UK Fast Food: Service Quality Dimensions and Customer Satisfaction

VerifiedAdded on 2022/01/22

|15

|8989

|476

Report

AI Summary

This report investigates the impact of the five dimensions of service quality (tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy) on customer satisfaction within the UK fast food market, focusing on KFC, McDonald's, and Burger King. Primary data was collected through questionnaires from customers at these restaurants. The findings indicate that tangibles, responsiveness, and assurance are the most significant drivers of customer satisfaction, followed by reliability and empathy, with tangibles having the most impact. The research contributes original insights into the British fast food market, highlighting the importance of physical facilities and attributes. The study uses the SERVPERF model to measure service quality and provides managerial implications for improving service quality and customer satisfaction in the competitive UK fast food industry.

ABSTRACT

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to examine the impact of the five dimensions of service quality on

customer satisfaction in the UK fast food market and to indicate which factors among the five dimensions

have a main role in driving overall customer satisfaction.

Design/methodology/approach: Primary data in the form of 147 questionnaire responses werebeen

collected from a variety of quick service fast food restaurants in the UK. Likert seven-point rating scales

were used to structure the questionnaire. Data were collected from the customers at two KFC restaurants,

two McDonald’s restaurants, and one Burger King Restaurant.

Findings: The results of the analysis indicate that tangibles, responsiveness and assurance play the most

important role in driving customer satisfaction in the UK fast food industry, followed by reliability and

empathy. Results of correlation and regression analysis show that physical attributes (tangible) of service

quality are key to customer satisfaction. In a nutshell, the tangibles variable is the most important factor

driving customer satisfaction in the context of the UK fast food market.

Originality/value: This research incoporates unique and original insights in relation to the British fast food

restaurants market and the results constitute novel findings pertaining to the importance of physical

facilities and attributes. This account of the relative importance of service quality dimensions in fast food

restaurants in the UK adds value to the field. The findings of this research have contributed to a better

understanding of the main factors that influence service quality and customer satisfaction and have

implications from a managerial point of view in the highly competitive UK fast food and wider foodservice

industry.

1. Introduction

The global fast food restaurant industry has experienced strong growth in recent years in response to

changes in consumer tastes and challenging global economic conditions. According to IBISWorld (2015),

in the period since the global financial crisis and theworldwide decrease in individuals’ income there has

been a decline in spending on luxuries such as eating out which has increased consumerpreferences for

lower-priced and more convenient food options. Globally, the fast food market has shown modest growth

since 2011 reaching a total value of $2, 849,950.5 in 2015 (Marketline, 2016). In terms of global

segmentation of the foodservice industry, full service restaurants represent 40% of the market value,

quick service restaurants (QSR) and fast food are the second largest segment of the market with 22% of

market value, while pubs, clubs and bars have 11% of the market value and 9% relates to the

accommodation sector (Marketline, 2016). .

The foodservice industry in the UK grew by an annual compounded rate of 2.3% over the period 2012-

2016 and by 2.6% in 2016 to reach a total value of $95.5 billion (Marketline, 2017). The foodservice

industry in the UK is structurally different in relation to the most important sectors with pubs, clubs and

bars representing 35.7% of total market value, followed by the quick service restaurant and fast food

sector with 26.1% and full service restaurants with only 15.5%. This is a significant cultural difference in

preferences for foodservice encounters and differs markedly in comparison to other European and

Western contexts, and relates to the popularity of eating out in pubs as evidenced in the growth of chains

such as Wetherspoons and the higher-quality gastro-pub market. When it comes specifically to the fast

food industry in the United Kingdom the sectoroverall has seen major developments over the years such

as the introduction of the drive-through restaurant format in the 1980s (Duffill and Martin, 1993) and the

current expansion of home delivery services . It is clear that the global fast food industry and the UK fast

food market in particular, have grown consistently in the recent past and generatesignificant annual

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to examine the impact of the five dimensions of service quality on

customer satisfaction in the UK fast food market and to indicate which factors among the five dimensions

have a main role in driving overall customer satisfaction.

Design/methodology/approach: Primary data in the form of 147 questionnaire responses werebeen

collected from a variety of quick service fast food restaurants in the UK. Likert seven-point rating scales

were used to structure the questionnaire. Data were collected from the customers at two KFC restaurants,

two McDonald’s restaurants, and one Burger King Restaurant.

Findings: The results of the analysis indicate that tangibles, responsiveness and assurance play the most

important role in driving customer satisfaction in the UK fast food industry, followed by reliability and

empathy. Results of correlation and regression analysis show that physical attributes (tangible) of service

quality are key to customer satisfaction. In a nutshell, the tangibles variable is the most important factor

driving customer satisfaction in the context of the UK fast food market.

Originality/value: This research incoporates unique and original insights in relation to the British fast food

restaurants market and the results constitute novel findings pertaining to the importance of physical

facilities and attributes. This account of the relative importance of service quality dimensions in fast food

restaurants in the UK adds value to the field. The findings of this research have contributed to a better

understanding of the main factors that influence service quality and customer satisfaction and have

implications from a managerial point of view in the highly competitive UK fast food and wider foodservice

industry.

1. Introduction

The global fast food restaurant industry has experienced strong growth in recent years in response to

changes in consumer tastes and challenging global economic conditions. According to IBISWorld (2015),

in the period since the global financial crisis and theworldwide decrease in individuals’ income there has

been a decline in spending on luxuries such as eating out which has increased consumerpreferences for

lower-priced and more convenient food options. Globally, the fast food market has shown modest growth

since 2011 reaching a total value of $2, 849,950.5 in 2015 (Marketline, 2016). In terms of global

segmentation of the foodservice industry, full service restaurants represent 40% of the market value,

quick service restaurants (QSR) and fast food are the second largest segment of the market with 22% of

market value, while pubs, clubs and bars have 11% of the market value and 9% relates to the

accommodation sector (Marketline, 2016). .

The foodservice industry in the UK grew by an annual compounded rate of 2.3% over the period 2012-

2016 and by 2.6% in 2016 to reach a total value of $95.5 billion (Marketline, 2017). The foodservice

industry in the UK is structurally different in relation to the most important sectors with pubs, clubs and

bars representing 35.7% of total market value, followed by the quick service restaurant and fast food

sector with 26.1% and full service restaurants with only 15.5%. This is a significant cultural difference in

preferences for foodservice encounters and differs markedly in comparison to other European and

Western contexts, and relates to the popularity of eating out in pubs as evidenced in the growth of chains

such as Wetherspoons and the higher-quality gastro-pub market. When it comes specifically to the fast

food industry in the United Kingdom the sectoroverall has seen major developments over the years such

as the introduction of the drive-through restaurant format in the 1980s (Duffill and Martin, 1993) and the

current expansion of home delivery services . It is clear that the global fast food industry and the UK fast

food market in particular, have grown consistently in the recent past and generatesignificant annual

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

revenue. This makes for a promising operational context for fast food chains to improve their performance

and increase profits, especially in the UK. This study therefore investigates the impact of service quality

on customer satisfaction in the UK fast food restaurant industry for the purposes of developing

understanding that might help drive such continued growth.

For this study, three leading chains in the UK fast food restaurant industry are taken as subjects:

Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC), McDonald’s and Burger King. The three chains selected for this study

together constitute 50% of the total value in the UK fast food market with McDonald’s the leading brand

with 28,8%, Kentucky Fried Chicken with 12.5% and Burger King with 8.7% (Euromonitor International,

2017). The three restaurants also represent the only significant players in the quick service restaurant

sector nationally and currently operate in a diverse fast food market where there are significant

challenges from Greggs bakery (8.7% of market value), Subway (6.6%), and the casual dining sector

which includes Nando’s (7.7%) (Euromonitor International, 2017). In a competitive environment such as

this, it is important that quick service restaurants are able to understand the determinants of service

quality and customer satisfaction.

Service quality can be seen as one of the key factors affecting customer satisfaction. Due to time and

length restrictions, the research addresses the impact of service quality on customer satisfaction results

of KFC, McDonald’s and Burger King restaurants through the five dimensions of the SERVPERF model,

namely tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance and empathy. The purpose of this study is to

examine relationships between the five dimensions of service quality and customer satisfaction in order to

find out which factors drive customer satisfaction. More importantly, the results of the research will

contribute to the development of service quality as well as of customer satisfaction in fast food companies

in the UK. This study seeks to answer the following questions:

To identify specific service quality dimensions that have an impact on customer satisfaction in the

UK fast food restaurant market.

To explore the effects of tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy on

customer satisfaction in UK fast food restaurants.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Service Quality

Parasuraman et al. (1988, p. 14) defined service quality as “the discrepancy between consumers’

perceptions of services offered by a particular firm and their expectations about firms offering such

services”. Parasuraman et al. (1985) proved that if expectations are higher than performance then

perceived quality is lower than satisfactory and hence customer dissatisfaction happens. Service quality

is also considered to be a perceived attribute based on the experience of the customer regarding the

service that the customer perceived during the delivery process of the service (Zeithaml, Parasuraman,

and Berry, 1990). Delivering quality service means conforming to customer expectations on a consistent

basis (Angelova and Zekiri, 2011). In the specific terms of the fast food restaurant, whenever personal

exchanges occur between a customer and service employees thiscan be considered to be a service

encounter (Bitner et al., 1990). Similarly, Shostack (1985, p. 243) defined a service encounter as “a

period of time during which a consumer directly interacts with a service”. Wilson et al. (2012) proved that

many positive experiences create a composite image of high quality service in the customer’s mind, while

a single negative experience can obliterate a composite image of high quality service.

and increase profits, especially in the UK. This study therefore investigates the impact of service quality

on customer satisfaction in the UK fast food restaurant industry for the purposes of developing

understanding that might help drive such continued growth.

For this study, three leading chains in the UK fast food restaurant industry are taken as subjects:

Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC), McDonald’s and Burger King. The three chains selected for this study

together constitute 50% of the total value in the UK fast food market with McDonald’s the leading brand

with 28,8%, Kentucky Fried Chicken with 12.5% and Burger King with 8.7% (Euromonitor International,

2017). The three restaurants also represent the only significant players in the quick service restaurant

sector nationally and currently operate in a diverse fast food market where there are significant

challenges from Greggs bakery (8.7% of market value), Subway (6.6%), and the casual dining sector

which includes Nando’s (7.7%) (Euromonitor International, 2017). In a competitive environment such as

this, it is important that quick service restaurants are able to understand the determinants of service

quality and customer satisfaction.

