Report: Parental Attitudes on Childhood Vaccinations in Australia

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/14

|7

|5431

|12

Report

AI Summary

This report presents the findings of a national online survey conducted in Australia in 2012, investigating parental attitudes, behaviors, and concerns regarding childhood vaccinations. The study aimed to describe parental views, identify factors associated with non-compliance with the National Immunisation Program Schedule (NIPS), and determine the primary sources of vaccination information. The survey included 452 parents of children under 18 years old, revealing that while 92% reported their children as up-to-date with vaccinations, 52% still had concerns. Key findings indicated that disagreeing with the safety of vaccines and obtaining information from alternative health practitioners were associated with non-compliance. General practitioners (GPs) were identified as the most influential source of vaccination information. The report emphasizes the crucial role of GPs in addressing parental concerns and improving vaccination compliance through education and communication. The study also highlights the public health implications of vaccine hesitancy and the importance of maintaining high vaccination coverage to prevent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.

145

RESEARCH

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.46, NO.3, MARCH 2017© The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2017

Parental attitudes, beliefs, behaviours

concerns towards childhood vaccinatio

in Australia: A national online survey

Maria Yui Kwan Chow, Margie Danchin, Harold W Willaby, Sonya Pemberton, Julie Leask

accine hesitancy is an issue of global concern in

developed and developing countries.1 MacDonald et al

characterise vaccine hesitancy as the degree of parents’

concerns regarding vaccines and vaccination, and place this on

a continuum.2 The most recent estimate for the proportion of

children affected in Australia by active vaccine refusal was 3.3%.3

However, these families are likely to represent only a portion

of vaccine-hesitant parents, with many continuing to vaccinate

according to the National Immunisation Program Schedule (NIPS)

despite having milder hesitancy than the more extreme case of

refusing all vaccines. The success of vaccination programs means

that vaccine-preventable diseases have been less frequently seen

in the past few decades. However, as outbreaks in a number of

countries attest, population immunity will be threatened if more

children do not comply with vaccination schedules.4

At present in Australia, there is high coverage for

recommended childhood vaccines. In 2012, the year that

this survey was conducted, children aged 24 months had

approximately 92.6% coverage and 1.5% of children were

affected by registered parental ‘conscientious objection’.5 Despite

this, any vaccine program is vulnerable to falls in coverage,

particularly when a vaccine safety scare arises. For example, in

the UK, the unsubstantiated measles, mumps and rubella (MMR)

autism scare led to a decline in MMR vaccination rates.6

The most recent national vaccine attitudes survey conducted

in 2001 found that the majority of parents with incompletely

immunised children (70%) were concerned about vaccine side

effects.7 This was particularly evident after the suspension of

CSL Fluvax because of a higher rate of febrile convulsions in

children. Our primary source of information regarding vaccination

uptake – the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register (ACIR)

– maintains the vaccination history of children up to seven years

of age. However, ACIR does not quantify the attitudes, beliefs

and concerns of individuals that underlie vaccination uptake and

objection.

Background and objectives

Vaccine hesitancy is a public health concern. The objectives

of this article were to describe Australian parents’ attitudes,

behaviours and concerns about vaccination, determine

the factors associated with vaccination non-compliance,

and provide sources of vaccination information for general

practitioners (GPs).

Methods

We conducted a nationally representative online survey of

Australian parents in 2012. We determined associations

between demographic and vaccination attitudes and behaviour.

Results

The 452 respondents were parents of children aged <18

years. Despite 92% reporting their child as up to date with

vaccination, 52% had concerns. Factors associated with non-

compliance included ‘disagreeing that vaccines are safe’ (odds

ratio [OR]: 2.79; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.00–7.76) and

‘obtaining information from alternative health practitioners’

(OR: 6.54; 95% CI: 1.71-25.00). The vast majority (83%) obtained

vaccination information from their GPs.

Discussion

GPs have pivotal roles in addressing concerns regarding

vaccination. Education and communication with parents will

improve their knowledge and trust in vaccination, thereby

improving vaccination compliance.

V

RESEARCH

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.46, NO.3, MARCH 2017© The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2017

Parental attitudes, beliefs, behaviours

concerns towards childhood vaccinatio

in Australia: A national online survey

Maria Yui Kwan Chow, Margie Danchin, Harold W Willaby, Sonya Pemberton, Julie Leask

accine hesitancy is an issue of global concern in

developed and developing countries.1 MacDonald et al

characterise vaccine hesitancy as the degree of parents’

concerns regarding vaccines and vaccination, and place this on

a continuum.2 The most recent estimate for the proportion of

children affected in Australia by active vaccine refusal was 3.3%.3

However, these families are likely to represent only a portion

of vaccine-hesitant parents, with many continuing to vaccinate

according to the National Immunisation Program Schedule (NIPS)

despite having milder hesitancy than the more extreme case of

refusing all vaccines. The success of vaccination programs means

that vaccine-preventable diseases have been less frequently seen

in the past few decades. However, as outbreaks in a number of

countries attest, population immunity will be threatened if more

children do not comply with vaccination schedules.4

At present in Australia, there is high coverage for

recommended childhood vaccines. In 2012, the year that

this survey was conducted, children aged 24 months had

approximately 92.6% coverage and 1.5% of children were

affected by registered parental ‘conscientious objection’.5 Despite

this, any vaccine program is vulnerable to falls in coverage,

particularly when a vaccine safety scare arises. For example, in

the UK, the unsubstantiated measles, mumps and rubella (MMR)

autism scare led to a decline in MMR vaccination rates.6

The most recent national vaccine attitudes survey conducted

in 2001 found that the majority of parents with incompletely

immunised children (70%) were concerned about vaccine side

effects.7 This was particularly evident after the suspension of

CSL Fluvax because of a higher rate of febrile convulsions in

children. Our primary source of information regarding vaccination

uptake – the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register (ACIR)

– maintains the vaccination history of children up to seven years

of age. However, ACIR does not quantify the attitudes, beliefs

and concerns of individuals that underlie vaccination uptake and

objection.

Background and objectives

Vaccine hesitancy is a public health concern. The objectives

of this article were to describe Australian parents’ attitudes,

behaviours and concerns about vaccination, determine

the factors associated with vaccination non-compliance,

and provide sources of vaccination information for general

practitioners (GPs).

Methods

We conducted a nationally representative online survey of

Australian parents in 2012. We determined associations

between demographic and vaccination attitudes and behaviour.

Results

The 452 respondents were parents of children aged <18

years. Despite 92% reporting their child as up to date with

vaccination, 52% had concerns. Factors associated with non-

compliance included ‘disagreeing that vaccines are safe’ (odds

ratio [OR]: 2.79; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.00–7.76) and

‘obtaining information from alternative health practitioners’

(OR: 6.54; 95% CI: 1.71-25.00). The vast majority (83%) obtained

vaccination information from their GPs.

Discussion

GPs have pivotal roles in addressing concerns regarding

vaccination. Education and communication with parents will

improve their knowledge and trust in vaccination, thereby

improving vaccination compliance.

V

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

146

RESEARCH CHILDHOOD VACCINATIONS

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.46, NO.3, MARCH 2017 © The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2017

Therefore, the aims of this study were to

identify Australian parents’ or caregivers’

(hereafter called ‘parents’):

• levels of support for the NIPS

• the proportion of parents with concerns

about vaccination

• use and influence of sources of

information

• associations between vaccination

attitudes and compliance with NIPS.

Methods

Study design

This study was a nationally representative

cross-sectional online survey of the

Australian general population aged ≥18

years. The survey was a collaboration

between the National Centre for

Immunisation Research and Surveillance

(NCIRS) and a documentary production

company, Genepool Productions. In this

study, we analysed data from parents of

children aged <18 years only.

Development of questionnaire

We developed a questionnaire based on

the following standardised national and

international surveys: New South Wales

Child Health Survey, New South Wales

Health Adult Health Survey, Queensland

Health Survey, US National Immunization

Healthstyles and UK Wave Survey. We were

also informed by qualitative and quantitative

research previously undertaken by the

authors of this study.8,9 Respondents were

asked if they were a parent, along with

other demographic questions. We then

identified:

• support levels for adult and childhood

vaccination

• concerns about vaccine-preventable

diseases

• perceptions about vaccine safety

• experiences in adverse events following

immunisation (AEFI)

• influenza vaccination status

• vaccination information sources and

their degree of influence on vaccination

decisions

• basic demographics.

