Transformational Leadership: Models, Factors, and Outcomes Explained

VerifiedAdded on 2021/07/20

|26

|15172

|254

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive overview of transformational leadership, a complex process that binds leaders and followers in transformative change. It explores the core concepts, distinguishing between transformational and transactional leadership, and highlighting the role of charismatic leadership. The report delves into the transformational leadership model, outlining its eight key factors, including idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration, as well as transactional and non-leadership factors. It also discusses other perspectives of transformational leadership, including models developed by Bennis and Nanus, and Kouzes and Posner. The report emphasizes the positive outcomes of transformational leadership, which inspires followers to work for the good of the organization, and subordinate their own self-interests to those of the organization.

258

TransformationalTransformational

LeadershipLeadership

Leaders who can spark our imaginations with a compelling vision of a worth-

while end that stretches us beyond what is known today and who can show us a

clear path to our objectives are the ones we follow. In the future, the leadership

role will focus more on the development of an effective strategy, the creation of the

vision, and an understanding of their impact, and will empower others to carry

out the implementation of the plan.

—Goldsmith, Greenberg, Robertson, & Hu-Chan (2003, p. 118)

Transformational leadership is an involved, complex process that binds leaders and

followers together in the transformation or changing of followers, organizations, or

even whole nations.It involves leaders interacting with followers with respect to

their “emotions,values,ethics,standards,and long-term goals,and includes assessing

followers’motives,satisfying theirneeds,and treating them asfull human beings”

(Northouse,2010). While alltheories of leadership involve influence,transformational

leadership is aboutan extraordinary ability to influence thatencourages followers to

achieve something well above what was expected by themselves or their leaders.

Early researchersin the areaof transformationalleadership coined theterm

(Downton,1973) and tried to integrate the responsibilities ofleaders and followers

(Burns, 1978). In particular, Burns (1978) described leaders as people who could under-

stand the motives of followers and, therefore, be able to achieve the goals of followers and

leaders.As we discussed in Chapter 1,he considered leadership different from power

because leadership is a concept that cannot be separated from the needs of followers.

C H A P T E R

5

C H A P T E R

9

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

TransformationalTransformational

LeadershipLeadership

Leaders who can spark our imaginations with a compelling vision of a worth-

while end that stretches us beyond what is known today and who can show us a

clear path to our objectives are the ones we follow. In the future, the leadership

role will focus more on the development of an effective strategy, the creation of the

vision, and an understanding of their impact, and will empower others to carry

out the implementation of the plan.

—Goldsmith, Greenberg, Robertson, & Hu-Chan (2003, p. 118)

Transformational leadership is an involved, complex process that binds leaders and

followers together in the transformation or changing of followers, organizations, or

even whole nations.It involves leaders interacting with followers with respect to

their “emotions,values,ethics,standards,and long-term goals,and includes assessing

followers’motives,satisfying theirneeds,and treating them asfull human beings”

(Northouse,2010). While alltheories of leadership involve influence,transformational

leadership is aboutan extraordinary ability to influence thatencourages followers to

achieve something well above what was expected by themselves or their leaders.

Early researchersin the areaof transformationalleadership coined theterm

(Downton,1973) and tried to integrate the responsibilities ofleaders and followers

(Burns, 1978). In particular, Burns (1978) described leaders as people who could under-

stand the motives of followers and, therefore, be able to achieve the goals of followers and

leaders.As we discussed in Chapter 1,he considered leadership different from power

because leadership is a concept that cannot be separated from the needs of followers.

C H A P T E R

5

C H A P T E R

9

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Chapter 9: TransformationalLeadership 259

Burns (1978) differentiated between transactional and transformational leadership.

He described transactional leadership as that which emphasizes exchanges between fol-

lowers and leaders. This idea of exchange is easily seen at most levels in many different

types of organizations.

He described transformationalleadership as thatprocess through which leaders

engage with followers and develop a connection (one that did not previously exist) that

increases the morals and motivation ofthe follower and the leader.Because ofthis

process, leaders assist followers in achieving their potential to the fullest (Yukl, 2006).

Bass and colleagues (Bass, 1998; Bass & Riggio, 2006; Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999) dif-

ferentiated between leadership that raised the morals of followers and that which trans-

formed people,organizations,and nationsin a negative manner.They called this

pseudotransformational leadership, to describe leaders who are power hungry, have per-

verted moral values, and are exploitative. In particular, this form of leadership empha-

sizes the leader’s self-interest in a manner that is self-aggrandizing and contrary to the

interests of his or her followers (Northouse, 2010). Kenneth Lay and Jeff Skilling might

be examples of this form of leadership in their roles as chair and CEO of Enron, respec-

tively. Authentic transformational leaders put the interests of followers above their own

interestsand,in so doing,emphasize the collective good for leadersand followers

(Howell & Avolio, 1992).

Charismatic Leadership

“Charisma is a specialquality ofleaders whose purposes,powers,and extraordinary

determination differentiate them from others” (Dubrin,2007,p. 68).Weber (1947)

emphasized the extraordinary nature of this personality trait but also argued that follow-

ers were important in that they confirmed that their leaders had charisma (Bryman, 1992

House, 1976). The influence exercised by charismatic leaders comes from their personal

power,not their position power.Their personalqualities help their personalpower to

transcend the influence they have from position power (Daft, 2005).

House (1976) provided a theory of charismatic leadership that linked personality char

acteristics to leader behaviors and,through leader behaviors,effects on followers. Weber

(1947) and House (1976) both argued that these effects would be more likely to happen

when followers were in stressful situations because this is when followers want deliveran

from their problems. A major revision to House’s conceptualization has been offered by

Shamir, House, and Arthur (1993). They argue that charismatic leadership transforms ho

followers view themselves and strives to tie each follower’s identity to the organization’s

lective identity (Northouse, 2010). In other words, charismatic leadership is effective bec

each follower’s sense of identity is linked to the identity of his or her organization.

A Transformational Leadership Model

Bass and his colleagues (Avolio, 1999; Bass, 1985, 1990; Bass & Avolio, 1993, 1994) refin

and expanded the models suggested by Burns (1978) and House (1976). Bass (1985) add

to Burns’s model by focusing more on the needs of followers than on the needs of leader

focusing on situations where the outcomes could be negative, and by placing transforma

tional and transactional leadership on a single continuum as opposed to considering them

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

Burns (1978) differentiated between transactional and transformational leadership.

He described transactional leadership as that which emphasizes exchanges between fol-

lowers and leaders. This idea of exchange is easily seen at most levels in many different

types of organizations.

He described transformationalleadership as thatprocess through which leaders

engage with followers and develop a connection (one that did not previously exist) that

increases the morals and motivation ofthe follower and the leader.Because ofthis

process, leaders assist followers in achieving their potential to the fullest (Yukl, 2006).

Bass and colleagues (Bass, 1998; Bass & Riggio, 2006; Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999) dif-

ferentiated between leadership that raised the morals of followers and that which trans-

formed people,organizations,and nationsin a negative manner.They called this

pseudotransformational leadership, to describe leaders who are power hungry, have per-

verted moral values, and are exploitative. In particular, this form of leadership empha-

sizes the leader’s self-interest in a manner that is self-aggrandizing and contrary to the

interests of his or her followers (Northouse, 2010). Kenneth Lay and Jeff Skilling might

be examples of this form of leadership in their roles as chair and CEO of Enron, respec-

tively. Authentic transformational leaders put the interests of followers above their own

interestsand,in so doing,emphasize the collective good for leadersand followers

(Howell & Avolio, 1992).