Service quality can be seen as one of the key factors affecting customer satisfaction. Due to time and

length restrictions, the research addresses the impact of service quality on customer satisfaction results

of KFC, McDonald’s and Burger King restaurants through the five dimensions of the SERVPERF model,

namely tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance and empathy. The purpose of this study is to

examine relationships between the five dimensions of service quality and customer satisfaction in order to

find out which factors drive customer satisfaction. More importantly, the results of the research will

contribute to the development of service quality as well as of customer satisfaction in fast food companies

in the UK. This study seeks to answer the following questions:

To identify specific service quality dimensions that have an impact on customer satisfaction in the

UK fast food restaurant market.

To explore the effects of tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy on

customer satisfaction in UK fast food restaurants.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Service Quality

Parasuraman et al. (1988, p. 14) defined service quality as “the discrepancy between consumers’

perceptions of services offered by a particular firm and their expectations about firms offering such

services”. Parasuraman et al. (1985) proved that if expectations are higher than performance then

perceived quality is lower than satisfactory and hence customer dissatisfaction happens. Service quality

is also considered to be a perceived attribute based on the experience of the customer regarding the

service that the customer perceived during the delivery process of the service (Zeithaml, Parasuraman,

and Berry, 1990). Delivering quality service means conforming to customer expectations on a consistent

basis (Angelova and Zekiri, 2011). In the specific terms of the fast food restaurant, whenever personal

exchanges occur between a customer and service employees thiscan be considered to be a service

encounter (Bitner et al., 1990). Similarly, Shostack (1985, p. 243) defined a service encounter as “a

period of time during which a consumer directly interacts with a service”. Wilson et al. (2012) proved that

many positive experiences create a composite image of high quality service in the customer’s mind, while

a single negative experience can obliterate a composite image of high quality service.

Measuring Service Quality

Measuring service quality is difficult because the evaluation of service quality is not only based on the

outcome of a service, but this assessment is made during the process of service delivery. Angelova and

Zekiri (2011, p. 246) indicated that “measuring goods quality is easier because it can be measured

objectively with indicators like durability and number of defects, but service quality is an abstract item”.

During the purchase of services, there are some tangible indicators which are usually limited to the

service provider’s facilities, equipment and personnel. If tangible evidence for evaluating quality is absent,

the customer has to base the assessment on other indicators. Overall, the abstract nature of service

quality creates difficulties for organisations in terms of defining variables, making measurements and also

in understanding how consumers ultimately perceive services and service quality. There are, however, a

number of well-established frameworks for analysis of service quality such as the Nordic Model

(Gronroos, 1984), and the SERVQUAL (Parasuraman et al., 1985), SERVPERF (Cronin and Taylor,

1992) and DINESERV (Stevens, Knutson and Patton, 1995) models as detailed below.

Gronroos/Nordic Model

According to Chaipoopirutana (2008), Gronroos (1984, 2007), the initiator of measuring service quality,

used a traditional customer satisfaction/dissatisfaction (CS/D) model to measure and explain service

quality. Based on the work of Gronroos (1984), there are two variables; expected service and perceived

service, both of which play an important role in measuring quality of service. Gronroos (1984) claimed

that the corporate image can be considered a quality dimension and the image is created by technical

and functional quality along with the effects of other factors such as traditional marketing activities

(advertising, pricing, PR), WOM, ideology and tradition (Angelova and Zekiri 2011).

The SERVQUAL Model

Also based on the work of Gronroos (1982, 1984), Parasuraman et al. (1985) developed a conceptual

framework called the gap model, to show causes of service quality shortfalls because they found that

service quality perceptions are the consequence of the comparison of consumer expectations to actual

service performance. Palmer (2011, p.328) suggested that “the GAPS model is an analysis of the causes

of differences between what customers expect and what they get”. There are ten dimensions of service

quality: tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, competence, access, courtesy, communication, credibility,

security and understanding/knowing the customer. However later on the authors reduced the ten

dimensions to five and outlined a scale named SERVQUAL to measure possible gaps (Parasuraman et

al., 1988), listed below:

Tangibles: aspects of physical facilities, equipment and personnel

Reliability: the ability to perform the promised service dependably and accurately

Responsiveness: willingness of the firm to help customers and to perform the service

promptly

Assurance: competence and politeness of the personnel, and the capability to inspire

confidence

Empathy: personalized assistance that the firm conveys to its customers

The SERVPERF model

Based upon various conceptual and operational grounds, many researchers have criticized the limited

effectiveness of the SERVQUAL model as a means of understanding customer satisfaction and loyalty.

Cronin and Taylor (1992) developed an account of how the conceptualization and application of

Measuring service quality is difficult because the evaluation of service quality is not only based on the

outcome of a service, but this assessment is made during the process of service delivery. Angelova and

Zekiri (2011, p. 246) indicated that “measuring goods quality is easier because it can be measured

objectively with indicators like durability and number of defects, but service quality is an abstract item”.

During the purchase of services, there are some tangible indicators which are usually limited to the

service provider’s facilities, equipment and personnel. If tangible evidence for evaluating quality is absent,

the customer has to base the assessment on other indicators. Overall, the abstract nature of service

quality creates difficulties for organisations in terms of defining variables, making measurements and also

in understanding how consumers ultimately perceive services and service quality. There are, however, a

number of well-established frameworks for analysis of service quality such as the Nordic Model

(Gronroos, 1984), and the SERVQUAL (Parasuraman et al., 1985), SERVPERF (Cronin and Taylor,

1992) and DINESERV (Stevens, Knutson and Patton, 1995) models as detailed below.

Gronroos/Nordic Model

According to Chaipoopirutana (2008), Gronroos (1984, 2007), the initiator of measuring service quality,

used a traditional customer satisfaction/dissatisfaction (CS/D) model to measure and explain service

quality. Based on the work of Gronroos (1984), there are two variables; expected service and perceived

service, both of which play an important role in measuring quality of service. Gronroos (1984) claimed

that the corporate image can be considered a quality dimension and the image is created by technical

and functional quality along with the effects of other factors such as traditional marketing activities

(advertising, pricing, PR), WOM, ideology and tradition (Angelova and Zekiri 2011).

The SERVQUAL Model

Also based on the work of Gronroos (1982, 1984), Parasuraman et al. (1985) developed a conceptual

framework called the gap model, to show causes of service quality shortfalls because they found that

service quality perceptions are the consequence of the comparison of consumer expectations to actual

service performance. Palmer (2011, p.328) suggested that “the GAPS model is an analysis of the causes

of differences between what customers expect and what they get”. There are ten dimensions of service

quality: tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, competence, access, courtesy, communication, credibility,

security and understanding/knowing the customer. However later on the authors reduced the ten

dimensions to five and outlined a scale named SERVQUAL to measure possible gaps (Parasuraman et

al., 1988), listed below:

Tangibles: aspects of physical facilities, equipment and personnel

Reliability: the ability to perform the promised service dependably and accurately

Responsiveness: willingness of the firm to help customers and to perform the service

promptly

Assurance: competence and politeness of the personnel, and the capability to inspire

confidence

Empathy: personalized assistance that the firm conveys to its customers

The SERVPERF model

Based upon various conceptual and operational grounds, many researchers have criticized the limited

effectiveness of the SERVQUAL model as a means of understanding customer satisfaction and loyalty.

Cronin and Taylor (1992) developed an account of how the conceptualization and application of

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

SERVQUAL does not address the associations between service quality, customer satisfaction and

purchase intentions. They also discovered that the conceptual basis of the SERVQUAL scale does not

accurately define customer satisfaction in its totality and, as a result, suggested the SERVPERF scale.

Based on the studies of Cronin and Taylor (1992) on dry cleaning, banking, pest control, and fast food

industries, the researchers sought to prove the advantages of their “performance – only” (SERVPERF)

model in practice (Chaipoopirutana, 2008). SERVPERF operationalises only the performance-related

criteria within the SERVQUAL model and effectively eliminates the measures relating to expectation

(Carrilat, Jaramillio and Mulki, 2007). In terms of the fast food restaurant industry, Jain and Gupta (2004)

confirmed that the SERVPERF scale is more successful than the SERVQUAL scale in explaining the

service quality concepts and the distinctions between service quality scores in relation to the model

dimensions. In this paper, the SERVPERF model will be applied to measure the service quality of fast

food restaurants in the UK.

The DINESERV Model

Based on the LODGSERV model, Stevens, Knutson and Patton (1995) built the DINESERV model to

evaluate the expectations of customer of service quality in quick service, casual and fine dining

restaurants. In the original DINESERV model, there were 40 statements about what should occur in a

restaurant and these were developed into 29 items that were measured on a seven-point scale ranging

from “strongly agree” (7) to “strongly disagree” (1) (Hansen, 2014). As a result of the DINESERVE

framework being more directly concerned with restaurant service quality, there is a different emphasis in

the measurements in relation to the original SERVQUAL dimensions that better matches the nature of the

service encounter in this specific sector (Hanks, Line and Kim, 2017; Wu and Mohi, 2015). In particular,

DINESERV pays more attention to the tangible aspects of service quality such as visual attractiveness,

comfort, and cleanliness. Markovic et al. (2010) supported the DINESERV model as a reliable and

relatively simple tool to determine how consumers view a restaurant’s quality and operations and to assist

in finding out where the problems are and how to solve them and a significant body of research has

emerged confirming the validity of the approach (Hanks, Line and Kim, 2017; Kim, Ng and Kim, 2009;

Kuo, Chen and Cheng, 2016; Wu and Mohi, 2015). For the stated reasons above, the items from the

DINESERV model will be tested in this paper.

