Food Insecurity of Tertiary Students: Prevalence and Determinants

VerifiedAdded on 2019/09/20

|15

|6636

|156

Report

AI Summary

This report presents the findings of a pilot study conducted at Deakin University, Victoria, Australia, investigating food insecurity among tertiary students. The study, employing a cross-sectional design with a self-reported questionnaire administered to 124 students in 2012, aimed to assess the prevalence, severity, and potential determinants of food insecurity. The results revealed that 18% of students experienced food insecurity without hunger, and an additional 30% experienced food insecurity with hunger, indicating a higher prevalence compared to the general Australian population. Factors associated with food insecurity included living arrangements (students not living with family were more likely to be food insecure) and receiving government support (associated with food insecurity with hunger). The study highlights the vulnerability of tertiary students to food insecurity, potentially due to financial pressures, and underscores the need for further research and policy interventions to support student wellbeing and academic performance. The report uses the USDA-AFSSM to assess the severity of food insecurity and examines the impact of factors like income, living arrangements, and support services on students' ability to procure adequate food. The findings suggest that financial constraints are a key predictor of food insecurity among this demographic.

Nutrition & Dietetics 2014; 71:

258–264

DOI: 10.1111/1747-

0080.12097

25

8

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Food insecurity among university students in

Victoria: A pilot study

Dee A. MICEVSKI,1 Lukar E. THORNTON2 and Sonia BROCKINGTON1

1School of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, Faculty of Health, and 2Centre for Physical Activity and Nutrition

Research, School of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, Deakin University, Burwood, Victoria, Australia

Abstract

Aims: Susceptibility to food insecurity can vary over a life course; however, a potential period of particular

vulnerability is while studying at a tertiary institution. This pilot study aimed to assess the prevalence, severity

and potential determinants of food insecurity among tertiary students attending a Victorian-based institution.

Methods: The present study employed a cross-sectional design, involving use of a self-reported

questionnaire. The survey, conducted in 2012, was administered to a sample of 124 Deakin University students

and contains measures of food insecurity status, demographics and other potential explanatory factors.

Descriptive and regression analysis was undertaken to investigate the prevalence of food insecurity and

associations with factors that may support or hinder a student’s ability to procure food, such as living

arrangements, income and knowledge of support services. Results: Food insecurity without hunger was

reported by 18% of Deakin University students, while an additional 30% reported experiencing the more

severe form of food insecurity (with hunger). A lower odds of being food insecure was reported among

students living with their family (without hunger OR 0.35; 95% CI 0.12–0.99; with hunger OR 0.29; 95% CI

0.12–0.70), while a higher odds was found among those receiving government support (with hunger OR 2.52;

95% CI 1.05–6.04).

Conclusions: The reported prevalence of food insecurity among the tertiary student sample was greater than

the general Australian population, suggesting they are a vulnerable group. This may be attributable to

financial pressures faced when students are not living with their parents.

Key words: food insecurity, risk factors, universities.

Introduction

Food insecurity is defined as the inability to

access and procure, through conventional

avenues, nutritionally adequate foods capable

of supporting an active and healthy lifestyle.1

Food security status exists on a continuum

ranging from: food security, when individuals

show no evidence of food insecurity and

dietary preferences are consistently sat- isfied;

food insecurity without hunger, when regular

consump- tion of food occurs, however anxiety

or uncertainty over access to food of a

sufficient quality or quantity may even- tuate;

and to a greater severity, food insecurity with

hunger, when meals are neglected or

inadequate, with hunger and possibly

malnutrition being direct outcomes.2–4

D.A. Micevski, BAppSc (Food Sc & Nutr)(Hons),

Honours Candidate

L.E. Thornton, PhD, Alfred Deakin Postdoctoral

Research Fellow

S. Brockington, MPH, BHSc(Nutr.Diet)(Hons),

GradCertHigherEd APD, Lecturer

Correspondence: S. Brockington, School of

Exercise and Nutrition

Sciences, Faculty of Health, Deakin

University, 221 Burwood Highway,

Burwood, Victoria, 3125, Australia. Email:

sonia.brockington@deakin.edu.au

Accepted August 2013

258–264

DOI: 10.1111/1747-

0080.12097

25

8

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Food insecurity among university students in

Victoria: A pilot study

Dee A. MICEVSKI,1 Lukar E. THORNTON2 and Sonia BROCKINGTON1

1School of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, Faculty of Health, and 2Centre for Physical Activity and Nutrition

Research, School of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, Deakin University, Burwood, Victoria, Australia

Abstract

Aims: Susceptibility to food insecurity can vary over a life course; however, a potential period of particular

vulnerability is while studying at a tertiary institution. This pilot study aimed to assess the prevalence, severity

and potential determinants of food insecurity among tertiary students attending a Victorian-based institution.

Methods: The present study employed a cross-sectional design, involving use of a self-reported

questionnaire. The survey, conducted in 2012, was administered to a sample of 124 Deakin University students

and contains measures of food insecurity status, demographics and other potential explanatory factors.

Descriptive and regression analysis was undertaken to investigate the prevalence of food insecurity and

associations with factors that may support or hinder a student’s ability to procure food, such as living

arrangements, income and knowledge of support services. Results: Food insecurity without hunger was

reported by 18% of Deakin University students, while an additional 30% reported experiencing the more

severe form of food insecurity (with hunger). A lower odds of being food insecure was reported among

students living with their family (without hunger OR 0.35; 95% CI 0.12–0.99; with hunger OR 0.29; 95% CI

0.12–0.70), while a higher odds was found among those receiving government support (with hunger OR 2.52;

95% CI 1.05–6.04).

Conclusions: The reported prevalence of food insecurity among the tertiary student sample was greater than

the general Australian population, suggesting they are a vulnerable group. This may be attributable to

financial pressures faced when students are not living with their parents.

Key words: food insecurity, risk factors, universities.

Introduction

Food insecurity is defined as the inability to

access and procure, through conventional

avenues, nutritionally adequate foods capable

of supporting an active and healthy lifestyle.1

Food security status exists on a continuum

ranging from: food security, when individuals

show no evidence of food insecurity and

dietary preferences are consistently sat- isfied;

food insecurity without hunger, when regular

consump- tion of food occurs, however anxiety

or uncertainty over access to food of a

sufficient quality or quantity may even- tuate;

and to a greater severity, food insecurity with

hunger, when meals are neglected or

inadequate, with hunger and possibly

malnutrition being direct outcomes.2–4

D.A. Micevski, BAppSc (Food Sc & Nutr)(Hons),

Honours Candidate

L.E. Thornton, PhD, Alfred Deakin Postdoctoral

Research Fellow

S. Brockington, MPH, BHSc(Nutr.Diet)(Hons),

GradCertHigherEd APD, Lecturer

Correspondence: S. Brockington, School of

Exercise and Nutrition

Sciences, Faculty of Health, Deakin

University, 221 Burwood Highway,

Burwood, Victoria, 3125, Australia. Email:

