Strategies for Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy: Communication & Skills

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/14

|5

|4488

|17

Report

AI Summary

This report, contributed to Desklib, focuses on the critical issue of vaccine hesitancy and the essential communication and counselling skills required for public health professionals to address it effectively. The Italian law 119/2017 mandates childhood vaccinations, yet vaccine hesitancy remains a significant challenge. The report outlines the definition of vaccine hesitancy, its complexity, and the need for strategic communication approaches. It emphasizes the importance of basic health counselling skills, including active listening, empathy, and self-awareness, to build trust and address concerns. The report categorizes the population into groups based on their vaccine deficit (hesitant, unconcerned, active resisters, poorly reached) and suggests tailored communication strategies for each. It highlights the importance of understanding individual risk perceptions and the role of participatory communication models. The report also stresses the need for strategic communication planning and integrated collaboration among various institutions and services to improve vaccination rates and public health outcomes. This report provides valuable insights and practical strategies for healthcare workers and public health professionals.

Brief notes

195

Key words

• vaccination

• communication

• counselling

Communication and basic health

counselling skills to tackle vaccine

hesitancy

Valentina Possenti1, Anna Maria Luzi2, Anna Colucci2 and Barbara De Mei1

1Centro Nazionale per la Prevenzione delle Malattie e la Promozione della Salute, Istituto Superiore

di Sanità, Rome, Italy

2Dipartimento Malattie Infettive, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy

Ann Ist Super Sanità 2019 | Vol. 55, No. 2: 195-199

DOI: 10.4415/ANN_19_02_12

INTRODUCTION

The law 119/2017, as conversionof the decree

73/2017, made ten childhood vaccinations (tetanus,

poliomyelitis, hepatitis B, diphtheria, pertussis, hae-

mophilus B, measles, mumps, rubella, chicken pox)

mandatory in Italy where coverage rates for various vac-

cine-preventable diseases have been decreasing since

2013 [1-3]. Vaccine hesitancy is defined as the reluc-

tance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of

vaccines [4], and enlisted among the ten major issues

that demand attention from the World Health Organi-

zation (WHO) and health partners in 2019 [5]. Namely,

it is a complex and context specific behaviour because it

varies across time, place and vaccines and is influenced

by a number of factors including issues of confidence,

complacency,and convenience.Vaccine-hesitantin-

dividuals constitute a heterogeneous group of people

who hold wide-ranged indecision on some vaccines as

well as on vaccination overall: they may accept vac-

cines but remain concerned, may refuse or delay some

vaccines but accept others, or may refuse all vaccines.

Basing on this complexity, to date immunization cover-

age are the proxy data mostly used even if it is known

that they are proven to be reliable for small samples

and vaccine decrease does not fully coincide with vac-

cine hesitancy [6]. This relevant issue in public health

broadly encompasses communication approaches that

public health professionals can adopt to address vac-

cine hesitancy effectively. An Italian study shows that,

even if paediatricians are favourable to vaccines and

vaccinations, gaps are retrieved between their overall

positive attitudes on one hand and knowledge, beliefs

and practices on the other hand, consequently affecting

their response capacity to address parents’ questions

[7]. In general, public health institutions should com-

municate using strategically established methods and

avoiding rushed communication which leads to imple-

menting wrong interventions and losing credibility. In

2010, the WHO suggested that to improve communi-

cation effectiveness within the healthcare system some

elements are needed, such as development of networks

and empowerment of communication competences [8-

14]. Moreover, within vaccine communication, public

health professionals deal with an even more highly com-

plex process that involves several different stakeholders

who are featured by own worldviews, perceptions and

needs. In this framework, vaccine communication does

not correspond to performing one-way informative in-

terventions or teaching, but initiates mutual dialogue

and reciprocal exchange among all people involved,

despite their different roles and diverse responsibilities.

It entails that communication methods and tools have

to be adequately aligned with the specific setting and

intended target groups. Both individuals and the com-

Address for correspondence: Valentina Possenti, Centro Nazionale per la Prevenzione delle Malattie e la Promozione della Salute, Istituto Superiore

di Sanità, Viale Regina Elena 299, 00161 Rome, Italy. E-mail: valentina.possenti@iss.it.

Abstract

The Italian law 119/2017 mandates ten childhood vaccinations to allow population aged

0-16 attend educational places and state school. This law enforcement is due to low

coverage rates for some vaccine-preventable diseases and to a complex phenomenon

known as vaccine hesitancy. Basic health counselling skills represent relevant resources

to let healthcare workers effectively address vaccine hesitancy in the population. We in-

dicated recommended communication approaches and basic health counselling skills to

be applied by public health professionals according to the specific target population with

vaccine deficit that means people not at all or partially reached by vaccinations. Public

health professionals are called to know, acquire, use, and adapt basic health counsel-

ling skills to effectively address vaccine hesitancy diversely affecting different groups of

population.

195

Key words

• vaccination

• communication

• counselling

Communication and basic health

counselling skills to tackle vaccine

hesitancy

Valentina Possenti1, Anna Maria Luzi2, Anna Colucci2 and Barbara De Mei1

1Centro Nazionale per la Prevenzione delle Malattie e la Promozione della Salute, Istituto Superiore

di Sanità, Rome, Italy

2Dipartimento Malattie Infettive, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy

Ann Ist Super Sanità 2019 | Vol. 55, No. 2: 195-199

DOI: 10.4415/ANN_19_02_12

INTRODUCTION

The law 119/2017, as conversionof the decree

73/2017, made ten childhood vaccinations (tetanus,

poliomyelitis, hepatitis B, diphtheria, pertussis, hae-

mophilus B, measles, mumps, rubella, chicken pox)

mandatory in Italy where coverage rates for various vac-

cine-preventable diseases have been decreasing since

2013 [1-3]. Vaccine hesitancy is defined as the reluc-

tance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of

vaccines [4], and enlisted among the ten major issues

that demand attention from the World Health Organi-

zation (WHO) and health partners in 2019 [5]. Namely,

it is a complex and context specific behaviour because it

varies across time, place and vaccines and is influenced

by a number of factors including issues of confidence,

complacency,and convenience.Vaccine-hesitantin-

dividuals constitute a heterogeneous group of people

who hold wide-ranged indecision on some vaccines as

well as on vaccination overall: they may accept vac-

cines but remain concerned, may refuse or delay some

vaccines but accept others, or may refuse all vaccines.

