Antimicrobial Peptides: A Promising Therapy for Tuberculosis (TB)

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/30

|12

|3552

|141

Report

AI Summary

This report provides an overview of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) as a potential therapeutic strategy against Tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It highlights the issues with current TB therapies, including long treatment durations, adverse events, and the rise of drug resistance. The report details the unique structure of the bacterial cell wall and the mechanisms of action of AMPs, including membrane disruption, metabolic inhibition, and immunomodulation. It discusses both human-derived and synthetic AMPs, their sources, and their modes of action against mycobacteria. The conclusion emphasizes the potential of AMPs to overcome drug resistance and the need for low-cost synthesis methods and novel drug delivery systems to address proteolytic cleavage. The report references several studies supporting the use of AMPs in TB treatment.

Antimicrobial Peptides

1

1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Tuberculosis:

Tuberculosis (TB) is caused by disease causing pathogen called Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis generally affects lungs; however, it can also affect other parts of the body. Most

common symptoms of TB include chronic cough with blood-containing sputum, fever, night

sweats, and weight loss. TB usually spreads through air when active TB patient cough, spit,

speak, or sneeze (Venketaraman et al., 2015).

Issues with current therapy for TB:

Duration and complexity of treatment; and adverse events associated with TB treatment leads

to nonadherence to treatment. It results in the suboptimal response and emergence of

resistance. Increased incidence of multidrug-resistance and drug-resistant TB are the serious

problems associated with TB. Prophylactic treatment of latent TB with drugs like isoniazid is

associated with nonadherence to the treatment. Efforts to shorten treatment duration with

alternative drugs resulted in the severe adverse events (Mandal et al., 2014).

Bacterial unique structure:

Even though antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have low level of amino acid sequence, these are

associated with similar structural scaffolds. Hence, AMPs have potential antimicrobial action.

It is difficult for the antimicrobial agents to cross the microbial cell-wall scaffold because it is

composed of complex grid of macromolecules like peptidoglycan, arabinogalactan, and

mycolic acids (MAgP complex) (Arranz-Trullén et al., 2017).

AMPs:

AMPs are small, cationic and amphipathic peptides which make part of the innate immune

system; hence, considered as host defence peptides (HDPs). Expression of endogenous AMPs

is an effective host defence strategy of living organisms. Characteristics of AMPs like

multifunctional model of action, natural origin and effectiveness at low concentration made

them potential candidates for anti-tubercular treatment (Arranz-Trullén et al., 2017).

Mechanism of action:

AMPs exhibit its action through three different mechanisms like membrane disruption,

metabolic inhibitor and immunomodulator. AMPs exhibit its action on the bacterial

membranes. AMPs possess positive charge and these positive charges get attracted towards

the negative charges of bacterial membrane. Immune response develops following infection

2

Tuberculosis (TB) is caused by disease causing pathogen called Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis generally affects lungs; however, it can also affect other parts of the body. Most

common symptoms of TB include chronic cough with blood-containing sputum, fever, night

sweats, and weight loss. TB usually spreads through air when active TB patient cough, spit,

speak, or sneeze (Venketaraman et al., 2015).

Issues with current therapy for TB:

Duration and complexity of treatment; and adverse events associated with TB treatment leads

to nonadherence to treatment. It results in the suboptimal response and emergence of

resistance. Increased incidence of multidrug-resistance and drug-resistant TB are the serious

problems associated with TB. Prophylactic treatment of latent TB with drugs like isoniazid is

associated with nonadherence to the treatment. Efforts to shorten treatment duration with

alternative drugs resulted in the severe adverse events (Mandal et al., 2014).

Bacterial unique structure:

Even though antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have low level of amino acid sequence, these are

associated with similar structural scaffolds. Hence, AMPs have potential antimicrobial action.

It is difficult for the antimicrobial agents to cross the microbial cell-wall scaffold because it is

composed of complex grid of macromolecules like peptidoglycan, arabinogalactan, and

mycolic acids (MAgP complex) (Arranz-Trullén et al., 2017).

AMPs:

AMPs are small, cationic and amphipathic peptides which make part of the innate immune

system; hence, considered as host defence peptides (HDPs). Expression of endogenous AMPs

is an effective host defence strategy of living organisms. Characteristics of AMPs like

multifunctional model of action, natural origin and effectiveness at low concentration made

them potential candidates for anti-tubercular treatment (Arranz-Trullén et al., 2017).

Mechanism of action:

AMPs exhibit its action through three different mechanisms like membrane disruption,

metabolic inhibitor and immunomodulator. AMPs exhibit its action on the bacterial

membranes. AMPs possess positive charge and these positive charges get attracted towards

the negative charges of bacterial membrane. Immune response develops following infection

2

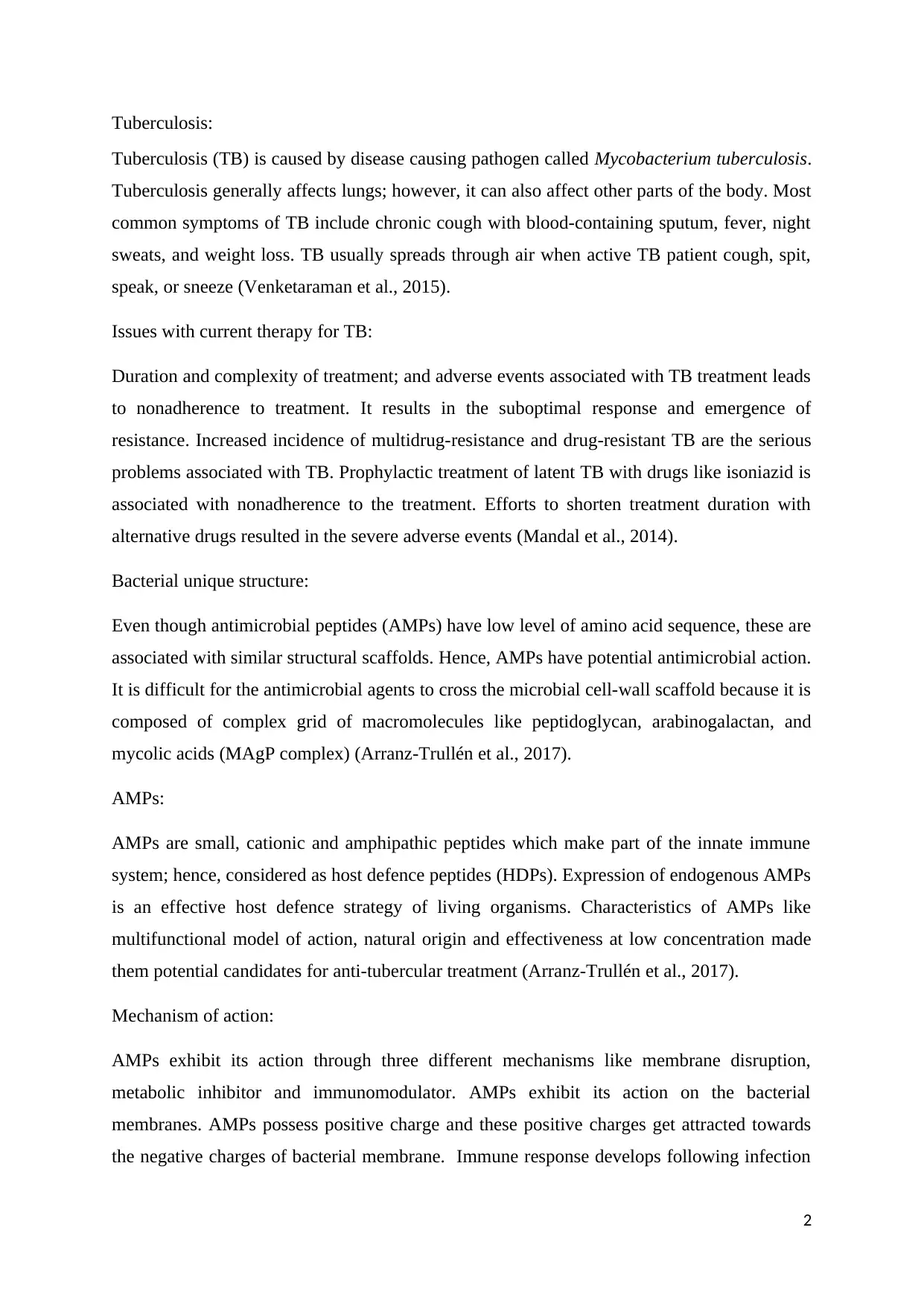

with mycobacterium. AMPs get engaged in the area of infection in the form of granuloma.

