The analysis used a two-step approach proposed by Haire, Rolph, Ronald,

and William [1998], particularly recommended when the data analyst has little

previous knowledge about relationships among the set of variables. In the first

step, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was initially used to test the

overall effect of the set of independent variables (i.e., power distance,

individualism, masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance) on the set of dependent

variables (transformational, transactional, and non-leadership). Then, a set of

multiple-regression analysis was conducted separately to test hypothesis 1, 2, and

3 concerning the possible effect of the four cultural dimensions on the three

individual leadership behaviours.

Muenjohn and Armstrong

Volume 2, Number 2, December 2007

273

5. RESULTS

A reliability check for both the English MLQ and Thai MLQ was conducted

to provide evidence that the leadership instruments, especially after being

translated from English to Thai, produced the data for which they were designed.

As Cronbach‟s coefficient alpha was provided as a standard measure of

reliability, 45 items were included in the calculations to identify reliability

coefficients for the English and Thai MLQs. The values of Cronbach alpha

produced were alpha = 0.86 for the original MLQ and alpha = 0.87 for the

translated MLQ. The reliability values gained from both MLQs were greater than

0.70, indicating an acceptable statistical testing level [Nunnally, 1967]. It also

indicated that the scales were highly reliable and that the reliability of the Thai

translated version was similar to that of the English version. The VSM

instrument, when checked for reliability, produced the value of reliability

coefficient (alpha) = 0.60. This reliability value was slightly below Nunnally‟s

[1978] standard of 0.70. It is noted that a low reliability value was one of the

major concern about the VSM instrument [see, for example, Helgstrand and

Stuhlmacher, 1999; and Kuchinke, 1999].

5.1. Participants

Ninety-one useable questionnaires were returned, representing a response

rate of approximately 48%. A similar number of male and female Thai

subordinates participated in this study. There were 44 (48.4%) male participants

and 47 (51.6%) female, aged relatively young (82.4% below age 39), and the

majority had university experience (83.5% with at least bachelor‟s degree or

better). The average age of Thai participants was between 30 and 39 years, and a

bachelor‟s degree was the mode level of their education. The results also

indicated that 49 (53.8%) Thai subordinates held positions at the middle-

management level. Most participants (88.0%) had been working for their present

organisations for longer than one year. The mode employment period with their

present companies was more than 3 years.