Basing on this complexity, to date immunization cover-

age are the proxy data mostly used even if it is known

that they are proven to be reliable for small samples

and vaccine decrease does not fully coincide with vac-

cine hesitancy [6]. This relevant issue in public health

broadly encompasses communication approaches that

public health professionals can adopt to address vac-

cine hesitancy effectively. An Italian study shows that,

even if paediatricians are favourable to vaccines and

vaccinations, gaps are retrieved between their overall

positive attitudes on one hand and knowledge, beliefs

and practices on the other hand, consequently affecting

their response capacity to address parents’ questions

[7]. In general, public health institutions should com-

municate using strategically established methods and

avoiding rushed communication which leads to imple-

menting wrong interventions and losing credibility. In

2010, the WHO suggested that to improve communi-

cation effectiveness within the healthcare system some

elements are needed, such as development of networks

and empowerment of communication competences [8-

14]. Moreover, within vaccine communication, public

health professionals deal with an even more highly com-

plex process that involves several different stakeholders

who are featured by own worldviews, perceptions and

needs. In this framework, vaccine communication does

not correspond to performing one-way informative in-

terventions or teaching, but initiates mutual dialogue

and reciprocal exchange among all people involved,

despite their different roles and diverse responsibilities.

It entails that communication methods and tools have

to be adequately aligned with the specific setting and

intended target groups. Both individuals and the com-

Address for correspondence: Valentina Possenti, Centro Nazionale per la Prevenzione delle Malattie e la Promozione della Salute, Istituto Superiore

di Sanità, Viale Regina Elena 299, 00161 Rome, Italy. E-mail: valentina.possenti@iss.it.

Abstract

The Italian law 119/2017 mandates ten childhood vaccinations to allow population aged

0-16 attend educational places and state school. This law enforcement is due to low

coverage rates for some vaccine-preventable diseases and to a complex phenomenon

known as vaccine hesitancy. Basic health counselling skills represent relevant resources

to let healthcare workers effectively address vaccine hesitancy in the population. We in-

dicated recommended communication approaches and basic health counselling skills to

be applied by public health professionals according to the specific target population with

vaccine deficit that means people not at all or partially reached by vaccinations. Public

health professionals are called to know, acquire, use, and adapt basic health counsel-

ling skills to effectively address vaccine hesitancy diversely affecting different groups of

population.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Valentina Possenti, Anna Maria Luzi, Anna Colucciand Barbara De Mei

Brief notes

196

munity as a whole shall be effectively involved so that

homogenous, consistent and strategically coordinated

interventions can be implemented [15].

In particular, to effectively address vaccine hesitancy

in the general population, basic health counselling skills

represent relevant resources to professionals because

they are key elements to make healthcare workers cre-

ate effective relationships with people who can activate

their own resources and choose solutions that are con-

sistent with their needs. Basic counselling skills actually

stand for in fact the components of a well-structured

intervention aimed at helping people to actively face

health-related challenges.

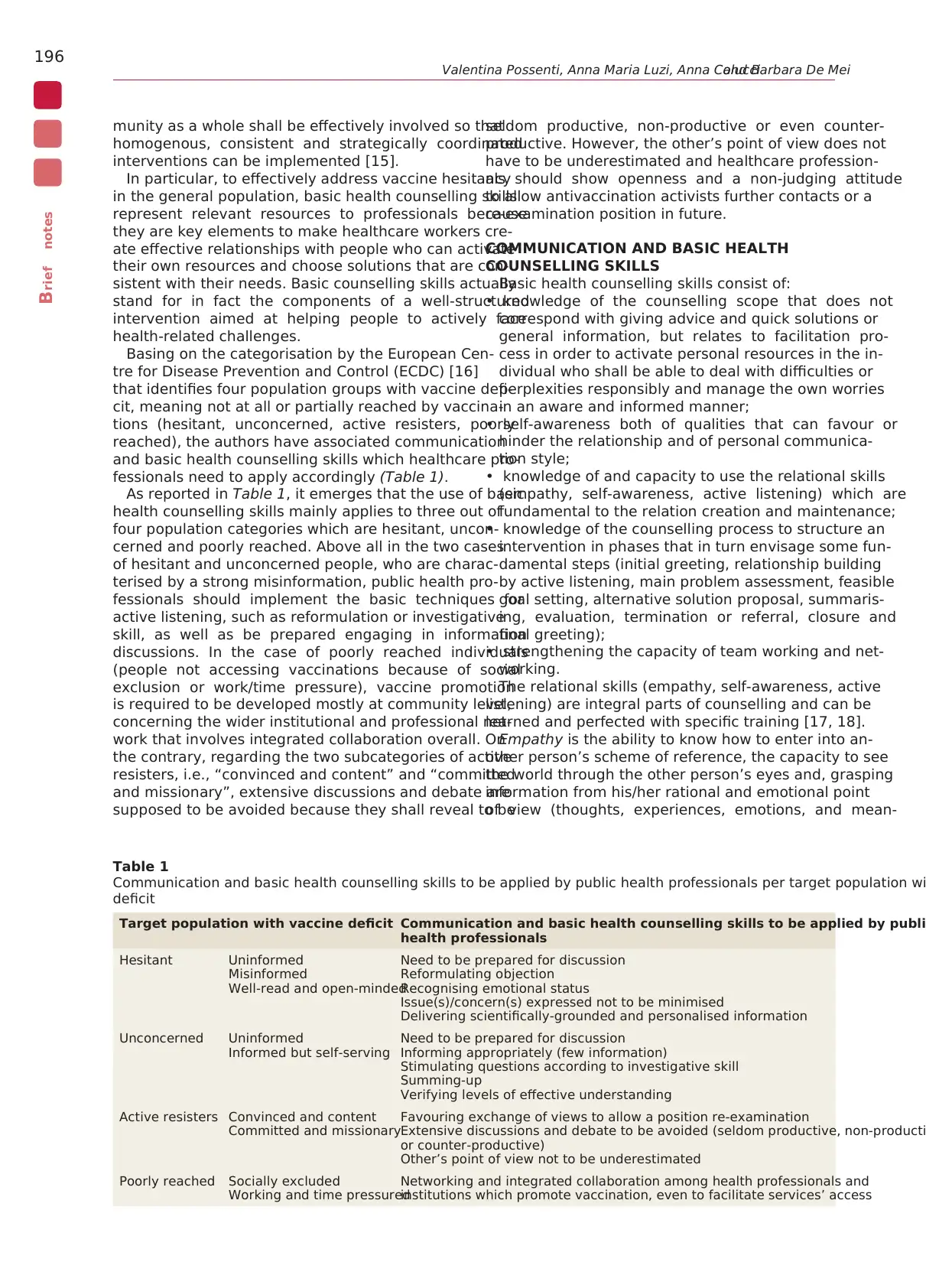

Basing on the categorisation by the European Cen-

tre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) [16]

that identifies four population groups with vaccine defi-

cit, meaning not at all or partially reached by vaccina-

tions (hesitant, unconcerned, active resisters, poorly

reached), the authors have associated communication

and basic health counselling skills which healthcare pro-

fessionals need to apply accordingly (Table 1).