Respondents who were current parents

of children aged <18 years answered extra

questions about vaccination attitudes,

vaccination decisions for their child,

their child’s compliance to the NIPS and

influenza vaccination status.

Sampling and data collection

An external research company, Australia

Online Research, recruited participants and

collected data. The sample was based on

an online panel of 100,000 people out of a

total of 5.3 million people who responded

to a national Australia Post survey

distributed to all Australian households.

The company sent unique invitation emails

to 9854 people using stratified sampling

methods to match the Australian census

data so that the demographic distribution

of invitees was comparable to that of the

Australian population. Each respondent

received $2 for a completed survey and

an opportunity to enter a $5000 cash prize

draw.

Australia Online Research is a member of

the Australian Market and Social Research

Society, and is required to abide by the

Code of Professional Behaviour (Code).10

Similarly to the Human Research Ethics

Committee, the Code requires the company

to have informed consent; to state that the

study is entirely voluntary and participants

can withdraw from the study at any time;

that the data collected are non-identifiable;

and that the data are stored appropriately.

Data analysis

We used SPSS 18 to analyse the data.

We generated descriptive statistics and

conducted chi-square tests of associations

between demographics and vaccination

attitudes, and between vaccination support

and compliance with the NIPS. Variables

with P values <0.25 were put into a

multivariate logistic regression model to

determine the factors associated with

vaccination support and compliance with

the NIPS.

Results

The cross-sectional online survey was

conducted between 18 and 26 April 2012.

In total, 1324 out of 9854 people completed

the survey (13.4%), of whom, 452 (34%)

were parents with children <18 years of

age. Forty-four per cent of respondents

were aged between 35 and 44 years; 43%

had a university degree; 392 (87%) were

primary caregivers; and 51% were female.

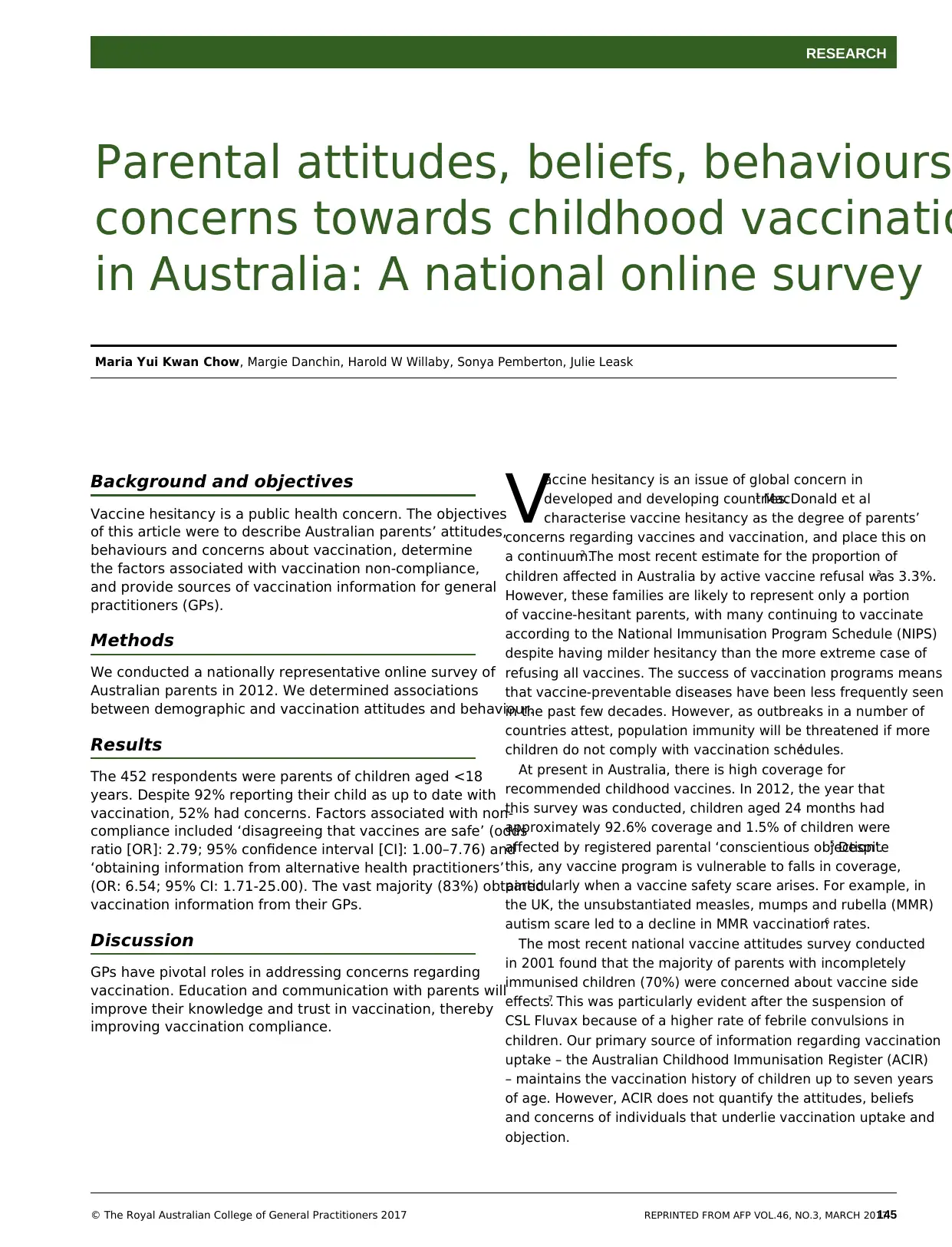

Table 1 shows the demographics of the

respondents and those of the Australian

population. The demographics of the parent

respondents were not significantly different

from those in the Australian population.

According to parental reports for their

youngest child, 92% were fully immunised

according to the NIPS, 6% were under-

immunised or unimmunised and 2% were

unsure. For the influenza vaccine, 23%

indicated that their child received the

vaccine in 2011 and 13% of parents recalled

having a family member or a friend who

previously reported an AEFI (any type of

vaccine).

The vast majority of parents were

supportive of vaccination in children: 68%

strongly support, 26% generally support,

2% neutral, 2% generally oppose and

2% strongly oppose. When asked about

vaccination decisions for their youngest

child, 48% allowed their child to receive all

recommended vaccines with no concerns;

38% allowed for all vaccines but with few

concerns; 6% allowed for all vaccines but

with several concerns; 6% allowed some

vaccines only or to delay some; and 2% did

not allow their child to have any vaccines.

Parents’ perceptions towards vaccine-

preventable diseases varied. More than half

were very (26%) or fairly (27%) concerned,

35% were somewhat concerned and 12%

were not concerned. Perceptions towards

vaccine-preventable diseases did not differ

across primary and non-primary caregivers

(P: 0.49), nor across respondent age,

gender or education levels. Table 2 shows

parental attitudes towards vaccination.

While 90% of parents agreed that

vaccinations were safe for children, 23%

were concerned that vaccines were not

tested enough for safety, 21% believed that

vaccines could cause autism and 22% were

also concerned that their child’s immune

system could be weakened by vaccinations.

The vast majority of parents obtained

information from their general practitioner

RESEARCH CHILDHOOD VACCINATIONS

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.46, NO.3, MARCH 2017 © The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2017

Therefore, the aims of this study were to

identify Australian parents’ or caregivers’

(hereafter called ‘parents’):

• levels of support for the NIPS

• the proportion of parents with concerns

about vaccination

• use and influence of sources of

information

• associations between vaccination

attitudes and compliance with NIPS.

Methods

Study design

This study was a nationally representative

cross-sectional online survey of the

Australian general population aged ≥18

years. The survey was a collaboration

between the National Centre for

Immunisation Research and Surveillance

(NCIRS) and a documentary production

company, Genepool Productions. In this

study, we analysed data from parents of

children aged <18 years only.

Development of questionnaire

We developed a questionnaire based on

the following standardised national and

international surveys: New South Wales

Child Health Survey, New South Wales

Health Adult Health Survey, Queensland

Health Survey, US National Immunization

Healthstyles and UK Wave Survey. We were

also informed by qualitative and quantitative

research previously undertaken by the

authors of this study.8,9 Respondents were

asked if they were a parent, along with

other demographic questions. We then

identified:

• support levels for adult and childhood

vaccination

• concerns about vaccine-preventable

diseases

• perceptions about vaccine safety

• experiences in adverse events following

immunisation (AEFI)

• influenza vaccination status

• vaccination information sources and

their degree of influence on vaccination

decisions

• basic demographics.

