Vaccination and the Law: Case Studies and Legal Frameworks

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/14

|4

|3691

|10

Report

AI Summary

This report examines the complex interplay between vaccination and the law, focusing on the rights of individuals, particularly parents, versus the interests of public health. It explores the legal frameworks surrounding mandatory vaccination, consent, and the role of case law in determining the best interests of the child. The review analyzes key court cases, such as Gillick v West Norfolk & Wisbech Area Health Authority and Department of Health and Community Services (NT) v JWB and SMB (Marion’s case), to illustrate how courts balance parental rights with the need to protect children from vaccine-preventable diseases. The report also discusses the influence of anti-vaccination lobbies, the spread of misinformation, and the ethical considerations involved in vaccination policies. Furthermore, it highlights the role of government initiatives and the importance of achieving herd immunity through effective communication and incentives. The report concludes by emphasizing the ongoing debate and the challenges of balancing individual autonomy with the collective well-being of society.

849

PROFESSIONAL

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.44, NO.11, NOVEMBER 2015© The Royal Australian College of General practitioners 2015

Vaccination and the law

Rachael Heath Jeffery

ublic immunisation programs

reduce mortality and morbidity

in vaccine-preventable diseases,

and are considered to be safe by

governments, health advocates and

practitioners. However, there is strong

opposition to their implementation from

certain lobby groups,1 resulting in a

complex interaction between regulatory

bodies, parents, lobbyists and health

practitioners. Ensuing information and

misinformation has caused many parents

to question whether vaccinating their

child is acting in the child’s best interest.

Debate on whether vaccination

should be made mandatory through

law is vexed. It centres on the rights

of the community versus those of the

individual, in particular, the individual’s

right to make decisions in the best

interest of their child. The success of

vaccination has meant near or total

eradication of serious and often fatal

childhood illnesses. Ironically, it is

this success that has led to parental

complacency and has given rise to

concern that vaccine-preventable

diseases will return.

While it remains the responsibility

of parents to make the decision on

whether to vaccinate their child, legal

disputes have arisen between the child’s

parents, and between parents and the

state. Both sides acknowledge that

vaccination carries risk, but the degree

differs markedly, and the courts have

to arbitrate while maintaining the rights

and best interest of the child in every

instance.

Background

Debate on whether vaccination should

be made mandatory through law is

vexed and centres on the rights of the

community versus those of the individual

– in particular, their right to make

decisions in the best interest of their

child.

Objective

This review examines the role that

legislation and case law play in

determining whether it is in the child’s

best interest to be protected against

vaccine-preventable diseases.

Discussion

Legislating to make vaccination

mandatory raises conflicting issues.

Legal compulsion may impinge on

a parent’s right to choose what they

consider is in the best interest of their

child. The dilemma is whether achieving

herd immunity, in particular the

protection of children against serious and

preventable diseases, justifies infringing

on these rights.

Vaccination and public

health

Ideally, governments formulate their health

policies and regulations more broadly,

and are concerned with the national

interest. They take into account the risks

to individuals, including vulnerable groups

such as children. Parents, on the other

hand, are primarily concerned with the

wellbeing of their child. Understandably,

their decision is emotional and practical

when they weigh up the risks of

vaccination versus non-vaccination.

A wealth of information on the potential

side effects of vaccination is now

available. Unfortunately, misinformation

that instils fear about purported adverse

effects can result in a decrease in

coverage rates below those required to

achieve herd immunity. Typically, vaccine-

related reactions may include fever, rash

and upper respiratory tract symptoms;

however, lowest risk reactions such as

encephalitis can understandably cause the

most alarm because of the potentially fatal

consequences.2– 4

Encouragement and incentive to

vaccinate is best enshrined in policies and

delivered through effective communication

strategies. This is countered by the view

that legal enforcement resolves all those

cases where the parent is apathetic, plus

the law can be flexible to allow for those

who make a deliberate conscientious

objection.

Federal, state and territory governments

are concerned about the repercussions

of low vaccination rates in certain areas

and the potential of disease outbreaks,

P

PROFESSIONAL

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.44, NO.11, NOVEMBER 2015© The Royal Australian College of General practitioners 2015

Vaccination and the law

Rachael Heath Jeffery

ublic immunisation programs

reduce mortality and morbidity

in vaccine-preventable diseases,

and are considered to be safe by

governments, health advocates and

practitioners. However, there is strong

opposition to their implementation from

certain lobby groups,1 resulting in a

complex interaction between regulatory

bodies, parents, lobbyists and health

practitioners. Ensuing information and

misinformation has caused many parents

to question whether vaccinating their

child is acting in the child’s best interest.

Debate on whether vaccination

should be made mandatory through

law is vexed. It centres on the rights

of the community versus those of the

individual, in particular, the individual’s

right to make decisions in the best

interest of their child. The success of

vaccination has meant near or total

eradication of serious and often fatal

childhood illnesses. Ironically, it is

this success that has led to parental

complacency and has given rise to

concern that vaccine-preventable

diseases will return.

While it remains the responsibility

of parents to make the decision on

whether to vaccinate their child, legal

disputes have arisen between the child’s

parents, and between parents and the

state. Both sides acknowledge that

vaccination carries risk, but the degree

differs markedly, and the courts have

to arbitrate while maintaining the rights

and best interest of the child in every

instance.