AMPs disrupt cell was and plasmatic membrane disruption which results in the membrane

pore formation. Membrane disruption mainly occur through three different mechanisms like

toroidal pore formation, carpet formation and barrel stave formation. It leads to cytoplasmic

leakage and death of bacteria. AMPs inhibit ATPase (Arranz-Trullén et al., 2017). AMP also

responsible for protein degradation by exhibiting intracellular actions like nucleic acid

binding, inhibition of replication, transcription and inhibition of translocation. Thus, AMPs

exhibits its antimicrobial activity through functioning as metabolic inhibitors. AMPs also

exhibit its action through functioning as immunomodulators. Through immunomodulation,

AMPs doesn’t inhibit bacterial growth; however, it alters immune system of host through

mechanisms like chemokine induction, histamine release, and angiogenesis modulation

(Gutsmann, 2016).

3

Figure: Mechanism of action of AMPs

1) Membrane disruption; 2) Membrane pore formation; 3) Inhibition of ATPase;

4) Action of AMPs on intracellular targets; 5 ) Protein degradation.

AMPs disrupt cell was and plasmatic membrane disruption which results in the membrane

pore formation. Membrane disruption mainly occur through three different mechanisms like

toroidal pore formation, carpet formation and barrel stave formation. It leads to cytoplasmic

leakage and death of bacteria. AMPs inhibit ATPase (Arranz-Trullén et al., 2017). AMP also

responsible for protein degradation by exhibiting intracellular actions like nucleic acid

binding, inhibition of replication, transcription and inhibition of translocation. Thus, AMPs

exhibits its antimicrobial activity through functioning as metabolic inhibitors. AMPs also

exhibit its action through functioning as immunomodulators. Through immunomodulation,

AMPs doesn’t inhibit bacterial growth; however, it alters immune system of host through

mechanisms like chemokine induction, histamine release, and angiogenesis modulation

(Gutsmann, 2016).

3

Figure: Mechanism of action of AMPs

1) Membrane disruption; 2) Membrane pore formation; 3) Inhibition of ATPase;

4) Action of AMPs on intracellular targets; 5 ) Protein degradation.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