sonia.brockington@deakin.edu.au

Accepted August 2013

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Food insecurity of tertiary

students

25

9

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

Food insecurity represents a significant public

health dilemma and remains a contributor to many

nutritional, health and developmental problems.5,6 In

particular, moder- ate forms of food insecurity

(without hunger) are known to be associated with

chronic diseases including overweight and obesity,

which can be the consequence of a reliance on

cheap calorically dense foods. 7,8 Further, food

insecurity (with hunger) is associated with under

nutrition. 1,9 Experi- encing food insecurity may also

affect psychological, social and economic

wellbeing. 6,10

In Australia, conservative estimates indicated

5.2% of the general population experienced food

insecurity, with 40% of those at a severe level. 10,11

The extent of food insecurity is likely to vary across

the lifespan; however, the years attending a tertiary

institution may be one period of life when food

insecurity becomes pronounced. 12–14 This may be due

to university students having more independence if

they are living out of home for the first time or from

man- aging the demands of both employment and

study. 12,15,16 To date, a few studies have assessed the

prevalence of food insecurity among university

students as well as the poten- tial determinants. 12 A

greater level of understanding is war- ranted given

these students represent a group that will

students

25

9

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

Food insecurity represents a significant public

health dilemma and remains a contributor to many

nutritional, health and developmental problems.5,6 In

particular, moder- ate forms of food insecurity

(without hunger) are known to be associated with

chronic diseases including overweight and obesity,

which can be the consequence of a reliance on

cheap calorically dense foods. 7,8 Further, food

insecurity (with hunger) is associated with under

nutrition. 1,9 Experi- encing food insecurity may also

affect psychological, social and economic

wellbeing. 6,10

In Australia, conservative estimates indicated

5.2% of the general population experienced food

insecurity, with 40% of those at a severe level. 10,11

The extent of food insecurity is likely to vary across

the lifespan; however, the years attending a tertiary

institution may be one period of life when food

insecurity becomes pronounced. 12–14 This may be due

to university students having more independence if

they are living out of home for the first time or from

man- aging the demands of both employment and

study. 12,15,16 To date, a few studies have assessed the

prevalence of food insecurity among university

students as well as the poten- tial determinants. 12 A

greater level of understanding is war- ranted given

these students represent a group that will

Nutrition & Dietetics 2014; 71:

258–264

DOI: 10.1111/1747-

0080.12097

25

8

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

contribute to the future progression and

prosperity of Australia.17,18

Research at Griffith University in

Queensland, Australia,

recently reported that the prevalence of food

insecurity among tertiary students was 72%

(47% without hunger; 25% with hunger) using

a multi-item assessment measure.12 Inter-

nationally, research conducted at the

University of Hawaii (UHM) in the United

States discovered 21% of the student body

experienced food insecurity (15% without

hunger; 6% with hunger) using the United

States Department of Agricul- ture (USDA)

multi-item assessment measure.19

Food insecurity is the outcome of immediate

issues around food availability, accessibility and

utilisation. 9 Although diverse factors expose certain

groups in society to varying degrees of food

insecurity,11 financial constraints are

recognised as a key predictor.20–24 Relevant

indicators of financial status include total

income and income source (employment,

welfare dependency and parental support).20–24

Further, for students who are living

independently away from home for the first

time (renting, share house, university

residence, with extended family), the cost of

living and utility expenses may amplify

economic stress and lead to the displacement

of money away from purchasing nutritious

food.19,25,26

The present pilot study aimed to quantify

the prevalence and severity of food

insecurity among tertiary students enrolled

in a Victorian-based institution (Deakin

University) and to investigate key factors

potentially associated with this. To our

knowledge, the prevalence of and factors

contribut- ing to food insecurity in

Australian students have only been reported

in one prior study. 12 The present study is the

first to undertake this within a Victorian

institute and the first to use multivariate

regression models to examine explanatory

factors. Results may help advocate for

further research funding to assess this issue

on a wider scale and eventually inform

policies to protect the wellbeing of students

as well as their academic performance by

minimising food insecurity prevalence. 9,11

Methods

Deakin University has campuses located in

three townships (Burwood, Geelong (two

separate campuses: Waterfront and Waurn

Ponds) and Warrnambool) within the state of

Victo- ria, Australia, and has over 40 000

enrolled students. Stu- dents from each of

these campuses were eligible to participate,

with the only exclusion criteria being

students below 18 years of age (for ethics

purposes). Students were invited to complete

a self-reported questionnaire on their eating

behaviours and personal characteristics (no

direct mention of food insecurity occurred

during recruitment to avoid bias). All surveys

completed by students were anony- mous.

Ethics approval for this cross-sectional study

was granted by the Deakin University Faculty

of Health Human Ethics Advisory Group.

The recruitment process spanned four

weeks in duration. A range of techniques

were used to recruit participants, including:

on-campus recruitment; information flyers,

bul- letins and posters situated at prominent

sites throughout all

258–264

DOI: 10.1111/1747-

0080.12097

25

8

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

contribute to the future progression and

prosperity of Australia.17,18

Research at Griffith University in

Queensland, Australia,

recently reported that the prevalence of food

insecurity among tertiary students was 72%

(47% without hunger; 25% with hunger) using

a multi-item assessment measure.12 Inter-

nationally, research conducted at the

University of Hawaii (UHM) in the United

States discovered 21% of the student body

experienced food insecurity (15% without

hunger; 6% with hunger) using the United

States Department of Agricul- ture (USDA)

multi-item assessment measure.19

Food insecurity is the outcome of immediate

issues around food availability, accessibility and

utilisation. 9 Although diverse factors expose certain

groups in society to varying degrees of food

insecurity,11 financial constraints are

recognised as a key predictor.20–24 Relevant

indicators of financial status include total

income and income source (employment,

welfare dependency and parental support).20–24

Further, for students who are living

independently away from home for the first

time (renting, share house, university

residence, with extended family), the cost of

living and utility expenses may amplify

economic stress and lead to the displacement

of money away from purchasing nutritious

food.19,25,26

The present pilot study aimed to quantify

the prevalence and severity of food

insecurity among tertiary students enrolled

in a Victorian-based institution (Deakin

University) and to investigate key factors

potentially associated with this. To our

knowledge, the prevalence of and factors

contribut- ing to food insecurity in

Australian students have only been reported

in one prior study. 12 The present study is the

first to undertake this within a Victorian

institute and the first to use multivariate

regression models to examine explanatory

factors. Results may help advocate for

further research funding to assess this issue

on a wider scale and eventually inform

policies to protect the wellbeing of students

as well as their academic performance by

minimising food insecurity prevalence. 9,11

Methods

Deakin University has campuses located in

three townships (Burwood, Geelong (two

separate campuses: Waterfront and Waurn

Ponds) and Warrnambool) within the state of

Victo- ria, Australia, and has over 40 000

enrolled students. Stu- dents from each of

these campuses were eligible to participate,

with the only exclusion criteria being

students below 18 years of age (for ethics

purposes). Students were invited to complete

a self-reported questionnaire on their eating

behaviours and personal characteristics (no

direct mention of food insecurity occurred

during recruitment to avoid bias). All surveys

completed by students were anony- mous.

Ethics approval for this cross-sectional study

was granted by the Deakin University Faculty

of Health Human Ethics Advisory Group.

The recruitment process spanned four

weeks in duration. A range of techniques

were used to recruit participants, including:

on-campus recruitment; information flyers,

bul- letins and posters situated at prominent

sites throughout all

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Food insecurity of tertiary

students

25

9

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

campuses and all faculties; notices via

Deakin Studies Online unit sites; and

announcements made at 10 lectures from

randomly selected courses across all

faculties. Surveys were distributed within

lectures where announcements were

delivered, and also mailed to those who

expressed interest in participating.

Information was posted on a further 68 unit

sites by unit chairs upon request. At the

end of recruitment, 124 surveys were

completed for this pilot study. In place of a

compensation for each participant, a small

donation was made for each survey

completed ($0.25 per survey) to the

charitable food organisation Second Bite.27

To estimate the prevalence and severity

of food insecurity within the student body,

the survey included several ques- tions

derived from the multi-item United States

Department of Agriculture-Adult Food

Security Survey Module (USDA- AFSSM). 3

This survey is the most contemporary,

validated and commonly employed measure

of food insecurity inter- nationally. 10,28

Our questionnaire to assess food

insecurity and associated factors among

tertiary students contained 45 items, in a

format that included both open- and closed-

ended ques- tions. With permission, the

survey was based on that used by Hughes

and colleagues in Queensland, 12 with slight

modifi- cations to accommodate the Deakin

University cohort.