As reported in Table 1, it emerges that the use of basic

health counselling skills mainly applies to three out of

four population categories which are hesitant, uncon-

cerned and poorly reached. Above all in the two cases

of hesitant and unconcerned people, who are charac-

terised by a strong misinformation, public health pro-

fessionals should implement the basic techniques for

active listening, such as reformulation or investigative

skill, as well as be prepared engaging in information

discussions. In the case of poorly reached individuals

(people not accessing vaccinations because of social

exclusion or work/time pressure), vaccine promotion

is required to be developed mostly at community level,

concerning the wider institutional and professional net-

work that involves integrated collaboration overall. On

the contrary, regarding the two subcategories of active

resisters, i.e., “convinced and content” and “committed

and missionary”, extensive discussions and debate are

supposed to be avoided because they shall reveal to be

seldom productive, non-productive or even counter-

productive. However, the other’s point of view does not

have to be underestimated and healthcare profession-

als should show openness and a non-judging attitude

to allow antivaccination activists further contacts or a

re-examination position in future.

COMMUNICATION AND BASIC HEALTH

COUNSELLING SKILLS

Basic health counselling skills consist of:

• knowledge of the counselling scope that does not

correspond with giving advice and quick solutions or

general information, but relates to facilitation pro-

cess in order to activate personal resources in the in-

dividual who shall be able to deal with difficulties or

perplexities responsibly and manage the own worries

in an aware and informed manner;

• self-awareness both of qualities that can favour or

hinder the relationship and of personal communica-

tion style;

• knowledge of and capacity to use the relational skills

(empathy, self-awareness, active listening) which are

fundamental to the relation creation and maintenance;

• knowledge of the counselling process to structure an

intervention in phases that in turn envisage some fun-

damental steps (initial greeting, relationship building

by active listening, main problem assessment, feasible

goal setting, alternative solution proposal, summaris-

ing, evaluation, termination or referral, closure and

final greeting);

• strengthening the capacity of team working and net-

working.

The relational skills (empathy, self-awareness, active

listening) are integral parts of counselling and can be

learned and perfected with specific training [17, 18].

Empathy is the ability to know how to enter into an-

other person’s scheme of reference, the capacity to see

the world through the other person’s eyes and, grasping

information from his/her rational and emotional point

of view (thoughts, experiences, emotions, and mean-

Table 1

Communication and basic health counselling skills to be applied by public health professionals per target population wi

deficit

Target population with vaccine deficit Communication and basic health counselling skills to be applied by publi

health professionals

Hesitant Uninformed

Misinformed

Well-read and open-minded

Need to be prepared for discussion

Reformulating objection

Recognising emotional status

Issue(s)/concern(s) expressed not to be minimised

Delivering scientifically-grounded and personalised information

Unconcerned Uninformed

Informed but self-serving

Need to be prepared for discussion

Informing appropriately (few information)

Stimulating questions according to investigative skill

Summing-up

Verifying levels of effective understanding

Active resisters Convinced and content

Committed and missionary

Favouring exchange of views to allow a position re-examination

Extensive discussions and debate to be avoided (seldom productive, non-producti

or counter-productive)

Other’s point of view not to be underestimated

Poorly reached Socially excluded

Working and time pressured

Networking and integrated collaboration among health professionals and

institutions which promote vaccination, even to facilitate services’ access

Brief notes

196

munity as a whole shall be effectively involved so that

homogenous, consistent and strategically coordinated

interventions can be implemented [15].

In particular, to effectively address vaccine hesitancy

in the general population, basic health counselling skills

represent relevant resources to professionals because

they are key elements to make healthcare workers cre-

ate effective relationships with people who can activate

their own resources and choose solutions that are con-

sistent with their needs. Basic counselling skills actually

stand for in fact the components of a well-structured

intervention aimed at helping people to actively face

health-related challenges.

Basing on the categorisation by the European Cen-

tre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) [16]

that identifies four population groups with vaccine defi-

cit, meaning not at all or partially reached by vaccina-

tions (hesitant, unconcerned, active resisters, poorly

reached), the authors have associated communication

and basic health counselling skills which healthcare pro-

fessionals need to apply accordingly (Table 1).

As reported in Table 1, it emerges that the use of basic

health counselling skills mainly applies to three out of

four population categories which are hesitant, uncon-

cerned and poorly reached. Above all in the two cases

of hesitant and unconcerned people, who are charac-

terised by a strong misinformation, public health pro-

fessionals should implement the basic techniques for

active listening, such as reformulation or investigative

skill, as well as be prepared engaging in information

discussions. In the case of poorly reached individuals

(people not accessing vaccinations because of social

exclusion or work/time pressure), vaccine promotion

is required to be developed mostly at community level,

concerning the wider institutional and professional net-

work that involves integrated collaboration overall. On

the contrary, regarding the two subcategories of active

resisters, i.e., “convinced and content” and “committed

and missionary”, extensive discussions and debate are

supposed to be avoided because they shall reveal to be

seldom productive, non-productive or even counter-

productive. However, the other’s point of view does not

have to be underestimated and healthcare profession-

als should show openness and a non-judging attitude

to allow antivaccination activists further contacts or a

re-examination position in future.

COMMUNICATION AND BASIC HEALTH

COUNSELLING SKILLS

Basic health counselling skills consist of:

• knowledge of the counselling scope that does not

correspond with giving advice and quick solutions or

general information, but relates to facilitation pro-

cess in order to activate personal resources in the in-

dividual who shall be able to deal with difficulties or

perplexities responsibly and manage the own worries

in an aware and informed manner;

• self-awareness both of qualities that can favour or

hinder the relationship and of personal communica-

tion style;

• knowledge of and capacity to use the relational skills

(empathy, self-awareness, active listening) which are

fundamental to the relation creation and maintenance;

• knowledge of the counselling process to structure an

intervention in phases that in turn envisage some fun-

damental steps (initial greeting, relationship building

by active listening, main problem assessment, feasible

goal setting, alternative solution proposal, summaris-

ing, evaluation, termination or referral, closure and

final greeting);

• strengthening the capacity of team working and net-

working.