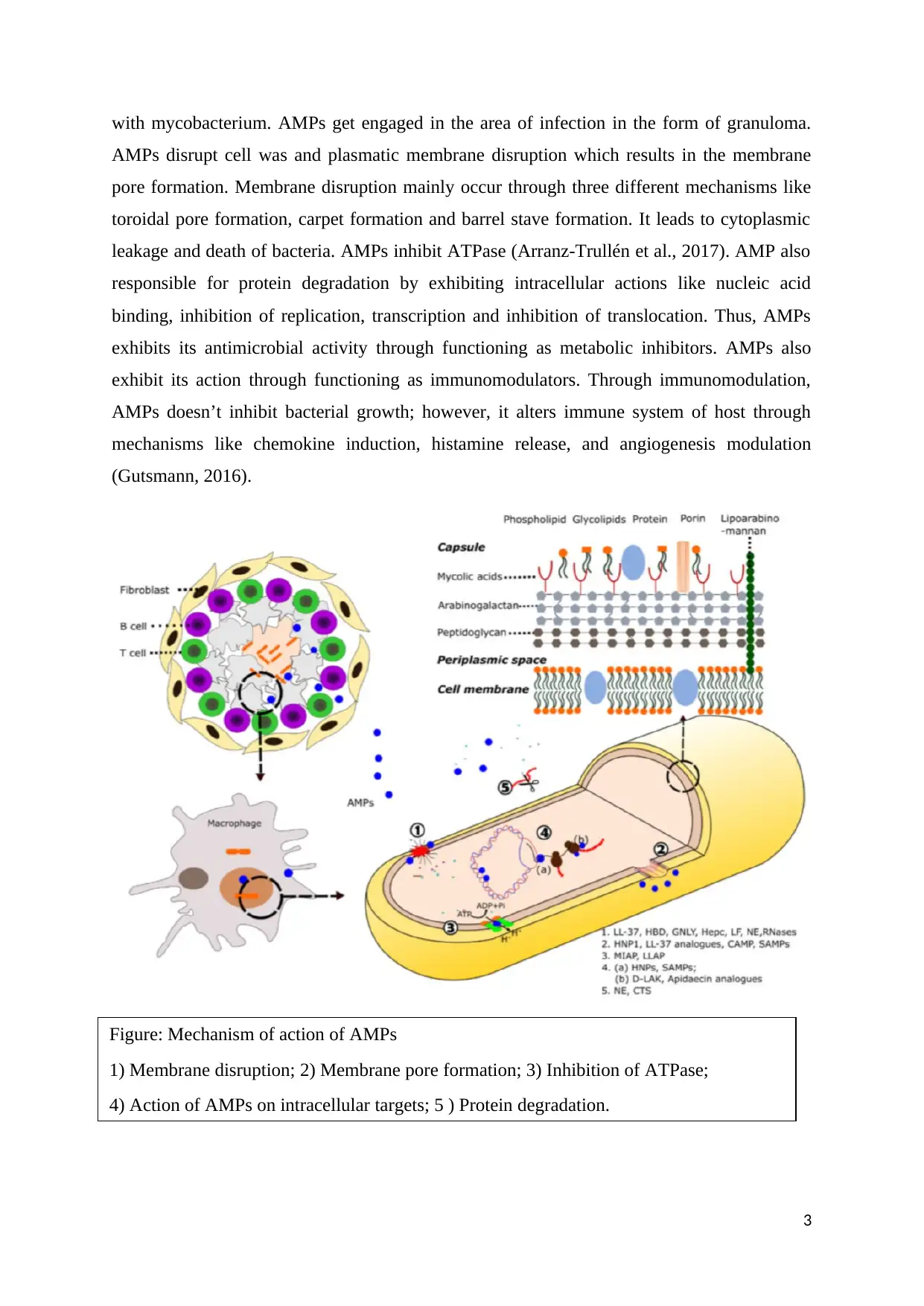

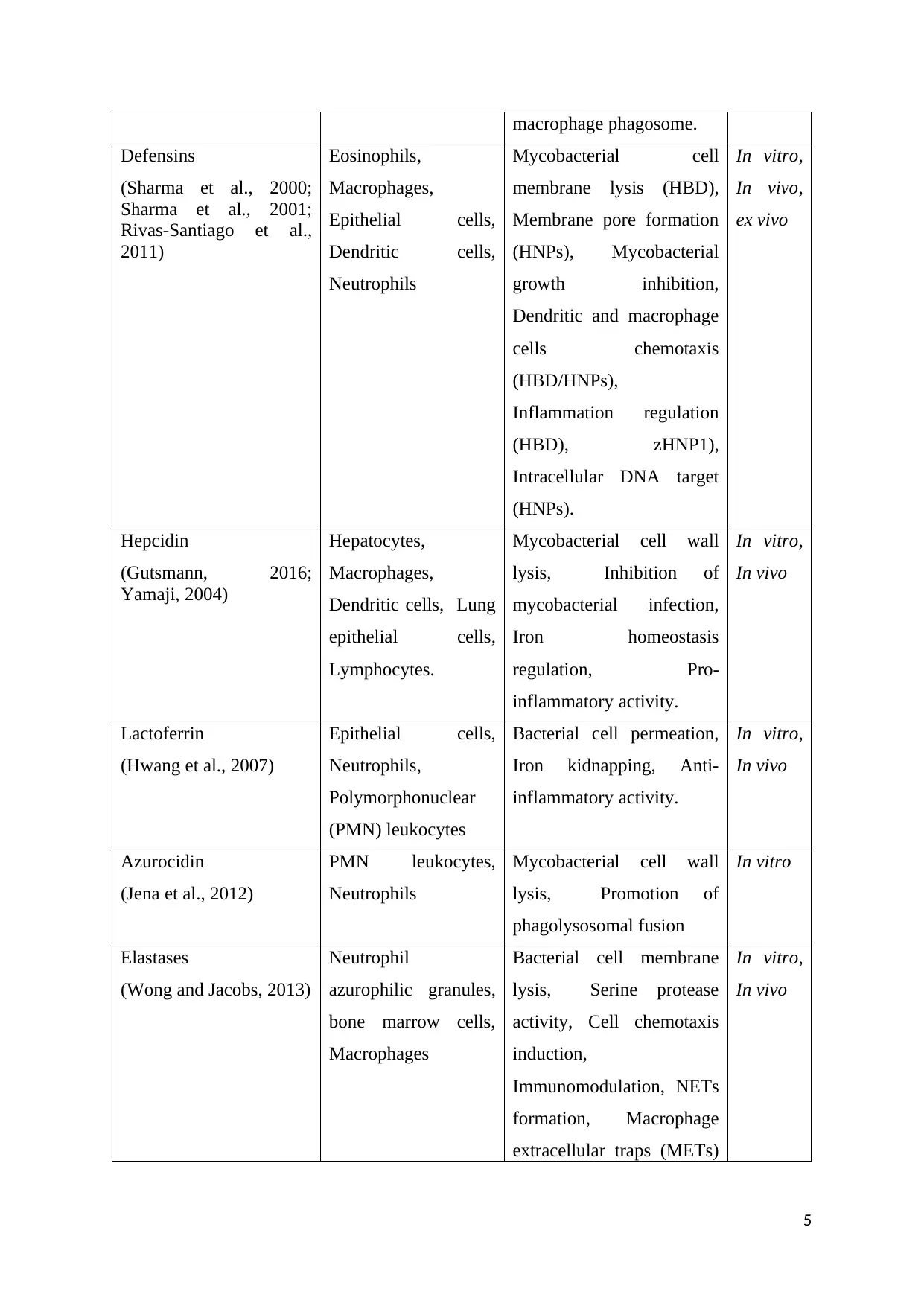

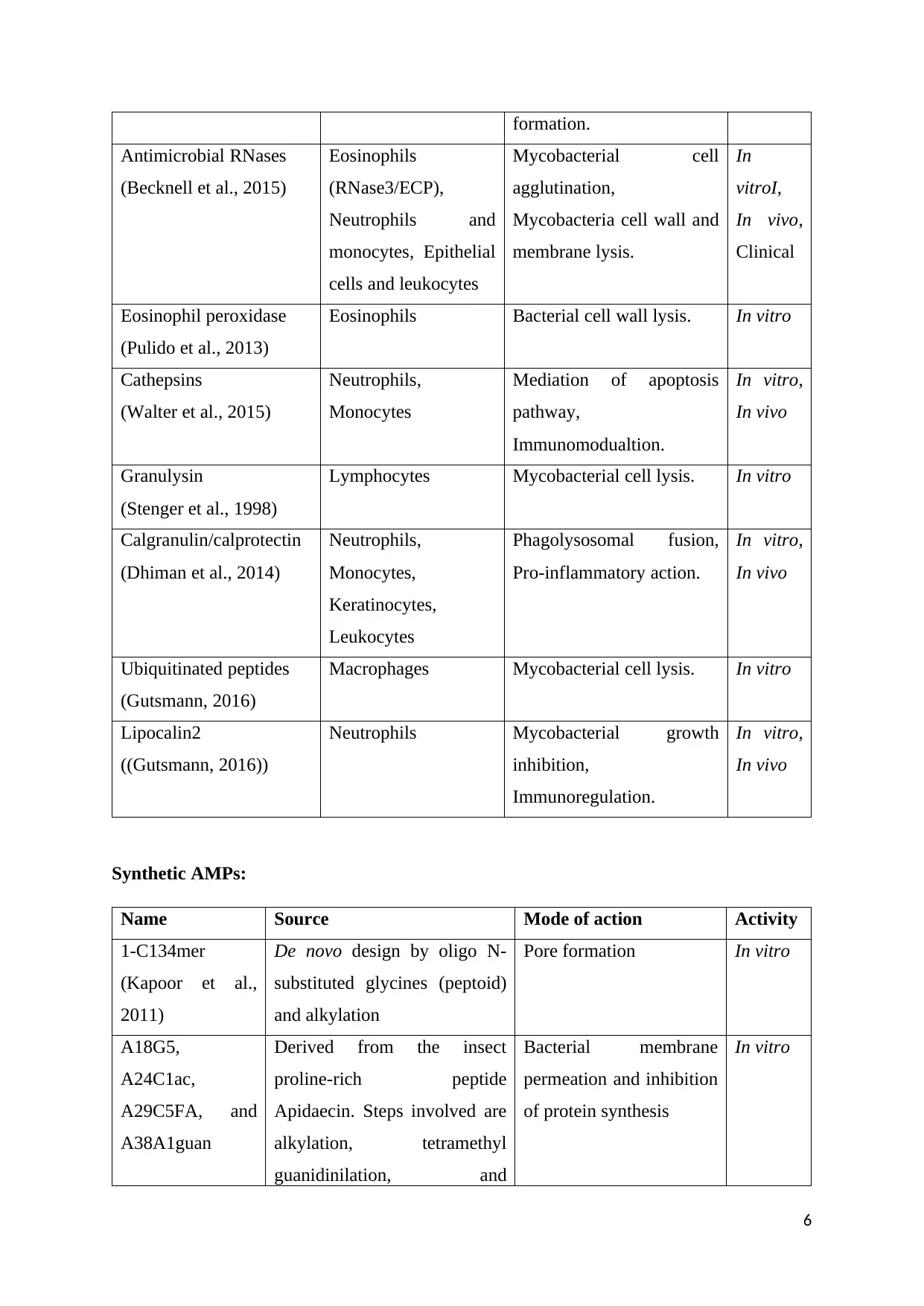

Human derived AMPs:

Human derived AMPs are mainly responsible for the immune host defense against

mycobacteria. Human AMPs include cathelicidin, defensins, hepcidins, lactoferrin,

azurocidin, elastases, antimicrobial RNases, eosinophil peroxidase, cathepsins, granulysin,

calgranulin/calprotectin, ubiquitinated peptides and lipocalin2 (Arranz-Trullén et al., 2017).