Respondents who were current parents

of children aged <18 years answered extra

questions about vaccination attitudes,

vaccination decisions for their child,

their child’s compliance to the NIPS and

influenza vaccination status.

Sampling and data collection

An external research company, Australia

Online Research, recruited participants and

collected data. The sample was based on

an online panel of 100,000 people out of a

total of 5.3 million people who responded

to a national Australia Post survey

distributed to all Australian households.

The company sent unique invitation emails

to 9854 people using stratified sampling

methods to match the Australian census

data so that the demographic distribution

of invitees was comparable to that of the

Australian population. Each respondent

received $2 for a completed survey and

an opportunity to enter a $5000 cash prize

draw.

Australia Online Research is a member of

the Australian Market and Social Research

Society, and is required to abide by the

Code of Professional Behaviour (Code).10

Similarly to the Human Research Ethics

Committee, the Code requires the company

to have informed consent; to state that the

study is entirely voluntary and participants

can withdraw from the study at any time;

that the data collected are non-identifiable;

and that the data are stored appropriately.

Data analysis

We used SPSS 18 to analyse the data.

We generated descriptive statistics and

conducted chi-square tests of associations

between demographics and vaccination

attitudes, and between vaccination support

and compliance with the NIPS. Variables

with P values <0.25 were put into a

multivariate logistic regression model to

determine the factors associated with

vaccination support and compliance with

the NIPS.

Results

The cross-sectional online survey was

conducted between 18 and 26 April 2012.

In total, 1324 out of 9854 people completed

the survey (13.4%), of whom, 452 (34%)

were parents with children <18 years of

age. Forty-four per cent of respondents

were aged between 35 and 44 years; 43%

had a university degree; 392 (87%) were

primary caregivers; and 51% were female.

Table 1 shows the demographics of the

respondents and those of the Australian

population. The demographics of the parent

respondents were not significantly different

from those in the Australian population.

According to parental reports for their

youngest child, 92% were fully immunised

according to the NIPS, 6% were under-

immunised or unimmunised and 2% were

unsure. For the influenza vaccine, 23%

indicated that their child received the

vaccine in 2011 and 13% of parents recalled

having a family member or a friend who

previously reported an AEFI (any type of

vaccine).

The vast majority of parents were

supportive of vaccination in children: 68%

strongly support, 26% generally support,

2% neutral, 2% generally oppose and

2% strongly oppose. When asked about

vaccination decisions for their youngest

child, 48% allowed their child to receive all

recommended vaccines with no concerns;

38% allowed for all vaccines but with few

concerns; 6% allowed for all vaccines but

with several concerns; 6% allowed some

vaccines only or to delay some; and 2% did

not allow their child to have any vaccines.

Parents’ perceptions towards vaccine-

preventable diseases varied. More than half

were very (26%) or fairly (27%) concerned,

35% were somewhat concerned and 12%

were not concerned. Perceptions towards

vaccine-preventable diseases did not differ

across primary and non-primary caregivers

(P: 0.49), nor across respondent age,

gender or education levels. Table 2 shows

parental attitudes towards vaccination.

While 90% of parents agreed that

vaccinations were safe for children, 23%

were concerned that vaccines were not

tested enough for safety, 21% believed that

vaccines could cause autism and 22% were

also concerned that their child’s immune

system could be weakened by vaccinations.

The vast majority of parents obtained

information from their general practitioner

147

CHILDHOOD VACCINATIONS RESEARCH

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.46, NO.3, MARCH 2017© The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2017

n = 99). Respondents who were not

confident with the information provided by

their healthcare provider were significantly

more likely to obtain information from the

internet (52% versus 24%; P <0.001).

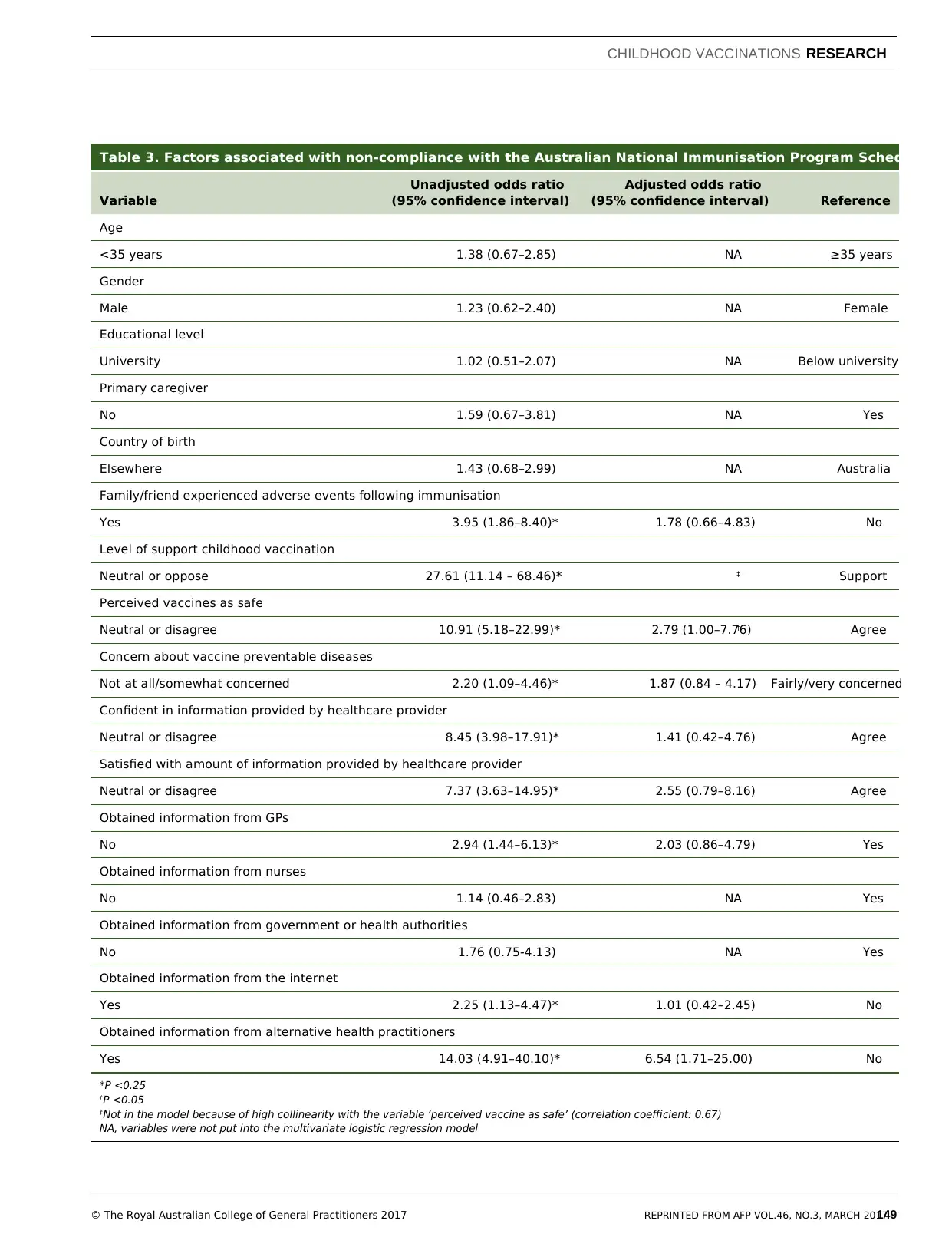

Factors that were found to be associated

with non-compliance with the NIPS

included disagreeing that vaccines are safe

(OR: 2.79; 95% CI: 1.00–7.76; P: 0.049)

and obtaining vaccination information from

alternative health practitioners (OR: 6.54;

95% CI: 1.71–25.00; P: 0.006; Table 3).

Discussion

This study has a number of significant

findings. The vast majority of parents

were supportive of childhood vaccination,

although a considerable proportion

expressed concerns related to the safety of

vaccines. GPs were still the main source of

vaccination information and found to be the

most influential. The strongest associations

with NIPS non-compliance were viewing

vaccines as unsafe and obtaining information

from alternative health practitioners.