The relational skills (empathy, self-awareness, active

listening) are integral parts of counselling and can be

learned and perfected with specific training [17, 18].

Empathy is the ability to know how to enter into an-

other person’s scheme of reference, the capacity to see

the world through the other person’s eyes and, grasping

information from his/her rational and emotional point

of view (thoughts, experiences, emotions, and mean-

Table 1

Communication and basic health counselling skills to be applied by public health professionals per target population wi

deficit

Target population with vaccine deficit Communication and basic health counselling skills to be applied by publi

health professionals

Hesitant Uninformed

Misinformed

Well-read and open-minded

Need to be prepared for discussion

Reformulating objection

Recognising emotional status

Issue(s)/concern(s) expressed not to be minimised

Delivering scientifically-grounded and personalised information

Unconcerned Uninformed

Informed but self-serving

Need to be prepared for discussion

Informing appropriately (few information)

Stimulating questions according to investigative skill

Summing-up

Verifying levels of effective understanding

Active resisters Convinced and content

Committed and missionary

Favouring exchange of views to allow a position re-examination

Extensive discussions and debate to be avoided (seldom productive, non-producti

or counter-productive)

Other’s point of view not to be underestimated

Poorly reached Socially excluded

Working and time pressured

Networking and integrated collaboration among health professionals and

institutions which promote vaccination, even to facilitate services’ access

Vaccine hesitancy and communication

Brief notes

197

ings), to understand the person’s requests and needs.

By showing empathy, healthcare workers live “as if” they

were the others but staying separate from the others,

otherwise they would no longer be able to help people

and meet people needs. Being empathic does not mean

confusing the two viewpoints: empathy is in fact sup-

ported by distinction and not confusion. In the profes-

sional relationship between experts and lay public, em-

pathy contributes to maintain separation between the

two different roles [19-23].

Self-awareness relates to being familiar with the own

“inner world” that is the cultural reference scheme,

value system, perceptions, emotions, and personal con-

ceptual maps. Other factors to be aware of are: the con-

text, the self-observation and self-monitoring capacity,

the management of nonverbal and paraverbal language

that is the emotional expression underlying the verbal

content [17].

Active listening helps both professionals and people

focusing on the other’s point of view, it can be triggered

through bidirectional communicative channels that fa-

cilitate useful information exchange flows and participa-

tory processes. It is fully based on empathy and on ac-

cepting the other’s point of view, as well as on creating a

positive relationship and a non-judging approach [19].

To listen actively, the adoption of a reference method-

ology articulated in empathic reflecting is necessary. It

encompasses the use of four specific communicative

techniques:reformulation,clarification,investigative

skill, first-person messages [24]. In particular:

• reformulation corresponds with repeating what the

other has just said, using the same words or rephras-

ing in a more concise way by other terms, without

adding any other concepts or different content (“Then

you are telling me that…”, “This means that you think…”,

“In other words…”);

• clarification uses the outlining emotions associated

with the content communicated, referring to verbal,

paraverbal and non-verbal communication (“From the

look on your face it seems to me that you are worried”;

“From the tone of your voice, I can feel you are uncertain

about what I am saying”);

• the investigative skill is the ability to ask, selecting

the most appropriate question type according to the

specific situation: “open questions” to be preferred at

the beginning of the conversation because they allow

wider answer options, extend and deepen the rela-

tionship, encourage opinion and thought expression;

closed-ended questions are clearly defined, they in-

duce a unique answer, and often stress only one reply

option, limit the communication and make it more

focussed, demand only objective facts and sometimes

may seem restrictive and obstructing (“When…?”,

”Where?”, “Who?”). Questions starting with “Why” can

be perceived as accusatory, and should be preferably

avoided;

• the use of first-person messages helps to distinguish

between professional’s and another person’s opinions

contributing to avoid conflicts. This technique serves

also to create a non-judgmental and an autonomous

decision-making process (“I think that…”, “In my opin-

ion…”) [17, 18].

THE USE OF COMMUNICATION AND

BASIC HEALTH COUNSELLING SKILLS TO

ADDRESS VACCINE HESITANCY

As indicated, public health professionals need to

know, acquire and implement basic vaccine counselling

skills when dealing above all with seven out of nine chal-

lenging population groups, even if such these compe-

tences can be also helpful somehow with people totally

refusing vaccinations. Knowledge and correct use of

basic health counselling skills allow in fact healthcare

workers achieve an effective vaccine communication

because relying on a structured and personalised inter-

vention. Vaccine communication need to acknowledge

individual risk perception that does not depend only on

the effective hazard but to a greater extent also on the

outrage linked to it, basically related to emotional fac-

tors prevailing on the hazard itself [25-27]. Within vac-

cine communication, by “actively listening” to people

fears and being aware of the wide-ranged determinants

for the perceived risk, public health authorities have

better opportunities to understand and to deal with the

origin of perception [28-30]. Especially as far as par-

ticular groups are concerned, in the case of childhood

vaccinations the main parents’ fears and worries refer to

adverse reaction effects or vaccine safety [31, 2]. If peo-

ple perceive empathy and consideration to their doubts

and opinions, they will be in turn more willing to listen

and trust. On the contrary, when people perceive sense

of distance, the trust level would be reduced and emo-

tional components of perception prevail on the rational

part, not activating listening triggers even if adequate

scientific communication was developed. Vaccine com-

munication bases on the participatory communication

model featured by an interactive exchange assessment

overall, where the understanding of social and personal

issues is decisive to make scientific information a useful

knowledge to citizens [32, 33].

People should not perceive to be passively advised

as “just getting reassurance by experts”: in the current

communication approach the public sphere is put at the

centre of the whole process [25, 27].

If vaccine communication can be considered an in-

teractive process of information and opinion sharing

among individuals, groups and institutions, healthcare

workers provide people with constructive, up-to-date

and meaningful messages and direct-access informa-

tion services, using a varied range of tools in order to

allow them make the best possible decisions about their

own health. This make that an important step within

the counselling intervention relates to verifying levels

of effective understanding in people after having pro-

vided scientifically-grounded and personalised informa-

tion. Looking at the big picture as a whole, in fact, in a

multistakeholder scenario the position of public health

professionals toward individuals or communities is fun-

damental as per their key advocacy role in being at the

helm of the processes, from planning to development,

monitoring and evaluation. Such a framework neces-

sarily demands for strategic communication planning,

favoured by the integrated participation and collabora-

tion of institutions, services and systems involved at dif-

ferent levels (national, regional and local) [34-38].