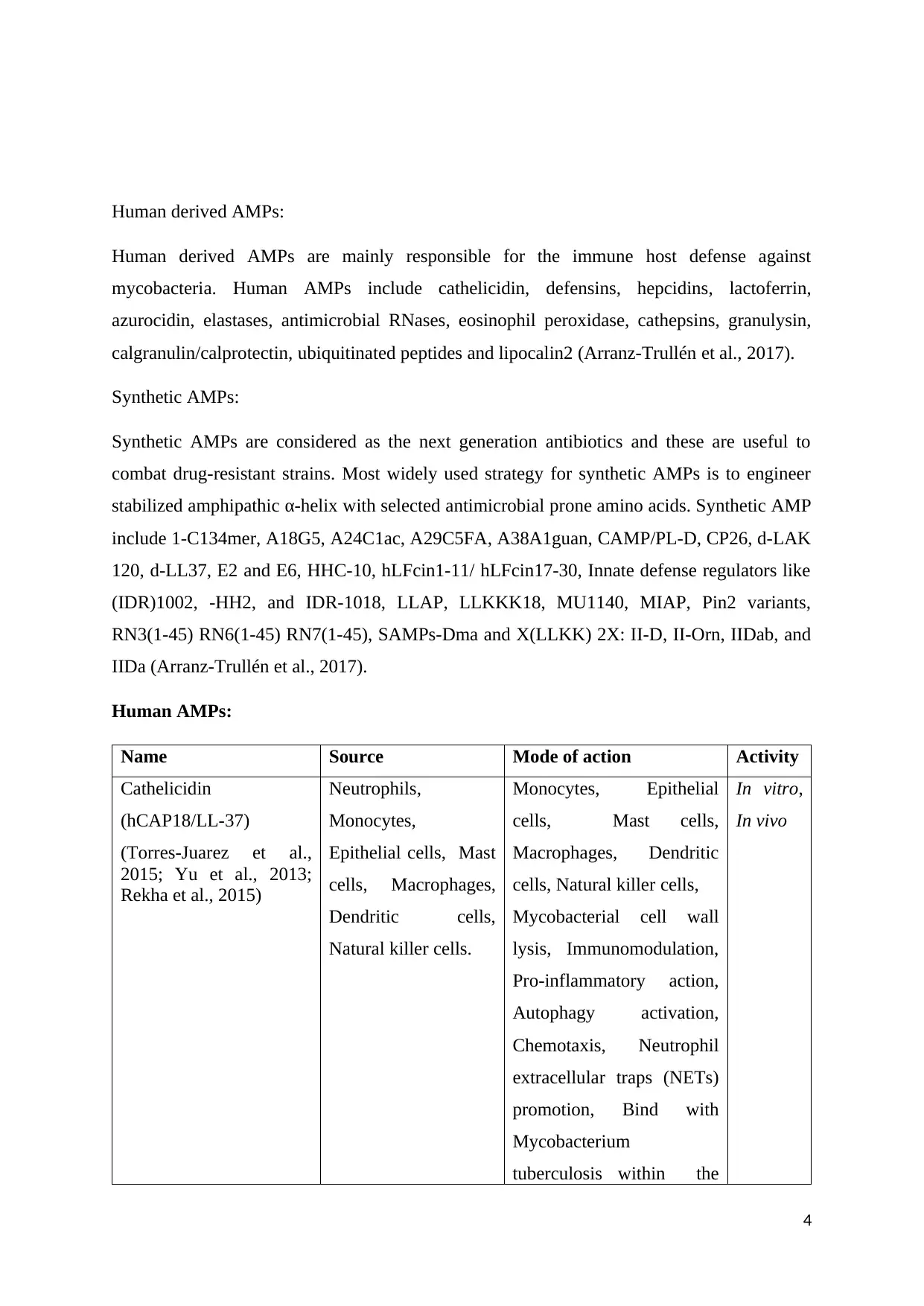

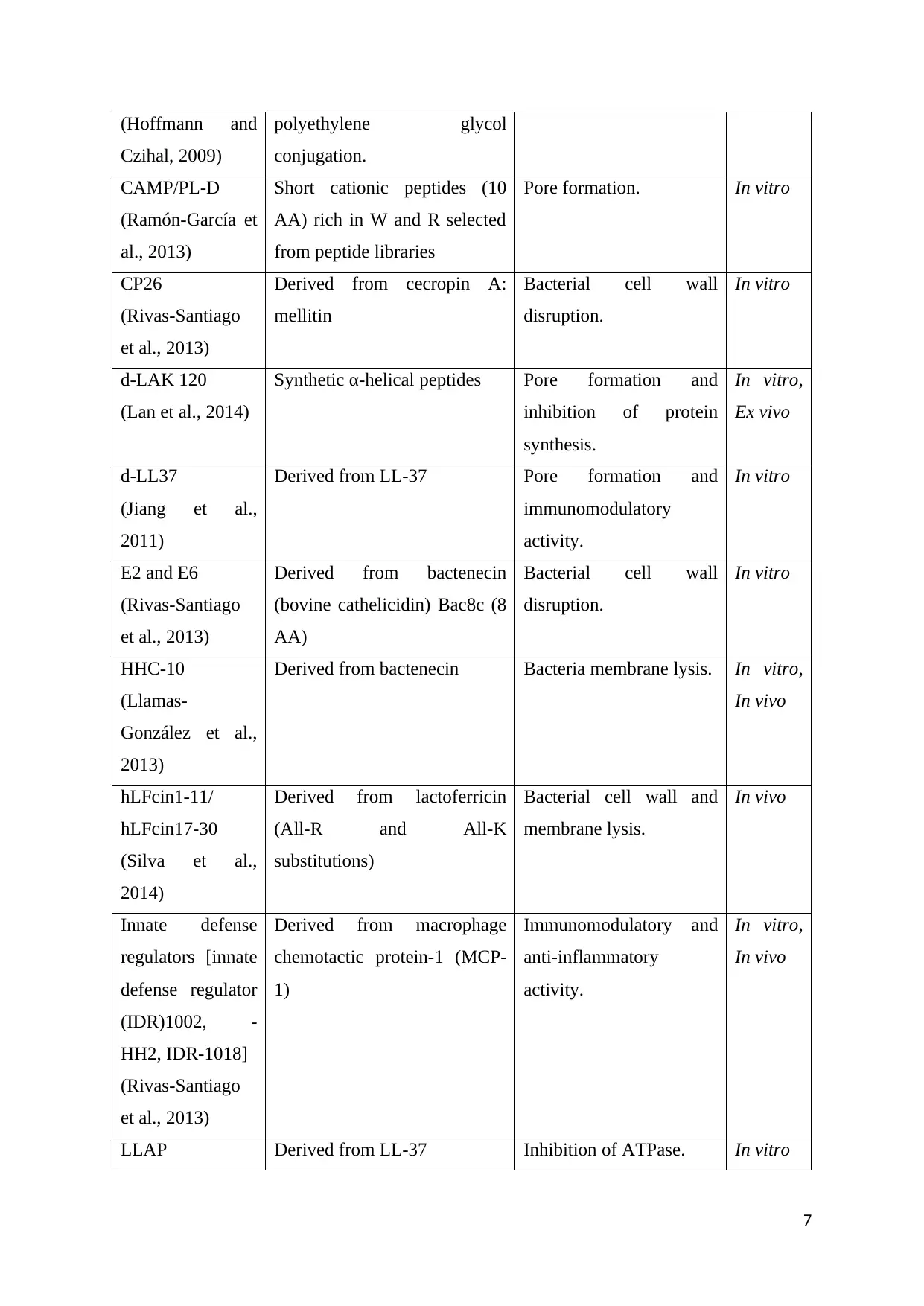

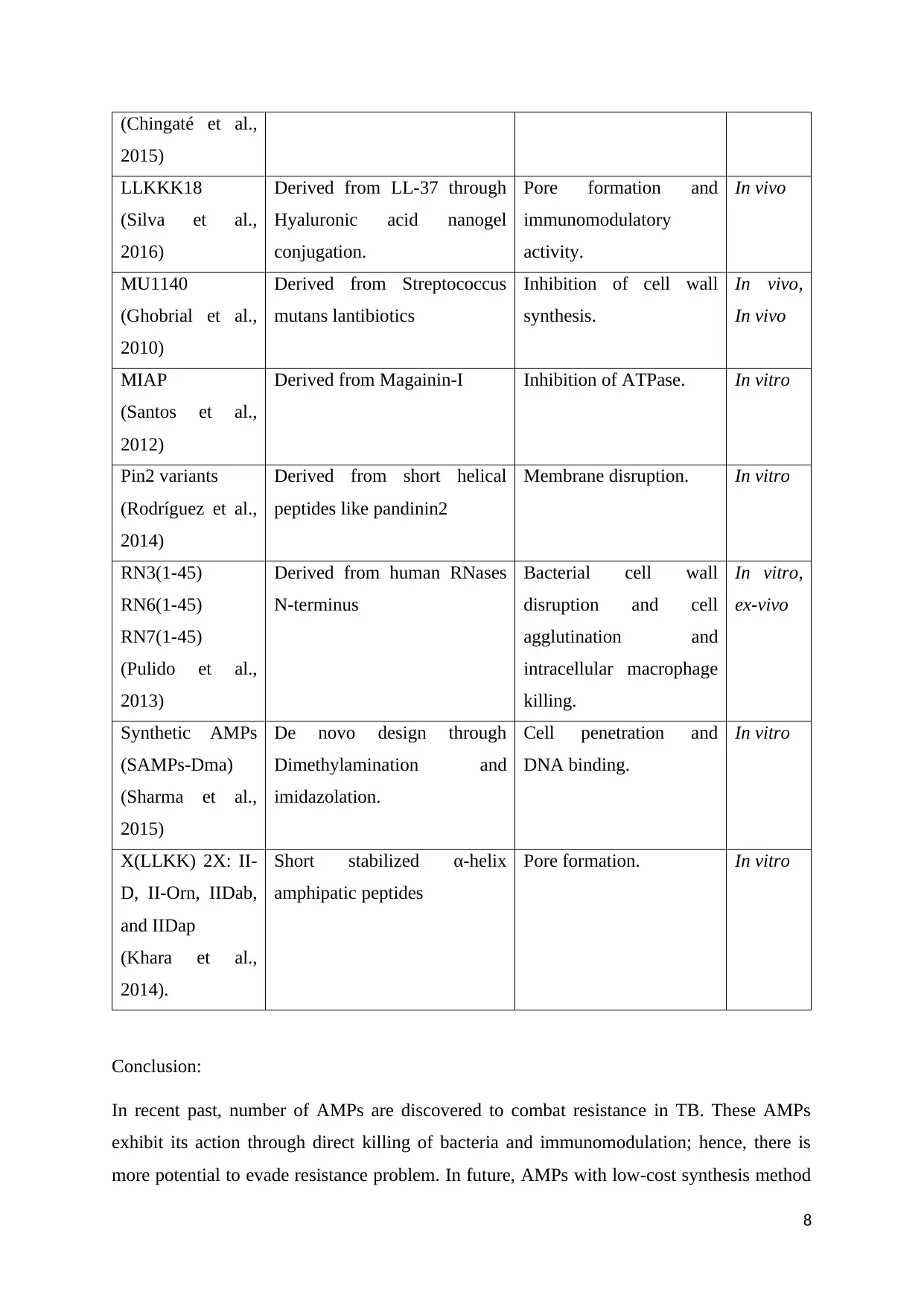

Synthetic AMPs:

Synthetic AMPs are considered as the next generation antibiotics and these are useful to

combat drug-resistant strains. Most widely used strategy for synthetic AMPs is to engineer

stabilized amphipathic α-helix with selected antimicrobial prone amino acids. Synthetic AMP

include 1-C134mer, A18G5, A24C1ac, A29C5FA, A38A1guan, CAMP/PL-D, CP26, d-LAK

120, d-LL37, E2 and E6, HHC-10, hLFcin1-11/ hLFcin17-30, Innate defense regulators like

(IDR)1002, -HH2, and IDR-1018, LLAP, LLKKK18, MU1140, MIAP, Pin2 variants,

RN3(1-45) RN6(1-45) RN7(1-45), SAMPs-Dma and X(LLKK) 2X: II-D, II-Orn, IIDab, and

IIDa (Arranz-Trullén et al., 2017).

Human AMPs:

Name Source Mode of action Activity

Cathelicidin

(hCAP18/LL-37)

(Torres-Juarez et al.,

2015; Yu et al., 2013;

Rekha et al., 2015)

Neutrophils,

Monocytes,

Epithelial cells, Mast

cells, Macrophages,

Dendritic cells,

Natural killer cells.

Monocytes, Epithelial

cells, Mast cells,

Macrophages, Dendritic

cells, Natural killer cells,

Mycobacterial cell wall

lysis, Immunomodulation,

Pro-inflammatory action,

Autophagy activation,

Chemotaxis, Neutrophil

extracellular traps (NETs)

promotion, Bind with

Mycobacterium

tuberculosis within the

In vitro,

In vivo

4

Human derived AMPs are mainly responsible for the immune host defense against

mycobacteria. Human AMPs include cathelicidin, defensins, hepcidins, lactoferrin,

azurocidin, elastases, antimicrobial RNases, eosinophil peroxidase, cathepsins, granulysin,

calgranulin/calprotectin, ubiquitinated peptides and lipocalin2 (Arranz-Trullén et al., 2017).