Background

Debate on whether vaccination should

be made mandatory through law is

vexed and centres on the rights of the

community versus those of the individual

– in particular, their right to make

decisions in the best interest of their

child.

Objective

This review examines the role that

legislation and case law play in

determining whether it is in the child’s

best interest to be protected against

vaccine-preventable diseases.

Discussion

Legislating to make vaccination

mandatory raises conflicting issues.

Legal compulsion may impinge on

a parent’s right to choose what they

consider is in the best interest of their

child. The dilemma is whether achieving

herd immunity, in particular the

protection of children against serious and

preventable diseases, justifies infringing

on these rights.

Vaccination and public

health

Ideally, governments formulate their health

policies and regulations more broadly,

and are concerned with the national

interest. They take into account the risks

to individuals, including vulnerable groups

such as children. Parents, on the other

hand, are primarily concerned with the

wellbeing of their child. Understandably,

their decision is emotional and practical

when they weigh up the risks of

vaccination versus non-vaccination.

A wealth of information on the potential

side effects of vaccination is now

available. Unfortunately, misinformation

that instils fear about purported adverse

effects can result in a decrease in

coverage rates below those required to

achieve herd immunity. Typically, vaccine-

related reactions may include fever, rash

and upper respiratory tract symptoms;

however, lowest risk reactions such as

encephalitis can understandably cause the

most alarm because of the potentially fatal

consequences.2– 4

Encouragement and incentive to

vaccinate is best enshrined in policies and

delivered through effective communication

strategies. This is countered by the view

that legal enforcement resolves all those

cases where the parent is apathetic, plus

the law can be flexible to allow for those

who make a deliberate conscientious

objection.

Federal, state and territory governments

are concerned about the repercussions

of low vaccination rates in certain areas

and the potential of disease outbreaks,

P

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

850

PROFESSIONAL VACCINATION AND THE LAW

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.44, NO.11, NOVEMBER 2015 © The Royal Australian College of General practitioners 2015

particularly in our increasingly mobile

population. The independent National

Health Performance Authority’s (NHPA’s)

report on childhood immunisation rates

found that despite the high percentage of

children who were fully immunised, there

was still a large number of children who

were not, or were only partly, immunised.

These cases were spread unevenly across

the country. For example, for children

aged five years, the report identified low

immunisation rates around Byron Bay

(about 67%) but high rates in the Illawarra

region (about 98%).5

Consent and the law

Until the late 20th century, common law

assumed that a person under 18 years

of age did not have the capacity to make

health decisions, including consenting

to (and by default declining) medical

treatment on their own behalf. This

position changed following the English

case Gillick v West Norfolk & Wisbech

Area Health Authority6 for determining a

child’s competence. This followed with the

High Court of Australia’s case Department

of Health and Community Services (NT)

v JWB and SMB (commonly known as

‘Marion’s case’).7

The two cases introduced the ‘mature

minor principle’, where minors (under

18 years of age) may be able to make

healthcare decisions on their own behalf

if they are assessed to be sufficiently

mature and intelligent to do so. It is in this

context that Australian courts would rule,

in assessing the best interest of the child,

whether the child refusing vaccination is

‘competent’ to make that decision.

Vaccination through case law

There have been a number of cases

in Australia and internationally where

courts have authorised the vaccination

of a child against the wishes of at least

one of the parents (Box 1). In all cases,

the judges ruled that they were acting in

the best interest of the child and based

their decision on the scientific evidence

presented, including risk assessments by

medical practitioners.

In one instance,8 the parents defied the

New South Wales Supreme Court’s order

to vaccinate and concealed the child until

the period of effectiveness had lapsed.

While the judge defended parens patriae

– the power and authority of the state to

protect persons who are unable to legally

act on their own behalf – this case shows

that monitoring compliance with the

court’s directions can present a problem,

particularly if treatments are ongoing.

Parens patriae may also empower the

courts to overturn the decisions of minors

who refuse treatment, no matter how

‘competent’ they are deemed to be.