The proportion of NIPS-compliant children

in our study is similar to that in ACIR for

children aged 24 months, as well as another

Australian national survey of vaccine

coverage conducted in 2011 (92%).11,12

Vaccination decisions of parents in Australia

are also comparable to those in the US,

which has a 2% parental refusal rate for

childhood vaccines.13 Despite having no

impact on vaccine compliance, more than

one-fifth of our study respondents were

concerned that vaccines caused autism in

healthy children, which was comparable to a

US national survey (25%).14

While only 2% reported having refused

all vaccines for their youngest child, 6%

described delaying or not having certain

recommended vaccines. This finding is

of concern given that people who are on

alternative vaccination schedules, where

some vaccines are delayed or omitted, have

an increased risk of contracting vaccine-

preventable diseases.13,15 A study conducted

in South Australia found that parents whose

children had experienced a suspected AEFI

were significantly more likely to report

greater concerns about vaccine safety.16

Table 1. Demographics of survey respondents

All respondents

(n = 1324)

Parents/

caregivers only

(n = 452)

Australian

population

(n = 2.2 million)

Age (years)* % % %

18–24 13 2 13

25–34 19 24 18

35–44 18 44 18

45–54 18 24 18

55–64 15 4 15

65–74 9 1 10

>75 8 1 8

Gender* % % %

Male 49 49 50

Female 51 51 50

Country of birth* % % %

Australia 75 77 73

Other countries 25 24 27

Education level† % % %

Year 12 or below 27 25 28

TAFE/trade certificate 29 31 33

Tertiary degree 43 43 38

Other 1 1 1

State of residence‡ % % %

New South Wales 34 36 32

Australian Capital Territory 2 1 2

Victoria 26 26 25

Queensland 18 14 20

Western Australia 10 11 11

South Australia 9 8 7

Northern Territory 1 0 1

Tasmania 3 3 2

*Data for Australian population as of 2011

(www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/d3310114.nsf/home/Population%20Pyramid%20-%20Australia)

†Data for Australian population as of May 2012 (Persons aged 15–64 years enrolled in a study for

qualification; www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/6227.0May%202012?OpenDocument)

‡Data for Australian population as of end of March 2012 (www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latest-

products/3235.0Main%20Features32011?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3235.0&is-

sue=2011&num=&view=)

Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding

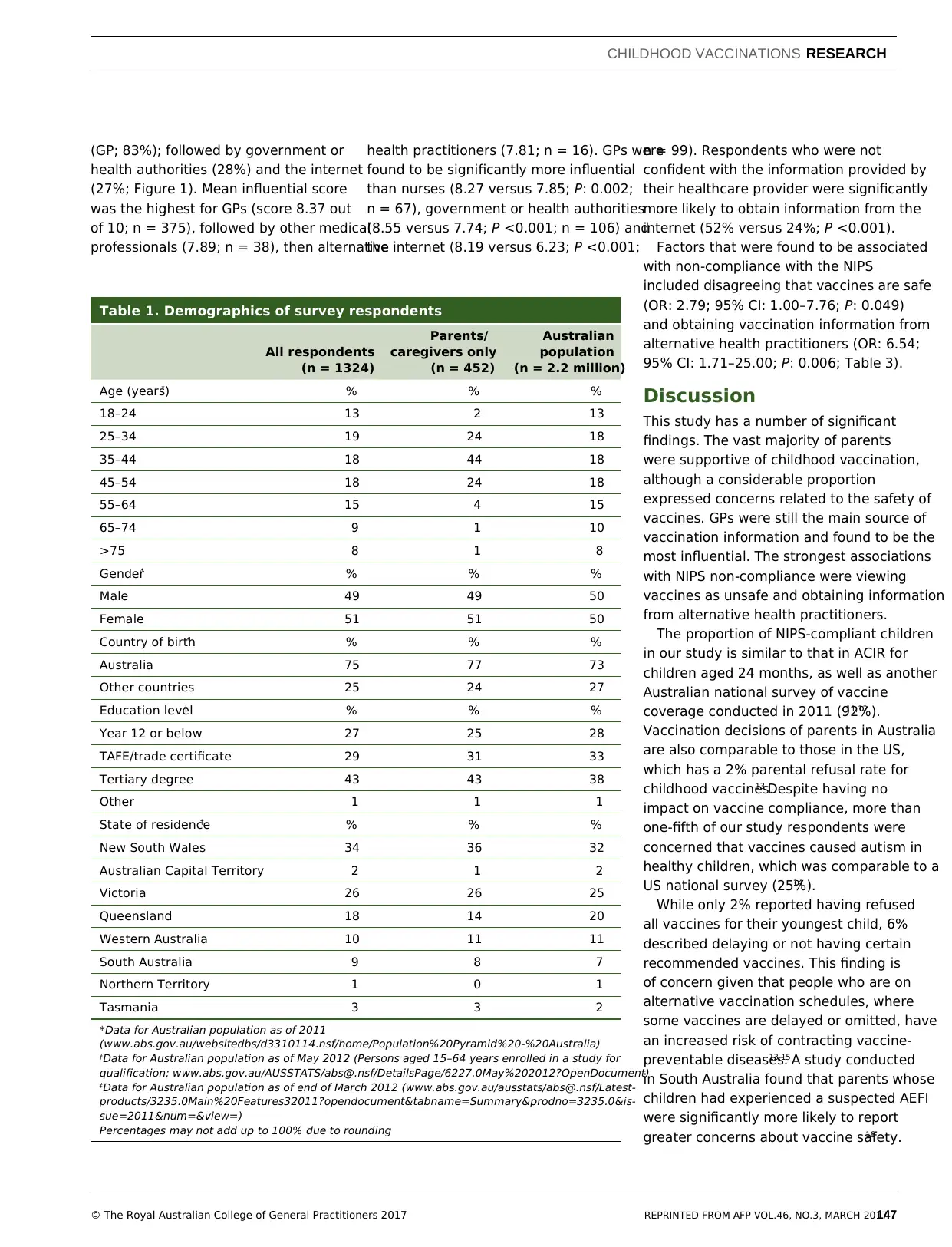

(GP; 83%); followed by government or

health authorities (28%) and the internet

(27%; Figure 1). Mean influential score

was the highest for GPs (score 8.37 out

of 10; n = 375), followed by other medical

professionals (7.89; n = 38), then alternative

health practitioners (7.81; n = 16). GPs were

found to be significantly more influential

than nurses (8.27 versus 7.85; P: 0.002;

n = 67), government or health authorities

(8.55 versus 7.74; P <0.001; n = 106) and

the internet (8.19 versus 6.23; P <0.001;

CHILDHOOD VACCINATIONS RESEARCH

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.46, NO.3, MARCH 2017© The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2017

n = 99). Respondents who were not

confident with the information provided by

their healthcare provider were significantly

more likely to obtain information from the

internet (52% versus 24%; P <0.001).

Factors that were found to be associated

with non-compliance with the NIPS

included disagreeing that vaccines are safe

(OR: 2.79; 95% CI: 1.00–7.76; P: 0.049)

and obtaining vaccination information from

alternative health practitioners (OR: 6.54;

95% CI: 1.71–25.00; P: 0.006; Table 3).

Discussion

This study has a number of significant

findings. The vast majority of parents

were supportive of childhood vaccination,

although a considerable proportion

expressed concerns related to the safety of

vaccines. GPs were still the main source of

vaccination information and found to be the

most influential. The strongest associations

with NIPS non-compliance were viewing

vaccines as unsafe and obtaining information

from alternative health practitioners.