Synthetic AMPs:

Synthetic AMPs are considered as the next generation antibiotics and these are useful to

combat drug-resistant strains. Most widely used strategy for synthetic AMPs is to engineer

stabilized amphipathic α-helix with selected antimicrobial prone amino acids. Synthetic AMP

include 1-C134mer, A18G5, A24C1ac, A29C5FA, A38A1guan, CAMP/PL-D, CP26, d-LAK

120, d-LL37, E2 and E6, HHC-10, hLFcin1-11/ hLFcin17-30, Innate defense regulators like

(IDR)1002, -HH2, and IDR-1018, LLAP, LLKKK18, MU1140, MIAP, Pin2 variants,

RN3(1-45) RN6(1-45) RN7(1-45), SAMPs-Dma and X(LLKK) 2X: II-D, II-Orn, IIDab, and

IIDa (Arranz-Trullén et al., 2017).

Human AMPs:

Name Source Mode of action Activity

Cathelicidin

(hCAP18/LL-37)

(Torres-Juarez et al.,

2015; Yu et al., 2013;

Rekha et al., 2015)

Neutrophils,

Monocytes,

Epithelial cells, Mast

cells, Macrophages,

Dendritic cells,

Natural killer cells.

Monocytes, Epithelial

cells, Mast cells,

Macrophages, Dendritic

cells, Natural killer cells,

Mycobacterial cell wall

lysis, Immunomodulation,

Pro-inflammatory action,

Autophagy activation,

Chemotaxis, Neutrophil

extracellular traps (NETs)

promotion, Bind with

Mycobacterium

tuberculosis within the

In vitro,

In vivo

4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

macrophage phagosome.

Defensins

(Sharma et al., 2000;

Sharma et al., 2001;

Rivas-Santiago et al.,

2011)

Eosinophils,

Macrophages,

Epithelial cells,

Dendritic cells,

Neutrophils

Mycobacterial cell

membrane lysis (HBD),

Membrane pore formation

(HNPs), Mycobacterial

growth inhibition,

Dendritic and macrophage

cells chemotaxis

(HBD/HNPs),

Inflammation regulation

(HBD), zHNP1),

Intracellular DNA target

(HNPs).

In vitro,

In vivo,

ex vivo

Hepcidin

(Gutsmann, 2016;

Yamaji, 2004)

Hepatocytes,

Macrophages,

Dendritic cells, Lung

epithelial cells,

Lymphocytes.

Mycobacterial cell wall

lysis, Inhibition of

mycobacterial infection,

Iron homeostasis

regulation, Pro-

inflammatory activity.

In vitro,

In vivo

Lactoferrin

(Hwang et al., 2007)

Epithelial cells,

Neutrophils,

Polymorphonuclear

(PMN) leukocytes

Bacterial cell permeation,

Iron kidnapping, Anti-

inflammatory activity.

In vitro,

In vivo

Azurocidin

(Jena et al., 2012)

PMN leukocytes,

Neutrophils

Mycobacterial cell wall

lysis, Promotion of

phagolysosomal fusion

In vitro

Elastases

(Wong and Jacobs, 2013)

Neutrophil

azurophilic granules,

bone marrow cells,

Macrophages

Bacterial cell membrane

lysis, Serine protease

activity, Cell chemotaxis

induction,

Immunomodulation, NETs

formation, Macrophage

extracellular traps (METs)

In vitro,

In vivo

5

Defensins

(Sharma et al., 2000;

Sharma et al., 2001;

Rivas-Santiago et al.,

2011)

Eosinophils,

Macrophages,

Epithelial cells,

Dendritic cells,

Neutrophils

Mycobacterial cell

membrane lysis (HBD),

Membrane pore formation

(HNPs), Mycobacterial

growth inhibition,

Dendritic and macrophage

cells chemotaxis

(HBD/HNPs),

Inflammation regulation

(HBD), zHNP1),

Intracellular DNA target

(HNPs).

In vitro,

In vivo,

ex vivo

Hepcidin

(Gutsmann, 2016;

Yamaji, 2004)

Hepatocytes,

Macrophages,

Dendritic cells, Lung

epithelial cells,

Lymphocytes.

Mycobacterial cell wall

lysis, Inhibition of

mycobacterial infection,

Iron homeostasis

regulation, Pro-

inflammatory activity.

In vitro,

In vivo

Lactoferrin

(Hwang et al., 2007)

Epithelial cells,

Neutrophils,

Polymorphonuclear

(PMN) leukocytes

Bacterial cell permeation,

Iron kidnapping, Anti-

inflammatory activity.

In vitro,

In vivo

Azurocidin

(Jena et al., 2012)

PMN leukocytes,

Neutrophils

Mycobacterial cell wall

lysis, Promotion of

phagolysosomal fusion

In vitro

Elastases

(Wong and Jacobs, 2013)

Neutrophil

azurophilic granules,

bone marrow cells,

Macrophages

Bacterial cell membrane

lysis, Serine protease

activity, Cell chemotaxis

induction,

Immunomodulation, NETs

formation, Macrophage

extracellular traps (METs)

In vitro,

In vivo

5

formation.

Antimicrobial RNases

(Becknell et al., 2015)

Eosinophils

(RNase3/ECP),

Neutrophils and

monocytes, Epithelial

cells and leukocytes

Mycobacterial cell

agglutination,

Mycobacteria cell wall and

membrane lysis.

In

vitroI,

In vivo,

Clinical

Eosinophil peroxidase

(Pulido et al., 2013)

Eosinophils Bacterial cell wall lysis. In vitro

Cathepsins

(Walter et al., 2015)

Neutrophils,

Monocytes

Mediation of apoptosis

pathway,

Immunomodualtion.

In vitro,

In vivo

Granulysin

(Stenger et al., 1998)

Lymphocytes Mycobacterial cell lysis. In vitro

Calgranulin/calprotectin

(Dhiman et al., 2014)

Neutrophils,

Monocytes,

Keratinocytes,

Leukocytes

Phagolysosomal fusion,

Pro-inflammatory action.

In vitro,

In vivo

Ubiquitinated peptides

(Gutsmann, 2016)

Macrophages Mycobacterial cell lysis. In vitro

Lipocalin2

((Gutsmann, 2016))

Neutrophils Mycobacterial growth

inhibition,

Immunoregulation.

In vitro,

In vivo

Synthetic AMPs:

Name Source Mode of action Activity

1-C134mer

(Kapoor et al.,

2011)

De novo design by oligo N-

substituted glycines (peptoid)

and alkylation

Pore formation In vitro

A18G5,

A24C1ac,

A29C5FA, and

A38A1guan

Derived from the insect

proline-rich peptide

Apidaecin. Steps involved are

alkylation, tetramethyl

guanidinilation, and

Bacterial membrane

permeation and inhibition

of protein synthesis

In vitro

6

Antimicrobial RNases

(Becknell et al., 2015)

Eosinophils

(RNase3/ECP),

Neutrophils and

monocytes, Epithelial

cells and leukocytes

Mycobacterial cell

agglutination,

Mycobacteria cell wall and

membrane lysis.

In

vitroI,

In vivo,

Clinical

Eosinophil peroxidase

(Pulido et al., 2013)

Eosinophils Bacterial cell wall lysis. In vitro

Cathepsins

(Walter et al., 2015)

Neutrophils,

Monocytes

Mediation of apoptosis

pathway,

Immunomodualtion.

In vitro,

In vivo

Granulysin

(Stenger et al., 1998)

Lymphocytes Mycobacterial cell lysis. In vitro

Calgranulin/calprotectin

(Dhiman et al., 2014)

Neutrophils,

Monocytes,

Keratinocytes,

Leukocytes

Phagolysosomal fusion,

Pro-inflammatory action.

In vitro,

In vivo

Ubiquitinated peptides

(Gutsmann, 2016)

Macrophages Mycobacterial cell lysis. In vitro

Lipocalin2

((Gutsmann, 2016))

Neutrophils Mycobacterial growth

inhibition,

Immunoregulation.

In vitro,

In vivo

Synthetic AMPs:

Name Source Mode of action Activity

1-C134mer

(Kapoor et al.,

2011)

De novo design by oligo N-

substituted glycines (peptoid)

and alkylation

Pore formation In vitro

A18G5,

A24C1ac,

A29C5FA, and

A38A1guan

Derived from the insect

proline-rich peptide

Apidaecin. Steps involved are

alkylation, tetramethyl

guanidinilation, and

Bacterial membrane

permeation and inhibition

of protein synthesis

In vitro

6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

(Hoffmann and

Czihal, 2009)

polyethylene glycol

conjugation.