2.2 Customer Satisfaction

The Concept of Customer Satisfaction

Customer satisfaction deals with known circumstances and known variables. Providing customer delight

is a dynamic, forward-looking process. A satisfied and delighted customer is a potential loyal customer

and a positive word-of-mouth (WOM) (Oliver et al., 1997). On the other hand once customers have been

delighted, their expectation levels are raised (Andaleeb and Conway, 2006), which means that service

providers have to make an extra effort to satisfy these customers. Andaleeb and Conway (2006) indicated

that dissatisfied customers are behind the spreading of negative word-of-mouth. Potential customers are

easily impacted by negative word-of-mouth and they may draw potential customers away from the service

provider (Wilson et al., 2012). With respect to the fast food industry, Khan et al. (2013) pointed out that all

the determinants of customer satisfaction fell into one of seven categories which were physical

environment, service quality, brand, promotion, customer expectations, price and taste of food. Their

results concluded that the main factors for customer satisfaction were service quality and brand.

purchase intentions. They also discovered that the conceptual basis of the SERVQUAL scale does not

accurately define customer satisfaction in its totality and, as a result, suggested the SERVPERF scale.

Based on the studies of Cronin and Taylor (1992) on dry cleaning, banking, pest control, and fast food

industries, the researchers sought to prove the advantages of their “performance – only” (SERVPERF)

model in practice (Chaipoopirutana, 2008). SERVPERF operationalises only the performance-related

criteria within the SERVQUAL model and effectively eliminates the measures relating to expectation

(Carrilat, Jaramillio and Mulki, 2007). In terms of the fast food restaurant industry, Jain and Gupta (2004)

confirmed that the SERVPERF scale is more successful than the SERVQUAL scale in explaining the

service quality concepts and the distinctions between service quality scores in relation to the model

dimensions. In this paper, the SERVPERF model will be applied to measure the service quality of fast

food restaurants in the UK.

The DINESERV Model

Based on the LODGSERV model, Stevens, Knutson and Patton (1995) built the DINESERV model to

evaluate the expectations of customer of service quality in quick service, casual and fine dining

restaurants. In the original DINESERV model, there were 40 statements about what should occur in a

restaurant and these were developed into 29 items that were measured on a seven-point scale ranging

from “strongly agree” (7) to “strongly disagree” (1) (Hansen, 2014). As a result of the DINESERVE

framework being more directly concerned with restaurant service quality, there is a different emphasis in

the measurements in relation to the original SERVQUAL dimensions that better matches the nature of the

service encounter in this specific sector (Hanks, Line and Kim, 2017; Wu and Mohi, 2015). In particular,

DINESERV pays more attention to the tangible aspects of service quality such as visual attractiveness,

comfort, and cleanliness. Markovic et al. (2010) supported the DINESERV model as a reliable and

relatively simple tool to determine how consumers view a restaurant’s quality and operations and to assist

in finding out where the problems are and how to solve them and a significant body of research has

emerged confirming the validity of the approach (Hanks, Line and Kim, 2017; Kim, Ng and Kim, 2009;

Kuo, Chen and Cheng, 2016; Wu and Mohi, 2015). For the stated reasons above, the items from the

DINESERV model will be tested in this paper.

2.2 Customer Satisfaction

The Concept of Customer Satisfaction

Customer satisfaction deals with known circumstances and known variables. Providing customer delight

is a dynamic, forward-looking process. A satisfied and delighted customer is a potential loyal customer

and a positive word-of-mouth (WOM) (Oliver et al., 1997). On the other hand once customers have been

delighted, their expectation levels are raised (Andaleeb and Conway, 2006), which means that service

providers have to make an extra effort to satisfy these customers. Andaleeb and Conway (2006) indicated

that dissatisfied customers are behind the spreading of negative word-of-mouth. Potential customers are

easily impacted by negative word-of-mouth and they may draw potential customers away from the service

provider (Wilson et al., 2012). With respect to the fast food industry, Khan et al. (2013) pointed out that all

the determinants of customer satisfaction fell into one of seven categories which were physical

environment, service quality, brand, promotion, customer expectations, price and taste of food. Their

results concluded that the main factors for customer satisfaction were service quality and brand.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Measurement of Customer Satisfaction

According to Murambi and Bwisa (2014), measuring customer satisfaction can be seen as an effort to

measure human feelings, and it is therefore very difficult at times for many researchers to do so. It is

important to note that “measuring customer satisfaction provides an indication on how an organization is

performing or providing products or services” Manani et al. (2013, p. 192). Specifically, the NBRI (2015)

proposed possible dimensions that one can use in measuring customer such as: pricing, quality of

service, speed of service, trust in employees, types of other services needed, complaints, positioning in

clients’ minds, and the closeness of the relationship between the customers and the firm.

According to Boulding et al. (1993), there were two conceptualisations of customer satisfaction,

transaction specific satisfaction and cumulative satisfaction. In the transaction specific approach

considers customer satisfaction as a post-choice evaluation judgment of a specific service encounter

(Oliver, 1993). Fornell (1992) pointed out that cumulative customer satisfaction is seen as an overall

evaluation that depends on the total purchase and consumption experience with a product or service over

time. According to Wilson et al. (2012) transaction specific satisfaction provides essential data for

identifying service issues and making immediate changes to improve customer satisfaction. They also

proposed that cumulative customer satisfaction is important in predicting, customer loyalty and motivating

a company’s investment in customer satisfaction.

2.3 Relationship between Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction

The works of Cronin and Taylor (1992) and Oliver (1993) revealed that while the concepts of service

quality and customer satisfaction are distinct, there is a close relationship between them. Parasuraman

et al. (1988) differentiated that while customer satisfaction is related to a specific transaction, perceived

service quality is a global judgment or attitude relating to the superiority of service. Sureshchandar et al.

(2002, p. 372) attested that “there exists a great dependency between service quality and customer

satisfaction, and an increase in one is likely lead to an increase in another”. In the works of Brady and

Robertson (2001) on fast food restaurants in America and Latin America, they found that service quality

and customer satisfaction were very closely related. Gronroos (2007) indicated that a perception of

service quality comes first, followed by a perception of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with this quality.

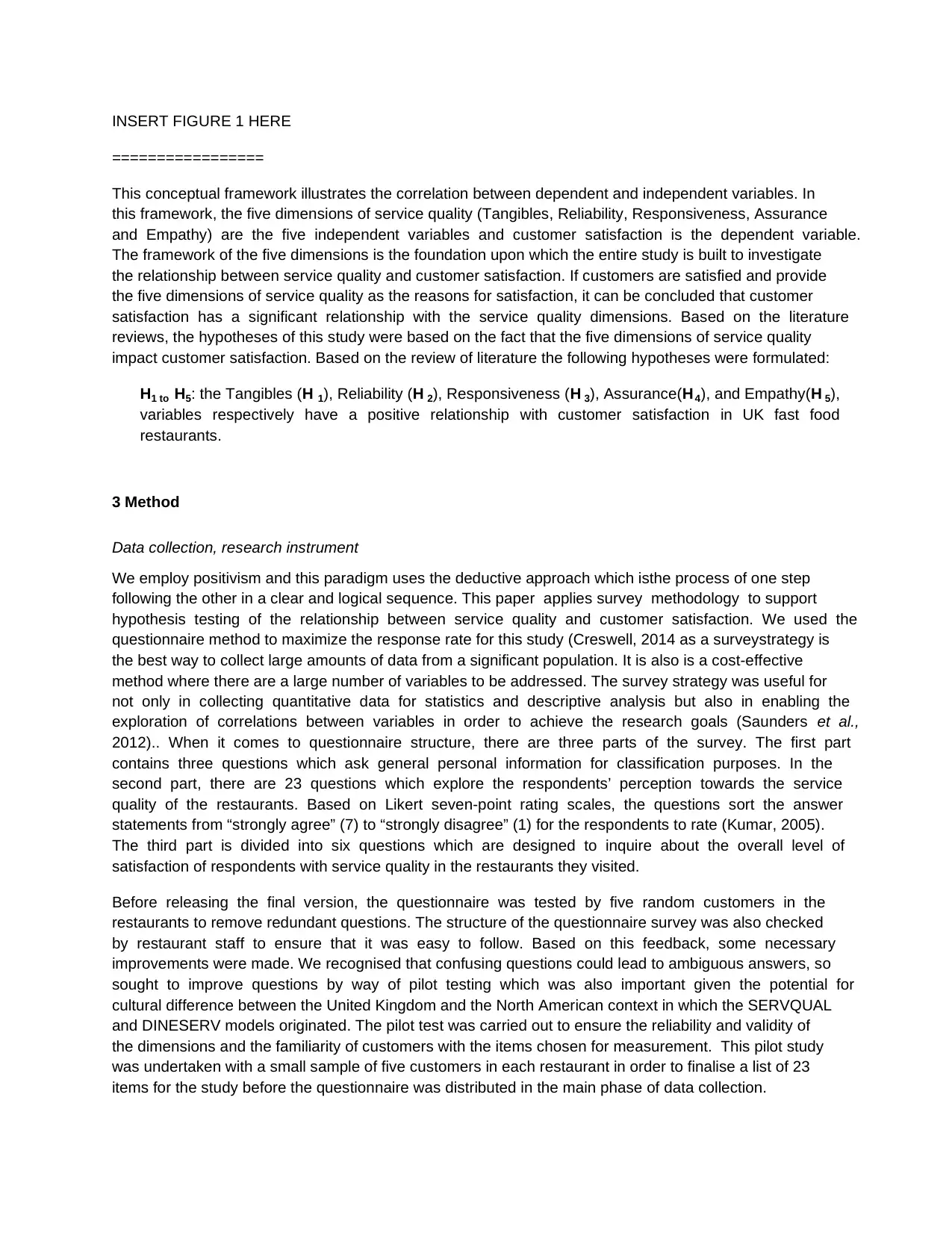

Based on the paradigm of Wilson et al. (2012), figure 1 illustrates the relationship between service quality

and customer satisfaction. In terms of the fast food industry, according to Heung et al., 2000, Jain and

Gupta (2004), Qin and Prybutok (2009), and Khan et al. (2013), price, product quality and service quality

relate directly to customer satisfaction; however, comparing product quality and price, the perceived

service quality factor plays the most important role on overall satisfaction.