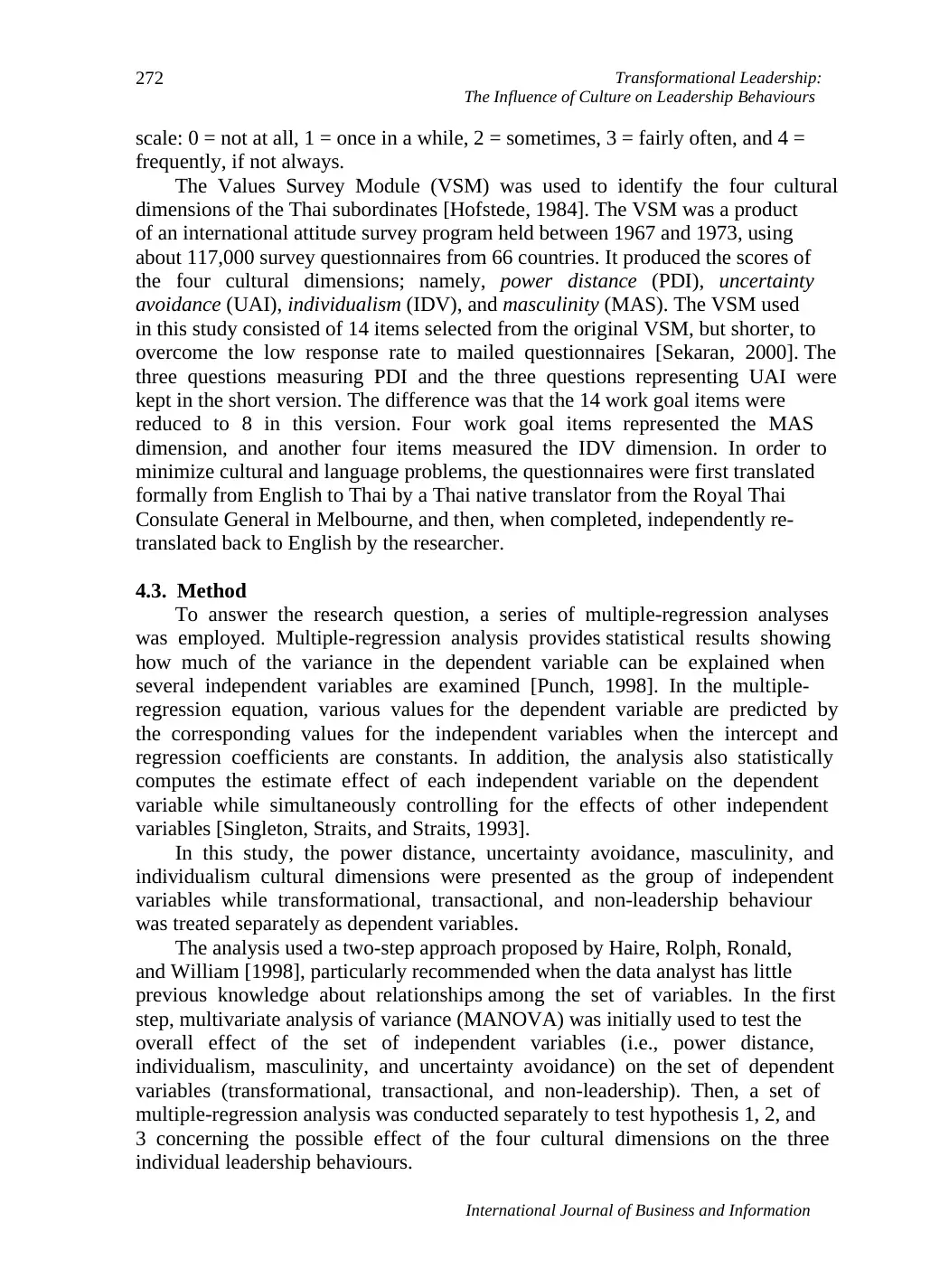

5.2. Effects of Cultural Dimensions and Leadership Behaviours

The results in Table 1 indicate that the main effects of PDI, UAI, MAS, and

IDV were found to be not statistically significant, and that changes in the four

cultural dimensions did not significantly affect the three leadership behaviours.

Table 1

MANOVA Results

Main Effect Pillai’s Trace Wilks’

Lamba

F value Hypothesis

df

Error df Sig.

PDI 1.405 .009 1.190 12 2.937 .50

UAI 1.781 .008 1.026 15 3.132 .56

MAS 1.659 .004 1.792 12 2.937 .35

IDV 2.387 .001 1.485 21 3.422 .40

PDI = power distance. UAI = uncertainty avoidance. MAS = masculinity.

IDV = individualism

Volume 2, Number 2, December 2007

273

5. RESULTS

A reliability check for both the English MLQ and Thai MLQ was conducted

to provide evidence that the leadership instruments, especially after being

translated from English to Thai, produced the data for which they were designed.

As Cronbach‟s coefficient alpha was provided as a standard measure of

reliability, 45 items were included in the calculations to identify reliability

coefficients for the English and Thai MLQs. The values of Cronbach alpha

produced were alpha = 0.86 for the original MLQ and alpha = 0.87 for the

translated MLQ. The reliability values gained from both MLQs were greater than

0.70, indicating an acceptable statistical testing level [Nunnally, 1967]. It also

indicated that the scales were highly reliable and that the reliability of the Thai

translated version was similar to that of the English version. The VSM

instrument, when checked for reliability, produced the value of reliability

coefficient (alpha) = 0.60. This reliability value was slightly below Nunnally‟s

[1978] standard of 0.70. It is noted that a low reliability value was one of the

major concern about the VSM instrument [see, for example, Helgstrand and

Stuhlmacher, 1999; and Kuchinke, 1999].