Charismatic Leadership

“Charisma is a specialquality ofleaders whose purposes,powers,and extraordinary

determination differentiate them from others” (Dubrin,2007,p. 68).Weber (1947)

emphasized the extraordinary nature of this personality trait but also argued that follow-

ers were important in that they confirmed that their leaders had charisma (Bryman, 1992

House, 1976). The influence exercised by charismatic leaders comes from their personal

power,not their position power.Their personalqualities help their personalpower to

transcend the influence they have from position power (Daft, 2005).

House (1976) provided a theory of charismatic leadership that linked personality char

acteristics to leader behaviors and,through leader behaviors,effects on followers. Weber

(1947) and House (1976) both argued that these effects would be more likely to happen

when followers were in stressful situations because this is when followers want deliveran

from their problems. A major revision to House’s conceptualization has been offered by

Shamir, House, and Arthur (1993). They argue that charismatic leadership transforms ho

followers view themselves and strives to tie each follower’s identity to the organization’s

lective identity (Northouse, 2010). In other words, charismatic leadership is effective bec

each follower’s sense of identity is linked to the identity of his or her organization.

A Transformational Leadership Model

Bass and his colleagues (Avolio, 1999; Bass, 1985, 1990; Bass & Avolio, 1993, 1994) refin

and expanded the models suggested by Burns (1978) and House (1976). Bass (1985) add

to Burns’s model by focusing more on the needs of followers than on the needs of leader

focusing on situations where the outcomes could be negative, and by placing transforma

tional and transactional leadership on a single continuum as opposed to considering them

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

260 CASES IN LEADERSHIP

independent continua. He extended House’s model by emphasizing the emotional compo-

nents of charisma and by arguing that while charisma may be a necessary condition for

transformational leadership, it is not a sufficient condition—more than charisma is needed.

Transformationalleadership inspires subordinates to achieve more than expected

because (a) itincreases individuals’awareness regarding the significance oftask out-

comes, (b) it encourages subordinates to go beyond their own self-interest to the interests

of others in their team and organization, and (c) it motivates subordinates to take care of

needs that operate at a higher level (Bass, 1985; Yukl, 2006).

There are eight factors in the transformational and transactional leadership model.

These are separated into three types of factors: (1) transformational factors consisting of

idealized influence, individualized consideration, inspirational motivation, and intellec-

tual stimulation; (2) transactional factors consisting of contingent reward, management by

exception (active), and management by exception (passive); and (3) one nontransformatio

nontransactional factor, that being laissez-faire (Yukl, 2006).

Transformational Leadership Factors

This form of leadership is about improving each follower’s performance and helping fol-

lowers develop to their highest potential (Avolio, 1999; Bass & Avolio, 1990). In addition,

transformational leaders move subordinates to work for the interests of others over and

above their own interests and, in so doing, cause significant, positive changes to happen

for the good of the team and organization (Dubrin, 2007; Kuhnert, 1994).

Idealized Influence or Charisma. Leaders with this factor are strong role models followers

want to emulate and with whom they want to identify. They generally exhibit very high

moral and ethical standards of conduct and usually do the right thing when confronted

with ethicaland moralchoices. Followers develop a deep respect for these leaders and

generally have a high level of trust in them. These leaders give followers a shared vision

and a strong sense of mission with which followers identify (Northouse, 2010).

InspirationalMotivation.Leaders with this factor share high expectations with followers

and motivate them to share in the organization’s vision with a high degree of commitment

These leaders encourage followers to achieve more in the interests of the group than they

would if they tried to achieve their own self-interests. These leaders increase team spirit

through coaching, encouraging, and supporting followers (Yukl, 2006).

Intellectual Stimulation. Leaders with this factor encourage subordinates to be innovative

and creative. These leaders support followers as they challenge the deeply held beliefs and

values of their leaders, their organizations, and themselves. This encourages followers to

innovatively handle organizational problems (Yukl, 2006).

Individualized Consideration. Leaders with this factor are very supportive and take great ca

to listen to and understand their followers’ needs. They appropriately coach and give advic

to their followers and help them to achieve self-actualization. These leaders delegate to as

followers in developing through work-related challenges and care for employees in a way

appropriate for each employee. If employees need nurturance, the leader will nurture;if

employees need task structure, the leader will provide structure (Northouse, 2010).

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

independent continua. He extended House’s model by emphasizing the emotional compo-

nents of charisma and by arguing that while charisma may be a necessary condition for

transformational leadership, it is not a sufficient condition—more than charisma is needed.

Transformationalleadership inspires subordinates to achieve more than expected

because (a) itincreases individuals’awareness regarding the significance oftask out-

comes, (b) it encourages subordinates to go beyond their own self-interest to the interests

of others in their team and organization, and (c) it motivates subordinates to take care of

needs that operate at a higher level (Bass, 1985; Yukl, 2006).

There are eight factors in the transformational and transactional leadership model.

These are separated into three types of factors: (1) transformational factors consisting of

idealized influence, individualized consideration, inspirational motivation, and intellec-

tual stimulation; (2) transactional factors consisting of contingent reward, management by

exception (active), and management by exception (passive); and (3) one nontransformatio

nontransactional factor, that being laissez-faire (Yukl, 2006).

Transformational Leadership Factors

This form of leadership is about improving each follower’s performance and helping fol-

lowers develop to their highest potential (Avolio, 1999; Bass & Avolio, 1990). In addition,

transformational leaders move subordinates to work for the interests of others over and

above their own interests and, in so doing, cause significant, positive changes to happen

for the good of the team and organization (Dubrin, 2007; Kuhnert, 1994).

Idealized Influence or Charisma. Leaders with this factor are strong role models followers

want to emulate and with whom they want to identify. They generally exhibit very high

moral and ethical standards of conduct and usually do the right thing when confronted

with ethicaland moralchoices. Followers develop a deep respect for these leaders and

generally have a high level of trust in them. These leaders give followers a shared vision

and a strong sense of mission with which followers identify (Northouse, 2010).

InspirationalMotivation.Leaders with this factor share high expectations with followers

and motivate them to share in the organization’s vision with a high degree of commitment

These leaders encourage followers to achieve more in the interests of the group than they

would if they tried to achieve their own self-interests. These leaders increase team spirit

through coaching, encouraging, and supporting followers (Yukl, 2006).

Intellectual Stimulation. Leaders with this factor encourage subordinates to be innovative

and creative. These leaders support followers as they challenge the deeply held beliefs and

values of their leaders, their organizations, and themselves. This encourages followers to

innovatively handle organizational problems (Yukl, 2006).

Individualized Consideration. Leaders with this factor are very supportive and take great ca

to listen to and understand their followers’ needs. They appropriately coach and give advic

to their followers and help them to achieve self-actualization. These leaders delegate to as

followers in developing through work-related challenges and care for employees in a way

appropriate for each employee. If employees need nurturance, the leader will nurture;if

employees need task structure, the leader will provide structure (Northouse, 2010).

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Chapter 9: TransformationalLeadership 261

Transformationalleadership achieves differentand more positive outcomes than

transactionalleadership. The latter achieves expected results while the former achieves

much more than expected. The reason is that under transformational leaders, followers

are inspired to work for the good of the organization and subordinate their own self-

interests to those of the organization.

Transactional Leadership Factors

As suggested above, transactional leadership is different from transformational leadershi

in expected outcomes. The reason is that under transactional leaders, there is no individ-

ualization offollowers’needs and no emphasis on followers’personaldevelopment—

these leaders treat their followers as members of a homogeneous group.These leaders

develop a relationship with their followers based on the exchange of something valuable

to followers for the achievement of the leader’s goals and the goals of the followers. Thes

leaders are influential because their subordinates’ interests are connected to the interest

of each leader (Kuhnert, 1994; Kuhnert & Lewis, 1987).