The relative severity of food insecurity

reflected the ranking outlined in the USDA-

AFSSM. 4 This scale’s algo- rithm

categorises individuals as either food

secure, food insecure without hunger, or

food insecure with hunger. 3,25

Individuals were classified as food insecure

without hunger if their responses were ‘often

true’ or ‘sometimes true’ to any of the

following statements related to their current

university year:3,28

I worried that my food would run out

before I had money to buy more.

I couldn’t afford to eat balanced meals.

The food that you bought just didn’t last

and you didn’t have money to get more.

Individuals were classified as food

insecure (with hunger) if, in addition to

answering affirmatively to any of the above

questions, they also answered ‘yes’ to any

of the following: 3,28

Did you ever decrease the size of your

meals or skip meals because there wasn’t

enough money for food?

Were you ever hungry but didn’t eat

because you couldn’t afford enough food?

Did you lose weight because you didn’t

have enough money for food?

Did you ever not eat for a whole day

because there wasn’t enough money for

food?

Those students who responded ‘no’ to the

above questions were classified as food

secure. Factors associated with food

insecurity were measured using a range of

questions, with those examined in the

present study relating to factors that might

support or hinder a student’s ability to

procure food, including: living arrangements

(not living with family or living with family),

employment status (yes or no), personal

annual income ($0–$16 000 or ≥$16 000),

main food con-

students

25

9

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

campuses and all faculties; notices via

Deakin Studies Online unit sites; and

announcements made at 10 lectures from

randomly selected courses across all

faculties. Surveys were distributed within

lectures where announcements were

delivered, and also mailed to those who

expressed interest in participating.

Information was posted on a further 68 unit

sites by unit chairs upon request. At the

end of recruitment, 124 surveys were

completed for this pilot study. In place of a

compensation for each participant, a small

donation was made for each survey

completed ($0.25 per survey) to the

charitable food organisation Second Bite.27

To estimate the prevalence and severity

of food insecurity within the student body,

the survey included several ques- tions

derived from the multi-item United States

Department of Agriculture-Adult Food

Security Survey Module (USDA- AFSSM). 3

This survey is the most contemporary,

validated and commonly employed measure

of food insecurity inter- nationally. 10,28

Our questionnaire to assess food

insecurity and associated factors among

tertiary students contained 45 items, in a

format that included both open- and closed-

ended ques- tions. With permission, the

survey was based on that used by Hughes

and colleagues in Queensland, 12 with slight

modifi- cations to accommodate the Deakin

University cohort.

The relative severity of food insecurity

reflected the ranking outlined in the USDA-

AFSSM. 4 This scale’s algo- rithm

categorises individuals as either food

secure, food insecure without hunger, or

food insecure with hunger. 3,25

Individuals were classified as food insecure

without hunger if their responses were ‘often

true’ or ‘sometimes true’ to any of the

following statements related to their current

university year:3,28

I worried that my food would run out

before I had money to buy more.

I couldn’t afford to eat balanced meals.

The food that you bought just didn’t last

and you didn’t have money to get more.

Individuals were classified as food

insecure (with hunger) if, in addition to

answering affirmatively to any of the above

questions, they also answered ‘yes’ to any

of the following: 3,28

Did you ever decrease the size of your

meals or skip meals because there wasn’t

enough money for food?

Were you ever hungry but didn’t eat

because you couldn’t afford enough food?

Did you lose weight because you didn’t

have enough money for food?

Did you ever not eat for a whole day

because there wasn’t enough money for

food?

Those students who responded ‘no’ to the

above questions were classified as food

secure. Factors associated with food

insecurity were measured using a range of

questions, with those examined in the

present study relating to factors that might

support or hinder a student’s ability to

procure food, including: living arrangements

(not living with family or living with family),

employment status (yes or no), personal

annual income ($0–$16 000 or ≥$16 000),

main food con-

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

D.A. Micevski

et al.

26

0

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

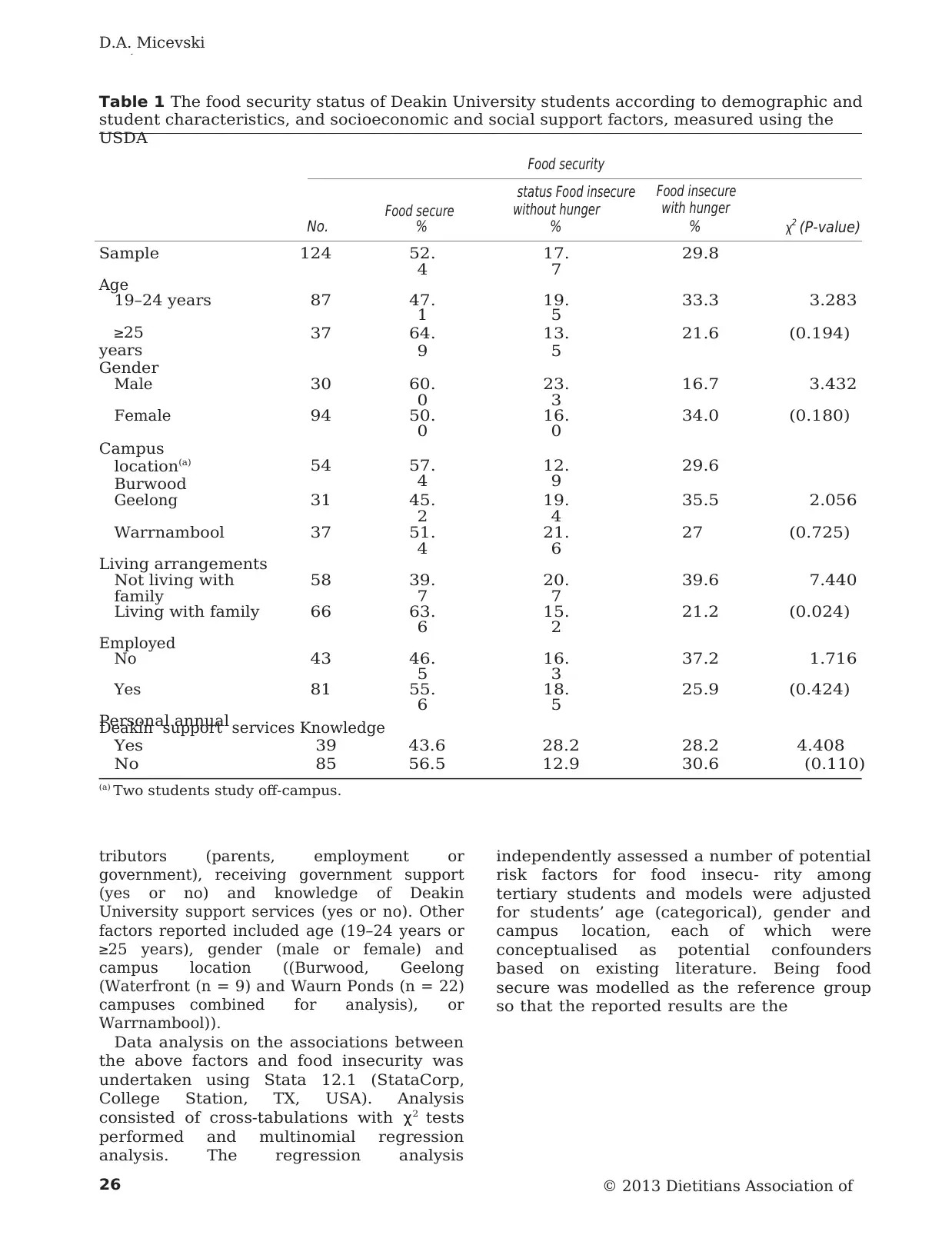

Table 1 The food security status of Deakin University students according to demographic and

student characteristics, and socioeconomic and social support factors, measured using the

USDA

Food secure

Food security

status Food insecure

without hunger

Food insecure

with hunger

Deakin support services Knowledge

Yes 39 43.6 28.2 28.2 4.408

No 85 56.5 12.9 30.6 (0.110)

(a) Two students study off-campus.

tributors (parents, employment or

government), receiving government support

(yes or no) and knowledge of Deakin

University support services (yes or no). Other

factors reported included age (19–24 years or

≥25 years), gender (male or female) and

campus location ((Burwood, Geelong

(Waterfront (n = 9) and Waurn Ponds (n = 22)

campuses combined for analysis), or

Warrnambool)).