2.4 Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

In terms of the fast food restaurant industry, Jain and Gupta (2004) stated that the SERVPERF model is a

very popular model to measure service quality globally. The efficiency of the SERVPERF model was also

tested by many researchers such as Cronin and Taylor (1992), Jain and Gupta (2004), Qin et al. (2010)

and Khan et al. (2013). Due to its popularity, the SERVPERF scale is applied to measure the perceived

service quality of UK fast food restaurants in this study. There are five dimensions (Tangibles, Reliability,

Responsiveness, Assurance and Empathy) used to measure the service quality in the study. Based on

the DINESERV model of Steven, Knutson and Patton (1995), and the SERVPERF model of Cronin and

Taylor (1992), 23 items were tested corresponding to the five above mentioned dimensions.

================

According to Murambi and Bwisa (2014), measuring customer satisfaction can be seen as an effort to

measure human feelings, and it is therefore very difficult at times for many researchers to do so. It is

important to note that “measuring customer satisfaction provides an indication on how an organization is

performing or providing products or services” Manani et al. (2013, p. 192). Specifically, the NBRI (2015)

proposed possible dimensions that one can use in measuring customer such as: pricing, quality of

service, speed of service, trust in employees, types of other services needed, complaints, positioning in

clients’ minds, and the closeness of the relationship between the customers and the firm.

According to Boulding et al. (1993), there were two conceptualisations of customer satisfaction,

transaction specific satisfaction and cumulative satisfaction. In the transaction specific approach

considers customer satisfaction as a post-choice evaluation judgment of a specific service encounter

(Oliver, 1993). Fornell (1992) pointed out that cumulative customer satisfaction is seen as an overall

evaluation that depends on the total purchase and consumption experience with a product or service over

time. According to Wilson et al. (2012) transaction specific satisfaction provides essential data for

identifying service issues and making immediate changes to improve customer satisfaction. They also

proposed that cumulative customer satisfaction is important in predicting, customer loyalty and motivating

a company’s investment in customer satisfaction.

2.3 Relationship between Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction

The works of Cronin and Taylor (1992) and Oliver (1993) revealed that while the concepts of service

quality and customer satisfaction are distinct, there is a close relationship between them. Parasuraman

et al. (1988) differentiated that while customer satisfaction is related to a specific transaction, perceived

service quality is a global judgment or attitude relating to the superiority of service. Sureshchandar et al.

(2002, p. 372) attested that “there exists a great dependency between service quality and customer

satisfaction, and an increase in one is likely lead to an increase in another”. In the works of Brady and

Robertson (2001) on fast food restaurants in America and Latin America, they found that service quality

and customer satisfaction were very closely related. Gronroos (2007) indicated that a perception of

service quality comes first, followed by a perception of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with this quality.

Based on the paradigm of Wilson et al. (2012), figure 1 illustrates the relationship between service quality

and customer satisfaction. In terms of the fast food industry, according to Heung et al., 2000, Jain and

Gupta (2004), Qin and Prybutok (2009), and Khan et al. (2013), price, product quality and service quality

relate directly to customer satisfaction; however, comparing product quality and price, the perceived

service quality factor plays the most important role on overall satisfaction.

2.4 Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

In terms of the fast food restaurant industry, Jain and Gupta (2004) stated that the SERVPERF model is a

very popular model to measure service quality globally. The efficiency of the SERVPERF model was also

tested by many researchers such as Cronin and Taylor (1992), Jain and Gupta (2004), Qin et al. (2010)

and Khan et al. (2013). Due to its popularity, the SERVPERF scale is applied to measure the perceived

service quality of UK fast food restaurants in this study. There are five dimensions (Tangibles, Reliability,

Responsiveness, Assurance and Empathy) used to measure the service quality in the study. Based on

the DINESERV model of Steven, Knutson and Patton (1995), and the SERVPERF model of Cronin and

Taylor (1992), 23 items were tested corresponding to the five above mentioned dimensions.

================

INSERT FIGURE 1 HERE

=================

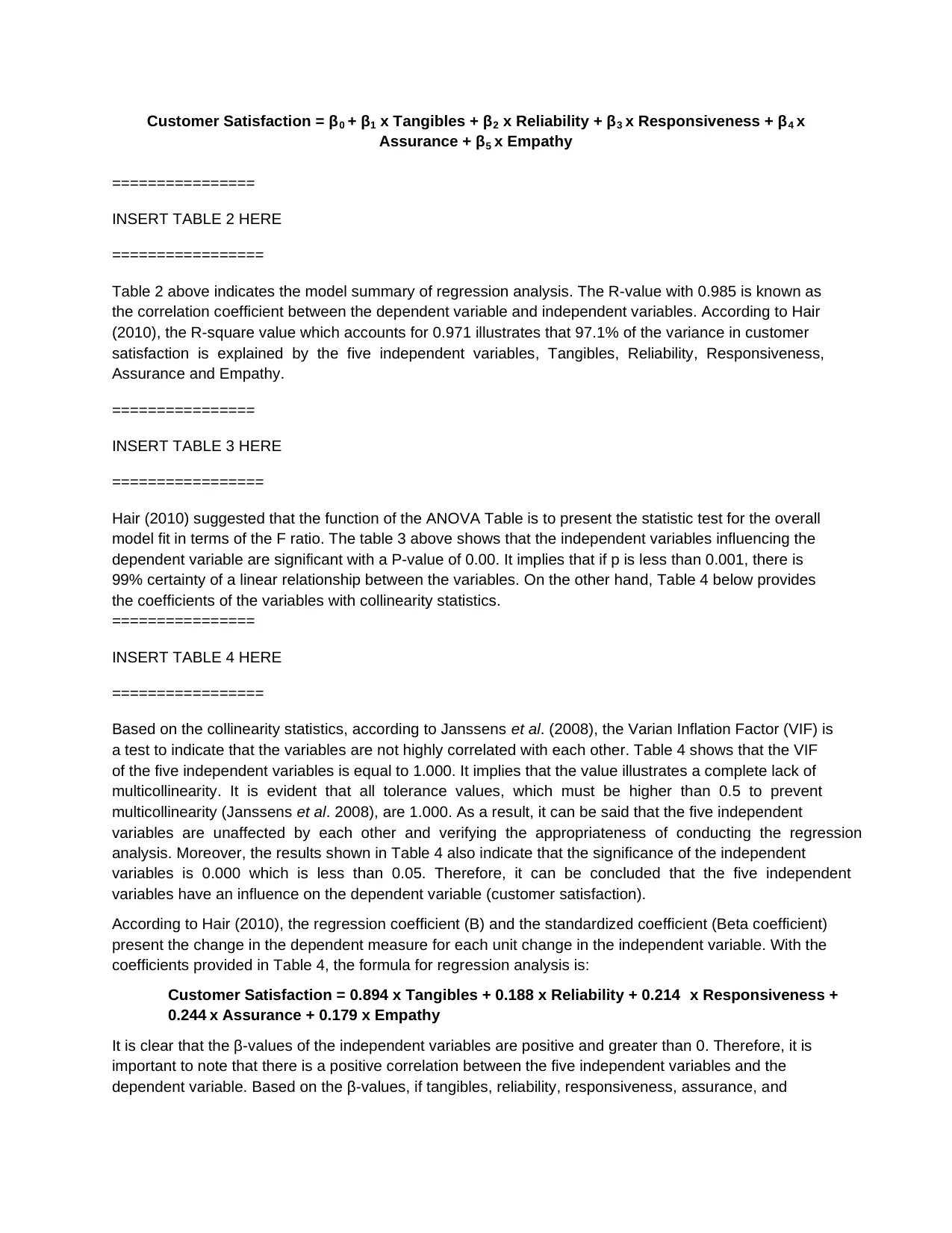

This conceptual framework illustrates the correlation between dependent and independent variables. In

this framework, the five dimensions of service quality (Tangibles, Reliability, Responsiveness, Assurance

and Empathy) are the five independent variables and customer satisfaction is the dependent variable.

The framework of the five dimensions is the foundation upon which the entire study is built to investigate

the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction. If customers are satisfied and provide

the five dimensions of service quality as the reasons for satisfaction, it can be concluded that customer

satisfaction has a significant relationship with the service quality dimensions. Based on the literature

reviews, the hypotheses of this study were based on the fact that the five dimensions of service quality

impact customer satisfaction. Based on the review of literature the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1 to H5: the Tangibles (H 1), Reliability (H 2), Responsiveness (H 3), Assurance(H4), and Empathy(H 5),

variables respectively have a positive relationship with customer satisfaction in UK fast food

restaurants.

3 Method

Data collection, research instrument

We employ positivism and this paradigm uses the deductive approach which isthe process of one step

following the other in a clear and logical sequence. This paper applies survey methodology to support

hypothesis testing of the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction. We used the

questionnaire method to maximize the response rate for this study (Creswell, 2014 as a surveystrategy is

the best way to collect large amounts of data from a significant population. It is also is a cost-effective

method where there are a large number of variables to be addressed. The survey strategy was useful for

not only in collecting quantitative data for statistics and descriptive analysis but also in enabling the

exploration of correlations between variables in order to achieve the research goals (Saunders et al.,

2012).. When it comes to questionnaire structure, there are three parts of the survey. The first part

contains three questions which ask general personal information for classification purposes. In the

second part, there are 23 questions which explore the respondents’ perception towards the service

quality of the restaurants. Based on Likert seven-point rating scales, the questions sort the answer

statements from “strongly agree” (7) to “strongly disagree” (1) for the respondents to rate (Kumar, 2005).

The third part is divided into six questions which are designed to inquire about the overall level of

satisfaction of respondents with service quality in the restaurants they visited.

Before releasing the final version, the questionnaire was tested by five random customers in the

restaurants to remove redundant questions. The structure of the questionnaire survey was also checked

by restaurant staff to ensure that it was easy to follow. Based on this feedback, some necessary

improvements were made. We recognised that confusing questions could lead to ambiguous answers, so

sought to improve questions by way of pilot testing which was also important given the potential for

cultural difference between the United Kingdom and the North American context in which the SERVQUAL

and DINESERV models originated. The pilot test was carried out to ensure the reliability and validity of

the dimensions and the familiarity of customers with the items chosen for measurement. This pilot study

was undertaken with a small sample of five customers in each restaurant in order to finalise a list of 23

items for the study before the questionnaire was distributed in the main phase of data collection.