ContingentReward.This factordescribesa processwhereby leadersand followers

exchange effort by followers for specific rewards from leaders. This process implies agree

ment between leaders and followers on what needs to be accomplished and what each

person in the process will receive. This agreement is usually done prior to the exchange o

effort and reward.

Management by Exception (MBE). This factor has two forms—active and passive. The for-

mer involves corrective criticism, while the latter involves negative feedback and negativ

reinforcement. Leaders who use MBE (active) closely monitor their subordinates to see if

they are violating the rules or making mistakes. When rules are violated and/or mistakes

made, these leaders take corrective action by discussing with their subordinates what the

did wrong and how to do things right. Contrary to the MBE (active) way of leading, lead-

ers who use MBE (passive) do not closely monitor subordinates but wait untilproblems

occur and/or standards are violated. Based on their poor performance, these leaders give

subordinates low evaluations without discussing their performance and how to improve.

Both forms of MBE use a reinforcement pattern that is more negative than the more pos-

itive pattern used by leaders using contingent reward.

The Nonleadership Factor

As leaders move further from transformational leadership through transactional leader-

ship, they come to laissez-faire leadership. Individuals in leadership positions who exer-

cise this type ofleadership actually abdicate their leadership responsibilities.This is

absentee leadership (Northouse,2010).These leaders try to not make decisions or to

delay making decisions longer than they should, provide subordinates with little or no

performance feedback, and ignore the needs of subordinates. These leaders have a “wha

will be will be” or “hands-off, let-things-ride” approach with no effort to even exchange

rewards for effort by subordinates. Leaders who do not communicate with their subordi-

nates or have any plans for their organization exemplify this type of leadership.

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

Transformationalleadership achieves differentand more positive outcomes than

transactionalleadership. The latter achieves expected results while the former achieves

much more than expected. The reason is that under transformational leaders, followers

are inspired to work for the good of the organization and subordinate their own self-

interests to those of the organization.

Transactional Leadership Factors

As suggested above, transactional leadership is different from transformational leadershi

in expected outcomes. The reason is that under transactional leaders, there is no individ-

ualization offollowers’needs and no emphasis on followers’personaldevelopment—

these leaders treat their followers as members of a homogeneous group.These leaders

develop a relationship with their followers based on the exchange of something valuable

to followers for the achievement of the leader’s goals and the goals of the followers. Thes

leaders are influential because their subordinates’ interests are connected to the interest

of each leader (Kuhnert, 1994; Kuhnert & Lewis, 1987).

ContingentReward.This factordescribesa processwhereby leadersand followers

exchange effort by followers for specific rewards from leaders. This process implies agree

ment between leaders and followers on what needs to be accomplished and what each

person in the process will receive. This agreement is usually done prior to the exchange o

effort and reward.

Management by Exception (MBE). This factor has two forms—active and passive. The for-

mer involves corrective criticism, while the latter involves negative feedback and negativ

reinforcement. Leaders who use MBE (active) closely monitor their subordinates to see if

they are violating the rules or making mistakes. When rules are violated and/or mistakes

made, these leaders take corrective action by discussing with their subordinates what the

did wrong and how to do things right. Contrary to the MBE (active) way of leading, lead-

ers who use MBE (passive) do not closely monitor subordinates but wait untilproblems

occur and/or standards are violated. Based on their poor performance, these leaders give

subordinates low evaluations without discussing their performance and how to improve.

Both forms of MBE use a reinforcement pattern that is more negative than the more pos-

itive pattern used by leaders using contingent reward.

The Nonleadership Factor

As leaders move further from transformational leadership through transactional leader-

ship, they come to laissez-faire leadership. Individuals in leadership positions who exer-

cise this type ofleadership actually abdicate their leadership responsibilities.This is

absentee leadership (Northouse,2010).These leaders try to not make decisions or to

delay making decisions longer than they should, provide subordinates with little or no

performance feedback, and ignore the needs of subordinates. These leaders have a “wha

will be will be” or “hands-off, let-things-ride” approach with no effort to even exchange

rewards for effort by subordinates. Leaders who do not communicate with their subordi-

nates or have any plans for their organization exemplify this type of leadership.

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Other Perspectives of Transformational Leadership

Two other streams ofresearch contribute to our comprehension oftransformational

leadership:These streamsare research conducted by Bennisand Nanus(1985) and

Kouzes and Posner (1987,2002).Bennis and Nanus interviewed 90 leaders and,from

these leaders’ answers to several questions, developed strategies that enable organization

to be transformed. Kouzes and Posner interviewed 1,300 middle- to senior-level leaders

in private and public organizations. They asked each leader to tell about his or her “per-

sonalbest” leader experiences.From the answers these leaders provided,Kouzes and

Posner developed their version of a transformational leadership model.

The Bennis and Nanus (1985) Transformational Leadership Model

Bennis and Nanus (1985) asked questions such as the following: “What are your strengths

and weaknesses? What past events most influenced your leadership approach? What were

the critical points in your career?” (Northouse, 2010). The answers to these questions pro-

vided four strategies that transcend leaders or organizations in their usefulness for trans-

forming organizations.

First, leaders need to have a clear, compelling, believable, and attractive vision of their

organization’s future. Second, they need to be social architects who shape the shared mea

ings maintained by individuals in organizations. These leaders set a direction that allows

subordinates to follow new organizational values and share a new organizational identity.

Third, leaders need to develop within followers a trust based on setting and consistently

implementing a direction,even though there may be a high degree ofuncertainty sur-

rounding the vision. Fourth, leaders need to use creative deployment of self through positi

self-regard. This means that leaders know their strengths and weaknesses and focus on th

strengths, not their weaknesses. This creates feelings of confidence and positive expectati

in their followers and builds a learning philosophy throughout their organizations.

The Kouzes and Posner (1987, 2002) Transformational Leadership Model

On the basis of their interviews with middle- to senior-level managers, Kouzes and Posner

(1987, 2002) found five strategies through content analyzing the answers to their “per-

sonal best” leadership experiences questions.

First, leaders need to model the way by knowing their own voice and expressing it to

their followers, peers, and superiors through verbal communication and their own behav-

iors. Second, leaders need to develop and inspire a shared vision that compels individuals

to act or behave in accordance with the vision. These inspired and shared visions chal-

lenge followers, peers, and others to achieve something that goes beyond the status quo.

Third, leaders need to challenge the process. This means having a willingness to step out

into unfamiliar areas, to experiment, to innovate, and to take risks to improve their orga-

nizations. These leaders take risks one step at a time and learn as they make mistakes.

Fourth, leaders need to enable others to act. They collaborate and develop trust with ot

ers; they treat others with respect and dignity; they willingly listen to others’ viewpoints, e

if they are different from the norm; they support others in their decisions; they emphasize

teamwork and cooperation;and,finally,they enable others to give to their organizations

because these others feel good about their leaders, their job, their organizations, and them

Fifth, leaders need to encourage the heart.This suggests that leaders should rec-

ognize the need inherent in people for support and recognition. This means praising

262 CASES IN LEADERSHIP

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

Two other streams ofresearch contribute to our comprehension oftransformational

leadership:These streamsare research conducted by Bennisand Nanus(1985) and

Kouzes and Posner (1987,2002).Bennis and Nanus interviewed 90 leaders and,from

these leaders’ answers to several questions, developed strategies that enable organization

to be transformed. Kouzes and Posner interviewed 1,300 middle- to senior-level leaders

in private and public organizations. They asked each leader to tell about his or her “per-

sonalbest” leader experiences.From the answers these leaders provided,Kouzes and

Posner developed their version of a transformational leadership model.