CAMP/PL-D

(Ramón-García et

al., 2013)

Short cationic peptides (10

AA) rich in W and R selected

from peptide libraries

Pore formation. In vitro

CP26

(Rivas-Santiago

et al., 2013)

Derived from cecropin A:

mellitin

Bacterial cell wall

disruption.

In vitro

d-LAK 120

(Lan et al., 2014)

Synthetic α-helical peptides Pore formation and

inhibition of protein

synthesis.

In vitro,

Ex vivo

d-LL37

(Jiang et al.,

2011)

Derived from LL-37 Pore formation and

immunomodulatory

activity.

In vitro

E2 and E6

(Rivas-Santiago

et al., 2013)

Derived from bactenecin

(bovine cathelicidin) Bac8c (8

AA)

Bacterial cell wall

disruption.

In vitro

HHC-10

(Llamas-

González et al.,

2013)

Derived from bactenecin Bacteria membrane lysis. In vitro,

In vivo

hLFcin1-11/

hLFcin17-30

(Silva et al.,

2014)

Derived from lactoferricin

(All-R and All-K

substitutions)

Bacterial cell wall and

membrane lysis.

In vivo

Innate defense

regulators [innate

defense regulator

(IDR)1002, -

HH2, IDR-1018]

(Rivas-Santiago

et al., 2013)

Derived from macrophage

chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-

1)

Immunomodulatory and

anti-inflammatory

activity.

In vitro,

In vivo

LLAP Derived from LL-37 Inhibition of ATPase. In vitro

7

Czihal, 2009)

polyethylene glycol

conjugation.

CAMP/PL-D

(Ramón-García et

al., 2013)

Short cationic peptides (10

AA) rich in W and R selected

from peptide libraries

Pore formation. In vitro

CP26

(Rivas-Santiago

et al., 2013)

Derived from cecropin A:

mellitin

Bacterial cell wall

disruption.

In vitro

d-LAK 120

(Lan et al., 2014)

Synthetic α-helical peptides Pore formation and

inhibition of protein

synthesis.

In vitro,

Ex vivo

d-LL37

(Jiang et al.,

2011)

Derived from LL-37 Pore formation and

immunomodulatory

activity.

In vitro

E2 and E6

(Rivas-Santiago

et al., 2013)

Derived from bactenecin

(bovine cathelicidin) Bac8c (8

AA)

Bacterial cell wall

disruption.

In vitro

HHC-10

(Llamas-

González et al.,

2013)

Derived from bactenecin Bacteria membrane lysis. In vitro,

In vivo

hLFcin1-11/

hLFcin17-30

(Silva et al.,

2014)

Derived from lactoferricin

(All-R and All-K

substitutions)

Bacterial cell wall and

membrane lysis.

In vivo

Innate defense

regulators [innate

defense regulator

(IDR)1002, -

HH2, IDR-1018]

(Rivas-Santiago

et al., 2013)

Derived from macrophage

chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-

1)

Immunomodulatory and

anti-inflammatory

activity.

In vitro,

In vivo

LLAP Derived from LL-37 Inhibition of ATPase. In vitro

7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

(Chingaté et al.,

2015)

LLKKK18

(Silva et al.,

2016)

Derived from LL-37 through

Hyaluronic acid nanogel

conjugation.

Pore formation and

immunomodulatory

activity.

In vivo

MU1140

(Ghobrial et al.,

2010)

Derived from Streptococcus

mutans lantibiotics

Inhibition of cell wall

synthesis.

In vivo,

In vivo

MIAP

(Santos et al.,

2012)

Derived from Magainin-I Inhibition of ATPase. In vitro

Pin2 variants

(Rodríguez et al.,

2014)

Derived from short helical

peptides like pandinin2

Membrane disruption. In vitro

RN3(1-45)

RN6(1-45)

RN7(1-45)

(Pulido et al.,

2013)

Derived from human RNases

N-terminus

Bacterial cell wall

disruption and cell

agglutination and

intracellular macrophage

killing.

In vitro,

ex-vivo

Synthetic AMPs

(SAMPs-Dma)

(Sharma et al.,

2015)

De novo design through

Dimethylamination and

imidazolation.

Cell penetration and

DNA binding.

In vitro

X(LLKK) 2X: II-

D, II-Orn, IIDab,

and IIDap

(Khara et al.,

2014).

Short stabilized α-helix

amphipatic peptides

Pore formation. In vitro

Conclusion:

In recent past, number of AMPs are discovered to combat resistance in TB. These AMPs

exhibit its action through direct killing of bacteria and immunomodulation; hence, there is

more potential to evade resistance problem. In future, AMPs with low-cost synthesis method

8

2015)

LLKKK18

(Silva et al.,

2016)

Derived from LL-37 through

Hyaluronic acid nanogel

conjugation.

Pore formation and

immunomodulatory

activity.

In vivo

MU1140

(Ghobrial et al.,

2010)

Derived from Streptococcus

mutans lantibiotics

Inhibition of cell wall

synthesis.

In vivo,

In vivo

MIAP

(Santos et al.,

2012)

Derived from Magainin-I Inhibition of ATPase. In vitro

Pin2 variants

(Rodríguez et al.,

2014)

Derived from short helical

peptides like pandinin2

Membrane disruption. In vitro

RN3(1-45)

RN6(1-45)

RN7(1-45)

(Pulido et al.,

2013)

Derived from human RNases

N-terminus

Bacterial cell wall

disruption and cell

agglutination and

intracellular macrophage

killing.

In vitro,

ex-vivo

Synthetic AMPs

(SAMPs-Dma)

(Sharma et al.,

2015)

De novo design through

Dimethylamination and

imidazolation.

Cell penetration and

DNA binding.

In vitro

X(LLKK) 2X: II-

D, II-Orn, IIDab,

and IIDap

(Khara et al.,

2014).

Short stabilized α-helix

amphipatic peptides

Pore formation. In vitro

Conclusion:

In recent past, number of AMPs are discovered to combat resistance in TB. These AMPs

exhibit its action through direct killing of bacteria and immunomodulation; hence, there is

more potential to evade resistance problem. In future, AMPs with low-cost synthesis method

8

should be prepared because its cost of synthesis is more. AMPs are susceptible to proteolytic

cleavage after systemic administration; hence, these should be produced using novel drug

delivery systems. It is essential to produce sufficient evidence to address the issues related to

peptide-based therapy for TB.

9

cleavage after systemic administration; hence, these should be produced using novel drug

delivery systems. It is essential to produce sufficient evidence to address the issues related to

peptide-based therapy for TB.

9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

References:

Arranz-Trullén, J., Lu, L., Pulido, D., Bhakta, S. and Boix, E. (2017) Host Antimicrobial

Peptides: The Promise of New Treatment Strategies against Tuberculosis. Frontiers in

Immunology, 8, 1499. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01499.

Becknell, B., Eichler, T.E., Beceiro, S., Li, B., Easterling, R.S. and Carpenter, A.R. (2015)

Ribonucleases 6 and 7 have antimicrobial function in the human and murine urinary tract.

Kidney International, 87, pp. 151–61. doi:10.1038/ki.2014.268.

Chingaté, S., Delgado, G., Salazar, L.M. and Soto, C.Y. (2015) The ATPase activity of the

mycobacterial plasma membrane is inhibited by the LL37-analogous peptide LLAP.

Peptides, 71, pp. 222–8. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2015.07.021.

Dhiman, R., Venkatasubramanian, S., Paidipally, P., Barnes, P.F., Tvinnereim, A. and

Vankayalapati, R. (2014) Interleukin 22 inhibits intracellular growth of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis by enhancing calgranulin an expression. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 209, pp.

578–87. doi:10.1093/infdis/jit495.

Gutsmann, T. (2016) Interaction between antimicrobial peptides and mycobacteria.

Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1858, pp. 1034–43. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem. 2016.01.031.

Ghobrial, O., Derendorf, H. and Hillman, J.D. (2010) Pharmacokinetic and

pharmacodynamic evaluation of the lantibiotic MU1140. Journal of Pharmaceutical

Sciences, 99, pp. 2521–8. doi:10.1002/jps.22015.

Hoffmann and Czihal. (2009) Antibiotic peptides Patent. WO2009013262 A1.

Hwang, S. A., Wilk, K.M., Bangale, Y.A., Kruzel, M.L. and Actor, J.K. (2007) Lactoferrin

modulation of IL-12 and IL-10 response from activated murine leukocytes. Medical

Microbiology and Immunology, 196, pp. 171–80. doi:10.1007/s00430-007-0041-6.

Jena, P., Mohanty, S., Mohanty, T., Kallert, S., Morgelin, M. and Lindstrøm, T. (2012)

Azurophil granule proteins constitute the major mycobactericidal proteins in human

neutrophils and enhance the killing of mycobacteria in macrophages. PLoS One, 7:e50345.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050345.