5.1. Participants

Ninety-one useable questionnaires were returned, representing a response

rate of approximately 48%. A similar number of male and female Thai

subordinates participated in this study. There were 44 (48.4%) male participants

and 47 (51.6%) female, aged relatively young (82.4% below age 39), and the

majority had university experience (83.5% with at least bachelor‟s degree or

better). The average age of Thai participants was between 30 and 39 years, and a

bachelor‟s degree was the mode level of their education. The results also

indicated that 49 (53.8%) Thai subordinates held positions at the middle-

management level. Most participants (88.0%) had been working for their present

organisations for longer than one year. The mode employment period with their

present companies was more than 3 years.

5.2. Effects of Cultural Dimensions and Leadership Behaviours

The results in Table 1 indicate that the main effects of PDI, UAI, MAS, and

IDV were found to be not statistically significant, and that changes in the four

cultural dimensions did not significantly affect the three leadership behaviours.

Table 1

MANOVA Results

Main Effect Pillai’s Trace Wilks’

Lamba

F value Hypothesis

df

Error df Sig.

PDI 1.405 .009 1.190 12 2.937 .50

UAI 1.781 .008 1.026 15 3.132 .56

MAS 1.659 .004 1.792 12 2.937 .35

IDV 2.387 .001 1.485 21 3.422 .40

PDI = power distance. UAI = uncertainty avoidance. MAS = masculinity.

IDV = individualism

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Transformational Leadership:

The Influence of Culture on Leadership Behaviours

International Journal of Business and Information

274

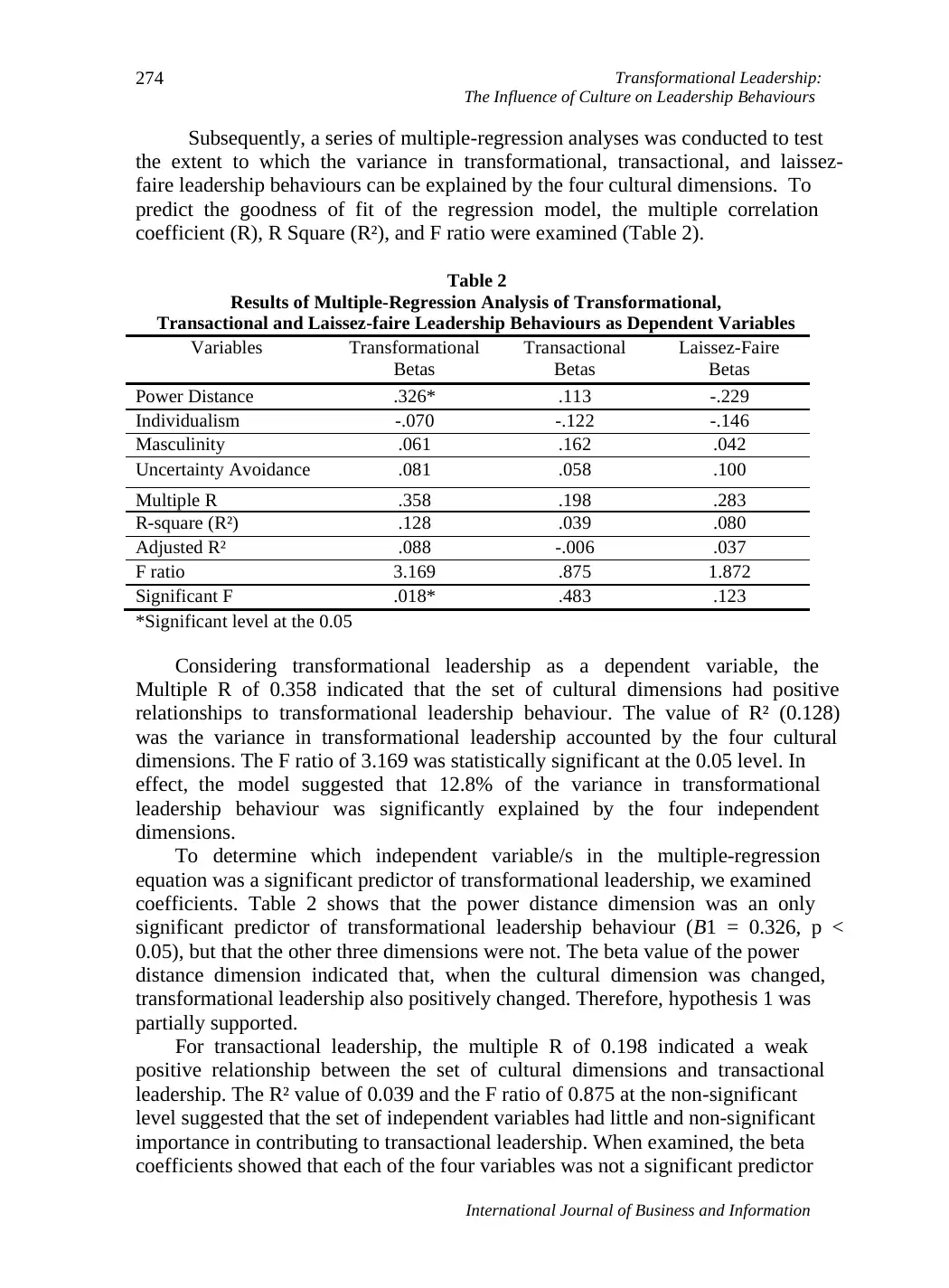

Subsequently, a series of multiple-regression analyses was conducted to test

the extent to which the variance in transformational, transactional, and laissez-

faire leadership behaviours can be explained by the four cultural dimensions. To

predict the goodness of fit of the regression model, the multiple correlation

coefficient (R), R Square (R²), and F ratio were examined (Table 2).

Table 2

Results of Multiple-Regression Analysis of Transformational,

Transactional and Laissez-faire Leadership Behaviours as Dependent Variables

Variables Transformational

Betas

Transactional

Betas

Laissez-Faire

Betas

Power Distance .326* .113 -.229

Individualism -.070 -.122 -.146

Masculinity .061 .162 .042

Uncertainty Avoidance .081 .058 .100

Multiple R .358 .198 .283

R-square (R²) .128 .039 .080

Adjusted R² .088 -.006 .037

F ratio 3.169 .875 1.872

Significant F .018* .483 .123

*Significant level at the 0.05

Considering transformational leadership as a dependent variable, the

Multiple R of 0.358 indicated that the set of cultural dimensions had positive

relationships to transformational leadership behaviour. The value of R² (0.128)

was the variance in transformational leadership accounted by the four cultural

dimensions. The F ratio of 3.169 was statistically significant at the 0.05 level. In

effect, the model suggested that 12.8% of the variance in transformational

leadership behaviour was significantly explained by the four independent

dimensions.

To determine which independent variable/s in the multiple-regression

equation was a significant predictor of transformational leadership, we examined

coefficients. Table 2 shows that the power distance dimension was an only

significant predictor of transformational leadership behaviour (B1 = 0.326, p <

0.05), but that the other three dimensions were not. The beta value of the power

distance dimension indicated that, when the cultural dimension was changed,

transformational leadership also positively changed. Therefore, hypothesis 1 was

partially supported.

For transactional leadership, the multiple R of 0.198 indicated a weak

positive relationship between the set of cultural dimensions and transactional

leadership. The R² value of 0.039 and the F ratio of 0.875 at the non-significant

level suggested that the set of independent variables had little and non-significant

importance in contributing to transactional leadership. When examined, the beta

coefficients showed that each of the four variables was not a significant predictor

The Influence of Culture on Leadership Behaviours

International Journal of Business and Information

274

Subsequently, a series of multiple-regression analyses was conducted to test

the extent to which the variance in transformational, transactional, and laissez-

faire leadership behaviours can be explained by the four cultural dimensions. To

predict the goodness of fit of the regression model, the multiple correlation

coefficient (R), R Square (R²), and F ratio were examined (Table 2).

Table 2

Results of Multiple-Regression Analysis of Transformational,

Transactional and Laissez-faire Leadership Behaviours as Dependent Variables

Variables Transformational

Betas

Transactional

Betas

Laissez-Faire

Betas

Power Distance .326* .113 -.229

Individualism -.070 -.122 -.146

Masculinity .061 .162 .042

Uncertainty Avoidance .081 .058 .100

Multiple R .358 .198 .283

R-square (R²) .128 .039 .080

Adjusted R² .088 -.006 .037

F ratio 3.169 .875 1.872

Significant F .018* .483 .123

*Significant level at the 0.05

Considering transformational leadership as a dependent variable, the

Multiple R of 0.358 indicated that the set of cultural dimensions had positive

relationships to transformational leadership behaviour. The value of R² (0.128)

was the variance in transformational leadership accounted by the four cultural

dimensions. The F ratio of 3.169 was statistically significant at the 0.05 level. In

effect, the model suggested that 12.8% of the variance in transformational

leadership behaviour was significantly explained by the four independent

dimensions.