The Bennis and Nanus (1985) Transformational Leadership Model

Bennis and Nanus (1985) asked questions such as the following: “What are your strengths

and weaknesses? What past events most influenced your leadership approach? What were

the critical points in your career?” (Northouse, 2010). The answers to these questions pro-

vided four strategies that transcend leaders or organizations in their usefulness for trans-

forming organizations.

First, leaders need to have a clear, compelling, believable, and attractive vision of their

organization’s future. Second, they need to be social architects who shape the shared mea

ings maintained by individuals in organizations. These leaders set a direction that allows

subordinates to follow new organizational values and share a new organizational identity.

Third, leaders need to develop within followers a trust based on setting and consistently

implementing a direction,even though there may be a high degree ofuncertainty sur-

rounding the vision. Fourth, leaders need to use creative deployment of self through positi

self-regard. This means that leaders know their strengths and weaknesses and focus on th

strengths, not their weaknesses. This creates feelings of confidence and positive expectati

in their followers and builds a learning philosophy throughout their organizations.

The Kouzes and Posner (1987, 2002) Transformational Leadership Model

On the basis of their interviews with middle- to senior-level managers, Kouzes and Posner

(1987, 2002) found five strategies through content analyzing the answers to their “per-

sonal best” leadership experiences questions.

First, leaders need to model the way by knowing their own voice and expressing it to

their followers, peers, and superiors through verbal communication and their own behav-

iors. Second, leaders need to develop and inspire a shared vision that compels individuals

to act or behave in accordance with the vision. These inspired and shared visions chal-

lenge followers, peers, and others to achieve something that goes beyond the status quo.

Third, leaders need to challenge the process. This means having a willingness to step out

into unfamiliar areas, to experiment, to innovate, and to take risks to improve their orga-

nizations. These leaders take risks one step at a time and learn as they make mistakes.

Fourth, leaders need to enable others to act. They collaborate and develop trust with ot

ers; they treat others with respect and dignity; they willingly listen to others’ viewpoints, e

if they are different from the norm; they support others in their decisions; they emphasize

teamwork and cooperation;and,finally,they enable others to give to their organizations

because these others feel good about their leaders, their job, their organizations, and them

Fifth, leaders need to encourage the heart.This suggests that leaders should rec-

ognize the need inherent in people for support and recognition. This means praising

262 CASES IN LEADERSHIP

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

Chapter 9: TransformationalLeadership 263

people for work done well and celebrating to demonstrate appreciation when others

do good work.

This model focuses on leader behaviors and is prescriptive. It describes what needs to

done to effectively lead others to embrace and willingly support organizational transform

The model is not about people with special abilities. Kouzes and Posner (1987, 2002) arg

these five principles are available to all who willingly practice them as they lead others.

How Does the Transformational Leadership Approach Work?

This approach to leadership is a broad-based perspective that describes what leaders nee

to do to formulate and implement major organizational change (Daft, 2005). These trans-

formational leaders pursue some or most of the following steps.

First, they develop an organizational culture open to change by empowering subordin

to change, encouraging transparency in conversations related to change, and supporting

in trying innovative and different ways of achieving organizational goals. Second, they pr

a strong example of moral values and ethical behavior that followers want to imitate bec

they have developed a trust and belief in these leaders and what they stand for.

Third, they help a vision to emerge that sets a direction for the organization. This visio

transcends the various interests of individuals and different groups within the organizatio

while clearly determining the organization’s identity. Fourth, they become social architec

clarify the beliefs, values, and norms that are required to accomplish organizational chan

Finally, they encourage people to work together, to build trust in their leaders and each o

and to rejoice when others accomplish goals related to the vision for change (Northouse,

yy References

Avolio, B. J. (1999). Leadership in organizations (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press.

Bass, B. M. (1990). From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vis

Organizational Dynamics, 18, 19–31.

Bass, B. M. (1998). The ethics of transformational leadership. In J. Ciulla (Ed.), Ethics: The heart of lead-

ership (pp. 169–192). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1990). The implications of transactional and transformational leadership for

individual,team,and organizationaldevelopment.Researchin OrganizationalChangeand

Development, 4, 231–272.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership: A response to critiques. In M.

Chemers & R. Ayman (Eds.), Leadership theory and research: Perspectives and directions (pp. 49–80

San Diego: Academic Press.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational lead

ship. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbau

Bass, B. M., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadersh

Leadership Quarterly, 10, 81–227.

Bennis, W. G., & Nanus, B. (1985). Leaders: The strategies for taking charge. New York: Harper & Row.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Row.

Bryman, A. (1992). Charisma and leadership in organizations. London: Sage.

Daft, R. L. (2005). The leadership experience (3rd ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson, South-Western.

Downton, J. V. (1973). Rebel leadership: Commitment and charisma in a revolutionary process. New Yo

Free Press.

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

people for work done well and celebrating to demonstrate appreciation when others

do good work.

This model focuses on leader behaviors and is prescriptive. It describes what needs to

done to effectively lead others to embrace and willingly support organizational transform

The model is not about people with special abilities. Kouzes and Posner (1987, 2002) arg

these five principles are available to all who willingly practice them as they lead others.

How Does the Transformational Leadership Approach Work?

This approach to leadership is a broad-based perspective that describes what leaders nee

to do to formulate and implement major organizational change (Daft, 2005). These trans-

formational leaders pursue some or most of the following steps.

First, they develop an organizational culture open to change by empowering subordin

to change, encouraging transparency in conversations related to change, and supporting

in trying innovative and different ways of achieving organizational goals. Second, they pr

a strong example of moral values and ethical behavior that followers want to imitate bec

they have developed a trust and belief in these leaders and what they stand for.

Third, they help a vision to emerge that sets a direction for the organization. This visio

transcends the various interests of individuals and different groups within the organizatio

while clearly determining the organization’s identity. Fourth, they become social architec

clarify the beliefs, values, and norms that are required to accomplish organizational chan

Finally, they encourage people to work together, to build trust in their leaders and each o

and to rejoice when others accomplish goals related to the vision for change (Northouse,

yy References

Avolio, B. J. (1999). Leadership in organizations (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press.

Bass, B. M. (1990). From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vis

Organizational Dynamics, 18, 19–31.

Bass, B. M. (1998). The ethics of transformational leadership. In J. Ciulla (Ed.), Ethics: The heart of lead-

ership (pp. 169–192). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1990). The implications of transactional and transformational leadership for

individual,team,and organizationaldevelopment.Researchin OrganizationalChangeand

Development, 4, 231–272.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership: A response to critiques. In M.

Chemers & R. Ayman (Eds.), Leadership theory and research: Perspectives and directions (pp. 49–80

San Diego: Academic Press.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational lead

ship. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbau

Bass, B. M., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadersh

Leadership Quarterly, 10, 81–227.

Bennis, W. G., & Nanus, B. (1985). Leaders: The strategies for taking charge. New York: Harper & Row.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Row.

Bryman, A. (1992). Charisma and leadership in organizations. London: Sage.

Daft, R. L. (2005). The leadership experience (3rd ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson, South-Western.

Downton, J. V. (1973). Rebel leadership: Commitment and charisma in a revolutionary process. New Yo

Free Press.

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Dubrin, A. (2007). Leadership: Research findings, practice, and skills. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Goldsmith, M., Greenberg, C. L., Robertson, A., & Hu-Chan, M. (2003). Global leadership: The next gen-

eration. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times Prentice Hall.

House, R. J. (1976). A 1976 theory of charismatic leadership. In J. G. Hunt & L. L. Larson (Eds.)