=================

This conceptual framework illustrates the correlation between dependent and independent variables. In

this framework, the five dimensions of service quality (Tangibles, Reliability, Responsiveness, Assurance

and Empathy) are the five independent variables and customer satisfaction is the dependent variable.

The framework of the five dimensions is the foundation upon which the entire study is built to investigate

the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction. If customers are satisfied and provide

the five dimensions of service quality as the reasons for satisfaction, it can be concluded that customer

satisfaction has a significant relationship with the service quality dimensions. Based on the literature

reviews, the hypotheses of this study were based on the fact that the five dimensions of service quality

impact customer satisfaction. Based on the review of literature the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1 to H5: the Tangibles (H 1), Reliability (H 2), Responsiveness (H 3), Assurance(H4), and Empathy(H 5),

variables respectively have a positive relationship with customer satisfaction in UK fast food

restaurants.

3 Method

Data collection, research instrument

We employ positivism and this paradigm uses the deductive approach which isthe process of one step

following the other in a clear and logical sequence. This paper applies survey methodology to support

hypothesis testing of the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction. We used the

questionnaire method to maximize the response rate for this study (Creswell, 2014 as a surveystrategy is

the best way to collect large amounts of data from a significant population. It is also is a cost-effective

method where there are a large number of variables to be addressed. The survey strategy was useful for

not only in collecting quantitative data for statistics and descriptive analysis but also in enabling the

exploration of correlations between variables in order to achieve the research goals (Saunders et al.,

2012).. When it comes to questionnaire structure, there are three parts of the survey. The first part

contains three questions which ask general personal information for classification purposes. In the

second part, there are 23 questions which explore the respondents’ perception towards the service

quality of the restaurants. Based on Likert seven-point rating scales, the questions sort the answer

statements from “strongly agree” (7) to “strongly disagree” (1) for the respondents to rate (Kumar, 2005).

The third part is divided into six questions which are designed to inquire about the overall level of

satisfaction of respondents with service quality in the restaurants they visited.

Before releasing the final version, the questionnaire was tested by five random customers in the

restaurants to remove redundant questions. The structure of the questionnaire survey was also checked

by restaurant staff to ensure that it was easy to follow. Based on this feedback, some necessary

improvements were made. We recognised that confusing questions could lead to ambiguous answers, so

sought to improve questions by way of pilot testing which was also important given the potential for

cultural difference between the United Kingdom and the North American context in which the SERVQUAL

and DINESERV models originated. The pilot test was carried out to ensure the reliability and validity of

the dimensions and the familiarity of customers with the items chosen for measurement. This pilot study

was undertaken with a small sample of five customers in each restaurant in order to finalise a list of 23

items for the study before the questionnaire was distributed in the main phase of data collection.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

147 questionnaire responses were collected from the customers at two KFC restaurants, two McDonald’s

restaurants, and one Burger King Restaurant in the city of Bristol, in the south-west of England, in the

United Kingdom. An average of 30 questionnaires were used at each of the five restaurants using a

random sampling technique whereby every fifth customer was approached for participation during periods

of field-working. Data collection was undertaken at predetermined times which were related to periods of

peak and lower demand in order to maximise the number of responses at the same time as ensuring that

any variation in the customers using the restaurants at different times of day was also captured. A total of

4-5 hours was spent in each restaurant. Respondents were invited to answer the questionnaire after they

finished their meals so that they had more “neutral” time for responding to prevent threats to reliability.

For convenience, the respondents were invited to complete the questionnaire on tablets so thatthe data

were immediately saved at the time of collection. Data collection was conducted based on the voluntary

and anonymised submissions of the respondents, ensuring ethical practice.

Data was analysed using SPSS software. Chatterjee and Hadi (2006) defined regression analysis as an

analytical method that examines the possible functional relationship which may exist among different

variables at a given point in time. For these reasons, this research applies multiple regression analysis to

examine the proposed hypotheses on the constructs of the five service quality dimensions (Tangibles,

Reliability, Responsiveness, Assurance, and Empathy) and customer satisfaction. It is important to note

that the outcomes of regression analysis will indicate what factors impact customer satisfaction and which

have the most influence on customer satisfaction.

The following 23 items were incorporated in relation to each of the five dimensions of service quality

(adopted from Cronin and Taylor, 1992; Steven, Knutson and Patton, 1995; Qin and Prybutok, 2009; Qin

et al., 2010) for the purposes of this study:

Tangibles: (1) Parking availability; (2) seating availability; (3) clean and comfortable dining areas; (4)

well-dressed staff members; (5) easily readable menu; (6) clean restrooms; (7) adequate availability of

sauces, salt, napkins, wet-naps, and cutlery.

Reliability: (8) The speed of service is as fast as promised; (9) dependability and consistency; (10) quick

corrections to anything that is wrong; (11) accurate billing; (12) accuracy of customer’s order.

Responsiveness: (13) During the rush hours extra employees are provided to help maintain speed and

quality of service; (14) prompt and quick service; (15) employees willing to help and handle customers’

special requests.

Assurance: (16) Customers feel comfortable and confident in dealing with establishment; (17) feel safe

for financial transactions; (18) employees are consistently courteous; (19) employees have knowledge to

answer customer questions.

Empathy: (20) Employees are sensitive and anticipate individual customer needs and wants rather than

always relying on policies and procedures; (21) ability to make customers feel special; (22) employees

are sympathetic and reassuring if something is wrong; (23) customers’ best interests are at heart.

4 Results

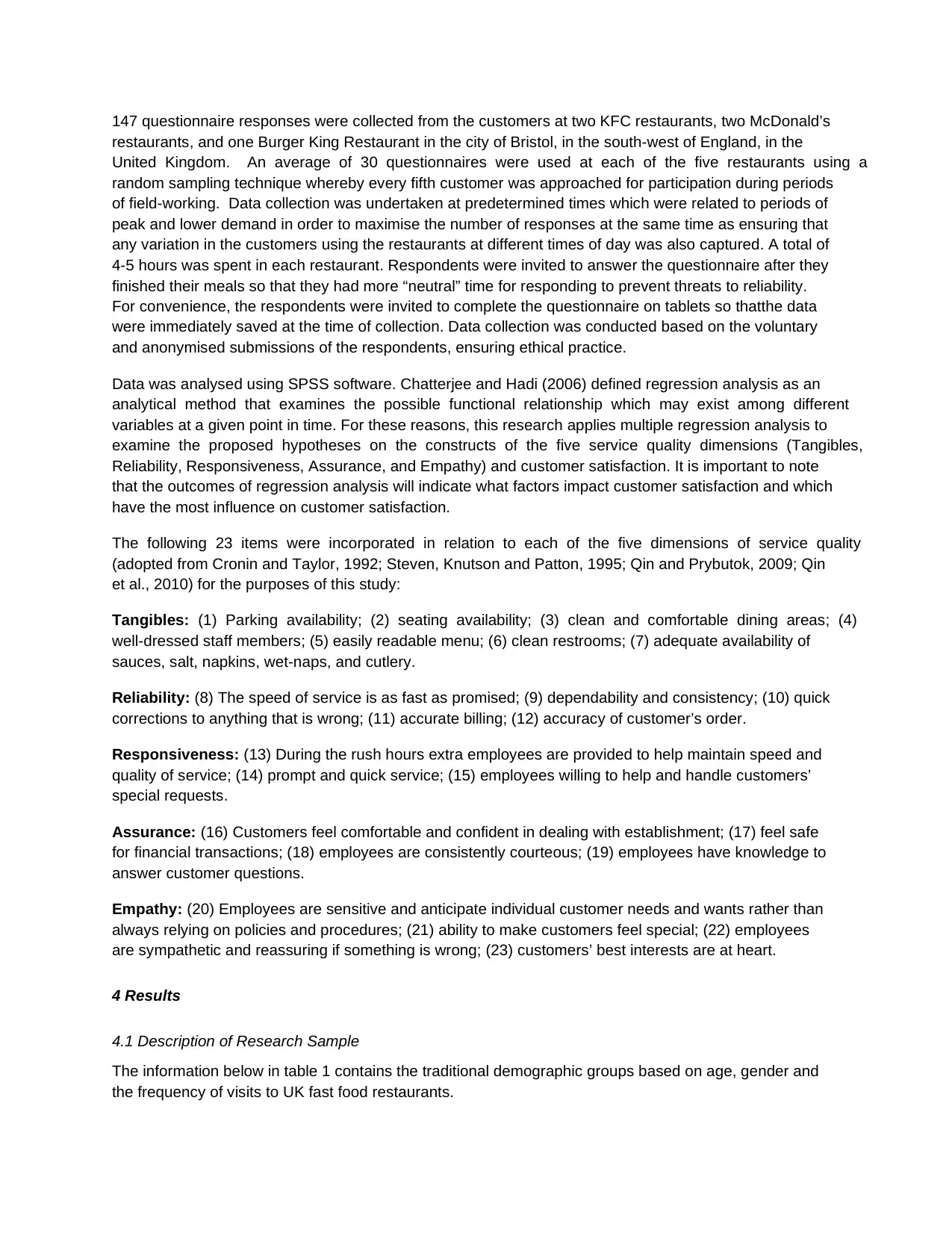

4.1 Description of Research Sample

The information below in table 1 contains the traditional demographic groups based on age, gender and

the frequency of visits to UK fast food restaurants.

restaurants, and one Burger King Restaurant in the city of Bristol, in the south-west of England, in the

United Kingdom. An average of 30 questionnaires were used at each of the five restaurants using a

random sampling technique whereby every fifth customer was approached for participation during periods

of field-working. Data collection was undertaken at predetermined times which were related to periods of

peak and lower demand in order to maximise the number of responses at the same time as ensuring that

any variation in the customers using the restaurants at different times of day was also captured. A total of

4-5 hours was spent in each restaurant. Respondents were invited to answer the questionnaire after they

finished their meals so that they had more “neutral” time for responding to prevent threats to reliability.

For convenience, the respondents were invited to complete the questionnaire on tablets so thatthe data

were immediately saved at the time of collection. Data collection was conducted based on the voluntary

and anonymised submissions of the respondents, ensuring ethical practice.