The proportion of NIPS-compliant children

in our study is similar to that in ACIR for

children aged 24 months, as well as another

Australian national survey of vaccine

coverage conducted in 2011 (92%).11,12

Vaccination decisions of parents in Australia

are also comparable to those in the US,

which has a 2% parental refusal rate for

childhood vaccines.13 Despite having no

impact on vaccine compliance, more than

one-fifth of our study respondents were

concerned that vaccines caused autism in

healthy children, which was comparable to a

US national survey (25%).14

While only 2% reported having refused

all vaccines for their youngest child, 6%

described delaying or not having certain

recommended vaccines. This finding is

of concern given that people who are on

alternative vaccination schedules, where

some vaccines are delayed or omitted, have

an increased risk of contracting vaccine-

preventable diseases.13,15 A study conducted

in South Australia found that parents whose

children had experienced a suspected AEFI

were significantly more likely to report

greater concerns about vaccine safety.16

Table 1. Demographics of survey respondents

All respondents

(n = 1324)

Parents/

caregivers only

(n = 452)

Australian

population

(n = 2.2 million)

Age (years)* % % %

18–24 13 2 13

25–34 19 24 18

35–44 18 44 18

45–54 18 24 18

55–64 15 4 15

65–74 9 1 10

>75 8 1 8

Gender* % % %

Male 49 49 50

Female 51 51 50

Country of birth* % % %

Australia 75 77 73

Other countries 25 24 27

Education level† % % %

Year 12 or below 27 25 28

TAFE/trade certificate 29 31 33

Tertiary degree 43 43 38

Other 1 1 1

State of residence‡ % % %

New South Wales 34 36 32

Australian Capital Territory 2 1 2

Victoria 26 26 25

Queensland 18 14 20

Western Australia 10 11 11

South Australia 9 8 7

Northern Territory 1 0 1

Tasmania 3 3 2

*Data for Australian population as of 2011

(www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/d3310114.nsf/home/Population%20Pyramid%20-%20Australia)

†Data for Australian population as of May 2012 (Persons aged 15–64 years enrolled in a study for

qualification; www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/6227.0May%202012?OpenDocument)

‡Data for Australian population as of end of March 2012 (www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latest-

products/3235.0Main%20Features32011?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3235.0&is-

sue=2011&num=&view=)

Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding

(GP; 83%); followed by government or

health authorities (28%) and the internet

(27%; Figure 1). Mean influential score

was the highest for GPs (score 8.37 out

of 10; n = 375), followed by other medical

professionals (7.89; n = 38), then alternative

health practitioners (7.81; n = 16). GPs were

found to be significantly more influential

than nurses (8.27 versus 7.85; P: 0.002;

n = 67), government or health authorities

(8.55 versus 7.74; P <0.001; n = 106) and

the internet (8.19 versus 6.23; P <0.001;

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

148

RESEARCH CHILDHOOD VACCINATIONS

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.46, NO.3, MARCH 2017 © The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2017

However, our study did not find AEFI to be

related to vaccine non-compliance.

This study demonstrates the important

role GPs have in educating parents about

the risks and benefits of vaccination.

Interestingly, <20% of parents obtained

vaccination information from a nurse and,

together with government and health

authorities, they were significantly less

influential than GPs. Communication

frameworks have been developed to assist

healthcare providers to better communicate

with vaccine-hesitant parents.17,18

In medical

communication more broadly, effective

communication strategies depend on

the rapport and trust between GPs and

patients/parents. In addition, studies

have found that a recommendation to

vaccinate from a paediatric provider is

highly associated with uptake.19 However,

for parents who are not having their

children vaccinated, or hesitating to have

them vaccinated, strategies should be of a

guiding style to enable them to elicit their

own motivations to vaccinate, rather than

using a directing or debating format.17,18

GPs are increasingly likely to find parents

presenting with concerns that have been

amplified by internet searches. In this

study, internet use featured as the third

most common source for vaccination

information after ‘government or health

authorities’. Having the internet as a source

of information was associated with a lack

of confidence in information provided

by a healthcare provider. The quality and

reliability of vaccination information on the

internet can be highly variable, with easy

access to anti-vaccination websites.20 A

2012 study of US parents found those who

sought vaccine information on the internet

were more likely to have lower perceptions

of vaccine safety and have a non-medical

exemption to vaccination.21 Thus, GPs have

an important role to play in augmenting the

impact of online information.

In our study, non-compliance with the

NIPS was significantly associated with

obtaining information from alternative health

practitioners. Previous research has also

found that alternative health practitioners

were less likely to support vaccination,22,23

Table 2. Parental concerns, attitudes and behaviour towards vaccination

N = 452

Strongly agreed

or agreed with

statement (%)

I vaccinate my child to protect him/her 92

I believe that vaccinations are safe for children in general 90

I am confident in information provided by healthcare professional 89

I am satisfied with amount of information provided by healthcare

professional

85

I vaccinate my child to help protect the wider community 79

I am concerned about the distress to children of the injection itself 31

I am concerned about the increasing number of vaccines recommended

for children

25

I am concerned that vaccines are not tested enough for safety 23

I am concerned that children get too many vaccines during the first two

years of life

22

I am concerned that a child’s immune system could be weakened by

vaccinations

22

I am concerned that vaccines can cause autism in healthy children 21

I am concerned that vaccines are given to children to prevent diseases

that they are not likely to get

19

I prefer children to get natural immunity from the diseases rather than

immunity from the vaccines

16

I am concerned that vaccines are given to children to prevent diseases

that are not serious

14

Vaccination is not needed because others have vaccinated their children

and diseases have been controlled

7

Figure 1. Sources of vaccination information and its influence among parents

The bars represent the proportion of parents using the source. Multiple options could be selected,

so the total percentage is >100%. The figures above the bars represent the influential scores

(0 = Not influential to 10 = Extremely influential)

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

0%

GP or family doctor

Goverment or health authorities

Searching for interest

Brochures or medical information

Friends

Nurse

Family members

Media

Other medical professional

Other

Alternative health practitioner

Going to a library

Groups opposed to vaccination

Groups in support of vaccinations

8.37

7.75 6.41

7.19 6.55 7.73 7.53 6.08

7.89 7.65 7.81 7.79 5.62 6.36

RESEARCH CHILDHOOD VACCINATIONS

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.46, NO.3, MARCH 2017 © The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2017

However, our study did not find AEFI to be

related to vaccine non-compliance.

This study demonstrates the important

role GPs have in educating parents about

the risks and benefits of vaccination.

Interestingly, <20% of parents obtained

vaccination information from a nurse and,

together with government and health

authorities, they were significantly less

influential than GPs. Communication

frameworks have been developed to assist

healthcare providers to better communicate

with vaccine-hesitant parents.17,18

In medical

communication more broadly, effective

communication strategies depend on

the rapport and trust between GPs and

patients/parents. In addition, studies

have found that a recommendation to

vaccinate from a paediatric provider is

highly associated with uptake.19 However,

for parents who are not having their

children vaccinated, or hesitating to have

them vaccinated, strategies should be of a

guiding style to enable them to elicit their

own motivations to vaccinate, rather than

using a directing or debating format.17,18

GPs are increasingly likely to find parents

presenting with concerns that have been

amplified by internet searches. In this

study, internet use featured as the third

most common source for vaccination

information after ‘government or health

authorities’. Having the internet as a source

of information was associated with a lack

of confidence in information provided

by a healthcare provider. The quality and

reliability of vaccination information on the

internet can be highly variable, with easy

access to anti-vaccination websites.20 A

2012 study of US parents found those who

sought vaccine information on the internet

were more likely to have lower perceptions

of vaccine safety and have a non-medical

exemption to vaccination.21 Thus, GPs have

an important role to play in augmenting the

impact of online information.