Leadership: The cutting edge (pp. 189–207). Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Howell, J. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1992). The ethics of charismatic leadership: Submission or liberation

Academy of Management Executive, 6(2), 43–54.

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (1987). The leadership challenge: How to get extraordinary things done in

organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2002). The leadership challenge (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kuhnert, K. W. (1994). Transforming leadership: Developing people through delegation. In B. M. Bass &

B. J. Avolio (Eds.), Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership (pp. 10–

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kuhnert, K. W., & Lewis, P. (1987). Transactional and transformational leadership: A constructive/

developmental analysis. Academy of Management Review, 12(4), 648–657.

Northouse, P. G. (2010). Leadership: Theory and practice (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Shamir, B., House, R. J., & Arthur, M. B. (1993). The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: A

self-concept-based theory. Organization Science, 4(4), 577–594.

Weber, M. (1947). The theory of social and economic organizations (T. Parsons, Trans.). New York: Free P

Yukl, G. (2006). Leadership in organizations (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

yy The Cases

Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, Knight of the British Empire

Rudolph Giuliani was the mayor of New York City during the events of September 11,

2001, and became world renowned for his leadership. Outlined is a description of h

background, his first few years in office, the troubles he faced in his last year in office, and

the sudden shift in his popularity post–September 11, 2001.

Spar Applied Systems: Anna’s Challenge

The director of human resources must contend with internal and external pressures to

make changes quickly and smoothly for the new year. She has been with the company for

6 months. In her capacity as director of human resources, she has spent her time estab-

lishing a baseline for the division so that she can then create a departmental vision and

strategy for 2000. It will be one of the most interesting challenges of her career. Since join

ing, she has gained an understanding of the division’s future direction from its leadership

team. The team is under the direction of the division’s new general manager.

yy The Reading

Drucker’s Challenge: Communication

and the Emotional Glass Ceiling

The supreme challenge for a leader is to change human behavior, a formidable, if not impo

sible, task. But the leader who is emotionally intelligent (who is aware of and comfortable w

264 CASES IN LEADERSHIP

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

Goldsmith, M., Greenberg, C. L., Robertson, A., & Hu-Chan, M. (2003). Global leadership: The next gen-

eration. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times Prentice Hall.

House, R. J. (1976). A 1976 theory of charismatic leadership. In J. G. Hunt & L. L. Larson (Eds.)

Leadership: The cutting edge (pp. 189–207). Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Howell, J. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1992). The ethics of charismatic leadership: Submission or liberation

Academy of Management Executive, 6(2), 43–54.

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (1987). The leadership challenge: How to get extraordinary things done in

organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2002). The leadership challenge (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kuhnert, K. W. (1994). Transforming leadership: Developing people through delegation. In B. M. Bass &

B. J. Avolio (Eds.), Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership (pp. 10–

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kuhnert, K. W., & Lewis, P. (1987). Transactional and transformational leadership: A constructive/

developmental analysis. Academy of Management Review, 12(4), 648–657.

Northouse, P. G. (2010). Leadership: Theory and practice (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Shamir, B., House, R. J., & Arthur, M. B. (1993). The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: A

self-concept-based theory. Organization Science, 4(4), 577–594.

Weber, M. (1947). The theory of social and economic organizations (T. Parsons, Trans.). New York: Free P

Yukl, G. (2006). Leadership in organizations (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

yy The Cases

Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, Knight of the British Empire

Rudolph Giuliani was the mayor of New York City during the events of September 11,

2001, and became world renowned for his leadership. Outlined is a description of h

background, his first few years in office, the troubles he faced in his last year in office, and

the sudden shift in his popularity post–September 11, 2001.

Spar Applied Systems: Anna’s Challenge

The director of human resources must contend with internal and external pressures to

make changes quickly and smoothly for the new year. She has been with the company for

6 months. In her capacity as director of human resources, she has spent her time estab-

lishing a baseline for the division so that she can then create a departmental vision and

strategy for 2000. It will be one of the most interesting challenges of her career. Since join

ing, she has gained an understanding of the division’s future direction from its leadership

team. The team is under the direction of the division’s new general manager.

yy The Reading

Drucker’s Challenge: Communication

and the Emotional Glass Ceiling

The supreme challenge for a leader is to change human behavior, a formidable, if not impo

sible, task. But the leader who is emotionally intelligent (who is aware of and comfortable w

264 CASES IN LEADERSHIP

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, Knight of the British Empire265

his or her own self) will have a far greater chance of changing the behavior of others than

leader who is not aware of himself or herself. Using theories from esteemed managemen

thinker Peter Drucker, the author points out that leaders who inspire are those who have

resolved their own identity crisis. But that is much easier said than done, and the dauntin

nature of the task is encapsulated in Drucker’s Challenge, which states that every human

being has an emotional glass ceiling, a natural “resistance to changing” identity. This cei

is broken only when communication is so compelling that it overcomes that resistance. H

leaders can accomplish this goal is the subject of this article.

Mayor Rudolph Giuliani,

Knight of the British Empire

Prepared by Ken Mark under the supervision

of Christina A. Cavanagh

yy Introduction

Rudolph Giuliani, the mayor of New York City,

was going to receive a honorary knighthood

from Britain, announced the National Post on

October 15, 2001. The award, reported in the

British press on Saturday and confirmed by

official sources on October 14, 2001, followed

Giuliani’swidelypraisedleadershipin the

wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks on

New York that killed thousands of people and

destroyed the twin towers of the World Trade

Center.The award, “Knightof the British

Empire,” was the highest honor the Queen

could bestow on a foreign citizen.

Britain’s SundayTelegraphnewspaper

quoted a Buckingham Palace official saying:

The Queen believesthat Rudolph

Giuliani was an inspiration to political

leaders around the world, as well as to his

city. She was grateful for his support for

Britons bereaved by the tragedy and feels

that this will also be a gesture of solidar-

ity between America and Britain. Her

regard for Mayor Giuliani is reflected in

her desire to present the honour in per-

son at Buckingham Palace.

yy Rudy Giuliani,

Mayor of New York City

Giuliani had spent his adult life searching for

missions impossible enough to suit his extrav-

agant sense of self. A child of Brooklyn who

was raised in a family of fire fighters, cops and

criminals, he chose the path of righteousness

and turned his life into a war against evil as he

defined it. As a U.S. attorney in New York dur-

ing the 1980s, Giuliani was perhaps the most

effective prosecutor in the country, locking up

Mafia bosses,crookedpoliticiansand Wall

Street inside traders.

When Giuliani was electedmayor of

New York City in 1993, more than a million

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This case has been written on the basis of published sources only. Consequently, the interpretatio

spectives presented in this case are not necessarily those of Rudolph Giuliani or any of his employees.

Copyright 2003, Ivey Management Services Version: (A) 2003-02-12

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

his or her own self) will have a far greater chance of changing the behavior of others than

leader who is not aware of himself or herself. Using theories from esteemed managemen

thinker Peter Drucker, the author points out that leaders who inspire are those who have

resolved their own identity crisis. But that is much easier said than done, and the dauntin

nature of the task is encapsulated in Drucker’s Challenge, which states that every human

being has an emotional glass ceiling, a natural “resistance to changing” identity. This cei

is broken only when communication is so compelling that it overcomes that resistance. H

leaders can accomplish this goal is the subject of this article.