Data analysis on the associations between

the above factors and food insecurity was

undertaken using Stata 12.1 (StataCorp,

College Station, TX, USA). Analysis

consisted of cross-tabulations with χ 2 tests

performed and multinomial regression

analysis. The regression analysis

independently assessed a number of potential

risk factors for food insecu- rity among

tertiary students and models were adjusted

for students’ age (categorical), gender and

campus location, each of which were

conceptualised as potential confounders

based on existing literature. Being food

secure was modelled as the reference group

so that the reported results are the

No. % % % χ2 (P-value)

Sample 124 52.

4

17.

7

29.8

Age

19–24 years 87 47.

1 19.

5 33.3 3.283

≥25

years

Gender

37 64.

9

13.

5

21.6 (0.194)

Male 30 60.

0

23.

3

16.7 3.432

Female 94 50.

0

16.

0

34.0 (0.180)

Campus

location (a)

Burwood

54 57.

4

12.

9

29.6

Geelong 31 45.

2

19.

4

35.5 2.056

Warrnambool 37 51.

4

21.

6

27 (0.725)

Living arrangements

Not living with

family

58 39.

7

20.

7

39.6 7.440

Living with family 66 63.

6

15.

2

21.2 (0.024)

Employed

No 43 46.

5

16.

3

37.2 1.716

Yes 81 55.

6

18.

5

25.9 (0.424)

Personal annual

et al.

26

0

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

Table 1 The food security status of Deakin University students according to demographic and

student characteristics, and socioeconomic and social support factors, measured using the

USDA

Food secure

Food security

status Food insecure

without hunger

Food insecure

with hunger

Deakin support services Knowledge

Yes 39 43.6 28.2 28.2 4.408

No 85 56.5 12.9 30.6 (0.110)

(a) Two students study off-campus.

tributors (parents, employment or

government), receiving government support

(yes or no) and knowledge of Deakin

University support services (yes or no). Other

factors reported included age (19–24 years or

≥25 years), gender (male or female) and

campus location ((Burwood, Geelong

(Waterfront (n = 9) and Waurn Ponds (n = 22)

campuses combined for analysis), or

Warrnambool)).

Data analysis on the associations between

the above factors and food insecurity was

undertaken using Stata 12.1 (StataCorp,

College Station, TX, USA). Analysis

consisted of cross-tabulations with χ 2 tests

performed and multinomial regression

analysis. The regression analysis

independently assessed a number of potential

risk factors for food insecu- rity among

tertiary students and models were adjusted

for students’ age (categorical), gender and

campus location, each of which were

conceptualised as potential confounders

based on existing literature. Being food

secure was modelled as the reference group

so that the reported results are the

No. % % % χ2 (P-value)

Sample 124 52.

4

17.

7

29.8

Age

19–24 years 87 47.

1 19.

5 33.3 3.283

≥25

years

Gender

37 64.

9

13.

5

21.6 (0.194)

Male 30 60.

0

23.

3

16.7 3.432

Female 94 50.

0

16.

0

34.0 (0.180)

Campus

location (a)

Burwood

54 57.

4

12.

9

29.6

Geelong 31 45.

2

19.

4

35.5 2.056

Warrnambool 37 51.

4

21.

6

27 (0.725)

Living arrangements

Not living with

family

58 39.

7

20.

7

39.6 7.440

Living with family 66 63.

6

15.

2

21.2 (0.024)

Employed

No 43 46.

5

16.

3

37.2 1.716

Yes 81 55.

6

18.

5

25.9 (0.424)

Personal annual

Food insecurity of tertiary

students

26

1

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

likelihood of being either food insecure

without hunger or with hunger compared

with those who are food secure.

Results

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of

students by food security status. Half of the

sample (52%) reported being food secure.

Almost 18% reported experiencing food

insecurity without hunger and a further

30% experienced the more severe food

insecure with hunger. A greater

percentage of students (60%) not living

with their family reported food insecurity

(without (21%) and with hunger (40%)),

com- pared with those living with family

(36%; 15% without hunger and 21% with

hunger). A greater percentage of stu- dents

(60%) who received government benefits

also reported higher levels of food

insecurity compared with those who were

not government income support recipients

(36%). Food security status did not differ

by age, gender, campus

students

26

1

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

likelihood of being either food insecure

without hunger or with hunger compared

with those who are food secure.

Results

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of

students by food security status. Half of the

sample (52%) reported being food secure.

Almost 18% reported experiencing food

insecurity without hunger and a further

30% experienced the more severe food

insecure with hunger. A greater

percentage of students (60%) not living

with their family reported food insecurity

(without (21%) and with hunger (40%)),

com- pared with those living with family

(36%; 15% without hunger and 21% with

hunger). A greater percentage of stu- dents

(60%) who received government benefits

also reported higher levels of food

insecurity compared with those who were

not government income support recipients

(36%). Food security status did not differ

by age, gender, campus

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

D.A. Micevski

et al.