In our study, non-compliance with the

NIPS was significantly associated with

obtaining information from alternative health

practitioners. Previous research has also

found that alternative health practitioners

were less likely to support vaccination,22,23

Table 2. Parental concerns, attitudes and behaviour towards vaccination

N = 452

Strongly agreed

or agreed with

statement (%)

I vaccinate my child to protect him/her 92

I believe that vaccinations are safe for children in general 90

I am confident in information provided by healthcare professional 89

I am satisfied with amount of information provided by healthcare

professional

85

I vaccinate my child to help protect the wider community 79

I am concerned about the distress to children of the injection itself 31

I am concerned about the increasing number of vaccines recommended

for children

25

I am concerned that vaccines are not tested enough for safety 23

I am concerned that children get too many vaccines during the first two

years of life

22

I am concerned that a child’s immune system could be weakened by

vaccinations

22

I am concerned that vaccines can cause autism in healthy children 21

I am concerned that vaccines are given to children to prevent diseases

that they are not likely to get

19

I prefer children to get natural immunity from the diseases rather than

immunity from the vaccines

16

I am concerned that vaccines are given to children to prevent diseases

that are not serious

14

Vaccination is not needed because others have vaccinated their children

and diseases have been controlled

7

Figure 1. Sources of vaccination information and its influence among parents

The bars represent the proportion of parents using the source. Multiple options could be selected,

so the total percentage is >100%. The figures above the bars represent the influential scores

(0 = Not influential to 10 = Extremely influential)

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

0%

GP or family doctor

Goverment or health authorities

Searching for interest

Brochures or medical information

Friends

Nurse

Family members

Media

Other medical professional

Other

Alternative health practitioner

Going to a library

Groups opposed to vaccination

Groups in support of vaccinations

8.37

7.75 6.41

7.19 6.55 7.73 7.53 6.08

7.89 7.65 7.81 7.79 5.62 6.36

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

149

CHILDHOOD VACCINATIONS RESEARCH

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.46, NO.3, MARCH 2017© The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2017

Table 3. Factors associated with non-compliance with the Australian National Immunisation Program Schedule

Variable

Unadjusted odds ratio

(95% confidence interval)

Adjusted odds ratio

(95% confidence interval) Reference

Age

<35 years 1.38 (0.67–2.85) NA ≥35 years

Gender

Male 1.23 (0.62–2.40) NA Female

Educational level

University 1.02 (0.51–2.07) NA Below university

Primary caregiver

No 1.59 (0.67–3.81) NA Yes

Country of birth

Elsewhere 1.43 (0.68–2.99) NA Australia

Family/friend experienced adverse events following immunisation

Yes 3.95 (1.86–8.40)* 1.78 (0.66–4.83) No

Level of support childhood vaccination

Neutral or oppose 27.61 (11.14 – 68.46)* ‡ Support

Perceived vaccines as safe

Neutral or disagree 10.91 (5.18–22.99)* 2.79 (1.00–7.76)† Agree

Concern about vaccine preventable diseases

Not at all/somewhat concerned 2.20 (1.09–4.46)* 1.87 (0.84 – 4.17) Fairly/very concerned

Confident in information provided by healthcare provider

Neutral or disagree 8.45 (3.98–17.91)* 1.41 (0.42–4.76) Agree

Satisfied with amount of information provided by healthcare provider

Neutral or disagree 7.37 (3.63–14.95)* 2.55 (0.79–8.16) Agree

Obtained information from GPs

No 2.94 (1.44–6.13)* 2.03 (0.86–4.79) Yes

Obtained information from nurses

No 1.14 (0.46–2.83) NA Yes

Obtained information from government or health authorities

No 1.76 (0.75-4.13) NA Yes

Obtained information from the internet

Yes 2.25 (1.13–4.47)* 1.01 (0.42–2.45) No

Obtained information from alternative health practitioners

Yes 14.03 (4.91–40.10)* 6.54 (1.71–25.00)† No

*P <0.25

† P <0.05

‡ Not in the model because of high collinearity with the variable ‘perceived vaccine as safe’ (correlation coefficient: 0.67)

NA, variables were not put into the multivariate logistic regression model

CHILDHOOD VACCINATIONS RESEARCH

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.46, NO.3, MARCH 2017© The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2017

Table 3. Factors associated with non-compliance with the Australian National Immunisation Program Schedule

Variable

Unadjusted odds ratio

(95% confidence interval)

Adjusted odds ratio

(95% confidence interval) Reference

Age

<35 years 1.38 (0.67–2.85) NA ≥35 years

Gender

Male 1.23 (0.62–2.40) NA Female

Educational level

University 1.02 (0.51–2.07) NA Below university

Primary caregiver

No 1.59 (0.67–3.81) NA Yes

Country of birth

Elsewhere 1.43 (0.68–2.99) NA Australia

Family/friend experienced adverse events following immunisation

Yes 3.95 (1.86–8.40)* 1.78 (0.66–4.83) No

Level of support childhood vaccination

Neutral or oppose 27.61 (11.14 – 68.46)* ‡ Support

Perceived vaccines as safe

Neutral or disagree 10.91 (5.18–22.99)* 2.79 (1.00–7.76)† Agree

Concern about vaccine preventable diseases

Not at all/somewhat concerned 2.20 (1.09–4.46)* 1.87 (0.84 – 4.17) Fairly/very concerned

Confident in information provided by healthcare provider

Neutral or disagree 8.45 (3.98–17.91)* 1.41 (0.42–4.76) Agree

Satisfied with amount of information provided by healthcare provider

Neutral or disagree 7.37 (3.63–14.95)* 2.55 (0.79–8.16) Agree

Obtained information from GPs

No 2.94 (1.44–6.13)* 2.03 (0.86–4.79) Yes

Obtained information from nurses

No 1.14 (0.46–2.83) NA Yes

Obtained information from government or health authorities

No 1.76 (0.75-4.13) NA Yes

Obtained information from the internet

Yes 2.25 (1.13–4.47)* 1.01 (0.42–2.45) No

Obtained information from alternative health practitioners

Yes 14.03 (4.91–40.10)* 6.54 (1.71–25.00)† No

*P <0.25

† P <0.05

‡ Not in the model because of high collinearity with the variable ‘perceived vaccine as safe’ (correlation coefficient: 0.67)

NA, variables were not put into the multivariate logistic regression model

150

RESEARCH CHILDHOOD VACCINATIONS

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.46, NO.3, MARCH 2017 © The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2017

and those who consulted alternative health

practitioners were significantly less likely

to receive recommended vaccines.24 Given

that this study is cross-sectional, we were

not able to determine whether parents

already concerned about vaccination look

to alternative health practitioners to answer

questions not addressed by their doctor, or

whether they identify more strongly with

the health model offered by alternative

health practitioners.

GPs can play a role in educating parents

and understanding their reasons for

approaching alternative health practitioners

without being judgemental. Wardle et al

also suggest disciplining health practitioners

and organisations through current legislative

arrangements for those who promote

false and misleading information about

vaccination.25 Financial incentives have been

proven to improve childhood vaccination

uptake.26 However, there is insufficient

quality evidence in relation to withholding

these payments (monetary sanctions) as a

way of improving compliance.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First,

there was a low response rate to the

initial invitation (13%) and the survey

was only weighted for the whole sample

group (n = 1324). Our study has a

higher proportion of respondents in the

35–44 years age group than in the general

population; this was expected because we

only included parents of children aged <18

years. Other than the age group distribution,

the demographics of the respondents were

comparable with the Australian population.

Second, the survey was cross-sectional; it

was not possible to determine the causal

relationship between the factors and

dependent variables. A prospective study

measuring attitudes then uptake would

provide more information on the reasons

underpinning parents’ vaccination decisions.

Third, vaccination status was ascertained

by parental report. A systematic review

found that parental recall overestimated

complete vaccination when compared

with provider records.27 Despite this,

the reported full vaccination and vaccine

objection rates were similar to nationally

reported rates (1.68% ACIR recorded

conscientious objection versus 2% in

our sample; 92.5% full compliance with

the NIPS at aged 2 years on ACIR versus

92% reporting their youngest child is fully

vaccinated in our study).28 Ideally, we

would have been able to verify individual

vaccine uptake with ACIR data – a

methodological recommendation for future

studies to pursue.

Conclusions

The majority of parents in this study

reported compliance and strong support

for the NIPS. Nevertheless, over half of

all parents or caregivers in this study

expressed some degree of concern

regarding vaccination of their child. GPs

are the most used and influential source

of information. They have a pivotal role in

communicating with parents regarding

childhood vaccinations and in providing

clear, evidence-based vaccine information

to help guide parents’ decision-making.

Implications for general

practice

Parents rely on GPs for vaccination

information more than any other

information sources. GPs can play an

active role in discussing and clarifying

parental concerns about vaccination.

They can use evidence-based vaccination

resources, such as fact sheets and

decision aids, and communication

frameworks to assist better

communication with parents.