In another case, this time in the

UK,9 two children were deemed to be

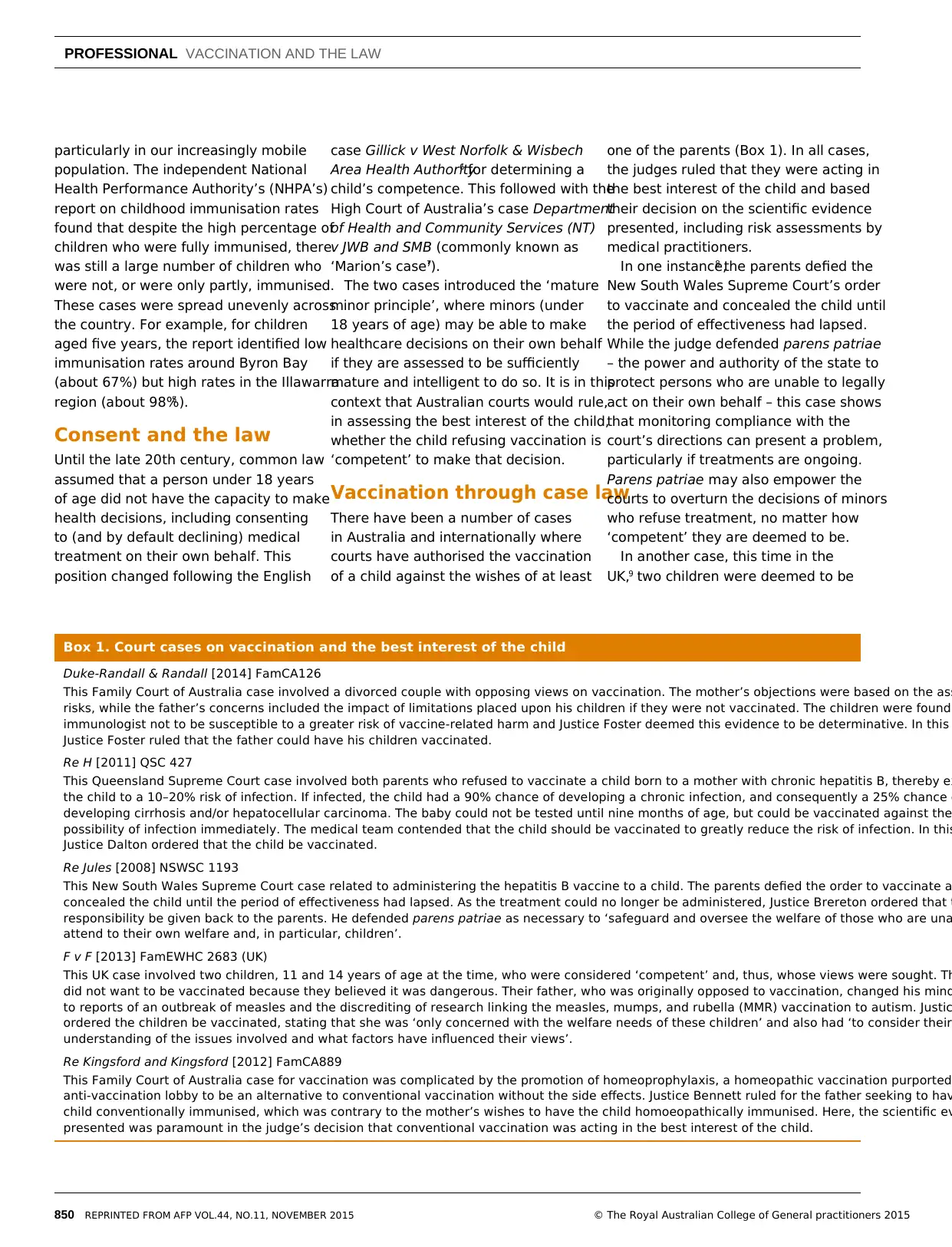

Box 1. Court cases on vaccination and the best interest of the child

Duke-Randall & Randall [2014] FamCA126

This Family Court of Australia case involved a divorced couple with opposing views on vaccination. The mother’s objections were based on the ass

risks, while the father’s concerns included the impact of limitations placed upon his children if they were not vaccinated. The children were found

immunologist not to be susceptible to a greater risk of vaccine-related harm and Justice Foster deemed this evidence to be determinative. In this

Justice Foster ruled that the father could have his children vaccinated.

Re H [2011] QSC 427

This Queensland Supreme Court case involved both parents who refused to vaccinate a child born to a mother with chronic hepatitis B, thereby ex

the child to a 10–20% risk of infection. If infected, the child had a 90% chance of developing a chronic infection, and consequently a 25% chance o

developing cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma. The baby could not be tested until nine months of age, but could be vaccinated against the

possibility of infection immediately. The medical team contended that the child should be vaccinated to greatly reduce the risk of infection. In this

Justice Dalton ordered that the child be vaccinated.

Re Jules [2008] NSWSC 1193

This New South Wales Supreme Court case related to administering the hepatitis B vaccine to a child. The parents defied the order to vaccinate a

concealed the child until the period of effectiveness had lapsed. As the treatment could no longer be administered, Justice Brereton ordered that t

responsibility be given back to the parents. He defended parens patriae as necessary to ‘safeguard and oversee the welfare of those who are una

attend to their own welfare and, in particular, children’.

F v F [2013] FamEWHC 2683 (UK)

This UK case involved two children, 11 and 14 years of age at the time, who were considered ‘competent’ and, thus, whose views were sought. Th

did not want to be vaccinated because they believed it was dangerous. Their father, who was originally opposed to vaccination, changed his mind

to reports of an outbreak of measles and the discrediting of research linking the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination to autism. Justic

ordered the children be vaccinated, stating that she was ‘only concerned with the welfare needs of these children’ and also had ‘to consider their

understanding of the issues involved and what factors have influenced their views’.

Re Kingsford and Kingsford [2012] FamCA889

This Family Court of Australia case for vaccination was complicated by the promotion of homeoprophylaxis, a homeopathic vaccination purported

anti-vaccination lobby to be an alternative to conventional vaccination without the side effects. Justice Bennett ruled for the father seeking to hav

child conventionally immunised, which was contrary to the mother’s wishes to have the child homoeopathically immunised. Here, the scientific ev

presented was paramount in the judge’s decision that conventional vaccination was acting in the best interest of the child.