Brief notes

197

ings), to understand the person’s requests and needs.

By showing empathy, healthcare workers live “as if” they

were the others but staying separate from the others,

otherwise they would no longer be able to help people

and meet people needs. Being empathic does not mean

confusing the two viewpoints: empathy is in fact sup-

ported by distinction and not confusion. In the profes-

sional relationship between experts and lay public, em-

pathy contributes to maintain separation between the

two different roles [19-23].

Self-awareness relates to being familiar with the own

“inner world” that is the cultural reference scheme,

value system, perceptions, emotions, and personal con-

ceptual maps. Other factors to be aware of are: the con-

text, the self-observation and self-monitoring capacity,

the management of nonverbal and paraverbal language

that is the emotional expression underlying the verbal

content [17].

Active listening helps both professionals and people

focusing on the other’s point of view, it can be triggered

through bidirectional communicative channels that fa-

cilitate useful information exchange flows and participa-

tory processes. It is fully based on empathy and on ac-

cepting the other’s point of view, as well as on creating a

positive relationship and a non-judging approach [19].

To listen actively, the adoption of a reference method-

ology articulated in empathic reflecting is necessary. It

encompasses the use of four specific communicative

techniques:reformulation,clarification,investigative

skill, first-person messages [24]. In particular:

• reformulation corresponds with repeating what the

other has just said, using the same words or rephras-

ing in a more concise way by other terms, without

adding any other concepts or different content (“Then

you are telling me that…”, “This means that you think…”,

“In other words…”);

• clarification uses the outlining emotions associated

with the content communicated, referring to verbal,

paraverbal and non-verbal communication (“From the

look on your face it seems to me that you are worried”;

“From the tone of your voice, I can feel you are uncertain

about what I am saying”);

• the investigative skill is the ability to ask, selecting

the most appropriate question type according to the

specific situation: “open questions” to be preferred at

the beginning of the conversation because they allow

wider answer options, extend and deepen the rela-

tionship, encourage opinion and thought expression;

closed-ended questions are clearly defined, they in-

duce a unique answer, and often stress only one reply

option, limit the communication and make it more

focussed, demand only objective facts and sometimes

may seem restrictive and obstructing (“When…?”,

”Where?”, “Who?”). Questions starting with “Why” can

be perceived as accusatory, and should be preferably

avoided;

• the use of first-person messages helps to distinguish

between professional’s and another person’s opinions

contributing to avoid conflicts. This technique serves

also to create a non-judgmental and an autonomous

decision-making process (“I think that…”, “In my opin-

ion…”) [17, 18].

THE USE OF COMMUNICATION AND

BASIC HEALTH COUNSELLING SKILLS TO

ADDRESS VACCINE HESITANCY

As indicated, public health professionals need to

know, acquire and implement basic vaccine counselling

skills when dealing above all with seven out of nine chal-

lenging population groups, even if such these compe-

tences can be also helpful somehow with people totally

refusing vaccinations. Knowledge and correct use of

basic health counselling skills allow in fact healthcare

workers achieve an effective vaccine communication

because relying on a structured and personalised inter-

vention. Vaccine communication need to acknowledge

individual risk perception that does not depend only on

the effective hazard but to a greater extent also on the

outrage linked to it, basically related to emotional fac-

tors prevailing on the hazard itself [25-27]. Within vac-

cine communication, by “actively listening” to people

fears and being aware of the wide-ranged determinants

for the perceived risk, public health authorities have

better opportunities to understand and to deal with the

origin of perception [28-30]. Especially as far as par-

ticular groups are concerned, in the case of childhood

vaccinations the main parents’ fears and worries refer to

adverse reaction effects or vaccine safety [31, 2]. If peo-

ple perceive empathy and consideration to their doubts

and opinions, they will be in turn more willing to listen

and trust. On the contrary, when people perceive sense

of distance, the trust level would be reduced and emo-

tional components of perception prevail on the rational

part, not activating listening triggers even if adequate

scientific communication was developed. Vaccine com-

munication bases on the participatory communication

model featured by an interactive exchange assessment

overall, where the understanding of social and personal

issues is decisive to make scientific information a useful

knowledge to citizens [32, 33].

People should not perceive to be passively advised

as “just getting reassurance by experts”: in the current

communication approach the public sphere is put at the

centre of the whole process [25, 27].

If vaccine communication can be considered an in-

teractive process of information and opinion sharing

among individuals, groups and institutions, healthcare

workers provide people with constructive, up-to-date

and meaningful messages and direct-access informa-

tion services, using a varied range of tools in order to

allow them make the best possible decisions about their

own health. This make that an important step within

the counselling intervention relates to verifying levels

of effective understanding in people after having pro-

vided scientifically-grounded and personalised informa-

tion. Looking at the big picture as a whole, in fact, in a

multistakeholder scenario the position of public health

professionals toward individuals or communities is fun-

damental as per their key advocacy role in being at the

helm of the processes, from planning to development,

monitoring and evaluation. Such a framework neces-

sarily demands for strategic communication planning,

favoured by the integrated participation and collabora-

tion of institutions, services and systems involved at dif-

ferent levels (national, regional and local) [34-38].

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Valentina Possenti, Anna Maria Luzi, Anna Colucciand Barbara De Mei

Brief notes

198

The professional practice of healthcare workers is

framed in a specific organisational system and, more

broadly, in a complex context where they refer to other

stakeholders, institutions and media. Thus, health pro-

fessionals need to be aware of web-based and new media

for two reasons: on the one hand, knowing the kind of

information that flows through the net could be useful

to forestall some possible criticism; on the other hand,

groups on social networks may constitute extremely

valuable tools to keep individuals up to date with advices

and to promptly hinder false or ambiguous knowledge

they could have found on the web. Health information-

seeking behaviour on the web shows, in fact, how often

people turn first to the Internet both using information

to formulate their thoughts and making their own judge-

ments on preferred treatments [39]. Web 2.0, forums

and social networks, which enable two‐way and multi‐

way communication flows, have spread out anti-vacci-

nation voices to broader reach than ever before while,

years ago, they would have been restricted to certain

countries [40]. Health professionals are getting used to

situations where the “health blogger” or the “concerned

mother” are as important as – or even more influent

than – a general practitioner or paediatrician, strongly

influencing individual decision-making process [41-45].