26

0

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

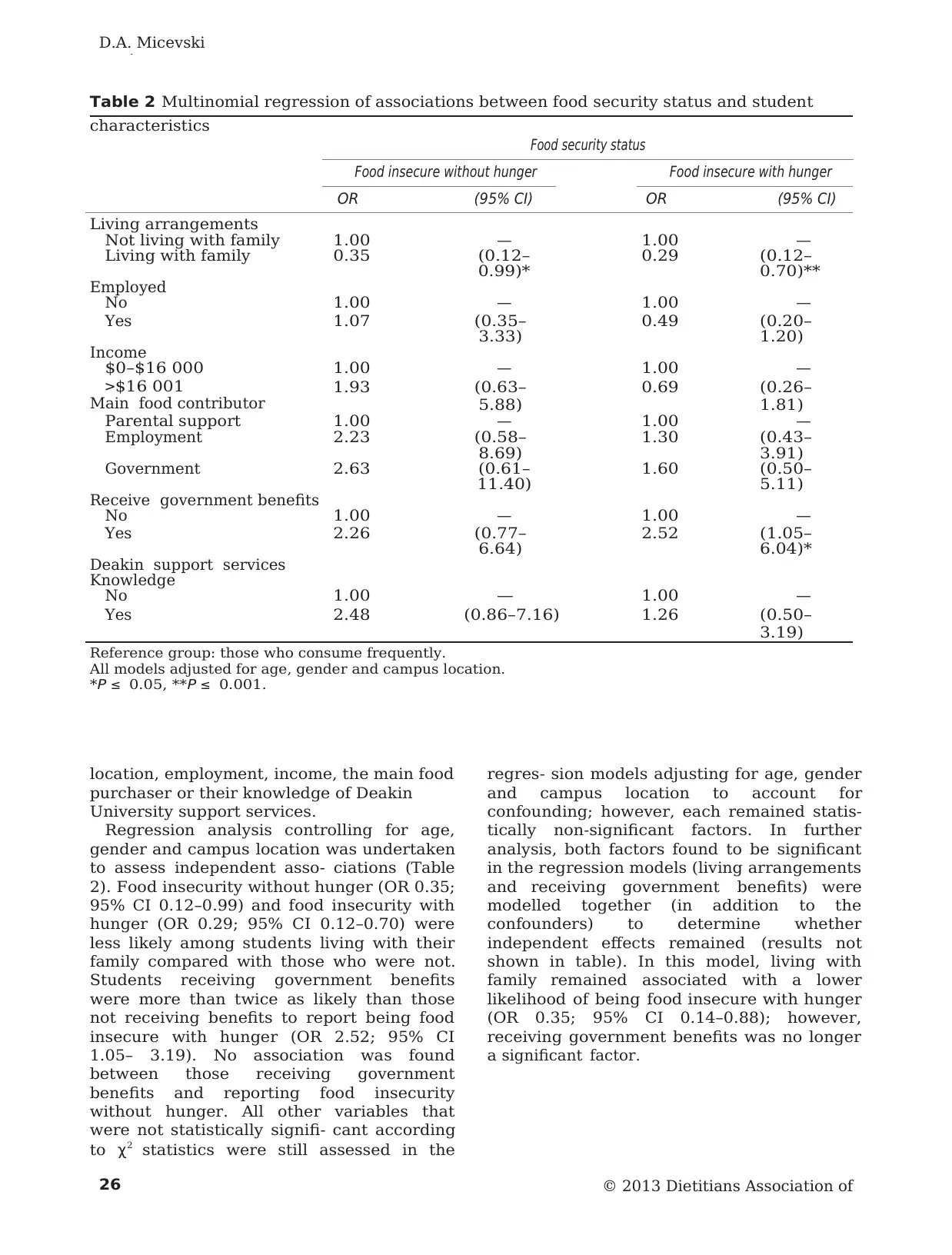

Table 2 Multinomial regression of associations between food security status and student

characteristics

Food security status

Food insecure without hunger Food insecure with hunger

OR (95% CI) OR (95% CI)

Living arrangements

Not living with family 1.00 — 1.00 —

Living with family 0.35 (0.12–

0.99)*

0.29 (0.12–

0.70)**

Employed

No 1.00 — 1.00 —

Yes 1.07 (0.35–

3.33)

0.49 (0.20–

1.20)

Income

$0–$16 000 1.00 — 1.00 —

>$16 001

Main food contributor

1.93 (0.63–

5.88)

0.69 (0.26–

1.81)

Parental support 1.00 — 1.00 —

Employment 2.23 (0.58–

8.69)

1.30 (0.43–

3.91)

Government 2.63 (0.61–

11.40)

1.60 (0.50–

5.11)

Receive government benefits

No 1.00 — 1.00 —

Yes 2.26 (0.77–

6.64)

2.52 (1.05–

6.04)*

Deakin support services

Knowledge

No 1.00 — 1.00 —

Yes 2.48 (0.86–7.16) 1.26 (0.50–

3.19)

Reference group: those who consume frequently.

All models adjusted for age, gender and campus location.

*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.001.

location, employment, income, the main food

purchaser or their knowledge of Deakin

University support services.

Regression analysis controlling for age,

gender and campus location was undertaken

to assess independent asso- ciations (Table

2). Food insecurity without hunger (OR 0.35;

95% CI 0.12–0.99) and food insecurity with

hunger (OR 0.29; 95% CI 0.12–0.70) were

less likely among students living with their

family compared with those who were not.

Students receiving government benefits

were more than twice as likely than those

not receiving benefits to report being food

insecure with hunger (OR 2.52; 95% CI

1.05– 3.19). No association was found

between those receiving government

benefits and reporting food insecurity

without hunger. All other variables that

were not statistically signifi- cant according

to χ 2 statistics were still assessed in the

regres- sion models adjusting for age, gender

and campus location to account for

confounding; however, each remained statis-

tically non-significant factors. In further

analysis, both factors found to be significant

in the regression models (living arrangements

and receiving government benefits) were

modelled together (in addition to the

confounders) to determine whether

independent effects remained (results not

shown in table). In this model, living with

family remained associated with a lower

likelihood of being food insecure with hunger

(OR 0.35; 95% CI 0.14–0.88); however,

receiving government benefits was no longer

a significant factor.

et al.

26

0

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

Table 2 Multinomial regression of associations between food security status and student

characteristics

Food security status

Food insecure without hunger Food insecure with hunger

OR (95% CI) OR (95% CI)

Living arrangements

Not living with family 1.00 — 1.00 —

Living with family 0.35 (0.12–

0.99)*

0.29 (0.12–

0.70)**

Employed

No 1.00 — 1.00 —

Yes 1.07 (0.35–

3.33)

0.49 (0.20–

1.20)

Income

$0–$16 000 1.00 — 1.00 —

>$16 001

Main food contributor

1.93 (0.63–

5.88)

0.69 (0.26–

1.81)

Parental support 1.00 — 1.00 —

Employment 2.23 (0.58–

8.69)

1.30 (0.43–

3.91)

Government 2.63 (0.61–

11.40)

1.60 (0.50–

5.11)

Receive government benefits

No 1.00 — 1.00 —

Yes 2.26 (0.77–

6.64)

2.52 (1.05–

6.04)*

Deakin support services

Knowledge

No 1.00 — 1.00 —

Yes 2.48 (0.86–7.16) 1.26 (0.50–

3.19)

Reference group: those who consume frequently.

All models adjusted for age, gender and campus location.

*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.001.

location, employment, income, the main food

purchaser or their knowledge of Deakin

University support services.

Regression analysis controlling for age,

gender and campus location was undertaken

to assess independent asso- ciations (Table

2). Food insecurity without hunger (OR 0.35;

95% CI 0.12–0.99) and food insecurity with

hunger (OR 0.29; 95% CI 0.12–0.70) were

less likely among students living with their

family compared with those who were not.

Students receiving government benefits

were more than twice as likely than those

not receiving benefits to report being food

insecure with hunger (OR 2.52; 95% CI

1.05– 3.19). No association was found

between those receiving government

benefits and reporting food insecurity

without hunger. All other variables that

were not statistically signifi- cant according

to χ 2 statistics were still assessed in the

regres- sion models adjusting for age, gender

and campus location to account for

confounding; however, each remained statis-

tically non-significant factors. In further

analysis, both factors found to be significant

in the regression models (living arrangements

and receiving government benefits) were

modelled together (in addition to the

confounders) to determine whether

independent effects remained (results not

shown in table). In this model, living with

family remained associated with a lower

likelihood of being food insecure with hunger

(OR 0.35; 95% CI 0.14–0.88); however,

receiving government benefits was no longer

a significant factor.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Food insecurity of tertiary

students

26

1

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

Discussion

The prevalence of food insecurity among

the Deakin Univer- sity student sample was

48% (18% without hunger; 30% with

hunger). While not used in analysis, a

single-item measure comparable to the

Australian National Nutrition Survey was

also asked of the students with 17%

reporting food insecurity when this method

was employed. Although larger studies are

required to confirm these figures, both

measures indicate that the prevalence of

food insecurity is higher among students

than within the broader Australian

population (5.2%). 29

The prevalence of Deakin University

students reporting food insecurity was

lower (48%) than previously reported in

Australia at Griffith University (72%). 12

However, a slightly higher prevalence of

students experiencing the more severe

form of food insecurity (with hunger) was

reported at Deakin University (30%)