PROFESSIONAL VACCINATION AND THE LAW

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.44, NO.11, NOVEMBER 2015 © The Royal Australian College of General practitioners 2015

particularly in our increasingly mobile

population. The independent National

Health Performance Authority’s (NHPA’s)

report on childhood immunisation rates

found that despite the high percentage of

children who were fully immunised, there

was still a large number of children who

were not, or were only partly, immunised.

These cases were spread unevenly across

the country. For example, for children

aged five years, the report identified low

immunisation rates around Byron Bay

(about 67%) but high rates in the Illawarra

region (about 98%).5

Consent and the law

Until the late 20th century, common law

assumed that a person under 18 years

of age did not have the capacity to make

health decisions, including consenting

to (and by default declining) medical

treatment on their own behalf. This

position changed following the English

case Gillick v West Norfolk & Wisbech

Area Health Authority6 for determining a

child’s competence. This followed with the

High Court of Australia’s case Department

of Health and Community Services (NT)

v JWB and SMB (commonly known as

‘Marion’s case’).7

The two cases introduced the ‘mature

minor principle’, where minors (under

18 years of age) may be able to make

healthcare decisions on their own behalf

if they are assessed to be sufficiently

mature and intelligent to do so. It is in this

context that Australian courts would rule,

in assessing the best interest of the child,

whether the child refusing vaccination is

‘competent’ to make that decision.

Vaccination through case law

There have been a number of cases

in Australia and internationally where

courts have authorised the vaccination

of a child against the wishes of at least

one of the parents (Box 1). In all cases,

the judges ruled that they were acting in

the best interest of the child and based

their decision on the scientific evidence

presented, including risk assessments by

medical practitioners.

In one instance,8 the parents defied the

New South Wales Supreme Court’s order

to vaccinate and concealed the child until

the period of effectiveness had lapsed.

While the judge defended parens patriae

– the power and authority of the state to

protect persons who are unable to legally

act on their own behalf – this case shows

that monitoring compliance with the

court’s directions can present a problem,

particularly if treatments are ongoing.

Parens patriae may also empower the

courts to overturn the decisions of minors

who refuse treatment, no matter how

‘competent’ they are deemed to be.

In another case, this time in the

UK,9 two children were deemed to be

Box 1. Court cases on vaccination and the best interest of the child

Duke-Randall & Randall [2014] FamCA126

This Family Court of Australia case involved a divorced couple with opposing views on vaccination. The mother’s objections were based on the ass

risks, while the father’s concerns included the impact of limitations placed upon his children if they were not vaccinated. The children were found

immunologist not to be susceptible to a greater risk of vaccine-related harm and Justice Foster deemed this evidence to be determinative. In this

Justice Foster ruled that the father could have his children vaccinated.

Re H [2011] QSC 427

This Queensland Supreme Court case involved both parents who refused to vaccinate a child born to a mother with chronic hepatitis B, thereby ex

the child to a 10–20% risk of infection. If infected, the child had a 90% chance of developing a chronic infection, and consequently a 25% chance o

developing cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma. The baby could not be tested until nine months of age, but could be vaccinated against the

possibility of infection immediately. The medical team contended that the child should be vaccinated to greatly reduce the risk of infection. In this

Justice Dalton ordered that the child be vaccinated.

Re Jules [2008] NSWSC 1193

This New South Wales Supreme Court case related to administering the hepatitis B vaccine to a child. The parents defied the order to vaccinate a

concealed the child until the period of effectiveness had lapsed. As the treatment could no longer be administered, Justice Brereton ordered that t

responsibility be given back to the parents. He defended parens patriae as necessary to ‘safeguard and oversee the welfare of those who are una

attend to their own welfare and, in particular, children’.

F v F [2013] FamEWHC 2683 (UK)

This UK case involved two children, 11 and 14 years of age at the time, who were considered ‘competent’ and, thus, whose views were sought. Th

did not want to be vaccinated because they believed it was dangerous. Their father, who was originally opposed to vaccination, changed his mind

to reports of an outbreak of measles and the discrediting of research linking the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination to autism. Justic

ordered the children be vaccinated, stating that she was ‘only concerned with the welfare needs of these children’ and also had ‘to consider their

understanding of the issues involved and what factors have influenced their views’.

Re Kingsford and Kingsford [2012] FamCA889

This Family Court of Australia case for vaccination was complicated by the promotion of homeoprophylaxis, a homeopathic vaccination purported

anti-vaccination lobby to be an alternative to conventional vaccination without the side effects. Justice Bennett ruled for the father seeking to hav

child conventionally immunised, which was contrary to the mother’s wishes to have the child homoeopathically immunised. Here, the scientific ev

presented was paramount in the judge’s decision that conventional vaccination was acting in the best interest of the child.

851

VACCINATION AND THE LAW PROFESSIONAL

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.44, NO.11, NOVEMBER 2015© The Royal Australian College of General practitioners 2015

‘competent’ as they possessed the

necessary reasoning abilities to have

their views against vaccination taken into

account. However, the judge decided

for vaccination, stating she was ‘only

concerned with the welfare needs of

these children’. A decision by an Australian

court in this instance would be guided by

the Gillick and Marion cases.