Aware and skilled communication processes can facili-

tate relationships because even in presence of a world

wide web 2.0, they do represent significant tools for col-

laboration building and achieving shared solutions. The

public health goal is actually to stimulate professionals

to reflect upon the need to recognize, develop and adapt

basic health counselling skills in order to provide ade-

quate information and emotional support to people who

show hesitant attitudes towards vaccinations and can be

allowed to activate informed and responsible decisions.

Conflict of interest statement

There are no potential conflicts of interest or any fi-

nancial or personal relationships with other people or

organizations that could inappropriately bias conduct

and findings of this study.

Received on 16 October 2019.

Accepted on 16 May 2019.

REFERENCES

1. Italia. Legge 31 luglio 2017, n. 119. Conversione in leg-

ge, con modificazioni, del decreto-legge 7 giugno 2017,

n. 73, recante disposizioni urgenti in materia di preven-

zione vaccinale. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica

Italiana – Serie Generale n. 182, 05 agosto 2017. Avail-

able from: www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2017/08/5/

17G00132/sg.

2. Giambi C, Fabiani M, D’Ancona F, et al. Parental vac-

cine hesitancy in Italy – Results from a national sur-

vey. Vaccine. 2018;36(6):779-87.doi:10.1016/j.vac-

cine.2017.12.074

3. Istituto Superiore di Sanità. EpiCentro. Il portale

dell’epidemiologia per la sanità pubblica. Morbillo, ul-

timi aggiornamenti. Available from: www.epicentro.iss.it/

problemi/morbillo/aggiornamenti.asp.

4. World Health Organization. Report of the SAGE work-

ing group on vaccine hesitancy. Geneva: WHO; 2014.

Available from: www.who.int/immunization/sage/meet-

ings/2014/october/SAGE_working_group_revised_re-

port_vaccine_hesitancy.pdf?ua=1.

5. World Health Organization. Ten threats to global health

in 2019. Geneva: WHO; 2019. Available from: www.who.

int/emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

6. Petrelli F, Contratti CM, Tanzi E, Grappasonni I. Vaccine

hesitancy, a public health problem. Ann Ig. 2018;30:86-

103. doi:10.7416/ai.2018.2200

7. Filia A, Bella A, D’Ancona F, Fabiani M, Giambi C,

Rizzo C, Ferrara L, Pascucci MG, Rota MC. Child-

hood vaccinations: knowledge, attitudes and practices

of paediatricians and factors associated with their con-

fidence in addressingparental concerns, Italy, 2016.

Euro Surveill. 2019;24(6):pii=1800275. doi: https://doi.

org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.6.1800275

8. Sweet M. Pandemic lessons learned from Australia. BMJ.

2009;339:424‐6.

9. Deirdre HD. The 2009 influenza pandemic. An indepen-

dent review of the UK response to the 2009 influenza

pandemic. 2010. Available from:

10. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.

cabinetoffice.gov.uk/media/416533/the2009influenza-

pandemic‐review.pdf.

11. Tay J, Ng YF, Cutter JL, James L. Influenza A

(H1N1/2009) pandemic in Singapore public health con-

trol measures implemented and lessons learnt. AAMS.

2010;39(4):313-24.

12. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Eu-

rope, University of Nottingham. Recommendations for

good practice in pandemic preparedness. Copenhagen,

Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2010.

Available from: www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_

file/0017/128060/e94534.pdf.

13. World Health Organization. Report of the review com-

mittee on the functioning of the international health reg-

ulations (2005) in relation to Pandemic (H1N1) 2009.

Geneva: WHO; 2011. Available from: http://apps.who.

int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA64/A64_10‐en.pdf.

14. Greco D, Stern EK, Marks G. Review of ECDC’s re-

sponse to the influenza pandemic 2009-2010. Stockholm:

ECDC; 2011. Available from: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/

aboutus/Key%20Documents/241111COR_Pandemic_

response.pdf.

15. World Health Organization. Public health measures dur-

ing the influenza A(H1N1) 2009 pandemic. Meeting

report. WHO Technical Consultation 26-28 October

2010, Gammarth, Tunisia. WHO; 2010. Available from:

http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2011/WHO_HSE_GIP_

ITP_2011.3_eng.pdf.

16. ASSET. Action plan on science in society related issues in

epidemics and total pandemics. Action plan handbook.

Available from: www.asset-scienceinsociety.eu/outputs/

deliverables/action-plan-handbook.

17. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Let’s talk about protection. Stockholm: ECDC; 2016.

doi: 10.2900/573817

18. Luzi AM, De Mei B, Colucci A, Gallo P. Criteria for

standardizing counselling for HIV testing. Ann Ist Super

Sanità. 2010;46(1):42-50. doi: 10.4415/ANN_10_01_06

19. TELLME. Transparentcommunicationin epidemics:

Brief notes

198

The professional practice of healthcare workers is

framed in a specific organisational system and, more

broadly, in a complex context where they refer to other

stakeholders, institutions and media. Thus, health pro-

fessionals need to be aware of web-based and new media

for two reasons: on the one hand, knowing the kind of

information that flows through the net could be useful

to forestall some possible criticism; on the other hand,

groups on social networks may constitute extremely

valuable tools to keep individuals up to date with advices

and to promptly hinder false or ambiguous knowledge

they could have found on the web. Health information-

seeking behaviour on the web shows, in fact, how often

people turn first to the Internet both using information

to formulate their thoughts and making their own judge-

ments on preferred treatments [39]. Web 2.0, forums

and social networks, which enable two‐way and multi‐

way communication flows, have spread out anti-vacci-

nation voices to broader reach than ever before while,

years ago, they would have been restricted to certain

countries [40]. Health professionals are getting used to

situations where the “health blogger” or the “concerned

mother” are as important as – or even more influent

than – a general practitioner or paediatrician, strongly

influencing individual decision-making process [41-45].

Aware and skilled communication processes can facili-

tate relationships because even in presence of a world

wide web 2.0, they do represent significant tools for col-

laboration building and achieving shared solutions. The

public health goal is actually to stimulate professionals

to reflect upon the need to recognize, develop and adapt

basic health counselling skills in order to provide ade-

quate information and emotional support to people who

show hesitant attitudes towards vaccinations and can be

allowed to activate informed and responsible decisions.

Conflict of interest statement

There are no potential conflicts of interest or any fi-

nancial or personal relationships with other people or

organizations that could inappropriately bias conduct

and findings of this study.