To determine which independent variable/s in the multiple-regression

equation was a significant predictor of transformational leadership, we examined

coefficients. Table 2 shows that the power distance dimension was an only

significant predictor of transformational leadership behaviour (B1 = 0.326, p <

0.05), but that the other three dimensions were not. The beta value of the power

distance dimension indicated that, when the cultural dimension was changed,

transformational leadership also positively changed. Therefore, hypothesis 1 was

partially supported.

For transactional leadership, the multiple R of 0.198 indicated a weak

positive relationship between the set of cultural dimensions and transactional

leadership. The R² value of 0.039 and the F ratio of 0.875 at the non-significant

level suggested that the set of independent variables had little and non-significant

importance in contributing to transactional leadership. When examined, the beta

coefficients showed that each of the four variables was not a significant predictor

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Muenjohn and Armstrong

Volume 2, Number 2, December 2007

275

of the transactional dependent variable. As a result, hypothesis 2 was fully

supported.

Similar to the results obtained from those in the transactional leadership

regression model, the value of R² (0.080) and the F ratio of 1.872 at non-

significant levels suggested that the variation in laissez-faire leadership was not

significantly explained by the four independent dimensions. The beta coefficients

also suggested that none of the independent variables were significant predictors

of the laissez-faire leadership. As a result, hypothesis 3 was fully supported.

6. DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATION

The results indicated that the four cultural values of Thai subordinates had a

very limited role in explaining the variance in transformational, transactional, and

non-leadership behaviours exhibited by Australian managers. The very limited

influence of the cultural dimensions on the three major leadership behaviours

seemed to support the universality of the transformational-transactional paradigm

proposed by Bass [1997].

Transformational leadership, according to Bass and Avolio [1997], raises

subordinates‟ awareness of the importance of desired outcomes, stimulates

subordinates‟ views of their work from new perspectives, develops subordinates

to higher levels of their ability and potential, and motivates subordinates to

transcend self-interest for the good of the organisation. These leadership

behaviours seem to be the ideal leadership behaviours for subordinates across

countries or cultures.

That transformational leadership helps increase subordinates‟ satisfaction,

enhance their effort, and allow them to be more effective has been reported by

several studies, whether they were conducted in Asia [e.g., Singer and Singer,

1990], North America [e.g., Sosik, 1997), Europe [e.g., Geyer and Steyrer, 1998]

or Asia-Pacific [e.g., Ingram, 1997]. When transformational leadership was

conducted in comparative cross-national studies, the attributes associated with

transformational leadership were seen as contributing to outstanding leadership

worldwide [Hartog et al., 1999]. Similar results were also found to apply in a

variety of organisations such as in the military [Atwater and Yammarino, 1993],

health [Medley and Larochelle, 1995], and informational technology [Thite,

1999]. Data even came from the study of leaders at different levels, such as in a

sample of teachers [Ingram, 1997], middle managers [Carless, Mann, and

Wearing, 1996], and executive leaders [Church and Waclawski, 1998].