Data was analysed using SPSS software. Chatterjee and Hadi (2006) defined regression analysis as an

analytical method that examines the possible functional relationship which may exist among different

variables at a given point in time. For these reasons, this research applies multiple regression analysis to

examine the proposed hypotheses on the constructs of the five service quality dimensions (Tangibles,

Reliability, Responsiveness, Assurance, and Empathy) and customer satisfaction. It is important to note

that the outcomes of regression analysis will indicate what factors impact customer satisfaction and which

have the most influence on customer satisfaction.

The following 23 items were incorporated in relation to each of the five dimensions of service quality

(adopted from Cronin and Taylor, 1992; Steven, Knutson and Patton, 1995; Qin and Prybutok, 2009; Qin

et al., 2010) for the purposes of this study:

Tangibles: (1) Parking availability; (2) seating availability; (3) clean and comfortable dining areas; (4)

well-dressed staff members; (5) easily readable menu; (6) clean restrooms; (7) adequate availability of

sauces, salt, napkins, wet-naps, and cutlery.

Reliability: (8) The speed of service is as fast as promised; (9) dependability and consistency; (10) quick

corrections to anything that is wrong; (11) accurate billing; (12) accuracy of customer’s order.

Responsiveness: (13) During the rush hours extra employees are provided to help maintain speed and

quality of service; (14) prompt and quick service; (15) employees willing to help and handle customers’

special requests.

Assurance: (16) Customers feel comfortable and confident in dealing with establishment; (17) feel safe

for financial transactions; (18) employees are consistently courteous; (19) employees have knowledge to

answer customer questions.

Empathy: (20) Employees are sensitive and anticipate individual customer needs and wants rather than

always relying on policies and procedures; (21) ability to make customers feel special; (22) employees

are sympathetic and reassuring if something is wrong; (23) customers’ best interests are at heart.

4 Results

4.1 Description of Research Sample

The information below in table 1 contains the traditional demographic groups based on age, gender and

the frequency of visits to UK fast food restaurants.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

================

INSERT TABLE 1 HERE

=================

4.2 Measurement Assessment

Reliability

According to Hair et al. (1995), if Cronbach’s alpha is over 0.7 in general and over 0.5 for the item-total

correlation; it means the survey questions in scale are reliable and connective. Cronbach’s alpha

coefficients of Tangibles, Reliability, Responsiveness, Assurance, and Empathy are 0.925, 0.828, 0.846,

0.932, and 0.836, respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the five variables are over 0.8 and

much higher than 0.7, so they exceed the suggested criterion. Furthermore, all the variables’ item-total

correlations are over 0.5, with the lowest being 0.520 and the highest being 0.921. Thus, it is clear that

the variables meet all requirements of reliability for analysis.

4.3 Factor Analysis

KMO and Bartlett’s Test

Factor analysis is generally employed to clarify the underlying structure among the variables in the

analysis. Scale reliability for variables and group of variables has indicated the suitability of the data

collected for structure detection. In other words, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Barlett’s test measure

the sampling adequacy which should be higher than 0.5 for a satisfactory factor analysis to progress.

SPSS results indicate the KMO is 0.859 which is much greater than 0.5. As a result, it indicates that

factor analysis is relevant for this research. According to Malhotra and Birks (2007), a factor analysis is

only significant when the variables concerned are suitably correlated to one another. According to Burns

and Burns (2008), this result implies that the variables are related.

Individual observed response is supported by underlying common factors. The loading factor is based on

the weights and the correlation between each variable and the factor. According to Daniel and Berinyuy

(2010), the higher the number, the more important the variable is in defining the factor’s dimensionality. In

contrast, if the value is negative, it means that there is an opposite influence between the variable and the

factor. It is clear that all variables have practically significant loading on every certain factor so there are

no eliminated variables on the table. The individual variables, which are greater than 0.5, are chosen for

the specific factors. Finally, the five factors are generated from 23 individual variables and labelled as five

major dimensions of service quality.

4.4 Regression Analysis

As discussed in the literature review, it is assumed that there is a relationship between the five

dimensions of service quality (tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance and empathy) and

customer satisfaction in UK fast food restaurants. In this part, the regression analysis will be conducted to

examine the rate of significance in the relationship between the independent variables, Tangibles,

Reliability, Responsiveness, Assurance and Empathy and the dependent variable (customer satisfaction).

The formula for regression analysis is as follows:

INSERT TABLE 1 HERE

=================

4.2 Measurement Assessment

Reliability

According to Hair et al. (1995), if Cronbach’s alpha is over 0.7 in general and over 0.5 for the item-total

correlation; it means the survey questions in scale are reliable and connective. Cronbach’s alpha

coefficients of Tangibles, Reliability, Responsiveness, Assurance, and Empathy are 0.925, 0.828, 0.846,

0.932, and 0.836, respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the five variables are over 0.8 and

much higher than 0.7, so they exceed the suggested criterion. Furthermore, all the variables’ item-total

correlations are over 0.5, with the lowest being 0.520 and the highest being 0.921. Thus, it is clear that

the variables meet all requirements of reliability for analysis.

4.3 Factor Analysis

KMO and Bartlett’s Test

Factor analysis is generally employed to clarify the underlying structure among the variables in the

analysis. Scale reliability for variables and group of variables has indicated the suitability of the data

collected for structure detection. In other words, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Barlett’s test measure

the sampling adequacy which should be higher than 0.5 for a satisfactory factor analysis to progress.

SPSS results indicate the KMO is 0.859 which is much greater than 0.5. As a result, it indicates that

factor analysis is relevant for this research. According to Malhotra and Birks (2007), a factor analysis is

only significant when the variables concerned are suitably correlated to one another. According to Burns

and Burns (2008), this result implies that the variables are related.

Individual observed response is supported by underlying common factors. The loading factor is based on

the weights and the correlation between each variable and the factor. According to Daniel and Berinyuy

(2010), the higher the number, the more important the variable is in defining the factor’s dimensionality. In

contrast, if the value is negative, it means that there is an opposite influence between the variable and the

factor. It is clear that all variables have practically significant loading on every certain factor so there are

no eliminated variables on the table. The individual variables, which are greater than 0.5, are chosen for

the specific factors. Finally, the five factors are generated from 23 individual variables and labelled as five

major dimensions of service quality.

4.4 Regression Analysis

As discussed in the literature review, it is assumed that there is a relationship between the five

dimensions of service quality (tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance and empathy) and

customer satisfaction in UK fast food restaurants. In this part, the regression analysis will be conducted to

examine the rate of significance in the relationship between the independent variables, Tangibles,

Reliability, Responsiveness, Assurance and Empathy and the dependent variable (customer satisfaction).

The formula for regression analysis is as follows:

Customer Satisfaction = β0 + β1 x Tangibles + β2 x Reliability + β3 x Responsiveness + β4 x

Assurance + β5 x Empathy

================

INSERT TABLE 2 HERE

=================

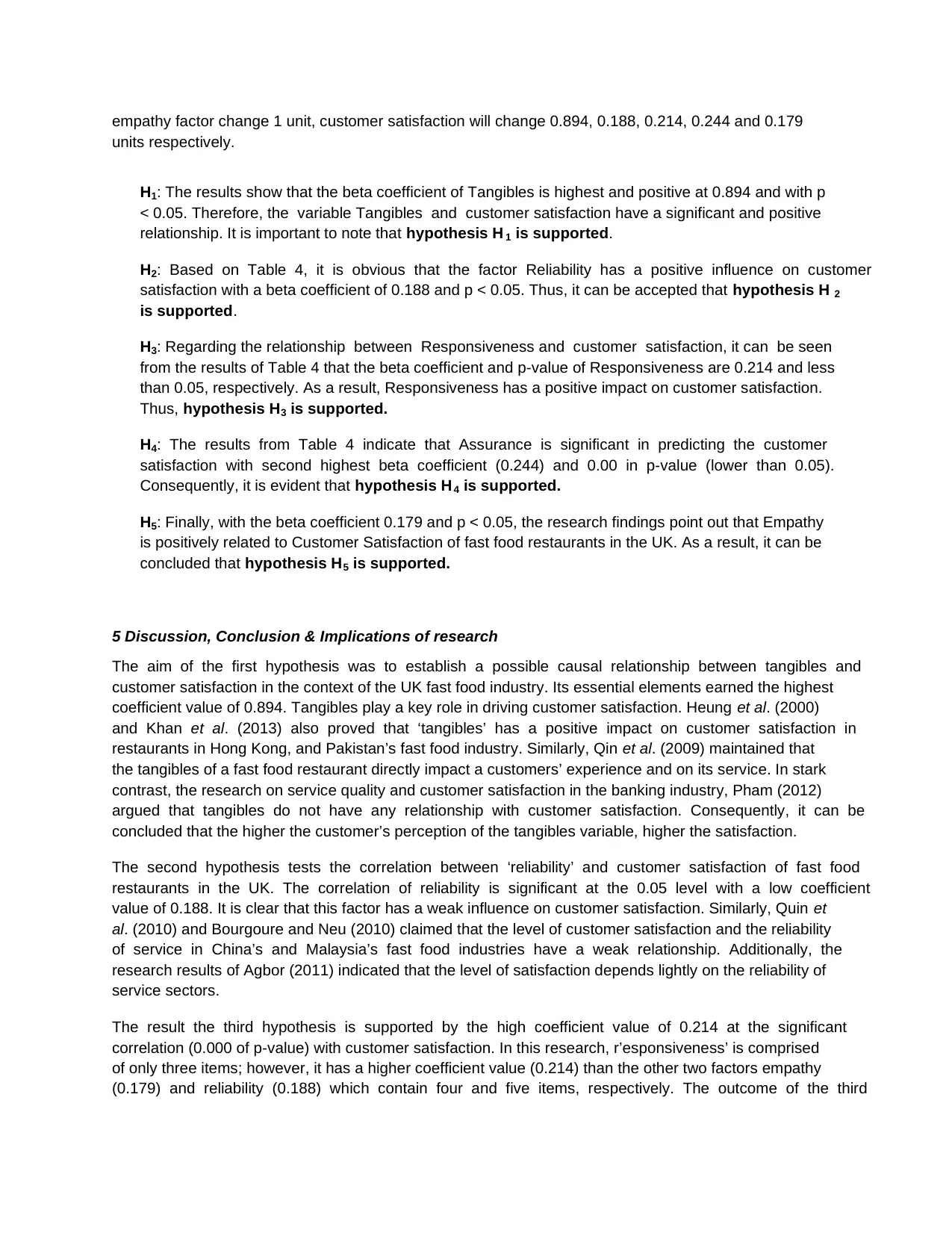

Table 2 above indicates the model summary of regression analysis. The R-value with 0.985 is known as

the correlation coefficient between the dependent variable and independent variables. According to Hair

(2010), the R-square value which accounts for 0.971 illustrates that 97.1% of the variance in customer

satisfaction is explained by the five independent variables, Tangibles, Reliability, Responsiveness,

Assurance and Empathy.