Jiang, Z., Higgins, M.P., Whitehurst, J., Kisich, K.O., Voskuil, M.I. and Hodges, R.S. (2011)

Antituberculosis activity of α-helical antimicrobial peptides: de novo designed L- and D-

enantiomers versus L- and D-LL-37. Protein & Peptide Letters, 18, pp. 241–52.

doi:10.2174/092986611794578288.

Kapoor, R., Eimerman, P.R., Hardy, J.W., Cirillo, J.D., Contag, C.H. and Barron, A.E. (2011)

Efficacy of antimicrobial peptoids against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrobial Agents

and Chemotherapy, 55, pp. 3058–62. doi:10.1128/AAC.01667-10.

Khara, J.S., Wang, Y., Ke, X. Y., Liu, S., Newton, S.M. and Langford, P.R. (2014).

Antimycobacterial activities of synthetic cationic α-helical peptides and their synergism with

rifampicin. Biomaterials, 35, pp. 2032–8. doi:10.1016/ j.biomaterials.2013.11.035.

Lan, Y., Lam, J.T., Siu, G.K.H., Yam, W.C., Mason, A.J. and Lam, J.K.W. (2014) Cationic

amphipathic D-enantiomeric antimicrobial peptides with in vitro and ex vivo activity against

10

Arranz-Trullén, J., Lu, L., Pulido, D., Bhakta, S. and Boix, E. (2017) Host Antimicrobial

Peptides: The Promise of New Treatment Strategies against Tuberculosis. Frontiers in

Immunology, 8, 1499. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01499.

Becknell, B., Eichler, T.E., Beceiro, S., Li, B., Easterling, R.S. and Carpenter, A.R. (2015)

Ribonucleases 6 and 7 have antimicrobial function in the human and murine urinary tract.

Kidney International, 87, pp. 151–61. doi:10.1038/ki.2014.268.

Chingaté, S., Delgado, G., Salazar, L.M. and Soto, C.Y. (2015) The ATPase activity of the

mycobacterial plasma membrane is inhibited by the LL37-analogous peptide LLAP.

Peptides, 71, pp. 222–8. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2015.07.021.

Dhiman, R., Venkatasubramanian, S., Paidipally, P., Barnes, P.F., Tvinnereim, A. and

Vankayalapati, R. (2014) Interleukin 22 inhibits intracellular growth of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis by enhancing calgranulin an expression. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 209, pp.

578–87. doi:10.1093/infdis/jit495.

Gutsmann, T. (2016) Interaction between antimicrobial peptides and mycobacteria.

Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1858, pp. 1034–43. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem. 2016.01.031.

Ghobrial, O., Derendorf, H. and Hillman, J.D. (2010) Pharmacokinetic and

pharmacodynamic evaluation of the lantibiotic MU1140. Journal of Pharmaceutical

Sciences, 99, pp. 2521–8. doi:10.1002/jps.22015.

Hoffmann and Czihal. (2009) Antibiotic peptides Patent. WO2009013262 A1.

Hwang, S. A., Wilk, K.M., Bangale, Y.A., Kruzel, M.L. and Actor, J.K. (2007) Lactoferrin

modulation of IL-12 and IL-10 response from activated murine leukocytes. Medical

Microbiology and Immunology, 196, pp. 171–80. doi:10.1007/s00430-007-0041-6.

Jena, P., Mohanty, S., Mohanty, T., Kallert, S., Morgelin, M. and Lindstrøm, T. (2012)

Azurophil granule proteins constitute the major mycobactericidal proteins in human

neutrophils and enhance the killing of mycobacteria in macrophages. PLoS One, 7:e50345.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050345.

Jiang, Z., Higgins, M.P., Whitehurst, J., Kisich, K.O., Voskuil, M.I. and Hodges, R.S. (2011)

Antituberculosis activity of α-helical antimicrobial peptides: de novo designed L- and D-

enantiomers versus L- and D-LL-37. Protein & Peptide Letters, 18, pp. 241–52.

doi:10.2174/092986611794578288.

Kapoor, R., Eimerman, P.R., Hardy, J.W., Cirillo, J.D., Contag, C.H. and Barron, A.E. (2011)

Efficacy of antimicrobial peptoids against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrobial Agents

and Chemotherapy, 55, pp. 3058–62. doi:10.1128/AAC.01667-10.

Khara, J.S., Wang, Y., Ke, X. Y., Liu, S., Newton, S.M. and Langford, P.R. (2014).

Antimycobacterial activities of synthetic cationic α-helical peptides and their synergism with

rifampicin. Biomaterials, 35, pp. 2032–8. doi:10.1016/ j.biomaterials.2013.11.035.

Lan, Y., Lam, J.T., Siu, G.K.H., Yam, W.C., Mason, A.J. and Lam, J.K.W. (2014) Cationic

amphipathic D-enantiomeric antimicrobial peptides with in vitro and ex vivo activity against

10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis, 94, pp. 678–89.

doi:10.1016/j.tube.2014.08.001.

Llamas-González, Y.Y., Pedroza-Roldán, C., Cortés-Serna, M.B., MárquezAguirre, A.L.,

Gálvez-Gastélum, F.J. and Flores-Valdez, M.A. (2013) The synthetic cathelicidin HHC-10

inhibits Mycobacterium bovis BCG in vitro and in C57BL/6 mice. Microbial Drug

Resistance, 19, pp. 124–9. doi:10.1089/mdr.2012.0149.

Mandal, S.M., Roy, A., Ghosh, A.K., Hazra, T.K., Basak, A. and Franco, O.L. (2014)

Challenges and future prospects of antibiotic therapy: from peptides to phages utilization.

Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 5. p. 105. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00105.

Pulido, D., Torrent, M., Andreu, D., Nogues, M.V. and Boix, E. (2013) Two human host

defense ribonucleases against mycobacteria, the eosinophil cationic protein (RNase 3) and

RNase 7. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 57, pp. 3797–805.

doi:10.1128/AAC.00428-13.

Ramón-García, S., Mikut, R., Ng, C., Ruden, S., Volkmer, R. and Reischl, M. (2013)

Targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other microbial pathogens using improved

synthetic antibacterial peptides. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 57, pp. 2295–303.

doi:10.1128/AAC.00175-13.

Rekha, R.S., Rao Muvva, S.S.V.J., Wan, M., Raqib, R., Bergman, P. and Brighenti, S. (2015)

Phenylbutyrate induces LL-37-dependent autophagy and intracellular killing of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human macrophages. Autophagy, 11, pp. 1688–99.

doi:10.1080/15548627.2015.1075110.

Rivas-Santiago, B., Rivas Santiago, C.E., Castañeda-Delgado, J.E., LeónContreras, J.C.,

Hancock, R.E.W. and Hernandez-Pando, R. (2013) Activity of LL-37, CRAMP and

antimicrobial peptide-derived compounds E2, E6 and CP26 against Mycobacterium

tuberculosis. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 41, pp. 143–8.

doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.09.015.

Rodríguez, A., Villegas, E., Montoya-Rosales, A., Rivas-Santiago, B. and Corzo, G. (2014).

Characterization of antibacterial and hemolytic activity of synthetic pandinin 2 variants and

their inhibition against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One, 9, e101742.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101742.

Rivas-Santiago, B., Castañeda-Delgado, J.E., Rivas Santiago, C.E., Waldbrook, M.,

González-Curiel, I. and León-Contreras, J.C. (2013) Ability of innate defence regulator

peptides IDR-1002, IDR-HH2 and IDR-1018 to protect against Mycobacterium tuberculosis

infections in animal models. PLoS One, 8, e59119. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059119.

Rivas-Santiago, C.E., Rivas-Santiago, B., León, D.A., Castañeda-Delgado, J. and Hernández

Pando, R. (2011) Induction of β-defensins by l-isoleucine as novel immunotherapy in

experimental murine tuberculosis. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 164, pp. 80–9.

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04313.x.

Santos, P., Gordillo, A., Osses, L., Salazar, L.M. and Soto, C.Y. (2012) Effect of

antimicrobial peptides on ATPase activity and proton pumping in plasma membrane vesicles

obtained from mycobacteria. Peptides, 36, pp. 121–8. doi:10.1016/ j.peptides.2012.04.018.

11

doi:10.1016/j.tube.2014.08.001.

Llamas-González, Y.Y., Pedroza-Roldán, C., Cortés-Serna, M.B., MárquezAguirre, A.L.,

Gálvez-Gastélum, F.J. and Flores-Valdez, M.A. (2013) The synthetic cathelicidin HHC-10

inhibits Mycobacterium bovis BCG in vitro and in C57BL/6 mice. Microbial Drug

Resistance, 19, pp. 124–9. doi:10.1089/mdr.2012.0149.

Mandal, S.M., Roy, A., Ghosh, A.K., Hazra, T.K., Basak, A. and Franco, O.L. (2014)

Challenges and future prospects of antibiotic therapy: from peptides to phages utilization.

Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 5. p. 105. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00105.

Pulido, D., Torrent, M., Andreu, D., Nogues, M.V. and Boix, E. (2013) Two human host

defense ribonucleases against mycobacteria, the eosinophil cationic protein (RNase 3) and

RNase 7. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 57, pp. 3797–805.

doi:10.1128/AAC.00428-13.