In early 2015, the gulf between pro-

and anti-vaccination groups was again

illustrated in a German regional court. It

decided for a doctor claiming a reward

from a biologist who had offered €100,000

for scientific evidence proving the measles

virus, but then refused to pay.10

Anti-vaccination lobby

Anti-vaccinationists have existed for as

long as vaccines and have always agitated

strongly against vaccination. Dr Sherri

Tenpenny regularly delivers seminars

on what she believes are the negative

impacts of vaccines on health. One of her

books was promoted as a ‘comprehensive

guide’ and explains why vaccines are

‘detrimental to yours and your child’s

health’, which she attributes to ‘vaccine

injuries’ such as autism, asthma and

autoimmune disorders.11

Dr Tenpenny has warned that ‘each

shot is a Russian roulette: you never

know which chamber has the bullet

that could kill you’.12 She argues that

adverse reactions listed in the package

inserts include encephalitis and criticises

‘deceptive research’, claiming a shot of

aluminium was used as the placebo during

a safety study with the Gardasil vaccine.11

The anti-vaccination movement has

increasingly used the internet and social

media to distribute largely unchecked,

alarmist and misleading material. It has

therefore been impossible to enforce

uniform ethical approaches from the pro-

and anti-vaccination advocates.

In some instances, courts and tribunals

have addressed the distribution of

misleading material regarding vaccination.

What remains unclear is whether the

anti-vaccination lobby is legally required

to adhere to the standards that health

professionals are, namely to conduct

themselves in a manner prescribed under

professional codes and legislation.13

Failure to comply could potentially result

in the loss of registration and/or practising

rights.14

In the New South Wales case of

Australian Vaccination Network Inc v

Health Care Complaints Commission,

Justice Adamson ordered that it was not

within the Commission’s jurisdiction15,16

to issue a public warning against the

Australian Vaccination Network in relation

to ‘engaging in misleading or deceptive

conduct in order to dissuade people

from being, or having their children,

vaccinated’.17 However, in February 2014,

following a jurisdictional change in the

law, the New South Wales Administrative

Decisions Tribunal upheld an order from

the Office of Fair Trading for the Australian

Vaccination Network to change its name

to the Australian Vaccination-Sceptics

Network to more accurately reflect the

advice it dispenses.

Federal, state and territory

vaccination initiatives

The Australian Government is

implementing its National Immunisation

Strategy for Australia 2013–2018 through a

set of strategic priorities,18 which includes:

• improving immunisation coverage

through secure and efficient supply of

vaccines

• community confidence

• a skilled immunisation workforce

• effective monitoring and analysis of

results.

Essential vaccines are provided free

of charge to eligible infants, children,

adolescents and adults, meeting

international goals set by the World Health

Organization. Vaccinations are monitored

under the independent NHPA, which was

set up under the National Health Reform

Act 2011. Program funding agreements

between governments are set up under

the National Partnership Agreement on

Essential Vaccines.18

State and territory governments are

instituting more requirements to ensure

children are vaccinated. In New South

Wales, the Public Health Act 2010 was

amended so that from 1 January 2014,

before enrolment at a childcare facility,

a parent/guardian is required to show

that their child is fully vaccinated for

their age, has a medical reason not to

be vaccinated or is on a recognised

catch-up schedule for their vaccinations.

Otherwise, they have to declare a

conscientious objection to vaccination.19

This followed prolonged measles

outbreaks in 2011 and 2013, and a

subsequent ‘No Jab No Play’ campaign,

which resulted from findings that some

communities in New South Wales had

vaccination rates under 50%.20 The

Queensland Government has announced

its intention to introduce similar

legislation in 2015. At the federal level,

vaccination eligibility requirements have

been introduced for entitlements such as

Family Tax Benefit B.

Compulsory vaccination has been

effective in preventing disease outbreaks,

and as such justifies government

intervention.21 However, debate on

mandatory vaccination must be open

and factual.22–24 Official exemptions

on various grounds address protests

regarding the ‘nanny state’ levelled

against governments; however,

exemption rates as low as 2% can

increase a community’s risk of disease

outbreaks, depending on the disease.

Fortunately, in the case of rotavirus, 80%

coverage resulted in significant herd

immunity and subsequent decrease in

hospitalisations.25

In accordance with legislation and case

law, it is in a child’s best interest to be

protected against vaccine-preventable

disease. It is also in the community’s

best interest that children are protected

against outbreak and spread of

disease. To date, this is best achieved

through programs that are accessible,

well communicated and supported

by law, so that parents can make

informed decisions. It also counters

the misinformation distributed by those

opposed to vaccination.

VACCINATION AND THE LAW PROFESSIONAL

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.44, NO.11, NOVEMBER 2015© The Royal Australian College of General practitioners 2015

‘competent’ as they possessed the

necessary reasoning abilities to have

their views against vaccination taken into

account. However, the judge decided

for vaccination, stating she was ‘only

concerned with the welfare needs of

these children’. A decision by an Australian

court in this instance would be guided by

the Gillick and Marion cases.