Received on 16 October 2019.

Accepted on 16 May 2019.

REFERENCES

1. Italia. Legge 31 luglio 2017, n. 119. Conversione in leg-

ge, con modificazioni, del decreto-legge 7 giugno 2017,

n. 73, recante disposizioni urgenti in materia di preven-

zione vaccinale. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica

Italiana – Serie Generale n. 182, 05 agosto 2017. Avail-

able from: www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2017/08/5/

17G00132/sg.

2. Giambi C, Fabiani M, D’Ancona F, et al. Parental vac-

cine hesitancy in Italy – Results from a national sur-

vey. Vaccine. 2018;36(6):779-87.doi:10.1016/j.vac-

cine.2017.12.074

3. Istituto Superiore di Sanità. EpiCentro. Il portale

dell’epidemiologia per la sanità pubblica. Morbillo, ul-

timi aggiornamenti. Available from: www.epicentro.iss.it/

problemi/morbillo/aggiornamenti.asp.

4. World Health Organization. Report of the SAGE work-

ing group on vaccine hesitancy. Geneva: WHO; 2014.

Available from: www.who.int/immunization/sage/meet-

ings/2014/october/SAGE_working_group_revised_re-

port_vaccine_hesitancy.pdf?ua=1.

5. World Health Organization. Ten threats to global health

in 2019. Geneva: WHO; 2019. Available from: www.who.

int/emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

6. Petrelli F, Contratti CM, Tanzi E, Grappasonni I. Vaccine

hesitancy, a public health problem. Ann Ig. 2018;30:86-

103. doi:10.7416/ai.2018.2200

7. Filia A, Bella A, D’Ancona F, Fabiani M, Giambi C,

Rizzo C, Ferrara L, Pascucci MG, Rota MC. Child-

hood vaccinations: knowledge, attitudes and practices

of paediatricians and factors associated with their con-

fidence in addressingparental concerns, Italy, 2016.

Euro Surveill. 2019;24(6):pii=1800275. doi: https://doi.

org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.6.1800275

8. Sweet M. Pandemic lessons learned from Australia. BMJ.

2009;339:424‐6.

9. Deirdre HD. The 2009 influenza pandemic. An indepen-

dent review of the UK response to the 2009 influenza

pandemic. 2010. Available from:

10. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.

cabinetoffice.gov.uk/media/416533/the2009influenza-

pandemic‐review.pdf.

11. Tay J, Ng YF, Cutter JL, James L. Influenza A

(H1N1/2009) pandemic in Singapore public health con-

trol measures implemented and lessons learnt. AAMS.

2010;39(4):313-24.

12. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Eu-

rope, University of Nottingham. Recommendations for

good practice in pandemic preparedness. Copenhagen,

Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2010.

Available from: www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_

file/0017/128060/e94534.pdf.

13. World Health Organization. Report of the review com-

mittee on the functioning of the international health reg-

ulations (2005) in relation to Pandemic (H1N1) 2009.

Geneva: WHO; 2011. Available from: http://apps.who.

int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA64/A64_10‐en.pdf.

14. Greco D, Stern EK, Marks G. Review of ECDC’s re-

sponse to the influenza pandemic 2009-2010. Stockholm:

ECDC; 2011. Available from: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/

aboutus/Key%20Documents/241111COR_Pandemic_

response.pdf.

15. World Health Organization. Public health measures dur-

ing the influenza A(H1N1) 2009 pandemic. Meeting

report. WHO Technical Consultation 26-28 October

2010, Gammarth, Tunisia. WHO; 2010. Available from:

http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2011/WHO_HSE_GIP_

ITP_2011.3_eng.pdf.

16. ASSET. Action plan on science in society related issues in

epidemics and total pandemics. Action plan handbook.

Available from: www.asset-scienceinsociety.eu/outputs/

deliverables/action-plan-handbook.

17. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Let’s talk about protection. Stockholm: ECDC; 2016.

doi: 10.2900/573817

18. Luzi AM, De Mei B, Colucci A, Gallo P. Criteria for

standardizing counselling for HIV testing. Ann Ist Super

Sanità. 2010;46(1):42-50. doi: 10.4415/ANN_10_01_06

19. TELLME. Transparentcommunicationin epidemics:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Vaccine hesitancy and communication

Brief notes

199

learning lessons from experience,deliveringeffective

messages, providing evidence. Practical guide for health

risk communication. New communication strategies for

institutional actors. Available from: www.tellmeproject.

eu/node/390.

20. Rogers CR. La terapia centrata sul cliente. Firenze: Mar-

tinelli; 1989.

21. Watzlavick P, Beavin JH, Jackson DD. Pragmatica della

comunicazione umana. Boringhieri; 1976.

22. Gadotti G (Ed). La comunicazione sociale. Soggetti,

strumenti e linguaggi. Milano: Arcipelago; 2001.

23. Gadotti G, Bernocchi R. La pubblicità sociale. Maneg-

giare con cura. Roma: Carocci; 2010.

24. Polesana MA. La pubblicità intelligente. L’uso dell’ironia

in pubblicità. Milano: Franco Angeli; 2005.

25. De Mei B, Luzi AM. Le competenze di counselling per

una gestione consapevole delle reazioni personali e dei

comportamenti dell’operatore nella relazione professio-

nale. Dossier. Milano: Zadig; 2011.

26. TELLME. Transparentcommunicationin epidemics:

Learning Lessons from experience, delivering effective

messages, providing evidence. A new model for risk com-

munication in health. Available from: www.tellmeproject.

eu/node/314.

27. Sandman PM. Risk = Hazard + Outrage: Coping with

controversy about utility risks. Engineering News-Re-

cord; 1999. p. A19-A23.

28. Covello VT. Social and behavioral research on risk: uses

in risk management decisionmaking. In: Covello VT,

Mumpower JL, Stallen PJ, Uppuluri VRR (Eds). Envi-

ronmental impact assessment, technology assessment,

and risk analysis. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, Tokyo:

Springer-Verlag; 1985.

29. European Commission. Assessment report on EU‐wide

pandemic vaccine strategies. 2010. Available from: http://

ec.europa.eu/health/communicable_diseases/docs/assess-

ment_vaccine_en.pdf.

30. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Provider re-

sources for vaccine conversations with parents. Available

from: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/conversations/about-

vacc-conversations.html.

31. Sjoberg L. Risk Perception by the public and by experts:

a dilemma in risk management. Human Ecology Review.