Authors

Maria Yui Kwan Chow MIPH, PhD, Research Officer,

National Centre for Immunisation Research and

Surveillance, Kids Research Institute, The Children’s

Hospital at Westmead, Westmead, NSW; Discipline

of Paediatrics and Child Health, Sydney Medical

School, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead,

Westmead, NSW. ycho3792@uni.sydney.edu.au

Margie Danchin MBBS, FRACP, PhD, Senior Fellow,

Vaccine and Immunisation (VIRGo) and Rotavirus

Research Group, Murdoch Children’s Research

Institute, Parkville, Vic; School of Population and

Global health and Department of Paediatrics,

University of Melbourne, Parkville, Vic

Harold W Willaby BSc, MBA, PhD, Research Officer,

School of Public Health, Sydney Medical School, The

University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

Sonya Pemberton, Creative Director, Genepool

Productions, Port Melbourne, Vic

Julie Leask Dip Health Sci, MPH, PhD, Associate

Professor, National Centre for Immunisation Research

and Surveillance, Kids Research Institute, The

Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Westmead, NSW;

School of Public Health, Sydney Medical School, The

University of Sydney, Sydney NSW

Competing interests: The survey was funded by

Genepool Productions, SBS Australia and Screen

Australia with in-kind contribution from Australia

Online Research, the National Centre for Immunisation

Research and Surveillance (NCIRS). Julie Leask is

supported by a National Health and Medical Research

Council (NHMRC) Career Development Fellowship.

NCIRS is supported by the Department of Health

and Ageing, the NSW Department of Health and

the Children’s Hospital at Westmead. The data was

collected for use by the NCIRS, and to inform the

television documentary Jabbed: Love, fear and

vaccines broadcast on SBS on 26 May 2013. The

documentary can be viewed here at www.sbs.com.

au/ondemand/video/30004803525/Jabbed-Love-Fear-

And-Vaccines

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned,

externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

We would also like to thank NCIRS staff for providing

comments on data analysis.

References

1. Dube E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R,

Bettinger J. Vaccine hesitancy: An overview. Hum

Vaccin Immunother 2013;9(8):1763–73.

2. MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy:

Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine

2015;33(34):4161–64.

3. Beard FH, Hull BP, Leask J, Dey A, McIntyre PB.

Trends and patterns in vaccination objection,

Australia, 2002–2013. Med J Aust 2016;204(7):275.

4. Plotkin SA OW, Offit PA, editors. Vaccines. 6th

edn. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2013.

5. Department of Health. Immunise Australia

Program Vaccination Data. Canberra: DoH, 2015.

Available at www.immunise.health.gov.au/internet/

immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/vaccination-data

[Accessed 28 September 2016]

6. Dawson B, Apte SH. Measles outbreaks in

Australia: Obstacles to vaccination. Aust N Z J

Public Health. 2015;39(2):104–06.

7. Lawrence GL, Hull B, MacIntyre CR, McIntyre

PB. Reasons for incomplete immunisation among

Australian children: A national survey of parents.

Aust Fam Physician 2004;33(7):568–71.

8. Leask J, Chapman S, Hawe P, Burgess M. What

maintains parental support for vaccination when

challenged by anti-vaccination messages? A

qualitative study. Vaccine 2006;24(49-50):7238−45.

9. Chow MY, King C, Booy R, Leask J. Parents’

intentions and behaviour regarding seasonal

influenza vaccination for their children: A survey in

child-care centres in Sydney, Australia. J Ped Infect

Dis 2012;7(2):89–96

10. Australian Market & Social Research Society.

Code of professional behaviour. Glebe, NSW:

AMSRS, 2016. Available at www.amsrs.com.

au/professional-standards/code-of-professional-

behaviour [Accessed 1 December 2016].

RESEARCH CHILDHOOD VACCINATIONS

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.46, NO.3, MARCH 2017 © The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2017

and those who consulted alternative health

practitioners were significantly less likely

to receive recommended vaccines.24 Given

that this study is cross-sectional, we were

not able to determine whether parents

already concerned about vaccination look

to alternative health practitioners to answer

questions not addressed by their doctor, or

whether they identify more strongly with

the health model offered by alternative

health practitioners.

GPs can play a role in educating parents

and understanding their reasons for

approaching alternative health practitioners

without being judgemental. Wardle et al

also suggest disciplining health practitioners

and organisations through current legislative

arrangements for those who promote

false and misleading information about

vaccination.25 Financial incentives have been

proven to improve childhood vaccination

uptake.26 However, there is insufficient

quality evidence in relation to withholding

these payments (monetary sanctions) as a

way of improving compliance.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First,

there was a low response rate to the

initial invitation (13%) and the survey

was only weighted for the whole sample

group (n = 1324). Our study has a

higher proportion of respondents in the

35–44 years age group than in the general

population; this was expected because we

only included parents of children aged <18

years. Other than the age group distribution,

the demographics of the respondents were

comparable with the Australian population.

Second, the survey was cross-sectional; it

was not possible to determine the causal

relationship between the factors and

dependent variables. A prospective study

measuring attitudes then uptake would

provide more information on the reasons

underpinning parents’ vaccination decisions.

Third, vaccination status was ascertained

by parental report. A systematic review

found that parental recall overestimated

complete vaccination when compared

with provider records.27 Despite this,

the reported full vaccination and vaccine

objection rates were similar to nationally

reported rates (1.68% ACIR recorded

conscientious objection versus 2% in

our sample; 92.5% full compliance with

the NIPS at aged 2 years on ACIR versus

92% reporting their youngest child is fully

vaccinated in our study).28 Ideally, we

would have been able to verify individual

vaccine uptake with ACIR data – a

methodological recommendation for future

studies to pursue.

Conclusions

The majority of parents in this study

reported compliance and strong support

for the NIPS. Nevertheless, over half of

all parents or caregivers in this study

expressed some degree of concern

regarding vaccination of their child. GPs

are the most used and influential source

of information. They have a pivotal role in

communicating with parents regarding

childhood vaccinations and in providing

clear, evidence-based vaccine information

to help guide parents’ decision-making.

Implications for general

practice

Parents rely on GPs for vaccination

information more than any other

information sources. GPs can play an

active role in discussing and clarifying

parental concerns about vaccination.

They can use evidence-based vaccination

resources, such as fact sheets and

decision aids, and communication

frameworks to assist better

communication with parents.

Authors

Maria Yui Kwan Chow MIPH, PhD, Research Officer,

National Centre for Immunisation Research and

Surveillance, Kids Research Institute, The Children’s

Hospital at Westmead, Westmead, NSW; Discipline

of Paediatrics and Child Health, Sydney Medical

School, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead,

Westmead, NSW. ycho3792@uni.sydney.edu.au

Margie Danchin MBBS, FRACP, PhD, Senior Fellow,

Vaccine and Immunisation (VIRGo) and Rotavirus

Research Group, Murdoch Children’s Research

Institute, Parkville, Vic; School of Population and

Global health and Department of Paediatrics,

University of Melbourne, Parkville, Vic

Harold W Willaby BSc, MBA, PhD, Research Officer,

School of Public Health, Sydney Medical School, The

University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

Sonya Pemberton, Creative Director, Genepool

Productions, Port Melbourne, Vic

Julie Leask Dip Health Sci, MPH, PhD, Associate

Professor, National Centre for Immunisation Research

and Surveillance, Kids Research Institute, The

Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Westmead, NSW;

School of Public Health, Sydney Medical School, The

University of Sydney, Sydney NSW

Competing interests: The survey was funded by

Genepool Productions, SBS Australia and Screen

Australia with in-kind contribution from Australia

Online Research, the National Centre for Immunisation

Research and Surveillance (NCIRS). Julie Leask is

supported by a National Health and Medical Research

Council (NHMRC) Career Development Fellowship.

NCIRS is supported by the Department of Health

and Ageing, the NSW Department of Health and

the Children’s Hospital at Westmead. The data was

collected for use by the NCIRS, and to inform the

television documentary Jabbed: Love, fear and

vaccines broadcast on SBS on 26 May 2013. The

documentary can be viewed here at www.sbs.com.

au/ondemand/video/30004803525/Jabbed-Love-Fear-

And-Vaccines

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned,

externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

We would also like to thank NCIRS staff for providing

comments on data analysis.

References

1. Dube E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R,

Bettinger J. Vaccine hesitancy: An overview. Hum

Vaccin Immunother 2013;9(8):1763–73.

2. MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy:

Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine

2015;33(34):4161–64.

3. Beard FH, Hull BP, Leask J, Dey A, McIntyre PB.

Trends and patterns in vaccination objection,

Australia, 2002–2013. Med J Aust 2016;204(7):275.

4. Plotkin SA OW, Offit PA, editors. Vaccines. 6th

edn. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2013.

5. Department of Health. Immunise Australia

Program Vaccination Data. Canberra: DoH, 2015.