In early 2015, the gulf between pro-

and anti-vaccination groups was again

illustrated in a German regional court. It

decided for a doctor claiming a reward

from a biologist who had offered €100,000

for scientific evidence proving the measles

virus, but then refused to pay.10

Anti-vaccination lobby

Anti-vaccinationists have existed for as

long as vaccines and have always agitated

strongly against vaccination. Dr Sherri

Tenpenny regularly delivers seminars

on what she believes are the negative

impacts of vaccines on health. One of her

books was promoted as a ‘comprehensive

guide’ and explains why vaccines are

‘detrimental to yours and your child’s

health’, which she attributes to ‘vaccine

injuries’ such as autism, asthma and

autoimmune disorders.11

Dr Tenpenny has warned that ‘each

shot is a Russian roulette: you never

know which chamber has the bullet

that could kill you’.12 She argues that

adverse reactions listed in the package

inserts include encephalitis and criticises

‘deceptive research’, claiming a shot of

aluminium was used as the placebo during

a safety study with the Gardasil vaccine.11

The anti-vaccination movement has

increasingly used the internet and social

media to distribute largely unchecked,

alarmist and misleading material. It has

therefore been impossible to enforce

uniform ethical approaches from the pro-

and anti-vaccination advocates.

In some instances, courts and tribunals

have addressed the distribution of

misleading material regarding vaccination.

What remains unclear is whether the

anti-vaccination lobby is legally required

to adhere to the standards that health

professionals are, namely to conduct

themselves in a manner prescribed under

professional codes and legislation.13

Failure to comply could potentially result

in the loss of registration and/or practising

rights.14

In the New South Wales case of

Australian Vaccination Network Inc v

Health Care Complaints Commission,

Justice Adamson ordered that it was not

within the Commission’s jurisdiction15,16

to issue a public warning against the

Australian Vaccination Network in relation

to ‘engaging in misleading or deceptive

conduct in order to dissuade people

from being, or having their children,

vaccinated’.17 However, in February 2014,

following a jurisdictional change in the

law, the New South Wales Administrative

Decisions Tribunal upheld an order from

the Office of Fair Trading for the Australian

Vaccination Network to change its name

to the Australian Vaccination-Sceptics

Network to more accurately reflect the

advice it dispenses.

Federal, state and territory

vaccination initiatives

The Australian Government is

implementing its National Immunisation

Strategy for Australia 2013–2018 through a

set of strategic priorities,18 which includes:

• improving immunisation coverage

through secure and efficient supply of

vaccines

• community confidence

• a skilled immunisation workforce

• effective monitoring and analysis of

results.

Essential vaccines are provided free

of charge to eligible infants, children,

adolescents and adults, meeting

international goals set by the World Health

Organization. Vaccinations are monitored

under the independent NHPA, which was

set up under the National Health Reform

Act 2011. Program funding agreements

between governments are set up under

the National Partnership Agreement on

Essential Vaccines.18

State and territory governments are

instituting more requirements to ensure

children are vaccinated. In New South

Wales, the Public Health Act 2010 was

amended so that from 1 January 2014,

before enrolment at a childcare facility,

a parent/guardian is required to show

that their child is fully vaccinated for

their age, has a medical reason not to

be vaccinated or is on a recognised

catch-up schedule for their vaccinations.

Otherwise, they have to declare a

conscientious objection to vaccination.19

This followed prolonged measles

outbreaks in 2011 and 2013, and a

subsequent ‘No Jab No Play’ campaign,

which resulted from findings that some

communities in New South Wales had

vaccination rates under 50%.20 The

Queensland Government has announced

its intention to introduce similar

legislation in 2015. At the federal level,

vaccination eligibility requirements have

been introduced for entitlements such as

Family Tax Benefit B.

Compulsory vaccination has been

effective in preventing disease outbreaks,

and as such justifies government

intervention.21 However, debate on

mandatory vaccination must be open

and factual.22–24 Official exemptions

on various grounds address protests

regarding the ‘nanny state’ levelled

against governments; however,

exemption rates as low as 2% can

increase a community’s risk of disease

outbreaks, depending on the disease.

Fortunately, in the case of rotavirus, 80%

coverage resulted in significant herd

immunity and subsequent decrease in

hospitalisations.25

In accordance with legislation and case

law, it is in a child’s best interest to be

protected against vaccine-preventable

disease. It is also in the community’s

best interest that children are protected

against outbreak and spread of

disease. To date, this is best achieved

through programs that are accessible,

well communicated and supported

by law, so that parents can make

informed decisions. It also counters

the misinformation distributed by those

opposed to vaccination.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

852

PROFESSIONAL VACCINATION AND THE LAW

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.44, NO.11, NOVEMBER 2015 © The Royal Australian College of General practitioners 2015

Since this article’s submission, from 1

January 2016, conscientious objection will

be removed as an exemption category for

the Child Care Benefit, Child Care Rebate

and Family Tax Benefit Part A end of year

supplement.26 Existing exemptions on

medical or religious grounds will still apply

with the correct approval. Importantly,

immunisation requirements for payments

will also be extended to include children

of all ages except those under 12 months

(based on early childhood immunisation

status).26

Key points

• Vaccination reduces mortality and

morbidity in vaccine-preventable

diseases.

• Debate centres on the rights of the

community versus those of the

individual.

• Misinformation can result in a decrease

in coverage rates required for herd

immunity.

• A large number of children are not, or

are only partly, immunised, and these

cases are spread unevenly across

Australia.