compared with students at Griffith

University (25%). 12 Internationally, the

prevalence was also greater than previous

estimates among tertiary cohorts at UHM,

where 15% of students were food insecure

without hunger and 6% with hunger. 19

The findings of the present study

demonstrated that those living away from

their family may be most vulnerable to

experiencing food insecurity. This

association remained evident after being

modelled with government support, indi-

cating extra support for those living out of

home may be

students

26

1

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

Discussion

The prevalence of food insecurity among

the Deakin Univer- sity student sample was

48% (18% without hunger; 30% with

hunger). While not used in analysis, a

single-item measure comparable to the

Australian National Nutrition Survey was

also asked of the students with 17%

reporting food insecurity when this method

was employed. Although larger studies are

required to confirm these figures, both

measures indicate that the prevalence of

food insecurity is higher among students

than within the broader Australian

population (5.2%). 29

The prevalence of Deakin University

students reporting food insecurity was

lower (48%) than previously reported in

Australia at Griffith University (72%). 12

However, a slightly higher prevalence of

students experiencing the more severe

form of food insecurity (with hunger) was

reported at Deakin University (30%)

compared with students at Griffith

University (25%). 12 Internationally, the

prevalence was also greater than previous

estimates among tertiary cohorts at UHM,

where 15% of students were food insecure

without hunger and 6% with hunger. 19

The findings of the present study

demonstrated that those living away from

their family may be most vulnerable to

experiencing food insecurity. This

association remained evident after being

modelled with government support, indi-

cating extra support for those living out of

home may be

262 © 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

Food insecurity of tertiary

students

required. We also found that those receiving

government benefits were more at risk of

food insecurity; however, when modelled

with living arrangements such a relationship

was no longer significant. This may be

indicative that many of those living out of

home would also be the same people

receiving government support and that

living out of home is the more dominant

factor.

It has previously been acknowledged that

many students may experience poverty and

increased financial strain, and this may be

accentuated for students living away from

home or who are reliant on government

support (Youth Allowance, Austudy or

ABSTUDY).12,30,31 Further, the increasing costs

of living coupled with higher education

expenses32–34 may be particularly challenging

for these students to manage,19,35 thereby

increasing their risk of experiencing food

insecu- rity.12,36 The present study reported that

food insecurity was less likely to arise among

students who were residing with their family

compared with those who were not. This is

consistent with findings at Griffith University,

where 40% of the student body sampled were

living with their parents and were significantly

less likely to be food insecure.12 Similarly, at

UHM, 11% of students living with their

parents reported being food insecure versus

31% living with roommates.19

Deakin University students alone were

twice as likely to be food insecure with

hunger when receiving government ben-

efits, irrespective of age, gender and

campus location. The Australian

Government has emphasised that quality

tertiary education is required to develop a

productive and innovative workforce and

meet emerging skill shortages, 33 elements of

which are critical within a competitive

global economy, and essential to improving

Australia’s social and human capital.15

However, tertiary education participation

and the ability of students to excel in their

studies may become compromised if periods

of food insecurity persist. 6,17

In the current environment, it is plausible

that existing government support

arrangements may be insufficient to

accommodate both students’ educational

and personal needs, including their dietary

requirements. 16,21,36 For stu- dents receiving

Youth Allowance alone, the maximum annual

income from the commonwealth is $9023

(including start-up scholarships). 37 This

figure is well below the average Australian

income of $56 175 (pre-tax). 38 Using the

Hender- son poverty line, a standard measure

that assesses the adequacy of income relative

to income units, this figure is 55%–64% below

the June Quarter (2012) poverty line of

$19 994 (for single/unemployed individuals)

and $24 658 (for single/employed

individuals), respectively. 39,40

Reconfigured government policies relating to

student income support were recently

introduced to enhance acces- sibility and equity

primarily to low socioeconomic status,

indigenous, rural and remote students.17,30

These included the student start-up scholarship, the

relocation scholarship and the new supplementary

allowance (announced in the 2012– 2013

budget).15,41,42 Future studies are required to

monitor the effectiveness of these policies on

improving student wellbeing.

It was not within the scope of the present

study to explore and determine the impact of

food insecurity upon health

Australia

Food insecurity of tertiary

students

required. We also found that those receiving

government benefits were more at risk of

food insecurity; however, when modelled

with living arrangements such a relationship

was no longer significant. This may be

indicative that many of those living out of

home would also be the same people

receiving government support and that

living out of home is the more dominant

factor.

It has previously been acknowledged that

many students may experience poverty and

increased financial strain, and this may be

accentuated for students living away from

home or who are reliant on government

support (Youth Allowance, Austudy or

ABSTUDY).12,30,31 Further, the increasing costs

of living coupled with higher education

expenses32–34 may be particularly challenging

for these students to manage,19,35 thereby

increasing their risk of experiencing food

insecu- rity.12,36 The present study reported that

food insecurity was less likely to arise among

students who were residing with their family

compared with those who were not. This is

consistent with findings at Griffith University,

where 40% of the student body sampled were

living with their parents and were significantly

less likely to be food insecure.12 Similarly, at

UHM, 11% of students living with their

parents reported being food insecure versus

31% living with roommates.19

Deakin University students alone were

twice as likely to be food insecure with

hunger when receiving government ben-

efits, irrespective of age, gender and

campus location. The Australian

Government has emphasised that quality

tertiary education is required to develop a

productive and innovative workforce and

meet emerging skill shortages, 33 elements of

which are critical within a competitive

global economy, and essential to improving

Australia’s social and human capital.15

However, tertiary education participation

and the ability of students to excel in their

studies may become compromised if periods

of food insecurity persist. 6,17

In the current environment, it is plausible

that existing government support

arrangements may be insufficient to

accommodate both students’ educational

and personal needs, including their dietary

requirements. 16,21,36 For stu- dents receiving

Youth Allowance alone, the maximum annual

income from the commonwealth is $9023

(including start-up scholarships). 37 This

figure is well below the average Australian

income of $56 175 (pre-tax). 38 Using the

Hender- son poverty line, a standard measure

that assesses the adequacy of income relative

to income units, this figure is 55%–64% below

the June Quarter (2012) poverty line of

$19 994 (for single/unemployed individuals)

and $24 658 (for single/employed

individuals), respectively. 39,40

Reconfigured government policies relating to

student income support were recently

introduced to enhance acces- sibility and equity

primarily to low socioeconomic status,

indigenous, rural and remote students.17,30

These included the student start-up scholarship, the

relocation scholarship and the new supplementary

allowance (announced in the 2012– 2013

budget).15,41,42 Future studies are required to

monitor the effectiveness of these policies on

improving student wellbeing.

It was not within the scope of the present

study to explore and determine the impact of

food insecurity upon health

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

26

3

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

D.A. Micevski

et al.status; however, prior research has

demonstrated food inse- curity being

attributable to a myriad of short- and long-

term health complications, immediate

effects being hunger, anxiety, fatigue,

lethargy and illness. 6,7,24,43,44 Food insecurity

has shown to affect academic performance

through the reduced attendance, aptitude,

motivation, and concentration of children

and adolescents of various ages. 45,46 At a

tertiary level, no studies have investigated

the relationship between food insecurity

and academic performance. However, infe-

rior income support (a risk factor for food

insecurity) has led to adverse impacts on

university participation, completion rates

and the quality of a higher education

experience. 17 Additionally, a greater

reliance on employment has also been

reported, which may displace time

allocated towards study. 16 To date, the

effect of government support on the health

conditions and academic performance of

food insecure students at a tertiary level

has not been extensively investigated. 19

The key outcomes of the present study

were based on a validated food insecurity

measurement tool (USDA). 3 The application

of this tool to a tertiary student population

pre- viously allowed for a consistent

methodological approach to be maintained.