1999;6(2):1-9.

32. Lambert TW, Soskolne LC, Bergum V, Howell J, Dosse-

tor JB. Ethical perspectives for public and environmental

health: fostering autonomy and the right to know. Envi-

ronmental Health Perspectives. 2003;111(2):133-7.

33. Leiss W, Krewski D. Risk communication: theory and

practice. In: Leiss W (Ed). Prospects and problems in risk

communication. Waterloo, Ontario: University of Water-

loo Press; 1989. p. 89-112.

34. Slovic P. The perception of risk. London and Sterling:

Earthscan Publ. Ltd; 2000.

35. Biasio LR. Vaccine hesitancy and health literacy.

Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(3):701-2.doi:

10.1080/21645515.2016.1243633

36. Beck U. La società del rischio. Roma: Carrocci Editore;

2000.

37. Biocca M. La comunicazione sul rischio per la salute. Nel

Teatro di Sagredo: verso una seconda modernità. Torino:

Centro Scientifico Editore; 2002. (Comunicazione in

Sanità Vol. 6).

38. Leiss W. Three phases in the evolution of risk commu-

nication practice. Annals of the American Academy of

Political and Social Science. 1996;545:85-94.

39. National Research Council. Improving risk communica-

tion. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1989.

40. Kata A. Anti-vaccine activists, Web 2.0 and the post-

modern paradigm. An overview of tactics and tropes

used online by the anti-vaccination movement. Vaccine.

2012;30:3778-89.

41. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Communication on immunisation – building trust”. Tech-

nical document. Stockholm: ECDC; 2012.

42. CDC Facebook page. Available from: https://www.face-

book.com/CDC/.

43. Markoff J. Entrepreneurs see a Web guided by common

sense. New York Times; 2006.

44. De Mei B, Luzi AM. Il valore aggiunto delle competenze

di counselling per una comunicazione efficace in ambito

professionale. Dossier. Milano: Zadig; 2011.

45. Catalan-Matamoros D, Peñafiel-Saiz C. How is com-

munication of vaccines in traditional media: a systematic

review. Perspectives in Public Health. 2018;138(4). doi:

10.1177/1757913918780142

Brief notes

199

learning lessons from experience,deliveringeffective

messages, providing evidence. Practical guide for health

risk communication. New communication strategies for

institutional actors. Available from: www.tellmeproject.

eu/node/390.

20. Rogers CR. La terapia centrata sul cliente. Firenze: Mar-

tinelli; 1989.

21. Watzlavick P, Beavin JH, Jackson DD. Pragmatica della

comunicazione umana. Boringhieri; 1976.

22. Gadotti G (Ed). La comunicazione sociale. Soggetti,

strumenti e linguaggi. Milano: Arcipelago; 2001.

23. Gadotti G, Bernocchi R. La pubblicità sociale. Maneg-

giare con cura. Roma: Carocci; 2010.

24. Polesana MA. La pubblicità intelligente. L’uso dell’ironia

in pubblicità. Milano: Franco Angeli; 2005.

25. De Mei B, Luzi AM. Le competenze di counselling per

una gestione consapevole delle reazioni personali e dei

comportamenti dell’operatore nella relazione professio-

nale. Dossier. Milano: Zadig; 2011.

26. TELLME. Transparentcommunicationin epidemics:

Learning Lessons from experience, delivering effective

messages, providing evidence. A new model for risk com-

munication in health. Available from: www.tellmeproject.

eu/node/314.

27. Sandman PM. Risk = Hazard + Outrage: Coping with

controversy about utility risks. Engineering News-Re-

cord; 1999. p. A19-A23.

28. Covello VT. Social and behavioral research on risk: uses

in risk management decisionmaking. In: Covello VT,

Mumpower JL, Stallen PJ, Uppuluri VRR (Eds). Envi-

ronmental impact assessment, technology assessment,

and risk analysis. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, Tokyo:

Springer-Verlag; 1985.

29. European Commission. Assessment report on EU‐wide

pandemic vaccine strategies. 2010. Available from: http://

ec.europa.eu/health/communicable_diseases/docs/assess-

ment_vaccine_en.pdf.

30. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Provider re-

sources for vaccine conversations with parents. Available

from: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/conversations/about-

vacc-conversations.html.

31. Sjoberg L. Risk Perception by the public and by experts:

a dilemma in risk management. Human Ecology Review.

1999;6(2):1-9.

32. Lambert TW, Soskolne LC, Bergum V, Howell J, Dosse-

tor JB. Ethical perspectives for public and environmental

health: fostering autonomy and the right to know. Envi-

ronmental Health Perspectives. 2003;111(2):133-7.

33. Leiss W, Krewski D. Risk communication: theory and

practice. In: Leiss W (Ed). Prospects and problems in risk

communication. Waterloo, Ontario: University of Water-

loo Press; 1989. p. 89-112.

34. Slovic P. The perception of risk. London and Sterling:

Earthscan Publ. Ltd; 2000.

35. Biasio LR. Vaccine hesitancy and health literacy.

Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(3):701-2.doi:

10.1080/21645515.2016.1243633

36. Beck U. La società del rischio. Roma: Carrocci Editore;

2000.

37. Biocca M. La comunicazione sul rischio per la salute. Nel

Teatro di Sagredo: verso una seconda modernità. Torino:

Centro Scientifico Editore; 2002. (Comunicazione in

Sanità Vol. 6).

38. Leiss W. Three phases in the evolution of risk commu-

nication practice. Annals of the American Academy of

Political and Social Science. 1996;545:85-94.

39. National Research Council. Improving risk communica-

tion. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1989.

40. Kata A. Anti-vaccine activists, Web 2.0 and the post-

modern paradigm. An overview of tactics and tropes

used online by the anti-vaccination movement. Vaccine.

2012;30:3778-89.

41. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Communication on immunisation – building trust”. Tech-

nical document. Stockholm: ECDC; 2012.

42. CDC Facebook page. Available from: https://www.face-

book.com/CDC/.

43. Markoff J. Entrepreneurs see a Web guided by common

sense. New York Times; 2006.

44. De Mei B, Luzi AM. Il valore aggiunto delle competenze

di counselling per una comunicazione efficace in ambito

professionale. Dossier. Milano: Zadig; 2011.

45. Catalan-Matamoros D, Peñafiel-Saiz C. How is com-

munication of vaccines in traditional media: a systematic

review. Perspectives in Public Health. 2018;138(4). doi:

10.1177/1757913918780142

1 out of 5

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.