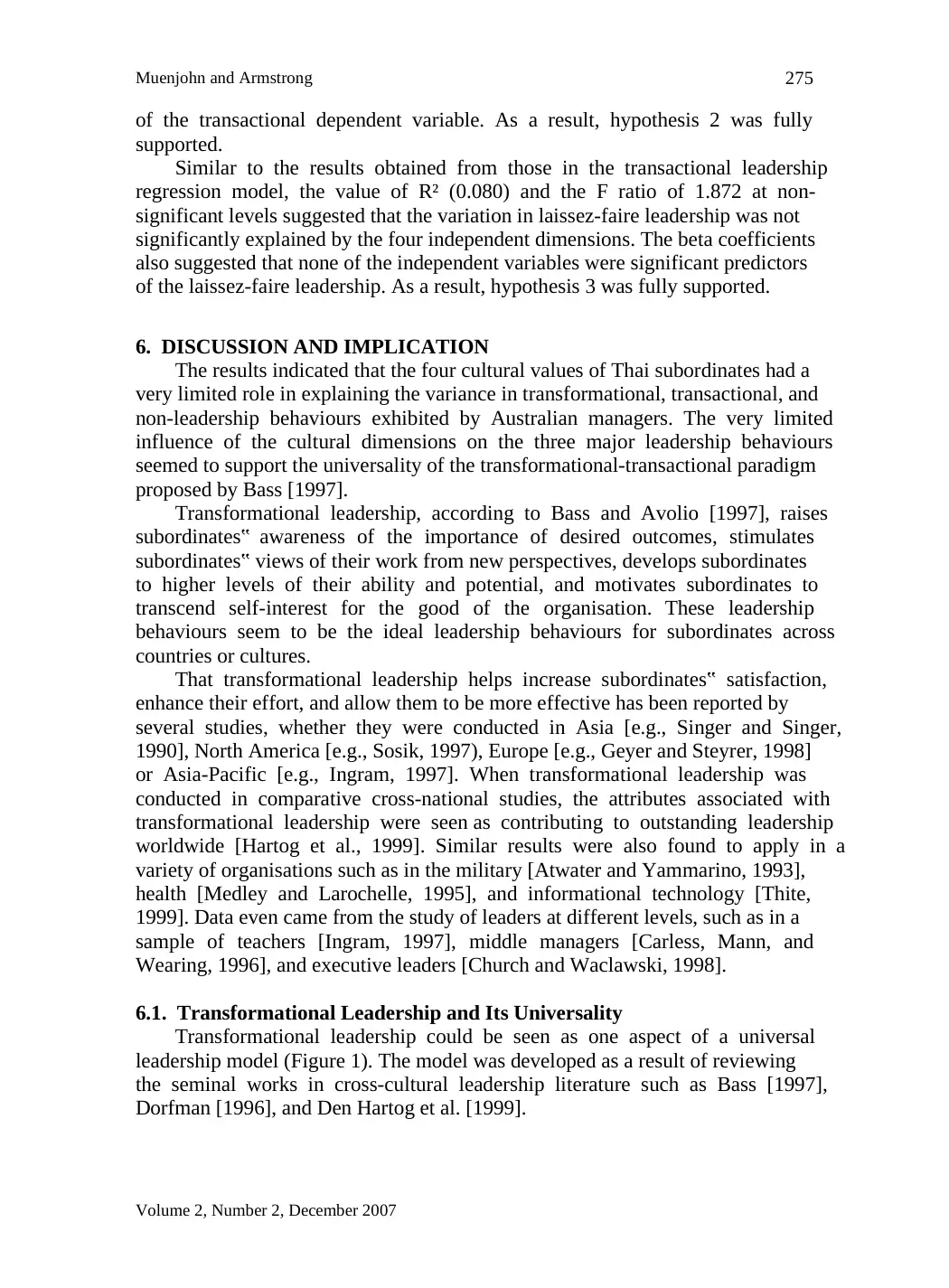

6.1. Transformational Leadership and Its Universality

Transformational leadership could be seen as one aspect of a universal

leadership model (Figure 1). The model was developed as a result of reviewing

the seminal works in cross-cultural leadership literature such as Bass [1997],

Dorfman [1996], and Den Hartog et al. [1999].

Volume 2, Number 2, December 2007

275

of the transactional dependent variable. As a result, hypothesis 2 was fully

supported.

Similar to the results obtained from those in the transactional leadership

regression model, the value of R² (0.080) and the F ratio of 1.872 at non-

significant levels suggested that the variation in laissez-faire leadership was not

significantly explained by the four independent dimensions. The beta coefficients

also suggested that none of the independent variables were significant predictors

of the laissez-faire leadership. As a result, hypothesis 3 was fully supported.

6. DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATION

The results indicated that the four cultural values of Thai subordinates had a

very limited role in explaining the variance in transformational, transactional, and

non-leadership behaviours exhibited by Australian managers. The very limited

influence of the cultural dimensions on the three major leadership behaviours

seemed to support the universality of the transformational-transactional paradigm

proposed by Bass [1997].

Transformational leadership, according to Bass and Avolio [1997], raises

subordinates‟ awareness of the importance of desired outcomes, stimulates

subordinates‟ views of their work from new perspectives, develops subordinates

to higher levels of their ability and potential, and motivates subordinates to

transcend self-interest for the good of the organisation. These leadership

behaviours seem to be the ideal leadership behaviours for subordinates across

countries or cultures.

That transformational leadership helps increase subordinates‟ satisfaction,

enhance their effort, and allow them to be more effective has been reported by

several studies, whether they were conducted in Asia [e.g., Singer and Singer,

1990], North America [e.g., Sosik, 1997), Europe [e.g., Geyer and Steyrer, 1998]

or Asia-Pacific [e.g., Ingram, 1997]. When transformational leadership was

conducted in comparative cross-national studies, the attributes associated with

transformational leadership were seen as contributing to outstanding leadership

worldwide [Hartog et al., 1999]. Similar results were also found to apply in a

variety of organisations such as in the military [Atwater and Yammarino, 1993],

health [Medley and Larochelle, 1995], and informational technology [Thite,

1999]. Data even came from the study of leaders at different levels, such as in a

sample of teachers [Ingram, 1997], middle managers [Carless, Mann, and

Wearing, 1996], and executive leaders [Church and Waclawski, 1998].

6.1. Transformational Leadership and Its Universality

Transformational leadership could be seen as one aspect of a universal

leadership model (Figure 1). The model was developed as a result of reviewing

the seminal works in cross-cultural leadership literature such as Bass [1997],

Dorfman [1996], and Den Hartog et al. [1999].

Transformational Leadership:

The Influence of Culture on Leadership Behaviours

International Journal of Business and Information

276

The model in Figure 1 presents two important forces in enhancing the

universality of transformational leadership: internal- and external-driven forces.

The internal-driven force refers to the contents or attributions that operate within

transformational leadership in contributing to universal leadership. These

attributions include four components: simple universal, systematic behaviour

universal, functional universal, and flexibility [Bass, 1997].

Figure 1. The Universality of the Transformational Leadership Model

The second factor is externally driven environmental forces that help to boost

the perceptions of transformational leadership worldwide.

For the internal driven forces, the universality of the transformational

leadership is associated with three different types of universal phenomena.

Transformational leadership was consistent with the type of “simple universal”

that was described as a phenomenon, which is constant throughout the world. In

this regard, transformational leadership, regardless of cultures, has been

perceived as the most desired leadership behaviours when compared with the

other two leadership behaviours.

Transformational

Leadership

Patterns of

universal

leadership

behaviours

Internal Driven Forces

Simple universal

Systematic behaviour universal

Functional universal

Flexibility

External driven forces

Perceptional convergence

Pre-requirement of new

leadership

leadership

The Influence of Culture on Leadership Behaviours

International Journal of Business and Information

276

The model in Figure 1 presents two important forces in enhancing the

universality of transformational leadership: internal- and external-driven forces.

The internal-driven force refers to the contents or attributions that operate within

transformational leadership in contributing to universal leadership. These

attributions include four components: simple universal, systematic behaviour

universal, functional universal, and flexibility [Bass, 1997].

Figure 1. The Universality of the Transformational Leadership Model

The second factor is externally driven environmental forces that help to boost

the perceptions of transformational leadership worldwide.

For the internal driven forces, the universality of the transformational

leadership is associated with three different types of universal phenomena.

Transformational leadership was consistent with the type of “simple universal”

that was described as a phenomenon, which is constant throughout the world. In

this regard, transformational leadership, regardless of cultures, has been

perceived as the most desired leadership behaviours when compared with the

other two leadership behaviours.

Transformational

Leadership

Patterns of

universal

leadership

behaviours

Internal Driven Forces

Simple universal

Systematic behaviour universal

Functional universal

Flexibility

External driven forces

Perceptional convergence

Pre-requirement of new

leadership

leadership

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 19

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.