================

INSERT TABLE 3 HERE

=================

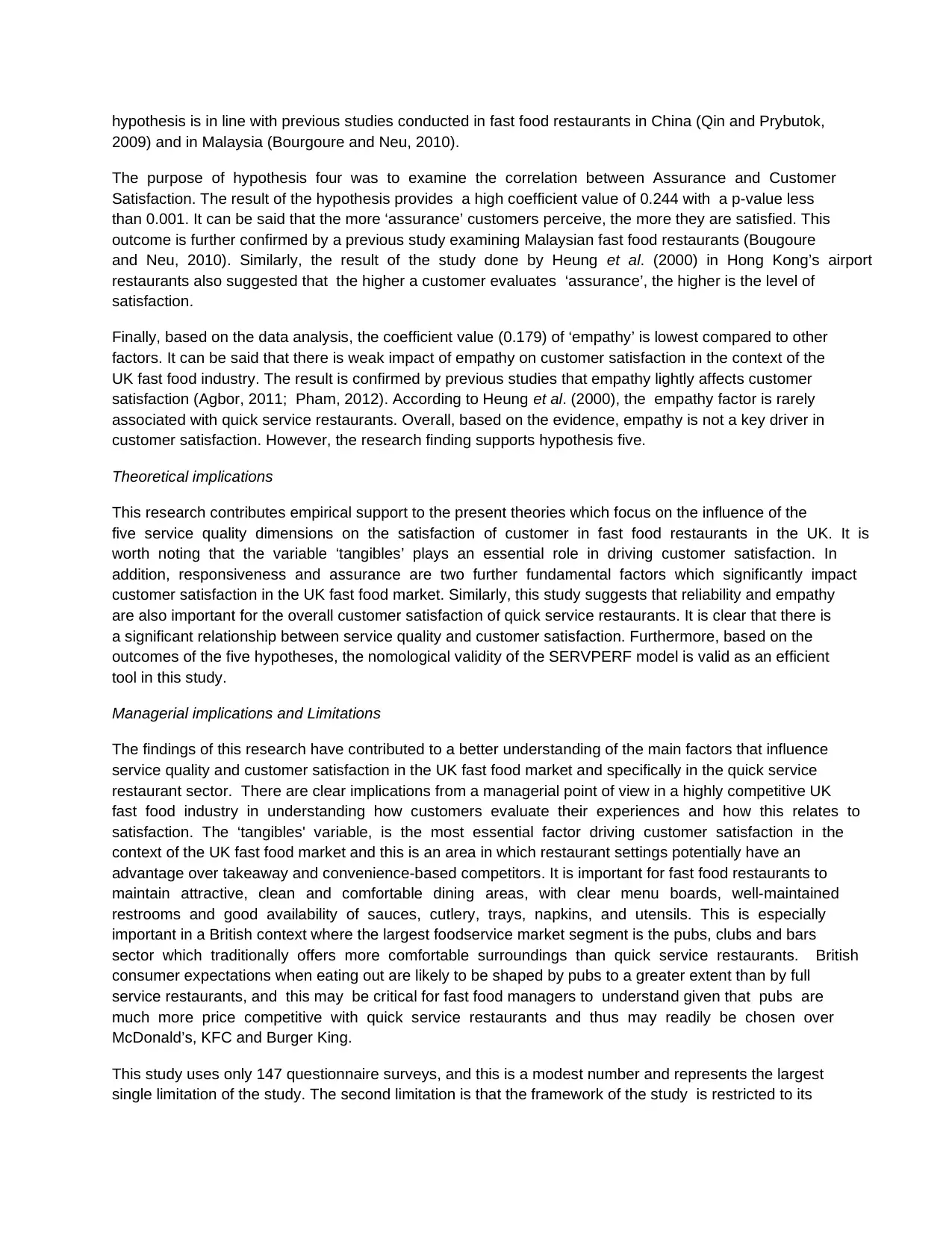

Hair (2010) suggested that the function of the ANOVA Table is to present the statistic test for the overall

model fit in terms of the F ratio. The table 3 above shows that the independent variables influencing the

dependent variable are significant with a P-value of 0.00. It implies that if p is less than 0.001, there is

99% certainty of a linear relationship between the variables. On the other hand, Table 4 below provides

the coefficients of the variables with collinearity statistics.

================

INSERT TABLE 4 HERE

=================

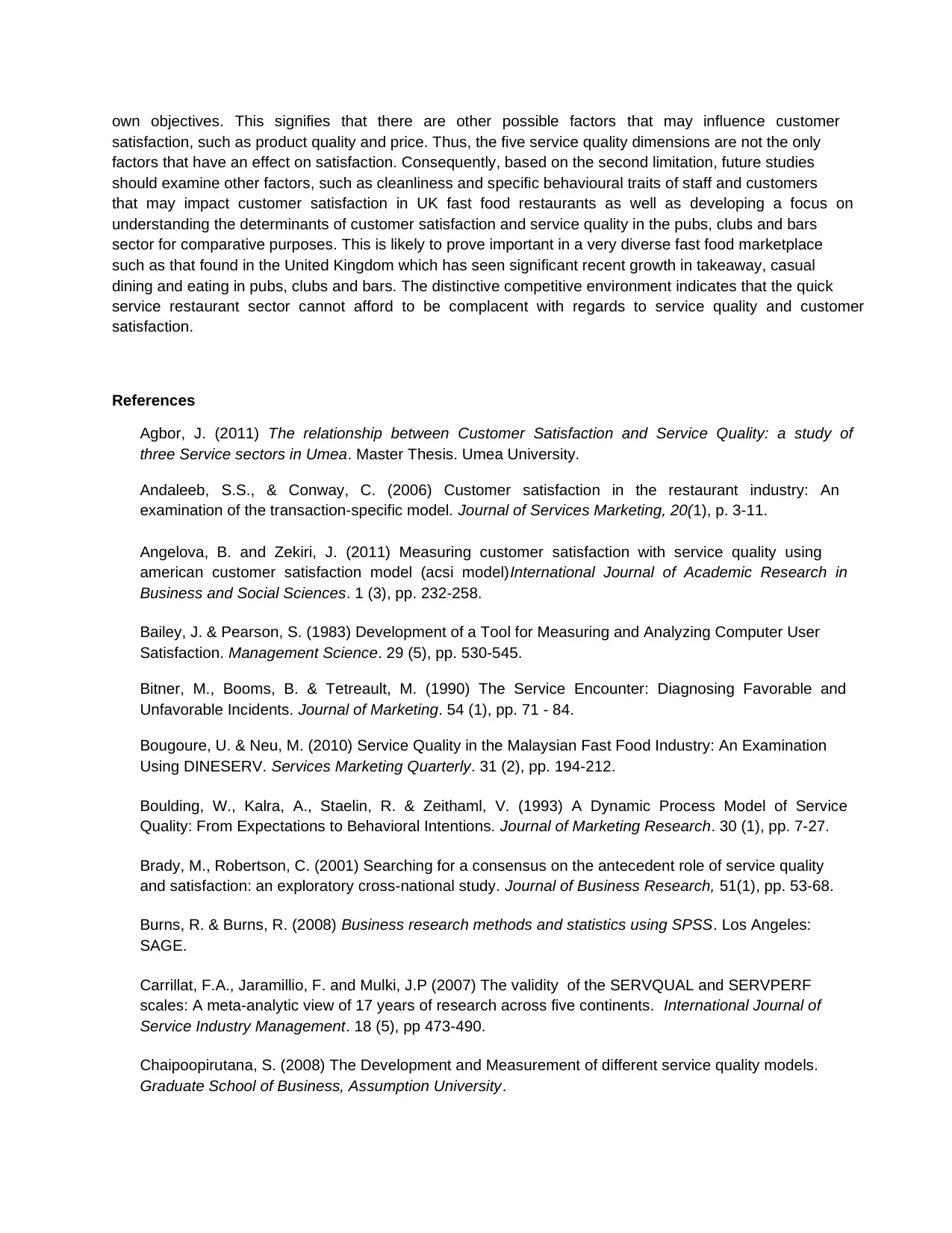

Based on the collinearity statistics, according to Janssens et al. (2008), the Varian Inflation Factor (VIF) is

a test to indicate that the variables are not highly correlated with each other. Table 4 shows that the VIF

of the five independent variables is equal to 1.000. It implies that the value illustrates a complete lack of

multicollinearity. It is evident that all tolerance values, which must be higher than 0.5 to prevent

multicollinearity (Janssens et al. 2008), are 1.000. As a result, it can be said that the five independent

variables are unaffected by each other and verifying the appropriateness of conducting the regression

analysis. Moreover, the results shown in Table 4 also indicate that the significance of the independent

variables is 0.000 which is less than 0.05. Therefore, it can be concluded that the five independent

variables have an influence on the dependent variable (customer satisfaction).

According to Hair (2010), the regression coefficient (B) and the standardized coefficient (Beta coefficient)

present the change in the dependent measure for each unit change in the independent variable. With the

coefficients provided in Table 4, the formula for regression analysis is:

Customer Satisfaction = 0.894 x Tangibles + 0.188 x Reliability + 0.214 x Responsiveness +

0.244 x Assurance + 0.179 x Empathy

It is clear that the β-values of the independent variables are positive and greater than 0. Therefore, it is

important to note that there is a positive correlation between the five independent variables and the

dependent variable. Based on the β-values, if tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and

Assurance + β5 x Empathy

================

INSERT TABLE 2 HERE

=================

Table 2 above indicates the model summary of regression analysis. The R-value with 0.985 is known as

the correlation coefficient between the dependent variable and independent variables. According to Hair

(2010), the R-square value which accounts for 0.971 illustrates that 97.1% of the variance in customer

satisfaction is explained by the five independent variables, Tangibles, Reliability, Responsiveness,

Assurance and Empathy.