• Courts have authorised the vaccination

of a child against the wishes of at least

one of the parents, in all cases acting in

the best interest of the child.

• The anti-vaccination movement has

distributed misinformation and it is

unclear whether it is legally required

to adhere to the same standards that

apply to health professionals.

• The National Immunisation Strategy for

Australia 2013–2018 sets out strategic

priorities and meets international goals

set by the World Health Organization.

• On 1 January 2014, New South Wales

legislated requirements to ensure

children are appropriately vaccinated

before enrolment at a childcare facility.

Author

Rachael C Heath Jeffery BAppSc (Hons), medical

student, Australian National University Medical

School, Canberra, ACT. u4535769@anu.edu.au

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned,

externally peer reviewed.

References

1. Vines T, Faunce T. Civil liberties and the critics

of safe vaccination: Australian Vaccination

Network Inc v Health Care Complaints

Commission [2012] NSWSC 110. J Law Med

2012;20:44–58.

2. Peltola H, Hemonen OP. Frequency of true

adverse reactions to measles-mumps-rubella

vaccine. Lancet 1986;1:939–42.

3. Fenichel GM. Neurological complications of

immunization. Ann Neurol 1982;12:119–29.

4. Adetunji J. Schoolgirl dies after cervical cancer

vaccination. The Guardian 2009 September

29. Available at www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2009/

sep/28/hpv-cervical-cancer-vaccine-death

[Accessed 18 August 2014].

5. National Health Performance Authority. Healthy

Communities: Immunisation rates for children

in 2012–13. NHPA: Canberra, 2014.

6. Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health

Authority [1986] AC 112.

7. Department of Health and Community Services

(NT) v JWB and SMB (1992) 175 CLR 218.

8. Director-General, Department of Community

Services. Re Jules [2008]. NSWSC 1193:7.

9. F v F [2013] Fam EWHC 2683.

10. Bajekal N. German biologist who denied

measles exists ordered to pay more than

100,000. Time World 2015 March 13. Available

at http://time.com/3743883/german-biologist-

measles-pay [Accessed 15 March 2015].

11. Tenpenny S. Saying no to vaccines: A resource

guide for all ages. New York: NMA Media Press,

2008.

12. Tenpenny S. The ten reasons to say no to

vaccines. Vaccination Council 2011 January

9. Available at www.vaccinationcouncil.

org/2011/01/09/the-ten-reasons-to-say-no-to-

vaccines [Accessed 10 February 2015].

13. Health Practitioner Regulation National Law,

s 139B(1)(a)(i), adopted by New South Wales

through the Health Practitioner Regulation

(Adoption of National Law) Act 2009 (NSW).

14. Health Practitioner Regulation National Law

2009 (NSW), s 55.

15. The Australian Traditional-Medicine Society.

Submission to the Committee on the HCCC

Inquiry into False or Misleading Health-related

Information or Practices. December 2013.

16. Australian Vaccination Network Inc v Health

Care Complaints Commission [2012] NSWSC

110.

17. Evans L, HCCC investigator. Investigation report

regarding the Australian Vaccination Network.

Ms Meryl Dorey (File No 09/01695 & 10/00002)

(7 July 2010) p 2 (Investigation Report).

Available at www.stopavn.com/documents/

HCCC-Report.pdf [Accessed 31 August 2014].

18. Department of Health. National Immunisation

Strategy for Australia 2013–2018. Canberra:

Department of Health, 2013.

19. Public Health Amendment (Vaccination of

Children Attending Child Care Facilities) Act

2013 (NSW Bills) No 127.

20. National Health Performance Authority. Healthy

communities: Immunisation rates for children in

2011–12. Canberra: NHPA, 2013.

21. Salmon DA, Teret SP, MacIntyre CR, et al.

Compulsory vaccination and conscientious or

philosophical exemptions: Past, present, and

future. Lancet 2006;367:436–42.

22. Javitt G, Berkowitz D, Gostin LO. Assessing

mandatory HPV vaccination: Who should call the

shots? J Law Med Ethics 2008;36:384–95.

23. Regan DG, Philp DJ, Hocking JS, et al. Modeling

the population-level impact of vaccination on the

transmission of human papillomavirus type 16 in

Australia. Sex Health 2007;4:147–63.

24. Zimmerman RK. Ethical analysis of HPV vaccine

policy options. Vaccine 2006;24:4812–20.

25. Dey A, Wang H, Menzies R, Macartney

K. Changes in hospitalisations for acute

gastroenteritis in Australia after the national

rotavirus vaccination program. Med J Aust

2012;197:453–57.

26. Australian Government Department of

Social Services. Strengthening immunisation

requirements: Fact sheet. Canberra: 2015.

Available at www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/

files/documents/04_2015/immunisation_fact_

sheet_-_12_april_2015.docx [Accessed 14

September 2015].

PROFESSIONAL VACCINATION AND THE LAW

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.44, NO.11, NOVEMBER 2015 © The Royal Australian College of General practitioners 2015

Since this article’s submission, from 1

January 2016, conscientious objection will

be removed as an exemption category for

the Child Care Benefit, Child Care Rebate

and Family Tax Benefit Part A end of year

supplement.26 Existing exemptions on

medical or religious grounds will still apply

with the correct approval. Importantly,

immunisation requirements for payments

will also be extended to include children

of all ages except those under 12 months

(based on early childhood immunisation

status).26

Key points

• Vaccination reduces mortality and

morbidity in vaccine-preventable

diseases.