Mayor Rudolph Giuliani,

Knight of the British Empire

Prepared by Ken Mark under the supervision

of Christina A. Cavanagh

yy Introduction

Rudolph Giuliani, the mayor of New York City,

was going to receive a honorary knighthood

from Britain, announced the National Post on

October 15, 2001. The award, reported in the

British press on Saturday and confirmed by

official sources on October 14, 2001, followed

Giuliani’swidelypraisedleadershipin the

wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks on

New York that killed thousands of people and

destroyed the twin towers of the World Trade

Center.The award, “Knightof the British

Empire,” was the highest honor the Queen

could bestow on a foreign citizen.

Britain’s SundayTelegraphnewspaper

quoted a Buckingham Palace official saying:

The Queen believesthat Rudolph

Giuliani was an inspiration to political

leaders around the world, as well as to his

city. She was grateful for his support for

Britons bereaved by the tragedy and feels

that this will also be a gesture of solidar-

ity between America and Britain. Her

regard for Mayor Giuliani is reflected in

her desire to present the honour in per-

son at Buckingham Palace.

yy Rudy Giuliani,

Mayor of New York City

Giuliani had spent his adult life searching for

missions impossible enough to suit his extrav-

agant sense of self. A child of Brooklyn who

was raised in a family of fire fighters, cops and

criminals, he chose the path of righteousness

and turned his life into a war against evil as he

defined it. As a U.S. attorney in New York dur-

ing the 1980s, Giuliani was perhaps the most

effective prosecutor in the country, locking up

Mafia bosses,crookedpoliticiansand Wall

Street inside traders.

When Giuliani was electedmayor of

New York City in 1993, more than a million

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This case has been written on the basis of published sources only. Consequently, the interpretatio

spectives presented in this case are not necessarily those of Rudolph Giuliani or any of his employees.

Copyright 2003, Ivey Management Services Version: (A) 2003-02-12

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

266 CHAPTER 9: TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP

New Yorkers were on welfare, violent crime

and crack cocaine had ravaged whole neigh-

borhoods, and taxes and unemployment were

sky-high.It was fashionableto dismissthe

place as ungovernable. Mayor Giuliani made

good on his promise, doing away with New

York’s traditional politics of soft and ineffec-

tual symbolism. The public was shocked and

delighted to find that the streets were safer and

cleaner. And the public did not care how he did

it. If Giuliani picked fights big and small, if he

purged government of those he deemed insuf-

ficiently loyal, so be it, “People didn’t elect me

to be a conciliator,” Giuliani said.

He governed by hammering everyone else

into submission, but in areas where that strat-

egy was ineffective, such as the reform of the

city schools, he failed to make improvements.

Although by 1997 he had cut crime by two-

thirds, his job-approval rating had declined to

32 per cent. New York City was getting better,

but the mayor seemed to be getting worse.

Black minority leaders complained that his

aggressive cops were practising racial profil-

ing, stopping and frisking people because of

their race. Giuliani launchedcampaigns

against jaywalkers, street vendors, noisy car

alarms, and a crusade against publicly funded

art that offended his moral sensibilities. But

the pose seemed hypocritical at best when

Giuliani, whose wife had not been seen at

City Hall in years, began courting another

woman, Judi Nathan.

In typicalNew Yorkfashion,he was a

dichotomous mix of public sentiment and dis-

dain. Time magazinereported,on May 28,

2001, that Giuliani was poised to leave his office

on a wave of goodwill, with opportunities for

future office. Despite announcing the end of

his marriage to the press corps before he told

his wife, he had garnered a level of public sym-

pathy not usually availableto adulterers,

thought to be due to his unfortunate bout of

prostatecanceroverridingthe simultaneous

appearance of his new girlfriend.

As a public figure, his life was more than

just an open book. It was a constant and daily

analysis of every aspect of his colorful life.

Perhaps not since the Princess of Wales had a

public figure become so newsworthy even if

only on a local scale. There were hundreds of

stories written about him and just as many

colorful headlines announcing the firing of

his estranged wife’s staff and rumors of him

leaving the New York City mayor’s mansion

due to the ongoing divorce drama.

yy The Transformation Begins

Through circumstances both inexplicable and

extraordinary, a controversial mayor who was

set to leave office in 2002 took the reigns of a

crisis on what became known as the twenty-

first century’s “Day of Infamy”—September

11, 2001. Countless newspapers published sto-

ries of Giuliani mobilizing the city’s emer-

gency services, running through smoke-filled

basements wearing a gas mask and urging sur-

vivors to head north. As Newsweek reported,

September 24, 2001:

Giuliani, wearing a gas mask, was led

running through a smoke-filled base-

ment maze and out the other side of

the Merrill Lynch building on Barclay

Street, where the soot they’re now call-

ing “graysnow”was a foot deep.

Stripping off the gas mask, Giuliani

and a small group set off on foot for a

mile hike up Church Street, urging the

ghostly,ash-cakedsurvivorsto “Go

north! Go north!” A distraught African

Americanwomanapproached,and

the mayor touched her face, telling her

“It’s going to be OK.” Farther up, a

young rowdy got the mayoral

“Shhhhhh!” he deserved. That set the

tone. He was sensitive and tough and

totally on top of everything. Even his

press criticism was, for once, on target.

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

New Yorkers were on welfare, violent crime

and crack cocaine had ravaged whole neigh-

borhoods, and taxes and unemployment were

sky-high.It was fashionableto dismissthe

place as ungovernable. Mayor Giuliani made

good on his promise, doing away with New

York’s traditional politics of soft and ineffec-

tual symbolism. The public was shocked and

delighted to find that the streets were safer and

cleaner. And the public did not care how he did

it. If Giuliani picked fights big and small, if he

purged government of those he deemed insuf-

ficiently loyal, so be it, “People didn’t elect me

to be a conciliator,” Giuliani said.

He governed by hammering everyone else

into submission, but in areas where that strat-

egy was ineffective, such as the reform of the

city schools, he failed to make improvements.

Although by 1997 he had cut crime by two-

thirds, his job-approval rating had declined to

32 per cent. New York City was getting better,

but the mayor seemed to be getting worse.

Black minority leaders complained that his

aggressive cops were practising racial profil-

ing, stopping and frisking people because of

their race. Giuliani launchedcampaigns

against jaywalkers, street vendors, noisy car

alarms, and a crusade against publicly funded

art that offended his moral sensibilities. But

the pose seemed hypocritical at best when

Giuliani, whose wife had not been seen at

City Hall in years, began courting another

woman, Judi Nathan.

In typicalNew Yorkfashion,he was a

dichotomous mix of public sentiment and dis-

dain. Time magazinereported,on May 28,

2001, that Giuliani was poised to leave his office

on a wave of goodwill, with opportunities for

future office. Despite announcing the end of

his marriage to the press corps before he told

his wife, he had garnered a level of public sym-

pathy not usually availableto adulterers,

thought to be due to his unfortunate bout of

prostatecanceroverridingthe simultaneous

appearance of his new girlfriend.

As a public figure, his life was more than

just an open book. It was a constant and daily

analysis of every aspect of his colorful life.

Perhaps not since the Princess of Wales had a

public figure become so newsworthy even if

only on a local scale. There were hundreds of

stories written about him and just as many

colorful headlines announcing the firing of

his estranged wife’s staff and rumors of him

leaving the New York City mayor’s mansion

due to the ongoing divorce drama.

yy The Transformation Begins

Through circumstances both inexplicable and

extraordinary, a controversial mayor who was

set to leave office in 2002 took the reigns of a

crisis on what became known as the twenty-

first century’s “Day of Infamy”—September

11, 2001. Countless newspapers published sto-

ries of Giuliani mobilizing the city’s emer-

gency services, running through smoke-filled

basements wearing a gas mask and urging sur-

vivors to head north. As Newsweek reported,

September 24, 2001:

Giuliani, wearing a gas mask, was led

running through a smoke-filled base-

ment maze and out the other side of

the Merrill Lynch building on Barclay

Street, where the soot they’re now call-

ing “graysnow”was a foot deep.