================

INSERT TABLE 3 HERE

=================

Hair (2010) suggested that the function of the ANOVA Table is to present the statistic test for the overall

model fit in terms of the F ratio. The table 3 above shows that the independent variables influencing the

dependent variable are significant with a P-value of 0.00. It implies that if p is less than 0.001, there is

99% certainty of a linear relationship between the variables. On the other hand, Table 4 below provides

the coefficients of the variables with collinearity statistics.

================

INSERT TABLE 4 HERE

=================

Based on the collinearity statistics, according to Janssens et al. (2008), the Varian Inflation Factor (VIF) is

a test to indicate that the variables are not highly correlated with each other. Table 4 shows that the VIF

of the five independent variables is equal to 1.000. It implies that the value illustrates a complete lack of

multicollinearity. It is evident that all tolerance values, which must be higher than 0.5 to prevent

multicollinearity (Janssens et al. 2008), are 1.000. As a result, it can be said that the five independent

variables are unaffected by each other and verifying the appropriateness of conducting the regression

analysis. Moreover, the results shown in Table 4 also indicate that the significance of the independent

variables is 0.000 which is less than 0.05. Therefore, it can be concluded that the five independent

variables have an influence on the dependent variable (customer satisfaction).

According to Hair (2010), the regression coefficient (B) and the standardized coefficient (Beta coefficient)

present the change in the dependent measure for each unit change in the independent variable. With the

coefficients provided in Table 4, the formula for regression analysis is:

Customer Satisfaction = 0.894 x Tangibles + 0.188 x Reliability + 0.214 x Responsiveness +

0.244 x Assurance + 0.179 x Empathy

It is clear that the β-values of the independent variables are positive and greater than 0. Therefore, it is

important to note that there is a positive correlation between the five independent variables and the

dependent variable. Based on the β-values, if tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

empathy factor change 1 unit, customer satisfaction will change 0.894, 0.188, 0.214, 0.244 and 0.179

units respectively.

H1: The results show that the beta coefficient of Tangibles is highest and positive at 0.894 and with p

< 0.05. Therefore, the variable Tangibles and customer satisfaction have a significant and positive

relationship. It is important to note that hypothesis H 1 is supported.

H2: Based on Table 4, it is obvious that the factor Reliability has a positive influence on customer

satisfaction with a beta coefficient of 0.188 and p < 0.05. Thus, it can be accepted that hypothesis H 2

is supported.

H3: Regarding the relationship between Responsiveness and customer satisfaction, it can be seen

from the results of Table 4 that the beta coefficient and p-value of Responsiveness are 0.214 and less

than 0.05, respectively. As a result, Responsiveness has a positive impact on customer satisfaction.

Thus, hypothesis H3 is supported.

H4: The results from Table 4 indicate that Assurance is significant in predicting the customer

satisfaction with second highest beta coefficient (0.244) and 0.00 in p-value (lower than 0.05).

Consequently, it is evident that hypothesis H 4 is supported.

H5: Finally, with the beta coefficient 0.179 and p < 0.05, the research findings point out that Empathy

is positively related to Customer Satisfaction of fast food restaurants in the UK. As a result, it can be

concluded that hypothesis H5 is supported.

5 Discussion, Conclusion & Implications of research

The aim of the first hypothesis was to establish a possible causal relationship between tangibles and

customer satisfaction in the context of the UK fast food industry. Its essential elements earned the highest

coefficient value of 0.894. Tangibles play a key role in driving customer satisfaction. Heung et al. (2000)

and Khan et al. (2013) also proved that ‘tangibles’ has a positive impact on customer satisfaction in

restaurants in Hong Kong, and Pakistan’s fast food industry. Similarly, Qin et al. (2009) maintained that

the tangibles of a fast food restaurant directly impact a customers’ experience and on its service. In stark

contrast, the research on service quality and customer satisfaction in the banking industry, Pham (2012)

argued that tangibles do not have any relationship with customer satisfaction. Consequently, it can be

concluded that the higher the customer’s perception of the tangibles variable, higher the satisfaction.

The second hypothesis tests the correlation between ‘reliability’ and customer satisfaction of fast food

restaurants in the UK. The correlation of reliability is significant at the 0.05 level with a low coefficient

value of 0.188. It is clear that this factor has a weak influence on customer satisfaction. Similarly, Quin et

al. (2010) and Bourgoure and Neu (2010) claimed that the level of customer satisfaction and the reliability

of service in China’s and Malaysia’s fast food industries have a weak relationship. Additionally, the

research results of Agbor (2011) indicated that the level of satisfaction depends lightly on the reliability of

service sectors.

The result the third hypothesis is supported by the high coefficient value of 0.214 at the significant

correlation (0.000 of p-value) with customer satisfaction. In this research, r’esponsiveness’ is comprised

of only three items; however, it has a higher coefficient value (0.214) than the other two factors empathy

(0.179) and reliability (0.188) which contain four and five items, respectively. The outcome of the third

units respectively.

H1: The results show that the beta coefficient of Tangibles is highest and positive at 0.894 and with p

< 0.05. Therefore, the variable Tangibles and customer satisfaction have a significant and positive

relationship. It is important to note that hypothesis H 1 is supported.

H2: Based on Table 4, it is obvious that the factor Reliability has a positive influence on customer

satisfaction with a beta coefficient of 0.188 and p < 0.05. Thus, it can be accepted that hypothesis H 2

is supported.

H3: Regarding the relationship between Responsiveness and customer satisfaction, it can be seen

from the results of Table 4 that the beta coefficient and p-value of Responsiveness are 0.214 and less

than 0.05, respectively. As a result, Responsiveness has a positive impact on customer satisfaction.

Thus, hypothesis H3 is supported.

H4: The results from Table 4 indicate that Assurance is significant in predicting the customer

satisfaction with second highest beta coefficient (0.244) and 0.00 in p-value (lower than 0.05).

Consequently, it is evident that hypothesis H 4 is supported.

H5: Finally, with the beta coefficient 0.179 and p < 0.05, the research findings point out that Empathy

is positively related to Customer Satisfaction of fast food restaurants in the UK. As a result, it can be

concluded that hypothesis H5 is supported.

5 Discussion, Conclusion & Implications of research

The aim of the first hypothesis was to establish a possible causal relationship between tangibles and

customer satisfaction in the context of the UK fast food industry. Its essential elements earned the highest

coefficient value of 0.894. Tangibles play a key role in driving customer satisfaction. Heung et al. (2000)

and Khan et al. (2013) also proved that ‘tangibles’ has a positive impact on customer satisfaction in

restaurants in Hong Kong, and Pakistan’s fast food industry. Similarly, Qin et al. (2009) maintained that

the tangibles of a fast food restaurant directly impact a customers’ experience and on its service. In stark

contrast, the research on service quality and customer satisfaction in the banking industry, Pham (2012)

argued that tangibles do not have any relationship with customer satisfaction. Consequently, it can be

concluded that the higher the customer’s perception of the tangibles variable, higher the satisfaction.

The second hypothesis tests the correlation between ‘reliability’ and customer satisfaction of fast food

restaurants in the UK. The correlation of reliability is significant at the 0.05 level with a low coefficient

value of 0.188. It is clear that this factor has a weak influence on customer satisfaction. Similarly, Quin et

al. (2010) and Bourgoure and Neu (2010) claimed that the level of customer satisfaction and the reliability

of service in China’s and Malaysia’s fast food industries have a weak relationship. Additionally, the

research results of Agbor (2011) indicated that the level of satisfaction depends lightly on the reliability of

service sectors.

The result the third hypothesis is supported by the high coefficient value of 0.214 at the significant

correlation (0.000 of p-value) with customer satisfaction. In this research, r’esponsiveness’ is comprised

of only three items; however, it has a higher coefficient value (0.214) than the other two factors empathy

(0.179) and reliability (0.188) which contain four and five items, respectively. The outcome of the third

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

hypothesis is in line with previous studies conducted in fast food restaurants in China (Qin and Prybutok,

2009) and in Malaysia (Bourgoure and Neu, 2010).

The purpose of hypothesis four was to examine the correlation between Assurance and Customer

Satisfaction. The result of the hypothesis provides a high coefficient value of 0.244 with a p-value less

than 0.001. It can be said that the more ‘assurance’ customers perceive, the more they are satisfied. This

outcome is further confirmed by a previous study examining Malaysian fast food restaurants (Bougoure

and Neu, 2010). Similarly, the result of the study done by Heung et al. (2000) in Hong Kong’s airport

restaurants also suggested that the higher a customer evaluates ‘assurance’, the higher is the level of

satisfaction.

Finally, based on the data analysis, the coefficient value (0.179) of ‘empathy’ is lowest compared to other

factors. It can be said that there is weak impact of empathy on customer satisfaction in the context of the

UK fast food industry. The result is confirmed by previous studies that empathy lightly affects customer

satisfaction (Agbor, 2011; Pham, 2012). According to Heung et al. (2000), the empathy factor is rarely

associated with quick service restaurants. Overall, based on the evidence, empathy is not a key driver in

customer satisfaction. However, the research finding supports hypothesis five.

Theoretical implications

This research contributes empirical support to the present theories which focus on the influence of the

five service quality dimensions on the satisfaction of customer in fast food restaurants in the UK. It is

worth noting that the variable ‘tangibles’ plays an essential role in driving customer satisfaction. In

addition, responsiveness and assurance are two further fundamental factors which significantly impact

customer satisfaction in the UK fast food market. Similarly, this study suggests that reliability and empathy

are also important for the overall customer satisfaction of quick service restaurants. It is clear that there is

a significant relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction. Furthermore, based on the

outcomes of the five hypotheses, the nomological validity of the SERVPERF model is valid as an efficient