• Debate centres on the rights of the

community versus those of the

individual.

• Misinformation can result in a decrease

in coverage rates required for herd

immunity.

• A large number of children are not, or

are only partly, immunised, and these

cases are spread unevenly across

Australia.

• Courts have authorised the vaccination

of a child against the wishes of at least

one of the parents, in all cases acting in

the best interest of the child.

• The anti-vaccination movement has

distributed misinformation and it is

unclear whether it is legally required

to adhere to the same standards that

apply to health professionals.

• The National Immunisation Strategy for

Australia 2013–2018 sets out strategic

priorities and meets international goals

set by the World Health Organization.

• On 1 January 2014, New South Wales

legislated requirements to ensure

children are appropriately vaccinated

before enrolment at a childcare facility.

Author

Rachael C Heath Jeffery BAppSc (Hons), medical

student, Australian National University Medical

School, Canberra, ACT. u4535769@anu.edu.au

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned,

externally peer reviewed.

References

1. Vines T, Faunce T. Civil liberties and the critics

of safe vaccination: Australian Vaccination

Network Inc v Health Care Complaints

Commission [2012] NSWSC 110. J Law Med

2012;20:44–58.

2. Peltola H, Hemonen OP. Frequency of true

adverse reactions to measles-mumps-rubella

vaccine. Lancet 1986;1:939–42.

3. Fenichel GM. Neurological complications of

immunization. Ann Neurol 1982;12:119–29.

4. Adetunji J. Schoolgirl dies after cervical cancer

vaccination. The Guardian 2009 September

29. Available at www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2009/

sep/28/hpv-cervical-cancer-vaccine-death

[Accessed 18 August 2014].

5. National Health Performance Authority. Healthy

Communities: Immunisation rates for children

in 2012–13. NHPA: Canberra, 2014.

6. Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health

Authority [1986] AC 112.

7. Department of Health and Community Services

(NT) v JWB and SMB (1992) 175 CLR 218.

8. Director-General, Department of Community

Services. Re Jules [2008]. NSWSC 1193:7.

9. F v F [2013] Fam EWHC 2683.

10. Bajekal N. German biologist who denied

measles exists ordered to pay more than

100,000. Time World 2015 March 13. Available

at http://time.com/3743883/german-biologist-

measles-pay [Accessed 15 March 2015].

11. Tenpenny S. Saying no to vaccines: A resource

guide for all ages. New York: NMA Media Press,

2008.

12. Tenpenny S. The ten reasons to say no to

vaccines. Vaccination Council 2011 January

9. Available at www.vaccinationcouncil.

org/2011/01/09/the-ten-reasons-to-say-no-to-

vaccines [Accessed 10 February 2015].

13. Health Practitioner Regulation National Law,

s 139B(1)(a)(i), adopted by New South Wales

through the Health Practitioner Regulation

(Adoption of National Law) Act 2009 (NSW).

14. Health Practitioner Regulation National Law

2009 (NSW), s 55.

15. The Australian Traditional-Medicine Society.

Submission to the Committee on the HCCC

Inquiry into False or Misleading Health-related

Information or Practices. December 2013.

16. Australian Vaccination Network Inc v Health

Care Complaints Commission [2012] NSWSC

110.

17. Evans L, HCCC investigator. Investigation report

regarding the Australian Vaccination Network.

Ms Meryl Dorey (File No 09/01695 & 10/00002)

(7 July 2010) p 2 (Investigation Report).

Available at www.stopavn.com/documents/

HCCC-Report.pdf [Accessed 31 August 2014].

18. Department of Health. National Immunisation

Strategy for Australia 2013–2018. Canberra:

Department of Health, 2013.

19. Public Health Amendment (Vaccination of

Children Attending Child Care Facilities) Act

2013 (NSW Bills) No 127.

20. National Health Performance Authority. Healthy

communities: Immunisation rates for children in

2011–12. Canberra: NHPA, 2013.

21. Salmon DA, Teret SP, MacIntyre CR, et al.

Compulsory vaccination and conscientious or

philosophical exemptions: Past, present, and

future. Lancet 2006;367:436–42.

22. Javitt G, Berkowitz D, Gostin LO. Assessing

mandatory HPV vaccination: Who should call the

shots? J Law Med Ethics 2008;36:384–95.

23. Regan DG, Philp DJ, Hocking JS, et al. Modeling

the population-level impact of vaccination on the

transmission of human papillomavirus type 16 in

Australia. Sex Health 2007;4:147–63.

24. Zimmerman RK. Ethical analysis of HPV vaccine

policy options. Vaccine 2006;24:4812–20.

25. Dey A, Wang H, Menzies R, Macartney

K. Changes in hospitalisations for acute

gastroenteritis in Australia after the national

rotavirus vaccination program. Med J Aust

2012;197:453–57.

26. Australian Government Department of

Social Services. Strengthening immunisation

requirements: Fact sheet. Canberra: 2015.

Available at www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/

files/documents/04_2015/immunisation_fact_

sheet_-_12_april_2015.docx [Accessed 14

September 2015].

1 out of 4

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.