Stripping off the gas mask, Giuliani

and a small group set off on foot for a

mile hike up Church Street, urging the

ghostly,ash-cakedsurvivorsto “Go

north! Go north!” A distraught African

Americanwomanapproached,and

the mayor touched her face, telling her

“It’s going to be OK.” Farther up, a

young rowdy got the mayoral

“Shhhhhh!” he deserved. That set the

tone. He was sensitive and tough and

totally on top of everything. Even his

press criticism was, for once, on target.

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, Knight of the British Empire267

And even his harshest critics offered noth-

ing but sincere praise.

In recent years, Rudy Giuliani has been

a crankyand not terriblyeffective

mayor, too distracted by marital and

health problems to work on the city’s

surging murder rate. But in this cata-

clysm, which he rightly called “the most

difficult week in the history of New

York,” the city and the country have

found that the most elusive of all demo-

cratic treasures—real leadership.1

A Barron’s report, on September 24, 2001,

was even more on point:

It is no secret that disaster has yielded a

remarkable change in the public per-

sona of Rudy Giuliani. Vanished is the

meanmayorwho badgeredhot-dog

vendors, threatened museums, sought

to bludgeon dissent and indulged in an

open and nasty row with his estranged

wife. And in his place is, well, the essen-

tial Rudy: generous,sympathetic,

indefatigable,levelheaded,unfailingly

reassuring, a man for all crises.

The real Rudy, in other words. We say

that becausewe’veknownRudy for

something close to a quarter of a cen-

tury; indeed, for a spell between govern-

ment jobs he represented Dow Jones, the

parent company of Barron’s, and, we can

personally attest, was one hell of a lawyer.

More to the point, he was also that rare

combination of tough when he had to

be and tender when he should have

been, funny, bright and argumentative

(natch), a great guy to knock off a bottle

or two of vino with. Rudy has done a lot

of silly things as mayor, but it doesn’t

surpriseus one whit that whenthe

unimaginable happened, he did every-

thing right and with incomparable style.2

As his popularity soared, Giuliani played

with thoughts of returning to serve a third

term. Time magazine reported on October 8,

2001 that Giuliani had received 15 per cent of

the primary vote, all from write-in ballots. This

result underlinedGiuliani’s undiminished

popularity in the eyes of the public:

On a typical day last week, he found sim-

ple words to console the two children of

Inspector Anthony Infante at St. Theresa’s

in the morning, then managed the ego of

the Rev. Jesse Jackson as he took advan-

tage of Giuliani’s media entourage to

nominate himself negotiator-in-chief. In

the evening, Giuliani called on a stricken

crowd at Temple Emanu-El to stand and

applaud Neil Levin, the head of the Port

Authority, who died helping his employ-

ees escape. Reverting to tireless cheer-

leader,he endedhis day at Yankee

Stadium watching Roger Clemens pitch

against Tampa Bay.3

Bolstered by this show of support from the

public, Giuliani summoned the three leading

mayoral candidates to his office at Pier 92 and

demanded to be allowed to stay in office for

another three months—or else he would enter

the mayoral race against them and win. Al

Sharpton, a supporter for Fernando Ferrer in

the 2002 New York mayoralelectionwas

unimpressedwith this move.Unmovedby

Giuliani’s achievements, he referred to reports

of Giuliani’s heroics on September 11, 2001,

arguing that on that day, “We would have come

together (as a city) if Bozo was the mayor.”

1Jonathan Alter, “Grit, Guts and Rudy Giuliani”, Newsweek, September 24, 2001.

2Alan Abelson, “Up & Down Wall Street: Weighing Consequences”, Barron’s, September 24, 2001.

3Margaret Carlson, “Patriotic Splurging”, Time, October 15, 2001.

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

And even his harshest critics offered noth-

ing but sincere praise.

In recent years, Rudy Giuliani has been

a crankyand not terriblyeffective

mayor, too distracted by marital and

health problems to work on the city’s

surging murder rate. But in this cata-

clysm, which he rightly called “the most

difficult week in the history of New

York,” the city and the country have

found that the most elusive of all demo-

cratic treasures—real leadership.1

A Barron’s report, on September 24, 2001,

was even more on point:

It is no secret that disaster has yielded a

remarkable change in the public per-

sona of Rudy Giuliani. Vanished is the

meanmayorwho badgeredhot-dog

vendors, threatened museums, sought

to bludgeon dissent and indulged in an

open and nasty row with his estranged

wife. And in his place is, well, the essen-

tial Rudy: generous,sympathetic,

indefatigable,levelheaded,unfailingly

reassuring, a man for all crises.

The real Rudy, in other words. We say

that becausewe’veknownRudy for

something close to a quarter of a cen-

tury; indeed, for a spell between govern-

ment jobs he represented Dow Jones, the

parent company of Barron’s, and, we can

personally attest, was one hell of a lawyer.

More to the point, he was also that rare

combination of tough when he had to

be and tender when he should have

been, funny, bright and argumentative

(natch), a great guy to knock off a bottle

or two of vino with. Rudy has done a lot

of silly things as mayor, but it doesn’t

surpriseus one whit that whenthe

unimaginable happened, he did every-

thing right and with incomparable style.2

As his popularity soared, Giuliani played

with thoughts of returning to serve a third

term. Time magazine reported on October 8,

2001 that Giuliani had received 15 per cent of

the primary vote, all from write-in ballots. This

result underlinedGiuliani’s undiminished

popularity in the eyes of the public:

On a typical day last week, he found sim-

ple words to console the two children of

Inspector Anthony Infante at St. Theresa’s

in the morning, then managed the ego of

the Rev. Jesse Jackson as he took advan-

tage of Giuliani’s media entourage to

nominate himself negotiator-in-chief. In

the evening, Giuliani called on a stricken

crowd at Temple Emanu-El to stand and

applaud Neil Levin, the head of the Port

Authority, who died helping his employ-

ees escape. Reverting to tireless cheer-

leader,he endedhis day at Yankee

Stadium watching Roger Clemens pitch

against Tampa Bay.3

Bolstered by this show of support from the

public, Giuliani summoned the three leading

mayoral candidates to his office at Pier 92 and

demanded to be allowed to stay in office for

another three months—or else he would enter

the mayoral race against them and win. Al

Sharpton, a supporter for Fernando Ferrer in

the 2002 New York mayoralelectionwas

unimpressedwith this move.Unmovedby

Giuliani’s achievements, he referred to reports

of Giuliani’s heroics on September 11, 2001,

arguing that on that day, “We would have come

together (as a city) if Bozo was the mayor.”

1Jonathan Alter, “Grit, Guts and Rudy Giuliani”, Newsweek, September 24, 2001.

2Alan Abelson, “Up & Down Wall Street: Weighing Consequences”, Barron’s, September 24, 2001.

3Margaret Carlson, “Patriotic Splurging”, Time, October 15, 2001.

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

It was September 1993 and Anna Solari had

been with Spar Applied Systems for six months.

In her capacity as director of human resources,

she had spent her time establishing a baseline

for the division so that she could then create a

departmental vision and strategy for 2000. It

would be one of the most interesting challenges

of her career. Since joining, Anna had gained an

understanding of the division’s future direction

from its leadership team. The team was under

the direction of Stephen Miller, the division’s

new general manager. Since there was internal

and externalpressureto makethe changes

quickly and smoothly, Anna knew the vision

for human resources had to be in place well

before the new year.