Ramón-García, S., Mikut, R., Ng, C., Ruden, S., Volkmer, R. and Reischl, M. (2013)

Targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other microbial pathogens using improved

synthetic antibacterial peptides. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 57, pp. 2295–303.

doi:10.1128/AAC.00175-13.

Rekha, R.S., Rao Muvva, S.S.V.J., Wan, M., Raqib, R., Bergman, P. and Brighenti, S. (2015)

Phenylbutyrate induces LL-37-dependent autophagy and intracellular killing of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human macrophages. Autophagy, 11, pp. 1688–99.

doi:10.1080/15548627.2015.1075110.

Rivas-Santiago, B., Rivas Santiago, C.E., Castañeda-Delgado, J.E., LeónContreras, J.C.,

Hancock, R.E.W. and Hernandez-Pando, R. (2013) Activity of LL-37, CRAMP and

antimicrobial peptide-derived compounds E2, E6 and CP26 against Mycobacterium

tuberculosis. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 41, pp. 143–8.

doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.09.015.

Rodríguez, A., Villegas, E., Montoya-Rosales, A., Rivas-Santiago, B. and Corzo, G. (2014).

Characterization of antibacterial and hemolytic activity of synthetic pandinin 2 variants and

their inhibition against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One, 9, e101742.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101742.

Rivas-Santiago, B., Castañeda-Delgado, J.E., Rivas Santiago, C.E., Waldbrook, M.,

González-Curiel, I. and León-Contreras, J.C. (2013) Ability of innate defence regulator

peptides IDR-1002, IDR-HH2 and IDR-1018 to protect against Mycobacterium tuberculosis

infections in animal models. PLoS One, 8, e59119. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059119.

Rivas-Santiago, C.E., Rivas-Santiago, B., León, D.A., Castañeda-Delgado, J. and Hernández

Pando, R. (2011) Induction of β-defensins by l-isoleucine as novel immunotherapy in

experimental murine tuberculosis. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 164, pp. 80–9.

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04313.x.

Santos, P., Gordillo, A., Osses, L., Salazar, L.M. and Soto, C.Y. (2012) Effect of

antimicrobial peptides on ATPase activity and proton pumping in plasma membrane vesicles

obtained from mycobacteria. Peptides, 36, pp. 121–8. doi:10.1016/ j.peptides.2012.04.018.

11

Sharma, S., Verma, I. and Khuller, G.K. (2000) Antibacterial activity of human neutrophil

peptide-1 against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv: in vitro and ex vivo study. European

Respiratory Journal, 16, pp. 112–7. doi:10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16a20.x 50.

Sharma, S., Verma, I. and Khuller, G.K. (2001) Therapeutic potential of human neutrophil

peptide 1 against experimental tuberculosis. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 45, pp.

639–40. doi:10.1128/AAC.45.2.639-640.2001.

Sharma, A., Pohane, A.A., Bansal, S., Bajaj, A., Jain, V. and Srivastava, A. (2015) Cell

penetrating synthetic antimicrobial peptides (SAMPs) exhibiting potent and selective killing

of Mycobacterium by targeting its DNA. Chemistry, 21, pp. 3540–5.

doi:10.1002/chem.201404650.

Silva, T., Magalhães, B., Maia, S., Gomes, P., Nazmi, K. and Bolscher, J.G.M. (2014) Killing

of Mycobacterium avium by lactoferricin peptides: improved activity of arginine- and d-

amino-acid-containing molecules. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 58, pp. 3461–7.

doi:10.1128/AAC.02728-13.

Silva, J.P., Gonçalves, C., Costa, C., Sousa, J., Silva-Gomes, R. and Castro, A.G. (2016).

Delivery of LLKKK18 loaded into self-assembling hyaluronic acid nanogel for tuberculosis

treatment. Journal of Controlled Release, 235, pp. 112–24. doi:10.1016/

j.jconrel.2016.05.064.

Stenger, S., Hanson, D.A., Teitelbaum, R., Dewan, P., Niazi, K.R. and Froelich, C.J. (1998)

An antimicrobial activity of cytolytic T cells mediated by granulysin. Science, 282, pp. 121–

5. doi:10.1126/science.282.5386.121.

Torres-Juarez, F., Cardenas-Vargas, A., Montoya-Rosales, A., González-Curiel, I., Garcia-

Hernandez, M.H. and Enciso-Moreno, J.A. (2015) LL-37 immunomodulatory activity during

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in macrophages. Infection and Immunity, 83, pp. 4495–

503. doi:10.1128/IAI.00936-15 58.

Venketaraman, V., Kaushal, D. and Saviola, B. (2015) Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal

of Immunology Research, 857598. doi: 10.1155/2015/857598.

Walter, K., Steinwede, K., Aly, S., Reinheckel, T., Bohling, J. and Maus, U.A. (2015)

Cathepsin G in experimental tuberculosis: relevance for antibacterial protection and potential

for immunotherapy. Journal of Immunology, 195, pp. 3325–33.

doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1501012.

Wong, K.W. and Jacobs, W.R. (2013) Mycobacterium tuberculosis exploits human interferon

γ to stimulate macrophage extracellular trap formation and necrosis. Journal of Infectious

Diseases, 208, pp. 109–19. doi:10.1093/infdis/jit097.

Yamaji, S (2004) Inhibition of iron transport across human intestinal epithelial cells by

hepcidin. Blood, 104, pp. 2178–80. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-03-0829.

Yu, X., Li, C., Hong, W., Pan, W. and Xie, J. (2013) Autophagy during Mycobacterium

tuberculosis infection and implications for future tuberculosis medications. Cell Signal, 25,

pp. 1272–8. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.02.011.

12

peptide-1 against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv: in vitro and ex vivo study. European

Respiratory Journal, 16, pp. 112–7. doi:10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16a20.x 50.

Sharma, S., Verma, I. and Khuller, G.K. (2001) Therapeutic potential of human neutrophil

peptide 1 against experimental tuberculosis. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 45, pp.

639–40. doi:10.1128/AAC.45.2.639-640.2001.

Sharma, A., Pohane, A.A., Bansal, S., Bajaj, A., Jain, V. and Srivastava, A. (2015) Cell

penetrating synthetic antimicrobial peptides (SAMPs) exhibiting potent and selective killing

of Mycobacterium by targeting its DNA. Chemistry, 21, pp. 3540–5.

doi:10.1002/chem.201404650.

Silva, T., Magalhães, B., Maia, S., Gomes, P., Nazmi, K. and Bolscher, J.G.M. (2014) Killing

of Mycobacterium avium by lactoferricin peptides: improved activity of arginine- and d-

amino-acid-containing molecules. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 58, pp. 3461–7.

doi:10.1128/AAC.02728-13.

Silva, J.P., Gonçalves, C., Costa, C., Sousa, J., Silva-Gomes, R. and Castro, A.G. (2016).

Delivery of LLKKK18 loaded into self-assembling hyaluronic acid nanogel for tuberculosis

treatment. Journal of Controlled Release, 235, pp. 112–24. doi:10.1016/

j.jconrel.2016.05.064.

Stenger, S., Hanson, D.A., Teitelbaum, R., Dewan, P., Niazi, K.R. and Froelich, C.J. (1998)

An antimicrobial activity of cytolytic T cells mediated by granulysin. Science, 282, pp. 121–

5. doi:10.1126/science.282.5386.121.

Torres-Juarez, F., Cardenas-Vargas, A., Montoya-Rosales, A., González-Curiel, I., Garcia-

Hernandez, M.H. and Enciso-Moreno, J.A. (2015) LL-37 immunomodulatory activity during

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in macrophages. Infection and Immunity, 83, pp. 4495–

503. doi:10.1128/IAI.00936-15 58.

Venketaraman, V., Kaushal, D. and Saviola, B. (2015) Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal

of Immunology Research, 857598. doi: 10.1155/2015/857598.

Walter, K., Steinwede, K., Aly, S., Reinheckel, T., Bohling, J. and Maus, U.A. (2015)

Cathepsin G in experimental tuberculosis: relevance for antibacterial protection and potential

for immunotherapy. Journal of Immunology, 195, pp. 3325–33.

doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1501012.

Wong, K.W. and Jacobs, W.R. (2013) Mycobacterium tuberculosis exploits human interferon

γ to stimulate macrophage extracellular trap formation and necrosis. Journal of Infectious

Diseases, 208, pp. 109–19. doi:10.1093/infdis/jit097.

Yamaji, S (2004) Inhibition of iron transport across human intestinal epithelial cells by

hepcidin. Blood, 104, pp. 2178–80. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-03-0829.

Yu, X., Li, C., Hong, W., Pan, W. and Xie, J. (2013) Autophagy during Mycobacterium

tuberculosis infection and implications for future tuberculosis medications. Cell Signal, 25,

pp. 1272–8. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.02.011.

12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 12

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.