However, future research may aim to

develop food insecurity measures that are

more sensitive to detecting the extent of

food insecurity among students. This may

involve the inclusion of modified measures

of explanatory factors, such as more

precise indicators of income, and income

sources capable of detecting greater

variance among a student population, as

well as the impact of students’ living

arrangements. Although the present study

includes a rela- tively small sample size, it

does however provide evidence of some

potentially important determinants and can

be used to advocate for a larger scale study

exploring this topic. Stu- dents from all

faculties participated in the study;

however, it is noted that the present

sample was overrepresented by health

faculty students (70%). As food insecurity

was not directly mentioned during

recruitment, it is unlikely that those who

chose to participate did so specifically

because they were suffering from food

insecurity and it is more likely that their

participation was due to a personal and

profes- sional interest in nutrition-related

issues. The survey data were collected

early in the study year, and although the

students may have been at the institute for

several years, this still potentially represents

a period of adjustment. Future research

tracking students over a year or the period

of their degree may help elucidate critical

time points for interven- tions. Importantly,

surveillance of this nature could also help

determine the long-term consequences of

food insecurity. Finally, the cross-sectional

nature of the present study negates any

opportunity to determine temporal

influences and can instead only assist in

detecting cross-sectional asso- ciations

between food insecurity and the tested

independent variables. 47,48

The present study contributes to the

current understand- ing of food insecurity

among tertiary students. Importantly, it

highlights that the extent of food insecurity

among other universities, nationally and

internationally, requires further monitoring,

which could be instigated by the

higher

3

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

D.A. Micevski

et al.status; however, prior research has

demonstrated food inse- curity being

attributable to a myriad of short- and long-

term health complications, immediate

effects being hunger, anxiety, fatigue,

lethargy and illness. 6,7,24,43,44 Food insecurity

has shown to affect academic performance

through the reduced attendance, aptitude,

motivation, and concentration of children

and adolescents of various ages. 45,46 At a

tertiary level, no studies have investigated

the relationship between food insecurity

and academic performance. However, infe-

rior income support (a risk factor for food

insecurity) has led to adverse impacts on

university participation, completion rates

and the quality of a higher education

experience. 17 Additionally, a greater

reliance on employment has also been

reported, which may displace time

allocated towards study. 16 To date, the

effect of government support on the health

conditions and academic performance of

food insecure students at a tertiary level

has not been extensively investigated. 19

The key outcomes of the present study

were based on a validated food insecurity

measurement tool (USDA). 3 The application

of this tool to a tertiary student population

pre- viously allowed for a consistent

methodological approach to be maintained.

However, future research may aim to

develop food insecurity measures that are

more sensitive to detecting the extent of

food insecurity among students. This may

involve the inclusion of modified measures

of explanatory factors, such as more

precise indicators of income, and income

sources capable of detecting greater

variance among a student population, as

well as the impact of students’ living

arrangements. Although the present study

includes a rela- tively small sample size, it

does however provide evidence of some

potentially important determinants and can

be used to advocate for a larger scale study

exploring this topic. Stu- dents from all

faculties participated in the study;

however, it is noted that the present

sample was overrepresented by health

faculty students (70%). As food insecurity

was not directly mentioned during

recruitment, it is unlikely that those who

chose to participate did so specifically

because they were suffering from food

insecurity and it is more likely that their

participation was due to a personal and

profes- sional interest in nutrition-related

issues. The survey data were collected

early in the study year, and although the

students may have been at the institute for

several years, this still potentially represents

a period of adjustment. Future research

tracking students over a year or the period

of their degree may help elucidate critical

time points for interven- tions. Importantly,

surveillance of this nature could also help

determine the long-term consequences of

food insecurity. Finally, the cross-sectional

nature of the present study negates any

opportunity to determine temporal

influences and can instead only assist in

detecting cross-sectional asso- ciations

between food insecurity and the tested

independent variables. 47,48

The present study contributes to the

current understand- ing of food insecurity

among tertiary students. Importantly, it

highlights that the extent of food insecurity

among other universities, nationally and

internationally, requires further monitoring,

which could be instigated by the

higher

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Food insecurity of tertiary

students

264 © 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

educational institutes. 29 This knowledge will

be beneficial for public health and welfare

bodies. 1,9 Future researchers should

orientate the focus around identifying the

prevalence, determinants, health and

academic outcomes aligned with students’

food insecurity experiences. 19,49 Researchers

should continue to implement a validated

measure of food insecurity such as the

USDA tool in order to maintain a consistent

and accurate assessment of food insecurity

among students. 49

Food insecurity without hunger is a

significant problem for one in every six

students surveyed at Deakin University, and

food insecurity with hunger a pressing

concern for one in every three students.

Therefore, a need exists to increase food

availability and accessibility at Deakin

University with one possibility being the

establishment of on-campus food banks, a

strategy that is consistent with

recommendations from UHM and Canadian

universities. 13,19,50 However, this should not

be treated as a solution and further work

deter- mining and intervening on causes of

food insecurity in ter- tiary population is

required.

Funding source

This research was conducted at Deakin

University as part of the Bachelor of Food

Science and Nutrition Honours degree

completed by Dee Angelina Micevski, under

the supervision of Sonia Brockington and Dr

Lukar Thornton. The authors would like to

extend their sincerest gratitude to Roger

Hughes of Griffith University (Queensland) for

initial guid- ance and consent towards

utilisation of research tools.

Authorship

S. Brockington and L. Thornton designed the

study and developed the research survey; D. A.

Micevski collected the data; D. A. Micevski

and L. Thornton undertook data analy- sis. D.

A. Micevski wrote the first draft of this paper.

L. Thornton and S. Brockington assisted with

redrafting and editing this paper. All authors

contributed to, read and approved the final

manuscript.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare for

all authors on the paper.

References

1 Holben DH. Position of the American Dietetic

Association: food insecurity in the United States. J

Am Diet Assoc 2010; 110: 1368–77.

2 Rosier K. Food Insecurity in Australia: What Is It, Who

Experiences It and How Can Child and Family Services Support

Families Expe- riencing It? Canberra: Australian

Institute of Family Studies, 2011; (Available from:

http://www.aifs.gov.au/cafca/pubs/sheets/ ps/ps9.pdf,

accessed 30 March 2012).

3 Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J.

USDA Guide to Measuring Food Security: Revised 2000.

Alexandria, VA: U.S.

students

264 © 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

educational institutes. 29 This knowledge will

be beneficial for public health and welfare

bodies. 1,9 Future researchers should

orientate the focus around identifying the

prevalence, determinants, health and

academic outcomes aligned with students’

food insecurity experiences. 19,49 Researchers

should continue to implement a validated

measure of food insecurity such as the

USDA tool in order to maintain a consistent

and accurate assessment of food insecurity

among students. 49

Food insecurity without hunger is a

significant problem for one in every six

students surveyed at Deakin University, and

food insecurity with hunger a pressing

concern for one in every three students.

Therefore, a need exists to increase food

availability and accessibility at Deakin

University with one possibility being the

establishment of on-campus food banks, a

strategy that is consistent with

recommendations from UHM and Canadian

universities. 13,19,50 However, this should not

be treated as a solution and further work

deter- mining and intervening on causes of

food insecurity in ter- tiary population is

required.

Funding source

This research was conducted at Deakin

University as part of the Bachelor of Food

Science and Nutrition Honours degree

completed by Dee Angelina Micevski, under

the supervision of Sonia Brockington and Dr

Lukar Thornton. The authors would like to

extend their sincerest gratitude to Roger

Hughes of Griffith University (Queensland) for

initial guid- ance and consent towards

utilisation of research tools.

Authorship

S. Brockington and L. Thornton designed the

study and developed the research survey; D. A.

Micevski collected the data; D. A. Micevski

and L. Thornton undertook data analy- sis. D.

A. Micevski wrote the first draft of this paper.

L. Thornton and S. Brockington assisted with

redrafting and editing this paper. All authors

contributed to, read and approved the final

manuscript.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare for

all authors on the paper.

References

1 Holben DH. Position of the American Dietetic

Association: food insecurity in the United States. J

Am Diet Assoc 2010; 110: 1368–77.