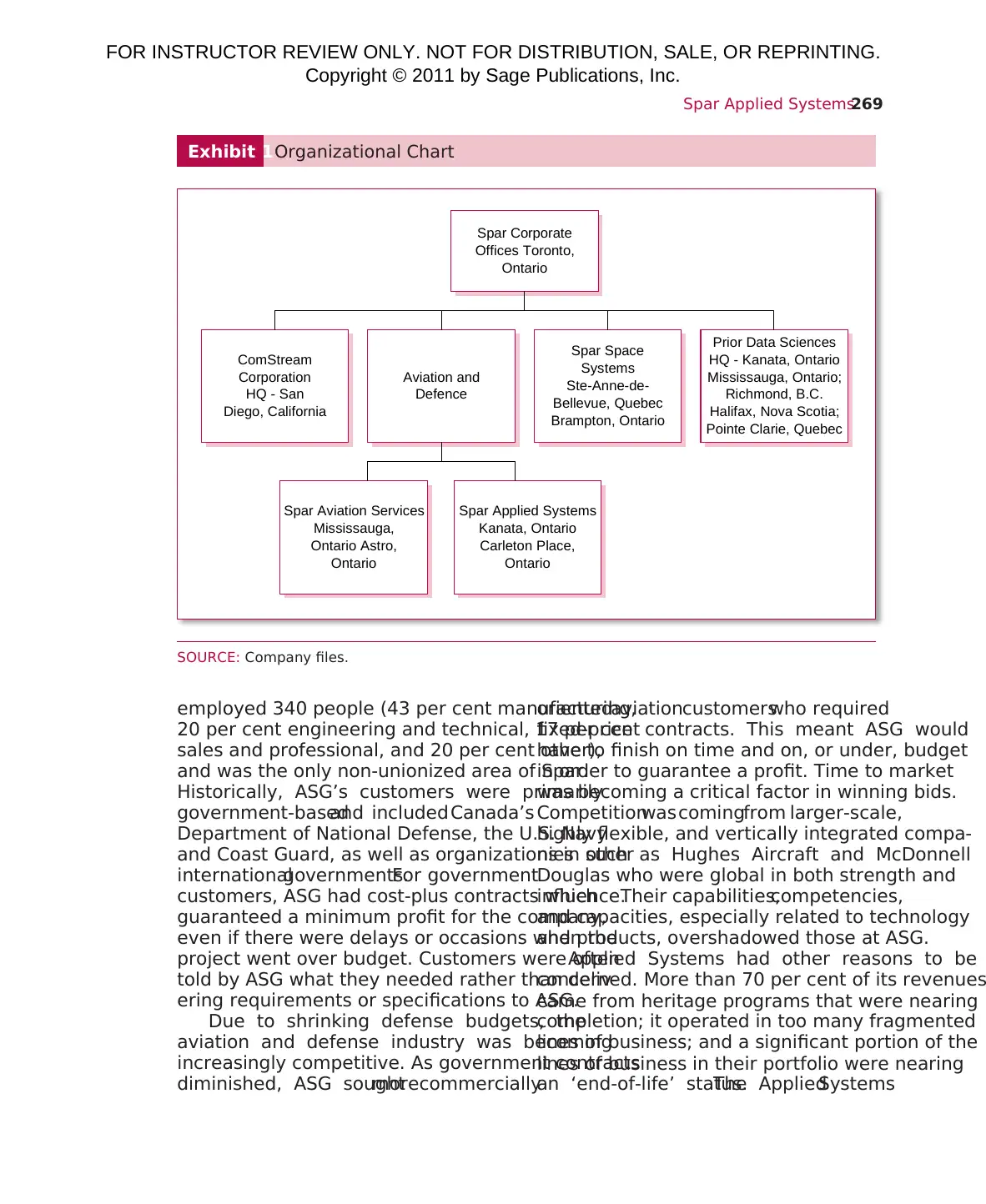

yy Spar Aerospace Limited

Spar Aerospace Limited was Canada’s premier

space company and was a recognized leader in

the space-basedcommunications,robotics,

informatics, aviation and defense industries.

The company began in 1968 as a spin-off from

de Havilland Aircraft, and was re-organized

into four decentralized business segments over

a period of two decades: space, communica-

tions,aviationand defenseand informatics

(see Exhibit 1).

The companyemployedapproximately

2,500peopleworldwideand approximately

60 per cent of Spar’s sales originated outside

Canada. Spar’s expertise enabled Canada to

become the third country in outer space and

the companycontinuedto innovatewith

achievements such as communications satel-

lites, the Canadarm, and the compression of

digital communication signals.

yy Spar Applied Systems

Spar’s Aviation and Defense area featured two

distinct businesses, one of which was Applied

Systems Group (ASG). ASG was born through a

merger between Spar Defense Systems and the

newly acquired, but bankrupt, Leigh Instruments

Limited in 1990. ASG designed and supplied

communication, flight safety, surveillance and

navigationequipmentto space,military,and

aerospace organizations around the world. It also

offeredadvancedmanufacturingservicesfor

complexelectronicassembliesand systems.

These government contracts represented close to

100 per cent of ASG’s business.

The flight safety systems products included

deployable emergency locator beacons, and flight

data and cockpit voice recorders that collected,

monitored, and analyzed aircraft flight informa-

tion to assess equipment condition and improve

flight safety procedures. Communications and

intelligence products included integrated ship-

board naval communications systems, ground-

based aircraft navigation beacons, and infrared

surveillance systems. Advanced manufacturing

incorporated the assembly of high quality, low

volume, highly complex electronic assemblies

and systems to meet stringent military and space

specifications.

ASG operated out of two facilities in the

OttawaValley(Kanataand CarletonPlace),

268 CHAPTER 9: TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP

Copyright 1997, Ivey Management Services Version: (A) 2001-08-10

Spar Applied Systems

Anna’s Challenge

Prepared by Laura Erksine under the supervision of Jane M. Howell

FOR INSTRUCTOR REVIEW ONLY. NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, SALE, OR REPRINTING.

Copyright © 2011 by Sage Publications, Inc.

been with Spar Applied Systems for six months.

In her capacity as director of human resources,

she had spent her time establishing a baseline

for the division so that she could then create a

departmental vision and strategy for 2000. It

would be one of the most interesting challenges

of her career. Since joining, Anna had gained an

understanding of the division’s future direction

from its leadership team. The team was under

the direction of Stephen Miller, the division’s

new general manager. Since there was internal

and externalpressureto makethe changes

quickly and smoothly, Anna knew the vision

for human resources had to be in place well

before the new year.

yy Spar Aerospace Limited

Spar Aerospace Limited was Canada’s premier

space company and was a recognized leader in

the space-basedcommunications,robotics,

informatics, aviation and defense industries.

The company began in 1968 as a spin-off from

de Havilland Aircraft, and was re-organized

into four decentralized business segments over

a period of two decades: space, communica-

tions,aviationand defenseand informatics

(see Exhibit 1).

The companyemployedapproximately

2,500peopleworldwideand approximately

60 per cent of Spar’s sales originated outside

Canada. Spar’s expertise enabled Canada to

become the third country in outer space and

the companycontinuedto innovatewith

achievements such as communications satel-

lites, the Canadarm, and the compression of

digital communication signals.

yy Spar Applied Systems

Spar’s Aviation and Defense area featured two

distinct businesses, one of which was Applied

Systems Group (ASG). ASG was born through a

merger between Spar Defense Systems and the

newly acquired, but bankrupt, Leigh Instruments

Limited in 1990. ASG designed and supplied

communication, flight safety, surveillance and

navigationequipmentto space,military,and

aerospace organizations around the world. It also