Available at www.immunise.health.gov.au/internet/

immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/vaccination-data

[Accessed 28 September 2016]

6. Dawson B, Apte SH. Measles outbreaks in

Australia: Obstacles to vaccination. Aust N Z J

Public Health. 2015;39(2):104–06.

7. Lawrence GL, Hull B, MacIntyre CR, McIntyre

PB. Reasons for incomplete immunisation among

Australian children: A national survey of parents.

Aust Fam Physician 2004;33(7):568–71.

8. Leask J, Chapman S, Hawe P, Burgess M. What

maintains parental support for vaccination when

challenged by anti-vaccination messages? A

qualitative study. Vaccine 2006;24(49-50):7238−45.

9. Chow MY, King C, Booy R, Leask J. Parents’

intentions and behaviour regarding seasonal

influenza vaccination for their children: A survey in

child-care centres in Sydney, Australia. J Ped Infect

Dis 2012;7(2):89–96

10. Australian Market & Social Research Society.

Code of professional behaviour. Glebe, NSW:

AMSRS, 2016. Available at www.amsrs.com.

au/professional-standards/code-of-professional-

behaviour [Accessed 1 December 2016].

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

151

CHILDHOOD VACCINATIONS RESEARCH

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.46, NO.3, MARCH 2017© The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2017

11. Berry JG, Gold MS, Ryan P, Duszynski KM,

Braunack-Mayer AJ, Vaccine Assessment Using

Linked Data Working Group. Public perspectives

on consent for the linkage of data to evaluate

vaccine safety. Vaccine 2012;30(28):4167–74.

12. Hull B, Dey A, Mahajan D, Menzies R, McIntyre

PB. Immunisation coverage annual report, 2009.

Commun Dis Intell 2011;35(2):132–48.

13. Dempsey AF, Schaffer S, Singer D, Butchart

A, Davis M, Freed GL. Alternative vaccination

schedule preferences among parents of young

children. Pediatrics 2011;128(5):848–56.

14. Freed GL, Clark SJ, Butchart AT, Singer DC, Davis

MM. Parental vaccine safety concerns in 2009.

Pediatrics 2010;125(4):654–59.

15. Rowhani-Rahbar A, Fireman B, Lewis E,

et al. Effect of age on the risk of fever and

seizures following immunization with measles-

containing vaccines in children. JAMA Pediatrics

2013;167(12):1111–17.

16. Parrella A, Gold M, Marshall H, Braunack-Mayer

A, Baghurst P. Parental perspectives of vaccine

safety and experience of adverse events following

immunisation. Vaccine 2013;31(16):2067–74.

17. Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, Cheater F,

Bedford H, Rowles G. Communicating with

parents about vaccination: A framework for health

professionals. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:154.

18. Danchin M, Nolan T. A positive approach to

parents with concerns about vaccination for

the family physician. Aust Fam Physician

2014;43(10):690–94.

19. Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Robinson JD,

Heritage J, et al. The influence of provider

communication behaviors on parental vaccine

acceptance and visit experience. Am J Pub Health

2015:e1–e7

20. Davies P, Chapman S, Leask J. Antivaccination

activists on the world wide web. Arch Dis Child

2002;87(1):22–25.

21. Jones AM, Omer SB, Bednarczyk RA, Halsey

NA, Moulton LH, Salmon DA. Parents’ source

of vaccine information and impact on vaccine

attitudes, beliefs and nonmedical exemptions. Adv

Prev Med 2012;2012:932741.

22. Busse JW, Wilson K, Campbell JB. Attitudes

towards vaccination among chiropractic and

naturopathic students. Vaccine 2008;26(49):

6237-43.

23. Schmidt K, Ernst E. MMR vaccination advice over

the internet. Vaccine 2003;21(11-12):1044−47.

24. Downey L, Tyree PT, Huebner CE, Lafferty WE.

Pediatric vaccination and vaccine-preventable

disease acquisition: Associations with care

by complementary and alternative medicine

providers. Matern Child Health J 2010;14(6):

922–30.

25. Wardle J, Stewart C, Parker M. Jabs and barbs:

Ways to address misleading vaccination and

immunisation information using currently available

strategies. J Law and Med 2013;21(1):159–78.

26. Lawrence GL, MacIntyre CR, Hull PB, McIntyre

PB. Effectiveness of the linkage of child care and

maternity payments to childhood immunisation.

Vaccine 2004;22(17–18):2345–50.

27. Miles M, Ryman TK, Dietz V, Zell E, Luman

ET. Validity of vaccination cards and parental

recall to estimate vaccination coverage: A

systematic review of the literature. Vaccine.

2013;31(12):1560–68.

28. Hull BP. Australian childhood immunisation

coverage. Commun Dis Intell 2014;38(2):E157.

CHILDHOOD VACCINATIONS RESEARCH

REPRINTED FROM AFP VOL.46, NO.3, MARCH 2017© The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2017

11. Berry JG, Gold MS, Ryan P, Duszynski KM,

Braunack-Mayer AJ, Vaccine Assessment Using

Linked Data Working Group. Public perspectives

on consent for the linkage of data to evaluate

vaccine safety. Vaccine 2012;30(28):4167–74.

12. Hull B, Dey A, Mahajan D, Menzies R, McIntyre

PB. Immunisation coverage annual report, 2009.

Commun Dis Intell 2011;35(2):132–48.

13. Dempsey AF, Schaffer S, Singer D, Butchart

A, Davis M, Freed GL. Alternative vaccination

schedule preferences among parents of young

children. Pediatrics 2011;128(5):848–56.

14. Freed GL, Clark SJ, Butchart AT, Singer DC, Davis

MM. Parental vaccine safety concerns in 2009.

Pediatrics 2010;125(4):654–59.

15. Rowhani-Rahbar A, Fireman B, Lewis E,

et al. Effect of age on the risk of fever and

seizures following immunization with measles-

containing vaccines in children. JAMA Pediatrics

2013;167(12):1111–17.

16. Parrella A, Gold M, Marshall H, Braunack-Mayer

A, Baghurst P. Parental perspectives of vaccine

safety and experience of adverse events following

immunisation. Vaccine 2013;31(16):2067–74.

17. Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, Cheater F,

Bedford H, Rowles G. Communicating with

parents about vaccination: A framework for health

professionals. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:154.

18. Danchin M, Nolan T. A positive approach to

parents with concerns about vaccination for

the family physician. Aust Fam Physician

2014;43(10):690–94.

19. Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Robinson JD,

Heritage J, et al. The influence of provider

communication behaviors on parental vaccine

acceptance and visit experience. Am J Pub Health

2015:e1–e7

20. Davies P, Chapman S, Leask J. Antivaccination

activists on the world wide web. Arch Dis Child

2002;87(1):22–25.

21. Jones AM, Omer SB, Bednarczyk RA, Halsey

NA, Moulton LH, Salmon DA. Parents’ source

of vaccine information and impact on vaccine

attitudes, beliefs and nonmedical exemptions. Adv

Prev Med 2012;2012:932741.

22. Busse JW, Wilson K, Campbell JB. Attitudes

towards vaccination among chiropractic and

naturopathic students. Vaccine 2008;26(49):

6237-43.

23. Schmidt K, Ernst E. MMR vaccination advice over

the internet. Vaccine 2003;21(11-12):1044−47.

24. Downey L, Tyree PT, Huebner CE, Lafferty WE.

Pediatric vaccination and vaccine-preventable

disease acquisition: Associations with care

by complementary and alternative medicine

providers. Matern Child Health J 2010;14(6):

922–30.

25. Wardle J, Stewart C, Parker M. Jabs and barbs:

Ways to address misleading vaccination and

immunisation information using currently available

strategies. J Law and Med 2013;21(1):159–78.

26. Lawrence GL, MacIntyre CR, Hull PB, McIntyre

PB. Effectiveness of the linkage of child care and

maternity payments to childhood immunisation.

Vaccine 2004;22(17–18):2345–50.

27. Miles M, Ryman TK, Dietz V, Zell E, Luman

ET. Validity of vaccination cards and parental

recall to estimate vaccination coverage: A

systematic review of the literature. Vaccine.

2013;31(12):1560–68.

28. Hull BP. Australian childhood immunisation

coverage. Commun Dis Intell 2014;38(2):E157.

1 out of 7

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.