2 Rosier K. Food Insecurity in Australia: What Is It, Who

Experiences It and How Can Child and Family Services Support

Families Expe- riencing It? Canberra: Australian

Institute of Family Studies, 2011; (Available from:

http://www.aifs.gov.au/cafca/pubs/sheets/ ps/ps9.pdf,

accessed 30 March 2012).

3 Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J.

USDA Guide to Measuring Food Security: Revised 2000.

Alexandria, VA: U.S.

D.A. Micevski

et al.

26

3

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

Department of Agriculture, Food & Nutrition

Service, 2000; (Available from:

http://www.fns.usda.gov/fsec/files/fsguide.pdf,

accessed 8 May 2012).

4 Derrickson JP, Brown AC. Food security

stakeholders in Hawaii: perceptions of food

security monitoring. J Nutr Educ Behav 2002;

34: 72–84.

5 Sullivan AF, Clark S, Pallin DJ, Camargo CA, Jr.

Food security, health, and medication

expenditures of emergency department

patients. J Emerg Med 2010; 38: 524–8.

6 Burns C, Kristjansson B, Harris G et al.

Community level inter- ventions to improve food

security in developed countries. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2010; (12) Art. No.: CD008913.

DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD008913.

7 Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food

insecurity is associ- ated with chronic disease

among Low-Income NHANES partici- pants. J

Nutr 2010; 140: 304–10.

8 Burns C. A Review of the Literature Describing the Link

between Poverty, Food Insecurity and Obesity with Specific

Reference to Aus- tralia. Melbourne: VicHealth,

2004; (Available from: http://

www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/Search.aspx?q=food

%20insecurity, accessed 9 June 2012).

9 Innes-Hughes C, Bowers K, King L, Chapman K,

Eden B. Food Security: The What, Who, Why and

Where to of Food Security in NSW. Sydney: Physical

Activity & Nutrition Obesity Research Group,

Heart Foundation NSW, Cancer Council

NSW, 2010; (Available from:

http://www.heartfoundation.org.au/

SiteCollectionDocuments/Food-Security-

Discussion-Paper

-2010.pdf, accessed 26 February 2012).

10 Temple JB. Severe and moderate forms of food

insecurity in Australia: are they distinguishable?

Aust J Soc Issues 2008; 43: 649–68.

11 Law IR, Ward PR, Coveney J. Food insecurity in

South Austral- ian single parents: an

assessment of the livelihoods framework

approach. Crit Publ Health 2011; 21: 455–69.

12 Hughes R, Serebryanikova I, Donaldson K,

Leveritt M. Student food insecurity: the

skeleton in the university closet. Nutr Diet

2011; 68: 27–32.

13 Willows ND, Au V. Nutritional quality and price

of university food bank hampers. Can J Diet

Pract Res 2006; 67: 104–7.

14 VicHealth. Fact Sheet: Food Security. Melbourne:

Victorian Gov- ernment, 2007; (Available from:

http://www.vichealth.vic.gov. au/Programs-and-

Projects/Healthy-Eating.aspx, accessed 31

March 2012).

15 Australian Government. Transforming Australia’s Tertiary

Educa- tion System. Canberra: Australian

Government, 2009; (Avail- able from:

http://www.innovation.gov.au/HigherEducation/

ResourcesAndPublications/TransformingAustral

iasHigher EducationSystem/Pages/default.aspx,

accessed 14 September 2012).

16 James R, Bexley E, Delvin M, Margison S. Australian

university

student finances 2006: final report of a national survey on

students in public universities. The University of

Melbourne: Centre for the Study of Higher

Education; 2007 (Available from: http://

www.universitiesaustralia.edu.au/page/submissio

ns—reports/ commissioned-studies/student-

finances-survey/, accessed 2

May 2012).

17 Department of Education Employment &

Workplace Relations. Review of Australian Higher

Education: Final Report. Canberra: Australian

Government, 2008; (Available from:

http://www.innovation.gov.au/HigherEducation/Res

ourcesAnd

Publications/ReviewOfAustralianHigherEducatio

n/Pages/

ReviewOfAustralianHigherEducationReport.aspx,

accessed 14

September 2012).

et al.

26

3

© 2013 Dietitians Association of

Australia

Department of Agriculture, Food & Nutrition

Service, 2000; (Available from:

http://www.fns.usda.gov/fsec/files/fsguide.pdf,

accessed 8 May 2012).

4 Derrickson JP, Brown AC. Food security

stakeholders in Hawaii: perceptions of food

security monitoring. J Nutr Educ Behav 2002;

34: 72–84.

5 Sullivan AF, Clark S, Pallin DJ, Camargo CA, Jr.

Food security, health, and medication

expenditures of emergency department

patients. J Emerg Med 2010; 38: 524–8.

6 Burns C, Kristjansson B, Harris G et al.

Community level inter- ventions to improve food

security in developed countries. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2010; (12) Art. No.: CD008913.

DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD008913.

7 Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food

insecurity is associ- ated with chronic disease

among Low-Income NHANES partici- pants. J

Nutr 2010; 140: 304–10.

8 Burns C. A Review of the Literature Describing the Link

between Poverty, Food Insecurity and Obesity with Specific

Reference to Aus- tralia. Melbourne: VicHealth,

2004; (Available from: http://

www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/Search.aspx?q=food

%20insecurity, accessed 9 June 2012).

9 Innes-Hughes C, Bowers K, King L, Chapman K,

Eden B. Food Security: The What, Who, Why and

Where to of Food Security in NSW. Sydney: Physical

Activity & Nutrition Obesity Research Group,

Heart Foundation NSW, Cancer Council

NSW, 2010; (Available from:

http://www.heartfoundation.org.au/

SiteCollectionDocuments/Food-Security-

Discussion-Paper

-2010.pdf, accessed 26 February 2012).

10 Temple JB. Severe and moderate forms of food

insecurity in Australia: are they distinguishable?

Aust J Soc Issues 2008; 43: 649–68.

11 Law IR, Ward PR, Coveney J. Food insecurity in

South Austral- ian single parents: an

assessment of the livelihoods framework

approach. Crit Publ Health 2011; 21: 455–69.

12 Hughes R, Serebryanikova I, Donaldson K,

Leveritt M. Student food insecurity: the

skeleton in the university closet. Nutr Diet

2011; 68: 27–32.

13 Willows ND, Au V. Nutritional quality and price

of university food bank hampers. Can J Diet

Pract Res 2006; 67: 104–7.

14 VicHealth. Fact Sheet: Food Security. Melbourne:

Victorian Gov- ernment, 2007; (Available from:

http://www.vichealth.vic.gov. au/Programs-and-

Projects/Healthy-Eating.aspx, accessed 31

March 2012).

15 Australian Government. Transforming Australia’s Tertiary

Educa- tion System. Canberra: Australian

Government, 2009; (Avail- able from:

http://www.innovation.gov.au/HigherEducation/

ResourcesAndPublications/TransformingAustral

iasHigher EducationSystem/Pages/default.aspx,

accessed 14 September 2012).

16 James R, Bexley E, Delvin M, Margison S. Australian

university

student finances 2006: final report of a national survey on

students in public universities. The University of

Melbourne: Centre for the Study of Higher

Education; 2007 (Available from: http://

www.universitiesaustralia.edu.au/page/submissio

ns—reports/ commissioned-studies/student-

finances-survey/, accessed 2

May 2012).

17 Department of Education Employment &

Workplace Relations. Review of Australian Higher

Education: Final Report. Canberra: Australian

Government, 2008; (Available from:

http://www.innovation.gov.au/HigherEducation/Res

ourcesAnd

Publications/ReviewOfAustralianHigherEducatio

n/Pages/

ReviewOfAustralianHigherEducationReport.aspx,

accessed 14

September 2012).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 15

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.